Jacobite Army (1745) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Jacobite Army, sometimes referred to as the Highland Army,Pittock, Murray (2013) ''Material Culture and Sedition, 1688-1760: Treacherous Objects, Secret Places'', p.88 was the military force assembled by

Charles left France on 15 July aboard '' Du Teillay,'' supplies and 70 volunteers from the Irish Brigade transported by ''Elizabeth,'' an elderly 64-gun warship. Four days out, they were intercepted by ''HMS Lion'' which engaged ''Elizabeth''; after a four hour battle, both were forced to return to port, while ''Du Teillay'' continued to

Charles left France on 15 July aboard '' Du Teillay,'' supplies and 70 volunteers from the Irish Brigade transported by ''Elizabeth,'' an elderly 64-gun warship. Four days out, they were intercepted by ''HMS Lion'' which engaged ''Elizabeth''; after a four hour battle, both were forced to return to port, while ''Du Teillay'' continued to  Co-operation with O'Sullivan was essential but failed to develop, Murray arguing Highland customs better suited the bulk of their recruits and it was unrealistic to expect them to execute weapons drill or carry out written orders. Others considered these views outdated, including Sir John MacDonald, an Irish exile who acted as Inspector-General of Cavalry. There was some truth in both positions; plenty of Scots served in European armies but the military aspects of clan society had been in decline for decades and most Highland levies were illiterate agricultural workers.

Even for regular troops, training was a concern as infantry drill became increasingly complex; before and after 1746, peacetime inspections consistently noted an alarmingly high number of British regiments as 'Not fit for service.' This had many causes, one of the most significant being lack of live firing practice and the Jacobites were short of both weapons and ammunition. The exiles also failed to appreciate the Highland obligation to provide military service assumed short periods of warfare, not continuous service for six months or a year. After Prestonpans and Falkirk, the clan chiefs could not prevent large numbers of their levies returning home; when Charles wanted to attack Cumberland in early February 1746, he was told the army was in no state to fight a battle.

Charles considered his 'Lieutenant-Generals' subordinates, whose duty was to comply with his orders; Murray disagreed and matters were not helped by a furious row between the two prior to Prestonpans. Lord Elcho later wrote the Scots were concerned from the beginning by Charles' autocratic style and fears he was overly influenced by his Irish advisors.

Co-operation with O'Sullivan was essential but failed to develop, Murray arguing Highland customs better suited the bulk of their recruits and it was unrealistic to expect them to execute weapons drill or carry out written orders. Others considered these views outdated, including Sir John MacDonald, an Irish exile who acted as Inspector-General of Cavalry. There was some truth in both positions; plenty of Scots served in European armies but the military aspects of clan society had been in decline for decades and most Highland levies were illiterate agricultural workers.

Even for regular troops, training was a concern as infantry drill became increasingly complex; before and after 1746, peacetime inspections consistently noted an alarmingly high number of British regiments as 'Not fit for service.' This had many causes, one of the most significant being lack of live firing practice and the Jacobites were short of both weapons and ammunition. The exiles also failed to appreciate the Highland obligation to provide military service assumed short periods of warfare, not continuous service for six months or a year. After Prestonpans and Falkirk, the clan chiefs could not prevent large numbers of their levies returning home; when Charles wanted to attack Cumberland in early February 1746, he was told the army was in no state to fight a battle.

Charles considered his 'Lieutenant-Generals' subordinates, whose duty was to comply with his orders; Murray disagreed and matters were not helped by a furious row between the two prior to Prestonpans. Lord Elcho later wrote the Scots were concerned from the beginning by Charles' autocratic style and fears he was overly influenced by his Irish advisors.

At their insistence, Charles established a "Council of War" to agree military strategy but deeply resented what he viewed as an imposition by subjects on their divinely appointed monarch. Consisting of 15-20 senior leaders, it was dominated by the Highlanders who provided most of the manpower and decisions reflected their priorities.McCann (1963) pp.107-8 The civilian equivalent or 'Privy Council' had a higher proportion of Lowland gentry, thus dividing leadership between competing power centres.

At their insistence, Charles established a "Council of War" to agree military strategy but deeply resented what he viewed as an imposition by subjects on their divinely appointed monarch. Consisting of 15-20 senior leaders, it was dominated by the Highlanders who provided most of the manpower and decisions reflected their priorities.McCann (1963) pp.107-8 The civilian equivalent or 'Privy Council' had a higher proportion of Lowland gentry, thus dividing leadership between competing power centres.

In contrast to 1715, many joined the Jacobites in 1745 for reasons other than Stuart loyalism. While 46% of the Jacobite army came from the

In contrast to 1715, many joined the Jacobites in 1745 for reasons other than Stuart loyalism. While 46% of the Jacobite army came from the

Jacobite recruiting methods in Scotland varied across the country. Adherence was fundamentally decided by personal or local factors,McCann (1963), xxi and often differed between officers and the rank and file.

Jacobite recruiting methods in Scotland varied across the country. Adherence was fundamentally decided by personal or local factors,McCann (1963), xxi and often differed between officers and the rank and file.

While

While

Many units were raised under the feudal obligation of vassalage, whereby tenants held land in return for military service. While this led authors like

Many units were raised under the feudal obligation of vassalage, whereby tenants held land in return for military service. While this led authors like

The Jacobite infantry was initially divided into two divisions, 'Highland' and 'Low Country Foot', nominally commanded by Murray and Perth, who was replaced by Charles after Carlisle. Following British army custom, they were split into

The Jacobite infantry was initially divided into two divisions, 'Highland' and 'Low Country Foot', nominally commanded by Murray and Perth, who was replaced by Charles after Carlisle. Following British army custom, they were split into

Jacobite cavalry was small in number in 1745-6 and were restricted largely to scouting and other typical light cavalry duties. Despite this, the units that were raised arguably performed better in this role during the campaign than the regulars opposing them. All except one of the 'regiments' comprised two troops and were over-officered to an even greater degree than the infantry, as commissions were used to reward Jacobite support.

Jacobite cavalry was small in number in 1745-6 and were restricted largely to scouting and other typical light cavalry duties. Despite this, the units that were raised arguably performed better in this role during the campaign than the regulars opposing them. All except one of the 'regiments' comprised two troops and were over-officered to an even greater degree than the infantry, as commissions were used to reward Jacobite support.

Traditional depictions of the Jacobite army often showed men dressed in Highland fashion and armed with

Traditional depictions of the Jacobite army often showed men dressed in Highland fashion and armed with  Despite this, Jacobite officers recognised the psychological value of the "

Despite this, Jacobite officers recognised the psychological value of the "

Charles Edward Stuart

Charles Edward Louis John Sylvester Maria Casimir Stuart (20 December 1720 – 30 January 1788) was the elder son of James Francis Edward Stuart, grandson of James II and VII, and the Stuart claimant to the thrones of England, Scotland and ...

and his Jacobite supporters during the 1745 Rising

The Jacobite rising of 1745, also known as the Forty-five Rebellion or simply the '45 ( gd, Bliadhna Theàrlaich, , ), was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took pl ...

that attempted to restore the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter fi ...

to the British throne.

