Israel–Syria border on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The modern borders of Israel exist as the result both of past wars and of diplomatic agreements between the

The modern borders of Israel exist as the result both of past wars and of diplomatic agreements between the

The modern borders of Israel exist as the result both of past wars and of diplomatic agreements between the

The modern borders of Israel exist as the result both of past wars and of diplomatic agreements between the State of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

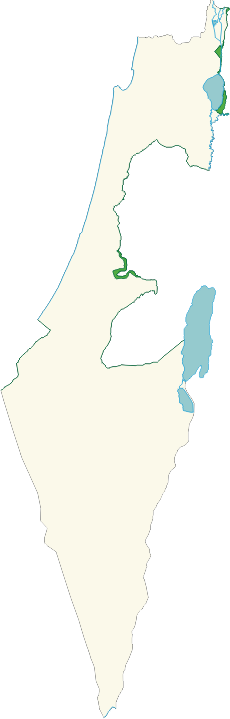

and its neighbours as well as colonial powers. Only two of Israel's five total potential land borders are internationally recognized and uncontested, while the other three remain disputed; the majority of its border disputes are rooted in territorial changes that came about as a result of the 1967 Arab–Israeli War, which saw Israel occupy large swathes of territory from its rivals. Israel's two formally recognized and confirmed borders exist with Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

since the 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty and the 1994 Israel–Jordan peace treaty, while its borders with Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

(via the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights

The Golan Heights ( ar, هَضْبَةُ الْجَوْلَانِ, Haḍbatu l-Jawlān or ; he, רמת הגולן, ), or simply the Golan, is a region in the Levant spanning about . The region defined as the Golan Heights differs between di ...

), Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

(via the Blue Line; see Shebaa Farms dispute) and the Palestinian territories

The Palestinian territories are the two regions of the former British Mandate for Palestine that have been militarily occupied by Israel since the Six-Day War of 1967, namely: the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip. The I ...

(Israeli-occupied land largely recognized as part of the ''de jure'' State of Palestine

Palestine ( ar, فلسطين, Filasṭīn), Legal status of the State of Palestine, officially the State of Palestine ( ar, دولة فلسطين, Dawlat Filasṭīn, label=none), is a state (polity), state located in Western Asia. Officiall ...

) remain internationally recognized as contested.Sela, Avraham. "Israel." ''The Continuum Political Encyclopedia of the Middle East''. Ed. Sela. New York: Continuum, 2002. pp. 444-474

According to the Green Line agreed upon in the 1949 Armistice Agreements

The 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel and Egypt, demarcated by Lebanon to the north, the Golan Heights under Syrian sovereignty as well as the rest of Syria to the northeast, the Palestinian West Bank and

The

The

Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

to the east, and by the Palestinian Gaza Strip and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

to the southwest. The Israeli border with Egypt is the international border demarcated in 1906 between the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, and confirmed in the 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty; the Israeli border with Jordan is based on the border defined in the 1922 Trans-Jordan memorandum, and confirmed in the 1994 Israel–Jordan peace treaty.

Early background

The

The Sykes–Picot Agreement

The Sykes–Picot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy, to define their mutually agreed Sphere of influence, spheres of influence and control in a ...

of 1916 secretly divided the Ottoman Empire lands of Middle East between British and French spheres of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

. They agreed that "Palestine" was to be designated as an "international enclave". This agreement was revised by Britain and France in December 1918; it was agreed that Palestine and the Vilayet of Mosul in modern-day Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

would be part of the British sphere in exchange for British support of French influence in Syria and Lebanon. At the San Remo Conference

The San Remo conference was an international meeting of the post-World War I Allied Supreme Council as an outgrowth of the Paris Peace Conference, held at Villa Devachan in Sanremo, Italy, from 19 to 26 April 1920. The San Remo Resolution pas ...

(April 19–26, 1920) the Allied Supreme Council determined that mandates for Palestine and Mesopotamia would be allocated to Britain without precisely defining the boundaries of the mandated territories.

Border with Jordan

British Mandate

In March 1921, the Colonial SecretaryWinston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

visited Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and following a discussion with Emir Abdullah

AbdullahI bin Al-Hussein ( ar, عبد الله الأول بن الحسين, translit=Abd Allāh al-Awwal bin al-Husayn, 2 February 1882 – 20 July 1951) was the ruler of Jordan from 11 April 1921 until his assassination in 1951. He was the Emir ...

, it was agreed that Transjordan was to be added to the proposed Palestine Mandate, but that the Jewish National Home

A homeland for the Jewish people is an idea rooted in Jewish history, religion, and culture. The Jewish aspiration to return to Zion, generally associated with divine redemption, has suffused Jewish religious thought since the destruction o ...

objective for the proposed Palestine Mandate would not apply to the territory.

In July 1922, the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

approved the Palestine Mandate, which came into effect in 1923 after a dispute between France and Italy over the Syria Mandate was settled. The Mandate stated that Britain could 'postpone or withhold' application of the provisions dealing with the 'Jewish National Home' in the territory east of the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

, then called Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

. In September 1922, following Abdullah's probation period, the British government presented a memorandum to the League of Nations defining the border of Transjordan and confirming its exclusion from all the provisions dealing with Jewish settlement.

Historian and political scientist Adam Garfinkle writes that the public clarification and implementation of Article 25, more than a year after its addition to the Mandate, misled some "into imagining that Transjordanian territory was covered by the conditions of the Mandate as to the Jewish National Home before August 1921". This would, according to professor of modern Jewish history Bernard Wasserstein

Bernard Wasserstein (born 22 January 1948 in London) is a British historian.

Early life

Bernard Wasserstein was born in London on 22 January 1948. Wasserstein's father, Abraham Wasserstein (1921–1995), born in Frankfurt, was Professor of Class ...

, result in "the myth of Palestine's 'first partition' hich becamepart of the concept of 'Greater Israel' and of the ideology of Jabotinsky's Revisionist movement". Palestinian-American academic Ibrahim Abu-Lughod

Ibrahim Abu-Lughod ( ar, إبراهيم أبو لغد, February 15, 1929 – May 23, 2001) was a Palestinian (later American) academic, characterised by Edward Said as "Palestine's foremost academic and intellectual"Said 2001 and by Rashid Khalid ...

