Independent State of Croatia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Independent State of Croatia ( sh, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH; german: Unabhängiger Staat Kroatien; it, Stato indipendente di Croazia) was a

"The NDH was in fact an Italo-German condominium. Both Nazi Germany and fascist Italy had spheres of influence in the NDH and stationed their own troops there." In its judgement in the

Following the attack of the Axis powers on the

Following the attack of the Axis powers on the  On 16 August 1941, the Ustasha Surveillance Service was established, consisting of four departments, the ''Ustasha Police'', the ''Ustasha Intelligence Service'', ''Ustasha Defense'', and ''Personnel'', for the suppression of activities against the Ustasha, the Independent State of Croatia, and the Croatia people. The Service was eliminated as a separate agency in January 1943 and functions were transferred to the Ministry of Interior under the ''Directorate of Public Order''.

Dissatisfied with the Pavelić regime in its early months, the Axis Powers in September 1941 asked Maček to take over, but Maček again refused. Perceiving Maček as a potential rival, Pavelić subsequently had him arrested and interned in the

On 16 August 1941, the Ustasha Surveillance Service was established, consisting of four departments, the ''Ustasha Police'', the ''Ustasha Intelligence Service'', ''Ustasha Defense'', and ''Personnel'', for the suppression of activities against the Ustasha, the Independent State of Croatia, and the Croatia people. The Service was eliminated as a separate agency in January 1943 and functions were transferred to the Ministry of Interior under the ''Directorate of Public Order''.

Dissatisfied with the Pavelić regime in its early months, the Axis Powers in September 1941 asked Maček to take over, but Maček again refused. Perceiving Maček as a potential rival, Pavelić subsequently had him arrested and interned in the

At the time of the invasion of Yugoslavia by Nazi Germany,

At the time of the invasion of Yugoslavia by Nazi Germany,  General Glaise-Horstenau reported: "The Ustaše movement is, due to the mistakes and atrocities they have committed and the corruption, so compromised that the government executive branch (the home guard and the police) shall be separated from the government – even for the price of breaking any possible connection with the government."

Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler is quoted characterizing the Independent State of Croatia as "ridiculous": "our beloved German settlements will be secured. I hope that the area south of Srem will be liberated by ... the Bosnian division ... so that we can at least restore partial order in this ridiculous (Croatian) state."

The Ustaše gained German support for plans to eliminate the Serb population in Croatia. One plan involved an exchange in 1941 between Germany and the NDH, in which 20,000 Catholic Slovenes would be deported from German-held Slovenia and sent to the NDH where they would be assimilated as Croats. In exchange, 20,000 Serbs would be deported from the NDH and sent to the German-occupied territory of Serbia. On the meeting with Hitler on 6 June 1941 in

General Glaise-Horstenau reported: "The Ustaše movement is, due to the mistakes and atrocities they have committed and the corruption, so compromised that the government executive branch (the home guard and the police) shall be separated from the government – even for the price of breaking any possible connection with the government."

Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler is quoted characterizing the Independent State of Croatia as "ridiculous": "our beloved German settlements will be secured. I hope that the area south of Srem will be liberated by ... the Bosnian division ... so that we can at least restore partial order in this ridiculous (Croatian) state."

The Ustaše gained German support for plans to eliminate the Serb population in Croatia. One plan involved an exchange in 1941 between Germany and the NDH, in which 20,000 Catholic Slovenes would be deported from German-held Slovenia and sent to the NDH where they would be assimilated as Croats. In exchange, 20,000 Serbs would be deported from the NDH and sent to the German-occupied territory of Serbia. On the meeting with Hitler on 6 June 1941 in

After the 1941 split between the Partisans and the

After the 1941 split between the Partisans and the

The economy of the Independent State of Croatia was largely subordinated to the economic interests of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, and had to meet significant obligations to them. The dominant power was Nazi Germany, which demanded supplies of raw materials from the NDH in order to support the German economy and its war effort. The Croatian workforce was also seen as a potential replacement for some of the German workers who had been recruited into the military and were sent off to war. An economic agreement signed in May 1941 provided Germany with unrestricted access to industrial raw materials in the NDH, and obligated the NDH to bear the costs of German military units stationed on its territory; this was a very large burden given the small size of the Croatian economy. Similar agreements were also concluded with Italy on a more short-term basis (they had to be renewed every three months), which obligated the NDH to support and resupply Italian army units within its borders, to make monthly payments to Italy, and to allow the Italian military to freely cut down trees for lumber.

