Italienische Reise on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Italian Journey'' (in the German original: ) is

The work begins with a famous

The work begins with a famous

While in Italy, Goethe aspired to witness and to breathe the conditions and milieu of a once highly – and in certain respects still – cultured area endowed with many significant works of art. Apart from the impetus to study the Mediterranean's natural qualities, he was first and foremost interested in the remains of

While in Italy, Goethe aspired to witness and to breathe the conditions and milieu of a once highly – and in certain respects still – cultured area endowed with many significant works of art. Apart from the impetus to study the Mediterranean's natural qualities, he was first and foremost interested in the remains of

Goethe stayed almost three months in

Goethe stayed almost three months in

The ''Italian Journey'' is divided sequentially as follows:

:Part One

::*September 1786: from Karlsbad (now Karlovy Vary in the

The ''Italian Journey'' is divided sequentially as follows:

:Part One

::*September 1786: from Karlsbad (now Karlovy Vary in the

File:Malcesine Goetheherme.jpg, Goethe's Herma in the courtyard of the

The poet himself remained inspired by his travel impressions throughout his life. Goethe's house in Weimar is filled with antique works of art and pictures that allude to Italy, as was his parents' house in Frankfurt, since his father

The poet himself remained inspired by his travel impressions throughout his life. Goethe's house in Weimar is filled with antique works of art and pictures that allude to Italy, as was his parents' house in Frankfurt, since his father

Italienische Reise, vol. 1

Italienische Reise, vol. 2

Interactive Map with spots of Goethe's "Italienische Reise" with text and images.

ref>

Wiedergeburt in Italien

*

Scarabocchio

' (2008), a novel by

Goethe, his love rivals and evidence of a generalized anxiety disorder.

Humane Medicine, 2008. An issue by Giuseppe Paolo Mazzarello, MD. {{Authority control 1816 non-fiction books 1817 non-fiction books Travel books Works by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Books about Italy German non-fiction books

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as t ...

's report on his travels to Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

from 1786 to 1788 that was published in 1816 & 1817. The book is based on Goethe's diaries Diaries may refer to:

* the plural of diary

*''Diaries: 1971-1976'', a 1981 documentary by Ed Pincus

*'' Diaries 1969–1979: The Python Years'', a 2006 book by Michael Palin

*''OFW Diaries

''OFW Diaries'' is a Philippine television documentary ...

and is smoothed in style, lacks the spontaneity of his diary report and is augmented with the addition of afterthoughts and reminiscences.

At the beginning of September 1786, when Goethe had just turned 37, he "slipped away", in his words, from his duties as Privy Councillor in the Duchy of Weimar, from a long platonic affair with a court lady and from his immense fame as the author of the novel ''The Sorrows of Young Werther

''The Sorrows of Young Werther'' (; german: Die Leiden des jungen Werthers) is a 1774 epistolary novel by Johann Wolfgang Goethe, which appeared as a revised edition in 1787. It was one of the main novels in the '' Sturm und Drang'' period in Ge ...

'' and the stormy play ''Götz von Berlichingen

Gottfried "Götz" von Berlichingen (1480 – 23 July 1562), also known as Götz of the Iron Hand, was a German (Franconian) Imperial Knight (''Reichsritter''), mercenary, and poet. He was born around 1480 into the noble family of Berliching ...

'', and he took what became a licensed leave of absence. He was able to persuade his employer, Duke Carl August, to agree to a paid absence.

By May 1788 he had travelled to Italy via Innsbruck and the Brenner Pass and visited Lake Garda

Lake Garda ( it, Lago di Garda or ; lmo, label= Eastern Lombard, Lach de Garda; vec, Ƚago de Garda; la, Benacus; grc, Βήνακος) is the largest lake in Italy.

It is a popular holiday location in northern Italy, about halfway between ...

, Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

, Vicenza

Vicenza ( , ; ) is a city in northeastern Italy. It is in the Veneto region at the northern base of the ''Monte Berico'', where it straddles the Bacchiglione River. Vicenza is approximately west of Venice and east of Milan.

Vicenza is a thr ...

, Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

, Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

, Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

and Alban Hills, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. He wrote many letters to a number of friends in Germany, which he later used as the basis for ''Italian Journey''.

