James Keir Hardie on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

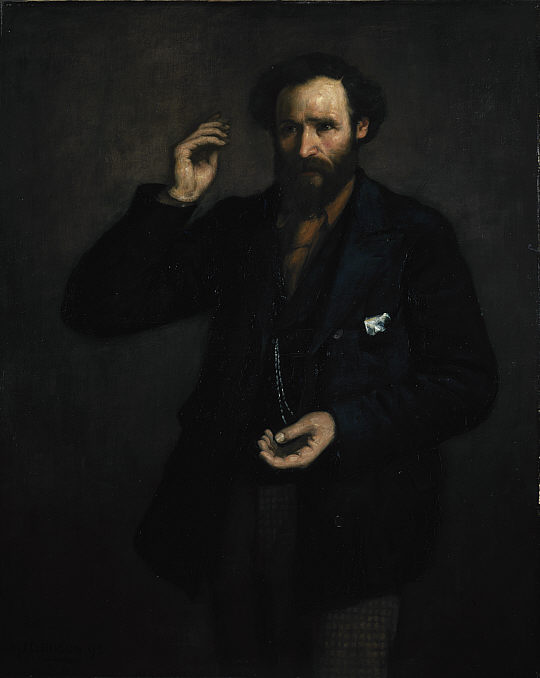

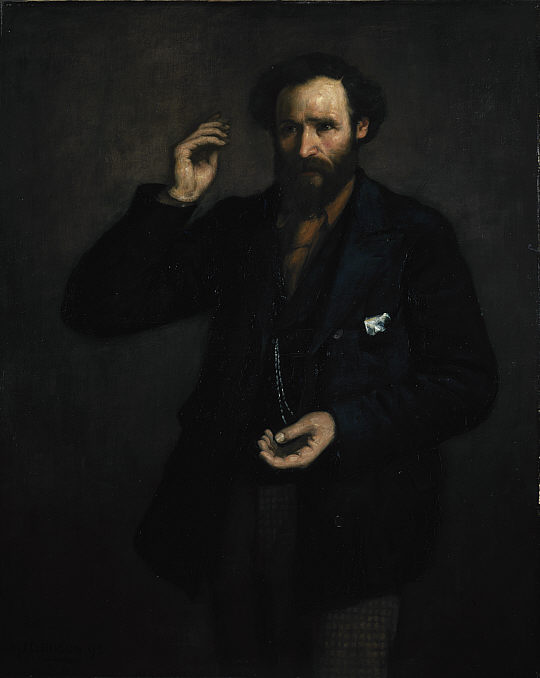

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish

James Keir Hardie was born on 15 August 1856 in a two-roomed cottage on the western edge of Newhouse,

James Keir Hardie was born on 15 August 1856 in a two-roomed cottage on the western edge of Newhouse,

The 23-year-old Hardie moved from the coal mines to union organisation work.

In May 1879, Scottish mine owners combined to force a reduction of wages, which had the effect of spurring the demand for unionisation. Huge meetings were held weekly at Hamilton as mine workers joined to vent their grievances. On 3 July 1879, Hardie was appointed Corresponding Secretary of the miners, a post which gave him opportunity to get in touch with other representatives of the mine workers throughout southern Scotland. Three weeks later, Hardie was chosen by the miners as their delegate to a National Conference of Miners to be held in Glasgow. He was appointed Miners' Agent in August 1879 and his new career as a trade union organiser and functionary was launched.

On 16 October 1879, Hardie attended a National Conference of miners at Dunfermline, at which he was selected as National Secretary, a high-sounding title which actually preceded the establishment of a coherent national organisation by several years. Hardie was active in the strike wave which swept the region in 1880, including a generalised strike of the mines of

The 23-year-old Hardie moved from the coal mines to union organisation work.

In May 1879, Scottish mine owners combined to force a reduction of wages, which had the effect of spurring the demand for unionisation. Huge meetings were held weekly at Hamilton as mine workers joined to vent their grievances. On 3 July 1879, Hardie was appointed Corresponding Secretary of the miners, a post which gave him opportunity to get in touch with other representatives of the mine workers throughout southern Scotland. Three weeks later, Hardie was chosen by the miners as their delegate to a National Conference of Miners to be held in Glasgow. He was appointed Miners' Agent in August 1879 and his new career as a trade union organiser and functionary was launched.

On 16 October 1879, Hardie attended a National Conference of miners at Dunfermline, at which he was selected as National Secretary, a high-sounding title which actually preceded the establishment of a coherent national organisation by several years. Hardie was active in the strike wave which swept the region in 1880, including a generalised strike of the mines of  In August 1881, Ayrshire miners put forward the demand for a 10 percent increase in wages, a proposition summarily refused by the region's mine owners. Despite the lack of funds for strike pay, a stoppage was called and a 10-week shutdown of the region's mines ensued. This strike also was formally a failure, with miners returning to work before their demands had been met, but not long after the return wages were escalated across the board by the mine owners, fearful of future labour actions. One of the other leaders of the strike was 19-year-old miner

In August 1881, Ayrshire miners put forward the demand for a 10 percent increase in wages, a proposition summarily refused by the region's mine owners. Despite the lack of funds for strike pay, a stoppage was called and a 10-week shutdown of the region's mines ensued. This strike also was formally a failure, with miners returning to work before their demands had been met, but not long after the return wages were escalated across the board by the mine owners, fearful of future labour actions. One of the other leaders of the strike was 19-year-old miner

Hardie was a dedicated

Hardie was a dedicated

Hardie spent the next five years of his life building up the Labour movement and speaking at various public meetings; he was arrested at a

