Isham Harris on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

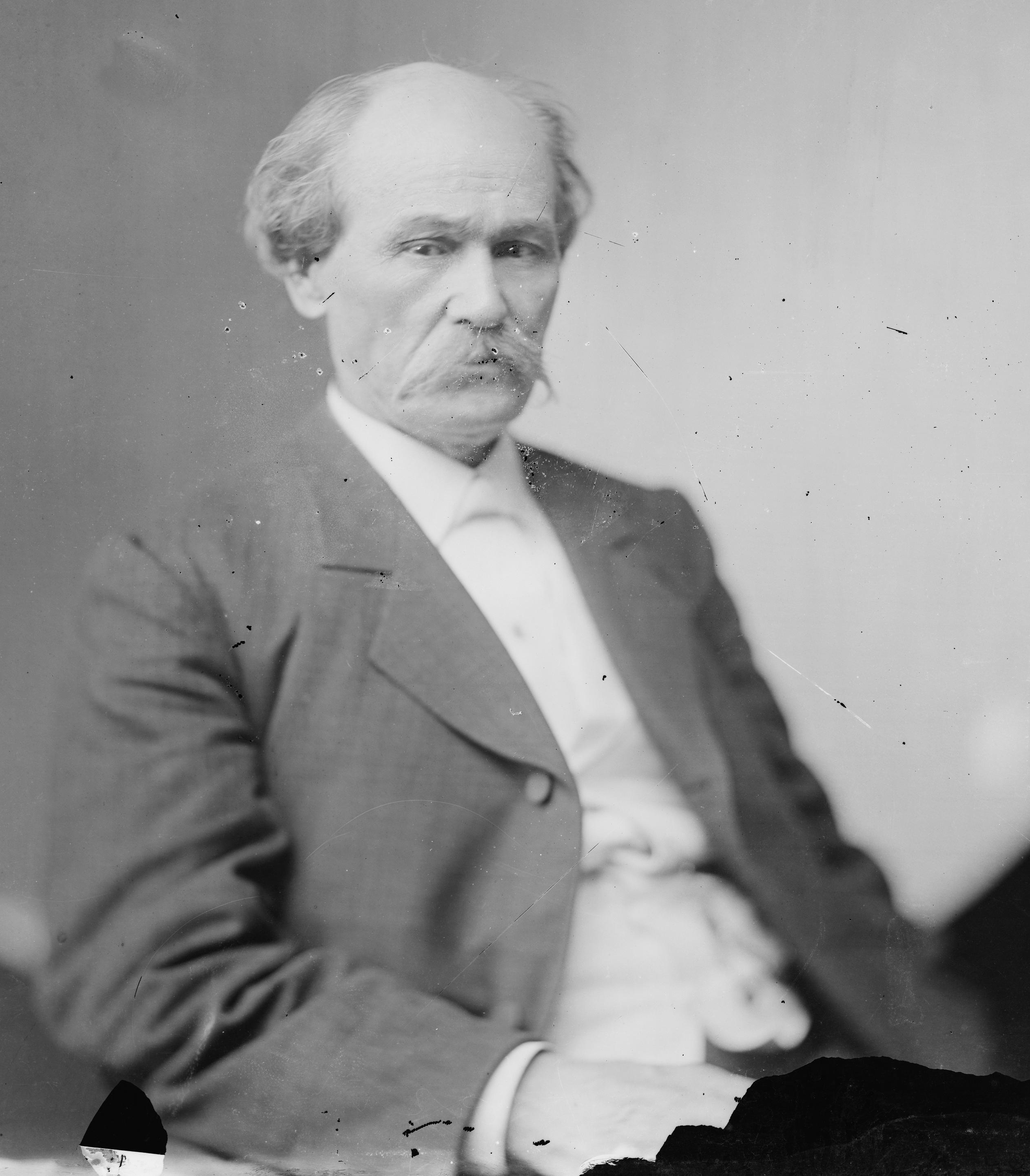

