It's Not Necessarily Your Height It Could Be Your Feet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

English auxiliary verbs are a small set of English verbs, which include the English modal verbs and a few others. Although definitions vary, as generally conceived an auxiliary lacks inherent semantic meaning but instead modifies the meaning of another verb it accompanies. In English, verb forms are often classed as auxiliary on the basis of certain grammatical properties, particularly as regards their

The

The

Uncontracted Negatives and Negative Contractions in Contemporary English

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. p.23-28. They usually involve the

''Analyzing Syntax: A lexical-functional approach''

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. *Lewis, M. ''The English Verb 'An Exploration of Structure and Meaning' ''. Language Teaching Publications. *Osborne, T. and T. Groß 2012. Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets Dependency Grammar. ''Cognitive Linguistics'' 23, 1, 165–216. *Palmer, F. R., ''A Linguistic Study of the English Verb'', Longmans, 1965. *Radford. A. 1997

''Syntactic Theory and the Structure of English: A minimalist approach''

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. *Radford, A. 2004. ''English Syntax: An introduction''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. *Rowlett, P. 2007. ''The Syntax of French''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. *Sag, I. and T. Wasow. 1999. ''Syntactic Theory: A formal introduction''. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. *Tesnière, L. 1959. ''Élements de syntaxe structurale''. Paris: Klincksieck. *Warnant, L. 1982. ''Structure syntaxique du français''. Librairie Droz. *Warner, Anthony R., ''English Auxiliaries'', Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993.

syntax

In linguistics, syntax () is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure ( constituency) ...

. They also participate in subject–auxiliary inversion

Subject–auxiliary inversion (SAI; also called subject–operator inversion) is a frequently occurring type of inversion in English, whereby a finite auxiliary verb – taken here to include finite forms of the copula ''be'' – appears to "inve ...

and negation

In logic, negation, also called the logical complement, is an operation that takes a proposition P to another proposition "not P", written \neg P, \mathord P or \overline. It is interpreted intuitively as being true when P is false, and false ...

by the simple addition of ''not'' after them.

History of the concept

In English, the adjective ''auxiliary'' was "formerly applied to any formative or subordinate elements of language, e.g. prefixes, prepositions." As applied to verbs, its conception was originally rather vague and varied significantly.Some historical examples

The first English grammar, ''Pamphlet for Grammar'' by William Bullokar, published in 1586, does not use the term "auxiliary", but says,All other verbs are called verbs-neuters-un-perfect because they require the infinitive mood of another verb to express their signification of meaning perfectly: and be these, may, can, might or mought, could, would, should, must, ought, and sometimes, will, that being a mere sign of the future tense. (orthography has been modernized)In The life and opinions of Tristram Shandy, (1762) the narrator's father explains that "The verbs auxiliary we are concerned in here,..., are, ''am''; ''was''; ''have''; ''had''; ''do''; ''did''; ''make''; ''made''; ''suffer''; ''shall''; ''should''; ''will''; ''would''; ''can''; ''could''; ''owe''; ''ought''; ''used''; or ''is wont''." Wiseman's grammar from 1764 notes that most verbs

cannot be conjugated through all their Moods and Tenses, without one of the following principal Verbs ''have'' and ''be''. The first serves to conjugate the rest, by supplying the compound tenses of all Verbs both Regular and Irregular, whether Active, Passive, Neuter, or Impersonal, as may be seen in its own variation, &c.It goes on to include, along with ''have'' and ''be'', ''do'', ''may'', ''can'', ''shall'', ''will'' as auxiliary verbs. Fowler's grammar from 1857 has the following to say:

AUXILIARY VERBS, or ''Helping Verbs'', perform the same office in the conjugation of principal verbs which inflection does in the classical languages, though even in those languages the substantive verb is sometimes used as a helping verb... The verbs that are ''always auxiliary'' to others are, ''May'', ''can'', ''shall'', ''must'' '';'' II. Those that are ''sometimes auxiliary'' and sometimes principal verbs are, ''Will'', ''have'', ''do'', ''be'', and ''let''.The central core that each of these agree on are the modal auxiliary verbs ''may'', ''can'', and ''shall'', with most including also ''be'', ''do'', and ''have''.

