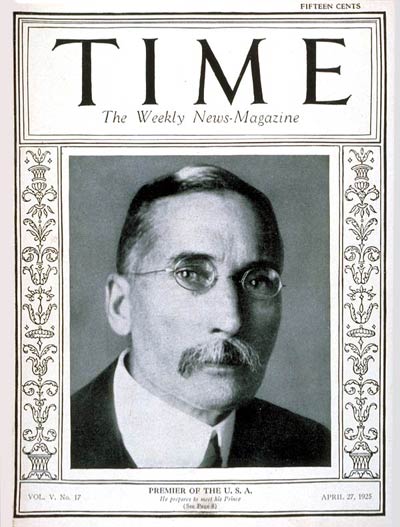

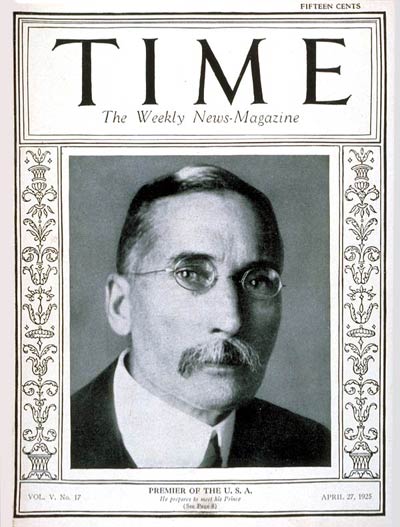

J. B. M. Hertzog on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

General James Barry Munnik Hertzog (3 April 1866 – 21 November 1942), better known as Barry Hertzog or J. B. M. Hertzog, was a South African politician and soldier. He was a

With South Africa then at peace, Hertzog entered politics as the chief organiser of the

With South Africa then at peace, Hertzog entered politics as the chief organiser of the

The establishment of the South African Iron and Steel Industrial Corp in 1930 helped to stimulate economic progress, while the withdrawal of duties on imported raw materials for industrial use encouraged industrial development and created further employment opportunities, but that led to a higher cost of living. Various forms of assistance to agriculture were also introduced. Dairy farmers, for instance, were aided by a levy imposed on all butter sales, while an increase in import taxes protected farmers from international competition. Farmers also benefited from preferential railway tariffs and from the widening availability of loans from the Land Bank. The government also assisted farmers by guaranteeing prices for farm produce, while work colonies were established for those in need of social salvage. Secondary industries were established to improve employment opportunities, which did much to reduce white poverty and enabled many Whites to join the ranks of both the semi-skilled and skilled labour force.

An extension of worker's compensation was carried out, while improvements were made in the standards specified under a contemporary Factory Act, thus bringing the Act into line with international standards, in regard to the length of the working week and the employment of child labour. The law on miners'

The establishment of the South African Iron and Steel Industrial Corp in 1930 helped to stimulate economic progress, while the withdrawal of duties on imported raw materials for industrial use encouraged industrial development and created further employment opportunities, but that led to a higher cost of living. Various forms of assistance to agriculture were also introduced. Dairy farmers, for instance, were aided by a levy imposed on all butter sales, while an increase in import taxes protected farmers from international competition. Farmers also benefited from preferential railway tariffs and from the widening availability of loans from the Land Bank. The government also assisted farmers by guaranteeing prices for farm produce, while work colonies were established for those in need of social salvage. Secondary industries were established to improve employment opportunities, which did much to reduce white poverty and enabled many Whites to join the ranks of both the semi-skilled and skilled labour force.

An extension of worker's compensation was carried out, while improvements were made in the standards specified under a contemporary Factory Act, thus bringing the Act into line with international standards, in regard to the length of the working week and the employment of child labour. The law on miners'

In foreign policy, Hertzog favoured a policy of distance from the British Empire and, as a lifelong

In foreign policy, Hertzog favoured a policy of distance from the British Empire and, as a lifelong

Hertzog died on 21 November 1942, at the age of 76.

