Irish Unionist Alliance on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Irish Unionist Alliance (IUA), also known as the Irish Unionist Party, Irish Unionists or simply the Unionists, was a unionist political party founded in

In the

In the

By 1914, the conflict of interest between the unionists in southern Ireland and those in Ulster was wracking the IUA.Pádraig Yeates, ''Dublin: A City in Turmoil: Dublin 1919 – 1921'' (Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 28 September 2012) It was known that the passage of a Home Rule Bill for Ireland was becoming increasingly likely, and as a result many Southern Unionists began to seek a political compromise which would see their interests protected. Many unionists in the south became strongly opposed to any plan to partition the island, as they knew that it would leave them isolated from the unionist-majority areas. Several prominent Southern Unionists, such as

By 1914, the conflict of interest between the unionists in southern Ireland and those in Ulster was wracking the IUA.Pádraig Yeates, ''Dublin: A City in Turmoil: Dublin 1919 – 1921'' (Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 28 September 2012) It was known that the passage of a Home Rule Bill for Ireland was becoming increasingly likely, and as a result many Southern Unionists began to seek a political compromise which would see their interests protected. Many unionists in the south became strongly opposed to any plan to partition the island, as they knew that it would leave them isolated from the unionist-majority areas. Several prominent Southern Unionists, such as

Note: Results from Ireland for the UK general elections contested by the Irish Unionist Alliance. These figures do not include MPs elected for the Liberal Unionists, who were officially a separate party. IUA MPs sat with the Liberal Unionists and Conservatives at Westminster, and were often simply called 'Conservatives' or 'Unionists'.

Note: Results from Ireland for the UK general elections contested by the Irish Unionist Alliance. These figures do not include MPs elected for the Liberal Unionists, who were officially a separate party. IUA MPs sat with the Liberal Unionists and Conservatives at Westminster, and were often simply called 'Conservatives' or 'Unionists'.

The leadership of southern unionism was dominated by wealthy, well-educated men who wanted to live in Ireland, felt British and Irish, and who had Irish roots. Many were members of the privileged

The leadership of southern unionism was dominated by wealthy, well-educated men who wanted to live in Ireland, felt British and Irish, and who had Irish roots. Many were members of the privileged

''The Home rule bill in committee, session, 1893''

from

"60 Years on: the “Southern Unionists”, the Crown and the Irish Republic"

essay by

Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

in 1891 from a merger of the Irish Conservative Party

The Irish Conservative Party, often called the Irish Tories, was one of the dominant Irish political parties in Ireland in the 19th century. It was affiliated with the Conservative Party in Great Britain. Throughout much of the century it and th ...

and the Irish Loyal and Patriotic Union

The Irish Loyal and Patriotic Union (ILPU) was a unionist political organisation in Ireland, established to oppose the Irish Home Rule movement.

The Irish Loyal and Patriotic Union was formed in Dublin in May 1885 by a small number of souther ...

to oppose plans for home rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in the British Isles that existed between 1801 and 1922, when it included all of Ireland. It was established by the Acts of Union 1800, which merged the Kingdom of Great B ...

. The party was led for much of its existence by Colonel Edward James Saunderson

Colonel Edward James Saunderson (1 October 183721 October 1906) was an Anglo-Irish landowner and prominent Irish unionist politician. He led the Irish Unionist Alliance between 1891 and 1906.

Early life

Saunderson was born at the family seat ...

and later by William St John Brodrick, Earl of Midleton. In total, eighty-six members of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

affiliated themselves with the Irish Unionist Alliance, although its broader membership was relatively small.

The party aligned itself closely with the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

and Liberal Unionists

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

to campaign to prevent the passage of a new Home Rule Bill

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

. Its MPs took the Conservative whip at Westminster, and its members were often described as 'Conservatives' or 'Conservative Unionists', even though much of its support came from former Liberal voters. Among its most prominent members were the Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

barrister, Sir Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, PC, Privy Council of Ireland, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Unionism in Ireland, Irish u ...

, and the founder of Ireland's cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-control ...

movement, Sir Horace Plunkett

Sir Horace Curzon Plunkett (24 October 1854 – 26 March 1932), was an Anglo-Irish agricultural reformer, pioneer of agricultural cooperatives, Unionist MP, supporter of Home Rule, Irish Senator and author.

Plunkett, a younger brother of Jo ...

. Its electoral strength was largely (although not exclusively) concentrated in east Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

and south Dublin.

