James Graham, 5th Earl Of Montrose on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose (1612 – 21 May 1650) was a Scottish nobleman,

The king signed a warrant for his

The king signed a warrant for his  Now Montrose found himself apparently master of Scotland. After Kilsyth, the king's secretary arrived with letters from Charles documenting that Montrose was lieutenant and captain general. He first conferred knighthood on Alasdair. Then he summoned a parliament to meet at

Now Montrose found himself apparently master of Scotland. After Kilsyth, the king's secretary arrived with letters from Charles documenting that Montrose was lieutenant and captain general. He first conferred knighthood on Alasdair. Then he summoned a parliament to meet at  Montrose was to appear once more on the stage of Scottish history. In June 1649, eager to avenge the death of the King, he was restored by the exiled Charles II to the now nominal lieutenancy of Scotland. Charles, however, did not scruple soon afterwards to disavow his noblest supporter to become King on terms dictated by Argyll and his adherents. In March 1650 Montrose landed in

Montrose was to appear once more on the stage of Scottish history. In June 1649, eager to avenge the death of the King, he was restored by the exiled Charles II to the now nominal lieutenancy of Scotland. Charles, however, did not scruple soon afterwards to disavow his noblest supporter to become King on terms dictated by Argyll and his adherents. In March 1650 Montrose landed in

In 1646 Montrose laid siege to the

In 1646 Montrose laid siege to the

Ais-Eiridh na Sean Chánoin Albannaich / The resurrection of the ancient Scottish language

1751 at the

Res gestae

', etc. (Amsterdam, 1647), published in English as ''Memoirs of the Most Renowned James Graham, Marquis of Montrose'';

Montrose and Covenanters

'; his

Memorials of Montrose

' is abundantly documented, containing Montrose's poetry, including the celebrated lyric "My dear and only love.

1st Marquis of Montrose Society

* ttp://www.lyrics85.com/STEELEYE-SPAN-MONTROSE-LYRICS/116787/ Lyrics to "Montrose" by Steeleye Span

Discussion thread at the Mudcat Cafe

– a website for folk musicians (

Mudcat Cafe thread about the Steeleye Span song about Montrose

(scroll down 2/3 for lyrics)

Civil War re-enactors

– includes regiments associated with Montrose such as Manus O'Cahan's Regiment. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Montrose, James Graham, 1st Marquess of Scottish generals Scottish politicians 17th-century Scottish writers 17th-century Scottish peers Covenanters Alumni of the University of St Andrews Knights of the Garter 1612 births 1650 deaths 17th-century executions by Scotland People from Angus, Scotland Executed Scottish people Scottish poets People executed by the Kingdom of Scotland by hanging Members of the Parliament of Scotland 1639–1641 Marquesses of Montrose Burials at the kirkyard of St Giles Field marshals of the Holy Roman Empire

poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or writte ...

and soldier

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a conscripted or volunteer enlisted person, a non-commissioned officer, or an officer.

Etymology

The word ''soldier'' derives from the Middle English word , from Old French ...

, lord lieutenant

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibility ...

and later viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

and captain general of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

. Montrose initially joined the Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

s in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities united in a pers ...

, but subsequently supported King Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

as the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

developed. From 1644 to 1646, and again in 1650, he fought in the civil war in Scotland on behalf of the King. He is referred to as the Great Montrose.

Following his defeat and capture at the Battle of Carbisdale

The Battle of Carbisdale (also known as Invercarron) took place close to the village of Culrain, Sutherland, Scotland on 27 April 1650 and was part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It was fought by the Royalist leader James Graham, 1st Marq ...

, Montrose was tried by the Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament ( gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba ; sco, Scots Pairlament) is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Scotland. Located in the Holyrood area of the capital city, Edinburgh, it is frequently referred to by the metonym Holyro ...

and sentenced to death by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

, followed by beheading

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the i ...

and quartering. After the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

, Charles II paid £802 sterling for a lavish funeral in 1661, when Montrose's reputation changed from traitor

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

or martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

to a romantic hero and subject of works by Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'', ''Rob Roy (n ...

and John Buchan

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (; 26 August 1875 – 11 February 1940) was a Scottish novelist, historian, and Unionist politician who served as Governor General of Canada, the 15th since Canadian Confederation.

After a brief legal career ...

. His spectacular victories, which took his opponents by surprise, are remembered in military history for their tactical brilliance.

Family and education

James Graham, chief of Clan Graham, was the youngest of six children and the only son of John Graham, 4th Earl of Montrose, and Lady Margaret Ruthven. The exact date and place of his birth are unknown, but it was probably in mid-October. His maternal grandparents were William Ruthven, 1st Earl of Gowrie, and Dorothea, a daughter of Henry Stewart, 1st Lord Methven and his second wife Janet Stewart. Her maternal grandparents were John Stewart, 2nd Earl of Atholl and Lady Janet Campbell. Janet Campbell was a daughter of Archibald Campbell, 2nd Earl of Argyll and Elizabeth Stewart. Elizabeth was a daughter ofJohn Stewart, 1st Earl of Lennox

John Stewart, 1st Earl of Lennox (before 14308 July/11 September 1495) was known as Lord Darnley and later as the Earl of Lennox.

