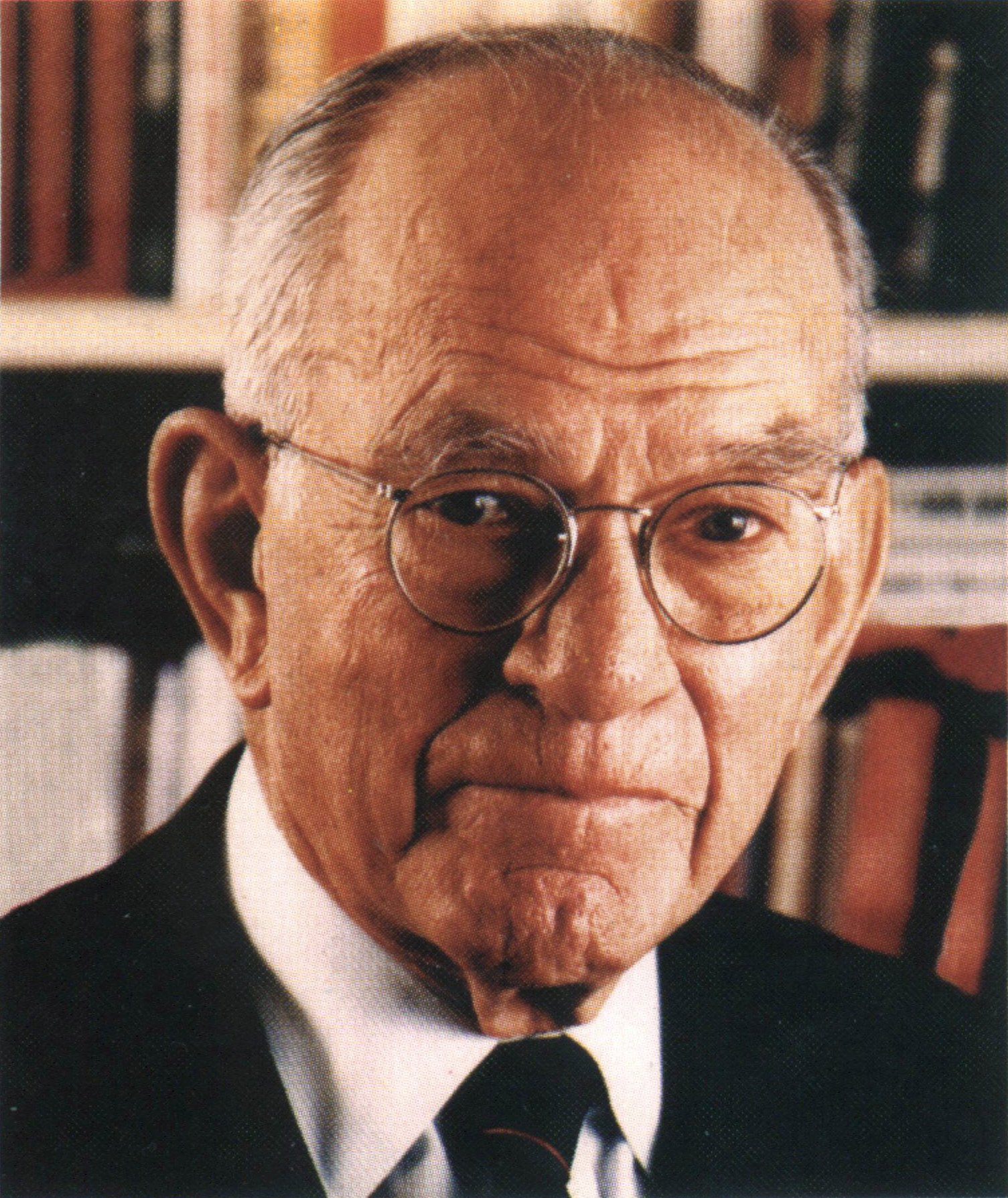

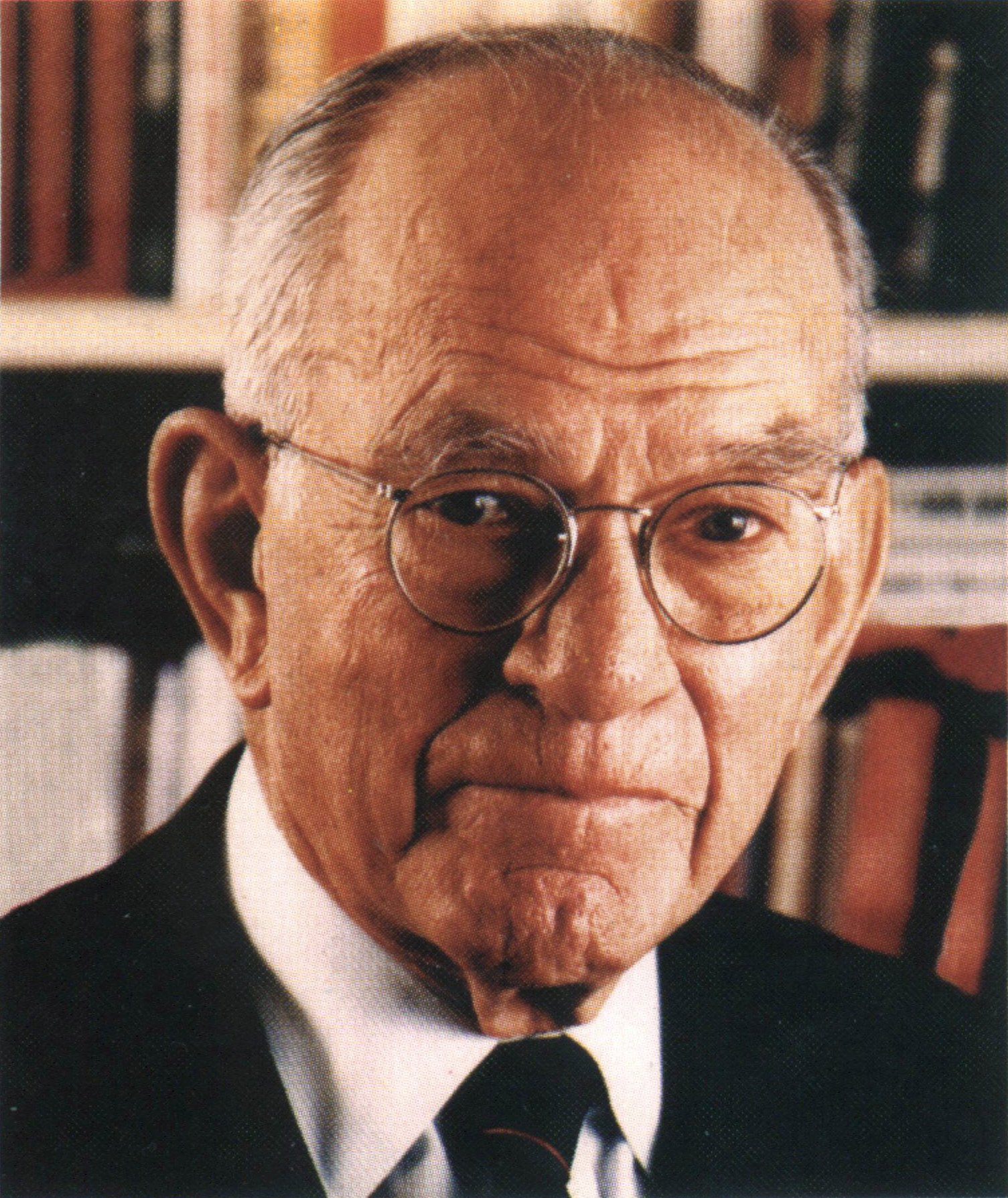

James William Fulbright (April 9, 1905 – February 9, 1995) was an American

politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

, academic, and statesman who represented

Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

in the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

from 1945 until his resignation in 1974. , Fulbright is the longest serving chairman in the history of the

United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid pr ...

. He is best known for his strong

multilateralist

In international relations, multilateralism refers to an alliance of multiple countries pursuing a common goal.

Definitions

Multilateralism, in the form of membership in international institutions, serves to bind powerful nations, discourage u ...

positions on international issues, opposition to American involvement in the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, and the creation of the international fellowship program bearing his name, the

Fulbright Program

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is one of several United States Cultural Exchange Programs with the goal of improving intercultural relations, cultural diplomacy, and intercultural competence between the people of ...

.

Fulbright was an admirer of

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

and an avowed

Anglophile

An Anglophile is a person who admires or loves England, its people, its culture, its language, and/or its various accents.

Etymology

The word is derived from the Latin word ''Anglii'' and Ancient Greek word φίλος ''philos'', meaning "frien ...

. He was an early advocate for American entry into

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

and aid to

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

, first as a college professor and then as an elected member of the

U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

, where he authored the Fulbright Resolution expressing support for international peacekeeping initiatives and American entry into the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

.

After joining the Senate, Fulbright expressed support for

Europeanism

European values are the norms and values that Europeans are said to have in common, and which transcend national or state identity. In addition to helping promote European integration, this doctrine also provides the basis for analyses that charac ...

and the formation of

a federal European union. He envisioned the Cold War as a struggle between nations—the United States and

imperialist Russia—rather than ideologies. He therefore dismissed Asia as a peripheral theater of the conflict, focusing on

containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''cordon sanitaire'', which was ...

of

Soviet expansion into Central and Eastern Europe. He also stressed the possibility of

nuclear annihilation

A nuclear holocaust, also known as a nuclear apocalypse, nuclear Armageddon, or atomic holocaust, is a theoretical scenario where the mass detonation of nuclear weapons causes globally widespread destruction and radioactive fallout. Such a scenar ...

, preferring political solutions over military solutions to Soviet aggression. After the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

, his position moderated further to one of

détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduc ...

.

His political stances and powerful position as Chairman of the

Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid pro ...

made him one of the most visible critics of American involvement in the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

. Although he was persuaded by President Lyndon Johnson to sponsor the

Gulf of Tonkin resolution

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution or the Southeast Asia Resolution, , was a joint resolution that the United States Congress passed on August 7, 1964, in response to the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