, then chair of the Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

political science department, suggested that the "Jordan as a Palestinian State" references made by Israeli spokespeople may reflect "the same isnderstanding".

Independence

Transjordan gained independence from Britain in 1946 within the above borders, prior to the termination of Mandatory Palestine . On 15 May 1948, the TransjordanianArab Legion

The Arab Legion () was the police force, then regular army of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate, in the early part of the 20th century, and then of independent Jordan, with a final Arabization of its command taking place in 195 ...

entered from the east what had been the Palestinian part of the Palestinian Mandate, while other Arab armies invaded other parts of the territory. The 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

was brought to an end by the Lausanne Conference of 1949 at which the 1949 Armistice Agreements

The 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel and Egypt,Green Line, and was expressly declared to be a temporary

The

The

Also Louis, 1969, p. 90. several months before Britain and France assumed their Mandatory responsibilities on September 29, 1923. In accordance with the same process, a nearby parcel of land that included the ancient site of In 1923, an agreement between the United Kingdom and France, known as the

In 1923, an agreement between the United Kingdom and France, known as the

demarcation line

{{Refimprove, date=January 2008

A political demarcation line is a geopolitical border, often agreed upon as part of an armistice or ceasefire.

Africa

* Moroccan Wall, delimiting the Moroccan-controlled part of Western Sahara from the Sahrawi- ...

, rather than a permanent border, and the Armistice Agreements relegated the issue of permanent borders to future negotiations. After the armistice, Transjordan was in control of what came to be called the West Bank. East Jerusalem, including the Old City, was considered part of the West Bank.

The West Bank was annexed by Jordan in 1950,In the ''Act of Union'', 1950. with the border being the 1949 armistice line, though Jordan laid claim to all of Mandate Palestine. Jordan's annexation was only recognised by three countries. The West Bank remained part of Jordan until Israel captured it in 1967, during the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

, though Jordan continued to claim the territory as its own after that date. In July 1988, Jordan renounced all claims to the West Bank, in favour of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation, as the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people".

The Israel–Jordan peace treaty

The Israel–Jordan peace treaty (formally the "Treaty of Peace Between the State of Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan"), he, הסכם השלום בין ישראל לירדן; transliterated: ''Heskem Ha-Shalom beyn Yisra'el Le-Yarden'' ...

, signed on 26 October 1994, resolved all outstanding territorial and border issues between the two countries that had existed since the 1948 War. The treaty specified and fully recognized the international border between Israel and Jordan, with Jordan confirming its renunciation of any claim to the West Bank. Upon its signing, the Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

and Yarmouk River

The Yarmuk River ( ar, نهر اليرموك, translit=Nahr al-Yarmūk, ; Greek: Ἱερομύκης, ; la, Hieromyces or ''Heromicas''; sometimes spelled Yarmouk), is the largest tributary of the Jordan River. It runs in Jordan, Syria and Israel ...

s, the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea ( he, יַם הַמֶּלַח, ''Yam hamMelaḥ''; ar, اَلْبَحْرُ الْمَيْتُ, ''Āl-Baḥrū l-Maytū''), also known by other names, is a salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east and Israel and the West Bank ...

, the Emek Ha'arva/Wadi Araba and the Gulf of Aqaba

The Gulf of Aqaba ( ar, خَلِيجُ ٱلْعَقَبَةِ, Khalīj al-ʿAqabah) or Gulf of Eilat ( he, מפרץ אילת, Mifrátz Eilát) is a large gulf at the northern tip of the Red Sea, east of the Sinai Peninsula and west of the Arabian ...

were officially designated as the borders between Israel and Jordan and between Jordan and the territory occupied by Israel in 1967. For the latter, the agreement requires that the demarcation use a different presentation, and that it carry the following disclaimer: "This line is the administrative boundary between Jordan and the territory which came under Israeli military government control in 1967. Any treatment of this line shall be without prejudice to the status of the territory."

Border with Syria and Lebanon

French Mandate: Paulet–Newcombe Agreement

The

The Paulet–Newcombe Agreement

The Paulet–Newcombe Agreement or Paulet-Newcombe Line, was a 1923 agreement between the British and French governments regarding the position and nature of the boundary between the Mandates of Palestine and Iraq, attributed to Great Britain, a ...

, a series of agreements between 1920 and 1923, contained the principles for the boundary between the Mandates of Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, attributed to Great Britain, and the Mandate of Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

and the Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

, attributed to France.

A 1920 agreement defined the boundary between the forthcoming British and French mandates in broad terms,Text available in ''American Journal of International Law'', Vol. 16, No. 3, 1922, 122–126. and placed the bulk of the Golan Heights in the French sphere. The agreement also established a joint commission to settle the border and mark it on the ground. The commission submitted its final report on February 3, 1922, and it was approved with some caveats by the British and French governments on March 7, 1923,Agreement between His Majesty's Government and the French Government respecting the Boundary Line between Syria and Palestine from the Mediterranean to El Hámmé, Treaty Series No. 13 (1923), Cmd. 1910.Also Louis, 1969, p. 90. several months before Britain and France assumed their Mandatory responsibilities on September 29, 1923. In accordance with the same process, a nearby parcel of land that included the ancient site of

Dan

Dan or DAN may refer to:

People

* Dan (name), including a list of people with the name

** Dan (king), several kings of Denmark

* Dan people, an ethnic group located in West Africa

**Dan language, a Mande language spoken primarily in Côte d'Ivoir ...

was transferred from Syria to Palestine early in 1924. In this way the Golan Heights became part of the French Mandate of Syria

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (french: Mandat pour la Syrie et le Liban; ar, الانتداب الفرنسي على سوريا ولبنان, al-intidāb al-fransi 'ala suriya wa-lubnān) (1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate foun ...

. When the French Mandate of Syria ended in 1944, the Golan Heights remained part of the newly independent state of Syria.

Paulet–Newcombe Agreement

The Paulet–Newcombe Agreement or Paulet-Newcombe Line, was a 1923 agreement between the British and French governments regarding the position and nature of the boundary between the Mandates of Palestine and Iraq, attributed to Great Britain, a ...

