International Committee Of The Red Cross on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in

Up until the middle of the 19th century, there were no organized and well-established army

Up until the middle of the 19th century, there were no organized and well-established army  On 9 February 1863 in Geneva, Henry Dunant founded the "Committee of the Five" (together with four other leading figures from well-known Geneva families) as an investigatory commission of the

On 9 February 1863 in Geneva, Henry Dunant founded the "Committee of the Five" (together with four other leading figures from well-known Geneva families) as an investigatory commission of the  Only one year later, the Swiss government invited the governments of all European countries, as well as the United States, Brazil, and Mexico, to attend an official diplomatic conference. Sixteen countries sent a total of twenty-six delegates to Geneva. On 22 August 1864, the conference adopted the first

Only one year later, the Swiss government invited the governments of all European countries, as well as the United States, Brazil, and Mexico, to attend an official diplomatic conference. Sixteen countries sent a total of twenty-six delegates to Geneva. On 22 August 1864, the conference adopted the first  Also in 1867, Henry Dunant was forced to declare bankruptcy due to business failures in Algeria, partly because he had neglected his business interests during his tireless activities for the International Committee. The controversy surrounding Dunant's business dealings and the resulting negative public opinion, combined with an ongoing conflict with Gustave Moynier, led to Dunant's expulsion from his position as a member and secretary. He was charged with fraudulent bankruptcy and a warrant for his arrest was issued. Thus, he was forced to leave Geneva and never returned to his home city.

In the following years, national societies were founded in nearly every country in Europe. The project resonated well with patriotic sentiments that were on the rise in the late-nineteenth-century, and national societies were often encouraged as signifiers of national moral superiority. In 1876, the committee adopted the name "International Committee of the Red Cross" (ICRC), which is still its official designation today. Five years later, the American Red Cross was founded through the efforts of Clara Barton. More and more countries signed the Geneva Convention and began to respect it in practice during armed conflicts. In a rather short period of time, the Red Cross gained huge momentum as an internationally respected movement, and the national societies became increasingly popular as a venue for volunteer work.

When the first

Also in 1867, Henry Dunant was forced to declare bankruptcy due to business failures in Algeria, partly because he had neglected his business interests during his tireless activities for the International Committee. The controversy surrounding Dunant's business dealings and the resulting negative public opinion, combined with an ongoing conflict with Gustave Moynier, led to Dunant's expulsion from his position as a member and secretary. He was charged with fraudulent bankruptcy and a warrant for his arrest was issued. Thus, he was forced to leave Geneva and never returned to his home city.

In the following years, national societies were founded in nearly every country in Europe. The project resonated well with patriotic sentiments that were on the rise in the late-nineteenth-century, and national societies were often encouraged as signifiers of national moral superiority. In 1876, the committee adopted the name "International Committee of the Red Cross" (ICRC), which is still its official designation today. Five years later, the American Red Cross was founded through the efforts of Clara Barton. More and more countries signed the Geneva Convention and began to respect it in practice during armed conflicts. In a rather short period of time, the Red Cross gained huge momentum as an internationally respected movement, and the national societies became increasingly popular as a venue for volunteer work.

When the first

With the outbreak of World War I, the ICRC found itself confronted with enormous challenges which it could only handle by working closely with the national Red Cross societies. Red Cross nurses from around the world, including the United States and Japan, came to support the medical services of the armed forces of the European countries involved in the war. On 15 October 1914, immediately after the start of the war, the ICRC set up its International Prisoners-of-War ( POW) Agency, which had about 1,200 mostly volunteer staff members by the end of 1914. By the end of the war, the Agency had transferred about 20 million letters and messages, 1.9 million parcels, and about 18 million Swiss francs in monetary donations to POWs of all affected countries. Furthermore, due to the intervention of the Agency, about 200,000 prisoners were exchanged between the warring parties, released from captivity and returned to their home country. The organizational card index of the Agency accumulated about 7 million records from 1914 to 1923, each card representing an individual prisoner or missing person. The card index led to the identification of about 2 million POWs and the ability to contact their families, as part of the

With the outbreak of World War I, the ICRC found itself confronted with enormous challenges which it could only handle by working closely with the national Red Cross societies. Red Cross nurses from around the world, including the United States and Japan, came to support the medical services of the armed forces of the European countries involved in the war. On 15 October 1914, immediately after the start of the war, the ICRC set up its International Prisoners-of-War ( POW) Agency, which had about 1,200 mostly volunteer staff members by the end of 1914. By the end of the war, the Agency had transferred about 20 million letters and messages, 1.9 million parcels, and about 18 million Swiss francs in monetary donations to POWs of all affected countries. Furthermore, due to the intervention of the Agency, about 200,000 prisoners were exchanged between the warring parties, released from captivity and returned to their home country. The organizational card index of the Agency accumulated about 7 million records from 1914 to 1923, each card representing an individual prisoner or missing person. The card index led to the identification of about 2 million POWs and the ability to contact their families, as part of the

The most reliable primary source on the role of the Red Cross during World War II are the three volumes of the "Report of the International Committee of the Red Cross on its activities during the second world war (September 1, 1939 – June 30, 1947)" written by the International Committee of the Red Cross itself. The report can be read online.

The legal basis of the work of the ICRC during World War II was the Geneva Conventions (1929) revision, as well as the Convention relating to the International Status of Refugees, of 28 October 1933. The activities of the committee were similar to those during World War I: visiting and monitoring POW camps, organizing relief assistance for civilian populations, and administering the exchange of messages regarding prisoners and missing persons. By the end of the war, 179 delegates had conducted 12,750 visits to POW camps in 41 countries. The Central Information Agency on Prisoners-of-War (''Zentralauskunftsstelle für Kriegsgefangene'') had a staff of 3,000, the card index tracking prisoners contained 45 million cards, and 120 million messages were exchanged by the Agency. Moreover, two other main parties to the conflict, the

The most reliable primary source on the role of the Red Cross during World War II are the three volumes of the "Report of the International Committee of the Red Cross on its activities during the second world war (September 1, 1939 – June 30, 1947)" written by the International Committee of the Red Cross itself. The report can be read online.

The legal basis of the work of the ICRC during World War II was the Geneva Conventions (1929) revision, as well as the Convention relating to the International Status of Refugees, of 28 October 1933. The activities of the committee were similar to those during World War I: visiting and monitoring POW camps, organizing relief assistance for civilian populations, and administering the exchange of messages regarding prisoners and missing persons. By the end of the war, 179 delegates had conducted 12,750 visits to POW camps in 41 countries. The Central Information Agency on Prisoners-of-War (''Zentralauskunftsstelle für Kriegsgefangene'') had a staff of 3,000, the card index tracking prisoners contained 45 million cards, and 120 million messages were exchanged by the Agency. Moreover, two other main parties to the conflict, the  Swiss historian Jean-Claude Favez, who conducted an 8-year review of the Red Cross records, says that even though the Red Cross knew by November 1942 about the Nazi's annihilation plans for the Jews – and even discussed it with U.S. officials – the group did nothing to inform the public, maintaining silence even in the face of pleas by Jewish groups.

Because the Red Cross was based in Geneva and largely funded by the Swiss government, it was very sensitive to Swiss wartime attitudes and policies. In October 1942, the Swiss government and the Red Cross' board of members vetoed a proposal by several Red Cross board members to condemn the persecution of civilians by the Nazis. For the rest of the war, the Red Cross took its cues from Switzerland in avoiding acts of opposition or confrontation with the Nazis.

Swiss historian Jean-Claude Favez, who conducted an 8-year review of the Red Cross records, says that even though the Red Cross knew by November 1942 about the Nazi's annihilation plans for the Jews – and even discussed it with U.S. officials – the group did nothing to inform the public, maintaining silence even in the face of pleas by Jewish groups.

Because the Red Cross was based in Geneva and largely funded by the Swiss government, it was very sensitive to Swiss wartime attitudes and policies. In October 1942, the Swiss government and the Red Cross' board of members vetoed a proposal by several Red Cross board members to condemn the persecution of civilians by the Nazis. For the rest of the war, the Red Cross took its cues from Switzerland in avoiding acts of opposition or confrontation with the Nazis.

