Indian Territories on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the

Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land within the

Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land within the

These re-written treaties included provisions for a territorial legislature with proportional representation from various tribes. In time, the Indian Territory was reduced to what is now Oklahoma. The Oklahoma organic act, Organic Act of 1890 reduced Indian Territory to the lands occupied by the Five Civilized Tribes and the Tribes of the

In 1803 the United States of America agreed to purchase

In 1803 the United States of America agreed to purchase

The

The

Many of the tribes forcibly relocated to Indian Territory were from

Many of the tribes forcibly relocated to Indian Territory were from  Between 1814 and 1840, the Five Civilized Tribes had gradually ceded most of their lands in the Southeast section of the US through a series of treaties. The southern part of Indian Country (what eventually became the State of Oklahoma) served as the destination for the policy of Indian removal, a policy pursued intermittently by

Between 1814 and 1840, the Five Civilized Tribes had gradually ceded most of their lands in the Southeast section of the US through a series of treaties. The southern part of Indian Country (what eventually became the State of Oklahoma) served as the destination for the policy of Indian removal, a policy pursued intermittently by  The Five Civilized Tribes established tribal capitals in the following towns:

*

The Five Civilized Tribes established tribal capitals in the following towns:

*

The

The  The Illinois Potawatomi moved to present-day Nebraska and the Indiana Potawatomi moved to present-day

The Illinois Potawatomi moved to present-day Nebraska and the Indiana Potawatomi moved to present-day

Western Indian Territory is part of the Southern Plains and is the ancestral home of the

Western Indian Territory is part of the Southern Plains and is the ancestral home of the

in JSTOR

* Minges, Patrick. ''Slavery in the Cherokee Nation: The Keetowah Society and the Defining of a People, 1855–1867'' (Routledge, 2003) * Reese, Linda Williams. ''Trail Sisters: Freedwomen in Indian Territory, 1850–1890'' (Texas Tech University Press; 2013), 186 pages; STUDIES black women held as slaves by the Cherokee, Choctaw, and other Indians * Smith, Troy. "The Civil War Comes to Indian Territory", '' Civil War History'' (September 2013), 59#3, pp. 279–319

* Wickett, Murray R. ''Contested Territory: Whites, Native Americans and African Americans in Oklahoma, 1865–1907'' (Louisiana State University Press, 2000)

Twin Territories: Oklahoma Territory – Indian Territory

* ttps://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/fed-indian-policy/ High resolution maps and other itemsat the National Archives

See 1890s photographs of Native Americans in Oklahoma Indian Territory

hosted by th

Portal to Texas History

* ttps://library.okstate.edu/search-and-find/collections/digital-collections/oklahoma-digital-maps-collection/ Oklahoma Digital Maps Collection* * * {{Authority control Former organized territories of the United States Cherokee Nation (1794–1907) Pre-statehood history of Oklahoma Native American history of Oklahoma United States and Native American treaties Cherokee-speaking countries and territories Arkansas Territory Southern United States 1834 establishments in the United States 1907 disestablishments in the United States . . . 19th-century establishments in Oklahoma 20th-century disestablishments in Oklahoma 19th century in Oklahoma 20th century in Oklahoma Choctaw Western (genre) staples and terminology

United States Government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title

Aboriginal title is a common law doctrine that the land rights of indigenous peoples to customary tenure persist after the assumption of sovereignty under settler colonialism. The requirements of proof for the recognition of aboriginal title ...

to their land as a sovereign independent state. In general, the tribes ceded land they occupied in exchange for land grants

A land grant is a gift of real estate—land or its use privileges—made by a government or other authority as an incentive, means of enabling works, or as a reward for services to an individual, especially in return for military service. Grants ...

in 1803. The concept of an Indian Territory was an outcome of the US federal government's 18th- and 19th-century policy of Indian removal. After the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

(1861–1865), the policy of the US government was one of assimilation

Assimilation may refer to:

Culture

*Cultural assimilation, the process whereby a minority group gradually adapts to the customs and attitudes of the prevailing culture and customs

**Language shift, also known as language assimilation, the progre ...

.

The term ''Indian Reserve

In Canada, an Indian reserve (french: réserve indienne) is specified by the ''Indian Act'' as a "tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty,

that has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band."

Indi ...

'' describes lands the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English ...

set aside for Indigenous tribes between the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. The ...

and the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it ...

in the time before the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

(1775–1783).

Indian Territory later came to refer to an unorganized territory Unorganized territory may refer to:

* An unincorporated area in any number of countries

* One of the current or former territories of the United States that has not had a government "organized" with an "organic act" by the U.S. Congress

* Unorganiz ...

whose general borders were initially set by the Nonintercourse Act

The Nonintercourse Act (also known as the Indian Intercourse Act or the Indian Nonintercourse Act) is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set Amerindian boundaries of re ...

of 1834, and was the successor to the remainder of the Missouri Territory

The Territory of Missouri was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 4, 1812, until August 10, 1821. In 1819, the Territory of Arkansas was created from a portion of its southern area. In 1821, a southe ...

after Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

received statehood. The borders of Indian Territory were reduced in size as various Organic Acts were passed by Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

to create incorporated territories of the United States. The 1907 Oklahoma Enabling Act

The Enabling Act of 1906, in its first part, empowered the people residing in Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory to elect delegates to a state constitutional convention and subsequently to be admitted to the union as a single state.

The act, ...

created the single state of Oklahoma by combining Oklahoma Territory

The Territory of Oklahoma was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 2, 1890, until November 16, 1907, when it was joined with the Indian Territory under a new constitution and admitted to the Union as ...

and Indian Territory, ending the existence of an unorganized unincorporated independent Indian Territory as such. Before Oklahoma statehood, Indian Territory from 1890 onwards consisted of the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

, Choctaw, Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classifi ...

, Creek

A creek in North America and elsewhere, such as Australia, is a stream that is usually smaller than a river. In the British Isles it is a small tidal inlet.

Creek may also refer to:

People

* Creek people, also known as Muscogee, Native Americans

...

and Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

tribes and their territorial holdings.

Indian reservations remain within the boundaries of US states, but largely exempt from state jurisdiction. The term '' Indian country'' is used to signify lands under the control of Native nations, including Indian reservations, trust lands on Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area

Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area is a statistical entity identified and delineated by federally recognized American Indian tribes in Oklahoma as part of the U.S. Census Bureau's 2010 Census and ongoing American Community Survey.

Many of thes ...

, or, more casually, to describe anywhere large numbers of Native Americans live.

