Italian nationalism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Italian nationalism is a movement which believes that the

Italian nationalism is a movement which believes that the

The origins of Italian nationalism have been traced to

The origins of Italian nationalism have been traced to  Paoli was sympathetic to Italian culture and regarded his own native language as an Italian dialect (Corsican is an Italo-Dalmatian tongue closely related to Tuscan. He was considered by

Paoli was sympathetic to Italian culture and regarded his own native language as an Italian dialect (Corsican is an Italo-Dalmatian tongue closely related to Tuscan. He was considered by

The initial important figure in the development of Italian nationalism was Giuseppe Mazzini, who became a nationalist in the 1820s.Vincent P. Pecora. ''Nations and identities: classic readings''. Oxford, England, UK; Malden, Massachusetts, USA: Blackwell Publishers, Inc, 2001. Pp. 156. In his political career, Mazzini held as objectives the liberation of Italy from the Austrian occupation, indirect control by Austria, princely despotism, aristocratic privilege, and clerical authority.John Gooch. ''The Unification of Italy''. Taylor & Francis e-library, 2001. Pp. 5. Mazzini was captivated by

The initial important figure in the development of Italian nationalism was Giuseppe Mazzini, who became a nationalist in the 1820s.Vincent P. Pecora. ''Nations and identities: classic readings''. Oxford, England, UK; Malden, Massachusetts, USA: Blackwell Publishers, Inc, 2001. Pp. 156. In his political career, Mazzini held as objectives the liberation of Italy from the Austrian occupation, indirect control by Austria, princely despotism, aristocratic privilege, and clerical authority.John Gooch. ''The Unification of Italy''. Taylor & Francis e-library, 2001. Pp. 5. Mazzini was captivated by

Supporters of Italian nationalism ranged from across the political spectrum: it appealed to both

Supporters of Italian nationalism ranged from across the political spectrum: it appealed to both

After the unification of Italy was completed in 1870, the Italian government faced domestic political paralysis and internal tensions, resulting in it resorting to embarking on a colonial policy to divert the Italian public's attention from internal issues.

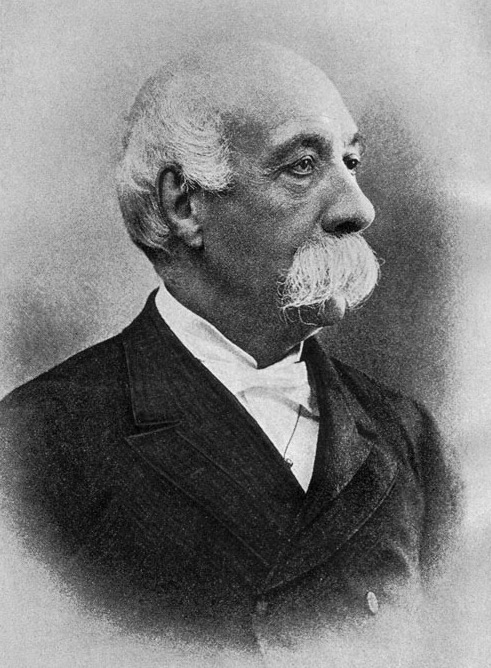

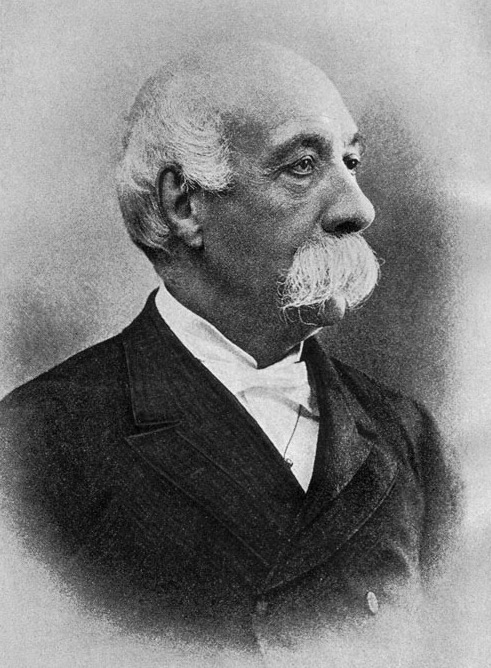

In these years, one of the most prominent political figures was Francesco Crispi, whose actions as prime minister were characterised by a nationalism that often appeared as a form of obsession for the national unity and defence from hostile foreign countries.Nation-building in 19th-century Italy: the case of Francesco Crispi

After the unification of Italy was completed in 1870, the Italian government faced domestic political paralysis and internal tensions, resulting in it resorting to embarking on a colonial policy to divert the Italian public's attention from internal issues.

In these years, one of the most prominent political figures was Francesco Crispi, whose actions as prime minister were characterised by a nationalism that often appeared as a form of obsession for the national unity and defence from hostile foreign countries.Nation-building in 19th-century Italy: the case of Francesco Crispi

Christopher Duggan, History Today, February 1, 2002 Italy managed to colonize the East African coast of At the outbreak of

At the outbreak of  In particular, Italian nationalists were enraged by the Allies denying Italy the right to annex

In particular, Italian nationalists were enraged by the Allies denying Italy the right to annex

After the fall of Fascism and following the birth of the

After the fall of Fascism and following the birth of the  In 1995 the MSI developed in the

In 1995 the MSI developed in the

File:Flag of Italy.svg, Civil flag of Italy, originally designed in 1797. A symbol of the Italian nation since the early-19th century and symbol of the Italian Republic since 1946.

File:Flag of Italy (1861-1946).svg, Civil flag of the Kingdom of Italy from 1861 to 1946. Presently used by Italian monarchists.

