Italian Irredentists on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Italian irredentism ( it, irredentismo italiano) was a nationalist

Italian irredentism was not a formal organization but rather an opinion movement, advocated by several different groups, claiming that Italy had to reach its "natural borders" or unify territories inhabited by Italians. Similar nationalistic ideas were common in Europe in the late 19th century. The term "irredentism", coined from the Italian word, came into use in many countries (see List of irredentist claims or disputes). This idea of ''Italia irredenta'' is not to be confused with the Risorgimento, the historical events that led to irredentism, nor with nationalism or Imperial Italy, the political philosophy that took the idea further under fascism.

During the 19th century, Italian irredentism fully developed the characteristic of defending the Italian language from other people's languages like, for example, German in Switzerland and in the Austro-Hungarian Empire or French in Nice and

Italian irredentism was not a formal organization but rather an opinion movement, advocated by several different groups, claiming that Italy had to reach its "natural borders" or unify territories inhabited by Italians. Similar nationalistic ideas were common in Europe in the late 19th century. The term "irredentism", coined from the Italian word, came into use in many countries (see List of irredentist claims or disputes). This idea of ''Italia irredenta'' is not to be confused with the Risorgimento, the historical events that led to irredentism, nor with nationalism or Imperial Italy, the political philosophy that took the idea further under fascism.

During the 19th century, Italian irredentism fully developed the characteristic of defending the Italian language from other people's languages like, for example, German in Switzerland and in the Austro-Hungarian Empire or French in Nice and

Pasquale Paoli's appeal in 1768 against the French invader said:

Paoli's

Pasquale Paoli's appeal in 1768 against the French invader said:

Paoli's

In the early 19th century the ideals of unification in a single Nation of all the territories populated by Italian-speaking people created the Italian irredentism. Many Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians looked with sympathy towards the Risorgimento movement that fought for the unification of Italy.

The current Italian Switzerland belonged to the

In the early 19th century the ideals of unification in a single Nation of all the territories populated by Italian-speaking people created the Italian irredentism. Many Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians looked with sympathy towards the Risorgimento movement that fought for the unification of Italy.

The current Italian Switzerland belonged to the  The Kingdom of Sardinia again attacked the Austrian Empire in the Second Italian War of Independence of 1859, with the aid of France, resulting in liberating

The Kingdom of Sardinia again attacked the Austrian Empire in the Second Italian War of Independence of 1859, with the aid of France, resulting in liberating

Italy entered the First World War in 1915 with the aim of completing national unity: for this reason, the Italian intervention in the First World War is also considered the Fourth Italian War of Independence, in a historiographical perspective that identifies in the latter the conclusion of the unification of Italy, whose military actions began during the revolutions of 1848 with the

Italy entered the First World War in 1915 with the aim of completing national unity: for this reason, the Italian intervention in the First World War is also considered the Fourth Italian War of Independence, in a historiographical perspective that identifies in the latter the conclusion of the unification of Italy, whose military actions began during the revolutions of 1848 with the

To the east of Italy, the Fascists claimed that

To the east of Italy, the Fascists claimed that  To the west of Italy, the Fascists claimed that the territories of

To the west of Italy, the Fascists claimed that the territories of

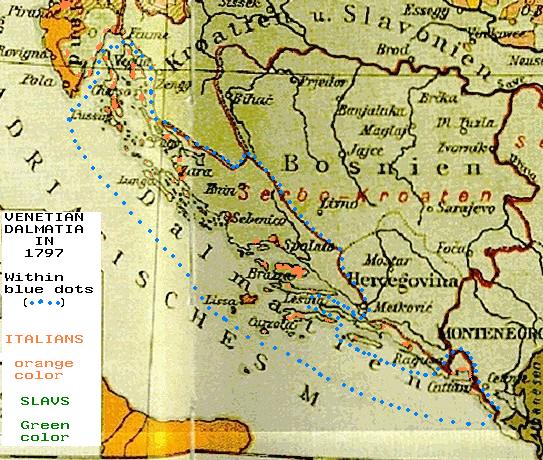

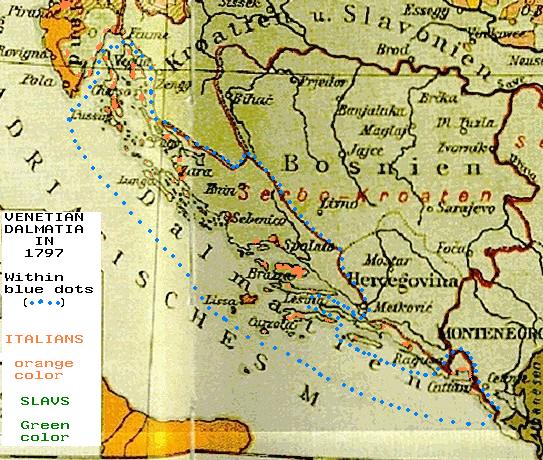

Dalmatia was a strategic region during World War I that both Italy and Serbia intended to seize from Austria-Hungary. Italy joined the Triple Entente

Dalmatia was a strategic region during World War I that both Italy and Serbia intended to seize from Austria-Hungary. Italy joined the Triple Entente  The last city with a significant Italian presence in Dalmatia was the city of Zara (now called Zadar). In the Austro-Hungarian census of 1910, the city of Zara had an Italian population of 9,318 (or 69.3% out of the total of 13,438 inhabitants). In 1921 the population grew to 17,075 inhabitants, of which 12,075 Italians (corresponding to 70,76%).

In 1941, during the Second World War, Yugoslavia was occupied by Italy and Germany. Dalmatia was divided between Italy, which constituted the Governorate of Dalmatia, and the Independent State of Croatia, which annexed Dubrovnik and Morlachia. After the

The last city with a significant Italian presence in Dalmatia was the city of Zara (now called Zadar). In the Austro-Hungarian census of 1910, the city of Zara had an Italian population of 9,318 (or 69.3% out of the total of 13,438 inhabitants). In 1921 the population grew to 17,075 inhabitants, of which 12,075 Italians (corresponding to 70,76%).

