Ischia (island) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

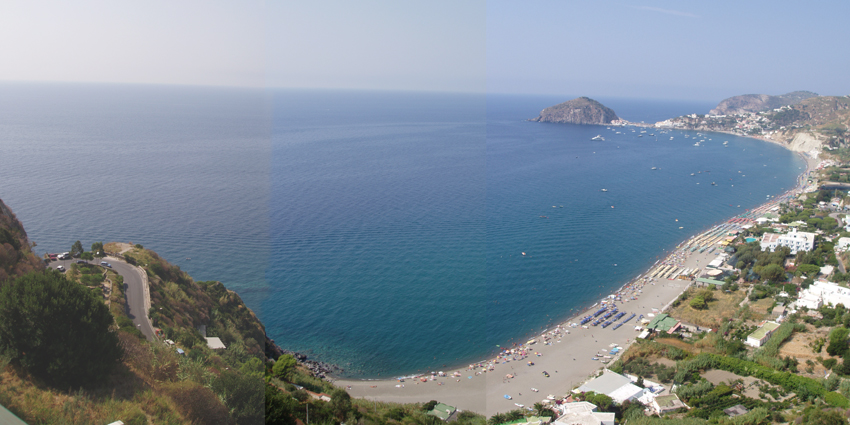

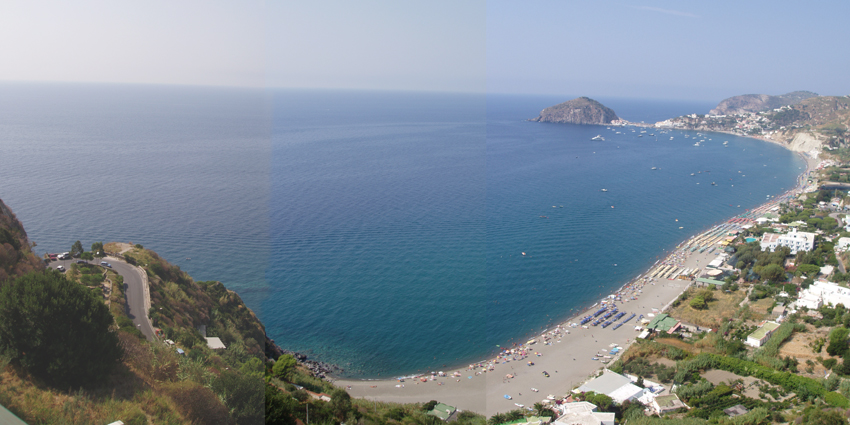

Ischia ( , , ) is a

Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) feeding ground in the coastal waters of Ischia (Archipelago Campano)

(pdf). The European Cetacean Society. Retrieved on March 28, 2017 From its roughly trapezoidal shape, the island is approximately 18 nautical miles from

The

The

In 6 AD,

In 6 AD,

Associazione Nemo

per la Diffusione della Cultura del Mare, via Regina Elena, 75 Cellulare: 366–1270197 *Associazione Progetto Emmaus, Via Acquedotto, 65 *A.V.I. Associazione Volontariato e Protezione Civile Isola D'Ischia, Via Delle Terme, 88 *Cooperativa Sociale Arkè onlus, Via delle Terme, 76/R Telefono: 081–981342 *Cooperativa Sociale Asat Ischia onlus, Via delle Terme, 76/R Telefono: 081–3334228 *Cooperativa Sociale kairòs onlus, Via delle Terme, 76/R *Kalimera Società Cooperativa Sociale, Via Fondo Bosso, 20 *Pan Assoverdi Salvanatura, Via Delle Terme, 53/C *Prima Ischia – Onlus, Via Iasolino, 102

February 15, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2008.Richard Thompson

"Looking to strengthen family ties with 'sister cities',"

''Boston Globe'', October 12, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2008. * Maloyaroslavets, Russia

Richard Stillwell, ed. ''Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites'', 1976:

"Aenaria (Ischia), Italy". * Ridgway, D. "The First Western Greeks" Cambridge University Press, 1993. *

Visit Ischia Official Tourist Board

n*

Ischia Photos with maps

n

Archaeology of Ischia

{{Authority control Calderas of Italy Campanian volcanic arc Castles in Italy Complex volcanoes Euboean colonies of Magna Graecia Geography of the Metropolitan City of Naples Islands of Campania Mediterranean islands Roman sites of Campania Stratovolcanoes of Italy Submarine calderas Tyrrhenian Sea VEI-6 volcanoes Volcanoes of the Tyrrhenian Wine regions of Italy

volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates a ...

island in the Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (; it, Mar Tirreno , french: Mer Tyrrhénienne , sc, Mare Tirrenu, co, Mari Tirrenu, scn, Mari Tirrenu, nap, Mare Tirreno) is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenian pe ...

. It lies at the northern end of the Gulf of Naples

The Gulf of Naples (), also called the Bay of Naples, is a roughly 15-kilometer-wide (9.3 mi) gulf located along the south-western coast of Italy (province of Naples, Campania region). It opens to the west into the Mediterranean Sea. It i ...

, about from the city of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

. It is the largest of the Phlegrean Islands. Although inhabited since the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, as a Greek emporium

Emporium may refer to:

Historical

* Emporium (antiquity), a trading post, factory, or market of Classical antiquity

* Emporium (early medieval), a 6th- to 9th-century trading settlement in Northwestern Europe

* Emporium (Italy), an ancient town ...

it was founded in the 8th or 9th century BCE, and known as Πιθηκοῦσαι, ''Pithekoūsai'' (Monkey Island).

Roughly trapezoid

A quadrilateral with at least one pair of parallel sides is called a trapezoid () in American and Canadian English. In British and other forms of English, it is called a trapezium ().

A trapezoid is necessarily a Convex polygon, convex quadri ...

al in shape, it measures approximately east to west and north to south and has about of coastline and a surface area of . It is almost entirely mountainous; the highest peak is Mount Epomeo, at . The island is very densely populated, with 60,000 residents (more than 1,300 inhabitants per square km). Ischia

Ischia ( , , ) is a volcanic island in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It lies at the northern end of the Gulf of Naples, about from Naples. It is the largest of the Phlegrean Islands. Roughly trapezoidal in shape, it measures approximately east to west ...

is the name of the main ''comune

The (; plural: ) is a local administrative division of Italy, roughly equivalent to a township or municipality. It is the third-level administrative division of Italy, after regions ('' regioni'') and provinces (''province''). The can also ...