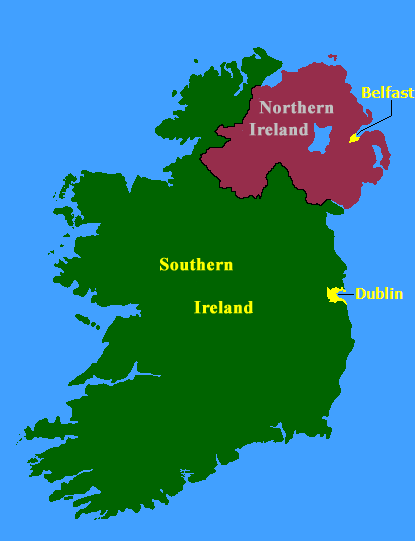

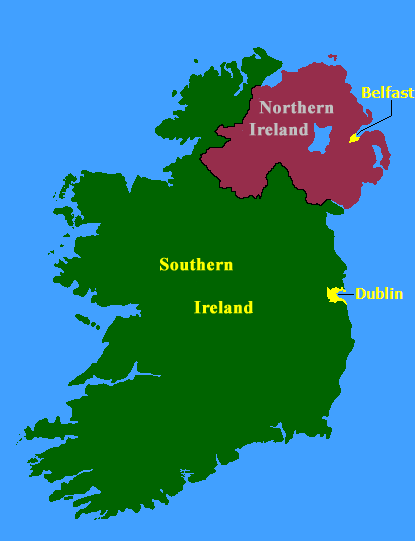

The IUA became wracked by internal disagreement during the early twentieth century, with the issue of the partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. I ...

proving to be particularly divisive. Many unionists outside Ulster became resigned to the political necessity of Home Rule, while unionists in Ulster established a separate organisation, the Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

(UUP). In 1919 the IUA finally split apart with the founding of the break-away Unionist Anti-Partition League

The Unionist Anti-Partition League (UAPL) was a unionist political organisation in Ireland which campaigned for a united Ireland within the United Kingdom. Led by St John Brodrick, 1st Earl of Midleton, it split from the Irish Unionist Alliance ...

, effectively signalling the death of institutional unionism in most of Ireland. The UUP continued to operate in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

, and would go on to dominate domestic politics there for much of the twentieth century.

History

Foundation

The Irish Unionist Alliance was founded in 1891 by the members of theIrish Loyal and Patriotic Union

The Irish Loyal and Patriotic Union (ILPU) was a unionist political organisation in Ireland, established to oppose the Irish Home Rule movement.

The Irish Loyal and Patriotic Union was formed in Dublin in May 1885 by a small number of souther ...

(ILPU), which it replaced. The ILPU had been established to prevent electoral competition between Liberals and Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

in the three southern provinces on a common platform of maintenance of the union.Graham Walker, ''A History of the Ulster Unionist Party: Protest, Pragmastism and Pessimism'' (Manchester University Press, 4 September 2004) The IUA united this movement with unionists in the northern province of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

, where unionist sentiment and support was strongest. As such, the new party sought to represent unionism on an all-Ireland

All-Ireland (sometimes All-Island) refers to all of Ireland, as opposed to the separate jurisdictions of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. "All-Ireland" is most frequently used to refer to sporting teams or events for the entire islan ...

basis. The party's founders hoped that this would coordinate the electoral and lobbying activities of unionist across Ireland. Prior to 1891, unionists had seen considerable electoral losses across southern Ireland at the hands of the pro-Home Rule Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish national ...

, founded a decade earlier.Travis L. Crosby, ''Joseph Chamberlain: A Most Radical Imperialist'' (I.B.Tauris, 30 March 2011), 102. It was deemed necessary for southern and northern supporters of the Union to more formally unite their efforts. At this stage, the majority of unionists in all parts of Ireland were opposed to the Irish Home Rule movement

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

, especially following the collapse of the Irish wing of the Liberal Party. The IUA's first leader was the Orangeman and former Conservative MP, Edward James Saunderson

Colonel Edward James Saunderson (1 October 183721 October 1906) was an Anglo-Irish landowner and prominent Irish unionist politician. He led the Irish Unionist Alliance between 1891 and 1906.

Early life

Saunderson was born at the family seat ...

.

1891–1914

In the

In the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, the party closely aligned itself with the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists. In the 1892 general election the party won 20.6% of the Irish vote and 21 seats. In 1893, the party achieved a major success when it joined the Conservatives to defeat the Home Rule Bill

