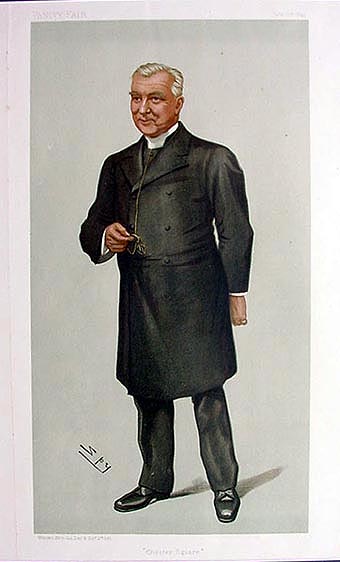

James Fleming (priest) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Fleming (1830–1908) was an Irish clergyman of the

James Fleming (1830–1908) was an Irish clergyman of the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, public speaker and fund-raiser. A canon of York Minster

The Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter in York, commonly known as York Minster, is the cathedral of York, North Yorkshire, England, and is one of the largest of its kind in Northern Europe. The minster is the seat of the Archbis ...

, he became chaplain in ordinary

''In ordinary'' is an English phrase with multiple meanings. In relation to the Royal Household, it indicates that a position is a permanent one. In naval matters, vessels "in ordinary" (from the 17th century) are those out of service for repair o ...

to Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

and Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

, and was a close friend of the British royal family.

Early life

Born atCarlow

Carlow ( ; ) is the county town of County Carlow, in the south-east of Ireland, from Dublin. At the 2016 census, it had a combined urban and rural population of 24,272.

The River Barrow flows through the town and forms the historic bounda ...

on 26 July 1830, he was from a Scots-Irish background, the youngest of five children of Patrick Fleming, M.D., of Strabane

Strabane ( ; ) is a town in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland.

Strabane had a population of 13,172 at the 2011 Census. It lies on the east bank of the River Foyle. It is roughly midway from Omagh, Derry and Letterkenny. The River Foyle marks ...

, who had married in 1820 Mary, daughter of Captain Francis Kirkpatrick. From 1833 to 1836 he was in Jamaica, his father having become paymaster to the 56th Regiment; and on his father's death in 1838 his mother, who survived to September 1876, moved to Bath, Somerset

Bath () is a city in the Bath and North East Somerset unitary area in the county of Somerset, England, known for and named after its Roman-built baths. At the 2021 Census, the population was 101,557. Bath is in the valley of the River Avon, ...

. His two brothers, William and Francis, were sent to Sandhurst, but ultimately took orders; William, a traditional Protestant, died vicar of Christ Church, Chislehurst, in May 1900.

Fleming went to King Edward VI's Grammar School, Bath, in 1840, and to Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13 –18) in Shrewsbury.

Founded in 1552 by Edward VI by Royal Charter, it was originally a boarding school for boys; girls have been admitted into the ...

in 1846, under Benjamin Hall Kennedy

Benjamin Hall Kennedy (6 November 1804 – 6 April 1889) was an English scholar and schoolmaster, known for his work in the teaching of the Latin language. He was an active supporter of Newnham College and Girton College as Cambridge University ...

. He was in the school cricket team, and won the Millington scholarship, matriculating on 15 November 1849 at Magdalene College, Cambridge

Magdalene College ( ) is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1428 as a Benedictine hostel, in time coming to be known as Buckingham College, before being refounded in 1542 as the College of St Mary ...

. He graduated B.A. there in 1853, proceeding M.A. in 1857 and B.D. in 1864.

Priest and canon

Ordained deacon in 1853 and priest in 1854, he was curate, first, of St. Stephen,Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

(1853–5), and then of St. Stephen, Lansdown, in the parish of Walcot, Bath

Walcot is a suburb of the city of Bath, England. It lies to the north-north-east of the city centre, and is an electoral ward of the city.

Fleming started classes of instruction in

elocution

Elocution is the study of formal speaking in pronunciation, grammar, style, and tone as well as the idea and practice of effective speech and its forms. It stems from the idea that while communication is symbolic, sounds are final and compelli ...

for working people in 1859, and was an advocate of total abstinence

Teetotalism is the practice or promotion of total personal abstinence from the psychoactive drug alcohol, specifically in alcoholic drinks. A person who practices (and possibly advocates) teetotalism is called a teetotaler or teetotaller, or i ...

. In 1866 he was appointed by trustees to the incumbency of Camden church, Camberwell, formerly held by Henry Melvill

Rev. Henry Melvill (14 September 1798 – 9 February 1871) was a British priest in the Church of England, and principal of the East India Company College from 1844 to 1858. He afterwards served as Canon of St Paul's Cathedral.

Early years

Mel ...

, and in 1873 was presented by the Hugh Grosvenor, 3rd Marquess of Westminster

Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster, (13 October 1825 – 22 December 1899), styled Viscount Belgrave between 1831 and 1845, Earl Grosvenor between 1845 and 1869, and known as The Marquess of Westminster between 1869 and 1874, was an ...

to the vicarage of St. Michael's Church, Chester Square

The Church of St Michael is a Church of England parish church on Chester Square in the Belgravia district of West London. It has been listed Grade II on the National Heritage List for England since February 1958.

