J. Havens Richards on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

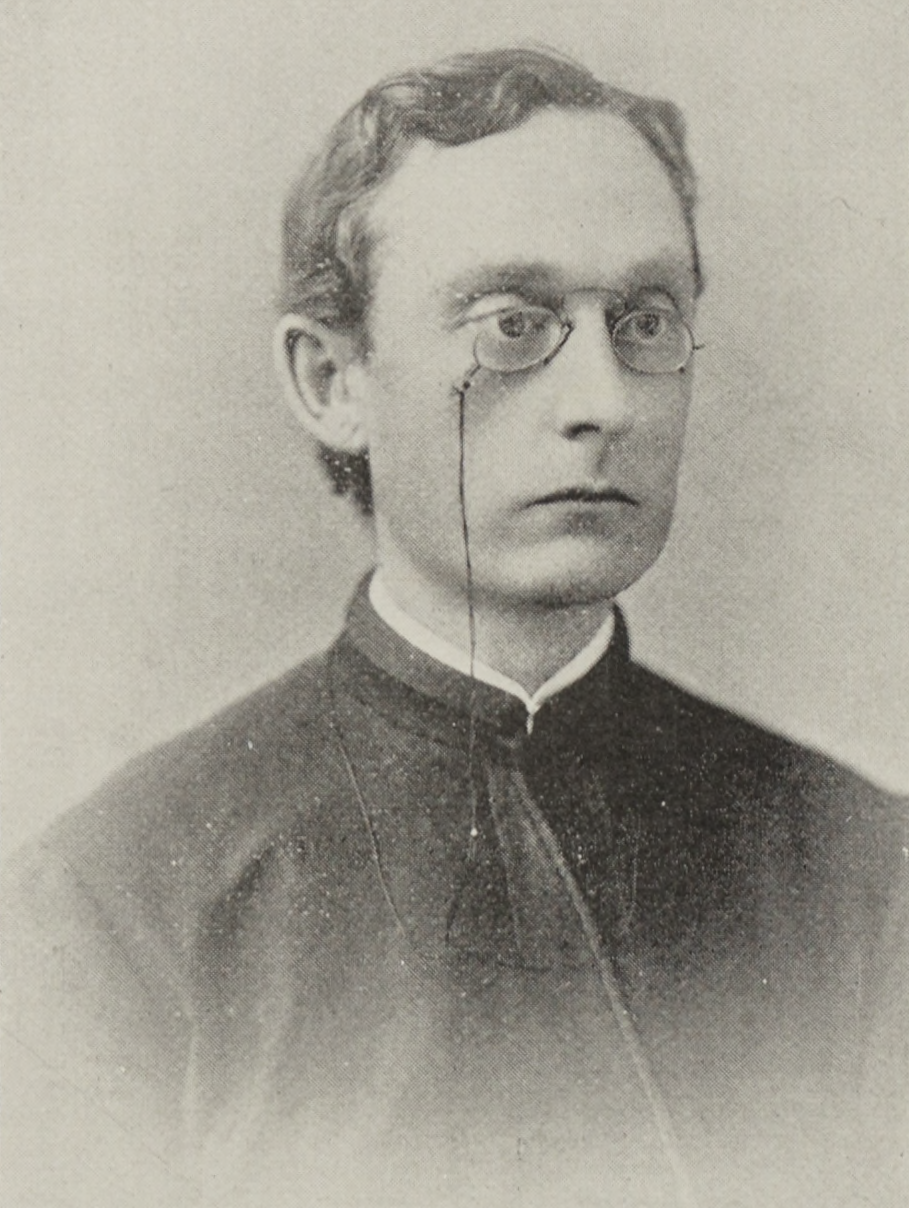

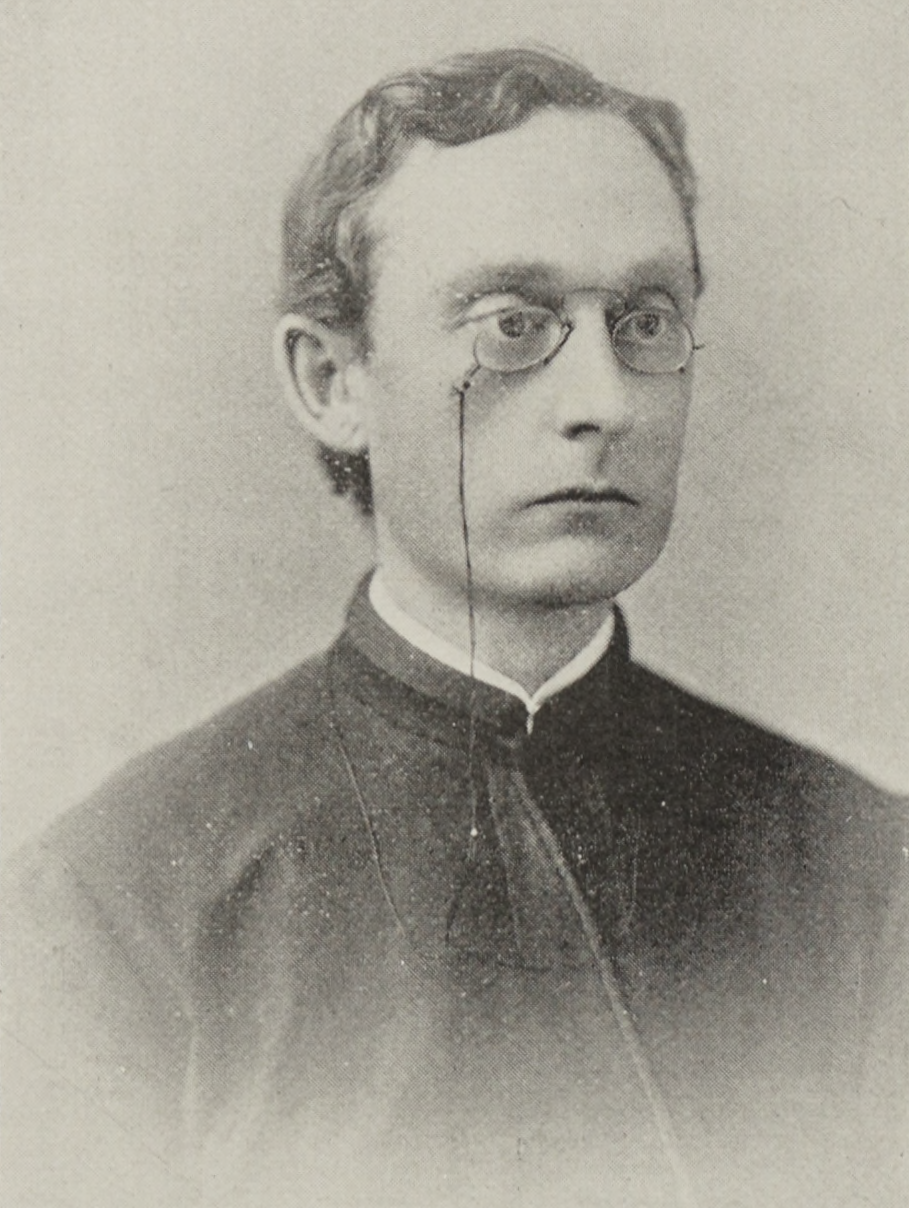

Joseph Havens Richards (born Havens Cowles Richards; November 8, 1851 – June 9, 1923) was an American

Richards was born on November 8, 1851, in

Richards was born on November 8, 1851, in

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

priest and Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

who became a prominent president of Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private research university in the Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789 as Georg ...

, where he instituted major reforms and significantly enhanced the quality and stature of the university. Richards was born to a prominent Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

family; his father was an Episcopal

Episcopal may refer to:

*Of or relating to a bishop, an overseer in the Christian church

*Episcopate, the see of a bishop – a diocese

*Episcopal Church (disambiguation), any church with "Episcopal" in its name

** Episcopal Church (United State ...

priest who controversially converted to Catholicism and had the infant Richards secretly baptized

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

as a Catholic.

