International Brigades on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the

Using foreign

Using foreign

The

The

After the failed assault on the Jarama, the Nationalists attempted another assault on Madrid, this time from the northeast. The objective was the town of

After the failed assault on the Jarama, the Nationalists attempted another assault on Madrid, this time from the northeast. The objective was the town of

In October 1938, at the height of the

In October 1938, at the height of the

*

*

After the Civil War was eventually won by the Nationalists, the brigaders were initially on the "wrong side" of history, especially as most of their home countries had right-wing governments (in France, for instance, the

After the Civil War was eventually won by the Nationalists, the brigaders were initially on the "wrong side" of history, especially as most of their home countries had right-wing governments (in France, for instance, the

In line with the 1920 legislation, Polish citizens who volunteered to the IB were automatically stripped of citizenship as individuals who without formal approval served in foreign armed forces. Following republican defeat the combatants recruited in France and Belgium returned there. Among the others some served in pro-Communist partisan units in the German-occupied Poland and some made it to the USSR and served in the pro-Communist Polish army raised there.

In the Communist Poland the IB combatants – referred to as "Dąbrowszczacy" - were granted veteran rights, but their fate differed depending upon political circumstances. Following some early exaltation in 1945-1949 they were later approached somewhat cautiously. There were cases of assuming high positions in administration and especially in security, but there were also cases of deposition, arrest and prison on trumped-up charges of political conspiracy; these were released in the mid-1950s.

Though from the onset Polish engagement in IB was hailed as "working class taking to arms against Fascism", the most intense idolization took place between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s, with a spate of publications, schools and streets named after "Dąbrowszczacy". However, anti-Semitic turn of the late 1960s again produced de-emphasizing of IB volunteers, many of whom left Poland. Until the end of Communist rule the IB episode was duly acknowledged, but propaganda related was a far cry from veneration reserved for wartime Communist partisans or the USSR-raised Polish army. Despite some efforts on part of IB combatants, no monument has been erected.

After 1989 it was unclear whether Dąbrowszczacy were furtherly entitled to veteran privileges; the issue generated political debates until they became pointless, as almost all IB combatants had passed away. Another question was about homage references, existent in public space. A state-run institution Institute of National Remembrance, IPN declared Polish IB combatants in service of the Stalinist regime and related homage references subject to de-communisation legislation. However, efficiency of purges of public space differs depending upon local political configuration and occasionally there is heated public debate ensuing. Until today the role of Polish IB combatants remains a highly divisive topic; for some they are traitors and for some they are heroes.

In line with the 1920 legislation, Polish citizens who volunteered to the IB were automatically stripped of citizenship as individuals who without formal approval served in foreign armed forces. Following republican defeat the combatants recruited in France and Belgium returned there. Among the others some served in pro-Communist partisan units in the German-occupied Poland and some made it to the USSR and served in the pro-Communist Polish army raised there.

In the Communist Poland the IB combatants – referred to as "Dąbrowszczacy" - were granted veteran rights, but their fate differed depending upon political circumstances. Following some early exaltation in 1945-1949 they were later approached somewhat cautiously. There were cases of assuming high positions in administration and especially in security, but there were also cases of deposition, arrest and prison on trumped-up charges of political conspiracy; these were released in the mid-1950s.

Though from the onset Polish engagement in IB was hailed as "working class taking to arms against Fascism", the most intense idolization took place between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s, with a spate of publications, schools and streets named after "Dąbrowszczacy". However, anti-Semitic turn of the late 1960s again produced de-emphasizing of IB volunteers, many of whom left Poland. Until the end of Communist rule the IB episode was duly acknowledged, but propaganda related was a far cry from veneration reserved for wartime Communist partisans or the USSR-raised Polish army. Despite some efforts on part of IB combatants, no monument has been erected.

After 1989 it was unclear whether Dąbrowszczacy were furtherly entitled to veteran privileges; the issue generated political debates until they became pointless, as almost all IB combatants had passed away. Another question was about homage references, existent in public space. A state-run institution Institute of National Remembrance, IPN declared Polish IB combatants in service of the Stalinist regime and related homage references subject to de-communisation legislation. However, efficiency of purges of public space differs depending upon local political configuration and occasionally there is heated public debate ensuing. Until today the role of Polish IB combatants remains a highly divisive topic; for some they are traitors and for some they are heroes.

In Switzerland, public sympathy was high for the Republican cause, but the federal government banned all fundraising and recruiting activities a month after the start of the war as part of the country's long-standing policy of Neutral country, neutrality. Around 800 Swiss volunteers joined the International Brigades, among them a small number of women. Sixty percent of Swiss volunteers identified as communists, while the others included socialists, anarchists and antifascists.

Some 170 Swiss volunteers were killed in the war. The survivors were tried by military courts upon their return to Switzerland for violating the criminal prohibition on foreign military service. The courts pronounced 420 sentences which ranged from around 2 weeks to 4 years in prison, and often also stripped the convicts of their political rights for the period of up to 5 years. In the Swiss society, traditionally highly appreciative of civic virtues, this translated to longtime stigmatization also after the penalty period expired. In the judgment of Swiss historian Mauro Cerutti (historian), Mauro Cerutti, volunteers were punished more harshly in Switzerland than in any other democratic country.

Motions to pardon the Swiss brigaders on the account that they fought for a Just war theory, just cause have been repeatedly introduced in the Swiss Federal Assembly, Swiss federal parliament. A first such proposal was defeated in 1939 on neutrality grounds. In 2002, Parliament again rejected a pardon of the Swiss war volunteers, with a majority arguing that they broke a law that remains in effect to this day. In March 2009, Parliament adopted the third bill of pardon, retroactively rehabilitating Swiss brigades, only a handful of whom were still alive. In 2000 there was a monument honoring Swiss IB combatants unveiled in Geneva; there are also numerous plaques mounted elsewhere, e.g. at the Volkshaus in Zürich.

In Switzerland, public sympathy was high for the Republican cause, but the federal government banned all fundraising and recruiting activities a month after the start of the war as part of the country's long-standing policy of Neutral country, neutrality. Around 800 Swiss volunteers joined the International Brigades, among them a small number of women. Sixty percent of Swiss volunteers identified as communists, while the others included socialists, anarchists and antifascists.

Some 170 Swiss volunteers were killed in the war. The survivors were tried by military courts upon their return to Switzerland for violating the criminal prohibition on foreign military service. The courts pronounced 420 sentences which ranged from around 2 weeks to 4 years in prison, and often also stripped the convicts of their political rights for the period of up to 5 years. In the Swiss society, traditionally highly appreciative of civic virtues, this translated to longtime stigmatization also after the penalty period expired. In the judgment of Swiss historian Mauro Cerutti (historian), Mauro Cerutti, volunteers were punished more harshly in Switzerland than in any other democratic country.

Motions to pardon the Swiss brigaders on the account that they fought for a Just war theory, just cause have been repeatedly introduced in the Swiss Federal Assembly, Swiss federal parliament. A first such proposal was defeated in 1939 on neutrality grounds. In 2002, Parliament again rejected a pardon of the Swiss war volunteers, with a majority arguing that they broke a law that remains in effect to this day. In March 2009, Parliament adopted the third bill of pardon, retroactively rehabilitating Swiss brigades, only a handful of whom were still alive. In 2000 there was a monument honoring Swiss IB combatants unveiled in Geneva; there are also numerous plaques mounted elsewhere, e.g. at the Volkshaus in Zürich.