A 4-metre-high statue of Hertzog was erected in 1977 at the front lawns of the Union Building. The statue was taken down on 22 November 2013 and moved to a new location in the gardens. It was still in good condition, save for the removal of the spectacles which were originally included on the statue. The statue was removed to make way for a 9-metre-high statue of Nelson Mandela.

Supporters of Hertzog invented the

Hertzog died on 21 November 1942, at the age of 76.

A 4-metre-high statue of Hertzog was erected in 1977 at the front lawns of the Union Building. The statue was taken down on 22 November 2013 and moved to a new location in the gardens. It was still in good condition, save for the removal of the spectacles which were originally included on the statue. The statue was removed to make way for a 9-metre-high statue of Nelson Mandela.

Supporters of Hertzog invented the

Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape Colony, Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controll ...

general during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

who served as the third prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

of the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Trans ...

from 1924 to 1939. Throughout his life he encouraged the development of Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from Free Burghers, predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: ...

culture, determined to prevent Afrikaners from being influenced by British culture

British culture is influenced by the combined nations' history; its historically Christian religious life, its interaction with the cultures of Europe, the traditions of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland and the impact of the British Empire. ...

.

Early life and career

Hertzog first studied law at Victoria College inStellenbosch

Stellenbosch (; )A Universal Pronounc ...

, Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

. In 1889, he went to the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

to read law at the University of Amsterdam

The University of Amsterdam (abbreviated as UvA, nl, Universiteit van Amsterdam) is a public research university located in Amsterdam, Netherlands. The UvA is one of two large, publicly funded research universities in the city, the other being ...

, where he prepared a dissertation, on the strength of which he received his doctorate in law on 12 November 1892.

Hertzog had a law practice in Pretoria from 1892 until 1895, when he was appointed to the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

High Court. During the Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

of 1899–1902, he rose to the rank of general, becoming the assistant chief commandant of the military forces (Commando units) of the Orange Free State. Despite some military reverses, he gained renown as a resourceful leader of the Boer commando

Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin">40_Commando.html" ;"title="Royal Marines from 40 Commando">Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin area of Afghanistan are pictured

A commando is a combatant, or operativ ...

s who chose to continue fighting, the so-called " bitter-enders". Eventually, convinced of the futility of further bloodshed, he signed the Treaty of Vereeniging

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State, on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

This settlement provided f ...

in May 1902.

Early political career

With South Africa then at peace, Hertzog entered politics as the chief organiser of the

With South Africa then at peace, Hertzog entered politics as the chief organiser of the Orangia Unie Party

Orangia Unie (United Orange) was a political party established in May 1906 in the Orange River Colony (formerly the Orange Free State) under the leadership of Abraham Fischer, Martinus Theunis Steyn and J. B. M. Hertzog. When the colony gained sel ...

. In 1907, the Orange River Colony

The Orange River Colony was the British colony created after Britain first occupied (1900) and then annexed (1902) the independent Orange Free State in the Second Boer War. The colony ceased to exist in 1910, when it was absorbed into the Unio ...

gained self-government and Hertzog joined the cabinet as Attorney-General and Director of Education. His insistence that Dutch as well as English be taught in the schools aroused bitter opposition. He was appointed national Minister of Justice in the newly formed Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Trans ...

, and continued in office until 1912. His marked antagonism to the British authorities and Premier Botha led to a ministerial crisis. In 1913, Hertzog led the secession of the Old Boer and anti-British section from the South African Party

nl, Zuidafrikaanse Partij

, leader1_title = Leader (s)

, leader1_name = Louis Botha,Jan Smuts, Barry Hertzog

, foundation =

, dissolution =

, merger = Het VolkSouth African PartyAfrikaner BondOrangia Unie

, merged ...

.

At the outbreak of the Maritz Rebellion

The Maritz rebellion, also known as the Boer revolt or Five Shilling rebellion,General De Wet publicly unfurled the rebel banner in October, when he entered the town of Reitz at the head of an armed commando. He summoned all the town and dema ...

in 1914, Hertzog adopted a neutral stance towards the conflict. In the years following the war, he headed the opposition to the government of General Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

.