The German and Italian authorities did not coordinate their respective policies towards Croatia, resulting in overlapping and conflicting demands which further burdened the Croatian economy. In particular, both Germany and Italy demanded large quantities of

The economy of the Independent State of Croatia was largely subordinated to the economic interests of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, and had to meet significant obligations to them. The dominant power was Nazi Germany, which demanded supplies of raw materials from the NDH in order to support the German economy and its war effort. The Croatian workforce was also seen as a potential replacement for some of the German workers who had been recruited into the military and were sent off to war. An economic agreement signed in May 1941 provided Germany with unrestricted access to industrial raw materials in the NDH, and obligated the NDH to bear the costs of German military units stationed on its territory; this was a very large burden given the small size of the Croatian economy. Similar agreements were also concluded with Italy on a more short-term basis (they had to be renewed every three months), which obligated the NDH to support and resupply Italian army units within its borders, to make monthly payments to Italy, and to allow the Italian military to freely cut down trees for lumber.

The German and Italian authorities did not coordinate their respective policies towards Croatia, resulting in overlapping and conflicting demands which further burdened the Croatian economy. In particular, both Germany and Italy demanded large quantities of

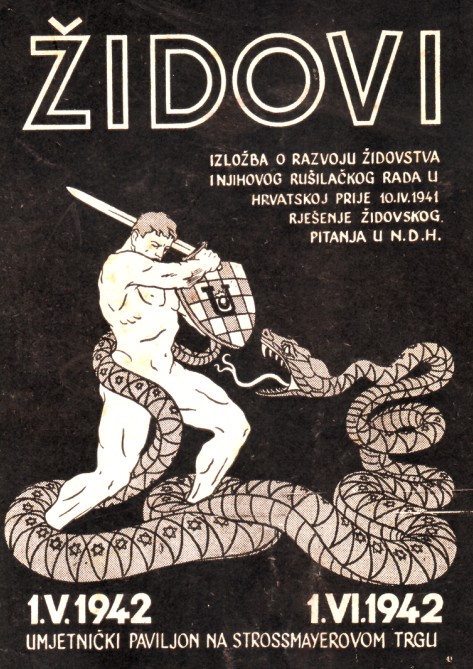

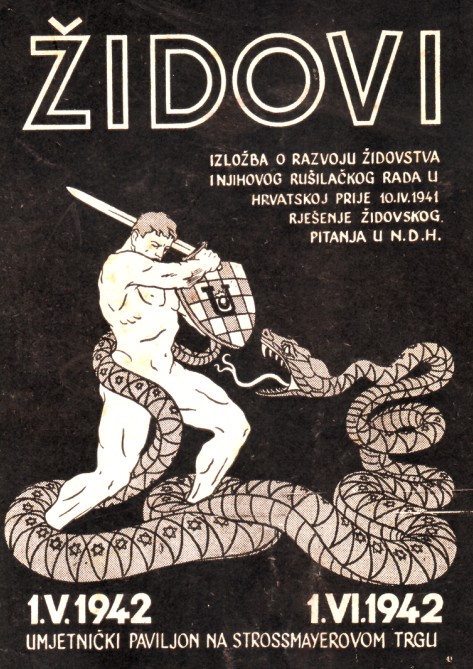

Honorary Aryans: National-Racial Identity and Protected Jews in the Independent State of Croatia

Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, p. 63 The desire to build a Croatian national community was seen as a part of a broader European national revolution that was opposed to the ideologies of the

BBC News 29 November 2001: Croatian holocaust still stirs controversy

{{DEFAULTSORT:Croatia, Independent State Of Client states of Fascist Italy Client states of Nazi Germany Condominia (international law) * Former countries in the Balkans

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

-era puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a State (polity), state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside Power (international relations), power and subject to its o ...

of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and Fascist Italy. It was established in parts of occupied Yugoslavia

World War II in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia began on 6 April 1941, when the country was swiftly conquered by Axis forces and partitioned between Germany, Italy, Hungary, Bulgaria and their client regimes. Shortly after Germany attacked the US ...

on 10 April 1941, after the invasion by the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

. Its territory consisted of most of modern-day Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

and Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and H ...

, as well as some parts of modern-day Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

and Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, an ...

, but also excluded many Croat

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic, Ge ...

-populated areas in Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

(until late 1943), Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

, and Međimurje regions (which today are part of Croatia).