, established the border between the soon-to-be formalised territories covered by the British Mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan, both of which had been conceded by the Ottoman Empire following the end of World War I in 1918. The manda ...

and the French Mandate for Syria

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (french: Mandat pour la Syrie et le Liban; ar, الانتداب الفرنسي على سوريا ولبنان, al-intidāb al-fransi 'ala suriya wa-lubnān) (1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate foun ...

. The British handed over the southern Golan Heights to the French in return for the northern Jordan Valley

The Jordan Valley ( ar, غور الأردن, ''Ghor al-Urdun''; he, עֵמֶק הַיַרְדֵּן, ''Emek HaYarden'') forms part of the larger Jordan Rift Valley. Unlike most other river valleys, the term "Jordan Valley" often applies just to ...

. The border was drawn so that both sides of the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

and the whole of the Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee ( he, יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ar, بحيرة طبريا), also called Lake Tiberias, Kinneret or Kinnereth, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest ...

, including a 10-metre-wide strip along the northeastern shore, were part of Palestine.

Syria: subsequent changes

The1947 UN Partition Plan

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as Re ...

allocated this territory to the Jewish state. Following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

, Syria seized some land that had been allocated to the Jewish state and under the 1949 Armistice Agreements

The 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel and Egypt,'' The Missing Peace - The Inside Story of the Fight for Middle East Peace'' (2004), by