On 12 March 1945, ICRC President Jacob Burckhardt received a message from SS General Ernst Kaltenbrunner accepting the ICRC's demand to allow delegates to visit the concentration camps. This agreement was bound by the condition that these delegates would have to stay in the camps until the end of the war. Ten delegates, among them

On 12 March 1945, ICRC President Jacob Burckhardt received a message from SS General Ernst Kaltenbrunner accepting the ICRC's demand to allow delegates to visit the concentration camps. This agreement was bound by the condition that these delegates would have to stay in the camps until the end of the war. Ten delegates, among them

The original motto of the International Committee of the Red Cross was ''Inter Arma Caritas'' ("Amidst War, Charity"). It has preserved this motto while other Red Cross organizations have adopted others. Due to Geneva's location in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, the ICRC is also known under its initial French name ''Comité international de la Croix-Rouge'' (CICR). However, the ICRC has three official languages (English, French and Spanish). The official symbol of the ICRC is the Red Cross on white background (the inverse of the

The original motto of the International Committee of the Red Cross was ''Inter Arma Caritas'' ("Amidst War, Charity"). It has preserved this motto while other Red Cross organizations have adopted others. Due to Geneva's location in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, the ICRC is also known under its initial French name ''Comité international de la Croix-Rouge'' (CICR). However, the ICRC has three official languages (English, French and Spanish). The official symbol of the ICRC is the Red Cross on white background (the inverse of the

The Assembly (also called the Committee) convenes on a regular basis and is responsible for defining aims, guidelines, and strategies and for supervising the financial matters of the committee. The Assembly has a membership of a maximum of twenty-five Swiss citizens. Members must speak the house language of French, but many also speak English and German as well. These Assembly members are co-opted for a period of four years, and there is no limit to the number of terms an individual member can serve. A three-quarters majority vote from all members is required for re-election after the third term, which acts as a motivation for members to remain active and productive.

In the early years, every Committee member was Genevan, Protestant,

The Assembly (also called the Committee) convenes on a regular basis and is responsible for defining aims, guidelines, and strategies and for supervising the financial matters of the committee. The Assembly has a membership of a maximum of twenty-five Swiss citizens. Members must speak the house language of French, but many also speak English and German as well. These Assembly members are co-opted for a period of four years, and there is no limit to the number of terms an individual member can serve. A three-quarters majority vote from all members is required for re-election after the third term, which acts as a motivation for members to remain active and productive.

In the early years, every Committee member was Genevan, Protestant,

File:Guillaume Henri Dufour (Irminger).png, Guillaume Dufour,

(1787-1875) File:Gustave Moynier.jpg, Gustave Moynier,

(1826-1910) File:GustaveAdor.jpg, Gustave Ador,

(1845-1928) File:Max Huber.jpg, Max Huber,

(1874-1960) File:Carl Burckhardt.jpg, Carl Burckhardt,

(1891-1974) File:Alexandre Hay.jpg, Alexandre Hay,

(1919-1991) File:Cornelio Sommaruga.jpg, Cornelio Sommaruga,

(1932-) File:Jakob Kellenberger.jpg, Jakob Kellenberger,

(1944- ) File:ICRC president Peter Maurer in Syria (7930973296).jpg, Peter Maurer,

(1956- )

By virtue of its age and its special position under

By virtue of its age and its special position under

The ICRC prefers to engage states directly and relies on low-key and confidential negotiations to lobby for access to prisoners of war and improvement in their treatment. Its findings are not available to the general public but are shared only with the relevant government. This is in contrast to related organizations like Doctors Without Borders and Amnesty International who are more willing to expose abuses and apply public pressure to governments. The ICRC reasons that this approach allows it greater access and cooperation from governments in the long run.

When granted only partial access, the ICRC takes what it can get and keeps discreetly lobbying for greater access. In the era of apartheid South Africa, it was granted access to prisoners like Nelson Mandela serving sentences, but not to those under interrogation and awaiting trial. After his release, Mandela publicly praised the Red Cross.

The presence of respectable aid organizations can make weak

The ICRC prefers to engage states directly and relies on low-key and confidential negotiations to lobby for access to prisoners of war and improvement in their treatment. Its findings are not available to the general public but are shared only with the relevant government. This is in contrast to related organizations like Doctors Without Borders and Amnesty International who are more willing to expose abuses and apply public pressure to governments. The ICRC reasons that this approach allows it greater access and cooperation from governments in the long run.

When granted only partial access, the ICRC takes what it can get and keeps discreetly lobbying for greater access. In the era of apartheid South Africa, it was granted access to prisoners like Nelson Mandela serving sentences, but not to those under interrogation and awaiting trial. After his release, Mandela publicly praised the Red Cross.

The presence of respectable aid organizations can make weak

International Committee of the Red Cross: "Discover the ICRC", ICRC, Geneva, 2007, 2nd edition, 53 pp.

International Review of the Red Cross

An unrivalled source of international research, analysis and debate on all aspects of humanitarian law, in armed conflict and other situations of collective violence.

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)

vidéo

Legacy

Dr. Cornelio Sommaruga, President of the ICRC from 1987–1999, donated four hours of high-definition audiovisual life story interviews to Legacy. The ICRC audiovisual library houses copies of these interviews. * * * {{Authority control Organizations established in 1863 International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement United Nations General Assembly observers Organizations awarded Nobel Peace Prizes Swiss Nobel laureates Nobel laureates with multiple Nobel awards Organisations based in Geneva Human rights organisations based in Switzerland 1863 establishments in Switzerland Henry Dunant

Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

, Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

Laureate. State parties (signatories) to the Geneva Convention

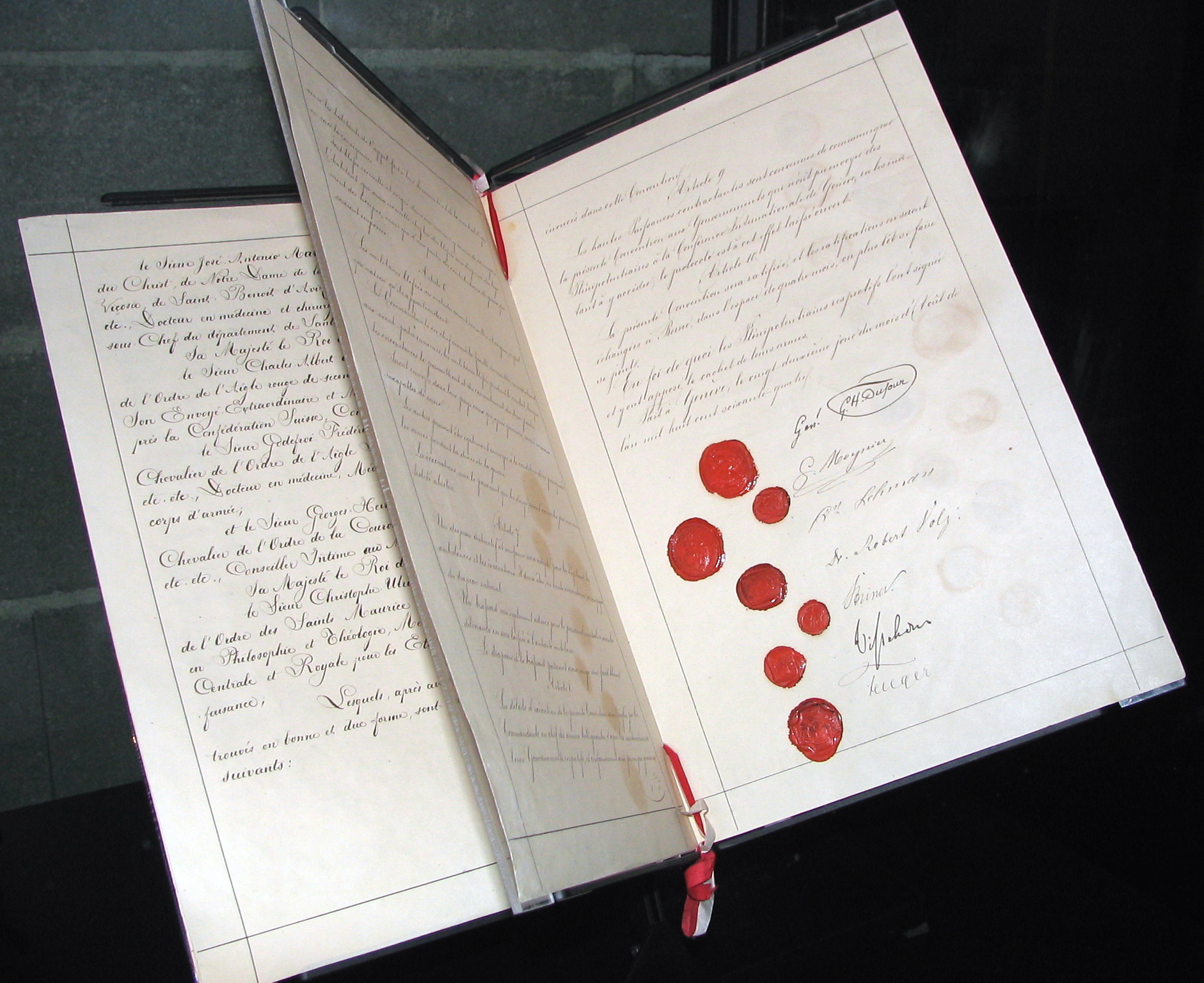

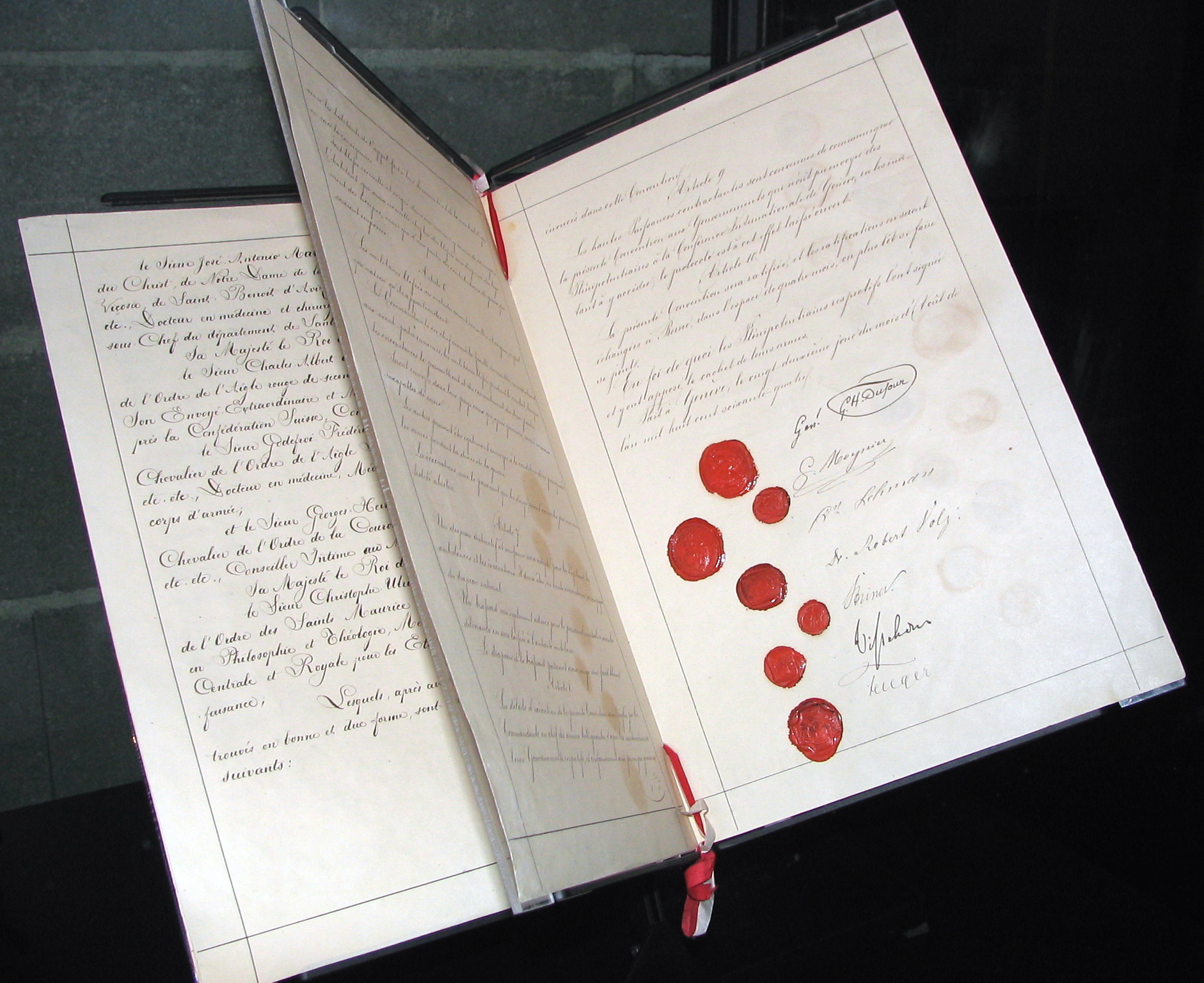

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conve ...

of 1949 and its Additional Protocols of 1977 ( Protocol I, Protocol II) and 2005 have given the ICRC a mandate to protect victims of international and internal armed conflicts. Such victims include war wounded persons, prisoners, refugees, civilian

Civilians under international humanitarian law are "persons who are not members of the armed forces" and they are not " combatants if they carry arms openly and respect the laws and customs of war". It is slightly different from a non-combatant ...

s, and other non-combatant

Non-combatant is a term of art in the law of war and international humanitarian law to refer to civilians who are not taking a direct part in hostilities; persons, such as combat medics and military chaplains, who are members of the belligere ...

s.

The ICRC is part of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, along with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and 192 National Societies. It is the oldest and most honoured organization within the movement and one of the most widely recognized organizations in the world, having won three Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolo ...

s (in 1917, 1944, and 1963).

History

Solferino, Henry Dunant and the foundation of the ICRC

Up until the middle of the 19th century, there were no organized and well-established army

Up until the middle of the 19th century, there were no organized and well-established army nursing

Nursing is a profession within the health care sector focused on the care of individuals, families, and communities so they may attain, maintain, or recover optimal health and quality of life. Nurses may be differentiated from other health ...

systems for casualties and no safe and protected institutions to accommodate and treat those who were wounded on the battlefield. In June 1859, the Swiss businessman Henry Dunant

Henry Dunant (born Jean-Henri Dunant; 8 May 182830 October 1910), also known as Henri Dunant, was a Swiss humanitarian, businessman, and social activist. He was the visionary, promoter, and co-founder of the Red Cross. In 1901, he received the ...

travelled to Italy to meet French emperor Napoléon III with the intention of discussing difficulties in conducting business in Algeria, at that time occupied by France. When he arrived in the small Italian town of Solferino on the evening of 24 June, he witnessed the aftermath of the Battle of Solferino

The Battle of Solferino (referred to in Italy as the Battle of Solferino and San Martino) on 24 June 1859 resulted in the victory of the allied Second French Empire, French Army under Napoleon III and Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, Piedmont-Sard ...

, an engagement in the Second Italian War of Independence. In a single day, about 40,000 soldiers on both sides died or were left wounded on the field. Henry Dunant was shocked by the terrible aftermath of the battle, the suffering of the wounded soldiers, and the near-total lack of medical attendance and basic care. He completely abandoned the original intent of his trip and for several days he devoted himself to helping with the treatment and care for the wounded. He succeeded in organizing an overwhelming level of relief assistance by motivating the local population to aid without discrimination. Back in his home in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

, he decided to write a book titled '' A Memory of Solferino'' which he published with his own money in 1862. He sent copies of the book to leading political and military figures throughout Europe. In addition to penning a vivid description of his experiences in Solferino in 1859, he explicitly advocated the formation of national voluntary relief organizations to help nurse wounded soldiers in the case of war. In addition, he called for the development of international treaties to guarantee the neutrality and protection of those wounded on the battlefield as well as medics and field hospitals.