It is of historic significance because it gave U.S. p ...

in 1964, his relationship with the President soured after the 1965 U.S. bombing of Pleiku and Fulbright’s opposition to the war in Vietnam took root. Beginning in 1966, he chaired

high-profile hearings investigating the conduct and progress of the war, which may have influenced the eventual American withdrawal.

On domestic issues, Fulbright was a

Southern Democrat

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally much more conservative than Northern Democrats with ...

and signatory to the

Southern Manifesto

The Declaration of Constitutional Principles (known informally as the Southern Manifesto) was a document written in February and March 1956, during the 84th United States Congress, in opposition to racial integration of public places. The manife ...

. Fulbright also opposed the anti-Communist crusades of

Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarthy became the most visi ...

and the similar investigations by the

House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

.

Early life, family and education

Fulbright was born on April 9, 1905, in

Sumner, Missouri

Sumner is a city in Chariton County, Missouri, United States. The population was 78 at the 2020 census. It was named in honor of U.S. Senator Charles Sumner.

History

The area along the Grand River in the northwest corner of present-day Chariton ...

, the son of Jay and

Roberta

''Roberta'' is a musical from 1933 with music by Jerome Kern, and lyrics and book by Otto Harbach. The musical is based on the novel ''Gowns by Roberta'' by Alice Duer Miller. It features the songs " Yesterdays", "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes", "Let ...

( Waugh) Fulbright. In 1906, the Fulbright family moved to

Fayetteville, Arkansas

Fayetteville () is the second-largest city in Arkansas, the county seat of Washington County, and the biggest city in Northwest Arkansas. The city is on the outskirts of the Boston Mountains, deep within the Ozarks. Known as Washington until ...

. His mother was a businesswoman, who consolidated her husband's business enterprises and became an influential newspaper publisher, editor, and journalist.

Fulbright's parents enrolled him in the

University of Arkansas

The University of Arkansas (U of A, UArk, or UA) is a public land-grant research university in Fayetteville, Arkansas. It is the flagship campus of the University of Arkansas System and the largest university in the state. Founded as Arkansas ...

's

College of Education

In the United States and Canada, a school of education (or college of education; ed school) is a division within a university that is devoted to scholarship in the field of education, which is an interdisciplinary branch of the social sciences en ...

's experimental grammar and secondary school.

University of Arkansas

Fulbright earned a

history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

degree from the University of Arkansas in 1925, where he became a member of the

Sigma Chi

Sigma Chi () International Fraternity is one of the largest North American fraternal literary societies. The fraternity has 244 active (undergraduate) chapters and 152 alumni chapters across the United States and Canada and has initiated more tha ...

fraternity. He was elected president of the student body and a star four-year player for the

Arkansas Razorbacks football

The Arkansas Razorbacks football program represents the University of Arkansas in the sport of American football. The Razorbacks compete in the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) and the Weste ...

team from 1921 to 1924.

Oxford University

Fulbright later studied at

Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, where he was a

Rhodes Scholar

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world' ...

at

Pembroke College and graduated in 1928. Fulbright's time at Oxford made him into a lifelong Anglophile, and he always had warm memories of Oxford.