Premiership

First government (1924-1929)

In the general election of 1924, Hertzog's National Party defeated theSouth African Party

nl, Zuidafrikaanse Partij

, leader1_title = Leader (s)

, leader1_name = Louis Botha,Jan Smuts, Barry Hertzog

, foundation =

, dissolution =

, merger = Het VolkSouth African PartyAfrikaner BondOrangia Unie

, merged ...

of Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

and formed a coalition government

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

with the South African Labour Party, which became known as the Pact Government. In 1934, the National Party and the South African Party merged to form the United Party, with Hertzog as Prime Minister and leader of the new party.

As prime minister, Hertzog presided over the passage of a wide range of social and economic measures which did much to improve conditions for working-class Whites. According to one historian, "the government of 1924, which combined Hertzog’s NP with the Labour Party, oversaw the foundations of an Afrikaner welfare state".

A Department of Labour was established while the Wages Act (1925) The Wages Act (1925) was an act of the Parliament of South Africa which established a Wage Board which fixed minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which empl ...

laid down minimum wages for unskilled workers, although it excluded farm labourers, domestic servants, and public servants. It also established a Wage Board that regulated pay for certain kinds of work, regardless of racial background (although Whites were the main beneficiaries of the legislation). The Old Age Pensions Act (1927) provided retirement benefits for white workers. Coloureds

Coloureds ( af, Kleurlinge or , ) refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in Southern Africa who may have ancestry from more than one of the various populations inhabiting the region, including African, European, and Asian. South ...

also received the pension, but the maximum for Coloureds was only 70% that of Whites.

Second government (1929-1933)

The establishment of the South African Iron and Steel Industrial Corp in 1930 helped to stimulate economic progress, while the withdrawal of duties on imported raw materials for industrial use encouraged industrial development and created further employment opportunities, but that led to a higher cost of living. Various forms of assistance to agriculture were also introduced. Dairy farmers, for instance, were aided by a levy imposed on all butter sales, while an increase in import taxes protected farmers from international competition. Farmers also benefited from preferential railway tariffs and from the widening availability of loans from the Land Bank. The government also assisted farmers by guaranteeing prices for farm produce, while work colonies were established for those in need of social salvage. Secondary industries were established to improve employment opportunities, which did much to reduce white poverty and enabled many Whites to join the ranks of both the semi-skilled and skilled labour force.

An extension of worker's compensation was carried out, while improvements were made in the standards specified under a contemporary Factory Act, thus bringing the Act into line with international standards, in regard to the length of the working week and the employment of child labour. The law on miners'

The establishment of the South African Iron and Steel Industrial Corp in 1930 helped to stimulate economic progress, while the withdrawal of duties on imported raw materials for industrial use encouraged industrial development and created further employment opportunities, but that led to a higher cost of living. Various forms of assistance to agriculture were also introduced. Dairy farmers, for instance, were aided by a levy imposed on all butter sales, while an increase in import taxes protected farmers from international competition. Farmers also benefited from preferential railway tariffs and from the widening availability of loans from the Land Bank. The government also assisted farmers by guaranteeing prices for farm produce, while work colonies were established for those in need of social salvage. Secondary industries were established to improve employment opportunities, which did much to reduce white poverty and enabled many Whites to join the ranks of both the semi-skilled and skilled labour force.

An extension of worker's compensation was carried out, while improvements were made in the standards specified under a contemporary Factory Act, thus bringing the Act into line with international standards, in regard to the length of the working week and the employment of child labour. The law on miners' phthisis

Phthisis may refer to:

Mythology

* Phthisis (mythology), Classical/Greco-Roman personification of rot, decay and putrefaction

Medical terms

* Phthisis bulbi, shrunken, nonfunctional eye

* Phthisis miliaris, miliary tuberculosis

* Phthisis pulmona ...