Family

Stewart was the son of Catherine Seton and Alan Stewart of Darnley, a direct descendant of Alexander Stew ...

and Margaret Montgomerie. Margaret was a daughter of Alexander Montgomerie, 1st Lord Montgomerie and Margaret Boyd.

Graham studied at age twelve at the college of Glasgow under William Forrett who later tutored his sons. At Glasgow, he read Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, wikt:Ξενοφῶν, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Anci ...

and Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

, and Tasso in translation. In the words of biographer John Buchan

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (; 26 August 1875 – 11 February 1940) was a Scottish novelist, historian, and Unionist politician who served as Governor General of Canada, the 15th since Canadian Confederation.

After a brief legal career ...

, his favourite book was a "splendid folio of the first edition" of ''History of the World'' by Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebellion ...

.

Graham became 5th Earl of Montrose Montrose may refer to:

Places Scotland

* Montrose, Angus (the original after which all others ultimately named or derived)

** Montrose Academy, the secondary school in Montrose

Australia

* Montrose, Queensland (Southern Downs Region), a locality ...

by his father's death in 1626. He was then educated at Saint Salvator's College at the University of St Andrews

(Aien aristeuein)

, motto_lang = grc

, mottoeng = Ever to ExcelorEver to be the Best

, established =

, type = Public research university

Ancient university

, endowment ...

.

At the age of seventeen, he married Magdalene Carnegie, who was the youngest of six daughters of David Carnegie (afterwards Earl of Southesk

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

). They were parents of four sons, among them James Graham, 2nd Marquess of Montrose

James Graham, 2nd Marquess of Montrose ( – February 1669) was a Scottish nobleman and judge, surnamed the "Good" Marquess.

Early life

He was the second son of James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose, by his wife, Lady Magdalene Carnegie, daugh ...

.

Covenanter to royalist

In 1638, after King Charles I had attempted to impose anEpiscopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the l ...

version of the Book of Common Prayer upon the reluctant Scots, resistance spread throughout the country, eventually culminating in the Bishops' Wars

The 1639 and 1640 Bishops' Wars () were the first of the conflicts known collectively as the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which took place in Scotland, England and Ireland. Others include the Irish Confederate Wars, the First and ...

. Montrose joined the party of resistance, and was for some time one of its most energetic champions. He had nothing puritanical

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

in his nature, but he shared in the ill-feeling aroused by the political authority King Charles had given to the bishops. He signed the National Covenant

The National Covenant () was an agreement signed by many people of Scotland during 1638, opposing the proposed reforms of the Church of Scotland (also known as ''The Kirk'') by King Charles I. The king's efforts to impose changes on the church i ...

, and was part of Alexander Leslie

Alexander Leslie, 1st Earl of Leven (15804 April 1661) was a Scottish soldier in Swedish and Scottish service. Born illegitimate and raised as a foster child, he subsequently advanced to the rank of a Swedish Field Marshal, and in Scotland be ...

's army sent to suppress the opposition which arose around Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

and in the country of the Gordons. Though often cited as commander of the expedition, the Aberdeen Council letter books are explicit that the troops entered Aberdeen "under the conduct of General Leslie" who remained in charge in the city until 12 April. Three times Montrose entered Aberdeen. On the second occasion, the leader of the Gordons, the Marquess of Huntly

Marquess of Huntly (traditionally spelled Marquis in Scotland; Scottish Gaelic: ''Coileach Strath Bhalgaidh'') is a title in the Peerage of Scotland that was created on 17 April 1599 for George Gordon, 6th Earl of Huntly. It is the oldest existing ...

entered the city under a pass of safe conduct but ended up accompanying Montrose to Edinburgh, with his supporters saying as a prisoner and in breach of the pass, but Cowan is clear Huntly chose to go voluntarily, rather than as prisoner, noting "by giving out he had been forced to accompany Montrose he was neatly easing his own predicament and at the same time sparing Montrose a great deal of embarrassment". Spalding also supports that Huntly went voluntarily. Montrose was a leader of the delegation who subsequently met at Muchalls Castle

Muchalls Castle stands overlooking the North Sea in the countryside of Kincardine and Mearns, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. The lower course is a well-preserved Romanesque, double-groined 13th-century tower house structure, built by the Frasers of ...

to parley regarding the 1638 confrontation with the Bishop of Aberdeen. With the Earl Marischal

The title of Earl Marischal was created in the Peerage of Scotland for William Keith, the Great Marischal of Scotland.