Hardie spent the next five years of his life building up the Labour movement and speaking at various public meetings; he was arrested at a

After resigning the leadership of the party in 1908, Hardie devoted himself to campaigning for votes for women and developing a closer relationship with

After resigning the leadership of the party in 1908, Hardie devoted himself to campaigning for votes for women and developing a closer relationship with

On 2 December 2006, a memorial bust of Hardie was unveiled by

On 2 December 2006, a memorial bust of Hardie was unveiled by

J. Keir Hardie Biography

Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

at

Rhondda Cynon Taff Online: Unveiling the Keir Hardie Bust

Retrieved 7 October 2009. * *

Scottish Labour Party, History

Kier Hardie – Labour's First MP

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Hardie, Keir 1856 births 1915 deaths British anti–World War I activists British pacifists British republicans British socialists British suffragists Chairs of the Labour Party (UK) Coal miner activists Congregationalist socialists European democratic socialists Independent Labour Party MPs Independent Labour Party National Administrative Committee members Leaders of the Labour Party (UK) Liberal Party (UK) politicians Labour Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Welsh Labour Party MPs People from Lanarkshire Politics of Merthyr Tydfil Scottish Christian socialists Scottish journalists Scottish Labour Party (1888) politicians Scottish pacifists Scottish socialists UK MPs 1892–1895 UK MPs 1900–1906 UK MPs 1906–1910 UK MPs 1910–1918 UK MPs 1910 British political party founders Deaths from pneumonia in Scotland

trade unionist

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader

A parliamentary leader is a political title or a descriptive term used in various countries to designate the person leading a parliamentary group or caucus in a legislative body, whether it be a national or sub-national legislature. They are the ...

from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire

Lanarkshire, also called the County of Lanark ( gd, Siorrachd Lannraig; sco, Lanrikshire), is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the central Lowlands of Scotland.

Lanarkshire is the most populous county in Scot ...

. He started working at the age of seven, and from the age of 10 worked in the Lanarkshire coal mines. With a background in preaching, he became known as a talented public speaker and was chosen as a spokesman for his fellow miners. In 1879, Hardie was elected leader of a miners' union in Hamilton and organised a National Conference of Miners in Dunfermline. He subsequently led miners' strikes in Lanarkshire (1880) and Ayrshire

Ayrshire ( gd, Siorrachd Inbhir Àir, ) is a Counties of Scotland, historic county and registration county in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine, North Ayrshi ...

(1881). He turned to journalism to make ends meet, and from 1886 was a full-time union organiser as secretary of the Ayrshire Miners' Union.

Hardie initially supported William Gladstone's Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a l ...

, but later concluded that the working class needed its own party. He first stood for parliament in 1888 as an independent, and later that year helped form the Scottish Labour Party

Scottish Labour ( gd, Pàrtaidh Làbarach na h-Alba, sco, Scots Labour Pairty; officially the Scottish Labour Party) is a social democratic political party in Scotland. It is an autonomous section of the UK Labour Party. From their peak o ...

. Hardie won the English seat of West Ham South as an independent candidate in 1892, and helped to form the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberal Party (UK), Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse worki ...

(ILP) the following year. He lost his seat in 1895, but was re-elected to Parliament in 1900 for Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil (; cy, Merthyr Tudful ) is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Ty ...

in South Wales. In the same year he helped to form the union-based Labour Representation Committee, which was later renamed the Labour Party.

After the 1906 election, Hardie was chosen as the Labour Party's first parliamentary leader. He resigned in 1908 in favour of Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the first Labour cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniquely, served three separate terms as Leader of t ...

, and spent his remaining years campaigning for causes such as women's suffrage, self-rule for India, and opposition to World War I. He died in 1915 while attempting to organise a pacifist general strike. Hardie is seen as a key figure in the history of the Labour Party and has been the subject of multiple biographies. Kenneth O. Morgan has called him "Labour's greatest pioneer and its greatest hero".

Early life

James Keir Hardie was born on 15 August 1856 in a two-roomed cottage on the western edge of Newhouse,

James Keir Hardie was born on 15 August 1856 in a two-roomed cottage on the western edge of Newhouse, Lanarkshire

Lanarkshire, also called the County of Lanark ( gd, Siorrachd Lannraig; sco, Lanrikshire), is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the central Lowlands of Scotland.

Lanarkshire is the most populous county in Scot ...

near Holytown

Holytown ( sco, 'Holy-Town' - Holytown, gd, Baile a' Chuilinn)

, a small town close to Motherwell

Motherwell ( sco, Mitherwall, gd, Tobar na Màthar) is a town and former burgh in North Lanarkshire, Scotland, United Kingdom, south east of Glasgow. It has a population of around 32,120. Historically in the parish of Dalziel and part of Lana ...

in Scotland. His mother, Mary Keir, was a domestic servant

A domestic worker or domestic servant is a person who works within the scope of a residence. The term "domestic service" applies to the equivalent occupational category. In traditional English contexts, such a person was said to be "in service ...

and his stepfather, David Hardie, was a ship's carpenter. Hardie had little or no contact with his biological father, a miner from Lanarkshire named William Aitken. The growing family soon moved to the shipbuilding burgh of Govan

Govan ( ; Cumbric?: ''Gwovan'?''; Scots: ''Gouan''; Scottish Gaelic: ''Baile a' Ghobhainn'') is a district, parish, and former burgh now part of south-west City of Glasgow, Scotland. It is situated west of Glasgow city centre, on the south b ...

near Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated pop ...

(which wasn't incorporated into the city until 1912), where they made a life in a very difficult financial situation, with his stepfather attempting to maintain continuous employment in the shipyards rather than practising his trade at sea – never an easy proposition given the boom-and-bust cycle of the industry.

