Irish-Canadians on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

ga, Gael-Cheanadaigh , image = Irish_Canadian_population_by_province.svg , image_caption =

13.4% of the Canadian population (2016) , popplace = , region1 = Provinces: , region2 =

Irish established communities in both urban and rural Quebec. Irish immigrants arrived in large numbers in

Irish established communities in both urban and rural Quebec. Irish immigrants arrived in large numbers in  The Irish would also settle in large numbers in Quebec City and establish communities in rural Quebec, particularly in

The Irish would also settle in large numbers in Quebec City and establish communities in rural Quebec, particularly in

With the downturn of Ireland's economy in 2010, many Irish people came to Canada looking for work, or to pre-arranged employment. There are many communities in Ontario that are named after places and last names of Ireland, including Ballinafad, Ballyduff, Ballymote,

Saint John has often been called "Canada's Irish City". In the years between 1815, when vast industrial changes began to disrupt the old life-styles in Europe, and Canadian Confederation in 1867, when immigration of that era passed its peak, more than 150,000 immigrants from Ireland arrived to Saint John. Those who came in the earlier period were largely tradesmen, and many stayed in Saint John, becoming the backbone of its builders. But when the Great Famine raged between 1845 and 1852, huge waves of Famine refugees arrived. It is estimated that between 1845 and 1847, some 30,000 arrived, more people than were living in the city at the time. In 1847, dubbed "Black 47", one of the worst years of the Famine, some 16,000 immigrants, most of them from Ireland, arrived at Partridge Island, the immigration and quarantine station at the mouth of Saint John Harbour.

After the partitioning of the British colony of Nova Scotia in 1784 New Brunswick was originally named New Ireland with the capital to be in Saint John.

By 1850, the Irish Catholic community constituted Saint John's largest ethnic group. In the census of 1851, over half the heads of households in the city registered themselves as natives of Ireland. By 1871, 55 per cent of Saint John's residents were Irish natives or children of Irish-born fathers. However, the city was split with tensions between Irish Catholics and Unionist Protestants. From the 1840s onward, Sectarian riots were rampant in the city with many poor, Irish-speaking immigrants clustered at York Point.

In 1967, at Reed's Point at the foot of Prince William Street, St. Patrick's Square was created to honour citizens of Irish heritage. The square overlooks Partridge Island, and a replica of the island's Celtic Cross stands in the square. Then in 1997 the park was refurbished by the city with a memorial marked by the city's St. Patrick's Society and Famine 150 which was unveiled by Hon. Mary Robinson, president of Ireland. The St. Patrick's Society of Saint John, founded in 1819, is still active today.

The

Saint John has often been called "Canada's Irish City". In the years between 1815, when vast industrial changes began to disrupt the old life-styles in Europe, and Canadian Confederation in 1867, when immigration of that era passed its peak, more than 150,000 immigrants from Ireland arrived to Saint John. Those who came in the earlier period were largely tradesmen, and many stayed in Saint John, becoming the backbone of its builders. But when the Great Famine raged between 1845 and 1852, huge waves of Famine refugees arrived. It is estimated that between 1845 and 1847, some 30,000 arrived, more people than were living in the city at the time. In 1847, dubbed "Black 47", one of the worst years of the Famine, some 16,000 immigrants, most of them from Ireland, arrived at Partridge Island, the immigration and quarantine station at the mouth of Saint John Harbour.

After the partitioning of the British colony of Nova Scotia in 1784 New Brunswick was originally named New Ireland with the capital to be in Saint John.

By 1850, the Irish Catholic community constituted Saint John's largest ethnic group. In the census of 1851, over half the heads of households in the city registered themselves as natives of Ireland. By 1871, 55 per cent of Saint John's residents were Irish natives or children of Irish-born fathers. However, the city was split with tensions between Irish Catholics and Unionist Protestants. From the 1840s onward, Sectarian riots were rampant in the city with many poor, Irish-speaking immigrants clustered at York Point.

In 1967, at Reed's Point at the foot of Prince William Street, St. Patrick's Square was created to honour citizens of Irish heritage. The square overlooks Partridge Island, and a replica of the island's Celtic Cross stands in the square. Then in 1997 the park was refurbished by the city with a memorial marked by the city's St. Patrick's Society and Famine 150 which was unveiled by Hon. Mary Robinson, president of Ireland. The St. Patrick's Society of Saint John, founded in 1819, is still active today.

The

The large Irish Catholic element in Newfoundland in the 19th century played a major role in Newfoundland history, and developed a strong local culture of their own. They were in repeated political conflict—sometimes violent—with the Protestant Scots-Irish "Orange" element.

In 1806, The

The large Irish Catholic element in Newfoundland in the 19th century played a major role in Newfoundland history, and developed a strong local culture of their own. They were in repeated political conflict—sometimes violent—with the Protestant Scots-Irish "Orange" element.

In 1806, The

ga, Gael-Cheanadaigh , image = Irish_Canadian_population_by_province.svg , image_caption =

13.4% of the Canadian population (2016) , popplace = , region1 = Provinces: , region2 =

Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

, pop2 = 2,095,460

, region3 = British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

, pop3 = 675,135

, region4 = Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

, pop4 = 596,750

, region5 = Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

, pop5 = 446,215

, region6 = Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, pop6 = 201,655

, region7 = New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

, pop7 = 135,835

, region8 = Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, pop8 = 106,225

, langs = English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

Irish (historically)

, rels =

, related = Irish, Ulster-Scots Ulster Scots, may refer to:

* Ulster Scots people

The Ulster Scots ( Ulster-Scots: ''Ulstèr-Scotch''; ga, Albanaigh Ultach), also called Ulster Scots people (''Ulstèr-Scotch fowk'') or (in North America) Scotch-Irish (''Scotch-Airisch'') ...

, English Canadians, Scottish Canadians, Welsh Canadians, Irish Americans, Scotch-Irish Canadians

Irish Canadians ( ga, Gael-Cheanadaigh) are Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

citizens who have full or partial Irish heritage including descendants who trace their ancestry to immigrants who originated in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

. 1.2 million Irish immigrants arrived from 1825 to 1970, and at least half of those in the period from 1831 to 1850. By 1867, they were the second largest ethnic group (after the French), and comprised 24% of Canada's population. The 1931 national census counted 1,230,000 Canadians of Irish descent, half of whom lived in Ontario. About one-third were Catholic in 1931 and two-thirds Protestant.

The Irish immigrants were majority Protestant before the Irish famine years of the late 1840s, when far more Catholics than Protestants arrived. Even larger numbers of Catholics headed to the United States; others went to Great Britain and Australia.

As of the 2016 Canada Census

The 2016 Canadian census was an enumeration of Canadian residents, which counted a population of 35,151,728, a change from its 2011 population of 33,476,688. The census, conducted by Statistics Canada, was Canada's seventh quinquennial census. ...

, 4,627,000 Canadians, or 13.43% of the population, claim full or partial Irish ancestry.

Irish Canadians comprise a subgroup of British Canadians which is a further subgroup of European Canadians

European Canadians, or Euro-Canadians, are Canadians who were either born in or can trace their ancestry to the continent of Europe. They form the largest panethnic group within Canada.

In the 2021 Canadian census, 19,062,115 Canadians self-i ...

.