(pulmonary tuberculosis) was overhauled, and increased protection of white urban tenants against eviction was introduced at a time when housing was in short supply. The civil service was opened up to Afrikaners through the promotion of bilingualism, while a widening of the suffrage was effected, with the enfranchisement of white women. The pact also instituted "penny postage", automatic telephone exchanges, a cash-on-delivery postal service, and an experimental airmail service which was later made permanent.

The Department of Social Welfare was established in 1937 as a separate government department to deal with social conditions. There was increased expenditure on education for both Whites and Coloureds. Spending on Coloured education rose by 60%, which led to the number of Coloured children in school growing by 30%. Grants for the blind and the disabled were introduced in 1936 and 1937 respectively, while unemployment benefits were introduced in 1937. That same year, the coverage of maintenance grants was extended.

Although the social and economic policies pursued by Hertzog and his ministers did much to improve social and economic conditions for Whites, they did not benefit the majority of South Africans, who found themselves the targets of discriminatory labour laws that entrenched White supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

in South Africa. A Civilised Labour Policy was pursued by the Pact Government, which involved replacing black workers with Whites (typically impoverished Afrikaners), and which was enforced through three key pieces of legislation: the Industrial Conciliation Act No 11 of 1924, the Minimum Wages Act No. 27 of 1925, and the Mines and Works Amendment Act no. 25 of 1926.

The Industrial Conciliation Act (No 11 of 1924) created job reservation for Whites while excluding Blacks from membership of registered trade unions, which therefore prohibited the registration of black trade unions. The Minimum Wages Act (No. 27 of 1925) bestowed upon the Minister for Labour the power to force employers to give preference to Whites when hiring workers, while the Mines and Works Amendment Act (No. 25 of 1926) reinforced a colour bar in the mining industry, while excluding Indian miners from skilled jobs. In a sense, therefore, the discriminatory social and economic policies pursued by the Pact Government helped pave the way for the eventual establishment of the Apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

state.

Constitutionally, Hertzog was a republican, who believed strongly in promoting the independence of the Union of South Africa from the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. His government approved the Statute of Westminster in 1931, and replaced Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

as the second official language with Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gra ...

in 1925, as well as instating a new national flag in 1928. His government approved women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

for white women in 1930, thus strengthening the dominance of the white minority. Property and education requirements for Whites were abandoned in the same year, with those for non-Whites being severely tightened and, in 1936, Blacks were completely taken off the common voters' roll. Separately elected ''Native Representatives'' were instead instated, a policy repeated in the attempts of the later Apartheid regime to disenfranchise all non-Whites during the 1950s. Through the system of gradual disenfranchisement spanning half a century, the South African electorate was not made up entirely of Whites until the 1970 general election.

Third government (1933-1938)

In foreign policy, Hertzog favoured a policy of distance from the British Empire and, as a lifelong

In foreign policy, Hertzog favoured a policy of distance from the British Empire and, as a lifelong Germanophile

A Germanophile, Teutonophile, or Teutophile is a person who is fond of German culture, German people and Germany in general, or who exhibits German patriotism in spite of not being either an ethnic German or a German citizen. The love of the ''Ge ...

, was sympathetic towards revising the international system set up by the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

in favour of lessening the burdens imposed on Germany. Hertzog's cabinet in the 1930s was divided between a pro-British group led by the Anglophile Smuts, and a pro-German group led by Oswald Pirow

Oswald Pirow, QC (Aberdeen, Cape Colony (now Eastern Cape South Africa), 14 August 1890 – Pretoria, Transvaal, Union of South Africa , 11 October 1959) was a South African lawyer and far right politician, who held office as minister of Just ...

, the openly pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

minister of defence, with Hertzog occupying a middle position. Hertzog had an autocratic style of leadership, expecting the cabinet to approve his decisions rather than to discuss them and, as a consequence, the cabinet only met intermittently.

