Intelligentia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the intelligentsia consists of scholars, academics, teachers, journalists, and literary writers.

Conceptually, the intelligentsia status class arose in the late 18th century, during the

The intelligentsia existed as a social stratum in European societies before the term ''inteligencja'' was coined in 19th-century Poland, to identify the intellectual people whose professions placed them outside the traditional workplaces and labours of the town-and-country social classes (royalty, aristocracy, bourgeoisie) of a monarchy; thus the ''inteligencja'' are a social class native to the city. In their functions as a status class, the intellectuals realised the cultural development of cities, the dissemination of printed knowledge (literature, textbooks, newspapers), and the economic development of housing for rent (the tenement house) for the teacher, the journalist, and the civil servant.

In ''On Love of the fatherland'' (1844), the Polish philosopher

The intelligentsia existed as a social stratum in European societies before the term ''inteligencja'' was coined in 19th-century Poland, to identify the intellectual people whose professions placed them outside the traditional workplaces and labours of the town-and-country social classes (royalty, aristocracy, bourgeoisie) of a monarchy; thus the ''inteligencja'' are a social class native to the city. In their functions as a status class, the intellectuals realised the cultural development of cities, the dissemination of printed knowledge (literature, textbooks, newspapers), and the economic development of housing for rent (the tenement house) for the teacher, the journalist, and the civil servant.

In ''On Love of the fatherland'' (1844), the Polish philosopher

О понятии «интеллигенция» в творчестве И. С. Аксакова и П. Д. Боборыкина

'. Известия Пензенского государственного педагогического университета им. В.Г. Белинского, 27, 2012 (in Russian)Пётр Боборыкин. ''Русская интеллигенция''. Русская мысль, 1904, № 12 (in Russian)Пётр Боборыкин.

Подгнившие "Вехи"

'. Сб. статей ''В защиту интеллигенции''. Москва, 1909, с. 119–138; первоначально опубл. в газете "Русское слово", No 111, 17 (30) мая, 1909 (in Russian) According to the theory of Dr. Vitaly Tepikin, the sociological traits usual to the intelligentsia of a society are: #advanced-for-their-time moral ideals, moral sensitivity to the neighbour, tact and gentleness in expression; #productive mental work, and in continual self-education; #patriotism based on faith in the people, and inexhaustible, self-less love for the small and the big motherlands; #inherent creativity in every stratum of the intelligentsia, and a tendency to

In 1844 Poland, the term ''inteligencja'', identifying the intellectuals of society, first was used by the philosopher

In 1844 Poland, the term ''inteligencja'', identifying the intellectuals of society, first was used by the philosopher

The Russian ''intelligentsiya'' also was a mixture of messianism and intellectual élitism, which the philosopher

The Russian ''intelligentsiya'' also was a mixture of messianism and intellectual élitism, which the philosopher

Героизм и подвижничество

'. Вехи (сборник статей о русской интеллигенции), 1909 In 1860, there were 20,000 professionals in Russia and 85,000 by 1900. Originally composed of educated nobles, the intelligentsia became dominated by ''raznochintsy'' (classless people) after 1861. In 1833, 78.9 per cent of secondary-school students were children of nobles and bureaucrats, by 1885 they were 49.1 per cent of such students. The proportion of commoners increased from 19.0 to 43.8 per cent, and the remaining percentage were the children of priests. In fear of an educated proletariat, Tsar Nicholas I limited the number of university students to 3,000 per year, yet there were 25,000 students, by 1894. Similarly the number of periodicals increased from 15 in 1855 to 140 periodical publications in 1885. The "third element" were professionals hired by

online

*Boborykin, P.D. ''Russian Intelligentsia'' In: ''Russian Thought'', 1904, # 12 (In Russian; Боборыкин П.Д. Русская интеллигенция// Русская мысль. 1904. No.12;) *Zhukovsky V. A. ''From the Diaries of Years 1827–1840'', In: ''Our Heritage,'' Moscow, #32, 1994. (In Russian; Жуковский В.А. Из дневников 1827–1840 гг. // Наше наследие. М., 1994. No.32.) ** The record dated by 2 February 1836 says: "Через три часа после этого общего бедствия ... осветился великолепный Энгельгардтов дом, и к нему потянулись кареты, все наполненные лучшим петербургским дворянством, тем, которые у нас представляют всю русскую европейскую интеллигенцию" ("After three hours after this common disaster ... the magnificent Engelhardt's house was lit up and coaches started coming, filled with the best Peterburg '' dvoryanstvo,'' the ones who represent here the best Russian European ''intelligentsia.''") The casual, i.e., no-philosophical and non-literary context, suggests that the word was in common circulation. {{Authority control Science and technology in Russia Science and technology in the Soviet Union Social groups Social class in Poland Sociology of knowledge Society of Russia Intellectualism

