Jack Seely on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

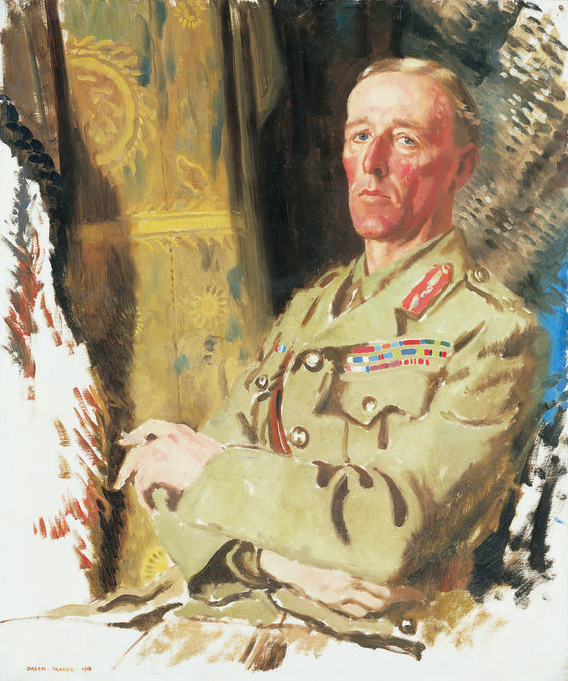

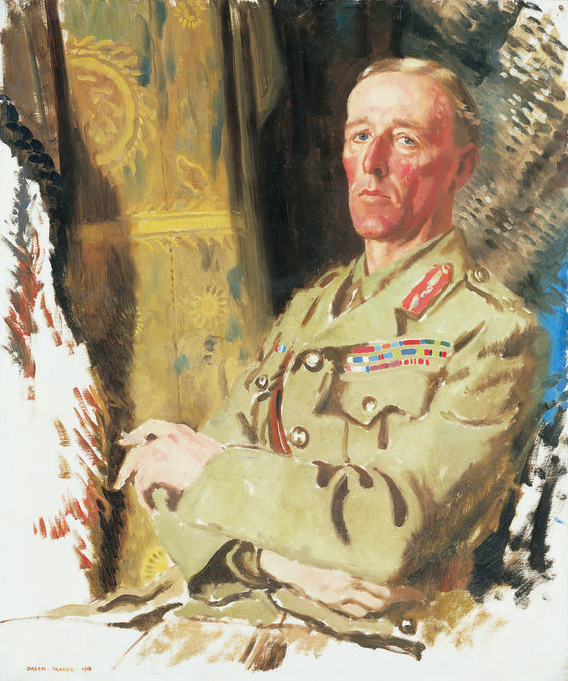

John Edward Bernard Seely, 1st Baron Mottistone, (31 May 1868 – 7 November 1947), also known as Jack Seely, was a

During the German Spring Offensive Seely, back from London, called on Percy Beddington, a senior staff officer of the Fifth Army, at around 2am on 24 March 1918, to inform him of the gossip in London that Fifth Army had been routed. Beddington, who had only managed to get to sleep an hour previously, for the first time since the morning of 21 March, on a camp bed in his office, recorded that he "lost (his) temper, cursed him up hill and down dale for daring to wake (him) with such drivel." Seely himself later admitted that it suddenly seemed unimportant a few days later when he was commanding the CCB in action, but it mattered a great deal in the next few days when Gough was sacked from command of the Army as a scapegoat.

After being gassed in 1918, he returned to England, and was relieved of command of the brigade on 20 May 1918. He was angry about the move.

Seely had remained an MP throughout his military service in the First World War, and as a member of the Liberal faction which supported Lloyd George's coalition government, he was appointed

During the German Spring Offensive Seely, back from London, called on Percy Beddington, a senior staff officer of the Fifth Army, at around 2am on 24 March 1918, to inform him of the gossip in London that Fifth Army had been routed. Beddington, who had only managed to get to sleep an hour previously, for the first time since the morning of 21 March, on a camp bed in his office, recorded that he "lost (his) temper, cursed him up hill and down dale for daring to wake (him) with such drivel." Seely himself later admitted that it suddenly seemed unimportant a few days later when he was commanding the CCB in action, but it mattered a great deal in the next few days when Gough was sacked from command of the Army as a scapegoat.

After being gassed in 1918, he returned to England, and was relieved of command of the brigade on 20 May 1918. He was angry about the move.

Seely had remained an MP throughout his military service in the First World War, and as a member of the Liberal faction which supported Lloyd George's coalition government, he was appointed

Burke's Peerage and Baronetage 107th Edition Volume III

*Dictionary of National Biography, 1941–1950.

richardlangworth.comexpress.co.ukwarriorwarhorse.com

* * * * , essay on Seely written by Roger Fulford, revised by Mark Pottle * *

J.E.B. Seely

at National Registry of Archives

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography – Seely, John Edward Bernard

(requires login) * *

– Extended story of the Canadian cavalry horse {{DEFAULTSORT:Mottistone, J. E. B. Seely, 1st Baron 1868 births 1947 deaths Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge British Army cavalry generals of World War I British Army personnel of the Second Boer War British Secretaries of State Seeley, J.E.B Deputy Lieutenants of the Isle of Wight Seely, J.E.B Lord-Lieutenants of Hampshire Members of the Inner Temple Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom People educated at Harrow School Secretaries of State for War (UK) Seely, J. E. B. Seely, J. E. B. Seely, J. E. B. Seely, J. E. B. Seely, J. E. B. Seely, J. E. B. UK MPs who were granted peerages Seely, J. E. B. Imperial Yeomanry officers Members of Parliament for the Isle of Wight Hampshire Yeomanry officers Barons in the Peerage of the United Kingdom Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George Companions of the Order of the Bath Commandeurs of the Légion d'honneur Recipients of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) Deputy Lieutenants of Hampshire J.E.B. Military personnel from Derbyshire Barons created by George V British Army major generals

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

general and politician. He was a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MP) from 1900 to 1904 and a Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

MP from 1904 to 1922 and from 1923 to 1924. He was Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

for the two years prior to the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, before being forced to resign as a result of the Curragh Incident

The Curragh incident of 20 March 1914, sometimes known as the Curragh mutiny, occurred in the Curragh, County Kildare, Ireland. The Curragh Camp was then the main base for the British Army in Ireland, which at the time still formed part of the U ...