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

. In the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

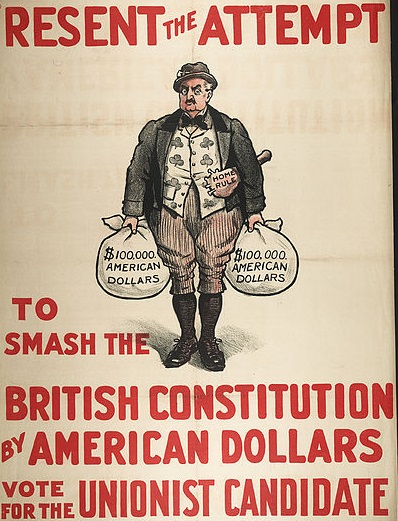

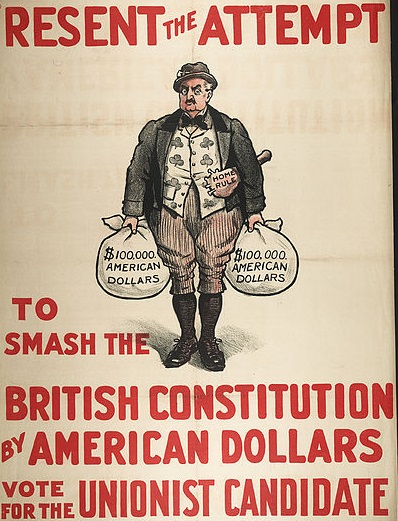

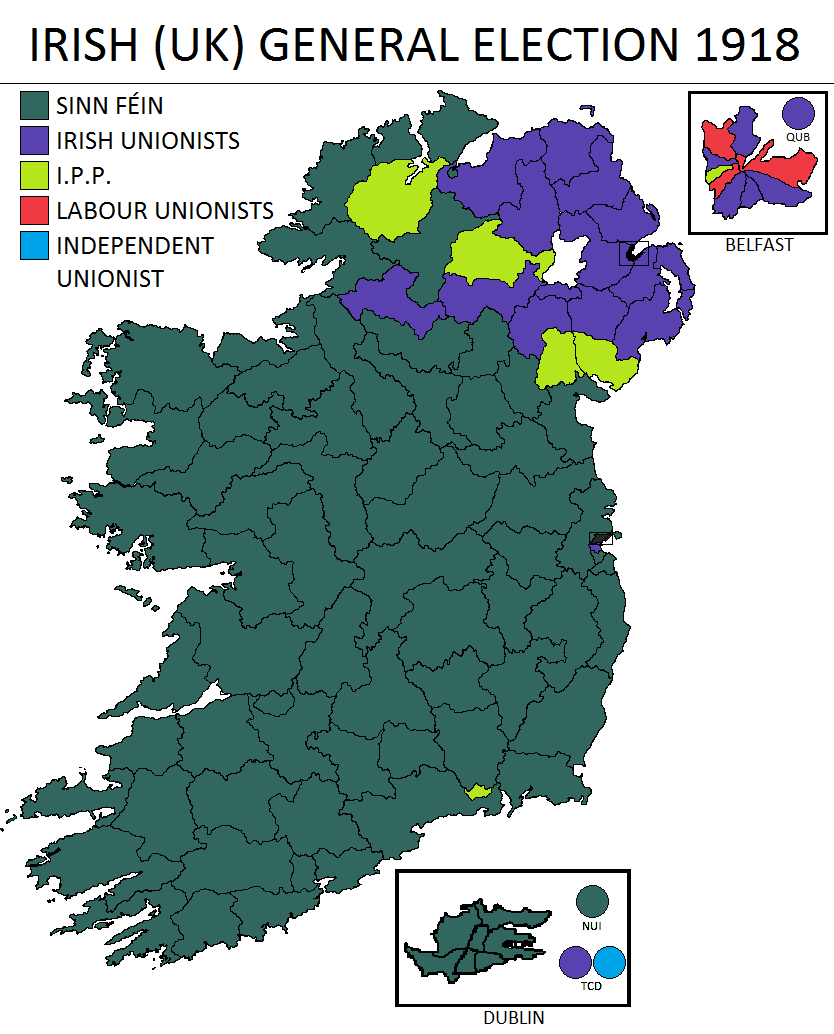

, eighty-six peers affiliated themselves with the Irish Unionist Alliance. This high level of support reflected the strong unionist sentiment within Ireland's landed class. Unionists in the Lords proved to be instrumental in defeating attempts by the Liberals to introduce Home Rule legislation. In the 1900 general election the party won 32.2% of the vote in Ireland.

Throughout the period, members of the IUA campaigned not only in Ireland, but also in Britain alongside the Conservative Party. This was especially the case in the two general elections of 1910. In December 1910

The following events occurred in December 1910:

December 1, 1910 (Thursday)

* Porfirio Diaz was inaugurated for his eighth term as President of Mexico."Record of Current Events", ''The American Monthly Review of Reviews'' (January 1911), pp ...

the IUA sent 278 workers to British constituencies to assist the Conservative candidates, distributing almost three million leaflets across England. It was during that this time that a large number of Conservative MPs married into Irish Southern Unionist families.

Despite early hopes among some unionists that the IUA would expand the unionist presence across Ireland, the party failed to make any major electoral gains in the six subsequent general elections. In the south of Ireland the IUA consistently won only the double seat representing the graduates of Dublin University

The University of Dublin ( ga, Ollscoil Átha Cliath), corporately designated the Chancellor, Doctors and Masters of the University of Dublin, is a university located in Dublin, Ireland. It is the degree-awarding body for Trinity College Dubl ...

, and a couple of the Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

seats would occasionally fall to them. The party also won a surprise victory in Galway City

Galway ( ; ga, Gaillimh, ) is a city in the West of Ireland, in the province of Connacht, which is the county town of County Galway. It lies on the River Corrib between Lough Corrib and Galway Bay, and is the sixth most populous city o ...

in 1900. In local elections, the party maintained a geographically broader representation, although failed to win many new voters. Unlike in Ulster, the anti-Home Rulers were a scattered minority.

In Ulster, the IUA built upon solid unionist electoral foundations and became the dominant political force in much of the province. In the north and east of Ulster, unionists consistently won seats, often unopposed. In three counties of Ulster which would later become part of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between th ...

