Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of

infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children,

its main purpose is the prevention of resources being spent on weak or disabled offspring. Unwanted infants were normally abandoned to die of exposure, but in some societies they were deliberately killed.

Infanticide is now widely illegal, but in some places the practice is tolerated or the prohibition is not strictly enforced.

Most

Stone Age human societies routinely practiced infanticide, and estimates of children killed by infanticide in the

Mesolithic and

Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

eras vary from 15 to 50 percent. Infanticide continued to be common in most societies after the historical era began, including

ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of Classical Antiquity, classical antiquity ( AD 600), th ...

,

ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

, the

Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

, ancient

China, ancient

Japan,

Aboriginal Australia

The prehistory of Australia is the period between the first human habitation of the Australian continent and the colonisation of Australia in 1788, which marks the start of consistent written documentation of Australia. This period has been vari ...

,

Native Americans, and

Native Alaskan

Native may refer to:

People

* Jus soli, citizenship by right of birth

* Indigenous peoples, peoples with a set of specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory

** Native Americans (disambiguation)

In arts and entert ...

s.

Infanticide became forbidden in

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

and the

Near East during the 1st millennium.

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

forbade infanticide from its earliest times, which led

Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

and

Valentinian I

Valentinian I ( la, Valentinianus; 32117 November 375), sometimes called Valentinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 364 to 375. Upon becoming emperor, he made his brother Valens his co-emperor, giving him rule of the eastern provinces. Val ...

to ban infanticide across the Roman Empire in the 4th century. Yet, infanticide was not unacceptable in some wars and infanticide in Europe reached its peak during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

(1939-45), during

the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

and the

T4 Program. The practice ceased in

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

in the 7th century after the founding of

Islam, since the

Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

prohibits infanticide. Infanticide of male babies had become uncommon in China by the

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peo ...

(1368–1644), whereas infanticide of female babies became more common during the

One-Child Policy

The term one-child policy () refers to a population planning initiative in China implemented between 1980 and 2015 to curb the country's population growth by restricting many families to a single child. That initiative was part of a much br ...

era (1979–2015). During the period of

Company rule in India

Company rule in India (sometimes, Company ''Raj'', from hi, rāj, lit=rule) refers to the rule of the British East India Company on the Indian subcontinent. This is variously taken to have commenced in 1757, after the Battle of Plassey, when ...

, the

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

attempted to eliminate infanticide but were only partially successful, and female infanticide in some parts of India still continues. Infanticide is now very rare in industrialised countries but may persist elsewhere.

Parental infanticide researchers have found that mothers are more likely to commit infanticide. In the case special case of

neonaticide

Neonaticide is the deliberate act of a parent murdering their own child during the first 24 hours of life. As a noun, the word "neonaticide" may also refer to anyone who practices or who has practiced this.

Neonaticide is relatively rare in ...

(murder in the first 24 hours of life), mothers account for almost all the perpetrators. Fatherly cases of neonaticide are so rare that they are individually recorded.

History

The practice of infanticide has taken many forms over time.

Child sacrifice

Child sacrifice is the ritualistic killing of children in order to please or appease a deity, supernatural beings, or sacred social order, tribal, group or national loyalties in order to achieve a desired result. As such, it is a form of human ...

to supernatural figures or forces, such as that believed to have been practiced in ancient

Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

, may be only the most notorious example in the

ancient world

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

.

A frequent method of infanticide in ancient

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

and

Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

was simply to

abandon the infant, leaving it to die by exposure (i.e.,

hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

, hunger, thirst, or animal attack).

Justin Martyr

Justin Martyr ( el, Ἰουστῖνος ὁ μάρτυς, Ioustinos ho martys; c. AD 100 – c. AD 165), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian apologist and philosopher.

Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and ...

, ''First Apology

The ''First Apology'' was an early work of Christian apologetics addressed by Justin Martyr to the Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius. In addition to arguing against the persecution of individuals solely for being Christian, Justin also provides the ...

.''

On at least one island in

Oceania

Oceania (, , ) is a geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern and Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of and a population of around 44.5 million ...

, infanticide was carried out until the 20th century by suffocating the infant,

[ Diamond, Jared (2005). '' Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed''. .] while in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and in the

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, ( Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The adm ...

it was carried out by sacrifice (see below).

Paleolithic and Neolithic

Many Neolithic groups routinely resorted to infanticide in order to control their numbers so that their lands could support them.

Joseph Birdsell believed that infanticide rates in

prehistoric times

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use of ...

were between 15% and 50% of the total number of births, while Laila Williamson estimated a lower rate ranging from 15% to 20%.

Both

anthropologists believed that these high rates of infanticide persisted until the development of agriculture during the

Neolithic Revolution.

Comparative anthropologists have calculated that 50% of female newborn babies were killed by their parents during the

Paleolithic era. From the infants

hominid skulls (e.g.

Taung child skull) that had been traumatized, has been proposed

cannibalism by Raymond A. Dart. The children were not necessarily actively killed, but neglect and intentional malnourishment may also have occurred, as proposed by Vicente Lull as an explanation for an apparent surplus of men and the below average height of women in prehistoric

Menorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its capi ...

.

In ancient history

In the New World

Archaeologists have uncovered physical evidence of

child sacrifice

Child sacrifice is the ritualistic killing of children in order to please or appease a deity, supernatural beings, or sacred social order, tribal, group or national loyalties in order to achieve a desired result. As such, it is a form of human ...

at several locations.

Some of the best attested examples are the diverse rites which were part of the religious practices in

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica ...

and the

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, ( Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The adm ...

.

In the Old World

Three thousand bones of young children, with evidence of sacrificial rituals, have been found in

Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

.

Pelasgians offered a sacrifice of every tenth child during difficult times. Many remains of children have been found in

Gezer

Gezer, or Tel Gezer ( he, גֶּזֶר), in ar, تل الجزر – Tell Jezar or Tell el-Jezari is an archaeological site in the foothills of the Judaean Mountains at the border of the Shfela region roughly midway between Jerusalem and Tel Av ...

excavations with signs of sacrifice. Child skeletons with the marks of sacrifice have been found also in Egypt dating 950–720 BCE. In

Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the cla ...

"

hild

Hild or Hildr may refer to:

* Hildr or Hild is one of the Valkyries in Norse mythology, a personification of battle

* Hild or Hilda of Whitby is a Christian saint who was a British abbess and nun in the Middle Ages

* Hild (Oh My Goddess!), the ult ...

sacrifice in the ancient world reached its infamous zenith".

Besides the Carthaginians, other

Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

, and the

Canaanites,

Moabites and

Sepharvites offered their first-born as a sacrifice to their gods.

=Ancient Egypt

=

In Egyptian households, at all social levels, children of both sexes were valued and there is no evidence of infanticide. The

religion of the ancient Egyptians forbade infanticide and during the

Greco-Roman period they rescued abandoned babies from manure heaps, a common method of infanticide by Greeks or Romans, and were allowed to either adopt them as foundling or raise them as slaves, often giving them names such as "copro -" to memorialize their rescue.

Strabo considered it a peculiarity of the Egyptians that every child must be reared.

Diodorus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

indicates infanticide was a punishable offence. Egypt was heavily dependent on the annual flooding of the Nile to irrigate the land and in years of low inundation, severe famine could occur with breakdowns in social order resulting, notably between and . Instances of cannibalism are recorded during these periods, but it is unknown if this happened during the pharaonic era of ancient Egypt. Beatrix Midant-Reynes describes human sacrifice as having occurred at Abydos in the early dynastic period ( ), while

Jan Assmann

Jan Assmann (born Johann Christoph Assmann; born 7 July 1938) is a German Egyptologist.