Richards became the president of Georgetown University in 1888 and undertook significant construction, such as the completion of Healy Hall

Healy Hall is a National Historic Landmark and the flagship building of the main campus of Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. Constructed between 1877 and 1879, the hall was designed by Paul J. Pelz and John L. Smithmeyer, both of whom also ...

, which included work on Gaston Hall

Gaston Hall is an auditorium located on the third and fourth floors of the north tower of Healy Hall on Georgetown University's main campus in Washington, D.C. Named for Georgetown's first student, William Gaston, who also helped secure the unive ...

and Riggs Library, and the building of Dahlgren Chapel. Richards sought to transform Georgetown into a modern, comprehensive university. To that end, he bolstered the graduate programs

Postgraduate or graduate education refers to academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications pursued by post-secondary students who have earned an undergraduate ( bachelor's) degree.

The organization and stru ...

, expanded the School of Medicine

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, MB ...

and Law School

A law school (also known as a law centre or college of law) is an institution specializing in legal education, usually involved as part of a process for becoming a lawyer within a given jurisdiction.

Law degrees Argentina

In Argentina, ...

, established the Georgetown University Hospital, improved the astronomical observatory, and recruited prominent faculty. He also navigated tensions with the newly established Catholic University of America

The Catholic University of America (CUA) is a private Roman Catholic research university in Washington, D.C. It is a pontifical university of the Catholic Church in the United States and the only institution of higher education founded by U.S. ...

, which was located in the same city. Richards fought anti-Catholic discrimination by Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States. The term ''Ivy League'' is typically used beyond the sports context to refer to the eight schools ...

universities, resulting in Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each class ...

admitting graduates of some Jesuit universities.

Upon the end of his term in 1898, Richards engaged in pastoral work attached to Jesuit educational institutions throughout the northeastern United States. He became the president of Regis High School and the Loyola School in New York City in 1915, and he was then made superior of the Jesuit retreat center on Manresa Island

Manresa Island is a former island located in Norwalk, Connecticut, at the mouth of Norwalk Harbor in the Long Island Sound. The earliest name for the landform was Boutons Island, which dates to 1664. By the 19th century, the island had been pu ...

in Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

. Richards died at the College of the Holy Cross

The College of the Holy Cross is a private, Jesuit liberal arts college in Worcester, Massachusetts, about 40 miles (64 km) west of Boston. Founded in 1843, Holy Cross is the oldest Catholic college in New England and one of the oldest ...

in 1923.

Early life

Richards was born on November 8, 1851, in

Richards was born on November 8, 1851, in Columbus, Ohio

Columbus () is the state capital and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the 14th-most populous city in the U.S., the second-most populous city in the Midwest, after Chicago, and t ...

. His parents were Henry Livingston Richards and Cynthia Cowles, who married on May 1, 1842, in Worthington, Ohio

Worthington is a city in Franklin County, Ohio, United States, and is a northern suburb of Columbus. The population in the 2020 Census was 14,786. The city was founded in 1803 by the Scioto Company led by James Kilbourne, who was later elected to ...

. Havens Cowles was the youngest of eight children, three of whom died in infancy. His surviving siblings were: Laura Isabella (b. 1843), Henry Livingston, Jr. (b. 1846), and William Douglas (b. 1848).

Henry Livingston Richards was an Episcopal

Episcopal may refer to:

*Of or relating to a bishop, an overseer in the Christian church

*Episcopate, the see of a bishop – a diocese

*Episcopal Church (disambiguation), any church with "Episcopal" in its name

** Episcopal Church (United State ...

priest and the pastor of a church in Columbus. To the surprise of many, on January 25, 1852, he sought to convert to Catholicism, two months after Havens Cowles's birth. He was said to have been moved during a visit to New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, where he saw whites and enslaved blacks receiving the Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

side by side at the altar rail

The altar rail (also known as a communion rail or chancel rail) is a low barrier, sometimes ornate and usually made of stone, wood or metal in some combination, delimiting the chancel or the sanctuary and altar in a church, from the nave and oth ...

in a Catholic church. He was baptized

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

by Caspar Henry Borgess

Caspar Henry Borgess (August 1, 1826 – May 3, 1890) was a German-born American prelate of the Catholic Church. He was the second Bishop of Detroit, serving from 1871 to 1887.