'' of the island. The other ''comuni'' of the island are Barano d'Ischia, Casamicciola Terme, Forio, Lacco Ameno and Serrara Fontana.

Geology and geography

The roughly trapezoidal island is formed by a complex volcano immediately southwest of the Campi Flegrei area at the western side of theBay of Naples

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a gulf, sea, sound, or bight. A cove is a small, circular bay with a narr ...

. The eruption of the trachytic

Trachyte () is an extrusive igneous rock composed mostly of alkali feldspar. It is usually light-colored and aphanitic (fine-grained), with minor amounts of mafic minerals, and is formed by the rapid cooling of lava enriched with silica and alk ...

Green Tuff

Tuff is a type of rock made of volcanic ash ejected from a vent during a volcanic eruption. Following ejection and deposition, the ash is lithified into a solid rock. Rock that contains greater than 75% ash is considered tuff, while rock cont ...

Ignimbrite about 56,000 years ago was followed by the formation of a caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcano eruption. When large volumes of magma are erupted over a short time, structural support for the rock above the magma chamber is ...

comprising almost the entire island and some of the surrounding seabed. The highest point of the island, Monte Epomeo

Mount Epomeo (Italian: ''Monte Epomeo'') is the highest mountain on the volcanic island of Ischia, in the Gulf of Naples, Italy. Epomeo is believed to be a volcanic horst.

Reaching a height of , it towers above the rest of Ischia. Much of Epome ...

(), is a volcanic horst consisting of green tuff that was submerged after its eruption and then uplift

Uplift may refer to: Science

* Geologic uplift, a geological process

** Tectonic uplift, a geological process

* Stellar uplift, the theoretical prospect of moving a stellar mass

* Uplift mountains

* Llano Uplift

* Nemaha Uplift

Business

* Uplif ...

ed. Volcanism on the island has been significantly affected by tectonism that formed a series of horsts and graben

In geology, a graben () is a depressed block of the crust of a planet or moon, bordered by parallel normal faults.

Etymology

''Graben'' is a loan word from German, meaning 'ditch' or 'trench'. The word was first used in the geologic contex ...

s; resurgent doming produced at least of uplift during the past 33,000 years. Many small monogenetic volcanoes formed around the uplifted block. Volcanism during the Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togethe ...

produced a series of pumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of highly vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicular vol ...

ous tephra

Tephra is fragmental material produced by a volcanic eruption regardless of composition, fragment size, or emplacement mechanism.

Volcanologists also refer to airborne fragments as pyroclasts. Once clasts have fallen to the ground, they rem ...

s, tuff rings, lava dome

In volcanology, a lava dome is a circular mound-shaped protrusion resulting from the slow extrusion of viscous lava from a volcano. Dome-building eruptions are common, particularly in convergent plate boundary settings. Around 6% of eruptions on ...

s, and lava flow

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land or und ...

s. The last eruption of Ischia, in 1302, produced a spatter cone and the Arso lava flow, which reached the NE coast.

The surrounding waters including gulfs of Gaeta

Gaeta (; lat, Cāiēta; Southern Laziale: ''Gaieta'') is a city in the province of Latina, in Lazio, Southern Italy. Set on a promontory stretching towards the Gulf of Gaeta, it is from Rome and from Naples.

The town has played a consp ...

, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and Pozzuoli

Pozzuoli (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Naples, in the Italian region of Campania. It is the main city of the Phlegrean Peninsula.

History

Pozzuoli began as the Greek colony of ''Dicaearchia'' ( el, Δικα� ...

are both rich and healthy, providing a habitat for around 7 species of whales and dolphins including gigantic fin

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foils that produce lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while traveling in water, air, or other fluids. Fin ...

and sperm

Sperm is the male reproductive cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm with a tail known as a flagellum, whi ...

whales. Special research programmes on local cetaceans have been conducted to monitor and protect this bio-diversity.Mussi B.. Miragliuolo A.. Monzini E.. Battaglia M.. 1999Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) feeding ground in the coastal waters of Ischia (Archipelago Campano)

(pdf). The European Cetacean Society. Retrieved on March 28, 2017 From its roughly trapezoidal shape, the island is approximately 18 nautical miles from

Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, 10 km wide from east to west, 7 km from north to south, with a coastline of 43 km and an area of approximately 46.3 km2. The highest elevation is Monte Epomeo

Mount Epomeo (Italian: ''Monte Epomeo'') is the highest mountain on the volcanic island of Ischia, in the Gulf of Naples, Italy. Epomeo is believed to be a volcanic horst.

Reaching a height of , it towers above the rest of Ischia. Much of Epome ...

, standing at 788 meters and located in the center of the island. This is an horst, a tectonic volcano, meaning a block of the Earth's crust that has been uplifted compared to the surrounding crust due to magmatic pressure (horst is a German term meaning "rock"). Monte Epomeo is mistakenly thought of as a volcano, although it lacks any volcanic characteristics. Island volcanism, in fact, is particularly prevalent along the fractures that border the horst, namely Monte Epomeo.

Strabo reports what the Greek historian Timeo said about a tsunami that occurred in Ischia shortly before his time. Following the volcanic activity of Epomeo, "...the sea receded for three stages; afterwards (...) it turned back again and its ebb tide submerged the island (...) those who lived on the mainland fled from the coast into the interior of Campania" (Geography V, 4, 9). Cumae, not far from that coast, in Greek means "wave". Volcanic activity on Ischia has generally been characterized by eruptions that were not very significant and occurred at great intervals. After eruptions in Greek and Roman times, the last one occurred in 1302 in the eastern sector of the island with a brief flow (known as Arso) reaching the sea.

Name

The

The Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

called their colony on the island Pithekoussai (Πιθηκοῦσσαι), from which the Latin name Pithecusa was derived. The name has an uncertain etymology

Etymology ()The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p. 633 "Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time". is the study of the history of the Phonological chan ...