Hardie's first job, when aged seven, was as a message boy for the Anchor Line Steamship Company. Formal schooling henceforth became impossible, but his parents spent evenings teaching him to read and write, skills which proved essential for future self-education

Autodidacticism (also autodidactism) or self-education (also self-learning and self-teaching) is education without the guidance of masters (such as teachers and professors) or institutions (such as schools). Generally, autodidacts are individu ...

. A series of low-paying entry-level jobs followed for the boy, including work as an apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

in a brass-fitting shop, work for a lithographer

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone ( lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German ...

, employment in the shipyards heating rivets, and time spent as a message boy for a baker

A baker is a tradesperson who bakes and sometimes sells breads and other products made of flour by using an oven or other concentrated heat source. The place where a baker works is called a bakery.

History

Ancient history

Since grains ...

for which he earned four shillings and sixpence a week.

A great lockout

Lockout may refer to:

* Lockout (industry), a type of work stoppage

** Dublin Lockout, a major industrial dispute between approximately 20,000 workers and 300 employers 1913 - 1914

* Lockout (sports), lockout in sports leagues

**MLB lockout, loc ...

of the Clydeside

Greater Glasgow is an urban settlement in Scotland consisting of all localities which are physically attached to the city of Glasgow, forming with it a single contiguous urban area (or conurbation). It does not relate to municipal government ...

shipworkers took place in which the unionised workers were sent home for a period of six months. With their main source of income terminated, the family was forced to sell all their possessions to pay for food, with Hardie's meagre earnings the only remaining source of income for the household. One sibling took ill and died in the miserable conditions which followed, while the pregnancy of his mother limited her own ability to work. Making matters worse, young James lost his job for turning up late on two occasions. In desperation, his stepfather returned to work at sea, while his mother moved from Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated pop ...

to Newarthill

Newarthill is a village in North Lanarkshire, Scotland, situated roughly three miles north-east of the town of Motherwell. It has a population of around 6,200. Most local amenities are shared with the adjacent villages of Carfin, Holytown and ...

, where his maternal grandmother still lived.

At the age of ten years old, Hardie went to work in the mines as a "trapper": opening and closing a door for a ten-hour shift in order to maintain the air supply for miners in a given section. Hardie also began to attend night school in Holytown

Holytown ( sco, 'Holy-Town' - Holytown, gd, Baile a' Chuilinn)

at this time.

Hardie's stepfather returned from sea and went to work on a railway line being constructed between Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

and Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated pop ...

. When this job was completed, the family moved to the village of Quarter, Lanarkshire, where Hardie went to work as a pony driver at the mines, later working his way into the pits as a hewer. He also worked for two years above ground in the quarries

A quarry is a type of open-pit mine in which dimension stone, rock, construction aggregate, riprap, sand, gravel, or slate is excavated from the ground. The operation of quarries is regulated in some jurisdictions to reduce their environ ...

. By the time he was twenty, he had become a skilled practical miner.

"Keir", as he was now called, longed for a life outside the mines. To that end, encouraged by his mother, he had learned to read and write in shorthand

Shorthand is an abbreviated symbolic writing method that increases speed and brevity of writing as compared to longhand, a more common method of writing a language. The process of writing in shorthand is called stenography, from the Greek ''st ...

. He also began to associate with the Evangelical Union becoming a member of the Evangelical Union Church, Park Street, Hamilton – now the United Reformed Church, Hamilton (which also incorporates St James' Congregational Church, attended by the young David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of ...

, the future famous missionary explorer) – and to participate in the Temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

. Hardie's avocation

An avocation is an activity that someone engages in as a hobby outside their main occupation. There are many examples of people whose professions were the ways that they made their livings, but for whom their activities outside their workplaces w ...

of preaching put him before crowds of his fellows, helping him to learn the art of public speaking

Public speaking, also called oratory or oration, has traditionally meant the act of speaking face to face to a live audience. Today it includes any form of speaking (formally and informally) to an audience, including pre-recorded speech delive ...

. Before long, Hardie was looked to by other miners as a logical chairman for their meetings and spokesman for their grievances. Mine owners began to see him as an agitator and in fairly short order, he and two younger brothers were blacklist

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist (or black list) of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list. If someone is on a blacklist, ...

ed from working in the local mining industry.

Union leader

The 23-year-old Hardie moved from the coal mines to union organisation work.

In May 1879, Scottish mine owners combined to force a reduction of wages, which had the effect of spurring the demand for unionisation. Huge meetings were held weekly at Hamilton as mine workers joined to vent their grievances. On 3 July 1879, Hardie was appointed Corresponding Secretary of the miners, a post which gave him opportunity to get in touch with other representatives of the mine workers throughout southern Scotland. Three weeks later, Hardie was chosen by the miners as their delegate to a National Conference of Miners to be held in Glasgow. He was appointed Miners' Agent in August 1879 and his new career as a trade union organiser and functionary was launched.

On 16 October 1879, Hardie attended a National Conference of miners at Dunfermline, at which he was selected as National Secretary, a high-sounding title which actually preceded the establishment of a coherent national organisation by several years. Hardie was active in the strike wave which swept the region in 1880, including a generalised strike of the mines of

The 23-year-old Hardie moved from the coal mines to union organisation work.

In May 1879, Scottish mine owners combined to force a reduction of wages, which had the effect of spurring the demand for unionisation. Huge meetings were held weekly at Hamilton as mine workers joined to vent their grievances. On 3 July 1879, Hardie was appointed Corresponding Secretary of the miners, a post which gave him opportunity to get in touch with other representatives of the mine workers throughout southern Scotland. Three weeks later, Hardie was chosen by the miners as their delegate to a National Conference of Miners to be held in Glasgow. He was appointed Miners' Agent in August 1879 and his new career as a trade union organiser and functionary was launched.