In 1941, during the Second World War, Yugoslavia was occupied by Italy and Germany. Dalmatia was divided between Italy, which constituted the Governorate of Dalmatia, and the Independent State of Croatia, which annexed Dubrovnik and Morlachia. After the

Under the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947,

Under the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947,

Talijanski ministar najavio invaziju na Dalmaciju, Oct 19, 2005 ("Italian minister announced an invasion on Dalmatia") Giovanardi later declared that he had been misunderstood"Veleni nazionalisti sulla casa degli italiani" su Corriere della Sera del 21/10/2005

("Nationalist poisons on the house of Italians") archiviostampa.it and sent a letter to the Croatian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in which he condemned nationalism and ethnic strife. They underlined that Alleanza Nazionale (a former Italian conservative party) derived directly from the

*

*

Unredeemed Italy (Google Books)

*

Movimento irredentista italiano

Italian irredentist movement *

Hrvati AMAC

Gdje su granice (EU-)talijanskog bezobrazluka? (''Where are the limits of Italian arrogancy?''; page contains the speech of Italian deputy) *

Slobodna Dalmacija

Počasni građanin Zadra kočnica talijanskoj ratifikaciji SSP-a *

D'Annunzio and Rijeka

*

Politicamentecorretto.com

Guglielmo Picchi Forza Italia *

Francobollo Fiume: bloccata l'emissione *

Trieste.rvnet.eu

Stoppato il francobollo per Fiume, bufera: protestano Unione degli istriani, An e Forza Italia (contains the scan of the stamp) {{DEFAULTSORT:Italian Irredentism * History of Austria-Hungary History of Istria History of Dalmatia History of Malta Politics of World War II Politics of World War I Italy de:Irredentismus#Italienischer Irredentismus

movement

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Italy with irredentist goals which promoted the unification of geographic areas in which indigenous peoples considered to be ethnic Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

and/or Italian-speaking individuals formed a majority, or substantial minority, of the population.

At the beginning, the movement promoted the annexation to Italy of territories inhabited by Italian indigenous population, but retained by the Austrian Empire after the Third Italian War of Independence in 1866. These included Trentino, but also multilingual and multiethnic areas within the northern Italian region encompassed by the Alps, with German, Italian, Slovene, Croatian, Ladin and Istro-Romanian population, such as South Tyrol, Trieste, a part of Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

, Gorizia and Gradisca and part of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

. The claims were extended also to the city of Fiume, Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

, the island of Malta, the County of Nice and Italian Switzerland.

During the '' Risorgimento'' in 1860, the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Sardinia Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, who was leading the unification effort, faced the view of French Emperor

Emperor of the French ( French: ''Empereur des Français'') was the title of the monarch and supreme ruler of the First and the Second French Empires.

Details

A title and office used by the House of Bonaparte starting when Napoleon was procl ...

Napoleon III who indicated that France would support militarily the Italian unification provided that France was given Nice and Savoy that were held by Sardinia, as France did not want a powerful state having control of the passages of the Alps.Adda Bruemmer Bozeman. Regional Conflicts Around Geneva: An Inquiry Into the Origin, Nature, and Implications of the Neutralized Zone of Savoy and of the Customs-free Zones of Gex and Upper Savoy. P. 196. As a result, Sardinia was pressured to cede Nice and Savoy to France in exchange for France accepting the sending of troops to help the unification of Italy.Adda Bruemmer Bozeman. Regional Conflicts Around Geneva: An Inquiry Into the Origin, Nature, and Implications of the Neutralized Zone of Savoy and of the Customs-free Zones of Gex and Upper Savoy. Stanford, California, USA: Stanford University Press, 1949. P. 196.

To avoid confusion and in line with convention

Convention may refer to:

* Convention (norm), a custom or tradition, a standard of presentation or conduct

** Treaty, an agreement in international law

* Convention (meeting), meeting of a (usually large) group of individuals and/or companies in a ...

, this article uses modern English place names throughout. However, most places have alternative names in Italian. See List of Italian place names in Dalmatia.

Characteristics

Italian irredentism was not a formal organization but rather an opinion movement, advocated by several different groups, claiming that Italy had to reach its "natural borders" or unify territories inhabited by Italians. Similar nationalistic ideas were common in Europe in the late 19th century. The term "irredentism", coined from the Italian word, came into use in many countries (see List of irredentist claims or disputes). This idea of ''Italia irredenta'' is not to be confused with the Risorgimento, the historical events that led to irredentism, nor with nationalism or Imperial Italy, the political philosophy that took the idea further under fascism.

During the 19th century, Italian irredentism fully developed the characteristic of defending the Italian language from other people's languages like, for example, German in Switzerland and in the Austro-Hungarian Empire or French in Nice and

Italian irredentism was not a formal organization but rather an opinion movement, advocated by several different groups, claiming that Italy had to reach its "natural borders" or unify territories inhabited by Italians. Similar nationalistic ideas were common in Europe in the late 19th century. The term "irredentism", coined from the Italian word, came into use in many countries (see List of irredentist claims or disputes). This idea of ''Italia irredenta'' is not to be confused with the Risorgimento, the historical events that led to irredentism, nor with nationalism or Imperial Italy, the political philosophy that took the idea further under fascism.

During the 19th century, Italian irredentism fully developed the characteristic of defending the Italian language from other people's languages like, for example, German in Switzerland and in the Austro-Hungarian Empire or French in Nice and Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

.

The liberation of ''Italia irredenta'' was perhaps the strongest motive for Italy's entry into World War I and the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 satisfied many irredentist claims.

Italian irredentism has the characteristic of being originally moderate, requesting only the return to Italy of the areas with Italian majority of population, but after World War I it became aggressive – under fascist influence – and claimed to the Kingdom of Italy even areas where Italians were a minority or had been present only in the past. In the first case there were the Risorgimento claims on Trento, while in the second there were the fascist claims on the Ionian Islands, Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

and Malta.