From 1934 onward, South Africa was dominated by an informal "inner cabinet" consisting of Hertzog, Smuts, Pirow, the Finance minister N.C. Havenga, and Native Affairs minister P.G.W. Grobler. Generally, the "inner cabinet" would meet in private and whatever decision they reached in their meetings would be presented to the cabinet to endorse with no discussion. Though Hertzog was not as pro-German as the faction led by Pirow, he tended to see Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

as a "normal state" and as a potential ally, unlike the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

which Hertzog saw as a threat to the West.

Alongside that, Hertzog saw France as the main threat to peace in Europe, viewing the Treaty of Versailles as an unjust and vindictive peace treaty, and argued the French were the principal trouble-makers in Europe by seeking to uphold the Versailles Treaty. Hertzog argued that if Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

had a belligerent foreign policy, it was only because the Treaty of Versailles was intolerably harsh towards Germany, and if the international system was revised to take account of Germany's "legitimate" complaints against Versailles, then Hitler would become a moderate and reasonable statesman. When Germany remilitarized the Rhineland in March 1936, Hertzog informed the British government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_es ...

that there was no possibility of South Africa taking part if Britain decided to go to war over the issue and, in the ensuing crisis, South African diplomats took a very pro-German position, arguing that Germany was justified in violating the Treaty of Versailles by remilitarizing the Rhineland.

Hertzog's principal adviser on foreign affairs was his external affairs state secretary, H.D.J. Bodenstein, an anti-British Afrikaner nationalist and a republican, who was seen as the ''eminence grise'' of South African politics. No other man had the same degree of influence on Hertzog as Bodenstein. Sir William Henry Clark

Sir William Henry Clark (4 January 1876 – 22 November 1952) was a British civil servant and diplomat. He was the first British High Commissioner to Canada 1928–1934.

Early life

Clark was educated at Eton College and Trinity College, Cambr ...

, the British high commissioner to South Africa, had a long-standing feud with Bodenstein, whom he accused of being an Anglophobe, writing in his reports to London that Bodenstein always presented the British position in the worst possible light to Hertzog, and noting with anxiety that Bodenstein's best friend was Emile Wiehle, the German consul in Cape Town. The Germanophile South African minister in Berlin, Stefanus Gie

Stefanus François Naudé Gie (13 July 1884 – 10 April 1945) was a South African historian, politician, and diplomat.

Educator

Gie was born in Worcester, South Africa, Worcester, Cape Colony (now the Western Cape province) to an Afrikaners, ...

, largely embraced Nazi values as his own and, in reports to Pretoria, portrayed Germany as the victim of Jewish plots, arguing that the Nazis' discriminatory policies towards German Jews were only defensive measures. Though Hertzog did not share the anti-Semitism of Gie, the latter's dispatches portraying the Third Reich in a favourable light were used to support the prime minister's foreign policy preferences.

In a statement of foreign policy principles for South Africa drawn up by Pirow for the cabinet in March 1938, the first principle was combating Communism, and the second was having Germany serve as the "bulwark against Bolshevism". In a message to Charles te Water, the South African high commissioner in London in early 1938, Hertzog told him to tell the British that South Africa expected "immediacy, impartiality and sincerity" in resolving the disputes of Europe. Just was meant by that was explained by Hertzog in a letter to the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in March 1938, which stated that South Africa would not fight in any "unjust" wars, and that if Britain choose to go to war over the events in Czechoslovakia, then South Africa would remain neutral. On 22 March 1938, Hertzog sent te Water a telegram stating that South Africa would not under any circumstances go to war with Germany in defence of Czechoslovakia, and stating that he regarded Eastern Europe as being rightfully in Germany's sphere of influence.