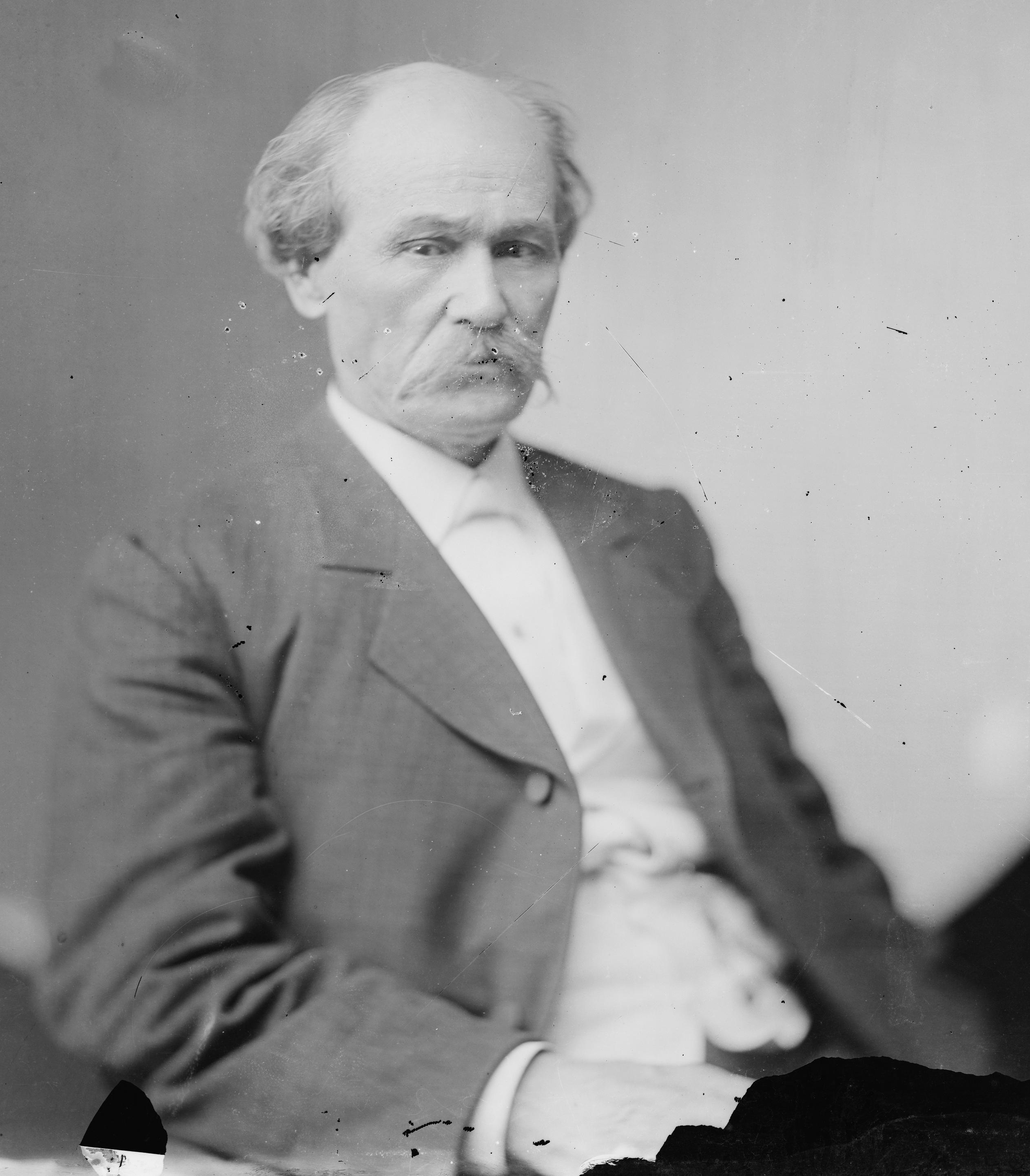

Isham Green Harris (February 10, 1818July 8, 1897) was an American politician who served as the 16th