Origins

The Corsican revolutionary Pasquale Paoli was called "the precursor of Italian irredentism" by Niccolò Tommaseo because he was the first to promote the Italian language and socio-culture (the main characteristics of Italian irredentism) in his island; Paoli wanted the Italian language to be the official language of the newly founded Corsican Republic. Pasquale Paoli's appeal in 1768 against the French invader said:

Paoli's

Pasquale Paoli's appeal in 1768 against the French invader said:

Paoli's Corsican Constitution

The first Corsican Constitution was drawn up in 1755 for the short-lived Corsican Republic independent from Genoa beginning in 1755, and remained in force until the annexation of Corsica by France in 1769. It was written in Tuscan Italian, the la ...

of 1755 was written in Italian and the short-lived university he founded in the city of Corte in 1765 used Italian as the official language.

After the Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

and Third Italian War of Independence in 1866, there were areas with Italian-speaking communities within the borders of several countries around the newly created Kingdom of Italy. The irredentists sought to annex all those areas to the newly unified Italy. The areas targeted were Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

, Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

, Gorizia, Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

, Malta, County of Nice, Ticino, small parts of Grisons

The Grisons () or Graubünden,Names include:

*german: (Kanton) Graubünden ;

* Romansh:

** rm, label= Sursilvan, (Cantun) Grischun

** rm, label=Vallader, (Chantun) Grischun

** rm, label= Puter, (Chantun) Grischun

** rm, label=Surmiran, (Cant ...

and of Valais, Trentino, Trieste and Fiume.

Different movements or groups founded in this period: in 1877 the Italian politician Matteo Renato Imbriani invented the new term ''terre irredente'' ("unredeemed lands"); in the same year the movement ''Associazione in pro dell'Italia Irredenta'' ("Association for the Unredeemed Italy") was founded; in 1885 was founded the ''Pro Patria'' movement ("For Fatherland") and in 1891 the ''Lega Nazionale Italiana'' ("Italian National League") was founded in Trento and Trieste (in the Austrian Empire).

Initially, the movement can be described as part of the more general nation-building

Nation-building is constructing or structuring a national identity using the power of the state. Nation-building aims at the unification of the people within the state so that it remains politically stable and viable in the long run. According to ...

process in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries when the multi-national Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, Russian and Ottoman Empires were being replaced by nation-states. The Italian nation-building process can be compared to similar movements in Germany (''Großdeutschland

Pan-Germanism (german: Pangermanismus or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify all the German-speaking people – and possibly also Germanic-speaking ...

''), Hungary, Serbia and in pre-1914 Poland. Simultaneously, in many parts of 19th-century Europe liberalism and nationalism were ideologies which were coming to the forefront of political culture. In Eastern Europe, where the Habsburg Empire had long asserted control over a variety of ethnic and cultural groups, nationalism appeared in a standard format. The beginning of the 19th century "was the period when the smaller, mostly indigenous nationalities of the empire – Czechs, Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

, Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Ukrainians, Romanians – remembered their historical traditions, revived their native tongues as literary languages, reappropriated their traditions and folklore, in short, reasserted their existence as nations".

19th century

In the early 19th century the ideals of unification in a single Nation of all the territories populated by Italian-speaking people created the Italian irredentism. Many Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians looked with sympathy towards the Risorgimento movement that fought for the unification of Italy.

The current Italian Switzerland belonged to the

In the early 19th century the ideals of unification in a single Nation of all the territories populated by Italian-speaking people created the Italian irredentism. Many Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians looked with sympathy towards the Risorgimento movement that fought for the unification of Italy.

The current Italian Switzerland belonged to the Duchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan ( it, Ducato di Milano; lmo, Ducaa de Milan) was a state in northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti family, which had been ruling the city sin ...

until the 16th century

The 16th century begins with the Julian year 1501 ( MDI) and ends with either the Julian or the Gregorian year 1600 ( MDC) (depending on the reckoning used; the Gregorian calendar introduced a lapse of 10 days in October 1582).

The 16th cent ...

, when it became part of Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

. These territories have maintained their native Italian population speaking the Italian language and the Lombard language, specifically the Ticinese dialect. Italian irredentism in Switzerland was based on moderate Risorgimento ideals, and was promoted by Italian-Ticinese such as Adolfo Carmine Adolfo may refer to:

* Adolfo, São Paulo, a Brazilian municipality

* Adolfo (designer), Cuban-born American fashion designer

* Adolfo or Adolf, a given name

See also

*

{{dab ...

.

Following a brief French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

occupation (1798–1800) the British established control over Malta while it was still formally part of the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily ( la, Regnum Siciliae; it, Regno di Sicilia; scn, Regnu di Sicilia) was a state that existed in the south of the Italian Peninsula and for a time the region of Ifriqiya from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 un ...

. During both the French and British periods, Malta officially remained part of the Sicilian Kingdom, although the French refused to recognise the island as such in contrast to the British. Malta became a British Crown Colony in 1813, which was confirmed a year later through the Treaty of Paris (1814). Cultural changes were few even after 1814. In 1842, all literate Maltese learned Italian while only 4.5% could read, write and/or speak English. However, there was a huge increase in the number of Maltese magazines and newspapers in the Italian language during the 1800s and early 1900s, so as a consequence the Italian was understood (but not spoken fluently) by more than half the Maltese people before WW1.

The Kingdom of Sardinia again attacked the Austrian Empire in the Second Italian War of Independence of 1859, with the aid of France, resulting in liberating

The Kingdom of Sardinia again attacked the Austrian Empire in the Second Italian War of Independence of 1859, with the aid of France, resulting in liberating Lombardy

Lombardy ( it, Lombardia, Lombard language, Lombard: ''Lombardia'' or ''Lumbardia' '') is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in the northern-central part of the country and has a population of about 10 ...

. On the basis of the Plombières Agreement, the Kingdom of Sardinia ceded Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

and Nice to France, an event that caused the Niçard exodus, that was the emigration of a quarter of the Niçard Italians to Italy. Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

was elected in 1871 in Nice at the National Assembly where he tried to promote the annexation of his hometown to the newborn Italian unitary state, but he was prevented from speaking. Because of this denial, between 1871 and 1872 there were riots in Nice, promoted by the Garibaldini and called "Niçard Vespers", which demanded the annexation of the city and its area to Italy. Fifteen Nice people who participated in the rebellion were tried and sentenced.