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

(1772–1795). Etymologically, the 19th-century Polish intellectual Bronisław Trentowski

Bronisław Ferdynand Trentowski (21 January 1808 in Opole – 16 June 1869) was a Polish " Messianist" philosopher, pedagogist, journalist and Freemason, and the chief representative of the Polish Messianist "national philosophy.""Trentowski, Broni ...

coined the term ''inteligencja'' (intellectuals) to identify and describe the university-educated and professionally active social stratum of the patriotic bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

; men and women whose intellectualism

Intellectualism is the mental perspective that emphasizes the use, the development, and the exercise of the intellect; and also identifies the life of the mind of the intellectual person. (Definition) In the field of philosophy, the term ''intell ...

would provide moral and political leadership to Poland in opposing the cultural hegemony

In Marxist philosophy, cultural hegemony is the dominance of a culturally diverse society by the ruling class who manipulate the culture of that society—the beliefs and explanations, perceptions, values, and mores—so that the worldview of t ...

of the Russian Empire.

In pre–Revolutionary (1917) Russia, the term ''intelligentsiya'' (russian: интеллигенция) identified and described the status class of university-educated people whose cultural capital — schooling, education, and intellectual enlightenment — allowed them to assume the moral initiative and the practical leadership required in the national, regional, and local politics of Russia.

In practice, the status and social function of the intelligentsia varied by society; in eastern Europe, the intellectuals were at the periphery of their societies, and thus were deprived of political influence and access to the effective levers of political power and of economic development. In western Europe the intellectuals were in the mainstream of their societies, and thus exercised cultural and political influence that granted access to the power of government office, such as the ''Bildungsbürgertum

''Bildungsbürgertum'' () is a social class that emerged in mid-18th-century Germany, as the educated social stratum of the bourgeoisie, men and women who had received an education based upon the metaphysical values of Idealism and Classical stud ...

'', the cultured bourgeoisie of Germany, and the professions in Great Britain.

Background

In a society, the ''intelligentsia'' is a status class of intellectuals whose social functions, politics, and national interests are distinct from the functions of government, commerce, and the military. In ''Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology'' (1921), the political economistMax Weber

Maximilian Karl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German sociologist, historian, jurist and political economist, who is regarded as among the most important theorists of the development of modern Western society. His ideas profo ...

applied the term ''intelligentsia'' in chronological and geographical frames of reference, such as "this Christian preoccupation with the formulation of dogmas was, in Antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

, particularly influenced by the distinctive character of ‘intelligentsia’, which was the product of Greek education", thus the ''intelligentsia'' originated as a social class of educated people created for the greater benefit of society.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Polish word and the sociologic concept of the ''inteligencja'' became a European usage to describe the social class of men and women who are the intellectuals of the countries of central and of eastern Europe; in Poland, the critical thinkers educated at university, in Russia, the nihilists

Nihilism (; ) is a philosophy, or family of views within philosophy, that rejects generally accepted or fundamental aspects of human existence, such as objective truth, knowledge, morality, values, or meaning. The term was popularized by Ivan ...

who opposed traditional values in the name of reason and progress. In the late 20th century, the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu said that the intelligentsia has two types of workers; (i) intellectual workers who create knowledge (practical and theoretic) and (ii) intellectual workers who create cultural capital. Sociologically, the Polish ''inteligencja'' translates to the ''intellectuels'' in France and the ''Gebildete'' in Germany.

European history

Karol Libelt

Karol Libelt (8 April 1807, neighborhood of Chwaliszewo in Poznań, Duchy of Warsaw - 9 June 1875, Brdowo) was a Polish philosopher, writer, political and social activist, social worker and liberal, nationalist politician, and president of the Po ...

used the term ''inteligencja'', which was the status class, composed of scholars, teachers, lawyers, and engineers, ''et al.'' as the educated people of society who provide the moral leadership required to resolve the problems of society, hence the social function of the intelligentsia is to "guide for the reason of their higher enlightenment."