Auxiliary verbs as heads

Modern grammars do not differ substantially in the list of auxiliary verbs, though they have refined the concept and often reconceptualized auxiliary verbs as theheads

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple animals may no ...

of a verb phrase, rather than as a subordinate element in it. This idea was first put forward by John Ross in 1969.

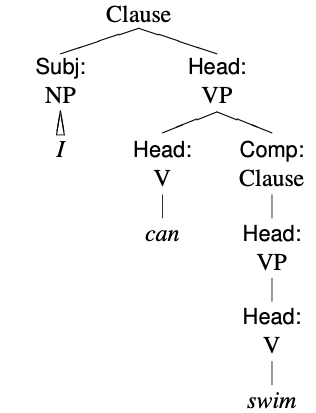

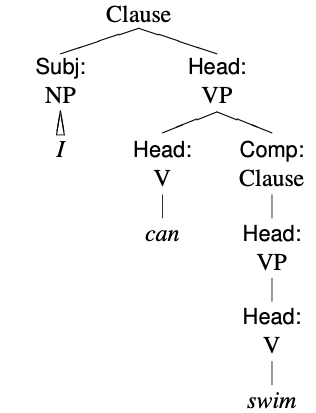

Many pedagogical grammars maintain the traditional idea that auxiliary verbs are subordinate elements, but many modern grammars such as '' The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language'' take auxiliaries to be heads. This is shown in the following tree diagram for the clause ''I can swim''.

The

The clause

In language, a clause is a constituent that comprises a semantic predicand (expressed or not) and a semantic predicate. A typical clause consists of a subject and a syntactic predicate, the latter typically a verb phrase composed of a verb with ...

has a subject noun phrase ''I'' and a head verb phrase, headed by the auxiliary verb ''can''. The VP also has a complement clause, which has a head VP, with the head verb ''swim''.

Auxiliary verbs vs lexical verbs

The list of auxiliary verbs in Modern English, along with their inflected forms, is shown in the following table. Some linguists consider membership in this syntactic class the defining property for English auxiliary verbs. The chief difference between this syntactic definition of "auxiliary verb" and the traditional definition given in the section above is that the syntactic definition includes forms of the verb ''be'' even when used simply as a copular verb (in sentences like ''I am hungry'' and ''It was a cat'') where it does not accompany any other verb. In Modern English, auxiliary verbs are distinguished from lexical verbs by the NICER properties, as shown in the following table.Negation

Every case of clausal negation requires an auxiliary verb. Up until Middle English, lexical verbs could also participate in clausal negation, so a clause like ''Lee eats not apples'' would have been grammatical, but this is not longer possible in Modern English.Inversion

Although English is a subject–verb–object language, there are cases where a verb comes before the subject. This is called subject-auxiliary inversion because only auxiliary verbs participate in such constructions. Again, in Middle English, lexical verbs were no different, but in Modern English ''*eats Lee apples'' is ungrammatical.Contraction of ''not''

Most English auxiliary verbs – but no lexical verbs – have a negative ''-n't'' morpheme. A small number ofdefective

Defective may refer to::

*Defective matrix, in algebra

*Defective verb, in linguistics

*Defective, or ''haser'', in Hebrew orthography, a spelling variant that does not include mater lectionis

*Something presenting an anomaly, such as a product de ...

auxiliaries verbs don't take this morpheme. The auxiliary ''may'' never takes this morpheme. ''Am'' becomes ''ain't'' only in non-standard English

In an English-speaking country, Standard English (SE) is the variety of English that has undergone substantial regularisation and is associated with formal schooling, language assessment, and official print publications, such as public service a ...

varieties; otherwise it has no negative form. Also, ''will'' has an irregular negative ''won't'' instead of the expected ''*willn't'' and ''shall'' has an irregular negative ''shan't'' instead of the expected (and now archaic) ''*shalln't''.