During its entire existence, the NDH was governed as a one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

by the fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

Ustaša organization. The Ustaše was led by the ''Poglavnik

() was the title used by Ante Pavelić, leader of the World War II Croatian movement Ustaše and of the Independent State of Croatia between 1941 and 1945.

Etymology and usage

The word was first recorded in a 16th-century dictionary compiled ...

'', Ante Pavelić

Ante Pavelić (; 14 July 1889 – 28 December 1959) was a Croatian politician who founded and headed the fascist ultranationalist organization known as the Ustaše in 1929 and served as dictator of the Independent State of Croatia ( hr, l ...

."''Poglavnik

() was the title used by Ante Pavelić, leader of the World War II Croatian movement Ustaše and of the Independent State of Croatia between 1941 and 1945.

Etymology and usage

The word was first recorded in a 16th-century dictionary compiled ...

''" was a term coined by the Ustaše

The Ustaše (), also known by anglicised versions Ustasha or Ustashe, was a Croats, Croatian Fascism, fascist and ultranationalism, ultranationalist organization active, as one organization, between 1929 and 1945, formally known as the Ustaš ...

, and it was originally used as the title for the leader of the movement. In 1941 it was institutionalized in the NDH as the title of first the Prime Minister (1941–1943), and then the head of state (1943–1945). It was at all times held by Ante Pavelić

Ante Pavelić (; 14 July 1889 – 28 December 1959) was a Croatian politician who founded and headed the fascist ultranationalist organization known as the Ustaše in 1929 and served as dictator of the Independent State of Croatia ( hr, l ...

(1889 – 1959) and became synonymous with him. The translation of the term varies. The root of the word is the Croatian word "''glava''", meaning "head" ("''Po''-''glav(a)''-''nik''"). The more literal translation is "head-man", while "leader" captures more of the meaning of the term (in relation to the German "''Führer

( ; , spelled or ''Fuhrer'' when the Umlaut (diacritic), umlaut is not available) is a German word meaning "leader" or "guide". As a political title, it is strongly associated with the Nazi Germany, Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler.

Nazi Germany ...

''" and Italian "''Duce

( , ) is an Italian title, derived from the Latin word 'leader', and a cognate of ''duke''. National Fascist Party leader Benito Mussolini was identified by Fascists as ('The Leader') of the movement since the birth of the in 1919. In 192 ...

''"). The regime targeted Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

, Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

*Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

as part of a large-scale campaign of genocide, as well as anti-fascist or dissident Croats and Bosnian Muslims

The Bosniaks ( bs, Bošnjaci, Cyrillic: Бошњаци, ; , ) are a South Slavic ethnic group native to the Southeast European historical region of Bosnia, which is today part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, who share a common Bosnian ancestry, cu ...

. According to Stanely G. Payne, “crimes in the NDH were proportionately surpassed only by Nazi Germany, the Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. ...

in Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand t ...

and several of the extremely genocidal

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

African regimes.”

In the territory controlled by the Independent State of Croatia, between 1941 and 1945, there existed 22 concentration camps. The largest camp was Jasenovac. Two camps, Jastrebarsko

Jastrebarsko (; hu, Jaska), colloquially known as Jaska, is a town in Zagreb County, Croatia.

History

Antiquity

In 1865, remnants of a Roman settlement were uncovered in Repišće, Klinča Sela, a village in Jastrebarsko metropolitan area ...

and Sisak, held only children.

The state was officially a monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

after the signing of the Laws of the Crown of Zvonimir

The Crown of Zvonimir was bestowed on King Dmitar Zvonimir of Croatia in 1076 by the papal legate. Zvonimir ruled Croatia until 1089 after which the crown was used in the coronation of his successor Stjepan II and presumably by the numerous H ...

on 15 May 1941.Hrvatski Narod (newspaper)16.05.1941. no. 93. p.1., Public proclamation of the''Zakonska odredba o kruni Zvonimirovoj'' (Decrees on the crown of Zvonimir), tri članka donesena 15.05.1941.Die Krone Zvonimirs, Monatshefte fur Auswartige Politik, Heft 6 (1941) pg. 434. Appointed by Victor Emmanuel III of Italy

Victor Emmanuel III (Vittorio Emanuele Ferdinando Maria Gennaro di Savoia; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. He also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia (1936–1941) and K ...