Appraisal

:''Et in Arcadia ego'' ''Italian Journey'' initially takes the form of a diary, with events and descriptions written up apparently quite soon after they were experienced. The impression is in one sense true, since Goethe was clearly working from journals and letters he composed at the time – and by the end of the book he is openly distinguishing between his old correspondence and what he calls ''reporting''. But there is also a strong and indeed elegant sense of fiction about the whole, a sort of composed immediacy. Goethe said in a letter that the work was "both entirely truthful and a graceful fairy-tale". It had to be something of a fairy-tale, since it was written between thirty and more than forty years after the journey, in 1816 and 1828–29.Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

tag, ''Et in Arcadia ego'', although originally Goethe used the German translation, ''Auch ich in Arkadien'', which alters the meaning. This Latin phrase is usually imagined as spoken by Death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

– this is its sense, for example, in W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

's poem called "Et in Arcadia ego" – suggesting that every paradise is afflicted by mortality. Conversely, what Goethe's ''Auch ich in Arkadien'' says is "Even I managed to get to paradise", with the implication that we could all get there if we chose. If death is universal, the possibility of paradise might be universal too. This possibility wouldn't preclude its loss, and might even require it, or at least require that some of us should lose it. The book ends with a quotation from Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

's ''Tristia

The ''Tristia'' ("Sorrows" or "Lamentations") is a collection of letters written in elegiac couplets by the Augustan poet Ovid during his exile from Rome. Despite five books of his copious bewailing of his fate, the immediate cause of August ...

'', regretting his expulsion from Rome. ''Cum repeto noctem'', Goethe writes in the middle of his own German, as well as citing a whole passage: "When I remember the night..." He is already storing up not only plentiful nostalgia and regret, but also a more complicated treasure: the certainty that he didn't merely imagine the land where others live happily ever after.

Content

"We are all pilgrims who seek Italy", Goethe wrote in a poem two years after his return to Germany from his almost two-year spell in the land he had long dreamed of. For Goethe, Italy was the warm passionate south as opposed to the dank cautious north; the place where the classical past was still alive, although in ruins; a sequence of landscapes, colours, trees, manners, cities, monuments he had so far seen only in his writing. He described himself as "the mortal enemy of mere words" or what he also called "empty names". He needed to fill the names with meaning and, as he rather strangely put it, "to discover myself in the objects I see", literally "to learn to know myself by or through the objects". He also writes of his old habit of "clinging to the objects", which pays off in the new location. He wanted to know that what he thought might be paradise actually existed, even if it wasn't entirely paradise, and even if he didn't in the end want to stay there.classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, furthermore in Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

, but much less in the then predominant Baroque art. Medieval art he treated with complete contempt. During his stay in Assisi, he did not visit the famous Giotto

Giotto di Bondone (; – January 8, 1337), known mononymously as Giotto ( , ) and Latinised as Giottus, was an Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages. He worked during the Gothic/ Proto-Renaissance period. G ...

frescoes in the Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi

The Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Basilica di San Francesco d'Assisi; la, Basilica Sancti Francisci Assisiensis) is the mother church of the Roman Catholic Order of Friars Minor Conventual in Assisi, a town in the Umbria region in ce ...

. Many critics have questioned this strange choice. In Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

, where he enthusiastically commends the harmony and fine proportions of the city amphitheater, he asserts this is the first true piece of Classical art he has witnessed. Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

, too, holds treasures for his artistic education, and he soon becomes fascinated by the Italian style of living. He acquires Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be one of ...

's printed works and studies them intensively.

After a longer stop in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

and a very short stop in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

, he arrives in Rome. It was here that he met several respected German artists, and made friends with Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, known as the ''Goethe Tischbein'' (15 February 1751 in Haina – 26 February 1829 in Eutin), was a German painter from the Tischbein family of artists.

Biography

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein was born on ...

and notable Neoclassical painter, Angelica Kauffman. He visited the famous art collections of Rome with her and her husband Antonio Zucchi

Antonio Pietro Francesco Zucchi (1 May 1726 – 1 December 1795) was an Italian painter and printmaker of the Neoclassic period.

Life

Zucchi was born in Venice, he studied under his uncle Carlo Zucchi and later Francesco Fontebasso and Jacopo ...

. Other artists he frequently met were the painter Johann Friedrich Reiffenstein

* Johann Friedrich ReiffensteinAlso spelled Reifstein and Reffenstein(born 22 November 1719, Ragnit, – died 6 October 1793, Rome) was a German cicerone for grand tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a ...

and the writer Karl Philipp Moritz

Karl Philipp Moritz ( Hameln, 15 September 1756 – Berlin, 26 June 1793) was a German author, editor and essayist of the ''Sturm und Drang'', late Enlightenment, and classicist periods, influencing early German Romanticism as well. He led a ...