. According to Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

(Metamorphoses 14.92) and the Alexandrian historian Senagora, the name would derive from pithekos, monkey, and refer to the myth of the Cercopes

In Greek mythology, the Cercopes ( el, Κέρκωπες, plural of Κέρκωψ, from κέρκος (''n''.) ''kerkos'' "tail") were mischievous forest creatures who lived in Thermopylae or on Euboea but roamed the world and might turn up anywhe ...

, inhabitants of the Phlegraean islands transformed by Zeus into monkeys. More plausible is the interpretation of Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

(Nat. Hist. 111, 6.82), who instead derives the name from pythos, amphora, a theory supported by archaeological finds that testify to the Greek-Italic production of ceramics (and in particular of wine amphorae) on the island and in the Gulf of Naples.

It has also been proposed that the name describes a characteristic of the island, rich in pine forests. "Pitueois" (rich in pines), "pituis" (pine cone), "pissa, pitta" (resin) appear as descriptive terms from which Pithekoussai could derive, meaning "island of resin

In polymer chemistry and materials science, resin is a solid or highly viscous substance of plant or synthetic origin that is typically convertible into polymers. Resins are usually mixtures of organic compounds. This article focuses on natu ...

," an important substance used, among other things, to waterproof wine vessels. The name Aenaria, also used by the Latins, is linked to metallurgical workshops (from aenus, metal) located on the eastern coast, under the castle.

The first evidence of the island's current toponym dates back to the year 812

__NOTOC__

Year 812 ( DCCCXII) was a leap year starting on Thursday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* January 11 – Ex-emperor Staurakios, a son of Nikephoros I, dies ...

, in a letter from Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position b ...

in which he informs Emperor Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Emp ...

of devastations that occurred in the area, calling the island Iscla maior: "Ingressi sunt ipsi nefandissimi Mauri ..in insulam, quae dicitur Iscla maiore, non longe a Neapolitana urbe." Some scholars connect the term to the Phoenician word, and therefore Semitic i-schra, "black island." The Phoenician presence on the island is archaeologically documented from a very ancient era and, as reported by Moscati (an Italian historian), in the spread in Campania and southern Etruria, since the 8th century BC, of objects of Egyptian production or inspiration, "the Phoenician merchants settled in Ischia and then frequented the Tyrrhenian coasts" certainly played a part.

On the other hand, the modern "Island of Ischia" could derive from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

"insula visca" – compare the Greek noun (ϝ)ἰξός, (w)ixós, (mistletoe) and the adjective (ϝ)ἰξώδης, (w)ixṓdēs, (viscous, sticky), which as usual have lost the initial digamma. In favor of this theory could be the fact that in the same area, at the foot of Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ; it, Vesuvio ; nap, 'O Vesuvio , also or ; la, Vesuvius , also , or ) is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples

The Gulf of Naples (), also called the Bay of Naples, is a roughly 15-kilometer-wide (9 ...

covered with pines

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden accep ...

, the popular name of Herculaneum was "Resìna," perhaps reminiscent of an ancient market for this product, similarly to the toponym "Pizzo" in Calabria, from where the best resin, the "pece brettia" obtained from the pines of the nearby Sila, came from.

Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

poetically referred to it as ''Inarime'' and still later as ''Arime''. Martianus Capella followed Virgil in this allusive name, which was never in common circulation: the Romans called it ''Aenaria'', the Greeks, Πιθηκοῦσαι, ''Pithekoūsai''.

''(In)arime'' and ''Pithekousai'' both appear to derive from words for "monkey" (Etruscan __NOTOC__

Etruscan may refer to:

Ancient civilization

*The Etruscan language, an extinct language in ancient Italy

*Something derived from or related to the Etruscan civilization

**Etruscan architecture

**Etruscan art

**Etruscan cities

**Etruscan ...

''arimos'', Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

πίθηκος, ''píthēkos'', "monkey"). However, Pliny derives the Greek name from the local clay deposits, not from ''píthēkos''; he explains the Latin name ''Aenaria'' as connected to a landing by Aeneas

In Greco-Roman mythology, Aeneas (, ; from ) was a Trojan hero, the son of the Trojan prince Anchises and the Greek goddess Aphrodite (equivalent to the Roman Venus). His father was a first cousin of King Priam of Troy (both being grandsons ...

(''Princeton Encyclopedia''). If the island actually was, like Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, home to a population of monkeys, they were already extinct by historical times as no record of them is mentioned in ancient sources.

The current name appears for the first time in a letter from Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position b ...

to Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

in 813: the name ''iscla'' mentioned there would allegedly derive from ''insula'', though there is an argument made for a Semitic origin in ''I-schra'', "black island".

History

Ancient times

An acropolis site of the Monte Vico area was inhabited from theBronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, as Mycenaean and Iron Age pottery findings attest. Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

n Greeks from Eretria and Chalcis

Chalcis ( ; Ancient Greek & Katharevousa: , ) or Chalkida, also spelled Halkida (Modern Greek: , ), is the chief town of the island of Euboea or Evia in Greece, situated on the Euripus Strait at its narrowest point. The name is preserved from ...

arrived in the 8th century BC to establish an emporium

Emporium may refer to:

Historical

* Emporium (antiquity), a trading post, factory, or market of Classical antiquity

* Emporium (early medieval), a 6th- to 9th-century trading settlement in Northwestern Europe

* Emporium (Italy), an ancient town ...

for trade with the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, rou ...

of the mainland. This settlement was home to a mixed population of Greeks, Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, rou ...

, and Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns. Because of its fine harbor and the safety from raids afforded by the sea, the settlement of Pithecusae became successful through trade in iron and with mainland Italy; in 700 BC Pithecusae was home to 5,000–10,000 people.

The ceramic Euboean artifact inscribed with a reference to " Nestor's Cup" was discovered in a grave on the island in 1953. Engraved upon the cup are a few lines written in the Greek alphabet

The Greek alphabet has been used to write the Greek language since the late 9th or early 8th century BCE. It is derived from the earlier Phoenician alphabet, and was the earliest known alphabetic script to have distinct letters for vowels as we ...

. Dating from c. 730 BC, it is one of the most important testimonies to the early Greek alphabet, from which the Latin alphabet descended via the Etruscan alphabet. According to certain scholars the inscription also might be the oldest written reference to the Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odysse ...

.