* Marco, Jorge, "Transnational Soldiers and Guerrilla Warfare from the Spanish Civil War to the Second World War", ''War i History'' (2018) * Marco, Jorge and Anderson, Peter, "Legitimacy by proxy:searching for a usable past through the International Brigades in Spain’s Post-Franco democracy, 1975-2015", ''Journal of Modern European History'', 14-3 (2016

* George Orwell, Orwell, George. [1938] ''A Homage to Catalonia''. London: Penguin Books, 1969. (New edition) * Hugh Thomas (writer), Thomas, Hugh. (1961) ''The Spanish Civil War''. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1961. * Thomas, Hugh. (2003) ''The Spanish Civil War'', 2003. London: Penguin (Revised 4th edition), 2003. * Giles Tremlett. (2020) ''The International Brigades: Fascism, Freedom and the Spanish Civil War'', Bloomsbury, 2020 * John L. WainwWainwright, John, L. (2011) ''The Last to Fall: the Life and Letters of Ivor Hickman - an International Brigader in Spain''. Southampton: Hatchet Green Publishing. *

IBMT the international brigade memorial trust

Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives

Private Collection about German Exile and Spanish Civil War

Remembering the Sussex Brigaders

{{Authority control International Brigades, Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic Expatriate military units and formations Foreign volunteers in the Spanish Civil War Military units and formations disestablished in 1938 Military units and formations established in 1936

Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

to assist the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

government of the Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII, and was di ...

during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

. The organization existed for two years, from 1936 until 1938. It is estimated that during the entire war, between 40,000 and 59,000 members served in the International Brigades, including some 10,000 who died in combat. Beyond the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

, "International Brigades" is also sometimes used interchangeably with the term foreign legion in reference to military units comprising foreigners who volunteer to fight in the military of another state, often in times of war.

The headquarters of the brigade was located at the Gran Hotel, Albacete

Albacete (, also , ; ar, ﭐَلبَسِيط, Al-Basīṭ) is a city and municipality in the Spanish autonomous community of Castilla–La Mancha, and capital of the province of Albacete.

Lying in the south-east of the Iberian Peninsula, the ...

, Castilla-La Mancha. They participated in the battles of Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, Jarama

Jarama () is a river in central Spain. It flows north to south, and passes east of Madrid where the El Atazar Dam is built on a tributary, the Lozoya River. It flows into the river Tagus in Aranjuez. The Manzanares is a tributary of the Jaram ...

, Guadalajara

Guadalajara ( , ) is a metropolis in western Mexico and the capital of the list of states of Mexico, state of Jalisco. According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 1,385,629 people, making it the 7th largest city by population in Me ...

, Brunete

Brunete () is a town located on the outskirts of Madrid, Spain with a population of 10,730 people.

History

There was no military garrison in Brunete and there was no rebel attempt to seize the city during the coup of July 1936. Brunete remain ...

, Belchite, Teruel

Teruel () is a city in Aragon, located in eastern Spain, and is also the capital of Teruel Province. It has a population of 35,675 in 2014 making it the least populated provincial capital in the country. It is noted for its harsh climate, with ...

, Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

and the Ebro. Most of these ended in defeat. For the last year of its existence, the International Brigades were integrated into the Spanish Republican Army

The Spanish Republican Army ( es, Ejército de la República Española) was the main branch of the Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic between 1931 and 1939.

It became known as People's Army of the Republic (''Ejército Popular de la Rep� ...

as part of the Spanish Foreign Legion

For centuries, Spain recruited foreign soldiers to its army, forming the Foreign Regiments () - such as the Regiment of Hibernia (formed in 1709 from Irishmen who fled their own country in the wake of the Flight of the Earls and the penal ...

. The organisation was dissolved on 23 September 1938 by Spanish Prime Minister Juan Negrín

Juan Negrín López (; 3 February 1892 – 12 November 1956) was a Spanish politician and physician. He was a leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) and served as finance minister and ...

in a vain attempt to get more support from the liberal democracies on the Non-Intervention Committee

During the Spanish Civil War, several countries followed a principle of non-intervention to avoid any potential escalation or possible expansion of the war to other states. That would result in the signing of the Non-Intervention Agreement in Au ...

.

The International Brigades were strongly supported by the Comintern and represented the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

's commitment to assisting the Spanish Republic (with arms, logistics, military advisers and the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

), just as Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, Fascist Italy, and Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

were assisting the opposing Nationalist insurgency.Thomas (2003), pp. 941–945. The largest number of volunteers came from France (where the French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European Unit ...

had many members) and communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

exiles from Italy and Germany. Many Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

were part of the brigades, being particularly numerous within the volunteers coming from the United States, Poland, France, England and Argentina.

Republican volunteers who were opposed to Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory ...

did not join the Brigades but instead enlisted in the separate Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

, the POUM

The Workers' Party of Marxist Unification ( es, Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, POUM; ca, Partit Obrer d'Unificació Marxista) was a Spanish communist party formed during the Second Spanish Republic, Second Republic and mainly active a ...

(formed from Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a rev ...

, Bukharinist

The Right Opposition (, ''Pravaya oppozitsiya'') or Right Tendency (, ''Praviy uklon'') in the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was a conditional label formulated by Joseph Stalin in fall of 1928 in regards the opposition against certain me ...

, and other anti-Stalinist

The anti-Stalinist left is an umbrella term for various kinds of left-wing political movements that opposed Joseph Stalin, Stalinism and the actual system of governance Stalin implemented as leader of the Soviet Union between 1927 and 1953. Th ...

groups, which did not separate Spaniards and foreign volunteers),Homage to Catalonia. Author: Orwell, George.Publisher: Penguin Group. Date: Re-print, 2000. Work: Auto-biographical account of the Author's participation in the Spanish Civil War. or anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence i ...

groups such as the Durruti Column

The Durruti Column (Spanish: ''Columna Durruti''), with about 6,000 people, was the largest anarchist column (or military unit) formed during the Spanish Civil War. During the first months of the war, it became the most recognized and popular mi ...

, the IWA IWA may refer to:

Organizations International

* International Water Association

* International Webmasters Association

* International Woodworkers of America, United States and Canada

* International Workers Association, an anarcho-syndicalist fed ...

, and the CNT.

Formation and recruitment

communist parties

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

to recruit volunteers for Spain was first proposed in the Soviet Union in September 1936—apparently at the suggestion of Maurice Thorez

Maurice Thorez (; 28 April 1900 – 11 July 1964) was a French politician and longtime leader of the French Communist Party (PCF) from 1930 until his death. He also served as Deputy Prime Minister of France from 1946 to 1947.

Pre-War

Thorez, ...

—by Willi Münzenberg

Wilhelm "Willi" Münzenberg (14 August 1889, Erfurt, Germany – June 1940, Saint-Marcellin, France) was a German Communist political activist and publisher. Münzenberg was the first head of the Young Communist International in 1919–20 and est ...

, chief of Comintern propaganda for Western Europe. As a security measure, non-communist volunteers would first be interviewed by an NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

agent.

By the end of September, the Italian and French Communist Parties had decided to set up a column. Luigi Longo

Luigi Longo (15 March 1900 – 16 October 1980), also known as Gallo, was an Italian communist politician and secretary of the Italian Communist Party from 1964 to 1972. He was also the first foreigner to be awarded an Order of Lenin.