Starting with less than 1,000 men at Glenfinnan

Glenfinnan ( gd, Gleann Fhionnain ) is a hamlet in Lochaber area of the Highlands of Scotland. In 1745 the Jacobite rising began here when Prince Charles Edward Stuart ("Bonnie Prince Charlie") raised his standard on the shores of Loch Shiel. S ...

in August 1745, the Jacobite army won a significant victory at Prestonpans

Prestonpans ( gd, Baile an t-Sagairt, Scots: ''The Pans'') is a small mining town, situated approximately eight miles east of Edinburgh, Scotland, in the Council area of East Lothian. The population as of is. It is near the site of the 1745 ...

in September. A force of about 5,500 then invaded England in November and reached as far south as Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby gai ...

before successfully retreating into Scotland. Reaching a peak strength of between 9,000 and 14,000, they won another victory in January 1746 at Falkirk

Falkirk ( gd, An Eaglais Bhreac, sco, Fawkirk) is a large town in the Central Lowlands of Scotland, historically within the county of Stirlingshire. It lies in the Forth Valley, northwest of Edinburgh and northeast of Glasgow.

Falkirk had a ...

, before defeat at Culloden in April. While a large number of Jacobites remained in arms, lack of external and domestic support combined with overwhelming government numbers meant they dispersed, ending the rebellion.

Once characterised as a largely Gaelic-speaking force recruited from the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Sco ...

using traditional weapons and tactics, modern historians have demonstrated this was only partially accurate. The army also included a large number of north-eastern and lowland Scots, along with substantial Franco-Irish and English contingents, who were drilled and organised in line with contemporary European military practices.

Formation and leadership

Charles left France on 15 July aboard '' Du Teillay,'' supplies and 70 volunteers from the Irish Brigade transported by ''Elizabeth,'' an elderly 64-gun warship. Four days out, they were intercepted by ''HMS Lion'' which engaged ''Elizabeth''; after a four hour battle, both were forced to return to port, while ''Du Teillay'' continued to

Charles left France on 15 July aboard '' Du Teillay,'' supplies and 70 volunteers from the Irish Brigade transported by ''Elizabeth,'' an elderly 64-gun warship. Four days out, they were intercepted by ''HMS Lion'' which engaged ''Elizabeth''; after a four hour battle, both were forced to return to port, while ''Du Teillay'' continued to Eriskay

Eriskay ( gd, Èirisgeigh), from the Old Norse for "Eric's Isle", is an island and community council area of the Outer Hebrides in northern Scotland with a population of 143, as of the 2011 census. It lies between South Uist and Barra and is ...

. This meant Charles arrived with few weapons, accompanied only by the "Seven Men of Moidart

The Seven Men of Moidart, in Jacobite folklore, were seven followers of Charles Edward Stuart who accompanied him at the start of his 1745 attempt to reclaim the thrones of Great Britain and Ireland for the House of Stuart. The group included En ...

," among them the elderly Marquess of Tullibardine

Duke of Atholl, named for Atholl in Scotland, is a title in the Peerage of Scotland held by the head of Clan Murray. It was created by Queen Anne in 1703 for John Murray, 2nd Marquess of Atholl, with a special remainder to the heir male of ...

and John O'Sullivan John O'Sullivan may refer to:

Sports

*John O'Sullivan (cricketer) (1918–1991), New Zealand cricketer

*John O'Sullivan (cyclist) (born 1933), Australian cyclist

*John O'Sullivan (footballer) (born 1993), Irish footballer for Accrington Stanley

*J ...

, an Irish-born officer in the French army.

Many of those contacted on arrival told Charles to return to France but Lochiel's commitment persuaded enough for the Rebellion to be launched at Glenfinnan

Glenfinnan ( gd, Gleann Fhionnain ) is a hamlet in Lochaber area of the Highlands of Scotland. In 1745 the Jacobite rising began here when Prince Charles Edward Stuart ("Bonnie Prince Charlie") raised his standard on the shores of Loch Shiel. S ...

on 19 August. O'Sullivan estimated initial numbers as around 1,000, with 700 Camerons plus several hundred men from Lochaber

Lochaber ( ; gd, Loch Abar) is a name applied to a part of the Scottish Highlands. Historically, it was a provincial lordship consisting of the parishes of Kilmallie and Kilmonivaig, as they were before being reduced in extent by the creation ...

led by Keppoch.Pittock, Murray. (2016) ''Culloden'', Oxford University Press, p.21

Though physically fit, they lacked discipline and were poorly armed, accentuating the loss of ''Elizabeth'' with its weapons and the regulars intended to provide the core of the Jacobite army.O'Sullivan wrote that Lochiel had "700 good men, but ill armed; Kapock eppocharrived the same day , wth about 350 clivor fellows". Narrative of O'Sullivan in Tayler (ed) (1938), ''1745 and After'', Nelson, p.60 Although Charles was in nominal command, his inexperience meant O'Sullivan acted as adjutant-general and quartermaster-general, handling personnel, training and logistics.McDonnell, Hector (1996) ''The Wild Geese of the Antrim MacDonnells'', Irish Academic Press, p.102

O'Sullivan created an army organised along conventional European lines and his use of the then-novel divisional structure is viewed as a major factor in the Jacobites' speed of movement.Reid, Stuart (2012) ''The Scottish Jacobite Army 1745–46'', Bloomsbury, pp.90-92 Further recruits came in as they marched on Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

; by the time of Prestonpans

Prestonpans ( gd, Baile an t-Sagairt, Scots: ''The Pans'') is a small mining town, situated approximately eight miles east of Edinburgh, Scotland, in the Council area of East Lothian. The population as of is. It is near the site of the 1745 ...

on 21 September, numbers had increased to around 2,500.