Notable Men of Tennessee

' (New York: The Cosmopolitan Press, 1912), p. 337. Harris rose to prominence in state politics in the late 1840s when he campaigned against the anti-slavery initiatives of northern Whigs. He was elected governor amidst rising sectional strife in the late 1850s, and following the election of

Isham Green Harris

" ''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture'', 2009. Retrieved: 5 October 2012. After returning to Tennessee, Harris became a leader of the state's Bourbon Democrats. During his tenure in the U. S. Senate, he championed states' rights and currency expansion. As the Senate's

Isham Green Harris

" ''Historical Dictionary of the Gilded Age'' (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2003), pp. 216–217.

Isham G. Harris: Confederate Governor and United States Senator of Tennessee

' (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010), pp. 15–19. In 1848, Harris was an

In 1857, Tennessee's Democratic governor,

In 1857, Tennessee's Democratic governor,

Harris endorsed

Harris endorsed

By 1877, the Tennessee state legislature, which was once again controlled by Democrats, elected Harris to one of the state's U.S. Senate seats. One of his earliest assignments, in the

By 1877, the Tennessee state legislature, which was once again controlled by Democrats, elected Harris to one of the state's U.S. Senate seats. One of his earliest assignments, in the

Harris died in office on July 8, 1897. His funeral was held in the Senate chamber of the United States Capitol. Congressman

Harris died in office on July 8, 1897. His funeral was held in the Senate chamber of the United States Capitol. Congressman

Memorial Address for Isham G. Harris

(Government Printing Office, 1898), pp. 105-115. He is interred at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee.

Governor Isham G. Harris, 1857-1862

at Tennessee State Library and Archives {{DEFAULTSORT:Harris, Isham Green 1818 births 1897 deaths People from Franklin County, Tennessee Burials in Tennessee Albert Sidney Johnston Confederate States Army officers Governors of Tennessee Tennessee state senators People of Tennessee in the American Civil War Democratic Party United States senators from Tennessee Confederate States of America state governors Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Tennessee Democratic Party governors of Tennessee American slave owners 19th-century American politicians Presidents pro tempore of the United States Senate People from Ripley, Mississippi Bourbon Democrats Southern Historical Society United States senators who owned slaves

governor of Tennessee

The governor of Tennessee is the head of government of the U.S. state of Tennessee. The governor is the only official in Tennessee state government who is directly elected by the voters of the entire state.

The current governor is Bill Lee, a ...

from 1857 to 1862, and as a U.S. senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

from 1877 until his death. He was the state's first governor from West Tennessee

West Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions (Tennessee), Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that roughly comprises the western quarter of the state. The region includes 21 counties between the Tennessee River, Tennessee and Miss ...

. A pivotal figure in the state's history, Harris was considered by his contemporaries the person most responsible for leading Tennessee out of the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

and aligning it with the Confederacy during the Civil War.Allan Nevins, ''Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage'' (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1934), pp. 194, 256, 543-546, 576.Philip Hamer, ''Tennessee: A History, 1673-1932'' (New York: American Historical Society, Inc., 1933), pp. 508, 513–514, 527–528, 534, 539–546, 554, 591, 639. Oliver Perry Temple, Notable Men of Tennessee

' (New York: The Cosmopolitan Press, 1912), p. 337. Harris rose to prominence in state politics in the late 1840s when he campaigned against the anti-slavery initiatives of northern Whigs. He was elected governor amidst rising sectional strife in the late 1850s, and following the election of

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

in 1860, persistently sought to sever the state's ties with the Union. His war-time efforts eventually raised over 100,000 soldiers for the Confederate cause. After the Union Army gained control of Middle and West Tennessee in 1862, Harris spent the remainder of the war on the staffs of various Confederate generals. Following the war, he spent several years in exile in Mexico and England.Leonard Schlup,Isham Green Harris