, the unionists failed to come close to winning in Monaghan North, their strongest constituency of the eight in question, and never even contested West Donegal. Despite the prominence of many influential Southern Unionists in the party, Ulster remained the core of the IUA's support base. Ulster unionism was linked strongly to the former Conservatives, with their strong Orange Order links, rather than to the former Liberals, who had made some effort to encourage cross-denominational support for their unionist stance. The strength of the northern unionist wing played a vital role in the shift of power in the pro-union movement to Conservative and Orange elements. While the link between the Orange lodges and the new Unionist associations did introduce a populist, democratic element into unionist politics, it also served to reinforce the sectarian nature of unionism in the north. In 1905, this particular brand of unionism within the IUA led to the establishment of the Ulster Unionist Council

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

. Although Ulster Unionists were still within the broader framework of the Irish Unionist Alliance, the Ulster party began to develop its own distinct organisational structures and political goals. From 1907, the IUA's political activity was organised by the Joint Committee of the Unionist Associations of Ireland (JCUAI). This body sought to coordinate the IUA's election and lobbying activity, whilst recognising the distinct differences between the northern and southern parties.

The prominence of the Ulster Unionist Council quickly grew thanks to the strong unionist sentiment in Ulster. From 1910, it became the dominant force and focus of resistance in the Irish unionist community.Jeremy Smith, ''Britain and Ireland: From Home Rule to Independence'' (Routledge, 12 May 2014), 61. The JCUAI was effectively controlled by Ulstermen, while the IUA's leadership remained largely in the hands of Southern Unionists. This led to the unionist movement gradually becoming 'Ulsterised' from 1910, which marginalised many more moderate unionists in the south. Even so, in 1913, as the Third Home Rule Bill passed through Parliament, the Alliance appears to have become increasingly popular in the south and records show an increase in membership.

Division (1914–1922)

By 1914, the conflict of interest between the unionists in southern Ireland and those in Ulster was wracking the IUA.Pádraig Yeates, ''Dublin: A City in Turmoil: Dublin 1919 – 1921'' (Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 28 September 2012) It was known that the passage of a Home Rule Bill for Ireland was becoming increasingly likely, and as a result many Southern Unionists began to seek a political compromise which would see their interests protected. Many unionists in the south became strongly opposed to any plan to partition the island, as they knew that it would leave them isolated from the unionist-majority areas. Several prominent Southern Unionists, such as

By 1914, the conflict of interest between the unionists in southern Ireland and those in Ulster was wracking the IUA.Pádraig Yeates, ''Dublin: A City in Turmoil: Dublin 1919 – 1921'' (Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 28 September 2012) It was known that the passage of a Home Rule Bill for Ireland was becoming increasingly likely, and as a result many Southern Unionists began to seek a political compromise which would see their interests protected. Many unionists in the south became strongly opposed to any plan to partition the island, as they knew that it would leave them isolated from the unionist-majority areas. Several prominent Southern Unionists, such as Sir Horace Plunkett

Sir Horace Curzon Plunkett (24 October 1854 – 26 March 1932), was an Anglo-Irish agricultural reformer, pioneer of agricultural cooperatives, Unionist MP, supporter of Home Rule, Irish Senator and author.

Plunkett, a younger brother of Jo ...

and Lord Monteagle, became convinced that a degree of home rule was going to be necessary if Ireland was to avoid partition and remain in the Union. Others, such as the anti-partition party leader William St John Brodrick, Earl of Midleton, resented the growing dominance of Ulstermen in the party.Desmond Keenan, ''Ireland Within The Union 1800–1921'' (Xlibris Corporation), 228. He and his supporters feared that the Ulster wing of the party (now more formally organised as the Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

) would abandon the south in order to gain a favourable settlement for the north from the British government. In October 1913, the vice-chairman of the IUA, G. F. Stewart

George Francis Stewart PC (1 November 1851 – 12 August 1928) was an Irish land agent and public servant.

Stewart was born at Gortleitragh House, County Dublin, the son of James Robert Stewart, a wealthy land agent, and Martha Warren, da ...

, had written to its leader Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, PC, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician, barrister and judge, who served as the Attorney General and Solicito ...

to complain that southern concerns were being ignored.Alan O'Day, ''Reactions to Irish Nationalism, 1865–1914'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 1 July 1987), 378. Several large unionist demonstrations took place in Dublin in early 1914, in which protesters complained as much about the Ulster Unionists as the Irish nationalists. Despite these internal difficulties, between September 1911 and July 1914 the Joint Committee of the Unionist Associations of Ireland continued its campaign across the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

. In this period, the IUA distributed an estimated six million pamphlets and booklets throughout Britain, canvassed 1.5 million voters and arranged 8,800 meetings.

The internal divisions simmered during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Southern Unionist members sided with Irish Nationalists

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

against the Ulster Unionists during the 1917–18 Irish Convention

The Irish Convention was an assembly which sat in Dublin, Ireland from July 1917 until March 1918 to address the ''Irish question'' and other constitutional problems relating to an early enactment of self-government for Ireland, to debate its wid ...

in an attempt to bring about an understanding on the implementation of the suspended Home Rule Act 1914

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5 c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-governm ...