On 16 October 1879, Hardie attended a National Conference of miners at Dunfermline, at which he was selected as National Secretary, a high-sounding title which actually preceded the establishment of a coherent national organisation by several years. Hardie was active in the strike wave which swept the region in 1880, including a generalised strike of the mines of Lanarkshire

Lanarkshire, also called the County of Lanark ( gd, Siorrachd Lannraig; sco, Lanrikshire), is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the central Lowlands of Scotland.

Lanarkshire is the most populous county in Scot ...

that summer which lasted six weeks. The fledgling union had no money, but worked to gather foodstuffs for striking mine families, as Hardie and other union agents got local merchants to supply goods upon promise of future payment. A soup kitchen was kept running in Hardie's home during the course of the strike, manned by his new wife, the former Lillie Wilson.

While the Lanarkshire mine strike was a failure, Hardie's energy and activity shone and he accepted a call from Ayrshire

Ayrshire ( gd, Siorrachd Inbhir Àir, ) is a Counties of Scotland, historic county and registration county in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine, North Ayrshi ...

to relocate there to organise the local miners. The young couple moved to the town of Cumnock

Cumnock (Scottish Gaelic: ''Cumnag'') is a town and former civil parish located in East Ayrshire, Scotland. The town sits at the confluence of the Glaisnock Water and the Lugar Water. There are three neighbouring housing projects which lie just o ...

, where Keir set to work organising a union of local miners, a process which occupied nearly a year.

In August 1881, Ayrshire miners put forward the demand for a 10 percent increase in wages, a proposition summarily refused by the region's mine owners. Despite the lack of funds for strike pay, a stoppage was called and a 10-week shutdown of the region's mines ensued. This strike also was formally a failure, with miners returning to work before their demands had been met, but not long after the return wages were escalated across the board by the mine owners, fearful of future labour actions. One of the other leaders of the strike was 19-year-old miner

In August 1881, Ayrshire miners put forward the demand for a 10 percent increase in wages, a proposition summarily refused by the region's mine owners. Despite the lack of funds for strike pay, a stoppage was called and a 10-week shutdown of the region's mines ensued. This strike also was formally a failure, with miners returning to work before their demands had been met, but not long after the return wages were escalated across the board by the mine owners, fearful of future labour actions. One of the other leaders of the strike was 19-year-old miner Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher (29 August 186222 October 1928) was an Australian politician who served three terms as prime minister of Australia – from 1908 to 1909, from 1910 to 1913, and from 1914 to 1915. He was the leader of the Australian Labor Party ...

, who decades later would become leader of the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms ...

and Prime Minister of Australia. He and Hardie met regularly to discuss politics when they both lived in Ayrshire, and would renew their acquaintance on a number of occasions later in life.

To make ends meet, Hardie turned to journalism, starting to write for the local newspaper, the ''Cumnock News,'' a paper loyal to the pro-labour Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a l ...

. As part of the natural order of things, Hardie joined the Liberal Association, in which he was active. He also continued his temperance work as an active member of the local Good Templar's Lodge.

In August 1886, Hardie's ongoing efforts to build a powerful union of Scottish miners were rewarded when there was formed the Ayrshire Miners Union. Hardie was named Organising Secretary of the new union, drawing a salary of £75 per year.

In 1887, Hardie launched a new publication called ''The Miner''.

Scottish Labour Party

Hardie was a dedicated

Hardie was a dedicated Georgist

Georgism, also called in modern times Geoism, and known historically as the single tax movement, is an economic ideology holding that, although people should own the value they produce themselves, the economic rent derived from land—including ...

for a number of years and a member of the Scottish Land Restoration League

The Scottish Land Restoration League was a Georgist political party.

History

In the 1880s, enclosure was still in process in the Scottish Highlands, and resistance to it often received support from radicals around Britain and Ireland. Branches ...

. It was "through the single tax" on land monopoly that Hardie gradually became a Fabian socialist. He reasoned that "whatever the idea may be, State socialism is necessary as a stage in the development of the ideal." Despite his early support of the Liberal Party, Hardie became disillusioned by William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-con ...

's economic policies and began to feel that the Liberals would not advocate the interests of the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colo ...

. Hardie concluded that the Liberal Party wanted the worker's votes without in return the radical reform he believed to be crucial – he stood for Parliament.

In April 1888, Hardie was an Independent Labour candidate at the Mid Lanarkshire by-election. He finished last but he was not deterred by this, and believed he would enjoy more success in the future. At a public meeting in Glasgow on 25 August 1888 the Scottish Labour Party

Scottish Labour ( gd, Pàrtaidh Làbarach na h-Alba, sco, Scots Labour Pairty; officially the Scottish Labour Party) is a social democratic political party in Scotland. It is an autonomous section of the UK Labour Party. From their peak o ...

(a different party from the 1994-created Scottish Labour Party

Scottish Labour ( gd, Pàrtaidh Làbarach na h-Alba, sco, Scots Labour Pairty; officially the Scottish Labour Party) is a social democratic political party in Scotland. It is an autonomous section of the UK Labour Party. From their peak o ...

) was founded, with Hardie becoming the party's first secretary. The party's president was Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham, the first socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

MP, and later founder of the National Party of Scotland

The National Party of Scotland (NPS) was a centre-left political party in Scotland which was one of the predecessors of the current Scottish National Party (SNP). The NPS was the first Scottish nationalist political party, and the first which c ...