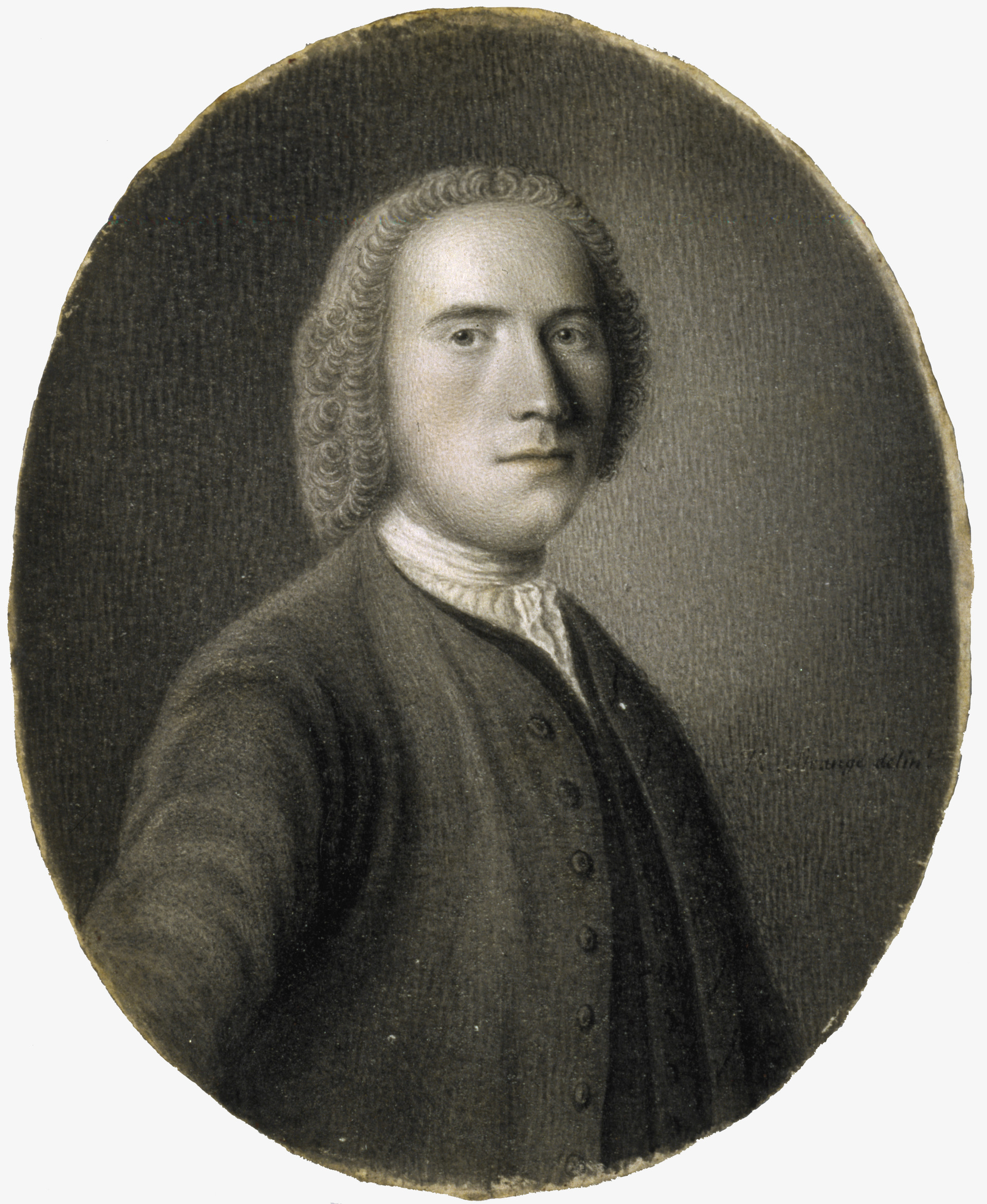

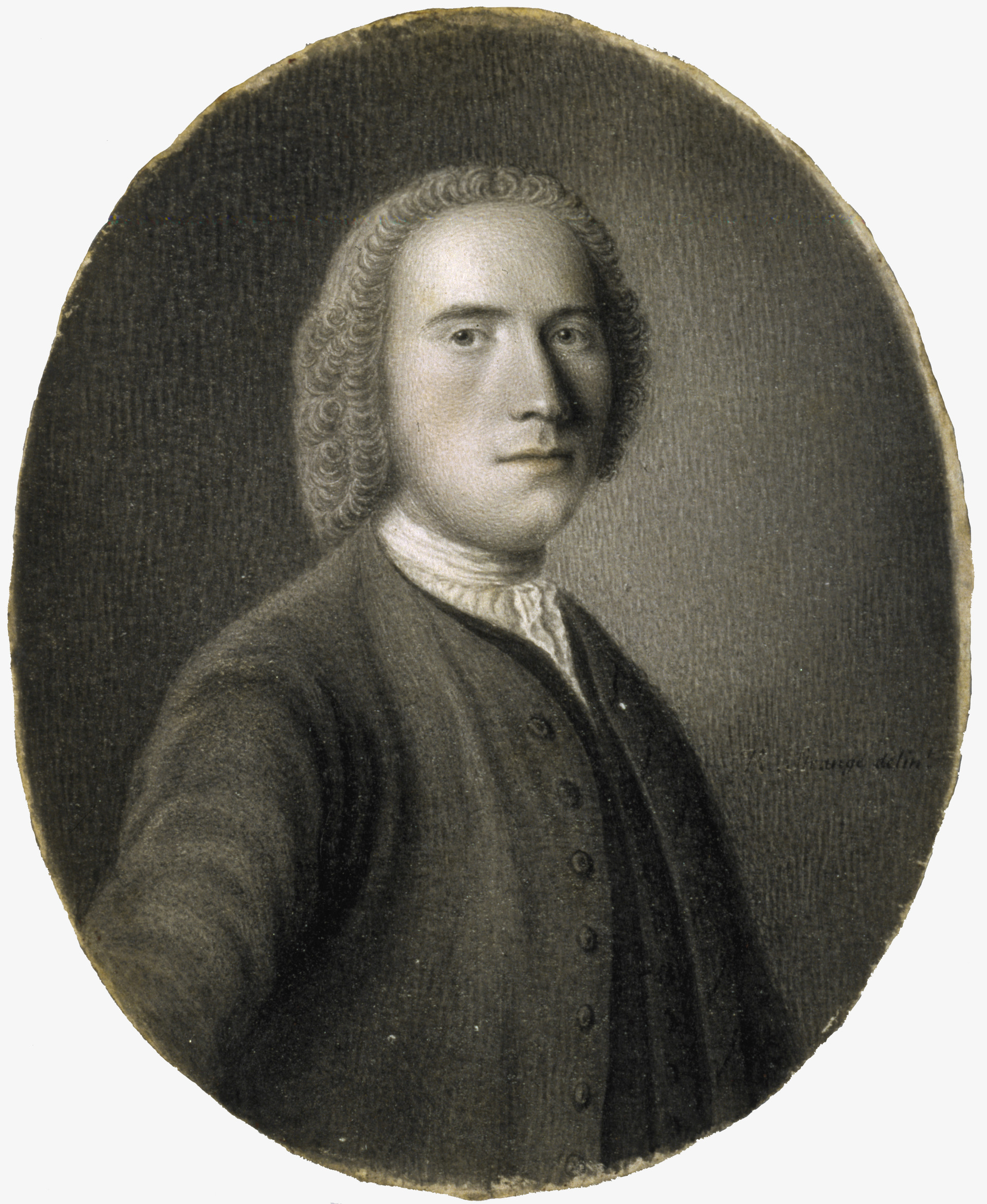

One of these recruits was Tullibardine's younger brother, Lord George Murray, who took part in the failed Risings of 1715

Events

For dates within Great Britain and the British Empire, as well as in the Russian Empire, the "old style" Julian calendar was used in 1715, and can be converted to the "new style" Gregorian calendar (adopted in the British Empire i ...

and 1719

Events

January–March

* January 8 – Carolean Death March begins: A catastrophic retreat by a largely-Finnish Swedish- Carolean army under the command of Carl Gustaf Armfeldt across the Tydal mountains in a blizzard kills around 3,7 ...

. Despite this, his acceptance of a pardon in 1725 and swearing an Oath of Allegiance to George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089)

* ...

in 1739 made some suspicious, including Charles' chief Scottish advisor, Murray of Broughton. Although primarily driven by Broughton's political ambitions, others recorded Murray's genuine military talents were undermined by a quick temper, arrogance and inability to take advice.

Co-operation with O'Sullivan was essential but failed to develop, Murray arguing Highland customs better suited the bulk of their recruits and it was unrealistic to expect them to execute weapons drill or carry out written orders. Others considered these views outdated, including Sir John MacDonald, an Irish exile who acted as Inspector-General of Cavalry. There was some truth in both positions; plenty of Scots served in European armies but the military aspects of clan society had been in decline for decades and most Highland levies were illiterate agricultural workers.

Even for regular troops, training was a concern as infantry drill became increasingly complex; before and after 1746, peacetime inspections consistently noted an alarmingly high number of British regiments as 'Not fit for service.' This had many causes, one of the most significant being lack of live firing practice and the Jacobites were short of both weapons and ammunition. The exiles also failed to appreciate the Highland obligation to provide military service assumed short periods of warfare, not continuous service for six months or a year. After Prestonpans and Falkirk, the clan chiefs could not prevent large numbers of their levies returning home; when Charles wanted to attack Cumberland in early February 1746, he was told the army was in no state to fight a battle.