In the spring of 1860 Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

was annexed to France after a referendum and the administrative boundaries changed, but a segment of the Savoyard population demonstrated against the annexation. Indeed, the final vote count on the referendum announced by the Court of Appeals was 130,839 in favour of annexation to France, 235 opposed and 71 void, showing questionable complete support for French nationalism (that motivated criticisms about rigged results). At the beginning of 1860, more than 3000 people demonstrated in Chambéry against the annexation to France rumours. On 16 March 1860, the provinces of Northern Savoy (Chablais, Faucigny and Genevois) sent to Victor Emmanuel II, to Napoleon III, and to the Swiss Federal Council a declaration - sent under the presentation of a manifesto together with petitions - where they were saying that they did not wish to become French and shown their preference to remain united to the Kingdom of Sardinia (or be annexed to Switzerland in the case a separation with Sardinia was unavoidable).

In 1861, with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, the modern Italian state was born. On 21 July 1878, a noisy public meeting was held at Rome with Menotti Garibaldi, the son of Giuseppe Garibaldi, as chairman of the forum and a clamour was raised for the formation of volunteer battalions to conquer the Trentino. Benedetto Cairoli, then Prime Minister of Italy, treated the agitation with tolerance. However, it was mainly superficial, as most Italians did not wish a dangerous policy against Austria or against Britain for Malta.

One consequence of irredentist ideas outside of Italy was an assassination plot organized against the Emperor Francis Joseph in Trieste in 1882, which was detected and foiled. Guglielmo Oberdan

Guglielmo Oberdan, (born Wilhelm Oberdank) (February 1, 1858 - December 20, 1882) was an Italian irredentist. He was executed after a failed attempt to assassinate Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, becoming a martyr of the Italian unification movem ...

, a Triestine and thus Austrian citizen, was executed. When the irredentist movement became troublesome to Italy through the activity of Republicans and Socialists, it was subject to effective police control by Agostino Depretis

Agostino Depretis (31 January 181329 July 1887) was an Italian statesman and politician. He served as Prime Minister of Italy for several stretches between 1876 and 1887, and was leader of the Historical Left parliamentary group for more than a de ...

.

Irredentism faced a setback when the French occupation of Tunisia in 1881 started a crisis in French–Italian relations. The government entered into relations with Austria and Germany, which took shape with the formation of the Triple Alliance Triple Alliance may refer to:

* Aztec Triple Alliance (1428–1521), Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan and in central Mexico

* Triple Alliance (1596), England, France, and the Dutch Republic to counter Spain

* Triple Alliance (1668), England, the ...

in 1882. The irredentists' dream of absorbing the targeted areas into Italy made no further progress in the 19th century, as the borders of the Kingdom of Italy remained unchanged and the Rome government began to set up colonies in Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia ...

and Somalia in Africa.

World War I

Italy entered the First World War in 1915 with the aim of completing national unity: for this reason, the Italian intervention in the First World War is also considered the Fourth Italian War of Independence, in a historiographical perspective that identifies in the latter the conclusion of the unification of Italy, whose military actions began during the revolutions of 1848 with the

Italy entered the First World War in 1915 with the aim of completing national unity: for this reason, the Italian intervention in the First World War is also considered the Fourth Italian War of Independence, in a historiographical perspective that identifies in the latter the conclusion of the unification of Italy, whose military actions began during the revolutions of 1848 with the First Italian War of Independence

The First Italian War of Independence ( it, Prima guerra d'indipendenza italiana), part of the Italian Unification (''Risorgimento''), was fought by the Kingdom of Sardinia (Piedmont) and Italian volunteers against the Austrian Empire and other ...

.

Italy signed the London Pact and entered World War I with the intention of gaining those territories perceived by irredentists as being Italian under foreign rule. According to the pact, Italy was to leave the Triple Alliance Triple Alliance may refer to:

* Aztec Triple Alliance (1428–1521), Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan and in central Mexico

* Triple Alliance (1596), England, France, and the Dutch Republic to counter Spain

* Triple Alliance (1668), England, the ...

and join the Entente Powers. Furthermore, Italy was to declare war on Germany and Austria-Hungary within a month. The declaration of war was duly published on 23 May 1915. In exchange, Italy was to obtain various territorial gains at the end of the war. In April 1918, in what he described as an open letter "to the American Nation" Paolo Thaon di Revel, Commander in Chief of the Italian navy

"Fatherland and Honour"

, patron =

, colors =

, colors_label =

, march = ( is the return of soldiers to their barrack, or sailors to their ship after a ...

, appealed to the people of the United States to support Italian territorial claims over Trento, Trieste, Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

, Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

and the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) ...

, writing that "we are fighting to expel an intruder from our home".