Biography Early life

Borgess was born on August 1, 1826, in the villag ...

at the Holy Cross Church in Columbus. One day, following his conversion, he sneaked out of the house with the infant Havens Cowles and brought him to Holy Cross, where Havens Cowles Richards was also baptized by Borgess. These two conversions disturbed Havens Cowles's mother, Cynthia, who was Episcopalian, and her relatives encouraged her to leave her husband. Likewise, Henry Livingston was ostracized by his family and acquaintances in Ohio. As a result, he abandoned his ministry and moved to New York City to search for work in business, leaving his family in the care of his father in Granville, Ohio

Granville is a Village (United States)#Ohio, village in Licking County, Ohio, United States. The population was 5,646 at the United States Census 2010, 2010 census. The village is located in a rural area of rolling hills in central Ohio. It is e ...

. While there, Cynthia Cowles followed her husband in converting to Catholicism. She moved with her children to Jersey City, New Jersey

Jersey City is the second-most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, after Newark.conditionally baptized on May 14, 1856, at St. Peter's Church. All the other children were eventually baptized as well.

Richards's father sought to send all his children to Catholic schools but was at times unable to. Therefore, Richards attended both Catholic and

Richards's father sought to send all his children to Catholic schools but was at times unable to. Therefore, Richards attended both Catholic and

Richards's most immediate task upon taking office was the completion of

Richards's most immediate task upon taking office was the completion of

Following his retirement from the presidency, Richards became the spiritual father of the novitiate in Frederick. He remained interested in Georgetown's astronomical observatory, and he petitioned to have a station established in South Africa so that the entire sky could be studied. The following year, he became the spiritual father of Boston College, where he established the Boston Alumni Sodality. When not in Boston, he spent time in

Following his retirement from the presidency, Richards became the spiritual father of the novitiate in Frederick. He remained interested in Georgetown's astronomical observatory, and he petitioned to have a station established in South Africa so that the entire sky could be studied. The following year, he became the spiritual father of Boston College, where he established the Boston Alumni Sodality. When not in Boston, he spent time in

Ancestry

Richards was born into a prominent family that traced its lineage tocolonial America

The colonial history of the United States covers the history of European colonization of North America from the early 17th century until the incorporation of the Thirteen Colonies into the United States after the Revolutionary War. In the ...

on both his paternal and maternal sides. His uncle was Orestes Brownson

Orestes Augustus Brownson (September 16, 1803 – April 17, 1876) was an American intellectual and activist, preacher, labor organizer, and noted Catholic convert and writer.

Brownson was a publicist, a career which spanned his affiliation with ...

, a Catholic activist and intellectual. On his mother's side, he was a descendant of James Kilbourne, a colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

in the U.S. Army who led a regiment on the American frontier

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of United States territorial acquisitions, American expansion in mainland North Amer ...

in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, founded the city of Worthington, Ohio, and became a United States Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from Ohio.

On his father's side, Richards's lineage included combatants in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, such as William Richards (his great-grandfather), who led a contingent of troops that took part in the siege at the Battle of Fort Slongo and who later fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill was fought on June 17, 1775, during the Siege of Boston in the first stage of the American Revolutionary War. The battle is named after Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts, which was peripherally involved in ...

as a colonel. Through William Richards, he traced his ancestry to James Richards, who was documented in 1634 as residing on the Eel River in Plymouth, Massachusetts

Plymouth (; historically known as Plimouth and Plimoth) is a town in Plymouth County, Massachusetts, United States. Located in Greater Boston, the town holds a place of great prominence in American history, folklore, and culture, and is known as ...

.