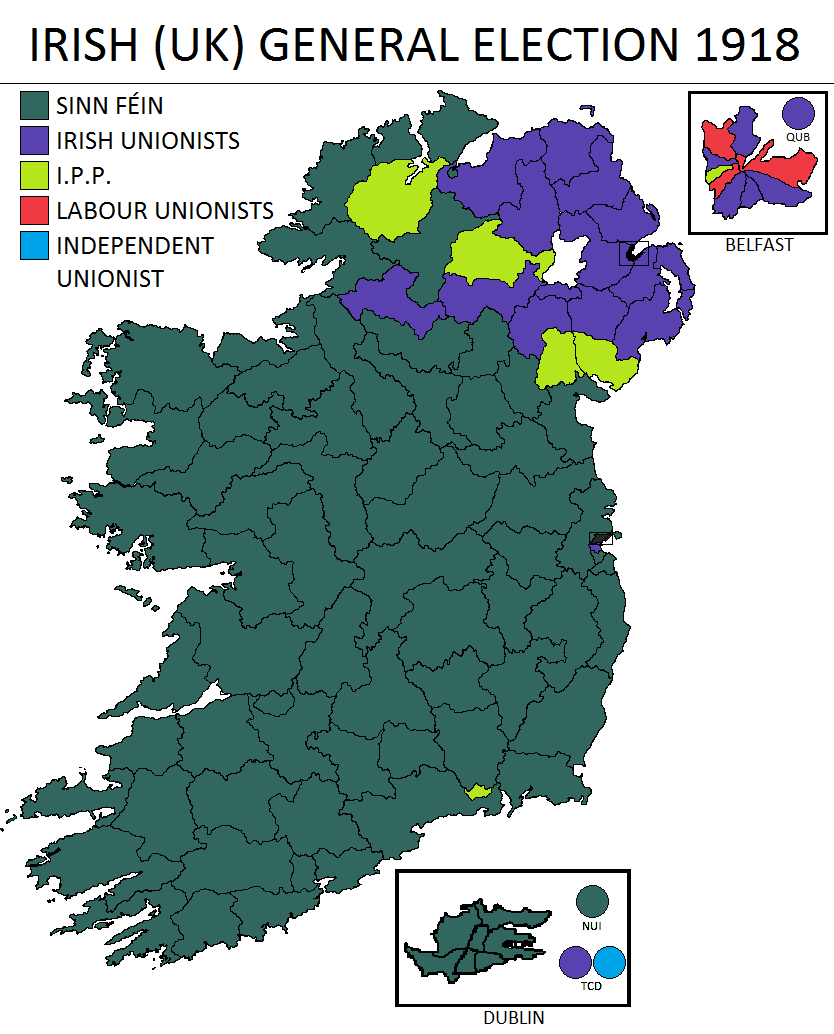

. The Alliance's official opposition to partition led to it being marginalised in the 1918 general election, which showed the rising influence of the republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

party on the one hand and the strength of Ulster Unionist Council

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

on the other. Despite this, the Alliance won its largest number of seats, with the IUA candidate managing to win a surprise victory in Rathmines

Rathmines () is an affluent inner suburb on the Southside of Dublin in Ireland. It lies three kilometres south of the city centre. It begins at the southern side of the Grand Canal and stretches along the Rathmines Road as far as Rathgar to t ...

. Against the backdrop of the subsequent Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

unionists began to openly disagree. At a meeting of the party on Molesworth Street, Dublin on 24 January 1919, Lord Midleton proposed a motion to the party which would have denied Ulster Unionists a say on government proposals affecting the south of Ireland. The motion was defeated, with a majority of both southern and northern unionists rejecting the plan. Ulster Unionists believed that the motion would have the effect of dividing the unionist cause. The party split anyway, with Lord Midleton and senior southern leaders forming the break-away Unionist Anti-Partition League

The Unionist Anti-Partition League (UAPL) was a unionist political organisation in Ireland which campaigned for a united Ireland within the United Kingdom. Led by St John Brodrick, 1st Earl of Midleton, it split from the Irish Unionist Alliance ...

that same day. Many ordinary members of the southern IUA (Protestant farmers, shopkeepers and clergymen) initially stayed with remaining rump of the IUA in the south, led by Arthur Maxwell, 11th Baron Farnham.

Although the IUA hoped to play a part in the Parliament of Southern Ireland

The Parliament of Southern Ireland was a Home Rule legislature established by the British Government during the Irish War of Independence under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. It was designed to legislate for Southern Ireland,"Order in Counc ...

envisaged under the 1920 Home Rule Act, the parliament never functioned. The ''Irish Times'', said to be the "voice of Southern Unionists", realised that the 1920 Act would not work and argued from late 1920 for "Dominion Home Rule", the compromise that was eventually agreed upon in the 1921–22 Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

. Under the Treaty, Northern Ireland became a part of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between th ...

from its creation on 6 December 1922; the Northern Irish parliament voted to leave the Free State two days later.

