Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an

Abrahamic

The Abrahamic religions are a group of religions centered around worship of the God of Abraham. Abraham, a Hebrew patriarch, is extensively mentioned throughout Abrahamic religious scriptures such as the Bible and the Quran.

Jewish traditi ...

monotheistic religion

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God.F. L. Cross, Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Ox ...

centred primarily around the

Quran, a religious text considered by

Muslims to be the direct word of

God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

(or ''

Allah

Allah (; ar, الله, translit=Allāh, ) is the common Arabic word for God. In the English language, the word generally refers to God in Islam. The word is thought to be derived by contraction from '' al- ilāh'', which means "the god", a ...

'') as it was revealed to

Muhammad, the

main and final Islamic prophet.

[Peters, F. E. 2009. "Allāh." In , edited by J. L. Esposito. Oxford: Oxford University Press. . (See also]

quick reference

) " e Muslims' understanding of Allāh is based...on the Qurʿān's public witness. Allāh is Unique, the Creator, Sovereign, and Judge of mankind. It is Allāh who directs the universe through his direct action on nature and who has guided human history through his prophets, Abraham, with whom he made his covenant, Moses/Moosa, Jesus/Eesa, and Muḥammad, through all of whom he founded his chosen communities, the 'Peoples of the Book.'" It is the

world's second-largest religion behind

Christianity, with its followers ranging between 1-1.8 billion globally, or around a quarter of the world's population.

Due to the average younger age and higher

fertility rate

The total fertility rate (TFR) of a population is the average number of children that would be born to a woman over her lifetime if:

# she were to experience the exact current age-specific fertility rates (ASFRs) through her lifetime

# she were ...

,

Islam is the world's fastest growing major religious group, and is projected by ''

Pew Research Center'' to be the world's largest religion by the end of the 21st century, surpassing

Christianity.

It teaches that God is

merciful,

all-powerful, and

unique, and has guided humanity through

various prophets,

revealed scriptures, and

natural signs, with the Quran serving as the final and universal revelation and Muhammad serving as the "

Seal of the Prophets" (the last prophet of God).

The teachings and practices of Muhammad () documented in traditional collected accounts () provide a secondary constitutional model for Muslims to follow after the Quran.

Muslims believe that Islam is the complete and universal version of a

primordial faith that was revealed many times through earlier prophets such as

Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as ...

,

Noah,

Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jews ...

,

Moses, and

Jesus, among others; these earlier revelations are attributed to

Judaism and

Christianity, which are regarded in Islam as

spiritual predecessor faiths. They also consider the Quran, when preserved in

Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic ( ar, links=no, ٱلْعَرَبِيَّةُ ٱلْفُصْحَىٰ, al-ʿarabīyah al-fuṣḥā) or Quranic Arabic is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notab ...

, to be the unaltered and final revelation of God to humanity. Like other Abrahamic religions, Islam also teaches of a "

Final Judgement

The Last Judgment, Final Judgment, Day of Reckoning, Day of Judgment, Judgment Day, Doomsday, Day of Resurrection or The Day of the Lord (; ar, یوم القيامة, translit=Yawm al-Qiyāmah or ar, یوم الدین, translit=Yawm ad-Dīn, ...

" wherein the righteous will be rewarded in

paradise

In religion, paradise is a place of exceptional happiness and delight. Paradisiacal notions are often laden with pastoral imagery, and may be cosmogonical or eschatological or both, often compared to the miseries of human civilization: in paradis ...

() and the unrighteous will be punished in

hell

In religion and folklore, hell is a location in the afterlife in which evil souls are subjected to punitive suffering, most often through torture, as eternal punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hells ...

(). The religious concepts and practices of Islam include the

Five Pillars of Islam—considered obligatory acts of worship —and following Islamic law, , which touches on virtually every aspect of life, from

banking and finance

A bank is a financial institution that accepts deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital markets.

Because ...

and

welfare to

women's roles and the

environment

Environment most often refers to:

__NOTOC__

* Natural environment, all living and non-living things occurring naturally

* Biophysical environment, the physical and biological factors along with their chemical interactions that affect an organism or ...

.

[ (See also:]

sharia

via '' Lexico''.) The Five Pillars comprise ''

Shahada'', the Islamic

oath

Traditionally an oath (from Anglo-Saxon ', also called plight) is either a statement of fact or a promise taken by a sacrality as a sign of verity. A common legal substitute for those who conscientiously object to making sacred oaths is to gi ...

and

creed; ''

Salah'', daily

prayers; ''

Zakat

Zakat ( ar, زكاة; , "that which purifies", also Zakat al-mal , "zakat on wealth", or Zakah) is a form of almsgiving, often collected by the Muslim Ummah. It is considered in Islam as a religious obligation, and by Quranic ranking, is n ...

,'' forms of

almsgiving

Alms (, ) are money, food, or other material goods donated to people living in poverty. Providing alms is often considered an act of virtue or charity. The act of providing alms is called almsgiving, and it is a widespread practice in a number ...

;

''Sawm'', religious

fasting; and ''

Hajj

The Hajj (; ar, حَجّ '; sometimes also spelled Hadj, Hadji or Haj in English) is an annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the holiest city for Muslims. Hajj is a mandatory religious duty for Muslims that must be carried o ...

'', a

mandated once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimage to

Mecca during the 12th month of the lunar calendar.

, the religious rite of

circumcision

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Topic ...

, is seen as obligatory or recommendable for male followers.

Prominent

religious festivals

A religious festival is a time of special importance marked by adherents to that religion. Religious festivals are commonly celebrated on recurring cycles in a calendar year or lunar calendar. The science of religious rites and festivals is know ...

include

Ramadan,

Eid al-Fitr

, nickname = Festival of Breaking the Fast, Lesser Eid, Sweet Eid, Sugar Feast

, observedby = Muslims

, type = Islamic

, longtype = Islamic

, significance = Commemoration to mark the end of fasting in Ramadan

, date ...

, and

Eid al-Adha

Eid al-Adha () is the second and the larger of the two main holidays celebrated in Islam (the other being Eid al-Fitr). It honours the willingness of Ibrahim (Abraham) to sacrifice his son Ismail (Ishmael) as an act of obedience to Allah's c ...

. The cities of Mecca,

Medina, and

Jerusalem are home to the

three holiest sites in Islam, in descending order:

Masjid al-Haram

, native_name_lang = ar

, religious_affiliation = Islam

, image = Al-Haram mosque - Flickr - Al Jazeera English.jpg

, image_upright = 1.25

, caption = Aerial view of the Great Mosque of Mecca

, map ...

,

Al-Masjid an-Nabawi

Al-Masjid an-Nabawi (), known in English as the Prophet's Mosque, is a mosque built by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the city of Medina in the Al Madinah Province of Saudi Arabia. It was the second mosque built by Muhammad in Medina, after Qu ...

, and

Al-Aqsa Mosque

Al-Aqsa Mosque (, ), also known as Jami' Al-Aqsa () or as the Qibli Mosque ( ar, المصلى القبلي, translit=al-Muṣallā al-Qiblī, label=none), and also is a congregational mosque located in the Old City of Jerusalem. It is situate ...

, respectively.

Islam originated in the 7th century at

Jabal al-Nour

Jabal an-Nour ( ar, جَبَل ٱلنُّوْر, Jabal an-Nūr, lit=Mountain of the Light or 'Hill of the Illumination') is a mountain near Mecca in the Hejaz region of Saudi Arabia. The mountain houses the grotto or cave of Hira' ( ar, غَار ...

, a mountain peak near Mecca where

Muhammad's first revelation

Muhammad's first revelation was an event described in Islamic tradition as taking place in AD 610, during which the Islamic prophet Muhammad was visited by the angel Gabriel, who revealed to him the beginnings of what would later become the Qur'a ...

is said to have taken place. Through various

caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

s, the religion later

spread outside of Arabia shortly after Muhammad's death, and by the 8th century, the

Umayyad Caliphate had imposed Islamic rule from the

Iberian Peninsula in the west to the

Indus Valley in the east. The

Islamic Golden Age refers to the period traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century, during the reign of the

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

, when much of the

Muslim world was experiencing a

scientific

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence f ...

,

economic, and

cultural flourishing. Islamic scientific achievements encompassed a wide range of subject areas especially

medicine,

mathematics,

astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, galax ...

,

agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

as well as

physics,

pharmacology,

engineering and

optics. The expansion of the Muslim world involved

various states and caliphates as well as extensive trade and religious conversion as a result of

Islamic missionary activities ().

There are two major

Islamic denominations

Islamic schools and branches have different understandings of Islam. There are many different sects or denominations, schools of Islamic jurisprudence, and schools of Islamic theology, or ''ʿaqīdah'' (creed). Within Islamic groups themselves ...

:

Sunni Islam (85–90 percent)

[Denny, Frederick. 2010]

''Sunni Islam: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide''

Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 3. "Sunni Islam is the dominant division of the global Muslim community, and throughout history it has made up a substantial majority (85 to 90 percent) of that community." and

Shia Islam (10–15 percent);

combined, they make up a majority of the population in

49 countries. While

Sunni–Shia differences initially arose from disagreements over the

succession to Muhammad, they grew to cover a broader dimension both

theologically

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

and

juridically, with the divergence acquiring notable political significance.