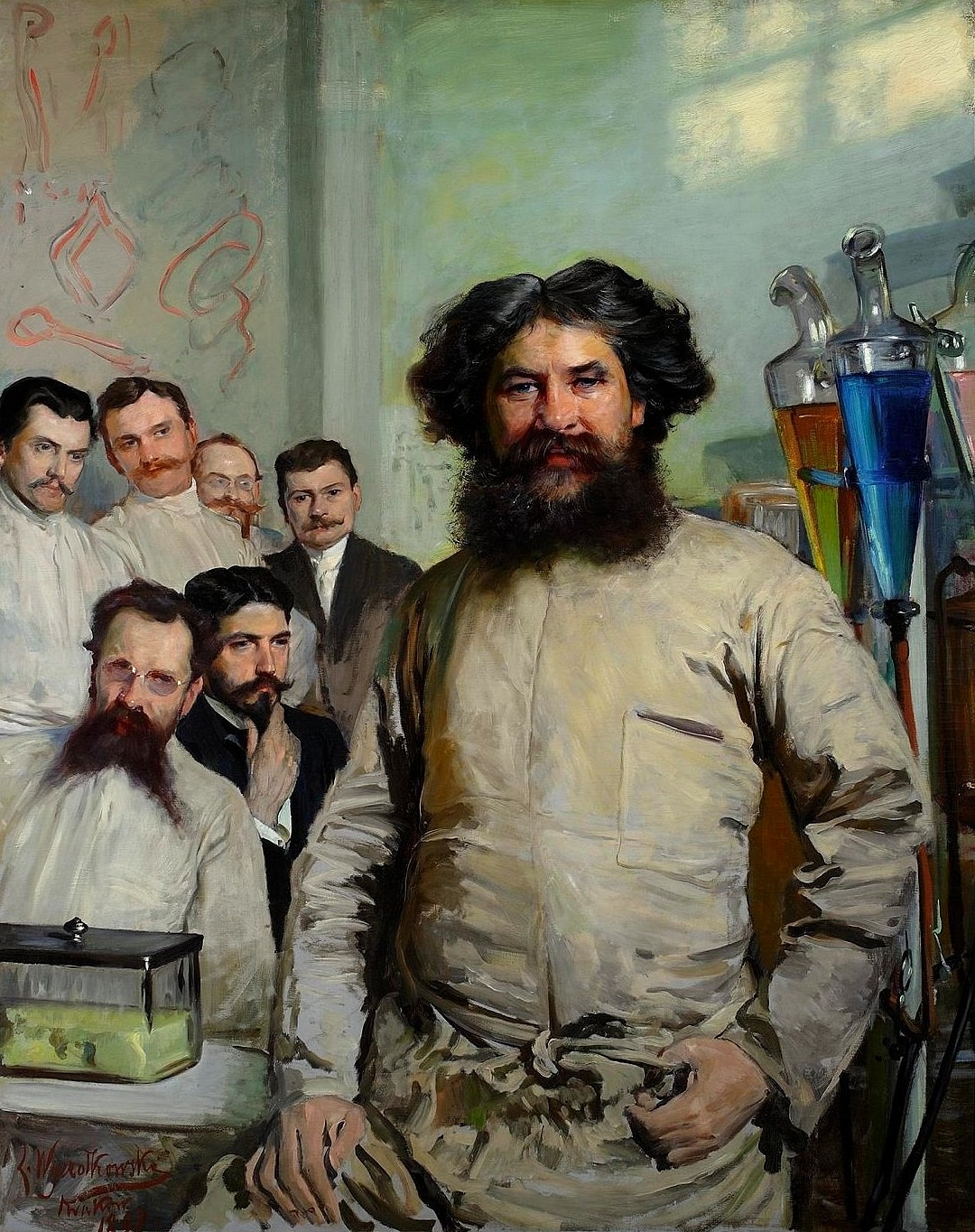

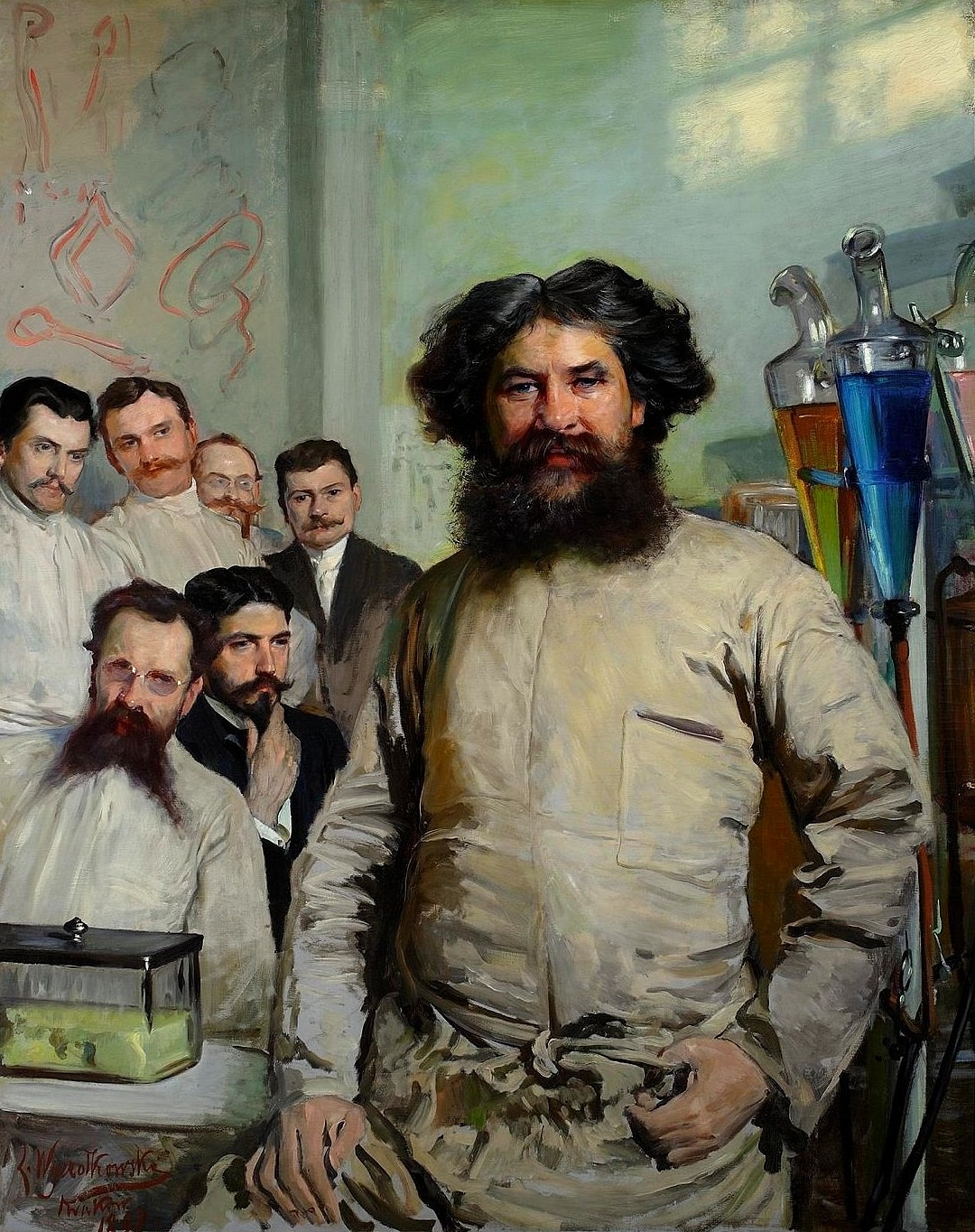

In the 1860s, the journalist Pyotr Boborykin popularised the term ''intelligentsiya'' (интеллигенция) to identify and describe the Russian social stratum of people educated at university who engage in the intellectual occupations (law, medicine, engineering, the arts) who produce the culture and the dominant ideology by which society functions.С. В. Мотин. О понятии «интеллигенция» в творчестве И. С. Аксакова и П. Д. Боборыкина

'. Известия Пензенского государственного педагогического университета им. В.Г. Белинского, 27, 2012 (in Russian)Пётр Боборыкин. ''Русская интеллигенция''. Русская мысль, 1904, № 12 (in Russian)Пётр Боборыкин.