History

Early arrival

The first recorded Irish presence in the area of present-day Canada dates from 1536, when Irish fishermen fromCork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

traveled to Newfoundland.

After the permanent settlement in Newfoundland by Irish in the late 18th and early 19th century, overwhelmingly from Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

, increased immigration of the Irish elsewhere in Canada began in the decades following the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

and formed a significant part of The Great Migration of Canada

The Great Migration of Canada (also known as the Great Migration from Britain or the second wave of immigration to Canada) was a period of high immigration to Canada from 1815 to 1850, which involved over 800,000 immigrants, mainly of British diasp ...

. Between 1825 and 1845, 60% of all immigrants to Canada were Irish; in 1831 alone, some 34,000 arrived in Montreal.

Between 1830 and 1850, 624,000 Irish arrived; in contextual terms, at the end of this period, the population of the provinces of Canada was 2.4 million. Besides Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the ...

(Ontario), Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec an ...

(Quebec), the Maritime colonies of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen Provinces and territories of Canada, provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has seve ...

and New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

, especially Saint John, were arrival points. Not all remained; many out-migrated to the United States or to Western Canada in the decades that followed. Few returned to Ireland.

During the Great Famine of Ireland (1845–52), Canada received the most destitute Irish Catholics, who left Ireland in grave circumstances. Land estate owners in Ireland would either evict landholder tenants to board on returning empty lumber ships, or in some cases pay their fares. Others left on ships from the overcrowded docks in Liverpool and Cork.

Most of the Irish immigrants who came to Canada and the United States in the nineteenth century and before were Irish speakers, with many knowing no other language on arrival.

Settlement

The great majority of Irish Catholics arrived in Grosse Isle, an island inQuebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

in the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

, which housed the immigration reception station. Thousands died or arrived sick and were treated in the hospital (equipped for less than one hundred patients) in the summer of 1847; in fact, many ships that reached Grosse-Île had lost the bulk of their passengers and crew, and much more died in quarantine

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been ...

on or near the island. From Grosse-Île, most survivors were sent to Quebec City and Montreal, where the existing Irish community grew. The orphaned children were adopted into Quebec families and accordingly became Québécois, both linguistically and culturally. At the same time, ships with the starving also docked at Partridge Island, New Brunswick in similarly desperate circumstances.

A large number of the families that survived continued on to settle in Canada West (now Ontario) and provided a cheap labor pool and colonization of land in a rapidly expanding economy in the decades after their arrival.

In comparison with the Irish who went to the United States or Britain, many Irish arrivals in Canada settled in rural areas, in addition to the cities.

The Catholic Irish and Protestant (Orange) Irish were often in conflict from the 1840s. In Ontario, the Irish fought with the French for control of the Catholic Church, with the Irish successful. In that instance, the Irish sided with the Protestants to oppose the demand for French-language Catholic schools.

Thomas D'Arcy McGee

Thomas D'Arcy McGee (13 April 18257 April 1868) was an Irish-Canadian politician, Catholic spokesman, journalist, poet, and a Father of Canadian Confederation. The young McGee was an Irish Catholic who opposed British rule in Ireland, and w ...

, an Irish-Montreal journalist, became a Father of Confederation

The Fathers of Confederation are the 36 people who attended at least one of the Charlottetown Conference of 1864 (23 attendees), the Quebec Conference of 1864 (33 attendees), and the London Conference of 1866 (16 attendees), preceding Canadian ...

in 1867. An Irish Republican in his early years, he would moderate his view in later years and become a passionate advocate of Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

. He was instrumental in enshrining educational rights for Catholics as a minority group in the Canadian Constitution. In 1868, he was assassinated in Ottawa. Historians are not sure who the murderer was, or what his motivations were. One theory is that a Fenian, Patrick James Whelan

Patrick James Whelan (c. 1840 – 11 February 1869) was a suspected Fenian supporter executed following the 1868 assassination of Irish journalist and politician Thomas D'Arcy McGee.

He maintained his innocence throughout the proceedings, but ...

, was the assassin, attacking McGee for his recent anti-Raid statements. Others argue that Whelan was used as a scapegoat.

After Confederation, Irish Catholics faced more hostility, especially from Protestant Irish in Ontario, which was under the political sway of the already entrenched anti-Catholic Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

. The anthem "The Maple Leaf Forever

"The Maple Leaf Forever" is a Canadian song written by Alexander Muir (1830–1906) in 1867, the year of Canada's Canadian Confederation, Confederation. He wrote the work after serving with the Queen's Own Rifles of Toronto in the Battle of Ridg ...

", written and composed by Scottish immigrant and Orangeman Alexander Muir

Alexander Muir (5 April 1830 – 26 June 1906) was a Canadian songwriter, poet, soldier, and school headmaster. He was the composer of ''The Maple Leaf Forever'', which he wrote in October 1867 to celebrate the Confederation of Canada.

Early l ...

, reflects the pro-British Ulster loyalism outlook typical of the time with its disdainful view of Irish Republicanism

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develop ...

. This only amplified with Fenian Raids of the time. As the Irish became more prosperous and newer groups arrived on Canada's shores, tensions subsided through the remainder the latter part of the 19th century.

In the years between 1815, when vast industrial changes began to disrupt the old life-styles in Europe, and Canadian Confederation in 1867, when immigration of that era passed its peak, more than 150,000 immigrants from Ireland flooded into Saint John, New Brunswick

Saint John is a seaport city of the Atlantic Ocean located on the Bay of Fundy in the province of New Brunswick, Canada. Saint John is the oldest incorporated city in Canada, established by royal charter on May 18, 1785, during the reign of Ki ...

. Those who came in the earlier period were largely tradesmen, and many stayed in Saint John, becoming the backbone of its builders. But when the Great Famine raged between 1845 and 1852, huge waves of refugees arrived at these shores. It is estimated that between 1845 and 1847, some 30,000 arrived, more people than were living in the city at the time. In 1847, dubbed "Black 47", one of the worst years of the Famine, some 16,000 immigrants, most of them from Ireland, arrived at Partridge Island, the immigration and quarantine station at the mouth of Saint John Harbour. From 1840 to 1860 sectarian violence was rampant in Saint John resulting in some of the worst urban riots in Canadian history.

Demography

Population

Religion

Protestantism and Catholicism

Tensions between the Irish Protestants and Irish Catholics were widespread in Canada in the 19th century, with many episodes of violence and anger, especially in Atlantic Canada and Ontario. In New Brunswick, from 1840 to the 1860s sectarian violence was rampant in Saint John resulting in some of the worst urban riots in Canadian history. The city was shaped by Irish ghettos at York Point, and suppression of poor, Irish-speaking peoples rights lead to decades of turmoil. The division would continue to shape Saint John in years to come. TheOrange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

, with its two main tenets, anti-Catholicism and loyalty to Britain, flourished in Ontario. Largely coincident with Protestant Irish settlement, its role pervaded the political, social and community as well as religious lives of its followers. Spatially, Orange lodges were founded as Irish Protestant settlement spread north and west from its original focus on the Lake Ontario plain. Although the number of active members, and thus their influence, may have been overestimated, the Orange influence was considerable and comparable to the Catholic influence in Quebec.