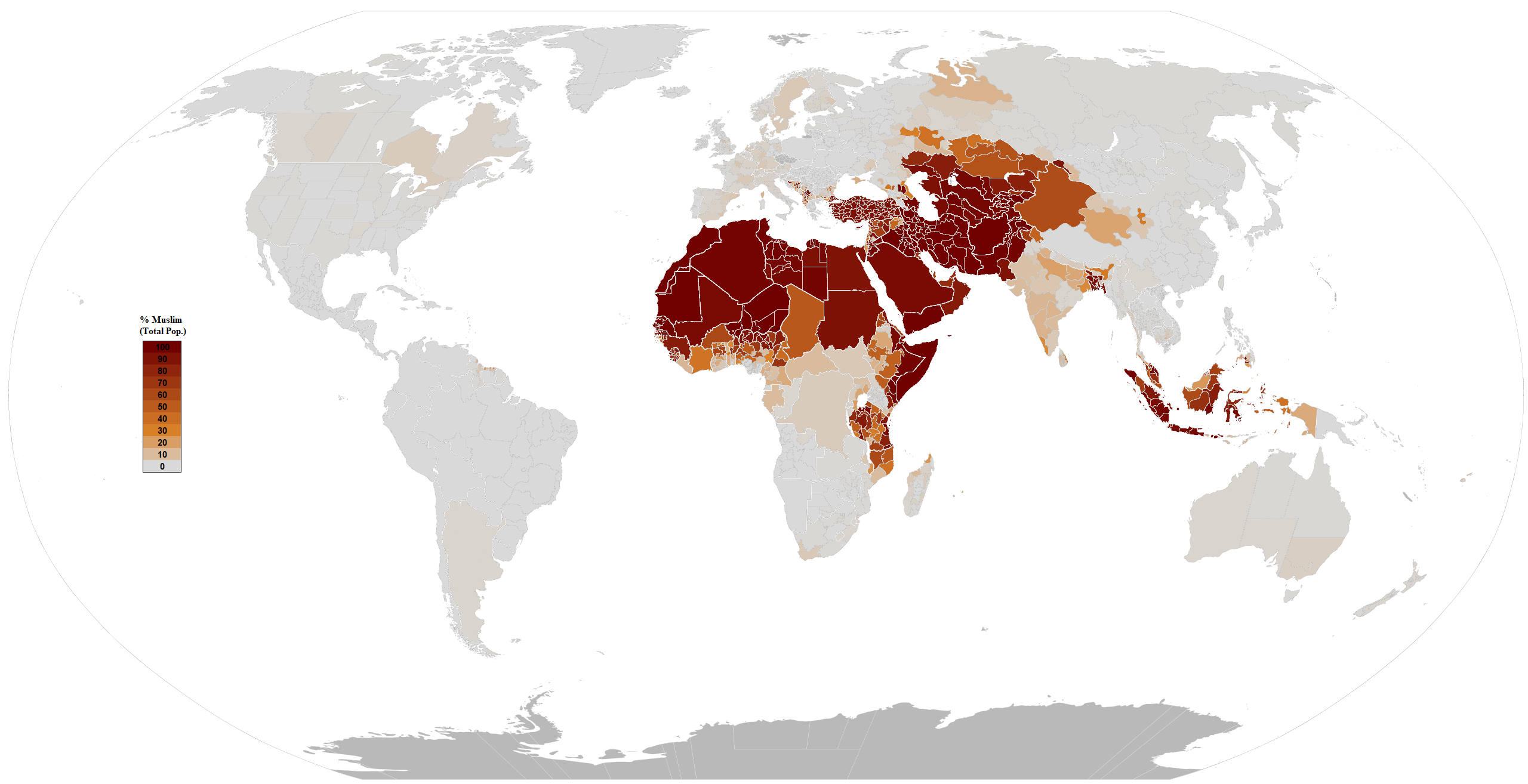

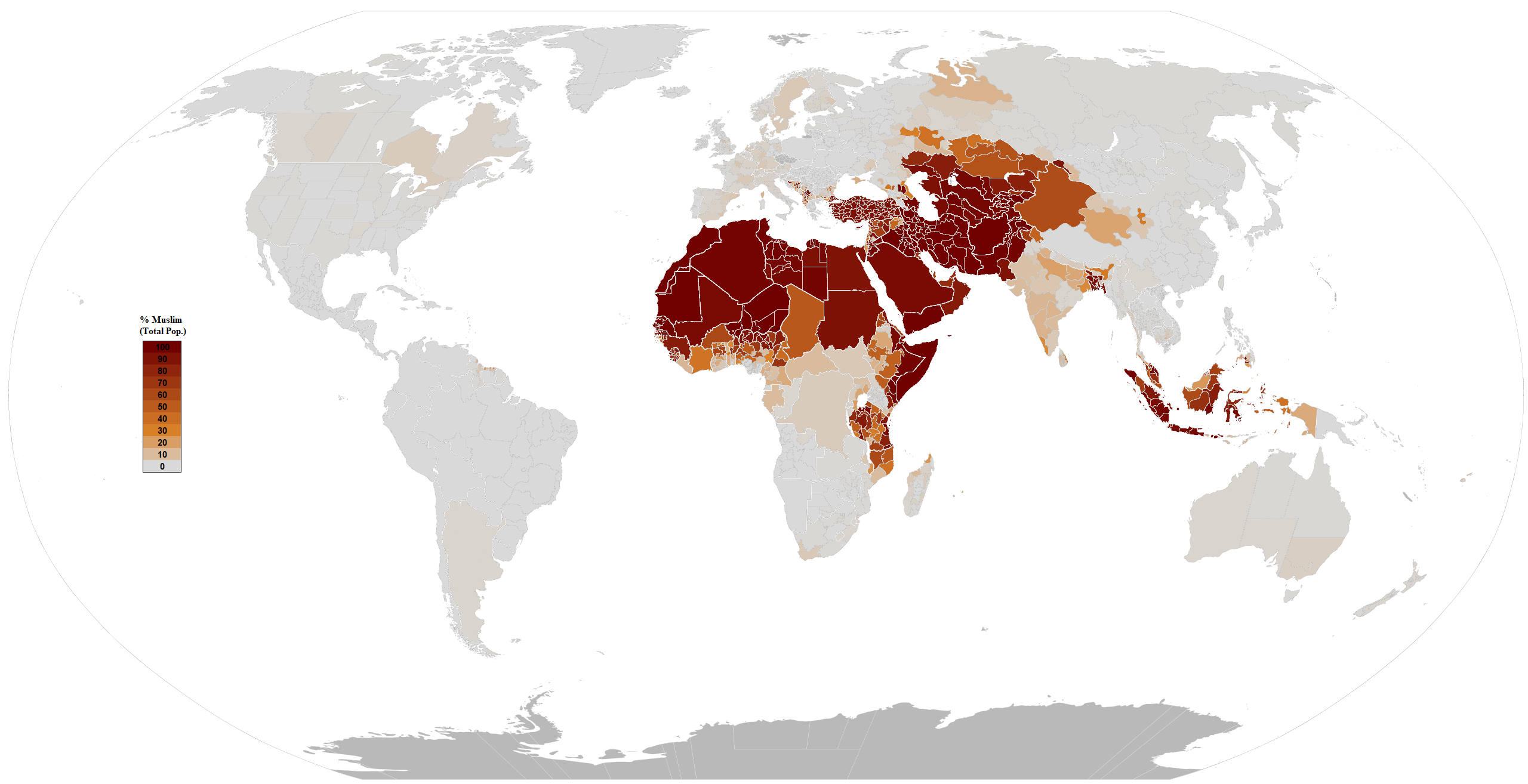

Approximately 12 percent of the world's Muslims live in

Indonesia, the most populous Muslim-majority country; percent live in

South Asia; 20 percent live in the

Middle East–North Africa; and 15 percent live in

sub-Saharan Africa.

Sizable Muslim communities are also present in the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with t ...

,

China, and

Europe.

Etymology

In Arabic, ''Islam'' ( ar, إسلام, lit=submission

o God

Oh God may refer to:

* An exclamation; similar to "oh no", "oh yes", "oh my", "aw goodness", "ah gosh", "ah gawd"; see interjection

''Oh, God!'' franchise

* ''Oh, God!'' (film) (1977 film) aka "Oh, God! 1"

* '' Oh, God! Book II'' (1980 film) aka ...

}) is the verbal noun of

Form IV originating from the verb (), from the

triliteral root

The roots of verbs and most nouns in the Semitic languages are characterized as a sequence of consonants or "radicals" (hence the term consonantal root). Such abstract consonantal roots are used in the formation of actual words by adding the vowe ...

(), which forms a large class of words mostly relating to concepts of submission, safeness, and peace. In a religious context, it refers to the total surrender to the will of

God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

.

A ''

Muslim'' (), the word for a follower of Islam, is the

active participle

In linguistics, a participle () (from Latin ' a "sharing, partaking") is a nonfinite verb form that has some of the characteristics and functions of both verbs and adjectives. More narrowly, ''participle'' has been defined as "a word derived from ...

of the same verb form, and means "submitter (to God)" or "one who surrenders (to God)". In the

Hadith of Gabriel

In Sunni Islam, the Hadith of Gabriel (also known as, ''Ḥadīth Jibrīl'') is a ''hadith'' of the Islamic prophet Muhammad (the last prophet of Islam) which expresses the religion of Islam in a concise manner. and it contains a summary of the co ...

, ''Islam'' is presented as one part of a triad that also includes (faith), and (excellence).

Islam itself was historically called

''Mohammedanism'' in the

English-speaking world. This term has fallen out of use and is sometimes said to be

offensive

Offensive may refer to:

* Offensive, the former name of the Dutch political party Socialist Alternative

* Offensive (military), an attack

* Offensive language

** Fighting words or insulting language, words that by their very utterance inflict inj ...

, as it suggests that a human being, rather than God, is central to Muslims' religion, parallel to

Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in Lu ...

in

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

. Some authors, however, continue to use the term ''Mohammedanism'' as a

technical term

Jargon is the specialized terminology associated with a particular field or area of activity. Jargon is normally employed in a particular communicative context and may not be well understood outside that context. The context is usually a particu ...

for the religious system as opposed to the

theological concept of Islam that exists within that system.