Life and works

Assmann studied Egyptology and classical archaeology in Munich, Heidelberg, Paris, and Göttingen. In 1966–67, he was a fellow of the German ...

asserts there is no clear evidence of human sacrifice ever happening in ancient Egypt.

=Carthage

=

According to Shelby Brown,

Carthaginian The term Carthaginian ( la, Carthaginiensis ) usually refers to a citizen of Ancient Carthage.

It can also refer to:

* Carthaginian (ship), a three-masted schooner built in 1921

* Insurgent privateers; nineteenth-century South American privateers, ...

s, descendants of the

Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns, sacrificed infants to their gods.

Charred bones of hundreds of infants have been found in Carthaginian archaeological sites. One such area harbored as many as 20,000 burial

urn

An urn is a vase, often with a cover, with a typically narrowed neck above a rounded body and a footed pedestal. Describing a vessel as an "urn", as opposed to a vase or other terms, generally reflects its use rather than any particular shape or ...

s.

Skeptics suggest that the bodies of children found in Carthaginian and Phoenician cemeteries were merely the cremated remains of children that died naturally.

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

( ) mentions the practice, as do

Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

,

Orosius, Diodorus Siculus and

Philo

Philo of Alexandria (; grc, Φίλων, Phílōn; he, יְדִידְיָה, Yəḏīḏyāh (Jedediah); ), also called Philo Judaeus, was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

Philo's de ...

. The

Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;["Tanach"](_blank)

'' Tophet

In the Hebrew Bible, Tophet or Topheth ( hbo, תֹּפֶת, Tōp̄eṯ; grc-gre, Ταφέθ, taphéth; la, Topheth) is a location in Jerusalem in the Valley of Hinnom (Gehenna), where worshipers engaged in a ritual involving "passing a child thro ...

(from the Hebrew ''taph'' or ''toph'', to burn) by the

Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

ites. Writing in the ,

Kleitarchos, one of the historians of

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, described that the infants rolled into the flaming pit.

Diodorus Siculus wrote that babies were roasted to death inside the burning pit of the god

Baal Hamon, a bronze statue.

=Greece and Rome

=

The historical Greeks considered the practice of adult and child sacrifice

barbarous, however, the exposure of newborns was widely practiced in

ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of Classical Antiquity, classical antiquity ( AD 600), th ...

. It was advocated by Aristotle in the case of congenital deformity: "As to the exposure of children, let there be a law that no deformed child shall live." In Greece, the decision to expose a child was typically the father's, although in Sparta the decision was made by a group of elders. Exposure was the preferred method of disposal, as that act in itself was not considered to be murder; moreover, the exposed child technically had a chance of being rescued by the gods or any passersby. This very situation was a recurring motif in

Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities ...

.

To notify the neighbors of a birth of a child, a woolen strip was hung over the front door to indicate a female baby and an olive branch to indicate a boy had been born. Families did not always keep their new child. After a woman had a baby, she would show it to her husband. If the husband accepted it, it would live, but if he refused it, it would die. Babies would often be rejected if they were illegitimate, unhealthy or deformed, the wrong sex, or too great a burden on the family. These babies would not be directly killed, but put in a clay pot or jar and deserted outside the front door or on the roadway. In ancient Greek religion, this practice took the responsibility away from the parents because the child would die of natural causes, for example, hunger, asphyxiation or exposure to the elements.

The practice was prevalent in

ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

, as well.

Philo

Philo of Alexandria (; grc, Φίλων, Phílōn; he, יְדִידְיָה, Yəḏīḏyāh (Jedediah); ), also called Philo Judaeus, was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

Philo's de ...

was the first philosopher to speak out against it. A letter from a Roman citizen to his sister, or a pregnant wife from her husband,

dating from , demonstrates the casual nature with which infanticide was often viewed:

:"I am still in Alexandria. ... I beg and plead with you to take care of our little child, and as soon as we receive wages, I will send them to you. In the meantime, if (good fortune to you!) you give birth, if it is a boy, let it live; if it is a girl, expose it.", ''"If you give birth to a boy, keep it. If it is a girl, expose it. Try not to worry. I'll send the money as soon as we get paid."''

In some periods of

Roman history it was traditional for a newborn to be brought to the ''

pater familias

The ''pater familias'', also written as ''paterfamilias'' (plural ''patres familias''), was the head of a Roman family. The ''pater familias'' was the oldest living male in a household, and could legally exercise autocratic authority over his ext ...

'', the family

patriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and in certai ...

, who would then decide whether the child was to be kept and raised, or left to die by exposure.

[John Crossan, ''The Essential Jesus: Original Sayings and Earliest Images'', p. 151 (Castle, 1994, 1998) ] The

Twelve Tables

The Laws of the Twelve Tables was the legislation that stood at the foundation of Roman law. Formally promulgated in 449 BC, the Tables consolidated earlier traditions into an enduring set of laws.Crawford, M.H. 'Twelve Tables' in Simon Hornblowe ...

of

Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Ju ...

obliged him to put to death a child that was visibly deformed. The concurrent practices of

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and infanticide contributed to the "background noise" of the

crises during the Republic.

Infanticide became a

capital offense

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

in Roman law in 374, but offenders were rarely if ever prosecuted.

According to mythology,

Romulus and Remus, twin infant sons of the war god

Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

, survived near-infanticide after being tossed into the Tiber River. According to the myth, they were raised by wolves, and later founded the city of Rome.

=Middle Ages

=

Whereas theologians and clerics preached sparing their lives, newborn abandonment continued as registered in both the literature record and in legal documents.

According to

William Lecky, exposure in the

early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, as distinct from other forms of infanticide, "was practiced on a gigantic scale with absolute impunity, noticed by writers with most frigid indifference and, at least in the case of destitute parents, considered a very venial offence".

The first foundling house in Europe was established in

Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

in 787 on account of the high number of infanticides and out-of-wedlock births. The

Hospital of the Holy Spirit in Rome was founded by

Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 ...

because women were throwing their infants into the

Tiber river

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by the Ri ...

.

Unlike other European regions, in the Middle Ages the German mother had the right to expose the newborn.

In the High Middle Ages, abandoning unwanted children finally eclipsed infanticide. Unwanted children were left at the door of church or abbey, and the clergy was assumed to take care of their upbringing. This practice also gave rise to the first

orphanage

An orphanage is a residential institution, total institution or group home, devoted to the care of orphans and children who, for various reasons, cannot be cared for by their biological families. The parents may be deceased, absent, or ab ...

s.

However, very high sex ratios were common in even late medieval Europe, which may indicate sex-selective infanticide.

=Judaism

=

Judaism prohibits infanticide, and has for some time, dating back to at least early

Common Era

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the o ...

. Roman historians wrote about the ideas and customs of other peoples, which often diverged from their own.

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

recorded that the Jews "take thought to increase their numbers, for they regard it as a crime to kill any late-born children".

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

, whose works give an important insight into 1st-century Judaism, wrote that God "forbids women to cause abortion of what is begotten, or to destroy it afterward".

=Pagan European tribes

=

In his book ''

Germania'',

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

wrote in that the ancient

Germanic tribes

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and e ...

enforced a similar prohibition. He found such mores remarkable and commented: "To restrain generation and the increase of children, is esteemed

y the Germansan abominable sin, as also to kill infants newly born." It has become clear over the millennia, though, that Tacitus' description was inaccurate; the consensus of modern scholarship significantly differs.

John Boswell

John Eastburn Boswell (March 20, 1947December 24, 1994) was an American historian and a full professor at Yale University. Many of Boswell's studies focused on the issue of religion and homosexuality, specifically Christianity and homosexuality. ...

believed that in ancient Germanic tribes unwanted children were exposed, usually in the forest.