Description and geography

Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land within the

Indian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land within the United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territor ...

reserved for the forced re-settlement of Native Americans. Therefore, it was not a traditional territory for the tribes settled upon it. The general borders were set by the Indian Intercourse Act

The Nonintercourse Act (also known as the Indian Intercourse Act or the Indian Nonintercourse Act) is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set Amerindian boundaries of re ...

of 1834. The territory was located in the Central United States

The Central United States is sometimes conceived as between the Eastern and Western as part of a three-region model, roughly coincident with the U.S. Census' definition of the Midwestern United States plus the western and central portions ...

.

While Congress passed several Organic Act

In United States law, an organic act is an act of the United States Congress that establishes a territory of the United States and specifies how it is to be governed, or an agency to manage certain federal lands. In the absence of an orga ...

s that provided a path for statehood for much of the original Indian Country, Congress never passed an Organic Act for the Indian Territory. Indian Territory was never an organized incorporated territory of the United States

The territory of the United States and its overseas possessions has evolved over time, from the colonial era to the present day. It includes formally organized territories, proposed and failed states, unrecognized breakaway states, internation ...

. In general, tribes could not sell land to non-Indians (''Johnson v. M'Intosh

''Johnson v. M'Intosh'', 21 U.S. (7 Wheat.) 543 (1823), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that held that private citizens could not purchase lands from Native Americans. As the facts were recited by Chief Justice John Marshall, th ...

''). Treaties with the tribes restricted entry of non-Indians into tribal areas; Indian tribes were largely self-governing, were suzerain

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

nations, with established tribal governments and well established cultures. The region never had a formal government until after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

.

After the Civil War, the Southern Treaty Commission re-wrote treaties with tribes that sided with the Confederacy

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between ...

, reducing the territory of the Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

and providing land to resettle Plains Indians

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) o ...

and tribes of the Midwestern United States

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. I ...

.Pennington, William D. ''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture''. "Reconstruction Treaties." Retrieved February 16, 201These re-written treaties included provisions for a territorial legislature with proportional representation from various tribes. In time, the Indian Territory was reduced to what is now Oklahoma. The Oklahoma organic act, Organic Act of 1890 reduced Indian Territory to the lands occupied by the Five Civilized Tribes and the Tribes of the

Quapaw Indian Agency The Quapaw Indian Agency was a territory that included parts of the present-day Oklahoma counties of Ottawa and Delaware. Established in the late 1830s as part of lands allocated to the Cherokee Nation, this area was later leased by the federal gov ...

(at the borders of Kansas and Missouri). The remaining western portion of the former Indian Territory became the Oklahoma Territory

The Territory of Oklahoma was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 2, 1890, until November 16, 1907, when it was joined with the Indian Territory under a new constitution and admitted to the Union as ...

.

The Oklahoma organic act applied the laws of Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the so ...

to the incorporated territory

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions overseen by the federal government of the United States. The various American territories differ from the U.S. states and tribal reservations as they are not sover ...

of Oklahoma Territory, and the laws of Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the ...

to the still unincorporated Unincorporated may refer to:

* Unincorporated area, land not governed by a local municipality

* Unincorporated entity, a type of organization

* Unincorporated territories of the United States, territories under U.S. jurisdiction, to which Congress ...

Indian Territory, since for years the federal U.S. District Court on the eastern borderline in Ft. Smith, Arkansas

Fort Smith is the third-largest city in Arkansas and one of the two county seats of Sebastian County. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 89,142. It is the principal city of the Fort Smith, Arkansas–Oklahoma Metropolitan Statistical Are ...

had criminal and civil jurisdiction over the Territory.

History

Indian Reserve and Louisiana Purchase

The concept of an Indian territory is the successor to the BritishIndian Reserve

In Canada, an Indian reserve (french: réserve indienne) is specified by the ''Indian Act'' as a "tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty,

that has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band."

Indi ...

, a British America

British America comprised the colonial territories of the English Empire, which became the British Empire after the 1707 union of the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, in the Americas from 1 ...

n territory established by the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Proclam ...

that set aside land for use by the Native American tribes. The proclamation limited the settlement of Europeans to lands east of the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. The ...

. The territory remained active until the Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

, and the land was ceded to the United States. The Indian Reserve was slowly reduced in size via treaties with the American colonists, and after the British defeat in the Revolutionary War, the Reserve was ignored by European American settler

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a pioneer.

Settl ...

s who slowly expanded westward.

At the time of the American Revolutionary War, many Native American tribes had long-standing relationships with the British, and were loyal to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

, but they had a less-developed relationship with the American colonists. After the defeat of the British in the war, the Americans twice invaded the Ohio Country and were twice defeated. They finally defeated the Indian Western Confederacy

The Northwestern Confederacy, or Northwestern Indian Confederacy, was a loose confederacy of Native Americans in the Great Lakes region of the United States created after the American Revolutionary War. Formally, the confederacy referred to its ...

at the Battle of Fallen Timbers

The Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794) was the final battle of the Northwest Indian War, a struggle between Native American tribes affiliated with the Northwestern Confederacy and their British allies, against the nascent United Stat ...

in 1794 and imposed the Treaty of Greenville

The Treaty of Greenville, formally titled Treaty with the Wyandots, etc., was a 1795 treaty between the United States and indigenous nations of the Northwest Territory (now Midwestern United States), including the Wyandot and Delaware peopl ...

, which ceded most of what is now Ohio, part of present-day Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

, and the lands that include present-day Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

and Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at ...

, to the United States federal government.

The period after the American Revolutionary War was one of rapid western expansion. The areas occupied by Native Americans in the United States were called Indian country. They were distinguished from "unorganized territory Unorganized territory may refer to:

* An unincorporated area in any number of countries

* One of the current or former territories of the United States that has not had a government "organized" with an "organic act" by the U.S. Congress

* Unorganiz ...

" because the areas were established by treaty.

In 1803 the United States of America agreed to purchase

In 1803 the United States of America agreed to purchase France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

's claim to French Louisiana

The term French Louisiana refers to two distinct regions:

* first, to colonial French Louisiana, comprising the massive, middle section of North America claimed by France during the 17th and 18th centuries; and,

* second, to modern French Louisi ...

for a total of $15 million (less than 3 cents per acre).

President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the nati ...

doubted the legality of the purchase. However, the chief negotiator, Robert R. Livingston

Robert Robert Livingston (November 27, 1746 (Old Style November 16) – February 26, 1813) was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from New York, as well as a Founding Father of the United States. He was known as "The Chancellor", afte ...

believed that the 3rd article of the treaty providing for the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

would be acceptable to Congress. The 3rd article stated, in part:

This committed the US government to "the ultimate, but not to the immediate, admission" of the territory as multiple states, and "postponed its incorporation into the Union to the pleasure of Congress".