. He led one of the last great cavalry charges in history at the Battle of Moreuil Wood on his war horse

The first evidence of horses in warfare dates from Eurasia between 4000 and 3000 BC. A Sumerian illustration of warfare from 2500 BC depicts some type of equine pulling wagons. By 1600 BC, improved harness and chariot design ...

Warrior

A warrior is a person specializing in combat or warfare, especially within the context of a tribal or clan-based warrior culture society that recognizes a separate warrior aristocracies, class, or caste.

History

Warriors seem to have been p ...

in March 1918. Seely was a great friend of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

and the only former cabinet minister to go to the front in 1914 and still be there four years later.

Background

Seely was born at Brookhill Hall in the village ofPinxton

Pinxton is a village and civil parish in Derbyshire on the eastern boundary of Nottinghamshire, England, just south of the Pinxton Interchange at Junction 28 of the M1 motorway where the A38 road meets the M1. Pinxton is part of the Bolsover ...

in Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

on 31 May 1868.Matthew 2004 pp674-6 He was the seventh child, and fourth son, of Sir Charles Seely, 1st Baronet

Colonel Sir Charles Seely, 1st Baronet KGStJ, DL (11 August 1833 – 16 April 1915) was a British industrialist and politician.

Seely was Liberal Party Member of Parliament (MP) for Nottingham from 1869 to 1874 and 1880 to 1885, and for Nott ...

(1833–1915).

Seely was a member of a family of politicians, industrialists and significant landowners. His grandfather Charles Seely (1803–1887) was a noted Radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

and philanthropist and was famous for hosting Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

, the Italian revolutionary hero, in London and the Isle of Wight in 1864. Seely's father and brother Sir Charles Seely, 2nd Baronet

Sir Charles Hilton Seely, 2nd Baronet, VD, KGStJ (7 July 1859 – 26 February 1926) was a British industrialist, landowner and Liberal Unionist (later Liberal Party) politician who served as Member of Parliament (MP) for Lincoln from 1895 to 190 ...

were also MPs, as would later be his nephew Sir Hugh Seely, 3rd Baronet and 1st Baron Sherwood, who became Under-Secretary of State for Air

The Under-Secretary of State for Air was a junior ministerial post in the United Kingdom Government, supporting the Secretary of State for Air in his role of managing the Royal Air Force. It was established on 10 January 1919, replacing the previou ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

The family had homes in Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated Notts.) is a landlocked county in the East Midlands region of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. The traditi ...

and the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

as well as extensive property in London. He is still associated with the Isle of Wight, where he spent his holidays whilst growing up. His aunt's husband, Colonel Harry Gore Browne, won the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

during the Indian Mutiny

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the fo ...

. Gore Browne was manager of the extensive Seely estates on the Isle of Wight. Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

lived nearby at her favourite residence, Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house himself, in t ...

.

Early life

He was educated atHarrow School

(The Faithful Dispensation of the Gifts of God)

, established = (Royal Charter)

, closed =

, type = Public schoolIndependent schoolBoarding school

, religion = Church of E ...

, where he fagged for Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

. He also met Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, who became a lifelong friend. He then studied at Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by Henry VIII, King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge ...

1887–90.

Seely served in the Hampshire Yeomanry

The Hampshire Yeomanry was a yeomanry cavalry regiment formed by amalgamating older units raised between 1794 and 1803 during the French Revolutionary Wars. It served in a mounted role in the Second Boer War and World War I, and in the air defenc ...

, in which he was commissioned as a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

, while still an undergraduate, on 7 December 1889. He was promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

on 23 December 1891 and to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on 31 May 1892.

He joined the Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional associations for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wal ...

and was called to the Bar in 1897.

Second Boer War

Following the outbreak of theSecond Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

he was commissioned as a captain in the Imperial Yeomanry

The Imperial Yeomanry was a volunteer mounted force of the British Army that mainly saw action during the Second Boer War. Created on 2 January 1900, the force was initially recruited from the middle classes and traditional yeomanry sources, but su ...

on 7 February 1900, having succeeded in arranging transport to South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

for his squadron the same week, with the assistance of his uncle Sir Francis Evans, 1st Baronet, chairman of the Union Castle Line

The Union-Castle Line was a British shipping line that operated a fleet of passenger liners and cargo ships between Europe and Africa from 1900 to 1977. It was formed from the merger of the Union Line and Castle Shipping Line.

It merged with ...

. He is remembered in South Africa as the commander that placed the 14-year-old Japie Greyling (1890-1954) against a wall in front of a firing squad, threatening to have him executed if he did not provide information about the Boer forces in the area. The boy refused to cooperate, and was freed. Several memorials still exist in South Africa today, attesting to the remarkable story.

He served bravely, if a little insubordinately. He was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

and awarded a medal with four clasps, as well as the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typ ...

(DSO) in November 1900.

Early political career

Whilst still on active service in South Africa during the Boer War, Seely was electedMember of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

for the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

as a Conservative at a by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

in May 1900 and re-elected at the "Khaki" General Election that autumn.

