Interpol Notice Logos on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The International Criminal Police Organization (ICPO; french: link=no, Organisation internationale de police criminelle), commonly known as Interpol ( , ), is an

The early 20th century saw several more efforts to formalize international police cooperation, as growing international travel and commerce facilitated transnational criminal enterprises and fugitives of the law. The earliest was the International Criminal Police Congress hosted by

The early 20th century saw several more efforts to formalize international police cooperation, as growing international travel and commerce facilitated transnational criminal enterprises and fugitives of the law. The earliest was the International Criminal Police Congress hosted by

Contrary to the common idea due to frequent portrayals in popular media, Interpol is not a

Contrary to the common idea due to frequent portrayals in popular media, Interpol is not a

international organization

An international organization or international organisation (see spelling differences), also known as an intergovernmental organization or an international institution, is a stable set of norms and rules meant to govern the behavior of states a ...

that facilitates worldwide police cooperation and crime control. Headquartered in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

, France, it is the world's largest international police organization, with seven regional bureaus worldwide and a National Central Bureau in all 195 member states.

Interpol was conceived during the first International Criminal Police Congress in 1914, which brought officials from 24 countries to discuss cooperation in law enforcement. It was founded on September 7, 1923 at the close of the five-day 1923 Congress session in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

as the International Criminal Police Commission (ICPC); it adopted many of its current duties throughout the 1930s. After coming under Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hit ...

control in 1938, the agency had its headquarters in the same building as the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one or ...

. It was effectively moribund until the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. In 1956, the ICPC adopted a new constitution and the name Interpol, derived from its telegraphic address

A telegraphic address or cable address was a unique identifier code for a recipient of telegraph messages. Operators of telegraph services regulated the use of telegraphic addresses to prevent duplication. Rather like a uniform resource locator ( ...

used since 1946.

Interpol provides investigative support, expertise and training to law enforcement worldwide, focusing on three major areas of transnational crime Transnational crimes are crimes that have actual or potential effect across national borders and crimes that are intrastate but offend fundamental values of the international community. The term is commonly used in the law enforcement and academic c ...

: terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

, cybercrime

A cybercrime is a crime that involves a computer or a computer network.Moore, R. (2005) "Cyber crime: Investigating High-Technology Computer Crime," Cleveland, Mississippi: Anderson Publishing. The computer may have been used in committing t ...

and organized crime

Organized crime (or organised crime) is a category of transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally tho ...

. Its broad mandate covers virtually every kind of crime, including crimes against humanity, child pornography

Child pornography (also called CP, child sexual abuse material, CSAM, child porn, or kiddie porn) is pornography that unlawfully exploits children for sexual stimulation. It may be produced with the direct involvement or sexual assault of a chi ...

, drug trafficking

A drug is any chemical substance that causes a change in an organism's physiology or psychology when consumed. Drugs are typically distinguished from food and substances that provide nutritional support. Consumption of drugs can be via insuffla ...

and production, political corruption, intellectual property infringement

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator ...

, as well as white-collar crime

The term "white-collar crime" refers to financially motivated, nonviolent or non-directly violent crime committed by individuals, businesses and government professionals. It was first defined by the sociologist Edwin Sutherland in 1939 as "a ...

. The agency also facilitates cooperation among national law enforcement institutions through criminal databases and communications networks. Contrary to popular belief, Interpol is itself not a law enforcement agency.

Interpol has an annual budget of €142 million, most of which comes from annual contributions by member police forces in 181 countries. It is governed by a General Assembly composed of all member countries, which elects the executive committee and the President (currently Ahmed Naser Al-Raisi

Ahmed Naser Al-Raisi (also romanised as Ahmed Nasser Al-Raisi) is an Emirati military general officer. He currently serves as the 30th president of Interpol and the inspector general of the United Arab Emirates' interior ministry.

Early career ...

of the United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia ( The Middle East). It is located at ...

) to supervise and implement Interpol's policies and administration. Day-to-day operations are carried out by the General Secretariat, comprising around 1,000 personnel from over 100 countries, including both police and civilians. The Secretariat is led by the Secretary-General, currently Jürgen Stock

Jürgen Stock (born October 4, 1959) is a German police officer and academic. He has served as secretary general of Interpol since November 7, 2014.

Biography

Stock was born on October 4, 1959, in Wetzlar, Germany. He joined the Kriminalpolizei i ...

, the former deputy head of Germany's Federal Criminal Police Office.

Pursuant to its charter, Interpol seeks to remain politically neutral

Apoliticism is apathy or antipathy towards all political affiliations. A person may be described as apolitical if they are uninterested or uninvolved in politics. Being apolitical can also refer to situations in which people take an unbiased po ...

in fulfilling its mandate, and is thus barred from interventions or activities that are political, military, religious, or racial in nature and from involving itself in disputes over such matters. The agency operates in four languages: Arabic, English, French and Spanish.

History

Until the 19th century, cooperation among police in different national and political jurisdictions was organized largely on an ''ad hoc'' basis, focused on a specific goal or criminal enterprise. The earliest attempt at a formal, permanent framework for international police coordination was the Police Union of German States, formed in 1851 to bring together police from various German-speaking states. Its activities were centered mostly on political dissidents and criminals. A similar plan was launched by Italy in the 1898 Anti-Anarchist Conference of Rome, which brought delegates from 21 European countries to create a formal structure for addressing the international anarchist movement. Neither the conference nor its follow up meeting in St. Petersburg in 1904 yielded results.Monaco

Monaco (; ), officially the Principality of Monaco (french: Principauté de Monaco; Ligurian: ; oc, Principat de Mónegue), is a sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title which can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word ...

in 1914, which brought police and legal officials from two dozen countries to discuss international cooperation in investigating crimes, sharing investigative techniques, and extradition procedures. The Monaco Congress laid out twelve principles and priorities that would eventually become foundational to Interpol, including providing direct contact between police in different nations; creating an international standard for forensics and data collection; and facilitating the efficient processing of extradition requests. The idea of an international police organization remained dormant due to the First World War. The United States attempted to lead a similar effort in 1922 through the International Police Conference in New York City, but it failed to attract international attention.

A year later, in 1923, a new initiative was undertaken at another International Criminal Police Congress in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, spearheaded by Johannes Schober

Johannes "Johann" Schober (born 14 November 1874 in Perg; died 19 August 1932 in Baden bei Wien) was an Austrian jurist, law enforcement official, and politician. Schober was appointed Vienna Chief of Police in 1918 and became the founding presid ...

, President of the Viennese Police Department. The 22 delegates agreed to found the International Criminal Police Commission (ICPC), the direct forerunner of Interpol, which would be based in Vienna. Founding members included police officials from Austria, Germany, Belgium, Poland, China, Egypt, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Japan, Romania, Sweden, Switzerland and Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

. The same year, wanted person notices were first published in the ICPC's International Public Safety Journal. The United Kingdom joined in 1928. The United States did not join Interpol until 1938, although a U.S. police officer unofficially attended the 1923 congress. By 1934, the ICPC's membership more than doubled to 58 nations.