After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, President Thomas Jefferson and his successors viewed much of the land west of the Mississippi River as a place to resettle the Native Americans, so that white settlers would be free to live in the lands east of the river. Indian removal became the official policy of the United States government with the passage of the 1830 Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

, formulated by President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame a ...

.

When Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a U.S. state, state in the Deep South and South Central United States, South Central regions of the United States. It is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 20th-smal ...

became a state in 1812, the remaining territory was renamed Missouri Territory

The Territory of Missouri was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 4, 1812, until August 10, 1821. In 1819, the Territory of Arkansas was created from a portion of its southern area. In 1821, a southe ...

to avoid confusion. Arkansas Territory

The Arkansas Territory was a territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1819, to June 15, 1836, when the final extent of Arkansas Territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Arkansas. Arkansas Post was the first terri ...

, which included the present State of Arkansas plus most of the state of Oklahoma, was created out of the southern part of Missouri Territory in 1819. Originally the western border of Missouri was intended to extend due south all the way to the Red River, just north of Louisiana. However, during negotiations with the Choctaw in 1820 for the Treaty of Doak's Stand

The Treaty of Doak's Stand (7 Stat. 210, also known as Treaty with the Choctaw) was signed on October 18, 1820 (proclaimed on January 8, 1821) between the United States and the Choctaw Indian tribe. Based on the terms of the accord, the Chocta ...

, Andrew Jackson ceded more of Arkansas Territory to the Choctaw than he realized, from what is now Oklahoma into Arkansas, east of Ft. Smith, Arkansas

Fort Smith is the third-largest city in Arkansas and one of the two county seats of Sebastian County. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 89,142. It is the principal city of the Fort Smith, Arkansas–Oklahoma Metropolitan Statistical Are ...

. The General Survey Act

The General Survey Act was a law passed by the United States Congress in April 1824, which authorized the president to have surveys made of routes for transport roads and canals "of national importance, in a commercial or military point of view, or ...

of 1824 allowed a survey that established the western border of Arkansas Territory 45 miles west of Ft. Smith. But this was where the Choctaw and Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

tribes had just begun to settle, and the two nations objected strongly. In 1828 a new survey redefined the western Arkansas border just west of Ft. Smith. After these redefinitions, the "Indian zone" would cover the present states of Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska and part of Iowa.

Relocation and treaties

Before the 1871Indian Appropriations Act

The Indian Appropriations Act is the name of several acts passed by the United States Congress. A considerable number of acts were passed under the same name throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, but the most notable landmark acts cons ...

, much of what was called Indian Territory was a large area in the central part of the United States whose boundaries were set by treaties between the US Government and various indigenous tribes. After 1871, the Federal Government dealt with Indian Tribes through statute; the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act also stated that "hereafter no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty: Provided, further, That nothing herein contained shall be construed to invalidate or impair the obligation of any treaty heretofore lawfully made and ratified with any such Indian nation or tribe".25 U.S.C. § 71. Indian Appropriation Act of March 3, 1871, 16 Stat. 544, 566

The Indian Appropriations Act also made it a federal crime to commit murder, manslaughter, rape, assault with intent to kill, arson, burglary, or larceny within any Territory of the United States. The Supreme Court affirmed the action in 1886 in ''United States v. Kagama

''United States v. Kagama'', 118 U.S. 375 (1886), was a United States Supreme Court case that upheld the constitutionality of the Major Crimes Act of 1885. This Congressional act gave the federal courts jurisdiction in certain Indian-on-Indian ...

'', which affirmed that the US Government has plenary power

A plenary power or plenary authority is a complete and absolute power to take action on a particular issue, with no limitations. It is derived from the Latin term ''plenus'' ("full").

United States

In United States constitutional law, plenary p ...

over Native American tribes within its borders using the rationalization that "The power of the general government over these remnants of a race once powerful ... is necessary to their protection as well as to the safety of those among whom they dwell".

While the federal government of the United States had previously recognized the Indian Tribes as semi-independent, "it has the right and authority, instead of controlling them by treaties, to govern them by acts of Congress, they being within the geographical limit of the United States ... The Indians ative Americansowe no allegiance to a State within which their reservation may be established, and the State gives them no protection."

Reductions of area

White settlers continued to flood into Indian country. As the population increased, the homesteaders could petition Congress for creation of a territory. This would initiate anOrganic Act

In United States law, an organic act is an act of the United States Congress that establishes a territory of the United States and specifies how it is to be governed, or an agency to manage certain federal lands. In the absence of an orga ...

, which established a three-part territorial government. The governor and judiciary were appointed by the President of the United States, while the legislature was elected by citizens residing in the territory. One elected representative was allowed a seat in the U. S. House of Representatives. The federal government took responsibility for territorial affairs. Later, the inhabitants of the territory could apply for admission as a full state. No such action was taken for the so-called Indian Territory, so that area was not treated as a legal territory.

The reduction of the land area of Indian Territory (or Indian Country, as defined in the Indian Intercourse Act

The Nonintercourse Act (also known as the Indian Intercourse Act or the Indian Nonintercourse Act) is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set Amerindian boundaries of re ...

of 1834), the successor of Missouri Territory began almost immediately after its creation with:

* Wisconsin Territory

The Territory of Wisconsin was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 3, 1836, until May 29, 1848, when an eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Wisconsin. Belmont was ...

formed in 1836 from lands east of the Mississippi and between the Mississippi and Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

rivers. Wisconsin became a state in 1848

** Iowa Territory

The Territory of Iowa was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1838, until December 28, 1846, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Iowa. The remain ...

(land between the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers) was split from Wisconsin Territory in 1838 and became a state in 1846.

*** Minnesota Territory

The Territory of Minnesota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1849, until May 11, 1858, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Minnesota and west ...

was split from Iowa Territory in 1849 and part of the Minnesota Territory became the state of Minnesota in 1858

* Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of ...

was organized in 1861 from the northern part of Indian Country and Minnesota Territory. The name refers to the Dakota branch of the Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

tribes.

** North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, S ...

and South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

became separate states simultaneously in 1889.

** Present-day states of Montana

Montana () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West List of regions of the United States#Census Bureau-designated regions and divisions, division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North ...

and Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the sou ...

were also part of the original Dakota Territory

Indian Country was reduced to the approximate boundaries of the current state of Oklahoma by the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

of 1854, which created Kansas Territory and Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebras ...

. The key boundaries of the territories were:

* 40° N the current Kansas–Nebraska border

* 37° N the current Kansas–Oklahoma (Indian Territory) border

Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to ...

became a state in 1861, and Nebraska became a state in 1867. In 1890 the Oklahoma Organic Act

An Organic Act is a generic name for a statute used by the United States Congress to describe a territory, in anticipation of being admitted to the Union as a state. Because of Oklahoma's unique history (much of the state was a place where abori ...

created Oklahoma Territory out of the western part of Indian Territory, in anticipation of admitting both Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory as a future single State of Oklahoma.

