The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

before the arrival of the

European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many

Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

of the Americas were traditionally

hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fung ...

s and many, especially in the

Amazon basin

The Amazon basin is the part of South America drained by the Amazon River and its tributaries. The Amazon drainage basin covers an area of about , or about 35.5 percent of the South American continent. It is located in the countries of Boli ...

, still are, but many groups practiced

aquaculture

Aquaculture (less commonly spelled aquiculture), also known as aquafarming, is the controlled cultivation ("farming") of aquatic organisms such as fish, crustaceans, mollusks, algae and other organisms of value such as aquatic plants (e.g. lot ...

and

agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

.

While some societies depended heavily on agriculture, others practiced a mix of farming, hunting, and gathering. In some regions, the Indigenous peoples created monumental architecture, large-scale organized cities,

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s,

chiefdom

A chiefdom is a form of hierarchical political organization in non-industrial societies usually based on kinship, and in which formal leadership is monopolized by the legitimate senior members of select families or 'houses'. These elites form a ...

s,

states,

kingdoms,

republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

s,

confederacies, and

empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

s. Some had varying degrees of knowledge of engineering, architecture, mathematics, astronomy, writing, physics, medicine, planting and irrigation, geology, mining, metallurgy, sculpture, and gold smithing.

Many parts of the Americas are still populated by Indigenous peoples; some countries have sizeable populations, especially

Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

,

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

,

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

,

Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ' ...

,

Guatemala

Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico; to the northeast by Belize and the Caribbean; to the east by Hon ...

,

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

,

Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

, and the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. At least a thousand different

Indigenous languages are spoken in the Americas. Some, such as

Quechua

Quechua may refer to:

*Quechua people, several indigenous ethnic groups in South America, especially in Peru

*Quechuan languages, a Native South American language family spoken primarily in the Andes, derived from a common ancestral language

**So ...

,

Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, who historically lived in the Greate ...

,

Aymara

Aymara may refer to:

Languages and people

* Aymaran languages, the second most widespread Andean language

** Aymara language, the main language within that family

** Central Aymara, the other surviving branch of the Aymara(n) family, which today ...

,

Guaraní Guarani, Guaraní or Guarany may refer to

Ethnography

* Guaraní people, an indigenous people from South America's interior (Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Bolivia)

* Guaraní language, or Paraguayan Guarani, an official language of Paraguay

* ...

,

Mayan

Mayan most commonly refers to:

* Maya peoples, various indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica and northern Central America

* Maya civilization, pre-Columbian culture of Mesoamerica and northern Central America

* Mayan languages, language family spoken ...

, and

Nahuatl

Nahuatl (; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have small ...

, count their speakers in the millions. Many also maintain aspects of Indigenous cultural practices to varying degrees, including religion,

social organization

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and social groups.

Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership, s ...

, and

subsistence

A subsistence economy is an economy directed to basic subsistence (the provision of food, clothing, shelter) rather than to the market. Henceforth, "subsistence" is understood as supporting oneself at a minimum level. Often, the subsistence econo ...

practices. Like most cultures, over time, cultures specific to many Indigenous peoples have evolved to incorporate traditional aspects but also cater to modern needs. Some Indigenous peoples still live in relative isolation from

Western culture

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

and a few are still counted as

uncontacted peoples

Uncontacted peoples are groups of indigenous peoples living without sustained contact with neighbouring communities and the world community. Groups who decide to remain uncontacted are referred to as indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation. ...

.

Terminology

Application of the term "

Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

" originated with

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

, who, in his search for

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, thought that he had arrived in the

East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

. Eventually, those islands came to be known as the "

West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

", a name still used. This led to the blanket term "Indies" and "Indians" ( es, indios; pt, índios; french: indiens; nl, indianen) for the Indigenous inhabitants, which implied some kind of ethnic or cultural unity among the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. This unifying concept, codified in law, religion, and politics, was not originally accepted by the myriad groups of Indigenous peoples themselves, but has since been embraced or tolerated by many over the last two centuries. Even though the term "Indian" generally does not include the culturally and

linguistically

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

distinct Indigenous peoples of the Arctic regions of the Americas—such as the

Aleut

The Aleuts ( ; russian: Алеуты, Aleuty) are the indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands, which are located between the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Both the Aleut people and the islands are politically divided between the ...

s,

Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

, or

Yupik peoples

The Yupik (plural: Yupiit) (; russian: Юпикские народы) are a group of indigenous or aboriginal peoples of western, southwestern, and southcentral Alaska and the Russian Far East. They are related to the Inuit and Iñupiat. Y ...

, who entered the continent as a second, more recent wave of migration several thousand years later and have much more recent genetic and cultural commonalities with the

Aboriginal peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

of the Asiatic Arctic

Russian Far East

The Russian Far East (russian: Дальний Восток России, r=Dal'niy Vostok Rossii, p=ˈdalʲnʲɪj vɐˈstok rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a region in Northeast Asia. It is the easternmost part of Russia and the Asian continent; and is admin ...

—these groups are nonetheless considered "Indigenous peoples of the Americas".

The term ''Amerindian'', a

portmanteau

A portmanteau word, or portmanteau (, ) is a blend of words[American Anthropological Association

The American Anthropological Association (AAA) is an organization of scholars and practitioners in the field of anthropology. With 10,000 members, the association, based in Arlington, Virginia, includes archaeologists, cultural anthropologists, ...](_blank)

. However, it has been controversial since its creation. It was immediately rejected by some leading members of the Association, and, while adopted by many, it was never universally accepted.

While never popular in Indigenous communities themselves, it remains a preferred term among some anthropologists, notably in some parts of Canada and the

English-speaking Caribbean

The Commonwealth Caribbean is the region of the Caribbean with English-speaking countries and territories, which once constituted the Caribbean portion of the British Empire and are now part of the Commonwealth of Nations. The term includes ma ...

.

Indigenous peoples in Canada

In Canada, Indigenous groups comprise the First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Although ''Indian'' is a term still commonly used in legal documents, the descriptors ''Indian'' and '' Eskimo'' have fallen into disuse in Canada, and most consider th ...

is used as the collective name for

First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

,

Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

, and

Métis

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Canadian Prairies, Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United State ...

.

The term ''Aboriginal peoples'' as a

collective noun

In linguistics, a collective noun is a word referring to a collection of things taken as a whole. Most collective nouns in everyday speech are not specific to one kind of thing. For example, the collective noun "group" can be applied to people (" ...