In 474 BC, Hiero I of Syracuse

Hieron I ( el, Ἱέρων Α΄; usually Latinized Hiero) was the son of Deinomenes, the brother of Gelon and tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily from 478 to 467 BC. In succeeding Gelon, he conspired against a third brother, Polyzelos.

Life

During hi ...

came to the aid of the Cumaeans, who lived on the mainland opposite Ischia, against the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, rou ...

and defeated them on the sea. He occupied Ischia and the surrounding Parthenopean islands and left behind a garrison to build a fortress before the city of Ischia itself. This was still extant in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, but the original garrison fled before the eruptions of 470 BC and the island was taken over by Neapolitans. The Romans seized Ischia (and Naples) in 322 BC.

From 1st century AD to 16th century

In 6 AD,

In 6 AD, Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

restored the island to Naples in exchange for Capri

Capri ( , ; ; ) is an island located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the Sorrento Peninsula, on the south side of the Gulf of Naples in the Campania region of Italy. The main town of Capri that is located on the island shares the name. It has been ...

. Ischia suffered from the barbarian

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either Civilization, uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by som ...

invasions, being taken first by the Heruli then by the Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the larg ...

, being ultimately absorbed into the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. The Byzantines gave the island over to Naples in 588 and by 661 it was being administered by a Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

liege to the Duke of Naples

The Dukes of Naples were the military commanders of the ''ducatus Neapolitanus'', a Byzantine outpost in Italy, one of the few remaining after the conquest of the Lombards. In 661, Emperor Constans II, highly interested in south Italian affairs (h ...

. The area was devastated by the Saracens

file:Erhard Reuwich Sarazenen 1486.png, upright 1.5, Late 15th-century Germany in the Middle Ages, German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek language, Greek and Latin writings, to refer ...

in 813 and 847; in 1004 it was occupied by Henry II of Germany; the Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

Roger II of Sicily

Roger II ( it, Ruggero II; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Sicily and Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily

Roger I ( it, Ruggero I, Arabic: ''رُجار'', ''Rujār''; Maltese: ''Ruġġieru'', – 22 June 1101), nicknamed Rog ...

took it in 1130 granting the island to the Norman Aldoyn de Candida created Count d’Ischia; the island was raided by the Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the cit ...

ns in 1135 and 1137 and subsequently fell under the Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynasty ...

and then Angevin rule. After the Sicilian Vespers

The Sicilian Vespers ( it, Vespri siciliani; scn, Vespiri siciliani) was a successful rebellion on the island of Sicily that broke out at Easter 1282 against the rule of the French-born king Charles I of Anjou, who had ruled the Kingdom of S ...

in 1282, the island rebelled, recognizing Peter III of Aragon

Peter III of Aragon ( November 1285) was King of Aragon, King of Valencia (as ), and Count of Barcelona (as ) from 1276 to his death. At the invitation of some rebels, he conquered the Kingdom of Sicily and became King of Sicily in 1282, pres ...

, but was retaken by the Angevins the following year. It was conquered in 1284 by the forces of Aragon and Charles II of Anjou Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

*County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

**Duke ...

was unable to successfully retake it until 1299.

As a consequence of the island's last eruption in 1302, the population fled to Baia where they remained for 4 years. In 1320 Robert of Anjou and his wife Sancia visited the island and were hosted by Cesare Sterlich, who had been sent by Charles II from the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

to govern the island in 1306 and was by this time nearly 100 years of age.

Ischia suffered greatly in the struggles between the Angevin and Durazzo dynasties. It was taken by Carlo Durazzo

Charles the Short or Charles of Durazzo (1345 – 24 February 1386) was King of Naples and the titular King of Jerusalem from 1382 to 1386 as Charles II, and King of Hungary from 1385 to 1386 as Charles II. In 1381, Charles created the chivalr ...

in 1382, retaken by Louis II of Anjou in 1385 and captured yet again by Ladislaus of Naples in 1386; it was sacked by the fleet of the Antipope John XXIII under the command of Gaspare Cossa in 1410 only to be retaken by Ladislaus the following year. In 1422 Joan II gave the island to her adoptive son Alfonso V of Aragon

Alfonso the Magnanimous (139627 June 1458) was King of Aragon and King of Sicily (as Alfonso V) and the ruler of the Crown of Aragon from 1416 and King of Naples (as Alfonso I) from 1442 until his death. He was involved with struggles to the t ...

, though, when he fell into disgrace, she retook it with the help of Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

in 1424. In 1438 Alfonso reoccupied the castle, kicking out all the men and proclaiming it an Aragonese colony, marrying to his garrison the wives and daughters of the expelled. He set about building a bridge linking the castle to the rest of the island and he carved out a large gallery, both of which are still to be seen today. In 1442, he gave the island to one of his favorites, Lucretia d'Alagno, who in turn entrusted the island's governance to her brother-in-law, Giovanni Torella. Upon the death of Alfonso in 1458, they returned the island to the Angevin side. Ferdinand I of Naples

Ferdinando Trastámara d'Aragona, of the Naples branch, universally known as Ferrante and also called by his contemporaries Don Ferrando and Don Ferrante (2 June 1424, in Valencia – 25 January 1494, in Kingdom of Naples, Naples), was the only so ...

ordered Alessandro Sforza

The House of Sforza () was a ruling family of Renaissance Italy, based in Milan. They acquired the Duchy of Milan following the extinction of the Visconti family in the mid-15th century, Sforza rule ending in Milan with the death of the last mem ...

to chase Torella out of the castle and gave the island over, in 1462, to Garceraldo Requesens. In 1464, after a brief Torellan insurrection, Marino Caracciolo was set up as governor.

In February 1495, with the arrival of Charles VIII, Ferdinand II landed on the island and took possession of the castle, and, after having killed the disloyal castellan

A castellan is the title used in Medieval Europe for an appointed official, a governor of a castle and its surrounding territory referred to as the castellany. The title of ''governor'' is retained in the English prison system, as a remnant o ...

Giusto di Candida with his own hands, left the island under the control of Innico d'Avalos, marquis of Pescara

Pescara (; nap, label= Abruzzese, Pescàrë; nap, label= Pescarese, Piscàrë) is the capital city of the Province of Pescara, in the Abruzzo region of Italy. It is the most populated city in Abruzzo, with 119,217 (2018) residents (and approxim ...

and Vasto, who ably defended the place from the French flotilla. With him came his sister Costanza and through them they founded the D'Avalos dynasty which would last on the island into the 18th century.