In Montreal in 1853, the Orange Order organized speeches by the fiercely anti-Catholic and anti-Irish former priest Alessandro Gavazzi

Alessandro Gavazzi (21 March 18099 January 1889) was an Italian preacher and patriot. He at first became a monk (1825), and attached himself to the Barnabites at Naples, where he afterwards (1829) acted as professor of rhetoric. He left the chur ...

, resulting in a violent confrontation between the Irish and the Scots. St. Patrick's Day processions in Toronto were often disrupted by tensions, that boiled over to the extent that the parade was cancelled permanently by the mayor in 1878 and not re-instituted until 110 years later in 1988. The Jubilee Riots of 1875 jarred Toronto in a time when sectarian tensions ran at their highest. Irish Catholics in Toronto were an embattled minority among a Protestant population that included a large Irish Protestant contingent strongly committed to the Orange Order.

Geographical distribution

The graph excludes those who have only some Irish ancestry. Historian and journalist Louis-Guy Lemieux claims that about 40% of Quebecers have Irish ancestry on at least one side of their family tree. Shunned by Protestant English-speakers, it was not uncommon for Catholic Irish to settle among and intermarry with the Catholic French-speakers. Considering that many other Canadians throughout Canada likewise have Irish roots, in addition to those who may simply identify as Canadian, the total number of Canadians with some Irish ancestry extrapolated would include a significant proportion of the Canadian population.Quebec

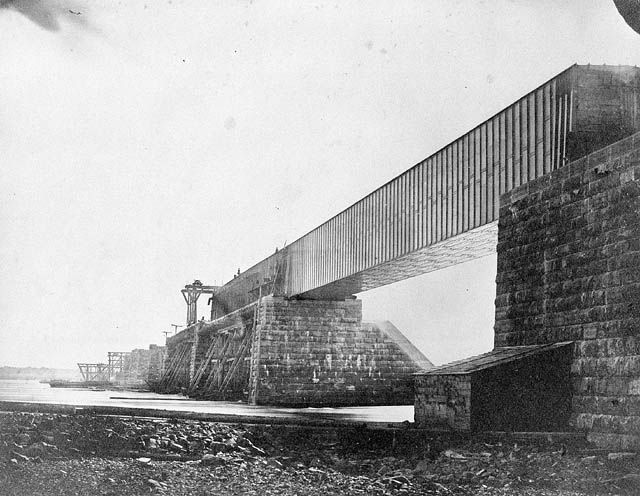

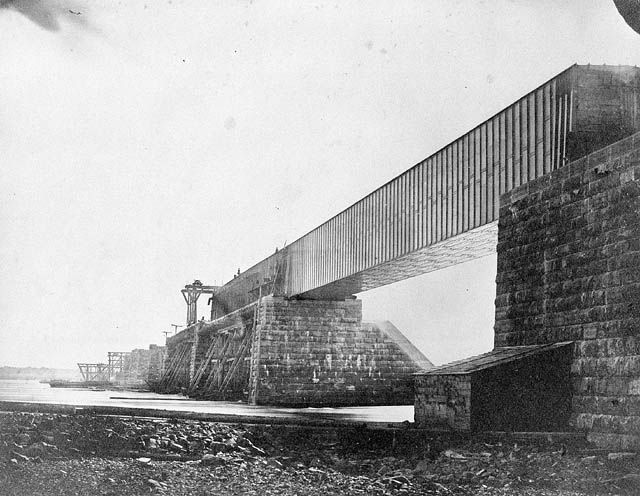

Irish established communities in both urban and rural Quebec. Irish immigrants arrived in large numbers in

Irish established communities in both urban and rural Quebec. Irish immigrants arrived in large numbers in Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

during the 1840s and were hired as labourers to build the Victoria Bridge Victoria Bridge may be a reference to:

Bridges

;Australia

* Victoria Bridge, Brisbane, a road bridge across the Brisbane River in Brisbane

* Victoria Bridge, Devonport a road ridge across the Mersey River in Devonport, Tasmania

* Victoria Bridge, M ...

, living in a tent city at the foot of the bridge. Here, workers unearthed a mass grave of 6,000 Irish immigrants who had died at nearby Windmill Point

Goose Village (French: "Village-aux-Oies") was a neighbourhood in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Its official but less commonly used name was Victoriatown, after the adjacent Victoria Bridge, Montreal, Victoria Bridge. The neighbourhood was built ...

in the typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

outbreak of 1847–48. The Irish Commemorative Stone or "Black Rock", as it is commonly known, was erected by bridge workers to commemorate the tragedy.

The Irish would go on to settle permanently in the close-knit working-class neighbourhoods of Pointe-Saint-Charles, Verdun

Verdun (, , , ; official name before 1970 ''Verdun-sur-Meuse'') is a large city in the Meuse department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

Verdun is the biggest city in Meuse, although the capital ...

, Saint-Henri

Saint-Henri is a neighbourhood in southwestern Montreal, Quebec, Canada, in the borough of Le Sud-Ouest.

Saint-Henri is usually considered to be bounded to the east by Atwater Avenue, to the west by the town of Montreal West, to the north by Au ...

, Griffintown and Goose Village, Montreal

Goose Village (French: "Village-aux-Oies") was a neighbourhood in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Its official but less commonly used name was Victoriatown, after the adjacent Victoria Bridge. The neighbourhood was built on an area formerly known ...

. With the help of Quebec's Catholic Church, they would establish their own churches, schools, and hospitals. St. Patrick's Basilica was founded in 1847 and served Montreal's English-speaking Catholics for over a century. Loyola College was founded by the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

to serve Montreal's mostly Irish English-speaking Catholic community in 1896. Saint Mary's Hospital was founded in the 1920s and continues to serve Montreal's present-day English-speaking population.

The St. Patrick's Day

Saint Patrick's Day, or the Feast of Saint Patrick ( ga, Lá Fhéile Pádraig, lit=the Day of the Festival of Patrick), is a cultural and religious celebration held on 17 March, the traditional death date of Saint Patrick (), the foremost patr ...

Parade in Montreal is one of the oldest in North America, dating back to 1824. It annually attracts crowds of over 600,000 people.

The Irish would also settle in large numbers in Quebec City and establish communities in rural Quebec, particularly in

The Irish would also settle in large numbers in Quebec City and establish communities in rural Quebec, particularly in Pontiac Pontiac may refer to:

*Pontiac (automobile), a car brand

*Pontiac (Ottawa leader) ( – 1769), a Native American war chief

Places and jurisdictions Canada

* Pontiac, Quebec, a municipality

**Apostolic Vicariate of Pontiac, now the Roman Catholic D ...

, Gatineau

Gatineau ( ; ) is a city in western Quebec, Canada. It is located on the northern bank of the Ottawa River, immediately across from Ottawa, Ontario. Gatineau is the largest city in the Outaouais administrative region and is part of Canada's N ...

and Papineau where there was an active timber industry. However, most would move on to larger North American cities.

Today, many Québécois have some Irish ancestry. Examples from political leaders include Laurence Cannon

Lawrence Cannon, (born December 6, 1947) is a Canadian politician from Quebec and Prime Minister Stephen Harper's former Quebec lieutenant. In early 2006, he was made the Minister of Transport. On October 30, 2008, he relinquished oversight of T ...