(also describing First Nations, Inuit, and Métis) is a specific

term of art

Jargon is the specialized terminology associated with a particular field or area of activity. Jargon is normally employed in a particular communicative context and may not be well understood outside that context. The context is usually a partic ...

used in some legal documents, including the

Constitution Act, 1982

The ''Constitution Act, 1982'' (french: link=no, Loi constitutionnelle de 1982) is a part of the Constitution of Canada.Formally enacted as Schedule B of the ''Canada Act 1982'', enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Section 60 of t ...

,

though in most Indigenous circles ''Aboriginal'' has also fallen into disfavor. Over time, as societal perceptions and government-Indigenous relationships have shifted, many historical terms have changed definition or been replaced as they have fallen out of favor.

Use of the term "Indian" is frowned upon because it represents the imposition and restriction of Indigenous peoples and cultures by the Canadian Government.

The terms "Native" and "

Eskimo

Eskimo () is an exonym used to refer to two closely related Indigenous peoples: the Inuit (including the Alaska Native Iñupiat, the Greenlandic Inuit, and the Canadian Inuit) and the Yupik (or Yuit) of eastern Siberia and Alaska. A related ...

" are generally regarded as disrespectful, and so are rarely used unless specifically required.

While "Indigenous peoples" is the preferred term, many individuals or communities may choose to self-describe their identity using a different term.

The Métis people of Canada ''can'' be contrasted, for instance, to the Indigenous-European mixed race

mestizos

(; ; fem. ) is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed European and Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also refer to people who are culturally European even though thei ...

(or in Brazil) of

Hispanic America

The region known as Hispanic America (in Spanish called ''Hispanoamérica'' or ''América Hispana'') and historically as Spanish America (''América Española'') is the portion of the Americas comprising the Spanish-speaking countries of North, ...

who, with their larger population (in most Latin-American countries constituting either outright majorities, pluralities, or at the least large minorities), identify largely as a new ethnic group distinct from both Europeans and Indigenous, but still considering themselves a subset of the European-derived

Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to viceroyalties for ...

or

Brazilian peoplehood in culture and ethnicity (

cf.

The abbreviation ''cf.'' (short for the la, confer/conferatur, both meaning "compare") is used in writing to refer the reader to other material to make a comparison with the topic being discussed. Style guides recommend that ''cf.'' be used onl ...

).

Among

Spanish-speaking countries

The following is a list of countries where Spanish is an official language, plus a number of countries where Spanish or any language closely related to it, is an important or significant language.

Official or national language

Spanish is the o ...

, or ('Indigenous peoples') is a common term, though or ('native peoples') may also be heard; moreover, ('aborigine') is used in

Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

and ('original peoples') is common in

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

. In Brazil, or ('Indigenous peoples') are common of formal-sounding designations, while ('Indian') is still the more often-heard term (the noun for the South-Asian nationality being ). and is rarely used in Brazil in Indigenous-specific contexts (e.g., is usually understood as the ethnonym for

Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

). The Spanish and Portuguese equivalents to Indian, nevertheless, could be used to mean any

hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fung ...

or full-blooded Indigenous person, particularly to continents other than Europe or Africa—for example, .

Indigenous peoples of the United States are commonly known as

Native Americans, Indians, as well as

Alaska Natives

Alaska Natives (also known as Alaskan Natives, Native Alaskans, Indigenous Alaskans, Aboriginal Alaskans or First Alaskans) are the indigenous peoples of Alaska and include Iñupiat, Yupik, Aleut, Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, and a num ...

. The term "Indian" is still used in some communities and remains in use in the official names of many institutions and businesses in

Indian Country.

Native American name controversy

The various Nations, tribes, and bands of Indigenous peoples of the Americas have differing preferences in terminology for themselves.

While there are regional and generational variations in which umbrella terms are preferred for Indigenous peoples as a whole, in general, most Indigenous peoples prefer to be identified by the name of their specific Nation, tribe, or band.

Early settlers often adopted terms that some tribes used for each other, not realizing these were derogatory terms used by enemies. When discussing broader subsets of peoples, naming has often been based on shared language, region, or historical relationship. Many English

Early settlers often adopted terms that some tribes used for each other, not realizing these were derogatory terms used by enemies. When discussing broader subsets of peoples, naming has often been based on shared language, region, or historical relationship. Many English exonyms

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

have been used to refer to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Some of these names were based on foreign-language terms used by earlier explorers and colonists, while others resulted from the colonists' attempts to translate or transliterate endonyms

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, o ...

from the native languages. Other terms arose during periods of conflict between the colonists and Indigenous peoples.

Since the late 20th century, Indigenous peoples in the Americas have been more vocal about how they want to be addressed, pushing to suppress use of terms widely considered to be obsolete, inaccurate, or racist

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

. During the latter half of the 20th century and the rise of the Indian rights movement

The Red Power movement was a social movement led by Native American youth to demand self-determination for Native Americans in the United States. Organizations that were part of Red Power Movement included American Indian Movement (AIM) and ...

, the United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

responded by proposing the use of the term " Native American", to recognize the primacy of Indigenous peoples' tenure in the nation. As may be expected among people of over 400 different cultures in the US alone, not all of the people intended to be described by this term have agreed on its use or adopted it. No single group naming convention has been accepted by all Indigenous peoples in the Americas. Most prefer to be addressed as people of their tribe or nations when not speaking about Native Americans/American Indians as a whole.[ This has recently been acknowledged in the AP Stylebook. Some consider it improper to refer to Indigenous people as "Indigenous Americans" or to append any colonial nationality to the term because Indigenous cultures have existed prior to European colonization. Indigenous groups have territorial claims that are different from modern national and international borders, and when labelled as part of a country, their traditional lands are not acknowledged. Some who have written guidelines consider it more appropriate to describe an Indigenous person as "living in" or "of" the Americas, rather than calling them "American"; or to simply call them "Indigenous" without any addition of a colonial state.

]

History

Settlement of the Americas

Geneticist and professor of anthropology Jennifer Raff

Jennifer Anne Raff (born 1979, née Kedzie) is an American geneticist and an assistant professor of Anthropology at the University of Kansas. She specializes in anthropological genetics relating to the initial peopling of the Americas and subsequ ...

(2022) in the book "''A Genetic Chronicle of the First Peoples in the Americas''" summarized that the first people in the Americas diverged from Ancient East Asians about 36,000 years ago and expanded northwards into Siberia, where they encountered and interacted with a different Paleolithic Siberian population (known as Ancient North Eurasians), giving rise to both Paleosiberian peoples and Ancient Native Americans, which later migrated towards the Beringian region, became isolated from other populations, and subsequently populated the Americas.