On 10 August 1901, he was promoted to the rank of major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

in the yeomanry, with the honorary rank of captain in the Army from 10 July. Seely was appointed a deputy lieutenant of the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

in 1902.

Along with Winston Churchill and Lord Hugh Cecil he attacked the Balfour government's neglect of the Army. He was a strong believer in free trade and was unhappy with the Unionist (Conservative) Party's increasing support for Tariff Reform (protectionism). He also opposed the Balfour government's support for the use of Chinese Slavery in South Africa. He left the Conservative Party in March 1904 mainly over these two issues and challenged the Conservative Party to oppose him running as an Independent Conservative at the 1904 Isle of Wight by-election. They declined and he was returned unopposed.

He was narrowly elected Liberal MP for Liverpool Abercromby at the 1906 General Election.

Seely was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

in the Hampshire Yeomanry

The Hampshire Yeomanry was a yeomanry cavalry regiment formed by amalgamating older units raised between 1794 and 1803 during the French Revolutionary Wars. It served in a mounted role in the Second Boer War and World War I, and in the air defenc ...

on 20 June 1907, and to colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

on 31 March 1908; he was therefore known as "Colonel Seely" during his time as a politician before the First World War.

Under-Secretary of State

In 1908, the new Prime MinisterH. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

appointed him Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies The Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies was a junior Ministerial post in the United Kingdom government, subordinate to the Secretary of State for the Colonies and, from 1948, also to a Minister of State.

Under-Secretaries of State for the Col ...

, in place of Winston Churchill who had been promoted to the Cabinet. According to the ''Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', "Since his chief, Lord Crewe, was in the Lords, important work fell to the under-secretary, in particular the South Africa Act 1909

The South Africa Act 1909 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which created the Union of South Africa from the British Cape Colony, Colony of Natal, Orange River Colony, and Transvaal Colony. The Act also made provisions for pote ...

, which brought about the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Trans ...

." He became a member of the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

in 1909. Seely was also amongst those Liberals who strongly supported Lloyd George's budgets of 1909 and 1910.

Seely was defeated for Abercromby at the January 1910 General Election and returned to Parliament for Ilkeston

Ilkeston is a town in the Borough of Erewash, Derbyshire, England, on the River Erewash, from which the borough takes its name, with a population at the 2011 census of 38,640. Its major industries, coal mining, iron working and lace making/texti ...

in Derbyshire at a by-election later in 1910, holding that seat until 1922. In October 1910, he was awarded the Territorial Decoration

__NOTOC__

The Territorial Decoration (TD) was a military medal of the United Kingdom awarded for long service in the Territorial Force and its successor, the Territorial Army. This award superseded the Volunteer Officer's Decoration when the Te ...

.

Secretary of State for War

Appointment and policies

Seely then served asUnder-Secretary of State for War

The position of Under-Secretary of State for War was a British government position, first applied to Evan Nepean (appointed in 1794). In 1801 the offices for War and the Colonies were merged and the post became that of Under-Secretary of State for ...

from 1911 to 1912. As a yeomanry colonel, he did not support conscription, which General Henry Wilson favoured. "Ye Gods" was how Wilson greeted his appointment in his diary.Jeffery 2006, p109-10

Seely was already a member of the Committee of Imperial Defence

The Committee of Imperial Defence was an important ''ad hoc'' part of the Government of the United Kingdom and the British Empire from just after the Second Boer War until the start of the Second World War. It was responsible for research, and som ...

. In June 1912, apparently on Churchill's suggestion, Seely was promoted to the Cabinet as Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

, in succession to Haldane. He held the post until 1914. With Sir John French

Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres, (28 September 1852 – 22 May 1925), known as Sir John French from 1901 to 1916, and as The Viscount French between 1916 and 1922, was a senior British Army officer. Born in Kent to ...

he was responsible for the invitation to General Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general and military theorist who served as the Supreme Allied Commander during the First World War. An aggressive, even reckless commander at the First Marne, Flanders and Art ...

to attend the Army Manoeuvres of 1912 and was active in preparing the army for war with Germany. Seely supported General Wilson when he gave evidence to the Committee of Imperial Defence

The Committee of Imperial Defence was an important ''ad hoc'' part of the Government of the United Kingdom and the British Empire from just after the Second Boer War until the start of the Second World War. It was responsible for research, and som ...

(CID) in November 1912 that the presence of the British Expeditionary Force on the continent would have a decisive effect in any future war.Jeffery 2006, p109-10 The mobility of the proposed Expeditionary Force, and in particular the development of a Flying Corps (the origin of the modern Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

) were his special interests. According to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'', these developments played a significant role in the victory during World War I.

In April 1913 Seely told the House of Commons that the Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was a part-time volunteer component of the British Army, created in 1908 to augment British land forces without resorting to conscription. The new organisation consolidated the 19th-century Volunteer Force and yeomanry i ...

could see off an invasion by 70,000 men and that the General Staff opposed conscription. Sir John French

Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres, (28 September 1852 – 22 May 1925), known as Sir John French from 1901 to 1916, and as The Viscount French between 1916 and 1922, was a senior British Army officer. Born in Kent to ...

(Chief of the Imperial General Staff

The Chief of the General Staff (CGS) has been the title of the professional head of the British Army since 1964. The CGS is a member of both the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Army Board. Prior to 1964, the title was Chief of the Imperial G ...

) obtained a partial retraction after Wilson had threatened that he and his two fellow Directors at the War Office would resign in protest at the "lie", but Wilson felt that French's recent promotion to Field Marshal had made him reluctant to clash with Liberal Ministers. During the CID "Invasion Inquiry" (debates of 1913–14 as to whether some British regular divisions should be retained at home to defeat a potential invasion), Seely lobbied in vain for all six divisions to be sent to France in the event of war. French became very friendly with Seely when his first wife died in childbirth in August 1913.