On 9 February 1863 in Geneva, Henry Dunant founded the "Committee of the Five" (together with four other leading figures from well-known Geneva families) as an investigatory commission of the

On 9 February 1863 in Geneva, Henry Dunant founded the "Committee of the Five" (together with four other leading figures from well-known Geneva families) as an investigatory commission of the Geneva Society for Public Welfare

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

. Their aim was to examine the feasibility of Dunant's ideas and to organize an international conference about their possible implementation. The members of this committee, aside from Dunant himself, were Gustave Moynier, lawyer and chairman of the Geneva Society for Public Welfare; physician Louis Appia

Louis Paul Amédée Appia (13 October 1818 – 1 May 1898) was a Swiss surgeon with special merit in the area of military medicine. In 1863 he became a member of the Geneva "Committee of Five", which was the precursor to the International Commit ...

, who had significant experience working as a field surgeon; Appia's friend and colleague Théodore Maunoir

Dr. Théodore Maunoir (1 June 1806 – 26 April 1869) was a Swiss surgeon and co-founder of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

Théodore Maunoir was born to a wealthy family of doctors in Geneva. Following family traditio ...

, from the Geneva Hygiene and Health Commission; and Guillaume-Henri Dufour

Guillaume Henri Dufour (15 September 178714 July 1875) was a Swiss military officer, structural engineer and topographer. He served under Napoleon I and held the Swiss office of General four times in his career, firstly in 1847 when he led th ...

, a Swiss Army general of great renown. Eight days later, the five men decided to rename the committee to the "International Committee for Relief to the Wounded". In October (26–29) 1863, the international conference organized by the committee was held in Geneva to develop possible measures to improve medical services on the battlefield. The conference was attended by 36 individuals: eighteen official delegates from national governments, six delegates from other non-governmental organizations, seven non-official foreign delegates, and the five members of the International Committee. The states and kingdoms represented by official delegates were Grand Duchy of Baden

The Grand Duchy of Baden (german: Großherzogtum Baden) was a state in the southwest German Empire on the east bank of the Rhine. It existed between 1806 and 1918.

It came into existence in the 12th century as the Margraviate of Baden and subs ...

, Kingdom of Bavaria

The Kingdom of Bavaria (german: Königreich Bayern; ; spelled ''Baiern'' until 1825) was a German state that succeeded the former Electorate of Bavaria in 1805 and continued to exist until 1918. With the unification of Germany into the German ...

, Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the Second and the Third Republic of France.

Historians in the 1930s ...

, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in the British Isles that existed between 1801 and 1922, when it included all of Ireland. It was established by the Acts of Union 1800, which merged the Kingdom of Grea ...

, Kingdom of Hanover, Grand Duchy of Hesse, Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

, Kingdom of the Netherlands

, national_anthem = )

, image_map = Kingdom of the Netherlands (orthographic projection).svg

, map_width = 250px

, image_map2 = File:KonDerNed-10-10-10.png

, map_caption2 = Map of the four constituent countries shown to scale

, capital = ...

, Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

, Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

, Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony (german: Königreich Sachsen), lasting from 1806 to 1918, was an independent member of a number of historical confederacies in Napoleonic through post-Napoleonic Germany. The kingdom was formed from the Electorate of Sax ...

, United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two ...

, and Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

. Among the proposals written in the final resolutions of the conference, adopted on 29 October 1863, were:

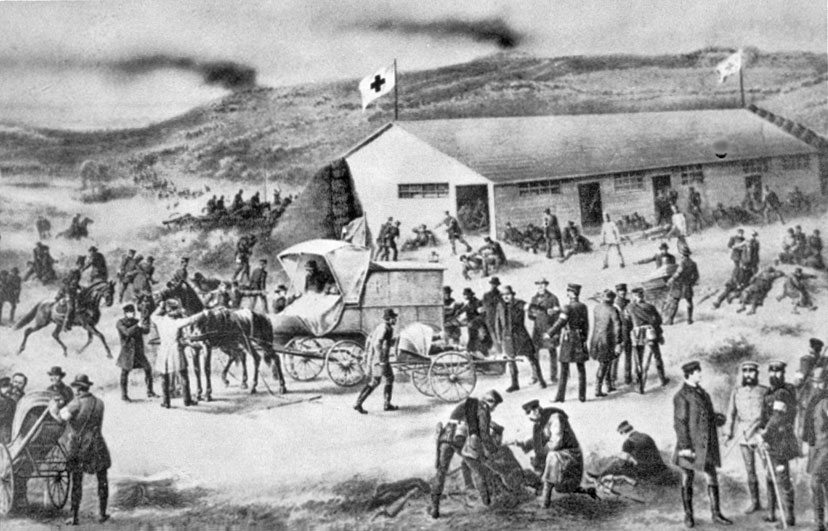

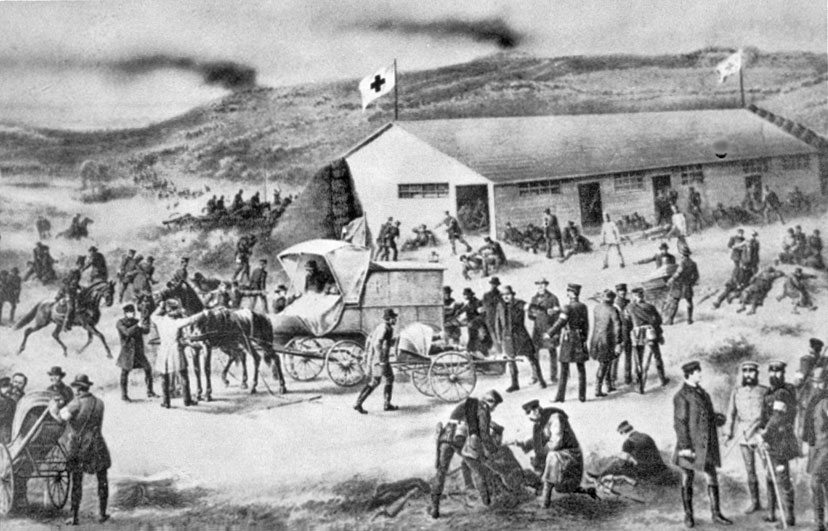

* The foundation of national relief societies for wounded soldiers;

* Neutrality and protection for wounded soldiers;

* The utilization of volunteer forces for relief assistance on the battlefield;

* The organization of additional conferences to enact these concepts in legally binding international treaties; and

* The introduction of a common distinctive protection symbol for medical personnel in the field, namely a white armlet bearing a red cross, honouring the history of neutrality of Switzerland and of its own Swiss organizers by reversing the Swiss flag's colours.

Only one year later, the Swiss government invited the governments of all European countries, as well as the United States, Brazil, and Mexico, to attend an official diplomatic conference. Sixteen countries sent a total of twenty-six delegates to Geneva. On 22 August 1864, the conference adopted the first

Only one year later, the Swiss government invited the governments of all European countries, as well as the United States, Brazil, and Mexico, to attend an official diplomatic conference. Sixteen countries sent a total of twenty-six delegates to Geneva. On 22 August 1864, the conference adopted the first Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conve ...

"for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field". Representatives of 12 states and kingdoms signed the convention:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

The convention contained ten articles, establishing for the first time legally binding rules guaranteeing neutrality and protection for wounded soldiers, field medical personnel, and specific humanitarian institutions in an armed conflict. Furthermore, the convention defined two specific requirements for recognition of a national relief society by the International Committee:

* The national society must be recognized by its own national government as a relief society according to the convention, and

* The national government of the respective country must be a state party to the Geneva Convention.

Directly following the establishment of the Geneva Convention, the first national societies were founded in Belgium, Denmark, France, Oldenburg, Prussia, Spain, and Württemberg. Also in 1864, Louis Appia and Charles van de Velde

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was " ...