Pre-Columbian era

The Pre-Columbian era refers to all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European and African influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original arrival in the

The Pre-Columbian era refers to all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European and African influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original arrival in the Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

to European colonization

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the modern sense be ...

during the early modern period. While technically referring to the era before

While technically referring to the era before Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

' voyages of 1492 to 1504, in practice the term usually includes the history of Indigenous cultures until Europeans either conquered or significantly influenced them. "Pre-Columbian" is used especially often in the context of discussing the pre-contact Mesoamerican

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Withi ...

Indigenous societies: Olmec

The Olmecs () were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization. Following a progressive development in Soconusco, they occupied the tropical lowlands of the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. It has been speculated that ...

; Toltec

The Toltec culture () was a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture that ruled a state centered in Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico, during the Epiclassic and the early Post-Classic period of Mesoamerican chronology, reaching prominence from 950 to 1150 CE. T ...

; Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan ( Spanish: ''Teotihuacán'') (; ) is an ancient Mesoamerican city located in a sub-valley of the Valley of Mexico, which is located in the State of Mexico, northeast of modern-day Mexico City. Teotihuacan is known today as ...

o' Zapotec; Mixtec

The Mixtecs (), or Mixtecos, are indigenous Mesoamerican peoples of Mexico inhabiting the region known as La Mixteca of Oaxaca and Puebla as well as La Montaña Region and Costa Chica Regions of the state of Guerrero. The Mixtec Cult ...

; Aztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl ...

and Maya civilization

The Maya civilization () of the Mesoamerican people is known by its ancient temples and glyphs. Its Maya script is the most sophisticated and highly developed writing system in the pre-Columbian Americas. It is also noted for its art, ...

s; and the complex cultures of the Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

: Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, ( Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The adm ...

, Moche culture

The Moche civilization (; alternatively, the Mochica culture or the Early, Pre- or Proto-Chimú) flourished in northern Peru with its capital near present-day Moche, Trujillo, Peru from about 100 to 700 AD during the Regional Development Epoch ...

, Muisca Confederation

The Muisca Confederation was a loose confederation of different Muisca rulers (''zaques'', ''zipas'', ''iraca'', and ''tundama'') in the central Andean highlands of present-day Colombia before the Spanish conquest of northern South America. T ...

, and Cañari

The Cañari (in Kichwa: Kañari) are an indigenous ethnic group traditionally inhabiting the territory of the modern provinces of Azuay and Cañar in Ecuador. They are descended from the independent pre-Columbian tribal confederation of the ...

.

The Norte Chico civilization (in present-day Peru) is one of the defining six original civilizations of the world, arising independently around the same time as that of

The Norte Chico civilization (in present-day Peru) is one of the defining six original civilizations of the world, arising independently around the same time as that of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

.oral history

Oral history is the collection and study of historical information about individuals, families, important events, or everyday life using audiotapes, videotapes, or transcriptions of planned interviews. These interviews are conducted with people wh ...

and through archaeological investigations. Others were contemporary with the contact and colonization period, and were documented in historical accounts of the time. A few, such as the Mayan, Olmec, Mixtec, Aztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl ...

and Nahua peoples

The Nahuas () are a group of the indigenous people of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. They comprise the largest indigenous group in Mexico and second largest in El Salvador. The Mexica (Aztecs) were of Nahua ethnicity, ...

, had their own written languages and records. However, the European colonists of the time worked to eliminate non-Christian beliefs, and burned many pre-Columbian written records. Only a few documents remained hidden and survived, leaving contemporary historians with glimpses of ancient culture and knowledge.

According to both Indigenous and European accounts and documents, American civilizations before and at the time of European encounter had achieved great complexity and many accomplishments. For instance, the Aztecs built one of the largest cities in the world, Tenochtitlan

, ; es, Tenochtitlan also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, ; es, México-Tenochtitlan was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear. The date 13 March 1325 was ...

(the historical site of what would become Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

), with an estimated population of 200,000 for the city proper and a population of close to five million for the extended empire. By comparison, the largest European cities in the 16th century were Constantinople and Paris with 300,000 and 200,000 inhabitants respectively. The population in London, Madrid and Rome hardly exceeded 50,000 people. In 1523, right around the time of the Spanish conquest, the entire population in the country of England was just under three million people. This fact speaks to the level of sophistication, agriculture, governmental procedure and rule of law that existed in Tenochtitlan, needed to govern over such a large citizenry. Indigenous civilizations also displayed impressive accomplishments in astronomy and mathematics, including the most accurate calendar in the world. The domestication of maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

or corn required thousands of years of selective breeding, and continued cultivation of multiple varieties was done with planning and selection, generally by women.

Inuit, Yupik, Aleut, and Indigenous creation myth

A creation myth (or cosmogonic myth) is a symbolic narrative of how the world began and how people first came to inhabit it., "Creation myths are symbolic stories describing how the universe and its inhabitants came to be. Creation myths develo ...

s tell of a variety of origins of their respective peoples. Some were "always there" or were created by gods or animals, some migrated from a specified compass point, and others came from "across the ocean".

European colonization

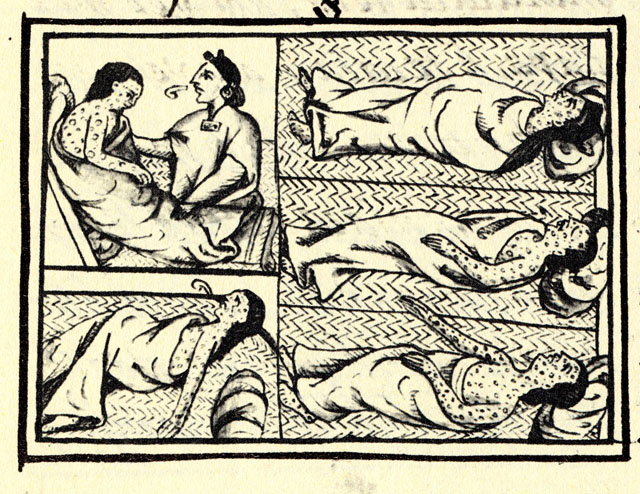

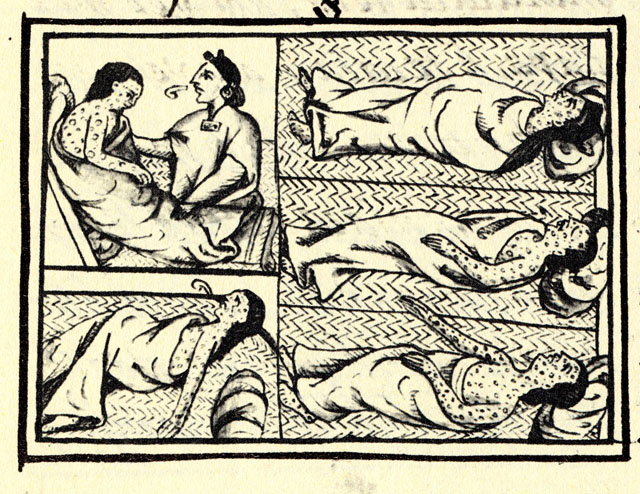

The European colonization of the Americas fundamentally changed the lives and cultures of the resident Indigenous peoples. Although the exact pre-colonization population-count of the Americas is unknown, scholars estimate that Indigenous populations diminished by between 80% and 90% within the first centuries of European colonization. The majority of these losses are attributed to the introduction of Afro-Eurasian diseases into the Americas. Epidemics ravaged the Americas with diseases such as