Curragh incident

WithIrish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1 ...

due to become law in 1914, and the Cabinet contemplating some kind of military action against the Ulster Volunteers

The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the ...

who wanted no part of it, French and Seely summoned Paget Paget is a surname of Anglo-Normans, Anglo-Norman origin which may refer to:

* Lord Alfred Paget (1816–1888), British soldier, courtier and politician

* Almeric Paget, 1st Baron Queenborough (1861–1949), British cowboy, industrialist, yachtsman ...

(Commander-in-Chief, Ireland

Commander-in-Chief, Ireland, was title of the commander of the British forces in Ireland before 1922. Until the Act of Union in 1800, the position involved command of the distinct Irish Army of the Kingdom of Ireland.

History Marshal of Ireland

...

) to the War Office for talks, whilst Seely wrote to the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

(24 October 1913) about the potential use of General Macready, who had experience of peacekeeping in the South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

coalfields in 1910, and had been consulted by Birrell (Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant, and officially the "Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant", from the early 19th century un ...

) about the use of troops in the 1912 Belfast riots. In October 1913 Seely sent him to report on the police in Belfast and Dublin.

There was more discussion about the Army's stance over Home Rule ''outside'' the Army than within it. Seely spoke to the assembled Commanders-in-Chief of the Army's six Regional Commands, to remind them of their responsibility to uphold the civil power. They met at the War Office on 16 December 1913 with French and the Adjutant-General Spencer Ewart

Lieutenant-General Sir John Spencer Ewart (22 March 1861 – 19 September 1930) was a British Army officer who became Adjutant-General to the Forces, but was forced to resign over the Curragh Incident.

Early life and education

Ewart was born ...

present. He assured them that the Army would not be called upon for "some outrageous action, for instance, to massacre a demonstration of Orangemen", but nonetheless officers could not "pick and choose" which lawful orders they would obey, and that any officer who attempted to resign on the issue should instead be dismissed. This did not stop tensions about the Army's role from growing.

By March 1914 intelligence reported that the Ulster Volunteers, now 100,000 strong, might be about to seize the ammunition at Carrickfergus Castle

Carrickfergus Castle (from the Irish ''Carraig Ḟergus'' or "cairn of Fergus", the name "Fergus" meaning "strong man") is a Norman castle in Northern Ireland, situated in the town of Carrickfergus in County Antrim, on the northern shore of B ...

, and political negotiations were deadlocked as the Ulster Protestant leader Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, PC, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician, barrister and judge, who served as the Attorney General and Solicito ...

was demanding that Ulster have a complete, not just temporary, opt-out from Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

. Seely was on the five-man Cabinet Committee on Ireland (along with Crewe

Crewe () is a railway town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. The Crewe built-up area had a total population of 75,556 in 2011, which also covers parts of the adjacent civil parishes of Willaston ...

, Simon

Simon may refer to:

People

* Simon (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name Simon

* Simon (surname), including a list of people with the surname Simon

* Eugène Simon, French naturalist and the genus ...

, Birrell and Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

(First Lord of the Admiralty)). General Paget, who was reluctant to move in case it exacerbated the crisis, was summoned to London. On 14 March 1914 the Committee warned Paget of the perceived need to occupy the arms depots to prevent the Ulster Volunteers from doing so. Seely repeatedly assured French of the accuracy of intelligence that Ulster Volunteers might march on Dublin. No trace of Seely's intelligence survives. It has been suggested, e.g. by Sir James Fergusson, that the move to deploy troops may have been a "plot" by Churchill and Seely to goad Ulster into a rebellion which could then be put down, although this view is not universally held. Carson departed London for Ulster on 19 March, amidst talk that he was to form a provisional government.

No written orders had been issued to Paget. It had been agreed that officers domiciled in Ulster would be allowed to "disappear" for the duration of the crisis, with no blot on their career records, but that other officers who objected were to be dismissed rather than being permitted to resign. Although the ODNB concurs that Seely was foolish in effectively giving ''any'' officers discretion over which orders to obey, he was keen to keep Paget on the government's side and maintain the unity of the Army. The move to deploy troops resulted in the Curragh incident

The Curragh incident of 20 March 1914, sometimes known as the Curragh mutiny, occurred in the Curragh, County Kildare, Ireland. The Curragh Camp was then the main base for the British Army in Ireland, which at the time still formed part of the U ...

of 20 March, in which Gough and many other officers threatened to resign. The elderly Field-Marshal Roberts, whom Seely had told the King was "at the bottom" of the matter, thought Seely "drunk with power".

The peccant paragraphs

On the morning of Monday 23 March, Seely had a meeting with Gough, with Paget, French and Spencer Ewart in attendance. Seely, who – by Gough's account – attempted unsuccessfully to browbeat him by staring at him, accepted French's suggestion that a written document from the Army Council might help to convince Gough's officers.Holmes 2004, pp. 184-8. Seely took over a draft document to a Cabinet meeting for approval. Seely had to leave the meeting for an audience with the King, and in his absence the Cabinet agreed a text, stating that the Army Council were satisfied that the incident had been a misunderstanding, and that it was "the duty of all soldiers to obey lawful commands". Seely, assisted by Viscount Morley, later added two paragraphs, stating that the Crown had the right to use force in Ireland or elsewhere, but had no intention of doing so "to crush political opposition to the policy or principles of the Home Rule Bill". This was initialled by Seely, French and Ewart and then given to Gough. It is unclear whether this – amending a Cabinet document without Cabinet approval – was an honest blunder on Seely's part or whether he was encouraged to do so and then made a scapegoat. Gough, on the advice of Maj-GenWilson

Wilson may refer to:

People

* Wilson (name)

** List of people with given name Wilson

** List of people with surname Wilson

* Wilson (footballer, 1927–1998), Brazilian manager and defender

* Wilson (footballer, born 1984), full name Wilson Ro ...