Charles considered his 'Lieutenant-Generals' subordinates, whose duty was to comply with his orders; Murray disagreed and matters were not helped by a furious row between the two prior to Prestonpans. Lord Elcho later wrote the Scots were concerned from the beginning by Charles' autocratic style and fears he was overly influenced by his Irish advisors.

Co-operation with O'Sullivan was essential but failed to develop, Murray arguing Highland customs better suited the bulk of their recruits and it was unrealistic to expect them to execute weapons drill or carry out written orders. Others considered these views outdated, including Sir John MacDonald, an Irish exile who acted as Inspector-General of Cavalry. There was some truth in both positions; plenty of Scots served in European armies but the military aspects of clan society had been in decline for decades and most Highland levies were illiterate agricultural workers.

Even for regular troops, training was a concern as infantry drill became increasingly complex; before and after 1746, peacetime inspections consistently noted an alarmingly high number of British regiments as 'Not fit for service.' This had many causes, one of the most significant being lack of live firing practice and the Jacobites were short of both weapons and ammunition. The exiles also failed to appreciate the Highland obligation to provide military service assumed short periods of warfare, not continuous service for six months or a year. After Prestonpans and Falkirk, the clan chiefs could not prevent large numbers of their levies returning home; when Charles wanted to attack Cumberland in early February 1746, he was told the army was in no state to fight a battle.

Charles considered his 'Lieutenant-Generals' subordinates, whose duty was to comply with his orders; Murray disagreed and matters were not helped by a furious row between the two prior to Prestonpans. Lord Elcho later wrote the Scots were concerned from the beginning by Charles' autocratic style and fears he was overly influenced by his Irish advisors.

At their insistence, Charles established a "Council of War" to agree military strategy but deeply resented what he viewed as an imposition by subjects on their divinely appointed monarch. Consisting of 15-20 senior leaders, it was dominated by the Highlanders who provided most of the manpower and decisions reflected their priorities.McCann (1963) pp.107-8 The civilian equivalent or 'Privy Council' had a higher proportion of Lowland gentry, thus dividing leadership between competing power centres.

At their insistence, Charles established a "Council of War" to agree military strategy but deeply resented what he viewed as an imposition by subjects on their divinely appointed monarch. Consisting of 15-20 senior leaders, it was dominated by the Highlanders who provided most of the manpower and decisions reflected their priorities.McCann (1963) pp.107-8 The civilian equivalent or 'Privy Council' had a higher proportion of Lowland gentry, thus dividing leadership between competing power centres.

Viscount Strathallan {{Use dmy dates, date=November 2019

The title of Lord Maderty was created in 1609 for James Drummond, a younger son of the 2nd Lord Drummond of Cargill. The titles of Viscount Strathallan and Lord Drummond of Cromlix were created in 1686 for Willia ...

was appointed commander in Scotland and continued recruiting, while the field army of roughly 5,500 invaded England in early November.Duffy (2009), 555 Command was split between the three lieutenant-generals: Murray, Tullibardine, and James Drummond, titular Duke of Perth. In theory, the three rotated command on a daily basis, but Tullibardine's poor health and Perth's inexperience meant in practice it was exercised by Murray.Reid (2012) pp.43-45

Charles' relationship with the Scots began to deteriorate during pre-invasion discussions in Edinburgh and worsened when Murray resigned at Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

prior to being reinstated. After Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby gai ...

, the War Council met only once more, an acrimonious session at Crieff

Crieff (; gd, Craoibh, meaning "tree") is a Scottish market town in Perth and Kinross on the A85 road between Perth and Crianlarich, and the A822 between Greenloaning and Aberfeldy. The A822 joins the A823 to Dunfermline. Crieff has become ...

in February 1746. Disappointment and heavy drinking resulted in repeated accusations by Charles that the Scots were traitors, reinforced when Murray advised abandoning plans to invade England. Instead, he proposed an insurgency in the Highlands that would "...oblige the Crown to come to terms, because the war rendered it necessary...English troops be occupied elsewhere".Elcho in Tayler (ed) (1948) ''A Jacobite Miscellany: Eight Original Papers on the Rising of 1745-1746'', p.202

In late November, Perth's brother John Drummond landed in Scotland and replaced Strathallan but his arrival introduced another element of division into the Jacobite leadership. He and Charles previously clashed in France and his first act was to countermand instructions new recruits be sent into England; as an officer in the French army, he had orders not to leave Scotland until all fortresses held by British government troops had been taken. Since he brought money, weapons, siege artillery and 150 Scots and Irish regulars, he could not be ignored; at Falkirk and Culloden, O'Sullivan exercised effective command, with Murray, Perth and Drummond as brigade commanders but the different factions viewed each other with suspicion and hostility.

Recruitment

Areas of recruitment

In contrast to 1715, many joined the Jacobites in 1745 for reasons other than Stuart loyalism. While 46% of the Jacobite army came from the

In contrast to 1715, many joined the Jacobites in 1745 for reasons other than Stuart loyalism. While 46% of the Jacobite army came from the Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands is an area of Scotland broadly covering the Scottish Highlands, plus Orkney, Shetland and Outer Hebrides (Western Isles).

The Highlands and Islands are sometimes defined as the area to which the Crofters' Act of 1886 ...

, there is no evidence this was any more common in the Highlands post-1715 than elsewhere in Scotland.McCann, Jean E (1963) ''The Organisation of the Jacobite Army'' (PHD thesis) Edinburgh University, OCLC 646764870, xix.

A key factor in recruiting was the feudal nature of clan society, which obliged tenants to provide their landlord with military service; the majority of Highland recruits came from a small number of western clans

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

whose leaders joined the rebellion, like Lochiel and Keppoch.McCann (1963), p.20 This obligation was based on traditional clan warfare, which was short-term and emphasised raiding, rather than set piece battles; even experienced Highland generals like Montrose in 1645 or Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

in 1689 struggled to keep their armies together and it continued to be a problem in 1745.

With the exception of the strongly Presbyterian south-west

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each se ...

, the Jacobites also recruited outside the Highlands, although inevitably some were coerced.Plank, Geoffrey. (2006) ''Rebellion and Savagery: the Jacobite Rising of 1745 and the British Empire'' Univ. of Pennsylvania, p.81 Jacobite leaders Lord George Murray, the Duke of Perth and Tullibardine had close links to Perthshire

Perthshire (locally: ; gd, Siorrachd Pheairt), officially the County of Perth, is a historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore in the east, to the Pass of Drumochter in the north, ...

, which supplied around 20% of total recruits.McCann (1963), xvi-xvii Another 24% came from the north-east, where John Gordon of Glenbucket

John Gordon of Glenbucket (c.1673 – 16 June 1750) was a Scottish Jacobite, or supporter of the claim of the House of Stuart to the British throne. Laird of a minor estate in Aberdeenshire, he fought in several successive Jacobite risings. Foll ...

was one of the first to join the Rising; support was focused around Auchmedden, Pitsligo

Pitsligo was a coastal parish in the historic county of Aberdeenshire, Scotland, containing the fishing villages of Rosehearty, Pittulie and Sandhaven,

and Fyvie

Fyvie is a village in the Formartine area of Aberdeenshire, Scotland.