Following the ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the Nazi Germany, German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a "Ger ...

'' in 1938, the Viennese-based organization fell under the control of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

; the commission's headquarters were eventually moved to Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

in 1942. Most member states withdrew their support during this period. From 1938 to 1945, the presidents of the ICPC included Otto Steinhäusl

Otto Steinhäusl (10 March 1879 – 20 June 1940) was an Austrian-born SS-''Oberführer'', Polizeipräsident (Police President) of Vienna, and President of Interpol (1938–1940).

Early career

Steinhäusl served as Vienna's head of police and Po ...

, Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inc ...

, Arthur Nebe

Arthur Nebe (; 13 November 1894 – 21 March 1945) was a German SS functionary who was key in the security and police apparatus of Nazi Germany and from 1941, a major perpetrator of the Holocaust.

Nebe rose through the ranks of the Prussian ...

and Ernst Kaltenbrunner

Ernst Kaltenbrunner (4 October 190316 October 1946) was a high-ranking Austrian SS official during the Nazi era and a major perpetrator of the Holocaust. After the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in 1942, and a brief period under Heinric ...

. All were generals in the ''Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS; also stylized as ''ᛋᛋ'' with Armanen runes; ; "Protection Squadron") was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe d ...

'' (SS); Kaltenbrunner was the highest-ranking SS officer executed following the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945, Nazi Germany invaded ...

.

In 1946, after the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, the organization was revived as the International Criminal Police Organization (ICPO) by officials from Belgium, France, Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

, the United States and the United Kingdom. Its new headquarters were established in Paris, then from 1967 in Saint-Cloud

Saint-Cloud () is a commune in the western suburbs of Paris, France, from the centre of Paris. Like other communes of Hauts-de-Seine such as Marnes-la-Coquette, Neuilly-sur-Seine and Vaucresson, Saint-Cloud is one of France's wealthiest to ...

, a Parisian suburb. They remained there until 1989 when they were moved to their present location in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

.

Until the 1980s, Interpol did not intervene in the prosecution of Nazi war criminals

The following is a list of people who were formally indicted for committing war crimes on behalf of the Axis powers during World War II, including those who were acquitted or never received judgment. It does not include people who may have commi ...

in accordance with Article 3 of its Charter, which prohibited intervention in "political" matters.

In July 2010, former Interpol President Jackie Selebi

Jacob "Jackie" Sello Selebi (7 March 195023 January 2015) was the National Commissioner of the South African Police Service from January 2000 to January 2008, when he was put on extended leave and charged with corruption. He was also a former Pre ...

was found guilty of corruption by the South African High Court

The High Court of South Africa is a superior court of law in South Africa. It is divided into nine provincial divisions, some of which sit in more than one location. Each High Court division has general jurisdiction over a defined geographical ...

in Johannesburg for accepting bribes worth €156,000 ($) from a drug trafficker. After being charged in January 2008, Selebi resigned as president of Interpol and was put on extended leave as National Police Commissioner of South Africa. He was temporarily replaced by , the National Commissioner of Investigations Police of Chile

Investigations Police of Chile (, PDI) are the civilian police of Chile. Founded in 1933, it is one of two Chilean police bodies, along with the law enforcement police: Carabineros de Chile. The PDI is the principal law enforcement arm of the Publ ...

and former vice president for the American Zone, who remained acting president until the appointment of Khoo Boon Hui

Khoo Boon Hui (), born in 1954 in Singapore, is the Senior Deputy Secretary of the Ministry of Home Affairs. Mr Khoo Boon Hui succeeded Jackie Selebi and Arturo Verdugo (acting) as President of INTERPOL, from 2008 to 2012, and he was succeeded b ...

in October 2008.

On 8 November 2012, the 81st General Assembly closed with the election of Deputy Central Director of the French Judicial Police

Judicial police in France are responsible for the investigation of criminal offenses and identification of perpetrators. This is in contrast to Administrative police in France, whose goal is to ensure the maintenance of public order and to preve ...

, Mireille Ballestrazzi

Mireille "Ballen" Ballestrazzi (born 1954 in Orange, France) is a French law enforcement officer and the former President of the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL).

Education

Ballestrazzi earned a Bachelors of Art degree in C ...

, as the first female president of the organization.

In November 2016, Meng Hongwei

Meng Hongwei (; born November 1953) is a former Chinese politician and police officer who was the president of Interpol from 2016 to 2018. He also served as vice-minister of Public Security in China from 2004 to 2018. Meng purportedly resigned i ...

, a politician from the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, sli ...

, was elected president during the 85th Interpol General Assembly, and was to serve in this capacity until 2020. At the end of September 2018, Meng was reported missing during a trip to China, after being "taken away" for questioning by discipline authorities. Chinese police later confirmed that Meng had been arrested on charges of bribery as part of a national anti-corruption campaign. On 7 October 2018, INTERPOL announced that Meng had resigned his post with immediate effect and that the Presidency would be temporarily occupied by Interpol Senior Vice-president (Asia) Kim Jong Yang

Kim Jong Yang (; born 30 October 1961) is a South Korean police officer and former President of Interpol.

Prior to his Interpol career, Kim was Commissioner of Gyeonggi Provincial Police Agency, the law enforcement agency for South Korea's mo ...

of South Korea. On 21 November 2018, Interpol's General Assembly elected Kim to fill the remainder of Meng's term, in a controversial election which saw accusations that the other candidate, Vice President Alexander Prokopchuk

Alexander Vasilyevich Prokopchuk (russian: Александр Васильевич Прокопчук; 18 November 1961) is a Russian employee of the internal affairs agencies, head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation N ...

of Russia, had used Interpol notices to target critics of the Russian government.

On 25 November 2021, Ahmed Naser Al-Raisi

Ahmed Naser Al-Raisi (also romanised as Ahmed Nasser Al-Raisi) is an Emirati military general officer. He currently serves as the 30th president of Interpol and the inspector general of the United Arab Emirates' interior ministry.

Early career ...

, inspector general of the United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia ( The Middle East). It is located at ...

's interior ministry, was elected as president. The election was controversial due to the UAE's human rights record, with concerns being raised by some human rights groups (e.g. Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization, headquartered in New York City, that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. The group pressures governments, policy makers, companies, and individual human ...

) and some MEPs.