File:War_flag_of_the_Italian_Social_Republic.svg, War flag of the Italian Social Republic, the incarnation of Fascist Italy from 1943 to 1945 after the Fascist regime in the Kingdom of Italy was dismantled in 1943. It is a prominent symbol used by Italian neo-fascists.

in JSTOR

* Drake, Richard. "The Theory and Practice of Italian Nationalism, 1900-1906." ''Journal of Modern History'' (1981): 213–241

in JSTOR

* Marsella, Mauro. "Enrico Corradini's Italian nationalism: the ‘right wing’ of the fascist synthesis." ''Journal of Political Ideologies'' 9.2 (2004): 203-224. * * Noether, Emiliana Pasca. ''Seeds of Italian nationalism, 1700-1815'' (Columbia University Press, 1951). * Noether, Emiliana P. "The intellectual dimension of italian nationalism: An overview." ''History of European Ideas'' 16.4-6 (1993): 779–784. * Patriarca, Silvana, and Lucy Riall, eds., ''The Risorgimento Revisited: Nationalism and Culture in Nineteenth-century Italy'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011) * Salvadori, Massimo. "Nationalism in Modern Italy-1915 and after." ''Orbis-A Journal of World Affairs'' 10.4 (1967): 1157–1175. * Sluga, Glenda A. "The Risiera di San Sabba: Fascism, anti‐Fascism and Italian nationalism." ''Journal of Modern Italian Studies'' 1.3 (1996): 401–412. * Tambini, Damian. ''Nationalism in Italian politics: The stories of the Northern League, 1980-2000'' (Routledge, 2012). {{Authority control History of Europe Political history of Italy Italian culture Italian unification

Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

are a nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by those ...

with a single homogeneous identity, and therefrom seeks to promote the cultural unity of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

as a country. From an Italian nationalist perspective, Italianness is defined as claiming cultural and ethnic descent from the Latins

The Latins were originally an Italic tribe in ancient central Italy from Latium. As Roman power and colonization spread Latin culture during the Roman Republic.

Latins culturally "Romanized" or "Latinized" the rest of Italy, and the word Latin ...

, an Italic tribe

The Italic peoples were an ethnolinguistic group identified by their use of Italic languages, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

The Italic peoples are descended from the Indo-European speaking peoples who inhabited Italy from at lea ...

which originally dwelt in Latium

Latium ( , ; ) is the region of central western Italy in which the city of Rome was founded and grew to be the capital city of the Roman Empire.

Definition

Latium was originally a small triangle of fertile, volcanic soil (Old Latium) on whi ...

and came to dominate the Italian peninsula and much of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. Because of that, Italian nationalism has also historically adhered to imperialist theories.Aaron Gillette. ''Racial theories in fascist Italy''. 2nd edition. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law, and ...

, 2003. Pp. 17. The romantic (or soft) version of such views is known as Italian patriotism, while their integral (or hard) version is known as Italian fascism.

Italian nationalism is often thought to trace its origins to the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

,Trafford R. Cole. ''Italian Genealogical Records: How to Use Italian Civil, Ecclesiastical & Other Records in Family History Research''. Salt Lake City, Utah, USA: Ancestry Incorporated, 1995. Pp. 15. but only arose as a political force in the 1830s under the leadership of Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, , ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the in ...

. It served as a cause for ''Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

'' in the 1860s to 1870s. Italian nationalism became strong again in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

with Italian irredentist

Italian irredentism ( it, irredentismo italiano) was a nationalist movement during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Italy with irredentist goals which promoted the unification of geographic areas in which indigenous peoples ...

claims to territories held by Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, and during the era of Italian Fascism.

History

Renaissance to 19th century

The origins of Italian nationalism have been traced to

The origins of Italian nationalism have been traced to the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

where Italy led a European revival of classical Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

style of culture, philosophy, and art. In 1344 Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited w ...

wrote the famous patriotic canzone

Literally "song" in Italian, a ''canzone'' (, plural: ''canzoni''; cognate with English ''to chant'') is an Italian or Provençal song or ballad. It is also used to describe a type of lyric which resembles a madrigal. Sometimes a composition w ...

“Italia mia” (Rime 128), in which he railed against the warring petty lords of Italy for having yielded the country up to barbarian German fury (ʻla tedesca rabbia’, line 35) and called for peace and unification. Around the same time, Cola di Rienzo

Nicola Gabrini (1313 8 October 1354), commonly known as Cola di Rienzo () or Rienzi, was an Italian politician and leader, who styled himself as the "tribune of the Roman people".

Having advocated for the abolition of temporal papal power a ...

attempted to unite the whole of Italy under the hegemony of Rome. In 1347 he assumed the title of “Libertatis, Pacis Iustitiaeque Tribunus, et Sacrae Romanae Rei Publicae Liberator.” Petrarch hailed him in his famous song “Spirto gentil che quelle membra reggi” as the reincarnation of the classical spirit.

In 1454, representatives from all the regional states of Italy met in Lodi to sign the treaty known as the peace of Lodi

Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in the absence of hostility and violence. In a social sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such as war) and freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups. ...

, by which they intended to pursue Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

. The status quo

is a Latin phrase meaning the existing state of affairs, particularly with regard to social, political, religious or military issues. In the sociological sense, the ''status quo'' refers to the current state of social structure and/or values. W ...

established at Lodi lasted until 1494, when French troops intruded into Italian affairs under Charles VIII, initiating the Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts covering the period 1494 to 1559, fought mostly in the Italian peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and the Mediterranean Sea. The pr ...

.

The Renaissance-era diplomat and political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli ( , , ; 3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527), occasionally rendered in English as Nicholas Machiavel ( , ; see below), was an Italian diplomat, author, philosopher and historian who lived during the Renaissance. ...

, in his work ''The Prince

''The Prince'' ( it, Il Principe ; la, De Principatibus) is a 16th-century political treatise written by Italian diplomat and political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli as an instruction guide for new princes and royals. The general theme of ''The ...