History

The office of Marischal of Scotland (or ''Marascallus Scotie'' or ''Marscallus Scotiae'') had been hereditary, held by ...

he led a force of 9000 men across the Causey Mounth

The Causey Mounth is an ancient drovers' road over the coastal fringe of the Grampian Mountains in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. This route was developed as the main highway between Stonehaven and Aberdeen around the 12th century AD and it continue ...

through the Portlethen Moss

The Portlethen Moss is an acidic bog nature reserve located to the west of the town of Portlethen, Aberdeenshire in Scotland. Like other Bog, mosses, this wetland area supports a variety of plant and animal species, even though it has been subjec ...

to attack Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

s at the Battle of the Brig of Dee. These events played a part in Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

's decision to grant major concessions to the Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

s.

In July 1639, after the signing of the Treaty of Berwick, Montrose was one of the Covenanting leaders who visited Charles. His change of mind, eventually leading to his support for the King, arose from his wish to get rid of the bishops without making Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

masters of the state. His was essentially a layman's view of the situation. Taking no account of the real forces of the time, he aimed at an ideal form of society in which the clergy should confine themselves to their spiritual duties, and the King should uphold law and order. In the Scottish parliament which met in September, Montrose found himself opposed by Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll

Archibald Campbell, Marquess of Argyll, 8th Earl of Argyll, Chief of Clan Campbell (March 160727 May 1661) was a Scottish nobleman, politician, and peer. The ''de facto'' head of Scotland's government during most of the conflict of the 1640s and ...

, who had gradually assumed leadership of the Presbyterian and national party, and of the estate of burgesses. Montrose, on the other hand, wished to bring the King's authority to bear upon parliament to defeat Argyll, and offered the King the support of a great number of nobles. He failed, because Charles could not even then consent to abandon the bishops, and because no Scottish party of any weight could be formed unless Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

were established as the ecclesiastical power in Scotland.

Rather than give way, Charles prepared in 1640 to invade Scotland. Montrose was of necessity driven to play something of a double game. In August 1640 he signed the Bond of Cumbernauld as a protest against the particular and direct practising of a few, in other words, against the ambition of Argyll. But he took his place amongst the defenders of his country, and in the same month displayed his gallantry in action at the forcing of the River Tyne

The River Tyne is a river in North East England. Its length (excluding tributaries) is . It is formed by the North Tyne and the South Tyne, which converge at Warden Rock near Hexham in Northumberland at a place dubbed 'The Meeting of the Wate ...

at Newburn. On 27 May 1641 he was summoned before the Committee of Estates

The Committee of Estates governed Scotland during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1638–1651) when the Parliament of Scotland was not sitting. It was dominated by Covenanters of which the most influential faction was that of the Earl of Argyll.Da ...

and charged with intrigues against Argyll, and on 11 June he was imprisoned by them in Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age, although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. ...

. Charles visited Scotland to give his formal assent to the abolition of Episcopacy, and upon the King's return to England, Montrose shared in the amnesty tacitly accorded to all Charles's partisans.

Scotland in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The king signed a warrant for his

The king signed a warrant for his Marquess

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman wi ...

ate and appointed Montrose Lord Lieutenant

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibility ...

of Scotland, both in 1644. A year later in 1645, the king commissioned him captain general. His military campaigns were fought quickly and used the element of surprise to overcome his opponents even when sometimes dauntingly outnumbered. At one point, Montrose dressed himself as the groom

A bridegroom (often shortened to groom) is a man who is about to be married or who is newlywed.

When marrying, the bridegroom's future spouse (if female) is usually referred to as the bride. A bridegroom is typically attended by a best man an ...

of the Earl of Leven

Earl of Leven (pronounced "''Lee''-ven") is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1641 for Alexander Leslie. He was succeeded by his grandson Alexander, who was in turn followed by his daughters Margaret and Catherine (who are usu ...

and travelled away from Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

, and the eventual capture of his party, in disguise with "two followers, four sorry horses, little money and no baggage".

Highlanders had never before been known to combine, but Montrose knew that many of the West Highland clans, who were largely Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, detested Argyll and his Campbell Campbell may refer to:

People Surname

* Campbell (surname), includes a list of people with surname Campbell

Given name

* Campbell Brown (footballer), an Australian rules footballer

* Campbell Brown (journalist) (born 1968), American television ne ...

clansmen, and none more so than the MacDonalds who with many of the other clans rallied to his summons. The Royalist allied Irish Confederates sent 2000 disciplined Irish soldiers led by Alasdair MacColla

Alasdair Mac Colla Chiotaich MacDhòmhnaill (c. 1610 – 13 November 1647), also known by the English variant of his name Sir Alexander MacDonald, was a military officer best known for his participation in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, notably ...

across the sea to assist him. The Irish proved to be formidable fighters.

In two campaigns, distinguished by rapidity of movement, he met and defeated his opponents in six battles. At Tippermuir

Tibbermore is a small village situated about west of Perth, Scotland. Its parish extends to Aberuthven; however, the church building is now only used occasionally for weddings and funerals.

Previously known as Tippermuir, it was the site of ...

and Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

he routed Covenanting levies; at Inverlochy he crushed the Campbells, at Auldearn

Auldearn ( gd, Allt Èireann) is a village situated east of the River Nairn, just outside Nairn in the Highland council area of Scotland. It takes its name from William the Lyon's castle of Eren (''Old Eren''), built there in the 12th century.