, Claude Ryan, the former Premiers Daniel Johnson and Jean Charest, Georges Dor (born Georges-Henri Dore), and former Prime Ministers Louis St. Laurent

Louis Stephen St. Laurent (''Saint-Laurent'' or ''St-Laurent'' in French, baptized Louis-Étienne St-Laurent; February 1, 1882 – July 25, 1973) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 12th prime minister of Canada from 19 ...

and Brian Mulroney

Martin Brian Mulroney ( ; born March 20, 1939) is a Canadian lawyer, businessman, and politician who served as the 18th prime minister of Canada from 1984 to 1993.

Born in the eastern Quebec city of Baie-Comeau, Mulroney studied political sci ...

. The Irish constitute the second largest ethnic group in the province after French Canadians

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

.

Ontario

From the times of early European settlement in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Irish had been coming to Ontario, in small numbers and in the service ofNew France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spai ...

, as missionaries, soldiers, geographers and fur trappers. After the creation of British North America in 1763, Protestant Irish, both Irish Anglicans and Ulster-Scottish Presbyterians, had been migrating over the decades to Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the ...

, some as United Empire Loyalists

United Empire Loyalists (or simply Loyalists) is an honorific title which was first given by the 1st Lord Dorchester, the Governor of Quebec, and Governor General of The Canadas, to American Loyalists who resettled in British North America duri ...

or directly from Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

.

In the years after the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, increasing numbers of Irish, a growing proportion of them Catholic, were venturing to Canada to obtain work on projects such as canals, roads, early railroads and in the lumber industry. The labourers were known as ‘navvies’ and built much of the early infrastructure in the province. Settlement schemes offering cheap (or free) land brought over farming families, with many being from Munster (particularly Tipperary

Tipperary is the name of:

Places

*County Tipperary, a county in Ireland

**North Tipperary, a former administrative county based in Nenagh

**South Tipperary, a former administrative county based in Clonmel

*Tipperary (town), County Tipperary's na ...

and Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

). Peter Robinson Peter Robinson may refer to:

Entertainment

* Peter Robinson (sideshow artist) (1873–1947), American actor and sideshow performer, known for his appearance in film ''Freaks'' (1932)

* J. Peter Robinson (born 1945), British musician and film score ...

organized land settlements of Catholic tenant farmers in the 1820s to areas of rural Eastern Ontario, which helped establish Peterborough

Peterborough () is a cathedral city in Cambridgeshire, east of England. It is the largest part of the City of Peterborough unitary authority district (which covers a larger area than Peterborough itself). It was part of Northamptonshire until ...

as a regional centre.

The Irish were instrumental in the building of the Rideau Canal

The Rideau Canal, also known unofficially as the Rideau Waterway, connects Canada's capital city of Ottawa, Ontario, to Lake Ontario and the Saint Lawrence River at Kingston. It is 202 kilometres long. The name ''Rideau'', French for "curtain", ...

and subsequent settlement along its route. Alongside French-Canadians, thousands of Irish laboured in difficult conditions and terrain. Hundreds, if not thousands, died from malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

.

Famine in Ireland

The Great Irish Hunger 1845–1849, had a large impact on Ontario. At its peak in the summer of 1847, boatloads of sick migrants arrived in desperate circumstances on steamers from Quebec toBytown

Bytown is the former name of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. It was founded on September 26, 1826, incorporated as a town on January 1, 1850, and superseded by the incorporation of the City of Ottawa on January 1, 1855. The founding was marked by a Grou ...

(soon to be Ottawa), and to ports of call on Lake Ontario, chief amongst them Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the five most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

and Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

, in addition to many other smaller communities across southern Ontario. Quarantine facilities were hastily constructed to accommodate them. Nurses, doctors, priests, nuns, compatriots, some politicians and ordinary citizens aided them. Thousands died in Ontario that summer alone, mostly from typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

.

How permanent a settlement was depended on circumstances. A case in point is Irish immigration to North Hastings County, Canada West, which happened after 1846. Most of the immigrants were attracted to North Hastings by free land grants beginning in 1856. Three Irish settlements were established in North Hastings: Umfraville, Doyle's Corner, and O'Brien Settlement. The Irish were primarily Roman Catholic. Crop failures in 1867 halted the road program near the Irish settlements, and departing settlers afterward outnumbered new arrivals. By 1870, only the successful settlers, most of whom were farmers who raised grazing animals, remained.

In the 1840s the major challenge for the Catholic Church was keeping the loyalty of the very poor Catholic arrivals during marches. The fear was that Protestants might use their material needs as a wedge for evangelicalization. In response the Church built a network of charitable institutions such as hospitals, schools, boarding homes, and orphanages, to meet the need and keep people inside the faith. The Catholic church was less successful in dealing with tensions between its French and the Irish clergy; eventually the Irish took control.

Sectarian tensions

Toronto had similar numbers of both Irish Protestants and Irish Catholics. Riots or conflicts repeatedly broke out from 1858 to 1878, such as during the annualSt. Patrick's Day

Saint Patrick's Day, or the Feast of Saint Patrick ( ga, Lá Fhéile Pádraig, lit=the Day of the Festival of Patrick), is a cultural and religious celebration held on 17 March, the traditional death date of Saint Patrick (), the foremost patr ...

parade or during various religious processions, which culminated in the Jubilee Riots of 1875. These tensions had increased following the organized but failed Fenian Raids at points along the American border, which arose suspicions by Protestants of Catholics' sympathies toward the Fenian cause. The Irish population essentially defined the Catholic population in Toronto until 1890, when German and French Catholics were welcomed to the city by the Irish, but the Irish were still 90% of the Catholic population. However, various powerful initiatives such as the foundation of St. Michael's College in 1852 (where Marshall McLuhan

Herbert Marshall McLuhan (July 21, 1911 – December 31, 1980) was a Canadian philosopher whose work is among the cornerstones of the study of media theory. He studied at the University of Manitoba and the University of Cambridge. He began his ...

held the chair of English until his death in 1980), three hospitals, and the most significant charitable organizations in the city (the Society of St. Vincent de Paul

The Society of St Vincent de Paul (SVP or SVdP or SSVP) is an international voluntary organization in the Catholic Church, founded in 1833 for the sanctification of its members by personal service of the poor.

Innumerable Catholic parishes have ...

) and House of Providence created by Irish Catholic groups strengthened the Irish identity, transforming the Irish presence in the city into one of influence and power.

From 1840 to 1860 sectarian violence was rampant in Saint John, New Brunswick

Saint John is a seaport city of the Atlantic Ocean located on the Bay of Fundy in the province of New Brunswick, Canada. Saint John is the oldest incorporated city in Canada, established by royal charter on May 18, 1785, during the reign of Ki ...

resulting in some of the worst urban riots in Canadian history. Orange Order parades ended in rioting with Catholics, many Irish-speaking, fighting against increased marginalization trapped in Irish ghettos at York Point and North End areas such as Portland Point. Nativist Protestants had secured their dominance over the city's political systems at the peak of the famine, which saw the New Brunswick city's demographics completely changed with waves of immigration. In three years alone, 1844 to 1847, 30,000 Irish came to Partridge Island, a quarantine station in the city's harbour.