Civil War and Reconstruction

At the beginning of theCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

, Indian Territory had been essentially reduced to the boundaries of the present-day U.S. state of Oklahoma, and the primary residents of the territory were members of the Five Civilized Tribes or Plains tribes

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) of ...

that had been relocated to the western part of the territory on land leased from the Five Civilized Tribes. In 1861, the U.S. abandoned Fort Washita

Fort Washita is the former United States military post and National Historic Landmark located in Durant, Oklahoma on SH 199. Established in 1842 by General (later President) Zachary Taylor to protect citizens of the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nati ...

, leaving the Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classifi ...

and Choctaw Nations defenseless against the Plains tribes. Later the same year, the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confede ...

signed a Treaty with Choctaws and Chickasaws

The Treaty with Choctaws and Chickasaws was a treaty signed on July 12, 1861 between the Choctaw and Chickasaw ( American Indian) and the Confederate States. At the beginning of the American Civil War, Albert Pike was appointed as Confederate en ...

. Ultimately, the Five Civilized Tribes and other tribes that had been relocated to the area, signed treaties of friendship with the Confederacy.

During the Civil War, Congress gave the U.S. president the authority to, if a tribe was "in a state of actual hostility to the government of the United States... and, by proclamation, to declare all treaties with such tribe to be abrogated by such tribe"(25 USC Sec. 72).

Members of the Five Civilized Tribes, and others who had relocated to the Oklahoma section of Indian Territory, fought primarily on the side of the Confederacy during the American Civil War in Indian territory. Brigadier General Stand Watie

Brigadier-General Stand Watie ( chr, ᏕᎦᏔᎦ, translit=Degataga, lit=Stand firm; December 12, 1806September 9, 1871), also known as Standhope Uwatie, Tawkertawker, and Isaac S. Watie, was a Cherokee politician who served as the second prin ...

, a Confederate commander of the Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It ...

, became the last Confederate general to surrender in the American Civil War, near the community of Doaksville

Doaksville is a former settlement, now a ghost town, located in present-day Choctaw County, Oklahoma. It was founded between 1824 and 1831, by people of the Choctaw Indian tribe who were forced to leave their homes in the Southeastern United Sta ...

on June 23, 1865. The Reconstruction Treaties

On the eve of the American Civil War in 1861, a significant number of Indigenous peoples of the Americas had been relocated from the Southeastern United States to Indian Territory, west of the Mississippi. The inhabitants of the eastern part of th ...

signed at the end of the Civil War fundamentally changed the relationship between the tribes and the U.S. government.

The Reconstruction era played out differently in Indian Territory and for Native Americans than for the rest of the country. In 1862, Congress passed a law that allowed the president, by proclamation, to cancel treaties with Indian Nations siding with the Confederacy (25 USC 72).

The United States House Committee on Territories The United States House Committee on Territories was a committee of the United States House of Representatives from 1825 to 1946 (19th to 79th Congresses). Its jurisdiction was reporting on a variety of topics related to the territories, including ...

(created in 1825) was examining the effectiveness of the policy of Indian removal, which was after the war considered to be of limited effectiveness. It was decided that a new policy of Assimilation

Assimilation may refer to:

Culture

*Cultural assimilation, the process whereby a minority group gradually adapts to the customs and attitudes of the prevailing culture and customs

**Language shift, also known as language assimilation, the progre ...

would be implemented. To implement the new policy, the Southern Treaty Commission was created by Congress to write new treaties with the Tribes siding with the Confederacy.

After the Civil War the Southern Treaty Commission re-wrote treaties with tribes that sided with the Confederacy, reducing the territory of the Five Civilized Tribes and providing land to resettle Plains Native Americans and tribes of the mid-west. General components of replacement treaties signed in 1866 include:

* Abolition of slavery

* Amnesty for siding with Confederate States of America

* Agreement to legislation that Congress and the President "may deem necessary for the better administration of justice and the protection of the rights of person and property within the Indian territory."

* That the tribes grant right of way for rail roads authorized by Congress; A land patent

A land patent is a form of letters patent assigning official ownership of a particular tract of land that has gone through various legally-prescribed processes like surveying and documentation, followed by the letter's signing, sealing, and publi ...

, or "first-title deed" to alternate sections of land adjacent to rail roads would be granted to the rail road upon completion of each 20 mile section of track and water stations

* That within each county, a quarter section of land be held in trust for the establishment of seats of justice therein, and also as many quarter-sections as the said legislative councils may deem proper for the permanent endowment of schools

* Provision for each man, woman, and child to receive 160 acres of land as an allotment. (The allotment policy was later codified on a national basis through the passage of The Dawes Act

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the Pre ...

, also called General Allotment Act, or Dawes Severalty Act of 1887)

* That a land patent, or "first-title deed" be issued as evidence of allotment, "issued by the President of the United States, and countersigned by the chief executive officer of the nation in which the land lies"

* That treaties and parts of treaties inconsistent with the replacement treaties to be null and void.

One component of assimilation would be the distribution of property held in-common by the tribe to individual members of the tribe.

The Medicine Lodge Treaty

The Medicine Lodge Treaty is the overall name for three treaties signed near Medicine Lodge, Kansas, between the Federal government of the United States and southern Plains Indian tribes in October 1867, intended to bring peace to the area by rel ...

is the overall name given to three treaties signed in Medicine Lodge, Kansas

Medicine Lodge is a city in and the county seat of Barber County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 1,781.

History

19th century

The particular medicine lodge, mystery house or sacred tabernacle from ...

between the US government and southern Plains Indian tribes who would ultimately reside in the western part of Indian Territory (ultimately Oklahoma Territory). The first treaty was signed October 21, 1867, with the Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th a ...

and Comanche tribes.

The second, with the Plains Apache

The Plains Apache are a small Southern Athabaskan group who live on the Southern Plains of North America, in close association with the linguistically unrelated Kiowa Tribe. Today, they are centered in Southwestern Oklahoma and Northern Texas ...

, was signed the same day. The third treaty was signed with the Southern Cheyenne

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes are a united, federally recognized tribe of Southern Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne people in western Oklahoma.

History

The Cheyennes and Arapahos are two distinct tribes with distinct histories. The Cheyenne (Tsi ...

and Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho ...

on October 28.