"It was the custom of the

eutonicpagans, that if they wanted to kill a son or daughter, they would be killed before they had been given any food."

Usually children born out of wedlock were disposed of that way.

In his highly influential ''Pre-historic Times'',

John Lubbock described burnt bones indicating the practice of child sacrifice in pagan Britain.

The last canto, ''Marjatan poika'' (Son of Marjatta), of

Finnish

Finnish may refer to:

* Something or someone from, or related to Finland

* Culture of Finland

* Finnish people or Finns, the primary ethnic group in Finland

* Finnish language, the national language of the Finnish people

* Finnish cuisine

See also ...

national epic ''

Kalevala

The ''Kalevala'' ( fi, Kalevala, ) is a 19th-century work of epic poetry compiled by Elias Lönnrot from Karelian and Finnish oral folklore and mythology, telling an epic story about the Creation of the Earth, describing the controversies and ...

'' describes assumed infanticide.

Väinämöinen

Väinämöinen () is a demigod, hero and the central character in Finnish folklore and the main character in the national epic ''Kalevala'' by Elias Lönnrot. Väinämöinen was described as an old and wise man, and he possessed a potent, m ...

orders the infant

bastard

Bastard may refer to:

Parentage

* Illegitimate child, a child born to unmarried parents

** Bastard (law of England and Wales), illegitimacy in English law

People People with the name

* Bastard (surname), including a list of people with that na ...

son of Marjatta to be drowned in a

marsh

A marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous rather than woody plant species.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p Marshes can often be found a ...

.

The ''

Íslendingabók

''Íslendingabók'' (, Old Norse pronunciation: , ''Book of Icelanders''; ) is a historical work dealing with early Icelandic history. The author was an Icelandic priest, Ari Þorgilsson, working in the early 12th century. The work originally ex ...

'', the main source for the early history of

Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

, recounts that on the

Conversion of Iceland to Christianity in 1000 it was provided – in order to make the transition more palatable to Pagans – that "the old laws allowing exposure of newborn children will remain in force".

However, this provision – among other concessions made at the time to the Pagans – was abolished some years later.

Christianity

Christianity explicitly rejects infanticide. The ''Teachings of the

Apostles'' or ''

Didache'' said "thou shalt not kill a child by

abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pre ...

, neither shalt thou slay it when born". The ''

Epistle of Barnabas

The ''Epistle of Barnabas'' ( el, Βαρνάβα Ἐπιστολή) is a Greek epistle written between AD 70 and 132. The complete text is preserved in the 4th-century ''Codex Sinaiticus'', where it appears immediately after the New Testament a ...

'' stated an identical command, both thus conflating abortion and infanticide. Apologists

Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

,

Athenagoras,

Minucius Felix

__NOTOC__

Marcus Minucius Felix (died c. 250 AD in Rome) was one of the earliest of the Latin apologists for Christianity.

Nothing is known of his personal history, and even the date at which he wrote can be only approximately ascertained as betwe ...

,

Justin Martyr

Justin Martyr ( el, Ἰουστῖνος ὁ μάρτυς, Ioustinos ho martys; c. AD 100 – c. AD 165), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian apologist and philosopher.

Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and ...

and

Lactantius also maintained that exposing a baby to death was a wicked act.

In 318,

Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

considered infanticide a crime, and in 374,

Valentinian I

Valentinian I ( la, Valentinianus; 32117 November 375), sometimes called Valentinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 364 to 375. Upon becoming emperor, he made his brother Valens his co-emperor, giving him rule of the eastern provinces. Val ...

mandated the rearing of all children (exposing babies, especially girls, was still common). The

Council of Constantinople declared that infanticide was homicide, and in 589, the

Third Council of Toledo

The Third Council of Toledo (589) marks the entry of Visigothic Spain into the Catholic Church, and is known for codifying the filioque clause into Western Christianity."Filioque." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. ...

took measures against the custom of killing their own children.

Arabia

Some Muslim sources allege that

pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia ( ar, شبه الجزيرة العربية قبل الإسلام) refers to the Arabian Peninsula before the emergence of Islam in 610 CE.

Some of the settled communities developed into distinctive civilizations. Informatio ...

n society practiced infanticide as a form of "post-partum birth control".

Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles ...

, ''Children'' The word ''waʾd'' was used to describe the practice.

[Donna Lee Bowen, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, Infanticide] These sources state that infanticide was practiced either out of destitution (thus practiced on males and females alike), or as "disappointment and fear of social disgrace felt by a father upon the birth of a daughter".

Some authors believe that there is little evidence that infanticide was prevalent in pre-Islamic

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

or early

Muslim history

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

, except for the case of the

Tamim tribe, who practiced it during severe famine according to Islamic sources. Others state that "female infanticide was common all over Arabia during this period of time" (pre-Islamic Arabia), especially by burying alive a female newborn.

A tablet discovered in

Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

, forbidding the people of a certain town from engaging in the practice, is the only written reference to infanticide within the peninsula in pre-Islamic times.

Islam

Infanticide is explicitly

prohibited by the Qur'an.

"And do not kill your children for fear of poverty; We give them sustenance and yourselves too; surely to kill them is a great wrong."

Together with

polytheism

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, t ...

and

homicide, infanticide is regarded as a grave sin (see and ).

Infanticide is also implicitly denounced in the story of Pharaoh's slaughter of the male children of Israelites (see ; ; ; ; ; ).

Ukraine and Russia

Infanticide may have been practiced as human sacrifice, as part of the

pagan cult of

Perun

In Slavic mythology, Perun (Cyrillic: Перýн) is the highest god of the pantheon and the god of sky, thunder, lightning, storms, rain, law, war, fertility and oak trees. His other attributes were fire, mountains, wind, iris, eagle, f ...

.

Ibn Fadlan

Aḥmad ibn Faḍlān ibn al-ʿAbbās ibn Rāšid ibn Ḥammād, ( ar, أحمد بن فضلان بن العباس بن راشد بن حماد; ) commonly known as Ahmad ibn Fadlan, was a 10th-century Muslim traveler, famous for his account of hi ...

describes sacrificial practices at the time of his trip to Kiev Rus (present-day Ukraine) in 921–922, and describes an incident of a woman voluntarily sacrificing her life as part of a

funeral rite

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect th ...

for a prominent leader, but makes no mention of infanticide. The

Primary Chronicle, one of the most important literary sources before the 12th century, indicates that human sacrifice to idols may have been introduced by

Vladimir the Great

Vladimir I Sviatoslavich or Volodymyr I Sviatoslavych ( orv, Володимѣръ Свѧтославичь, ''Volodiměrъ Svętoslavičь'';, ''Uladzimir'', russian: Владимир, ''Vladimir'', uk, Володимир, ''Volodymyr''. Se ...

in 980. The same Vladimir the Great formally converted Kiev Rus into

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

just 8 years later, but pagan cults continued to be practiced clandestinely in remote areas as late as the 13th century.

American explorer

George Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly histo ...

noted that among the

Koryaks

Koryaks () are an indigenous people of the Russian Far East, who live immediately north of the Kamchatka Peninsula in Kamchatka Krai and inhabit the coastlands of the Bering Sea. The cultural borders of the Koryaks include Tigilsk in the south ...

, a

Mongoloid

Mongoloid () is an obsolete racial grouping of various peoples indigenous to large parts of Asia, the Americas, and some regions in Europe and Oceania. The term is derived from a now-disproven theory of biological race. In the past, other terms ...

people of north-eastern

Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

, infanticide was still common in the nineteenth century. One of a pair of twins was always sacrificed.