16th–18th centuries

Throughout the 16th century, the island suffered the incursions of pirates and Barbaryprivateers

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

from North Africa: in 1543 and 1544 Hayreddin Barbarossa laid waste to the island, taking 4,000 prisoners in the process. In 1548 and 1552, Ischia was beset by his successor Dragut Rais. With the increasing rarity and diminishing severity of the piratical attacks later in the century and the construction of better defences, the islanders began to venture out of the castle and it was then that the historic centre of the town of Ischia was begun. Even so, many inhabitants still ended up slaves to the pirates, the last known being taken in 1796. During the 1647 revolution of Masaniello

Masaniello (, ; an abbreviation of Tommaso Aniello; 29 June 1620 – 16 July 1647) was an Italian fisherman who became leader of the 1647 revolt against the rule of Habsburg Spain in the Kingdom of Naples.

Name and place of birth

Until recent ...

, there was an attempted rebellion against the feudal landowners.

Since the 18th century

With the extinction of the D'Avalos line in 1729, the island reverted to state property. In March 1734 it was taken by theBourbons

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanish ...

and administered by a royal governor seated within the castle. The island participated in the short-lived Republic of Naples starting in March 1799 but by April 3 Commodore Thomas Troubridge under the command of Lord Nelson had put down the revolt on Ischia as well as on neighboring Procida. By decree of the governor, many of the rebels were hanged in a square on Procida now called Piazza dei martiri (Square of the Martyrs). Among these was Francesco Buonocore who had received the island to administer from the French Championnet in Naples. On February 13, 1806, the island was occupied by the French and on the 24th was unsuccessfully attacked by the British.

On June 21 and 22, 1809 the islands of Ischia and Procida were attacked by an Anglo-Bourbon fleet. Procida surrendered on June 24 and Ischia soon afterwards. However the British soon returned to their bases in Sicily and Malta.

In the 19th century Ischia was a popular travel destination for European nobility.

On July 28, 1883, an earthquake destroyed the villages of Casamicciola Terme and Lacco Ameno.

Ischia developed into a well-known artist colony at the beginning of the 20th century. Writers and painters from all over the world were attracted. Eduard Bargheer, Hans Purrmann

Hans Marsilius Purrmann (April 10, 1880 – April 17, 1966) was a German artist. He was born in Speyer where he also grew up. He completed an apprenticeship as a scene painter and interior decorator, and subsequently studied in Karlsruhe and ...

and Arrigo Wittler lived on the island. Rudolf Levy, Werner Gilles

Werner Gilles (29 August 1894 – 23 June 1961) was a German artist.

Gilles was born in Rheydt/Rheinland (today Mönchengladbach) He found his artistic calling while at the academies of Kassel and Weimar, studying under Lyonel Feininger of the ...

, Max Peiffer Watenphul

Max Peiffer Watenphul (1896 – 13 July 1976) was a German artist. Described as a "lyric poet of painting", he belongs to a "tradition of German painters for whom the Italian landscape represented Arcadia." In addition to Mediterranean scenes, he ...

with Kurt Craemer and Vincent Weber stayed in the fishing village of Sant'Angelo on the southern tip of the island shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War.

In 1936 Ischia had a population of 30,418.

Spa tourism did not start again until the early 1950s. At that time, a quite remarkable artist colony of writers, composers and visual artists lived in Forio, including Ingeborg Bachmann

Ingeborg Bachmann (25 June 1926 – 17 October 1973) was an Austrian poet and author.

Biography

Bachmann was born in Klagenfurt, in the Austrian state of Carinthia, the daughter of Olga (née Haas) and Matthias Bachmann, a schoolteacher. Her fa ...

. Elizabeth Taylor

Dame Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor (February 27, 1932 – March 23, 2011) was a British-American actress. She began her career as a child actress in the early 1940s and was one of the most popular stars of classical Hollywood cinema in the 1950s. ...

and Luchino Visconti stayed here for filming.

On August 21, 2017, Ischia had an 4.2 magnitude earthquake which killed 2 people and injured 42 more.

Today, Ischia is a popular tourist destination, welcoming up to 6 million visitors per year, mainly from the Italian mainland as well as other European countries like Germany and the United Kingdom (approximately 5,000 Germans are resident on the island), although it has become an increasingly popular destination for Eastern Europeans. The number of Russian guests rose steadily from the 2000s onwards, before the number came to an almost complete standstill due to the currency depreciation of the ruble and COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identif ...

.

From Ischia, various destinations such as Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ; it, Vesuvio ; nap, 'O Vesuvio , also or ; la, Vesuvius , also , or ) is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples

The Gulf of Naples (), also called the Bay of Naples, is a roughly 15-kilometer-wide (9 ...

, Amalfi Coast

The Amalfi Coast ( it, Costiera amalfitana) is a stretch of coastline in southern Italy overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Gulf of Salerno. It is located south of the Sorrentine Peninsula and north of the Cilentan Coast.

Celebrated worldwide ...

, Capri

Capri ( , ; ; ) is an island located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the Sorrento Peninsula, on the south side of the Gulf of Naples in the Campania region of Italy. The main town of Capri that is located on the island shares the name. It has been ...

, Herculaneum

Herculaneum (; Neapolitan and it, Ercolano) was an ancient town, located in the modern-day ''comune'' of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Like the nea ...

, Paestum and the neighboring island Procida can be booked.

Ischia is easily reached by ferry from Naples. The number of thermal spas on the islands makes it particularly popular with tourists seeking "wellness" holidays. A regular visitor was Angela Merkel, the former German chancellor.

In literature and the arts

Events

The island is home to theIschia Film Festival

The Ischia Film Festival is an annual film festival held in Ischia, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterrane ...

, an international cinema competition celebrated in June or July, dedicated to all the works that have promoted the value of the local territory.

Notable guests and works

*The Italian politicianGiuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patr ...

, one of the most important figures of Italian unification, stayed on the island for healing himself from a serious injury and finding relief in the peaceful area of Casamicciola Terme (at the Manzi Hotel).

