J.B. Manson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

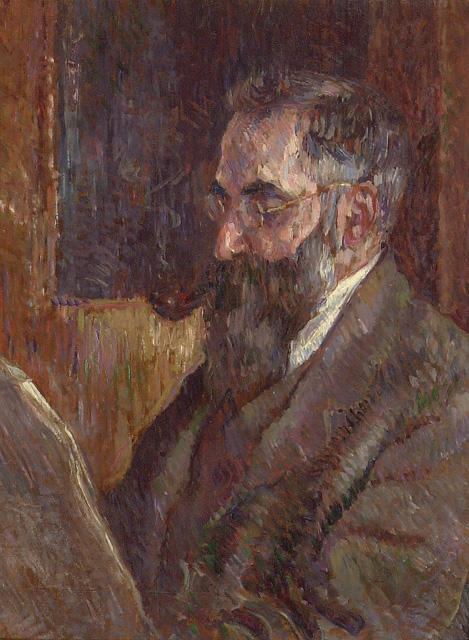

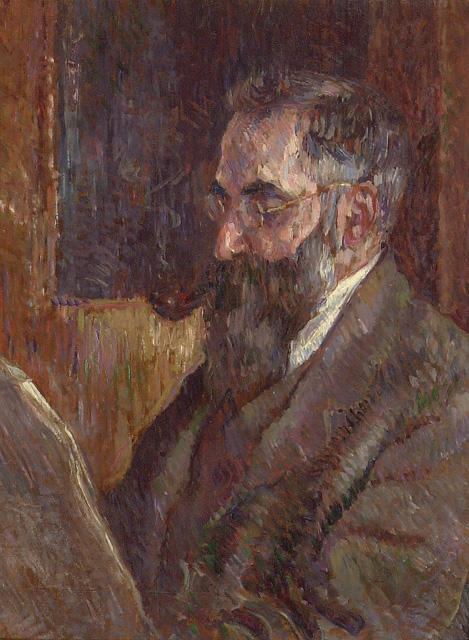

James Bolivar Manson (26 June 1879 in

,

James Bolivar Manson was born at 65 Appach Road,

James Bolivar Manson was born at 65 Appach Road,

In 1903, Manson left the bank job, hanging his silk hat on a pole and encouraging his colleagues to aim stones at it. He married Laugher and they moved to the Latin Quarter in Paris, renting a room for £1 a month and economising in a shared studio with

In 1903, Manson left the bank job, hanging his silk hat on a pole and encouraging his colleagues to aim stones at it. He married Laugher and they moved to the Latin Quarter in Paris, renting a room for £1 a month and economising in a shared studio with

Lilian was a close friend of

Lilian was a close friend of  In 1914, he joined the London Group. From 1915, he showed work with the New English Art Club (NEAC). Because his work for the gallery was considered indispensable, he was exempt from military service; in 1917, he was promoted to Assistant Keeper. In 1919,Buckman, David (2006), ''Dictionary of Artists in Britain since 1945'' Volume 2, p. 1056. Art Dictionaries Ltd, Bristol. Lucien Pissarro formed the Monarro Group with Manson as the London Secretary and

In 1914, he joined the London Group. From 1915, he showed work with the New English Art Club (NEAC). Because his work for the gallery was considered indispensable, he was exempt from military service; in 1917, he was promoted to Assistant Keeper. In 1919,Buckman, David (2006), ''Dictionary of Artists in Britain since 1945'' Volume 2, p. 1056. Art Dictionaries Ltd, Bristol. Lucien Pissarro formed the Monarro Group with Manson as the London Secretary and

During his time as Director, there was no annual funding for acquisitions from the government; he had to decline

During his time as Director, there was no annual funding for acquisitions from the government; he had to decline

On 4 March 1938, Manson attended a dinner organised by Kenneth Clark at the

On 4 March 1938, Manson attended a dinner organised by Kenneth Clark at the

''

"Velvet Revolutionaries"

''

Manson's work in the TateManson's appointment to Tate Clerk in the ''London Gazette''

(2nd column) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Manson, J.B. 1879 births 1945 deaths British curators Directors of the Tate galleries 19th-century English painters English male painters 20th-century English painters People educated at Alleyn's School People from Brixton 20th-century English male artists 19th-century English male artists

London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

– 3 July 1945 in London)"James Bolivar Manson"Tate

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the U ...

collection online, material from Mary Chamot

Mary Chamot (8 November 1899 – 10 May 1993) was a Russian-born English art historian and museum curator, and the first woman curator at the Tate Gallery.