On March 14, 1978, Israel launched

On March 14, 1978, Israel launched

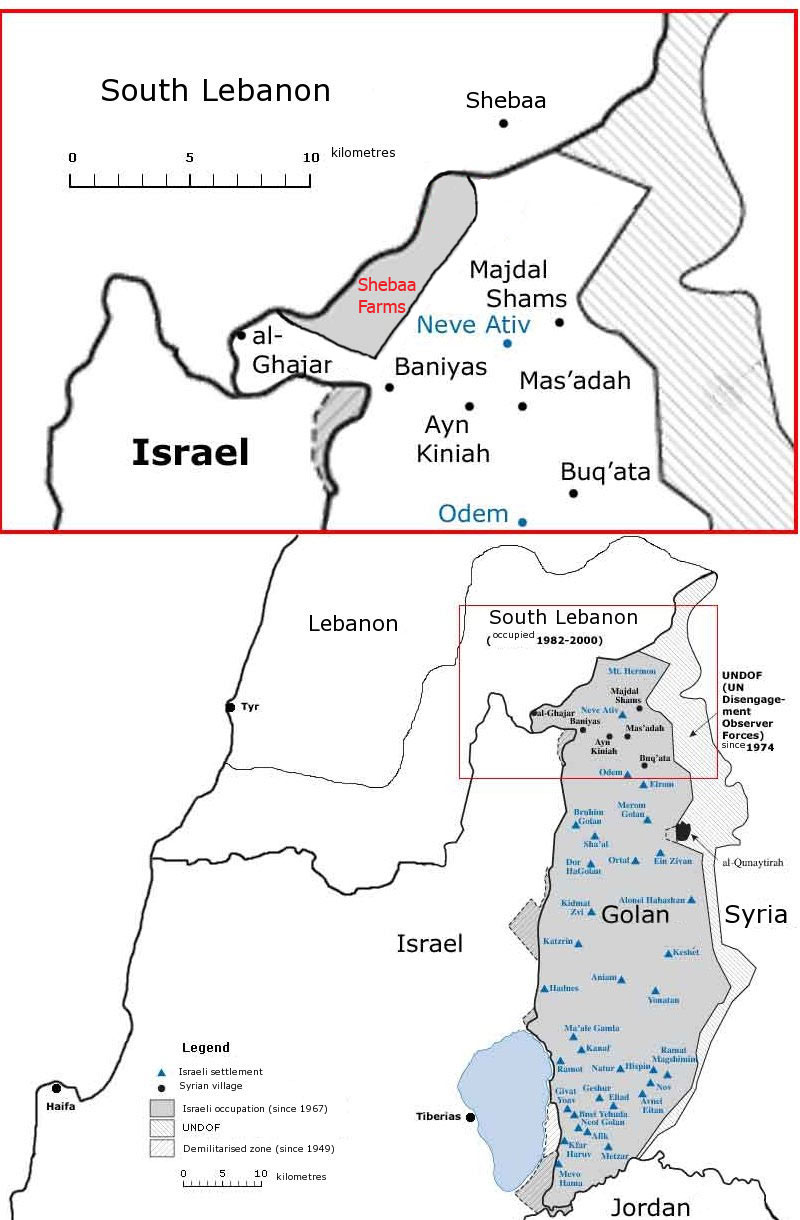

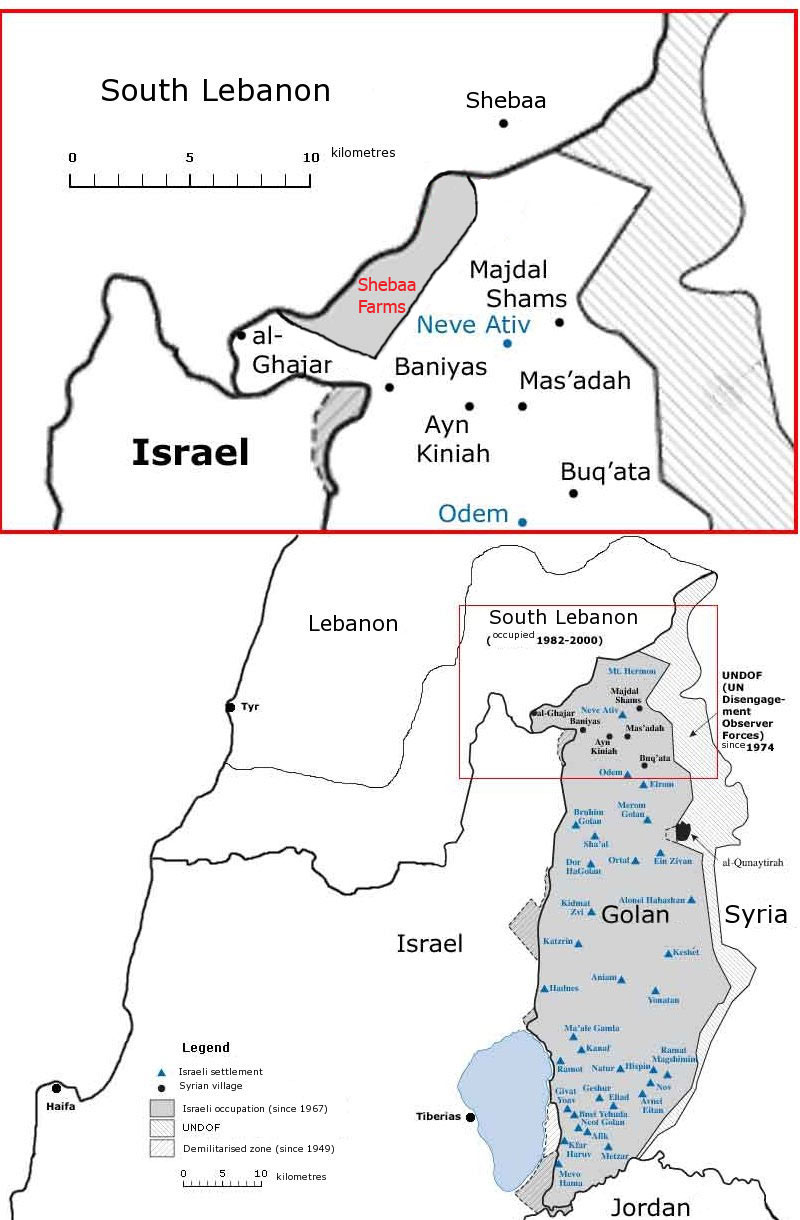

The Shebaa Farms conflict stems from Israel's occupation and annexation of the Golan Heights, with respect to that territory's border with Lebanon. Both Lebanon and Syria were within the French Mandate territory between 1920 and the end of the French Mandate in 1946. The dispute over the sovereignty over the

The Shebaa Farms conflict stems from Israel's occupation and annexation of the Golan Heights, with respect to that territory's border with Lebanon. Both Lebanon and Syria were within the French Mandate territory between 1920 and the end of the French Mandate in 1946. The dispute over the sovereignty over the

A border between the

A border between the

On November 29, 1947, the

On November 29, 1947, the  On May 15, regular Arab armies entered what had been Mandate Palestine. This intervention/invasion marked the transition of the

On May 15, regular Arab armies entered what had been Mandate Palestine. This intervention/invasion marked the transition of the

The status and boundary of Jerusalem continue to be in dispute.

Following the

The status and boundary of Jerusalem continue to be in dispute.

Following the

82 FR 58331

/ref> Secretary of State

available in pdf here

**

Agreement between His Majesty's Government and the French Government respecting the Boundary Line between Syria and Palestine from the Mediterranean to El Hámmé, Treaty Series No. 13 (1923), Cmd. 1910.

* * Biger, Gideon (1989), Geographical and other arguments in delimitation in the boundaries of British Palestine, ''in'' "International Boundaries and Boundary Conflict Resolution", IBRU Conference, , pp. 41–61. * Biger, Gideon (1995), ''The encyclopedia of international boundaries'', New York: Facts on File. * Biger, Gideon (2005),

'. London: Routledge. . * Franco-British Convention on Certain Points Connected with the Mandates for Syria and the Lebanon, Palestine and Mesopotamia, signed December 23, 1920. Text available in ''American Journal of International Law'', Vol. 16, No. 3, 1922, 122–126. * * * Gil-Har, Yitzhak (1993), British commitments to the Arabs and their application to the Palestine-Trans-Jordan boundary: The issue of the Semakh triangle, ''Middle Eastern Studies'', Vol.29, No.4, pp. 690–701. * * McTague, John (1982), Anglo-French Negotiations over the Boundaries of Palestine, 1919–1920, ''Journal of Palestine Studies'', Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 101–112. * Muhsin, Yusuf (1991), The Zionists and the process of defining the borders of Palestine, 1915–1923, ''Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies'', Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 18–39. * US Department of State, International Boundary Study series

Iraq-JordanIraq-SyriaJordan-SyriaIsrael-Lebanon

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Borders of Israel Foreign relations of Israel History of Israel Arab–Israeli conflict International borders

Dennis Ross

Dennis B. Ross (born November 26, 1948) is an American diplomat and author. He has served as the Director of Policy Planning in the State Department under President George H. W. Bush, the special Middle East coordinator under President Bill Clint ...

. . pp 584-585 These territories were designated demilitarized zone

A demilitarized zone (DMZ or DZ) is an area in which treaties or agreements between nations, military powers or contending groups forbid military installations, activities, or personnel. A DZ often lies along an established frontier or bounda ...

s (DMZs) and remained under Syrian control (marked as DMZs on second map). It was emphasised that the armistice line was "not to be interpreted as having any relation whatsoever to ultimate territorial arrangements." (Article V)

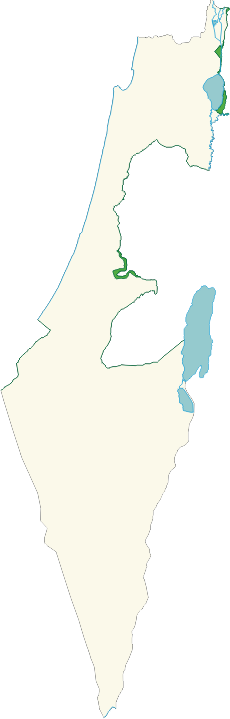

During the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

(1967), Israel captured the territory as well as the rest of the Golan Heights, and subsequently repelled a Syrian attempt to recapture it during the Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was an armed conflict fought from October 6 to 25, 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab states led by Egy ...

(1973). Israel annexed the Golan Heights in 1981 with the Golan Heights Law

The Golan Heights Law () is the Israeli law which applies Israel's government and laws to the Golan Heights. It was ratified by the Knesset by a vote of 63―21, on December 14, 1981.Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs.Golan Heights Law Although ...