'' (1532), appealing to Italian patriotism urged Italians "to seize Italy and free her from the Barbarian

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either Civilization, uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by som ...

s", by which he referred to the foreign powers occupying the Italian peninsula. Machiavelli quoted four verses from Petrarch's “Italia mia”, which looked forward to a political leader who would unite Italy.

During the Italian Wars Pope Julius II

Pope Julius II ( la, Iulius II; it, Giulio II; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope or th ...

(1503–1513) made every effort to forge Italian alliances to drive the enemy – in his time the French – out of the country. And although his rallying cry ''fuori i barbari'' (‘Put the barbarians out!’) is probably apocryphal, it very neatly sums up the feeling of many Italians.

In 1559 the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis

Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in the absence of hostility and violence. In a social sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such as war) and freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups. ...

marked the end of Italian liberty and the beginning of a period of uncontested Spanish hegemony in Italy. During the long-lasting period of Spanish domination a vitriolic anti-Spanish polemic became widespread throughout Italy. Trajano Boccalini

Trajano Boccalini (155616 November 1613) was an Italian satirist.

Biography

Boccalini was born in Loreto, the son of an architect, he himself adopted that profession, and it appears that he commenced late in life to apply to literary pursuits ...

wrote many anti-Spanish pamphlets

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a hard cover or binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' or it may consist of a ...

, such as ''Pietra del paragone politico'' (Politick Touchstone), published after his death in 1615. Followers of Boccalini published similar anti-Spanish pamphlets in the same period, such as ''Esequie delle reputazione di Spagna'', printed in 1615, in which the corpse of the reputation of Spain is dissected by famous anatomists.

Modern historians disagree on the strength of “Italianità” (Italian national identity) in the early modern period. By contrast, Spanish diplomats in Italy at the time were all too certain that Italians shared a common bond of resentment against the imperial power of Spain.

Charles Emmanuel I

Charles Emmanuel I ( it, Carlo Emanuele di Savoia; 12 January 1562 – 26 July 1630), known as the Great, was the Duke of Savoy from 1580 to 1630. He was nicknamed (, in context "the Hot-Headed") for his rashness and military aggression.

Being ...

's expansionist policy ignited Italian nationalism and patriotism. In 1614 Alessandro Tassoni

Alessandro Tassoni (28 September 156525 April 1635) was an Italian poet and writer, from Modena, best known as the author of the mock-heroic poem ''La secchia rapita'' (''The Rape of the Pail'', or ''The stolen bucket'').

Life

He was born in M ...

published in quick succession two anonymous ''Filippiche'' addressed to the Italian nobility, exhorting the nobles to discard their lethargy, unite and instead of fighting each other, join Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

in ridding Italy of Spanish hegemony.

At about the same time that Tassoni was inspired to write the ''Filippiche'', Fulvio Testi, a young poet at the court of the duke of Este, published a collection of poems dedicated to Charles Emmanuel. Not all the poems were of a patriotic nature, but those that were clearly revealed the feelings Charles Emmanuel had stirred in freedom-loving Italians. Testi followed this up, in 1617, with the ''Pianto d'Italia'', where Italy calls for a war of national independence, in which the Duke of Savoy is to be the leader.

More than fifty years later Vittorio Siri still reminisced that “all Italy broke forth with pen and tongue in praises and panegyrics at the name of Carlo Emanuele, and in demonstrations of joy and applause that he had revived . . . the ancient Latin valor, wishing that he . . . ightone day become the redeemer of Italy's freedom and the restorer of its greatness.”

The failure of Charles Emmanuel's expansive foreign policy caused a widespread crisis among Italian nationalists.

In Vincenzo da Filicaja

Vincenzo da Filicaja (30 December 164224 September 1707) was a Tuscan poet and politician. His poetry was compared to that of Petrarch, and his association with the Accademia della Crusca gave him access to royal patronage. He served as governor ...

's late seventeenth-century sonnet “Italia, Italia O tu, cui feo la sorte” (Italy, Italy, O you, to whom fate has given) the 'unlucky gift of beauty' was the reason why Italy, 'the slave of friend and foe', had repeatedly been conquered, sacked and exploited throughout history. Filicaia's sonnet was well known, along with Petrarch's ''Italia mia'', as one of the great Italian patriotic lyrics. It appeared in Sismondi's ''De la littérature du midi'' (where it is praised as 'the most celebrated specimen which the Italian literature of the seventeenth century affords') and was frequently translated into English.

In 1713 the Dukes of Savoy, who traditionally possessed the title of an imperial vicar

An imperial vicar (german: Reichsvikar) was a prince charged with administering all or part of the Holy Roman Empire on behalf of the emperor. Later, an imperial vicar was invariably one of two princes charged by the Golden Bull with administering ...

of Italy, obtained royal dignity, securing their pre-eminence among the Italian princes.

When France started to annex Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

in the late 18th century (and then incorporated during Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's empire the regions of Piemonte

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, Liguria

Liguria (; lij, Ligûria ; french: Ligurie) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is ...

, Toscana

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

and Lazio

it, Laziale

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

), the first movements to defend Italy's existence aroused with Paoli revolt and were later followed by the birth of the so-called "irredentism".

Paoli was sympathetic to Italian culture and regarded his own native language as an Italian dialect (Corsican is an Italo-Dalmatian tongue closely related to Tuscan. He was considered by

Paoli was sympathetic to Italian culture and regarded his own native language as an Italian dialect (Corsican is an Italo-Dalmatian tongue closely related to Tuscan. He was considered by Niccolò Tommaseo

Niccolò Tommaseo (; 9 October 1802 – 1 May 1874) was a Dalmatian linguist, journalist and essayist, the editor of a ''Dizionario della Lingua Italiana'' in eight volumes (1861–74), of a dictionary of synonyms (1830) and other works. He is ...