Great Britain

Infanticide (as a crime) gained both popular and bureaucratic significance in

Victorian Britain. By the mid-19th century, in the context of criminal lunacy and the

insanity defence

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to an episodic psychiatric disease at the time of the ...

, killing one's own child(ren) attracted ferocious debate, as the role of women in society was defined by motherhood, and it was thought that any woman who murdered her own child was by definition insane and could not be held responsible for her actions. Several cases were subsequently highlighted during the

Royal Commission on Capital Punishment 1864–66

The Royal Commission on Capital Punishment was a royal commission on capital punishment in the United Kingdom which worked from 1864 to 1866. It was chaired by Charles Gordon-Lennox, 6th Duke of Richmond. Commissioners disagreed on the question ...

, as a particular felony where an effective avoidance of the

death penalty had informally begun.

The

New Poor Law Act of 1834 ended

parish relief for unmarried mothers and allowed fathers of illegitimate children to avoid paying for "child support". Unmarried mothers then received little assistance and the poor were left with the option either entering the

workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

, prostitution, infanticide or abortion. By the middle of the century infanticide was common for social reasons, such as illegitimacy, and the introduction of

child life insurance Child life insurance is a form of permanent life insurance that insures the life of a minor. It is usually purchased to protect a family against the sudden and unexpected costs of a child's funeral or burial and to secure inexpensive and guaranteed ...

additionally encouraged some women to kill their children for gain. Examples are

Mary Ann Cotton

Mary Ann Cotton (' Robson; 31 October 1832 – 24 March 1873) was an English convicted murderer who was executed for poisoning her stepson. Despite her sole conviction for murder, she is believed to have been a serial killer who killed many ...

, who murdered many of her 15 children as well as three husbands,

Margaret Waters

Margaret Waters, otherwise known as Willis, was an English murderer hanged by executioner William Calcraft on 11 October 1870 at Horsemonger Lane Gaol (also known as Surrey County Gaol) in London.

Waters was born in 1835 and lived in Brixton.

...

, the 'Brixton Baby Farmer', a professional

baby-farmer who was found guilty of infanticide in 1870, Jessie King hanged in 1889,

Amelia Dyer

Amelia Elizabeth Dyer (née Hobley; 1836 – 10 June 1896) was an English serial killer who murdered infants in her care over a thirty-year period during the Victorian era of the United Kingdom. , the 'Angel Maker', who murdered over 400 babies in her care, and

Ada Chard-Williams, a baby farmer who was later hanged at Newgate prison.

The Times reported that 67 infants were murdered in London in 1861 and 150 more recorded as "found dead", many of which were found on the streets. Another 250 were suffocated, half of them not recorded as accidental deaths. The report noted that "infancy in London has to creep into life in the midst of foes."

Recording a birth as a

still-birth was also another way of concealing infanticide because still-births did not need to be registered until 1926 and they did not need to be buried in public cemeteries. In 1895 ''The Sun'' (London) published an article "Massacre of the Innocents" highlighting the dangers of baby-farming, in the recording of stillbirths and quoting

Braxton-Hicks, the London Coroner, on lying-in houses: "I have not the slightest doubt that a large amount of crime is covered by the expression 'still-birth'. There are a large number of cases of what are called newly-born children, which are found all over England, more especially in London and large towns, abandoned in streets, rivers, on commons, and so on." He continued "a great deal of that crime is due to what are called lying-in houses, which are not registered, or under the supervision of that sort, where the people who act as midwives constantly, as soon as the child is born, either drop it into a pail of water or smother it with a damp cloth. It is a very common thing, also, to find that they bash their heads on the floor and break their skulls."

The last British woman to be executed for infanticide of her own child was

Rebecca Smith, who was hanged in Wiltshire in 1849.

The Infant Life Protection Act of 1897 required local authorities to be notified within 48 hours of changes in custody or the death of children under seven years. Under the

Children's Act of 1908 "no infant could be kept in a home that was so unfit and so overcrowded as to endanger its health, and no infant could be kept by an unfit nurse who threatened, by neglect or abuse, its proper care, and maintenance."