At Oxford, he played on the rugby and lacrosse teams, and every summer, Fulbright decamped for France ostensibly to improve his French but really just to enjoy life in France.

Fulbright credited his time at Oxford with broadening his horizons. In particular, he credited his professor and friend

R. B. McCallum

Ronald Buchanan McCallum (28 August 1898 in Paisley, Renfrewshire – 18 May 1973 in Letcombe Regis, Berkshire) was a British historian. He was a fellow (and later Master) of Pembroke College, Oxford, where he taught modern history and politics a ...

's "one world" philosophy of the world as an interlinked entity, where developments in one part would always impact on the other parts. McCallum was a great admirer of

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, a supporter of the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, and a believer that multinational organizations were the best way to ensure global peace. Fulbright remained close to McCallum for the rest of his life and regularly exchanged letters with his mentor until McCallum's death in 1973.

Fulbright received his law degree from The

George Washington University Law School

The George Washington University Law School (GW Law) is the law school of George Washington University, in Washington, D.C. Established in 1865, GW Law is the oldest top law school in the national capital. GW Law offers the largest range of cou ...

in 1934, was admitted to the bar in

Washington, DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan ...

, and became an attorney in the

Antitrust Division

The United States Department of Justice Antitrust Division is a division of the U.S. Department of Justice that enforces U.S. antitrust law. It has exclusive jurisdiction over U.S. federal criminal antitrust prosecutions. It also has jurisdic ...

of the

U.S. Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United State ...

.

Legal and academic career

Fulbright was a lecturer in law at the

University of Arkansas

The University of Arkansas (U of A, UArk, or UA) is a public land-grant research university in Fayetteville, Arkansas. It is the flagship campus of the University of Arkansas System and the largest university in the state. Founded as Arkansas ...

from 1936 to 1939. He was appointed president of the school in 1939, making him the youngest university president in the country. He held that post until 1941. The School of Arts and Sciences at the

University of Arkansas

The University of Arkansas (U of A, UArk, or UA) is a public land-grant research university in Fayetteville, Arkansas. It is the flagship campus of the University of Arkansas System and the largest university in the state. Founded as Arkansas ...

is named in his honor, and he was elected there into

Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal a ...

. He was a member of the Founding Council of the

Rothermere American Institute

The Rothermere American Institute is a department of the University of Oxford dedicated to the interdisciplinary and comparative study of the United States of America and its place in the world. Named after the Harmsworth family, Viscounts Roth ...

,

University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

. In September 1939, Fulbright, as president of the University of Arkansas, issued a public declaration declaring his sympathy with the Allied cause and urged the United States to maintain a pro-Allied neutrality. In the summer of 1940, Fulbright went a step further and declared it was in America's "vital interest" to enter the war on the Allied side and warned that a victory by Nazi Germany would make the world a much darker place. The same year, Fulbright joined the

Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies The Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies (CDAAA) was an American mass movement, political action group formed in May 1940. Also known as the White Committee, its leader until January 1941 was William Allen White. Other important members ...

.

In June 1941, Fulbright was suddenly fired from the University of Arkansas by the Governor,

Homer Martin Adkins

Homer Martin Adkins (October 15, 1890 – February 26, 1964) was an American businessman and Democratic politician who served as the 32nd governor of the U.S. state of Arkansas. Adkins is remembered as a skilled retail politician and a strong st ...

. He learned that the reason for his sacking was that Adkins had been offended that a Northwest Arkansas newspaper owned by his mother Roberta Fulbright had supported the governor's opponent in the 1940 Democratic primary, and that was the governor's revenge. Upset at the way that the governor's caprice had ended his academic career, Fulbright became interested in politics.

U.S. House of Representatives

Fulbright was elected to the

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

as a Democrat in 1942, where he served one term. During this period, he became a member of the

House Foreign Affairs Committee

The United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs, also known as the House Foreign Affairs Committee, is a standing committee of the U.S. House of Representatives with jurisdiction over bills and investigations concerning the foreign affairs ...

. During World War II, there was much debate about the best way to win the peace after the Allies presumably won the war, with many urging the United States to reject isolationism. The House adopted the Fulbright Resolution, which supported international peacekeeping initiatives and encouraged the United States to participate in what became the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

in September 1943. That brought Fulbright to national attention.

In 1943, a confidential analysis by

Isaiah Berlin

Sir Isaiah Berlin (6 June 1909 – 5 November 1997) was a Russian-British social and political theorist, philosopher, and historian of ideas. Although he became increasingly averse to writing for publication, his improvised lectures and talks ...

of the House and Senate foreign relations committees for the British

Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

identified Fulbright as "a distinguished new-comer to the House." It continued:

U.S. Senator (1945–74)

Fulbright's career in the Senate was somewhat stunted, his tangible influence never matching his public luminescence. For all his seniority and powerful committee posts, he was not considered part of the Senate's inner circle of friends and power brokers. He seemed to prefer it that way: the man who

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

had called an "overeducated SOB" was, in the words of

Clayton Fritchey

Clayton Fritchey (June 30, 1904 — January 23, 2001) was an American journalist who spent many years in public service.

Early life

Clayton Fritchey was born in 1904 in Bellefontaine, Ohio. At the age of 2 he moved to Baltimore.

Career

His repor ...

, "an individualist and a thinker," whose "intellectualism alone alienates him from the Club" of the Senate.

1944 election

He was elected to the Senate in 1944 and unseated incumbent

Hattie Carraway

Hattie Ophelia Wyatt Caraway (February 1, 1878 – December 21, 1950) was an American politician who became the first woman elected to serve a full term as a United States Senator. Caraway represented Arkansas. She was the first woman to preside ...

, the first woman ever elected to the U.S. Senate. He served five six-year terms. In his first general election to the Senate, Fulbright defeated the

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Victor Wade of

Batesville by 85.1% to 14.9%.

Establishment of Fulbright program

He promoted the passage of legislation establishing the

Fulbright Program

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is one of several United States Cultural Exchange Programs with the goal of improving intercultural relations, cultural diplomacy, and intercultural competence between the people of ...

in 1946 of educational grants (Fulbright Fellowships and Fulbright Scholarships), sponsored by the

Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs

The Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA) of the United States Department of State fosters mutual understanding between the people of the United States and the people of other countries around the world. It is responsible for the Un ...

of the

United States Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other n ...

, governments in other countries, and the private sector. The program was established to increase mutual understanding between the peoples of the United States and other countries through the exchange of persons, knowledge, and skills. It is considered one of the most prestigious award programs and operates in 155 countries.