, then insisted on adding another paragraph clarifying that the Army would not be used to enforce Home Rule ''on Ulster'', with which French concurred in writing. Seely had not been consulted about this second assurance.

Asquith publicly repudiated the "peccant paragraphs" (25 March). Talk of a government "plot" was now widespread amongst the Opposition. Seely accepted the blame in the House of Commons on 25 March and offered to resign to protect French and Ewart; Asquith initially refused to accept his resignation, despite writing to Venetia Stanley

Venetia Anastasia Digby (née Stanley) (December 1600 – 1 May 1633) was a celebrated beauty of the Stuart period and the wife of a prominent courtier and scientist, Kenelm Digby. She was a granddaughter of Thomas Percy, 7th Earl of North ...

that he blamed the crisis on "Paget's tactless blundering" and "Seely’s clumsy phrases". By 30 March it was clear that Asquith, to his regret, would now have to insist that Seely resign, along with French and Ewart. Seely remained a member of the CID, and it is unclear whether or when he might have been restored to the Cabinet had war not soon broken out.

First World War

Following the outbreak of war in August 1914, Seely was recalled to active duty as a special-service officer. Seely served for near the entirety of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, with few breaks, leaving London on 11 August 1914 to take up a post on Sir John French's staff. On a liaison mission between the French Fifth Army

The Fifth Army (french: Ve Armée) was a fighting force that participated in World War I. Under its commander, Louis Franchet d'Espèrey, it led the attacks which resulted in the victory at the First Battle of the Marne in 1914.

World War I C ...

and Haig's I Corps I Corps, 1st Corps, or First Corps may refer to:

France

* 1st Army Corps (France)

* I Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* I Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French A ...

(31 August 1914 – during the period when Sir John French

Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres, (28 September 1852 – 22 May 1925), known as Sir John French from 1901 to 1916, and as The Viscount French between 1916 and 1922, was a senior British Army officer. Born in Kent to ...

's retreat had opened up a gap in the Allied line), he claimed to have been almost captured in the fog, but to have bluffed his way past a German cavalry patrol by calling out (in German) that he was a member of the Great General Staff.

In October 1914, Seely was dispatched to Belgium to participate in the Siege of Antwerp. Initially acting as an observer, Seely temporarily joined the staff of Archibald Paris

Brigadier Archibald Charles Melvill Paris, (28 May 1890 – 3 March 1942) was a British Army officer.

Although he is better known for having died during the events that followed the sinking of the Dutch ship '' Rooseboom'' off Sumatra in 1942 ...

, the commander of the British Royal Naval Division

The 63rd (Royal Naval) Division was a United Kingdom infantry division of the First World War. It was originally formed as the Royal Naval Division at the outbreak of the war, from Royal Navy and Royal Marine reservists and volunteers, who wer ...

, which had been deployed to the city under orders from First Lord Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

. Once it became clear Antwerp was going to capitulate to the Germans, Seely assisted with the evacuation of the Royal Naval Division.

On 28 January 1915, Seely was given command of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade

The Canadian Cavalry Brigade was raised in December 1914, under its first commanding officer Brigadier-General J.E.B. Seely. It was originally composed of two Canadian and one British regiments and an attached artillery battery. The Canadian u ...

, with the temporary rank of brigadier-general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

and the substantive rank of colonel. He was mentioned in despatches five times, further enhancing his reputation for bravery. He was known as "the Luckiest Man in the Army" and was the subject of many apocryphal stories, such as that he recommended his soldier servant for a Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

for having stood never less than twenty yards ''behind'' him during an engagement.

On 1 January 1916, he was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

(CB). During the advance to the Hindenburg Line in spring 1917, Seely, whose brigade was attached to Fourth Army, commandeered infantry from XV Corps 15th Corps, Fifteenth Corps, or XV Corps may refer to:

*XV Corps (British India)

* XV Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army prior to and during World War I

* 15th Army Corps (Russian Empire), a unit in World War I

*XV Royal Bav ...

to form an ''ad hoc'' combat group to capture Équancourt. General du Cane's anger was assuaged – Seely later claimed – by the arrival of congratulations from Field Marshal Haig. He was appointed a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

(CMG) on 1 January 1918.

During the German Spring Offensive Seely, back from London, called on Percy Beddington, a senior staff officer of the Fifth Army, at around 2am on 24 March 1918, to inform him of the gossip in London that Fifth Army had been routed. Beddington, who had only managed to get to sleep an hour previously, for the first time since the morning of 21 March, on a camp bed in his office, recorded that he "lost (his) temper, cursed him up hill and down dale for daring to wake (him) with such drivel." Seely himself later admitted that it suddenly seemed unimportant a few days later when he was commanding the CCB in action, but it mattered a great deal in the next few days when Gough was sacked from command of the Army as a scapegoat.

After being gassed in 1918, he returned to England, and was relieved of command of the brigade on 20 May 1918. He was angry about the move.