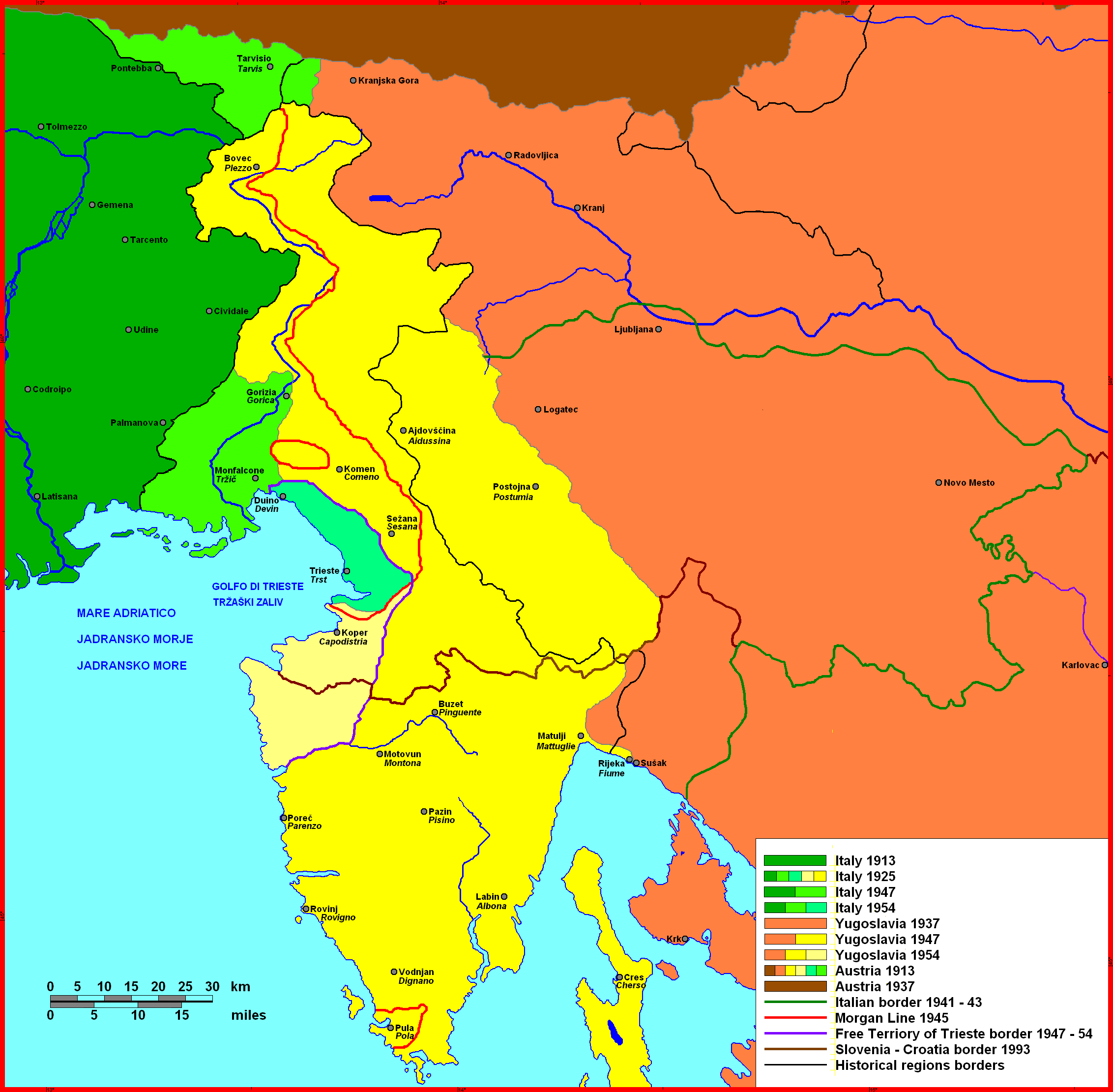

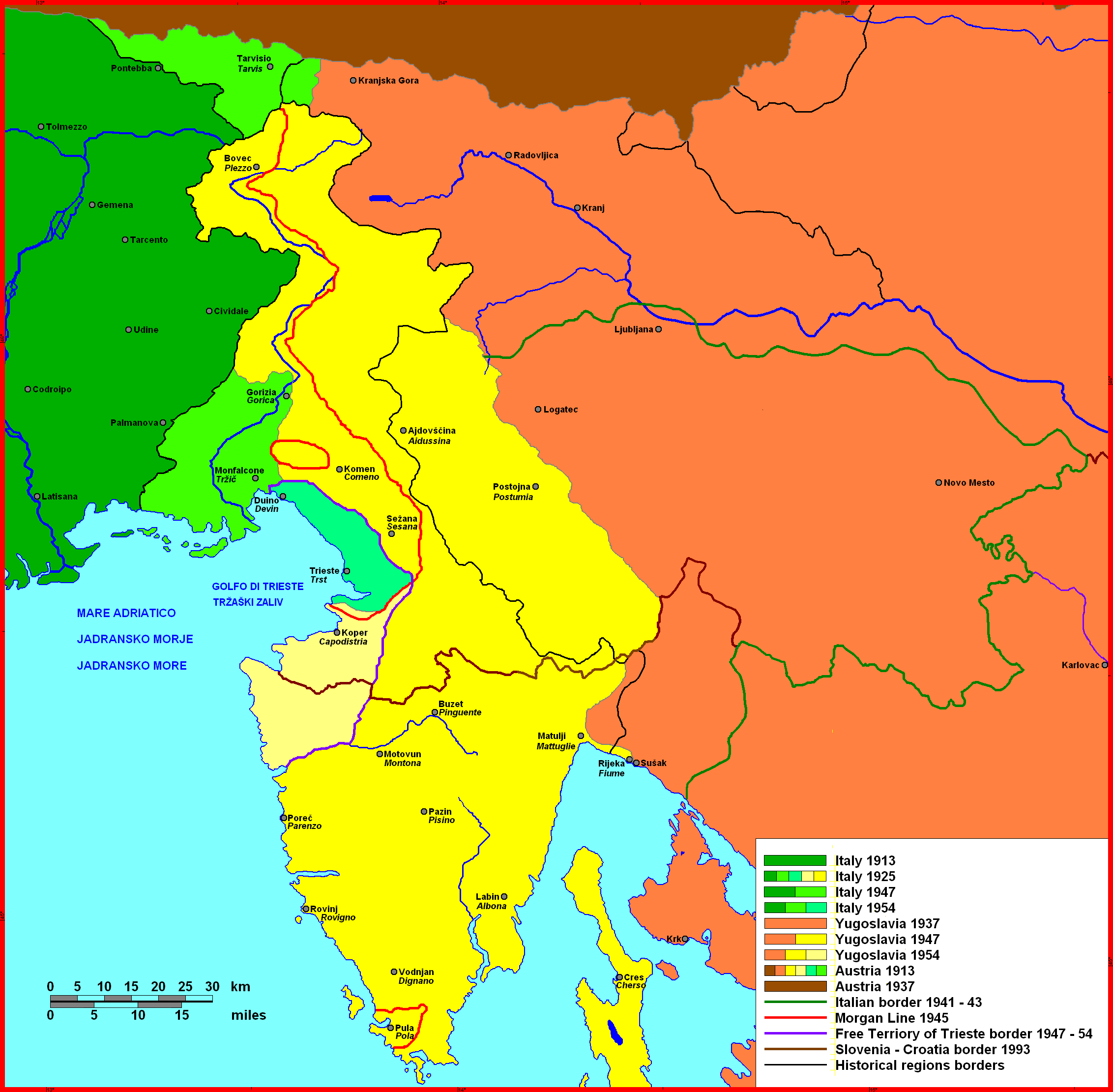

The outcome of the First World War and the consequent settlement of the Treaty of Saint-Germain met some Italian claims, including many (but not all) of the aims of the ''Italia irredenta'' party. Italy gained Trieste, Gorizia, Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