Irish Free State

The split effectively ended the realistic electoral chances of the Irish Unionist Alliance in southern Ireland. The results of the1920 Irish local elections

Nineteen or 19 may refer to:

* 19 (number), the natural number following 18 and preceding 20

* one of the years 19 BC, AD 19, 1919, 2019

Films

* ''19'' (film), a 2001 Japanese film

* ''Nineteen'' (film), a 1987 science fiction film

Music ...

show that unionist support was strongest in urban areas. As the partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. I ...

became more likely, Southern Unionists formed numerous political movements in an attempt to find a solution to the "Irish Question". Among these were Irish Dominion League

The Irish Dominion League was an Irish political party and movement in Britain and Ireland which advocated Dominion status for Ireland within the British Empire, and opposed partition of Ireland into separate southern and northern jurisdictions ...

and the Irish Centre Party. As such, the southern rump of the IUA became increasingly fractured and in 1922 it lost its reason to exist with the establishment of the Irish Free State. Leading unionist figures, such as the Earl of Midleton, Lord Dunraven, James Campbell James Campbell may refer to:

Academics

* James Archibald Campbell (1862–1934), founder of Campbell University in North Carolina

* James Marshall Campbell (1895–1977), dean of the college of arts and sciences at the Catholic University of Americ ...

and Horace Plunkett

Sir Horace Curzon Plunkett (24 October 1854 – 26 March 1932), was an Anglo-Irish agricultural reformer, pioneer of agricultural cooperatives, Unionist MP, supporter of Home Rule, Irish Senator and author.

Plunkett, a younger brother of Jo ...

were appointed in December 1922 by W. T. Cosgrave

William Thomas Cosgrave (5 June 1880 – 16 November 1965) was an Irish Fine Gael politician who served as the president of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State from 1922 to 1932, leader of the Opposition in both the Free State and Ire ...

to the Free State's first Senate. Amongst others, Horace Plunkett's home in County Dublin

"Action to match our speech"

, image_map = Island_of_Ireland_location_map_Dublin.svg

, map_alt = map showing County Dublin as a small area of darker green on the east coast within the lighter green background of ...

was then burnt down during the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War ( ga, Cogadh Cathartha na hÉireann; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United ...

(1922–23) because of his involvement in the Irish Senate. The IUA helped form the Southern Irish Loyalist Relief Association to assist war refugees and claim compensation for damage to property. From 1921 IUA voters began to support the mainstream Cumann na nGaedheal

Cumann na nGaedheal (; "Society of the Gaels") was a political party in the Irish Free State, which formed the government from 1923 to 1932. In 1933 it merged with smaller groups to form the Fine Gael party.

Origins

In 1922 the pro-Treaty G ...

party.

In the 1923 election three formerly loyalist businessmen were elected as the Business and Professional Group

The Business and Professional Group (also known as the Businessmen's Party) was a minor political party in the Irish Free State that existed between 1922 and 1923. It largely comprised ex- Unionist businessmen and professionals.Barberis, McHugh a ...

. From 1921 to 1991 the proportion of Southern Irish Protestants declined from 10% to 3% of the population; these had provided the bulk of the IUA's support base. Unionists continued to have a majority on Rathmines Council until 1929, when the IUA's successors lost their last elected representatives in the Irish Free State.

Northern Ireland

InNorthern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

unionists of the Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

(previously known as the Ulster Unionist Council) continued to dominate domestic politics. The party would hold its powerful position in the unionist community for much of the rest of the twentieth century, until the rise of the Democratic Unionist Party

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a unionist, loyalist, and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who led the party for the next 37 years. Currently led by J ...

in the late 1980s.

General election results

Note: Results from Ireland for the UK general elections contested by the Irish Unionist Alliance. These figures do not include MPs elected for the Liberal Unionists, who were officially a separate party. IUA MPs sat with the Liberal Unionists and Conservatives at Westminster, and were often simply called 'Conservatives' or 'Unionists'.

Note: Results from Ireland for the UK general elections contested by the Irish Unionist Alliance. These figures do not include MPs elected for the Liberal Unionists, who were officially a separate party. IUA MPs sat with the Liberal Unionists and Conservatives at Westminster, and were often simply called 'Conservatives' or 'Unionists'.

Support base

Southern Unionists

The leadership of southern unionism was dominated by wealthy, well-educated men who wanted to live in Ireland, felt British and Irish, and who had Irish roots. Many were members of the privileged

The leadership of southern unionism was dominated by wealthy, well-educated men who wanted to live in Ireland, felt British and Irish, and who had Irish roots. Many were members of the privileged Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

class, who valued their cultural affiliations with the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, and had close personal connections to the aristocracy in Britain. This led to their pejorative description by some opponents as "West Brit

West Brit, an abbreviation of West Briton, is a derogatory term for an Irish person who is perceived as Anglophilic in matters of culture or politics. West Britain is a description of Ireland emphasising it as under British influence.

History

...

s". They were generally members of the Anglican Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

, although there were several notable Catholic unionists, such as The 5th Earl of Kenmare, and Sir Antony MacDonnell. Many of the IUA's leading figures were associated with the Kildare Street Club

The Kildare Street Club is a historical member's club in Dublin, Ireland, at the heart of the Anglo-Irish Protestant Ascendancy.