Biography

Chamot was born on 8 November 1899 in Strelna, near Saint Petersburg, the only ...

, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, ''The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, London 1964, II''. Retrieved 18 December 2007. was an artist and worked at the Tate

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the U ...

gallery for 25 years, including serving as its director from 1930 to 1938. In the Tate's own evaluation he was the "least successful" of their directors."Archive journeys: Tate history",

Tate

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the U ...

gallery online. Retrieved 19 December 2007. His time there was frustrated by his stymied ambition as a painter and he declined into alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol (drug), alcohol that results in significant Mental health, mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognize ...

, culminating in a drunken outburst at an official dinner in Paris.Spalding, Frances (1998). ''The Tate: A History'', pp. 62–70. Tate Gallery Publishing, London. . Although his art policies were more advanced than previously at the Tate and embraced Impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open Composition (visual arts), composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating ...

, he stopped short of accepting newer artistic movements like Surrealism

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to l ...

and German Expressionism

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

, thus earning the scorn of critics such as Douglas Cooper. He retired on the grounds of ill health and resumed his career as a flower painter until his death.

Early life

James Bolivar Manson was born at 65 Appach Road,

James Bolivar Manson was born at 65 Appach Road, Brixton

Brixton is a district in south London, part of the London Borough of Lambeth, England. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. Brixton experienced a rapid rise in population during the 19th ce ...

, London, to Margaret Emily (née Deering) and James Alexander Manson, who was the first literary editor of the '' Daily Chronicle'', an editor for Cassell & Co Ltd and of the ''Makers of British Art'' series for Walter Scott Publishing Co.

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet of Beauclerc (17 August 1826 – ) was an English building contractor and publisher. Based in Newcastle upon Tyne, Scott began his profession as a mason, before setting up his own building firm, completing many major ...

Buckman, David (1973), ''James Bolivar Manson'', p. 7, Maltzahn Gallery Ltd, London. Manson's middle name was after Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24 July 1783 – 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama and B ...

. His grandfather was also named James Bolivar Manson. He had an older sister, Margaret Esther Manson, a younger sister, Rhoda Mary Manson, and three younger brothers, Charles Deering Manson, Robert Graham Manson Robert Graham Manson (11 June 1883 – 14 February 1950) was a British-born musician.

He was born in London, one of four sons of James Alexander Manson (born 1852), a journalist and author. One of his brothers was James Bolivar Manson (1879 - 1 ...

(a musician and composer) and Magnus Murray Manson.

At the age of 16, he left Alleyn's School

Alleyn's School is a 4–18 Mixed-sex education, co-educational, Independent school (United Kingdom), independent, Church of England, day school and sixth form in Dulwich, London, England. It is a registered charity and was originally part of Ed ...

, Dulwich

Dulwich (; ) is an area in south London, England. The settlement is mostly in the London Borough of Southwark, with parts in the London Borough of Lambeth, and consists of Dulwich Village, East Dulwich, West Dulwich, and the Southwark half of ...

, and, in the face of his father's opposition to painting as a career, became an office boy with the publisher George Newnes, and then a bank clerk, a job he loathed and lightened with bird imitations and practical jokes. In the meantime he determinedly studied painting at Heatherley School of Fine Art from 1890 and then Lambeth School of Art, and was encouraged by Lilian Beatrice Laugher, a violinist who had studied with Joachim

Joachim (; ''Yəhōyāqīm'', "he whom Yahweh has set up"; ; ) was, according to Christian tradition, the husband of Saint Anne and the father of Mary, the mother of Jesus. The story of Joachim and Anne first appears in the Biblical apocryphal ...

in Berlin and was staying in the household,Buckman, David (1973), pp. 8–9 which by that time was at 7 Ardbeg Road, Herne Hill, London.