Articles of faith

The Islamic

creed (''

aqidah

''Aqidah'' ( (), plural ''ʿaqāʾid'', also rendered ''ʿaqīda'', ''aqeeda'', etc.) is an Islamic term of Arabic origin that literally means " creed". It is also called Islamic creed and Islamic theology.

''Aqidah'' go beyond concise state ...

'') requires belief in

six articles: God, angels, revelation, prophets, the

Day of Resurrection

In Islam, "the promise and threat" () of Judgment Day ( ar, یوم القيامة, Yawm al-qiyāmah, Day of Resurrection or ar, یوم الدین, italic=no, Yawm ad-din, Day of Judgement),

when "all bodies will be resurrected" from the dead, ...

, and the divine decree.

God

The central concept of Islam is ''

tawḥīd

Tawhid ( ar, , ', meaning "unification of God in Islam (Allāh)"; also romanized as ''Tawheed'', ''Tawhid'', ''Tauheed'' or ''Tevhid'') is the indivisible oneness concept of monotheism in Islam. Tawhid is the religion's central and single mo ...

'' ( ar, توحيد, link=no), the oneness of God. Usually thought of as a ''precise

monotheism'', but also

panentheistic in Islamic mystical teachings. God is seen as incomparable and without partners such as in the

Christian Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the ...

, and associating partners to God or attributing God's attributes to others is seen as

idolatory

Idolatry is the worship of a cult image or "idol" as though it were God. In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, the Baháʼí Faith, and Islam) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the ...

, called

''shirk''. God is seen as transcendent of creation and so is beyond comprehension. Thus, Muslims are not

iconodule

Iconodulism (also iconoduly or iconodulia) designates the religious service to icons (kissing and honourable veneration, incense, and candlelight). The term comes from Neoclassical Greek εἰκονόδουλος (''eikonodoulos'') (from el, ε ...

s and do not attribute forms to God. God is instead described and referred to by several

names or attributes, the most common being ''Ar-Rahmān'' () meaning "The Entirely Merciful," and ''Ar-Rahīm'' () meaning "The Especially Merciful" which are invoked at the beginning of most chapters of the Quran.

Islam teaches that the creation of everything in the

universe was brought into being by God's command as expressed by the wording, "

Be, and it is

"Be, and it is" ( ) is a phrase that occurs several times in the Quran, referring to creation by Allah. In Arabic the imperative verb ''be'' ('' kun'') is spelled with the letters ''kāf'' and '' nūn''.

Kun fa-yakūnu has its reference in the Qur ...

,"

[ Q2:117 ] and that the

purpose of existence is to worship God. He is viewed as a personal god

and there are no intermediaries, such as

clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, to contact God. Consciousness and awareness of God is referred to as

Taqwa

''Taqwa'' ( ar, تقوى '' / '')

is an Islamic term for being conscious and cognizant of God, of truth, "piety, fear of God."Nanji, Azim. "Islamic Ethics," in ''A Companion to Ethics'', Peter Singer. Oxford: Blackwells,n(1991), pp. 106– ...

. ''

Allāh

Allah (; ar, الله, translit=Allāh, ) is the common Arabic word for God. In the English language, the word generally refers to God in Islam. The word is thought to be derived by contraction from '' al- ilāh'', which means "the god", an ...

'' is a term with no

plural or

gender being ascribed to it and is also used by Muslims and Arabic-speaking Christians and Jews in reference to God, whereas ' () is a term used for a deity or a god in general. Other non-Arab Muslims might use different names as much as Allah, for instance in Turkish or in Persian.

Angels

Angels ( ar, ملك, link=no, ') are beings described in the Quran and hadith. They are described as created to worship God and also to serve other specific duties such as communicating

revelations from God, recording every person's actions, and taking a person's

soul at the time of death. They are described as being created variously from 'light' (

''nūr'') or 'fire' (''nār''). Islamic angels are often represented in

anthropomorphic forms combined with

supernatural images, such as wings, being of great size or wearing heavenly articles. Common characteristics for angels are their missing needs for bodily desires, such as eating and drinking. Some of them, such as

Gabriel and

Michael

Michael may refer to:

People

* Michael (given name), a given name

* Michael (surname), including a list of people with the surname Michael

Given name "Michael"

* Michael (archangel), ''first'' of God's archangels in the Jewish, Christian and ...

, are mentioned by name in the Quran. Angels play a significant role in the literature about the

Mi'raj

The Israʾ and Miʿraj ( ar, الإسراء والمعراج, ') are the two parts of a Night Journey that, according to Islam, the Islamic prophet Muhammad (570–632) took during a single night around the year 621 (1 BH – 0 BH). With ...

, where Muhammad encounters several angels during his journey through the heavens. Further angels have often been featured in

Islamic eschatology

Islamic eschatology ( ar, علم آخر الزمان في الإسلام, ) is a field of study in Islam concerning future events that would happen in the end times. It is primarily based on hypothesis and speculations based on sources from ...

,

theology and

philosophy.

Books

The Islamic holy books are the records that Muslims believe various prophets received from God through revelations, called ''

wahy''. Muslims believe that parts of the previously revealed scriptures, such as the ''

Tawrat

The Tawrat ( ar, ), also romanized as Tawrah or Taurat, is the Arabic-language name for the Torah within its context as an Islamic holy book believed by Muslims to have been given by God to the prophets and messengers amongst the Children of ...

'' (

Torah) and the ''

Injil

Injil ( ar, إنجيل, ʾInjīl, alternative spellings: ''Ingil'' or ''Injeel'') is the Arabic name for the Gospel of Jesus (Isa). This ''Injil'' is described by the Quran as one of the four Islamic holy books which was revealed by God, the o ...

'' (

Gospel), had become

distorted—either in interpretation, in text, or both,

while the Quran (lit. 'Recitation')

is viewed as the final, verbatim and unaltered word of God.

Muslims believe that the verses of the Quran were revealed to Muhammad by God, through the

archangel

Archangels () are the second lowest rank of angel in the hierarchy of angels. The word ''archangel'' itself is usually associated with the Abrahamic religions, but beings that are very similar to archangels are found in a number of other relig ...

Gabriel (''

Jibrīl''), on multiple occasions between 610 CE and 632, the year Muhammad died. While Muhammad was alive, these revelations were written down by his companions, although the prime method of transmission was orally through

memorization

Memorization is the process of committing something to memory. It is a mental process undertaken in order to store in memory for later recall visual, auditory, or tactical information.

The scientific study of memory is part of cognitive neurosc ...

.

The Quran is divided into 114 chapters (

suras

The Abhira kingdom in the Mahabharata is either of two kingdoms near the Sarasvati river.

They were dominated by the Abhiras, sometimes referred to as Surabhira also, combining both Sura and Abhira kingdoms. Modern day Abhira territory lies wit ...

) which combined contain 6,236 verses (''

āyāt''). The chronologically earlier chapters, revealed at

Mecca, are concerned primarily with spiritual topics while the later

Medinan chapters discuss more social and legal issues relevant to the Muslim community.

[

"The word ''Quran'' was invented and first used in the Qurʼan itself. There are two different theories about this term and its formation."] Muslim jurists consult the ''hadith'' ('accounts'), or the written record of Prophet Muhammad's life, to both supplement the Quran and assist with its interpretation. The science of Quranic commentary and exegesis is known as ''

tafsir''. The set of rules governing proper

elocution of recitation is called

tajwid

In the context of the recitation of the Quran, ''tajwīd'' ( ar, تجويد ', , 'elocution') is a set of rules for the correct pronunciation of the letters with all their qualities and applying the various traditional methods of recitation ('' ...

. In addition to its religious significance, it is widely regarded as the finest work in

Arabic literature

Arabic literature ( ar, الأدب العربي / ALA-LC: ''al-Adab al-‘Arabī'') is the writing, both as prose and poetry, produced by writers in the Arabic language. The Arabic word used for literature is '' Adab'', which is derived from a ...

, and has influenced art and the Arabic language.

Prophets

Prophets (Arabic: ar, أنبياء, label=none, translit=anbiyāʾ) are believed to have been chosen by God to receive and preach a divine message. Additionally, a prophet delivering a new book to a nation is called a ''rasul'' ( ar, رسول, label=none, translit=rasūl), meaning "messenger". Muslims believe prophets are human and not divine. All of the prophets are said to have preached the same basic message of Islam – submission to the will of God – to various nations in the past and that this accounts for many similarities among religions. The Quran

recounts the names of numerous figures considered

prophets in Islam, including

Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as ...

,

Noah,

Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jews ...

,

Moses and

Jesus, among others.

Muslims believe that God sent Muhammad as the final prophet ("

Seal of the prophets") to convey the completed message of Islam. In Islam, the "normative" example of Muhammad's life is called the

sunnah (literally "trodden path"). Muslims are encouraged to emulate Muhammad's moral behaviors in their daily lives, and the Sunnah is seen as crucial to guiding interpretation of the Quran. This example is preserved in traditions known as

hadith, which are accounts of his words, actions, and personal characteristics.

Hadith Qudsi is a sub-category of hadith, regarded as God's verbatim words quoted by Muhammad that are not part of the Quran. A hadith involves two elements: a chain of narrators, called

''sanad'', and the actual wording, called ''

matn

Hadith studies ( ar, علم الحديث ''ʻilm al-ḥadīth'' "science of hadith", also science of hadith, or science of hadith criticism or hadith criticism)

consists of several religious scholarly disciplines used by Muslim scholars in th ...