Ellipsis

In a typical case, an auxiliary verb takes a non-finite clause complement. But this can be elided, as in the example above. Lexical verbs taking a non-finite clause complement don't allow this kind of ellipsis.Rebuttal

When two people are arguing, the second may deny a statement made by the first by using a stressed ''too'' or ''so''. For example, having been told that they didn't do their homework, a child may reply ''I did too''. This kind of rebuttal is impossible with lexical verbs.The case of ''to''

Various linguists, including Geoff Pullum, Paul Postal and Richard Hudson, and Robert Fiengohas have suggested that ''to'' in cases like ''I want to go'' (not thepreposition

Prepositions and postpositions, together called adpositions (or broadly, in traditional grammar, simply prepositions), are a class of words used to express spatial or temporal relations (''in'', ''under'', ''towards'', ''before'') or mark various ...

''to'') is a special case of an auxiliary verb with a no tensed forms. Rodney Huddleston argues against this position in '' The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language'', but Robert Levine counters these proposals. BetteLou Los calls Pullum's arguments that ''to'' is an auxiliary verb"compelling".

In terms of the NICER properties, examples like ''it's fine to not go'' shows that it allows negation. Inversion, contraction of ''not'', and rebuttal would only apply to tensed forms, and ''to'' is argued to have none. It does allows ellipsis though: ''I don't want to'', but rebuttal is not possible.

Auxiliaries as helping verbs

An auxiliary is traditionally understood as a verb that "helps" another verb by adding (only) grammatical information to it. On this basis, English auxiliaries include: *forms of the verb ''do'' (''do'', ''does'', ''did'') when used with another verb to form questions, negation, emphasis, etc. (see ''do''-support); *forms of the verb ''have'' (''have'', ''has'', ''had'') when used to express perfect aspect; *forms of the verb ''be'' (''am'', ''are'', ''is'', ''was'', ''were'') when used to express progressive aspect or passive voice; *the modal verbs, used in a variety of meanings, principally relating to modality. The following are examples of sentences containing the above types of auxiliary verbs: ::Do you want tea? – ''do'' is an auxiliary accompanying the verb ''want'', used here to form a question. ::He had given his all. – ''had'' is an auxiliary accompanying thepast participle

In linguistics, a participle () (from Latin ' a "sharing, partaking") is a nonfinite verb form that has some of the characteristics and functions of both verbs and adjectives. More narrowly, ''participle'' has been defined as "a word derived from ...

''given'', expressing perfect aspect.

::We are singing. – ''are'' is an auxiliary accompanying the present participle ''singing'', expressing progressive aspect.

::It was destroyed. – ''was'' is an auxiliary accompanying the past participle ''destroyed'', expressing passive voice.

::He can do it now. – ''can'' is a modal auxiliary accompanying the verb ''do''.

However, the above understanding of auxiliaries is not the only one in the literature, particularly in the case of forms of the verb ''be'', which may be called auxiliary even when not accompanying another verb. Other approaches to defining auxiliary verbs are described below.

Auxiliaries as verbs with special grammatical behavior

A group of English verbs with certain special grammatical (syntactic

In linguistics, syntax () is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure (constituency), ...

) properties distinguishes them from other verbs. This group consists mainly of verbs that are auxiliaries in the above sense – verbs that add purely grammatical meaning to other verbs – and thus some authors use the term "auxiliary verb" to denote precisely the verbs in this group. However, not all enumerations of English auxiliary verbs correspond exactly to the group of verbs having these grammatical properties. This group of verbs may also be referred to by other names, such as "special verbs".

Non-indicative and non-finite forms of the same verbs (when performing the same functions) are usually described as auxiliaries too, even though all or most of the distinctive syntactical properties do not apply to them specifically: ''be'' (as infinitive, imperative and subjunctive), ''being'' and ''been''; when used in the expression of perfect aspect, ''have'' (as infinitive), ''having'' and ''had'' (as past participle).

Sometimes, non-auxiliary uses of ''have'' follow auxiliary syntax, as in ''Have you any ideas?'' and ''I haven't a clue''. Other lexical verbs do not do this in modern English, although they did so formerly, and such uses as ''I know not...'' can be found in archaic English.

