Indian Reorganization Act on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of June 18, 1934, or the Wheeler–Howard Act, was U.S. federal legislation that dealt with the status of American Indians in the United States. It was the centerpiece of what has been often called the "Indian New Deal".

The Act also restored to Indians the management of their assets—land and mineral rights—and included provisions intended to create a sound economic foundation for the residents of

At the time the Act passed, it was United States policy to eliminate Indian reservations, dividing the communal territory and allotting 160-acre plots to individual heads of households, to be owned in severalty. Before allotment, reservation territory was not owned in the usual European-American sense, but was reserved for the benefit of entire Indian tribes. The communal benefits were apportioned to tribe members according to tribal law and custom. Generally, Indians held the land in a communal fashion. Non-Indians were not allowed to own land on reservations, which limited the dollar value of the land since there was a smaller market capable of buying it.

The process of allotment started with the General Allotment Act of 1887. By 1934, two-thirds of Indian land had converted to traditional private ownership (i.e., it was owned in

At the time the Act passed, it was United States policy to eliminate Indian reservations, dividing the communal territory and allotting 160-acre plots to individual heads of households, to be owned in severalty. Before allotment, reservation territory was not owned in the usual European-American sense, but was reserved for the benefit of entire Indian tribes. The communal benefits were apportioned to tribe members according to tribal law and custom. Generally, Indians held the land in a communal fashion. Non-Indians were not allowed to own land on reservations, which limited the dollar value of the land since there was a smaller market capable of buying it.

The process of allotment started with the General Allotment Act of 1887. By 1934, two-thirds of Indian land had converted to traditional private ownership (i.e., it was owned in

Department of Justice The U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) sought a U.S. Supreme Court review. But, as DOI was implementing new regulations related to land trusts, the agency asked the Court to remand the case to the lower court for reconsideration with the decision based on the new regulations. The U.S. Supreme Court granted the DOI's petition, vacated the lower court's ruling, and remanded the case back to the lower court. Justices Antonin Scalia, Sandra Day O'Connor, and Clarence Thomas dissented, stating that " e decision today—to grant, vacate, and remand in light of the Government's changed position—is both unprecedented and inexplicable." They went on, " at makes today's action inexplicable as well as unprecedented is the fact that the Government's change of legal position does not even purport to be applicable to the present case." Seven months after the Supreme Court's decision to grant, vacate, and remand, the DOI removed the land in question from trust. In 1997, the Lower Brulé Sioux submitted an amended trust application to the DOI, requesting that the United States take the of land into trust on the Tribe's behalf. South Dakota challenged this in 2004 in district court, which upheld DOI's authority to take the land in trust. The state appealed to the Eighth Circuit, but when the court reexamined the constitutionality issue, it upheld the constitutionality of Section 5 in agreement with the lower court. The U.S. Supreme Court denied the State's petition for ''certiorari''. Since then, district and circuit courts have rejected claims of non-delegation by states. The Supreme Court refused to hear the issue in 2008. In 2008 (before the U.S. Supreme Court heard the ''Carcieri'' case below), in ''MichGO v Kempthorne'', Judge Janice Rogers Brown of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals wrote a dissent stating that she would have struck down key provisions of the IRA. Of the three circuit courts to address the IRA's constitutionality, Judge Brown is the only judge to dissent on the IRA's constitutionality. The majority opinion upheld its constitutionality. The U.S. Supreme Court did not accept the ''MichGO'' case for review, thus keeping the previous precedent in place. Additionally, the First, Eighth, and Tenth Circuits of the U.S. Court of Appeals have upheld the constitutionality of the IRA. In 2008, ''Carcieri v Kempthorne'' was argued before the U.S. Supreme Court; the Court ruled on it in 2009, with the decision called ''

in JSTOR

* Kelly, L. C. ''The Assault on Assimilation: John Collier and the Origins of Indian Policy Reform.'' (University of New Mexico Press, 1963) * Kelly, William Henderson, ed. ''Indian Affairs and the Indian Reorganization Act: The Twenty Year Record'' (University of Arizona, 1954) * Koppes, Clayton R. "From New Deal to Termination: Liberalism and Indian Policy, 1933-1953." ''Pacific Historical Review'' (1977): 543–566