Marriage

In 1903, Manson left the bank job, hanging his silk hat on a pole and encouraging his colleagues to aim stones at it. He married Laugher and they moved to the Latin Quarter in Paris, renting a room for £1 a month and economising in a shared studio with

In 1903, Manson left the bank job, hanging his silk hat on a pole and encouraging his colleagues to aim stones at it. He married Laugher and they moved to the Latin Quarter in Paris, renting a room for £1 a month and economising in a shared studio with Charles Polowetski

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was "f ...

, Bernard Gussow

Bernard (''Bernhard'') is a French and West Germanic masculine given name. It is also a surname.

The name is attested from at least the 9th century. West Germanic ''Bernhard'' is composed from the two elements ''bern'' "bear" and ''hard'' "brav ...

and Jacob Epstein, who became a lifelong friend and with whom he studied at the Académie Julian

The Académie Julian () was a private art school for painting and sculpture founded in Paris, France, in 1867 by French painter and teacher Rodolphe Julian (1839–1907) that was active from 1868 through 1968. It remained famous for the number a ...

, still dominated by the Impressionists' enemy, Adolphe Bouguereau

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (; 30 November 1825 – 19 August 1905) was a French academic painter. In his realistic genre paintings, he used mythological themes, making modern interpretations of classical subjects, with an emphasis on the female ...

; occasionally Jean-Paul Laurens

Jean-Paul Laurens (; 28 March 1838 – 23 March 1921) was a French painter and sculptor, and one of the last major exponents of the French Academic style.

Biography

Laurens was born in Fourquevaux and was a pupil of Léon Cogniet and Alexand ...

tutored.

After a year, the Mansons returned to London and their daughter Mary was born, followed two years later by Jean. They lived in the top two floors of 184 Adelaide Road, Hampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, and extends from Watling Street, the A5 road (Roman Watling Street) to Hampstead Heath, a large, hilly expanse of parkland. The area forms the northwest part of the Lon ...

, where his wife gave music lessons at the front and Manson set up a studio at the rear, working out the family's tight budget on the kitchen wall much to her displeasure. In 1908 they moved to a small house at 98 Hampstead Way, where they stayed for 30 years. Lilian succeeded Bernard Shaw's mother as music director at the North London Collegiate School for Girls

North London Collegiate School (NLCS) is an independent school with a day school for girls in England. Founded in Camden Town, it is now located in Edgware, in the London Borough of Harrow. Associate schools are located in South Korea, Jeju I ...

; in 1910 ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' took notice of her revival of Purcell's ''Dido and Aneas'', for which Manson designed and helped to make costumes. In 1910 also, he became a member and Secretary of the Camden Town Group

The Camden Town Group was a group of English Post-Impressionist artists founded in 1911 and active until 1913. They gathered frequently at the studio of painter Walter Sickert in the Camden Town area of London.

History

In 1908, critic Frank R ...

.

Employment at the Tate

Lilian was a close friend of

Lilian was a close friend of Tate

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the U ...

director Charles Aitken

Charles Aitken (12 September 1869 – 9 August 1936) was a British art administrator and was the third Keeper of the Tate Gallery (1911–1917) and the first Director (1917–1930).

Life and work

Charles Aitken was born at Bisho ...

and, in summer 1911, the Mansons stayed with him at a holiday home in Alfriston, Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

. Manson had assisted Aitken with hanging a show at the Tate and the Director was sufficiently impressed to suggest Manson took the job of Clerk, vacant since its former occupant had been pilfering the petty cash. Manson achieved by far the best results out of the four applicants taking the appropriate civil service exam, and, age 33, became Tate Clerk on 9 December 1912 with an annual salary of £150. His reluctance to take the job had been overcome by his wife, who wanted provision for their two daughters; he continued to paint intensely at weekends.