Meaning contribution

Forms of the verbs ''have'' and ''be'', used as auxiliaries with a main verb'spast participle

In linguistics, a participle () (from Latin ' a "sharing, partaking") is a nonfinite verb form that has some of the characteristics and functions of both verbs and adjectives. More narrowly, ''participle'' has been defined as "a word derived from ...

and present participle respectively, express perfect aspect and progressive aspect. When forms of ''be'' are used with the past participle, they express passive voice. It is possible to combine any two or all three of these uses:

::The room has been being cleaned for the past three hours.

Here the auxiliaries ''has'', ''been'' and ''being'' (each followed by the appropriate participle type) combine to express perfect and progressive aspect and passive voice.

The auxiliary ''do'' (''does'', ''did'') does not typically contribute any meaning (semantic or grammatical), except when used to add emphasis to an accompanying verb. This is called the emphatic mood in English: An example would be "I do go to work on time every day" (with intonational stress placed on ''do''), compared to "I go to work on time every day." As an auxiliary, ''do'' mainly helps form questions, negations, etc., as described in the article on ''do''-support.

Other auxiliaries – the modal verbs – contribute meaning chiefly in the form of modality, although some of them (particularly ''will'' and sometimes ''shall'') express future time reference. Their uses are detailed at English modal verbs, and tables summarizing their principal meaning contributions can be found in the articles Modal verb and Auxiliary verb.

For more details on the uses of auxiliaries to express aspect, mood and time reference, see English clause syntax

This article describes the syntax of clauses in the English language, chiefly in Modern English. A clause is often said to be the smallest grammatical unit that can express a complete proposition. But this semantic idea of a clause leaves out ...

.

Contracted forms

Contraction

Contraction may refer to:

Linguistics

* Contraction (grammar), a shortened word

* Poetic contraction, omission of letters for poetic reasons

* Elision, omission of sounds

** Syncope (phonology), omission of sounds in a word

* Synalepha, merged ...

s are a common feature of English, used frequently in ordinary speech. In written English, contractions are used in mostly informal writing and sometimes in formal writing.Castillo González, Maria del PilarUncontracted Negatives and Negative Contractions in Contemporary English

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. p.23-28. They usually involve the

elision

In linguistics, an elision or deletion is the omission of one or more sounds (such as a vowel, a consonant, or a whole syllable) in a word or phrase. However, these terms are also used to refer more narrowly to cases where two words are run toget ...

of a vowel – an apostrophe

The apostrophe ( or ) is a punctuation mark, and sometimes a diacritical mark, in languages that use the Latin alphabet and some other alphabets. In English, the apostrophe is used for two basic purposes:

* The marking of the omission of one o ...

being inserted in its place in written English – possibly accompanied by other changes. Many of these contractions involve auxiliary verbs and their negations, although not all of these have common contractions, and there are also certain other contractions not involving these verbs.

Contractions were first used in speech during the early 17th century and in writing during the mid 17th century when ''not'' lost its stress and tone and formed the contraction ''-n't''. Around the same time, contracted auxiliaries were first used. When it was first used, it was limited in writing to only fiction and drama. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the use of contractions in writing spread outside of fiction such as personal letters, journalism, and descriptive texts.

Certain contractions tend to be restricted to less formal speech and very informal writing, such as ''John'd'' or ''Mary'd'' for "John/Mary would" (compare the personal pronoun forms ''I'd'' and ''you'd'', which are much more likely to be encountered in relatively informal writing). This applies in particular to constructions involving consecutive contractions, such as ''wouldn't've'' for "would not have".

Contractions in English are generally not mandatory as in some other languages. It is almost always acceptable to use the uncontracted form, although in speech this may seem overly formal. This is often done for emphasis: ''I am ready!'' The uncontracted form of an auxiliary or copula must be used in elliptical sentences where its complement is omitted: ''Who's ready? I am!'' (not *''I'm!'').

Some contractions lead to homophony, which sometimes causes errors in writing. Confusion is particularly common between ''it's'' (for "it is/has") and the pronoun possessive ''its'', and sometimes similarly between ''you're'' and ''your''. For the confusion of ''have'' or -''Ltd.