The European colonization of the Americas fundamentally changed the lives and cultures of the resident Indigenous peoples. Although the exact pre-colonization population-count of the Americas is unknown, scholars estimate that Indigenous populations diminished by between 80% and 90% within the first centuries of European colonization. The majority of these losses are attributed to the introduction of Afro-Eurasian diseases into the Americas. Epidemics ravaged the Americas with diseases such as smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

, and cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

, which the early colonists brought from Europe.

The spread of infectious diseases was slow initially, as most Europeans were not actively or visibly infected, due to inherited immunity from generations of exposure to these diseases in Europe. This changed when the Europeans began the human trafficking

Human trafficking is the trade of humans for the purpose of forced labour, sexual slavery, or commercial sexual exploitation for the trafficker or others. This may encompass providing a spouse in the context of forced marriage, or the extr ...

of massive numbers of enslaved Western and Central African people to the Americas. Like Indigenous peoples, these African people, newly exposed to European diseases, lacked any inherited resistances to the diseases of Europe. In 1520 an African who had been infected with smallpox had arrived in Yucatán. By 1558, the disease had spread throughout South America and had arrived at the Plata basin.Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

s of Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

, represented the dominant culture in the Greater Antilles

The Greater Antilles ( es, Grandes Antillas or Antillas Mayores; french: Grandes Antilles; ht, Gwo Zantiy; jam, Grieta hAntiliiz) is a grouping of the larger islands in the Caribbean Sea, including Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, a ...

and the Bahamas. Within thirty years about 70% of the Taínos had died.[ They had no immunity to European diseases, so outbreaks of ]measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

ravaged their population. One such outbreak occurred in a camp of enslaved Africans, where smallpox spread to the nearby Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

population and reduced their numbers by 50%.encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

, which included religious education and protection from warring tribes, eventually led to the last great Taíno rebellion (1511–1529).

Following years of mistreatment, the Taínos began to adopt suicidal behaviors, with women aborting or killing their infants and men jumping from cliffs or ingesting untreated cassava

''Manihot esculenta'', commonly called cassava (), manioc, or yuca (among numerous regional names), is a woody shrub of the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, native to South America. Although a perennial plant, cassava is extensively cultivated ...

, a violent poison.[''Espagnols-Indiens: le choc des civilisations"'' in '']L'Histoire

''L'Histoire'' is a monthly mainstream French magazine dedicated to historical studies, recognized by peers as the most important historical popular magazine (as opposed to specific university journals or less scientific popular historical magaz ...

'', n°322, July–August 2007, pp.14–21

Eventually, a Taíno Cacique named Enriquillo managed to hold out in the Baoruco Mountain Range

The Bahoruco Mountain Range—Sierra de Bahoruco (or Sierra de Bahoruco) is a mountain range located in the far southwestern region of the Dominican Republic. It is within Pedernales, Independencia, Barahona, and Bahoruco Provinces. A large par ...

for thirteen years, causing serious damage to the Spanish, Carib-held plantations and their Indian auxiliaries. Hearing of the seriousness of the revolt,

Emperor Charles V

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fr ...

(also King of Spain) sent captain Francisco Barrionuevo to negotiate a peace treaty with the ever-increasing number of rebels. Two months later, after consultation with the Audencia of Santo Domingo, Enriquillo was offered any part of the island to live in peace.

The Laws of Burgos, 1512–1513, were the first codified set of laws governing the behavior of Spanish settlers in America, particularly with regard to Indigenous peoples. The laws forbade the maltreatment of them and endorsed their conversion to Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. The Spanish crown found it difficult to enforce these laws in distant colonies.

Epidemic disease was the overwhelming cause of the

Epidemic disease was the overwhelming cause of the population decline

A population decline (also sometimes called underpopulation, depopulation, or population collapse) in humans is a reduction in a human population size. Over the long term, stretching from prehistory to the present, Earth's total human population ...

of the Indigenous peoples. After initial contact with Europeans and Africans, Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by thei ...

diseases caused the deaths of 90 to 95% of the native population of the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

in the following 150 years. Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

killed from one third to half of the native population of Hispaniola in 1518. By killing the Incan ruler Huayna Capac

Huayna Capac (with many alternative transliterations; 1464/1468–1524) was the third Sapan Inka of the Inca Empire, born in Tumipampa sixth of the Hanan dynasty, and eleventh of the Inca civilization. Subjects commonly approached Sapa Inkas add ...

, smallpox caused the Inca Civil War

The Inca Civil War, also known as the Inca Dynastic War, the Inca War of Succession, or, sometimes, the War of the Two Brothers, was fought between half-brothers Huáscar and Atahualpa, sons of Huayna Capac, over succession to the throne of ...

of 1529–1532. Smallpox was only the first epidemic. Typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

(probably) in 1546, influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

and smallpox together in 1558, smallpox again in 1589, diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks more than 10% of those diagnosed with the disease may die. Signs and s ...

in 1614, measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

in 1618—all ravaged the remains of Inca culture.

Smallpox killed millions of native inhabitants of Mexico. Unintentionally introduced at Veracruz with the arrival of Pánfilo de Narváez

Pánfilo de Narváez (; 147?–1528) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' and soldier in the Americas. Born in Spain, he first embarked to Jamaica in 1510 as a soldier. He came to participate in the conquest of Cuba and led an expedition to Camag� ...

on 23 April 1520, smallpox ravaged Mexico in the 1520s, possibly killing over 150,000 in Tenochtitlán (the heartland of the Aztec Empire) alone, and aiding in the victory of Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

over the Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire or the Triple Alliance ( nci, Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān, �jéːʃkaːn̥ t͡ɬaʔtoːˈlóːjaːn̥ was an alliance of three Nahua city-states: , , and . These three city-states ruled that area in and around the Valley of Mexi ...

at Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City) in 1521.yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

, that were relatively manageable if infected as a child, but were deadly if infected as an adult. Children could often survive the disease, resulting in immunity to the disease for the rest of their lives. But contact with adult populations without this childhood or inherited immunity would result in these diseases proving fatal.Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, who historically lived in the Greate ...

s of the Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc be ...