Asia

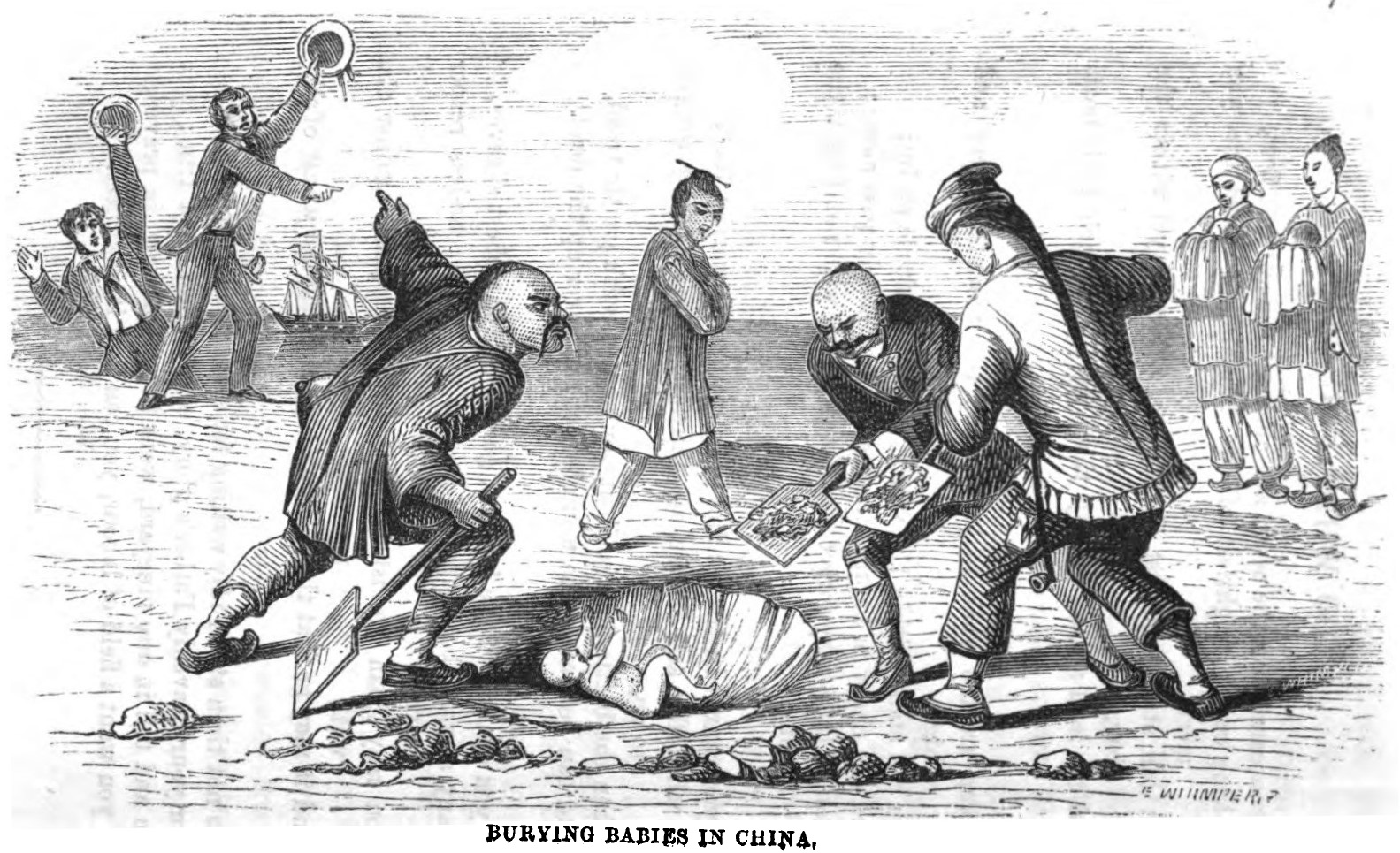

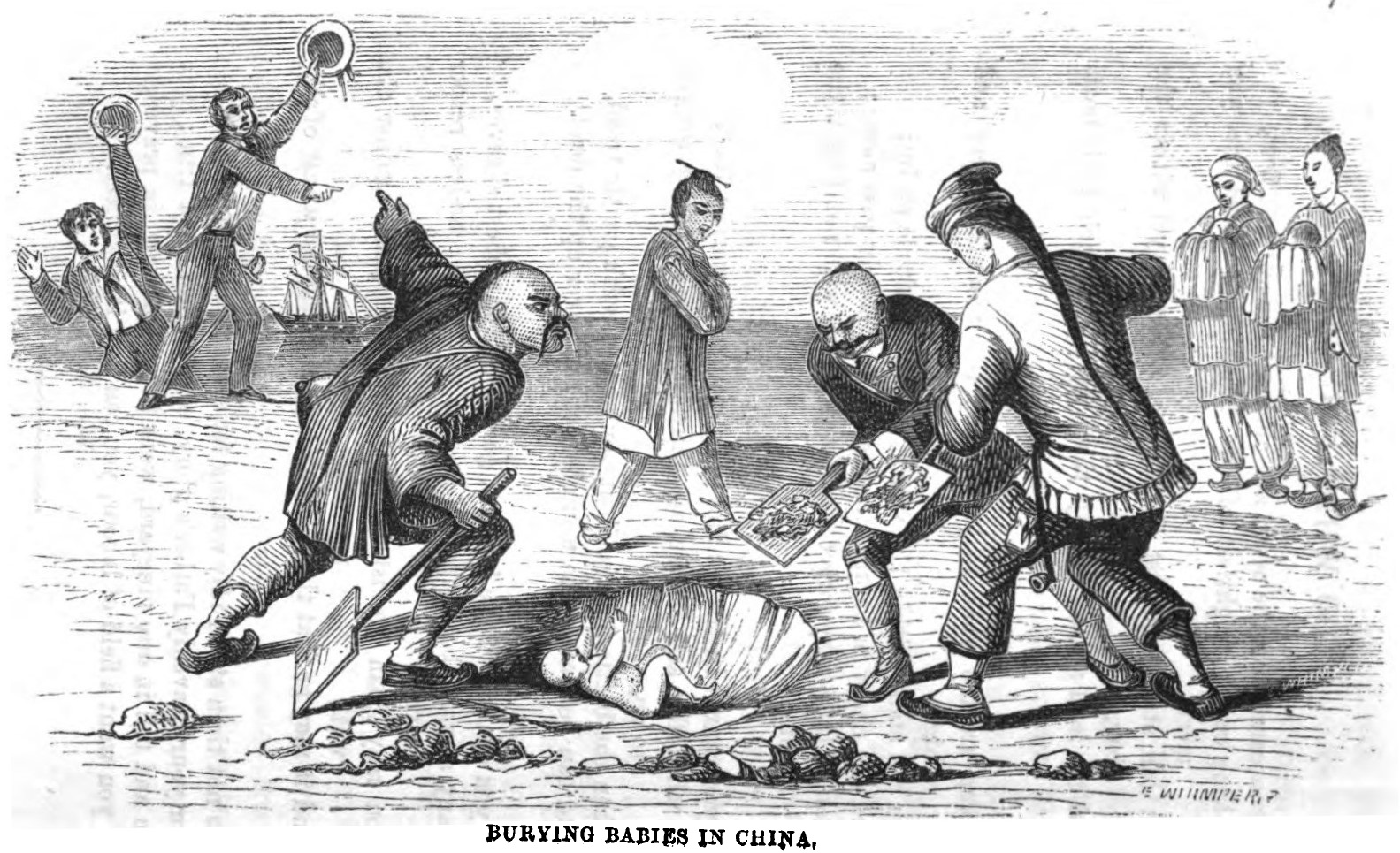

China

As of the

3rd century BC

In the Mediterranean Basin, the first few decades of this century were characterized by a balance of power between the Greek Hellenistic kingdoms in the east, and the great mercantile power of Carthage in the west. This balance was shattered ...

, short of execution, the harshest penalties were imposed on practitioners of infanticide by the legal codes of the

Qin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ; zh, c=秦朝, p=Qín cháo, w=), or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization ( zh, c=, p=, w=Ch'in ch'ao), was the first dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its heartland in Qin state (modern Gansu and Shaanxi), ...

and

Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

of ancient China.

China's society practiced sex selective infanticide. Philosopher

Han Fei Tzu, a member of the ruling aristocracy of the , who developed a school of law, wrote: "As to children, a father and mother when they produce a boy congratulate one another, but when they produce a girl they put it to death." Among the

Hakka people

The Hakka (), sometimes also referred to as Hakka Han, or Hakka Chinese, or Hakkas are a Han Chinese subgroup whose ancestral homes are chiefly in the Hakka-speaking provincial areas of Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Sichuan, Hunan, Zhej ...

, and in

Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked province in the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the C ...

,

Anhui

Anhui , (; formerly romanized as Anhwei) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the East China region. Its provincial capital and largest city is Hefei. The province is located across the basins of the Yangtze River ...

,

Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of the ...

,

Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north int ...

and

Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its cap ...

a method of killing the baby was to put her into a bucket of cold water, which was called "baby water".

Infanticide was reported as early as the , and, by the time of the

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

(), it was widespread in some provinces. Belief in transmigration allowed poor residents of the country to kill their newborn children if they felt unable to care for them, hoping that they would be reborn in better circumstances. Furthermore, some Chinese did not consider newborn children fully "human" and saw "life" beginning at some point after the sixth month after birth.

The Venetian explorer

Marco Polo claimed to have seen newborns exposed in

Manzi. Contemporary writers from the Song dynasty note that, in

Hubei

Hubei (; ; alternately Hupeh) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, and is part of the Central China region. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Dongting Lake. The ...

and

Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its cap ...

provinces, residents would only keep three sons and two daughters (among poor farmers, two sons, and one daughter), and kill all babies beyond that number at birth. Initially the sex of the child was only one factor to consider. By the time of the Ming Dynasty, however (1368–1644), male infanticide was becoming increasingly uncommon. The prevalence of female infanticide remained high much longer. The magnitude of this practice is subject to some dispute; however, one commonly quoted estimate is that, by late

Qing, between one fifth and one-quarter of all newborn girls, across the entire social spectrum, were victims of infanticide. If one includes excess mortality among female children under 10 (ascribed to gender-differential neglect), the share of victims rises to one third.

Scottish physician

John Dudgeon

John Dudgeon (1837 – 1901) was a Scottish physician who spent nearly 40 years in China as a doctor, surgeon, translator, and medical missionary.

Dudgeon attended the University of Edinburgh and the University of Glasgow, in the latter of ...

, who worked in

Peking

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

, China, during the early 20th century said that, "Infanticide does not prevail to the extent so generally believed among us, and in the north, it does not exist at all."

Gender-selected abortion or sex identification (without medical uses), abandonment, and infanticide are illegal in present-day Mainland China. Nevertheless, the

US State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

, and the

human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

organization

Amnesty International have all declared that Mainland China's family planning programs, called the

one child policy

The term one-child policy () refers to a population planning initiative in China implemented between 1980 and 2015 to curb the country's population growth by restricting many families to a single child. That initiative was part of a much bro ...