A private company limited by shares is a class of private limited company incorporated under the laws of England and Wales, Northern Ireland, Scotland, certain Commonwealth countries, and the Republic of Ireland. It has shareholders with limit ...

'' for "Limited (company)". Contraction-like abbreviations, such as ''int'l'' for ''international'', are considered abbreviations as their contracted forms cannot be pronounced in speech. Abbreviations also include acronyms and initialisms

An acronym is a word or name formed from the initial components of a longer name or phrase. Acronyms are usually formed from the initial letters of words, as in ''NATO'' (''North Atlantic Treaty Organization''), but sometimes use syllables, as ...

.

Negative form of ''am''

Although there is no contraction for ''am not'' in standard English, there are certain colloquial or dialectal forms that may fill this role. These may be used in declarative sentences, whose standard form contains ''I am not'', and in questions, with standard form ''am I not?'' In the declarative case the standard contraction ''I'm not'' is available, but this does not apply in questions, where speakers may feel the need for a negative contraction to form the analog of ''isn't it'', ''aren't they'', etc. (see below). The following are sometimes used in place of ''am not'' in the cases described above: *The contraction ''ain't'' may stand for ''am not'', among its other uses. For details see the next section, and the separate article on ''ain't

The word "ain't" is a contraction for ''am not'', ''is not'', ''are not'', ''has not'', ''have not'' in the common English language vernacular. In some dialects ''ain't'' is also used as a contraction of ''do not'', ''does not'' and ''did not''. ...

''.

*The word ''amnae'' for "am not" exists in Scots

Scots usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

* Scots language, a language of the West Germanic language family native to Scotland

* Scots people, a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland

* Scoti, a Latin na ...

, and has been borrowed into Scottish English by many speakers.It is used in declarative sentences rather than questions.

*The contraction ''amn't'' (formed in the regular manner of the other negative contractions, as described above) is a standard contraction of ''am not'' in some varieties, mainly Hiberno-English

Hiberno-English (from Latin ''Hibernia'': "Ireland"), and in ga, Béarla na hÉireann. or Irish English, also formerly Anglo-Irish, is the set of English dialects native to the island of Ireland (including both the Republic of Ireland a ...

(Irish English) and Scottish English. In Hiberno-English the question form (''amn't I?'') is used more frequently than the declarative ''I amn't''. (The standard ''I'm not'' is available as an alternative to ''I amn't'' in both Scottish English and Hiberno-English.) An example appears in Oliver St. John Gogarty

Oliver Joseph St. John Gogarty (17 August 1878 – 22 September 1957) was an Irish poet, author, otolaryngologist, athlete, politician, and well-known conversationalist. He served as the inspiration for Buck Mulligan in James Joyce's novel ...

's impious poem '' The Ballad of Japing Jesus'': "If anyone thinks that I amn't divine, / He gets no free drinks when I'm making the wine". These lines are quoted in James Joyce's ''Ulysses

Ulysses is one form of the Roman name for Odysseus, a hero in ancient Greek literature.

Ulysses may also refer to:

People

* Ulysses (given name), including a list of people with this name

Places in the United States

* Ulysses, Kansas

* Ulysse ...

'', which also contains other examples: "Amn't I with you? Amn't I your girl?" (spoken by Cissy Caffrey to Leopold Bloom in Chapter 15).

*The contraction ''aren't'', which in standard English represents ''are not'', is a very common means of filling the "amn't gap" in questions: ''Aren't I lucky to have you around?'' Some twentieth-century writers described this usage as "illiterate" or awkward; today, however, it is reported to be "almost universal" among speakers of Standard English. ''Aren't'' as a contraction for ''am not'' developed from one pronunciation of "an't" (which itself developed in part from "amn't"; see the etymology of "ain't" in the following section). In non-rhotic

Rhoticity in English is the pronunciation of the historical rhotic consonant by English speakers. The presence or absence of rhoticity is one of the most prominent distinctions by which varieties of English can be classified. In rhotic varieti ...