. Their culture was destroyed by 1650. Only 500 had survived by the year 1550, though the bloodlines continued through to the modern populace. In Amazonia, Indigenous societies weathered, and continue to suffer, centuries of colonization and genocide.

Contact with European diseases such as smallpox and measles killed between 50 and 67 per cent of the Indigenous population of North America in the first hundred years after the arrival of Europeans. Some 90 per cent of the native population near

Contact with European diseases such as smallpox and measles killed between 50 and 67 per cent of the Indigenous population of North America in the first hundred years after the arrival of Europeans. Some 90 per cent of the native population near Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as th ...

died of smallpox in an epidemic in 1617–1619. In 1633, in Fort Orange (New Netherland), the Native Americans there were exposed to smallpox because of contact with Europeans. As it had done elsewhere, the virus wiped out entire population-groups of Native Americans. It reached Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York. The Canada–United States border sp ...

in 1636, and the lands of the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

by 1679. During the 1770s smallpox killed at least 30% of the West Coast Native Americans. The 1775–82 North American smallpox epidemic and the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic brought devastation and drastic population depletion among the Plains Indians

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) of ...

. In 1832 the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination

The smallpox vaccine is the first vaccine to be developed against a contagious disease. In 1796, British physician Edward Jenner demonstrated that an infection with the relatively mild cowpox virus conferred immunity against the deadly smallpox ...

program for Native Americans (''The Indian Vaccination Act of 1832'').

The Indigenous peoples in Brazil

Indigenous peoples in Brazil ( pt, povos indígenas no Brasil) or Indigenous Brazilians ( pt, indígenas brasileiros, links=no) once comprised an estimated 2000 tribes and nations inhabiting what is now the country of Brazil, before European con ...

declined from a pre-Columbian high of an estimated three million to some 300,000 in 1997.Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

and other Europeans re-introduced horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

s to the Americas. Some of these animals escaped and began to breed and increase their numbers in the wild.

The re-introduction of the horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

, extinct in the Americas for over 7500 years, had a profound impact on Indigenous cultures

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

in the Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, a ...

of North America and in Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and g ...

in South America. By domesticating horses, some tribes had great success: horses enabled them to expand their territories, exchange more goods with neighboring tribes, and more easily capture game

A game is a structured form of play, usually undertaken for entertainment or fun, and sometimes used as an educational tool. Many games are also considered to be work (such as professional players of spectator sports or games) or art (suc ...

, especially bison

Bison are large bovines in the genus ''Bison'' (Greek: "wild ox" (bison)) within the tribe Bovini. Two extant and numerous extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, ''B. bison'', found only in North A ...

.

Indigenous historical trauma (IHT)

Indigenous historical trauma (IHT) is the trauma that can accumulate across generations that develops as a result of the historical ramifications of

Indigenous historical trauma (IHT) is the trauma that can accumulate across generations that develops as a result of the historical ramifications of colonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

and is linked to mental and physical health hardships and population decline.[Gone, Joseph P., William E. Hartmann, Andrew Pomerville, Dennis C. Wendt, Sarah H. Klem, and Rachel L. Burrage. 2019.]

The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for indigenous populations in the USA and Canada: A systematic review

." ''American Psychologist

''American Psychologist'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal published by the American Psychological Association. The journal publishes articles of broad interest to psychologists, including empirical reports and scholarly reviews covering scien ...

'' 74(1):20–35. . IHT affects many different people in a multitude of ways because the Indigenous community and their history is diverse.

Many studies (such as Whitbeck et al., 2014; Brockie, 2012; Anastasio et al., 2016;[Tucker, Raymond P., LaRicka R. Wingate, Victoria M. O'Keefe. 2016. "Historical loss thinking and symptoms of depression are influenced by ethnic experience in American Indian college students." '']Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology

''Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology'' is the quarterly scientific journal of the American Psychological Association Division 45: Society for the Psychological Study of Culture, Ethnicity, and Race. ''Cultural Diversity and Ethnic M ...

'' 22(3):350–58. have evaluated the impact of IHT on health outcomes of Indigenous communities from the United States and Canada. IHT is a difficult term to standardize and measure because of the vast and variable diversity of Indigenous people and their communities. Therefore, it is an arduous task to assign an operational definition

An operational definition specifies concrete, replicable procedures designed to represent a construct. In the words of American psychologist S.S. Stevens (1935), "An operation is the performance which we execute in order to make known a concept." F ...

and systematically collect data when studying IHT. Many of the studies that incorporate IHT measure it in different ways, making it hard to compile data and review it holistically. This is an important point that provides context for the following studies that attempt to understand the relationship between IHT and potential adverse health impacts.

Some of the methodologies to measure IHT include a "Historical Losses Scale" (HLS), "Historical Losses Associated Symptoms Scale" (HLASS), and residential school ancestry studies.anxiety

Anxiety is an emotion which is characterized by an unpleasant state of inner turmoil and includes feelings of dread over anticipated events. Anxiety is different than fear in that the former is defined as the anticipation of a future threat wh ...

, suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation, or suicidal thoughts, means having thoughts, ideas, or ruminations about the possibility of ending one's own life.World Health Organization, ''ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics'', ver. 09/2020MB26.A Suicidal ideatio ...

, suicide attempt

A suicide attempt is an attempt to die by suicide that results in survival. It may be referred to as a "failed" or "unsuccessful" suicide attempt, though these terms are discouraged by mental health professionals for implying that a suicide resu ...

s, polysubstance abuse, PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental and behavioral disorder that can develop because of exposure to a traumatic event, such as sexual assault, warfare, traffic collisions, child abuse, domestic violence, or other threats on ...

, depression, binge eating

Binge eating is a pattern of disordered eating which consists of episodes of uncontrollable eating. It is a common symptom of eating disorders such as binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa. During such binges, a person rapidly consumes an ...

, anger, and sexual abuse.

Agriculture

Plants

In the course of thousands of years, Indigenous peoples domesticated, bred and cultivated a large array of plant species. These species now constitute between 50% and 60% of all crops in cultivation worldwide. In certain cases, the Indigenous peoples developed entirely new species and strains through artificial selection

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant mal ...

, as with the domestication and breeding of maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

from wild ''teosinte

''Zea'' is a genus of flowering plants in the grass family. The best-known species is ''Z. mays'' (variously called maize, corn, or Indian corn), one of the most important crops for human societies throughout much of the world. The four wild spe ...

'' grasses in the valleys of southern Mexico. Numerous such agricultural products retain their native names in the English and Spanish lexicons.