in JSTOR

* Parman, Donald Lee. ''The Navajos and the New Deal'' (Yale University Press, 1976) * Philp, K. R. ''John Collier and the American Indian, 1920–1945.'' (Michigan State University Press, 1968) * Philp, K. R. '' John Collier's Crusade for Indian Reform, 1920-1954.'' (University of Arizona Press, 1977) * Philp, Kenneth R. "Termination: a legacy of the Indian new deal." ''Western Historical Quarterly'' (1983): 165–180

in JSTOR

* Rusco, Elmer R. ''A fateful time: the background and legislative history of the Indian Reorganization Act'' (University of Nevada Press, 2000) * Taylor, Graham D. ''The New Deal and American Indian Tribalism: The Administration of the Indian Reorganization Act, 1934-45'' (U of Nebraska Press, 1980)

Indian Reorganization ActPDFdetails

as amended in the

Indian Reorganization Act - Information & Video

- Chickasaw.TV {{Authority control United States federal Native American legislation United States federal Indian policy Aboriginal title in the United States Native American law Native American history New Deal legislation 1934 in American law 1954 in American politics Assimilation of indigenous peoples of North America History of indigenous peoples of North America

Indian reservation

An Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a federally recognized Native American tribal nation whose government is accountable to the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs and not to the state government in which it ...

s. Total U.S. spending on Indians averaged $38 million a year in the late 1920s, dropping to an all-time low of $23 million in 1933, and reaching $38 million in 1940.

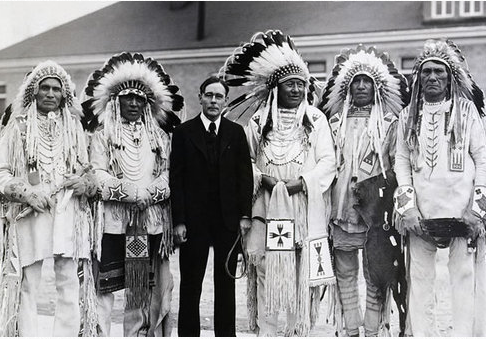

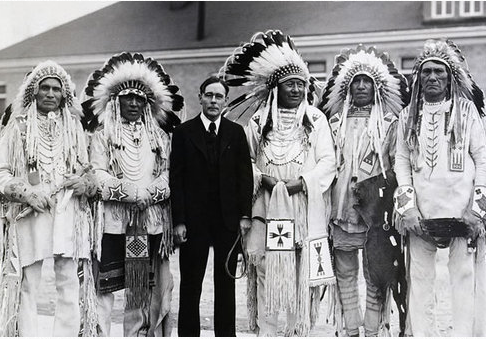

The IRA was the most significant initiative of John Collier John Collier may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*John Collier (caricaturist) (1708–1786), English caricaturist and satirical poet

*John Payne Collier (1789–1883), English Shakespearian critic and forger

*John Collier (painter) (1850–1934), ...

, who was President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and A ...

(BIA) from 1933 to 1945. He had long studied Indian issues and worked for change since the 1920s, particularly with the American Indian Defense Association. He intended to reverse the assimilationist policies that had resulted in considerable damage to American Indian cultures and to provide a means for American Indians to re-establish sovereignty and self-government, reduce the losses of reservation lands, and build economic self-sufficiency. He believed that Indian traditional culture was superior to that of modern America and thought it worthy of emulation. His proposals were considered highly controversial, as numerous powerful interests had profited from the sale and management of Native lands. Congress revised Collier's proposals and preserved oversight of tribes and reservations by the Bureau of Indian Affairs within the Department of Interior. Felix S. Cohen

Felix Solomon Cohen (July 3, 1907 – October 19, 1953) was an American lawyer and scholar who made a lasting mark on legal philosophy and fundamentally shaped federal Indian law and policy.

Biography

Felix S. Cohen was born in Manhattan, New Y ...

, an official at the Department of the Interior Solicitor's Office, was another significant architect of the Indian New Deal who helped draft the 1934 act.