.

Goethe lived with Tischbein in his flat in Via del Corso

The Via del Corso is a main street in the historical centre of Rome. It is straight in an area otherwise characterized by narrow meandering alleys and small piazzas. Considered a wide street in ancient times, the Corso is approximately 10 metres w ...

18, Rome, today Casa di Goethe, a museum on the ''Italian Journey''. He stayed there from October 1786 until February 1787 when they travelled together to Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and Goethe went on to Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, and again from June 1787 until April 1788. Tischbein shared the house with a number of other German and Swiss painters. He painted one of the most famous portraits of Goethe, ''Goethe in the Roman Campagna

''Goethe in the Roman Campagna'' is a painting by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, a German Neoclassical painter, depicting Johann Wolfgang von Goethe when the writer was travelling in Italy. Goethe's book on his travels to Italy from 1786–88, ...

''. Goethe looked everywhere for ancient works of art, in museums and private collections, travelled twice to the Royal Palace of Portici

The Royal Palace of Portici (''Reggia di Portici'' or ''Palazzo Reale di Portici''; nap, Reggia ‘e Puortece) is a former royal palace in Portici, Southeast of Naples along the coast, in the region of Campania, Italy. Today it is the home of t ...

where the excavations from Pompeii and Herculaneum were exhibited, he visited the Greek temples in Paestum

Paestum ( , , ) was a major ancient Greek city on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea in Magna Graecia (southern Italy). The ruins of Paestum are famous for their three ancient Greek temples in the Doric order, dating from about 550 to 450 BC, whi ...

several times. While Tischbein stayed in Naples looking for commissions, Goethe went on to Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

with the German painter Christoph Heinrich Kniep. There he devoted himself intensively to the then largely unknown Greek ruins in Agrigento

Agrigento (; scn, Girgenti or ; grc, Ἀκράγας, translit=Akrágas; la, Agrigentum or ; ar, كركنت, Kirkant, or ''Jirjant'') is a city on the southern coast of Sicily, Italy and capital of the province of Agrigento. It was one o ...

. In Palermo, Goethe searched for what he called "Urpflanze", a plant that would be the archetype

The concept of an archetype (; ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main model that ...

of all plants.

In his journal, Goethe shows a marked interest in the geology of Europe's southern regions. He demonstrates a depth and breadth of knowledge in each subject. Most frequently, he pens descriptions of mineral and rock samples that he retrieves from the mountains, crags, and riverbeds of Italy. He also undertakes several dangerous hikes to the summit of Mount Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ; it, Vesuvio ; nap, 'O Vesuvio , also or ; la, Vesuvius , also , or ) is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of ...

, where he catalogues the nature and qualities of various lava flows and tephra

Tephra is fragmental material produced by a volcanic eruption regardless of composition, fragment size, or emplacement mechanism.

Volcanologists also refer to airborne fragments as pyroclasts. Once clasts have fallen to the ground, they re ...

. He is similarly adept at recognizing species of plant and flora, which stimulate thought and research into his botanical theories.

While more credibility can be attributed to his scientific investigations, Goethe maintains a thoughtful and admiring interest in art. Using Palladio and Johann Joachim Winkelmann as touchstones for his artistic growth, Goethe expands his scope of thought in regards to Classical concepts of beauty and the characteristics of good architecture. Indeed, in his letters he periodically comments on the growth and good that Rome has caused in him. The profusion of high-quality objects of art proves critical in his transformation during these two years away from his hometown in Germany.

Rome and Naples

Goethe stayed almost three months in

Goethe stayed almost three months in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, which he described as "the First City of the World". His company was a group of young German and Swiss painters lodging with Tischbein, Friedrich Bury

Friedrich (Fritz) Bury (12 March 1763 – 18 May 1823) was a German artist born in Hanau. He studied first under his father Jean Jacques Bury, who was a goldsmith and professor in the Academy of Design in Hanau, and then with Johann Heinrich Wi ...

, Johann Heinrich Meyer, Johann Heinrich Lips

Johann Heinrich Lips (29 April 1758, in Kloten – 5 May 1817, in Zürich) was a Swiss copper engraver; mostly of portraits.