''. There are various methodologies to classify the authenticity of hadiths, with the commonly used grading being: "authentic" or "correct" ( ar, صحيح, links=no, translit=

ṣaḥīḥ, label=none); "good", ''hasan'' ( ar, حسن, links=no, label=none, translit=

ḥasan); or "weak" ( ar, ضعيف, label=none, translit=

ḍaʻīf), among others. The ''

Kutub al-Sittah'' are a collection of six books, regarded as the most authentic reports in

Sunni Islam. Among them is ''

Sahih al-Bukhari'', often considered by Sunnis to be one of the most

authentic

Authenticity or authentic may refer to:

* Authentication, the act of confirming the truth of an attribute

Arts and entertainment

* Authenticity in art, ways in which a work of art or an artistic performance may be considered authentic

Music

* A ...

sources after the Quran.

[ al-Rahman, Aisha Abd, ed. 1990. '' Muqaddimah Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ''. Cairo: Dar al-Ma'arif, 1990. pp. 160–69] Another famous source of hadiths is known as ''

The Four Books

''The Four Books'' ( ar-at, ٱلْكُتُب ٱلْأَرْبَعَة, '), or ''The Four Principles'' (''al-Uṣūl al-Arbaʿah''), is a Twelver Shia term referring to their four best-known ''hadith'' collections:

Most Shi'a Muslims use d ...

'', which Shias consider as the most authentic hadith reference.

Resurrection and judgment

Belief in the "Day of Resurrection" or ''

Yawm al-Qiyāmah

In Islam, "the promise and threat" () of Judgment Day ( ar, یوم القيامة, Yawm al-qiyāmah, Day of Resurrection or ar, یوم الدین, italic=no, Yawm ad-din, Day of Judgement),

when "all bodies will be resurrected" from the dead, an ...

'' ( ar, يوم القيامة, link=no), is also crucial for Muslims. It is believed that the time of ''Qiyāmah'' is preordained by God but unknown to man. The Quran and the hadith, as well as in the commentaries of

scholars

A scholar is a person who pursues academic and intellectual activities, particularly academics who apply their intellectualism into expertise in an area of study. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researcher ...

, describe the trials and

tribulations preceding and during the ''Qiyāmah''. The Quran emphasizes

bodily resurrection, a break from the

pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia ( ar, شبه الجزيرة العربية قبل الإسلام) refers to the Arabian Peninsula before the emergence of Islam in 610 CE.

Some of the settled communities developed into distinctive civilizations. Information ...

n understanding of death.

On Yawm al-Qiyāmah, Muslims believe all humankind will be judged by their good and bad deeds and consigned to ''

Jannah

In Islam, Jannah ( ar, جَنّة, janna, pl. ''jannāt'',lit. "paradise, garden", is the final abode of the righteous. According to one count, the word appears 147 times in the Quran. Belief in the afterlife is one of the six articles of f ...

'' (paradise) or ''

Jahannam'' (hell). The Quran in

Surat al-Zalzalah

Al-Zalzalah ( ar, الزلزلة, ''al-zalzalah'', "The Quake") is the 99th chapter (surah) of the Qur'an, composed of 8 ayat or verses. Although it is usually classified as a Medinan surah, the period during which the surah was revealed is no ...

describes this as: "So whoever does an atom's weight of good will see it. And whoever does an atom's weight of evil will see it." The Quran

lists several sins that can condemn a person to

hell

In religion and folklore, hell is a location in the afterlife in which evil souls are subjected to punitive suffering, most often through torture, as eternal punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hells ...

, such as

disbelief in God ( ar, كفر, translit=kufr, label=none), and dishonesty. However, the Quran makes it clear that God will forgive the

sins

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

of those who repent if he wishes. Good deeds, like charity, prayer, and compassion towards animals, will be rewarded with entry to heaven. Muslims view heaven as a place of joy and blessings, with Quranic references describing its features. Mystical traditions in Islam place these heavenly delights in the context of an ecstatic awareness of God. ''Yawm al-Qiyāmah'' is also identified in the Quran as ''Yawm ad-Dīn'' ( "Day of Religion");

[;] ''as-Sāʿah'' ( "the Last Hour");

[;] and ''

al-Qāriʿah'' ( "The Clatterer");

Divine predestination

The concept of

divine

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.[divine< ...](_blank)

decree and

destiny in Islam ( ar, القضاء والقدر, ') means that every matter, good or bad, is believed to have been decreed by God. ''Al-qadar'', meaning "power", derives from a root that means "to measure" or "calculating". Muslims often express this belief in divine destiny with the phrase

"Insha-Allah" meaning "if God wills" when speaking on future events. In addition to loss, gain is also seen as a test of believers – whether they would still recognize that the gain originates only from God.

Acts of worship

There are five obligatory acts of worship – the

Shahada declaration of faith, the five daily prayers, the

Zakat

Zakat ( ar, زكاة; , "that which purifies", also Zakat al-mal , "zakat on wealth", or Zakah) is a form of almsgiving, often collected by the Muslim Ummah. It is considered in Islam as a religious obligation, and by Quranic ranking, is n ...

alms-giving,

fasting during Ramadan

During the entire month of Ramadan, Muslims are obligated to fast ( ar, صوم, ''sawm;'' Persian: روزہ, ''rozeh''), every day from dawn to sunset (or from dawn to night according to some scholars). Fasting requires the abstinence from sex ...

and the

Hajj

The Hajj (; ar, حَجّ '; sometimes also spelled Hadj, Hadji or Haj in English) is an annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the holiest city for Muslims. Hajj is a mandatory religious duty for Muslims that must be carried o ...

pilgrimage – collectively known as "The Pillars of Islam" (''Arkān al-Islām'').

Apart from these, Muslims also perform other supplemental religious acts.

Testimony

The

''shahadah'', is an

oath

Traditionally an oath (from Anglo-Saxon ', also called plight) is either a statement of fact or a promise taken by a sacrality as a sign of verity. A common legal substitute for those who conscientiously object to making sacred oaths is to gi ...

declaring belief in Islam. The expanded statement is "" ( ar, أشهد أن لا إله إلا الله وأشهد أن محمداً رسول الله, label=none), or, "I testify that there is no

deity except

God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

and I testify that Muhammad is the messenger of God." Islam is sometimes argued to have a very simple creed with the shahada being the premise for the rest of the religion. Non-Muslims wishing to

convert to Islam are required to recite the shahada in front of witnesses.

Prayer

Prayer in Islam, called

as-salah or aṣ-ṣalāt ( ar, الصلاة, link=no), is seen as a personal communication with God and consists of repeating units called

rakat that include

bowing

Bowing (also called stooping) is the act of lowering the torso and head as a social gesture in direction to another person or symbol. It is most prominent in Asian cultures but it is also typical of nobility and aristocracy in many European cou ...

and

prostrating to God. Performing prayers five times a day is compulsory. The prayers are recited in the Arabic language and consist of verses from the Quran. The prayers are done in direction of the

Ka'bah. Salah requires ritual purity, which involves ''

wudu'' (ritual wash) or occasionally, such as for new converts, ''

ghusl'' (full body ritual wash). The means used to signal the prayer time is a vocal call called the ''

adhan

Adhan ( ar, أَذَان ; also variously transliterated as athan, adhane (in French), azan/azaan (in South Asia), adzan (in Southeast Asia), and ezan (in Turkish), among other languages) is the Islamic call to public prayer ( salah) in a mo ...

''.

