Isabella Jones And Ira Junius Johnson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the Canadian town of

In the Canadian town of

Johnson's attestation paper from World War I

1930 in Canada Anti-black racism in Canada Ku Klux Klan in Canada People from Oakville, Ontario Marriage in Canada 1930 crimes in Canada 1930 in Ontario

In the Canadian town of

In the Canadian town of Oakville, Ontario

Oakville is a town in Regional Municipality of Halton, Halton Region, Ontario, Canada. It is located on Lake Ontario between Toronto and Hamilton, Ontario, Hamilton. At its Canada 2021 Census, 2021 census population of 213,759, it is List of tow ...

, on 28 February 1930, 75 members of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

attempted to prevent the marriage of a white woman, Isabella Jones, to Ira Junius Johnson, a man presumed to be Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

.

After burning a cross in the middle of a street in Oakville, the Klansmen searched for Johnson and Jones; they abducted Jones and threatened Johnson. Newspapers were sympathetic to the Klan at first, but the efforts of the Black community in Toronto turned public opinion against them; Johnson told the press that he was not Black, but of mixed White and Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

descent. Three Klansmen were brought to court. At first, only one was found guilty and fined $50; when he appealed, the court gave him a three-month sentence. Johnson and Jones married a month after the incident.

Background

Ira Junius Johnson's paternal grandfather George Branson Johnson was a free Black man fromMaryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

who migrated with his family of eleven children (including Ira Junius's father) to the Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British North America, British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham ...

in the 1860s, where they settled in Oakville. They may have used the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

to get there. Johnson's maternal grandfather Junius B. Roberts was from Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

and served in the African-American 28th Indiana Infantry Regiment during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. He later migrated to Canada and served as a minister in Guelph

Guelph ( ; 2021 Canadian Census population 143,740) is a city in Southwestern Ontario, Canada. Known as "The Royal City", Guelph is roughly east of Kitchener and west of Downtown Toronto, at the intersection of Highway 6, Highway 7 and Wel ...

, Oakville, and Hamilton Hamilton may refer to:

People

* Hamilton (name), a common British surname and occasional given name, usually of Scottish origin, including a list of persons with the surname

** The Duke of Hamilton, the premier peer of Scotland

** Lord Hamilt ...

for the British Methodist Episcopal Church

The British Methodist Episcopal Church (BMEC) is a Protestant church in Canada that has its roots in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AMEC) of the United States.

History

The AMEC had been formed in 1816 when a number of black congregations ...

. His wife Francis had Johnson's mother Ida in 1870. The Johnsons were members of the Church Roberts served in Oakville. Ida and John wed on 27 September 1887; John worked as a weaver, and Ida as a midwife

A midwife is a health professional who cares for mothers and newborns around childbirth, a specialization known as midwifery.

The education and training for a midwife concentrates extensively on the care of women throughout their lifespan; co ...

. They had three children, of whom the second, Ira Junius Johnson, was born 30 April 1893. After the death of Junius, Francis moved in with Ida and John.

Johnson grew up in Oakville, and the community accepted him as Black; he later asserted he was half White and half Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

. Despite a weak economy, he found work as a tanner at Oakville's largest factory. In 1916 he enlisted for service in the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. He was sent to the front in November as a member of the 9th Canadian Machine Gun Company during the Battle of Passchendaele

The Third Battle of Ypres (german: link=no, Dritte Flandernschlacht; french: link=no, Troisième Bataille des Flandres; nl, Derde Slag om Ieper), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele (), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by t ...

. He was one of about Black Canadians who were accepted into non-segregated sections of the Canadian military—officers were free to turn them down, and most did. Johnson participated in the Hundred Days Offensive

The Hundred Days Offensive (8 August to 11 November 1918) was a series of massive Allies of World War I, Allied offensives that ended the First World War. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens (1918), Battle of Amiens (8–12 August) on the Wester ...

that closed the war in 1918, during which he suffered a shrapnel wound that permanently injured his leg. He returned to Canada in May 1919 and was discharged that July.