, who collected his ''Lettere'' (Letters), as one of the precursors of the Italian irredentism

Italian irredentism ( it, irredentismo italiano) was a nationalist movement during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Italy with irredentist goals which promoted the unification of geographic areas in which indigenous peoples ...

. The so-called ''Babbu di a Patria'' ("Father of the fatherland"), as Pasquale Paoli was nicknamed by the Corsican Italians

Italian irredentism in Corsica was a cultural and historical movement promoted by Italians and by people from Corsica who identified themselves as part of Italy rather than France, and promoted the Italian annexation of the island.

History

Cors ...

, wrote in his Letters the following appeal in 1768 against the French:

''We are Corsicans by birth and sentiment, but first of all we feel Italian by language, origins, customs, traditions; and Italians are all brothers and united in the face of history and in the face of God ... As Corsicans we wish to be neither slaves nor "rebels" and as Italians we have the right to deal as equals with the other Italian brothers ... Either we shall be free or we shall be nothing... Either we shall win or we shall die, weapons in hand ... The war against France is right and holy as the name of God is holy and right, and here on our mountains will appear for Italy the sun of liberty....''Tommaseo. "Lettere di Pasquale de Paoli"

1830s to 1848

The initial important figure in the development of Italian nationalism was Giuseppe Mazzini, who became a nationalist in the 1820s.Vincent P. Pecora. ''Nations and identities: classic readings''. Oxford, England, UK; Malden, Massachusetts, USA: Blackwell Publishers, Inc, 2001. Pp. 156. In his political career, Mazzini held as objectives the liberation of Italy from the Austrian occupation, indirect control by Austria, princely despotism, aristocratic privilege, and clerical authority.John Gooch. ''The Unification of Italy''. Taylor & Francis e-library, 2001. Pp. 5. Mazzini was captivated by

The initial important figure in the development of Italian nationalism was Giuseppe Mazzini, who became a nationalist in the 1820s.Vincent P. Pecora. ''Nations and identities: classic readings''. Oxford, England, UK; Malden, Massachusetts, USA: Blackwell Publishers, Inc, 2001. Pp. 156. In his political career, Mazzini held as objectives the liberation of Italy from the Austrian occupation, indirect control by Austria, princely despotism, aristocratic privilege, and clerical authority.John Gooch. ''The Unification of Italy''. Taylor & Francis e-library, 2001. Pp. 5. Mazzini was captivated by ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 B ...

that he considered the "temple of human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

ity" and sought to establish a united Italy as a "Third Rome

The continuation, succession and revival of the Roman Empire is a running theme of the history of Europe and the Mediterranean Basin. It reflects the lasting memories of power and prestige associated with the Roman Empire itself.

Several polit ...

" that emphasized Roman spiritual values that Italian nationalists claimed were preserved by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Mazzini and Italian nationalists in general promoted the concept of ''Romanità

''Romanitas'' is the collection of political and cultural concepts and practices by which the Romans defined themselves. It is a Latin word, first coined in the third century AD, meaning "Roman-ness" and has been used by modern historians as shor ...

'' (the Romanness), which claimed that Roman culture made invaluable contributions to the Italian and Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

Ci ...

. Since the 1820s, Mazzini supported a revolution to create a utopia of an ideal Italian republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

based in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. Mazzini formed revolutionary patriotic Young Italy

Young Italy ( it, La Giovine Italia) was an Italian political movement founded in 1831 by Giuseppe Mazzini. After a few months of leaving Italy, in June 1831, Mazzini wrote a letter to King Charles Albert of Sardinia, in which he asked him to uni ...

society in 1832. Upon Young Italy breaking apart in the 1830s, Mazzini reconstituted it in 1839 with the intention to gain the support of workers' groups. However, at the time Mazzini was hostile to socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

due to his belief that all classes needed to be united in the cause of creating a united Italy rather than divided against each other.John Gooch. ''The Unification of Italy''. Taylor & Francis e-library, 2001. Pp. 6.

Vincenzo Gioberti

Vincenzo Gioberti (; 5 April 180126 October 1852) was an Italian Catholic priest, philosopher, publicist and politician who served as the Prime Minister of Sardinia from 1848 to 1849. He was a prominent spokesman for liberal Catholicism.

Bio ...

in 1843 in his book ''On the Civil and Moral Primacy of the Italians'', advocated a federal state of Italy led by the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

.

Camillo Benso

Camillo Paolo Filippo Giulio Benso, Count of Cavour, Isolabella and Leri (, 10 August 1810 – 6 June 1861), generally known as Cavour ( , ), was an Italian politician, businessman, economist and noble, and a leading figure in the movement towa ...

, the future Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

and afterwards the Kingdom of Italy, worked as an editor for the nationalist Italian newspaper ''Il Risorgimento'' in the 1840s.Lucy Riall. ''The Italian Risorgimento: State, society and national unification''. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 1994. Pp. 69. Cavour was a clear example of civic nationalism

Civic nationalism, also known as liberal nationalism, is a form of nationalism identified by political philosophers who believe in an inclusive form of nationalism that adheres to traditional liberal values of freedom, tolerance, equality, in ...

with a high consideration for values including freedom

Freedom is understood as either having the ability to act or change without constraint or to possess the power and resources to fulfill one's purposes unhindered. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving on ...

, tolerance, equality

Equality may refer to:

Society

* Political equality, in which all members of a society are of equal standing

** Consociationalism, in which an ethnically, religiously, or linguistically divided state functions by cooperation of each group's elit ...

, and individual rights

Group rights, also known as collective rights, are rights held by a group ''wikt:qua, qua'' a group rather than individually by its members; in contrast, individual rights are rights held by Individuality, individual people; even if they are grou ...

compatible with a sober nationalism.