Truman administration and Korean War

In November 1946, immediately following the midterm elections in which Democrats lost control of both houses of Congress amidst President

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

's plummeting popularity in the polls, Fulbright suggested the President appoint Senator

Arthur Vandenberg

Arthur Hendrick Vandenberg Sr. (March 22, 1884April 18, 1951) was an American politician who served as a United States senator from Michigan from 1928 to 1951. A member of the Republican Party, he participated in the creation of the United Nati ...

(R-

MI) as his

Secretary of State and resign, making Vandenberg president. Truman responded by saying he did not care what Senator "Halfbright" said.

In 1947, Fulbright supported the Truman Doctrine and voted for American aid to Greece. Subsequently, he voted for the

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

and to join

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

. Fulbright was very supportive of the plans for a federation in Western Europe. Fulbright supported the 1950 plan written by

Jean Monnet

Jean Omer Marie Gabriel Monnet (; 9 November 1888 – 16 March 1979) was a French civil servant, entrepreneur, diplomat, financier, administrator, and political visionary. An influential supporter of European unity, he is considered one of the ...

and presented by French Foreign Minister

Robert Schuman

Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Robert Schuman (; 29 June 18864 September 1963) was a Luxembourg-born French statesman. Schuman was a Christian Democrat (Popular Republican Movement) political thinker and activist. Twice Prime Minister of France, a ref ...

for a

European Coal and Steel Community

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was a European organization created after World War II to regulate the coal and steel industries. It was formally established in 1951 by the Treaty of Paris, signed by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembo ...

, the earliest predecessor to the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

.

In 1949, Fulbright became a member of the

Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid pro ...

.

After China's entry into the

Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

in October 1950, Fulbright warned against American escalation. On January 18, 1951, he dismissed Korea as a peripheral interest not worth the risk of

World War III

World War III or the Third World War, often abbreviated as WWIII or WW3, are names given to a hypothetical World war, worldwide large-scale military conflict subsequent to World War I and World War II. The term has been in use ...

and condemned plans to attack China as reckless and dangerous. In the same speech, he argued that the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, not China, was the real enemy and that Korea was a distraction from Europe, which he considered to be far more important.

When President Truman fired General

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

for insubordination in April 1951, Fulbright came to Truman's defense. When MacArthur appeared before the

Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid pro ...

at the invitation of Republican senators, Fulbright embraced his role of Truman's defender. When MacArthur argued communism was an inherent mortal danger to the United States, Fulbright countered, "I had not myself thought of our enemy as being Communism; I thought of it as primarily being

imperialist Russia."

Eisenhower administration and conflict with Joe McCarthy

Fulbright was an early opponent of Senator

Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarthy became the most visi ...

of Wisconsin, an ardent albeit reckless anti-communist. Fulbright viewed McCarthy as an anti-intellectual, demagogue, and a major threat to American democracy and world peace. Fulbright was the only senator to vote against an appropriation for the

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

The Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (PSI), stood up in March 1941 as the "Truman Committee," is the oldest subcommittee of the United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs (formerly the Committee on Governme ...

in 1954, which was chaired by McCarthy.

After Republicans gained a Senate majority in the 1952 elections, McCarthy became chairman of the Senate Committee on Government Operations. Fulbright was initially resistant to calls, like that of his friend

William Benton of Connecticut, to openly oppose McCarthy. Though sympathetic toward Benton, who was among those Senators defeated in 1952 by anti-communist sentiment, Fulbright followed Senate Minority Leader

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

's lead in refraining from criticism. Fulbright was alarmed by McCarthy's attack on the

Voice of America

Voice of America (VOA or VoA) is the state-owned news network and international radio broadcaster of the United States of America. It is the largest and oldest U.S.-funded international broadcaster. VOA produces digital, TV, and radio content ...

(VOA) and the

United States Information Agency

The United States Information Agency (USIA), which operated from 1953 to 1999, was a United States agency devoted to "public diplomacy". In 1999, prior to the reorganization of intelligence agencies by President George W. Bush, President Bill C ...

, the latter agency then supervising educational exchange programs.

Fulbright broke from Johnson's party line in summer 1953, following the State Department withdrawal of a fellowship for a student whose wife was suspected of communist affiliation and a Senate Appropriations Committee hearing which appeared to put the Fulbright Program at stake. In this hearing, McCarthy aggressively questioned Fulbright, whom he frequently referred to as "Senator Halfbright", over the composition of the board clearing students for funding and on a policy that bars communists and their sympathizers from receiving appointments as lecturers and professors. Fulbright stated that he had no such influence over the board. After McCarthy insisted to be authorized to release statements of some Fulbright Program students both praising the communist form of government and condemning American values, Fulbright countered that he was willing to submit thousands of names of students who had praised the US and its way of government in their statements. The encounter was the last time McCarthy made a public assault on the program. The leading historian and original Fulbright Program board member Walter Johnson credited Fulbright with preventing the program from being ended by

McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origin ...

.

1956 re-election campaign

In 1956, Fulbright campaigned across the country for

Adlai Stevenson II

Adlai Ewing Stevenson II (; February 5, 1900 – July 14, 1965) was an American politician and diplomat who was twice the Democratic nominee for President of the United States. He was the grandson of Adlai Stevenson I, the 23rd vice president of ...

's presidential campaign and across Arkansas for his own re-election bid. Fulbright emphasized his opposition to

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

and his support for

segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

. He also noted his support for oil companies and consistent votes for more farm aid to poultry farmers, a key Arkansas constituency. He easily defeated his Republican challenger.

Kennedy administration

Fulbright was

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

's first choice for

Secretary of State in 1961 and had the support of

Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on t ...

Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, but opponents to the choice within Kennedy's circle, led by

Harris Wofford

Harris Llewellyn Wofford Jr. (April 9, 1926 – January 21, 2019) was an American attorney, civil rights activist, and Democratic Party politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1991 to 1995. A noted advocate of na ...

, killed his chances.

Dean Rusk

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909December 20, 1994) was the United States Secretary of State from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving Secretary of State after Cordell Hull from the F ...

was chosen instead.

In April 1961, Fulbright advised Kennedy not to go forward with the planned

Bay of Pigs invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fina ...

. He said, "The Castro regime is a thorn in the flesh. But it is not a dagger at the heart." In May 1961, Fulbright denounced the

Kennedy administration

John F. Kennedy's tenure as the 35th president of the United States, began with his inauguration on January 20, 1961, and ended with his assassination on November 22, 1963. A Democrat from Massachusetts, he took office following the 1960 p ...

's system of having diplomats rotate from one position to another as an "idiot policy."

Fulbright provoked international controversy on July 30, 1961, two weeks before the erection of the

Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall (german: Berliner Mauer, ) was a guarded concrete barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and East Germany (GDR). Construction of the Berlin Wall was commenced by the government ...