Geography

Fyvie lies alongside the River Ythan and is on the A947 road.

Architecture

What in 1990, at least, was a Clydesdale Bank was built in 1866 by James Matthews. The ...

, areas Royalist and Episcopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the l ...

since the 1639 Bishops War.Pittock, Murray (1998) ''Jacobitism'', Macmillan, p.99

The northeastern ports in particular provided significant numbers; by some estimates, up to a quarter of the adult male population of Montrose saw Jacobite service.Pittock (1994) ''Poetry and Jacobite Politics in Eighteenth Century Britain and Ireland'', Uni. of Cambridge, p197 Long after the Rising was over, the region continued to feature in Government reports as a centre of Jacobite 'disaffection', with the shipmasters of Montrose, Stonehive, Peterhead

Peterhead (; gd, Ceann Phàdraig, sco, Peterheid ) is a town in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. It is Aberdeenshire's biggest settlement (the city of Aberdeen itself not being a part of the district), with a population of 18,537 at the 2011 Census. ...

and other ports involved in a two-way traffic of exiles and recruits for French service.

However, recruiting figures did not necessarily reflect majority opinion; even among 'Jacobite' clans like the MacDonalds, major figures like MacDonald of Sleat

Macdonald, MacDonald or McDonald may refer to:

Organisations

* McDonald's, a chain of fast food restaurants

* McDonald & Co., a former investment firm

* MacDonald Motorsports, a NASCAR team

* Macdonald Realty, a Canadian real estate brokerage ...

refused to join. The commercial centres of Edinburgh and Glasgow remained solidly pro-government, while in early November there were anti-Jacobite riots in Perth. This extended outside Scotland; after Prestonpans, Walter Shairp, a merchant from Edinburgh working in Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

, joined a local pro-government volunteer force known as the 'Liverpool Blues,' which participated in the second siege of Carlisle.

Recruiting methods and motivation

Jacobite recruiting methods in Scotland varied across the country. Adherence was fundamentally decided by personal or local factors,McCann (1963), xxi and often differed between officers and the rank and file.

Jacobite recruiting methods in Scotland varied across the country. Adherence was fundamentally decided by personal or local factors,McCann (1963), xxi and often differed between officers and the rank and file.

Volunteers

While many volunteered simply for adventure, Stuart loyalism played a part, as did attempts by Charles to follow his predecessors in appealing to disenfranchised groups in general, whether religious or political. The single most common issue for Scots volunteers was opposition to the 1707 Union between Scotland and England; after 1708, the exiled Stuarts explicitly appealed to this segment of society.Szechi, Daniel (1994) ''The Jacobites: Britain and Europe 1688-1788'', MUP, p.32 They included James Hepburn of Keith, a fierce critic of both Catholicism and James II who viewed Union as 'humiliating to his country....' Despite concerns over the impact on English sympathisers, Charles published two "Declarations" on 9 and 10 October, the first dissolving the "pretended Union," the second rejecting the 1701 Act of Settlement. A proposal to repeal the Malt Tax was particularly well received, one contemporary noting the rebels were "looked upon ..as the deliverers of their country". However, taxes have always been unpopular and while it caused riots when first imposed in 1725, these quickly tailed off; the most serious demonstrations occurred inGlasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, a town Charles noted as one 'where I have no friends and who are not at pains to hide it.'

Stuart support for religious toleration arose from their own Catholicism but its impact was limited. Modern use of the labels Episcopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the l ...

or Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

imply differences in doctrine; in 1745, they primarily related to differences over governance of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

or kirk, and the Nonjuring schism

The Nonjuring schism refers to a split in the State religion, established churches of England, Scotland and Ireland, following the deposition and exile of James II of England, James II and VII in the 1688 Glorious Revolution. As a condition of o ...

over swearing allegiance to the Hanoverians

The House of Hanover (german: Haus Hannover), whose members are known as Hanoverians, is a European royal house of German origin that ruled Hanover, Great Britain, and Ireland at various times during the 17th to 20th centuries. The house orig ...

. The vast majority of Scots, whether Episcopalian or Presbyterian, were doctrinal Calvinists

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

, which facilitated the post-1707 readmission of many Episcopalians to the kirk. By 1745, Non-juring congregations were concentrated along the north-east coast, and many recruits came from this element of society.

Conversely, these factors help explain the lack of English support. Many Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

abandoned the Stuarts in 1688 when James' policies seemed to threaten the primacy of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

; ensuring that remained a concern, whether it be from Catholics like Charles and his exile advisors or the Scots Calvinists that formed the bulk of his army. The only English town to provide any number of recruits was Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, also one of the very few to retain a significant Non-Juring congregation; its officers included three sons of its bishop Thomas Deacon

Thomas Deacon (2 September 1697 – 16 February 1753) was an English non-juror bishop, liturgical scholar and physician.

He was born to William and Cecelia Deacon. After his mother married the nonjuror bishop Jeremy Collier, the young Deacon ...

.

While

While Francis Towneley

Francis Towneley (9 June 1709 – 30 July 1746) was an English Catholic and supporter of the exiled House of Stuart or Jacobitism, Jacobite.

After service with the Kingdom of France, French army from 1728 to 1734, he returned to England and ...

, colonel of the Manchester Regiment

The Manchester Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in existence from 1881 until 1958. The regiment was created during the 1881 Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 63rd (West Suffolk) Regiment of Foot and the 96th ...

, and other Jacobite officers were Catholic, contrary to government propaganda participants at all levels were overwhelmingly Protestant.Of the prisoners held at Carlisle after the rising, only 8% were Catholic, though this may be affected by the composition of the Carlisle garrison. 68.2% were of the Church of Scotland (probably including Episcopalians) and 22.4% of the Church of England. Gildart to Sharpe, 26 Oct 1746 There was even a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

at Culloden, Jonathan Forbes, laird of Brux in Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 Subdivisions of Scotland#council areas of Scotland, council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially differe ...

, one of the only places in Scotland to establish a meaningful Non-Conformist presence during the period of religious toleration under the Protectorate

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, refers to the period from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659 during which England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland and associated territories were joined together in the Com ...

in the 1650s. Since a Stuart restoration was unlikely to improve the position of the Catholic Church, the link with Jacobitism was more likely a function of familial or other connections.McCann (1963), pp.135-143. There is no evidence the Catholic hierarchy approved of the rising, whereas the Non-Juring church appears to have actively encouraged it.

In this period, regiments were formed by appointing captains, who then recruited their own companies, for which they would be paid. The structured nature of society meant this required men with social and financial standing, who could first attract recruits, then equip and pay them in advance; it was here the lack of support from the English gentry was most felt. Many Scots Episcopalians were from the higher social classes, while the military obligations of clan service made this much easier in the Highlands; in the Atholl Brigade, most volunteers were officers, connected by religion and familial links to the House of Atholl but the rank and file were essentially a conscript force.McCann (1963), pp.48-9

Clan levies, vassalage and impressment

Many units were raised under the feudal obligation of vassalage, whereby tenants held land in return for military service. While this led authors like

Many units were raised under the feudal obligation of vassalage, whereby tenants held land in return for military service. While this led authors like John Prebble

John Edward Curtis Prebble, FRSL, OBE, (23 June 1915 – 30 January 2001) was an English journalist, novelist, and screenwriter. He is known for his studies of Scottish history.