dialects, "aren't" and this pronunciation of "an't" are homophone

A homophone () is a word that is pronounced the same (to varying extent) as another word but differs in meaning. A ''homophone'' may also differ in spelling. The two words may be spelled the same, for example ''rose'' (flower) and ''rose'' (p ...

s, and the spelling "aren't I" began to replace "an't I" in the early part of the 20th century, although examples of "aren't I" for "am I not" appear in the first half of the 19th century, as in "St. Martin's Day", from ''Holland-tide'' by Gerald Griffin, published in ''The Ant'' in 1827: "aren't I listening; and isn't it only the breeze that's blowing the sheets and halliards about?"

There is therefore no completely satisfactory first-person equivalent to ''aren't you?'' and ''isn't it?'' in standard English. The grammatical ''am I not?'' sounds stilted or affected, while ''aren't I?'' is grammatically dubious, and ''ain't I?'' is considered substandard. Nonetheless, ''aren't I?'' is the solution adopted in practice by most speakers.

Other colloquial contractions

''Ain't'' (described in more detail in the article ''ain't

The word "ain't" is a contraction for ''am not'', ''is not'', ''are not'', ''has not'', ''have not'' in the common English language vernacular. In some dialects ''ain't'' is also used as a contraction of ''do not'', ''does not'' and ''did not''. ...

'') is a colloquialism and contraction for "am not", "is not", "was not" "are not", "were not" "has not", and "have not". In some dialects "ain't" is also used as a contraction of "do not", "does not", "did not", "cannot/can not", "could not", "will not", "would not" and "should not". The usage of "ain't" is a perennial subject of controversy in English.

"Ain't" has several antecedents in English, corresponding to the various forms of "to be not" and "to have not".

"An't" (sometimes "a'n't") arose from "am not" (via "amn't") and "are not" almost simultaneously. "An't" first appears in print in the work of English Restoration playwrights. In 1695 "an't" was used as a contraction of "am not", and as early as 1696 "an't" was used to mean "are not". "An't" for "is not" may have developed independently from its use for "am not" and "are not". "Isn't" was sometimes written as "in't" or "en't", which could have changed into "an't". "An't" for "is not" may also have filled a gap as an extension of the already-used conjugations for "to be not".

"An't" with a long "a" sound began to be written as "ain't", which first appears in writing in 1749. By the time "ain't" appeared, "an't" was already being used for "am not", "are not", and "is not". "An't" and "ain't" coexisted as written forms well into the nineteenth century.

"Han't" or "ha'n't", an early contraction for "has not" and "have not", developed from the elision of the "s" of "has not" and the "v" of "have not". "Han't" also appeared in the work of English Restoration playwrights. Much like "an't", "han't" was sometimes pronounced with a long "a", yielding "hain't". With H-dropping, the "h" of "han't" or "hain't" gradually disappeared in most dialects, and became "ain't". "Ain't" as a contraction for "has not"/"have not" appeared in print as early as 1819. As with "an't", "hain't" and "ain't" were found together late into the nineteenth century.

Some other colloquial and dialect contractions are described below:

*"Bain't" or "bain't", apparently a contraction of "be not", is found in a number of works employing eye dialect, including J. Sheridan Le Fanu's '' Uncle Silas''. It is also found in a ballad written in Newfoundland dialect.

*"Don't" is a standard English contraction of "do not". However, for some speakers "don't" also functions colloquially as a contraction of "does not": ''Emma? She don't live here anymore.'' This is considered incorrect in standard English.

*"Hain't", in addition to being an antecedent of "ain’t", is a contraction of "has not" and "have not" in some dialects of English, such as Appalachian English. It is reminiscent of "hae" ("have") in Lowland Scots. In dialects that retain the distinction between "hain't" and "ain't", "hain't" is used for contractions of "to have not" and "ain't" for contractions of "to be not".