Education

Richards's father sought to send all his children to Catholic schools but was at times unable to. Therefore, Richards attended both Catholic and

Richards's father sought to send all his children to Catholic schools but was at times unable to. Therefore, Richards attended both Catholic and public schools

Public school may refer to:

*State school (known as a public school in many countries), a no-fee school, publicly funded and operated by the government

*Public school (United Kingdom), certain elite fee-charging independent schools in England and ...

in Jersey City. At the age of fourteen, he quit school and took up work as a bookkeeper for his father. Four years later, the two of them moved to Boston, Massachusetts, where they worked in the steel industry.

In September 1869, Richards enrolled at Boston College

Boston College (BC) is a private Jesuit research university in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. Founded in 1863, the university has more than 9,300 full-time undergraduates and nearly 5,000 graduate students. Although Boston College is classifie ...

. The rest of his family joined him and his father in Boston in July of that year. Richards remained at the college for three years, where he was active in school sports, before entering the Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

and proceeding to the novitiate

The novitiate, also called the noviciate, is the period of training and preparation that a Christian ''novice'' (or ''prospective'') monastic, apostolic, or member of a religious order undergoes prior to taking vows in order to discern whether ...

in Frederick, Maryland

Frederick is a city in and the county seat of Frederick County, Maryland. It is part of the Baltimore–Washington Metropolitan Area. Frederick has long been an important crossroads, located at the intersection of a major north–south Native ...

, on August 7, 1872. Upon entering the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of d ...

, he changed his name to Joseph Havens Richards.

At the end of his probationary period

In a workplace setting, probation (or a probationary period) is a status given to new employees and trainees of a company, business, or organization. This status allows a supervisor, training official, or manager to evaluate the progress and sk ...

, Richards was sent to Woodstock College

Woodstock College was a Jesuit seminary that existed from 1869 to 1974. It was the oldest Jesuit seminary in the United States. The school was located in Woodstock, Maryland, west of Baltimore, from its establishment until 1969, when it moved to ...

in 1874, where he studied philosophy for four years. He then went to Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private research university in the Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789 as Georg ...

as a professor of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

and mathematics, doing work in chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

during his vacations. In the summers of 1879 and 1880, he was sent by the Jesuit provincial superior to study at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. In July 1883, he returned to Woodstock for four years of theological

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

studies. The provincial superior made an exception for Richards to be ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform va ...

after only two years because his father was ill. Therefore, on August 29, 1885, he was ordained a priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

by James Gibbons

James Cardinal Gibbons (July 23, 1834 – March 24, 1921) was a senior-ranking American prelate of the Catholic Church who served as Apostolic Vicar of North Carolina from 1868 to 1872, Bishop of Richmond from 1872 to 1877, and as ninth ...

, the Archbishop of Baltimore, in the college's chapel. He completed his theological studies in 1887 and returned to Frederick to complete his tertianship Tertianship is the final period of formation for members of the Society of Jesus. Upon invitation of the Provincial, it usually begins three to five years after completion of graduate studies. It is a time when the candidate for final vows steps ba ...

.

Georgetown University

Immediately after the completion of hisJesuit formation

Jesuit formation, or the training of Jesuits, is the process by which candidates are prepared for ordained or brotherly service in the Society of Jesus, the world's largest male Catholic religious order. The process is based on the Constitution o ...

, Richards was made the rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

and president of Georgetown University, taking office on August 15, 1888, and succeeding James A. Doonan. He had a plan to transform Georgetown into a modern, comprehensive institution that would be the leading university of both the Catholic Church and the United States. This role would be amplified by the fact that the university was located in the nation's capital.

Curriculum improvements

Though Richards sought to dispel the perception thatJesuit schools

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

were of inferior quality than their secular counterparts, he maintained that the curriculum of the ''Ratio Studiorum

The ''Ratio atque Institutio Studiorum Societatis Iesu'' (''Method and System of the Studies of the Society of Jesus''), often abbreviated as ''Ratio Studiorum'' (Latin: ''Plan of Studies''), was a document that standardized the globally influen ...

