Jacob Duché on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

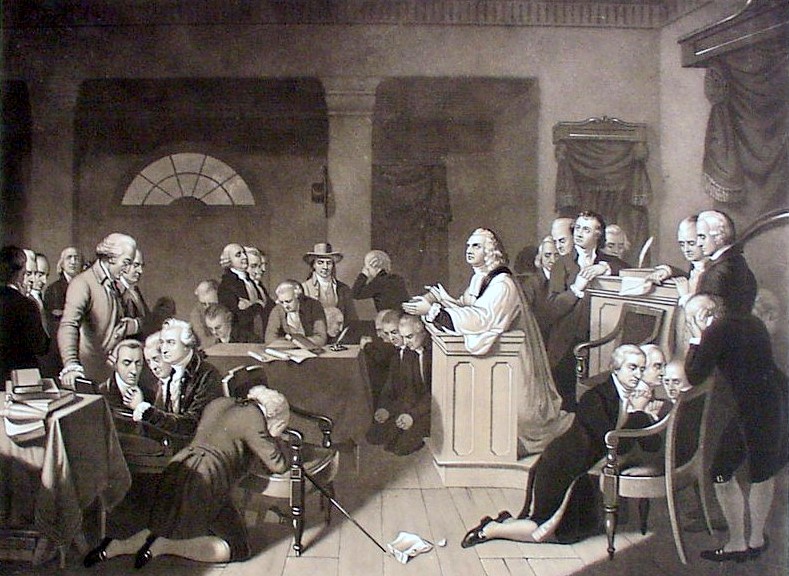

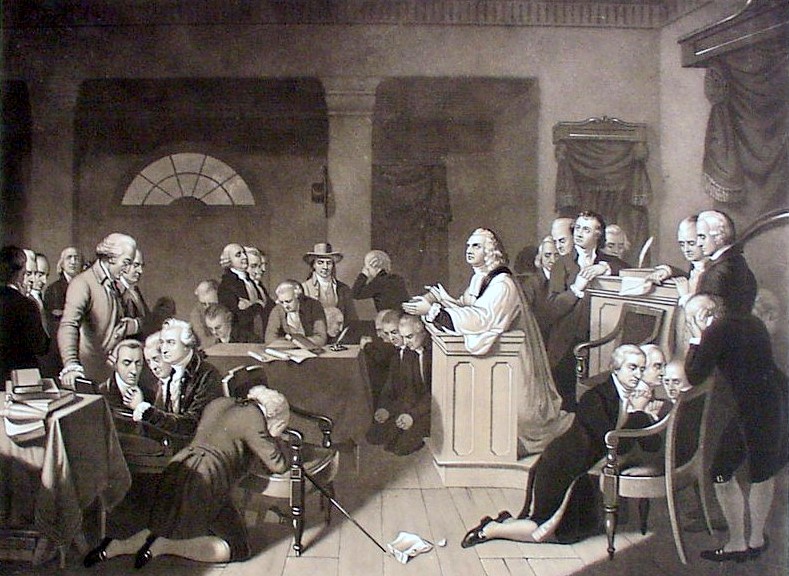

The Reverend Jacob Duché (1737–1798) was a

The prayer had a profound effect on the delegates, as recounted by

The prayer had a profound effect on the delegates, as recounted by

Biography and portrait

at the

Duché's letter to George Washington

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Duche, Jacob History of Philadelphia Clergy from Philadelphia American Episcopal priests University of Pennsylvania alumni Clergy in the American Revolution Continental Congress Religion and politics People of colonial Pennsylvania Huguenot participants in the American Revolution 1737 births 1798 deaths Burials at St. Peter's churchyard, Philadelphia

Rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of Christ Church in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; (Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Ma ...

, and the first chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intellige ...

to the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

.

Biography

Duché was born in Philadelphia in 1737, the son of Colonel Jacob Duché, Sr., latermayor of Philadelphia

The mayor of Philadelphia is the chief executive of the government of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

as stipulated by the Charter of the City of Philadelphia. The current mayor of Philadelphia is Jim Kenney.

History

The first mayor of Philadelphia, ...

(1761–1762) and grandson of Anthony Duché, a French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Bez ...

. He was educated at the Philadelphia Academy and then in the first class of the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universit ...

), where he also worked as a tutor of Greek and Latin. After graduating as valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the highest-performing student of a graduating class of an academic institution.

The valedictorian is commonly determined by a numerical formula, generally an academic institution's grade point average (GPA) ...

in 1757, he studied briefly at Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

before being ordained an Anglican clergyman by the Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or offic ...

and returning to the colonies.