(which has since changed to a

two-child policy), contribute to infanticide. The sex gap between males and females aged 0–19 years old was estimated to be 25 million in 2010 by the

United Nations Population Fund

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), formerly the United Nations Fund for Population Activities, is a UN agency aimed at improving reproductive and maternal health worldwide. Its work includes developing national healthcare strategies a ...

.

[Christophe Z Guilmoto]

Sex imbalances at birth Trends, consequences and policy implications

United Nations Population Fund, Hanoi (October 2011) But in some cases, in order to avoid Mainland China's family planning programs, parents will not report to government when a child is born (in most cases a girl), so she or he will not have an identity in the government and they can keep on giving birth until they are satisfied, without fines or punishment. In 2017, the government announced that all children without an identity can now have an identity legally, known as

family register

Civil registration is the system by which a government records the vital events (births, marriages, and deaths) of its citizens and residents. The resulting repository or database has different names in different countries and even in differe ...

.

Japan

Since feudal Edo era

Japan the common slang for infanticide was ''mabiki'' (間引き), which means to pull plants from an overcrowded garden. A typical method in Japan was smothering the baby's mouth and nose with wet paper. It became common as a method of population control. Farmers would often kill their second or third sons. Daughters were usually spared, as they could be married off, sold off as servants or prostitutes, or sent off to become

geisha

{{Culture of Japan, Traditions, Geisha

{{nihongo, Geisha, 芸者 ({{IPAc-en, ˈ, ɡ, eɪ, ʃ, ə; {{IPA-ja, ɡeːɕa, lang), also known as {{nihongo, , 芸子, geiko (in Kyoto and Kanazawa) or {{nihongo, , 芸妓, geigi, are a class of female J ...

s. ''Mabiki'' persisted in the 19th century and early 20th century. To bear twins was perceived as barbarous and unlucky and efforts were made to hide or kill one or both twins.