Johnson returned to Oakville to live with his parents. He trained and found work as a motor mechanic, but was laid off after five years. Thereafter he did casual work for building contractors. By 1930, Johnson was working as a labourer and was living with a white girl, Isabella Jones; They intended to marry on 2 March, but Jones's mother Annie objected to the interracial pairing.

Oakville lies on Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York. The Canada–United States border sp ...

between Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

and Hamilton. It developed in the late 19th century as a resort town for affluent southwestern Ontarians. Oakville suffered unemployment after the Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

; in 1930 its population was about , overwhelming of British Isles-descent. Census figures are not available for the Black population, though the mayor of Oakville J. B. Moat told the press at the time the "coloured" population had recently decreased, and stood at "not more than forty with women and children".

Unlike in the United States with its Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

and Anti-miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws or miscegenation laws are laws that enforce racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalization, criminalizing interracial marriage and sometimes also sex between members of different R ...

, Canadian law did not bar those of different ethnicities from socializing or marrying; social pressures nonetheless made inter-ethnic associations difficult. The Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

had established itself in Canada, but had far less widespread membership and influence than it had in the United States. There were no anti-discrimination or anti-hate speech laws in effect in Canada as of 1930.

Incident

On the afternoon of 28 February 1930, Jones and Johnson went toNew Toronto

New Toronto is a neighbourhood and former municipality in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is located in the south-west area of Toronto, along Lake Ontario. The Town of New Toronto was established in 1890, and was designed and planned as an indust ...

to get a marriage license. About 22:00 that evening 75 members of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

from Hamilton gathered in Oakville. They marched through the town at night, wakening hundreds of residents and were dressed in white gowns and hoods. They placed a cross in the middle of the road and set it on fire. When the cross had burned out, they sought the police chief, David Kerr, to communicate their intentions; as the hour was late, he was not at the police station. The Klansmen then looked for Jones and Johnson, and tracked them to the home of Johnson's aunt Viola Sault; the couple were playing cards with members of Johnson's family.

The Klansmen kidnapped Jones and took her at a Salvation Army

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

location, where they watched over her from a car parked outside. Against his protests they placed Johnson in another car, surrounded by two guards, and burned a cross in front of the home. When the cross had finished burning, a representative of the Klan knocked on the door and informed Johnson's mother that if Johnson were "ever seen walking down the street with a white girl again the Klan would attend to him". They left Jones with Salvation Army Captain W. Broome and returned to Hamilton.

Reactions

The press took a favourable view of the incident and the conduct of the Klansmen. Police Chief Kerr noted that, when they removed their hoods, he recognized many of them as prominentHamiltonian

Hamiltonian may refer to:

* Hamiltonian mechanics, a function that represents the total energy of a system

* Hamiltonian (quantum mechanics), an operator corresponding to the total energy of that system

** Dyall Hamiltonian, a modified Hamiltonian ...

businessmen. The press quoted the mayor of Oakville J. B. Moat as having stated:

: "There was a strong feeling against the marriage which the young girl and the negro had planned. Personally I think the Ku Klux Klan acted quite properly in the matter. It will be an object lesson."

Of the few newspapers that objected to the Klansmen's actions, '' The Globe'' stated that if they "believe ... their objectives are worthy ... they will stand for open discussion in daylight; they should not call for nocturnal visits and disguising costumes". Nevertheless, ''The Globe'' stated the Klan's goal "may be commendable in itself and prove a benefit", and criticized only the methods it used. The Klan sent letters rebuttal to the newspaper, defending its actions "on the ground of racial purity", and asserted they acted on the request of Jones's mother. They said she had appealed to the authorities, who denied her assistance as her daughter was over the age of majority. The "frantic" mother then resorted to calling the Klan and told them her daughter "was being detained by a negro". After detaining her, the Klan insisted she had changed her mind about the marriage and promised "never again oassociate with a coloured man". The Klan took pains to disassociate itself from its counterpart in the United States by asserting its British character, and insisted it was not "opposed to the coloured people, provided they are true British subjects".

Members of Toronto's Black community moved to have the government deal with the Klan and its actions. Lawyers E. Lionel Cross and B. J. Spencer Pitt and Reverend H. Lawrence McNeil of the First Baptist Church of Toronto pressured Attorney General of Ontario

The Attorney General of Ontario is the chief legal adviser to His Majesty the King in Right of Ontario and, by extension, the Government of Ontario. The Attorney General is a senior member of the Executive Council of Ontario (the cabinet) and ...