The self-government provisions would automatically go into effect for a tribe unless a clear majority of the eligible Indians voted it down.

History

Background

At the time the Act passed, it was United States policy to eliminate Indian reservations, dividing the communal territory and allotting 160-acre plots to individual heads of households, to be owned in severalty. Before allotment, reservation territory was not owned in the usual European-American sense, but was reserved for the benefit of entire Indian tribes. The communal benefits were apportioned to tribe members according to tribal law and custom. Generally, Indians held the land in a communal fashion. Non-Indians were not allowed to own land on reservations, which limited the dollar value of the land since there was a smaller market capable of buying it.

The process of allotment started with the General Allotment Act of 1887. By 1934, two-thirds of Indian land had converted to traditional private ownership (i.e., it was owned in

At the time the Act passed, it was United States policy to eliminate Indian reservations, dividing the communal territory and allotting 160-acre plots to individual heads of households, to be owned in severalty. Before allotment, reservation territory was not owned in the usual European-American sense, but was reserved for the benefit of entire Indian tribes. The communal benefits were apportioned to tribe members according to tribal law and custom. Generally, Indians held the land in a communal fashion. Non-Indians were not allowed to own land on reservations, which limited the dollar value of the land since there was a smaller market capable of buying it.

The process of allotment started with the General Allotment Act of 1887. By 1934, two-thirds of Indian land had converted to traditional private ownership (i.e., it was owned in fee simple

In English law, a fee simple or fee simple absolute is an estate in land, a form of freehold ownership. A "fee" is a vested, inheritable, present possessory interest in land. A "fee simple" is real property held without limit of time (i.e., perm ...

). Most of that had been sold by Indian allottees, often because they could not pay local taxes on the lands they were newly responsible for. The IRA provided a mechanism for the recovery of land that had been previously sold, including land that had been sold to tribal Indians. They would lose individual property under the law.

John Collier was appointed Commissioner of the Indian Bureau (it is now called the Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and A ...

, BIA) in April 1933 by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. He had the full support of his boss, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, who was also an expert on Indian issues.

The federal government held land in trust for many tribes. Numerous claims cases had been presented to Congress because of failures in the government's management of such lands. There were particular grievances and claims due to the government's failure to provide for sustainable forestry. The Indian Claims Act of 1946 included a requirement that the Interior Department manage Indian forest resources "on the principle of sustained-yield management." Representative Edgar Howard of Nebraska, co-sponsor of the Act and Chairman of the House Committee on Indian Affairs, explained that the purpose of the provision was "to assure a proper and permanent management of the Indian Forest" under modern sustained-yield methods to "assure that the Indian forests will be permanently productive and will yield continuous revenues to the tribes."

Implementation and results

The act slowed the practice of allotting communal tribal lands to individual tribal members. It did not restore to Indians land that had already been patented to individuals. However, much land at that time was still unallotted or allotted to an individual but still held in trust for that individual by the U.S. government. Because the Act did not disturb existing private ownership of Indian reservation lands, it left reservations as acheckerboard

A checkerboard (American English) or chequerboard (British English; see spelling differences) is a board of checkered pattern on which checkers (also known as English draughts) is played. Most commonly, it consists of 64 squares (8×8) of altern ...

of tribal or individual trust and fee land, which remains the case today.

However, the Act also allowed the U.S. to purchase some of the fee land and restore it to tribal trust status. Due to the Act and other federal courts and government actions, more than two million acres (8,000 km2) of land were returned to various tribes in the first 20 years after passage.

In 1954, the United States Department of the Interior (DOI) began implementing the termination and relocation phases of the Act, which had been added by Congress. These provisions resulted from the continuing interest of some members of Congress in having American Indians assimilate into the majority society. Among other effects, termination resulted in the legal dismantling of 61 tribal nations within the United States and ending their recognized relationships with the federal government. This also ended the eligibility of the tribal nations and their members for various government programs to assist American Indians. Of the "Dismantled Tribes" 46 regained their legal status as indigenous communities.