, Prince Aimone, Duke of Aosta

Prince Aimone, 4th Duke of Aosta (''Aimone Roberto Margherita Maria Giuseppe Torino''; 9 March 1900 – 29 January 1948) was a prince of Italy's reigning House of Savoy and an officer of the Royal Italian Navy. The second son of Prince Emanu ...

initially refused to assume the crown in opposition to the Italian annexation of the Croat-majority populated region of Dalmatia, annexed as part of the Italian irredentist

Italian irredentism ( it, irredentismo italiano) was a nationalist movement during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Italy with irredentist goals which promoted the unification of geographic areas in which indigenous peoples ...

agenda of creating a ''Mare Nostrum

''Mare Nostrum'' (; Latin: "Our Sea") was a Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Mediterranean Sea. In Classical Latin, it would have been pronounced , and in Ecclesiastical Latin, it is pronounced .

In the decades following the 1861 unification of ...

'' ("Our Sea"). He later briefly accepted the throne due to pressure from Victor Emmanuel III and was titled Tomislav II of Croatia, but never moved from Italy to reside in Croatia.

From the signing of the Treaties of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was sig ...

on 18 May 1941 until the Italian capitulation

The Armistice of Cassibile was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 and made public on 8 September between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II.

It was signed by Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allies and Brig ...

on 8 September 1943, the state was a territorial condominium of Germany and Italy. "Thus on 15 April 1941, Pavelić came to power, albeit a very limited power, in the new Ustasha state under the umbrella of German and Italian forces. On the same day German ''Führer

( ; , spelled or ''Fuhrer'' when the Umlaut (diacritic), umlaut is not available) is a German word meaning "leader" or "guide". As a political title, it is strongly associated with the Nazi Germany, Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler.

Nazi Germany ...

'' Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and Italian ''Duce

( , ) is an Italian title, derived from the Latin word 'leader', and a cognate of ''duke''. National Fascist Party leader Benito Mussolini was identified by Fascists as ('The Leader') of the movement since the birth of the in 1919. In 192 ...

'' Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

granted recognition to the Croatian state and declared that their governments would be glad to participate with the Croatian government in determining its frontiers."Frucht, Richard C. (2005). ''Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture''. p. 429. ABC-CLIO; "The NDH was in fact an Italo-German condominium. Both Nazi Germany and fascist Italy had spheres of influence in the NDH and stationed their own troops there." In its judgement in the

Hostages Trial

The Hostages Trial (or, officially, ''The United States of America v. Wilhelm List, et al.'') was held from

8 July 1947 until 19 February 1948 and was the seventh of the twelve trials for war crimes that United States authorities held in their occ ...

, the Nuremberg Military Tribunal

The subsequent Nuremberg trials were a series of 12 military tribunals for war crimes against members of the leadership of Nazi Germany between December 1946 and April 1949. They followed the first and best-known Nuremberg trial before the Int ...

concluded that NDH was not a sovereign state. According to the Tribunal, "Croatia was at all times here involved an occupied country".

In 1942, Germany suggested Italy take military control of all of Croatia out of a desire to redirect German troops from Croatia to the Eastern Front. Italy however rejected the offer as it did not believe that it could on its own handle the unstable situation in the Balkans. After the ousting of Mussolini and the Kingdom of Italy's armistice with the Allies, Tomislav II abdicated from his Croatian throne: the NDH on 10 September 1943 declared that the Treaties of Rome were null and void

In law, void means of no legal effect. An action, document, or transaction which is void is of no legal effect whatsoever: an absolute nullity—the law treats it as if it had never existed or happened. The term void ''ab initio'', which means " ...

and annexed the portion of Dalmatia that had been ceded to Italy. The NDH attempted to annex Zara (modern-day Zadar

Zadar ( , ; historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian: ); see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited Croatian city. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar serv ...

, Croatia), which had been a recognized territory of Italy since 1920 and long an object of Croatian irredentism, but Germany did not allow it.

Geography

Geographically, the NDH encompassed most of modern-dayCroatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

, all of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and H ...

, part of modern-day Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

, and a small portion of modern-day Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, an ...

in the Municipality of Brežice

The Municipality of Brežice (; sl, Občina Brežice) is a municipality in eastern Slovenia in the Lower Sava Valley along the border with Croatia. The seat of the municipality is the town of Brežice. The area was traditionally divided between ...

. It bordered Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

to the north-west, the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

to the north-east, the Serbian administration (a joint German-Serb government) to the east, Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

(an Italian protectorate) to the south-east and Fascist Italy along its coastal area.