William Herbert Price to launch a full investigation; Price had long had concerns over the Klan and had Kerr and Crown attorney

Crown attorneys or crown counsel (or, in Alberta and New Brunswick, crown prosecutors) are the prosecutors in the legal system of Canada.

Crown attorneys represent the Crown and act as prosecutor in proceedings under the Criminal Code and vario ...

William Inglis Dick to produce a full report. Toronto's Jewish community, Labour supporters, and the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom gave their support to the cause. Protesters gathered at the University Avenue First Baptist Church on 4 March.

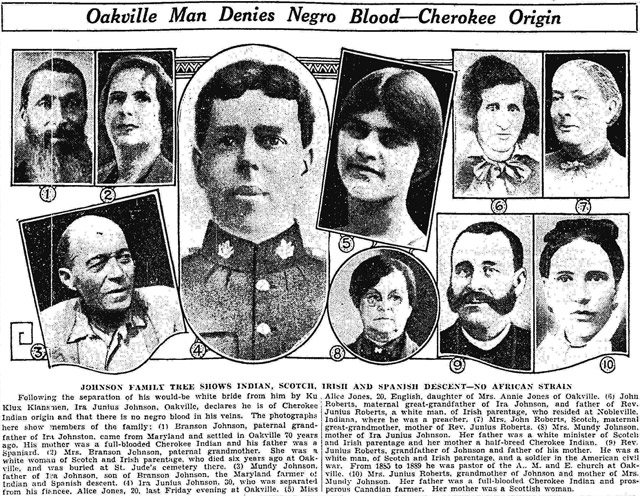

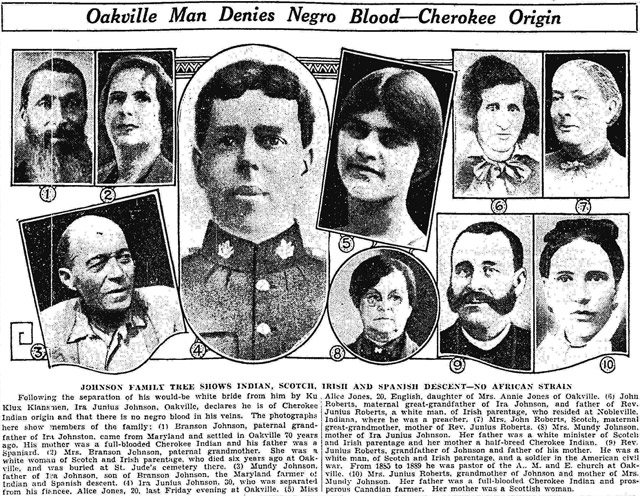

Johnson invited reporters from the ''Toronto Star

The ''Toronto Star'' is a Canadian English-language broadsheet daily newspaper. The newspaper is the country's largest daily newspaper by circulation. It is owned by Toronto Star Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary of Torstar Corporation and part ...

'' and told them he was not Black, but half White and half Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

. The newspaper printed his assertion on the front page of its 5 March edition under the title "Is of Indian Descent Ira Johnson Insists: Oakville man, Separated from His Sweetheart, Traces His Ancestry". The article opened:

: "Ira Junius Johnson, separated from his sweetheart, by Ku Klux Klansmen here last Friday, is of Indian descent and has not a drop of Negro blood in his veins, he told the ''Star'' yesterday at the home of his mother, who is a refined and intelligent woman."

Letters unfavourable to the Klan flooded into the newspapers; articles and editorials began to paint him in a favourable light and emphasized his war record. Moat retracted his comment and asserted he had been misquoted. Jones's mother insisted she did not oppose the marriage over Johnson's ethnicity, but because she thought he was too lazy to "get a job and make a man out of himself".