Constitutional challenges

Since the late 20th century and the rise of Indianactivism

Activism (or Advocacy) consists of efforts to promote, impede, direct or intervene in Social change, social, Political campaign, political, economic or Natural environment, environmental reform with the desire to make Social change, changes i ...

over sovereignty issues, as well as many tribes' establishment of casino gambling on reservations as a revenue source, the U.S. Supreme Court has been repeatedly asked to address the IRA's constitutionality. A controversial provision of the Act allows the U.S. government to acquire non-Indian land (by voluntary transfer) and convert it to Indian land ("take it into trust"). In doing so, the U.S. government partially removes the land from the state's jurisdiction, allowing activities like casino gambling on the land for the first time. It also exempts the land from state property and other state taxes. Consequently, many state or local governments opposed the IRA and filed lawsuits challenging its constitutionality.

In 1995, South Dakota challenged the authority of the Interior Secretary

The United States secretary of the interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior. The secretary and the Department of the Interior are responsible for the management and conservation of most federal land along with natu ...

, under the IRA, to take of land into trust on behalf of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe

The Lower Brulé Indian Reservation is an Indian reservation that belongs to the Lower Brulé Lakota Tribe. It is located on the west bank of the Missouri River in Lyman and Stanley counties in central South Dakota in the United States. It is ...

(based on the Lower Brule Indian Reservation) in ''South Dakota v. United States Dep't of the Interior'', 69 F.3d 878, 881-85 (8th Cir. 1995). The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals

The United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit (in case citations, 8th Cir.) is a United States federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the following United States district courts:

* Eastern District of Arkansas

* Western Distr ...

found Section 5 of the IRA to be unconstitutional, ruling that it violated the non-delegation doctrine and that the Secretary of Interior did not have the authority to take the land into trust.''South Dakota v. Dept. of Interior'' (1995)Department of Justice The U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) sought a U.S. Supreme Court review. But, as DOI was implementing new regulations related to land trusts, the agency asked the Court to remand the case to the lower court for reconsideration with the decision based on the new regulations. The U.S. Supreme Court granted the DOI's petition, vacated the lower court's ruling, and remanded the case back to the lower court. Justices Antonin Scalia, Sandra Day O'Connor, and Clarence Thomas dissented, stating that " e decision today—to grant, vacate, and remand in light of the Government's changed position—is both unprecedented and inexplicable." They went on, " at makes today's action inexplicable as well as unprecedented is the fact that the Government's change of legal position does not even purport to be applicable to the present case." Seven months after the Supreme Court's decision to grant, vacate, and remand, the DOI removed the land in question from trust. In 1997, the Lower Brulé Sioux submitted an amended trust application to the DOI, requesting that the United States take the of land into trust on the Tribe's behalf. South Dakota challenged this in 2004 in district court, which upheld DOI's authority to take the land in trust. The state appealed to the Eighth Circuit, but when the court reexamined the constitutionality issue, it upheld the constitutionality of Section 5 in agreement with the lower court. The U.S. Supreme Court denied the State's petition for ''certiorari''. Since then, district and circuit courts have rejected claims of non-delegation by states. The Supreme Court refused to hear the issue in 2008. In 2008 (before the U.S. Supreme Court heard the ''Carcieri'' case below), in ''MichGO v Kempthorne'', Judge Janice Rogers Brown of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals wrote a dissent stating that she would have struck down key provisions of the IRA. Of the three circuit courts to address the IRA's constitutionality, Judge Brown is the only judge to dissent on the IRA's constitutionality. The majority opinion upheld its constitutionality. The U.S. Supreme Court did not accept the ''MichGO'' case for review, thus keeping the previous precedent in place. Additionally, the First, Eighth, and Tenth Circuits of the U.S. Court of Appeals have upheld the constitutionality of the IRA. In 2008, ''Carcieri v Kempthorne'' was argued before the U.S. Supreme Court; the Court ruled on it in 2009, with the decision called ''

Carcieri v. Salazar

''Carcieri v. Salazar'', 555 U.S. 379 (2009), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the federal government could not take land into trust that was acquired by the Narragansett Tribe in the late 20th century, as it wa ...