, forerunner to the Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party (SNP; sco, Scots National Pairty, gd, Pàrtaidh Nàiseanta na h-Alba ) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic political party in Scotland. The SNP supports and campaigns for Scottish independence from ...

.

MP for West Ham South

Hardie was invited to stand in West Ham South in 1892, a working-class seat inEssex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

(now Greater London

Greater may refer to:

* Greatness, the state of being great

*Greater than, in inequality

* ''Greater'' (film), a 2016 American film

* Greater (flamingo), the oldest flamingo on record

* "Greater" (song), by MercyMe, 2014

* Greater Bank, an Austra ...

). The Liberals decided not to field a candidate, but at the same time not to offer Hardie any assistance. Competing against the Conservative Party candidate, Hardie won by 5,268 votes to 4,036. He was variously described as the Labour or " Liberal and Labour" candidate. Upon taking his seat on 3 August 1892, Hardie refused to wear the "parliamentary uniform" of black frock coat

A frock coat is a formal men's coat characterised by a knee-length skirt cut all around the base just above the knee, popular during the Victorian and Edwardian periods (1830s–1910s). It is a fitted, long-sleeved coat with a centre vent at the ...

, black silk top hat

A top hat (also called a high hat, a cylinder hat, or, informally, a topper) is a tall, flat-crowned hat for men traditionally associated with formal wear in Western dress codes, meaning white tie, morning dress, or frock coat. Traditionally m ...

and starched wing collar

In clothing, a collar is the part of a shirt, dress, coat (clothing), coat or blouse that fastens around or frames the neck. Among clothing construction professionals, a collar is differentiated from other necklines such as revers and lapels, b ...

that other working-class MPs wore. Instead, Hardie wore a plain tweed suit

A suit, lounge suit, or business suit is a set of clothes comprising a suit jacket and trousers of identical textiles worn with a collared dress shirt, necktie, and dress shoes. A skirt suit is similar, but with a matching skirt instead of ...

, a red tie and a deerstalker

A deerstalker is a type of cap that is typically worn in rural areas, often for hunting, especially deer stalking. Because of the cap's popular association with the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, it has become stereotypical headgear ...

. Although the deerstalker hat was the correct and matching apparel for his suit, he was nevertheless lambasted in the press, and was accused of wearing a flat cap, headgear associated with the common working man; "cloth cap in Parliament". In Parliament, Hardie advocated a graduated income tax, free schooling, pensions, the abolition of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster ...

and for women's right to vote.

Independent Labour Party

In 1893, Hardie and others formed theIndependent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberal Party (UK), Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse worki ...

, an action that worried the Liberals, who were afraid that the ILP might, at some point in the future, win the working-class votes that they traditionally received.

Hardie hit the headlines in 1894, when after an explosion at the Albion colliery in Cilfynydd near Pontypridd

() ( colloquially: Ponty) is a town and a community in Rhondda Cynon Taf, Wales.

Geography

comprises the electoral wards of , Hawthorn, Pontypridd Town, 'Rhondda', Rhydyfelin Central/Ilan ( Rhydfelen), Trallwng ( Trallwn) and Treforest () ...

which killed 251 miners, he asked that a message of condolence to the relatives of the victims be added to an address of congratulations on the birth of a royal heir (the future Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire and Emperor of India from 20 January ...

). The request was refused and Hardie made a speech attacking the monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy ...

, which almost predicted the nature of the future king's marriage that led to his abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

.

This speech in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

was highly controversial and contributed to the loss of his seat in 1895.

Labour Party

Hardie spent the next five years of his life building up the Labour movement and speaking at various public meetings; he was arrested at a

Hardie spent the next five years of his life building up the Labour movement and speaking at various public meetings; he was arrested at a woman's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

meeting in London, but the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

, concerned about arresting the leader of the ILP, ordered his release.

In 1900 Hardie organised a meeting of various trade unions and socialist groups; they agreed to form a Labour Representation Committee and so the Labour Party was born. Later that same year Hardie, representing Labour, was elected as the junior MP for the dual-member constituency of Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil (; cy, Merthyr Tudful ) is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Ty ...

in the South Wales Valleys, which he would represent for the remainder of his life. Only one other Labour MP was elected that year ( Richard Bell for Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby gain ...

), but from these small beginnings the party continued to grow, forming the first-ever Labour government in 1924.

Meanwhile, the Conservative and Liberal Unionist

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

coalition government became deeply unpopular, and Liberal leader Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman ( né Campbell; 7 September 183622 April 1908) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. He served as the prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1905 to 1908 and leader of the Liberal Party from 1899 t ...

was worried about possible vote-splitting across the Labour and Liberal parties in the next election. A deal was struck in 1903, which became known as the Lib-Lab pact of 1903 or Gladstone-MacDonald pact. It was engineered by Ramsay MacDonald and Liberal Chief Whip Herbert Gladstone

Herbert John Gladstone, 1st Viscount Gladstone, (7 January 1854 – 6 March 1930) was a British Liberal politician. The youngest son of William Ewart Gladstone, he was Home Secretary from 1905 to 1910 and Governor-General of the Union of S ...

: the Liberals would not stand against Labour in thirty constituencies

An electoral district, also known as an election district, legislative district, voting district, constituency, riding, ward, division, or (election) precinct is a subdivision of a larger state (a country, administrative region, or other polit ...

in the next election, in order to avoid splitting the anti-Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

vote.

In 1905 Hardie served as an LRC election agent for William Walker who came close to victory with 48.5% of the vote in Belfast North. Despite his own support for Irish home rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1 ...

, Hardie, who made repeated visits, appeared determined to treat Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingd ...

as a "typical British city", confident that class politics could surmount sectarian division over the constitutional question.