Early ...

, ex-leader of the Italian Communist Youth, was charged to make the necessary arrangements with the Spanish government. The Soviet Ministry of Defense

The Ministry of Defense (Minoboron; russian: Министерство обороны СССР) was a government ministry in the Soviet Union. The first Minister of Defense was Nikolai Bulganin, starting 1953. The Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star) was the ...

also helped, since they had an experience of dealing with corps of international volunteers during the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

. The idea was initially opposed by Largo Caballero

Francisco Largo Caballero (15 October 1869 – 23 March 1946) was a Spanish politician and trade unionist. He was one of the historic leaders of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and of the Workers' General Union (UGT). In 1936 and 19 ...

, but after the first setbacks of the war, he changed his mind and finally agreed to the operation on 22 October. However, the Soviet Union did not withdraw from the Non-Intervention Committee

During the Spanish Civil War, several countries followed a principle of non-intervention to avoid any potential escalation or possible expansion of the war to other states. That would result in the signing of the Non-Intervention Agreement in Au ...

, probably to avoid diplomatic conflict with France and the United Kingdom.

The main recruitment center was in Paris, under the supervision of Soviet colonel Karol "Walter" Świerczewski. On 17 October 1936, an open letter by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

to José Díaz was published in ''Mundo Obrero'', arguing that victory for the Spanish second republic was a matter not only for Spaniards but also for the whole of "progressive humanity"; in short order, communist activists joined with moderate socialist and liberal groups to form anti-fascist "popular front" militias in several countries, most of them under the control of or influenced by the Comintern.

Entry to Spain was arranged for volunteers, for instance, a Yugoslav, Josip Broz, who would become famous as Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated o ...

Tito

Tito may refer to:

People Mononyms

* Josip Broz Tito (1892–1980), commonly known mononymously as Tito, Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman

* Roberto Arias (1918–1989), aka Tito, Panamanian international lawyer, diplomat, and journ ...

, was in Paris to provide assistance, money, and passports for volunteers from Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

(including numerous Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish Civil War

The Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, known as Spanish fighters ( hr, Španjolski borci, sl, Španski borci, sr-Cyrl-Latn, Шпански борци, separator=" / ", Španski borci) and Yugoslav brigadistas ( es, brigadistas yugo ...

). Volunteers were sent by train or ship from France to Spain, and sent to the base at Albacete

Albacete (, also , ; ar, ﭐَلبَسِيط, Al-Basīṭ) is a city and municipality in the Spanish autonomous community of Castilla–La Mancha, and capital of the province of Albacete.

Lying in the south-east of the Iberian Peninsula, the ...

. Many of them also went by themselves to Spain. The volunteers were under no contract, nor defined engagement period, which would later prove a problem.

Also, many Italians, Germans, and people from other countries joined the movement, with the idea that combat in Spain was the first step to restore democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

or advance a revolutionary cause in their own country. There were also many unemployed workers (especially from France), and adventurers. Finally, some 500 communists who had been exiled to Russia were sent to Spain (among them, experienced military leaders from the First World War like "Kléber" Stern, "Gomez" Zaisser, "Lukacs" Zalka and "Gal" Galicz, who would prove invaluable in combat).

The operation was met with enthusiasm by communists, but by anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

s with skepticism, at best. At first, the anarchists, who controlled the borders with France, were told to refuse communist volunteers, but reluctantly allowed their passage after protests. Keith Scott Watson, a journalist who fought alongside Esmond Romilly at Cerro de los Ángeles and who later “resigned” from the Thälmann Battalion

The Thälmann Battalion was a battalion of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. It was named after the imprisoned German communist leader Ernst Thälmann (born 16 April 1886, executed 18 August 1944) and included approximately 1,50 ...

, describes in his memoirs how he was detained and interrogated by Anarchist border guards before eventually being allowed into the country. A group of 500 volunteers (mainly French, with a few exiled Poles and Germans) arrived in Albacete on 14 October 1936. They were met by international volunteers who had already been fighting in Spain: Germans from the Thälmann Battalion

The Thälmann Battalion was a battalion of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. It was named after the imprisoned German communist leader Ernst Thälmann (born 16 April 1886, executed 18 August 1944) and included approximately 1,50 ...

, Italians from the Centuria Gastone Sozzi and French from the Commune de Paris Battalion. Among them was the poet John Cornford

Rupert John Cornford (27 December 1915 – 28 December 1936) was an English poet and communist. During the first year of the Spanish Civil War, he was a member of the POUM militia and later the International Brigades. He died while fighting a ...

, who had travelled down through France and Spain with a group of fellow intellectuals and artists including John Sommerfield, Bernard Knox

Bernard MacGregor Walker Knox (November 24, 1914 – July 22, 2010Wolfgang Saxon ''The New York Times'', August 16, 2010.) was an English classicist, author, and critic who became an American citizen. He was the first director of the Center ...

and Jan Kurzke, all of whom left detailed memoirs of their battle experiences.

On 30 May 1937, the Spanish liner '' Ciudad de Barcelona'', carrying 200–250 volunteers from Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

to Spain, was torpedoed by a Nationalist submarine off the coast of Malgrat de Mar

Malgrat de Mar is a municipality in the ''comarca'' of the Maresme, in the province of Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. It is situated on the Costa Brava between Santa Susanna and Blanes. A local road runs from the town to the main N-II road, while ...

. The ship sunk and up to 65 volunteers are estimated to have drowned.

Albacete soon became the International Brigades headquarters and its main depot. It was run by a ''troika'' of Comintern heavyweights: André Marty

André Marty (6 November 1886 – 23 November 1956) was a leading figure in the French Communist Party (PCF) for nearly thirty years. He was also a member of the National Assembly, with some interruptions, from 1924 to 1955; Secretary of Comintern ...

was commander; Luigi Longo

Luigi Longo (15 March 1900 – 16 October 1980), also known as Gallo, was an Italian communist politician and secretary of the Italian Communist Party from 1964 to 1972. He was also the first foreigner to be awarded an Order of Lenin.

Early ...

(''Gallo'') was Inspector-General; and Giuseppe Di Vittorio

Giuseppe Di Vittorio ( Cerignola, 11 August 1892 – Lecco, 3 November 1957), also known as Nicoletti, was an Italian trade union leader and Communist politician. He was one of the most influential trade union leaders of the labour movement after ...

(''Nicoletti'') was chief political commissar.

There were many Jewish volunteers amongst the brigaders - about a quarter of the total. A Jewish company was formed within the Polish battalion that was named after Naftali Botwin

Izaak Naftali Botwin, (Yiddish: יצחק נפתלי באָטווין) (19 February 1905, Kamianka-Buzka, – 6 August 1925, Lwów), was a Polish communist and labour activist who was executed for the murder of a police informant. During the Spanis ...

, a young Jewish communist killed in Poland in 1925.

The French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European Unit ...

provided uniforms for the Brigades. They were organized into mixed brigade

Mixed brigade ( es, brigada mixta) was a basic tactical military unit of the Republican army during the Spanish Civil War. It was initially designed as “pocket division”, an innovative maneuverable combined-arms formation. Because of high sa ...

s, the basic military unit of the Republican People's Army. Discipline was severe. For several weeks, the Brigades were locked in their base while their strict military training was underway.