Design

It was built in 1844 at t ...

. Admitted on 19 February 1874, he retained this living for the rest of his life, becoming chaplain to Grosvenor, by then Duke of Westminster, in 1875. During the period parochial schools and local churches increased and a convalescent home built at Birchington

Birchington-on-Sea is a village in the Thanet district in Kent, England, with a population of 9,961.

The village forms part of the civil parish of Birchington. It lies on the coast facing the North Sea, east of the Thames Estuary, between the ...

, for which a parishioner gave Fleming £23,500l. Outside his parish his main interests were Dr. Barnardo's Homes, the Religious Tract Society

The Religious Tract Society was a British evangelical Christian organization founded in 1799 and known for publishing a variety of popular religious and quasi-religious texts in the 19th century. The society engaged in charity as well as commerci ...

, of which he was an honorary secretary from 1880; and the Hospital Sunday Fund, to which his congregation made annual contributions.

On 30 May 1879 Lord Beaconsfield

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a centr ...

nominated Fleming to a residentiary canonry in York Minster. Archbishop William Thomson made him succentor there on 20 August 1881, and precentor with a prebendal stall on 3 January 1883.

Later life

In 1880 Beaconsfield wanted to appoint Fleming firstBishop of Liverpool

The Bishop of Liverpool is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Liverpool in the Province of York.''Crockford's Clerical Directory'', 100th edition, (2007), Church House Publishing. .

The diocese stretches from Southport in the no ...

, but local pressure caused John Charles Ryle

John Charles Ryle (10 May 1816 – 10 June 1900) was an English evangelical Anglican bishop. He was the first Anglican bishop of Liverpool.

Life

He was the eldest son of John Ryle, private banker, of Park House, Macclesfield, M.P. for Maccles ...

to be preferred. He later declined the Bishopric of Sydney

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

, in November 1884, and for financial reasons Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

's successive offers of the deaneries of Chester (20 December 1885) and of Norwich (6 May 1889).

Honorary chaplain to Queen Victoria (1876) and chaplain in ordinary to her (1880) and to Edward VII (1901), Fleming from 1879 preached almost yearly before the Queen and Prince of Wales, at Sandringham Sandringham can refer to:

Places

* Sandringham, New South Wales, Australia

* Sandringham, Queensland, Australia

* Sandringham, Victoria, Australia

**Sandringham railway line

**Sandringham railway station

**Electoral district of Sandringham

* Sand ...

. From 1880 Fleming was Whitehead professor of preaching and elocution at the London College of Divinity

St John's College, Nottingham, founded as the London College of Divinity, was an Anglican and interdenominational theological college situated in Bramcote, Nottingham, England. The college stood in the open evangelical tradition and stated that i ...

(St. John's Hall, Highbury). With Thomas Pownall Boultbee

Thomas Pownall Boultbee, LL.D. (1818–1884), was an English clergyman.

Life

Boultbee, the eldest son of Thomas Boultbee, for forty-seven years Vicar of Bidford, Warwickshire, was born on 7 Aug. 1818. He was also the nephew of John Boultbee the a ...

of the College, and William Barlow, he advised Ann Dudin Brown

Ann Dudin Brown (1822–1917) was a benefactor. She funded the establishment of Westfield College for women.

Life

Brown was born to John Dudin Brown and his wife, Ann, on the 2nd January 1822. Her father was a wharfinger on the River Thames and a ...

, benefactor of Westfield College

Westfield College was a small college situated in Hampstead, London, from 1882 to 1989. It was the first college to aim to educate women for University of London degrees from its opening. The college originally admitted only women as students and ...

. Three times — 1901, 1903, and 1907— he was appointed William Jones lecturer (sometimes called the Golden lectureship) by the Haberdashers' Company

The Worshipful Company of Haberdashers, one of the Great Twelve City Livery Companies, is an ancient merchant guild of London, England associated with the silk and velvet trades.

History and functions

The Haberdashers' Company follows the M ...

.

Fleming, who early in 1877 denounced the "folly, obstinacy, and contumacy" of the ritualists in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' (25 January 1877), ceased to wear the black gown in the pulpit after the judgment in Clifton v. Ridsdale (12 May 1877). His suspicion of ritualism only increased with his years. In later life he supported the Protestant agitation of John Kensit

John Kensit (12 February 1853 – 8 October 1902) was an English religious leader and polemicist. He concentrated on a struggle against Anglo-Catholic tendencies in the Church of England.

Life history

Kensit, a bookseller from London, had in his ...

. His personal relations with C. H. Spurgeon

Charles Haddon Spurgeon (19 June 1834 – 31 January 1892) was an English Particular Baptist preacher.

Spurgeon remains highly influential among Christians of various denominations, among whom he is known as the "Prince of Preachers". He wa ...

, William Morley Punshon and other nonconformist leaders were good.