Подгнившие "Вехи"

'. Сб. статей ''В защиту интеллигенции''. Москва, 1909, с. 119–138; первоначально опубл. в газете "Русское слово", No 111, 17 (30) мая, 1909 (in Russian) According to the theory of Dr. Vitaly Tepikin, the sociological traits usual to the intelligentsia of a society are: #advanced-for-their-time moral ideals, moral sensitivity to the neighbour, tact and gentleness in expression; #productive mental work, and in continual self-education; #patriotism based on faith in the people, and inexhaustible, self-less love for the small and the big motherlands; #inherent creativity in every stratum of the intelligentsia, and a tendency to

asceticism

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

;

#an independent personality who speaks freely;

#a critical attitude towards the government, and public condemnation of injustice;

#loyalty to principle by conscience, grace under pressure, and tendency to self-denial;

#an ambiguous perception of reality, which leads to political fickleness that sometimes becomes conservatism;

#a sense of resentment, because politics and policies went unrealised; and withdrawal from the public sphere to the in-group;

#quarrels about art, ideas, and ideology, which divide the subgroups who compose the intelligentsia.

In ''The Rise of the Intelligentsia, 1750–1831'' (2008) Maciej Janowski said that the Polish intelligentsia were the think tank of the State, intellectual servants whose progressive social and economic policies decreased the social backwardness (illiteracy) of the Polish people, and also decreased Russian political repression in partitioned Poland

Partition may refer to:

Computing Hardware

* Disk partitioning, the division of a hard disk drive

* Memory partition, a subdivision of a computer's memory, usually for use by a single job

Software

* Partition (database), the division of a ...

.

Poland

19th century

In 1844 Poland, the term ''inteligencja'', identifying the intellectuals of society, first was used by the philosopher

In 1844 Poland, the term ''inteligencja'', identifying the intellectuals of society, first was used by the philosopher Karol Libelt

Karol Libelt (8 April 1807, neighborhood of Chwaliszewo in Poznań, Duchy of Warsaw - 9 June 1875, Brdowo) was a Polish philosopher, writer, political and social activist, social worker and liberal, nationalist politician, and president of the Po ...

, which he described as a status class of people characterised by intellect

In the study of the human mind, intellect refers to, describes, and identifies the ability of the human mind to reach correct conclusions about what is true and what is false in reality; and how to solve problems. Derived from the Ancient Gree ...

and Polish nationalism; qualities of mind, character, and spirit that made them natural leaders of the modern Polish nation. That the intelligentsia were aware of their social status and of their duties to society: Educating the youth with the nationalist objective to restore the Republic of Poland; preserving the Polish language; and love of the Fatherland.

Nonetheless, the writers Stanisław Brzozowski and Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński criticised Libelt's ideological and messianic representation of a Polish republic, because it originated from the social traditionalism and reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the ''status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abse ...

conservatism that pervade the culture of Poland, and so impede socio-economic progress. Consequent to the Imperial Prussian, Austrian, Swedish and Russian Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

, the imposition of Tsarist cultural hegemony

In Marxist philosophy, cultural hegemony is the dominance of a culturally diverse society by the ruling class who manipulate the culture of that society—the beliefs and explanations, perceptions, values, and mores—so that the worldview of t ...

caused many of the political and cultural élites to participate in the Great Emigration

The Great Emigration ( pl, Wielka Emigracja) was the emigration of thousands of Poles and Lithuanians, particularly from the political and cultural élites, from 1831 to 1870, after the failure of the November Uprising of 1830–1831 and of oth ...

(1831–70).

Second World War

After the Invasion of Poland (1 September 1939), by Nazi Germany and the Soviet union, in occupied Poland each side proceeded to eliminate any possible resistance leader. In their part of occupied Poland, the Nazis began the Second World War (1939–45) with the extermination of the Polish intelligentsia, by way of the military operations of theSpecial Prosecution Book-Poland

''Special Prosecution Book-Poland'' (german: Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen, pl, Specjalna księga Polaków ściganych listem gończym) was the proscription list prepared by the Germans immediately before the onset of war, that identified more than 61, ...

, the German AB-Aktion in Poland

, location = Palmiry Forest and similar locations in occupied Poland

, date = Spring–summer 1940

, incident_type = Mass murder with automatic weapons

, perpetrators = Wehrmacht, ''Einsatzgruppen''

, participants =

, or ...

, the Intelligenzaktion, and the Intelligenzaktion Pommern

The ''Intelligenzaktion Pommern''Stefan Sutkowski (2001), ''The history of music in Poland: The Contemporary Era. 1939–1974''. Vol. 7, page 37 "...some 183 professors of the Jagiellonian University and the Academy of Mining and Foundry in Craco ...

. In their part of occupied Poland, the Soviet Union proceeded with the extermination of the Polish intelligentsia with operations such as the Katyn massacre (April-May 1940), during which university professors, physicians, lawyers, engineers, teachers, military, policeman, writers and journalists were murdered.