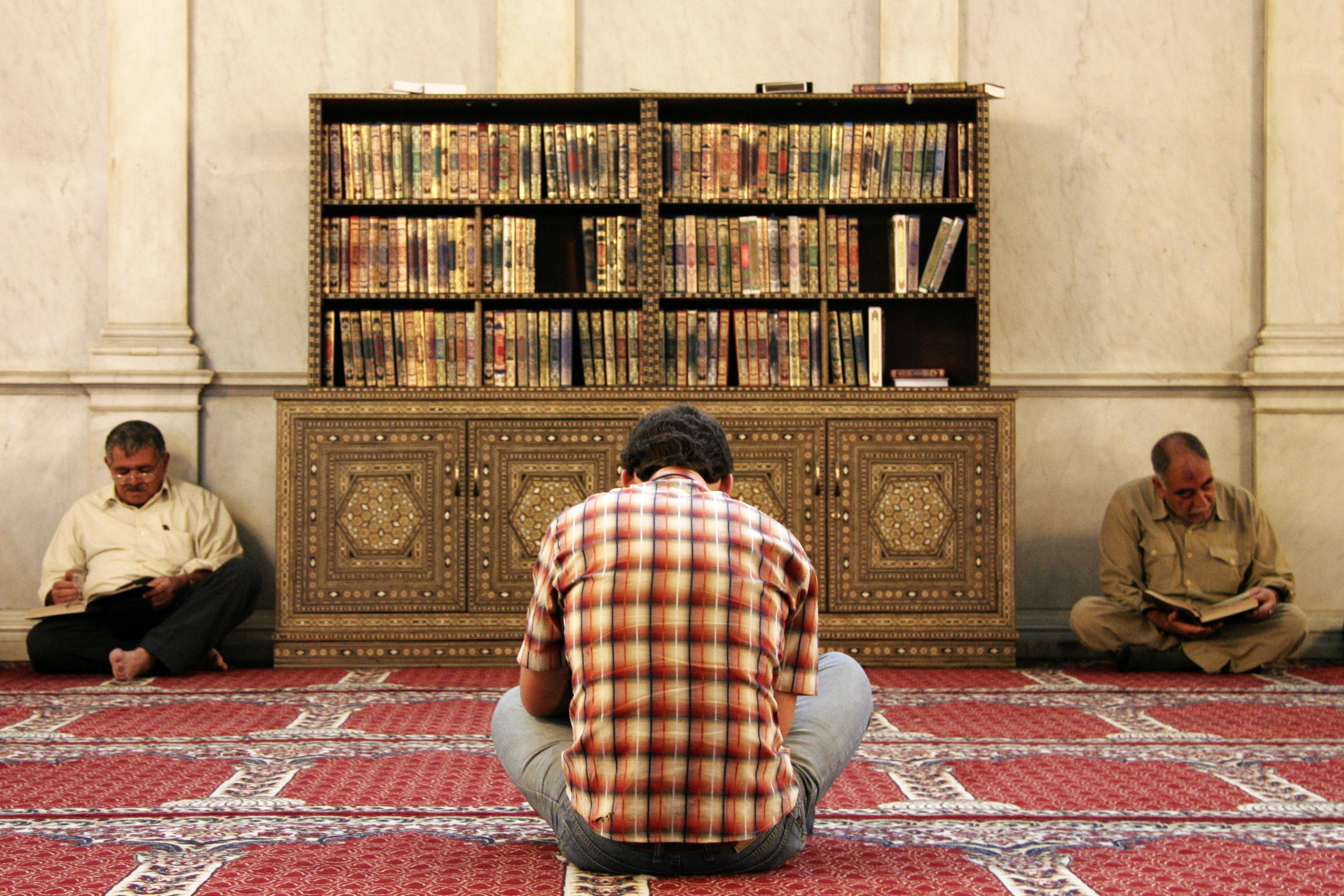

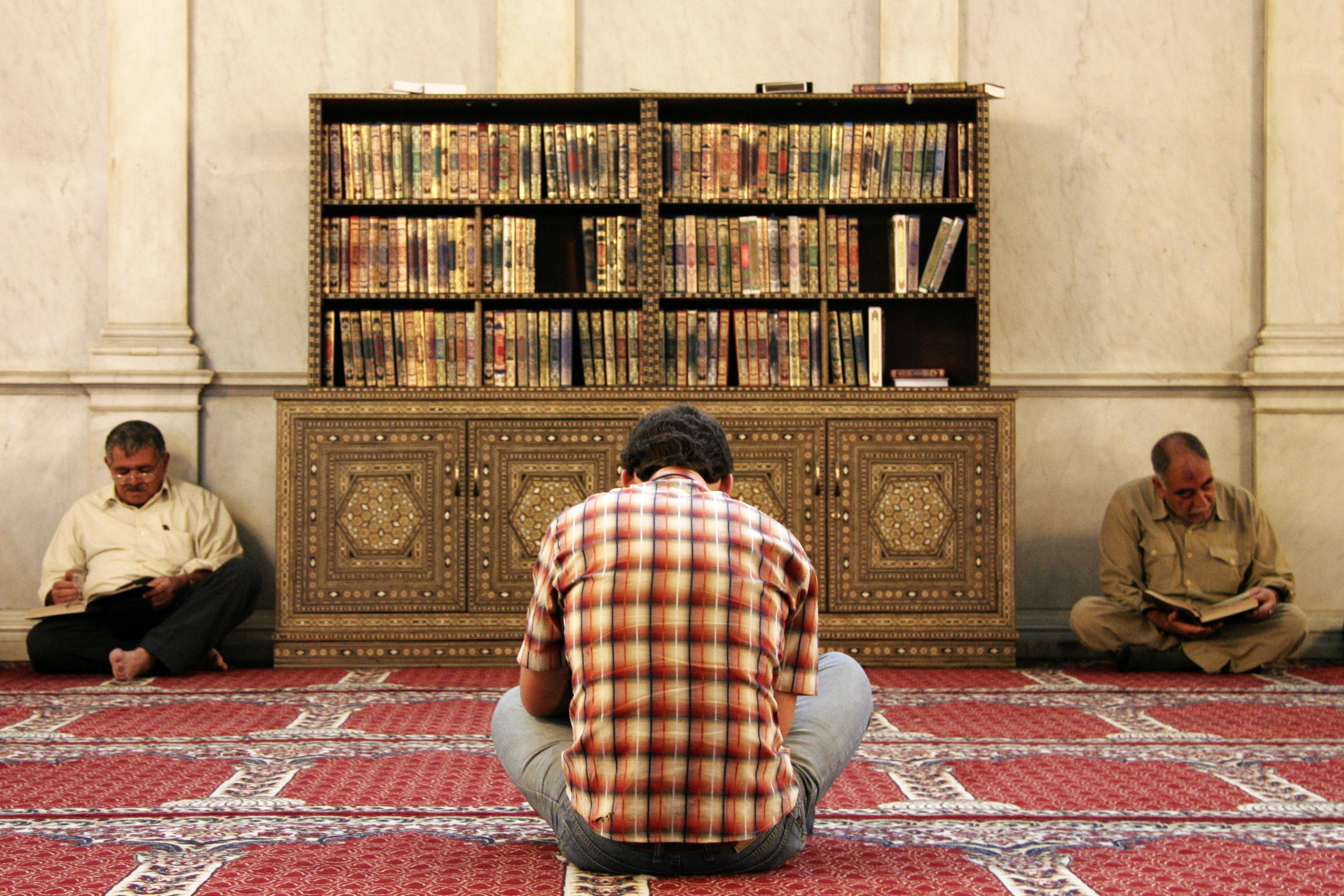

A

mosque is a

place of worship for Muslims, who often refer to it by its Arabic name masjid. Although the primary purpose of the mosque is to serve as a place of prayer, it is also important to the

Muslim community

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

as a place to meet and study with the

Masjid an-Nabawi ("Prophetic Mosque") in Medina,

Saudi Arabia, having also served as a shelter for the poor.

Minaret

A minaret (; ar, منارة, translit=manāra, or ar, مِئْذَنة, translit=miʾḏana, links=no; tr, minare; fa, گلدسته, translit=goldaste) is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generall ...

s are towers used to call the

adhan

Adhan ( ar, أَذَان ; also variously transliterated as athan, adhane (in French), azan/azaan (in South Asia), adzan (in Southeast Asia), and ezan (in Turkish), among other languages) is the Islamic call to public prayer ( salah) in a mo ...

.

Charity

Zakāt

Zakat ( ar, زكاة; , "that which purifies", also Zakat al-mal , "zakat on wealth", or Zakah) is a form of almsgiving, often collected by the Muslim Ummah. It is considered in Islam as a religious obligation, and by Quranic ranking, is ne ...

(

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

: ar, زكاة, translit=zakāh, label=none) is a means of

welfare in a Muslim society, characterized by the giving of a fixed portion (2.5% annually)

[Ahmed, Medani, and Sebastian Gianci. "Zakat." p. 479 in ''Encyclopedia of Taxation and Tax Policy''.] of

accumulated wealth by those who can afford it to help the poor or needy, such as for freeing captives, those in

debt

Debt is an obligation that requires one party, the debtor, to pay money or other agreed-upon value to another party, the creditor. Debt is a deferred payment, or series of payments, which differentiates it from an immediate purchase. The d ...

, or for (stranded) travellers, and for those employed to collect zakat. It is considered a religious obligation that the well-off owe to the needy because their wealth is seen as a "trust from God's bounty" and is seen as a "purification" of one's excess wealth. The total annual value contributed due to zakat is 15 times greater then global humanitarian aid donations, using conservative estimates. ''Sadaqah'', as opposed to Zakat, is a much encouraged

supererogatory

Supererogation (Late Latin: ''supererogatio'' "payment beyond what is needed or asked", from ''super'' "beyond" and ''erogare'' "to pay out, expend", itself from ''ex'' "out" and ''rogare'' "to ask") is the performance of more than is asked for; ...

charity. A

waqf

A waqf ( ar, وَقْف; ), also known as hubous () or '' mortmain'' property is an inalienable charitable endowment under Islamic law. It typically involves donating a building, plot of land or other assets for Muslim religious or charitabl ...

is a perpetual

charitable trust, which financed hospitals and schools in Muslim societies.

Fasting

During the month of

Ramadan, it is obligatory for Muslims to fast. The Ramadan fast (

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

: ar, صوم, translit=ṣawm, label=none) precludes food and drink, as well as other forms of consumption, such as smoking, and is performed from dawn to sunset. The fast is to encourage a feeling of nearness to God by restraining oneself for God's sake from what is otherwise permissible and to think of the needy. In addition, there are other days when fasting is supererogatory.

Pilgrimage

The obligatory Islamic

pilgrimage, called the "" ( ar, حج, link=no), is to be done at least once a lifetime by every Muslim with the means to do so during the

Islamic month

The Hijri calendar ( ar, ٱلتَّقْوِيم ٱلْهِجْرِيّ, translit=al-taqwīm al-hijrī), also known in English as the Muslim calendar and Islamic calendar, is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 lunar months in a year of 354 o ...

of

Dhu al-Hijjah. Rituals of the Hajj mostly imitate the story of the family of

Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jews ...

. Pilgrims spend a day and a night on the plains of

Mina, then a day praying and worshipping in the plain of

Mount Arafat

Mount Arafat ( ar, جَبَل عَرَفَات, translit=Jabal ʿArafāt), and by its other Arabic name, (), is a granodiorite hill about southeast of Mecca, in the province of the same name in Saudi Arabia. The mountain is approximately ...

, then spending a night on the plain of

Muzdalifah

Muzdalifah ( ar, مُزْدَلِفَة) is an open and level area near Mecca in the Hejazi region of Saudi Arabia that is associated with the ("Pilgrimage"). It lies just southeast of Mina, on the route between Mina and Arafat.

Pilgrimage

...

