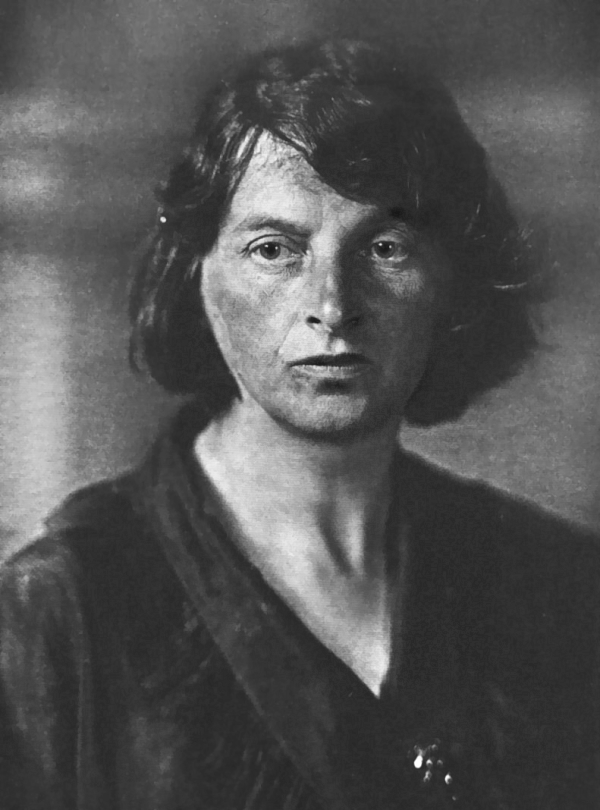

Inessa Armand on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Inessa Fyodorovna Armand (born Elisabeth-Inès Stéphane d'Herbenville; 8 May 1874 – 24 September 1920) was a French-Russian

Armand was born in

Armand was born in

In 1902, she left her husband, with whom she had an

In 1902, she left her husband, with whom she had an  Armand returned to Russia in July 1912. This was a risky mission. Lenin needed her to pass on the resolution of the Prague Conference, to help organise the Bolshevik campaign to get its supporters elected to the

Armand returned to Russia in July 1912. This was a risky mission. Lenin needed her to pass on the resolution of the Prague Conference, to help organise the Bolshevik campaign to get its supporters elected to the

On 2 March 1917 Tsar

On 2 March 1917 Tsar

Bob Gould remarked that, "It is fairly clear from Armand’s last diary entries, and from Lenin’s utter devastation at her death, that they may both have had some vague perspective of resuming the physical side of their relationship at some more favourable time in the future, as people often do in such circumstances. Another feature of Inessa Armand was that, despite her intense emotional involvement with Lenin, she was capable of disagreeing with him politically on points of principle. She was a vigorous participant in the

Bob Gould remarked that, "It is fairly clear from Armand’s last diary entries, and from Lenin’s utter devastation at her death, that they may both have had some vague perspective of resuming the physical side of their relationship at some more favourable time in the future, as people often do in such circumstances. Another feature of Inessa Armand was that, despite her intense emotional involvement with Lenin, she was capable of disagreeing with him politically on points of principle. She was a vigorous participant in the

In JSTOR

"Women Fighters in the Days of the Great October Revolution"

* Brian Pearce

"Review: RC Elwood, Inessa Armand"

{{DEFAULTSORT:Armand, Inessa 1874 births 1920 deaths Old Bolsheviks Deaths from cholera French emigrants to Russia French feminists French communists French Marxists French people of English descent Infectious disease deaths in the Soviet Union Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis Politicians from Paris Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Vladimir Lenin Russian socialist feminists French expatriates in the Soviet Union

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

politician, member of the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

and a feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male poi ...

who spent most of her life in Russia. Armand, being an important figure in pre-Revolution Russian communist movement and early days of the communist era, had been almost forgotten for a long time (due to deliberate Stalinist

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theor ...

censorship, partly in consideration of her relationship with Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

) until the partial opening of Soviet archives during the 1990s (despite this, many valuable sources regarding her life still remain inaccessible in Russian archives). Historian Michael Pearson wrote about her: "She was to help him (Lenin) recover his position and hone his Bolsheviks into a force that would acquire more power than the tsar, and would herself by 1919 become the most powerful woman in Moscow."