Seely had remained an MP throughout his military service in the First World War, and as a member of the Liberal faction which supported Lloyd George's coalition government, he was appointed

During the German Spring Offensive Seely, back from London, called on Percy Beddington, a senior staff officer of the Fifth Army, at around 2am on 24 March 1918, to inform him of the gossip in London that Fifth Army had been routed. Beddington, who had only managed to get to sleep an hour previously, for the first time since the morning of 21 March, on a camp bed in his office, recorded that he "lost (his) temper, cursed him up hill and down dale for daring to wake (him) with such drivel." Seely himself later admitted that it suddenly seemed unimportant a few days later when he was commanding the CCB in action, but it mattered a great deal in the next few days when Gough was sacked from command of the Army as a scapegoat.

After being gassed in 1918, he returned to England, and was relieved of command of the brigade on 20 May 1918. He was angry about the move.

Seely had remained an MP throughout his military service in the First World War, and as a member of the Liberal faction which supported Lloyd George's coalition government, he was appointed Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Munitions

The Minister of Munitions was a British government position created during the First World War to oversee and co-ordinate the production and distribution of munitions for the war effort. The position was created in response to the Shell Crisis of ...

on 10 July 1918, serving under Churchill (then Minister of Munitions

The Minister of Munitions was a British government position created during the First World War to oversee and co-ordinate the production and distribution of munitions for the war effort. The position was created in response to the Shell Crisis of ...

).

He was the only member of the government, besides Churchill, to see active service in the war, and was promoted to the temporary rank of major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

on 13 July. Belgium appointed him a Commander of the Order of the Crown, and France both appointed Seely a Commander of the Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

and awarded him the Croix de guerre

The ''Croix de Guerre'' (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awa ...

.

Later career

Seely relinquished his temporary rank of major-general on 14 January 1919. He was appointedUnder-Secretary of State for Air

The Under-Secretary of State for Air was a junior ministerial post in the United Kingdom Government, supporting the Secretary of State for Air in his role of managing the Royal Air Force. It was established on 10 January 1919, replacing the previou ...

and President of the Air Council in 1919, again under Winston Churchill (Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

). However, he resigned both posts at the end of 1919 after the Government refused to create a Secretary of State for Air

The Secretary of State for Air was a Secretary of State (United Kingdom), secretary of state position in the British government, which existed from 1919 to 1964. The person holding this position was in charge of the Air Ministry. The Secretar ...

(as it later did). In June 1920, he was one of three candidates for the post of Governor-General of Australia

The governor-general of Australia is the representative of the monarch, currently King Charles III, in Australia.Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

, along with Lord Forster

Henry William Forster, 1st Baron Forster, (31 January 1866 – 15 January 1936) was a British politician who served as the List of Governors-General of Australia, seventh Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1920 to 1925. He had previ ...

and Lord Donoughmore

Earl of Donoughmore is a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It is associated with the Hely-Hutchinson family. Paternally of Gaelic Irish descent with the original name of ''Ó hÉalaighthe'', their ancestors had long lived in the County Cork area ...

.

Like many Lloyd George Liberals, Seely lost his seat at Ilkeston at the November 1922 General Election. He retired from the army on 25 August 1923, with the honorary rank of major-general. Seely was also a Colonel of the Territorial Army, an Honorary Colonel of 72nd (Hampshire), an Honorary Air Commander Auxiliary Air Force.

Seely returned to Parliament as a member of the reunited Liberal Party for the Isle of Wight at the December 1923 General Election, which saw a hung Parliament

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing coalition (also known as an alliance or bloc) has an absolute majority of legisl ...

in which the Liberals supported the first Labour Government under Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

. In May 1924, however, Churchill (then out of Parliament, and who had recently left the Liberal Party to become an independent "Constitutionalist", prior to rejoining the Conservatives after his return to the Commons in 1924) listed Seely in a letter to Conservative leader Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

as one of his group of Liberal MPs who would vote against the Labour government, and a month later mentioned Seely as a likely Liberal Conservative. Indeed, according to historian Chris Wrigley, Seely's political trajectory was similar to that of Churchill's (i.e. a Conservative in 1900, joining the Liberals a few years later, then becoming a Conservative again in the 1920s). Seely lost his seat again at the 1924 General Election, at which the Liberals suffered heavy losses. Seely vehemently opposed the General Strike of 1926

The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom was a general strike that lasted nine days, from 4 to 12 May 1926. It was called by the General Council of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British governmen ...

.

He was made Chairman of the National Savings Committee in 1926, a post he served in until 1943, the same year he became vice-president until his death. During this time he was asked by the Government to conduct the publicity in regard to the conversion of the 5% war loan. According to ''The Times'', "in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

the activities of the National Savings Committee were largely extended and became a vital part of the national war effort." He continued to have an influential role in domestic politics.

Seely was granted the Freedom of the City of Portsmouth in 1927.

Appeasement

On 21 June 1933, Seely was raised to the peerage as Baron Mottistone, of Mottistone in theCounty of Southampton

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire is ...

.

In 1933, Lord Mottistone visited Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

in his capacity as Chairman of the Air League, as a guest of Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

. In 1935, he visited Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

again in his boat "Mayflower". In May 1935, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

made a well publicised speech in which he proclaimed that German rearmament offered no threat to world peace. That month, Lord Mottistone told the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

that "we ought to assume that it is genuine and sincere...I have had many interviews with Herr Hitler. I think the noble Lord and all the people who have really met this remarkable man will agree with me on one thing, however much we may disagree about other things—that he is absolutely truthful, sincere, and unselfish".

His book, "Mayflower seeks the Truth", which according to the ODNB was "full of Nazi propaganda", was published in Germany in 1937. Plans for a British edition were shelved in 1938 as tensions mounted over Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. As late as June 1939 (after Hitler had broken the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

and occupied Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

), Lord Mottistone proclaimed in the House of Lords: "I am an unrepentant believer in...the policy of appeasement". However, in 1941, he wrote an article in ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, whi ...

'' and the ''Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after be ...