" ''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture'', 2009. Retrieved: 5 October 2012. After returning to Tennessee, Harris became a leader of the state's Bourbon Democrats. During his tenure in the U. S. Senate, he championed states' rights and currency expansion. As the Senate's

president pro tempore

A president pro tempore or speaker pro tempore is a constitutionally recognized officer of a legislative body who presides over the chamber in the absence of the normal presiding officer. The phrase ''pro tempore'' is Latin "for the time being". ...

in the 1890s, Harris led the charge against President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

's attempts to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act was a United States federal law

enacted on July 14, 1890.Charles Ramsdell Lingley, ''Since the Civil War'', first edition: New York, The Century Co., 1920, ix–635 p., . Re-issued: Plain Label Books, unknown date, ...

.Leonard Schlup,Isham Green Harris

" ''Historical Dictionary of the Gilded Age'' (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2003), pp. 216–217.

Early life and career

Harris was born in Franklin County, Tennessee near Tullahoma. He was the ninth child of Isham Green Harris, a farmer and Methodist minister, and his wife Lucy Davidson Harris. His parents had moved from North Carolina to Middle Tennessee in 1806. He was educated at Carrick Academy in Winchester, Tennessee, until he was fourteen. He moved toParis, Tennessee

Paris is a city in and the county seat of Henry County, Tennessee, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 10,316.

A replica of the Eiffel Tower stands in the southern part of Paris.

History

The present site of Pari ...

, where he joined up with his brother William R. Harris

William R. Harris (September 26, 1803 – June 19, 1858) was a justice of the Tennessee Supreme Court from 1855 to 1858.

Early life, education, and career

Born in Montgomery County, North Carolina,Albert D. Marks, "The Supreme Court of Tennessee ...

, an attorney, and became a store clerk. In 1838, with funds provided by his brother, Harris established his own business in Ripley, Mississippi, an area that had only been recently opened to settlers after a treaty with the Chickasaw Indians.

While in Ripley, Harris studied law. He sold his successful business three years later for $7,000 and returned to Paris where he continued studying law under Judge Andrew McCampbell. On May 3, 1841, he was admitted to the bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

in Henry County and began a lucrative practice in Paris. He was considered one of the leading criminal attorneys in the state.

On July 6, 1843, Harris married Martha Mariah Travis (nicknamed "Crockett"), the daughter of Major Edward Travis, a War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

veteran. The couple had seven sons. By 1850 the family had a farm and a home in Paris. By 1860 their total property was worth $45,000 and included twenty slaves and a plantation in Shelby County.

In 1847, Henry County Democrats convinced Harris to run for the district's Tennessee Senate seat in hopes of countering a strong campaign by local Whig politician William Hubbard. Anti-war comments made in August by the district's Whig congressional candidate, William T. Haskell, damaged Hubbard's campaign, and he quit the race. Harris easily defeated the last minute Whig replacement, Joseph Roerlhoe. Shortly after taking his seat, he sponsored a resolution condemning the Wilmot Proviso, which would have banned slavery in territories acquired during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

.Sam Davis Elliott, Isham G. Harris: Confederate Governor and United States Senator of Tennessee

' (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010), pp. 15–19. In 1848, Harris was an

elector

Elector may refer to:

* Prince-elector or elector, a member of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire, having the function of electing the Holy Roman Emperors

* Elector, a member of an electoral college

** Confederate elector, a member of ...

for unsuccessful presidential candidate Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

. In May of that year, he engaged in a six-hour debate in Clarksville with Aaron Goodrich

Aaron Goodrich (6 July 1807 – 24 June 1887) was an American lawyer, jurist and diplomat.

Biography

Goodrich was born in Sempronius, New York, in 1807. In 1815, the family moved to a farm in western New York state, where Aaron attended country s ...

, elector for Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

.