Early life

He was born in Edmonton, Middlesex, England, but in 192 ...

to depict the Jacobites as a quasi-feudal army, the reality is more complex.Reid, "The Jacobite Army at Culloden" in Pollard (2009), 923

Clan chiefs in the north-west employed a traditional form of tenure requiring tacksmen to supply a number of armed sub-tenants on demand; this proved relatively successful, primarily because tenants strongly identified with the interests of their chief.McCann (1963), p.7 A similar system was used in Perthshire

Perthshire (locally: ; gd, Siorrachd Pheairt), officially the County of Perth, is a historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore in the east, to the Pass of Drumochter in the north, ...

and the north-east but here, tenants of landowners like Glenbucket held their leases in return for military service, irrespective of clan loyalties.McCann (1963), p.6

Rents were held at a low level due to this expectation and few tenants had written leases, increasing the pressure on them to comply.

The extent of coercion or "forcing out" has long been an area of dispute, since it was a common defence used by rebels taken prisoner. The authorities rigorously investigated such claims and the consensus among historians is impressment was a significant factor, both in recruiting and retaining men. The short-term patterns of clan warfare meant this was especially true among Highlanders; after Prestonpans and Falkirk, many went home to secure their plunder, a factor that delayed the invasion of England and led to the retreat from Stirling.

Lochiel and Keppoch were among those alleged to have used threats of violence or eviction to conscript their tenants.Seton, Sir Bruce (1928) ''The Prisoners of the '45'', vol I, Scottish History Society, p. 271 Lochiel's main agent in this process was his younger brother Archibald Cameron; on his return from exile in 1753, he was allegedly betrayed by Cameron clansmen in revenge and later executed.

North-eastern landowners also had difficulty in recruiting tenants, even in districts that provided large numbers in 1715. Alexander MacDonald, then with the Jacobite army in Musselburgh

Musselburgh (; sco, Musselburrae; gd, Baile nam Feusgan) is the largest settlement in East Lothian, Scotland, on the coast of the Firth of Forth, east of Edinburgh city centre. It has a population of .

History

The name Musselburgh is Ol ...

, wrote to his father in October 1745 that Lord Lewis Gordon was "putting into prison all who are not willing to rise." One member of the Atholl Brigade claimed Mrs Robertson, daughter of his feudal superior Lady Nairne, "threatened to burn his house and effects" if he did not join; another claimed he was given the choice of enlisting or paying £50 Scots for a substitute. Some recruits were "ignorant even of the name of the unit they had joined".Seton (1928), p.272

Decisions were sometimes made contrary to the wishes, or even threats, of their chief; the men of Glen Urquhart committed to the Rising only after a "lengthy and mature debate" held on a Sunday in Kilmore churchyard.Reid (2009) 957 Despite the supposed strength of feudal bonds, many of Keppoch's men deserted early on after a "private quarrel" with him.Seton (1928) p.283 Key predictors in recruiting seemed to have been a mixture of personal prestige or unequivocal action, with poor harvests in the Western Highlands in 1744 and 1745 also influencing enlistment among Highland farmers.McCann (1963), xx-xxi

Deserters and conscripts

The Jacobite Army tried to recruit from among prisoners taken in battle, and such so-called 'deserters' came to form a significant source of manpower. A large group were drafted into the Irish Picquets from Guise's 6th Regiment of Foot after the surrender of their garrisons at Inverness andFort Augustus

Fort Augustus is a settlement in the parish of Boleskine and Abertarff, at the south-west end of Loch Ness, Scottish Highlands. The village has a population of around 646 (2001). Its economy is heavily reliant on tourism.

History

The Gaeli ...

; 98 were retaken at Culloden of whom many would have faced summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes include ...

.Pittock (1998), p.110 Others, more accurately described as 'deserters', had previously absconded from the army in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

before returning to Scotland with the Irish Picquets or ''Royal Ecossais''.Reid (2012), p.13

Many of the Jacobite regiments were themselves affected quite heavily by desertion and during the later phases of the rebellion the Jacobite administration implemented an equivalent of the old Scottish 'fencible' system, demanding that landowners provide one properly equipped man for every £100 of rent.Pittock (2016) p.25 The quotas were filled in various ways and one third of the Jacobites from Banffshire

Banffshire ; sco, Coontie o Banffshire; gd, Siorrachd Bhanbh) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. The county town is Banff, although the largest settlement is Buckie to the west. It borders the Moray ...

were reported to have been 'hired out by the County': as with the British army, paid substitution was also common, in which an individual hired another person to serve in their place.Reid (2009) loc 1003 Such hired men were usually treated leniently after the Rising; many were released or simply left undisturbed at home.

The Jacobite recruiters could not afford to be selective and recruited many who would not have met later conscription standards. While some historical descriptions gave an impression of the Highland rank and file as being tall, healthy men in the prime of life, prisoner returns from after the Rising do not bear this out.Seton (1928) pp.228-9 The average height of Jacobite prisoners awaiting transportation in October 1746 was 5 feet 4.125 inches:Seton (1928) p.230 13.6% were 50 years old and upwards, while a further 8% were 16 and 17 year olds; contemporary observers commented on the "great number of boys and old men" in the Jacobite army.Seton (1928) p.232 A number were also recorded as having physical and other disabilities: one man of Keppoch's regiment was stated to be a deaf-mute

Deaf-mute is a term which was used historically to identify a person who was either deaf and used sign language or both deaf and could not speak. The term continues to be used to refer to deaf people who cannot speak an oral language or have som ...

; John MacLennan of Glengarry's had club feet; Hugh Johnston and Matthew Matthews of the Manchester Regiment were blind in one eye and deaf respectively; William Hargrave was described as having a "distemper'd brain" and Alexander Haldane as "wrong in his judgment".Seton (1928) pp.233-4

Regular soldiers in French service

When Charles sailed from France in July 1745, he was accompanied by ''Elizabeth,'' an elderly 64-gun warship carrying most of the weapons and volunteers from the French Army's Irish Brigade. They were intercepted by HMS ''Lion'' and after a four hour battle with ''Elizabeth,'' both were forced to return to port, depriving Charles of the regular soldiers originally intended as the core of the Jacobite army. Jacobite agents on the continent continued attempts to secure foreign backing; Daniel O'Brien, commander of the Franco-Irish ''Picquets'', negotiated withCarl Fredrik Scheffer

Carl Fredrik Scheffer (28 April 1715 – 27 August 1786) was a Swedish count, diplomat, privy counsellor, politician and writer. He was a Knight of the Royal Order of the Seraphim, and a Commander of the Order of the Polar Star.

Life

Scheffer's f ...

, Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

ambassador in France, seeking to enlist 1,000 troops to be shipped from France to Scotland.Behre, Goran "Sweden and the Rising of 1745", ''The Scottish Historical Review'', v.51, 152 part 2 (Oct 1972), 149 While French caution ultimately led to the failure of the Swedish initiative, in October 1745 French foreign minister d'Argenson agreed to provide assistance to the Jacobites.Reid (2012) p.29

Regular troops in the Jacobite army came from three main sources, the first being the Royal Scots or Royal Ecossais. Originally recruited in August 1744 by John Drummond, it was landed in Montrose in November 1745 but despite attempts to raise a second battalion in Scotland, never totalled more than 400. The second was the Irish Brigade; each of the six regiments supplied 50 men but only half evaded the Royal Navy blockade. The third was the Fitzjames

The House of FitzJames Stuart, or simply FitzJames, is a noble house founded by James FitzJames, 1st Duke of Berwick. He was the illegitimate son of James II & VII, King of England, Scotland and Ireland, a monarch of the House of Stuart.Ruvigny, ...

cavalry regiment; only one of the four squadrons despatched reached Scotland, and without their horses.