Constitution

The role of Interpol is defined by the general provisions of its constitution. Article 2 states that its role is: Article 3 states:Methodology

Contrary to the common idea due to frequent portrayals in popular media, Interpol is not a

Contrary to the common idea due to frequent portrayals in popular media, Interpol is not a supranational law Supranational law is a form of international law, based on the limitation of the rights of sovereign nations between one another. It is distinguished from public international law, because in supranational law, nations explicitly submit their right ...

enforcement agency and has no agents with arresting powers. Instead, it is an international organization that functions as a network of law enforcement agencies from different countries. The organization thus functions as an administrative liaison among the law enforcement agencies of the member countries, providing communications and database assistance, mostly through its central headquarters in Lyon. along with the assistance of smaller local bureaus in each of its member states.

Interpol's databases at the Lyon headquarters can assist law enforcement in fighting international crime. While national agencies have their own extensive crime databases, the information rarely extends beyond one nation's borders. Interpol's databases can track criminals and crime trends around the world, specifically by means of authorized collections of fingerprints and face photos, lists of wanted persons, DNA samples, and travel documents. Interpol's lost and stolen travel document database alone contains more than 12 million records. Officials at the headquarters also analyze this data and release information on crime trends to the member countries.

An encrypted Internet-based worldwide communications network allows Interpol agents and member countries to contact each other at any time. Known as I-24/7, the network offers constant access to Interpol's databases. While the National Central Bureaus are the primary access sites to the network, some member countries have expanded it to key areas such as airports and border access points. Member countries can also access each other's criminal databases via the I-24/7 system.

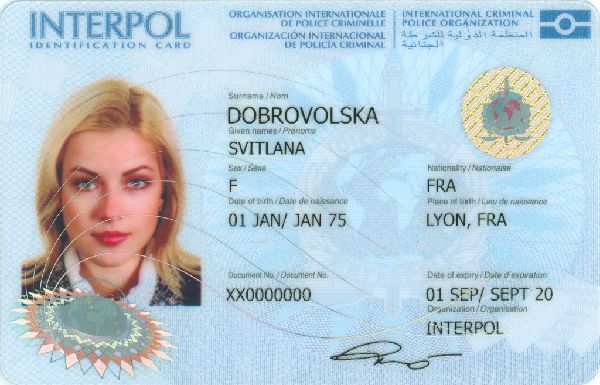

Interpol issued 13,377 Red and 3,165 Yellow Interpol notice

An Interpol notice is an international alert circulated by Interpol to communicate information about crimes, criminals, and threats by police in a member state (or an authorised international entity) to their counterparts around the world. The in ...

s in 2019. , there are currently 62,448 valid Red and 12,234 Yellow notices in circulation.

In the event of an international disaster, terrorist attack, or assassination, Interpol can send an Incident Response Team (IRT). IRTs can offer a range of expertise and database access to assist with victim identification, suspect identification, and the dissemination of information to other nations' law enforcement agencies. In addition, at the request of local authorities, they can act as a central command and logistics operation to coordinate other law enforcement agencies involved in a case. Such teams were deployed eight times in 2013. Interpol began issuing its own travel documents in 2009 with hopes that nations would remove visa requirements for individuals travelling for Interpol business, thereby improving response times. In September 2017, the organization voted to accept Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East J ...

and the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its ca ...

as members.

Finances

In 2019, Interpol's operating income was €142 million ($ million), of which 41 per cent were statutory contributions by member countries, 35 per cent were voluntary cash contributions and 24 per cent were in-kind contributions for the use of equipment, services and buildings. With the goal of enhancing the collaboration between Interpol and the private sector to support Interpol's missions, the Interpol Foundation for a Safer World was created in 2013. Although legally independent of Interpol, the relationship between the two is close enough for Interpol's president to obtain in 2015 the departure ofHSBC

HSBC Holdings plc is a British multinational universal bank and financial services holding company. It is the largest bank in Europe by total assets ahead of BNP Paribas, with US$2.953 trillion as of December 2021. In 2021, HSBC had $10.8 tri ...

CEO from the foundation board after the Swiss Leaks

Swiss Leaks (or SwissLeaks) is the name of a journalistic investigation, released in February 2015, of a giant tax evasion scheme allegedly operated with the knowledge and encouragement of the British multinational bank HSBC via its Swiss subsi ...

allegations.

From 2004 to 2010, Interpol's external auditors

An external auditor performs an audit, in accordance with specific laws or rules, of the financial statements of a company, government entity, other legal entity, or organization, and is independent of the entity being audited. Users of these ent ...

was the French Court of Audit A Court of Audit or Court of Accounts is a Supreme audit institution, i.e. a government institution performing financial and/or legal audit (i.e. Statutory audit or External audit) on the executive branch of power.

See also

*Most of those ins ...

. In November 2010, the Court of Audit was replaced by the Office of the Auditor General of Norway

The Office of the Auditor General of Norway ( no, Riksrevisjonen) is the state auditor of the Government of Norway and directly subordinate of the Parliament of Norway. It is responsible for auditing, monitoring and advising all state economic act ...

for a three-year term with an option for a further three years.

Criticism

Abusive requests for Interpol arrests

Despite its politically neutral stance, some have criticized the agency for its role in arrests that critics contend were politically motivated. In their declaration, adopted in Oslo (2010), Monaco (2012), Istanbul (2013), and Baku (2014), theOSCE Parliamentary Assembly

The Parliamentary Assembly of the OSCE (OSCE PA) is an institution of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. The primary task of the 323-member Assembly is to facilitate inter-parliamentary dialogue, an important aspect of the o ...

(PACE) criticized some OSCE member States for their abuse of mechanisms of the international investigation and urged them to support the reform of Interpol in order to avoid politically motivated prosecution

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the case in a criminal tri ...

. The resolution of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe of 31 January 2014 criticizes the mechanisms of operation of the Commission for the Control of Interpol's files, in particular, non-adversarial procedures and unjust decisions. In 2014, PACE adopted a decision to thoroughly analyse the problem of the abuse of Interpol and to compile a special report on this matter. In May 2015, within the framework of the preparation of the report, the PACE Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights organized a hearing, during which both representatives of NGOs and Interpol had the opportunity to speak. According to Freedomhouse

Freedom House is a non-profit, majority U.S. government funded organization in Washington, D.C., that conducts research and advocacy on democracy, political freedom, and human rights. Freedom House was founded in October 1941, and Wendell Wil ...

, Russia is responsible for 38% of Interpol's public Red Notices. There currently are "approximately 66,370 valid Red Notices, of which some 7,669 are public."

Refugees who are included in the list of Interpol can be arrested when crossing the border. In the year 2008, the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and to assist in their voluntary repatriation, local integrati ...

pointed to the problem of arrests of refugees on the request of INTERPOL in connection with politically motivated charges.

In 2021, Turkey, China, the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Russia, and Venezuela were accused of abusing Interpol by using it to target political opponents. Despite Interpol's policy that forbids countries from using the organization to pursue opponents, autocrats have been increasingly abusing the constitution of Interpol. China used Interpol against the Uyghurs

The Uyghurs; ; ; ; zh, s=, t=, p=Wéiwú'ěr, IPA: ( ), alternatively spelled Uighurs, Uygurs or Uigurs, are a Turkic ethnic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the general region of Central and East Asia. The Uyghur ...