Harris was nominated as the Democratic candidate for the state's 9th District seat in the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

in 1849. After successfully tying his opponent to unpopular positions of the national Whig Party, Harris won the election easily. He spent much of his term attacking the Compromise of 1850, though he also chaired the House Committee on Invalid Pensions. Harris was re-elected to a second term, but after Whigs gained control of the state legislature in 1851, his district was gerrymandered

In representative democracies, gerrymandering (, originally ) is the political manipulation of electoral district boundaries with the intent to create undue advantage for a party, group, or socioeconomic class within the constituency. The m ...

, and he did not seek a third term.

Governor of Tennessee

In 1856, Harris was chosen as the presidential elector for the state's at-large district, a position that required him to canvass the state on behalf of Democratic candidateJames Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

. He largely outshone the district's Whig elector, ex-Governor Neill S. Brown

Neill Smith Brown (April 18, 1810January 30, 1886) was an American politician and diplomat who served as the 12th Governor of Tennessee from 1847 to 1849, and as the United States Minister to Russia from 1850 to 1853. He also served several term ...

. This campaign elevated Harris to statewide prominence.

In 1857, Tennessee's Democratic governor,

In 1857, Tennessee's Democratic governor, Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

, was seriously injured in a train accident and was unable to run for reelection.Phillip Langsdon, ''Tennessee: A Political History'' (Franklin, Tenn.: Hillsboro Press, 2000), pp. 128, 134, 140–146, 150–154, 176. Harris was nominated as his replacement and embarked on a campaign that included a series of debates with his opponent, Robert H. Hatton

Robert Hopkins Hatton (November 2, 1826 – May 31, 1862) was a lawyer and politician from Tennessee. He was a state legislator and United States House of Representatives, US Representative, and a Confederate States Army, Confederate gene ...

. With sectional strife in Congress fueling both campaigns, these debates were often heated, and fights frequently broke out among spectators (and in one instance, between Harris and Hatton). Hatton was unable to distance himself from northern abolitionists, and Harris won the election by a vote of 71,178 to 59,807.

Harris's victory was not only the death knell for the state's Know Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

s,Stanley Folmsbee, Robert Corlew, and Enoch Mitchell, ''Tennessee: A Short History'' (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1969), pp. 238–239, 314. who had briefly risen to prominence following the collapse of the national Whig Party, but also represented a shift in Tennessee politics toward the Democratic Party. During the previous two decades, Whigs and Democrats had been evenly matched statewide, with Whigs controlling East Tennessee

East Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. Geographically and socioculturally distinct, it comprises approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of Tennessee. East Tennessee consists of 33 count ...

, Democrats controlling Middle Tennessee

Middle Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that composes roughly the central portion of the state. It is delineated according to state law as 41 of the state's 95 counties. Middle Tennessee contains the s ...

, and the two parties evenly split in West Tennessee

West Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions (Tennessee), Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that roughly comprises the western quarter of the state. The region includes 21 counties between the Tennessee River, Tennessee and Miss ...

. The nationwide debate over the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

and the Dred Scott case

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; t ...

pushed the issue of slavery to the forefront in the mid-1850s, and the balance in West Tennessee was tipped in favor of the Democrats. Harris's 11,000 vote victory was relatively large, considering his predecessor, Johnson, had won by just over 2,000 votes in both 1853 and 1855.

In 1859, Harris ran for reelection against John Netherland

John Netherland (September 20, 1808 – October 4, 1887) was an American attorney and politician, active primarily in mid-19th century Tennessee. A leader of the state's Whigs, he served in both the Tennessee Senate and Tennessee House of R ...

, who had been nominated by a hodge-podge group of ex-Whigs, ex-Know Nothings, and disgruntled Democrats, known as the Opposition Party

Parliamentary opposition is a form of political opposition to a designated government, particularly in a Westminster-based parliamentary system. This article uses the term ''government'' as it is used in Parliamentary systems, i.e. meaning ''th ...