In 1906, the LRC changed its name to the "Labour Party". That year, the newly established Liberal government of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman called a General Election — resulting in a heavy defeat for the Conservative Party (then in opposition), and the landslide affirmation of the Liberals.

The 1906 general election

The following elections occurred in the year 1906.

Asia

* 1906 Persian legislative election

Europe

* 1906 Belgian general election

* 1906 Croatian parliamentary election

* Denmark

** 1906 Danish Folketing election

** 1906 Danish Landsting ele ...

result was one of the biggest landslide victories in British history: the Liberals swept the Conservatives (and their Liberal Unionist allies) out of what were regarded as safe seat

A safe seat is an electoral district (constituency) in a legislative body (e.g. Congress, Parliament, City Council) which is regarded as fully secure, for either a certain political party, or the incumbent representative personally or a combinat ...

s. Conservative leader and former Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As foreign secretary in the L ...

, lost his seat, Manchester East, on a swing of over 20 percent. What would later turn out to be even more significant was the election of 29 Labour MPs.

In January 1907 at the Labour Party's first annual conference, held in Belfast, Hardie helped raise the issue of whether sovereignty lay with the annual conference, as in the inherited tradition of trade union democracy, or with the PLP. In the closing session he shocked the delegates by threatening to resign from the PLP over an amendment to a resolution on equal suffrage for women that would have bound him as an MP to oppose any compromise legislation that would extend votes to women on the basis of the existing property franchise. This, he saw, as potentially delaying the extension of "citizenship" to women on which he spoke passionately:I thought the days of my pioneering were over but of late I have felt, with increasing intensity, the injustice inflicted on women by our present laws. The Party is largely my own child and I cannot part from it lightly, or without pain; but at the same time I cannot sever myself from the principles I hold. If it is necessary for me to separate myself from what has been my life's work, I do so in order to remove the stigma resting upon our wives, mothers and sisters of being accounted unfit for citizenship.The PLP defused the crisis by allowing Hardie to vote as he wished on the subject. The precedent became the basis of a "conscience clause" in its standing orders, and would be invoked by party leader

Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Labour Leader from 1980 to 1983. Foot began his career as a journalist on ''Tribune'' and the '' Evening Standard''. He co-wrote the 1940 ...

in 1981 to argue that the will of the conference should not always bind the PLP.

Hardie, never good at dealing with internal dissension, did resign his chairmanship of the party the following year, 1908. He was replaced by Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the first Labour cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniquely, served three separate terms as Leader of t ...

.

Hardie in his evidence to the 1899 House of Commons Select Committee on emigration and immigration, argued that the Scots resented immigrants greatly and that they would want a total immigration ban. When it was pointed out to him that more people left Scotland than entered it, he replied, "It would be much better for Scotland if those 1,500 were compelled to remain there and let the foreigners be kept out... Dr Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford D ...

said God made Scotland for Scotchmen, and I would keep it so." According to Hardie, the Lithuanian migrant workers in the mining industry had "filthy habits", they lived off "garlic and oil", and they were carriers of "the Black Death".

In 1908, when visiting South Africa, he said the Socialist movement stood for equal rights for every race but that "we do not say all races are equal; no one dreams of doing that". On return to the UK he stated his belief that black people should be given the opportunity to vote and to take a full part in society.

Later career

After resigning the leadership of the party in 1908, Hardie devoted himself to campaigning for votes for women and developing a closer relationship with

After resigning the leadership of the party in 1908, Hardie devoted himself to campaigning for votes for women and developing a closer relationship with Sylvia Pankhurst

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst (5 May 1882 – 27 September 1960) was a campaigning English Feminism, feminist and Socialism, socialist. Committed to organising working-class women in East End of London, London's East End, and unwilling in United King ...

. His secretary Margaret Symons Travers was the first woman to speak in the Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north bank ...

when she tricked her way in on 13 October 1908.

He also campaigned for self-rule

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form o ...

for India and an end to segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of human ...

in South Africa. During a visit to the United States in 1909, his criticism of sectarianism

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

among American radicals caused intensified debate regarding the American Socialist Party possibly joining with the unions in a labour party.

A pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaig ...

, Hardie was appalled by the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

and along with socialists in other countries he tried to organise an international general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coa ...

to stop the war. His stance was not popular, even within the Labour Party, but he continued to address anti-war demonstrations across the country and to support conscientious objector

A conscientious objector (often shortened to conchie) is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, or religion. The term has also been extended to obje ...

s. After the outbreak of war, on 4 August 1914, Hardie's spirited anti-war speeches often received opposition in the form of loud heckling. Hardie was among many Scottish socialists, the likes of John MacLean and Willie Gallacher, who opposed the War and believed that working-class men fighting other working-class men only served the interests of capitalism.

Despite this, once the war had started Hardie seems to have resigned himself to the inevitability of pursuing it rather than stopping it immediately. In a full-page article in the '' Merthyr Pioneer'' on 28 November 1914, he wrote:

In the same article he also opposed accusations that he was unpatriotic by claiming that his meetings encouraged young men to enlist while those of his Liberal opponents did the opposite:

After a series of strokes, Hardie died in a hospital in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated pop ...

of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

at noon on 26 September 1915, aged 59. His friend and fellow pacifist Thomas Evan Nicholas (Niclas y Glais) delivered the sermon at Hardie's memorial service at Aberdare, in his constituency.

He was cremated in Maryhill, Glasgow. A memorial stone in his honour is at Cumnock Cemetery Cumnock

Cumnock (Scottish Gaelic: ''Cumnag'') is a town and former civil parish located in East Ayrshire, Scotland. The town sits at the confluence of the Glaisnock Water and the Lugar Water. There are three neighbouring housing projects which lie just o ...