The Club remained in Kildare Street between 1782 and 1977, when it merged with the Dublin University Club to become ...

, a gentleman's club in Dublin. The electoral support base of the IUA in southern Ireland was largely drawn from its Protestant population, many of whom were farmers, small business owners or Church of Ireland clergymen. In 1913, the IUA had a southern core of 683 members, with approximately 300,000 supporters spread across the three southern provinces.Alan O'Day, ''Reactions to Irish Nationalism, 1865–1914'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 1 July 1987), 370–371. In March 1919 Sir Maurice Dockrell told the House of Commons that the supporting population was "about 350,000". The IUA never achieved "mass party" status in the south. Its local branches varied in strength, and generally followed geographic patterns of Protestant population density. As a result, the IUA's support base was severely limited to certain sections of the population, described as usually being "Protestant, anglicised, propertied and aristocratic".

Although their numbers were small, a considerable amount of industry in Southern Ireland had been developed indigenously by Southern Unionist supporters. These included Jacob's Biscuits, Bewley's

Bewley's is an Irish hot beverage company, located in Dublin and founded in 1840, which operates internationally. Its primary business operations are the production of tea and coffee, and the operations of cafés. Bewley's has operations in Ire ...

, Beamish and Crawford

Beamish and Crawford was a brewery and brewing company based in Cork, Ireland, established in 1792 by William Beamish and William Crawford on the site of an existing porter brewery. In the early 1800s, it was the largest brewery in Ireland.

Be ...

, Brown Thomas

Brown Thomas & Company Limited is a chain of five Irish department stores, located in Dublin, Cork, Galway, Limerick and Dundrum Town Centre. Part of the Selfridges Group, Brown Thomas is an upmarket chain, akin to Britain's Selfridges stores ...

, Cantrell & Cochrane, Denny's Sausages, Findlaters, Jameson's Whiskey, W.P. & R. Odlum, Cleeve's, R&H Hall

R&H Hall plc is Ireland's biggest importer and supplier of animal feed ingredients for feed manufacturing through its trading, purchasing, shipping and storage capability.

Company history

IAWS purchased two small feed trading businesses between 1 ...

, Dockrell's, Arnott's, Elverys, Goulding Chemicals {{More citations needed, date=October 2022

Goulding Chemicals Ltd is a wholly owned subsidiary of Origin Enterprises plc. The company supplies a wide range of Agricultural Fertilisers and Industrial Chemicals to the Irish market.

History

The c ...

, Smithwick's

Smithwick's () is an Irish red ale-style beer.

Smithwick's brewery was founded in Kilkenny in 1710 by John Smithwick and run by the Smithwick family of Kilkenny until 1965 when it was acquired by Guinness, now part of Diageo. The Kilkenny br ...

, ''The Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is considered a newspaper ...

'' and the Guinness brewery

St. James's Gate Brewery is a brewery founded in 1759 in Dublin, Ireland, by Arthur Guinness. The company is now a part of Diageo, a company formed from the merger of Guinness and Grand Metropolitan in 1997. The main product of the brewery is ...

, then southern Ireland's largest company. They controlled financial entities such as the Bank of Ireland

Bank of Ireland Group plc ( ga, Banc na hÉireann) is a commercial bank operation in Ireland and one of the traditional Big Four Irish banks. Historically the premier banking organisation in Ireland, the Bank occupies a unique position in Iris ...

and Goodbody Stockbrokers

Goodbody Stockbrokers is Ireland's longest established stockbroking firm with roots dating back to 1877. As well as being one of the leading institutional brokers, it is one of the largest private client firms in Ireland. It is a member firm of ...

. They were concerned that a new home rule state might create new taxes between them and their markets in Britain and the Empire, that would add to their costs and probably reduce sales and therefore employment.

Many Southern Unionist landowners had inherited large estates. From 1903, many of these were persuaded to sell land to their tenant farmers under the Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903

The Land Acts (officially Land Law (Ireland) Acts) were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by ...

. As a group, Southern Unionist landowners were richer than their fellow Irishmen by about £90 million by 1914, which would either stay in the Irish economy, given a favourable political arrangement, or leave if the outcome appeared too uncertain or too radical. This temporarily gave them a voice far beyond their number in the Irish electorate. Some of the more progressive supporters of the IUA attempted to introduce a moderate form of devolution through the Irish Reform Association

The Irish Reform Association (1904–1905) was an attempt to introduce limited devolved self-government to Ireland by a group of reform oriented Irish unionist land owners who proposed to initially adopt something less than full Home Rule. It ...

. Many Southern Unionists were members of the landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the ''gentry'', is a largely historical British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. While distinct from, and socially below, the British peerage, th ...

, and these were prominent in horse breeding

Horse breeding is reproduction in horses, and particularly the human-directed process of selective breeding of animals, particularly purebred horses of a given breed. Planned matings can be used to produce specifically desired characteristics in ...

and racing

In sport, racing is a competition of speed, in which competitors try to complete a given task in the shortest amount of time. Typically this involves traversing some distance, but it can be any other task involving speed to reach a specific goa ...