, where the government issued a Red Notice against activists and other members of the ethnic minority group

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history ...

living abroad. Since 1997, 1,546 cases from 28 countries of detention and deportation of the Uyghurs were recorded. In the case of Turkey, Interpol had to turn down 800 requests, including one for NBA

The National Basketball Association (NBA) is a professional basketball league in North America. The league is composed of 30 teams (29 in the United States and 1 in Canada) and is one of the major professional sports leagues in the United ...

basketball player Enes Kanter Freedom

Enes Kanter Freedom (; born Enes Kanter; May 20, 1992) is a professional basketball player who last played for the Boston Celtics of the National Basketball Association (NBA). Born in Switzerland to Turkish parents, he was raised in Turkey and m ...

. The UAE was also accused as one of the countries attempting to buy influence in Interpol. Using the Interpol Foundation for a Safer World, the Arab nation gave donations of $54 million. The amount was estimated as equal to the statutory contributions together made by the rest 194 members. It was asserted that the Emirates' growing influence over Interpol gave it the opportunity to host the General Assembly in 2018 and in 2020 (that was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identified ...

).

World

Organizations such asDetained in Dubai

Detained in Dubai is a London-based organisation founded in 2008 by Radha Stirling, which states its aim is to help foreigners abroad.

Detained in Dubai was founded when Cat Le-Huy, a colleague of Stirling's from Endemol, was arrested in the UAE ...

, Open Dialog Foundation

The Open Dialogue Foundation (ODF), formerly known as the Open Dialog Foundation, (Polish: ''Fundacja Otwarty Dialog''), is an international non-governmental organization, founded in 2009 in Poland and currently headquartered in Brussels, Belgiu ...

, Fair Trials International

Fair Trials is a UK-registered non-governmental organization which works for fair trials according to international standards of justice and the right to a fair trial, identifying where criminal justice is failing, alerting the world to the prob ...

, Centre for Peace Studies

Center or centre may refer to:

Mathematics

*Center (geometry), the middle of an object

* Center (algebra), used in various contexts

** Center (group theory)

** Center (ring theory)

* Graph center, the set of all vertices of minimum eccentricity ...

, and International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Inc. (ICIJ), is an independent global network of 280 investigative journalists and over 140 media organizations spanning more than 100 countries. It is based in Washington, D.C. with ...

, indicate that non-democratic states use Interpol to harass opposition politicians, journalists, human rights activists, and businessmen. The countries accused of abusing the agency include China, Russia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Iran, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Venezuela, and Tunisia.

The Open Dialog Foundation

The Open Dialogue Foundation (ODF), formerly known as the Open Dialog Foundation, (Polish: ''Fundacja Otwarty Dialog''), is an international non-governmental organization, founded in 2009 in Poland and currently headquartered in Brussels, Belgiu ...

's report analysed 44 high-profile political cases which went through the Interpol system. A number of persons who have been granted refugee status in the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been ...

(EU) and the U.S.—including Russian businessman Andrey Borodin

Andrey Fridrikhovich Borodin (russian: Андре́й Фри́дрихович Бороди́н; born Moscow, 24 May 1967) is a Russian financial expert, economist and businessman who until 2011 was President of Bank of Moscow. He and his first d ...

, Chechen Arbi Bugaev, Kazakh opposition politician Mukhtar Ablyazov

Mukhtar Qabyluly Ablyazov ( kk, Мұхтар Қабылұлы Әблязов, ''Muhtar Qabyluly Ábliazov''; born 16 May 1963) is a Kazakh businessman and political activist who served as chairman of Bank Turan Alem (BTA Bank), and is a co-fou ...

and his associate Artur Trofimov, and Sri Lankan journalist Chandima Withana —continue to remain on the public INTERPOL list. Some of the refugees remain on the list even after courts have refused to extradite them to a non-democratic state (for example, Pavel Zabelin, a witness in the case of Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Mikhail Borisovich Khodorkovsky (russian: link=no, Михаил Борисович Ходорковский, ; born 26 June 1963), sometimes known by his initials MBK, is an exiled Russian businessman and opposition activist, now residing in ...

, and Alexandr Pavlov, former security chief of the Kazakh oppositionist Ablyazov). Another case is Manuel Rosales

Manuel Antonio Rosales Guerrero (born December 12, 1952, in Santa Bárbara del Zulia) is a Venezuelan educator and politician, current governor of Zulia, Venezuela's most populated state. He was the most prominent opposition candidate in the ...

, a politician who opposed Hugo Chavez

Hugo or HUGO may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Hugo'' (film), a 2011 film directed by Martin Scorsese

* Hugo Award, a science fiction and fantasy award named after Hugo Gernsback

* Hugo (franchise), a children's media franchise based on a ...

and fled to Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

in 2009 and was subject to a red alert on charges of corruption for two weeks. Interpol deleted the request for prosecution immediately. Interpol has also been criticized for mistaking people on yellow alerts. One case was Alondra Díaz-Nuñez, who in April 2015 was apprehended in Guanajuato City

Guanajuato () is a city and municipal seat of the municipality of Guanajuato in central Mexico and the capital of the state of the same name. It is part of the macroregion of the Bajío. It is in a narrow valley, which makes its streets narrow ...

, Mexico being mistaken for . Interpol came under heavy criticism from Mexican news and media for helping out Policia Federal Ministerial

The Federal Ministerial Police (in Spanish: ''Policía Federal Ministerial'', PFM) is a Mexican federal agency tasked with fighting corruption and organized crime, through an executive order by President Felipe Calderón. The agency is directed ...

, Mexican Federal Police

The Federal Police ( es, Policía Federal, PF), formerly known as the (Federal Preventive Police) and sometimes referred to in the U.S. as "Federales", was a Mexican national police force formed in 1999 and folded into the National Guard in 2019. ...

, and the U.S. Embassy and Consulate in Mexico, in what was believed to be a kidnapping

In criminal law, kidnapping is the unlawful confinement of a person against their will, often including transportation/ asportation. The asportation and abduction element is typically but not necessarily conducted by means of force or fear: the ...

.

Eastern Europe

The 2013 PACE's Istanbul Declaration of the OSCE cited specific cases of such prosecution, including those of the Russian activist Petr Silaev, financier William Browder, businessman Ilya Katsnelson, Belarusian politicianAles Michalevic

Ales (Alaksiej) Anatoljevich Michalevic ( be, Але́сь Мiхале́вiч, Aleś Michalevič, Ales Mikhalevich, born 15 May 1975 in Minsk, Byelorussian SSR) is a Belarusian public figure and politician, candidate in the 2010 Belarusian presid ...