In other dialects, "hain't" is used either in place of, or interchangeably with "ain't". "Hain't" is seen for example in Chapter 33 of Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

's '' The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'': ''I hain't come back—I hain't been GONE.'' ("Hain't" is to be distinguished from "haint", a slang term for ghost

A ghost is the soul or spirit of a dead person or animal that is believed to be able to appear to the living. In ghostlore, descriptions of ghosts vary widely from an invisible presence to translucent or barely visible wispy shapes, to rea ...

(i.e., a "haunt"), famously used in the novel '' To Kill a Mockingbird''.)

Contractions and inversion

In cases ofsubject–auxiliary inversion

Subject–auxiliary inversion (SAI; also called subject–operator inversion) is a frequently occurring type of inversion in English, whereby a finite auxiliary verb – taken here to include finite forms of the copula ''be'' – appears to "inve ...

, particularly in the formation of questions, the negative contractions can remain together as a unit and invert with the subject, thus acting as if they were auxiliary verbs in their own right. For example:

::He is going. → Is he going? (regular affirmative question formation)

::He isn't going. → Isn't he going? (negative question formation; ''isn't'' inverts with ''he'')

One alternative is not to use the contraction, in which case only the verb inverts with the subject, while the ''not'' remains in place after it:

::He is not going. → Is he not going?

Note that the form with ''isn't he'' is no longer a simple contraction of the fuller form (which must be ''is he not'', and not *''is not he'').

Another alternative to contract the auxiliary with the subject, in which case inversion does not occur at all:

::He's not going. → He's not going?

Some more examples:

::Why haven't you washed? / Why have you not washed?

::Can't you sing? / Can you not sing? (the full form ''cannot'' is redivided in case of inversion)

::Where wouldn't they look for us? / Where would they not look for us?

The contracted forms of the questions are more usual in informal English. They are commonly found in tag questions. For the possibility of using ''aren't I'' (or other dialectal alternatives) in place of the uncontracted ''am I not'', see Contractions representing ''am not'' above.

The same phenomenon sometimes occurs in the case of negative inversion:

::Not only doesn't he smoke, ... / Not only does he not smoke, ...

Notes

References

*Adger, D. 2003. ''Core Syntax''. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. *Allerton, D. 2006. Verbs and their Satellites. In ''Handbook of English Linguistics''. Aarts & MacMahon (eds.). Blackwell. *Bresnan, J. 2001. ''Lexical-Functional Syntax''. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. *Crystal, D. 1997. ''A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics'', 4th edition. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers. *Culicover, P. 2009. ''Natural Language Syntax''. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. *Engel, U. 1994. ''Syntax der deutschen Sprache'', 3rd edition. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag. *Eroms, H.-W. 2000. ''Syntax der deutschen Sprache''. Berlin: de Gruyter. *Finch, G. 2000. ''Linguistic Terms and Concepts''. New York: St. Martin's Press. *''Fowler's Modern English Usage''. 1996. Revised third edition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. *Jurafsky, D. and J. Martin. 2000. ''Speech and Language Processing''. Dorling Kindersley (India): Pearson Education, Inc. / Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009. *Kroeger, P. 2004''Analyzing Syntax: A lexical-functional approach''

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. *Lewis, M. ''The English Verb 'An Exploration of Structure and Meaning' ''. Language Teaching Publications. *Osborne, T. and T. Groß 2012. Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets Dependency Grammar. ''Cognitive Linguistics'' 23, 1, 165–216. *Palmer, F. R., ''A Linguistic Study of the English Verb'', Longmans, 1965. *Radford. A. 1997

''Syntactic Theory and the Structure of English: A minimalist approach''

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. *Radford, A. 2004. ''English Syntax: An introduction''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. *Rowlett, P. 2007. ''The Syntax of French''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. *Sag, I. and T. Wasow. 1999. ''Syntactic Theory: A formal introduction''. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. *Tesnière, L. 1959. ''Élements de syntaxe structurale''. Paris: Klincksieck. *Warnant, L. 1982. ''Structure syntaxique du français''. Librairie Droz. *Warner, Anthony R., ''English Auxiliaries'', Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993.

External links

{{Wiktionary category, category = English auxiliary verbs, type = Auxiliary verbs Auxiliary Slang English modal and auxiliary verbs