; then moving to

Jamarat, symbolically

stoning the Devil, then going to the city of

Mecca and walking seven times around the

Kaaba, which Muslims believe Abraham built as a place of worship, then walking seven times between

Mount Safa and Mount Marwah recounting the steps of Abraham's wife,

Hagar, while she was looking for water for her baby

Ishmael in the desert before Mecca developed into a settlement. All Muslim men should wear only two simple white unstitched pieces of cloth called

ihram, intended to bring continuity through generations and uniformity among pilgrims despite class or origin. Another form of pilgrimage, ''umrah'', is supererogatory and can be undertaken at any time of the year.

Medina is also a site of Islamic pilgrimage and

Jerusalem, the city of many Islamic prophets, contains the

Al-Aqsa Mosque

Al-Aqsa Mosque (, ), also known as Jami' Al-Aqsa () or as the Qibli Mosque ( ar, المصلى القبلي, translit=al-Muṣallā al-Qiblī, label=none), and also is a congregational mosque located in the Old City of Jerusalem. It is situate ...

, which used to be the

direction of prayer

Prayer in a certain direction is characteristic of many world religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, Islam and the Baháʼí Faith.

Judaism

Jews traditionally Jewish prayer, pray in the direction of Jerusalem, where the "presence of the tra ...

before Mecca.

Quranic recitation and memorization

Muslims recite and memorize the whole or parts of the Quran as acts of virtue. Reciting the Quran with elocution (''tajwid'') has been described as an excellent act of worship. Pious Muslims recite the whole Quran during the month of Ramadan. In Muslim societies, any social program generally begins with the recitation of the Quran. One who has memorized the whole Quran is called a hafiz ("memorizer") who, it is said, will be able to intercede for ten people on the Last Judgment Day. Apart from this, almost every Muslim memorizes some portion of the Quran because they need to recite it during their prayers.

Supplication and remembrance

Supplication to God, called in Arabic ''ad-duʿāʾ'' ( ar, الدعاء ) has its own etiquette such as

raising hands as if begging or invoking with an extended index finger.

Remebrance of God ( ar, ذكر, translit=Dhikr', label=none) refers to phrases repeated referencing God. Commonly, this includes Tahmid, declaring

praise be due to God ( ar, الحمد لله, translit=al-Ḥamdu lillāh, label=none) during prayer or when feeling thankful,

Tasbih, declaring glory to God during prayer or when in awe of something and saying '

in the name of God' (, ) before starting an act such as eating.

History

Muhammad (610–632)

Born in

Mecca in 570, Muhammad was orphaned early in life. New trade routes rapidly transformed Meccan society from a semi-bedouin society to a commercial urban society, leaving out weaker segments of society without protection. He acquired the nickname "

trustworthy

Trust is the willingness of one party (the trustor) to become vulnerable to another party (the trustee) on the presumption that the trustee will act in ways that benefit the trustor. In addition, the trustor does not have control over the acti ...

" ( ar, الامين), and was sought after as a bank to safeguard valuables and an impartial arbitrator. Affected by the ills of society and after becoming financially secure through marrying his employer, the businesswoman

Khadija

Khadija, Khadeeja or Khadijah ( ar, خديجة, Khadīja) is an Arabic feminine given name, the name of Khadija bint Khuwaylid, first wife of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. In 1995, it was one of the three most popular Arabic feminine names in th ...

, he began retreating to a

cave

A cave or cavern is a natural void in the ground, specifically a space large enough for a human to enter. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. The word ''cave'' can refer to smaller openings such as se ...

to contemplate. During the last 22 years of his life, beginning at age 40 in 610

CE, Muhammad reported receiving revelations from God, conveyed to him through the

archangel Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብር� ...

, thus becoming the seal of the prophets sent to mankind, according to Islamic tradition.

During this time,

while in Mecca, Muhammad preached first in secret and then in public, imploring his listeners to abandon

polytheism

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the ...

and worship one God. Many early converts to Islam were women, the poor, foreigners, and slaves like the first

muezzin Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi. The Meccan elite profited from the pilgrimages to the idols of the Kaaba and felt Muhammad was destabilizing their social order by preaching about one God, and that in the process he gave questionable ideas to the poor and slaves. Muhammad, who was accused of being a poet, a madman or possessed, presented the

challenge of the Quran

In Islam, ''’i‘jāz'' ( ar, اَلْإِعْجَازُ, al-’i‘jāz) or inimitability of the Qur’ān is the doctrine which holds that the Qur’ān has a miraculous quality, both in content and in form, that no human speech can match. ...

to imitate the like of the Quran in order to disprove him. The Meccan authorities persecuted Muhammad and his followers, including a boycott and banishment of Muhammad and his clan to starve them into withdrawing their protection of him. This resulted in the

Migration to Abyssinia

The migration to Abyssinia ( ar, الهجرة إلى الحبشة, translit=al-hijra ʾilā al-habaša), also known as the First Hijra ( ar, الهجرة الأولى, translit=al-hijrat al'uwlaa, label=none), was an episode in the early histor ...

of some Muslims (to the

Aksumite Empire

The Kingdom of Aksum ( gez, መንግሥተ አክሱም, ), also known as the Kingdom of Axum or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom centered in Northeast Africa and South Arabia from Classical antiquity to the Middle Ages. Based primarily in wh ...

).

After 12 years of the

persecution of Muslims by the Meccans

In the early days of Islam at Mecca, the new Muslims were often subjected to abuse and persecution. The persecution lasted for twelve years beginning from the advent of Islam to Hijrah. Muhammad preached Islam secretly for three years. Then, he o ...

, Muhammad and his

companions performed the ''

Hijra

Hijra, Hijrah, Hegira, Hejira, Hijrat or Hijri may refer to:

Islam

* Hijrah (often written as ''Hejira'' in older texts), the migration of Muhammad from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE

* Migration to Abyssinia or First Hegira, of Muhammad's followers ...

'' ("emigration") in 622 to the city of Yathrib (current-day Medina). There, with the Medinan converts (the ''

Ansar'') and the Meccan migrants (the ''

Muhajirun''),

Muhammad in Medina

The Islamic prophet Muhammad came to the city of Medina following the migration of his followers in what is known as the ''Hijrah'' (migration to Medina) in 622. He had been invited to Medina by city leaders to adjudicate disputes between clans f ...

established his

political and religious authority. The

Constitution of Medina

The Constitution of Medina (, ''Dustūr al-Madīna''), also known as the Charter of Medina ( ar, صحيفة المدينة, ''Ṣaḥīfat al-Madīnah''; or: , ''Mīthāq al-Madina'' "Covenant of Medina"), is the modern name given to a document be ...

was signed by all the tribes of Medina establishing among the Muslim and non-Muslim communities religious freedoms and freedom to use their own laws and agreeing to bar weapons from Medina and to defend it from external threats. Meccan forces and their allies lost against the Muslims at the

Battle of Badr

The Battle of Badr ( ar, غَزْوَةُ بَدِرْ ), also referred to as The Day of the Criterion (, ) in the Qur'an and by Muslims, was fought on 13 March 624 CE (17 Ramadan, 2 AH), near the present-day city of Badr, Al Madinah Provinc ...

in 624 and then fought an inconclusive battle in the

Battle of Uhud

The Battle of Uhud ( ar, غَزْوَة أُحُد, ) was fought on Saturday, 23 March 625 AD (7 Shawwal, 3 AH), in the valley north of Mount Uhud.Watt (1974) p. 136. The Qurayshi Meccans, led by Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, commanded an army of 3,000 m ...

before unsuccessfully besieging Medina in the

Battle of the Trench

The Battle of the Trench ( ar, غزوة الخندق, Ghazwat al-Khandaq), also known as the Battle of Khandaq ( ar, معركة الخندق, Ma’rakah al-Khandaq) and the Battle of the Confederates ( ar, غزوة الاحزاب, Ghazwat al- ...

(March–April 627). In 628, the

Treaty of Hudaybiyyah was signed between Mecca and the Muslims, but it was broken by Mecca two years later. As more tribes converted to Islam, Meccan trade routes were cut off by the Muslims. By 629 Muhammad was victorious in the nearly bloodless

conquest of Mecca

The Conquest of Mecca ( ar, فتح مكة , translit=Fatḥ Makkah) was the capture of the town of Mecca by Muslims led by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in December 629 or January 630 AD ( Julian), 10–20 Ramadan, 8 AH. The conquest marked t ...

, and by the time of his death in 632 (at age 62) he had united the

tribes of Arabia into a single religious

polity. Muhammad's closest companions, such as

Abu Hureyrah

Abu Hurayra ( ar, أبو هريرة, translit=Abū Hurayra; –681) was one of the companions of Islamic prophet Muhammad and, according to Sunni Islam, the most prolific narrator of hadith.

He was known by the '' kunyah'' Abu Hurayrah "Father ...

, recorded and compiled what would constitute the hadith.

Caliphate and civil strife (632–750)

Muhammad died in 632 and the first successors, called

Caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

s –

Abu Bakr

Abu Bakr Abdallah ibn Uthman Abi Quhafa (; – 23 August 634) was the senior companion and was, through his daughter Aisha, a father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 ...

,

Umar,

Uthman ibn al-Affan

Uthman ibn Affan ( ar, عثمان بن عفان, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān; – 17 June 656), also spelled by Colloquial Arabic, Turkish and Persian rendering Osman, was a second cousin, son-in-law and notable companion of the Islamic prop ...

,

Ali ibn Abi Talib

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam. ...

and sometimes

Hasan ibn Ali – are known in Sunni Islam as ''al-khulafā' ar-rāshidūn'' ("

Rightly Guided Caliphs

, image = تخطيط كلمة الخلفاء الراشدون.png

, caption = Calligraphic representation of Rashidun Caliphs

, birth_place = Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia present-day Saudi Arabia

, known_for = Companions of t ...