, and Ukrainian politician Bohdan Danylyshyn.

On 25 July 2014, despite Interpol's Constitution prohibiting them from undertaking any intervention or activities of a political or military nature, the Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary leader Dmytro Yarosh

Dmytro Anatoliyovych Yarosh ( uk, Дмитро Анатолійович Я́рош; born 30 September 1971) is a Ukrainian activist, politician, nationalist and military commander who is the main commander of the Right Sector's Ukrainian Vo ...

was placed on Interpol's international wanted list at the request of Russian authorities, which made him the only person wanted internationally after the beginning of the conflict between Ukraine and Russia in 2014. For a long time, Interpol refused to place former President of Ukraine

The president of Ukraine ( uk, Президент України, Prezydent Ukrainy) is the head of state of Ukraine. The president represents the nation in international relations, administers the foreign political activity of the state, condu ...

Viktor Yanukovych

Viktor Fedorovych Yanukovych ( uk, Віктор Федорович Янукович, ; ; born 9 July 1950) is a former politician who served as the fourth president of Ukraine from 2010 until he was removed from office in the Revolution of D ...

on the wanted list as a suspect by the new Ukrainian government

The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine ( uk, Кабінет Міністрів України, translit=Kabinet Ministriv Ukrainy; shortened to CabMin), commonly referred to as the Government of Ukraine ( uk, Уряд України, ''Uriad Ukrai ...

for the mass killing of protesters during Euromaidan

Euromaidan (; uk, Євромайдан, translit=Yevromaidan, lit=Euro Square, ), or the Maidan Uprising, was a wave of Political demonstration, demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine, which began on 21 November 2013 with large protes ...

. Yanukovych was eventually placed on the wanted list on 12 January 2015. However, on 16 July 2015, after an intervention of Joseph Hage Aaronson, the British law firm hired by Yanukovych, the international arrest warrant against the former president of Ukraine was suspended pending further review. In December 2014, the Security Service of Ukraine

The Security Service of Ukraine ( uk, Служба безпеки України, translit=Sluzhba bezpeky Ukrainy}) or SBU ( uk, СБУ, link=no) is the law enforcement authority and main intelligence and security agency of the Ukrainia ...

(SBU) liquidated a sabotage and reconnaissance group that was led by a former agent of the Ukrainian Bureau of INTERPOL that also has family relations in the Ukrainian counter-intelligence agencies. In 2014, Russia made attempts to place Ukrainian politician Ihor Kolomoyskyi

Ihor Valeriyovych Kolomoyskyi ( uk, Ігор Валерійович Коломойський, translit=Ihor Valereriyovych Kolomoyskyi; he, איגור קולומויסקי; born 13 February 1963) is a Ukrainian-born billionaire, business magna ...

and Ukrainian civic activist Pavel Ushevets

Pavel ( Bulgarian, Russian, Serbian and Macedonian: Павел, Czech, Slovene, Romanian: Pavel, Polish: Paweł, Ukrainian: Павло, Pavlo) is a male given name. It is a Slavic cognate of the name Paul (derived from the Greek Pavlos). Pav ...

, subject to criminal persecution in Russia following his pro-Ukrainian art performance in Moscow, on the Interpol wanted list.

Middle East

According to a report by theStockholm Center for Freedom

The Stockholm Center for Freedom (SCF) is an advocacy organization founded in 2017 by Turkish journalists allegedly linked to the Gülen movement.persecution tools against critics and opponents. The harassment campaign targeted foreign companies as well. Syrian-Kurd

INTERPOL Foundation for a Safer World

In The Encyclopedia of Crime and Punishment, edited by Wesley G. Jennings. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Pp. 17–25 in Understanding and Responding to Terrorism, edited by H. Durmaz, B. Sevinc, A.S. Yayla, and S. Ekici. Amsterdam: IOS Press. {{Coord, 45.7822, N, 4.8484, E, region:FR-ARA_type:landmark, display=title Organizations established in 1923 International organizations based in France 6th arrondissement of Lyon United Nations General Assembly observers 1923 establishments in Austria

Salih Muslim

Salih Muslim Muhammad (Kurmanji ku, Salih Muslim Mihemed, ar, صالح مسلم محمد, Ṣāliḥ Muslim Muḥammad) is the co-chairman of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the main party of the Autonomous Administration of North and East S ...

was briefly detained at Turkey's request on 25 February 2018 in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

, the capital of the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. Th ...

, but was released 2 days later, drawing angry protests from Turkey. On 17 March 2018, the Czech authorities dismissed Turkey's request as lacking merit.

After a senior UAE government official, Ahmed Naser Al-Raisi became the President, Interpol ignored an injunction by the European court of human rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR or ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights. The court hears applications alleging that a ...

(ECHR), and cooperated with Serbian authorities to extradite a Bahraini activist. Ahmed Jaafar Mohamed Ali was extradited to Bahrain in a charter aircraft of Royal Jet

Royal Jet LLC, typically referred to as RoyalJet, is an airline based in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. It is a charter operator aimed at the luxury market between the UAE and Europe. RoyalJet has operating bases at Abu Dhabi International Ai ...

, a private Emirati airline headed by an Abu Dhabi royal family member. Critics raised concerns that it was just first example of how "red lines will be crossed" under the presidency of Al-Raisi. Besides, a warning was raised that after its decision, Interpol will be complicit in any abuse that Ali will face. In 2021 it was reported that Ahmed Naser had also allegedly tortured a number of people in the UAE before.

Appeals and requests withdrawals

The procedure for filing an appeal with Interpol is a long and complex one. For example, the Venezuelan journalistPatricia Poleo

Patricia Poleo (born in Caracas) is a Venezuelan journalist and the winner of the King of Spain Journalism Award for her investigation into the whereabouts of Peruvian dictator Alberto Fujimori's right-hand man, Vladimiro Montesinos. She is the ...

and a colleague of Kazakh activist Ablyazov, and Tatiana Paraskevich, who were granted refugee status, sought to overturn the politically motivated request for as long as one and a half years, and six months, respectively.

Interpol has previously recognized some requests to include persons on the wanted list as politically motivated, e.g., Indonesian activist Benny Wenda

Benny Wenda is a West Papuan independence leader and Chairman of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP). He is an international lobbyist for the independence of West Papua from Indonesia. He lives in exile in the United Kingdom. ...

, Georgian politician Givi Targamadze

Givi Targamadze (born 23 July 1968) is a Georgian politician in the United National Movement. An ally of Mikhail Saakashvili, Targamadze was one of the leaders of the United National Movement and the 2003 Rose Revolution. He served as Defense ...

, ex-president of Georgia Mikheil Saakashvili

Mikheil Saakashvili ( ka, მიხეილ სააკაშვილი ; uk, Міхеіл Саакашвілі ; born 21 December 1967) is a Georgian and Ukrainian politician and jurist.