Early life and marriages

Armand was born in

Armand was born in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

. Her mother, Nathalie Wild, was a comedienne of half-French and half-English descent, and her father, Théodore Pécheux d'Herbenville, was a French opera-singer. Her father died when she was five and she was brought up by her aunt and grandmother living in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

, both teachers.

At the age of nineteen she married Alexander Armand, the son of a wealthy Russian textile manufacturer. The marriage produced four children. Inessa and her husband opened a school for peasant children outside of Moscow. She also joined a charitable group dedicated to helping the city's destitute women.

Life

In 1902, she left her husband, with whom she had an

In 1902, she left her husband, with whom she had an open marriage

Open marriage is a form of non-monogamy in which the partners of a dyadic marriage agree that each may engage in extramarital sexual relationships, without this being regarded by them as infidelity, and consider or establish an open relati ...

, to marry his younger brother Vladimir, who shared her radical political views, and bore him her fifth child, Andrei.

In 1903, she joined the illegal Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

. Armand distributed illegal propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

; after her arrest in June 1907 she was sentenced to two years' internal exile in Mezen in Northern Russia.

In November 1908 Armand managed to escape from Mezen and eventually left Russia to settle in Paris, where she met Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

and other Bolsheviks living in foreign exile. In 1911 Armand became secretary for the Committee of Foreign Organisations established to coordinate all Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

groups in Western Europe.

Armand returned to Russia in July 1912. This was a risky mission. Lenin needed her to pass on the resolution of the Prague Conference, to help organise the Bolshevik campaign to get its supporters elected to the

Armand returned to Russia in July 1912. This was a risky mission. Lenin needed her to pass on the resolution of the Prague Conference, to help organise the Bolshevik campaign to get its supporters elected to the Duma

A duma (russian: дума) is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were for ...

, and find out what was going on in Pravda. Helen Rappaport notes that Lenin knew her entry into Russia would invite immediate arrest, yet he made light of it, his concerns for party works overcoming his personal feelings for her. Two months later she was arrested and imprisoned, only to be released against bail in March 1913, thanks to Alexander's generous support. Once again illegally leaving Russia, she went to live with Vladimir Lenin and Nadezhda Krupskaya

Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya ( rus, links=no, Надежда Константиновна Крупская, p=nɐˈdʲeʐdə kənstɐnˈtʲinəvnə ˈkrupskəjə; 27 February 1939) was a Russian revolutionary and the wife of Vladimir Lenin ...

in Galicia. She also began work editing '' Rabotnitsa''. Krupskaya, with admiration, noted that exhausted as Armand was, she threw herself immediately into the party works. Lenin wrote to her and trusted her more than anyone else in his circles. The Okhrana

The Department for Protecting the Public Security and Order (russian: Отделение по охранению общественной безопасности и порядка), usually called Guard Department ( rus, Охранное отд ...

considered Armand to be the right hand of Lenin.

According to author Ralph Carter Elwood, "Even more than Trotsky during the Iskra period, she became Lenin’s ‘cudgel’ — someone to beat wavering Bolsheviks back into line, to convey uncompromising messages to his political opponents, to carry out uncomfortable missions which Lenin himself preferred to avoid".

Armand was upset that many socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

in Europe chose not to fight against the war effort during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fight ...

. She joined Lenin in helping to distribute propaganda that urged Allied troops to turn their rifles against their officers and to start a socialist revolution.