...

, Alford and Kilsyth

Kilsyth (; Scottish Gaelic ''Cill Saidhe'') is a town and civil parish in North Lanarkshire, roughly halfway between Glasgow and Stirling in Scotland. The estimated population is 9,860. The town is famous for the Battle of Kilsyth and the relig ...

his victories were obtained over well-led and disciplined armies.

The fiery enthusiasm of the Gordons and other clans often carried the day, but Montrose relied more upon the disciplined infantry from Ireland. His strategy at Inverlochy, and his tactics at Aberdeen, Auldearn and Kilsyth furnished models of the military art, but above all his daring and constancy marked him out as one of the greatest soldiers of the war. His career of victory was crowned by the great Battle of Kilsyth

The Battle of Kilsyth, fought on 15 August 1645 near Kilsyth, was an engagement of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The largest battle of the conflict in Scotland, it resulted in victory for the Royalist general Montrose over the forces of ...

on 15 August 1645.

Now Montrose found himself apparently master of Scotland. After Kilsyth, the king's secretary arrived with letters from Charles documenting that Montrose was lieutenant and captain general. He first conferred knighthood on Alasdair. Then he summoned a parliament to meet at

Now Montrose found himself apparently master of Scotland. After Kilsyth, the king's secretary arrived with letters from Charles documenting that Montrose was lieutenant and captain general. He first conferred knighthood on Alasdair. Then he summoned a parliament to meet at Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

on 20 October, in which he no doubt hoped to reconcile loyal obedience to the King with the establishment of a non-political Presbyterian clergy. That parliament never met. Charles had been defeated at the Battle of Naseby on 14 June 1645, and Montrose had to come to his aid if there was to be still a king to proclaim. David Leslie, one of the best Scottish generals, was promptly dispatched against Montrose to anticipate the invasion. On 12 September he came upon Montrose, who had been deserted by his Highlanders and was guarded only by a little group of followers, at Philiphaugh

Philiphaugh is a village by the Yarrow Water, on the outskirts of Selkirk, in the Scottish Borders.

Places nearby include Bowhill, Broadmeadows, the Ettrick Water, Ettrickbridge, Lindean, Salenside, Yarrowford and the Yair Forest.

Origina ...

. He won an easy victory. Montrose cut his way through to the Highlands; but he failed to organise an army. In September 1646 he embarked for Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

. Stories of his victories as documented in Latin by George Wishart reached the continent and he was offered an appointment as lieutenant-general in the French army, and the Emperor Ferdinand III awarded him the rank of field marshal, but Montrose remained devoted to the service of King Charles and so his son, Charles II.

Montrose was to appear once more on the stage of Scottish history. In June 1649, eager to avenge the death of the King, he was restored by the exiled Charles II to the now nominal lieutenancy of Scotland. Charles, however, did not scruple soon afterwards to disavow his noblest supporter to become King on terms dictated by Argyll and his adherents. In March 1650 Montrose landed in

Montrose was to appear once more on the stage of Scottish history. In June 1649, eager to avenge the death of the King, he was restored by the exiled Charles II to the now nominal lieutenancy of Scotland. Charles, however, did not scruple soon afterwards to disavow his noblest supporter to become King on terms dictated by Argyll and his adherents. In March 1650 Montrose landed in Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

to take command of a small force which he had sent on before him with George Hay, 3rd Earl of Kinnoull

George Hay, 3rd Earl of Kinnoull (died 1650) was a Scottish peer and military officer. He was an active supporter of King Charles I during the English Civil War.

Biography

He was the eldest son of George Hay, 2nd Earl of Kinnoull and Ann Doug ...

. Crossing to the mainland, he tried in vain to raise the clans, and on 27 April was surprised and routed at the Battle of Carbisdale

The Battle of Carbisdale (also known as Invercarron) took place close to the village of Culrain, Sutherland, Scotland on 27 April 1650 and was part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It was fought by the Royalist leader James Graham, 1st Marq ...

in Ross-shire

Ross-shire (; gd, Siorrachd Rois) is a historic county in the Scottish Highlands. The county borders Sutherland to the north and Inverness-shire to the south, as well as having a complex border with Cromartyshire – a county consisting of ...

. His forces were defeated in battle but he escaped. After wandering for some time he was surrendered by Neil MacLeod of Assynt at Ardvreck Castle, to whose protection, in ignorance of MacLeod's political enmity, he had entrusted himself. He was brought a prisoner to Edinburgh, and on 20 May sentenced to death by the parliament. He was hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging in ...

on the 21st, with Wishart's laudatory biography of him around his neck. He protested to the last that he was in truth a Covenanter and a loyal subject.