. Israel began building settlements throughout the Golan Heights, and offered the Druze and Circassian residents citizenship, which most turned down. Today, Israel regards the Golan Heights as its sovereign territory, and a strategic necessity. The Purple Line marks the boundary between Israel and Syria. Israel's unilateral annexation has not been internationally recognized, and United Nations Security Council Resolution 242

United Nations Security Council Resolution 242 (S/RES/242) was adopted unanimously by the UN Security Council on November 22, 1967, in the aftermath of the Six-Day War. It was adopted under Chapter VI of the UN Charter. The resolution was spons ...

refers to the area as Israeli-occupied.

During the 1990s, there were constant negotiations between Israel and Syria regarding a mediation of conflicts and an Israeli withdrawal from the Golan Heights but a peace treaty did not come to fruition. The main stumbling block seems to involve the 66 square kilometers of territory that Syria retained under the 1949 armistice agreement. Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

countries support Syria's position in the formula which calls on Israel "to return to the 1967 borders". (See 2002 Arab Peace Initiative

The Arab Peace Initiative ( ar, مبادرة السلام العربية; ), also known as the Saudi Initiative (; ), is a 10 sentence proposal for an end to the Arab–Israeli conflict that was endorsed by the Arab League in 2002 at the Beiru ...

)

Lebanon conflict

On March 14, 1978, Israel launched

On March 14, 1978, Israel launched Operation Litani

The 1978 South Lebanon conflict (codenamed Operation Litani by Israel) began after Israel invaded southern Lebanon up to the Litani River in March 1978, in response to the Coastal Road massacre near Tel Aviv by Lebanon-based Palestinian mil ...

, occupying the area south of the Litani River

The Litani River ( ar, نهر الليطاني, Nahr al-Līṭānī), the classical Leontes ( grc-gre, Λέοντες, Léontes, lions), is an important water resource in southern Lebanon. The river rises in the fertile Beqaa Valley, west of B ...

, excepting Tyre (see map). In response to the invasion, the UN Security Council passed Council Resolution 425 and Resolution 426 calling for the withdrawal of Israeli forces from Lebanon. Israeli forces withdrew later in 1978, but turned over their positions inside Lebanon to their ally, the South Lebanon Army

The South Lebanon Army or South Lebanese Army (SLA; ar, جيش لبنان الجنوبي, Jayš Lubnān al-Janūbiyy), also known as the Lahad Army ( ar, جيش لحد, label=none) and referred to as the De Facto Forces (DFF) by the United Nat ...

(SLA).

The United Nations in June 2000 was called upon to decide the Lebanese border to determine whether Israel had fully withdrawn from Lebanon in compliance with UN Security Council Resolution 425

United Nations Security Council Resolution 425, adopted on 19 March 1978, five days after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in the context of Palestinian insurgency in South Lebanon and the Lebanese Civil War, called on Israel to withdraw immed ...

. This line came to be called the Blue Line. At the same time, the United Nations did not have to consider the legality of the boundary between Lebanon and the Israeli-controlled Golan Heights, as that was not required for the purpose of Council Resolution 425. Accordingly, the Armistice Demarcation Line between Lebanon and the Israeli-controlled Golan Heights is expressly not to be called the Blue Line.

The Blue Line, which the UN had to determine, was the line of deployment of the IDF

IDF or idf may refer to:

Defence forces

* Irish Defence Forces

* Israel Defense Forces

*Iceland Defense Force, of the US Armed Forces, 1951-2006

* Indian Defence Force, a part-time force, 1917

Organizations

* Israeli Diving Federation

* Interac ...

before March 14, 1978, when Israel invaded Lebanon. In effect that line was recognised by both Lebanon and by Israel as the international border, and not just as the Armistice Demarcation Line of 1949 (what is commonly called the Green Line) following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

.

On April 17, 2000, Israel announced that it would withdraw its forces from Lebanon. The Lebanese government refused to take part in marking the border. The UN thus conducted its own survey based on the line for the purpose of Council Resolution 425, which called for "strict respect for the territorial integrity, sovereignty and political independence of Lebanon within its internationally recognized boundaries".

From May 24 to June 7, 2000, the UN Special Envoy heard views in Israel, Lebanon and Syria. The United Nations cartographer and his team, assisted by UNIFIL, worked on the ground to identify a line to be adopted for the practical purposes of confirming the Israeli withdrawal. While it was agreed that this would not be a formal border demarcation, the aim was to identify a line on the ground closely conforming to the internationally recognized boundaries of Lebanon, based on the best available cartographic and other documentary evidence. On May 25, 2000, Israel notified the Secretary-General

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

that it had redeployed its forces in compliance with Council Resolution 425, that is to the Internationally recognized Lebanese border. On June 7, the completed map showing the withdrawal line was formally transmitted by the force commander of UNIFIL to his Lebanese and Israeli counterparts. Notwithstanding their reservations about the line, the governments of Israel and Lebanon confirmed that identifying this line was solely the responsibility of the United Nations and that they would respect the line as identified.

On June 8, 2000, UNIFIL teams commenced the work of verifying the Israeli withdrawal behind the line.

The Blue Line

The Blue Line identified by the United Nations in 2000 as the border of Lebanon, from theMediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

to the Hasbani River

The Hasbani River ( ar, الحاصباني / ALA-LC: ''al-Ḥāṣbānī''; he, חצבני ''Ḥatzbaní'') or Snir Stream ( he, נחל שניר / ''Nahal Sənir''), is the major tributary of the Jordan River. Local natives in the mid-19th centu ...

, closely approximates the Green Line set under the 1949 armistice agreement

The 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel and Egypt,Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

(see: Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

).

* Unlike the other Green Line agreements, it contains no clause disclaiming this line as an international border, and was thereafter treated as it had been previously, as the de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

international border of Lebanon.

* Israel withdrew its forces from 13 villages in Lebanese territory, which were occupied during the war.

In 1923, 38 boundary markers were placed along the boundary and a detailed text description was published. The 2000 Blue Line differs in about a half dozen short stretches from the 1949 line, although never by more than .

Between 1950 and 1967, Israeli and Lebanese surveyors managed to complete 25 non-contiguous kilometers and mark (but not sign) another quarter of the international border.

On June 16, the Secretary-General

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

reported to the Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, and ...

that Israel had withdrawn its forces from Lebanon in accordance with Council Resolution 425 and met the requirements defined in his report of May 22, 2000. The withdrawal line has been termed the Blue Line in all official UN communications since.