*The Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin, stayed in Ischia between July 1866 and June 1867, from where he wrote political letters to Alexander Herzen and Nikolai Ogarev

Nikolay Platonovich Ogarev (Ogaryov; ; – ) was a Russian poet, historian and political activist. He was deeply critical of the limitations of the Emancipation reform of 1861 claiming that the serfs were not free but had simply exchanged one f ...

.

*In May 1948 W. H. Auden wrote his poem "In Praise of Limestone

"In Praise of Limestone" is a poem written by W. H. Auden in Italy in May 1948. Central to his canon and one of Auden's finest poems, it has been the subject of diverse scholarly interpretations. Auden's limestone landscape has been interpreted ...

" here, the first poem he wrote in Italy.

*In 1949, British classical composer William Walton settled in Ischia. In 1956, he sold his London house and took up full-time residence on Ischia; he built a hilltop house at Forio, called it La Mortella, and Susana Walton created a magnificent garden there. Walton lived on the island for the remainder of his life and died there in 1983.

* German composer Hans Werner Henze lived on the island from 1953 to 1956 and wrote his ''Quattro Poemi'' (1955) there.

* Samuel Taylor's Broadway play ''Avanti!

''Avanti!'' is a 1972 American/Italian international co-production comedy film produced and directed by Billy Wilder, and starring Jack Lemmon and Juliet Mills. The screenplay by Wilder and I. A. L. Diamond is based on Samuel A. Taylor's play, w ...

'' (1968) takes place on the island.

* Hergé's series of comic albums, ''The Adventures of Tintin

''The Adventures of Tintin'' (french: Les Aventures de Tintin ) is a series of 24 bande dessinée#Formats, ''bande dessinée'' albums created by Belgians, Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi, who wrote under the pen name Hergé. The series was one ...

'' (1907–1983), ends in Ischia, which serves as the location of Endaddine Akass' villa in the unfinished 24th and final book, '' Tintin and Alph-Art''.

* French novelist Pascal Quignard

Pascal Quignard (; born 23 April 1948) is a French writer born in Verneuil-sur-Avre, Eure. In 2002 his novel ''Les Ombres errantes'' won the Prix Goncourt, France's top literary prize. ''Terrasse à Rome'' (Terrasse in Rome), received the Fren ...

set much of his novel '' Villa Amalia'' (2006) on the island.

*In Elena Ferrante's series of Neapolitan Novels

The Neapolitan Novels, also known as the Neapolitan Quartet, are a four-part series of fiction by the pseudonymous Italian author Elena Ferrante, published originally by Edizioni e/o, translated into English by Ann Goldstein, and published by Eu ...

, the island serves as the setting of several summer holidays of the main characters.

Film setting

In addition to the works noted above, multiple media works have been set or filmed on the island. For example: * The Americanswashbuckler film

Swashbuckler films are a subgenre of the action film genre, often characterised by swordfighting and adventurous heroic characters, known as swashbucklers. Real historical events often feature prominently in the plot, morality is often clear-c ...

''The Crimson Pirate

''The Crimson Pirate'' is a 1952 British-American international co-production Technicolor tongue-in-cheek comedy-adventure film from Warner Bros. produced by Norman Deming and Harold Hecht, directed by Robert Siodmak, and starring Burt Lancaste ...

'' (1952) was filmed on and around the island during the summer of 1951.

* Part of ''Purple Noon

''Purple Noon'' (french: Plein soleil; it, Delitto in pieno sole; also known as ''Full Sun'', ''Blazing Sun'', ''Lust for Evil'', and ''Talented Mr. Ripley'') is a 1960 crime thriller film directed by René Clément, loosely based on the 1955 nove ...

'' ("Plein Soleil", 1959), directed by René Clément

René Clément (; 18 March 1913 – 17 March 1996) was a French film director and screenwriter.

Life and career

Clément studied architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts where he developed an interest in filmmaking. In 1936, he directed hi ...

starring Alain Delon

Alain Fabien Maurice Marcel Delon (; born 8 November 1935) is a French actor and filmmaker. He was one of Europe's most prominent actors and screen sex symbols in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. In 1985, he won the César Award for Best Actor for h ...

and Marie Laforêt

* ''Avanti!

''Avanti!'' is a 1972 American/Italian international co-production comedy film produced and directed by Billy Wilder, and starring Jack Lemmon and Juliet Mills. The screenplay by Wilder and I. A. L. Diamond is based on Samuel A. Taylor's play, w ...

'' (1972), starring Jack Lemon and Juliet Mills.

* Part of ''Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler.She was also a ...

'' (1963), starring Elizabeth Taylor

Dame Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor (February 27, 1932 – March 23, 2011) was a British-American actress. She began her career as a child actress in the early 1940s and was one of the most popular stars of classical Hollywood cinema in the 1950s. ...

, was filmed on the island.

* Ischia Ponte stood in for "Mongibello" in the Hollywood film of ''The Talented Mr. Ripley

''The Talented Mr. Ripley'' is a 1955 psychological thriller novel by Patricia Highsmith. This novel introduced the character of Tom Ripley, who returns in four subsequent novels. It has been adapted numerous times for screen, including ''Purpl ...

'' (1999).

* The American film ''And While We Were Here

''And While We Were Here'' is a 2012 American romantic drama film written and directed by Kat Coiro and starring Kate Bosworth, Jamie Blackley and Iddo Goldberg. It was filmed on the island of Ischia. The film premiered at the 2012 Tribeca Film Fe ...

'' (2012), starring Kate Bosworth, was filmed on the island.

* Castello Aragonese

Aragonese Castle ( it, Castello Aragonese) is a castle next to Ischia (one of the Phlegraean Islands), at the northern end of the Gulf of Naples, Italy. The castle stands on a volcanic rocky islet that connects to the larger island of Ischia by a ...

was used as the 'Riva's Fortified Fortress' island in '' Men in Black: International'' (2019).

Wines

The island of Ischia is home to the eponymous '' Denominazione di origine controllata'' (DOC) that produces both red and white wines though white wines account for nearly 80% of the island's wine production. Vineyards planted within the boundaries of the DOC tend to be on volcanic soils with highpumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of highly vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicular vol ...

, phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ear ...

and potassium

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin ''kalium'') and atomic number19. Potassium is a silvery-white metal that is soft enough to be cut with a knife with little force. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmosphe ...

content.