. Harris again campaigned on fears of northern domination, while Netherland argued that the U.S. Constitution provided the best protection for Southern rights, and thus it was in the state's interest to remain in the Union. On election day, Harris prevailed by over 8,000 votes. The Opposition Party, however, showed its strength by capturing 7 of the state's 10 congressional seats.

Secession and the Civil War

Harris endorsed

Harris endorsed John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier. He represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress and became the 14th and youngest-ever vice president of the United States. Serving ...

for president in 1860, and warned that the state must consider secession if the "reckless fanatics of the north" should gain control of the federal government. Following Lincoln's election in November, Harris convened a special session of the legislature on January 7, 1861, which ordered a statewide referendum on whether or not Tennessee should consider secession. Pro-Union newspapers assailed Harris's actions as treasonous. The Huntingdon

Huntingdon is a market town in the Huntingdonshire district in Cambridgeshire, England. The town was given its town charter by King John in 1205. It was the county town of the historic county of Huntingdonshire. Oliver Cromwell was born there ...

''Carroll Patriot'' wrote that Harris was more deserving of the gallows than Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold ( Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American military officer who served during the Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defect ...

. William "Parson" Brownlow, editor of the ''Knoxville Whig

The ''Whig'' was a polemical American newspaper published and edited by William G. "Parson" Brownlow (1805–1877) in the mid-nineteenth century. As its name implies, the paper's primary purpose was the promotion and defense of Whig Party p ...

'', particularly despised Harris, calling him "Eye Sham" and "King Harris," and slammed his actions as autocratic.E. Merton Coulter

Ellis Merton Coulter (1890–1981) was an American historian of the South, author, and a founding member of the Southern Historical Association. For four decades, he was a professor at the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia, where he was ...

, ''William G. Brownlow: Fighting Parson of the Southern Highlands'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 1999), pp. 146, 344. When the referendum was held in February, Tennesseans rejected secession by a vote of 68,000 to 59,000.

Following the Battle of Fort Sumter

The Battle of Fort Sumter (April 12–13, 1861) was the bombardment of Fort Sumter near Charleston, South Carolina by the South Carolina militia. It ended with the surrender by the United States Army, beginning the American Civil War.

Follo ...

in April 1861, President Lincoln ordered Harris to furnish 50,000 soldiers for the suppression of the rebellion. Reading his response to Lincoln before a raucous crowd in Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and the ...

on April 17, Harris said, "Not a single man will be furnished from Tennessee," and stated he would rather cut off his right arm than sign the order. On April 25, Harris addressed a special session of the state legislature, stating that the Union had been destroyed by the "bloody and tyrannical policies of the Presidential usurper," and called for an end to the state's ties to the United States. Shortly afterward, the legislature authorized Harris to enter into a compact with the new Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

.

In May 1861, Harris began organizing and raising soldiers for what would become the Army of Tennessee. That same month, a steamboat, the ''Hillman'', which was carrying a shipment of lead to Nashville from St. Louis, was seized by the Governor of Illinois

The governor of Illinois is the head of government of Illinois, and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by p ...

. In response, Harris seized $75,000 from the customs office in Nashville. On June 8, 1861, Tennesseans voted in favor of the Ordinance of Secession, 104,913 to 47,238. A group of pro-Union leaders in East Tennessee, which had rejected the Ordinance, petitioned Harris to allow the region to break away from the state and remain with the Union. Harris rejected this, and sent troops under Felix K. Zollicoffer

Felix Kirk Zollicoffer (May 19, 1812 – January 19, 1862) was an American newspaperman, slave owner, politician, and soldier. A three-term United States Congressman from Tennessee, an officer in the United States Army, and a Confederate States ...

into East Tennessee. In the gubernatorial election later that year, William H. Polk, brother of former President James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

, ran against Harris on a pro-Union ticket but was defeated 75,300 to 43,495.