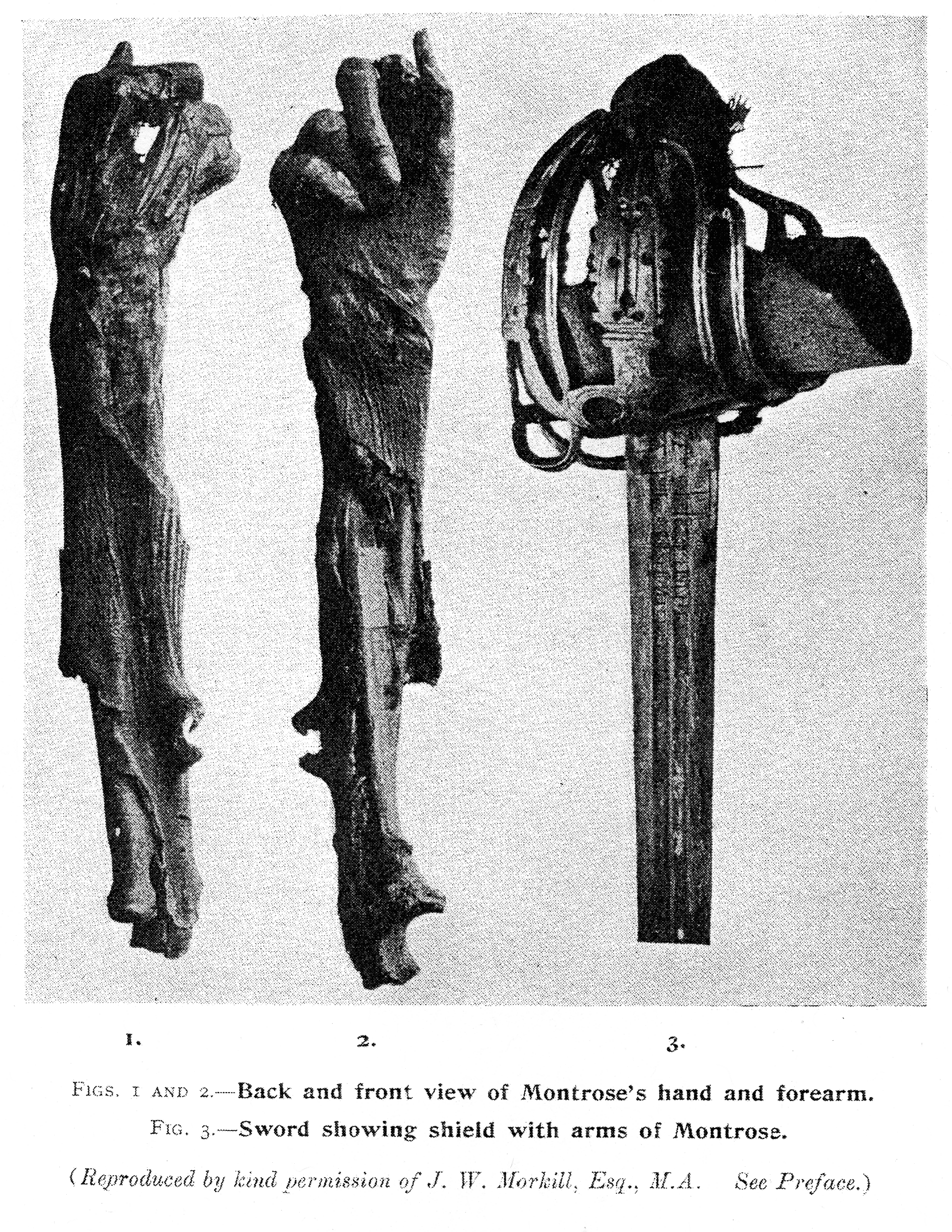

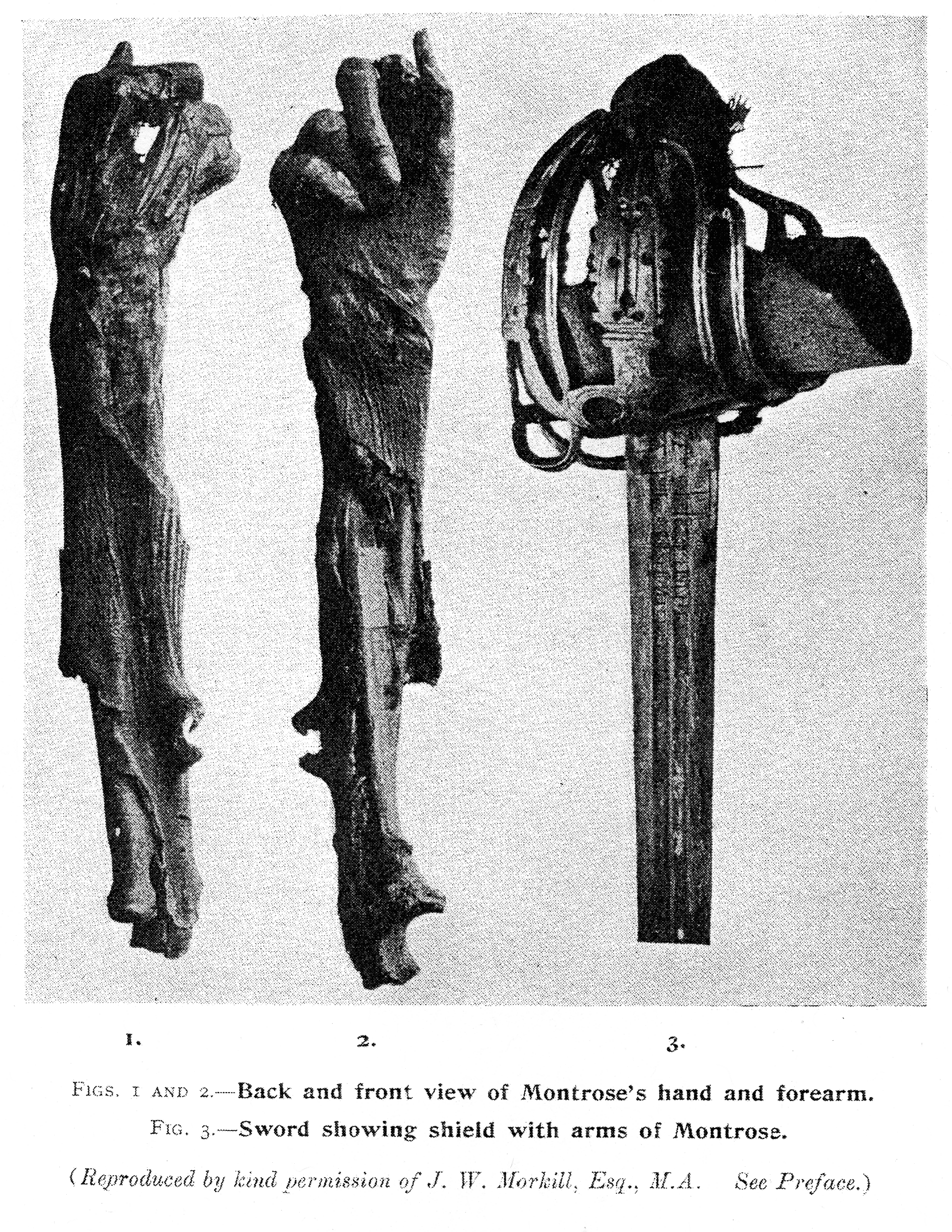

His head was removed and stood on the "prick on the highest stone" of the Old Tolbooth

The Old Tolbooth was an important municipal building in the city of Edinburgh, Scotland for more than 400 years. The medieval structure, which was located at the northwest corner of St Giles' Cathedral and was attached to the west end of the Lu ...

outside St Giles' Cathedral from 1650 until the beginning of 1661.

Shortly after Montrose's death the Scottish Argyll Government switched sides to support Charles II's attempt to regain the English throne, providing he was willing to impose the Solemn League and Covenant

The Solemn League and Covenant was an agreement between the Scottish Covenanters and the leaders of the English Parliamentarians in 1643 during the First English Civil War, a theatre of conflict in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. On 17 August 1 ...

in England for a trial period at least. After the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

Montrose was officially rehabilitated in the public memory.

On 7 January 1661 Montrose's mangled torso was disinterred from the gallows ground on the Burgh Muir and carried under a velvet canopy to the Tolbooth, where his head was reverently removed from the spike, before the procession continued on its way to Holyrood Abbey

Holyrood Abbey is a ruined abbey of the Canons Regular in Edinburgh, Scotland. The abbey was founded in 1128 by David I of Scotland. During the 15th century, the abbey guesthouse was developed into a royal residence, and after the Scottish Ref ...

. The diarist John Nicoll wrote the following eyewitness account of the event,

guard of honour of four captains with their companies, all of them inthair armes and displayit colouris, quha eftir a lang space marching up an doun the streitis, went out thaireftir to the Burrow mure quhair his corps wer bureyit, and quhair sundry nobles and gentrie his freindis and favorites, both hors and fute wer thair attending; and thair, in