, ex-mayor of Maracaibo

)

, motto = "''Muy noble y leal''"(English: "Very noble and loyal")

, anthem =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_alt = ...

and 2006 Venezuelan presidential election

Presidential elections were held in Venezuela on 3 December 2006 to elect a president for a six-year term to begin on 10 January 2007. The contest was primarily between incumbent President Hugo Chávez, and Zulia Governor Manuel Rosales of the op ...

candidate Manuel Rosales

Manuel Antonio Rosales Guerrero (born December 12, 1952, in Santa Bárbara del Zulia) is a Venezuelan educator and politician, current governor of Zulia, Venezuela's most populated state. He was the most prominent opposition candidate in the ...

and ex-president of Honduras Manuel Zelaya Rosales

José Manuel Zelaya Rosales (born 20 September 1952)Encyclopædia BritannicaManuel Zelaya/ref> is a Honduran politician who was President of Honduras from 27 January 2006 until 28 June 2009, and who since January 2022 serves as the first Firs ...

; these persons have subsequently been removed. However, in most cases, Interpol removes a Red Notice against refugees only after an authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

state closes a criminal case or declares amnesty

Amnesty (from the Ancient Greek ἀμνηστία, ''amnestia'', "forgetfulness, passing over") is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power offic ...

(for example, the cases of Russian activists and political refugees Petr Silaev, Denis Solopov, and Aleksey Makarov, as well as the Turkish sociologist and feminist Pinar Selek

Pinar may refer to:

* Pınar, Turkish feminine given name

* Píñar, municipality located in the province of Granada, Spain

* Pinar del Río, a city of Cuba

* Pinar del Río Province, a province of Cuba

* Pinar, Albania, village in Tirana County, ...

).

Diplomacy

In 2016,Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northe ...

criticised Interpol for turning down their application to join the General Assembly as an observer. The United States supported Taiwan's participation, and the US Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

passed legislation directing the Secretary of State to develop a strategy to obtain observer status for Taiwan.

The election of Meng Hongwei, a Chinese person, as president and Alexander Prokopchuk

Alexander Vasilyevich Prokopchuk (russian: Александр Васильевич Прокопчук; 18 November 1961) is a Russian employee of the internal affairs agencies, head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation N ...

, a Russian, as vice president of Interpol for Europe drew criticism in Anglo media and raised fears of Interpol accepting politically motivated requests from China and Russia.

Business

In 2013, Interpol was criticised over its multimillion-dollar deals with such private sector bodies as FIFA,Philip Morris Phil(l)ip or Phil Morris may refer to:

Companies

*Altria, a conglomerate company previously known as Philip Morris Companies Inc., named after the tobacconist

**Philip Morris USA, a tobacco company wholly owned by Altria Group

**Philip Morris Inter ...

, and the pharmaceutical industry. The criticism was mainly about the lack of transparency and potential conflicts of interest, such as Codentify Codentify is the name of a product serialization system developed and patented back in 2005 by Philip Morris International (PMI) for tobacco product authenticity, production volume verification and supply chain control. In the production process, e ...

. After the 2015 FIFA scandal, the organization has severed ties with all the private-sector bodies that evoked such criticism, and has adopted a new and transparent financing framework.

Leadership

After the disappearance ofMeng Hongwei

Meng Hongwei (; born November 1953) is a former Chinese politician and police officer who was the president of Interpol from 2016 to 2018. He also served as vice-minister of Public Security in China from 2004 to 2018. Meng purportedly resigned i ...

, four American senators accused his presumptive successor, Alexander Prokopchuk

Alexander Vasilyevich Prokopchuk (russian: Александр Васильевич Прокопчук; 18 November 1961) is a Russian employee of the internal affairs agencies, head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation N ...

, of abusing Red Notices, likening his election to "putting a fox in charge of the henhouse". A statement posted by the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union

All-Ukrainian Association of Public Organizations Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union (UHHRU) was founded by 15 public human rights organizations on 1 April 2004. UHHRU is a non-profit and non-partisan organization.

Statutory mission

Realizatio ...

and signed by other NGOs raised concerns about his ability to use his Interpol position to silence Russia's critics. Russian politicians criticized the U.S. accusation as politically motivated interference.

On 1 October 2020, the delegate of Interpol's executive committee for Asia, United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia ( The Middle East). It is located at ...

security chief, Ahmed Naser al-Raisi

Ahmed Naser Al-Raisi (also romanised as Ahmed Nasser Al-Raisi) is an Emirati military general officer. He currently serves as the 30th president of Interpol and the inspector general of the United Arab Emirates' interior ministry.

Early career ...

, accused of serious human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

abuses in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

, including against British citizens, was seeking to become the new head of Interpol. Interpol was warned that it could lose credibility if al-Raisi was elected as the president. When al-Raisi was in charge of security and police forces in the UAE, a Durham University PHD student, Matthew Hedges was held for almost six months in solitary confinement, after being arrested in Dubai

Dubai (, ; ar, دبي, translit=Dubayy, , ) is the most populous city in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the capital of the Emirate of Dubai, the most populated of the 7 emirates of the United Arab Emirates.The Government and Politics ...

on spying charges. He was also fed a cocktail of drugs during his imprisonment. Another Briton and a football fan, Ali Ahmad was imprisoned in the UAE for wearing a Qatar

Qatar (, ; ar, قطر, Qaṭar ; local vernacular pronunciation: ), officially the State of Qatar,) is a country in Western Asia. It occupies the Qatar Peninsula on the northeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in the Middle East; it ...

shirt to a match. He was stabbed with a pocket knife in his chest and arms, struck in the mouth causing him to lose a front tooth, suffocated with a plastic bag and had his clothing set on fire by arresting officers.

In an April 2021 report written by the ex-UK DPP, Sir David Calvert-Smith in assistance from IHR Advisors, questions were raised over the influence of the UAE over Interpol, calling out UAE general bidding for Interpol chief as unfit for the role. The report stated that the Emirati general, Ahmed Naser Al-Raisi who bid for the role of Interpol chief was unsuitable for the position following links to human rights abuses. The allegations were made based on several facts drawn by Sir David, including the influential donation worth $50 million made by the UAE and accepted by Interpol in 2017 through an entirely UAE-funded organization based in Geneva, Interpol Foundation for a Safer World.

A French human rights lawyer, William Bourdon

William Bourdon (born 1956) is a French lawyer of the Paris Bar Association who practices criminal law, particularly specializing in white-collar crime, communications law and human rights. He particularly specializes in defending the victims o ...

filed an official complaint on behalf of the Gulf Centre for Human Rights or GCHR against Maj. Gen. Ahmed Naser Al-Raisi in connection with the unauthorized arrest and torture of a GCHR Board member and human rights activist, Ahmed Mansoor. The complaint lodged with the Prosecutor's Office in Paris on 7 June 2021, was based on the universal jurisdiction concept, seeking to bring Al-Raisi to justice while he was in France in 2021 for his bid to seek the presidency of Interpol.