Establishment of borders

The exact borders of the Independent State of Croatia were unclear when it was established. Approximately one month after its formation, significant areas of Croat-populated territory were ceded to itsAxis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

allies, the Kingdoms of Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

.

*On 13 May 1941, the NDH government signed an agreement with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

which demarcated their borders.

*On 18 May the Treaties of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was sig ...

were signed by diplomats of the NDH and Italy. Large parts of Croatian lands were occupied (annexed) by Italy, including most of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

(including Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, enterta ...

and Šibenik

Šibenik () is a historic city in Croatia, located in central Dalmatia, where the river Krka flows into the Adriatic Sea. Šibenik is a political, educational, transport, industrial and tourist center of Šibenik-Knin County, and is also the ...

), nearly all the Adriatic islands (including Rab

Rab �âːb( dlm, Arba, la, Arba, it, Arbe, german: Arbey) is an island in the northern Dalmatia region in Croatia, located just off the northern Croatian coast in the Adriatic Sea.

The island is long, has an area of and 9,328 inhabitants (2 ...

, Krk

Krk (; it, Veglia; ruo, Krk; dlm, label= Vegliot Dalmatian, Vikla; la, Curicta; grc-gre, Κύρικον, Kyrikon) is a Croatian island in the northern Adriatic Sea, located near Rijeka in the Bay of Kvarner and part of Primorje-Gorski Kot ...

, Vis, Korčula

Korčula (, it, Curzola) is a Croatian island in the Adriatic Sea. It has an area of , is long and on average wide, and lies just off the Dalmatian coast. Its 15,522 inhabitants (2011) make it the second most populous Adriatic island after K ...

, Mljet

Mljet (; la, Melita, it, Meleda) is the southernmost and easternmost of the larger Adriatic islands of the Dalmatia region of Croatia. The National Park includes the western part of the island, Veliko jezero, Malo jezero, Soline Bay and a sea be ...

), and some smaller areas such as the Bay of Kotor

The Bay of Kotor ( Montenegrin and Serbian: , Italian: ), also known as the Boka, is a winding bay of the Adriatic Sea in southwestern Montenegro and the region of Montenegro concentrated around the bay. It is also the southernmost part of the hi ...

, parts of the Croatian Littoral

Croatian Littoral ( hr, Hrvatsko primorje) is a historical name for the region of Croatia comprising mostly the coastal areas between traditional Dalmatia to the south, Mountainous Croatia to the north, Istria and the Kvarner Gulf of the Adriat ...

and Gorski kotar areas.

*On 7 June the NDH government issued a decree that demarcated its eastern border with Serbia.

*On 27 October the NDH and Italy reached an agreement on the Independent State of Croatia's border with Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

.

*On 8 September 1943, Italy capitulated and the NDH officially considered the Treaties of Rome to be void, along with the Treaty of Rapallo Following World War I there were two Treaties of Rapallo, both named after Rapallo, a resort on the Ligurian coast of Italy:

* Treaty of Rapallo, 1920, an agreement between Italy and the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the later Yugoslav ...

of 1920 which had given Italy Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

, Fiume (now Rijeka

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Primor ...

) and Zara (Zadar

Zadar ( , ; historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian: ); see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited Croatian city. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar serv ...

).Kisić-Kolanović, Nada. ''Mladen Lorković-ministar urotnik'', Golden Marketing, Zagreb (1997), pp. 304–06.

German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

approved the NDH acquisition of the Dalmatian territories gained by Italy at the time of the Treaties of Rome. By now, most such territory was actually controlled by the Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Slovene: , or the National Liberation Army, sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska (NOV), Народноослободилачка војска (НОВ); mk, Народноослобод ...

, since the ceding of those areas had made them strongly anti-NDH (more than one third of the total population of Split is documented to have joined the Partisans). By 11 September 1943, NDH foreign minister Mladen Lorković

Mladen Lorković (1 March 1909 – April 1945) was a Croatian politician and lawyer who became a senior member of the Ustaše and served as the Foreign Minister and Minister of Interior of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) during World ...

received word from German consul Siegfried Kasche

Siegfried Kasche (18 June 1903 – 7 June 1947) was an ambassador of the German Reich to the Independent State of Croatia and ''Obergruppenführer'' of the ''Sturmabteilung'' (SA), a paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party. Kasche was the proposed ru ...

that the NDH should wait before moving on Istria. Germany's central government had already annexed Istria and Fiume (Rijeka

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Primor ...