and the Dalmatian city of Zara. In Dalmatia, despite the London Pact, only territories with Italian majority as Zadar (Zara) with some Dalmatian islands, such as Cres (Cherso), Lošinj (Lussino) and Lastovo (Lagosta) were annexed by Italy because Woodrow Wilson, supporting Yugoslav claims and not recognizing the treaty, rejected Italian requests on other Dalmatian territories, so this outcome was denounced as a " Mutilated victory". The rhetoric of "Mutilated victory" was adopted by Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

and led to the rise of Italian fascism, becoming a key point in the propaganda of Fascist Italy. Historians regard "Mutilated victory" as a "political myth", used by fascists to fuel Italian imperialism and obscure the successes of liberal Italy in the aftermath of World War I.

The city of Rijeka

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Primor ...

(Fiume) in the Kvarner was the subject of claim and counter-claim because it had an Italian majority, but Fiume had not been promised to Italy in the London Pact, though it was to become Italian by 1924 (see Italian Regency of Carnaro, Treaty of Rapallo, 1920 and Treaty of Rome, 1924). The stand taken by the irredentist Gabriele D'Annunzio, which briefly led him to become an enemy of the Italian state, was meant to provoke a nationalist revival through corporatism (first instituted during his rule over Fiume), in front of what was widely perceived as state corruption engineered by governments such as Giovanni Giolitti

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the Prime Minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. After Benito Mussolini, he is the second-longest serving Prime Minister in Italian history. A pr ...

's. D'Annunzio briefly annexed to this "Regency of Carnaro" even the Dalmatian islands of Krk (Veglia) and Rab (Arbe), where there was a numerous Italian community.

Fascism and World War II

Fascist Italy strove to be seen as the natural result of war heroism against a " betrayed Italy" that had not been awarded all it "deserved", as well as appropriating the image of Arditi soldiers. In this vein, irredentist claims were expanded and often used in Fascist Italy's desire to control the Mediterranean basin. To the east of Italy, the Fascists claimed that

To the east of Italy, the Fascists claimed that Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

was a land of Italian culture whose Italians, including those of Italianized South Slavic descent, had been driven out of Dalmatia and into exile in Italy, and supported the return of Italians of Dalmatian heritage. Mussolini identified Dalmatia as having strong Italian cultural roots for centuries via the Roman Empire and the Republic of Venice.Larry Wolff. Venice And the Slavs: The Discovery of Dalmatia in the Age of Enlightenment. Stanford, California, USA: Stanford University Press, P. 355. The Fascists especially focused their claims based on the Venetian cultural heritage of Dalmatia, claiming that Venetian rule had been beneficial for all Dalmatians and had been accepted by the Dalmatian population. The Fascists were outraged after World War I, when the agreement between Italy and the Entente Allies in the Treaty of London of 1915 to have Dalmatia join Italy was revoked in 1919.

To the west of Italy, the Fascists claimed that the territories of

To the west of Italy, the Fascists claimed that the territories of Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

, Nice and Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

held by France were Italian lands. The Fascist regime produced literature on Corsica that presented evidence of the island's ''italianità''.Davide Rodogno. ''Fascism's European Empire: Italian Occupation during the Second World War''. Cambridge, England, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006. P. 88. The Fascist regime produced literature on Nice that justified that Nice was an Italian land based on historic, ethnic and linguistic grounds. The Fascists quoted Medieval Italian scholar Petrarch who said: "The border of Italy is the Var; consequently Nice is a part of Italy". The Fascists quoted Italian national hero Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

, a native of Nizza (Nice) himself, who said: "Corsica and Nice must not belong to France; there will come the day when an Italy mindful of its true worth will reclaim its provinces now so shamefully languishing under foreign domination". Mussolini initially pursued promoting annexation of Corsica through political and diplomatic means, believing that Corsica could be annexed to Italy through Italy first encouraging the existing autonomist tendencies in Corsica and then the independence of Corsica from France, that would be followed by the annexation of Corsica into Italy.

In 1923, Mussolini temporarily occupied Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

, using irredentist claims based on minorities of Italians in the island, the Corfiot Italians. Similar tactics may have been used towards the islands around the Kingdom of Italy – through the pro-Italian Maltese, Corfiot Italians and Corsican Italians ''–'' in order to control the Mediterranean sea (his '' Mare Nostrum'', from the Latin "Our Sea").

During World War II, large parts of Dalmatia were annexed by Italy into the Governorship of Dalmatia

The Governorate of Dalmatia ( it, Governatorato di Dalmazia) was a territory divided into three provinces of Italy during the Italian Kingdom and Italian Empire epoch. It was created later as an entity in April 1941 at the start of World War I ...

from 1941 to 1943. Corsica and Nice were also administratively annexed by Italy in November 1942. Malta was heavily bombed, but was not occupied due to Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel () (15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944) was a German field marshal during World War II. Popularly known as the Desert Fox (, ), he served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of Nazi Germany, as well as servi ...

's request of diverting to North Africa the forces that had been prepared for the invasion of the island.

Dalmatia

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

in 1915 upon agreeing to the London Pact that guaranteed Italy the right to annex a large portion of Dalmatia in exchange for Italy's participation on the Allied side. From 5–6 November 1918, Italian forces were reported to have reached Vis, Lastovo, Šibenik, and other localities on the Dalmatian coast. By the end of hostilities in November 1918, the Italian military had seized control of the entire portion of Dalmatia that had been guaranteed to Italy by the London Pact and by 17 November had seized Fiume as well.Paul O'Brien. ''Mussolini in the First World War: the Journalist, the Soldier, the Fascist''. Oxford, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Berg, 2005. Pp. 17. In 1918, Admiral Enrico Millo

Enrico Millo (12 February 1865 – 14 June 1930) was an Italian admiral and politician. As a military commander, he led the raid against the Ottoman Navy in the Dardanelles.http://www.marina.difesa.it/palazzo/personaggi/millo.asp, Italian Navy we ...

declared himself Italy's Governor of Dalmatia. Famous Italian nationalist

Italian nationalism is a movement which believes that the Italians are a nation with a single homogeneous identity, and therefrom seeks to promote the cultural unity of Italy as a country. From an Italian nationalist perspective, Italianness is ...