With the Keeper, he was jointly responsible for staff supervision, office administration and care of the collection. Manson is considered to have given Aitken a liking for French Impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open Composition (visual arts), composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating ...

and to have highlighted the Camden Town Group

The Camden Town Group was a group of English Post-Impressionist artists founded in 1911 and active until 1913. They gathered frequently at the studio of painter Walter Sickert in the Camden Town area of London.

History

In 1908, critic Frank R ...

, even though its leader, Walter Sickert, was still outside the official canon. When a Sickert was offered to the Tate in 1915, Manson wrote, "tell the Trustees I think it is a very good Sickert—but the question is whether he is important enough for the Tate. I think not; but as an old friend of the artist perhaps I am a prejudiced judge."

In 1914, he joined the London Group. From 1915, he showed work with the New English Art Club (NEAC). Because his work for the gallery was considered indispensable, he was exempt from military service; in 1917, he was promoted to Assistant Keeper. In 1919,Buckman, David (2006), ''Dictionary of Artists in Britain since 1945'' Volume 2, p. 1056. Art Dictionaries Ltd, Bristol. Lucien Pissarro formed the Monarro Group with Manson as the London Secretary and

In 1914, he joined the London Group. From 1915, he showed work with the New English Art Club (NEAC). Because his work for the gallery was considered indispensable, he was exempt from military service; in 1917, he was promoted to Assistant Keeper. In 1919,Buckman, David (2006), ''Dictionary of Artists in Britain since 1945'' Volume 2, p. 1056. Art Dictionaries Ltd, Bristol. Lucien Pissarro formed the Monarro Group with Manson as the London Secretary and Théo van Rysselberghe

Théophile "Théo" van Rysselberghe (23 November 1862 – 13 December 1926) was a Belgian neo-impressionist painter, who played a pivotal role in the European art scene at the turn of the twentieth century.

Biography

Early years

Born i ...

as the Paris secretary, aiming to show artists inspired by Impressionist

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage ...

painters, Claude Monet

Oscar-Claude Monet (, , ; 14 November 1840 – 5 December 1926) was a French painter and founder of impressionist painting who is seen as a key precursor to modernism, especially in his attempts to paint nature as he perceived it. During ...

and Camille Pissarro

Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro ( , ; 10 July 1830 – 13 November 1903) was a Danish-French Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist painter born on the island of Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, St Thomas (now in the US Virgin Islands, but t ...

; the group ceased three years later. In 1923, at the Leicester Galleries, Manson held his first solo show of work. In 1927, he became a member of the NEAC. His reputation as an artist was primarily as a flower painter and art was his main ambition, but he was uncertain as to whether this would allow him to earn a full-time living—in 1928 he asked Roger Fry

Roger Eliot Fry (14 December 1866 – 9 September 1934) was an English painter and critic, and a member of the Bloomsbury Group. Establishing his reputation as a scholar of the Old Masters, he became an advocate of more recent developme ...

's advice on the matter. However, in 1930, he became Director of the Tate, a post which he held until 1938.

He also wrote art criticism, as well as an introduction to the Tate's collection, ''Hours in the Tate Gallery'' (1926) and books on Degas (1927), Rembrandt

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (, ; 15 July 1606 – 4 October 1669), usually simply known as Rembrandt, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker and draughtsman. An innovative and prolific master in three media, he is generally consid ...

(1929), John Singer Sargent

John Singer Sargent (; January 12, 1856 – April 14, 1925) was an American expatriate artist, considered the "leading portrait painter of his generation" for his evocations of Edwardian-era luxury. He created roughly 900 oil paintings and more ...

and Dutch painting.