Another component of assimilation was homesteading. The Homestead Act of 1862

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of t ...

was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

. The Act gave an applicant freehold

Freehold may refer to:

In real estate

*Freehold (law), the tenure of property in fee simple

*Customary freehold, a form of feudal tenure of land in England

*Parson's freehold, where a Church of England rector or vicar of holds title to benefice p ...

title

A title is one or more words used before or after a person's name, in certain contexts. It may signify either generation, an official position, or a professional or academic qualification. In some languages, titles may be inserted between the f ...

to an area called a "homestead" – typically 160 acres (65 hectares or one-fourth section

Section, Sectioning or Sectioned may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Section (music), a complete, but not independent, musical idea

* Section (typography), a subdivision, especially of a chapter, in books and documents

** Section sign ...

) of undeveloped federal land

Federal lands are lands in the United States owned by the federal government. Pursuant to the Property Clause of the United States Constitution ( Article 4, section 3, clause 2), Congress has the power to retain, buy, sell, and regulate federal ...

. Within Indian Territory, as lands were removed from communal tribal ownership, a land patent (or first-title deed) was given to tribal members. The remaining land was sold on a first-come basis, typically by land run

A land run or land rush was an event in which previously restricted land of the United States was opened to homestead on a first-arrival basis. Lands were opened and sold first-come or by bid, or won by lottery, or by means other than a run. The ...

, with settlers also receiving a land patent type deed. For these now former Indian lands, the General Land Office

The General Land Office (GLO) was an independent agency of the United States government responsible for public domain lands in the United States. It was created in 1812 to take over functions previously conducted by the United States Department ...

distributed the sales funds to the various tribal entities, according to previously negotiated terms.

Oklahoma Territory, end of territories upon statehood

The Oklahoma organic act of 1890 created an organized incorporated territory of the United States of Oklahoma Territory, with the intent of combining the Oklahoma and Indian territories into a single State of Oklahoma. The citizens of Indian Territory tried, in 1905, to gain admission to the union as theState of Sequoyah

The State of Sequoyah was a proposed state to be established from the Indian Territory in the eastern part of present-day Oklahoma. In 1905, with the end of tribal governments looming (as prescribed by the Curtis Act of 1898), Native America ...

, but were rebuffed by Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

and an Administration which did not want two new Western states, Sequoyah and Oklahoma. Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

then proposed a compromise that would join Indian Territory with Oklahoma Territory to form a single state. This resulted in passage of the Oklahoma Enabling Act

The Enabling Act of 1906, in its first part, empowered the people residing in Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory to elect delegates to a state constitutional convention and subsequently to be admitted to the union as a single state.

The act, ...

, which President Roosevelt signed June 16, 1906. empowered the people residing in Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory to elect delegates to a state constitutional convention and subsequently to be admitted to the union as a single state. Citizens then joined to seek admission of a single state to the Union. With Oklahoma statehood in November 1907, Indian Territory lost its "independence" and was extinguished.

Tribes

Tribes indigenous to Oklahoma

Indian Territory marks the confluence of theSouthern Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

and Southeastern Woodlands

Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, Southeastern cultures, or Southeast Indians are an ethnographic classification for Native Americans who have traditionally inhabited the area now part of the Southeastern United States and the nor ...

cultural region

In anthropology and geography, a cultural region, cultural sphere, cultural area or culture area refers to a geography with one relatively homogeneous human activity or complex of activities (culture). Such activities are often associated ...

s. Its western region is part of the Great Plains, subjected to extended periods of drought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

and high winds, and the Ozark Plateau

The Ozarks, also known as the Ozark Mountains, Ozark Highlands or Ozark Plateau, is a physiographic region in the U.S. states of Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma and the extreme southeastern corner of Kansas. The Ozarks cover a significant port ...

is to the east in a humid subtropical climate zone. Tribes indigenous to the present day state of Oklahoma include both agrarian

Agrarian means pertaining to agriculture, farmland, or rural areas.

Agrarian may refer to:

Political philosophy

*Agrarianism

*Agrarian law, Roman laws regulating the division of the public lands

*Agrarian reform

*Agrarian socialism

Society

...

and hunter-gatherer tribes. The arrival of horses with the Spanish in the 16th century ushered in horse culture

A horse culture is a tribal group or community whose day-to-day life revolves around the herding and breeding of horses. Beginning with the domestication of the horse on the steppes of Eurasia, the horse transformed each society that adopted i ...

-era, when tribes could adopt a nomadic

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

lifestyle and follow abundant bison

Bison are large bovines in the genus ''Bison'' (Greek: "wild ox" (bison)) within the tribe Bovini. Two extant and numerous extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, ''B. bison'', found only in North ...

herds.