Gabriele d'Annunzio supported the seizure of Dalmatia and proceeded to Zadar in an Italian warship in December 1918.

The last city with a significant Italian presence in Dalmatia was the city of Zara (now called Zadar). In the Austro-Hungarian census of 1910, the city of Zara had an Italian population of 9,318 (or 69.3% out of the total of 13,438 inhabitants). In 1921 the population grew to 17,075 inhabitants, of which 12,075 Italians (corresponding to 70,76%).

In 1941, during the Second World War, Yugoslavia was occupied by Italy and Germany. Dalmatia was divided between Italy, which constituted the Governorate of Dalmatia, and the Independent State of Croatia, which annexed Dubrovnik and Morlachia. After the

The last city with a significant Italian presence in Dalmatia was the city of Zara (now called Zadar). In the Austro-Hungarian census of 1910, the city of Zara had an Italian population of 9,318 (or 69.3% out of the total of 13,438 inhabitants). In 1921 the population grew to 17,075 inhabitants, of which 12,075 Italians (corresponding to 70,76%).

In 1941, during the Second World War, Yugoslavia was occupied by Italy and Germany. Dalmatia was divided between Italy, which constituted the Governorate of Dalmatia, and the Independent State of Croatia, which annexed Dubrovnik and Morlachia. After the Italian surrender

The Armistice of Cassibile was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 and made public on 8 September between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II.

It was signed by Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allies and Brig ...

(8 September 1943) the Independent State of Croatia annexed the Governorate of Dalmatia, except for the territories that had been Italian before the start of the conflict, such as Zara. In 1943, Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his deat ...

informed the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

that Zadar was a chief logistic centre for German forces in Yugoslavia. By overstating its importance, he persuaded them of its military significance. Italy surrendered in September 1943 and over the following year, specifically between 2 November 1943 and 31 October 1944, Allied Forces bombarded the town fifty-four times. Nearly 2,000 people were buried beneath rubble: 10–12,000 people escaped and took refuge in Trieste and slightly over 1,000 reached Apulia. Tito's partisans entered Zadar on 31 October 1944 and 138 people were killed. With the Peace Treaty of 1947, Italians still living in Zadar followed the Italian exodus from Dalmatia and only about 100 Dalmatian Italians now remain in the city.

Post-World War II

Under the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947,

Under the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947, Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

, Kvarner, most of the Julian March as well as the Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

n city of Zara was annexed by Yugoslavia causing the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus, which led to the emigration of between 230,000 and 350,000 of local ethnic Italians ( Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), the others being ethnic Slovenians, ethnic Croatians, and ethnic Istro-Romanians

The Istro-Romanians ( ruo, rumeri or ) are a Romance ethnic group native to or associated with the Istrian Peninsula. Historically, they inhabited vast parts of it, as well as the western side of the island of Krk until 1875. However, due to sev ...

, choosing to maintain Italian citizenship.

After World War II, Italian Irredentism diminished along with the defeated Fascists and the Monarchy of the House of Savoy

The House of Savoy ( it, Casa Savoia) was a royal dynasty that was established in 1003 in the historical Savoy region. Through gradual expansion, the family grew in power from ruling a small Alpine county north-west of Italy to absolute rule of ...

. After the Treaty of Paris (1947) and the Treaty of Osimo (1975), all territorial claims were abandoned by the Italian State (see Foreign relations of Italy). Today, Italy, France, Malta, Greece, Croatia and Slovenia are all members of the European Union, while Montenegro and Albania are candidates for accession.

The often cited the then-Italian Deputy Gianfranco Fini

Gianfranco Fini (born 3 January 1952) is an Italian politician who served as the president of the Italian Chamber of Deputies from 2008 to 2013. He is the former leader of the far-right Italian Social Movement, the conservative National Allianc ...

, who in Senigallia in 2004 gave an interview to the '' Slobodna Dalmacija'' daily newspaper at the 51st gathering of the Italians who left Yugoslavia after World War II, in which he was reported to have said: "From the son of an Italian from Fiume I learned that those areas were and are Italian, but not because at any particular historical moment our army planted Italians there. This country was Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

, and before that Roman". Rather than issuing an official rebuttal of those words, Carlo Giovanardi

Carlo Amedeo Giovanardi (born 15 January 1950, in Modena) is an Italian politician, former member of the Senate, and leader of the socially conservative wing of the New Centre-Right party.

Political career

Giovanardi graduated in jurisprude ...

, then Parliamentary Affairs Minister in Berlusconi's government, affirmed Fini's words by saying "that he told the truth".

These sources pointed out that on the 52nd gathering of the same association, in 2005, Carlo Giovanardi was quoted by the '' Večernji list'' daily newspaper as saying that Italy would launch a cultural, economic and touristic invasion in order to restore "the Italianness of Dalmatia" while participating in a roundtable discussion on the topic "Italy and Dalmatia today and tomorrow".NacionalTalijanski ministar najavio invaziju na Dalmaciju, Oct 19, 2005 ("Italian minister announced an invasion on Dalmatia") Giovanardi later declared that he had been misunderstood"Veleni nazionalisti sulla casa degli italiani" su Corriere della Sera del 21/10/2005

("Nationalist poisons on the house of Italians") archiviostampa.it and sent a letter to the Croatian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in which he condemned nationalism and ethnic strife. They underlined that Alleanza Nazionale (a former Italian conservative party) derived directly from the

Italian Social Movement

The Italian Social Movement ( it, Movimento Sociale Italiano, MSI) was a neo-fascist political party in Italy. A far-right party, it presented itself until the 1990s as the defender of Italian fascism's legacy, and later moved towards national ...

(MSI), a neo-fascist party. In 1994, Mirko Tremaglia, a member of the MSI and later of Alleanza Nazionale, described Rijeka, Istria and Dalmatia as "historically Italian" and referred to them as "occupied territories", saying that Italy should "tear up" the 1975 Treaty of Osimo with the former Yugoslavia and block Slovenia and Croatia's accession to European Union membership until the rights of their Italian minorities were respected.