'' should be preserved. Therefore, he revitalized the graduate programs

Postgraduate or graduate education refers to academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications pursued by post-secondary students who have earned an undergraduate ( bachelor's) degree.

The organization and stru ...

of the university, introduced new courses in the law school, and oversaw construction of a new law building in 1892. He also sought to establish an electrical, chemical, and civil engineering program, but this did not come to fruition. For the first time, graduates of the university were authorized to wear a hood as part of their academic regalia. Richards sought to induce prominent scholars to join the faculty of Georgetown; he recruited the Austrian astronomer Johann Georg Hagen

Johann (John) Georg Hagen (March 6, 1847 – September 6, 1930) was an Austrian Jesuit priest and astronomer. After serving as Director of the Georgetown University Observatory he was called to Rome by Pope Pius X in 1906 to be the first Jes ...

and several distinguished scientists from the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

.

Graduate courses in the arts and sciences were re-established in 1889, and courses in theology and philosophy returned to the university, which had previously been moved to Boston and then to Woodstock College. Richards criticized the decision to relocate the theological training of Jesuits from Georgetown to the "semi-wilderness" of Woodstock, which was "remote from libraries, from contact with the learned world, and from all the stimulating influences which affect intellectual life".

Richards expanded the School of Medicine

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, MB ...

by establishing a chair and laboratory of bacteriology; increasing the number of instructors in anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

, physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

, and surgery; and improving the chemistry curriculum. He also standardized the curriculum and increased its duration from three to four years. The property of the medical school, which theretofore had been owned by its own legal corporation, was transferred to the President and Directors of Georgetown College, giving Richards authority over the appointment of professors. Richards also desired to have a hospital adjoined to the medical school, but there was initially little interest in this among faculty and donors. Eventually, Georgetown University Hospital was completed in 1898, and it was put under the care of the Sisters of Saint Francis.

Richards worked with Bishop John Keane to address tensions with the newly established Catholic University of America

The Catholic University of America (CUA) is a private Roman Catholic research university in Washington, D.C. It is a pontifical university of the Catholic Church in the United States and the only institution of higher education founded by U.S. ...

, which was located in the same city and run by the American bishops

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

. Many feared that it would interfere with Georgetown University, and it did indeed seek to take control of Georgetown's law and medical schools as its own. This proposal was approved by the Jesuit superior general, Luis Martín

Luis Martín García (19 August 1846 – 18 April 1906) was a Spanish Jesuit, elected the twenty-fourth Superior General of the Society of Jesus.

Early years and formation

The third of six brothers, Martín was born of humble parentage in Mel ...

, who feared that the Vatican might suppress Georgetown altogether if it did not acquiesce. The faculties of the law and medical schools publicly protested the proposal, and Catholic University dropped its plans. Eventually, an agreement was reached that Catholic University would focus exclusively on the graduate education of secular priests

In Christianity, the term secular clergy refers to deacons and priests who are not monastics or otherwise members of religious life. A secular priest (sometimes known as a diocesan priest) is a priest who commits themselves to a certain geogra ...

.

Construction

Richards's most immediate task upon taking office was the completion of

Richards's most immediate task upon taking office was the completion of Healy Hall

Healy Hall is a National Historic Landmark and the flagship building of the main campus of Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. Constructed between 1877 and 1879, the hall was designed by Paul J. Pelz and John L. Smithmeyer, both of whom also ...

, construction of which began in 1877 under a predecessor, Patrick F. Healy, but whose interior remained unfinished. Richards was able to have the bulk of the work completed by February 20, 1889, the date on which the university began its three-day centenary celebration. Within Healy Hall, he made improvements to Gaston Hall

Gaston Hall is an auditorium located on the third and fourth floors of the north tower of Healy Hall on Georgetown University's main campus in Washington, D.C. Named for Georgetown's first student, William Gaston, who also helped secure the unive ...

and oversaw the start of work on Riggs Library. Richards improved the university's astronomical observatory, placing Hagen in charge of it, which raised the stature of the university in scientific circles.