, Ayrshire

Ayrshire ( gd, Siorrachd Inbhir Àir, ) is a Counties of Scotland, historic county and registration county in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine, North Ayrshi ...

, Scotland.

Legacy

On 2 December 2006, a memorial bust of Hardie was unveiled by

On 2 December 2006, a memorial bust of Hardie was unveiled by Cynon Valley

Cynon Valley () is a former coal mining valley in Wales. Cynon Valley lies between Rhondda and the Merthyr Valley and takes its name from the River Cynon. Aberdare is located in the north of the valley and Mountain Ash is in the south o ...

MP Ann Clwyd outside council offices in Aberdare (in his former constituency). The ceremony marked a centenary since the party's birth.

Hardie is still held in high esteem in his old home town of Holytown

Holytown ( sco, 'Holy-Town' - Holytown, gd, Baile a' Chuilinn)

, where his childhood home is preserved for people to view, while the local sports centre was named in his own honour as "The Keir Hardie Sports Centre". Keir Hardie Memorial Primary School opened in 1956, named for him. There are now 40 streets throughout Britain named after Hardie. Alan Morrison has, in turn, used the title ''Keir Hardie Street'' for his 2010 narrative long poem in which a fictitious, turn-of-the-century, working-class poet discovers a socialist utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island socie ...

off the dreamt-up Sea-Green Line of the London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or by its nickname the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The U ...

.

One of the buildings at Swansea University

, former_names=University College of Swansea, University of Wales Swansea

, motto= cy, Gweddw crefft heb ei dawn

, mottoeng="Technical skill is bereft without culture"

, established=1920 – University College of Swansea 1996 – University of Wa ...

is also named after him, while a main distributor road in Sunderland

Sunderland () is a port city in Tyne and Wear, England. It is the City of Sunderland's administrative centre and in the Historic counties of England, historic county of County of Durham, Durham. The city is from Newcastle-upon-Tyne and is on t ...

is named the Keir Hardie Way.

The Ellen Wilkinson

Ellen Cicely Wilkinson (8 October 1891 – 6 February 1947) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Minister of Education from July 1945 until her death. Earlier in her career, as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Jarrow, s ...

Estate in Wardley, East Gateshead (once in the Urban District of Felling, subsumed by Gateshead Metropolitan Borough in 1974) has Keir Hardie Avenue as its main street. Every other street is named after a pre-1960 Labour MP. The England footballer, Chris Waddle, lived in Number 1 Keir Hardie Avenue, Gateshead, between 1971 and 1983.

The Keir Hardie Estate in Canning Town

Canning Town is a district in the London Borough of Newham, East London. The district is located to the north of the Royal Victoria Dock, and has been described as the "Child of the Victoria Docks" as the timing and nature of its urbanisation wa ...

(Newham

The London Borough of Newham is a London borough created in 1965 by the London Government Act 1963. It covers an area previously administered by the Essex county boroughs of West Ham and East Ham, authorities that were both abolished by the ...

, East London) is named after him as a legacy to his tenure as MP for West Ham South, Newham. Keir Hardie Avenue in the town of Cleator Moor, Cumbria, has been named after him since 1934 Furthermore, an estate in the London Borough of Brent was also named after Hardie. Keir Hardie Crescent in Kilwinning

Kilwinning (, sco, Kilwinnin; gd, Cill D’Fhinnein) is a town in North Ayrshire, Scotland. It is on the River Garnock, north of Irvine, about southwest of Glasgow. It is known as "The Crossroads of Ayrshire". Kilwinning was also a Civil P ...

in Scotland is named after him, as is a block of apartments in Little Thurrock

Little Thurrock () is an area, ward, former civil parish and Church of England parish in the town of Grays, in the unitary authority of Thurrock, Essex. In 1931 the parish had a population of 4428.

Location

Little Thurrock is on the north bank ...

. There is also a Keir Hardie Street in Greenock and a Keir Hardie Street in Methil, Fife, a predominantly Labour stronghold.

Ty Keir Hardie, in his constituency town of Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil (; cy, Merthyr Tudful ) is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Ty ...

, housed offices for Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council

Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council ( cy, Cyngor bwrdeistref Sirol Merthyr Tudful) is the governing body for Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, one of the Principal Areas of Wales.

History

The parish of Merthyr Tydfil was governed by a local boa ...

and adjoins the Civic Centre on Castle Street. In Merthyr Tydfil, there is also a Keir Hardie Estate with streets named after prominent early Independent Labour leaders such as Wallhead and Glasier.

In recognition of his work as a lay preacher, the Keir Hardie Methodist Church in London bears his name.

Labour founder Hardie has been voted the party's "greatest hero" in a straw poll of delegates at the 2008 Labour conference in Manchester. Labour peer Lord Morgan, Ed Balls

Edward Michael Balls (born 25 February 1967) is a British broadcaster, writer, economist, professor and former politician who served as Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families from 2007 to 2010, and as Shadow Chancellor of the Exc ...

, David Blunkett

David Blunkett, Baron Blunkett, (born 6 June 1947) is a British Labour Party politician who has been a Member of the House of Lords since 2015, and previously served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Sheffield Brightside and Hillsborough ...

and Fiona Mactaggart

Fiona Margaret Mactaggart (born 12 September 1953) is a British politician and former primary school teacher who has been chair of the Fawcett Society since 2018. A member of the Labour Party, she was Member of Parliament (MP) for Slough from 1 ...

argued the case for four Labour figures at a ''Guardian'' fringe meeting at the Labour conference 2008 in Manchester, 23 September 2008.