Including a small number of specialists, such as Mirabel de Gordon, the allegedly incompetent artillery officer who supervised the Siege of Stirling Castle

There have been at least eight sieges of Stirling Castle, a strategically important fortification in Stirling, Scotland. Stirling is located at the crossing of the River Forth, making it a key location for access to the north of Scotland.

The c ...

, this implies a maximum of 600 to 700 regular troops. The numbers were well documented because regulars were treated as prisoners of war, rather than rebels and so the British government tracked them very carefully. The Irish detachment suffered 25% losses at Culloden and their sacrifice was crucial in enabling Charles to escape but there were never enough of them.

Composition and organisation

Infantry

The Jacobite infantry was initially divided into two divisions, 'Highland' and 'Low Country Foot', nominally commanded by Murray and Perth, who was replaced by Charles after Carlisle. Following British army custom, they were split into

The Jacobite infantry was initially divided into two divisions, 'Highland' and 'Low Country Foot', nominally commanded by Murray and Perth, who was replaced by Charles after Carlisle. Following British army custom, they were split into regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

s, usually of one battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

, although some had two after the French model.Pittock (2016) p.44 Each battalion had a nominal strength of 200 to 300 men, although actual numbers were often much smaller, subdivided into companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared go ...

. The regiments of Lochiel, Glengarry and Ogilvy also had grenadier

A grenadier ( , ; derived from the word '' grenade'') was originally a specialist soldier who threw hand grenades in battle. The distinct combat function of the grenadier was established in the mid-17th century, when grenadiers were recruited fr ...

companies, although how these were distinguished is not recorded.

Highland regiments were traditionally organised by clan, officered by their own tacksmen; this made some impractically small and efforts were made to amalgamate them to produce more evenly sized units. Commissions were often used to reward those who brought in recruits, while O'Sullivan noted the Highlanders "would not mix or separate, & wou'd have double officers, hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

is two Captns & two Lts, to each Compagny, strong or weak".Reid (2009) 871 These factors meant the Jacobite army was over-officered, as recorded by the Master of Sinclair.Pittock (1998), p.42

While successful with Lowland recruits, Highland military tradition was unsuited to the European-style army O'Sullivan wanted to create. Even professional soldiers required constant training in firing and reloading; the Jacobites lacked time, weapons and ammunition, although Murray reportedly used a simplified but effective form of drill for them.Reid (2012) p.53 Some of the Lowland regiments, notably Ogilvy's, may have been taught musket drill based on the 1727 British army regulations.Pittock (2016) p.45 Most Jacobite professionals had been trained in France, and infantry drill and tactics showed a French influence: movement in narrow column formation, deployment of reserves in column, and firing in volleys followed by fire ''a billebaude'' (at will) as opposed to the rigid 'firings' by platoon used by the British army.Reid (2012) p.54 The French emphasis on shock tactics, rather than massed firepower, suited the abilities and training levels of the Jacobite troops.

Cavalry

Jacobite cavalry was small in number in 1745-6 and were restricted largely to scouting and other typical light cavalry duties. Despite this, the units that were raised arguably performed better in this role during the campaign than the regulars opposing them. All except one of the 'regiments' comprised two troops and were over-officered to an even greater degree than the infantry, as commissions were used to reward Jacobite support.

Jacobite cavalry was small in number in 1745-6 and were restricted largely to scouting and other typical light cavalry duties. Despite this, the units that were raised arguably performed better in this role during the campaign than the regulars opposing them. All except one of the 'regiments' comprised two troops and were over-officered to an even greater degree than the infantry, as commissions were used to reward Jacobite support.

Artillery

As with the cavalry, the Jacobite artillery was small and under-resourced, but was better organised than traditionally depicted. For most of the campaign it was led by a French regular, Captain James Grant of the ''Regiment Lally''. Grant arrived in October 1745 along with 12 French gunners, who were intended to train new recruits. At Edinburgh, he organised two companies of Perth's regiment as gunners, and later drafted a group from the Manchester Regiment as a pioneer company. The army was always short of heavy weapons, but during the invasion of England an artillery train was formed using six elderly guns captured from Cope at Prestonpans, six modern four-pounders captured at Fontenoy and shipped to Scotland by the French, and an obsolete 16th century brass cannon fromBlair Atholl

Blair Atholl (from the Scottish Gaelic: ''Blàr Athall'', originally ''Blàr Ath Fhodla'') is a village in Perthshire, Scotland, built about the confluence of the Rivers Tilt and Garry in one of the few areas of flat land in the midst of the Gr ...

.Seton (1923), p.11 Several of these guns and one company were left at Carlisle under Captain John Burnet of Campfield, a former British artillery regular.Seton (1928), p.303. Burnet was captured, sentenced to death, then reprieved and exiled; he later returned to Scotland.

Several larger siege guns were landed at Montrose in November, along with a number of three-pounders taken at Fontenoy. At Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

, Grant was absent due to a wound received at Fort William: the siege artillery was placed under the command of a Franco-Scottish engineer Loüis-Antoine-Alexandre-François de Gordon, usually known by the possible ''nom-de-guerre'' of the 'Marquis de Mirabelle'.Reid (1996) p.106 The abilities of "Mr. Admirable", as he was derisively called by the Scots, were not well-regarded and the artillery's placement and performance at Stirling were so poor it was suspected he had been bribed.Riding, p.343 Most of the siege artillery was abandoned when the Jacobites retreated.

At Fort Augustus

Fort Augustus is a settlement in the parish of Boleskine and Abertarff, at the south-west end of Loch Ness, Scottish Highlands. The village has a population of around 646 (2001). Its economy is heavily reliant on tourism.

History

The Gaeli ...

in March the artillery had some success; a French engineer mortared the fort's magazine, forcing its surrender.

Grant was still absent at Culloden, however, where the Jacobite field artillery was commanded by John Finlayson. It was quickly overwhelmed, despite the efforts of a French regular, Capt. du Saussay, to bring up a further gun towards the close of the battle.

Equipment

Traditional depictions of the Jacobite army often showed men dressed in Highland fashion and armed with

Traditional depictions of the Jacobite army often showed men dressed in Highland fashion and armed with broadsword

The basket-hilted sword is a sword type of the early modern era characterised by a basket-shaped guard that protects the hand. The basket hilt is a development of the quillons added to swords' crossguards since the Late Middle Ages.

In mod ...

s and targe

Targe (from Old Franconian ' 'shield', Proto-Germanic ' 'border') was a general word for shield in late Old English. Its diminutive, ''target'', came to mean an object to be aimed at in the 18th century.

The term refers to various types of shie ...

s, weaponry essentially unchanged since the 17th century. Such imagery suited both Government propaganda and the heroic traditions of Gaelic verse but was fundamentally exaggerated.Pittock (2016), p.40 While tacksmen and urban volunteers from the professions might carry a backsword

A backsword is a type of sword characterised by having a single-edged blade and a hilt with a single-handed grip. It is so called because the triangular cross section gives a flat back edge opposite the cutting edge. Later examples often have a ...

, or a broadsword if they were officers,Pittock (2016), p.42 in reality it appears that most men carried firelocks, and were drilled in accordance with up to date military practises.