Service

First engagements: Siege of Madrid

Battle of Madrid

The siege of Madrid was a two-and-a-half-year siege of the Republican-controlled Spanish capital city of Madrid by the Nationalist armies, under General Francisco Franco, during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). The city, besieged from Octo ...

was a major success for the Republic, and staved off the prospect of a rapid defeat at the hands of Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

's forces. The role of the International Brigades in this victory was generally recognized but was exaggerated by Comintern propaganda so that the outside world heard only of their victories and not those of Spanish units. So successful was such propaganda that the British Ambassador, Sir Henry Chilton, declared that there were no Spaniards in the army which had defended Madrid. The International Brigade forces that fought in Madrid arrived after another successful Republican fighting. Of the 40,000 Republican troops in the city, the foreign troops numbered less than 3,000.

Even though the International Brigades did not win the battle by themselves, nor significantly change the situation, they certainly did provide an example by their determined fighting and improved the morale of the population by demonstrating the concern of other nations in the fight. Many of the older members of the International Brigades provided valuable combat experience, having fought during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

(Spain remained neutral in 1914–1918) and the Irish War of Independence (some had fought in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

while others had fought in the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

(IRA)).

One of the strategic positions in Madrid was the Casa de Campo

The Casa de Campo (, for Spanish: ''Country House'') is the largest public park in Madrid. It is situated west of central Madrid, Spain. It gets its name 'Country House' because it was once a royal hunting estate, located just west of the Ro ...

. There the Nationalist troops were Moroccans

Moroccans (, ) are the citizens and nationals of the Kingdom of Morocco. The country's population is predominantly composed of Arabs and Berbers (Amazigh). The term also applies more broadly to any people who are of Moroccan nationality, s ...

, commanded by General José Enrique Varela

José Enrique Varela Iglesias, 1st Marquis of San Fernando de Varela (17 April 1891 – 24 March 1951) was a Spanish military officer noted for his role as a Nationalist commander in the Spanish Civil War.

Early career

Varela started his milita ...

. They were stopped by III and IV Brigades of the Spanish Republican Army

The Spanish Republican Army ( es, Ejército de la República Española) was the main branch of the Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic between 1931 and 1939.

It became known as People's Army of the Republic (''Ejército Popular de la Rep� ...

.

On 9 November 1936, the XI International Brigade

The XI International Brigade fought for the Spanish Second Republic in the Spanish Civil War.

It would become especially renowned for providing desperately needed support in the darkest hours of the Republican defense of Madrid on 8 November 193 ...

– comprising 1,900 men from the Edgar André Battalion, the Commune de Paris Battalion and the Dabrowski Battalion

The Dabrowski Battalion, also known as Dąbrowszczacy (), was a battalion of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. It was initially formed entirely of volunteers, "chiefly composed of Polish miners recently living and working in F ...

, together with a British machine-gun company — took up position at the Casa de Campo. In the evening, its commander, General Kléber, launched an assault on the Nationalist positions. This lasted for the whole night and part of the next morning. At the end of the fight, the Nationalist troops had been forced to retreat, abandoning all hopes of a direct assault on Madrid by Casa de Campo, while the XIth Brigade had lost a third of its personnel.

On 13 November, the 1,550-man strong XII International Brigade

The XII International Brigade was mustered on 7 November 1936 at Albacete, Spain. It was formerly named the Garibaldi Brigade, after the most famous and inspiring leader in the Italian Independence Wars, General Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Structure

Its ...

, made up of the Thälmann Battalion, the Garibaldi Battalion

The Garibaldi Battalion (Garibaldi Brigade after April 1937) was a largely-Italian volunteer unit of the International Brigades that fought on the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War from October 1936 to 1938. It was named after Giuseppe Ga ...

and the André Marty Battalion, deployed. Commanded by General "Lukacs", they assaulted Nationalist positions on the high ground of Cerro de Los Angeles. As a result of language and communication problems, command issues, lack of rest, poor coordination with armored units, and insufficient artillery support, the attack failed.

On 19 November, the anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s were forced to retreat, and Nationalist troops — Moroccans and Spanish Foreign Legionnaires, covered by the Nazi Condor Legion

The Condor Legion (german: Legion Condor) was a unit composed of military personnel from the air force and army of Nazi Germany, which served with the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War of July 1936 to March 1939. The Condor Legio ...

— captured a foothold in the University City. The 11th Brigade was sent to drive the Nationalists out of the University City. The battle was extremely bloody, a mix of artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

and aerial bombardment

An airstrike, air strike or air raid is an offensive operation carried out by aircraft. Air strikes are delivered from aircraft such as blimps, balloons, fighters, heavy bombers, ground attack aircraft, attack helicopters and drones. The offic ...

, with bayonet and grenade fights, room by room. Anarchist leader Buenaventura Durruti

José Buenaventura Durruti Dumange (14 July 1896 – 20 November 1936) was a Spanish insurrectionary, anarcho-syndicalist militant involved with the CNT and FAI in the periods before and during the Spanish Civil War. Durruti played an in ...

was shot there on 19 November 1936 and died the next day. The battle in the university went on until three-quarters of the University City was under Nationalist control. Both sides then started setting up trenches and fortifications. It was then clear that any assault from either side would be far too costly; the Nationalist leaders had to renounce the idea of a direct assault on Madrid, and prepare for a siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

of the capital.

On 13 December 1936, 18,000 nationalist troops attempted an attack to close the encirclement of Madrid at Guadarrama

Guadarrama is a town and municipality in the Cuenca del Guadarrama comarca, in the Community of Madrid, Spain.

Its population is 13,032 (winter, according to a 2006 census); the population swells to approximately 60,000 in summer.

Its name co ...

— an engagement known as the Battle of the Corunna Road. The Republicans sent in a Soviet armored unit, under General Dmitry Pavlov, and both XI and XII International Brigades. Violent combat followed, and they stopped the Nationalist advance.

An attack was then launched by the Republic on the Córdoba front. The battle ended in a form of stalemate; a communique was issued, saying: "During the day the advance continued without the loss of any territory." Poets Ralph Winston Fox

Ralph Winston Fox (30 March 1900 – 28 December 1936) was a British revolutionary, journalist, novelist, and historian, best remembered as a biographer of Lenin and Genghis Khan. Fox was one of the best-known members of the Communist Party o ...

and John Cornford

Rupert John Cornford (27 December 1915 – 28 December 1936) was an English poet and communist. During the first year of the Spanish Civil War, he was a member of the POUM militia and later the International Brigades. He died while fighting a ...

were killed. Eventually, the Nationalists advanced, taking the hydroelectric

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other renewable sources combined and ...

station at El Campo. André Marty

André Marty (6 November 1886 – 23 November 1956) was a leading figure in the French Communist Party (PCF) for nearly thirty years. He was also a member of the National Assembly, with some interruptions, from 1924 to 1955; Secretary of Comintern ...

accused the commander of the Marseillaise Battalion

image:Perelachaise-BrigadesInternationales-p1000377.jpg, 300px, A memorial commemorating the International Brigades

The XIV International Brigade was one of several International Brigades, international brigades that fought for the Spanish Second ...

, Gaston Delasalle, of espionage and treason and had him executed. (It is doubtful that Delasalle would have been a spy for Francisco Franco; he was denounced by his second-in-command, André Heussler, who was subsequently executed for treason during World War II by the French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

.)