Biography

His father was the village surgeon and barber. His Latin teacher, the local pastor, introduced him to Johann ...

and Johann Georg Schütz. He sketched and did watercolours, experimented with modeling a head of Hercules and even shortly toyed with the idea of turning from a writer into a painter when he took painting lessons from Jakob Philipp Hackert

Jacob Philipp Hackert (15 September 1737 – 28 April 1807) was a landscape painter from Brandenburg, who did most of his work in Italy.

Biography

Hackert was born in 1737 in Prenzlau in the Margraviate of Brandenburg (now in Germany). He t ...

in Naples. But he soon realized his limitations in this field. He visited famous sites, rewrote his play ''Iphigenia

In Greek mythology, Iphigenia (; grc, Ἰφιγένεια, , ) was a daughter of King Agamemnon and Queen Clytemnestra, and thus a princess of Mycenae.

In the story, Agamemnon offends the goddess Artemis on his way to the Trojan War by hunting ...

'', and thought about his ''Collected Works'', already in progress back home. He could look back now on what he called his ''" salto mortale"'' (somersault

A somersault (also ''flip'', ''heli'', and in gymnastics ''salto'') is an acrobatic exercise in which a person's body rotates 360° around a horizontal axis with the feet passing over the head. A somersault can be performed forwards, backwards ...

), his bid for freedom, and he had explained himself in letters to his mistress and friends. But he couldn't settle. Rome was full of remains, but too much was gone. "Architecture rises out of its grave like a ghost." All he could do was "revere in silence the noble existence of past epochs which have perished for ever." It is at this point, as Nicholas Boyle puts it clearly in the first volume of his biography, Goethe began to think of turning his "flight to Rome... into an Italian journey".

From February to May 1787 he was in Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. He climbed Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ; it, Vesuvio ; nap, 'O Vesuvio , also or ; la, Vesuvius , also , or ) is a somma- stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of ...

, visited Pompeii, found himself contrasting Neapolitan gaiety with Roman solemnity. He was amazed that people could actually live in the way he had only imagined living and in an emotional passage he wrote:

Naples is a paradise; everyone lives in a state of intoxicated self-forgetfulness, myself included. I seem to be a completely different person whom I hardly recognise. Yesterday I thought to myself: Either you were mad before, or you are mad now.and about the sights:

One may write or paint as much as one likes, but this place, the shore, the gulf, Vesuvius, the citadels, the villas, everything, defies description.

I can't begin to tell you of the glory of a night by full moon when we strolled through the streets and squares to the endless promenade of the Chiaia, and then walked up and down the seashore. I was quite overwhelmed by the feeling of infinite space. To be able to dream like this is certainly worth the trouble it took to get here.However, he does not indulge himself predominantly in literary reflections or thoughts on the classics of art. Instead, he observes his new surroundings closely. For example, he contradicts the German travel author Johann Jacob Volkmann who speaks of "thirty to forty thousand idlers" in Naples, by observing in detail what members of the lower classes deal with on a daily basis. He describes their diverse activities, including child labor, and sums up that he had noticed "a lot of ill-dressed people", but no unemployed ones. He expands observations of a year-round abundance of fruit, vegetables and fish into a historical comparison of the southern and northern peoples. The latter, due to climatic and agricultural conditions, were forced by nature in a completely different way to prepare for hard winters, which results in the “Nordic industry” being much more efficient; On the other hand, the Neapolitan poor understand at the same time “to enjoy the world at its best” – like all classes there “do not work in their own way just to live, but to enjoy, and that they even want to find happiness in their work". Basically, Goethe has a positive attitude towards the Italian mentality and art of living and hopes to be able to adopt some of them for himself and his future life in Weimar. Unlike in Rome, Goethe, the ennobled ducal minister, tried not to withdraw from socializing in Naples. Rather, passed around by the philosopher Prince

Gaetano Filangieri

Gaetano Filangieri (22 August 1753 – 21 July 1788) was an Italian jurist and philosopher.

Filangieri was born in San Sebastiano al Vesuvio, in the province of Naples, Italy. He was born the third son of a sibship of the noble family of Fila ...

, he allowed himself to be invited to aristocratic palaces and socialized with the British ambassador Sir William Hamilton and his wife Lady Emma. In some places Goethe also inserts anecdotes, for example about Filangieri's unconventional sister who was married to the old prince Filippo Fieschi Ravaschieri and enjoyed offending his clerical guests, as Goethe describes with delight. Or about the tyrannical governor of Messina, whose lunch table, filled with dozens of guests, is not allowed to start until soldiers have searched the whole city for Goethe, who had innocently skipped the meal for sightseeing not aware he had the place of honor next to the governor.