At the start many of the Highland levies were poorly armed: one Edinburgh resident reported that the Jacobites carried a mixture of antiquated guns, agricultural tools like pitchfork

A pitchfork (also a hay fork) is an agricultural tool with a long handle and two to five tines used to lift and pitch or throw loose material, such as hay, straw, manure, or leaves.

The term is also applied colloquially, but inaccurately, to th ...

s and scythe

A scythe ( ) is an agricultural hand tool for mowing grass or harvesting crops. It is historically used to cut down or reap edible grains, before the process of threshing. The scythe has been largely replaced by horse-drawn and then tractor m ...

s and a few Lochaber axe

The Lochaber axe ( Gaëlic: tuagh-chatha) is a type of poleaxe that was used almost exclusively in Scotland. It was usually mounted on a staff about five feet long.

Specifics of the weapon

The Lochaber axe is first recorded in 1501, as an "old ...

s and swords.Reid (2009), 1078 Many officers and cavalrymen had pistols of local manufacture, the trade being centred in Doune

Doune (; from Scottish Gaelic: ''An Dùn'', meaning 'the fort') is a burgh within Perthshire. The town is administered by Stirling Council. Doune is assigned Falkirk postcodes starting "FK". The village lies within the parish of Kilmadock and mai ...

. At the start of the Rising Charles managed to procure a shipment of broadswords made cheaply in Germany (famously carrying the inscription "''Prosperity to Schotland and no Union''") and 2,000 targes. However, following the victory at Prestonpans and subsequent shipments of French and Spanish pattern 17.5 mm muskets into Montrose and Stonehaven, the army had access to modern firelocks fitted with bayonets, which formed the main weaponry of the rank and file. The men appear to have regarded the targes as an encumbrance and threw most of them away prior to Culloden.Reid (2009) 1109

Despite this, Jacobite officers recognised the psychological value of the "

Despite this, Jacobite officers recognised the psychological value of the "Highland charge

The Highland charge was a battlefield shock tactic used by the clans of the Scottish Highlands which incorporated the use of firearms.

Historical development

Prior to the 17th century, Highlanders fought in tight formations, led by a heavily ...

" against inexperienced troops, particularly as the broadsword inflicted wounds that were spectacular, if far less damaging than bullet wounds.Duffy (2009), 528 Lord George noted their reputation was such that at Penrith, Glengarry's regiment merely had to "throw their plaids" for a group of local militia to "ake

Ake (or Aké in Spanish orthography) is an archaeological site of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization. It's located in the municipality of Tixkokob, in the Mexican state of Yucatán; 40 km (25 mi) east of Mérida, Yucatán.

The name ...

off at the top gallop".Murray in Chambers (ed) (1834) ''Jacobite Memoirs of the Rebellion of 1745'', Chambers, p.65 Infantry tactics were strongly predicated on exploiting this effect to make the opposition break and run: eyewitness Andrew Henderson noted the Jacobites "making a dreadful huzza, and even crying 'Run, ye dogs'" as they closed with Barrell's regiment at Culloden.Henderson, Andrew (1753) ''The History of the Rebellion, 1745 and 1746'', A. Millar, p.327

The tactic was less successful when opposing troops held their ground, particularly as it was customary to fire a single shot at close range, then drop the firearm and charge home with the sword. Once their charge was held up at Culloden, the Highlanders were reduced to throwing stones at the government troops, unable to respond in any other way.Royle (2016), p.96

As an insurgent army, the Jacobites did not have a formal uniform and most men initially wore the clothes they joined in, whether the coat and breeches of the Lowlands or the short coat and plaid of the Highlands. Notable exceptions were Charles's Lifeguard, who were issued with blue coats faced with scarlet, as were the ''Royal Ecossais''; the Irish Brigade, as the lineal descendant of James II's Royal Irish Army

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a ci ...

, wore their traditional red coats. The well-dressed cavalry were used in an attempt to impress the local populace in several places: an observer at Derby said that they were "likely young men" who "made a fine show", whereas the infantry "appeared more like a parcel of chimney sweeps".Wemyss, A (2003) ''Elcho of the '45'', Saltire Society, p.95

As a basic sign of Stuart allegiance all men wore a white cockade and many wore, or were issued with, the characteristic knitted and felted blue bonnet, including the ''Royal Ecossais''.Reid (1996), p.90 There was frequent use of various forms of saltire

A saltire, also called Saint Andrew's Cross or the crux decussata, is a heraldic symbol in the form of a diagonal cross, like the shape of the letter X in Roman type. The word comes from the Middle French ''sautoir'', Medieval Latin ''saltator ...

as a badge, including on regimental standards. As the rebellion went on, however, there is evidence that the Jacobite leadership began to use clothing made up of tartan cloth as a simple form of uniform irrespective of the origin of the troops wearing it.Pittock in Black (ed) ''Culture and Society in Britain 1660-1800'', MUP, pp.137-8 Tartan cloth was readily available in quantity, served to distinctively identify the Jacobites, and was exploited by the rebels both as a symbol of Stuart loyalty and, increasingly, of Scottish identity. An intelligence report sent to the Duke of Atholl, however, reached the conclusion that the Jacobites were primarily "puting now many of the Lowlanders in highland dress, to make the number of Highlanders appear

more".Atholl (1908) ''Chronicles of the Atholl and Tullibardine Families'', vIII, p.68

Pay

Accounts maintained by Lawrence Oliphant of Gask, who was deputy commander under Strathallan at Perth, show that a fixed scale of pay was maintained until relatively late in the campaign. Private soldiers were paid 6d. per day, while sergeants received 9d.; officers' pay ranged from ensigns at 1s.6d. per day to colonels at 6s.McCann (1963), pp.183-184 There was however little consistency in how individual regiments were paid by their colonels and men were paid at intervals ranging from one to 21 days: although generally paid in advance some companies received theirs in arrears.McCann (1963), p.194 From February 1746 pay rates went into a decline, in addition to falling into arrears. The narratives of James Maxwell of Kirkconnell and of Murray suggest that by March money had run out completely, and that men were instead paid weekly inoatmeal

Oatmeal is a preparation of oats that have been de-husked, steamed, and flattened, or a coarse flour of hulled oat grains (groats) that have either been milled (ground) or steel-cut. Ground oats are also called white oats. Steel-cut oats are ...

.

Statistics

A detailed examination of available records concluded that the maximum operational force available to the Jacobites was about 9,000 men, with the total recruitment during the campaign possibly reaching as high as 13,140 exclusive of Franco-Irish reinforcements.McCann (1963), xi The gap between two figures could be explained by desertion, although it also seems probable that many enlistment figures were based on over-optimistic reports by Jacobite agents.McCann (1963), xv The vast majority of battlefield casualties during the campaign - around 1,500 - occurred at Culloden. Although many Jacobites went into hiding or simply returned home after dismissal, a total of 3,471 men were recorded as prisoners after the rebellion, though this figure probably includes some double counting, French POWs, and civilians. From these there were around 40 summary executions of 'deserters' and 73 executions after trial; 936 were sentenced to or volunteered for transportation; and 7-800 were drafted into the ranks of the British Army, often for service in the colonies. The remainder, with the exception of a few senior officers still at large, were pardoned by a 1747 Act of Indemnity.References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Jacobitism Jacobite rising of 1745 Military units and formations established in 1745 Military units and formations disestablished in 1746