"). Some tribes left Islam and rebelled under leaders who declared themselves new prophets but were crushed by Abu Bakr in the

Ridda wars. Local populations of Jews and indigenous Christians, persecuted as religious minorities and heretics and taxed heavily, often helped Muslims take over their lands, resulting in rapid expansion of the caliphate into the

Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

and

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

empires.

Uthman

was elected in 644 and his assassination by rebels led to Ali being elected the next Caliph. In the

First Civil War, Muhammad's widow,

Aisha

Aisha ( ar, , translit=ʿĀʾisha bint Abī Bakr; , also , ; ) was Muhammad's third and youngest wife. In Islamic writings, her name is thus often prefixed by the title "Mother of the Believers" ( ar, links=no, , ʾumm al- muʾminīn), referr ...

, raised an army against Ali, asking to avenge the death of Uthman, but was defeated at the

Battle of the Camel

The Battle of the Camel, also known as the Battle of Jamel or the Battle of Basra, took place outside of Basra, Iraq, in 36 AH (656 CE). The battle was fought between the army of the fourth caliph Ali, on one side, and the rebel army led by ...

. Ali attempted to remove the governor of Syria, Mu'awiya, who was seen as corrupt. Mu'awiya then declared war on Ali and was defeated in the

Battle of Siffin

The Battle of Siffin was fought in 657 CE (37 AH) between Ali ibn Abi Talib, the fourth of the Rashidun Caliphs and the first Shia Imam, and Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, the rebellious governor of Syria. The battle is named after its location S ...

. Ali's decision to arbitrate angered the

Kharijites, an extremist sect, who felt that by not fighting a sinner, Ali became a sinner as well. The Kharijites rebelled and were defeated in the

Battle of Nahrawan

The Battle of Nahrawan ( ar, معركة النهروان, Ma'rakat an-Nahrawān) was fought between the army of Caliph Ali and the rebel group Kharijites in July 658 CE (Safar 38 AH). They used to be a group of pious allies of Ali during the ...

but a Kharijite assassin later killed Ali. Ali's son, Hasan ibn Ali, was elected Caliph and signed a

peace treaty to avoid further fighting, abdicating to

Mu'awiyah

Mu'awiya I ( ar, معاوية بن أبي سفيان, Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān; –April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the deat ...

in return for Mu'awiyah not appointing a successor. Mu'awiyah began the

Umayyad dynasty with the appointment of his son

Yazid I

Yazid ibn Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan ( ar, يزيد بن معاوية بن أبي سفيان, Yazīd ibn Muʿāwiya ibn ʾAbī Sufyān; 64611 November 683), commonly known as Yazid I, was the second caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate. He ruled from ...

as successor, sparking the

Second Civil War. During the

Battle of Karbala,

Husayn ibn Ali was killed by Yazid's forces; the event has been

annually commemorated by Shia ever since. Sunnis, led by

Ibn al-Zubayr, opposed to a dynastic caliphate were defeated in the

Siege of Mecca. These disputes over leadership would give rise to the

Sunni-

Shia schism,

with the Shia believing leadership belongs to Muhammad's family through Ali, called the

ahl al-bayt

Ahl al-Bayt ( ar, أَهْل ٱلْبَيْت, ) refers to the family of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, but the term has also been extended in Sunni Islam to apply to all descendants of the Banu Hashim (Muhammad's clan) and even to all Muslims. In ...

.

Quietist forms of Kharijites led to the third largest denomination in Islam,

Ibadiyya

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

Ibadism emerged around 60 years after the Islamic prophet Muhammad's death in 632 AD as a moderate sc ...

.

Abu Bakr's leadership oversaw the beginning of the compilation of the Qur'an. The Caliph

Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz

Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz ( ar, عمر بن عبد العزيز, ʿUmar ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz; 2 November 680 – ), commonly known as Umar II (), was the eighth Umayyad caliph. He made various significant contributions and reforms to the society, an ...

set up the committee,

The Seven Fuqaha of Medina

The Seven Fuqaha of Medina is the title of seven Muslim scholars who were the largest contributors as to the transmission of hadith and making of fatwas in Medina during the 2nd century AH: The Four Imams by Muhammad Abu Zahrahchapter on Imam Ma ...

, and

Malik ibn Anas wrote one of the earliest books on Islamic jurisprudence, the ''

Muwatta'', as a consensus of the opinion of those jurists. The

Kharijites believed there is no compromised middle ground between good and evil, and any Muslim who commits a grave sin becomes an unbeliever. The term is also used to refer to later groups such as

Isis. The

Murji'ah

Murji'ah ( ar, المرجئة, English: "Those Who Postpone"), also known as Murji'as or Murji'ites, were an early Islamic sect. Murji'ah held the opinion that God alone has the right to judge whether or not a Muslim has become an apostate. Conseq ...

taught that people's righteousness could be judged by God alone. Therefore, wrongdoers might be considered misguided, but not denounced as unbelievers. This attitude came to prevail into mainstream Islamic beliefs.

The Umayyad dynasty conquered the

Maghreb, the

Iberian Peninsula,

Narbonnese Gaul and

Sindh. The Umayyads struggled with a lack of legitimacy and relied on a heavily patronized military. Since the jizya tax was a tax paid by non-Muslims which exempted them from military service, the Umayyads denied recognizing the conversion of non-Arabs as it reduced revenue. While the Rashidun Caliphate emphasized austerity, with Umar even requiring an inventory of each official's possessions, Umayyad luxury bred dissatisfaction among the pious. The Kharijites led the

Berber Revolt

The Berber Revolt of 740–743 AD (122–125 AH in the Islamic calendar) took place during the reign of the Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik and marked the first successful secession from the Arab caliphate (ruled from Damascus). Fired up b ...

leading to the first Muslim states independent of the Caliphate. In the

Abbasid revolution

The Abbasid Revolution, also called the Movement of the Men of the Black Raiment, was the overthrow of the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE), the second of the four major Caliphates in early Islamic history, by the third, the Abbasid Caliphate ( ...

, non-Arab converts (''

mawali

Mawlā ( ar, مَوْلَى, plural ''mawālī'' ()), is a polysemous Arabic word, whose meaning varied in different periods and contexts.A.J. Wensinck, Encyclopedia of Islam 2nd ed, Brill. "Mawlā", vol. 6, p. 874.

Before the Islamic prophet ...

''), Arab clans pushed aside by the Umayyad clan, and some Shi'a rallied and overthrew the Umayyads, inaugurating the more cosmopolitan Abbasid dynasty in 750.

Classical era (750–1258)

Al-Shafi'i codified a method to determine the reliability of hadith. During the early Abbasid era, scholars such as

Bukhari Bukhari or Bokhari () means "from Bukhara (Uzbekistan)" in Persian, Arabic, Urdu and Hebrew, and may refer to:

People

* al-Bukhari (810–870), Islamic hadith scholar and author of the

*Bukhari Daud (1959–2021), Indonesian academician and reg ...

and

Muslim compiled the major

Sunni hadith collections

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word ''Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagree ...

while scholars like

Al-Kulayni

Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Yaʿqūb ibn Iṣḥāq al Kulaynī ar Rāzī ( Persian: ar, أَبُو جَعْفَر مُحَمَّد ٱبْن يَعْقُوب إِسْحَاق ٱلْكُلَيْنِيّ ٱلرَّازِيّ; c. 250 AH/864 CE ...

and

Ibn Babawayh compiled major Shia hadith collections. The four Sunni

Madh'hab

A ( ar, مذهب ', , "way to act". pl. مَذَاهِب , ) is a school of thought within '' fiqh'' (Islamic jurisprudence).

The major Sunni Mathhab are Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali.

They emerged in the ninth and tenth centurie ...

s, the Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki, and Shafi'i, were established around the teachings of

Abū Ḥanīfa

Nuʿmān ibn Thābit ibn Zūṭā ibn Marzubān ( ar, نعمان بن ثابت بن زوطا بن مرزبان; –767), commonly known by his '' kunya'' Abū Ḥanīfa ( ar, أبو حنيفة), or reverently as Imam Abū Ḥanīfa by Sunni Musl ...

,

Ahmad ibn Hanbal

Ahmad ibn Hanbal al-Dhuhli ( ar, أَحْمَد بْن حَنْبَل الذهلي, translit=Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal al-Dhuhlī; November 780 – 2 August 855 CE/164–241 AH), was a Muslim jurist, theologian, ascetic, hadith traditionist, and f ...

, Malik ibn Anas and

al-Shafi'i

Abū ʿAbdillāh Muḥammad ibn Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī ( ar, أَبُو عَبْدِ ٱللهِ مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ إِدْرِيسَ ٱلشَّافِعِيُّ, 767–19 January 820 CE) was an Arab Muslim theologian, writer, and schol ...

. In contrast, the teachings of

Ja'far al-Sadiq

Jaʿfar ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī al-Ṣādiq ( ar, جعفر بن محمد الصادق; 702 – 765 CE), commonly known as Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (), was an 8th-century Shia Muslim scholar, jurist, and theologian.. He was the founder of th ...

formed the

Ja'fari jurisprudence. In the 9th century

Al-Tabari

( ar, أبو جعفر محمد بن جرير بن يزيد الطبري), more commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari i ...

completed the first commentary of the Quran, that became one of the most cited commentaries in Sunni Islam, the ''

Tafsir al-Tabari

''Jāmiʿ al-bayān ʿan taʾwīl āy al-Qurʾān'' (, also written with ''fī'' in place of ''ʿan''), popularly ''Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī'' ( ar, تفسير الطبري), is a Sunni '' tafsir'' by the Persian scholar Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari ( ...