, when he said in a television interview, "I don't understand why the

East Germans

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

don't just close their border, because I think they have the right to close it." His statement received a three-column spread on the front page of the

Socialist Unity Party of Germany

The Socialist Unity Party of Germany (german: Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, ; SED, ), often known in English as the East German Communist Party, was the founding and ruling party of the German Democratic Republic (GDR; East German ...

newspaper ''

Neues Deutschland

''Neues Deutschland'' (''nd''; en, New Germany, sometimes stylized in lowercase letters) is a left-wing German daily newspaper, headquartered in Berlin.

For 43 years it was the official party newspaper of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany ...

'' and condemnation in

West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

. The U.S. embassy in

Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr r ...

reported that "rarely has a statement by a prominent American official aroused so much consternation, chagrin and anger." Chancellor

Willy Brandt

Willy Brandt (; born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm; 18 December 1913 – 8 October 1992) was a German politician and statesman who was leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) from 1964 to 1987 and served as the chancellor of West Ge ...

's Press Secretary

Egon Bahr

Egon Karl-Heinz Bahr (; 18 March 1922 – 19 August 2015) was a German SPD politician.

The former journalist was the creator of the ''Ostpolitik'' promoted by West German Chancellor Willy Brandt, for whom he served as Secretary of State in ...

was quoted, "We privately called him Fulbricht." Historian William R. Smyser suggests that Fulbright's comment may have been made at President Kennedy's behest, as a signal to Soviet premier

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

that the wall would be an acceptable means of defusing the

Berlin Crisis. Kennedy did not distance himself from Fulbright's comments, despite pressure.

In August 1961, as the

Kennedy administration

John F. Kennedy's tenure as the 35th president of the United States, began with his inauguration on January 20, 1961, and ended with his assassination on November 22, 1963. A Democrat from Massachusetts, he took office following the 1960 p ...

held firm in its commitment to a five-year foreign aid program, Fulbright and

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

U.S. Representative

Thomas E. Morgan

Thomas Ellsworth Morgan (October 13, 1906 – July 31, 1995) was a Democratic member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania.

Thomas E. Morgan was born in Ellsworth, Pennsylvania; his mother was an immigrant from England and his ...

accompanied Democratic congressional leadership to their weekly White House breakfast session with Kennedy. In delivering opening statements on August 4, Fulbright spoke of the program introducing a new concept of foreign aid in the event of its passage.

Fulbright met with Kennedy during the latter's visit to

Fort Smith, Arkansas

Fort Smith is the third-largest city in Arkansas and one of the two county seats of Sebastian County. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 89,142. It is the principal city of the Fort Smith, Arkansas–Oklahoma Metropolitan Statistical Are ...

in October 1961.

After the 1962

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

, Fulbright modified his position on the Soviet Union from "containment" to

détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduc ...

. His position drew criticism from Senator

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for presiden ...

, now the leader of anti-communists in the Senate. In response to Goldwater's call for a "total victory" over communism, Fulbright argued that even "total victory" would mean hundreds of millions of deaths and an impossible, prolonged occupation of a ravaged

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

.

Chicken war

Intensive chicken farming in the United States led to a 1961–64 "chicken war" with Europe. With inexpensive imported chicken available, chicken prices fell quickly and sharply across Europe, radically affecting European chicken consumption. U.S. chicken overtook nearly half of the imported European chicken market. Europe instituted tariffs on American chicken, to the detriment of Arkansan chicken farmers.

Senator Fulbright interrupted a

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

debate on nuclear armament to protest the tariffs, going so far as to threaten cutting US troops in NATO.

The U.S. subsequently enacted a 25% tariff on imported

light trucks

Light truck or light-duty truck is a US classification for vehicles with a gross vehicle weight up to and a payload capacity up to 4,000 pounds (1,815 kg). Similar goods vehicle classes in the European Union, Canada, Australia, and New Zealan ...

, known as the

chicken tax

The Chicken Tax is a 25 percent tariff on light trucks (and originally on potato starch, dextrin, and brandy) imposed in 1964 by the United States under President Lyndon B. Johnson in response to tariffs placed by France and West Germany on impor ...

, which remains in effect as of 2010.

One of Fulbright's local staffers in Arkansas was

James McDougal

James B. McDougal (August 25, 1940 – March 8, 1998) was a native of White County, Arkansas, and his wife, Susan McDougal (the former Susan Carol Henley), were financial partners with Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton in the real estate venture ...

. While he worked for Fulbright, McDougal met the future Arkansas Governor and US President

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

and the two of them, along with their wives, began investing in various development properties, including the parcel of land along the

White River in the Ozarks that would later be the subject of an

independent counsel

The Office of Special Counsel was an office of the United States Department of Justice established by provisions in the Ethics in Government Act that expired in 1999. The provisions were replaced by Department of Justice regulation 28 CFR Part ...

investigation during Clinton's first term in office.

Johnson administration

On March 25, 1964, Fulbright delivered an address calling on the U.S. to adapt itself to a world that was both changing and complex, the address being said by Fulbright to have been meant to explore self-evident truths in the national vocabulary of the U.S. regarding the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

,

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

,

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

,

Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cos ...

, and

Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

.

In May 1964, Fulbright predicted that time would see a cessation in the misunderstanding within the relationship between

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and the United States and that

French President

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency is ...

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

was deeply admired for his achievements despite confusion that might arise in others from his rhetoric.

In 1965, Fulbright objected to President

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

's position on the

Dominican Civil War

The Dominican Civil War (), also known as the April Revolution (), took place between April 24, 1965, and September 3, 1965, in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. It started when civilian and military supporters of the overthrown democraticall ...

.

Vietnam War

Gulf of Tonkin resolution

On 4 August 1964, Defense Secretary

Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the Lis ...

accused

North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; vi, Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa), was a socialist state supported by the Soviet Union (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia that existed f ...

of attacking an American destroyer, the USS ''Maddox'' in international waters in what came to be known as the

Gulf of Tonkin incident

The Gulf of Tonkin incident ( vi, Sự kiện Vịnh Bắc Bộ) was an international confrontation that led to the United States engaging more directly in the Vietnam War. It involved both a proven confrontation on August 2, 1964, carried out b ...