, a captain of the Dutch Army, became the first independent and neutral delegates to work under the symbol of the Red Cross in an armed conflict. Three years later in 1867, the first International Conference of National Aid Societies for the Nursing of the War Wounded was convened.

Also in 1867, Henry Dunant was forced to declare bankruptcy due to business failures in Algeria, partly because he had neglected his business interests during his tireless activities for the International Committee. The controversy surrounding Dunant's business dealings and the resulting negative public opinion, combined with an ongoing conflict with Gustave Moynier, led to Dunant's expulsion from his position as a member and secretary. He was charged with fraudulent bankruptcy and a warrant for his arrest was issued. Thus, he was forced to leave Geneva and never returned to his home city.

In the following years, national societies were founded in nearly every country in Europe. The project resonated well with patriotic sentiments that were on the rise in the late-nineteenth-century, and national societies were often encouraged as signifiers of national moral superiority. In 1876, the committee adopted the name "International Committee of the Red Cross" (ICRC), which is still its official designation today. Five years later, the American Red Cross was founded through the efforts of Clara Barton. More and more countries signed the Geneva Convention and began to respect it in practice during armed conflicts. In a rather short period of time, the Red Cross gained huge momentum as an internationally respected movement, and the national societies became increasingly popular as a venue for volunteer work.

When the first

Also in 1867, Henry Dunant was forced to declare bankruptcy due to business failures in Algeria, partly because he had neglected his business interests during his tireless activities for the International Committee. The controversy surrounding Dunant's business dealings and the resulting negative public opinion, combined with an ongoing conflict with Gustave Moynier, led to Dunant's expulsion from his position as a member and secretary. He was charged with fraudulent bankruptcy and a warrant for his arrest was issued. Thus, he was forced to leave Geneva and never returned to his home city.

In the following years, national societies were founded in nearly every country in Europe. The project resonated well with patriotic sentiments that were on the rise in the late-nineteenth-century, and national societies were often encouraged as signifiers of national moral superiority. In 1876, the committee adopted the name "International Committee of the Red Cross" (ICRC), which is still its official designation today. Five years later, the American Red Cross was founded through the efforts of Clara Barton. More and more countries signed the Geneva Convention and began to respect it in practice during armed conflicts. In a rather short period of time, the Red Cross gained huge momentum as an internationally respected movement, and the national societies became increasingly popular as a venue for volunteer work.

When the first Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolo ...

was awarded in 1901, the Norwegian Nobel Committee opted to give it jointly to Henry Dunant and Frédéric Passy, a leading international pacifist. More significant than the honour of the prize itself, the official congratulation from the International Committee of the Red Cross marked the overdue rehabilitation of Henry Dunant and represented a tribute to his key role in the formation of the Red Cross. Dunant died nine years later in the small Swiss health resort of Heiden. Only two months earlier his long-standing adversary Gustave Moynier had also died, leaving a mark in the history of the committee as its longest-serving President ever.

In 1906, the 1864 Geneva Convention was revised for the first time. One year later, the Hague Convention X, adopted at the Second International Peace Conference in The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

, extended the scope of the Geneva Convention to naval warfare. Shortly before the beginning of the First World War in 1914, 50 years after the foundation of the ICRC and the adoption of the first Geneva Convention, there were already 45 national relief societies throughout the world. The movement had extended itself beyond Europe and North America to Central and South America (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Mexico, Peru, El Salvador, Uruguay, Venezuela), Asia (the Republic of China, Japan, Korea, Siam), and Africa (South Africa).

World War I

Restoring Family Links

Restoring Family Links (RFL) is a program of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, more specifically the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies involving activities that aim to pre ...

effort of the organization. The complete index is on loan today from the ICRC to the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum in Geneva. The right to access the index is still strictly restricted to the ICRC.

During the entire war, the ICRC monitored warring parties' compliance with the Geneva Conventions of the 1907 revision and forwarded complaints about violations to the respective country. When chemical weapons were used in this war for the first time in history, the ICRC vigorously protested against this new type of warfare. Even without having a mandate from the Geneva Conventions, the ICRC tried to ameliorate the suffering of civil populations. In territories that were officially designated as "occupied territories," the ICRC could assist the civilian population on the basis of the Hague Convention's "Laws and Customs of War on Land" of 1907. This convention was also the legal basis for the ICRC's work for prisoners of war. In addition to the work of the International Prisoner-of-War Agency as described above this included inspection visits to POW camps. A total of 524 camps throughout Europe were visited by 41 delegates from the ICRC until the end of the war.

Between 1916 and 1918, the ICRC published a number of postcard

A postcard or post card is a piece of thick paper or thin cardboard, typically rectangular, intended for writing and mailing without an envelope. Non-rectangular shapes may also be used but are rare. There are novelty exceptions, such as woo ...

s with scenes from the POW camps. The pictures showed the prisoners in day-to-day activities such as the distribution of letters from home. The intention of the ICRC was to provide the families of the prisoners with some hope and solace and to alleviate their uncertainties about the fate of their loved ones. After the end of the war, the ICRC organized the return of about 420,000 prisoners to their home countries. In 1920, the task of repatriation was handed over to the newly founded League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

, which appointed the Norwegian diplomat and scientist Fridtjof Nansen as its "High Commissioner for Repatriation of the War Prisoners". His legal mandate was later extended to support and care for war refugees and displaced persons when his office became that of the League of Nations " High Commissioner for Refugees". Nansen, who invented the ''Nansen passport

Nansen passports, originally and officially stateless persons passports, were internationally recognized refugee travel documents from 1922 to 1938, first issued by the League of Nations's Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees to stateles ...

'' for stateless refugees and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922, appointed two delegates from the ICRC as his deputies.

A year before the end of the war, the ICRC received the 1917 Nobel Peace Prize for its outstanding wartime work. It was the only Nobel Peace Prize awarded in the period from 1914 to 1918. In 1923, the Committee adopted a change in its policy regarding the selection of new members. Until then, only citizens from the city of Geneva could serve in the committee. This limitation was expanded to include Swiss citizens. As a direct consequence of World War I, an additional protocol to the Geneva Convention was adopted in 1925 which outlawed the use of suffocating or poisonous gases and biological agents as weapons. Four years later, the original Convention was revised and the second Geneva Convention "relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" was established. The events of World War I and the respective activities of the ICRC significantly increased the reputation and authority of the Committee among the international community and led to an extension of its competencies.

As early as in 1934, a draft proposal for an additional convention for the protection of the civil population during an armed conflict was adopted by the International Red Cross Conference. Unfortunately, most governments had little interest in implementing this convention, and it was thus prevented from entering into force before the beginning of World War II.

Chaco War

In the Interwar period, Bolivia and Paraguay were disputing possession of theGran Chaco

The Gran Chaco or Dry Chaco is a sparsely populated, hot and semiarid lowland natural region of the Río de la Plata basin, divided among eastern Bolivia, western Paraguay, northern Argentina, and a portion of the Brazilian states of Mato ...

- a desert region between the two countries. The dispute escalated into a full-scale conflict in 1932. During the war the ICRC visited 18,000 Bolivian prisoners of war and 2,500 Paraguayan detainees. With the help of the ICRC both countries made improvements to the conditions of the detainees.

World War II

The most reliable primary source on the role of the Red Cross during World War II are the three volumes of the "Report of the International Committee of the Red Cross on its activities during the second world war (September 1, 1939 – June 30, 1947)" written by the International Committee of the Red Cross itself. The report can be read online.

The legal basis of the work of the ICRC during World War II was the Geneva Conventions (1929) revision, as well as the Convention relating to the International Status of Refugees, of 28 October 1933. The activities of the committee were similar to those during World War I: visiting and monitoring POW camps, organizing relief assistance for civilian populations, and administering the exchange of messages regarding prisoners and missing persons. By the end of the war, 179 delegates had conducted 12,750 visits to POW camps in 41 countries. The Central Information Agency on Prisoners-of-War (''Zentralauskunftsstelle für Kriegsgefangene'') had a staff of 3,000, the card index tracking prisoners contained 45 million cards, and 120 million messages were exchanged by the Agency. Moreover, two other main parties to the conflict, the

The most reliable primary source on the role of the Red Cross during World War II are the three volumes of the "Report of the International Committee of the Red Cross on its activities during the second world war (September 1, 1939 – June 30, 1947)" written by the International Committee of the Red Cross itself. The report can be read online.