presence of sundry nobles, earls, lordis, barones and otheris convenit for the tyme, his graifMontrose's limbs were brought from the towns to which they had been sent (Glasgow, Perth, Stirling and Aberdeen) and placed in his coffin, as he lay in state at Holyrood. A splendid funeral was held in the church ofrave A rave (from the verb: '' to rave'') is a dance party at a warehouse, club, or other public or private venue, typically featuring performances by DJs playing electronic dance music. The style is most associated with the early 1990s dance mus ...was raisit, his body and bones taken out and wrappit up in curious clothes and put in a coffin, quhilk, under a canopy of rich velwet, wer careyit from the Burrow-mure to the Toun of Edinburgh; the nobles barones and gentrie on hors, the Toun of Edinburgh and many thousandis besyde, convoyit these corpis all along, the callouris oloursfleying, drums towkingeating Eating (also known as consuming) is the ingestion of food, typically to provide a heterotrophic organism with energy and to allow for growth. Animals and other heterotrophs must eat in order to survive — carnivores eat other animals, herbi ...trumpettis sounding, muskets cracking and cannones from the Castell roring; all of thame walking on till thai come to the Tolbuith of Edinburgh, frae the quhilke his heid wes very honorablie and with all dew respectis taken doun and put within the coffin under the cannopie with great acclamation and joy; all this tyme the trumpettis, the drumes, cannouns, gunes, the displayit cullouris geving honor to these deid corps. From thence all of thame, both hors and fute, convoyit these deid corps to the Abay Kirk of Halyrudhous quhair he is left inclosit in ane yllisle An isle is an island, land surrounded by water. The term is very common in British English. However, there is no clear agreement on what makes an island an isle or its difference, so they are considered synonyms. Isle may refer to: Geography * Is ...till forder ordour be by his Majestie and Estaites of Parliament for the solempnitie of his Buriall.