In 1892 Richards received a donation from the socialite Elizabeth Wharton Drexel

Elizabeth de la Poer Beresford, Baroness Decies (April 22, 1868 – June 13, 1944), was an American author and Manhattan socialite.

Birth

She was born on April 22, 1868, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Lucy Wharton and Joseph William Drexel ...

for the construction of Dahlgren Chapel of the Sacred Heart

Dahlgren Chapel of the Sacred Heart, often shortened to Dahlgren Chapel, is a Roman Catholic chapel located in Dahlgren Quadrangle on the main campus of Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. The chapel was built in 1893, and is located in th ...

. That year, he also procured the library of historian John Gilmary Shea

John Dawson Gilmary Shea (July 22, 1824 – February 22, 1892) was a writer, editor, and historian of American history in general and American Roman Catholic history specifically. He was also a leading authority on aboriginal native Americans ...

, which extensively documented the history of the Catholic Church in the United States

With 23 percent of the United States' population , the Catholic Church is the country's second largest religious grouping, after Protestantism, and the country's largest single church or Christian denomination where Protestantism is divided i ...

. Richards's presidency came to an end on July 3, 1898, by which time he had experienced worsening health for two years. He was succeeded by John D. Whitney.

Anti-Catholicism in the Ivy League

Richards also took up the cause of fighting discrimination against Catholics by prominentProtestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

universities, especially those of the Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States. The term ''Ivy League'' is typically used beyond the sports context to refer to the eight schools ...

. In 1893, James Jeffrey Roche, the editor of the Catholic Boston newspaper ''The Pilot

A pilot is a person who flies or navigates an aircraft.

Pilot or The Pilot may also refer to:

* Maritime pilot, a person who guides ships through hazardous waters

* Television pilot, a television episode used to sell a series to a television netw ...

'', wrote to Charles William Eliot, the president of Harvard University

The president of Harvard University is the chief academic administration, administrator of Harvard University and the ''Ex officio member, ex officio'' president of the President and Fellows of Harvard College, Harvard Corporation. Each is appoi ...

, about the fact that no Catholic universities were included on the list of institutions whose graduates were automatically eligible for admission to Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each class ...

. Eliot's response, which was published in ''The Pilot'', was that the quality of education at Catholic universities was inferior to that offered at their Protestant counterparts. Richards and other Catholic educators had long believed that anti-Catholic discrimination had been at work at Protestant colleges.

Richards sought a retraction from Eliot, writing to him that graduates of reputable Catholic colleges were better prepared to study law than any other college graduates, and he included information on Georgetown's curriculum. Eliot responded by adding Georgetown, the College of the Holy Cross

The College of the Holy Cross is a private, Jesuit liberal arts college in Worcester, Massachusetts, about 40 miles (64 km) west of Boston. Founded in 1843, Holy Cross is the oldest Catholic college in New England and one of the oldest ...

, and Boston College to the list. Upon the provincial superior's instruction, Richards then unsuccessfully lobbied to have all 24 Jesuit colleges in the United States added to the list.

Pastoral work

Following his retirement from the presidency, Richards became the spiritual father of the novitiate in Frederick. He remained interested in Georgetown's astronomical observatory, and he petitioned to have a station established in South Africa so that the entire sky could be studied. The following year, he became the spiritual father of Boston College, where he established the Boston Alumni Sodality. When not in Boston, he spent time in

Following his retirement from the presidency, Richards became the spiritual father of the novitiate in Frederick. He remained interested in Georgetown's astronomical observatory, and he petitioned to have a station established in South Africa so that the entire sky could be studied. The following year, he became the spiritual father of Boston College, where he established the Boston Alumni Sodality. When not in Boston, he spent time in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, where he worked with the New York Sodality. He also began cataloguing Catholic works in the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

, but his health soon prevented him from continuing. Upon the recommendation that it would benefit his health, Richards moved to the novitiate in Los Gatos, California

Los Gatos (, ; ) is an incorporated town in Santa Clara County, California, United States. The population is 33,529 according to the 2020 census. It is located in the San Francisco Bay Area just southwest of San Jose in the foothills of the ...