Director of the Tate

Manson had a minor accident, which delayed his taking up the post of Director of the Tate by a month, until August 1930. According to the Tate web site, he was "the least successful of Tate's Directors." His own artistic ambitions had not been fulfilled, he had an unhappy marriage and he drank to excess; he suffered from depression, blackouts and paranoia; and he had long periods off work sick. Kenneth Clark described him as having, "a flushed face, white hair and a twinkle in his eye; and this twinkling got him out of scrapes that would have sunk a worthier man without trace." During his time as Director, there was no annual funding for acquisitions from the government; he had to decline

During his time as Director, there was no annual funding for acquisitions from the government; he had to decline Camille Pissarro

Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro ( , ; 10 July 1830 – 13 November 1903) was a Danish-French Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist painter born on the island of Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, St Thomas (now in the US Virgin Islands, but t ...

's offer to loan his painting ''La Causette'' as the gallery lacked funds for transport and insurance. Manson complained to his friend, Lucien Pissarro about the conservative taste of the trustee board—which had rejected a work by both Monet

Oscar-Claude Monet (, , ; 14 November 1840 – 5 December 1926) was a French painter and founder of impressionist painting who is seen as a key precursor to modernism, especially in his attempts to paint nature as he perceived it. During ...

and Renoir—although he himself was averse to Post Impressionist work, neglecting London shows by artists such as Van Gogh

Vincent Willem van Gogh (; 30 March 185329 July 1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter who posthumously became one of the most famous and influential figures in Western art history. In a decade, he created about 2,100 artworks, inclu ...

and Matisse

Henri Émile Benoît Matisse (; 31 December 1869 – 3 November 1954) was a French visual artist, known for both his use of colour and his fluid and original draughtsmanship. He was a draughtsman, printmaker, and sculptor, but is known prima ...

, until he had no option but to accept two oils by the latter in 1933 as part of a bequest. The same year, he and the Trustees rejected a donation of four William Coldstream paintings and two Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi- abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. As well as sculpture, Moore produced ...

sculptures, and, in 1935, declined to buy Matisse's ''Interior with a Figure'' for £2000, turned down the loan of Picabia

Francis Picabia (: born Francis-Marie Martinez de Picabia; 22January 1879 – 30November 1953) was a French avant-garde painter, poet and typographist. After experimenting with Impressionism and Pointillism, Picabia became associated with Cubism ...

's ''Courtyard in France'' and also the offer of a gift of three Roger Fry

Roger Eliot Fry (14 December 1866 – 9 September 1934) was an English painter and critic, and a member of the Bloomsbury Group. Establishing his reputation as a scholar of the Old Masters, he became an advocate of more recent developme ...

oils. In 1938, Manson asked Sir Robert Sainsbury

Sir Robert James Sainsbury (24 October 19062 April 2000), was the son of John Benjamin Sainsbury (the eldest son of John James Sainsbury, the founder of Sainsbury's supermarkets) and along with his wife Lisa began the collection of modern and t ...

if the Tate could borrow a study of Eve by French sculptor Charles Despiau. Sainsbury assented on condition that the gallery also showed the 1932 "''Mother and Child'' of my friend Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi- abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. As well as sculpture, Moore produced ...

." Manson's response was, "Over my dead body."

Although Frank Rutter, a ''Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, whi ...

'' art critic, praised advances in the gallery's position on art since its foundation, others—notably Douglas Cooper—who were familiar with contemporary European avant-garde art, such as Surrealism

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to l ...

and German Expressionism

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

(which was not represented at all in the Tate) considered it "hopelessly insular". Manson preferred to put on a popular show of ''Cricket Pictures'', coinciding with the 1934 Ashes

Ashes may refer to:

*Ash, the solid remnants of fires.

Media and entertainment Art

* ''Ashes'' (Munch), an 1894 painting by Edvard Munch

Film

* ''The Ashes'' (film), a 1965 Polish film by director Andrzej Wajda

* ''Ashes'' (1922 film), a ...

tour, and in 1935 substituted an exhibition by Professor Tonks for a proposed Sickert retrospective.

The high points of his "irregular and dull" exhibition programme were centenaries, in 1933 of the birth of Edward Burne-Jones and in 1937 of the death of John Constable

John Constable (; 11 June 1776 – 31 March 1837) was an English landscape painter in the Romanticism, Romantic tradition. Born in Suffolk, he is known principally for revolutionising the genre of landscape painting with his pictures of Dedha ...