Further Nationalist attempts after Christmas to encircle Madrid met with failure, but not without extremely violent combat. On 6 January 1937, the Thälmann Battalion arrived at Las Rozas Las Rozas may refer to:

Places

;Spain

*Las Rozas de Madrid, municipality in the Community of Madrid

* Las Rozas de Valdearroyo, municipality in Cantabria

Sport

*Las Rozas CF

Las Rozas Club de Fútbol is a Spanish football club based in Las Roz ...

, and held its positions until it was destroyed as a fighting force. On 9 January, only 10 km had been lost to the Nationalists, when the XIII International Brigade

The 13th International Brigade – often known as the XIII Dąbrowski Brigade – fought for the Spanish Second Republic during the Spanish Civil War, in the International Brigades. The brigade was dissolved and then reformed on four occasions.

...

and XIV International Brigade

300px, A memorial commemorating the International Brigades

The XIV International Brigade was one of several international brigades that fought for the Spanish Second Republic during the Spanish Civil War.

History and structure

It was raised on ...

and the 1st British Company, arrived in Madrid. Violent Republican assaults were launched in an attempt to retake the land, with little success. On 15 January, trenches and fortifications were built by both sides, resulting in a stalemate.

The Nationalists did not take Madrid until the very end of the war, in March 1939, when they marched in unopposed. There were some pockets of resistance during the subsequent months.

Battle of Jarama

On 6 February 1937, following the fall ofMálaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most pop ...

, the nationalists launched an attack on the Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

–Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

road, south of Madrid. The Nationalists quickly advanced on the little town of Ciempozuelos

Ciempozuelos () is a municipality in Spain located in the Community of Madrid. The municipality spans across a total area of 49.64 km2 and, as of 1 January 2020, it has a registered population of 25,104.

Geography

The municipality is located in ...

, held by the XV International Brigade

The Abraham Lincoln Brigade ( es, Brigada Abraham Lincoln), officially the XV International Brigade (''XV Brigada Internacional''), was a mixed brigade that fought for the Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War as a part of the Internation ...

. was composed of the British Battalion

The British Battalion (1936–1938; officially the Saklatvala Battalion) was the 16th battalion of the XV International Brigade, one of the mixed brigades of the International Brigades, during the Spanish Civil War. It comprised British and ...

(British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

and Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

), the Dimitrov Battalion

The Dimitrov Battalion was part of the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. It was the 18th battalion formed, and was named after Georgi Dimitrov, a Bulgarian communist and General Secretary of the Comintern in that period. History ...

(miscellaneous Balkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

nationalities), the Sixth February Battalion (Belgians

Belgians ( nl, Belgen; french: Belges; german: Belgier) are people identified with the Kingdom of Belgium, a federal state in Western Europe. As Belgium is a multinational state, this connection may be residential, legal, historical, or cultur ...

and French), the Canadian Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion and the Abraham Lincoln Brigade

The Abraham Lincoln Brigade ( es, Brigada Abraham Lincoln), officially the XV International Brigade (''XV Brigada Internacional''), was a mixed brigade that fought for the Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War as a part of the Internation ...

. An independent 80-men-strong (mainly) Irish unit, known afterward as the Connolly Column

The Connolly Column (, ) was the name given to a group of Irish republican socialist volunteers who fought for the Second Spanish Republic in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. They were named after James Connolly, the ex ...

, also fought. Battalions were rarely composed entirely of one nationality, rather they were, for the most part, a mix of many.

On 11 February 1937, a Nationalist brigade launched a surprise attack on the André Marty Battalion (XIV International Brigade

300px, A memorial commemorating the International Brigades

The XIV International Brigade was one of several international brigades that fought for the Spanish Second Republic during the Spanish Civil War.

History and structure

It was raised on ...

), killing its sentries silently and crossing the Jarama

Jarama () is a river in central Spain. It flows north to south, and passes east of Madrid where the El Atazar Dam is built on a tributary, the Lozoya River. It flows into the river Tagus in Aranjuez. The Manzanares is a tributary of the Jaram ...

. The Garibaldi Battalion stopped the advance with heavy fire. At another point, the same tactic allowed the Nationalists to move their troops across the river. On 12 February, the British Battalion, XV International Brigade

The Abraham Lincoln Brigade ( es, Brigada Abraham Lincoln), officially the XV International Brigade (''XV Brigada Internacional''), was a mixed brigade that fought for the Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War as a part of the Internation ...

took the brunt of the attack, remaining under heavy fire for seven hours. The position became known as "Suicide Hill". At the end of the day, only 225 of the 600 members of the British battalion remained. One company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of people, whether Natural person, natural, Legal person, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common p ...

was captured by ruse, when Nationalists advanced among their ranks singing ''The Internationale

"The Internationale" (french: "L'Internationale", italic=no, ) is an international anthem used by various communist and socialist groups; currently, it serves as the official anthem of the Communist Party of China. It has been a standard of t ...

''.

On 17 February, the Republican Army counter-attacked. On 23 and 27 February, the International Brigades were engaged, but with little success. The Lincoln Battalion was put under great pressure, with no artillery support. It suffered 120 killed and 175 wounded. Amongst the dead was the Irish poet Charles Donnelly and Leo Greene.

There were heavy casualties on both sides, and although "both claimed victory ... both suffered defeats". The battle resulted in a stalemate, with both sides digging in and creating elaborate trench systems. On 22 February 1937, the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

Non-Intervention Committee

During the Spanish Civil War, several countries followed a principle of non-intervention to avoid any potential escalation or possible expansion of the war to other states. That would result in the signing of the Non-Intervention Agreement in Au ...

ban on foreign volunteers went into effect.

Battle of Guadalajara

Guadalajara

Guadalajara ( , ) is a metropolis in western Mexico and the capital of the list of states of Mexico, state of Jalisco. According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 1,385,629 people, making it the 7th largest city by population in Me ...

, 50 km from Madrid. The whole Italian expeditionary corps — 35,000 men, with 80 battle tanks and 200 field artillery — was deployed, as Benito Mussolini wanted the victory to be credited to Italy. On 9 March 1937, the Italians made a breach in the Republican lines but did not properly exploit the advance. However, the rest of the Nationalist army was advancing, and the situation appeared critical for the Republicans. A formation drawn from the best available units of the Republican army, including the XI and XII International Brigade

The XII International Brigade was mustered on 7 November 1936 at Albacete, Spain. It was formerly named the Garibaldi Brigade, after the most famous and inspiring leader in the Italian Independence Wars, General Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Structure

Its ...

s, was quickly assembled.

At dawn on 10 March, the Nationalists closed in, and by noon, the Garibaldi Battalion counterattacked. Some confusion arose from the fact that the sides were not aware of each other's movements, and that both sides spoke Italian; this resulted in scouts from both sides exchanging information without realizing they were enemies. The Republican lines advanced and made contact with XI International Brigade. Nationalist tanks were shot at and infantry patrols came into action.

On 11 March, the Nationalist army broke the front of the Republican army. The Thälmann Battalion

The Thälmann Battalion was a battalion of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. It was named after the imprisoned German communist leader Ernst Thälmann (born 16 April 1886, executed 18 August 1944) and included approximately 1,50 ...

suffered heavy losses, but succeeded in holding the Trijueque–Torija

Torija is a municipality located in the Guadalajara (province), province of Guadalajara, Castile-La Mancha, Spain. According to the 2004 census (Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spain), INE), the municipality has a population of 576 inhabitan ...

road. The Garibaldi also held its positions. On 12 March, Republican planes and tanks attacked. The Thälmann Battalion attacked Trijuete in a bayonet charge and re-took the town, capturing numerous prisoners.