The South American highlands became a center of early agriculture. Genetic testing of the wide variety of cultivar

A cultivar is a type of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and when propagated retain those traits. Methods used to propagate cultivars include: division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue culture ...

s and wild species suggests that the potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Uni ...

has a single origin in the area of southern Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

, from a species in the ''Solanum brevicaule

''Solanum brevicaule'' is a tuberous perennial plant of the family Solanaceae. The species is native to South America (Argentina, Bolivia, and Peru). It is related to the potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanu ...

'' complex. Over 99% of all modern cultivated potatoes worldwide are descendants of a subspecies Indigenous to south-central Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

,Linda Newson

Linda Ann Newson, FBA, OBE, is director of the Institute of Latin American Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal publi ...

, "It is clear that in pre-Columbian times some groups struggled to survive and often suffered food shortages and famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompan ...

s, while others enjoyed a varied and substantial diet."

Persistent drought around AD 850 coincided with the collapse of Classic Maya

A classic is an outstanding example of a particular style; something of lasting worth or with a timeless quality; of the first or highest quality, class, or rank – something that exemplifies its class. The word can be an adjective (a '' ...

civilization, and the famine of One Rabbit (AD 1454) was a major catastrophe in Mexico.

Indigenous peoples of North America began practicing farming

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled peopl ...

approximately 4,000 years ago, late in the Archaic period of North American cultures. Technology had advanced to the point where pottery had started to become common and the small-scale felling of trees had become feasible. Concurrently, the Archaic Indigenous peoples began using fire in a controlled manner. They carried out intentional burning of vegetation to mimic the effects of natural fires that tended to clear forest understories. It made travel easier and facilitated the growth of herbs and berry-producing plants, which were important both for food and for medicines.Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

valley, Europeans noted that Native Americans managed groves of nut- and fruit-trees not far from villages and towns and their gardens and agricultural fields. They would have used prescribed burning

A controlled or prescribed burn, also known as hazard reduction burning, backfire, swailing, or a burn-off, is a fire set intentionally for purposes of forest management, farming, prairie restoration or greenhouse gas abatement. A control ...

further away, in forest and prairie areas.maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

(or "corn") arguably the most important crop in the world. Other significant crops include cassava

''Manihot esculenta'', commonly called cassava (), manioc, or yuca (among numerous regional names), is a woody shrub of the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, native to South America. Although a perennial plant, cassava is extensively cultivated ...

; chia; squash

Squash may refer to:

Sports

* Squash (sport), the high-speed racquet sport also known as squash racquets

* Squash (professional wrestling), an extremely one-sided match in professional wrestling

* Squash tennis, a game similar to squash but pla ...

(pumpkins, zucchini, marrow, acorn squash

Acorn squash (''Cucurbita pepo'' var. turbinata), also called pepper squash or Des Moines squash, is a winter squash with distinctive longitudinal ridges on its exterior and sweet, yellow-orange flesh inside. Although considered a winter squash, a ...

, butternut squash

Butternut squash ('' Cucurbita moschata''), known in Australia and New Zealand as butternut pumpkin or gramma, is a type of winter squash that grows on a vine. It has a sweet, nutty taste similar to that of a pumpkin. It has tan-yellow skin an ...

); the pinto bean

The pinto bean () is a variety of common bean (''Phaseolus vulgaris''). In Spanish they are called , literally "painted bean" (compare pinto horse). It is the most popular bean by crop production in Northern Mexico and the Southwestern United Sta ...

, ''Phaseolus

''Phaseolus'' (bean, wild bean) is a genus of herbaceous to woody annual and perennial vines in the family Fabaceae containing about 70 plant species, all native to the Americas, primarily Mesoamerica.

It is one of the most economically importan ...

'' beans including most common bean

''Phaseolus vulgaris'', the common bean, is a herbaceous annual plant grown worldwide for its edible dry seeds or green, unripe pods. Its leaf is also occasionally used as a vegetable and the straw as fodder. Its botanical classification, alo ...

s, tepary beans and lima bean

A lima bean (''Phaseolus lunatus''), also commonly known as the butter bean, sieva bean, double bean, Madagascar bean, or wax bean is a legume grown for its edible seeds or beans.

Origin and uses

''Phaseolus lunatus'' is found in Meso- and Sou ...

s; tomato

The tomato is the edible berry of the plant ''Solanum lycopersicum'', commonly known as the tomato plant. The species originated in western South America, Mexico, and Central America. The Mexican Nahuatl word gave rise to the Spanish word ...

es; potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Uni ...

es; sweet potato

The sweet potato or sweetpotato ('' Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the bindweed or morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its large, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable. The young ...

es; avocado

The avocado (''Persea americana'') is a medium-sized, evergreen tree in the laurel family ( Lauraceae). It is native to the Americas and was first domesticated by Mesoamerican tribes more than 5,000 years ago. Then as now it was prized for ...

s; peanut

The peanut (''Arachis hypogaea''), also known as the groundnut, goober (US), pindar (US) or monkey nut (UK), is a legume crop grown mainly for its edible seeds. It is widely grown in the tropics and subtropics, important to both small an ...

s; cocoa bean

The cocoa bean (technically cocoa seed) or simply cocoa (), also called the cacao bean (technically cacao seed) or cacao (), is the dried and fully Fermentation, fermented seed of ''Theobroma cacao'', from which cocoa solids (a mixture of non ...

s (used to make chocolate

Chocolate is a food made from roasted and ground cacao seed kernels that is available as a liquid, solid, or paste, either on its own or as a flavoring agent in other foods. Cacao has been consumed in some form since at least the Olmec ci ...

); vanilla

Vanilla is a spice derived from orchids of the genus '' Vanilla'', primarily obtained from pods of the Mexican species, flat-leaved vanilla ('' V. planifolia'').

Pollination is required to make the plants produce the fruit from whic ...

; strawberries

The garden strawberry (or simply strawberry; ''Fragaria × ananassa'') is a widely grown hybrid species of the genus '' Fragaria'', collectively known as the strawberries, which are cultivated worldwide for their fruit. The fruit is widely ap ...

; pineapple

The pineapple (''Ananas comosus'') is a tropical plant with an edible fruit; it is the most economically significant plant in the family Bromeliaceae. The pineapple is indigenous to South America, where it has been cultivated for many centuri ...

s; peppers

Pepper or peppers may refer to:

Food and spice

* Piperaceae or the pepper family, a large family of flowering plant

** Black pepper

* ''Capsicum'' or pepper, a genus of flowering plants in the nightshade family Solanaceae

** Bell pepper

** Chili ...

(species and varieties of ''Capsicum

''Capsicum'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the nightshade family Solanaceae, native to the Americas, cultivated worldwide for their chili pepper or bell pepper fruit.