Conflict over the Shebaa Farms

The Shebaa Farms conflict stems from Israel's occupation and annexation of the Golan Heights, with respect to that territory's border with Lebanon. Both Lebanon and Syria were within the French Mandate territory between 1920 and the end of the French Mandate in 1946. The dispute over the sovereignty over the

The Shebaa Farms conflict stems from Israel's occupation and annexation of the Golan Heights, with respect to that territory's border with Lebanon. Both Lebanon and Syria were within the French Mandate territory between 1920 and the end of the French Mandate in 1946. The dispute over the sovereignty over the Shebaa Farms

The Shebaa Farms, also spelled Sheba'a Farms ( ar, مزارع شبعا, '; he, חוות שבעא, ''Havot Sheba‘a'' or הר דוב, ''Har Dov''), are a small strip of land at the intersection of the Lebanese-Syrian border and the Israeli-oc ...

resulted in part from the failure of French Mandate

Mandate most often refers to:

* League of Nations mandates, quasi-colonial territories established under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, 28 June 1919

* Mandate (politics), the power granted by an electorate

Mandate may also ...

administrations, and subsequently from the failure of the Lebanon and Syria to properly demarcate the border between them.

Documents from the 1920s and 1930s indicate that some local inhabitants regarded themselves as part of Lebanon, for example paying taxes to the Lebanese government. But French officials at times expressed confusion as to the actual location of the border. One French official in 1939 expressed the belief that the uncertainty was sure to cause trouble in the future.

The region continued to be represented in the 1930s and 1940s as Syrian territory, under the French Mandate. Detailed maps showing the border were produced by the French in 1933, and again in 1945. They clearly showed the region to be in Syria.

After the French Mandate ended in 1946, the land was administered by Syria, and represented as such in all maps of the time. The maps of the 1949 armistice agreement between Syria and Israel also designated the area as Syrian.

Border disputes arose at times, however. Shebaa Farms was not unique; several other border villages had similar discrepancies of borders versus land ownership. Syria and Lebanon formed a joint Syrian–Lebanese border committee in the late 1950s to determine a proper border between the two nations. In 1964, concluding its work, the committee suggested to the two governments that the area be deemed the property of Lebanon, and recommended that the international border be reestablished consistent with its suggestion. However, neither Syria nor Lebanon adopted the committee's suggestion, and neither country took any action along the suggested lines. Thus, maps of the area continued to reflect the Farms as being in Syria. Even maps of both the Syrian and Lebanese armies continued to demarcate the region within Syrian territory (see map).

A number of local residents regarded themselves as Lebanese, however. The Lebanese government showed little interest in their views. The Syrian government administered the region, and on the eve of the 1967 war, the region was under effective Syrian control.

In 1967, most Shebaa Farms landowners and (Lebanese) farmers lived outside the Syrian-controlled region, across the Lebanon-Syrian border, in the Lebanese village of Shebaa. During the Six Day War in 1967, Israel captured the Golan Heights from Syria, including the Shebaa Farms area. As a consequence, the Lebanese landowners were no longer able to farm it.

Israel—Lebanon maritime border

As of April 2021, there is an ongoing dispute over the Mediterranean Sea border between Israel and Lebanon. Negotiations on the maritime border commenced in October 2020.Border with Egypt

A border between the

A border between the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and British controlled Khedivate of Egypt

The Khedivate of Egypt ( or , ; ota, خدیویت مصر ') was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which brou ...

was drawn in the Ottoman–British agreement of October 1, 1906, after a military crisis earlier that year.

According to the personal documents of the British colonel Wilfed A. Jennings Bramley, who influenced the negotiations, the border mainly served British military interests—it furthered the Ottomans as much as possible from the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

, and gave Britain complete control over both Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

gulfs—Suez and Aqaba, including the Straits of Tiran

The straits of Tiran ( ar, مضيق تيران ') are the narrow sea passages between the Sinai and Arabian peninsulas that connect the Gulf of Aqaba and the Red Sea. The distance between the two peninsulas is about . The Multinational Force an ...

. At the time, the Aqaba

Aqaba (, also ; ar, العقبة, al-ʿAqaba, al-ʿAgaba, ) is the only coastal city in Jordan and the largest and most populous city on the Gulf of Aqaba. Situated in southernmost Jordan, Aqaba is the administrative centre of the Aqaba Govern ...

branch of the Hejaz railway had not been built, and the Ottomans therefore had no simple access to the Red Sea. The British were also interested in making the border as short and patrollable as possible, and did not take into account the needs of the local residents in the negotiations.Gardus and Shmueli (1979), pp. 369–370 It was defined as an "administrative separating line" for diplomatic reasons, allowing the Ottoman Empire to hold to its nominal sovreignity over Egypt.

The 1949 armistice agreement between Israel and Egypt was ratified on February 24, 1949. The armistice line between these countries followed the international border except along the Gaza Strip, which remained under Egyptian occupation.

The Egypt–Israel peace treaty

The Egypt–Israel peace treaty ( ar, معاهدة السلام المصرية الإسرائيلية, Mu`āhadat as-Salām al-Misrīyah al-'Isrā'īlīyah; he, הסכם השלום בין ישראל למצרים, ''Heskem HaShalom Bein Yisrael ...

, signed on March 26, 1979, created an officially recognized international border along the 1906 line, with Egypt renouncing all claims to the Gaza Strip. A dispute arose over the marking of the border line at its southernmost point, in Taba. Taba was on the Egyptian side of the armistice line of 1949, but Israel claimed that Taba had been on the Ottoman side of a border agreed between the Ottomans and British Egypt in 1906, and that there had previously been an error in marking the line. The issue was submitted to an international commission composed of one Israeli, one Egyptian, and three outsiders. In 1988, the commission ruled in Egypt's favor, and Israel withdrew from Taba later that year.

Borders with Palestine

End of British Mandate

On November 29, 1947, the

On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

adopted Resolution 181 (II) recommending ''the adoption and implementation'' of a plan to partition Palestine into "Independent Arab and Jewish States" and a "Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem" administered by the United Nations. The Jewish Agency for Palestine

The Jewish Agency for Israel ( he, הסוכנות היהודית לארץ ישראל, translit=HaSochnut HaYehudit L'Eretz Yisra'el) formerly known as The Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jews, Jewish non-profit organization in the w ...