Other battles

The International Brigades also saw combat in theBattle of Teruel

The Battle of Teruel was fought in and around the city of Teruel during the Spanish Civil War between December 1937 and February 1938, during the worst Spanish winter in 20 years.Hugh Purcell, p. 95. The battle was one of the bloodiest actions of ...

in January 1938. The 35th International Division suffered heavily in this battle from aerial bombardment as well as shortages of food, winter clothing, and ammunition. The XIV International Brigade

300px, A memorial commemorating the International Brigades

The XIV International Brigade was one of several international brigades that fought for the Spanish Second Republic during the Spanish Civil War.

History and structure

It was raised on ...

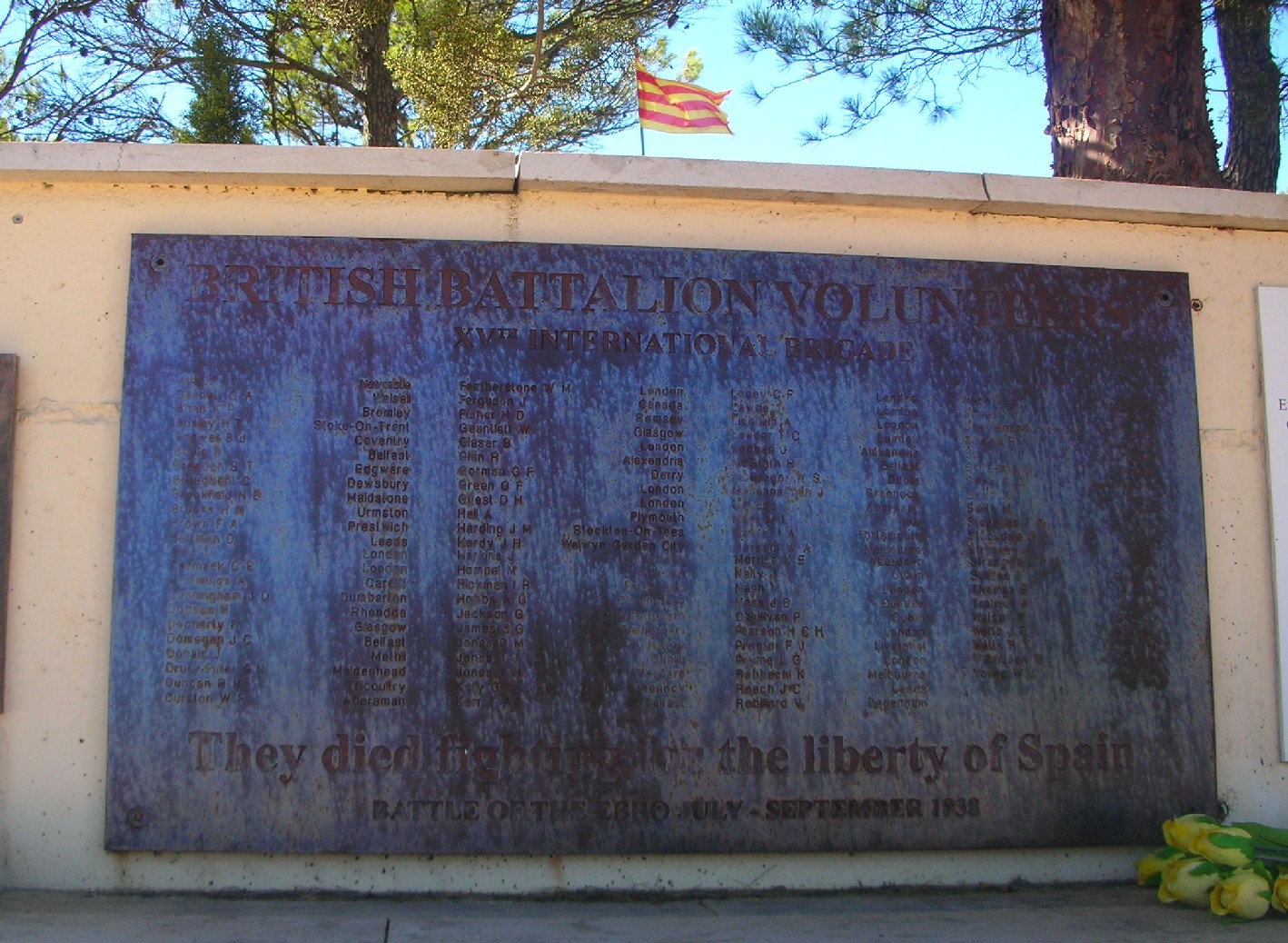

fought in the Battle of Ebro in July 1938, the last Republican offensive of the war.

Casualties

Existing primary sources provide conflicting information as to the number of brigadiers killed; a report of the IB Albacete staff from late March 1938 claimed 4,575 KIA, an internal Soviet communication to Moscow by anNKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

major Semyon Gnadin from late July 1938 claimed 3,615 KIA, while the prime minister Juan Negrín

Juan Negrín López (; 3 February 1892 – 12 November 1956) was a Spanish politician and physician. He was a leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) and served as finance minister and ...

in his farewell address in Barcelona of October 28, 1938 mentioned 5,000 fallen.

Also in historiography there is no agreement as to fatal casualties. One exact figures offered is 9,934; it was calculated in the mid-1970s and is at times repeated until today. The highest estimate identified is 15,000 KIA. Many scholars prefer 10,000, also in recently published works. The popular Osprey series claims there were at least 7,800 killed. However, other authors provide estimates that point rather to the range from 6,100 to 6,500. In some non-scholarly publications the number is given as 4,900. The above figures include brigadiers killed in action, these who died of wounds later or those who were executed as POWs. They do not include brigadiers who were executed by their own side, the figure that some claim might have been 500; they also do not include victims of accidents (self-shooting, traffic, drownings etc) or these who perished due to health problems (illness, frostbiten, poisoning etc).

The total number of casualties is given as 48,909. It includes killed, missing and wounded, though probably contains numerous duplicated cases, as one individual might have suffered wounds a few times.

The ratio of KIA to all IB combatants as calculated by historians might differ even more as it depends not only on estimates as to the number of killed, but also on estimates as to the total number of volunteers. Some sources suggest the figure of 8.3%, some authors claim 15%, others opt for 16.7% or endorse the ratio of 28.6%; a single author arrived even at 33%. In comparison, in shock units used by the Nationalists, though they were not entirely comparable, the ratio was 11.3% for the Carlist requetés and 14.6% for the Moroccan regulares

The Fuerzas Regulares Indígenas ("Indigenous Regular Forces"), known simply as the Regulares (Regulars), are volunteer infantry units of the Spanish Army, largely recruited in the cities of Ceuta and Melilla. Consisting of indigenous infantry ...

. The overall percentage of killed in action in armies of both sides is estimated at some 7%.

Estimates of KIA ratio for major national contingents differ enormously and often bear no reasonable relation to the overall KIA ratio, calculated for the Brigades. For the French (including French-speaking Belgians and Swiss) the figures range between 12% and 18%; for the Germans (including Austrians and German-speaking Swiss) between 22% and 40% for the Poles (including Ukrainians, Jews, Belorussians) between 30% and 62%, for the Italians between 18% and 20%, for the Americans between 13% and 32%, for the Yugoslavs between 35% and 50%, for the British between 16% and 22% and for the Canadians between 43% and 57%.