'' denouncing the brutality of "Hitlerism".

Other posts

Seely was also Vice-President of theRNLI

The Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) is the largest charity that saves lives at sea around the coasts of the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, the Channel Islands, and the Isle of Man, as well as on some inland waterways. It i ...

. He was a keen sailor and for much of his life was coxswain

The coxswain ( , or ) is the person in charge of a boat, particularly its navigation and steering. The etymology of the word gives a literal meaning of "boat servant" since it comes from ''cock'', referring to the cockboat, a type of ship's boat ...

of the Brook Lifeboat.

Seely served as Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire

This is a list of people who have served as Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire. Since 1688, all the Lords Lieutenant have also been Custos Rotulorum of Hampshire. From 1889 until 1959, the administrative county was named the County of Southampton.

*Wi ...

from 1918 to 1947.

He was also a Justice of the Peace (JP) for Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

and the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

, the first Chairman of Wembley Stadium

Wembley Stadium (branded as Wembley Stadium connected by EE for sponsorship reasons) is a football stadium in Wembley, London. It opened in 2007 on the site of the Wembley Stadium (1923), original Wembley Stadium, which was demolished from 200 ...

, and a director of Thomas Cook

Thomas Cook (22 November 1808 – 18 July 1892) was an English businessman. He is best known for founding the travel agency Thomas Cook & Son. He was also one of the initial developers of the "package tour" including travel, accommodation ...

.

Lord Mottistone died in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

aged 79. His will was valued for probate at £9,212 12s 4d (not including settled land

The Settled Land Acts were a series of English land law enactments concerning the limits of creating a settlement, a conveyancing device used by a property owner who wants to ensure that provision of future generations of his family.

Two main t ...

- land tied up in family trusts so that no individual has full control over it - worth £5,500). These equate respectively to around £300,000 and £200,000 at 2016 prices.

Legacy

Seely was a popular figure in the House of Commons. In later life, in a play on his title, his self-promotion earned him the nickname "Lord Modest One". He was described as a brave man, but it was also said unkindly of him that if he had had more brains he would have been half-witted. ''The Times'' called him a "Gallant Figure in War and Politics" andLord Birkenhead

Earl of Birkenhead was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1922 for the noted lawyer and Conservative politician F. E. Smith, 1st Viscount Birkenhead. He was Solicitor-General in 1915, Attorney-General from 1915 to ...

wrote, "In fields of great and critical danger he has constantly over a long period of years displayed a cool valour which everybody in the world who knows the facts freely recognizes." Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated o ...

Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general and military theorist who served as the Supreme Allied Commander during the First World War. An aggressive, even reckless commander at the First Marne, Flanders and Art ...

, Supreme Commander of the Allied Armies in the final year of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, gave him a cigarette case inscribed, ''Au Ministre de 1912: au Vaillant de la Grande Guerre.''

A screen was erected in St. Peter and St. Paul's Church in Mottistone

Mottistone is a village on the Isle of Wight, located in the popular tourist area the Back of the Wight.http://www.backofthewight.net It is located 8 Miles southwest of Newport in the southwest of the island, and is home to the National Trus ...

in his memory.

Marriages and descendants

Seely married Emily Florence, daughter of Colonel Sir Henry George Louis Crichton, on 9 July 1895. They had three sons and four daughters. She died in August 1913. His eldest son and heir, 2Lt Frank Reginald Seely, was killed in action with theRoyal Hampshire Regiment

The Hampshire Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, created as part of the Childers Reforms in 1881 by the amalgamation of the 37th (North Hampshire) Regiment of Foot and the 67th (South Hampshire) Regiment of Foot. The reg ...

at the Battle of Arras on 13 April 1917.

He married for the second time, to Evelyn Izmé Murray, JP (born 1886, died 11 Aug 1976) on 31 July 1917. She was the widow of his friend George Crosfield Norris Nicholson and daughter of Montolieu Oliphant-Murray, 1st Viscount Elibank. They had one son (she already had a son

''A Son'', also known as ''Bik Eneich: Un fils'' (a combination of the original Arabic and French titles: ar, بيك نعيش, Byk n'eysh; french: Un fils) is a 2019 film directed by Mehdi Barsaoui in his feature film debut and co-produced betwee ...

from her previous marriage).

Seely's heir John Seely (1899–1963) was an architect whose work, with Paul Edward Paget

Paul Edward Paget CVO (24 January 1901 – 13 August 1985) was the son of Henry Luke Paget, Bishop of Chester

The Bishop of Chester is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chester in the Province of York.

The diocese exten ...

in the partnership of Seely & Paget

Seely & Paget was the architectural partnership of John Seely, 2nd Baron Mottistone (1899–1963) and Paul Edward Paget (1901–1985).

Their work included the construction of Eltham Palace in the Art Deco style, and the post-World War II restora ...

, included the interior of Eltham Palace

Eltham Palace is a large house at Eltham ( ) in southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich. The house consists of the medieval great hall of a former royal residence, to which an Art Deco extension was added in the 1930s. ...

in the Art Deco style, and the post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

restoration of a number of bomb-damaged buildings, such as the London Charterhouse

The London Charterhouse is a historic complex of buildings in Farringdon, London, dating back to the 14th century. It occupies land to the north of Charterhouse Square, and lies within the London Borough of Islington. It was originally built ( ...

and the church of St John Clerkenwell

St John Clerkenwell is a former parish church in Clerkenwell, London, its original priory church site retains a crypt and has been given over to the London chapel of the modern Order of Saint John (chartered 1888), Order of St John. It is a squar ...

.