After returning to Rome from Sicily via Naples in June 1787, Goethe decided, instead of returning home to Weimar as planned, to stay in Rome for another winter, which turned out to be almost a whole year. He delayed his departure until after Easter the following year and did not leave until April 1788. Besides ''Iphigenia'', he also finished his play '' Egmont'' in September 1787.

Epigraph

Itinerary

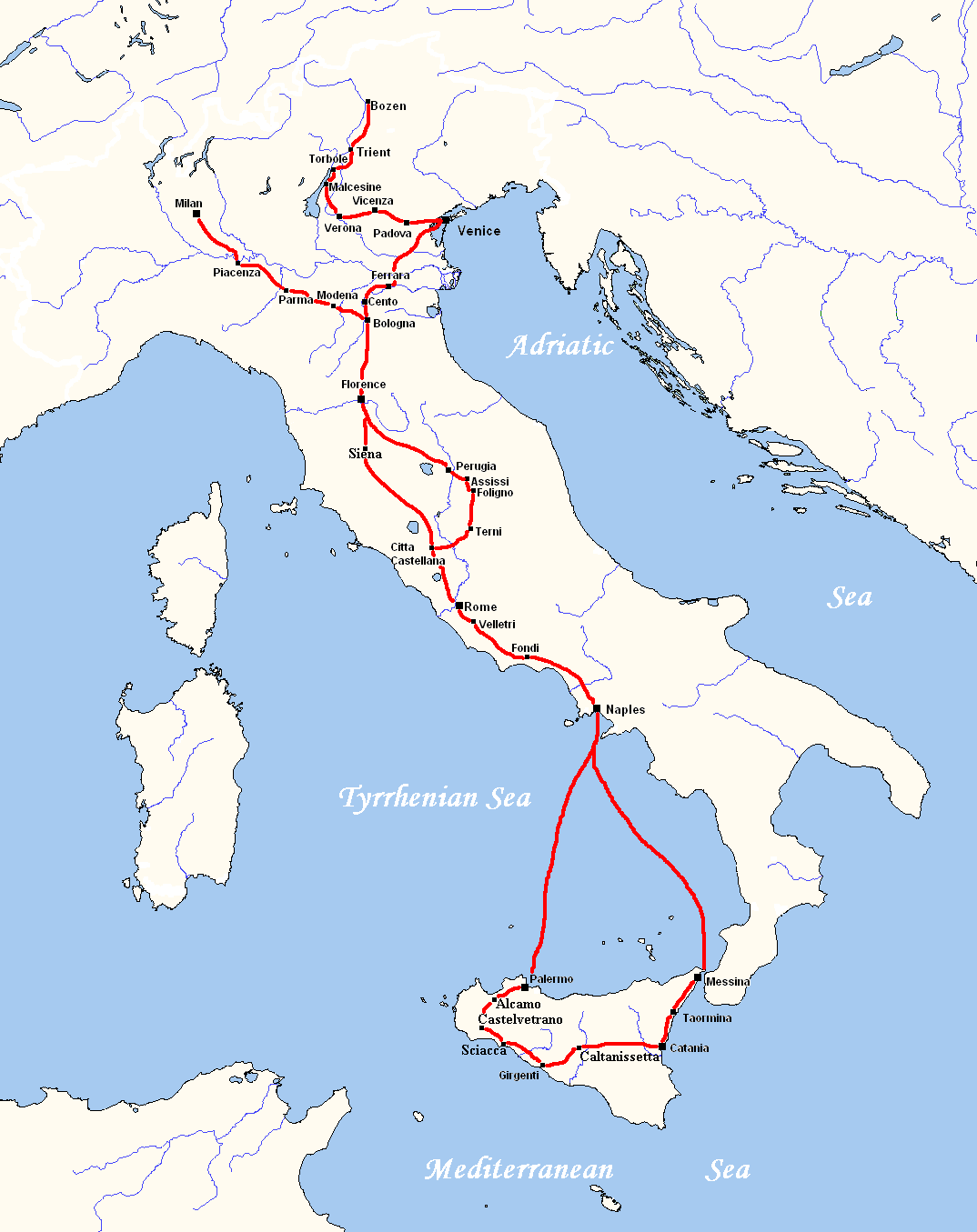

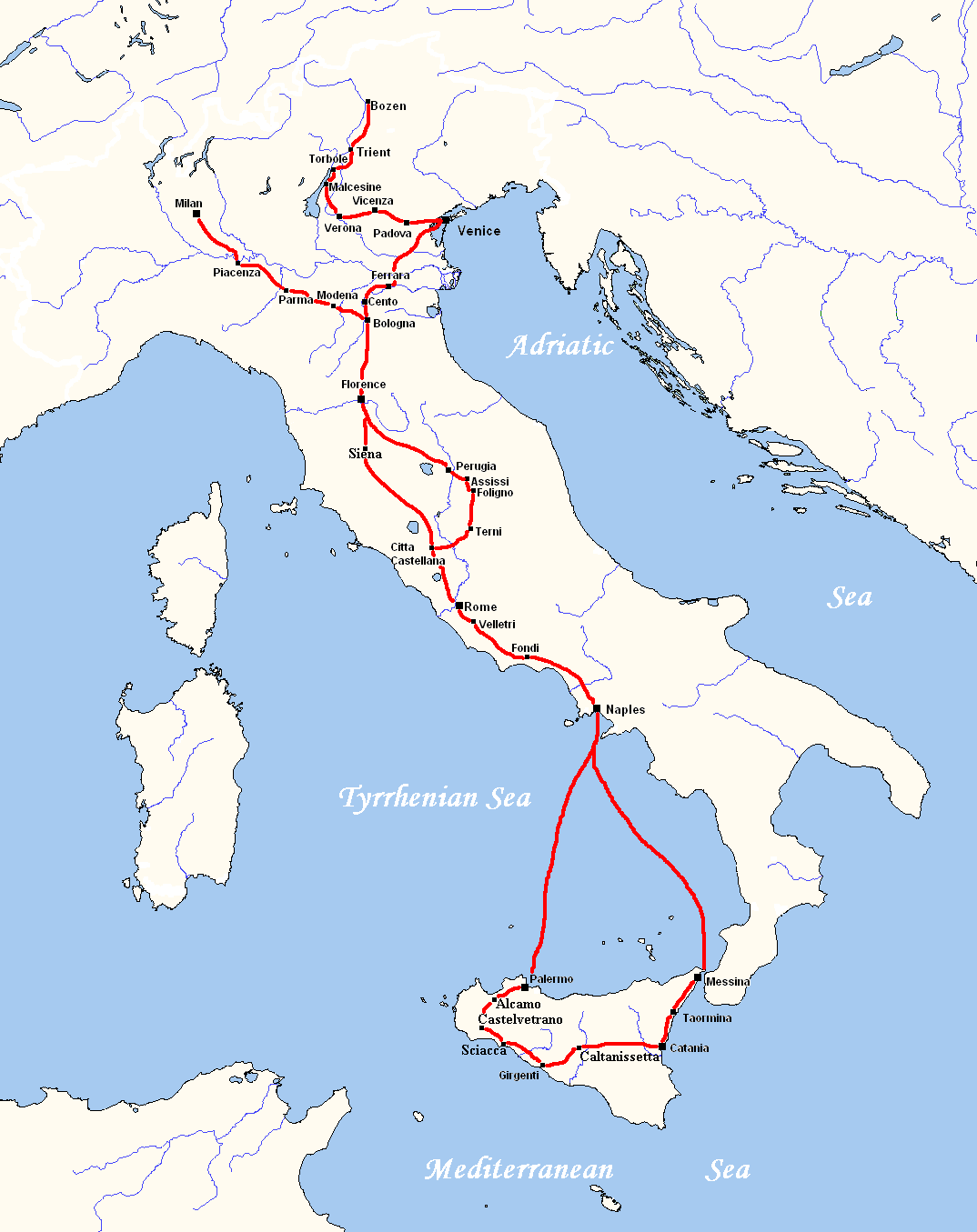

The ''Italian Journey'' is divided sequentially as follows:

:Part One

::*September 1786: from Karlsbad (now Karlovy Vary in the

The ''Italian Journey'' is divided sequentially as follows:

:Part One

::*September 1786: from Karlsbad (now Karlovy Vary in the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

) to the Brenner.

::*--, from the Brenner to Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

, via Bolzano

Bolzano ( or ; german: Bozen, (formerly ); bar, Bozn; lld, Balsan or ) is the capital city of the province of South Tyrol in northern Italy. With a population of 108,245, Bolzano is also by far the largest city in South Tyrol and the third la ...