, in March 1900, but he was there only briefly before visiting his family in Boston after his mother's death.

Richards returned to Los Gatos in April. In early 1901, he moved back to Frederick, Maryland, where he became minister of the novitiate. Richards then went to St. Andrew-on-Hudson

ST, St, or St. may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Stanza, in poetry

* Suicidal Tendencies, an American heavy metal/hardcore punk band

* Star Trek, a science-fiction media franchise

* Summa Theologica, a compendium of Catholic philosophy an ...

in Hyde Park, New York

Hyde Park is a town in Dutchess County, New York, United States, bordering the Hudson River north of Poughkeepsie. Within the town are the hamlets of Hyde Park, East Park, Staatsburg, and Haviland. Hyde Park is known as the hometown of Frankl ...

, as minister in January 1903, when the novitiate relocated there. Several months later, he was made the procurator and was placed in charge of the mission in Pleasant Valley. He transferred again to Boston College in 1906 as spiritual father, remaining there for a year. From 1907 to July 1909, he was prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect's ...

of the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola at Boston College.

Richards then proceeded to the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola

The Church of St. Ignatius of Loyola is a Catholic parish church located on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, New York City, administered by the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). The parish is under the authority of the Archdiocese of New York, and w ...

in New York City as . After four years, he was sent to Canisius College

Canisius College is a private Jesuit college in Buffalo, New York. It was founded in 1870 by Jesuits from Germany and is named after St. Peter Canisius. Canisius offers more than 100 undergraduate majors and minors, and around 34 master's ...

in Buffalo as minister and prefect of studies. He ceased to be minister in July 1914 but remained as prefect. He was appointed the rector and president of both Regis High School and the Loyola School in New York the following year, succeeding David W. Hearn. Concurrently, he became the pastor of the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola. Being advanced in age, he retired from the position on March 25, 1919, and was succeeded by James J. Kilroy as pastor and as president of Regis and Loyola.

Later years

Following his positions in New York, Richards was made superior ofManresa Island

Manresa Island is a former island located in Norwalk, Connecticut, at the mouth of Norwalk Harbor in the Long Island Sound. The earliest name for the landform was Boutons Island, which dates to 1664. By the 19th century, the island had been pu ...

in Norwalk, Connecticut

, image_map = Fairfield County Connecticut incorporated and unincorporated areas Norwalk highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 230px

, map_caption = Location in Fairfield County, Connecticut, Fairfield County and ...

, where he received Jesuit scholastics and priests from the Diocese of Hartford

The Archdiocese of Hartford is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or archdiocese of the Catholic Church in Hartford County, Connecticut, Hartford, Litchfield County, Connecticut, Litchfield and New Haven County, Connecticut, New Haven counti ...

during the summer for their retreats. During the rest of the year, he lived on the island with just one other Jesuit. In December 1921, he was transferred to Weston College

Weston College of Further and Higher Education is a general college of further and higher education in Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, England. It provides education and vocational training from age 14 to adult. The college provided education to ...

as spiritual father and procurator, ceasing to hold the latter role in September 1922.

On March 2, 1923, Richards suffered a stroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

, which left his speech impaired and the right side of his body paralyzed. He spent seven weeks in the hospital before going to the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is a city and county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, the city's population was 206,518 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the second-List of cities i ...

. He suffered another stroke on June 8 and died the following day.

References

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Richards, Joseph Havens 1851 births 1923 deaths Clergy from Columbus, Ohio Catholics from Ohio Converts to Roman Catholicism from Anglicanism 19th-century American educators 20th-century American educators 19th-century American Jesuits 20th-century American Jesuits St. Stanislaus Novitiate (Frederick, Maryland) alumni Boston College alumni Woodstock College alumni Harvard University alumni Presidents of Georgetown University Pastors of the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola (New York City) Presidents of Regis High School (New York City) Presidents of Loyola School (New York City) Deans and Prefects of Studies of the Georgetown University College of Arts & Sciences