''. In 1991, the Narragansett Indian tribe bought of land. They requested that the DOI take it into trust, which the agency did in 1998, thus exempting it from many state laws. The State was concerned that the tribe would open a casino or tax-free business on the land and sued to block the transfer. The state argued that the IRA did not apply because the Narragansett was not "now under federal jurisdiction" as of 1934, as distinguished from "federally recognized." In fact, the Narragansett had been placed under Rhode Island guardianship since 1709. In 1880, the tribe was illegally pressured into relinquishing its tribal authority to Rhode Island. Some historians disagree that the action was illegal because, although not sanctioned by Congress, it was "desired" by the tribe members. The tribe did not receive federal recognition until 1983, after the 1934 passage of the IRA. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed with the State.

In a challenge to the U.S. DOI's decision to take land into trust for the Oneida Indian Nation in present-day New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, Upstate Citizens for Equality Upstate Citizens for Equality (UCE) was a citizens' rights group based in Verona, New York, that opposed Oneida Indian Nation (OIN) land claims, the Turning Stone Resort Casino, the OIN's application to the US Interior Department to place into fede ...

(UCE), New York, Oneida County, Madison County, the town of Verona, the town of Vernon, and others argued that the IRA is unconstitutional. Judge Kahn dismissed UCE's complaint, including the failed theory that the IRA is unconstitutional, on the basis of longstanding and settled law on this issue. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the dismissal.

Approval by tribes

Section 18 of the IRA required that members of the affected Indian nation or tribe vote on whether to accept it within one year of the effective date of the act (25 U.S.C. 478) and had to approve it by a majority. There was confusion about who should be allowed to vote on creating new governments, as many non-Indians lived on reservations and many Indians owned no land there, and also over the effect of abstentions. Under the voting rules, abstentions were counted as yes votes, but inOglala Lakota

The Oglala (pronounced , meaning "to scatter one's own" in Lakota language) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota people, Dakota, make up the Sioux, Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A majority ...

culture, for example, abstention had traditionally equaled a no vote. The resulting confusion caused disputes on many reservations about the results.

When the final results were in, 172 tribes had accepted the act, and 75 had rejected it. The largest tribe, the Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

, had been badly hurt by the federal Navajo Livestock Reduction

The Navajo Livestock Reduction was imposed by the United States government upon the Navajo Nation in the 1930s, during the Great Depression. The reduction of herds was justified at the time by stating that grazing areas were becoming eroded and ...

Program, which took away half their livestock and jailed dissenters. They strongly opposed the act, the chief promoter John Collier, and the entire Indian New Deal. Historian Brian Dippie notes that the Indian Rights Association denounced Collier as a "dictator" and accused him of a "near reign of terror" on the Navajo reservation. Dippie adds, " became an object of 'burning hatred' among the very people whose problems so preoccupied him."

Legacy

Historians have mixed reactions to the Indian New Deal. Many praise Collier's energy and his initiative. Kenneth R. Philp praised Collier's Indian New Deal for protecting Indian freedom to engage in traditional religious practices, obtaining additional relief money for reservations, providing a structure for self-government, and enlisting the help of anthropologists who respected traditional cultures. However, he concludes that the Indian New Deal was unable to stimulate economic progress, nor did it provide a usable structure for Indian politics. Philp argues these failures gave ammunition to the return to the previous policy of termination that took place after Collier resigned in 1945. In surveying the scholarly literature, E. A. Schwartz concludes that there is: :a near consensus among historians of the Indian New Deal that Collier temporarily rescued Indian communities from federal abuses and helped Indian people survive the Depression but also damaged Indian communities by imposing his own social and political ideas on them. Collier's reputation among the Indians was mixed—praised by some, vilified by others. He antagonized theNavajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

, the largest tribe, as well as the Seneca people

The Seneca () ( see, Onödowáʼga:, "Great Hill People") are a group of indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous Iroquoian-speaking people who historically lived south of Lake Ontario, one of the five Great Lakes in North America. Their n ...

, Iroquois, and many others. Anthropologists criticized him for not recognizing the diversity of Native American lifestyles. Hauptman argues that his emphasis on Northern Pueblo arts and crafts and the uniformity of his approach to all tribes are partly explained by his belief that his tenure as Commissioner would be short, meaning that packaging large, lengthy legislative reforms seemed politically necessary.