) into the Operational Zone Adriatic Coast a day earlier.

Međimurje and southern Baranja were annexed (occupied) by the Kingdom of Hungary. NDH disputed this and continued to lay claim to both, naming the administrative province centred in Osijek as ''Great Parish Baranja''. This border was never legislated, although Hungary may have considered the Pacta conventa

''Pacta conventa'' (Latin for "articles of agreement") was a contractual agreement, from 1573 to 1764 entered into between the "Polish nation" (i.e., the szlachta (nobility) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) and a newly elected king upon ...

to be in effect, which delineated the two nation's borders along the river.

When compared to the republic borders established in the SFR Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yug ...

after the war, the NDH encompassed the whole of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with its non-Croat (Serb

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

and Bosniak

The Bosniaks ( bs, Bošnjaci, Cyrillic: Бошњаци, ; , ) are a South Slavic ethnic group native to the Southeast European historical region of Bosnia, which is today part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, who share a common Bosnian ancestry, cu ...

) majority, as well as some 20 km2 of Slovenia (the villages of Slovenska Vas, Nova Vas pri Mokricah, Jesenice

Jesenice (, german: Aßling''Leksikon občin kraljestev in dežel zastopanih v državnem zboru'', vol. 6: Kranjsko. 1906. Vienna: C. Kr. Dvorna in Državna Tiskarna, p. 144.) is a Slovenian town and the seat of the Municipality of Jesenice on the ...

, Obrežje, and Čedem) and the whole of Syrmia

Syrmia ( sh, Srem/Срем or sh, Srijem/Сријем, label=none) is a region of the southern Pannonian Plain, which lies between the Danube and Sava rivers. It is divided between Serbia and Croatia. Most of the region is flat, with the exce ...

(part of which was previously in the Danube Banovina).

Administrative divisions

The Independent State of Croatia had four levels of administrative divisions: great parishes (velike župe), districts (kotari), cities (gradovi) and municipalities (opcine). At the time of its foundation, the state had 22 great parishes, 142 districts, 31 cities and 1006 municipalities. The highest level of administration were the great parishes (Velike župe), each of which was headed by aGrand Župan Grand, Great or Chief Župan ( sr, Велики жупан/Veliki župan, lat, magnus iupanus, gr, ζουπανος μεγας, ''zoupanos megas'') is the English rendering of a South Slavic Serbian title which relate etymologically to ''Župan' ...

. After the capitulation of Italy, NDH were permitted by the Germans to annex parts of the areas of Yugoslavia previously occupied by Italy. To accommodate this, parish boundaries were changed and the new parish of Sidraga-Ravni Kotari was created. In addition, on 29 October 1943, the Kommissariat of Sušak-Krk (Croatian: Građanska Sušak-Rijeka) was created separately by the Germans to act as a buffer zone between the NDH and RSI in the Fiume area to "perceive the special interests of the local population against the alians"

History

Influences on the rise of the Ustaše

In 1915 a group of political emigres from Austria-Hungary, predominantly Croats but including some Serbs and a Slovene, formed themselves into aYugoslav Committee

Yugoslav Committee ( sh-Latn, Jugoslavenski odbor, sr-Cyrl, Југословенски одбор) was a political interest group formed by South Slavs from Austria-Hungary during World War I aimed at joining the existing south Slavic nations in ...

, with a view to creating a South Slav state in the aftermath of World War I. They saw this as a way to prevent Dalmatia being ceded to Italy under the Treaty of London (1915)

The Treaty of London ( it, Trattato di Londra) or the Pact of London () was a secret agreement concluded on 26 April 1915 by the United Kingdom, France, and Russia on the one part, and Italy on the other, in order to entice the latter to enter ...

. In 1918, the National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs sent a delegation to the Serbian monarch to offer unification of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs

The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( sh, Država Slovenaca, Hrvata i Srba / ; sl, Država Slovencev, Hrvatov in Srbov) was a political entity that was constituted in October 1918, at the end of World War I, by Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( ...

with the Kingdom of Serbia

The Kingdom of Serbia ( sr-cyr, Краљевина Србија, Kraljevina Srbija) was a country located in the Balkans which was created when the ruler of the Principality of Serbia, Milan I, was proclaimed king in 1882. Since 1817, the Princi ...

.