. Other achievements accomplished during his term of office included a formal change of name from "National Gallery, Millbank" to "Tate Gallery" in October 1932, the planting of cherry trees outside in 1933, the installation of electric lighting in 1935 and extra toilets. Manson was on the 1932 Venice Biennale

The Venice Biennale (; it, La Biennale di Venezia) is an international cultural exhibition hosted annually in Venice, Italy by the Biennale Foundation. The biennale has been organised every year since 1895, which makes it the oldest of ...

British selection committee, as well as staging shows in Brussels in 1932 and Bucharest in 1936.

Decline

Towards the end of his term of office, Manson's life declined intoalcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol (drug), alcohol that results in significant Mental health, mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognize ...

; he was drunk at Board meetings and on one occasion was wrapped in a blanket and carried out after he had fallen onto the floor. He suffered a public blow to his prestige, when a staff member wrote in a catalogue that the French artist Utrillo was dead and had been "a confirmed dipsomaniac"—neither of which was true—leading to a court case with Manson named as defendant; settlement in court on 17 February 1938 included the Tate purchase of an Utrillo painting.

On 4 March 1938, Manson attended a dinner organised by Kenneth Clark at the

On 4 March 1938, Manson attended a dinner organised by Kenneth Clark at the Hotel George V

Four Seasons Hotel George V ( ) is a luxury hotel on avenue George V in the 8th arrondissement of Paris.

History

The Hotel George V, named for King George V of the United Kingdom, opened in 1928. It was financed, at a cost of $31 million (60 mi ...

in Paris to celebrate the British Exhibition taking place at the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

museum. Clive Bell recorded the eventualities in a letter to his wife:

Manson arrived at the déjeuner given by the minister of Beaux Arts fantastically drunk—punctuated the ceremony with cat-calls and cock-a-doodle-doos, and finally staggered to his feet, hurled obscene insults at the company in general and the minister in particular, and precipitated himself on the ambassadress, Lady Phipps, some say with amorous intent others with lethal intent.Bell concluded:

the guests fled ices uneaten, coffee undrunk... I hope an example will be made, and that they will seize the opportunity for turning the sot out of the Tate, not because he is a sot, but because he has done nothing but harm to modern painting.Kenneth Clark has stated that Manson was asked to resign on health grounds because of a

Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

request.

In the period before a public announcement was made of his leaving the Tate, he was the cause of further controversy. A number of sculptures, chosen by Marcel Duchamp

Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp (, , ; 28 July 1887 – 2 October 1968) was a French painter, sculptor, chess player, and writer whose work is associated with Cubism, Dada, and conceptual art. Duchamp is commonly regarded, along with Pablo Picasso ...

and en route from Paris to Peggy Guggenheim

Marguerite "Peggy" Guggenheim ( ; August 26, 1898 – December 23, 1979) was an American art collector, bohemian and socialite. Born to the wealthy New York City Guggenheim family, she was the daughter of Benjamin Guggenheim, who went down with t ...

's London gallery, had been held by customs officers, who needed to ascertain whether they were in fact art and thus exempt from duty. In such circumstances, the arbiter was the Director of the Tate. The artists included Jean Arp

Hans Peter Wilhelm Arp (16 September 1886 – 7 June 1966), better known as Jean Arp in English, was a German-French sculptor, painter, and poet. He was known as a Dadaist and an abstract artist.

Early life

Arp was born in Straßburg (now Stras ...

and Raymond Duchamp-Villon

Raymond Duchamp-Villon (5 November 1876 – 9 October 1918) was a French sculptor.

Life and art

Duchamp-Villon was born Pierre-Maurice-Raymond Duchamp in Damville, Eure, in the Normandy region of France, the second son of Eugène and Lucie Duch ...

. Manson pronounced Constantin Brâncuși

Constantin Brâncuși (; February 19, 1876 – March 16, 1957) was a Romanian Sculpture, sculptor, painter and photographer who made his career in France. Considered one of the most influential sculptors of the 20th-century and a pioneer of ...