Fourth government (1938-1939)

In another letter in the spring of 1938, Hertzog noted that he was "exhausted" by France, and that he wanted Chamberlain to tell the French that the Commonwealth, and South Africa in particular, would be neutral if France went to war with Germany because of a German attack on Czechoslovakia. When te Water reported to Hertzog on 25 May 1938 that the British foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, had promised him that the British government was applying diplomatic pressure on Czechoslovakia to resolve the dispute over theSudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

in Germany's favour, and was pressuring France to abandon its alliance with Czechoslovakia, Hertzog stated his approval. On 14 September 1938, te Water complained to Lord Halifax about the "astonishing episode" of Britain drifting to war with Germany over the Sudetenland issue, stating that as far as South Africa was concerned, Germany was in the right in demanding that mostly German-speaking Sudetenland be allowed to join Germany, and Czechoslovakia and France was in the wrong, the first by refusing the German demands, and the second by having an alliance with Czechoslovakia that encouraged Prague to resist Berlin.

In the middle of September 1938, when Britain was on the verge of war with Germany over the Sudetenland issue, Hertzog clashed in the cabinet with Smuts over the course of action that South Africa would pursue. The former favoured neutrality and the latter was for intervention on Britain's side. On 15 September 1938, Hertzog presented the cabinet with a compromise plan that South Africa would declare neutrality in the event of war, but would be neutral in the most pro-British way possible. The cabinet was divided. Pirow favoured South Africa allying itself with Germany to fight against Britain. On the other hand, Smuts favoured South Africa allying with Britain and going to war with Germany, and threatened to use his influence with the MPs loyal to himself to bring down the government if Hertzog did declare neutrality.

On 19 September 1938, as a part of a peace plan to resolve the crisis, Britain offered to guarantee Czechoslovakian territorial sovereignty if the latter agreed to allow the Sudetenland to join Germany, which led te Water to inform Lord Halifax that South Africa was utterly opposed to being part of the guarantee, and advised Britain against promising one, through he later changed his position, saying that South Africa would "guarantee" Czechoslovakia if it was backed by the League of Nations, and if Germany signed a non-aggression pact with Czechoslovakia.

On 23 September 1938, at the Bad Godesberg

Bad Godesberg ( ksh, Bad Jodesbersch) is a borough ('' Stadtbezirk'') of Bonn, southern North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. From 1949 to 1999, while Bonn was the capital of West Germany, most foreign embassies were in Bad Godesberg. Some buildings ar ...

summit, Hitler rejected the Anglo-French plan for transferring the Sudetenland to Germany as insufficient, thus putting Europe on the brink of war. In a telegram to Chamberlain on 26 September 1938, Hertzog wrote that the differences between the Anglo-French and German positions were "mainly of method" and that, "as the issue was one of no material substance, but merely involves a matter of procedure for arriving at a result to which it is common cause between disputants Germany is entitled", there was no possibility of South Africa going to war over the issue. Even after Hitler's belligerent speech on Berlin on the same day, proclaiming that he would still attack Czechoslovakia unless Prague settled its disputes with Poland and Hungary by 1 October 1938, Hertzog, in a telegram to te Water, wrote that he felt "very deeply that if after this a European war was still to take place the responsibility for that will not be placed upon the shoulders of Germany".

In his messages to te Water in the last days of September 1938, Hertzog consistently portrayed Czechoslovakia and France as the trouble-makers, and argued that Britain must do more to apply pressure on those two states for more concessions to Germany. Te Water and the Canadian high commissioner in London, Vincent Massey, in a joint note on behalf of South Africa and Canada to Lord Halifax, stated that Sir Basil Newton

Sir Basil Cochrane Newton (25 July 1889 – 15 May 1965) was a British diplomat who was ambassador to Czechoslovakia and Iraq. Early career

Newton was the youngest son of George Onslow Newton and his third wife, Lady Alice Cochrane, daughter of ...

, the British minister in Prague, should tell the Czechoslovak president Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš (; 28 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was a Czech politician and statesman who served as the president of Czechoslovakia from 1935 to 1938, and again from 1945 to 1948. He also led the Czechoslovak government-in-exile 1939 to 1945 ...