Economic mobility and integration

An economic boom and growth in the years after their arrival allowed many Irish men to obtain steady employment on the rapidly expanding railroad network, settlements developed or expanded along or close to the Grand Trunk Railroad corridor often in rural areas, allowing many to farm the relatively cheap, arable land of southern Ontario. Employment opportunities in the cities, in Toronto but elsewhere, occupations included construction, liquor processing (see Distillery District), Great Lakes shipping, and manufacturing. Women generally entered into domestic service. In more remote areas, employment centred around theOttawa Valley timber trade

The Ottawa River timber trade, also known as the Ottawa Valley timber trade or Ottawa River lumber trade, was the nineteenth century production of wood products by Canada on areas of the Ottawa River and the regions of the Ottawa Valley and west ...

which eventually extending into Northern Ontario along with railroad building and mining. There was a strong Irish rural presence in Ontario in comparison to their brethren in the northern US, but they were also numerous in the towns and cities. Later generations of these poorer immigrants were among those who rose to prominence in unions, business, judiciary, the arts and politics.

Redclift (2003) concluded that many of the one million migrants, mainly of British and Irish origin, who arrived in Canada in the mid-19th century benefited from the availability of land and absence of social barriers to mobility. This enabled them to think and feel like citizens of the new country in a way denied them back in the old country.

Akenson (1984) argued that the Canadian experience of Irish immigrants is not comparable to the American one. He contended that the numerical dominance of Protestants within the national group and the rural basis of the Irish community negated the formation of urban ghettos and allowed for a relative ease in social mobility. In comparison, the American Irish in the Northeast and Midwest were dominantly Catholic, urban dwelling, and ghettoized. There was however, the existence of Irish-centric ghettos in Toronto ( Corktown, Cabbagetown, Trinity Niagara

Niagara is a neighbourhood in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located south of Queen Street West; it is usually bordered by Strachan Avenue to the west, Bathurst Street to the east, and the railway corridor to the south, and so named because Niagara Stre ...

, the Ward) at the fringes of urban development, at least for the first few decades after the famine and in the case of Trefann Court

Trefann Court is a small neighbourhood in the eastern part of downtown Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is located on the north side of Queen Street between Parliament Street and River Street. It extends north only a short distance to Shuter St.

His ...

, a holdout against public housing and urban renewal, up to the 1970s. This was also the case in other Canadian cities with significant Irish Catholic populations such as Montreal, Ottawa and Saint John.

Likewise the new labour historians believe that the rise of the Knights of Labor caused the Orange and Catholic Irish in Toronto to resolve their generational hatred and set about to form a common working-class culture. This theory presumes that Irish-Catholic culture was of little value, to be rejected with such ease. Nicolson (1985) argues that neither theory is valid. He says that in the ghettos of Toronto the fusion of an Irish peasant culture with traditional Catholism produced a new, urban, ethno-religious vehicle – Irish Tridentine Catholism. This culture spread from the city to the hinterland and, by means of metropolitan linkage, throughout Ontario. Privatism created a closed Irish society, and, while Irish Catholics cooperated in labour organizations for the sake of their families' future, they never shared in the development of a new working-class culture with their old Orange enemies.

McGowan argues that between 1890 and 1920, the city's Catholics experienced major social, ideological, and economic changes that allowed them to integrate into Toronto society and shake off their second-class status. The Irish Catholics (in contrast to the French) strongly supported Canada's role in the First World War. They broke out of the ghetto and lived in all of Toronto's neighbourhoods. Starting as unskilled labourers, they used high levels of education to move up and were well represented among the lower middle class. Most dramatically, they intermarried with Protestants at an unprecedented rate.

Confederation

WithCanadian Confederation

Canadian Confederation (french: Confédération canadienne, link=no) was the process by which three British North American provinces, the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, were united into one federation called the Canada, Dom ...

in 1867, Catholics were granted a separate school board. Through the late 19th and early 20th century, Irish immigration to Ontario continued but a slower pace, much of it family reunification. Out-migration of Irish in Ontario (along with others) occurred during this period following economic downturns, available new land and mining booms in the US or the Canadian West. The reverse is true of those with Irish descent who migrated to Ontario from the Maritimes and Newfoundland seeking work, mostly since World War II.

In 1877, a breakthrough in Irish Canadian Protestant-Catholic relations occurred in London, Ontario

London (pronounced ) is a city in southwestern Ontario, Canada, along the Quebec City–Windsor Corridor. The city had a population of 422,324 according to the 2021 Canadian census. London is at the confluence of the Thames River, approximate ...

. This was the founding of the Irish Benevolent Society, a brotherhood of Irishmen and women of both Catholic and Protestant faiths. The society promoted Irish Canadian culture, but it was forbidden for members to speak of Irish politics when meeting. Today, the Society is still operating.

Some writers have assumed that the Irish in 19th-century North America were impoverished. DiMatteo (1992), using evidence from probate records in 1892, shows this is untrue. Irish-born and Canadian-born Irish accumulated wealth in a similar way, and that being Irish was not an economic disadvantage by the 1890s. Immigrants from earlier decades may well have experienced greater economic difficulties, but in general the Irish in Ontario in the 1890s enjoyed levels of wealth commensurate with the rest of the populace.

By 1901 Ontario Irish Catholics and Scottish Presbyterians were among the most likely to own homes, while Anglicans did only moderately well, despite their traditional association with Canada's elite. French-speaking Catholics in Ontario achieved wealth and status less readily than Protestants and Irish Catholics. Although differences in attainment existed between people of different religious denominations, the difference between Irish Catholics and Irish Protestants in urban Canada was relatively insignificant.

20th century

Ciani (2008) concludes that support of World War I fostered an identity among Irish Catholics as loyal citizens and helped integrate them into the social fabric of the nation. Rev. Michael Fallon, the Catholic bishop of London, sided with the Protestants against the French Catholics. His primary motive was to advance the cause of Irish Catholics in Canada and abroad; he had significant support from the Vatican. He opposed the French Canadian Catholics, especially by opposing bilingual education. French Canadians did not participate in Fallon's efforts to support the war effort and became more marginalized in Ontario politics and society.Present

Today, the impact of the heavy 19th-century Irish immigration to Ontario is evident as those who report Irish extraction in the province number close to 2 million people or almost half the total Canadians who claim Irish ancestry. In 2004, March 17 was proclaimed "Irish Heritage Day" by theOntario Legislature

The Legislative Assembly of Ontario (OLA, french: Assemblée législative de l'Ontario) is the legislative chamber of the Canadian province of Ontario. Its elected members are known as Members of Provincial Parliament (MPPs). Bills passed by ...

in recognition of the immense Irish contribution to the development of the Province.

Ontario sustains a network of Irish language enthusiasts, many of whom see the language as part of their ethnic heritage. Ontario is also home to Gaeltacht Bhuan Mheiriceá Thuaidh

The North American Gaeltacht () is a gathering place for Irish speakers in the community of Tamworth, Ontario, in Canada. The nearest main township is Erinsville, Ontario. Unlike in Ireland, where the term "" refers to an area where Irish is t ...

(the Permanent North American Gaeltacht

( , , ) are the districts of Ireland, individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The ''Gaeltacht'' districts were first officially recog ...

), an area which hosts cultural activities for Irish speakers and learners and has been recognized by the Irish government."Canada to have first Gaeltacht." ''Irish Emigrant'' Jan 2007.With the downturn of Ireland's economy in 2010, many Irish people came to Canada looking for work, or to pre-arranged employment. There are many communities in Ontario that are named after places and last names of Ireland, including Ballinafad, Ballyduff, Ballymote,

Cavan

Cavan ( ; ) is the county town of County Cavan in Ireland. The town lies in Ulster, near the border with County Fermanagh in Northern Ireland. The town is bypassed by the main N3 road that links Dublin (to the south) with Enniskillen, Bally ...