Economic nationalism

Economic nationalism, also called economic patriotism and economic populism, is an ideology that favors state interventionism over other market mechanisms, with policies such as domestic control of the economy, labor, and capital formation, incl ...

influenced businessmen and government authorities to promote a united Italy. Prior to unification, tariff walls held between the Italian states and the disorganized railway system prevented economic development of the peninsula. Prior to the revolutions of 1848, Carlo Cattaneo advocated an economic federation of Italy.

Revolutions of 1848 to ''Risorgimento'' (1859 to 1870)

Supporters of Italian nationalism ranged from across the political spectrum: it appealed to both

Supporters of Italian nationalism ranged from across the political spectrum: it appealed to both conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

and liberals. The Revolutions of 1848 resulted in a major development of the Italian nationalist movement. Liberalization of press laws in Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

allowed nationalist activity to flourish.

Following the Revolutions of 1848 and the liberalization of press laws, the Italian nationalist organization, called the Italian National Society, was created in 1857 by Daniele Manin

Daniele Manin (13 May 180422 September 1857) was an Italian patriot, statesman and leader of the Risorgimento in Venice. Many Italian historians consider him to be an important figure in Italian unification.

Early and family life

left, House i ...

and Giorgio Pallevicino. The National Society was created to promote and spread nationalism to political moderates in Piedmont and raised money, held public meetings, and produced newspapers. The National Society helped to establish a base for Italian nationalism amongst the educated middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

. By 1860, the National Society influenced dominant liberal circles in Italy and won over middle class support for the union of Piedmont and Lombardy

Lombardy ( it, Lombardia, Lombard language, Lombard: ''Lombardia'' or ''Lumbardia' '') is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in the northern-central part of the country and has a population of about 10 ...

.

The statesman Daniele Manin

Daniele Manin (13 May 180422 September 1857) was an Italian patriot, statesman and leader of the Risorgimento in Venice. Many Italian historians consider him to be an important figure in Italian unification.

Early and family life

left, House i ...

seems to have believed in Italian unification years before Camillo Benso of Cavour, who actually unified the country with Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

through diplomatic and military actions. During the 1856 Congress of Paris

The Congress of Paris is the name for a series of diplomatic meetings held in 1856 in Paris, France, to negotiate peace between the warring powers in the Crimean War that had started almost three years earlier."Paris, Treaty of (1856)". The New E ...

, Manin talked with Cavour about several plans and strategies to achieve the unification of Italy

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century Political movement, political and social movement that resulted in the Merger (politics), consolidation of List of historic stat ...

; Cavour clearly considered those plans vain things, and after the meeting wrote that Manin had talked about "''l'unità d'Italia ed altre corbellerie''" ("the unity of Italy and other nonsense").

The Risorgimento was an ideological movement that helped incite the feelings of brotherhood and nationalism in the imagined Italian community, which called for the unification of Italy and the pushing out of foreign powers. Literature, music, and other outlets of expression frequently alluded back to the glorious past of Rome and the miraculous feats their ancestors had accomplished in defending their homeland and kicking out the foreign occupants.

Post-''Risorgimento'', World War I and aftermath (1870 to 1922)

After the unification of Italy was completed in 1870, the Italian government faced domestic political paralysis and internal tensions, resulting in it resorting to embarking on a colonial policy to divert the Italian public's attention from internal issues.

In these years, one of the most prominent political figures was Francesco Crispi, whose actions as prime minister were characterised by a nationalism that often appeared as a form of obsession for the national unity and defence from hostile foreign countries.Nation-building in 19th-century Italy: the case of Francesco Crispi

After the unification of Italy was completed in 1870, the Italian government faced domestic political paralysis and internal tensions, resulting in it resorting to embarking on a colonial policy to divert the Italian public's attention from internal issues.

In these years, one of the most prominent political figures was Francesco Crispi, whose actions as prime minister were characterised by a nationalism that often appeared as a form of obsession for the national unity and defence from hostile foreign countries.Nation-building in 19th-century Italy: the case of Francesco CrispiChristopher Duggan, History Today, February 1, 2002 Italy managed to colonize the East African coast of

Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia ...

and Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

, but failed to conquer Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

with 15,000 Italians dying in the war and being forced to retreat. Then, Italy waged war with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

from 1911 to 1912 and gained Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

and the Dodecanese Islands

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

from Turkey. However, these attempts to gain popular support from the public failed, and rebellions and violent protests became so intense that many observers believed that the young Kingdom of Italy would not survive.

Tired of the internal conflicts in Italy, a movement of bourgeois intellectuals led by Gabriele d'Annunzio, Gaetano Mosca, and Vilfredo Pareto

Vilfredo Federico Damaso Pareto ( , , , ; born Wilfried Fritz Pareto; 15 July 1848 – 19 August 1923) was an Italian polymath (civil engineer, sociologist, economist, political scientist, and philosopher). He made several important contribut ...

declared war on the parliamentary system, and their position gained respect among Italians. D'Annunzio called upon young Italians to seek fulfillment in violent action and put an end to the politically maneuvering parliamentary government. The Italian Nationalist Association

The Italian Nationalist Association (''Associazione Nazionalista Italiana'', ANI) was Italy's first nationalist political movement founded in 1910, under the influence of Italian nationalists such as Enrico Corradini and Giovanni Papini. Upon it ...

(''ANI'') was founded in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

in 1910 by the jingoist nationalist Enrico Corradini

Enrico Corradini (20 July 1865 – 10 December 1931) was an Italian novelist, essayist, journalist and nationalist political figure.

Biography

Corradini was born near Montelupo Fiorentino, Tuscany.

A follower of Gabriele D'Annunzio, he founded ...

who emphasized the need for martial heroism, of total sacrifice of individualism and equality to one's nation, the need of discipline and obedience in society, the grandeur and power of ancient Rome, and the need for people to live dangerously. Corradini's ANI's extremist appeals were enthusiastically supported by many Italians.