. The same day, President Johnson went on national television to denounce North Vietnam for "aggression" and to announce that he had ordered retaliatory air raids on North Vietnam. In the same speech, Johnson asked Congress to a resolution to prove to North Vietnam and its ally China that United States was united "in support of freedom and in defense of peace in southeast Asia." On 5 August 1964, Fulbright arrived at the White House to meet Johnson, where Johnson asked his old friend to use all his influence to get the resolution passed by the widest possible margin. Fulbright was one of the senators whom Johnson was most anxious and keen to have support the resolution. Fulbright was too much an individualist and intellectual to belong to the "Club" of the Senate, but he was widely respected as a thinker on foreign policy and was known to be a defender of Congress's prerogatives. From Johnson's viewpoint, having him support the resolution would bring many of the waverers around to voting for the resolution, as indeed proved to be the case.

Johnson insisted quite vehemently to Fulbright that the alleged attack on the ''Maddox'' had taken place, and it was only later that Fulbright became skeptical about whether the alleged attack had really taken place. Furthermore, Johnson insisted that the resolution, which was a "functional equivalent to a declaration of war," was not intended to be used for going to war in Vietnam. In the

1964 presidential election, the Republicans had nominated Goldwater as their candidate, who ran on a platform accusing Johnson of being "soft on communism" and by contrast promised a "total victory" over communism. Johnson argued to Fulbright that the resolution was an election-year stunt that would prove to the voters that he was really "tough on communism" and so dent the appeal of Goldwater by denying him of his main avenue of attack. Besides for the internal political reason that Johnson gave for the resolution, he also gave a foreign policy reason that argued that such a resolution would intimidate North Vietnam into ceasing to try to overthrow the government of

South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam ( vi, Việt Nam Cộng hòa), was a state in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975, the period when the southern portion of Vietnam was a member of the Western Bloc during part of th ...

and so Congress passage of the resolution would make American involvement in Vietnam less likely, rather than more likely. Fulbright's longstanding friendship with Johnson made it difficult for him to go against the President, who cunningly exploited Fulbright's vulnerability, his desire to have greater influence over foreign policy. Johnson gave Fulbright the impression that he would be one of his unofficial advisers on foreign policy and that he was very interested in turning his ideas into policies if he voted for the resolution, which was a test of their friendship. Johnson also hinted that he was thinking about sacking Rusk if he won the 1964 election and would consider nominating Fulbright to be the next Secretary of State. Finally, for Fulbright in 1964, it was inconceivable that Johnson would lie to him, and Fulbright believed the resolution "was not going to be used for anything other than the Tonkin Gulf incident itself," as Johnson had told him.

On 6 August 1964, Fulbright gave a speech on the Senate floor that called for the resolution to be passed as he accused North Vietnam of "aggression" and praised Johnson for his "great restraint... in response to the provocation of a small power." He also declared his support for the

Johnson administration's "noble" Vietnam policy, which he called a policy of seeking "to establish viable, independent states in Indochina and elsewhere which will be free and secure from the combination of Communist China and Communist North Vietnam." Fulbright concluded that the policy could be accomplished via diplomatic means and, echoing Johnson's argument, argued that it was necessary to pass the resolution as a way to intimidate North Vietnam, which would presumably change its policies towards South Vietnam once Congress passed the resolution. Several senators, such as

Allen J. Ellender

Allen Joseph Ellender (September 24, 1890 – July 27, 1972) was an American politician and lawyer who was a U.S. Senator from Louisiana from 1937 until his death. He was a Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who was originally allied ...

,

Jacob Javits

Jacob Koppel Javits ( ; May 18, 1904 – March 7, 1986) was an American lawyer and politician. During his time in politics, he represented the state of New York in both houses of the United States Congress. A member of the Republican Party, he a ...

,

John Sherman Cooper

John Sherman Cooper (August 23, 1901 – February 21, 1991) was an American politician, jurist, and diplomat from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. He served three non-consecutive, partial terms in the United States Senate before being elect ...

,

Daniel Brewster

Daniel Baugh Brewster Jr. (November 23, 1923 – August 19, 2007) was an American politician serving as a Democratic member of the United States Senate, representing the State of Maryland from 1963 until 1969. He was also a member of the Maryla ...

,

George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American historian and South Dakota politician who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator, and the Democratic Party presidential nominee in the 1972 pres ...

, and

Gaylord Nelson

Gaylord Anton Nelson (June 4, 1916July 3, 2005) was an American politician and environmentalist from Wisconsin who served as a United States senator and governor. He was a member of the Democratic Party and the founder of Earth Day, which launche ...

, were very reluctant to vote for a resolution that would be a blank check for a war in

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

, and in a meeting, Fulbright sought to assure them by saying that passing such a resolution would make fighting a war less likely and claimed that the whole purpose of the resolution was intimidation. Nelson wanted to insert an amendment to bar the president from sending troops to fight in Vietnam unless he obtained the permission of Congress first and said that he did not like the open-ended nature of this resolution. Fulbright persuaded him not to do so by arguing the resolution was "harmless" and saying that the real purpose of the resolution was "to pull the rug out from under Goldwater." He went on to ask Nelson whether he preferred Johnson or Goldwater to win the election. Fulbright dismissed Nelson's fears of giving Johnson a blank check by saying that he had Johnson's word that "the last thing we want to do is become involved in a land war in Asia."

On August 7, 1964, a unanimous House of Representatives and all but two members of the Senate voted to approve the

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution or the Southeast Asia Resolution, , was a joint resolution that the United States Congress passed on August 7, 1964, in response to the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

It is of historic significance because it gave U.S. p ...

, which led to a dramatic escalation of the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

. Fulbright, who sponsored the resolution, would later write:

Many Senators who accepted the Gulf of Tonkin resolution without question might well not have done so had they foreseen that it would subsequently be interpreted as a sweeping Congressional endorsement for the conduct of a large-scale war in Asia.

Fulbright hearings and opposition to war

By his own admission, Fulbright knew almost nothing about

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

until he met, in 1965,

Bernard B. Fall

Bernard B. Fall (November 19, 1926 – February 21, 1967) was a prominent war correspondent, historian, political scientist, and expert on Indochina during the 1950s and 1960s. Born in Austria, he moved with his family to France as a child aft ...

, a French journalist who often wrote about Vietnam. Speaking to Fall radically changed Fulbright's thinking about Vietnam, as Fall asserted that it simply not true that

Ho Chi Minh

(: ; born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), commonly known as ('Uncle Hồ'), also known as ('President Hồ'), (' Old father of the people') and by other aliases, was a Vietnamese revolutionary and statesman. He served as Prime ...

was a Sino-Soviet "puppet" who wanted to overthrow the government of South Vietnam because his masters in Moscow and Beijing had presumably told him to do so. Fall's influence served as the catalyst for the change in Fulbright's thinking, as Fall introduced him to the writings of

Philippe Devillers Philippe is a masculine sometimes feminin given name, cognate to Philip. It may refer to:

* Philippe of Belgium (born 1960), King of the Belgians (2013–present)

* Philippe (footballer) (born 2000), Brazilian footballer

* Prince Philippe, Count o ...

and

Jean Lacouture

Jean Lacouture (9 June 1921 – 16 July 2015) was a journalist, historian and author. He was particularly famous for his biographies.