The Union Army invaded Tennessee in November 1861 and had gained control of Nashville by February of the following year. Harris and the state legislature moved to Memphis, but after that city fell, Harris joined the staff of General Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) served as a general in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He saw extensive combat during his 34-year military career, figh ...

. At the Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh (also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing) was fought on April 6–7, 1862, in the American Civil War. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater. The battlefield i ...

on April 6, Harris found Johnston slumping in his saddle and asked if he was wounded, to which Johnston replied "Yes, and I fear seriously." Harris and other staff officers moved the general to a small ravine and attempted to render aid, but Johnston died within a few minutes. Harris and the others secretly moved his body to Shiloh Church so as not to dampen the morale of Confederate troops.

Harris spent the remainder of the war as an aide-de-camp on the staffs of various Confederate generals, among them Joseph E. Johnston, Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, serving in the Weste ...

, John B. Hood

John Bell Hood (June 1 or June 29, 1831 – August 30, 1879) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Although brave, Hood's impetuosity led to high losses among his troops as he moved up in rank. Bruce Catton wrote that "the dec ...

, and P. G. T. Beauregard

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (May 28, 1818 - February 20, 1893) was a Confederate general officer of Louisiana Creole descent who started the American Civil War by leading the attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Today, he is commonly ...

. Andrew Johnson was appointed military governor by President Lincoln in March 1862, though Harris was still recognized as governor by the Confederacy. In 1863, Tennessee's Confederates elected Robert L. Caruthers

Robert Looney Caruthers (July 31, 1800 – October 2, 1882) was an American judge, politician, and professor. He helped establish Cumberland University in 1842, serving as the first president of its board of trustees, and was a cofounder of ...

as a successor to Harris, but Caruthers never took office. Harris was still issuing edicts as governor as late as November 1864.

After the war, the United States Congress passed a joint resolution allowing the governor of Tennessee to offer a reward for the apprehension of Harris because he was "guilty of treason, perjury and theft". Brownlow, who had become governor, issued a warrant for the arrest of Harris

and placed a $5,000 bounty on him. Brownlow taunted Harris in the warrant, stating, "His eyes are deep and penetrating—a perfect index to a heart of a traitor—with the scowl and frown of a demon resting upon his brow. His study of mischief and the practice of crime have brought upon him premature baldness and a gray beard." He further noted that Harris "chews tobacco rapidly and is inordinately fond of liquors."

Harris fled to Mexico, where he and several other ex-Confederates attempted to rally with Emperor Maximilian

Maximilian, Maximillian or Maximiliaan (Maximilien in French) is a male given name.

The name " Max" is considered a shortening of "Maximilian" as well as of several other names.

List of people

Monarchs

*Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor (1459� ...

. After Maximilian's fall in 1867, however, Harris was again forced to flee, this time to England. Later that year, after learning Brownlow would rescind the warrant, Harris returned to Tennessee. Passing through Nashville, he called on Brownlow, who is said to have greeted him with the statement, "While the lamp holds out to burn, the vilest sinner may return." Afterward, he returned to Memphis to practice law.

United States Senate

By 1877, the Tennessee state legislature, which was once again controlled by Democrats, elected Harris to one of the state's U.S. Senate seats. One of his earliest assignments, in the

By 1877, the Tennessee state legislature, which was once again controlled by Democrats, elected Harris to one of the state's U.S. Senate seats. One of his earliest assignments, in the 46th Congress

The 46th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1879, ...

(1879–81), was the District of Columbia Committee. Subsequent assignments included the Committee on Epidemic Diseases in the 49th Congress through the 52nd Congress

The 52nd United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1891, ...

(1885–93) and the Committee on Private Land Claims in the 54th Congress

The 54th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1895, ...

(1895–97).

During his first term in the Senate, Harris became the leader of Tennessee's Bourbon Democrats, a wing of the Democratic Party that generally supported laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups. ...

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

and the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the la ...