, Connaught, Connellys, Dalton, Donnybrook

Donnybrook may refer to:

Places Australia

* Donnybrook, Queensland, Australia

* Donnybrook, Western Australia

* Donnybrook, Victoria, Australia

** Donnybrook railway station, Victoria, Australia

Canada

* Donnybrook, Ontario, a former village in ...

, Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, Dundalk

Dundalk ( ; ga, Dún Dealgan ), meaning "the fort of Dealgan", is the county town (the administrative centre) of County Louth, Ireland. The town is on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the east coast of Ireland. It is h ...

, Dunnville, Enniskillen

Enniskillen ( , from ga, Inis Ceithleann , 'Cethlenn, Ceithlenn's island') is the largest town in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. It is in the middle of the county, between the Upper and Lower sections of Lough Erne. It had a population of ...

, Erinsville, Galway

Galway ( ; ga, Gaillimh, ) is a City status in Ireland, city in the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, which is the county town of County Galway. It lies on the River Corrib between Lo ...

, Hagarty

Hagarty is an Irish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* John Hawkins Hagarty (1816–1900), Canadian lawyer, teacher and judge

* Lois Sherman Hagarty (born 1948), former Republican member of the Pennsylvania House of Represent ...

, Irish Lake

Watonwan County is a county in the U.S. state of Minnesota. As of the 2020 census, the population was 11,253. Its county seat is St. James.

History

In 1849, the recently organized Minnesota Territory legislature authorized the creation of nin ...

, Kearney, Keenansville, Kennedys

The Kennedy family is an American political family that has long been prominent in American politics, public service, entertainment, and business. In 1884, 35 years after the family's arrival from Ireland, Patrick Joseph "P. J." Kennedy be ...

, Killaloe, Killarney, Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

, Listowel

Listowel ( ; , IPA: �lʲɪsˠˈt̪ˠuəhəlʲ is a heritage market town in County Kerry, Ireland. It is on the River Feale, from the county town, Tralee. The town of Listowel had a population of 4,820 according to the Central Statistics Of ...

, Lucan

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (3 November 39 AD – 30 April 65 AD), better known in English as Lucan (), was a Roman poet, born in Corduba (modern-day Córdoba), in Hispania Baetica. He is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imperial ...

, Maguire

Maguire ( , also spelled MacGuire or McGuire) is an Irish surname from the Gaelic , which is "son of Odhar" meaning "dun", "dark one". According to legend, this relates to the eleventh descendant of Colla da Chrich, great-grandson of Cormac mac ...

, Malone

Malone is an Irish surname. From the Irish "''Mael Eóin''", the name means a servant or a disciple of Saint John.

People

* Gilla Críst Ua Máel Eóin (died 1127), historian and Abbot of Clonmacnoise, Ó Maoil Eoin

* Adrian Malone (1937–2 ...

, McGarry

McGarry is a surname of Irish origin meaning "the son of Fearadhach." It is the 422nd most common surname in Ireland, and 722nd in Scotland.

List of people surnamed McGarry

* Andrew McGarry (born 1981), English cricketer

* Anna McGarry (1894–197 ...

, Moffat, Mullifarry, Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

, Navan, New Dublin, O'Connell O'Connell may refer to:

People

*O'Connell (name), people with O'Connell as a last name or given name

Schools

* Bishop Denis J. O'Connell High School, a high school in Arlington, Virginia

Places

* Mount O'Connell National Park in Queensland ...

, Oranmore, Quinn Settlement, Ripley

Ripley may refer to:

People and characters

* Ripley (name)

* ''Ripley'', the test mannequin aboard the first International Space Station space station Dragon 2 space test flight Crew Dragon Demo-1

* Ellen Ripley, a fictional character from the Ali ...

, Shamrock

A shamrock is a young sprig, used as a symbol of Ireland. Saint Patrick, Ireland's patron saint, is said to have used it as a metaphor for the Christian Holy Trinity. The name ''shamrock'' comes from Irish (), which is the diminutive of ...

, Tara, South Monaghan, Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

and Westport.

New Brunswick

Miramichi River valley

The Miramichi Valley is a Canadian river valley and region in the east-central part of New Brunswick. It extends along both major branches of the Miramichi River and their tributaries, however it is generally agreed that the much larger Southwe ...

, received a significant Irish immigration in the years before the famine. These settlers tended to be better off and better educated than the later arrivals, who came out of desperation. Though coming after the Scottish and the French Acadians, they made their way in this new land, intermarrying with the Catholic Highland Scots, and to a lesser extent, with the Acadians. Some, like Martin Cranney

Martin Cranney (1795–1870) was an Irish-born New Brunswick politician. He was a resident of Chatham, New Brunswick and represented Northumberland County in the 14th New Brunswick Legislative Assembly from 1847 to 1850.

Cranney came to New Br ...

, held elective office and became the natural leaders of their augmented Irish community after the arrival of the famine immigrants. The early Irish came to the Miramichi because it was easy to get to with lumber ships stopping in Ireland before returning to Chatham and Newcastle, and because it provided economic opportunities, especially in the lumber industry. They were commonly Irish speakers, and in the eighteen thirties and eighteen forties there were many Irish-speaking communities along the New Brunswick and Maine frontier.

Long a timber-exporting colony, New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

became the destination of thousands of Irish immigrants in the form of refugees fleeing the famines during the mid-19th century as the timber cargo vessels provided cheap passage when returning empty to the colony. Quarantine hospitals were located on islands at the mouth of the colony's two major ports, Saint John ( Partridge Island) and Chatham

Chatham may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions Canada

* Chatham Islands (British Columbia)

* Chatham Sound, British Columbia

* Chatham, New Brunswick, a former town, now a neighbourhood of Miramichi

* Chatham (electoral district), New Brunswic ...

- Newcastle ( Middle Island), where many would ultimately die. Those who survived settled on marginal agricultural lands in the Miramichi River valley

The Miramichi Valley is a Canadian river valley and region in the east-central part of New Brunswick. It extends along both major branches of the Miramichi River and their tributaries, however it is generally agreed that the much larger Southwe ...

and in the Saint John River and Kennebecasis River

The Kennebecasis River ( ) is a tributary of the Saint John River in southern New Brunswick, Canada. The name Kennebecasis is thought to be derived from the Mi'kmaq "''Kenepekachiachk''", meaning "little long bay place." It runs for approximately ...

valleys. The difficulty of farming these regions, however, saw many Irish immigrant families moving to the colony's major cities within a generation or to Portland, Maine or Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

.

Saint John and Chatham, New Brunswick saw large numbers of Irish migrants, changing the nature and character of both municipalities. Today, all of the amalgamated city of Miramichi The name "Miramichi" was first applied to a region in the northeast of New Brunswick, Canada, and has since been applied to other places in Canada and the United States. Although other interpretations have been suggested, it is believed that "Mirami ...

continues to host a large annual Irish festival. Indeed, Miramichi is one of the most Irish communities in North America, second possibly only to Saint John or Boston.