Etymology and names

The generic name may come from Latin , me ...

'', including bell pepper

The bell pepper (also known as paprika, sweet pepper, pepper, or capsicum ) is the fruit of plants in the Grossum Group of the species ''Capsicum annuum''. Cultivars of the plant produce fruits in different colors, including red, yellow, orange ...

s, jalapeño

The jalapeño ( , , ) is a medium-sized chili pepper pod type cultivar of the species ''Capsicum annuum''. A mature jalapeño chili is long and hangs down with a round, firm, smooth flesh of wide. It can have a range of pungency, with Scov ...

s, paprika

Paprika ( US , ; UK , ) is a spice made from dried and ground red peppers. It is traditionally made from '' Capsicum annuum'' varietals in the Longum group, which also includes chili peppers, but the peppers used for paprika tend to be milder ...

and chili pepper

Chili peppers (also chile, chile pepper, chilli pepper, or chilli), from Nahuatl '' chīlli'' (), are varieties of the berry-fruit of plants from the genus ''Capsicum'', which are members of the nightshade family Solanaceae, cultivated for ...

s); sunflower seeds

The sunflower seed is the seed of the sunflower (''Helianthus annuus''). There are three types of commonly used sunflower seeds: linoleic (most common), high oleic, and sunflower oil seeds. Each variety has its own unique levels of monounsatu ...

; rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds. Thailand, Malaysia, and ...

; brazilwood

''Paubrasilia echinata'' is a species of flowering plant in the legume family, Fabaceae, that is endemic to the Atlantic Forest of Brazil. It is a Brazilian timber tree commonly known as Pernambuco wood or brazilwood ( pt, pau-de-pernambuco, ; ...

; chicle

Chicle () is a natural gum traditionally used in making chewing gum and other products. It is collected from several species of Mesoamerican trees in the genus '' Manilkara'', including '' M. zapota'', '' M. chicle'', '' M. staminodella'', and ' ...

; tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

; coca

Coca is any of the four cultivated plants in the family Erythroxylaceae, native to western South America. Coca is known worldwide for its psychoactive alkaloid, cocaine.

The plant is grown as a cash crop in the Argentine Northwest, Bolivia, ...

; blueberries

Blueberries are a widely distributed and widespread group of perennial flowering plants with blue or purple berries. They are classified in the section ''Cyanococcus'' within the genus ''Vaccinium''. ''Vaccinium'' also includes cranberries, bi ...

, cranberries

Cranberries are a group of evergreen dwarf shrubs or trailing vines in the subgenus ''Oxycoccus'' of the genus ''Vaccinium''. In Britain, cranberry may refer to the native species ''Vaccinium oxycoccos'', while in North America, cranberry m ...

, and some species of cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

.

Studies of contemporary Indigenous environmental management—including of agro-forestry practices among Itza Maya

Maya may refer to:

Civilizations

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Maya language, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (Ethiopia), a popul ...

in Guatemala and of hunting and fishing among the Menominee

The Menominee (; mez, omǣqnomenēwak meaning ''"Menominee People"'', also spelled Menomini, derived from the Ojibwe language word for "Wild Rice People"; known as ''Mamaceqtaw'', "the people", in the Menominee language) are a federally recog ...

of Wisconsin—suggest that longstanding "sacred values" may represent a summary of sustainable millennial traditions.

Animals

Indigenous peoples also domesticated some animals, such as turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

s, llama

The llama (; ) (''Lama glama'') is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a meat and pack animal by Andean cultures since the Pre-Columbian era.

Llamas are social animals and live with others as a herd. Their wool is soft ...

s, alpaca

The alpaca (''Lama pacos'') is a species of South American camelid mammal. It is similar to, and often confused with, the llama. However, alpacas are often noticeably smaller than llamas. The two animals are closely related and can success ...

s, guinea-pig

The guinea pig or domestic guinea pig (''Cavia porcellus''), also known as the cavy or domestic cavy (), is a species of rodent belonging to the genus ''Cavia'' in the family Caviidae. Breeders tend to use the word ''cavy'' to describe the ani ...

s, and Muscovy ducks.

Culture

Cultural practices in the Americas seem to have been shared mostly within geographical zones where distinct ethnic groups adopting shared cultural traits, similar technologies, and social organizations. An example of such a cultural area

In anthropology and geography, a cultural region, cultural sphere, cultural area or culture area refers to a geography with one relatively homogeneous human activity or complex of activities (culture). Such activities are often associated ...

is Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Wit ...

, where millennia of coexistence and shared development among the peoples of the region produced a fairly homogeneous culture with complex agricultural and social patterns. Another well-known example is the North American plains where until the 19th century several peoples shared the traits of nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

ic hunter-gatherers based primarily on buffalo hunting.