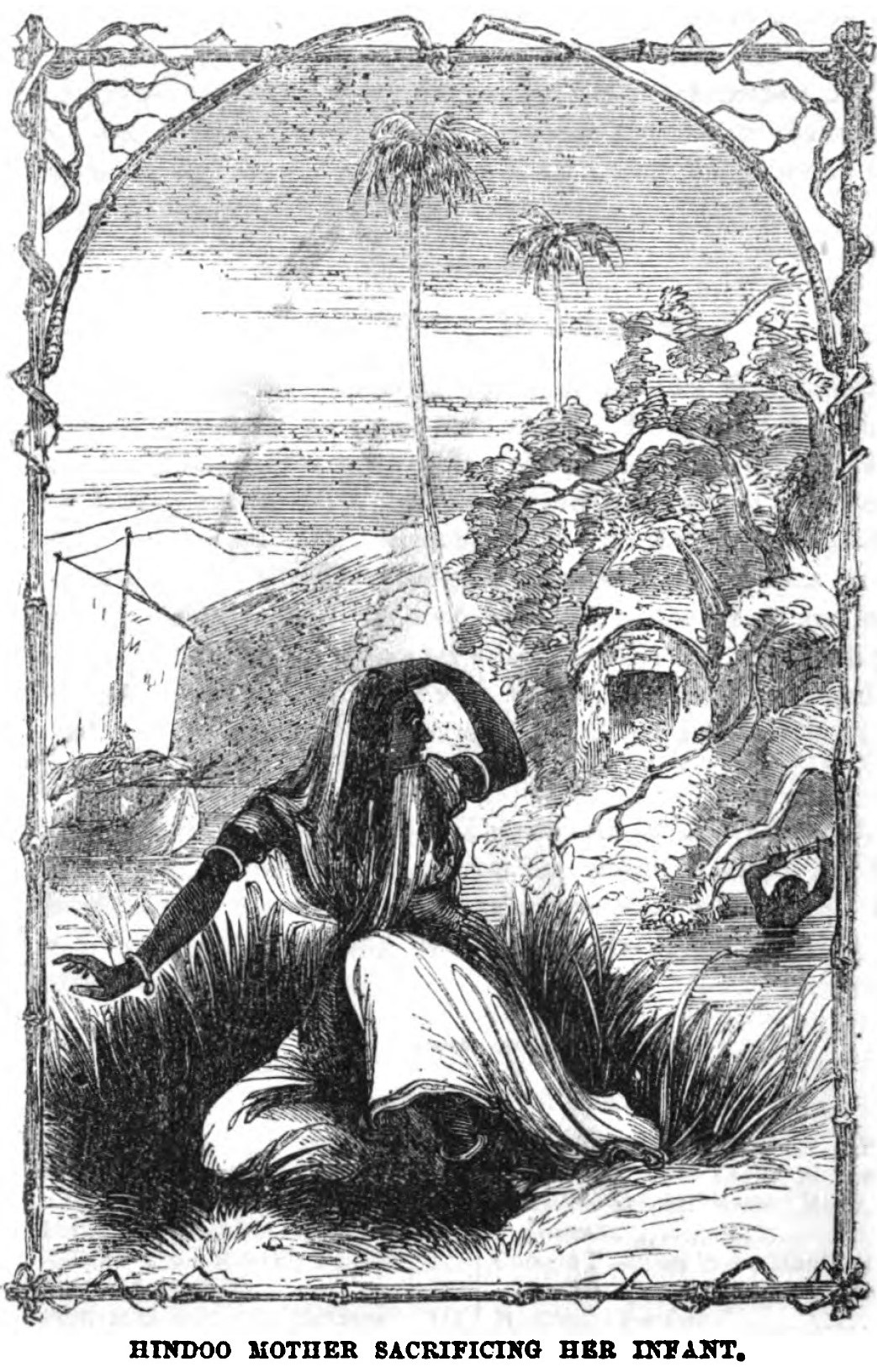

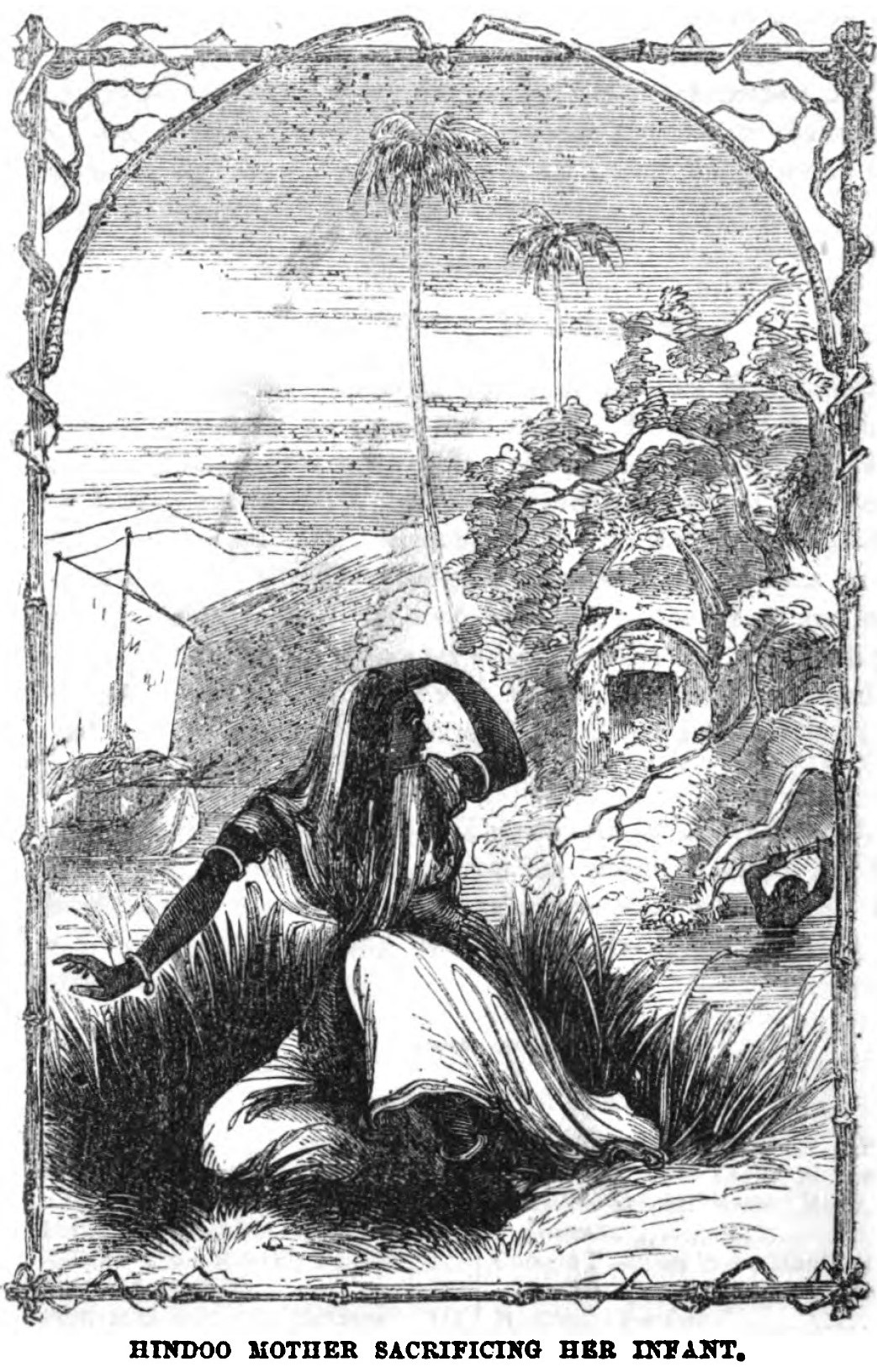

India

Female infanticide

Female infanticide is the deliberate killing of newborn female children. In countries with a history of female infanticide, the modern practice of gender-selective abortion is often discussed as a closely related issue. Female infanticide is a m ...

of newborn girls was systematic in feudatory

Rajputs

Rajput (from Sanskrit ''raja-putra'' 'son of a king') is a large multi-component cluster of castes, kin bodies, and local groups, sharing social status and ideology of genealogical descent originating from the Indian subcontinent. The term Ra ...

in

South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth descr ...

for

illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as '' ...

female children during the Middle Ages. According to

Firishta

Firishta or Ferešte ( fa, ), full name Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah Astarabadi ( fa, مُحَمَّد قاسِم هِندو شاہ), was a Persian historian, who later settled in India and served the Deccan Sultans as their court historian. He was ...

, as soon as the illegitimate female child was born she was held "in one hand, and a knife in the other, that any person who wanted a wife might take her now, otherwise she was immediately put to death". The practice of female infanticide was also common among the Kutch, Kehtri, Nagar, Bengal, Miazed, Kalowries and

Sindh communities.

It was not uncommon that parents threw a child to the

sharks

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachimorp ...

in the

Ganges River as a sacrificial offering. The

East India Company administration were unable to outlaw the custom until the beginning of the 19th century.

According to social activists, female infanticide has remained a problem in India into the 21st century, with both

NGO

A non-governmental organization (NGO) or non-governmental organisation (see spelling differences) is an organization that generally is formed independent from government. They are typically nonprofit entities, and many of them are active in h ...

s and the government conducting awareness campaigns to combat it.

Africa

In some

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

n societies some neonates were killed because of beliefs in evil omens or because they were considered unlucky. Twins were usually put to death in Arebo; as well as by the

Nama people of

South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

; in the

Lake Victoria Nyanza region; by the

Tswana

Tswana may refer to:

* Tswana people, the Bantu speaking people in Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and other Southern Africa regions

* Tswana language, the language spoken by the (Ba)Tswana people

* Bophuthatswana, the former ba ...

in

Portuguese East Africa

Portuguese Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique) or Portuguese East Africa (''África Oriental Portuguesa'') were the common terms by which Mozambique was designated during the period in which it was a Portuguese colony. Portuguese Mozambique originally ...

; in some parts of

Igboland,

Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

twins were sometimes abandoned in a forest at birth (as depicted in ''

Things Fall Apart

''Things Fall Apart'' is the debut novel by Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, first published in 1958. It depicts pre-colonial life in the southeastern part of Nigeria and the invasion by Europeans during the late 19th century. It is seen as the ...

''), oftentimes one twin was killed or hidden by midwives of wealthier mothers; and by the

!Kung people of the

Kalahari Desert

The Kalahari Desert is a large semi-arid sandy savanna in Southern Africa extending for , covering much of Botswana, and parts of Namibia and South Africa.

It is not to be confused with the Angolan, Namibian, and South African Namib coastal d ...

.

The

Kikuyu Kikuyu or Gikuyu (Gĩkũyũ) mostly refers to an ethnic group in Kenya or its associated language.

It may also refer to:

* Kikuyu people, a majority ethnic group in Kenya

*Kikuyu language, the language of Kikuyu people

*Kikuyu, Kenya, a town in Cent ...

,

Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

...

's most populous ethnic group, practiced ritual killing of twins.

Infanticide is rooted in the old traditions and beliefs prevailing all over the country. A survey conducted by

Disability Rights International

Disability Rights International (DRI), formerly Mental Disability Rights International, is a Washington, DC based human rights advocacy organization dedicated to promoting the human rights and full participation in society of persons with disabilit ...

found that 45% of women interviewed by them in Kenya were pressured to kill their children born with disabilities. The pressure is much higher in the rural areas, with every two mothers being forced out of three.

Australia

Literature suggests infanticide may have occurred reasonably commonly among Indigenous Australians, in all areas of Australia prior to European settlement. Infanticide may have continued to occur quite often up until the 1960s. An 1866 issue of ''The Australian News for Home Readers'' informed readers that "the crime of infanticide is so prevalent amongst the natives that it is rare to see an infant".

Author

Susanna de Vries

Susanna de Vries AM (born 6 October 1936) is an Australian historian, writer, and former academic. She has published more than twenty books, making her one of Queensland's most published authors. The majority of these detail the bravery and h ...

in 2007 told a newspaper that her accounts of Aboriginal violence, including infanticide, were censored by publishers in the 1980s and 1990s. She told reporters that the censorship "stemmed from guilt over the stolen children question".

Keith Windschuttle

Keith Windschuttle (born 1942) is an Australian historian and former board member of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

He was editor of '' Quadrant'' from 2007 to 2015 when he became chair of the board and editor-in-chief. He was the pub ...

weighed in on the conversation, saying this type of censorship started in the 1970s.

In the same article

Louis Nowra

Mark Doyle, better known by his stage name Louis Nowra, (born 12 December 1950) is an Australian writer, playwright, screenwriter and librettist.

He is best known as one of Australia's leading playwrights. His works have been performed by all o ...

suggested that infanticide in customary Aboriginal law may have been because it was difficult to keep an abundant number of Aboriginal children alive; there were life-and-death decisions modern-day Australians no longer have to face.

South Australia and Victoria

According to

William D. Rubinstein

William D. Rubinstein (born 12 August 1946) is a historian and author. His best-known work, ''Men of Property: The Very Wealthy in Britain Since the Industrial Revolution'', charts the rise of the ' super rich', a class he sees as expanding ex ...