, on behalf of the Jewish community, despite its misgivings, indicated acceptance of the plan. With a few exceptions, the Arab leaders and governments rejected the plan of partition in the resolution and indicated that they would reject any other plan of partition. Britain declared that the Mandate was to end on May 15, 1948.

On May 14, 1948, David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the name ...

, in a ceremony in Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

, declared "the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Israel ...

, to be known as the State of Israel." Epstein, Agent, Provisional Government of Israel said in a letter to President Truman seeking recognition from the U.S government, sent immediately after the Declaration of May 14, 1948, "that the state of Israel has been proclaimed as an independent republic within frontiers approved by the General Assembly of the United Nations in its Resolution of November 29, 1947", (i.e., within the area designated as the "Jewish state" in the partition plan).

On May 15, regular Arab armies entered what had been Mandate Palestine. This intervention/invasion marked the transition of the

On May 15, regular Arab armies entered what had been Mandate Palestine. This intervention/invasion marked the transition of the 1947–1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine

The 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine was the first phase of the 1947–1949 Palestine war. It broke out after the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted a resolution on 29 November 1947 recommending the adoption of the Pa ...

into the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

. The tide of battle soon turned against the Arabs, and Israel then launched a series of military offensives, greatly expanding its territorial holdings. The end of the war saw the Lausanne Conference of 1949. Following internationally supervised Arab-Israeli negotiations, a boundary based on the cease-fire lines of the war with minor territorial adjustments, commonly referred to as the Green Line, was agreed upon in the 1949 Armistice Agreements

The 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel and Egypt,demarcation line

{{Refimprove, date=January 2008

A political demarcation line is a geopolitical border, often agreed upon as part of an armistice or ceasefire.

Africa

* Moroccan Wall, delimiting the Moroccan-controlled part of Western Sahara from the Sahrawi- ...

, rather than a permanent border, and the Armistice Agreements relegated the issue of permanent borders to future negotiations. The area to the west of the Jordan River came to be called the West Bank, and was annexed by Jordan in 1950; and the Gaza Strip was occupied by Egypt. During the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

of 1967, Israel captured the West Bank from Jordan, Gaza Strip and Sinai peninsula from Egypt, and Golan Heights from Syria, and placed these territories under military occupation

Military occupation, also known as belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is the effective military control by a ruling power over a territory that is outside of that power's sovereign territory.Eyāl Benveniśtî. The international law ...

.

On September 22, 1948, during a truce in the war, the Provisional State Council

The Provisional State Council ( he, מועצת המדינה הזמנית, ''Moetzet HaMedina HaZmanit'') was the temporary legislature of Israel from shortly before independence until the election of the first Knesset in January 1949. It took the ...

of Israel passed a law to annex all land that Israel had captured in the war, and declaring that from then on, any part of Palestine taken by the Israeli army would automatically be annexed to Israel. This, effectively, annexed to Israel all land within the Green Line, though the armistice agreements were declared to be temporary and not permanent borders.

Subsequent events

In 1988, Palestine declared its independence without specifying its borders. Jordan extended recognition to Palestine and renounced its claim to theWest Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

to the Palestinian Liberation Organisation, which had been previously designated by the Arab League as the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people".

In 2011, Palestine submitted an application for membership to the United Nations, using the borders for military administration that existed before 1967, effectively the 1949 armistice line or Green Line. As Israel does not recognize the State of Palestine

Palestine ( ar, فلسطين, Filasṭīn), Legal status of the State of Palestine, officially the State of Palestine ( ar, دولة فلسطين, Dawlat Filasṭīn, label=none), is a state (polity), state located in Western Asia. Officiall ...

, Jordan's borders with Israel remain unclear, at least in the sector of the West Bank.

Israel and the Palestinian territories now lay entirely within the boundaries of the former territory of Mandatory Palestine. By the Egypt–Israel peace treaty

The Egypt–Israel peace treaty ( ar, معاهدة السلام المصرية الإسرائيلية, Mu`āhadat as-Salām al-Misrīyah al-'Isrā'īlīyah; he, הסכם השלום בין ישראל למצרים, ''Heskem HaShalom Bein Yisrael ...

of 1979, Egypt renounced all claims to the Gaza Strip. In 1988, Jordan renounced all claims to the West Bank; this was made official in the Israel–Jordan Treaty of Peace of 1994. The Green Line is Israel's contested boundary with the Palestinian territories.

The boundaries of a future Palestinian State, vis-a-vis Israel, are subject to ongoing negotiations in the Israel–Palestinian peace process. Israel's West Bank Wall, which encompasses almost all Israeli settlement

Israeli settlements, or Israeli colonies, are civilian communities inhabited by Israeli citizens, overwhelmingly of Jewish ethnicity, built on lands occupied by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. The international community considers Israeli se ...

s, including all three major cities, and only a minor Palestinian population, was declared by Prime Minister Ehud Olmert

Ehud Olmert (; he, אֶהוּד אוֹלְמֶרְט, ; born 30 September 1945) is an Israeli politician and lawyer. He served as the 12th Prime Minister of Israel from 2006 to 2009 and before that as a cabinet minister from 1988 to 1992 and ...

as running roughly along the future borders of Israel. Israeli Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman

Avigdor Lieberman (, ; russian: Эве́т Льво́вич Ли́берман, Evet Lvovich Liberman, ; born 5 June 1958) is a Soviet-born Israeli politician serving as Minister of Finance since 2021, having previously served twice as Deputy ...

proposed that the Arab-Israeli border region known as the Triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three Edge (geometry), edges and three Vertex (geometry), vertices. It is one of the basic shapes in geometry. A triangle with vertices ''A'', ''B'', and ''C'' is denoted \triangle ABC.

In Euclidean geometry, an ...

be removed from Israeli sovereignty and transferred to the Palestinian Authority, in exchange for the border settlement blocs. The Palestinian Authority

The Palestinian National Authority (PA or PNA; ar, السلطة الوطنية الفلسطينية '), commonly known as the Palestinian Authority and officially the State of Palestine,

claims all of these territories (including East Jerusalem) for a future Palestinian State

Palestine ( ar, فلسطين, Filasṭīn), officially the State of Palestine ( ar, دولة فلسطين, Dawlat Filasṭīn, label=none), is a state located in Western Asia. Officially governed by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PL ...