In June 2021, 35 French Parliamentarians, Members of Parliament and Senators, including from the majority and the opposition, urged President Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Macron (; born 21 December 1977) is a French politician who has served as President of France since 2017 French presidential election, 2017. ''Ex officio'', he is also one of the two Co-Princes of Andorra. Prior to his presidency, M ...

to oppose the candidacy of the UAE's General Ahmed Nasser Al-Raisi, citing the accusations of torture against him. It was the second appeal by the deputy of the Rhône, Hubert Julien-Laferrière

Hubert Julien-Laferrière (born 27 February 1966) is a French economist and politician. As member of La République En Marche! (REM), he was elected to the National Assembly on 18 June 2017, representing the department of Rhône.

Julien-Laferri ...

, who had first written to Macron earlier in 2021. He questioned how a profile like Al-Raisi's, who was responsible for the torture of political opponent Ahmed Mansoor

Ahmed Mansoor Al Shehhi is an Emirati blogger, human rights and reform activist arrested in 2011 for defamation and insults to the heads of state and tried in the UAE Five trial. He was pardoned by UAE's president Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nah ...

and of a British academic Matthew Hedges

In May 2018, Matthew Hedges, a British doctoral student who was in the United Arab Emirates for a two-week research trip, was arrested at Dubai International Airport on suspicion of spying on behalf of the British government. In November 2018, ...

, can become the president of a most respectable institution.

In August 2021, reports revealed that the UAE was promoting its candidate, Ahmed Naser Al-Raisi

Ahmed Naser Al-Raisi (also romanised as Ahmed Nasser Al-Raisi) is an Emirati military general officer. He currently serves as the 30th president of Interpol and the inspector general of the United Arab Emirates' interior ministry.

Early career ...

, for the Interpol presidency. Viewed as an “international pariah”, Al-Raisi was receiving increasing condemnation for his involvement in the detention and torture of Ahmed Mansoor

Ahmed Mansoor Al Shehhi is an Emirati blogger, human rights and reform activist arrested in 2011 for defamation and insults to the heads of state and tried in the UAE Five trial. He was pardoned by UAE's president Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nah ...

, Mathhew Hedges, and Ali Issa Ahmad. Considering that, the Emirates initiated a plan to promote Raisi by organizing his trips to Interpol member countries to gain support.

While the UAE was arranging trips for al-Raisi to Interpol's member countries, opposition against the Emirati candidate amplified. A number of German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

MPs signed a petition to express “deep concern” and reject the candidacy of al-Raisi for the post of Interpol director. British lawyer of Matthew Hedges and Ali Ahmad, Rodney Dixon submitted a complaint and urged the Swedish authorities to arrest al-Raisi upon his arrival in Sweden. The two Britons also raised a similar request to arrest al-Raisi with the Norwegian police authorities. Both Sweden and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

apply jurisdiction that allows them to open investigations of crime, irrespective of a person's nationality or the origin country of the crime.

In October 2021, the Emirati candidate for Interpol presidency, Naser Al-Raisi had to face further opposition, as the lawyers submitted a complaint to the French Prosecutor in Paris. The claims cited Al-Raisi's role in the unlawful detention and torture of Ali Issa Ahmad and Matthew Hedges. Filed under the principle of universal jurisdiction, the complaint gave French officials the authority to investigate and arrest foreign nationals. As Raisi is not a head of state, French authorities had all the rights to arrest and question him on entering the French territory.

As the General Assembly was approaching, the opposition was rising. In November 2021, a Turkish lawyer Gulden Sonmez filed a criminal complaint against Al-Raisi's nomination in Turkey, where the vote was to take place. Sonmez said its the Emirates’ attempt to cover its human rights records and to launder its reputation. Besides, Hedges and Ahmad were also expected to file a lawsuit in Turkey against Al-Raisi, ahead of the General Assembly.

On 20 December 2021, The Heritage Foundation

The Heritage Foundation (abbreviated to Heritage) is an American conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C. that is primarily geared toward public policy. The foundation took a leading role in the conservative movement during the preside ...

called out Interpol presidency, Secretary General Jürgen Stock

Jürgen Stock (born October 4, 1959) is a German police officer and academic. He has served as secretary general of Interpol since November 7, 2014.

Biography

Stock was born on October 4, 1959, in Wetzlar, Germany. He joined the Kriminalpolizei i ...

, for failing to properly vet the police cooperation requests of member nations like Turkey and for the election to presidency of United Arab Emirates’ major general Ahmed Naser al-Raisi, despite credible accusations of torturing detainees including British national, Matthew Hedges

In May 2018, Matthew Hedges, a British doctoral student who was in the United Arab Emirates for a two-week research trip, was arrested at Dubai International Airport on suspicion of spying on behalf of the British government. In November 2018, ...

. The think tank raised questions on the choices and support of reforms by Interpol for electing member states and members who have a poor record. Stock assured the selection of Raisi asserting that the latter would continue to represent his homeland and not Interpol.

Reform

From 1 to 3 July 2015, Interpol organized a session of the Working Group on the Processing of Information, which was formed specifically in order to verify the mechanisms of information processing. The Working Group heard the recommendations of civil society as regards the reform of the international investigation system and promised to take them into account, in light of possible obstruction or refusal to file crime reports nationally. The Open Dialog Foundation, a human rights organization, recommended that Interpol, in particular: create a mechanism for the protection of rights of people having international refugee status; initiate closer cooperation of the Commission for the Control of Files with human rights NGOs and experts on asylum and extradition; enforce sanctions for violations of Interpol's rules; strengthen cooperation with NGOs, the UN, OSCE, the PACE, and the European Parliament.Fair Trials International

Fair Trials is a UK-registered non-governmental organization which works for fair trials according to international standards of justice and the right to a fair trial, identifying where criminal justice is failing, alerting the world to the prob ...

proposed to create effective remedies for individuals who are wanted under a Red Notice on unfair charges; to penalize nations which frequently abuse the Interpol system; to ensure more transparency of Interpol's work.

The Centre for Peace Studies

Center or centre may refer to:

Mathematics

*Center (geometry), the middle of an object

* Center (algebra), used in various contexts

** Center (group theory)

** Center (ring theory)

* Graph center, the set of all vertices of minimum eccentricity ...

also created recommendations for Interpol, in particular, to delete Red Notices and Diffusions for people who were granted refugee status according to 1951 Refugee Convention

The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, also known as the 1951 Refugee Convention or the Geneva Convention of 28 July 1951, is a United Nations multilateral treaty that defines who a refugee is, and sets out the rights of individuals ...

issued by their countries of origin, and to establish an independent body to review Red Notices on a regular basis.