In 2001, Italian president Carlo Azeglio Ciampi gave the gold medal (for the aerial bombings endured during World War II) to the last Italian administration of Zadar (Zara in Italian), represented by its Gonfalone, owned by the association "Free municipality of Zara in exile". Croatian authorities complained that he was awarding a fascist institution, even if the motivations for the golden medal explicitly recalled the contribution of the city to the Resistance

Resistance may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Comics

* Either of two similarly named but otherwise unrelated comic book series, both published by Wildstorm:

** ''Resistance'' (comics), based on the video game of the same title

** ''T ...

against Fascism. The motivations were contested by several Italian right-wing associations, such as the same "Free municipality of Zara in exile" and the Lega Nazionale.

On 12 December 2007, the Italian post office issued a stamp with a photo of the Croatian city of Rijeka

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Primor ...

and with the text "Fiume – eastern land once part of Italy" ("''Fiume-terra orientale già italiana''"). Some Croatian sources said that "''già italiana''" could also mean "already Italian", but according to Italian syntaxis the correct meaning, in this case, is only "previously Italian". 3.5 million copies of the stamp were printed, but it was not delivered by the Italian Post Office in order to forestall a possible diplomatic crisis with Croatian and Slovenian authorities. Nevertheless, some of the stamps leaked out and came in official use, and it became widely known.

Italian irredentism by region

*

* Italian irredentism in Dalmatia

Italian irredentism in Dalmatia was the political movement supporting the unification to Italy, during the 19th and 20th centuries, of Adriatic Dalmatia.

History

19th century

The Republic of Venice, between the 9th century and 1797, extended i ...

* Italian irredentism in Istria

The Italian irredentism in Istria was the political movement supporting the unification to Italy, during the 19th and 20th centuries, of the peninsula of Istria. It is considered closely related to the Italian irredentism in Trieste and Fiume, tw ...

* Italian irredentism in Corsica

Italian irredentism in Corsica was a cultural and historical movement promoted by Italians and by people from Corsica who identified themselves as part of Italy rather than France, and promoted the Italian annexation of the island.

History

Cor ...

* Italian irredentism in Nice

Italian irredentism in Nice was the political movement supporting the annexation of the County of Nice to the Kingdom of Italy.

According to some nationalism, Italian nationalists and Fascism, fascists like Ermanno Amicucci, Italian language, It ...

* Italian irredentism in Savoy

* Italian irredentism in Malta

Italian irredentism in Malta is the movement that uses an irredentist argument to propose the incorporation of the Maltese islands into Italy, with reference to past support in Malta for Italian territorial claims on the islands. Although Malta ...

* Italian irredentism in Switzerland

* Italian irredentism in Corfu

Political figures in Italian irredentism

*Guglielmo Oberdan

Guglielmo Oberdan, (born Wilhelm Oberdank) (February 1, 1858 - December 20, 1882) was an Italian irredentist. He was executed after a failed attempt to assassinate Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, becoming a martyr of the Italian unification movem ...

* Cesare Battisti

* Nazario Sauro

Nazario Sauro (20 September 1880 – 10 August 1916) was an Austrian-born Italian irredentist and sailor.

Life

Born in Capodistria, in what was then the Austrian Littoral (today Koper, Slovenia), he took to sailing from a very young age, a ...

* Carmelo Borg Pisani

* Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

* Gabriele D'Annunzio

* Petru Simone Cristofini

* Petru Giovacchini

* Maria Pasquinelli

Maria Pasquinelli (16 March 1913 – 3 July 2013) was an Italian people, Italian teacher and member of the Fascism in Italy, Fascist party convicted for the killing of United Kingdom, British General (military), Brigadier Robert de Winton in ...

Regions historically claimed by Italian irredentism

*Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

* Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

* Monaco

* Nice province

* Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

* Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

* Malta

* Ionian Islands

* Canton Ticino, parts of Canton Vallese and Italian Graubünden

* San Marino

* Coastal parts of Vlorë region and Vlorë

* Palagruža

See also

* Kingdom of Italy * Istrian-Dalmatian exodus * Istrian Italians * Dalmatian Italians * Niçard exodus * Niçard Italians * Italian Empire * Italian geographical region * Italian Regency of Carnaro *Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

References

Citations

Sources

* Bartoli, Matteo. ''Le parlate italiane della Venezia Giulia e della Dalmazia. Tipografia italo-orientale''. Grottaferrata. 1919. * Colonel von Haymerle, ''Italicae res'', Vienna, 1879 – the early history of irredentists. * Lovrovici, don Giovanni Eleuterio. ''Zara dai bombardamenti all'esodo (1943–1947)''. Tipografia Santa Lucia – Marino. Roma. 1974. * Petacco, Arrigo. ''A tragedy revealed: the story of Italians from Istria, Dalmatia, Venezia Giulia (1943–1953)''. University of Toronto Press. Toronto. 1998. * Večerina, Duško. ''Talijanski Iredentizam'' ("Italian Irredentism"). . Zagreb. 2001. * Vivante, Angelo. ''Irredentismo adriatico'' ("The Adriatic Irredentism"). 1984.External links

Unredeemed Italy (Google Books)

*

Movimento irredentista italiano

Italian irredentist movement *

Hrvati AMAC

Gdje su granice (EU-)talijanskog bezobrazluka? (''Where are the limits of Italian arrogancy?''; page contains the speech of Italian deputy) *

Slobodna Dalmacija

Počasni građanin Zadra kočnica talijanskoj ratifikaciji SSP-a *

D'Annunzio and Rijeka

*

Politicamentecorretto.com

Guglielmo Picchi Forza Italia *

Francobollo Fiume: bloccata l'emissione *

Trieste.rvnet.eu

Stoppato il francobollo per Fiume, bufera: protestano Unione degli istriani, An e Forza Italia (contains the scan of the stamp) {{DEFAULTSORT:Italian Irredentism * History of Austria-Hungary History of Istria History of Dalmatia History of Malta Politics of World War II Politics of World War I Italy de:Irredentismus#Italienischer Irredentismus