The

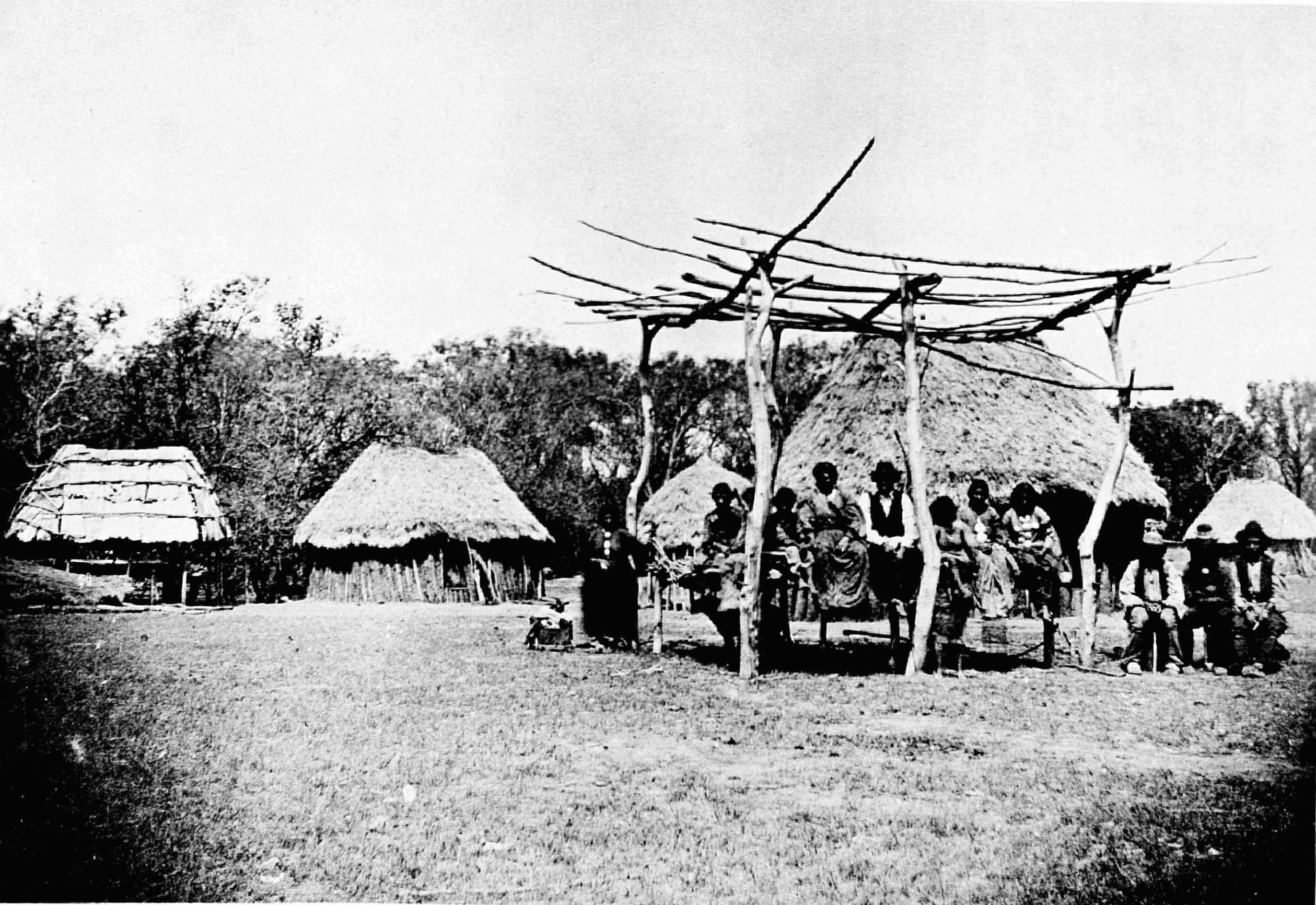

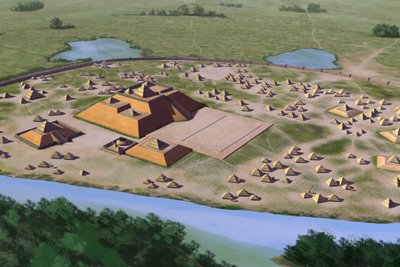

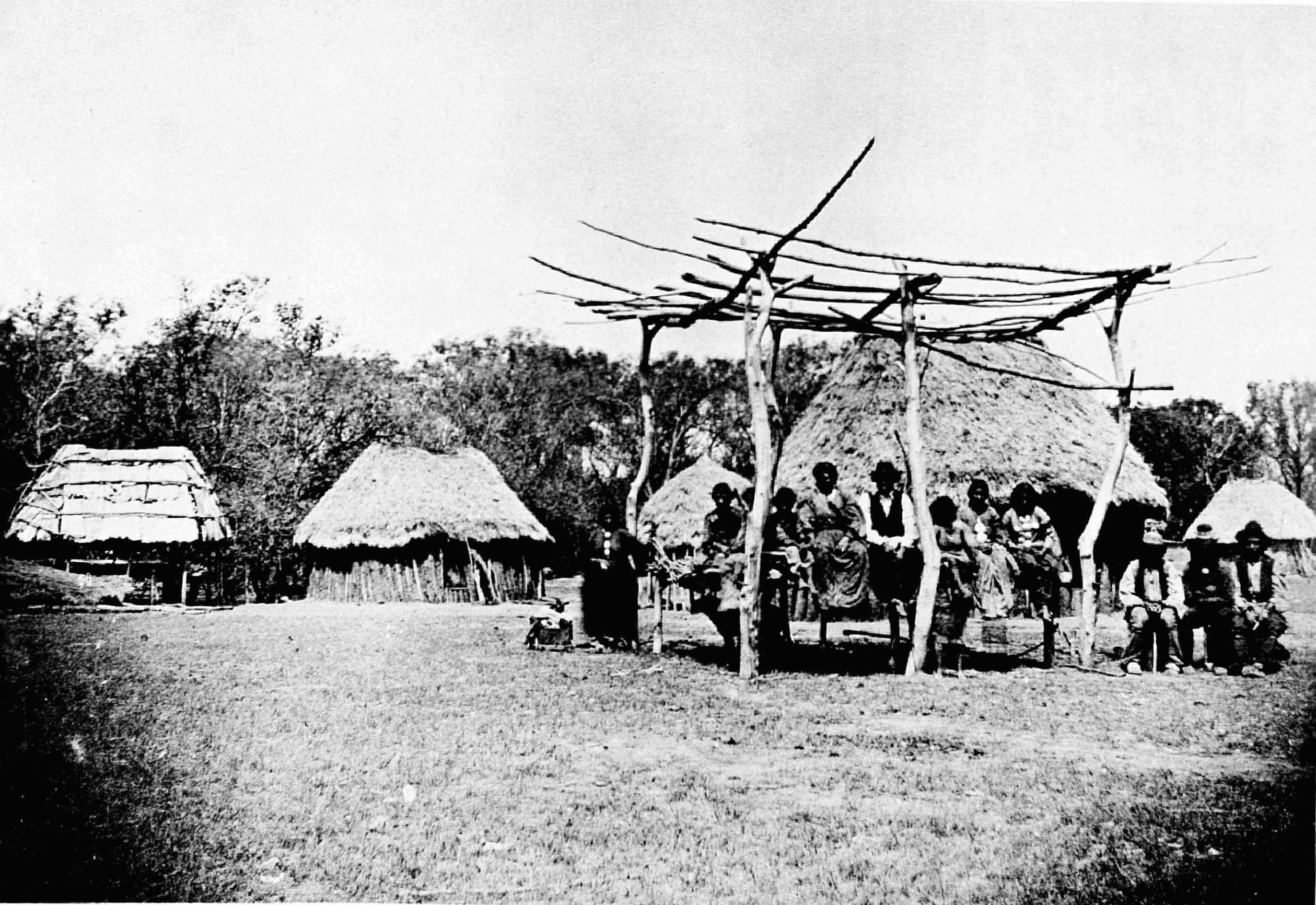

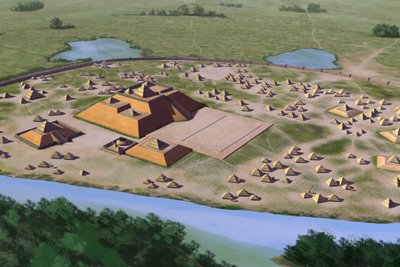

The Southern Plains villagers

The Southern Plains villagers were semi-sedentary Native Americans who lived on the Great Plains in western Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, and southeastern Colorado from about AD 800 until AD 1500.

Also known as Plains Villagers, the people of this p ...