, Trento

Trento ( or ; Ladin and lmo, Trent; german: Trient ; cim, Tria; , ), also anglicized as Trent, is a city on the Adige River in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol in Italy. It is the capital of the autonomous province of Trento. In the 16th ce ...

, Torbole, Malcesine

Malcesine is a ''comune'' (municipality) on the eastern shore of Lake Garda in the Province of Verona in the Italian region Veneto, located about northwest of Venice and about northwest of Verona.

Geography and divisions

The comune of Malcesine ...

.

::*--, from Verona to Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

, via Vicenza

Vicenza ( , ; ) is a city in northeastern Italy. It is in the Veneto region at the northern base of the ''Monte Berico'', where it straddles the Bacchiglione River. Vicenza is approximately west of Venice and east of Milan.

Vicenza is a thr ...

, Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

.

::*October 1786: Venice.

::*--, from Ferrara to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, via Cento

The Middle East Treaty Organization (METO), also known as the Baghdad Pact and subsequently known as the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), was a military alliance of the Cold War. It was formed in 24 February 1955 by Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Tur ...

, Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

, Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

, Perugia

Perugia (, , ; lat, Perusia) is the capital city of Umbria in central Italy, crossed by the River Tiber, and of the province of Perugia.

The city is located about north of Rome and southeast of Florence. It covers a high hilltop and pa ...

, Assisi, Foligno, Terni

Terni ( , ; lat, Interamna (Nahars)) is a city in the southern portion of the region of Umbria in central Italy. It is near the border with Lazio. The city is the capital of the province of Terni, located in the plain of the Nera river. It is ...

, Civita Castellana

Civita Castellana is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Viterbo, north of Rome.

Mount Soracte lies about to the south-east.

History

Civita Castellana was settled during the Iron Age by the Italic people of the Falisci, who called it "F ...

.

::*October 1786-February 1787: first Roman visit.

:Part Two

::*February–March 1787: Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, via Velletri

Velletri (; la, Velitrae; xvo, Velester) is an Italian ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Rome, approximately 40 km to the southeast of the city centre, located in the Alban Hills, in the region of Lazio, central Italy. Neighbouring comm ...

, Fondi

Fondi ( la, Fundi; Southern Laziale: ''Fùnn'') is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Latina, Lazio, central Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. I ...

.

::*March–May 1787: Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, including Palermo, Alcamo

Alcamo (; scn, Àrcamu, italic=no) is the fourth-largest town and communes of Italy, commune of the Province of Trapani, Sicily, with a population of 44.925 inhabitants. It is on the borderline with the Metropolitan City of Palermo at a distan ...

, Castelvetrano

Castelvetrano ( scn, Castiḍḍuvitranu) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Trapani, Sicily, southern Italy. The archeological site of Selinunte is located within the municipal territory.

The municipality borders with Campobello d ...

, Sciacca

Sciacca (; Greek: ; Latin: Thermae Selinuntinae, Thermae Selinuntiae, Thermae, Aquae Labrodes and Aquae Labodes) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Agrigento on the southwestern coast of Sicily, southern Italy. It has views of the Medit ...

, Agrigento

Agrigento (; scn, Girgenti or ; grc, Ἀκράγας, translit=Akrágas; la, Agrigentum or ; ar, كركنت, Kirkant, or ''Jirjant'') is a city on the southern coast of Sicily, Italy and capital of the province of Agrigento. It was one o ...

(Girgenti), Caltanisetta, Catania, Taormina

Taormina ( , , also , ; scn, Taurmina) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Messina, on the east coast of the island of Sicily, Italy. Taormina has been a tourist destination since the 19th century. Its beaches on ...

, Messina.

::*May–June 1787: Naples.

:Part Three: June 1787-April 1788: second Roman visit.

Gallery, Goethe at Malcesine

Scaliger

The Della Scala family, whose members were known as Scaligeri () or Scaligers (; from the Latinized ''de Scalis''), was the ruling family of Verona and mainland Veneto (except for Venice) from 1262 to 1387, for a total of 125 years.

History

Wh ...

Castle in Malcesine

Malcesine is a ''comune'' (municipality) on the eastern shore of Lake Garda in the Province of Verona in the Italian region Veneto, located about northwest of Venice and about northwest of Verona.

Geography and divisions

The comune of Malcesine ...

, a place he visited in 1786, during his Italian journey.

File:Malcesine - memorial tablet.jpg, "At this place J. W. Goethe drew the castle on September 14, 1786": Plaque in the Via Castello, Malcesine, where Goethe was drawing the castle.