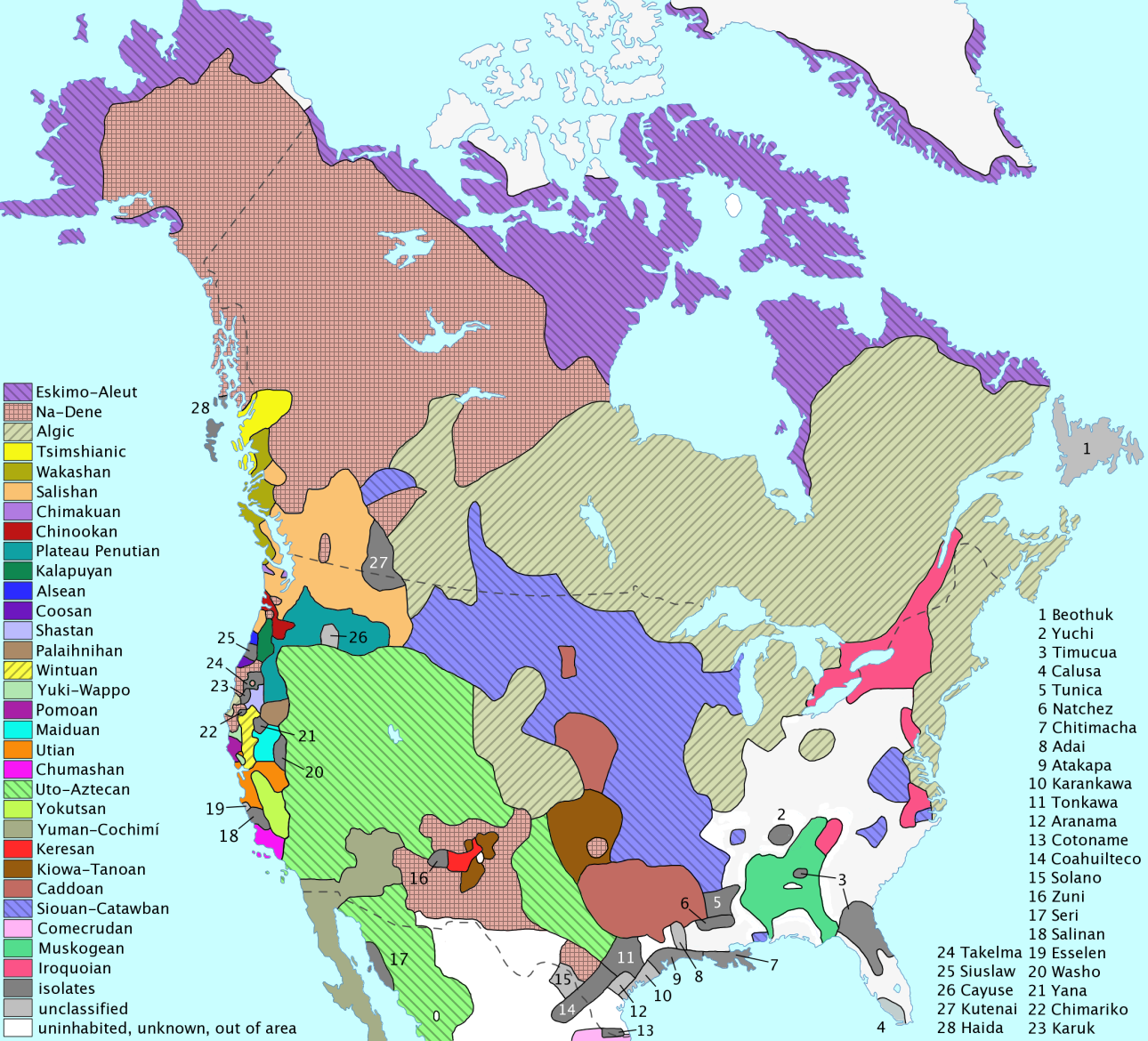

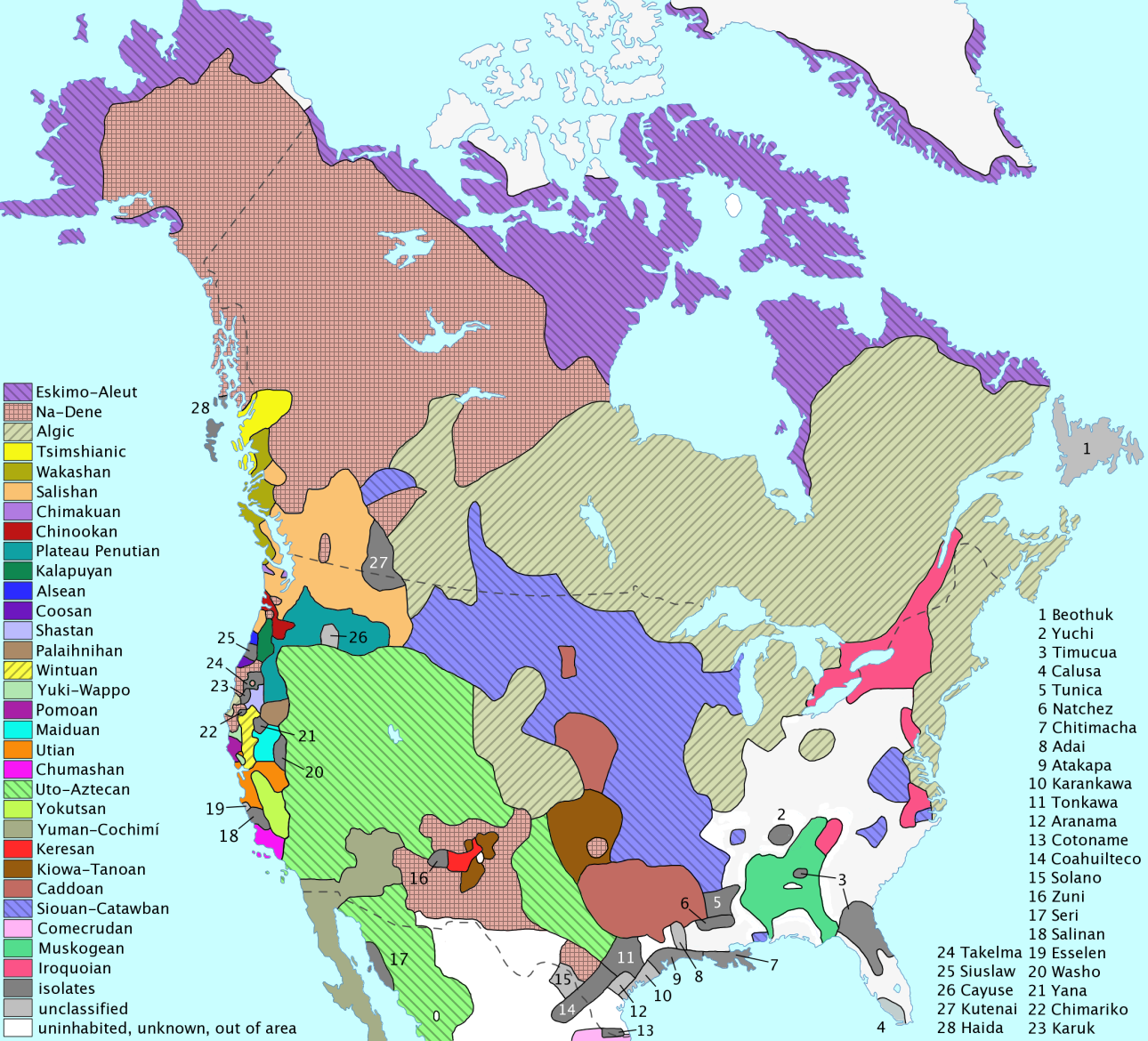

Languages

The languages of the North American Indians have been classified into 56 groups or stock tongues, in which the spoken languages of the tribes may be said to centre. In connection with speech, reference may be made to gesture language which was highly developed in parts of this area.

Of equal interest is the picture writing especially well developed among the Chippewas and Delawares.

The languages of the North American Indians have been classified into 56 groups or stock tongues, in which the spoken languages of the tribes may be said to centre. In connection with speech, reference may be made to gesture language which was highly developed in parts of this area.

Of equal interest is the picture writing especially well developed among the Chippewas and Delawares.

Writing systems

Beginning in the 1st millennium BCE, pre-Columbian cultures in

Beginning in the 1st millennium BCE, pre-Columbian cultures in Mesoamerica