, an archaeological culture that flourished from 800 to 1500 AD, lived in semi-sedentary villages throughout the western part of Indian Territory, where they farmed maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn ( North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. ...

and hunted buffalo. They are likely ancestors of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes

The Wichita people or Kitikiti'sh are a confederation of Southern Plains Native American tribes. Historically they spoke the Wichita language and Kichai language, both Caddoan languages. They are indigenous to Oklahoma, Texas, and Kansas.

T ...

. The ancestors of the Wichita have lived in the eastern Great Plains from the Red River north to Nebraska for at least 2,000 years. The early Wichita people were hunters and gatherers who gradually adopted agriculture. By about 900 AD, farming villages began to appear on terraces above the Washita River

The Washita River () is a river in the states of Texas and Oklahoma in the United States. The river is long and terminates at its confluence with the Red River, which is now part of Lake Texoma () on the TexasOklahoma border.

Geography

The ...

and South Canadian River

The Canadian River is the longest tributary of the Arkansas River in the United States. It is about long, starting in Colorado and traveling through New Mexico, the Texas Panhandle, and Oklahoma. The drainage area is about .Caddo Confederacy

The Caddo people comprise the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Binger, Oklahoma. They speak the Caddo language.

The Caddo Confederacy was a network of Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, who ...

lived in the eastern part of Indian Territory and are ancestors of the Caddo Nation

The Caddo people comprise the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Binger, Oklahoma. They speak the Caddo language.

The Caddo Confederacy was a network of Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, wh ...

. The Caddo people speak a Caddoan language and is a confederation of several tribes who traditionally inhabited much of what is now East Texas

East Texas is a broadly defined cultural, geographic, and ecological region in the eastern part of the U.S. state of Texas that comprises most of 41 counties. It is primarily divided into Northeast and Southeast Texas. Most of the region con ...

, northern Louisiana and portions of southern Arkansas and Oklahoma. The tribe was once part of the Caddoan Mississippian culture

The Caddoan Mississippian culture was a prehistoric Native American culture considered by archaeologists as a variant of the Mississippian culture. The Caddoan Mississippians covered a large territory, including what is now Eastern Oklahoma, We ...

and thought to be an extension of woodland period peoples who started inhabiting the area around 200 BC. In an 1835 Treaty made at the agency-house in the Caddo nation and State of Louisiana, the Caddo Nation sold their tribal lands to the US. In 1846 the Caddo along with several other tribes signed a treaty that made the Caddo a protectorate of the US and established framework of a legal system between the Caddo and the US. Tribal headquarters are in Binger, Oklahoma

Binger is a town in Caddo County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 672 at the 2010 census. It is the headquarters of the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, who were settled in the area during the 1870s.

.

The Wichita and Caddo both spoke Caddoan languages

The Caddoan languages are a family of languages native to the Great Plains spoken by tribal groups of the central United States, from present-day North Dakota south to Oklahoma. All Caddoan languages are critically endangered, as the number of ...

, as did the Kichai people

The Kichai tribe (also Keechi or Kitsai) was a Native American Southern Plains tribe that lived in Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma. Their name for themselves was K'itaish.

History

The Kichai were most closely related to the Pawnee. French expl ...

, who were also indigenous to what is now Oklahoma and ultimately became part of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes

The Wichita people or Kitikiti'sh are a confederation of Southern Plains Native American tribes. Historically they spoke the Wichita language and Kichai language, both Caddoan languages. They are indigenous to Oklahoma, Texas, and Kansas.

T ...

. The Wichita (and other tribes) signed a treaty of friendship with the US in 1835. The tribe's headquarters are in Anadarko, Oklahoma

Anadarko is a city in Caddo County, Oklahoma, United States. The city is fifty miles southwest of Oklahoma City. The population was 5,745 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Caddo County.

History

Anadarko got its name when its post off ...

.

In the 18th century, prior to Indian Removal (the forced relocation by the US federal government) Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th a ...

, Apache, and Comanche people entered into Indian Territory from the west, and the Quapaw

The Quapaw ( ; or Arkansas and Ugahxpa) people are a tribe of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans that coalesced in what is known as the Midwest and Ohio Valley of the present-day United States. The Dhegiha Siouan-speaking tr ...

and Osage The Osage Nation, a Native American tribe in the United States, is the source of most other terms containing the word "osage".

Osage can also refer to:

* Osage language, a Dhaegin language traditionally spoken by the Osage Nation

* Osage (Unicode ...

entered from the east. During Indian Removal of the 19th century, additional tribes received their land either by treaty via land grant from the federal government of the United States

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

or they purchased the land receiving fee simple

In English law, a fee simple or fee simple absolute is an estate in land, a form of freehold ownership. A "fee" is a vested, inheritable, present possessory interest in land. A "fee simple" is real property held without limit of time (i.e., ...

recorded title.

Tribes from the Southeastern Woodlands

Many of the tribes forcibly relocated to Indian Territory were from

Many of the tribes forcibly relocated to Indian Territory were from Southeastern United States

The Southeastern United States, also referred to as the American Southeast or simply the Southeast, is a geographical region of the United States. It is located broadly on the eastern portion of the southern United States and the southern po ...

, including the so-called Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

or Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

, Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classifi ...

, Choctaw, Muscogee Creeks, and Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

, but also the Natchez, Yuchi

The Yuchi people, also spelled Euchee and Uchee, are a Native American tribe based in Oklahoma.

In the 16th century, Yuchi people lived in the eastern Tennessee River valley in Tennessee. In the late 17th century, they moved south to Alabama, ...

, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

, Koasati

The Coushatta ( cku, Koasati, Kowassaati or Kowassa:ti) are a Muskogean-speaking Native American people now living primarily in the U.S. states of Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas.

When first encountered by Europeans, they lived in the terri ...

, and Caddo people

The Caddo people comprise the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Binger, Oklahoma. They speak the Caddo language.

The Caddo Confederacy was a network of Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, ...

.

Between 1814 and 1840, the Five Civilized Tribes had gradually ceded most of their lands in the Southeast section of the US through a series of treaties. The southern part of Indian Country (what eventually became the State of Oklahoma) served as the destination for the policy of Indian removal, a policy pursued intermittently by

Between 1814 and 1840, the Five Civilized Tribes had gradually ceded most of their lands in the Southeast section of the US through a series of treaties. The southern part of Indian Country (what eventually became the State of Oklahoma) served as the destination for the policy of Indian removal, a policy pursued intermittently by American presidents

The president of the United States is the head of state and head of government of the United States, indirectly elected to a four-year term via the Electoral College. The officeholder leads the executive branch of the federal government an ...

early in the 19th century, but aggressively pursued by President Andrew Jackson after the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The Five Civilized Tribes in the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

were the most prominent tribes displaced by the policy, a relocation that came to be known as the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

during the Choctaw removals starting in 1831. The trail ended in what is now Arkansas and Oklahoma, where there were already many Indians living in the territory, as well as whites and escaped slaves. Other tribes, such as the Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacen ...

, Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian languages, Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized tribe, federally recognize ...

, and Apache were also forced to relocate to the Indian territory.

The Five Civilized Tribes established tribal capitals in the following towns:

*

The Five Civilized Tribes established tribal capitals in the following towns:

* Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It ...

– Tahlequah

Tahlequah ( ; ''Cherokee'': ᏓᎵᏆ, ''daligwa'' ) is a city in Cherokee County, Oklahoma located at the foothills of the Ozark Mountains. It is part of the Green Country region of Oklahoma and was established as a capital of the 19th-centu ...

* Chickasaw Nation

The Chickasaw Nation ( Chickasaw: Chikashsha I̠yaakni) is a federally recognized Native American tribe, with its headquarters located in Ada, Oklahoma in the United States. They are an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, origi ...

– Tishomingo

* Choctaw Nation

The Choctaw Nation ( Choctaw: ''Chahta Okla'') is a Native American territory covering about , occupying portions of southeastern Oklahoma in the United States. The Choctaw Nation is the third-largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

– Tuskahoma (later moved to Durant

Durant may refer to:

People

* Durant (surname)

Fictional characters

* Durant (Pokémon), a species in ''Pokémon Black'' and ''White''

* ''John Durant'' (General Hospital), a character on the soap opera ''General Hospital''

Places

* Durant, ...

)

* Creek Nation

The Muscogee Nation, or Muscogee (Creek) Nation, is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The nation descends from the historic Muscogee Confederacy, a large group of indigenous peoples of the So ...

– Okmulgee

* Seminole Nation

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...

– Wewoka

These tribes founded towns such as Tulsa

Tulsa () is the second-largest city in the state of Oklahoma and 47th-most populous city in the United States. The population was 413,066 as of the 2020 census. It is the principal municipality of the Tulsa Metropolitan Area, a region with ...

, Ardmore, Muskogee, which became some of the larger towns in the state. They also brought their African slaves to Oklahoma, which added to the African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

population in the state.

* Beginning in 1783 the Choctaw signed a series of treaties with the Americans. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was a treaty which was signed on September 27, 1830, and proclaimed on February 24, 1831, between the Choctaw American Indian tribe and the United States Government. This treaty was the first removal treaty w ...

was the first removal treaty carried into effect under the Indian Removal Act, ceding land in the future state of Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Mis ...

in exchange for land in the future state of Oklahoma, resulting in the Choctaw Trail of Tears

The Choctaw Trail of Tears was the attempted ethnic cleansing and relocation by the United States government of the Choctaw Nation from their country, referred to now as the Deep South (Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana), to lands w ...

.

* The Muscogee (Creek) Nation

The Muscogee Nation, or Muscogee (Creek) Nation, is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The nation descends from the historic Muscogee Confederacy, a large group of indigenous peoples of the So ...

began the process of moving to Indian Territory with the 1814 Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Treaty of Fort Jackson (also known as the Treaty with the Creeks, 1814) was signed on August 9, 1814 at Fort Jackson near Wetumpka, Alabama following the defeat of the Red Stick (Upper Creek) resistance by United States allied forces at th ...

and the 1826 Treaty of Washington. The 1832 Treaty of Cusseta

The Treaty of Cusseta was a treaty between the government of the United States and the Creek Nation signed March 24, 1832 (). The treaty ceded all Creek claims east of the Mississippi River to the United States.

Origins

The Treaty of Cusseta, ...

ceded all Creek claims east of the Mississippi River to the United States.

* The 1835 the Treaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, the Treaty Party.

The tre ...

established terms under which the entire Cherokee Nation was expected to cede its territory in the Southeast and move to Indian Territory. Although the treaty was not approved by the Cherokee National Council, it was ratified by the U.S. Senate and resulted in the Cherokee Trail of Tears

Cherokee removal, part of the Trail of Tears, refers to the forced relocation between 1836 and 1839 of an estimated 16,000 members of the Cherokee Nation and 1,000–2,000 of their slaves; from their lands in Georgia, South Carolina, North Caroli ...

.

* The Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classifi ...

, rather than receiving land grants

A land grant is a gift of real estate—land or its use privileges—made by a government or other authority as an incentive, means of enabling works, or as a reward for services to an individual, especially in return for military service. Grants ...

in exchange for ceding indigenous land rights

Indigenous land rights are the rights of Indigenous peoples to land and natural resources therein, either individually or collectively, mostly in colonised countries. Land and resource-related rights are of fundamental importance to Indig ...

, received financial compensation. The tribe negotiated a $3 million payment for their native lands (which was not fully funded by the US for 30 years). In 1836, the Chickasaw agreed to purchase land from the previously removed Choctaws for $530,000.

* The Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

People, originally from the present-day state of Florida, signed the Treaty of Payne's Landing

The Treaty of Payne's Landing (Treaty with the Seminole, 1832) was an agreement signed on 9 May 1832 between the government of the United States and several chiefs of the Seminole Indians in the Territory of Florida, before it acquired statehood.

...

in 1832, in response to the 1830 Indian Removal Act, that forced the tribes to move to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. In October 1832 a delegation arrived in Indian Territory and conferred with the Creek Nation tribe that had already been removed to the area. In 1833 an agreement was signed at Fort Gibson

Fort Gibson is a historic military site next to the modern city of Fort Gibson, in Muskogee County Oklahoma. It guarded the American frontier in Indian Territory from 1824 to 1888. When it was constructed, the fort was farther west than any ...

(on the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United S ...

just east of Muskogee, Oklahoma), accepting the area in the western part of the Creek Nation. However, the chiefs in Florida did not agree to the agreement. In spite of the disagreement, the treaty was ratified by the Senate in April 1834.

Tribes from the Great Lakes and Northeastern Woodlands

The

The Western Lakes Confederacy

The Northwestern Confederacy, or Northwestern Indian Confederacy, was a loose confederacy of Native Americans in the Great Lakes region of the United States created after the American Revolutionary War. Formally, the confederacy referred to ...

was a loose confederacy of tribes around the Great Lakes region

The Great Lakes region of North America is a binational Canada, Canadian–United States, American region that includes portions of the eight U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York (state), New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania ...

, organized following the American Revolutionary War to resist the expansion of the United States into the Northwest Territory. Members of the confederacy were ultimately removed to the present-day Oklahoma, including the Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

, Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacen ...

(also called Lenape