Hardie's younger half-brothers David Hardie, George Hardie and sister-in-law Agnes Hardie

Agnes Agnew Hardie (née Pettigrew; 6 September 1874 – 24 March 1951) was a British Labour politician.

Early life

Her association with the Labour movement began when she was a shop girl in Glasgow."Glasgow's First Woman M.P." ''Glasgow H ...

all became Labour Party Members of Parliament after his death. His daughter Nan Hardie and her husband Emrys Hughes both became Provost of Cumnock

Cumnock (Scottish Gaelic: ''Cumnag'') is a town and former civil parish located in East Ayrshire, Scotland. The town sits at the confluence of the Glaisnock Water and the Lugar Water. There are three neighbouring housing projects which lie just o ...

; Hughes also became Labour Member of Parliament for South Ayrshire

South Ayrshire ( sco, Sooth Ayrshire; gd, Siorrachd Àir a Deas, ) is one of thirty-two council areas of Scotland, covering the southern part of Ayrshire. It borders onto Dumfries and Galloway, East Ayrshire and North Ayrshire. On 30 June ...

in 1946.

Biographer Kenneth O. Morgan has sketched Hardie's personality:

Keir Starmer

Sir Keir Rodney Starmer (; born 2 September 1962) is a British politician and barrister who has served as Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party since 2020. He has been Member of Parliament (MP) for Holborn and St Pancras ...

, the current Leader of the Labour Party and serving MP in the House of Commons for Holborn and St Pancras

Holborn and St Pancras () is a parliamentary constituency in Greater London that was created in 1983. It has been represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom since 2015 by Sir Keir Starmer, the current Leade ...

, was named after Hardie; he said he was "very fond of the name".

Keir Hardie Society

On 15 August 2010 (the 154th anniversary of Hardie's birth) the Keir Hardie Society was founded at Summerlee, Museum of Scottish Industrial Life. The society aims to "keep alive the ideas and promote the life and work of Keir Hardie". Among the co-founders wasCathy Jamieson

Catherine Mary Jamieson (born 3 November 1956) is a Scottish business director, currently a director at Kilmarnock Football Club and former politician. She served as the Deputy Leader of the Labour Party in Scotland from 2000 to 2008. She p ...

, who at the time was the MSP for the constituency of Carrick, Cumnock and Doon Valley, which covers the area where Hardie lived most of his life. Scottish Labour

Scottish Labour ( gd, Pàrtaidh Làbarach na h-Alba, sco, Scots Labour Pairty; officially the Scottish Labour Party) is a social democratic political party in Scotland. It is an autonomous section of the UK Labour Party. From their peak o ...

leader Richard Leonard

Richard Leonard (born January 1962) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Scottish Labour Party from 2017 to 2021. He has been a Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP), as one of the additional members for the Central Scotlan ...

was the main founder of the society, along with Hugh Gaffney MP.

In other media

In August 2016,Jim Kenworth

Jim Kenworth is an English playwright.

Career

Kenworth made his debut as a playwright with the premiere of ''Johnny Song'' at the Warehouse Theatre, Croydon in 1998. His second play, ''Gob'', was presented at The King's Head Theatre, Islingt ...

's play ''A Splotch of Red: Keir Hardie in West Ham'' was premiered at various venues in Newham

The London Borough of Newham is a London borough created in 1965 by the London Government Act 1963. It covers an area previously administered by the Essex county boroughs of West Ham and East Ham, authorities that were both abolished by the ...

, including Neighbours Hall in Canning Town

Canning Town is a district in the London Borough of Newham, East London. The district is located to the north of the Royal Victoria Dock, and has been described as the "Child of the Victoria Docks" as the timing and nature of its urbanisation wa ...

at which Hardie spoke. The play deals with Hardie's battle to win the constituency of West Ham South. It was directed by James Martin Charlton; Samuel Caseley played Keir Hardie.

Works

* ''From Serfdom to Socialism'' (1907) * ''Karl Marx: The Man and His Message'' (1910) *See also

*List of peace activists

This list of peace activists includes people who have proactively advocated diplomatic, philosophical, and non-military resolution of major territorial or ideological disputes through nonviolent means and methods. Peace activists usually work ...

*List of suffragists and suffragettes

This list of suffragists and suffragettes includes noted individuals active in the worldwide women's suffrage movement who have campaigned or strongly advocated for women's suffrage, the organisations which they formed or joined, and the public ...

References

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * *External links

*J. Keir Hardie Biography

Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

at

Marxists Internet Archive

Marxists Internet Archive (also known as MIA or Marxists.org) is a non-profit online encyclopedia that hosts a multilingual library (created in 1990) of the works of communist, anarchist, and socialist writers, such as Karl Marx, Friedrich En ...

. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

Rhondda Cynon Taff Online: Unveiling the Keir Hardie Bust

Retrieved 7 October 2009. * *

Scottish Labour Party, History

Kier Hardie – Labour's First MP

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Hardie, Keir 1856 births 1915 deaths British anti–World War I activists British pacifists British republicans British socialists British suffragists Chairs of the Labour Party (UK) Coal miner activists Congregationalist socialists European democratic socialists Independent Labour Party MPs Independent Labour Party National Administrative Committee members Leaders of the Labour Party (UK) Liberal Party (UK) politicians Labour Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Welsh Labour Party MPs People from Lanarkshire Politics of Merthyr Tydfil Scottish Christian socialists Scottish journalists Scottish Labour Party (1888) politicians Scottish pacifists Scottish socialists UK MPs 1892–1895 UK MPs 1900–1906 UK MPs 1906–1910 UK MPs 1910–1918 UK MPs 1910 British political party founders Deaths from pneumonia in Scotland