As in Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, the Irish language survived as a community language in New Brunswick into the twentieth century. The 1901 census specifically enquired as to the mother tongue of the respondents, defining it as a language commonly spoken in the home. There were several individuals and a scattering of families in the census who described Irish as their first language and as being spoken at home. In other respects the respondents had less in common, some being Catholic and some Protestant.

Prince Edward Island

For years,Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen Provinces and territories of Canada, provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has seve ...

had been divided between Irish Catholics and British Protestants (which included Ulster Scots Ulster Scots, may refer to:

* Ulster Scots people

* Ulster Scots dialect

Ulster Scots or Ulster-Scots (', ga, Albainis Uladh), also known as Ulster Scotch and Ullans, is the dialect of Scots language, Scots spoken in parts of Ulster in North ...

from Northern Ireland). In the latter half of the 20th century, this sectarianism diminished and was ultimately destroyed recently after two events occurred. First, the Catholic and Protestant school boards were merged into one secular institution; second, the practice of electing two MLAs for each provincial riding (one Catholic and one Protestant) was ended.

History

According to professor ''emeritus'', Brendan O'Grady, a history professor at theUniversity of Prince Edward Island

The University of Prince Edward Island (UPEI) is a public university in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada, and the only university in the province. Founded in 1969, the enabling legislation is the ''University Act, R.S.P.E.I 2000.''

H ...

for fifty years, before the Great Famine of 1845–1852, in which a million Irish died and another million emigrated, the majority of Irish immigrants had already arrived on Prince Edward Island. One coffin ship

A coffin ship () was any of the ships that carried Irish immigrants escaping the Great Irish Famine and Highlanders displaced by the Highland Clearances.

Coffin ships carrying emigrants, crowded and disease-ridden, with poor access to food ...

landed on the Island in 1847.

The first waves of Irish immigrants took place between 1763 and 1880. when ten thousand Irish immigrants arrived on the Island. From 1800 to 1850, "10,000 immigrants from every county in Ireland" had settled in Prince Edward Island and represented 25% of the Island population by 1850. With some funding from the Community Museums Association of Prince Edward Island's Museum Development Grant.

The British divided St John's Island, following 1763, was divided into dozens of lots that were granted to "influential individuals in Britain" with conditions for land ownership including the settlement of each lot by 1787 by British Protestants.

From 1767 through 1810 English speaking Irish Protestants were brought to the colony as colonial pioneers to establish the British system of government with its institutions and laws. The Irish-born Captain Walter Patterson was the first Governor of St John's Island from 1769 until he was removed from office by Whitehall in 1787. According to the ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography

The ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography'' (''DCB''; french: Dictionnaire biographique du Canada) is a dictionary of biographical entries for individuals who have contributed to the history of Canada. The ''DCB'', which was initiated in 1959, is a ...

'', what became known as the century-long "land question", originated with Patterson's failure as administrator of a colony whose lands were owned by a monopoly of British absentee proprietors who demanded rent from their Island tenants.

In May 1830 the first ship of families from County Monaghan, in the province of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

, Ireland accompanied by Father John MacDonald who had recruited them, arrived on the Island to settle in Fort Augustus

Fort Augustus is a settlement in the parish of Boleskine and Abertarff, at the south-west end of Loch Ness, Scottish Highlands. The village has a population of around 646 (2001). Its economy is heavily reliant on tourism.

History

The Gaeli ...

, on the lots inherited by Father John MacDonald from his father Captain John MacDonald. From the 1830s through 1848, 3,000 people emigrated from County Monaghan to PEI in what became known as the Monaghan settlements, forming the largest group of Irish to arrive on the Island in the first half of the 19th century.

Newfoundland

Benevolent Irish Society

The Benevolent Irish Society (BIS) is a philanthropic organization founded on 17 February 1806, a month before the Feast of St. Patrick, in St. John's, Newfoundland. It is the oldest philanthropic organization in North America. Membership is op ...

(BIS) was founded as a philanthropic organization in St. John's, Newfoundland

St. John's is the capital and largest city of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, located on the eastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland.

The city spans and is the easternmost city in North America ...

for locals of Irish birth or ancestry, regardless of religious persuasion. The BIS was founded as a charitable, fraternal, middle-class social organization, on the principles of "benevolence and philanthropy", and had as its original objective to provide the necessary skills which would enable the poor to better themselves. Today the society is still active in Newfoundland and is the oldest philanthropic organization in North America.

Newfoundland Irish Catholics, mainly from the southeast of Ireland, settled in the cities (mainly St. John's and parts of the surrounding Avalon Peninsula

The Avalon Peninsula (french: Péninsule d'Avalon) is a large peninsula that makes up the southeast portion of the island of Newfoundland. It is in size.

The peninsula is home to 270,348 people, about 52% of Newfoundland's population, according ...

), while British Protestants, mainly from the West Country, settled in small fishing communities. Over time, the Irish Catholics became wealthier than their Protestant neighbours, which gave incentive for Protestant Newfoundlanders to join the Orange Order. In 1903, Sir William Coaker founded the Fisherman's Protective Union

The Fishermen's Protective Union (sometimes called the Fisherman's Protective Union, the FPU, The Union or the Union Party) was a workers' organisation and political party in the Dominion of Newfoundland. The development of the FPU mirrored that ...

in an Orange Hall in Herring Neck. Furthermore, during the term of Commission of Government (1934–1949), the Orange Lodge was one of only a handful of "democratic" organizations that existed in the Dominion of Newfoundland

Newfoundland was a British dominion in eastern North America, today the modern Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It was established on 26 September 1907, and confirmed by the Balfour Declaration of 1926 and the Statute of Westmi ...

. In 1948, a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

was held in Newfoundland as to its political future; the Irish Catholics mainly supported a return to independence for Newfoundland as it existed before 1934, while the Protestants mainly supported joining the Canadian Confederation

Canadian Confederation (french: Confédération canadienne, link=no) was the process by which three British North American provinces, the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, were united into one federation called the Canada, Dom ...

. Newfoundland then joined Canada by a 52–48% margin, and with an influx of Protestants into St. John's after the closure of the east coast cod fishery in the 1990s, the main issues have become one of Rural vs. Urban interests rather than anything ethnic or religious.

To Newfoundland, the Irish gave the still-familiar family names of southeast Ireland: Walsh, Power, Murphy, Ryan, Whelan, Phelan, O'Brien, Kelly, Hanlon, Neville, Bambrick, Halley, Houlihan, Hogan, Dillon, Byrne, Quigley, Burke, and FitzGerald. Irish place names are less common, many of the island's more prominent landmarks having already been named by early French and English explorers. Nevertheless, Newfoundland's Ballyhack, Cappahayden, Kilbride, St. Bride's, Port Kirwan, Waterford Valley, Windgap and Skibereen all point to Irish antecedents.

Along with traditional names, the Irish brought their native tongue. Newfoundland is the only place outside Europe with its own distinctive name in the Irish language, ''Talamh an Éisc'', "the land of fish". Eastern Newfoundland was one of the few places outside Ireland where the Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

was spoken by a majority of the population as their primary language. Newfoundland Irish

The Irish language was once widely spoken on the island of Newfoundland before largely disappearing there by the early 20th century.Newfoundland English both lexically (in words like ''angishore'' and ''sleveen'') and grammatically (the ''after'' past-tense construction, for instance).