Fleming died at St. Michael's Vicarage on 1 September 1908, and was buried at Kensal Green cemetery. Ernest Harold Pearce

Ernest Harold Pearce (23 July 1865 – 28 October 1930) was an Anglican bishop, the 106th bishop of Worcester from 1919 until his death.

Biography

He was born on 23 July 1865 and was educated at Christ's Hospital and Peterhouse, Cambridge. Ordain ...

in the ''Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' wrote that "personal charm and grace of speech made him popular, but he was neither a student nor a thinker". A reredos

A reredos ( , , ) is a large altarpiece, a screen, or decoration placed behind the altar in a church. It often includes religious images.

The term ''reredos'' may also be used for similar structures, if elaborate, in secular architecture, for ex ...

and choir stalls in memory of him were placed in St. Michael's (1911), and a statue of King Edwyn in York Minster.

Works

Fleming's ''Bath Penny Readings'' of 1862 covers one of the origins of thepenny reading

The penny reading was a form of popular public entertainment that arose in the United Kingdom in the middle of the 19th century, consisting of readings and other performances, for which the admission charged was one penny.

Impact

Under the headin ...

movement. He published a manual on ''The Art of Reading and Speaking'' (1896), ''Our Gracious Queen Alexandra'' (1901) for the Religious Tract Society, and sermons. Fleming explained in an open letter that he had transferred a sermon by Thomas De Witt Talmage

Thomas De Witt Talmage (January 7, 1832April 12, 1902) was a preacher, clergyman and divine in the United States who held pastorates in the Reformed Church in America and Presbyterian Church. He was one of the most prominent religious leaders ...

from a common-place book to ''Science and the Bible'' (1880) inadvertently, in reply to an 1887 pamphlet accusing him of plagiarism from Talmage's ''Fifty Sermons''.

On 24 January 1892 Fleming preached at Sandringham the sermon in memory of the Duke of Clarence

Duke of Clarence is a substantive title which has been traditionally awarded to junior members of the British Royal Family. All three creations were in the Peerage of England.

The title was first granted to Lionel of Antwerp, the second son ...

. It was published as ''Recognition in Eternity'', and had a steady sale, reaching in 1911 about 67,000 copies. The author's profits were distributed between charities named by Queen Alexandra

Alexandra of Denmark (Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia; 1 December 1844 – 20 November 1925) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 22 January 1901 to 6 May 1910 as the wife of King ...

: the Gordon Boys' Home and the British Home and Hospital for Incurables.

Fleming made a number of sound recordings for the Gramophone & Typewriter Ltd

The Gramophone Company Limited (The Gramophone Co. Ltd.), based in the United Kingdom and founded by Emil Berliner, was one of the early record company, recording companies, the parent organisation for the ''His Master's Voice (HMV)'' label, a ...

(later HMV

Sunrise Records and Entertainment, trading as HMV (for His Master's Voice), is a British music and entertainment retailer, currently operating exclusively in the United Kingdom.

The first HMV-branded store was opened by the Gramophone Company ...

, then part of EMI

EMI Group Limited (originally an initialism for Electric and Musical Industries, also referred to as EMI Records Ltd. or simply EMI) was a British transnational conglomerate founded in March 1931 in London. At the time of its break-up in 201 ...

), of readings from literary works by Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

, Leigh Hunt

James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 178428 August 1859), best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist and poet.

Hunt co-founded '' The Examiner'', a leading intellectual journal expounding radical principles. He was the centr ...

and Thomas Hood

Thomas Hood (23 May 1799 – 3 May 1845) was an English poet, author and humorist, best known for poems such as " The Bridge of Sighs" and "The Song of the Shirt". Hood wrote regularly for ''The London Magazine'', ''Athenaeum'', and ''Punch''. ...

, ''The Charge of the Light Brigade'' by Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his ...

, etc. His rendering of Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wide ...

's ''The Bells'', where the first three verses occupied one 10-inch single-sided disc, and verse 4 took the whole of a second disc, exhibits throughout his fine control of spoken and extended pitch. The phonetician Daniel Jones employed the first of the 'Bells' discs as one of his illustrations of 'intonation curves'.Jones, D. (1909), Intonation curves: a collection of phonetic texts, in which intonation is marked throughout by means of curved lines on a musical stave, Leipzig and Berlin, Teubner. Available online at: https://archive.org/details/intonationcurves00jonerich/mode/2up He also recorded part of the Gramophone album of discs in 1908 giving a service for the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

Morning Prayer, but died before completing the set (which was taken over by the Reverend Joshua Parkyn).

Family

Fleming married, on 21 June 1853, atHoly Trinity, Brompton

Holy Trinity Brompton with St Paul's, Onslow Square and St Augustine's, South Kensington, often referred to simply as HTB, is an Anglicanism, Anglican church (building), church in London, England. The church consists of six sites: HTB Brompton ...

, Grace Purcell, elder daughter of Admiral Purcell; she died on 25 May 1903. They had three sons and three daughters.

Notes

;Attribution {{DEFAULTSORT:Fleming, James 1830 births 1908 deaths 19th-century Irish Anglican priests People from Strabane