Career

Jean Lacouture was born in Bordeaux, France. He began his career in journalism in 1950 in ''Combat'' ...

. Fulbright made it his mission to learn as much as possible about Vietnam and indeed he had learned so much that at a meeting with the Secretary of State

Dean Rusk

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909December 20, 1994) was the United States Secretary of State from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving Secretary of State after Cordell Hull from the F ...

, Fulbright was able to correct several mistakes made by the former about Vietnamese history, much to Rusk's discomfort.

Although President Lyndon Johnson cajoled Fulbright into sponsoring the Gulf of Tonkin resolution in August 1964, his relationship with the President soured after the 1965 U.S. bombing of Pleiku in central Vietnam — which Fulbright consider a breach of Johnson’s commitment to not escalate the war. Fulbright’s opposition to the war in Vietnam took root, and beginning in 1966, he chaired public Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearings on the conduct of the war.

Fulbright invited President Johnson to appear before the Committee in January 1966 to explain why America was fighting in Vietnam, an offer that the President refused.

On 4 February 1966, Fulbright held the first hearings about the Vietnam War, where

George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly histo ...

and General

James M. Gavin

James Maurice Gavin (March 22, 1907 – February 23, 1990), sometimes called "Jumpin' Jim" and "the jumping general", was a senior United States Army officer, with the rank of lieutenant general, who was the third Commanding General (CG) of the 8 ...

appeared as expert witnesses. The hearings had been prompted by Johnson's request for additional $400 million to pay for the war, which gave Fulbright an excuse to hold them. Kennan testified that the Vietnam War was a grotesque distortion of the containment policy that he had outlined in 1946 and 1947. The World War II hero Gavin testified that it was his opinion as a soldier that the war could not be won as it being fought. On 4 February 1966, in an attempt to upstage the hearings Fulbright was holding in Washington, Johnson called an impromptu

summit in Honolulu in the hope that the media would play more attention to the summit that he had called than to the hearings Fulbright was holding. Johnson's two rebuttal witnesses at the hearings were General Maxwell Taylor and Secretary of State Dean Rusk.

As chairman of the

Foreign Relations Committee, Fulbright held a series of hearings on the Vietnam War from 1966 to 1971, many of which were televised to the nation in their entirety, a rarity until

C-SPAN

Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN ) is an American cable and satellite television network that was created in 1979 by the cable television industry as a nonprofit public service. It televises many proceedings of the United States ...

.

Fulbright's reputation as a well-informed expert on foreign policy and his folksy Southern drawl, which made him sound "authentic" to ordinary Americans, made a formidable opponent for Johnson. During his exchanges with Taylor, Fulbright equated the firebombing of Japanese cities in World War II with the

Operation Rolling Thunder

Operation Rolling Thunder was a gradual and sustained aerial bombardment campaign conducted by the United States (U.S.) 2nd Air Division (later Seventh Air Force), U.S. Navy, and Republic of Vietnam Air Force (RVNAF) against the Democratic Repub ...

bombings of North Vietnam and the use of napalm in South Vietnam, much to Taylor's discomfort. Fulbright condemned the bombing of North Vietnam and asked Taylor to think of the "millions of little children, sweet little children, innocent pure babies who love their mothers, and mothers who love their children, just like you love your son, thousands of little children, who never did us any harm, being slowly burned to death." A visibly uncomfortable Taylor stated that the United States was not targeting civilians in either Vietnam. Johnson called the hearings "a very, very disastrous break."

As Fulbright had once been Johnson's friend, his criticism of the war was seen as a personal betrayal and Johnson lashed out in especially vitriolic terms against him. Johnson took the view that at least Senator

Wayne Morse

Wayne Lyman Morse (October 20, 1900 – July 22, 1974) was an American attorney and United States Senator from Oregon. Morse is well known for opposing his party's leadership and for his opposition to the Vietnam War on constitutional grounds.

...

had always been opposed to the Vietnam War, but Fulbright had promised him to support his Vietnam policy in 1964, causing him to see Fulbright as a "Judas" figure. Johnson liked to mock Fulbright as "Senator Halfbright" and sneered it was astonishing that someone as "stupid" as Fulbright had been awarded a degree at Oxford.

In April 1966, Fulbright delivered a speech at

Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hem ...

, where Johnson had delivered a forthright defense of the war just a year earlier. Fulbright was sharply critical of the war. In his speech delivered in his usual folksy Southern drawl, Fulbright stated that the United States was "in danger of losing its perspective on what exactly is within the realm of its power and what is beyond it." Warning of what he called "the arrogance of power," Fulbright declared "we are not living up to our capacity and promise as a civilized power for the world." He called the war a betrayal of American values. Johnson was furious with the speech, which he saw a personal attack from a man who had once been his friend and believed the remark about the "arrogance of power" to be about him. Johnson lashed out in a speech in which he called Fulbright and other critics of the war "nervous Nellies," who knew the war in Vietnam could and would be won but were just too cowardly to fight on to the final victory.

In 1966, Fulbright published ''The Arrogance of Power'', which attacked the justification of the Vietnam War, Congress's failure to set limits on it, and the impulses that had given rise to it. Fulbright's scathing critique undermined the

elite consensus that the military intervention in

Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

was necessitated by

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

geopolitics

Geopolitics (from Greek γῆ ''gê'' "earth, land" and πολιτική ''politikḗ'' "politics") is the study of the effects of Earth's geography (human and physical) on politics and international relations. While geopolitics usually refers to ...

.