The legal basis of the work of the ICRC during World War II was the Geneva Conventions (1929) revision, as well as the Convention relating to the International Status of Refugees, of 28 October 1933. The activities of the committee were similar to those during World War I: visiting and monitoring POW camps, organizing relief assistance for civilian populations, and administering the exchange of messages regarding prisoners and missing persons. By the end of the war, 179 delegates had conducted 12,750 visits to POW camps in 41 countries. The Central Information Agency on Prisoners-of-War (''Zentralauskunftsstelle für Kriegsgefangene'') had a staff of 3,000, the card index tracking prisoners contained 45 million cards, and 120 million messages were exchanged by the Agency. Moreover, two other main parties to the conflict, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

, were not party to the 1929 Geneva Conventions and were not legally required to follow the rules of the conventions.

During the war, the ICRC failed to obtain an agreement with Nazi Germany about the treatment of detainees in concentration camps, and it eventually abandoned applying pressure to avoid disrupting its work with POWs. The ICRC also failed to develop a response to reliable information about the extermination camps and the mass killing of European Jews. This is still considered the greatest failure of the ICRC in its history. After November 1943, the ICRC achieved permission to send parcels to concentration camp detainees with known names and locations. Because the notices of receipt for these parcels were often signed by other inmates, the ICRC managed to register the identities of about 105,000 detainees in the concentration camps and delivered about 1.1 million parcels, primarily to the camps Dachau

Dachau () was the first concentration camp built by Nazi Germany, opening on 22 March 1933. The camp was initially intended to intern Hitler's political opponents which consisted of: communists, social democrats, and other dissidents. It is lo ...

, Buchenwald, Ravensbrück, and Sachsenhausen

Sachsenhausen () or Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg was a German Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, used from 1936 until April 1945, shortly before the defeat of Nazi Germany in May later that year. It mainly held political prisoners ...

.

Swiss historian Jean-Claude Favez, who conducted an 8-year review of the Red Cross records, says that even though the Red Cross knew by November 1942 about the Nazi's annihilation plans for the Jews – and even discussed it with U.S. officials – the group did nothing to inform the public, maintaining silence even in the face of pleas by Jewish groups.

Because the Red Cross was based in Geneva and largely funded by the Swiss government, it was very sensitive to Swiss wartime attitudes and policies. In October 1942, the Swiss government and the Red Cross' board of members vetoed a proposal by several Red Cross board members to condemn the persecution of civilians by the Nazis. For the rest of the war, the Red Cross took its cues from Switzerland in avoiding acts of opposition or confrontation with the Nazis.

Swiss historian Jean-Claude Favez, who conducted an 8-year review of the Red Cross records, says that even though the Red Cross knew by November 1942 about the Nazi's annihilation plans for the Jews – and even discussed it with U.S. officials – the group did nothing to inform the public, maintaining silence even in the face of pleas by Jewish groups.

Because the Red Cross was based in Geneva and largely funded by the Swiss government, it was very sensitive to Swiss wartime attitudes and policies. In October 1942, the Swiss government and the Red Cross' board of members vetoed a proposal by several Red Cross board members to condemn the persecution of civilians by the Nazis. For the rest of the war, the Red Cross took its cues from Switzerland in avoiding acts of opposition or confrontation with the Nazis.

On 12 March 1945, ICRC President Jacob Burckhardt received a message from SS General Ernst Kaltenbrunner accepting the ICRC's demand to allow delegates to visit the concentration camps. This agreement was bound by the condition that these delegates would have to stay in the camps until the end of the war. Ten delegates, among them

On 12 March 1945, ICRC President Jacob Burckhardt received a message from SS General Ernst Kaltenbrunner accepting the ICRC's demand to allow delegates to visit the concentration camps. This agreement was bound by the condition that these delegates would have to stay in the camps until the end of the war. Ten delegates, among them Louis Haefliger Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis ...

( Mauthausen Camp), Paul Dunant ( Theresienstadt Camp) and Victor Maurer ( Dachau Camp), accepted the assignment and visited the camps. Louis Haefliger prevented the forceful eviction or blasting of Mauthausen-Gusen by alerting American troops, thereby saving the lives of about 60,000 inmates. His actions were condemned by the ICRC because they were deemed as acting unduly on his own authority and risking the ICRC's neutrality. Only in 1990 was his reputation finally rehabilitated by ICRC President Cornelio Sommaruga.

In 1944, the ICRC received its second Nobel Peace Prize. As in World War I, it received the only Peace Prize awarded during the main period of war, 1939 to 1945. At the end of the war, the ICRC worked with national Red Cross societies to organize relief assistance to those countries most severely affected. In 1948, the Committee published a report reviewing its war-era activities from 1 September 1939 to 30 June 1947. Since January 1996, the ICRC archive for this period has been open to academic and public research.

Rest of the 20th century

In December 1948 the ICRC was invited, along with theIFRC

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) is a worldwide humanitarian aid organization that reaches 160 million people each year through its 192-member National Societies. It acts before, during and after disast ...

and AFSC, by the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

to take part in a $32 million emergency relief programme working with Palestinian refugees. The ICRC was given responsibility for West Bank and Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

.

On 12 August 1949, further revisions to the existing two Geneva Conventions were adopted. An additional convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea", now called the second Geneva Convention, was brought under the Geneva Convention umbrella as a successor to the 1907 Hague Convention X. The 1929 Geneva convention "relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" may have been the second Geneva Convention from a historical point of view (because it was actually formulated in Geneva), but after 1949 it came to be called the third Convention because it came later chronologically than the Hague Convention. Reacting to the experience of World War II, the Fourth Geneva Convention, a new Convention "relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War," was established. Also, the additional protocols of 8 June 1977 were intended to make the conventions apply to internal conflicts such as civil wars. Today, the four conventions and their added protocols contain more than 600 articles, a remarkable expansion when compared to the mere 10 articles in the first 1864 convention.

In celebration of its centennial in 1963, the ICRC, together with the League of Red Cross Societies

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) is a worldwide humanitarian aid organization that reaches 160 million people each year through its 192-member National Societies. It acts before, during and after disast ...

, received its third Nobel Peace Prize. Since 1993, non-Swiss individuals have been allowed to serve as Committee delegates abroad, a task which was previously restricted to Swiss citizens. Indeed, since then, the share of staff without Swiss citizenship has increased to about 35%.

On 16 October 1990, the UN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

decided to grant the ICRC observer status for its assembly sessions and sub-committee meetings, the first observer status given to a private organization. The resolution was jointly proposed by 138 member states and introduced by the Italian ambassador, Vieri Traxler

Christian "Bobo" Vieri (; born 12 July 1973) is an Italian former professional footballer who played as a centre forward.

Having been born in Italy, Vieri moved with his family to Australia as a child, before returning to Italy to pursue his p ...

, in memory of the organization's origins in the Battle of Solferino. An agreement with the Swiss government signed on 19 March 1993, affirmed the already long-standing policy of full independence of the committee from any possible interference by Switzerland. The agreement protects the full sanctity of all ICRC property in Switzerland including its headquarters and archive, grants members and staff legal immunity, exempts the ICRC from all taxes and fees, guarantees the protected and duty-free transfer of goods, services, and money, provides the ICRC with secure communication privileges at the same level as foreign embassies, and simplifies Committee travel in and out of Switzerland.

The ICRC continued its activities throughout the 1990s. It broke its customary media silence when it denounced the Rwandan genocide

The Rwandan genocide occurred between 7 April and 15 July 1994 during the Rwandan Civil War. During this period of around 100 days, members of the Tutsi minority ethnic group, as well as some moderate Hutu and Twa, were killed by armed Hutu ...

in 1994. It struggled to prevent the crimes that happened in and around Srebrenica in 1995 but admitted, "We must acknowledge that despite our efforts to help thousands of civilians forcibly expelled from the town and despite the dedication of our colleagues on the spot, the ICRC's impact on the unfolding of the tragedy was extremely limited." It went public once again in 2007 to decry "major human rights abuses" by Burma's military government including forced labour, starvation, and murder of men, women, and children.