Russia

Imperial era

The Russian ''intelligentsiya'' also was a mixture of messianism and intellectual élitism, which the philosopher

The Russian ''intelligentsiya'' also was a mixture of messianism and intellectual élitism, which the philosopher Isaiah Berlin

Sir Isaiah Berlin (6 June 1909 – 5 November 1997) was a Russian-British social and political theorist, philosopher, and historian of ideas. Although he became increasingly averse to writing for publication, his improvised lectures and talks ...

described as follows: "The phenomenon, itself, with its historical and literally revolutionary consequences, is, I suppose, the largest, single Russian contribution to social change in the world. The concept of intelligentsia must not be confused with the notion of intellectuals. Its members thought of themselves as united, by something more than mere interest in ideas; they conceived themselves as being a dedicated order, almost a secular priesthood, devoted to the spreading of a specific attitude to life."

The Idea of Progress, which originated in Western Europe during the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century, became the principal concern of the intelligentsia by the mid-19th century; thus, progress social movements, such as the Narodniks, mostly consisted of intellectuals. The Russian philosopher Sergei Bulgakov

Sergei Nikolaevich Bulgakov (; russian: Серге́й Никола́евич Булга́ков; – 13 July 1944) was a Russian Eastern Orthodox Church, Orthodox theologian, priest, philosopher, and economist.

Biography

Early life: 1871–18 ...

said that the Russian intelligentsia was the creation of Peter, that they were the "window to Europe through which the Western air comes to us, vivifying and toxic at the same time." Moreover, Bulgakov also said that the literary critic of Westernization, Vissarion Belinsky was the spiritual father of the Russian intelligentsia.Сергей Булгаков. Героизм и подвижничество

'. Вехи (сборник статей о русской интеллигенции), 1909 In 1860, there were 20,000 professionals in Russia and 85,000 by 1900. Originally composed of educated nobles, the intelligentsia became dominated by ''raznochintsy'' (classless people) after 1861. In 1833, 78.9 per cent of secondary-school students were children of nobles and bureaucrats, by 1885 they were 49.1 per cent of such students. The proportion of commoners increased from 19.0 to 43.8 per cent, and the remaining percentage were the children of priests. In fear of an educated proletariat, Tsar Nicholas I limited the number of university students to 3,000 per year, yet there were 25,000 students, by 1894. Similarly the number of periodicals increased from 15 in 1855 to 140 periodical publications in 1885. The "third element" were professionals hired by

zemstva

A ''zemstvo'' ( rus, земство, p=ˈzʲɛmstvə, plural ''zemstva'' – rus, земства) was an institution of local government set up during the great emancipation reform of 1861 carried out in Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexander ...

. By 1900, there were 47,000 of them, most were liberal radicals.

Although Tsar Peter the Great introduced the Idea of Progress to Russia, by the 19th century, the Tsars did not recognize "progress" as a legitimate aim of the state, to the degree that Nicholas II said "How repulsive I find that word" and wished it removed from the Russian language.

Bolshevik perspective

In Russia, the Bolsheviks did not consider the status class of the ''intelligentsiya'' to be a truesocial class

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the Upper class, upper, Middle class, middle and Working class, lower classes. Membership in a social class can for ...

, as defined in Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

philosophy. In that time, the Bolsheviks used the Russian word ''prosloyka'' (stratum) to identify and define the intelligentsia as a separating layer without an inherent class character.

In the creation of post-monarchic Russia, Lenin was firmly critical of the class character of the intelligentsia, commending the growth of "the intellectual forces of the workers and the peasants" will depose the "bourgeoisie and their accomplices, intelligents, lackeys of capital who think that they are brain of the nation. In fact it is not brain, but dung". (На деле это не мозг, а говно)

The Russian Revolution of 1917 divided the intelligentsia and the social classes of Tsarist Russia. Some Russians emigrated, the political reactionaries joined the right-wing White movement for counter-revolution, some became Bolsheviks, and some remained in Russia and participated in the political system of the USSR. In reorganizing Russian society, the Bolsheviks deemed non-Bolshevik intelligentsia class enemies and expelled them from society, by way of deportation on Philosophers' ships, forced labor in the gulag, and summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes include ...