. As such, Harris spent his early Senate career advocating strict constructionism and limited government, states' rights, and low tariffs. In 1884, he was interviewed by President-elect Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

for a cabinet position. In 1887, he gave an impassioned speech in favor of the repeal of the Tenure of Office Act. In 1890, Harris denounced the Lodge Bill

The Lodge Bill of 1890, also referred to as the Federal Elections Bill or by critics as the Lodge Force Bill, was a proposed bill to ensure the security of elections for U.S. Representatives.

It was drafted and proposed by Representative Henry Cab ...

, which would have protected voting rights for African-Americans in the South, arguing that it violated states' rights.

Though a Bourbon Democrat, Harris, representing an agrarian state, was also a "Silver Democrat", believing pro-silver policies protected farmers. He supported the Bland–Allison Act

The Bland–Allison Act, also referred to as the Grand Bland Plan of 1878, was an act of United States Congress requiring the U.S. Treasury to buy a certain amount of silver and put it into circulation as silver dollars. Though the bill was vetoe ...

of 1878, which authorized the federal government to purchase silver to prevent deflation in crop prices. He also supported the act's replacement, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act was a United States federal law

enacted on July 14, 1890.Charles Ramsdell Lingley, ''Since the Civil War'', first edition: New York, The Century Co., 1920, ix–635 p., . Re-issued: Plain Label Books, unknown date, ...

of 1890. In 1893, President Cleveland, concerned that the Sherman Act was depleting the U.S. gold supply, sought its repeal. When the vote came up in the Senate in October, Harris, as president pro tempore, launched a filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

in hopes of preventing the act's repeal, but was unsuccessful. Disgruntled over the repeal of the Sherman Act, Harris campaigned for unsuccessful presidential candidate and gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the la ...

opponent William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

in 1896.

Death

Harris died in office on July 8, 1897. His funeral was held in the Senate chamber of the United States Capitol. Congressman

Harris died in office on July 8, 1897. His funeral was held in the Senate chamber of the United States Capitol. Congressman Walter P. Brownlow

Walter Preston Brownlow (March 27, 1851 – July 8, 1910) was an American politician who represented Tennessee's 1st district in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1897 until his death in 1910. He is remembered for obtaining large feder ...

, a nephew of Harris' old rival Parson Brownlow, was among those who delivered a memorial address in his honor.Walter P. Brownlow,Memorial Address for Isham G. Harris

(Government Printing Office, 1898), pp. 105-115. He is interred at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee.

See also

*List of governors of Tennessee

The term of the governor of Tennessee is limited by the state constitution. The first constitution, enacted in 1796, set a term of two years for the governor and provided that no person could serve as governor for more than 6 years in any 8-year ...

* List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

The following is a list of United States senators and representatives who died of natural or accidental causes, or who killed themselves, while serving their terms between 1790 and 1899. For a list of members of Congress who were killed while in ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* Elliott, Sam Davis. ''Isham G. Harris of Tennessee: Confederate Governor and United Senator''. Baton Rouge, LA.:Louisiana State University Press

The Louisiana State University Press (LSU Press) is a university press at Louisiana State University. Founded in 1935, it publishes works of scholarship as well as general interest books. LSU Press is a member of the Association of American Univer ...

, 2009

* Hall, Kermit L in ''The Confederate Governors.'' edited by Yearns, W. Buck. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1985

External links

* Retrieved on 2008-02-13Governor Isham G. Harris, 1857-1862

at Tennessee State Library and Archives {{DEFAULTSORT:Harris, Isham Green 1818 births 1897 deaths People from Franklin County, Tennessee Burials in Tennessee Albert Sidney Johnston Confederate States Army officers Governors of Tennessee Tennessee state senators People of Tennessee in the American Civil War Democratic Party United States senators from Tennessee Confederate States of America state governors Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Tennessee Democratic Party governors of Tennessee American slave owners 19th-century American politicians Presidents pro tempore of the United States Senate People from Ripley, Mississippi Bourbon Democrats Southern Historical Society United States senators who owned slaves