The leader of the Croatian Peasant Party

The Croatian Peasant Party ( hr, Hrvatska seljačka stranka, HSS) is an agrarian political party in Croatia founded on 22 December 1904 by Antun and Stjepan Radić as Croatian Peoples' Peasant Party (HPSS). The Brothers Radić believed that t ...

, Stjepan Radić, warned on their departure for Belgrade that the council had no democratic legitimacy. But a new state, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

, was duly proclaimed on 1 December 1918, with no heed taken of legal protocols such as the signing of a new ''Pacta conventa

''Pacta conventa'' (Latin for "articles of agreement") was a contractual agreement, from 1573 to 1764 entered into between the "Polish nation" (i.e., the szlachta (nobility) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) and a newly elected king upon ...

'' in recognition of historic Croatian state rights.

Croats were at the outset politically disadvantaged with the centralized political structure of the kingdom, which was seen as favouring the Serb majority. The political situation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes was fractious and violent. In 1927, the Independent Democratic Party, which represented the Serbs of Croatia

The Serbs of Croatia ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, separator=" / ", Срби у Хрватској, Srbi u Hrvatskoj) or Croatian Serbs ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, separator=" / ", хрватски Срби, hrvatski Srbi) constitute the largest national minority in Croa ...

, turned its back on the centralist policy of King Alexander and entered into a coalition with the Croatian Peasant Party.

On 20 June 1928, Stjepan Radić and four other Croat deputies were shot while in the Belgrade parliament by a member of the Serbian People's Radical Party. Three of the deputies, including Radić, died. The outrage that resulted from the assassination of Stjepan Radić

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have a ...

threatened to destabilise the kingdom.

In January 1929, King Alexander responded by proclaiming a royal dictatorship, under which all dissenting political activity was banned and the state was renamed the "Kingdom of Yugoslavia". The Ustaša was created in principle in 1929.

One consequence of Alexander's 1929 proclamation and the repression and persecution of Croatian nationalists was a rise of support for the Croatian extreme nationalist, Ante Pavelić

Ante Pavelić (; 14 July 1889 – 28 December 1959) was a Croatian politician who founded and headed the fascist ultranationalist organization known as the Ustaše in 1929 and served as dictator of the Independent State of Croatia ( hr, l ...

, who had been a Zagreb deputy in the Yugoslav parliament, He was later implicated in Alexander's assassination in 1934, went into exile in Italy and gained support for his vision of liberating Croatia from Serb control and racially "purifying" Croatia. While residing in Italy, Pavelić and other Croatian exiles planned the Ustaša insurgency.

Establishment of the NDH

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 unt ...

in 1941, and the quick defeat of the Royal Yugoslav Army

The Yugoslav Army ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Jugoslovenska vojska, JV, Југословенска војска, ЈВ), commonly the Royal Yugoslav Army, was the land warfare military service branch of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (originally Kingdom of Serbs ...

(''Jugoslavenska Vojska''), the country was occupied by Axis forces. The Axis powers offered Vladko Maček

Vladimir Maček (20 June 1879 – 15 May 1964) was a politician in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. As a leader of the Croatian Peasant Party (HSS) following the 1928 assassination of Stjepan Radić, Maček had been a leading Croatian political fig ...

the opportunity to form a government, since Maček and his party, the Croatian Peasant Party ( hr, links=no, Hrvatska seljačka stranka – HSS) had the greatest electoral support among Yugoslavia's Croats – but Maček refused that offer.

On 10 April 1941 the German army took the control in Zagreb and supported Ustasha and retired lieutenant-colonel Slavko Kvaternik

Slavko Kvaternik (25 August 1878 – 7 June 1947) was a Croatian Ustaše military general and politician who was one of the founders of the Ustaše movement. Kvaternik was military commander and Minister of '' Domobranstvo'' (''Armed Forces''). O ...

to declare creation of the Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna država Hrvatska – NDH) "in the name of Croats and the header (poglavnik) Ante Pavelić". A few days later on 15 April 1941 Ante Pavelić returned to Zagreb and on 16 April 1941 he took the power as the State Leader, or the "Header" (Poglavnik), and the prime minister.

Slavko Kvaternik

Slavko Kvaternik (25 August 1878 – 7 June 1947) was a Croatian Ustaše military general and politician who was one of the founders of the Ustaše movement. Kvaternik was military commander and Minister of '' Domobranstvo'' (''Armed Forces''). O ...

, deputy leader of the Ustaše

The Ustaše (), also known by anglicised versions Ustasha or Ustashe, was a Croats, Croatian Fascism, fascist and ultranationalism, ultranationalist organization active, as one organization, between 1929 and 1945, formally known as the Ustaš ...