St. Giles

Saint Giles (, la, Aegidius, french: Gilles), also known as Giles the Hermit, was a hermit or monk active in the lower Rhône most likely in the 6th century. Revered as a saint, his cult became widely diffused but his hagiography is mostly lege ...

on 11 May 1661.

The torso of an executed person would have normally been given to friends or family; but Montrose was the subject of an excommunication, which was why it was originally buried in unconsecrated ground. In 1650 his niece, Lady Napier, had sent men by night to remove his heart. This relic she placed in a steel case made from his sword and placed the whole in a gold filigree box, which had been presented to her family by a Doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice ( ; vec, Doxe de Venexia ; it, Doge di Venezia ; all derived from Latin ', "military leader"), sometimes translated as Duke (compare the Italian '), was the chief magistrate and leader of the Republic of Venice between 726 a ...

. The heart in its case was retained by the Napier family for several generations until lost amidst the confusion of the French Revolution.

Battle history

Montrose had successive victories at theBattle of Tippermuir

The Battle of Tippermuir (also known as the Battle of Tibbermuir) (1 September 1644) was the first battle James Graham, 1st Marquis of Montrose, fought for King Charles I in the Scottish theatre of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. During t ...

, with the support of Alasdair MacColla and his Irish soldiers, the Battle of Aberdeen, the Battle of Inverlochy, the Battle of Auldearn

The Battle of Auldearn was an engagement of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It took place on 9 May 1645, in and around the village of Auldearn in Nairnshire. It resulted in a victory for the royalists, led by the Marquess of Montrose and Ala ...

, the Battle of Alford, and the Battle of Kilsyth

The Battle of Kilsyth, fought on 15 August 1645 near Kilsyth, was an engagement of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The largest battle of the conflict in Scotland, it resulted in victory for the Royalist general Montrose over the forces of ...

. After several years of continuous victories, Montrose was finally defeated at the Battle of Philiphaugh on 13 September 1645 by the Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

army of David, Lord Newark, restoring the power of the Committee of Estates

The Committee of Estates governed Scotland during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1638–1651) when the Parliament of Scotland was not sitting. It was dominated by Covenanters of which the most influential faction was that of the Earl of Argyll.Da ...

.

In 1646 Montrose laid siege to the

In 1646 Montrose laid siege to the Castle Chanonry of Ross

Castle Chanonry of Ross, also known as Seaforth Castle, was located in the town of Fortrose, to the north-east of Inverness, on the peninsula known as the Black Isle, Highland, Scotland. Nothing now remains of the castle. The castle was also known ...

which was held by the Clan Mackenzie and took it from them after a siege of four days. In March 1650 he captured Dunbeath Castle of the Clan Sinclair

Clan Sinclair ( gd, Clann na Ceàrda ) is a Highland Scottish clan which holds the lands of Caithness, the Orkney Islands, and the Lothians. The chiefs of the clan were the Barons of Roslin and later the Earls of Orkney and Earls of Caithness. Th ...

, who would later support him at Carbisdale. Montrose was defeated at the Battle of Carbisdale

The Battle of Carbisdale (also known as Invercarron) took place close to the village of Culrain, Sutherland, Scotland on 27 April 1650 and was part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It was fought by the Royalist leader James Graham, 1st Marq ...

by the Munros, Rosses, Sutherlands and Colonel Archibald Strachan

Archibald Strachan (died 1652) was a Scottish soldier who fought in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, reaching the rank of colonel.

Early in the English Civil War Strachan served in the English Army under Sir William Waller taking part in a number o ...

.

In literature

In fiction

* ''A Legend of Montrose

''A Legend of Montrose'' is an historical novel by Sir Walter Scott, set in Scotland in the 1640s during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It forms, along with ''The Bride of Lammermoor'', the 3rd series of Scott's ''Tales of My Landlord''. The tw ...

'' (1819) by Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy' ...

*''John Splendid'' (1898) by Neil Munro

*''Witch Wood

''Witch Wood'' is a 1927 novel by the Scottish author John Buchan that critics have called his masterpiece. The book is set in the Scottish Borders during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and combines the author's interests in landscape, 17th ...

'' by John Buchan

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (; 26 August 1875 – 11 February 1940) was a Scottish novelist, historian, and Unionist politician who served as Governor General of Canada, the 15th since Canadian Confederation.