The Reorganization Act was wide-ranging legislation authorizing tribal self-rule under federal supervision, ending land allotment, and generally promoting measures to enhance tribes and encourage education.

Having described the American society as "physically, religiously, socially, and aesthetically shattered, dismembered, directionless", Collier was later criticized for his romantic views about the moral superiority of traditional society as opposed to modernity. Philp says after his experience at the Taos Pueblo, Collier "made a lifelong commitment to preserve tribal community life because it offered a cultural alternative to modernity....His romantic stereotyping of Indians often did not fit the reality of contemporary tribal life."

The act has helped conserve the communal tribal land bases. Collier supporters blame Congress for altering the legislation proposed by Collier, so that it has not been as successful as possible. On many reservations, its provisions exacerbated longstanding differences between traditionals and those who had adopted more European-American ways. Many Native Americans believe their traditional systems of government were better for their culture.William Canby, ''American Indian Law'' (2004) p 25.

See also

* Cultural assimilation of Native Americans *Henry Roe Cloud

Henry Roe Cloud (December 28, 1884 – February 9, 1950) was a Ho-Chunk Native American, enrolled in the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska, who served as an educator, college administrator, U.S. federal government official (in the Office of Indian Aff ...

* Native Americans in the United States

* Navajo Livestock Reduction

The Navajo Livestock Reduction was imposed by the United States government upon the Navajo Nation in the 1930s, during the Great Depression. The reduction of herds was justified at the time by stating that grazing areas were becoming eroded and ...

* Totem pole

Footnotes

Sources

* * *Further reading

* Blackman, Jon S. ''Oklahoma's Indian New Deal.'' (University of Oklahoma Press, 2013) * Clemmer, Richard O. "Hopis, Western Shoshones, and Southern Utes: Three Different Responses to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934." ''American Indian culture and research journal'' (1986) 10#2: 15–40. * Kelly, Lawrence C. "The Indian Reorganization Act: The Dream and the Reality." ''Pacific Historical Review'' (1975): 291–312in JSTOR

* Kelly, L. C. ''The Assault on Assimilation: John Collier and the Origins of Indian Policy Reform.'' (University of New Mexico Press, 1963) * Kelly, William Henderson, ed. ''Indian Affairs and the Indian Reorganization Act: The Twenty Year Record'' (University of Arizona, 1954) * Koppes, Clayton R. "From New Deal to Termination: Liberalism and Indian Policy, 1933-1953." ''Pacific Historical Review'' (1977): 543–566

in JSTOR

* Parman, Donald Lee. ''The Navajos and the New Deal'' (Yale University Press, 1976) * Philp, K. R. ''John Collier and the American Indian, 1920–1945.'' (Michigan State University Press, 1968) * Philp, K. R. '' John Collier's Crusade for Indian Reform, 1920-1954.'' (University of Arizona Press, 1977) * Philp, Kenneth R. "Termination: a legacy of the Indian new deal." ''Western Historical Quarterly'' (1983): 165–180

in JSTOR

* Rusco, Elmer R. ''A fateful time: the background and legislative history of the Indian Reorganization Act'' (University of Nevada Press, 2000) * Taylor, Graham D. ''The New Deal and American Indian Tribalism: The Administration of the Indian Reorganization Act, 1934-45'' (U of Nebraska Press, 1980)

Primary sources

* Deloria, Vine, ed. ''The Indian Reorganization Act: Congresses and Bills'' (University of Oklahoma Press, 2002)External links

Indian Reorganization Act

as amended in the

GPO GPO may refer to:

Government and politics

* General Post Office, Dublin

* General Post Office, in Britain

* Social Security Government Pension Offset, a provision reducing benefits

* Government Pharmaceutical Organization, a Thai state enterpris ...

br>Statute Compilations collectionIndian Reorganization Act - Information & Video

- Chickasaw.TV {{Authority control United States federal Native American legislation United States federal Indian policy Aboriginal title in the United States Native American law Native American history New Deal legislation 1934 in American law 1954 in American politics Assimilation of indigenous peoples of North America History of indigenous peoples of North America