In 1759 he married Elizabeth Hopkinson, sister of Francis Hopkinson

Francis Hopkinson (October 2,Hopkinson was born on September 21, 1737, according to the then-used Julian calendar (old style). In 1752, however, Great Britain and all its colonies adopted the Gregorian calendar (new style) which moved Hopkinson's ...

, a signer of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of ...

. In 1768, he was elected to the American Society.

Duché first came to the attention of the First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from 12 of the 13 British colonies that became the United States. It met from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, after the British Nav ...

in September 1774, when he was summoned to Carpenters' Hall to lead the opening prayers. Opening the session on the 7th of that month, he read the 35th Psalm, and then broke into extemporaneous prayer.

The prayer had a profound effect on the delegates, as recounted by

The prayer had a profound effect on the delegates, as recounted by John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

to his wife.

On July 4, 1776, when the United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

was ratified

Ratification is a principal's approval of an act of its agent that lacked the authority to bind the principal legally. Ratification defines the international act in which a state indicates its consent to be bound to a treaty if the parties inte ...

, Duché, meeting with the church's vestry, passed a resolution

Resolution(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Resolution (debate), the statement which is debated in policy debate

* Resolution (law), a written motion adopted by a deliberative body

* New Year's resolution, a commitment that an individual ma ...

stating that the name of King George III of Great Britain

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

was no longer to be read in the prayers of the church. Duché complied, crossing out said prayers from his Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 ...

, committing an act of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

against England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, an extraordinary and dangerous act for a clergyman who had taken an oath of loyalty to the King. On July 9, Congress elected him its first official chaplain.

When the British occupied Philadelphia in September 1777, Duché was arrested by General William Howe

William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, KB PC (10 August 172912 July 1814) was a British Army officer who rose to become Commander-in-Chief of British land forces in the Colonies during the American War of Independence. Howe was one of three brot ...

and detained, underlining the seriousness of his actions. He was later released, and emerged as a Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

and propagandist for the British, at which time he wrote a famous letter to General George Washington, camped at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania

The Village of Valley Forge is an unincorporated settlement located on the west side of Valley Forge National Historical Park at the confluence of Valley Creek and the Schuylkill River in Pennsylvania. The remaining village is in Schuylkill To ...

, in which he begged him to lay down arms and negotiate for peace with the British. Suddenly, Duché went from hero of the Revolutionary cause to outcast in the new United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

. He was convicted of high treason to the State of Pennsylvania, and his estate was confiscated. In consequence, Duché fled to England, where he was appointed chaplain to the Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, in the London Borough of Lambeth, historically in the County of Surrey. It is situated south of Charing Cross. The population of the London Borough of Lambeth was 303,086 in 2011. The area ex ...

orphan asylum, and soon made a reputation as an eloquent preacher. He was not able to return to America until 1792, after he had suffered a stroke.

On October 1, 1777, Congress appointed joint chaplains, William White, Duché's successor at Christ Church, and George Duffield

__NOTOC__

George Duffield MBE (born 30 November 1946) is an English retired flat racing jockey.

He served a seven-year apprenticeship with Jack Waugh, and rode his first winner on 15 June 1967 at Great Yarmouth Racecourse on a horse called ...

, pastor of the Third Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia.

Duché died in 1798 in Philadelphia, where he is buried in St. Peter's churchyard.

His daughter, Elizabeth Sophia Duché (born on September 18, 1774, Philadelphia; died on December 11, 1808, Montréal), married Captain John Henry in 1799. Henry was an Army officer and political adventurer who was indirectly instrumental in the declaration of war on Great Britain by the United States in 1812.

Citations

Sources

* *Further reading

* Dellape, Kevin J. ''America's First Chaplain: The Life and Times of the Reverend jacob Duché.'' Bethlehem, PA: Lehigh University Press, 2013. * McBride, Spencer W. ''Pulpit and Nation: Clergymen and the Politics of Revolutionary America.'' Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2016. *Gough, Deborah. ''Christ Church, Philadelphia''. 1. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1995. *Simpson, Henry, ''The Lives of Eminent Philadelphians, Now Deceased.'' Philadelphia: William Brotherhead, 1859.External links

Biography and portrait

at the

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universit ...

Duché's letter to George Washington

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Duche, Jacob History of Philadelphia Clergy from Philadelphia American Episcopal priests University of Pennsylvania alumni Clergy in the American Revolution Continental Congress Religion and politics People of colonial Pennsylvania Huguenot participants in the American Revolution 1737 births 1798 deaths Burials at St. Peter's churchyard, Philadelphia