Disbandment

Battle of the Ebro

The Battle of the Ebro ( es, Batalla del Ebro, ca, Batalla de l'Ebre) was the longest and largest battle of the Spanish Civil War and the greatest, in terms of manpower, logistics and material ever fought on Spanish soil. It took place between Ju ...

, the Non-Intervention Committee

During the Spanish Civil War, several countries followed a principle of non-intervention to avoid any potential escalation or possible expansion of the war to other states. That would result in the signing of the Non-Intervention Agreement in Au ...

demanded the withdrawal of the International Brigades. The Republican government of Juan Negrín

Juan Negrín López (; 3 February 1892 – 12 November 1956) was a Spanish politician and physician. He was a leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) and served as finance minister and ...

announced the decision in the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

on 21 September 1938. The disbandment was part of an ill-advised effort to get the Nationalists' foreign backers to withdraw their troops and to persuade the Western democracies such as France and Britain to end their arms embargo

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they m ...

on the Republic.

By this time there were about an estimated 10,000 foreign volunteers still serving in Spain for the Republican side, and about 50,000 foreign conscripts for the Nationalists (excluding another 30,000 Moroccans). Perhaps half of the International Brigadistas were exiles or refugees from Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy or other countries, such as Hungary, which had authoritarian right-wing governments at the time. These men could not safely return home and some were instead given honorary Spanish citizenship and integrated into Spanish units of the Popular Army. The remainder were repatriated to their own countries. The Belgian and Dutch volunteers lost their citizenship because they had served in a foreign army.

Composition

Overview

The first brigades were composed mostly of French, Belgian, Italian, and German volunteers, backed by a sizeable contingent of Polish miners from Northern France and Belgium. The XIth, XIIth and XIIIth were the first brigades formed. Later, the XIVth and XVth Brigades were raised, mixing experienced soldiers with new volunteers. Smaller Brigades — the 86th, 129th and 150th - were formed in late 1937 and 1938, mostly for temporary tactical reasons. About 32,000 foreigners volunteered to defend the Spanish Republic, the vast majority of them with the International Brigades. Many were veterans of World War I. Their early engagements in 1936 during the Siege of Madrid amply demonstrated their military and propaganda value. The international volunteers were mainly socialists, communists, or others willing to accept communist authority, and a high proportion wereJewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

. Some were involved in the Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

May Days

The May Days, sometimes also called May Events, refer to a series of clashes between 3 and 8 May 1937 during which factions on the Republican faction of the Spanish Civil War engaged one another in street battles in various parts of Catalonia, ...

fighting against leftist opponents of the Communists: the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM

The Workers' Party of Marxist Unification ( es, Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, POUM; ca, Partit Obrer d'Unificació Marxista) was a Spanish communist party formed during the Second Spanish Republic, Second Republic and mainly active a ...

) (''Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista'', an anti- Stalinist Marxist party) and the anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

CNT (CNT, Confederación Nacional del Trabajo) and FAI (FAI, Iberian Anarchist Federation), who had strong support in Catalonia. These libertarian groups attracted fewer foreign volunteers.

To simplify communication, the battalions usually concentrated on people of the same nationality or language group. The battalions were often (formally, at least) named after inspirational people or events. From spring 1937 onwards, many battalions contained one Spanish volunteer company of about 150 men.

Later in the war, military discipline tightened and learning Spanish became mandatory. By decree of 23 September 1937, the International Brigades formally became units of the Spanish Foreign Legion

For centuries, Spain recruited foreign soldiers to its army, forming the Foreign Regiments () - such as the Regiment of Hibernia (formed in 1709 from Irishmen who fled their own country in the wake of the Flight of the Earls and the penal ...

. This made them subject to the Spanish Code of Military Justice. However, the Spanish Foreign Legion itself sided with the Nationalists throughout the coup and the civil war. The same decree also specified that non-Spanish officers in the Brigades should not exceed Spanish ones by more than 50 percent.

Non-Spanish battalions

*

* Abraham Lincoln Battalion

The Lincoln Battalion ( es, Batallón Abraham Lincoln) was the 17th (later the 58th) battalion of the XV International Brigade, a mixed brigade of the International Brigades also known as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. It was organized by the Com ...

- from the United States and Canada, with some British, Cypriots, and Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

ans from the Chilean Worker Club of New York.

** Connolly Column

The Connolly Column (, ) was the name given to a group of Irish republican socialist volunteers who fought for the Second Spanish Republic in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. They were named after James Connolly, the ex ...

- a mostly Irish republican group who fought as a section of the Lincoln Battalion.

* Mickiewicz Battalion - predominantly Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

.

* André Marty

André Marty (6 November 1886 – 23 November 1956) was a leading figure in the French Communist Party (PCF) for nearly thirty years. He was also a member of the National Assembly, with some interruptions, from 1924 to 1955; Secretary of Comintern ...

Battalion - predominantly French and Belgian.

* British Battalion

The British Battalion (1936–1938; officially the Saklatvala Battalion) was the 16th battalion of the XV International Brigade, one of the mixed brigades of the International Brigades, during the Spanish Civil War. It comprised British and ...

- mainly British but with many from Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

and other Commonwealth countries

The Commonwealth of Nations is a voluntary association of 56 sovereign states. Most of them were British colonies or dependencies of those colonies.

No one government in the Commonwealth exercises power over the others, as is the case in a po ...

.

* Checo-Balcánico Battalion - Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

n and Balkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

.

* Commune de Paris Battalion - predominantly French.

* Deba Blagoiev Battalion - predominantly Bulgarian, later merged into the Đaković Battalion.

* Dimitrov Battalion

The Dimitrov Battalion was part of the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. It was the 18th battalion formed, and was named after Georgi Dimitrov, a Bulgarian communist and General Secretary of the Comintern in that period. History ...

- Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Yugoslav, Bulgarian, Czechoslovakian, Hungarian and Romanian. (Named after Georgi Dimitrov.)

* Đuro Đaković

Đuro Đaković (30 November 1886 – 25 April 1929) was a Yugoslav metal worker, communist and revolutionary. Đaković was the organizational secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, from April 1928 to April ...

Battalion - Yugoslav, Bulgarian, anarchist, named for former Yugoslav Communist Party secretary Djuro Đaković.

* Dabrowski Battalion

The Dabrowski Battalion, also known as Dąbrowszczacy (), was a battalion of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. It was initially formed entirely of volunteers, "chiefly composed of Polish miners recently living and working in F ...

- mostly Polish and Hungarian, also Czechoslovak, Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

, Bulgarian and Palestinian Jews

Palestinian Jews or Jewish Palestinians were the Jewish inhabitants of the Palestine region (known in Hebrew as ''Eretz Yisrael'', ) prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948.

The common term used to refer to the Jewish commu ...

.

* Edgar André Battalion - mostly German, also Austrian, Yugoslav, Bulgarian, Albanian, Romanian, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian and Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

.

* Español Battalion - Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican, Chilean, Argentine and Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

n.

* Figlio Battalion - mostly Italian; later merged with the Garibaldi Battalion

The Garibaldi Battalion (Garibaldi Brigade after April 1937) was a largely-Italian volunteer unit of the International Brigades that fought on the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War from October 1936 to 1938. It was named after Giuseppe Ga ...