, that "the obstructive tactics of the Czech government were unwelcome to the British and Dominion governments". On 28 September 1938, Hertzog was able to get the cabinet to approve his policy of pro-British neutrality subject to parliamentary approval, adding that South Africa would only go to war if Germany attacked Britain first. Given his views, Hertzog very much approved of the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

of 30 September 1938, which he regarded as a "just" and "fair" resolution of the German-Czechoslovak dispute.

On 4 September 1939, the United Party caucus revolted against Hertzog's stance of neutrality in World War II, causing Hertzog's government to lose a vote on the issue in parliament by 80 to 67. Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

Sir Patrick Duncan Patrick Duncan may refer to:

*Sir Patrick Duncan (South African politician) (1870–1943), Governor-General of South Africa

*Patrick Sheane Duncan (born 1947), American writer, film producer and director

*Paddy Duncan (1894–1949), Irish football ...

refused Hertzog's request to dissolve parliament and call a general election on the question. Hertzog resigned and his coalition partner Smuts became prime minister. Smuts led the country into war and political re-alignments followed, with Hertzog and his faction joining with Daniel Malan

Daniël François Malan (; 22 May 1874 – 7 February 1959) was a South African politician who served as the fourth prime minister of South Africa from 1948 to 1954. The National Party implemented the system of apartheid, which enforce ...

's opposition Purified National Party

The Purified National Party ( af, Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party) was a break away from Hertzog's National Party which lasted from 1935 to 1948

In 1935 the main portion of the National Party, led by J. B. M. Hertzog, merged with the South African P ...

to form the Herenigde Nasionale Party

The Herenigde Nasionale Party (Reunited National Party) was a political party in South Africa during the 1940s. It was the product of the reunion of Daniel François Malan's Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party (Purified National Party) and J.B.M. Hertzo ...

, with Hertzog becoming the new Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

. However, Hertzog soon lost the support of Malan and his supporters when they rejected Hertzog's platform of equal rights between British South Africans and Afrikaners, prompting Hertzog to resign and retire from politics.

Death and legacy

Hertzog died on 21 November 1942, at the age of 76.

A 4-metre-high statue of Hertzog was erected in 1977 at the front lawns of the Union Building. The statue was taken down on 22 November 2013 and moved to a new location in the gardens. It was still in good condition, save for the removal of the spectacles which were originally included on the statue. The statue was removed to make way for a 9-metre-high statue of Nelson Mandela.

Supporters of Hertzog invented the

Hertzog died on 21 November 1942, at the age of 76.

A 4-metre-high statue of Hertzog was erected in 1977 at the front lawns of the Union Building. The statue was taken down on 22 November 2013 and moved to a new location in the gardens. It was still in good condition, save for the removal of the spectacles which were originally included on the statue. The statue was removed to make way for a 9-metre-high statue of Nelson Mandela.

Supporters of Hertzog invented the Hertzoggie

A Hertzoggie , also known in Afrikaans as a Hertzogkoekie or in English as a Hertzog Cookie, is a jam-filled tartlet or cookie with a coconut topping commonly served on a cup-like pastry base.

The cookie is a popular dessert in South Africa wher ...

, a jam-filled tartlet with a coconut meringue topping, that is still a popular confection in South Africa.

He is the only South African Prime Minister to have served under three monarchs: George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

, Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire and Emperor of India from 20 January 19 ...

, and George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952. ...

, due to serving the year of 1936.

References

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hertzog, James Barry Munnik 1866 births 1942 deaths People from Wellington, Western Cape Cape Colony people Afrikaner people South African people of German descent Members of the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa (NGK) South African Party (Union of South Africa) politicians National Party (South Africa) politicians United Party (South Africa) politicians Herenigde Nasionale Party politicians Prime Ministers of South Africa Justice ministers of South Africa Foreign ministers of South Africa Members of the House of Assembly (South Africa) Orange Free State generals Stellenbosch University alumni University of Amsterdam alumni Alumni of Paul Roos Gymnasium People of the Second Boer War South African Queen's Counsel