The white wines of the island are composed primarily of Forastera

Forastera is a white Italian wine grape variety that is grown on the islands of Ischia and Procida off the coast of Naples in Campania. In the early 21st century, DNA analysis confirmed that the Spanish wine grape variety of the same name grown ...

(at least 65% according to DOC regulation) and Biancolella

Biancolella is a white Italian wine grape variety grown primarily in the Campania region of southern Italy. It is a permitted grape in a few Campanian ''Denominazione di origine controllata

The following four classifications of wine constitute ...

(up to 20%) with up to 15% of other local grape varieties such as Arilla

Arilla is a white Italian wine grape variety that is grown on the island of Ischia in the Tyrrhenian Sea near the Gulf of Naples. However, despite being exclusively found on the island, ampelographers believe that the grape may have actually origi ...

and San Lunardo. Grapes are limited to a harvest

Harvesting is the process of gathering a ripe crop from the fields. Reaping is the cutting of grain or pulse for harvest, typically using a scythe, sickle, or reaper. On smaller farms with minimal mechanization, harvesting is the most labor-i ...

yield of no more than 10 tonnes/ha with a finished minimum alcohol level of at least 11%. For wines labeled as ''Bianco Superiore'', the yield is further restricted to a maximum of 8 tonnes/ha with a minimum alcohol level of 12%. Only certain subareas of the Ischia DOC can produce ''Bianco Superiore'' with the blend needing to contain 50% Forastera, 40% Biancolella and 10% San Lunardo.

Red wines produced under the Ischia DOC are composed of 50% Guarnaccia, 40% Piedirosso

Piedirosso is a red Italian wine grape variety that is planted primarily in the Campania region. The grape is considered a specialty of the region, being used to produce wines for local and tourist consumption. Its name "piedirosso" means "red f ...

(known under the local synonym of Per'e Palummo) and 10% Barbera. Like the white wines, red grapes destined for DOC production are limited to a harvest yield of no more than 10 tonnes/ha though the minimum finished alcohol level is higher at 11.5% ABV.

Main sights

Aragonese Castle

TheAragonese Castle

Aragonese Castle ( it, Castello Aragonese) is a castle next to Ischia (one of the Phlegraean Islands), at the northern end of the Gulf of Naples, Italy. The castle stands on a volcanic rocky islet that connects to the larger island of Ischia by a ...

(''Castello Aragonese'', Ischia Ponte) was built on a rock near the island in 474 BC, by Hiero I of Syracuse

Hieron I ( el, Ἱέρων Α΄; usually Latinized Hiero) was the son of Deinomenes, the brother of Gelon and tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily from 478 to 467 BC. In succeeding Gelon, he conspired against a third brother, Polyzelos.

Life

During hi ...

. At the same time, two towers were built to control enemy fleets' movements. The rock was then occupied by Parthenopeans (the ancient inhabitants of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

). In 326 BC the fortress was captured by Romans, and then again by the Parthenopeans. In 1441 Alfonso V of Aragon

Alfonso the Magnanimous (139627 June 1458) was King of Aragon and King of Sicily (as Alfonso V) and the ruler of the Crown of Aragon from 1416 and King of Naples (as Alfonso I) from 1442 until his death. He was involved with struggles to the t ...

connected the rock to the island with a stone bridge instead of the prior wood bridge, and fortified the walls to defend the inhabitants against the raids of pirates

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

. Around 1700, about 2000 families lived on the islet, including a Poor Clares convent, an abbey of Basilian monks

Basilian monks are Roman Catholic monks who follow the rule of Basil the Great, bishop of Caesarea (330–379). The term 'Basilian' is typically used only in the Catholic Church to distinguish Greek Catholic monks from other forms of monastic li ...

(of the Greek Orthodox Church

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also call ...

), the bishop and the seminar, and the prince, with a military garrison. There were also thirteen churches. In 1912, the castle was sold to a private owner. Today the castle is the most visited monument of the island. It is accessed through a tunnel with large openings which let the light enter. Along the tunnel there is a small chapel consecrated to Saint John Joseph of the Cross (San Giovan Giuseppe della Croce), the patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or perso ...

of the island. A more comfortable access is also possible with a modern lift. After arriving outside, it is possible to visit the Church of the Immacolata

The Immaculate Conception is the belief that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception.

It is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church, meaning that it is held to be a divinely revealed truth wh ...

and the Cathedral of Assunta

The Assumption of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Pope Pius XII defined it in 1950 in his apostolic constitution ''Munificentissimus Deus'' as follows:

We proclaim and define it to be a dogma revealed by Go ...

. The first was built in 1737 on the location of a smaller chapel dedicated to Saint Francis, and closed after the suppression of convents in 1806, as well as the Poor Clares convent.

Gardens of ''La Mortella''

The gardens, located in Forio-San Francesco, were originally the property of English composer William Walton. Walton lived in the villa next to the gardens with his Argentine wife Susana. When the composer arrived on the island in 1946, he immediately calledRussell Page

Montague Russell Page (1 November 1906 – 4 January 1985) was a British gardener, garden designer and landscape architect. He worked in the UK, western Europe and the United States of America.

Biography

Montague Russell Page was born in Lin ...

from England to lay out the garden. Wonderful tropical and Mediterranean plants were planted and some have now reached amazing proportions. The gardens include wonderful views over the city and harbour of Forio. A museum dedicated to the life and work of William Walton now comprises part of the garden complex. There's also a recital room where renowned musical artists perform on a regular schedule.

Villa La Colombaia

''Villa La Colombaia'' is located in Lacco Ameno and Forio territories. Surrounded by a park, the villa (called "The Dovecote") was made by Luigi Patalano, a famous localsocialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

and journalist. It is now the seat of a cultural institution and museum dedicated to Luchino Visconti. The institution promotes cultural activities such as music, cinema, theatre, art exhibitions, workshops and cinema reviews. The villa and the park are open to the public.

Others

* Sant'Angelo (Sant'Angelo, in the ''comune'' of Serrara Fontana) * Maronti Beach ( Barano d'Ischia) * Church of the Soccorso' ( Forio) * Piazza S.Restituta, with the best luxury boutiques ( Lacco Ameno) * Bay of Sorgeto, with hot thermal springs (Panza

Panza ''(sometimes Panza d'Ischia)'' is a small town of 7,000 inhabitants on the island of Ischia, Italy. It is a hamlet (''frazione'') of the municipality of Forio.