.

* Garibaldi Battalion

The Garibaldi Battalion (Garibaldi Brigade after April 1937) was a largely-Italian volunteer unit of the International Brigades that fought on the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War from October 1936 to 1938. It was named after Giuseppe Ga ...

- raised as the Italoespañol Battalion and renamed. Mostly Italian and Spanish, but contained some Albanians.

* George Washington Battalion

The Lincoln Battalion ( es, Batallón Abraham Lincoln) was the 17th (later the 58th) battalion of the XV International Brigade, a mixed brigade of the International Brigades also known as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. It was organized by the Comm ...

- the second U.S. battalion. Later merged with the Lincoln Battalion, to form the Lincoln-Washington Battalion.

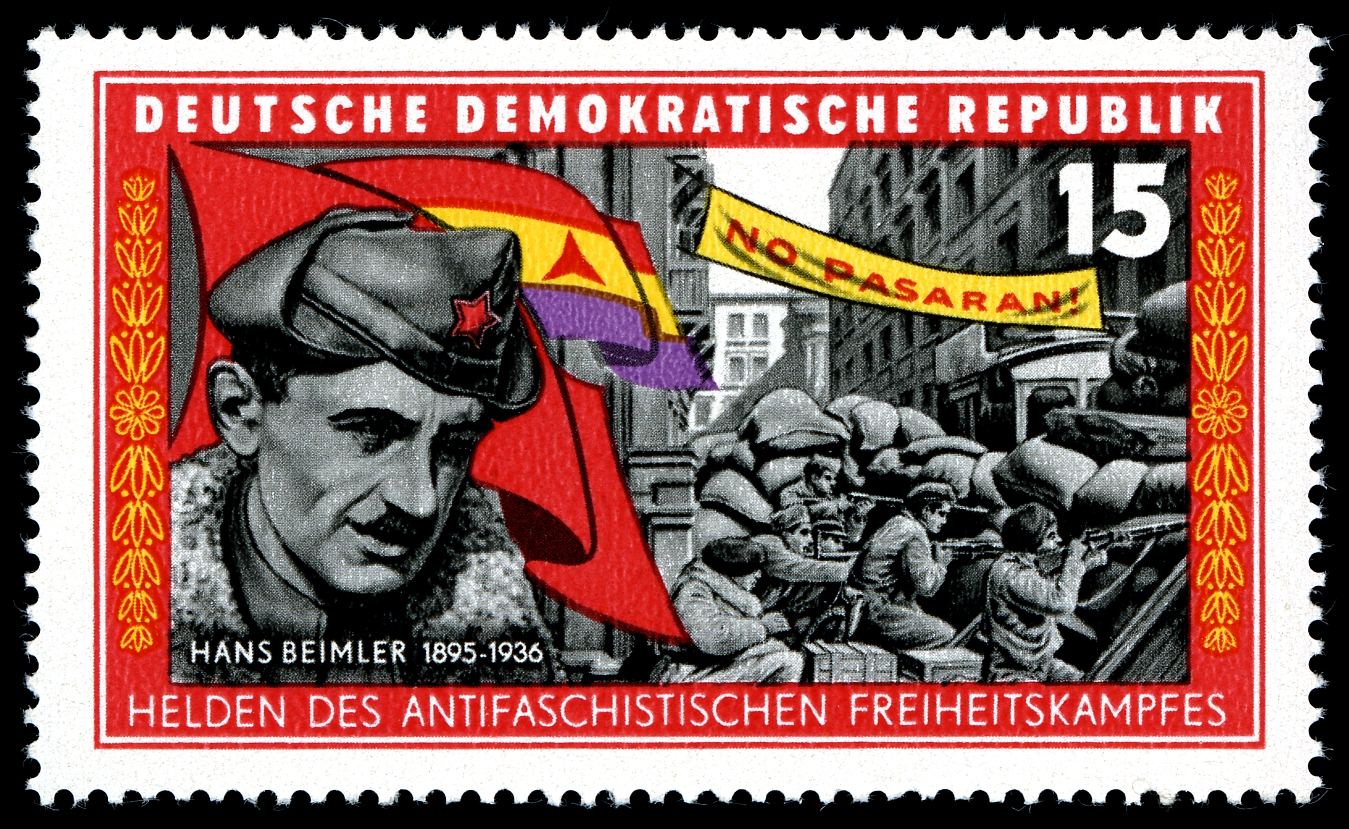

* Hans Beimler Battalion - mostly German; later merged with the Thälmann Battalion

The Thälmann Battalion was a battalion of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. It was named after the imprisoned German communist leader Ernst Thälmann (born 16 April 1886, executed 18 August 1944) and included approximately 1,50 ...

.

* Henri Barbusse Battalion

The Henri Barbusse Battalion was a French International Brigade battalion during the Spanish Civil War. The Battalion served in the XIV International Brigade. It was named after French communist and writer, Henri Barbusse, who died in 1935.

Histo ...

- predominantly French.

* Henri Vuilleman Battalion - predominantly French.

* (Matteotti Battalion) - predominantly Italian and the first international group to reach Spain.

* Louise Michel Battalions - French-speaking, later merged with the Henri Vuillemin Battalion.

* Mackenzie–Papineau Battalion

The Mackenzie–Papineau Battalion or Mac-Paps were a battalion of Canadians who fought as part of the XV International Brigade on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s. Except for France, no other country had a greater p ...

- the "Mac-Paps", predominantly Canadian.

* Marseillaise Battalion - predominantly French, commanded by George Nathan

Samuel George Montague Nathan (20 January 1895 – 16 July 1937) was an English soldier who served in the British Army during World War I, the Royal Irish Constabulary's Auxiliary Division during the Irish War of Independence and the Internatio ...

.

** Incorporated one separate British company.

* Palafox Battalion

The Palafox Battalion was a volunteer unit of largely Polish and Spanish composition in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. It was named after José de Palafox, a Spanish general who successfully fought French Napoleonic for ...

- Yugoslav, Polish, Czechoslovakian, Hungarian, Jewish and French.

** Naftali Botwin Company - a Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

unit formed within the Palafox Battalion

The Palafox Battalion was a volunteer unit of largely Polish and Spanish composition in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. It was named after José de Palafox, a Spanish general who successfully fought French Napoleonic for ...

in December 1937.

* Pierre Brachet Battalion - mostly French.

* Rakosi Battalion

The Rákosi Battalion was a volunteer unit founded in April 1937. It was formed predominantly of Hungarians, who fought in the CL International Brigade and the XIII International Brigade during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). The battalion wa ...

- mainly Hungarian, also Czechoslovaks, Ukrainians, Poles, Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

, Mongolians

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member of ...

and Palestinian Jews.

* Nine Nations Battalion (also known as the ''Sans nons'' and ''Neuf Nationalités'') - French, Belgian, Italian, German, Austrian, Dutch, Danish, Swiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

* Swiss, North Carolina

*Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

*Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

*Swiss Internation ...

and Polish.

* Sixth of February Battalion

The "Sixth of February" Battalion (french: Bataillon Six-Février, es, Batallón Seis de Febrero) was a Franco-Belgian International Brigade battalion during the Spanish Civil War. The Battalion served in the XV and XIV International Brigades. ...

- French, Belgian, Moroccan, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

n, Libya