The Holocaust memorial

By taking part in the 1995 ceremony to commemorate the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp, the President of the ICRC, Cornelio Sommaruga, sought to show that the organization was fully aware of the gravity ofThe Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europ ...

and the need to keep the memory of it alive, so as to prevent any repetition of it. He paid tribute to all those who had suffered or lost their lives during the war and publicly regretted the past mistakes and shortcomings of the Red Cross with regard to the victims of the concentration camps.

In 2002, an ICRC official outlined some of the lessons the organization has learned from the failure:

* from a legal point of view, the work that led to the adoption of the Geneva Convention relative to the protection of civilian persons in time of war;

* from an ethical point of view, the adoption of the declaration of the Fundamental Principles of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, building on the distinguished work of Max Huber and Jean Pictet, to prevent any more abuses such as those that occurred within the movement after Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

rose to power in 1933;

* on a political level, the ICRC's relationship with Switzerland was redesigned to ensure its independence;

* with a view to keeping memories alive, the ICRC accepted, in 1955, to take over the direction of the International Tracing Service

The Arolsen Archives – International Center on Nazi Persecution formerly the International Tracing Service (ITS), in German Internationaler Suchdienst, in French Service International de Recherches in Bad Arolsen, Germany, is an international ...

where records from concentration camps are maintained;

* finally, to establish the historical facts of the case, the ICRC invited Jean-Claude Favez to carry out an independent investigation of its activities on behalf of the victims of Nazi persecution, and gave him unfettered access to the ICRC archives relating to this period; out of concern for transparency, the ICRC also decided to give all other historians access to its archive

An archive is an accumulation of historical records or materials – in any medium – or the physical facility in which they are located.

Archives contain primary source documents that have accumulated over the course of an individual ...

s dating back more than 50 years; having gone over the conclusions of Favez's work, the ICRC acknowledged its past failings and expressed its regrets in this regard.

In an official statement made on 27 January 2005, the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the ICRC stated:

Auschwitz also represents the greatest failure in the history of the ICRC, aggravated by its lack of decisiveness in taking steps to aid the victims of Nazi persecution. This failure will remain part of the ICRC's memory, as will the courageous acts of individual ICRC delegates at the time.

Staff fatalities

At the end of theCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, the ICRC's work actually became more dangerous. In the 1990s, more delegates lost their lives than at any point in its history, especially when working in local and internal armed conflicts. These incidents often demonstrated a lack of respect for the rules of the Geneva Conventions and their protection symbols. Among the slain delegates were:

* Frédéric Maurice. He died on 19 May 1992 at the age of 39, one day after a Red Cross transport he was escorting was attacked in the former Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

n city of Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ; cyrl, Сарајево, ; ''see names in other languages'') is the capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its administrative limits. The Sarajevo metropolitan area including Sarajevo ...

.

* Fernanda Calado (Spain), Ingeborg Foss (Norway), Nancy Malloy (Canada), Gunnhild Myklebust (Norway), Sheryl Thayer (New Zealand), and Hans Elkerbout (Netherlands). They were shot at point-blank range while sleeping in the early hours of 17 December 1996 in the ICRC field hospital in the Chechen city of Nowije Atagi

Novye Atagi (russian: Но́вые Атаги́: ce, Жима АтагӀа, ''Ƶima Ataġa'') is a rural locality (a '' selo'') in Shalinsky District of the Chechen Republic, Russia, located south of Grozny. Population:

Novye Atagi is separ ...

near Grozny

Grozny ( rus, Грозный, p=ˈgroznɨj; ce, Соьлжа-ГӀала, translit=Sölƶa-Ġala), also spelled Groznyy, is the capital city of Chechnya, Russia.

The city lies on the Sunzha River. According to the 2010 census, it had a po ...

. Their murderers have never been caught and there was no apparent motive for the killings.

* Rita Fox (Switzerland), Véronique Saro (Democratic Republic of Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

, formerly Zaire), Julio Delgado (Colombia), Unen Ufoirworth (DR Congo), Aduwe Boboli (DR Congo), and Jean Molokabonge (DR Congo). On 26 April 2001, they were en route with two cars on a relief mission in the northeast of the Democratic Republic of Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

when they came under fatal fire from unknown attackers.

* Ricardo Munguia (El Salvador). He was working as a water engineer in Afghanistan and travelling from Kandahar

Kandahar (; Kandahār, , Qandahār) is a city in Afghanistan, located in the south of the country on the Arghandab River, at an elevation of . It is Afghanistan's second largest city after Kabul, with a population of about 614,118. It is the c ...

to Tirin Kot with local colleagues on 27 March 2003 when their car was stopped by unknown armed men. He was killed execution-style at point-blank range while his colleagues were allowed to escape. He was 39 years old. The killing prompted the ICRC to temporarily suspend operations across Afghanistan. Thereby the assumption that ICRC's reputation for neutrality and effective work in Afghanistan over the past thirty years would protect its delegates was shattered.

* Vatche Arslanian (Canada). Since 2001, he worked as a logistics coordinator for the ICRC mission in Iraq. He died when he was travelling through Baghdad together with members of the Iraqi Red Crescent. Their car accidentally came into the crossfire of fighting in the city.

* Nadisha Yasassri Ranmuthu (Sri Lanka). He was killed by unknown attackers on 22 July 2003, when his car was fired upon near the city of Hilla in the south of Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

.

* Emmerich Pregetter (Austria). He was an ICRC Logistics Specialist who was killed by a swarm of bees on 11 August 2008. Emmerich was participating in a field trip along with the ICRC Water and Habitat team on a convoy which was delivering construction material for reconstruction of a rural surgical health clinic in the area of Jebel Marra, West Darfur, Sudan.

In 2011, ICRC launched the Health Care In Danger campaign to highlight risks to humanitarian healthcare workers.

Characteristics

Swiss flag

The national flag of Switzerland (german: Schweizerfahne; french: drapeau de la Suisse; it, bandiera svizzera; rm, bandiera da la Svizra) displays a white cross in the centre of a square red field. The white cross is known as the Swiss cross ...

) with the words "COMITE INTERNATIONAL GENEVE" circling the cross.

Under the Geneva Convention, the red cross, red crescent and red crystal emblems provide protection for military medical services and relief workers in armed conflicts and is to be placed on humanitarian and medical vehicles and buildings. The original emblem that has a red cross on a white background is the exact reverse of the flag of neutral Switzerland. It was later supplemented by two others which are the Red Crescent, and the Red Crystal. The Red Crescent was adopted by the Ottoman Empire during the Russo-Turkish war and the Red Crystal by the governments in 2005, as an additional emblem devoid of any national, political or religious connotation.

Mission

The official mission statement says that: "The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is an impartial, neutral, and independent organization whose exclusively humanitarian mission is to protect the lives and dignity of victims of war and internal violence and to provide them with assistance." It also conducts and coordinates internationalrelief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

and works to promote and strengthen international humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), also referred to as the laws of armed conflict, is the law that regulates the conduct of war ('' jus in bello''). It is a branch of international law that seeks to limit the effects of armed conflict by pr ...

and universal humanitarian principles. The core tasks of the committee, which are derived from the Geneva Conventions and its own statutes are:

* to monitor compliance of warring parties with the Geneva Conventions

* to organize nursing and care for those who are wounded on the battlefield

* to supervise the treatment of prisoners of war and make confidential interventions with detaining authorities

* to help with the search for missing persons in an armed conflict ( tracing service)

* to organize protection and care for civil populations

* to act as a neutral intermediary between warring parties

The ICRC drew up seven fundamental principles in 1965 that were adopted by the entire Red Cross Movement. They are humanity, impartiality, neutrality, independence, volunteerism, unity, and universality.