Name

According to archaeological discoveries the place was so named by the fi ...

)

* Poseidon Gardens – spa with several thermal pools (Panza

Panza ''(sometimes Panza d'Ischia)'' is a small town of 7,000 inhabitants on the island of Ischia, Italy. It is a hamlet (''frazione'') of the municipality of Forio.

Name

According to archaeological discoveries the place was so named by the fi ...

)

* Citara Beach (Panza

Panza ''(sometimes Panza d'Ischia)'' is a small town of 7,000 inhabitants on the island of Ischia, Italy. It is a hamlet (''frazione'') of the municipality of Forio.

Name

According to archaeological discoveries the place was so named by the fi ...

)

* English's Beach (Ischia

Ischia ( , , ) is a volcanic island in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It lies at the northern end of the Gulf of Naples, about from Naples. It is the largest of the Phlegrean Islands. Roughly trapezoidal in shape, it measures approximately east to west ...

)

* Pitthekoussai Archaeological museum

* The Angelo Rizzoli museum

Voluntary associations

Committees and associations work to promote tourism on the island, and provide services and activities for residents. Among these are: * Il coniglio di Rocco Alfarano, associazione per la protezione del quadrupede sull’isola *Accaparlante Società Cooperativa Sociale, Via Sant'Alessandro *Associazione Donatori Volontari di Sangue, Via Iasolino, 1Associazione Nemo

per la Diffusione della Cultura del Mare, via Regina Elena, 75 Cellulare: 366–1270197 *Associazione Progetto Emmaus, Via Acquedotto, 65 *A.V.I. Associazione Volontariato e Protezione Civile Isola D'Ischia, Via Delle Terme, 88 *Cooperativa Sociale Arkè onlus, Via delle Terme, 76/R Telefono: 081–981342 *Cooperativa Sociale Asat Ischia onlus, Via delle Terme, 76/R Telefono: 081–3334228 *Cooperativa Sociale kairòs onlus, Via delle Terme, 76/R *Kalimera Società Cooperativa Sociale, Via Fondo Bosso, 20 *Pan Assoverdi Salvanatura, Via Delle Terme, 53/C *Prima Ischia – Onlus, Via Iasolino, 102

Town twinning

* Los Angeles, US (2006) *Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

, USA (2006)"A Message from the Peace Commission: Information on Cambridge's Sister Cities,"February 15, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2008.Richard Thompson

"Looking to strengthen family ties with 'sister cities',"

''Boston Globe'', October 12, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2008. * Maloyaroslavets, Russia

Environmental problems

The sharp increase of the population between 1950 and 1980 and the growing inflow of tourists (in 2010 over 4 million tourists visited the island for at least one day) have increased the anthropic pressure on the island. Significant acreage of land previously used for agriculture has been developed for the construction of houses and residential structures. Most of this development has taken place without any planning and building permission. As at the end of 2011, the island lacked the most basic system for sewage treatment; sewage is sent directly to the sea. In 2004 one of the five communities of the island commenced civil works to build a sewage treatment plant but since then the construction has not been completed and it is currently stopped. On June 14, 2007, there was a breakage in one of the four high-voltage underwater cables forming the power line maintained by Enel S.p.A. — although never authorized by Italian authorities – between Cuma on the Campania coast and Lacco Ameno on the island of Ischia. Inside each cable there is an 18 mm‑diameter channel filled with oil under high pressure. The breakage of the Enel cable resulted in the spillage of oil into the sea and into other environmental matrices – with the consequent pollution by polychlorobiphenyls (PCBs, the use of which was banned by the Italian authorities as long ago as 1984), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and linear alkyl benzenes (aromatic hydrocarbons) — in the ‘Regno di Nettuno’, a marine protected area, and the largest ecosystem in the Mediterranean Sea, designated as a ‘priority habitat’ in Annex I to the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) and comprising oceanic posidonia beds. To reduce pollution due to cars, Ischia has been the place of the first complete sustainable mobility project applied to an urban center, created in 2017 with Enel in collaboration with Aldo Arcangioli, one the main Italian experts of green mobility, under the name of "Green Island".See also

* List of islands of Italy *List of castles in Italy

This is a list of castles in Italy by location.

Abruzzo

;Province of L'Aquila

*Castello normanno, Anversa degli Abruzzi

* Castello Orsini-Colonna, Avezzano

* Castello Piccolomini, Balsorano

*Castle of Barisciano, Barisciano

* Castello di Bar ...

* List of volcanoes in Italy

This is a list of active and extinct volcanoes in Italy.

See also

*Volcanology of Italy

* List of mountains of Italy

Notes

References

Global Volcanism Program

{{DEFAULTSORT:List Of Volcanoes In Italy

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), o ...

* Castello d'Ischia Lighthouse

Castello d'Ischia Lighthouse ( it, Faro di Castello d'Ischia) is an active lighthouse located in the municipality of Ischia, Campania on the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Description

The lighthouse was established in 1913 and consist of a lantern mounted on a ...

* 2017 Ischia earthquake

The 2017 Ischia earthquake occurred in the island of Ischia, Campania, in southern Italy. The main shock occurred at 20:57 CEST (18:57 UTC) on 21 August 2017, and was rated 3.9 or 4.2 on the moment magnitude scale.

Despite the moderate magni ...

References

Bibliography

Richard Stillwell, ed. ''Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites'', 1976:

"Aenaria (Ischia), Italy". * Ridgway, D. "The First Western Greeks" Cambridge University Press, 1993. *

External links

Visit Ischia Official Tourist Board

n*

Ischia Photos with maps

n

Archaeology of Ischia

{{Authority control Calderas of Italy Campanian volcanic arc Castles in Italy Complex volcanoes Euboean colonies of Magna Graecia Geography of the Metropolitan City of Naples Islands of Campania Mediterranean islands Roman sites of Campania Stratovolcanoes of Italy Submarine calderas Tyrrhenian Sea VEI-6 volcanoes Volcanoes of the Tyrrhenian Wine regions of Italy