Emblem

The current emblem of Interpol was adopted in 1950 and includes the following elements: * the globe indicates worldwide activity * the olive branches represent peace * the sword represents police action * the scales signify justice * the acronyms "OIPC" and "ICPO", representing the full name of the organization in both French and English, respectively.Membership

Members

Interpol currently has 195 member countries:Subnational-bureaus

Threemember states of the United Nations

The United Nations member states are the sovereign states that are members of the United Nations (UN) and have equal representation in the United Nations General Assembly, UN General Assembly. The UN is the world's largest international o ...

and three partially-recognized states are currently not members of Interpol: North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and ...

, Palau

Palau,, officially the Republic of Palau and historically ''Belau'', ''Palaos'' or ''Pelew'', is an island country and microstate in the western Pacific. The nation has approximately 340 islands and connects the western chain of the Ca ...

, and Tuvalu

Tuvalu ( or ; formerly known as the Ellice Islands) is an island country and microstate in the Polynesian subregion of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. Its islands are situated about midway between Hawaii and Australia. They lie east-northea ...

, as well as Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a partially recognised state in Southeast Eur ...

, Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northe ...

and Western Sahara

Western Sahara ( '; ; ) is a disputed territory on the northwest coast and in the Maghreb region of North and West Africa. About 20% of the territory is controlled by the self-proclaimed Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), while ...

.

Offices

In addition to its General Secretariat headquarters in Lyon, Interpol maintains seven regional bureaus and three special representative offices: *Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the Capital city, capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata ...

, Argentina

* Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, Belgium (special representative office to the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been ...

)

* Yaoundé

Yaoundé (; , ) is the capital of Cameroon and, with a population of more than 2.8 million, the second-largest city in the country after the port city Douala. It lies in the Centre Region of the nation at an elevation of about 750 metres (2,50 ...

, Cameroon

* Abidjan

Abidjan ( , ; N'Ko script, N’ko: ߊߓߌߖߊ߲߬) is the economic capital of the Ivory Coast. As of the Demographics of Ivory Coast, 2021 census, Abidjan's population was 6.3 million, which is 21.5 percent of overall population of the country, ...

, Côte d'Ivoire

* San Salvador, El Salvador

* Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (; am, አዲስ አበባ, , new flower ; also known as , lit. "natural spring" in Oromo), is the capital and largest city of Ethiopia. It is also served as major administrative center of the Oromia Region. In the 2007 census, ...

, Ethiopia (special representative office to the African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of member states of the African Union, 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling fo ...

)

* Nairobi

Nairobi ( ) is the capital and largest city of Kenya. The name is derived from the Maasai phrase ''Enkare Nairobi'', which translates to "place of cool waters", a reference to the Nairobi River which flows through the city. The city prope ...

, Kenya

* Bangkok

Bangkok, officially known in Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon and colloquially as Krung Thep, is the capital and most populous city of Thailand. The city occupies in the Chao Phraya River delta in central Thailand and has an estimated populatio ...

, Thailand

* New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

, United States (special representative office to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

)

* Harare

Harare (; formerly Salisbury ) is the Capital city, capital and most populous city of Zimbabwe. The city proper has an area of 940 km2 (371 mi2) and a population of 2.12 million in the 2012 census and an estimated 3.12 million in its ...

, Zimbabwe

Interpol's Command and Coordination Centres offer a 24-hour point of contact for national police forces seeking urgent information or facing a crisis. The original is in Lyon with a second in Buenos Aires added in September 2011. A third was opened in Singapore in September 2014.

Interpol opened a Special Representative Office to the UN in New York City in 2004 and to the EU in Brussels in 2009.

The organization has constructed the Interpol Global Complex for Innovation (IGCI) in Singapore to act as its research and development

Research and development (R&D or R+D), known in Europe as research and technological development (RTD), is the set of innovative activities undertaken by corporations or governments in developing new services or products, and improving existi ...

facility, and a place of cooperation on digital crimes investigations. It was officially opened in April 2015, but had already become active beforehand. Most notably, a worldwide takedown of the SIMDA botnet infrastructure was coordinated and executed from IGCI's Cyber Fusion Centre in the weeks before the opening, as was revealed at the launch event.

Secretaries-general and presidents

Secretary General

Presidents

See also

*Cybercrime

A cybercrime is a crime that involves a computer or a computer network.Moore, R. (2005) "Cyber crime: Investigating High-Technology Computer Crime," Cleveland, Mississippi: Anderson Publishing. The computer may have been used in committing t ...

* Europol, a similar EU-wide organization.

* Federal Investigation Agency

The Federal Investigation Agency ( ur, ; reporting name: FIA) is a border control, criminal investigation, counter-intelligence and security agency under the control of the Interior Secretary of Pakistan, tasked with investigative jurisdic ...

* Intelligence assessment

Intelligence assessment, or simply intel, is the development of behavior forecasts or recommended courses of action to the leadership of an organisation, based on wide ranges of available overt and covert information (intelligence). Assessments d ...

* International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court (ICC or ICCt) is an intergovernmental organization and international tribunal seated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is the first and only permanent international court with jurisdiction to prosecute individua ...

* Interpol notice

An Interpol notice is an international alert circulated by Interpol to communicate information about crimes, criminals, and threats by police in a member state (or an authorised international entity) to their counterparts around the world. The in ...

* Interpol Terrorism Watch List Interpol launched the Interpol Terrorism Watch List on 11 April 2002 for access by Interpol offices and authorized police agencies in its 184 member countries, during the 17th Interpol Regional Conference for the Americas in Mexico City. Following t ...

* Interpol Travel Document

An Interpol Travel Document is a travel document issued to Interpol officers for travel to Interpol member countries. They are intended to reduce response times for personnel deployed to assist with transnational criminal investigations, major eve ...

* InterPortPolice

The INTERPORTPOLICE (also InterPortPolice) is the international organization of law enforcement agencies established to combat serious transnational crimes, such as terrorism and drug smuggling an various transportation hubs, such as seaports ...

* UN Police

The United Nations Police (UNPOL) is an integral part of the United Nations peace operations. Currently, about 11 530 UN Police officers from over 90 countries are deployed in 11 UN peacekeeping operations and 6 Special PoliticaMissions The ...

Notes

References

Further reading

*External links

* *INTERPOL Foundation for a Safer World

In The Encyclopedia of Crime and Punishment, edited by Wesley G. Jennings. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Pp. 17–25 in Understanding and Responding to Terrorism, edited by H. Durmaz, B. Sevinc, A.S. Yayla, and S. Ekici. Amsterdam: IOS Press. {{Coord, 45.7822, N, 4.8484, E, region:FR-ARA_type:landmark, display=title Organizations established in 1923 International organizations based in France 6th arrondissement of Lyon United Nations General Assembly observers 1923 establishments in Austria