At the outbreak of

At the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1914, Italy initially maintained neutrality, despite its official alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary since 1882 on the grounds that Germany and Austria-Hungary were waging an aggressive war that it refused to take part in. In 1915, Italy eventually decided to enter the war on the British and French side against Austria-Hungary and Germany.

Nationalist pride soared in Italy after the end of hostilities in November 1918, with the victory of Italy and Allied forces over Austria-Hungary and the seizure by Italy of former Austro-Hungarian territories. Italian nationalism became a major force at both elite and popular levels until 1945, when popular democracy became a much more important force.

Freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

was an influential semi-secret force in Italian politics with a strong presence among professionals and the middle class across Italy, as well as among the leadership in parliament, public administration, and the army. The two main organisation were the Grand Orient and the Grand Lodge of Italy. They had 25,000 members in 500 or more lodges. Freemasons took on the challenge of mobilizing the press, public opinion. and the leading political parties in support of Italy's joining the Allies. traditionally, Italian nationalism focused on unification, and undermining the power of the Catholic Church. In 1914-15 they dropped the traditional pacifistic rhetoric and used instead the powerful language of Italian nationalism. Freemasonry had always promoted cosmopolitan universal values, and by 1917 onwards they demanded a League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

to promote a new post-war universal order based upon the peaceful coexistence of independent and democratic nations.

Italy's demands in the Paris peace settlement of 1919 were not fully achieved: Italy did attain Trentino, Trieste, the Istrian peninsula, and South Tyrol from Austria-Hungary, though other territories previously promised to Italy were not given to it.

In particular, Italian nationalists were enraged by the Allies denying Italy the right to annex

In particular, Italian nationalists were enraged by the Allies denying Italy the right to annex Fiume

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Primor ...

, that had a slight majority Italian population but was not included in Italy's demands agreed with the Allies in 1915, and a larger part of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

which had a vast majority Slavic population and an Italian minority, claiming that Italian annexation of large part of Dalmatia would violate Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

.Reynolds Mathewson Salerno. Vital crossroads: Mediterranean origins of the Second World War, 1935-1940. Ithaca, New York, USA: Cornell University Press, 2002. Pp. 4. D'Annunzio responded to this by mobilizing two thousand veterans of the war who seized Fiume by force; this action was met with international condemnation of d'Annunzio's actions but was supported by a majority of Italians. Though d'Annunzio's government in Fiume was forced from power, Italy annexed Fiume a few years later.

Fascism and World War II (1922 to 1945)

The seizure of power by the Italian Fascist leaderBenito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

as Prime Minister of Italy

The Prime Minister of Italy, officially the President of the Council of Ministers ( it, link=no, Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri), is the head of government of the Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is ...

in 1922 and his development of a fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

totalitarian state in Italy involved appeal to Italian nationalism, advocating and creating a Roman-like Italian Empire

The Italian colonial empire ( it, Impero coloniale italiano), known as the Italian Empire (''Impero Italiano'') between 1936 and 1943, began in Africa in the 19th century and comprised the colonies, protectorates, concessions and dependencie ...

in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

.

Mussolini sought to build closer relations with Germany and the United Kingdom while showing hostility towards France and Yugoslavia. He fought communism in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

in 1936/37 and united Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

to the kingdom of Italy in 1939. In 1940 entered WW2

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

on the side of Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

's Germany, but in September 1943 Italy was forced to surrender to the Allies.

Post–World War II and current situation

After the fall of Fascism and following the birth of the

After the fall of Fascism and following the birth of the Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

, the interest in Italian nationalism by scholars, politicians and the masses was relatively low, mainly because of its close relation with Fascism and consequently with bad memories of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The only notable and active political party who clearly declared Italian nationalism as its main ideology was the neo-fascist

Neo-fascism is a post-World War II far-right ideology that includes significant elements of fascism. Neo-fascism usually includes ultranationalism, racial supremacy, populism, authoritarianism, nativism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration s ...

Italian Social Movement

The Italian Social Movement ( it, Movimento Sociale Italiano, MSI) was a neo-fascist political party in Italy. A far-right party, it presented itself until the 1990s as the defender of Italian fascism's legacy, and later moved towards national ...

(''MSI''), which became the fourth largest party in Italy by the early 1960s. In these years, Italian nationalism was considered an ideology linked to right-wing political parties and organisations. Nevertheless, two significant events seemed to revitalise Italian nationalism among Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

, the first one in 1953 with the Question of Trieste when the claim of Italy on the full control of the city of Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into provi ...

was largely endorsed by most of the Italian society with patriotic demonstrations, and the second one in 1985 during the Sigonella crisis between Italy and the United States.

Alleanza Nazionale

National Alliance ( it, Alleanza Nazionale, AN) was a conservative political party in Italy.Luciano Bardi - Piero Ignazi - Oreste Massari, ''I partiti italiani'', Egea 2007, pp. 151, 173n. It was the successor of the Italian Social Movement (MSI ...

and was in the Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; born 29 September 1936) is an Italian media tycoon and politician who served as Prime Minister of Italy in four governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a member of the Chamber of Deputies ...

governments of Italy: the party was part of all three House of Freedoms

The House of Freedoms ( it, Casa delle Libertà, CdL) was a major centre-right political and electoral alliance in Italy, led by Silvio Berlusconi.

History

The CdL was the successor of the Pole of Freedoms/Pole of Good Government and the Pole fo ...

coalition governments led by Silvio Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; born 29 September 1936) is an Italian media tycoon and politician who served as Prime Minister of Italy in four governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a member of the Chamber of Deputies ...

. Gianfranco Fini (leader of Alleanza Nazionale) was nominated Deputy Prime Minister after the 2001 general election.

In the 2000s, Italian nationalism seemed to gain a moderate support by the society, in particular during important days such as the National Day Festa della Repubblica

''Festa della Repubblica'' (; English: ''Republic Day'') is the Italian National Day and Republic Day, which is celebrated on 2 June each year, with the main celebration taking place in Rome. The ''Festa della Repubblica'' is one of the national ...