Legal status

The ICRC is the only institution explicitly named ininternational humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), also referred to as the laws of armed conflict, is the law that regulates the conduct of war ('' jus in bello''). It is a branch of international law that seeks to limit the effects of armed conflict by pr ...

as a controlling authority. The legal mandate of the ICRC stems from the four Geneva Conventions

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conv ...

of 1949, as well as its own Statutes. The ICRC also undertakes tasks that are not specifically mandated by law, such as visiting political prisoners outside of conflict and providing relief in natural disasters.

The ICRC is a private Swiss association that has enjoyed various degrees of special privileges and legal immunities within the territory of Switzerland for many years. On 19 March 1993, a legal foundation for this special treatment was created by a formal agreement between the Swiss government and the ICRC. This agreement protects the full sanctity of all ICRC property in Switzerland including its headquarters and archive, grants members and staff legal immunity, exempts the ICRC from all taxes and fees, guarantees protected and duty-free transfer of goods, services, and money, provides the ICRC with secure communication privileges at the same level as foreign embassies, and simplifies Committee travel in and out of Switzerland. On the other hand, Switzerland does not recognize ICRC-issued passports.

Contrary to popular belief, the ICRC is not a sovereign entity like the Sovereign Military Order of Malta

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), officially the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta ( it, Sovrano Militare Ordine Ospedaliero di San Giovanni di Gerusalemme, di Rodi e di Malta; ...

. The ICRC limits its membership to Swiss nationals only, and also it does not have a policy of open and unrestricted membership for individuals as its new members are selected by the Committee itself (a process called cooptation). However, since the early 1990s, the ICRC employs persons from all over the world to serve in its field mission and at Headquarters. In 2007, almost half of ICRC staff was non-Swiss. The ICRC has special privileges and legal immunities in many countries, based on national law in these countries, based on agreements between the ICRC and the respective governments, or, in some cases, based on international jurisprudence (such as the right of ICRC delegates not to bear witness in front of international tribunals).

Legal basis

The ICRC's operations are generally based oninternational humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), also referred to as the laws of armed conflict, is the law that regulates the conduct of war ('' jus in bello''). It is a branch of international law that seeks to limit the effects of armed conflict by pr ...

, primarily comprising the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, their two Additional Protocols of 1977 and Additional Protocol III of 2005, the Statutes of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, and the resolutions of the International Conferences of the Red Cross and Red Crescent.

International humanitarian law is founded upon the Geneva conventions, the first of which was signed in 1864 by 16 countries. The First Geneva Convention of 1949 covers the protection for the wounded and sick of armed conflict on land. The Second Geneva Convention asks for the protection and care for the wounded, sick and shipwrecked of armed conflict at sea. The Third Geneva Convention concerns the treatment of prisoners of war. The Fourth Geneva Convention concerns the protection of civilians in time of war. In addition, there are many more customary international laws that come into effect when necessary.

Funding and financial matters

The 2010 budget of the ICRC amounts to about 1156 million Swiss francs. All payments to the ICRC are voluntary and are received as donations based on two types of appeals issued by the committee: an annual ''Headquarters Appeal'' to cover its internal costs and ''Emergency Appeals'' for its individual missions. The total budget for 2009 consists of about 996.9 million Swiss Francs (85% of the total) for field work and 168.6 million Swiss Francs (15%) for internal costs. In 2009, the budget for field work increased by 6.9% and the internal budget by 4.4% compared to 2008, primarily due to above-average increases in the number and scope of its missions in Africa. Most of the ICRC's funding comes from Switzerland and the United States, with other European states and the EU close behind. Together with Australia, Canada, Japan, and New Zealand, they contribute about 80–85% of the ICRC's budget. About 3% comes from private gifts, and the rest comes from national Red Cross societies.Responsibilities within the movement

The ICRC is responsible for legally recognizing a relief society as an official national Red Cross or Red Crescent society and thus accepting it into the movement. The exact rules for recognition are defined in the statutes of the movement. After recognition by the ICRC, a national society is admitted as a member to the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (the Federation, or IFRC). The ICRC and the Federation cooperate with the individual national societies in their international missions, especially with human, material, and financial resources and organizing on-site logistics. According to the 1997 Seville Agreement, the ICRC is the lead Red Cross agency in conflicts while other organizations within the movement take the lead in non-war situations. National societies will be given the lead especially when a conflict is happening within their own country.Organization

The ICRC is headquartered in the Swiss city ofGeneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

and has external offices called Delegations (or in rare cases, “missions”) in about eighty countries. Each delegation is under the responsibility of a Head of delegation who is the official representative of the ICRC in the country. Of its 3,000 professional employees, roughly 1,000 work in its Geneva headquarters and 2,000 expatriates work in the field. About half of the field workers serve as delegates managing ICRC operations, while the other half are specialists such as doctors, agronomists, engineers, or interpreters. In the delegations, the international staff are assisted by some 15,000 national employees, bringing the total staff under the authority of the ICRC to roughly 18,000. Delegations also often work closely with the National Red Cross Societies of the countries where they are based, and thus can call on the volunteers of the National Red Cross to assist in some of the ICRC's operations.

The organizational structure of the ICRC is not well understood by outsiders. This is partly because of organizational secrecy, but also because the structure itself has been prone to frequent change. The Assembly and Presidency are two long-standing institutions, but the Assembly Council and Directorate were created only in the latter part of the twentieth century. Decisions are often made in a collective way, so authority and power relationships are not set in stone. Today, the leading organs are the Directorate and the Assembly.

Directorate

The Directorate is the executive body of the ICRC. It attends to the daily management of the ICRC, whereas the Assembly sets policy. The Directorate consists of a Director-General and five directors in the areas of "Operations", "Human Resources", "Financial Resources and Logistics ", "Communication and Information Management", and "International Law and Cooperation within the Movement". The members of the Directorate are appointed by the Assembly to serve for four years. The Director-General has assumed more personal responsibility in recent years, much like a CEO, where he was formerly more of a first among equals at the Directorate.Assembly

The Assembly (also called the Committee) convenes on a regular basis and is responsible for defining aims, guidelines, and strategies and for supervising the financial matters of the committee. The Assembly has a membership of a maximum of twenty-five Swiss citizens. Members must speak the house language of French, but many also speak English and German as well. These Assembly members are co-opted for a period of four years, and there is no limit to the number of terms an individual member can serve. A three-quarters majority vote from all members is required for re-election after the third term, which acts as a motivation for members to remain active and productive.

In the early years, every Committee member was Genevan, Protestant,

The Assembly (also called the Committee) convenes on a regular basis and is responsible for defining aims, guidelines, and strategies and for supervising the financial matters of the committee. The Assembly has a membership of a maximum of twenty-five Swiss citizens. Members must speak the house language of French, but many also speak English and German as well. These Assembly members are co-opted for a period of four years, and there is no limit to the number of terms an individual member can serve. A three-quarters majority vote from all members is required for re-election after the third term, which acts as a motivation for members to remain active and productive.

In the early years, every Committee member was Genevan, Protestant, white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

, and male. The first woman, the historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the st ...

and legal scholar Renée-Marguerite Cramer (1887-1963), was co-opted in 1918, but resigned already in 1922 when she moved to Germany. She was succeeded by the nurse

Nursing is a profession within the health care sector focused on the care of individuals, families, and communities so they may attain, maintain, or recover optimal health and quality of life. Nurses may be differentiated from other health ...

and suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to member ...

Pauline Chaponnière-Chaix

Pauline Chaponnière-Chaix ( Geneva, 1 November 1850 – Geneva, 6 December 1934) was a Swiss nurse, feminist and suffragette. She was one of four employees of the International Committee of the Red Cross after World War I, and served as presid ...

(1850-1934). The third female member was the music educator

Music education is a field of practice in which educators are trained for careers as elementary or secondary music teachers, school or music conservatory ensemble directors. Music education is also a research area in which scholars do original ...

Suzanne Ferrière (1886-1970) in 1925, followed by the nurses Lucie Odier (1886-1984) in 1930 and Renée Bordier (1902-2000) in 1938.

In recent decades, several women have attained the Vice Presidency, and the female proportion after the Cold War