's ''Sculpture for the Blind'' (a large, smooth, egg-shaped marble) to be "idiotic" and "not art". Letters were written to the press, critics signed a protest petition, and Manson was criticised in the House of Commons; he backed down."Black-Outs"''

Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'', 25 April 1938. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

Retirement

At the age of 58, Manson announced his retirement:My doctor has warned me that my nerves will not stand any further strain... I have begun to have blackouts, in which my actions become automatic. Sometimes these periods last several hours.... I had one of these blackouts at an official luncheon in Paris recently, and startled guests by suddenly crowing like a cock....He applied for a pension for his twenty-five years at the Tate on the grounds of having a nervous breakdown, and received one which he said was worth £1 a day, along with the gift from staff of a paint box to upgrade his habit of carrying paint brushes in paper bags.Buckman, David (1973), p. 42 His successor as Director, Sir

John Rothenstein

Sir John Knewstub Maurice Rothenstein (11 July 1901 – 27 February 1992) was a British arts administrator and art historian.

Biography

John Rothenstein was born in London in 1901, the son of Sir William Rothenstein. The family was connec ...

discovered that Manson had boosted his low salary by selling from the basement work, which was referred to by the staff as "Director's stock".

Manson left his wife and home in Hampstead Garden Suburb in order to "get away from women" and make time to paint, alighting first in Harrington Road, South Kensington

South Kensington, nicknamed Little Paris, is a district just west of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with ...

, and then, not long afterwards, up the road to Boltons Studios. He settled with Elizabeth (Cecily Haywood). From 1939, he showed at the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

. He died in 1945, having observed, "The roses are dying, and so am I."

Legacy

In March and April 1946, a memorial show was held at the Wildenstein Gallery in London with 59 works in oil, watercolour, etchings, drawings and pastel, dating from 1903 to 1945.Buckman, David (1973), p. 46 A second show was held in August and September at theFerens Art Gallery

The Ferens Art Gallery is an art gallery in the English city of Kingston upon Hull. The site and money for the gallery were donated to the city by Thomas Ferens, after whom it is named. The architects were S. N. Cooke and E. C. Davie ...

, Hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

, with 58 works—32 oils, 14 watercolours and 12 pastels.

In 1973, a retrospective was held at Maltzahn Gallery, Cork Street, London. His work is in the Tate

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the U ...

and many other galleries in Britain and abroad.

A major retrospective of the Camden Town Group

The Camden Town Group was a group of English Post-Impressionist artists founded in 1911 and active until 1913. They gathered frequently at the studio of painter Walter Sickert in the Camden Town area of London.

History

In 1908, critic Frank R ...

was held at Tate Britain

Tate Britain, known from 1897 to 1932 as the National Gallery of British Art and from 1932 to 2000 as the Tate Gallery, is an art museum on Millbank in the City of Westminster in London, England. It is part of the Tate network of galleries in ...

in 2008, but omitted eight of the 17 members, including Duncan Grant, James Dickson Innes

James Dickson Innes (27 February 1887 – 22 August 1914) was a British painter, mainly of mountain landscapes but occasionally of figure subjects. He worked in both oils and watercolours.

Style

Of his style, art historian David Fraser Jenkins ...

, Augustus John, Henry Lamb, Wyndham Lewis and Manson, who was, according to Wendy Baron, of "too little individual character".Lambirth, Andrew"Velvet Revolutionaries"

''

The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...

'', 5 March 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

Notes and references

External links

* * Tom Furness, 'James Bolivar Manson 1879–1945', artist biography, January 2011, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), ''The Camden Town Group in Context'', Tate, May 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/james-bolivar-manson-r1105350Manson's work in the Tate

(2nd column) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Manson, J.B. 1879 births 1945 deaths British curators Directors of the Tate galleries 19th-century English painters English male painters 20th-century English painters People educated at Alleyn's School People from Brixton 20th-century English male artists 19th-century English male artists