(Republic day) and the Anniversary of the Liberation. The President of the Republic Carlo Azeglio Ciampi

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi (; 9 December 1920 – 16 September 2016) was an Italian politician and banker who was the prime minister of Italy from 1993 to 1994 and the president of Italy from 1999 to 2006.

Biography Education

Ciampi was born i ...

has often praised patriotism among Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

by mentioning in his speeches national events, including the Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

or the Resistenza

The Italian resistance movement (the ''Resistenza italiana'' and ''la Resistenza'') is an umbrella term for the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social ...

, and national symbols like the Flag of Italy

The national flag of Italy ( it, Bandiera d'Italia, ), often referred to in Italian as ''il Tricolore'' ( en, the Tricolour, ) is a tricolour (flag), tricolour featuring three equally sized vertical Pale (heraldry), pales of green, white and red, ...

and the National Anthem

A national anthem is a patriotic musical composition symbolizing and evoking eulogies of the history and traditions of a country or nation. The majority of national anthems are marches or hymns in style. American, Central Asian, and European n ...

, although he seems to want to stress self-confidence rather than plain nationalism. In 2011, the 150th Anniversary of Italian Unification showed a moderately renewed interest in Italian nationalism among the society. Nationalist ideologies are often present during Italian anti-globalisation protests. Today, Italian nationalism is still mainly supported by right-wing political parties like Brothers of Italy

Brothers of Italy ( it, Fratelli d'Italia, FdI) is a national-conservative and right-wing populist political party in Italy. It is led by Giorgia Meloni, the incumbent Prime Minister of Italy and the first woman to serve in the position. Accor ...

and minor far-right political parties like The Right, CasaPound, Forza Nuova

New Force ( it, Forza Nuova, FN) is an Italian neo-fascist political party. It was founded by Roberto Fiore and Massimo Morsello. The party is a member of the Alliance for Peace and Freedom and was a part of the Social Alternative from 2003 to 20 ...

and Tricolour Flame

The Social Movement Tricolour Flame ( it, Movimento Sociale Fiamma Tricolore, MSFT), commonly known as Tricolour Flame (''Fiamma Tricolore''), is a neo-fascist political party in Italy.

History

The party was started by the more radical members ...

. Nonetheless, in recent times Italian nationalism has been occasionally embraced as a form of banal nationalism by liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

parties like Forza Italia

Forza ItaliaThe name is not usually translated into English: ''forza'' is the second-person singular imperative of ''forzare'', in this case translating to "to compel" or "to press", and so means something like "Forward, Italy", "Come on, Ital ...

, centrist parties like the Union of the Centre or even by centre-left parties like the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

.

Italian nationalism has also faced a great deal of opposition from within Italy itself. Regionalism and municipal identities have challenged the concept of a unified Italian identity, like those in Friuli-Venezia Giulia

(man), it, Friulana (woman), it, Giuliano (man), it, Giuliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_t ...

, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and Veneto

Veneto (, ; vec, Vèneto ) or Venetia is one of the 20 regions of Italy. Its population is about five million, ranking fourth in Italy. The region's capital is Venice while the biggest city is Verona.

Veneto was part of the Roman Empire unt ...

.Peter Wagstaff. ''Regionalism in the European Union''. Intellect Books, 1999. P; 141 Such regional identities evoked strong opposition after the Piedmontese-led unification of Italy to plans for "Piedmontization" of Italy. Italian identity has also been long strained by an ever growing north–south divide that developed partly from the economic differences of a highly industrialized North and a highly agricultural South.Damian Tambini. ''Nationalism in Italian Politics: The Stories of the Northern League, 1980-2000''. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2001. P. 34.

Symbols

Italian nationalist parties

Current

* Fascism and Freedom Movement (1991–present) *Tricolour Flame

The Social Movement Tricolour Flame ( it, Movimento Sociale Fiamma Tricolore, MSFT), commonly known as Tricolour Flame (''Fiamma Tricolore''), is a neo-fascist political party in Italy.

History

The party was started by the more radical members ...

(1995–present)

* Unitalia (1996–present)

* National Front (1997–present)

* New Force (1997–present)

* New Italian Social Movement (2000–present)

* CasaPound (2003–present)

* Social Idea Movement (2004–present)

*Brothers of Italy

Brothers of Italy ( it, Fratelli d'Italia, FdI) is a national-conservative and right-wing populist political party in Italy. It is led by Giorgia Meloni, the incumbent Prime Minister of Italy and the first woman to serve in the position. Accor ...

(2012–present)

*Social Right

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and variety of conservatism which places emphasis on traditional power structures over social pluralism. Social conservatives organize in favor of duty, traditional values and social institutio ...

(2013–present)

* United Right (2014–present)

Former

* Action Party (1848–1867) *Italian Nationalist Association

The Italian Nationalist Association (''Associazione Nazionalista Italiana'', ANI) was Italy's first nationalist political movement founded in 1910, under the influence of Italian nationalists such as Enrico Corradini and Giovanni Papini. Upon it ...

(1910–1923)

* Fascio Rivoluzionario d'Azione Internazionalista (1914)

*Fasci d'Azione Rivoluzionaria

The ''Fascio d'Azione Rivoluzionaria'' (translatable into English as ''"Fasces of Revolutionary Action"''; figuratively ''"League of Revolutionary Action"'') was an Italian political movement founded in 1914 by Benito Mussolini, and active mainly ...

(1915–1919)

*Futurist Political Party

The Futurist Political Party ( it, Partito Politico Futurista) was an Italian political party founded in 1918 by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti as an extension of the futurist artistic and social movement. The party had a radical program which includ ...