Trials

Under pressure from Toronto's Black community, the police pursued a case against the Klansmen. On 7 March they tracked down several members via license plates and the post-office box on a letter the Klan sent to ''The Globe''. Dick issued summonses to four men: William A. Phillips, a chiropractor; Ernest Taylor, a police interpreter and minister at the Hamilton Presbyterian Church; Harold C. Orme, a chiropractic assistant; and a William Mahony. They were charged with being "disguised by night", a burglary-related charge that carried up to a five-year sentence. Cross objected to such a light charge, arguing they were liable for "charges of abduction, trespess, violence", and numerous other offenses. At the trial, they pleaded "not guilty". The first witness, Police Chief Kerr, related that he had gone to investigate the cross-burning and shook hands with the defendants, who unmasked themselves and whom he said he knew "quite well"; he exhibited a white gown he had found at the site. He was questioned about Johnson's race and reputation and replied he was "coloured" and "unsavoury", though he had "never been in police court". Jones testified that she felt she had to get into the car with the men as "there were so many of them"; she could not recognize the accused as the men had been hooded. Phillips rejected the accusation that the Klan robes and hoods were a disguise and insisted they were "part of the traditional garb of the order" he belonged to. The defense attorney painted the Klan as having acted for a noble cause where the law could not reach, and stressed the lack of violence. Wearing hoods, he asserted, was "no more wrong than ... than it is for other lodgemen to wear regalia". Dick countered, "They were hooded for the purpose of taking that girl from this home, and not for lodge-room work." The court found Taylor and Orme not guilty, but Magistrate W. E. McIlveen decided on Phillips's guilt, saying he "fail dto see that there was any lawful excuse" for the Klan to have gone there hooded. The prosecution sought no term of imprisonment, but only a fine, saying "the penalty is immaterial. All that the Crown wants to show is that there is a machinery of Justice in Canada." Phillips was fined $50, and the defense appealed. Phillips threatened Jones outside the courthouse to return to her mother, and told her mother to call him again if she did not heed his warning. Thousands of members of the Klan protested the decision and threatened Black activists. Klan recruitment activity increased and Johnson's house burned down, over which Chief Kerr took no action. Five White judges of theOntario Court of Appeal

The Court of Appeal for Ontario (frequently referred to as the Ontario Court of Appeal or ONCA) is the appellate court for the province of Ontario, Canada. The seat of the court is Osgoode Hall in downtown Toronto, also the seat of the Law Societ ...

heard Phillips's appeal and Attorney General Price's counter-appeal on 16 April. The court did not look favourably upon the appeal and declared they would "not tolerate any group of men attempting to administer a self-made law". The court characterized the Klan's actions as "mob law" and found Phillips guilty; he served three months in prison.

Aftermath

After Phillips's release, the Klan filed a request to hold a parade; the Oakville city council rejected it. Though the Klan never disappeared, its power weakened throughout the rest of the 1930s in the face of the government's unwillingness to tolerate its actions. Laws dealing with hate crimes were passed gradually over the following decades throughout Canada. Johnson and Jones married on 24 March 1930. The White pastor who conducted the wedding responded to concerns about Klan interference by saying, "I was here before the Klan." They had two children, and Johnson took work as a gardener. He died in 1966. Generations later, writerLawrence Hill

Lawrence Hill (born January 24, 1957) is a Canadian novelist, essayist, and memoirist. He is known for his 2007 novel '' The Book of Negroes,'' inspired by the Black Loyalists given freedom and resettled in Nova Scotia by the British after the A ...

found that those in Johnson's community had always considered Johnson Black. He speculated that, while Johnson having aboriginal ancestry could not be ruled out, no evidence for it existed. Johnson may have hidden his Black ancestry due to the Klan's reputation for lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

Blacks in the US. For successfully turning citizens' feelings towards him by denying his Black heritage, Hill called him "Canada's first spin doctor

In public relations and politics, spin is a form of propaganda, achieved through knowingly

providing a biased interpretation of an event or campaigning to influence public opinion about some organization or public figure. While traditional publi ...

".

Notes

References

Works cited

* * * * * {{RefendExternal links

Johnson's attestation paper from World War I

1930 in Canada Anti-black racism in Canada Ku Klux Klan in Canada People from Oakville, Ontario Marriage in Canada 1930 crimes in Canada 1930 in Ontario