Lenin appointed her as the Bolshevik representative to the International Socialist Bureau conference in Brussels in July 1914. Bertram Wolfe remarked, "He was sending her to meet and do battle with such large figures as Kautsky, Vandervelde, Huysmans, Luxemburg, Plekhanov, Trotsky and Martov. He counted on her mastery of all the languages of the International, her literal devotion to him and his views, her steadfastness under fire". He wrote to her:

I am convinced that you are one of those who develops, grows stronger, becomes more energetic and bolder when alone in a responsible post … I stubbornly disbelieve the pessimists who say that you — are hardly — nonsense and again nonsense.In March 1915 Armand went to

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

where she organised the anti-war International Conference of Socialist Women.

Russian Revolution

On 2 March 1917 Tsar

On 2 March 1917 Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in Reforms of Russian orthography, pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of ...

abdicated, leaving the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

in control of the country, which declared the Russian Republic

The Russian Republic,. referred to as the Russian Democratic Federal Republic. in the 1918 Constitution, was a short-lived state which controlled, ''de jure'', the territory of the former Russian Empire after its proclamation by the Russi ...

. The Bolsheviks in exile became desperate to return to Russia to help shape the future of the country. The German Foreign Ministry, which hoped that Bolshevik influence in Russia would help bring the war on the Eastern Front to an end, provided a special train for Armand, Vladimir Lenin and 26 other revolutionaries to travel to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

.

She did not participate in most of the revolutionary events, choosing to take care of her ill son Andrei instead. It is still unclear why she chose to be inactive during this crucial period of seizing power, although she had interrupted her revolutionary activities for the sake of her children in 1905, 1908 and 1913. On 19 April, she did attend a Moscow Oblast Conference, in which she made forceful speeches on the necessity of the election of officers and the fraternization of combatant forces, as well as on the opportunism of the Second International's leaders.

After the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

, Armand headed the Moscow Economic Council and served as an executive member of the Moscow Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

. She became a staunch critic of the Soviet government's decision to sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. On her return to Petrograd, she became the first director of Zhenotdel, an organisation that fought for female equality in the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Enge ...

and the Soviet trade unions

Trade unions in the Soviet Union, headed by the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions (VTsSPS or ACCTU in English), had a complex relationship with industrial management, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the Soviet government, giv ...

(Zhenotdel operated until 1930), with powers to make legislative decisions. She drove through reforms to allow women rights to divorce, abort, participate in government affairs and create the facilities like mass canteens and mother centers. In 1918, with Sverdlov's assistance against opposition from Zinoviev and Radek, she succeeded in getting a national congress of working women held, with Lenin as a speaker. According to Elwood, the reason the party leadership agreed to back up Armand’s agitation for communal facilities was that the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policie ...

required enlisting women into factory work and auxiliary tasks in the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

, which created the need to release women from traditional duties. Armand also chaired the First International Conference of Communist Women in 1920. The spring of 1920 saw the appearance, again on Armand’s initiative, of the journal '' Kommunistka'', which dealt with "the broader aspects of female emancipation and the need to alter the relationship between the sexes if lasting change was to be effected".

Death

But the fifth number of this journal carried its founder’s obituary. Realizing that she was exhausted from overload of work, Lenin had urged Armand to go to theCaucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historicall ...

for a holiday, without knowing that the area was infested by epidemic and had not been pacified by the Red Army. She and other patients had to be evacuated from the region. On the evening of 21 September 1920, she ventured out to meet the Nal'chik Executive Committee, perhaps to get accommodation for her group, and contracted cholera. She died in the morning hours of 24 September, aged 46. A state funeral was organized, with a mass singing of the Internationale. She was buried in Mass Grave No. 5 of the Kremlin Wall Necropolis

The Kremlin Wall Necropolis was the national cemetery for the Soviet Union. Burials in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Moscow began in November 1917, when 240 pro-Bolshevik individuals who died during the Moscow Bolshevik Uprising were buried in m ...

in Red Square, Moscow, being the first woman to receive this honour.