(1918–1920)

*Fasci Italiani di Combattimento

The ''Fasci Italiani di Combattimento'' ( en, Italian Fasces of Combat, link=yes, also translatable as ''"Italian Fighting Bands"'' or ''"Italian Fighting Leagues"'') was an Italian Fascism, Italian Fascist organization created by Benito Mussolin ...

(1919–1921)

*National Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party ( it, Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian Fascism and as a reorganization of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The ...

(1921–1943)

*Republican Fascist Party

The Republican Fascist Party ( it, Partito Fascista Repubblicano, PFR) was a political party in Italy led by Benito Mussolini during the German occupation of Central and Northern Italy and was the sole legal and ruling party of the Italian Socia ...

(1943–1945)

* Democratic Fascist Party (1945–1946)

* Italian Movement of Social Unity (1946)

*Italian Social Movement

The Italian Social Movement ( it, Movimento Sociale Italiano, MSI) was a neo-fascist political party in Italy. A far-right party, it presented itself until the 1990s as the defender of Italian fascism's legacy, and later moved towards national ...

(1946–1995)

*Alleanza Nazionale

National Alliance ( it, Alleanza Nazionale, AN) was a conservative political party in Italy.Luciano Bardi - Piero Ignazi - Oreste Massari, ''I partiti italiani'', Egea 2007, pp. 151, 173n. It was the successor of the Italian Social Movement (MSI ...

(1995-2009)

* National Front (1967–1970)

* National Front (1990–2000)

* The Right (2007–2017)

*National Movement for Sovereignty

The National Movement for Sovereignty ( it, Movimento Nazionale per la Sovranità, MNS) was a national-conservative political party in Italy, founded on 18 February 2017, with the merger of National Action and The Right. Its founders were Gianni ...

(2017–2019)

Personalities

* Gabriele D'Annunzio *Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

* Giorgio Almirante

*Roberto Fiore

Roberto Fiore (born 15 April 1959) is an Italian politician and the leader of the party Forza Nuova, convicted in Italy for subversion and armed gang for his links to the right wing terrorism organization "Terza posizione". He self-identifies ...

*Massimo Morsello

Massimo Morsello (10 November 1958, Rome – 10 March 2001) was an Italian fascist political and singer-songwriter. He was the main figure of Italian fascist political music and, with Roberto Fiore, a co-founder of the Italian neo-fascist moveme ...

*Roberto Farinacci

Roberto Farinacci (; 16 October 1892 – 28 April 1945) was a leading Italian Fascist politician and important member of the National Fascist Party before and during World War II as well as one of its ardent antisemitic proponents. English histo ...

*Stefano Delle Chiaie

Stefano Delle Chiaie (13 September 1936, Caserta – 10 September 2019, Rome) was an Italian neo-fascist terrorist. He was the founder of ''Avanguardia Nazionale'', a member of '' Ordine Nuovo'', and founder of Lega nazionalpopolare. He went on ...

*Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, , ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the in ...

See also

* Nationalism (Italy) *Italian Empire

The Italian colonial empire ( it, Impero coloniale italiano), known as the Italian Empire (''Impero Italiano'') between 1936 and 1943, began in Africa in the 19th century and comprised the colonies, protectorates, concessions and dependencie ...

* History of Italy

The history of Italy covers the ancient period, the Middle Ages, and the modern era. Since classical antiquity, ancient Etruscan civilization, Etruscans, various Italic peoples (such as the Latins, Samnites, and Umbri), Celts, ''Magna Graecia'' ...

* Italian culture

* Italian Fascism

* Italian irredentism

Italian irredentism ( it, irredentismo italiano) was a nationalist movement during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Italy with irredentist goals which promoted the unification of geographic areas in which indigenous peoples ...

* Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

* Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

* Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

References

Further reading

* Barbour, Stephen and Cathie Carmichael, eds. (2000). ''Language and Nationalism in Europe'' (Oxford UP) chapter 8. * Cunsolo, Ronald S. "Italian nationalism in historical perspective." ''History of European Ideas'' 16.4-6 (1993): 759–766. * Cunsolo, Ronald S. ''Italian nationalism: from its origins to World War II'' (Krieger Pub Co, 1990). * Cunsolo, Ronald S. "Italian Emigration and Its Effect on the Rise of Nationalism." ''Italian Americana

''Italian Americana'' is a biannual peer-reviewed academic journal covering studies on the Italian-American experience. It publishes history, fiction, memoirs, poetry, and reviews. The editor-in-chief is Carla A. Simonini ( Loyola University Chic ...

'' 12.1 (1993): 62–72in JSTOR

* Drake, Richard. "The Theory and Practice of Italian Nationalism, 1900-1906." ''Journal of Modern History'' (1981): 213–241

in JSTOR

* Marsella, Mauro. "Enrico Corradini's Italian nationalism: the ‘right wing’ of the fascist synthesis." ''Journal of Political Ideologies'' 9.2 (2004): 203-224. * * Noether, Emiliana Pasca. ''Seeds of Italian nationalism, 1700-1815'' (Columbia University Press, 1951). * Noether, Emiliana P. "The intellectual dimension of italian nationalism: An overview." ''History of European Ideas'' 16.4-6 (1993): 779–784. * Patriarca, Silvana, and Lucy Riall, eds., ''The Risorgimento Revisited: Nationalism and Culture in Nineteenth-century Italy'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011) * Salvadori, Massimo. "Nationalism in Modern Italy-1915 and after." ''Orbis-A Journal of World Affairs'' 10.4 (1967): 1157–1175. * Sluga, Glenda A. "The Risiera di San Sabba: Fascism, anti‐Fascism and Italian nationalism." ''Journal of Modern Italian Studies'' 1.3 (1996): 401–412. * Tambini, Damian. ''Nationalism in Italian politics: The stories of the Northern League, 1980-2000'' (Routledge, 2012). {{Authority control History of Europe Political history of Italy Italian culture Italian unification