, and its position is supported by the Arab League in the 2002 Arab Peace Initiative

The Arab Peace Initiative ( ar, مبادرة السلام العربية; ), also known as the Saudi Initiative (; ), is a 10 sentence proposal for an end to the Arab–Israeli conflict that was endorsed by the Arab League in 2002 at the Beiru ...

which calls for the return by Israel to "the 1967 borders". While Israel has expressed desire to annex the border settlement blocs and keep East Jerusalem, its border with Gaza has largely been solidified, especially following Israel's withdrawal in 2005. Israel has not made claims to any portion of Gazan territory and offered the entire area to Palestinians as part of the 2000 Camp David Summit

The 2000 Camp David Summit was a summit meeting at Camp David between United States president Bill Clinton, Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak and Palestinian Authority chairman Yasser Arafat. The summit took place between 11 and 25 July 2000 a ...

.

At the same time, Israel has continued to claim a nominal strip on the border between the West Bank and Jordan, and between Gaza and Egypt as its border with those countries. This is viewed as a legalistic device to enable Israel to control the entry of people and materials into the Palestinian territories.

Status of Jerusalem

The status and boundary of Jerusalem continue to be in dispute.

Following the

The status and boundary of Jerusalem continue to be in dispute.

Following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

, Israel was in control of West Jerusalem

West Jerusalem or Western Jerusalem (, ; , ) refers to the section of Jerusalem that was controlled by Israel at the end of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. As the city was divided by the Green Line (Israel's erstwhile border, established by t ...

while Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

was in control of East Jerusalem

East Jerusalem (, ; , ) is the sector of Jerusalem that was held by Jordan during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, as opposed to the western sector of the city, West Jerusalem, which was held by Israel.

Jerusalem was envisaged as a separat ...

(including the walled Old City in which most of the holy places are located). During the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

of 1967, Israel gained control of the West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

, as well as East Jerusalem, and shortly after extended Jerusalem's municipality city limits

City limits or city boundaries refer to the defined boundary or border of a city. The area within the city limit can be called the city proper. Town limit/boundary and village limit/boundary apply to towns and villages. Similarly, corporate limi ...

to cover the whole of East Jerusalem and the surrounding area, and applied its laws, jurisdiction, and administration to that territory. In 1980, the Knesset

The Knesset ( he, הַכְּנֶסֶת ; "gathering" or "assembly") is the unicameral legislature of Israel. As the supreme state body, the Knesset is sovereign and thus has complete control of the entirety of the Israeli government (with ...

passed the Jerusalem Law

The Jerusalem Law (, ar, قانون القدس) is a common name of Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel passed by the Knesset on 30 July 1980 (17th Av, 5740).

Although the law did not use the term, the Israeli Supreme Court interpreted the ...

, declaring Jerusalem to be the "complete and united" capital of Israel. The Israeli government offered citizenship to the Palestinian residents of that territory, most of whom refused, and are treated today as permanent residents

Permanent residency is a person's legal resident status in a country or territory of which such person is not a citizen but where they have the right to reside on a permanent basis. This is usually for a permanent period; a person with suc ...

under Israeli law. According to the Israeli rights organisation, Hamoked

HaMoked (Hebrew:המוקד, Center for the Defence of the Individual) is an Israel based human rights organization founded by Dr. Lotte Salzberger with the stated aim of assisting " Palestinians subjected to the Israeli occupation which causes s ...

, if these Palestinians live abroad for seven years, or gain citizenship or residency elsewhere, they lose their Israeli residency status.

The purported annexation of East Jerusalem was criticised by Palestinian, Arab and other leaders, and was declared by the United Nations Security Council "a violation of international law" and "null and void" in Resolution 478, and has not been recognized by the international community, and all countries moved their embassies from Jerusalem.

On December 6, 2017, US President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pe ...

announced the United States recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.Proclamation 9683 of December 6, 201782 FR 58331

/ref> Secretary of State

Rex Tillerson

Rex Wayne Tillerson (born March 23, 1952) is an American engineer and energy executive who served as the 69th U.S. secretary of state from February 1, 2017, to March 31, 2018, under President Donald Trump. Prior to joining the Trump administ ...

clarified "that the final status or Jerusalem including the borders, would be left to the two parties to negotiate and decide." Since then, several other countries have formally recognised Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, and moved their embassies there.

See also

* 2011 Israeli border demonstrations * Baraita of the BoundariesNotes

References

Bibliography

* *available in pdf here

**

Agreement between His Majesty's Government and the French Government respecting the Boundary Line between Syria and Palestine from the Mediterranean to El Hámmé, Treaty Series No. 13 (1923), Cmd. 1910.

* * Biger, Gideon (1989), Geographical and other arguments in delimitation in the boundaries of British Palestine, ''in'' "International Boundaries and Boundary Conflict Resolution", IBRU Conference, , pp. 41–61. * Biger, Gideon (1995), ''The encyclopedia of international boundaries'', New York: Facts on File. * Biger, Gideon (2005),

'. London: Routledge. . * Franco-British Convention on Certain Points Connected with the Mandates for Syria and the Lebanon, Palestine and Mesopotamia, signed December 23, 1920. Text available in ''American Journal of International Law'', Vol. 16, No. 3, 1922, 122–126. * * * Gil-Har, Yitzhak (1993), British commitments to the Arabs and their application to the Palestine-Trans-Jordan boundary: The issue of the Semakh triangle, ''Middle Eastern Studies'', Vol.29, No.4, pp. 690–701. * * McTague, John (1982), Anglo-French Negotiations over the Boundaries of Palestine, 1919–1920, ''Journal of Palestine Studies'', Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 101–112. * Muhsin, Yusuf (1991), The Zionists and the process of defining the borders of Palestine, 1915–1923, ''Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies'', Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 18–39. * US Department of State, International Boundary Study series

Iraq-Jordan

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Borders of Israel Foreign relations of Israel History of Israel Arab–Israeli conflict International borders