Seely's son from his second marriage, David Peter Seely, 4th Baron Mottistone (1920–2011), was the last Governor of the Isle of Wight

Below is a list of those who have held the office of Governor of the Isle of Wight in England. Lord Mottistone was the last lord lieutenant to hold the title governor, from 1992 to 1995; since then there has been no governor appointed.

Governor ...

; he was baptised with Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

and the then Prince of Wales (subsequently Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire and Emperor of India from 20 January 19 ...

and then later the Duke of Windsor) as his godparents

Seely's grandson Brough Scott

John Brough Scott, MBE (born 12 December 1942) is a British horse racing journalist, radio and television presenter, and former jockey. He is also the grandson and biographer of the noted Great War soldier "Galloper Jack" Seely.

Scott was edu ...

, who presented horseracing television programmes, wrote a biography of Seely, ''Galloper Jack'' (2003).

Seely was a maternal great-great-grandfather of theatre director Sophie Hunter

Sophie Irene Hunter (born 16 March 1978) is an English theatre director, playwright and former actress and singer. She made her directorial debut in 2007 co-directing the experimental play ''The Terrific Electric'' at the Barbican Pit after her ...

.

The present Conservative MP for the Isle of Wight, Bob Seely

Robert William Henry Seely (born 1 June 1966) is a British Conservative Party politician who has served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for the Isle of Wight since June 2017. He was re-elected at the general election in December 2019 with an ...

, is his great-great nephew.

In popular culture

According to theSir Alfred Munnings Art Museum

Castle House in Dedham, Essex, England was the home of Sir Alfred Munnings from 1919 till his death in 1959. Architecturally the building contains a mixture of Tudor and Georgian elements.

Shortly after his death his widow established The Viol ...

(Alfred Munnings

Sir Alfred James Munnings, (8 October 1878 – 17 July 1959) was known as one of England's finest painters of horses, and as an outspoken critic of Modernism. Engaged by Lord Beaverbrook's Canadian War Memorials Fund, he earned several prest ...

was a former president of the Royal Academy of Arts

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its purpo ...

and famous horse painter) "Without doubt his most important painting was that of ''General J. E. B. Seely (later Lord Mottistone) on his charger Warrior

A warrior is a person specializing in combat or warfare, especially within the context of a tribal or clan-based warrior culture society that recognizes a separate warrior aristocracies, class, or caste.

History

Warriors seem to have been p ...

'' which led to his commission to paint the Earl of Athlone

The title of Earl of Athlone has been created three times.

History

It was created first in the Peerage of Ireland in 1692 by William III of England, King William III for General Godard van Reede, 1st Earl of Athlone, Baron van Reede, Lord of ...

, brother of Queen Mary."

Jack Seely was featured in the HBO

Home Box Office (HBO) is an American premium television network, which is the flagship property of namesake parent subsidiary Home Box Office, Inc., itself a unit owned by Warner Bros. Discovery. The overall Home Box Office business unit is ba ...

film '' Into the Storm'' in 2009. At the end of the film Churchill reads a sympathetic post-election note from his old friend Jack Seely: "I feel our world slipping away." Churchill thinks back: "I met him in South Africa, riding across the veldt. He was Col. Seely then. I saw him at the head of a column of British cavalry, riding twenty yards in front, on a black horse. I thought of him as the very symbol of British Imperial power." The Testimony Films 2012 documentary ''War Horse: The Real Story'' contained extensive discussion of the First World War service of Seely and his widely revered horse, Warrior

A warrior is a person specializing in combat or warfare, especially within the context of a tribal or clan-based warrior culture society that recognizes a separate warrior aristocracies, class, or caste.

History

Warriors seem to have been p ...

. Warrior was adopted as his formation's mascot and had a reputation for bravery under fire. Warrior survived the war, dying in 1941 at the age of 33. In September 2014, the horse was posthumously awarded an honorary PDSA Dickin Medal for bravery.

Writings

*''Adventure'' (1930) - featuring an introduction by Lord Birkenhead, praising his skill as a raconteur. *''Fear and Be Slain: Adventures by land, sea and air'' (1931) *''Launch! A Life-Boat Book'' (1932) *''For Ever England'' (1932) *''My Horse Warrior'' (1934) – a biography of his charger *''The Paths of Happiness'' (1938) Seely's books shed light on his personality but are not always factually reliable.Holmes 2004, p385Electoral record

References

Sources

*Burke's Peerage and Baronetage 107th Edition Volume III

*Dictionary of National Biography, 1941–1950.

richardlangworth.com

* * * * , essay on Seely written by Roger Fulford, revised by Mark Pottle * *

External links

J.E.B. Seely

at National Registry of Archives

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography – Seely, John Edward Bernard

(requires login) * *

– Extended story of the Canadian cavalry horse {{DEFAULTSORT:Mottistone, J. E. B. Seely, 1st Baron 1868 births 1947 deaths Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge British Army cavalry generals of World War I British Army personnel of the Second Boer War British Secretaries of State Seeley, J.E.B Deputy Lieutenants of the Isle of Wight Seely, J.E.B Lord-Lieutenants of Hampshire Members of the Inner Temple Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom People educated at Harrow School Secretaries of State for War (UK) Seely, J. E. B. Seely, J. E. B. Seely, J. E. B. Seely, J. E. B. Seely, J. E. B. Seely, J. E. B. UK MPs who were granted peerages Seely, J. E. B. Imperial Yeomanry officers Members of Parliament for the Isle of Wight Hampshire Yeomanry officers Barons in the Peerage of the United Kingdom Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George Companions of the Order of the Bath Commandeurs of the Légion d'honneur Recipients of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) Deputy Lieutenants of Hampshire J.E.B. Military personnel from Derbyshire Barons created by George V British Army major generals