After a brief legal career ...

(1927)

*''And No Quarter

''And No Quarter'' is an historical novel written by Irish author Maurice Walsh, first published in 1937. The background is the 1644–1645 campaigns in Scotland, led by the Royalist general Montrose, which formed part of the wider 1639–1651 W ...

'' by Maurice Walsh

Maurice Walsh (2 May 1879 – 18 February 1964) was an Irish novelist, now best known for his short story "The Quiet Man", later made into the Oscar-winning film ''The Quiet Man'', directed by John Ford and starring John Wayne and Maureen O'Ha ...

(1937)

*''The Bride'' (1939) and ''The Proud Servant'' (1949) by Margaret Irwin

*'' The Young Montrose (1972)'' and ''Montrose:The Captain-General'' (1973) by Nigel Tranter

*''Graham came by Cleish'' (1973) by James L. Dow

James Leslie Dow (5 March 1908 – 1977) was a Church of Scotland minister, broadcaster and author.

Born at Paisley and educated at Glasgow University (Trinity College), Dow was ordained in 1932 and spent several years as a chaplain in Assam, ...

*''Lady Magdalen'' (2003) by Robin Jenkins

John Robin Jenkins (11 September 1912 – 24 February 2005) was a Scottish writer of thirty published novels, the most celebrated being '' The Cone Gatherers''. He also published two collections of short stories.

Career

Robin Jenkins was bo ...

. Focuses primarily on Magdalen, Montrose's wife.

In poetry

In his 1751 poetry collection ''Ais-Eiridh na Sean Chánoin Albannaich'' ("The Resurrection of the Old Scottish Language"), which was the first published secular book in the history of Scottish Gaelic literature, the Jacobite war poet and military officer Alasdair Mac Mhaighstir Alasdair both translated intoGaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

and versified several famous statements made by Montrose expressing his loyalty to the House of Stuart during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

.Digitised version of Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair'Ais-Eiridh na Sean Chánoin Albannaich / The resurrection of the ancient Scottish language

1751 at the

National Library of Scotland

The National Library of Scotland (NLS) ( gd, Leabharlann Nàiseanta na h-Alba, sco, Naitional Leebrar o Scotland) is the legal deposit library of Scotland and is one of the country's National Collections. As one of the largest libraries in the ...

. The translations and versifications of Montrose are on pages 166-169.

References

Bibliography

* * ''Montrose'' (1952) by CV Wedgwood * ''Montrose: The King's Champion'' (1977) byMax Hastings

Sir Max Hugh Macdonald Hastings (; born 28 December 1945) is a British journalist and military historian, who has worked as a foreign correspondent for the BBC, editor-in-chief of ''The Daily Telegraph'', and editor of the ''Evening Standard' ...

Authorities for Montrose's career include George Wishart's Res gestae

', etc. (Amsterdam, 1647), published in English as ''Memoirs of the Most Renowned James Graham, Marquis of Montrose'';

Patrick Gordon

Patrick Leopold Gordon of Auchleuchries (31 March 1635 – 29 November 1699) was a general and rear admiral in Russia, of Scottish origin. He was descended from a family of Aberdeenshire, holders of the estate of Auchleuchries, near Ellon. The ...

's ''Short Abridgment of Britanes Distemper'' (Spalding Club); and the comprehensive works of Napier Napier may refer to:

People

* Napier (surname), including a list of people with that name

* Napier baronets, five baronetcies and lists of the title holders

Given name

* Napier Shaw (1854–1945), British meteorologist

* Napier Waller (1893–19 ...

. These include Montrose and Covenanters

'; his

Memorials of Montrose

' is abundantly documented, containing Montrose's poetry, including the celebrated lyric "My dear and only love.

External links

1st Marquis of Montrose Society

* ttp://www.lyrics85.com/STEELEYE-SPAN-MONTROSE-LYRICS/116787/ Lyrics to "Montrose" by Steeleye Span

Discussion thread at the Mudcat Cafe

– a website for folk musicians (

Mudcat Café

The Mudcat Café is an online discussion group and song and tune database, which also includes many other features relating to folk music.

History

The website was founded by Max Spiegel as a Blues-oriented discussion site. It was named after a ...

) – about the Battlefield Band song

Mudcat Cafe thread about the Steeleye Span song about Montrose

(scroll down 2/3 for lyrics)

Civil War re-enactors

– includes regiments associated with Montrose such as Manus O'Cahan's Regiment. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Montrose, James Graham, 1st Marquess of Scottish generals Scottish politicians 17th-century Scottish writers 17th-century Scottish peers Covenanters Alumni of the University of St Andrews Knights of the Garter 1612 births 1650 deaths 17th-century executions by Scotland People from Angus, Scotland Executed Scottish people Scottish poets People executed by the Kingdom of Scotland by hanging Members of the Parliament of Scotland 1639–1641 Marquesses of Montrose Burials at the kirkyard of St Giles Field marshals of the Holy Roman Empire