In the first edition of the ''Great Soviet Encyclopedia

The ''Great Soviet Encyclopedia'' (GSE; ) is one of the largest Russian-language encyclopedias, published in the Soviet Union from 1926 to 1990. After 2002, the encyclopedia's data was partially included into the later ''Bolshaya rossiyskaya en ...

'', published in 1926, she was commemorated as a "senior and dedicated Bolshevik" and as "a close friend and aide of Lenin", but by the 1930s her work had been forgotten. The Zhenotdel was abolished in 1930.

In literature and film

Inessa Armand is assumed to be the model for the fictional heroine of the novel ''A Great Love'', written in 1923 byAlexandra Kollontai

Alexandra Mikhailovna Kollontai (russian: Алекса́ндра Миха́йловна Коллонта́й, née Domontovich, Домонто́вич; – 9 March 1952) was a Russian revolutionary, politician, diplomat and Marxist the ...

, who knew both Lenin and Armand. The heroine is in love with a revolutionary leader, assumed to be based on Lenin who "takes her devotion to him for granted and returns it with resentment and suspicion."

Armand has been portrayed in the films '' Lenin in Paris'' (1981, played by Claude Jade

Claude Marcelle Jorré, better known as Claude Jade (; 8 October 1948 – 1 December 2006), was a French actress. She starred as Christine in François Truffaut's three films ''Stolen Kisses'' (1968), '' Bed and Board'' (1970) and '' Love on th ...

), '' Lenin...The Train'' (1988, played by Dominique Sanda

Dominique Marie-Françoise Renée Varaigne (born 11 March 1951), professionally known as Dominique Sanda, is a French actress and former fashion model.

Life and career

Sanda was born in Paris, to Lucienne (née Pichon) and Gérard Varaigne. She ...

) and '' All My Lenins'' (1997, played by Janne Sevchenko). She was also portrayed as the heroine in the fictionalised account of Lenin's Russian return: ''Seven Days to Petrograd'' (1988 by Tom Hyman, Penguin Books).

Romantic relationship with Lenin

Armand and Lenin were very close friends from 1911 to 1912 or 1914–how sexual it was remains a debated point among scholars. Krupskaya wrote about her:We were terribly glad... at her arrival. . . . In the autumn (of 1913) all of us became very close to Inessa. In her there was much joy of life and ardor. We had known Inessa in Paris, but there was a large colony there. In Krakow lived a small closely knit circle of comrades. Inessa rented a room in the same family with which Kamenev lived. My mother became closely attached to Inessa. Inessa often went to talk with her, sit with her, have a smoke with her. It became cosier and gayer when Inessa came. Our entire life was filled with party concerns and affairs, more like a student commune than like family life, and we were glad to have Inessa... Something warm radiated from her talk.In ''In Memory of Inessa Armand'', Krupskaya further suggested that Inessa and Lenin were bonded together by their common favourite fictional work '' What Is to Be Done?'':

Inessa was moved to socialism by the image of woman’s rights and freedom in What Is To Be Done? Like the heroine, she broke her ties with one man to live with another, concerned herself with good deeds to redeem the poor female and the prostitute, tried to solve the problems of woman’s too servile place in society. Indeed, whole generations of Russian radicals were influenced by Chernyshevsky’s many-sided utopian novel and were moved to imitate its “uncommon men and women”. Just as Marx could be the spiritual ancestor of people as various as Bernstein, Kautsky, Bebel, and Luxemburg, so Chernyshevsky was a formative influence for the two men who in their persons incarnated the two opposing poles of socialism in 1917: Tsereteli and Lenin. If Inessa found in the novel her image of woman’s rights and freedom in love, and Lenin the prototypes of his vanguard and his leadership, Tsereteli found there his ideal of service to the people.Angelica Balabanoff recalled about the relationship between Armand and Lenin:

Lenin loved Inessa. There was nothing immoral in it, since Lenin told Krupskaya everything gain the same code He deeply loved music, and this Krupskaya could not give him. Inessa played beautifully — his beloved Beethoven and other pieces. He sent Inessa to the Youth Conference of the Zimmerwald Group — a little old, but she had a credential from the Bolsheviks and we had to accept it. He did not dare to come himself, sat downstairs in a little adjacent cafe drinking tea, getting reports from her, giving her instructions. I went down for tea and found him there. Did you come na chai, I asked, or na rezoliutsii? (for tea, or for the resolution?) He laughed knowingly, but did not answer. nessa fought hard, but the resolution Lenin prepared for her was defeated 13–3.When Inessa died, he begged me to speak at her funeral. He was utterly broken by her death.