, and as British Army officers

This is a list of senior officers of the British Army. See also Commander in Chief of the Forces, Chief of the General Staff, and Chief of the Imperial General Staff.

Captains-General of the British Army, 1707–1809

See article on Captain gene ...

.

Southern Unionists are regarded as having been considerably less confrontational than their Ulster neighbours.Alan O'Day, ''Reactions to Irish Nationalism, 1865–1914'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 1 July 1987), 369. They were always in the minority in southern Ireland, and many had close personal connections with figures in nationalist politics. As a group, they never threatened or organised violence in order to resist Home Rule or partition, and were generally placid in their politics. Lord Midleton described Southern Unionists as "lacking political insight and cohesion" and "restricting themselves to the easy task of attending meetings in Dublin". In discussing problems of civic morality in 2011 in the Republic of Ireland, former Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government, or prime minister, of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The office is appointed by the president of Ireland upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legisl ...

Garret FitzGerald

Garret Desmond FitzGerald (9 February 192619 May 2011) was an Irish Fine Gael politician, economist and barrister who served twice as Taoiseach, serving from 1981 to 1982 and 1982 to 1987. He served as Leader of Fine Gael from 1977 to 1987, and ...

remarked that before 1922: "In Ireland a strong civic sense did exist – but mainly amongst Protestants and especially Anglicans"."Ireland's lack of civic morality grounded in our history", Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is considered a newspaper ...

9 April 2011, p.14

Ulster Unionists

Ulster Unionists were largely ProtestantPresbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

s, rather than Anglicans. The Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

support base was considerably more working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

than in the south. Although often led by aristocrats, the IUA attracted high levels of support in some of the poorer areas of Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

. Many Ulster Unionists were also drawn from the province's prosperous middle class, who had benefited greatly from heavy industrialisation in the region. As such, many in Northern Ireland supported unionism due to the industrial growth of Belfast after 1850, which depended on the economic integrity of the Union. The Protestant religious composition and concentration, motivation and ethos of the Ulster Unionists made its wing of the IUA distinct from unionists in the south, and a fear of ''Rome Rule

"Rome Rule" was a term used by Irish unionists to describe their belief that with the passage of a Home Rule Bill, the Roman Catholic Church would gain political power over their interests in Ireland. The slogan was popularised by the Radical MP ...

'' (the worry about a Catholic-controlled Irish parliament) dominated the political discourse. These factors made Ulster Unionists noticeably more confrontational and violent in their political rhetoric and action. In the tense period between the Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5 c. 13) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Parlia ...

and the Home Rule Act 1914

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5 c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-governm ...

, the Ulster unionists created their own paramilitary group, the "Ulster Volunteers

The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the ...

", raising the spectre of civil war. The volunteer force was created by the then-leader of the Irish Unionist Alliance, Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, PC, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician, barrister and judge, who served as the Attorney General and Solicito ...

. This tradition of resistance to Irish nationalism would later manifest itself in groups such as the Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and Timeline of Ulster Defence Association act ...

and the Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former British Army soldier from Northern Ireland. The group undertook an armed campaig ...

during The Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

.

Leadership

The Irish Unionist Alliance had no formal method of electing and deposing of its leadership, and leaders of the IUA were more informally 'acknowledged' by other prominent figures. The party's first leader wasEdward James Saunderson

Colonel Edward James Saunderson (1 October 183721 October 1906) was an Anglo-Irish landowner and prominent Irish unionist politician. He led the Irish Unionist Alliance between 1891 and 1906.

Early life

Saunderson was born at the family seat ...

, a former Conservative Member of Parliament, who was most active in attempting to create an all-Ireland unionist movement. Towards the end of the party's existence, leadership became fractured between the northern and southern unionist movements within the alliance.

Leaders

* The 1st Earl of Midleton (1910–1919), as leader of the Southern Unionists * The 11th Baron Farnham (1919–1922), as leader of the Southern UnionistsNotes

References

* Barberis, Peter, John McHugh and Mike Tyldesley, 2005. Encyclopedia of British and Irish Political Organisations. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ,External links

''The Home rule bill in committee, session, 1893''

from

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

"60 Years on: the “Southern Unionists”, the Crown and the Irish Republic"

essay by

Mary Kenny

Mary Kenny (born 4 April 1944) is an Irish journalist, broadcaster and playwright. A founding member of the Irish Women's Liberation Movement, she was one of the country's first and foremost feminists, often contributes columns to the ''Irish I ...

in ''Studies'', Dublin 2009

{{Ulster Unionist Party

Conservative parties in Ireland

Unionist

Unionism in Ireland

Irish Unionist Party politicians

Defunct political parties in Ireland

Organisations associated with the Conservative Party (UK)

Conservative parties in the United Kingdom

Right-wing parties in the United Kingdom

History of the Conservative Party (UK)

1891 establishments in Ireland

Political parties established in 1891

1922 disestablishments in Ireland

Political parties disestablished in 1922