File:Malcesine - Castle - Goethe's direction of view.jpg, Goethe's view of Castello Scaligero, when interrupted as he described in ''Italian Journey'' (click on image for quotation).

File:Goethe Malcesine.jpg, Goethe's drawing of Castello Scaligero, torn in the incident described in ''Italian Journey''.

Reception

The reception of Goethe's Italian journey did not begin with the much later publication of his travel diaries from 1813 to 1817. It begins on the journey itself, especially since Goethe tried to let his friends in Weimar share his experiences by means of numerous letters, not least Duke Carl August, who ultimately continued to pay him his salary as a privy councilor and thus made the journey economically possible in the first place. Goethe repeatedly emphasized in his letters how much the artistic impressions of Italy inspired his own artistic work, repeatedly spoke of a "rebirth", a "new youth" and tried to justify the increasing length of his absence. He regularly sends home newly-made manuscripts to demonstrate his continued production. The Italian journey was also the subject of correspondence with friends in Italy after Goethe's return to Weimar (published in 1890 byOtto Harnack

Rudolf Gottfried Otto Harnack (23 November 1857, in Erlangen – 22 March 1914, near Besigheim) was a German literary historian, best known for his writings on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

He studied history and philology at the universities of ...

). The journey to Italy by Duchess Anna Amalia from 1788 to 1790 was also inspired by Goethe's letters.

One result of his trip was that after his return to Weimar he separated his poetic from his political existence by asking the duke to release him from many of his previous duties so that he could do “what no one but I can do, and let other people do the rest".

The poet himself remained inspired by his travel impressions throughout his life. Goethe's house in Weimar is filled with antique works of art and pictures that allude to Italy, as was his parents' house in Frankfurt, since his father

The poet himself remained inspired by his travel impressions throughout his life. Goethe's house in Weimar is filled with antique works of art and pictures that allude to Italy, as was his parents' house in Frankfurt, since his father Johann Caspar Goethe

Johann Caspar Goethe (29 July 1710 – 25 May 1782) was a wealthy German jurist and royal councillor to the Kaiser of the Holy Roman Empire. His son, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, is considered one of the greatest German poets and authors of all ti ...

had brought numerous copper engravings back from a trip to Italy between 1740 and 1741; the father had also written a travel book (in Italian). The Weimar staircase is modeled on Italian palazzi with antique plaster casts and reliefs, as well as charcoal drawings of the Elgin Marbles

The Elgin Marbles (), also known as the Parthenon Marbles ( el, Γλυπτά του Παρθενώνα, lit. "sculptures of the Parthenon"), are a collection of Classical Greece, Classical Greek marble sculptures made under the supervision of th ...

. The Park an der Ilm

The Park an der Ilm (Park on the Ilm, short ''Ilmpark'') is a large ''Landscape architecture, Landschaftspark'' (landscaped park) in Weimar, Thuringia. It was created in the 18th century, influenced by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and has not been c ...

is filled with a staffage building based on a Roman country house drawn by Goethe, a pompeian bench or the cast of a sacrificial altar from Herculaneum.

What does not appear in the book are the numerous erotic experiences that Goethe was able to have in Italy, for example with his Roman lover Faustina, some of which were even homoerotic. However, a few weeks after his return, on July 12, 1788, in Weimar, Goethe made the acquaintance of the 23-year-old milliner Christiane Vulpius, whom he made his lover, and soon afterwards his partner (and eventually his wife). However, his '' Roman Elegies'' with numerous erotic allusions were written at that time.

References

External links

Italienische Reise, vol. 1

Italienische Reise, vol. 2

Interactive Map with spots of Goethe's "Italienische Reise" with text and images.

ref>

Wiedergeburt in Italien

*

Scarabocchio

' (2008), a novel by

Grace Andreacchi

Grace Andreacchi (born December 3, 1954) is an American-born author known for her blend of poetic language and modernism with a post-modernist sensibility. Andreacchi is active as a novelist, poet and playwright.

Biography

Grace Andreacchi wa ...

, based on Goethe's ''Italian Journey''.

Goethe, his love rivals and evidence of a generalized anxiety disorder.

Humane Medicine, 2008. An issue by Giuseppe Paolo Mazzarello, MD. {{Authority control 1816 non-fiction books 1817 non-fiction books Travel books Works by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Books about Italy German non-fiction books