. The members of the Tsarist-era intelligentsia who remained in Bolshevik Russia (the USSR) were proletarianized. Although the Bolsheviks recognized the managerial importance of the intelligentsia to the future of Soviet Russia, the bourgeois origin of this stratum gave reason for distrust of their ideological commitment to Marxist philosophy and Bolshevik societal control.

Soviet Union

In the late Soviet Union the term "intelligentsia" acquired a formal definition of mental and cultural workers. There were subcategories of "scientific-technical intelligentsia" (научно-техническая интеллигенция) and "creative intelligentsia" (творческая интеллигенция). Between 1917 and 1941, there was a massive increase in the number of engineering graduates: from 15,000 to over 250,000.Post-Soviet period

In the post-Soviet period, the members of the former Soviet intelligentsia have displayed diverging attitudes towards the communist government. While the older generation of intelligentsia has attempted to frame themselves as victims, the younger generation, who were in their 30s when the Soviet Union collapsed, has not allocated so much space for the repressive experience in their self-narratives. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the popularity and influence of the intelligentsia has significantly declined. Therefore, it is typical for the post-Soviet intelligentsia to feel nostalgic for the last years of the Soviet Union (perestroika

''Perestroika'' (; russian: links=no, перестройка, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg) was a political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s widely associated wit ...

), which they often regard as the golden age of the intelligentsia.

Vladimir Putin has expressed his view on the social duty of intelligentsia in modern Russia.

We should all be aware of the fact that when revolutionary—not evolutionary—changes come, things can get even worse. The intelligentsia should be aware of this. And it is the intelligentsia specifically that should keep this in mind and prevent society from radical steps and revolutions of all kinds. We've had enough of it. We've seen so many revolutions and wars. We need decades of calm and harmonious development.

Mass intelligentsia

In the 20th century, from the status class term ''Intelligentsia'', sociologists derived the term ''mass intelligentsia'' to describe the populations of educated adults, with discretionary income, who pursue intellectual interests by way of book clubs and cultural associations, etc. That sociological term was made popular usage by the writerMelvyn Bragg

Melvyn Bragg, Baron Bragg, (born 6 October 1939), is an English broadcaster, author and parliamentarian. He is best known for his work with ITV as editor and presenter of ''The South Bank Show'' (1978–2010), and for the BBC Radio 4 documenta ...

, who said that mass intelligentsia conceptually explains the popularity of book clubs and literary festivals that otherwise would have been of limited intellectual interests to most people from the middle class and from the working class.

In the book ''Campus Power Struggle'' (1970), the sociologist Richard Flacks addressed the concept of mass intelligentsia:

See also

* Academia * Anti-intellectualism * College graduate * Philippine ilustrado * Creative class *Obrazovanshchina

Obrazovanshchina (russian: образованщина, 'educationdom', 'educaties', 'smatterers') is a Russian ironical, derogatory term for a category of people with superficial education who lack the higher ethics of an educated person.

The ter ...

*Organic intellectual

In Marxist philosophy, cultural hegemony is the dominance of a culturally diverse society by the ruling class who manipulate the culture of that society—the beliefs and explanations, perceptions, values, and mores—so that the worldview of t ...

References

Further reading

* Roach, John. "Liberalism and the Victorian Intelligentsia." ''Cambridge Historical Journal'' 13#1 (1957): 58–81online

*Boborykin, P.D. ''Russian Intelligentsia'' In: ''Russian Thought'', 1904, # 12 (In Russian; Боборыкин П.Д. Русская интеллигенция// Русская мысль. 1904. No.12;) *Zhukovsky V. A. ''From the Diaries of Years 1827–1840'', In: ''Our Heritage,'' Moscow, #32, 1994. (In Russian; Жуковский В.А. Из дневников 1827–1840 гг. // Наше наследие. М., 1994. No.32.) ** The record dated by 2 February 1836 says: "Через три часа после этого общего бедствия ... осветился великолепный Энгельгардтов дом, и к нему потянулись кареты, все наполненные лучшим петербургским дворянством, тем, которые у нас представляют всю русскую европейскую интеллигенцию" ("After three hours after this common disaster ... the magnificent Engelhardt's house was lit up and coaches started coming, filled with the best Peterburg '' dvoryanstvo,'' the ones who represent here the best Russian European ''intelligentsia.''") The casual, i.e., no-philosophical and non-literary context, suggests that the word was in common circulation. {{Authority control Science and technology in Russia Science and technology in the Soviet Union Social groups Social class in Poland Sociology of knowledge Society of Russia Intellectualism