''. Some Muslims began questioning the piety of indulgence in worldly life and emphasized poverty, humility, and avoidance of sin based on renunciation of bodily desires. Ascetics such as Hasan al-Basri would inspire a movement that would evolve into ''Tasawwuf'' or Sufism.

At this time, theological problems, notably on free will, were prominently tackled, with Hasan al Basri holding that although God knows people's actions, good and evil come from abuse of free will and the

devil

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conceptions of t ...

. Greek rationalist philosophy influenced a speculative school of thought known as

Muʿtazila, first originated by

Wasil ibn Ata

Wāṣil ibn ʿAtāʾ (700–748) ( ar, واصل بن عطاء) was an important Muslim theologian and jurist of his time, and by many accounts is considered to be the founder of the Muʿtazilite school of Kalam.

Born around the year 700 in the ...

. Caliphs such as

Mamun al Rashid

Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid ( ar, أبو العباس عبد الله بن هارون الرشيد, Abū al-ʿAbbās ʿAbd Allāh ibn Hārūn ar-Rashīd; 14 September 786 – 9 August 833), better known by his regnal name Al-Ma'mu ...

and

Al-Mu'tasim

Abū Isḥāq Muḥammad ibn Hārūn al-Rashīd ( ar, أبو إسحاق محمد بن هارون الرشيد; October 796 – 5 January 842), better known by his regnal name al-Muʿtaṣim biʾllāh (, ), was the eighth Abbasid caliph, ruling f ...

made it an official creed and unsuccessfully attempted to force their position on the majority. They carried out inquisitions with the traditionalist

Ahmad ibn Hanbal

Ahmad ibn Hanbal al-Dhuhli ( ar, أَحْمَد بْن حَنْبَل الذهلي, translit=Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal al-Dhuhlī; November 780 – 2 August 855 CE/164–241 AH), was a Muslim jurist, theologian, ascetic, hadith traditionist, and f ...

notably refusing to conform to the Mutazila idea of the creation of the Quran and was tortured and kept in an unlit prison cell for nearly thirty months. However, other

schools of

speculative theology –

Māturīdism founded by

Abu Mansur al-Maturidi

Abū Manṣūr Muḥammad b. Muḥammad b. Maḥmūd al-Ḥanafī al-Māturīdī al-Samarḳandī ( fa, أبو منصور محمد بن محمد بن محمود الماتریدي السمرقندي الحنفي; 853–944 CE), often referred t ...

and

Ash'ari

Ashʿarī theology or Ashʿarism (; ar, الأشعرية: ) is one of the main Sunnī schools of Islamic theology, founded by the Muslim scholar, Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer, and scholastic theologian Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī in the ...

founded by

Al-Ash'ari

Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī (; full name: ''Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Ismāʿīl ibn Isḥāq al-Ashʿarī''; c. 874–936 CE/260–324 AH), often reverently referred to as Imām al-Ashʿarī by Sunnī Muslims, was an Arab Muslim scholar ...

– were more successful in being widely adopted. Philosophers such as

Al-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a renowned early Is ...

,

Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic ...

and

Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology ...

sought to harmonize Aristotle's metaphysics within Islam, similar to later

scholasticism within Christianity in Europe, and

Maimonides' work within Judaism, while others like

Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian polymat ...

argued against such

syncretism and ultimately prevailed.

This era is sometimes called the "

Islamic Golden Age".

Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic ...

was a pioneer in

experimental medicine

An experimental drug is a medicinal product (a drug or vaccine) that has not yet received approval from governmental regulatory authorities for routine use in human or veterinary medicine. A medicinal product may be approved for use in one diseas ...

,

[Jacquart, Danielle (2008). "Islamic Pharmacology in the Middle Ages: Theories and Substances". European Review (Cambridge University Press) 16: 219–227.] and his ''

The Canon of Medicine'' was used as a standard medicinal text in the Islamic world and

Europe for centuries.

Rhazes

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (full name: ar, أبو بکر محمد بن زکریاء الرازي, translit=Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī, label=none), () rather than ar, زکریاء, label=none (), as for example in , or in . In m ...

was the first to distinguish the diseases

smallpox and

measles.

Public hospitals of the time issued the first medical diplomas to license doctors.

is regarded as the father of the modern

scientific method and often referred to as the "world's first true scientist", in particular regarding his work in

optics.

[ Haq, Syed (2009). "Science in Islam". Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages. . Retrieved 22 October 2014] In engineering, the

Banū Mūsā

The Banū Mūsā brothers ("Sons of Moses"), namely Abū Jaʿfar, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (before 803 – February 873); Abū al‐Qāsim, Aḥmad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century); and Al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th ce ...

brothers'

automatic flute player is considered to have been the first

programmable machine A program is a set of instructions used to control the behavior of a machine. Examples of such programs include:

*The sequence of cards used by a Jacquard loom to produce a given pattern within weaved cloth. Invented in 1801, it used holes in punc ...

.

In

mathematics, the concept of the

algorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm () is a finite sequence of rigorous instructions, typically used to solve a class of specific problems or to perform a computation. Algorithms are used as specifications for performing ...

is named after

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, who is considered a founder of

algebra

Algebra () is one of the broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics.

Elementary a ...

, which is named after his book

''al-jabr'', while others developed the concept of a

function

Function or functionality may refer to:

Computing

* Function key, a type of key on computer keyboards

* Function model, a structured representation of processes in a system

* Function object or functor or functionoid, a concept of object-oriente ...

. The government paid scientists the equivalent salary of professional athletes today.

The

Guinness World Records recognizes the

University of Al Karaouine

The University of al-Qarawiyyin ( ar, جامعة القرويين; ber, ⵜⴰⵙⴷⴰⵡⵉⵜ ⵏ ⵍⵇⴰⵕⴰⵡⵉⵢⵉⵏ; french: Université Al Quaraouiyine), also written Al-Karaouine or Al Quaraouiyine, is a university located in ...

, founded in 859, as the world's oldest degree-granting university.

The vast Abbasid empire proved impossible to hold together. Soldiers established their own dynasties, such as the

Tulunid

The Tulunids (), were a Mamluk dynasty of Turkic origin who were the first independent dynasty to rule Egypt, as well as much of Syria, since the Ptolemaic dynasty. They were independent from 868, when they broke away from the central authority ...

s,

Samanid and

Ghaznavid dynasty

The Ghaznavid dynasty ( fa, غزنویان ''Ġaznaviyān'') was a culturally Persianate, Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkic ''mamluk'' origin, ruling, at its greatest extent, large parts of Persia, Khorasan, much of Transoxiana and the northwest ...

. Additionally, the

millennialist Isma'ili Shi'a missionary movement rose with the

Fatimid dynasty

The Fatimid dynasty () was an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty of Arab descent that ruled an extensive empire, the Fatimid Caliphate, between 909 and 1171 CE. Claiming descent from Fatima and Ali, they also held the Isma'ili imamate, claiming to be the ...

taking control of North Africa and with the

Qarmatians sacking Mecca and stealing the Black Stone in their unsuccessful rebellion. In what is called the

Shi'a Century The Shi'a Century or Shi'ite Century is a historiographical term sometimes used to describe the period between 945 and 1055, when Shi'a Muslim regimes, most notably the Fatimids and the Buyids, held sway over the central lands of the Islamic world. ...

, another Ismaili group, the

Buyid dynasty

The Buyid dynasty ( fa, آل بویه, Āl-e Būya), also spelled Buwayhid ( ar, البويهية, Al-Buwayhiyyah), was a Shia Iranian dynasty of Daylamite origin, which mainly ruled over Iraq and central and southern Iran from 934 to 1062. Cou ...

conquered Baghdad and turned the Abbasids into a figurehead monarchy. The Sunni Seljuk dynasty, campaigned to

reassert Sunni Islam by promulgating the accumulated scholarly opinion of the time notably with the construction of educational institutions known as

Nezamiyeh

The Nezamiyeh ( fa, نظامیه) or Nizamiyyah ( ar, النظامیة) are a group of institutions of higher education established by Khwaja Nizam al-Mulk in the eleventh century in Iran. The name ''nizamiyyah'' derives from his name. Founded a ...

, which are associated with Al-Ghazali and

Saadi Shirazi

Saadi Shīrāzī ( fa, ابومحمّد مصلحالدین بن عبدالله شیرازی), better known by his pen name Saadi (; fa, سعدی, , ), also known as Sadi of Shiraz (, ''Saʿdī Shīrāzī''; born 1210; died 1291 or 1292), was ...

. The Ismailis continued splintering over the legitimacy of successive imams with the

Alawites

The Alawis, Alawites ( ar, علوية ''Alawīyah''), or pejoratively Nusayris ( ar, نصيرية ''Nuṣayrīyah'') are an ethnoreligious group that lives primarily in Levant and follows Alawism, a sect of Islam that originated from Shia Isla ...

and the

Druze, offshoots of Shi'a Islam, dating to this time.

Religious missions converted

Volga Bulgaria to Islam. The

Delhi Sultanate reached deep into the

Indian Subcontinent and many converted to Islam, in particular

low-caste Hindus whose descendents make up the vast majority of Indian Muslims. Many Muslims also went to

China to trade, virtually dominating the import and export industry of the

Song dynasty.

Pre-Modern era (1258–18th century)

Through Muslim trade networks and the activity of Sufi orders, Islam spread into new areas. Under the

Ottoman Empire, Islam spread to

Southeast Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe (SEE) is a geographical subregion of Europe, consisting primarily of the Balkans. Sovereign states and territories that are included in the region are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia (a ...

. Conversion to Islam, however, was not a sudden abandonment of old religious practices; rather, it was typically a matter of "assimilating Islamic rituals, cosmologies, and literatures into... local religious systems", as illustrated by Muhammad's appearance in