Bob Gould remarked that, "It is fairly clear from Armand’s last diary entries, and from Lenin’s utter devastation at her death, that they may both have had some vague perspective of resuming the physical side of their relationship at some more favourable time in the future, as people often do in such circumstances. Another feature of Inessa Armand was that, despite her intense emotional involvement with Lenin, she was capable of disagreeing with him politically on points of principle. She was a vigorous participant in the

Bob Gould remarked that, "It is fairly clear from Armand’s last diary entries, and from Lenin’s utter devastation at her death, that they may both have had some vague perspective of resuming the physical side of their relationship at some more favourable time in the future, as people often do in such circumstances. Another feature of Inessa Armand was that, despite her intense emotional involvement with Lenin, she was capable of disagreeing with him politically on points of principle. She was a vigorous participant in the Workers' Opposition

The Workers' Opposition (russian: Рабочая оппозиция) was a faction of the Russian Communist Party that emerged in 1920 as a response to the perceived over-bureaucratisation that was occurring in Soviet Russia. They advocated t ...

, despite the fact that this involved a profound political collision with Lenin".

According to Elwood, since Bertram Wolfe proved the existence of the romantic relationship in 1963, Western scholarship has focused so much on it that her achievements as a revolutionist and a feminist are usually obscured. Elwood tried to call attention to her work first as an underground propagandist, then as a Bolshevik organizer in emigration, and finally as a defender of women's rights in the workplace and in society.

See also

*History of feminism

The history of feminism comprises the narratives (chronological or thematic) of the movements and ideologies which have aimed at equal rights for women. While feminists around the world have differed in causes, goals, and intentions depending ...

* Kommunistka

* Women in the Russian Revolution

* Zhenotdel

References

Cited sources

*Further reading

*Elwood, Ralph Carter. ''Vserossiiskaya Konferentsiya Ros. Sots. -Dem. Rab. Partii 1912 Goda: All-Russian Conference of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party 1912. Together With Izveschenie O Konferentsii Organizatsii RSDRP''. Publications of the Study Group on the Russian Revolution 4. Millwood, NY: Kraus International Publications, 1982. *Elwood, Ralph Carter “Lenin's Correspondence with Inessa Armand,” ''The Slavonic and East European Review'', Vol. 65, No. 2 (Apr. 1987): 218–235. *McNeal, Robert H. ''Bride of the Revolution: Krupskaya and Lenin'', London: Victor Golancz, 1973. *Pearson, Michael. ''The Sealed Train''. New York: Putnam, 1975. * * Wolfe, Bertram D. "Lenin and Inessa Armand," ''Slavic Review,'' vol. 22, no. 1 (March 1963), pp. 96–114In JSTOR

External links

*Alexandra Kollontai

Alexandra Mikhailovna Kollontai (russian: Алекса́ндра Миха́йловна Коллонта́й, née Domontovich, Домонто́вич; – 9 March 1952) was a Russian revolutionary, politician, diplomat and Marxist the ...

"Women Fighters in the Days of the Great October Revolution"

* Brian Pearce

"Review: RC Elwood, Inessa Armand"

{{DEFAULTSORT:Armand, Inessa 1874 births 1920 deaths Old Bolsheviks Deaths from cholera French emigrants to Russia French feminists French communists French Marxists French people of English descent Infectious disease deaths in the Soviet Union Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis Politicians from Paris Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Vladimir Lenin Russian socialist feminists French expatriates in the Soviet Union