By 1967, the Senate was divided into three blocs. There was an antiwar "dove" bloc, led by Fulbright; a pro-war "hawk" bloc, led by the conservative Southern Democrat Senator

John C. Stennis, and a third bloc consisting of waverers, who tended to shift their positions about war in tune with public opinion and moved variously closer to doves and hawks as they followed the public opinion polls. In contrast to his hostile attitudes towards Fulbright, Johnson was afraid of being labeled as soft on communism and so tended to try to appease Stennis and the hawks, who kept pressuring for more-and-more aggressive measures in Vietnam. In criticizing the war, Fulbright was careful to draw a distinction between condemning the war and condemning the ordinary soldiers fighting the war. After General

William Westmoreland

William Childs Westmoreland (March 26, 1914 – July 18, 2005) was a United States Army general, most notably commander of United States forces during the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1968. He served as Chief of Staff of the United States Army from ...

gave a speech in 1967 before a joint session of Congress, Fulbright stated, "From the military standpoint, it was fine. The point is the policy that put our boys there." On 25 July 1967, Fulbright was invited with all of the other chairmen of the Senate committees to the White House to hear Johnson say that the war was being won. Fulbright told Johnson: "Mr. President, what you really need to do is stop the war. That will solve all your problems. Vietnam is ruining our domestic and our foreign policy. I will not support it anymore." To prove that he was serious, Fulbright threatened to block a foreign aid bill before his committee and said that it was the only way to make Johnson pay attention to his concerns. Johnson accused Fulbright of wanting to ruin America's reputation around the world. Using his favorite tactic of seeking to divide his opponents, Johnson told the other senators: "I understand all of you feel you under the gun when you are down here, at least according to Bill Fulbright." Fulbright replied: "Well, my position is that Vietnam is central to the whole problem. We need a new look. The effects of Vietnam are hurting the budget and foreign relations generally." Johnson exploded in fury: "Bill, everybody doesn't have a blind spot like you do. You say, 'Don't bomb North Vietnam', on just about everything. I don't have simple solution you have.... I am not going to tell our men in the field to put their right hands behind their backs and fight only with their lefts. If you want me to get out of Vietnam, then you have the prerogative of taking the resolution which we are out there now. You can repeal it tomorrow. You can tell the troops to come home. You can tell General Westmoreland that he doesn't know what is doing." As Johnson's face was red, Senate Majority Leader

Mike Mansfield

Michael Joseph Mansfield (March 16, 1903 – October 5, 2001) was an American politician and diplomat. A Democratic Party (United States), Democrat, he served as a United States House of Representatives, U.S. representative (1943–1953) and a ...

decided to calm matters down by changing the subject.

In early 1968, Fulbright was deeply depressed as he stated: "The President, unfortunately, seems to have closed his mind to the consideration of any alternative, and his Rasputin-W.W. Rostow-seems able to isolate him from other views, and the Secretary

f State

F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''.

Hist ...

happens to agree. I regret that I am unable to break this crust of immunity." However, after

Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the Lis ...

was fired as Defense Secretary, Fulbright saw a "ray of light" as the man who replaced McNamara,

Clark Clifford

Clark McAdams Clifford (December 25, 1906October 10, 1998) was an American lawyer who served as an important political adviser to Democratic presidents Harry S. Truman, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Jimmy Carter. His official governme ...

, was a longstanding "close personal friend." Johnson had appointed Clifford Defense Secretary because he was a hawk, but Fulbright sought to change his mind about Vietnam. Fulbright invited Clifford to a secret meeting in which he introduced the newly appointed Defense Secretary to two World War II heroes, General

James M. Gavin

James Maurice Gavin (March 22, 1907 – February 23, 1990), sometimes called "Jumpin' Jim" and "the jumping general", was a senior United States Army officer, with the rank of lieutenant general, who was the third Commanding General (CG) of the 8 ...

and General

Matthew Ridgway

General Matthew Bunker Ridgway (March 3, 1895 – July 26, 1993) was a senior officer in the United States Army, who served as Supreme Allied Commander Europe (1952–1953) and the 19th Chief of Staff of the United States Army (1953–1955). Altho ...

. Both Gavin and Ridgway were emphatic that the United States could not win the war in Vietnam, and their opposition to the war helped to change Clifford's mind. Despite his success with Clifford, Fulbright was close to despair as he wrote in a letter to

Erich Fromm

Erich Seligmann Fromm (; ; March 23, 1900 – March 18, 1980) was a German social psychologist, psychoanalyst, sociologist, humanistic philosopher, and democratic socialist. He was a German Jew who fled the Nazi regime and settled in the U ...

that this "literally a miasma of madness in the city, enveloping everyone in the administration and most of those in Congress. I am at a loss of words to describe the idiocy of what we are doing."

Seeing that the Johnson administration was reeling in the wake of the

Tet Offensive

The Tet Offensive was a major escalation and one of the largest military campaigns of the Vietnam War. It was launched on January 30, 1968 by forces of the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) against the forces o ...

, Fulbright in February 1968 called for hearings by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee into the Gulf of Tonkin incident, as Fulbright noted that there were several aspects of the claim that North Vietnamese torpedo boats had attacked American destroyers in international waters that seemed dubious and questionable. McNamara was subpoenaed, and the televised hearings led to "fireworks" as Fulbright repeatedly asked difficult answers about De Soto raids on North Vietnam and

Operation 34A

Operation 34A (full name, Operational Plan 34A, also known as OPLAN 34-Alpha) was a highly classified United States program of covert actions against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV or North Vietnam), consisting of agent team insertions, ...

. On 11 March 1968, Secretary of State

Dean Rusk

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909December 20, 1994) was the United States Secretary of State from 1961 to 1969 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, the second-longest serving Secretary of State after Cordell Hull from the F ...

appeared before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Fulbright made his sympathies clear by wearing a tie decorated with doves carrying olive branches. Through Rusk was scheduled to testify about the Gulf of Tonkin incident, the previous day in ''The New York Times'' had appeared a leaked story that Westmoreland had requested for Johnson to send 206,000 more troops to Vietnam. During Rusk's two days of testimony, the main issue turned out to be the troop request with Fulbright insisting for Johnson to seek congressional approval first. In response to Fulbright's questions, Rusk stated that if more troops were sent to Vietnam, the president would consult "appropriate members of Congress." Most notably, several senators who had voted with Stennis and the other hawks now aligned themselves with Fulbright, which indicated that Congress was turning against the war.

In late October 1968, after Johnson announced a halt in bombing in North Vietnam in accordance with peace talks, Fulbright stated that his hopefulness that the announcement would lead to a general ceasefire.

Nixon administration

In March 1969, Secretary of State

William P. Rogers

William Pierce Rogers (June 23, 1913 – January 2, 2001) was an American diplomat and attorney. He served as United States Attorney General under President Dwight D. Eisenhower and United States Secretary of State under President Richard Nixo ...

testified at a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing on the

Nixon administration

Richard Nixon's tenure as the List of presidents of the United States, 37th president of the United States began with First inauguration of Richard Nixon, his first inauguration on January 20, 1969, and ended when he resigned on August 9, 1974 ...

's foreign policy, Fulbright telling Rogers that the appearance was both useful and promising. In April 1969, Fublright received a letter from a former soldier who served in Vietnam, Ron Ridenhour, containing the results of Ridenhour's investigation into the

My Lai massacre

My or MY may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* My (radio station), a Malaysian radio station

* Little My, a fictional character in the Moomins universe

* ''My'' (album), by Edyta Górniak

* ''My'' (EP), by Cho Mi-yeon

Business

* Market ...