, "Nineteenth-century European observers of

Aboriginal life in South Australia and

Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

reported that about 30% of Aboriginal infants were killed at birth."

James Dawson wrote a passage about infanticide among Indigenous people in the western district of Victoria, which stated that "Twins are as common among them as among Europeans; but as food is occasionally very scarce, and a large family troublesome to move about, it is lawful and customary to destroy the weakest twin child, irrespective of sex.

It is usual also to destroy those which are malformed."

Reprinted in

He also wrote "When a woman has children too rapidly for the convenience and necessities of the parents, she makes up her mind to let one be killed, and consults with her husband which it is to be. As the strength of a tribe depends more on males than females, the girls are generally sacrificed.

The child is put to death and buried, or burned without ceremony; not, however, by its father or mother, but by relatives. No one wears mourning for it.

Sickly children are never killed on account of their bad health, and are allowed to die naturally."

Western Australia

In 1937, a Christian reverend in the

Kimberley offered a "baby bonus" to Aboriginal families as a deterrent against infanticide and to increase the birthrate of the local Indigenous population.

Australian Capital Territory

A

Canberran journalist in 1927 wrote of the "cheapness of life" to the Aboriginal people local to the Canberra area 100 years before. "If drought or bush fires had devastated the country and curtailed food supplies, babies got a short shift. Ailing babies, too would not be kept", he wrote.

New South Wales

A bishop wrote in 1928 that it was common for Aboriginal Australians to restrict the size of their tribal groups, including by infanticide, so that the food resources of the tribal area may be sufficient for them.

Northern Territory

Annette Hamilton, a professor of anthropology at

Macquarie University who carried out research in the Aboriginal community of Maningrida in Arnhem Land during the 1960s wrote that prior to that time part-European babies born to Aboriginal mothers had not been allowed to live, and that 'mixed-unions are frowned on by men and women alike as a matter of principle'.

New Zealand

North America

Inuit

There is no agreement about the actual estimates of the frequency of newborn female infanticide in the

Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories ...

population.

Carmel Schrire

Carmel Schrire (born May 15, 1941)John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, ''Reports of the President and the Treasurer'' (John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, 1989), p. 83. is a professor of anthropology at Rutgers University whose rese ...

mentions diverse studies ranging from 15 to 50% to 80%.

Polar Inuit (

Inughuit

The Inughuit (also spelled Inuhuit), or the Smith Sound Inuit, historically Arctic Highlanders, are Greenlandic Inuit. Formerly known as "Polar Eskimos", they are the northernmost group of Inuit and the northernmost people in North America, livin ...

) killed the child by throwing him or her into the sea. There is even a legend in

Inuit mythology

Inuit religion is the shared spiritual beliefs and practices of the Inuit, an Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous people from Alaska, northern Canada, parts of Siberia and Greenland. Their religion shares many similarities with some Al ...

, "The Unwanted Child", where a mother throws her child into the

fjord

In physical geography, a fjord or fiord () is a long, narrow inlet with steep sides or cliffs, created by a glacier. Fjords exist on the coasts of Alaska, Antarctica, British Columbia, Chile, Denmark, Förden and East Jutland Fjorde, Germany, ...

.

The

Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

and the Mahlemuit tribes of

Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

exposed the female newborns by first stuffing their mouths with grass before leaving them to die. In

Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenland), Finland, Iceland, N ...

Canada the Inuit exposed their babies on the ice and left them to die.

Female Inuit infanticide disappeared in the 1930s and 1940s after contact with the Western cultures from the South.

Canada

The ''

Handbook of North American Indians

The ''Handbook of North American Indians'' is a series of edited scholarly and reference volumes in Native American studies, published by the Smithsonian Institution beginning in 1978. Planning for the handbook series began in the late 1960s and ...

'' reports infanticide among the

Dene

The Dene people () are an indigenous group of First Nations who inhabit the northern boreal and Arctic regions of Canada. The Dene speak Northern Athabaskan languages. ''Dene'' is the common Athabaskan word for "people". The term "Dene" ha ...

Natives and those of the

Mackenzie Mountains

The Mackenzie Mountains are a Canadian mountain range forming part of the Yukon- Northwest Territories boundary between the Liard and Peel rivers. The range is named in honour of Canada's second prime minister, Alexander Mackenzie. Nahanni Na ...

.

Native Americans

In the Eastern

Shoshone there was a scarcity of Indian women as a result of female infanticide. For the

Maidu

The Maidu are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of northern California. They reside in the central Sierra Nevada (U.S.), Sierra Nevada, in the watershed area of the Feather River, Feather and American River, American ...

Native Americans twins were so dangerous that they not only killed them, but the mother as well. In the region known today as southern

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, the Mariame Indians practiced infanticide of females on a large scale. Wives had to be obtained from neighboring groups.

Mexico

Bernal Díaz recounted that, after landing on the

Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

coast, they came across a temple dedicated to

Tezcatlipoca

Tezcatlipoca (; nci, Tēzcatl ihpōca ) was a central deity in Aztec religion, and his main festival was the Toxcatl ceremony celebrated in the month of May. One of the four sons of Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, the God of providence, he is a ...

. "That day they had sacrificed two boys, cutting open their chests and offering their blood and hearts to that accursed idol". In ''

The Conquest of New Spain'' Díaz describes more child sacrifices in the towns before the Spaniards reached the large

Aztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl ...

city

Tenochtitlan

, ; es, Tenochtitlan also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, ; es, México-Tenochtitlan was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear. The date 13 March 1325 was ...

.

South America

Although academic data of infanticides among the indigenous people in

South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

is not as abundant as that of North America, the estimates seem to be similar.

Brazil

The

Tapirapé indigenous people of

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

allowed no more than three children per woman, and no more than two of the same sex. If the rule was broken infanticide was practiced. The

Bororo

The Bororo are indigenous people of Brazil, living in the state of Mato Grosso. They also extended into Bolivia and the Brazilian state of Goiás. The Western Bororo live around the Jauru and Cabaçal rivers. The Eastern Bororo ( Orarimogodoge) ...

killed all the newborns that did not appear healthy enough. Infanticide is also documented in the case of the

Korubo people

The Korubo or Korubu, also known as the Dslala, are an indigenous people of Brazil living in the lower Vale do Javari in the western Amazon Basin. The group calls themselves 'Dslala', and in Portuguese they are referred to as ''caceteiros'' (cl ...

in the

Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technolog ...

.

The

Yanomami

The Yanomami, also spelled Yąnomamö or Yanomama, are a group of approximately 35,000 indigenous people who live in some 200–250 villages in the Amazon rainforest on the border between Venezuela and Brazil.

Etymology

The ethnonym ''Yanomami' ...

men killed children while raiding enemy villages.

, a Brazilian woman kidnapped by Yanomami warriors in the 1930s, witnessed a Karawetari raid on her tribe:

Peru, Paraguay and Bolivia

While ''

qhapaq hucha

''Capacocha'' or ''Qhapaq hucha'Of Summits and Sacrifice: An Ethnohistoric Study of Inka Religious Practices'', University of Texas Press, 2009 ( qu, qhapaq noble, solemn, principal, mighty, royal, crime, sin, guilt Hispanicized spellings , , ...

'' was practiced in the

Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

vian large cities, child sacrifice in the pre-Columbian tribes of the region is less documented. However, even today studies on the

Aymara

Aymara may refer to:

Languages and people

* Aymaran languages, the second most widespread Andean language

** Aymara language, the main language within that family

** Central Aymara, the other surviving branch of the Aymara(n) family, which today ...

Indians reveal high incidences of mortality among the newborn, especially female deaths, suggesting infanticide. The

Abipones, a small tribe of

Guaycuruan