The family names, the features and colouring, the predominant

The Irish in Ontario: A Study in Rural History

' (McGill-Queen's University Press, 1984) * Akenson, Donald H. ''Small Differences: Irish Catholics and Irish Protestants, 1815–1922: An International Perspective'' (Mcgill-Queen's Studies in the History of Religion) (1991

excerpt and text search

* * Clarke, B. P.

Piety and Nationalism: Lay Voluntary Associations and the Creation of an Irish-Catholic Community in Toronto 1850–1895

' (1993). * Cottrell, Michael. "St. Patrick's Day parades in nineteenth-century Toronto: Study of immigrant adjustment and elite control." In

Irish Famine Immigration and the Social Structure of Canada West

" ''Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology'' 12 (1965): 19-40 * Elliott, Bruce S.

Irish Migrants in the Canadas: A New Approach

' (McGill-Queen's University Press, 1988) * Elliott, Bruce C.

Irish Protestants

" in Paul Robert Magocsi, ed. ''Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples'' (1999), 763-83 * Hedican, Edward J.

What Determines Family Size? Irish Farming Families in Nineteenth-Century Ontario

" ''Journal of Family History'' 2006 31(4): 315-334 * Houston, Cecil J., and William J. Smyth. ''Irish Emigration and Canadian Settlement. Patterns, Links and Letters'' (University of Toronto Press, 1990), geographical study * * Jenkins, W. "Between the Lodge and the Meeting-House: Mapping Irish Protestant Identities and Social Worlds in late Victorian Toronto," ''Social and Cultural Geography'' (2003) 4:75-98. * Jenkins, William (2013). ''Between Raid and Rebellion: The Irish in Buffalo and Toronto, 1867-1916.'' Montreal: McGill-Queen's University. * Jenkins, W. "Patrolmen and Peelers: Immigration, Urban Culture, and the 'Irish Police' in Canada and the United States,"

Canadian Journal of Irish Studies

' 28, no, 2 and 29, no, 1 (2002/03): 10-29. * McGowan, M, G.

The Waning of the Green: Catholics, the Irish, and Identity in Toronto 1887–1922

' (1999) * Magocsi, Paul R. ''Encyclopedia of Canada's peoples'' (1999) 1334pp covering all major groups; Irish on pp 734–83

excerpt and text search

* Mannion, John J. ''Irish Settlements in Eastern Canada: A Study of Cultural Transfer and Adaptation'' (University of Toronto Press, 1974) * Murphy, Terrence, and Gerald Stortz, eds.

Creed and Culture. The Place of English-Speaking Catholics in Canadian Society 1750–1930

'' (McGill-Queen's University Press, 1993) * O’Driscoll, Robert & Reynolds, Lorna (eds.) (1988). ''The Untold story: The Irish in Canada'', Volume II. Celtic Arts of Canada. * Punch, Terence M. ''Irish Halifax: The Immigrant Generation, 1815–1859'' (Halifax: International Education Centre, Saint Mary's University, 1981); * * * * Toner, Peter M. "The Origins of the New Brunswick Irish, 1851," ''Journal of Canadian Studies'' 23 #1-2 (1988): 104–119 * * Wilson, David A. "The Irish in Canada'' (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 1989), short overview * Wilson, David A., ed. ''Irish Nationalism in Canada'' (2009

excerpt and text search

* Leitch, Gillian Irene. "Community and Identity in Nineteenth Century Montreal: The Founding of Saint Patrick's Church." University of Ottawa Canada, 2009. * Horner, Dan. "‘If the Evil Now Growing around Us Be Not Staid’: Montreal and Liverpool Confront the Irish Famine Migration as a Transnational Crisis in Urban Governance." Histoire Sociale/Social History 46, no. 92 (2013): 349–366.

The Shamrock and the Maple Leaf: Irish-Canadian Documentary Heritage at Library and Archives Canada

{{Irish diaspora Irish *

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

religion, the prevalence of Irish music – even the dialect and accent of the people – are so reminiscent of rural Ireland that Irish author Tim Pat Coogan has described Newfoundland as "the most Irish place in the world outside of Ireland". Tim Pat Coogan, "Wherever Green Is Worn: The Story of the Irish Diaspora", Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

The United Irish Uprising

The United Irish Uprising in Newfoundland was a failed mutiny by Irish soldiers in the British garrison in St. John's, Newfoundland on 24 April 1800.

Background

In 1798, a failed rebellion against British rule in Ireland occurred. A larg ...

occurred during April 1800, in St. John's, Newfoundland

St. John's is the capital and largest city of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, located on the eastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland.

The city spans and is the easternmost city in North America ...

where up to 400 Irishmen

The Irish ( ga, Muintir na hÉireann or ''Na hÉireannaigh'') are an ethnic group and nation native to the island of Ireland, who share a common history and culture. There have been humans in Ireland for about 33,000 years, and it has been co ...

had taken the secret oath of the Society of the United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association in the Kingdom of Ireland formed in the wake of the French Revolution to secure "an equal representation of all the people" in a national government. Despairing of constitutional reform, ...

. The Colony of Newfoundland

Newfoundland Colony was an English and, later, British colony established in 1610 on the island of Newfoundland off the Atlantic coast of Canada, in what is now the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. That followed decades of sporadic English ...

rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

was the only one to occur which the British administration linked directly to the Irish Rebellion of 1798. The uprising in St. John's was significant in that it was the first occasion on which the Irish in Newfoundland deliberately challenged the authority of the state, and because the British feared that it might not be the last. It earned for Newfoundland a reputation as a ''Transatlantic Tipperary

Tipperary is the name of:

Places

*County Tipperary, a county in Ireland

**North Tipperary, a former administrative county based in Nenagh

**South Tipperary, a former administrative county based in Clonmel

*Tipperary (town), County Tipperary's na ...

''–a far-flung but semi-Irish colony with the potential for political chaos. Seven Irishman were hanged by the crown because of the uprising.

According to the 2001 Canadian census, the largest ethnic group in Newfoundland and Labrador is English (39.4%), followed by Irish (39.7%), Scottish (6.0%), French (5.5%), and First Nations (3.2%). While half of all respondents also identified their ethnicity as "Canadian", 38% report their ethnicity as "Newfoundlander" in a 2003 Statistics Canada Ethnic Diversity Survey.

Accordingly, the largest single religious denomination by number of adherents according to the 2001 census was the Roman Catholic Church, at 36.9% of the province's population (187,405 members). The major Protestant denominations make up 59.7% of the population, with the largest group being the Anglican Church of Canada at 26.1% of the total population (132,680 members), the United Church of Canada at 17.0% (86,420 members), and the Salvation Army at 7.9% (39,955 members), with other Protestant denominations in much smaller numbers. The Pentecostal Church made up 6.7% of the population with 33,840 members. Non-Christians made up only 2.7% of the total population, with the majority of those respondents indicating "no religion" (2.5% of the total population).

According to the Statistics Canada 2006 census, 21.5% of Newfoundlanders claim Irish ancestry (other major groups in the province include 43.2% English, 7% Scottish, and 6.1% French). In 2006, Statistics Canada have listed the following ethnic origins in Newfoundland; 216,340 English, 107,390 Irish, 34,920 Scottish, 30,545 French, 23,940 North American Indian etc.