, proclaimed the establishment of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH – Nezavisna Država Hrvatska) on 10 April 1941 at 16:10. Pavelić, who was known by his Ustaše title, "''Poglavnik''", returned to Zagreb

Zagreb ( , , , ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slop ...

from exile in Italy on 17 April and became the absolute leader of the NDH throughout its existence.

Acceding to the demands of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

and the Fascist regime in the Kingdom of Italy, Pavelić reluctantly accepted Aimone the 4th Duke of Aosta as a figurehead

In politics, a figurehead is a person who ''de jure'' (in name or by law) appears to hold an important and often supremely powerful title or office, yet ''de facto'' (in reality) exercises little to no actual power. This usually means that they ...

King of the NDH under his new royal name, Tomislav II. Aosta was not interested in being the figurehead King of Croatia:

Upon learning he had been named King of Croatia, he told close colleagues that he thought his nomination was a bad joke by his cousin King Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

though he accepted the crown out of a sense of duty. He never visited the NDH and had no influence over the government, which was dominated by Pavelić.

From a strategic perspective, the establishment of the NDH was an attempt by Mussolini and Hitler to pacify the Croats, while reducing the use of Axis resources, which were more urgently needed for Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

. Meanwhile, Mussolini used his long-established support for Croatian independence as leverage to coerce Pavelić into signing an agreement on 18 May 1941 at 12:30, under which central Dalmatia and parts of Hrvatsko primorje

Croatian Littoral ( hr, Hrvatsko primorje) is a historical name for the region of Croatia comprising mostly the coastal areas between traditional Dalmatia to the south, Mountainous Croatia to the north, Istria and the Kvarner Gulf of the Adria ...

and Gorski kotar were ceded to Italy.

Under the same agreement, the NDH was restricted to a minimal navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral zone, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and ...

and Italian forces were granted military control of the entire Croatian coastline. After Pavelić signed the agreement, other Croatian politicians rebuked him. Pavelić publicly defended the decision and thanked Germany and Italy for supporting Croatian independence. Tanner, 1997, p. 147

After refusing leadership of the NDH, Maček called on all to obey and cooperate with the new government. The Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

was also openly supportive of the government. According to Maček, the new state was greeted with a "wave of enthusiasm" in Zagreb, often by people "blinded and intoxicated" by the fact that the Nazi Germany had "gift-wrapped their occupation under the euphemistic title of ''Independent State of Croatia''". But in the villages, Maček wrote, the peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

ry believed that "their struggle over the past 30 years to become masters of their homes and their country had suffered a tremendous setback".

On 16 August 1941, the Ustasha Surveillance Service was established, consisting of four departments, the ''Ustasha Police'', the ''Ustasha Intelligence Service'', ''Ustasha Defense'', and ''Personnel'', for the suppression of activities against the Ustasha, the Independent State of Croatia, and the Croatia people. The Service was eliminated as a separate agency in January 1943 and functions were transferred to the Ministry of Interior under the ''Directorate of Public Order''.

Dissatisfied with the Pavelić regime in its early months, the Axis Powers in September 1941 asked Maček to take over, but Maček again refused. Perceiving Maček as a potential rival, Pavelić subsequently had him arrested and interned in the

On 16 August 1941, the Ustasha Surveillance Service was established, consisting of four departments, the ''Ustasha Police'', the ''Ustasha Intelligence Service'', ''Ustasha Defense'', and ''Personnel'', for the suppression of activities against the Ustasha, the Independent State of Croatia, and the Croatia people. The Service was eliminated as a separate agency in January 1943 and functions were transferred to the Ministry of Interior under the ''Directorate of Public Order''.

Dissatisfied with the Pavelić regime in its early months, the Axis Powers in September 1941 asked Maček to take over, but Maček again refused. Perceiving Maček as a potential rival, Pavelić subsequently had him arrested and interned in the Jasenovac concentration camp

Jasenovac () was a concentration camp, concentration and extermination camps, extermination camp established in the Jasenovac, Sisak-Moslavina County, village of the same name by the authorities of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) in I ...

. The Ustaše initially did not have an army or administration capable of controlling all the territory of the NDH. The Ustaše movement had fewer than 12,000 members when the war started. While the Ustaše's own estimates put the number of their sympathizers even in the early phase at around 40,000.

To act against Serbs and Jews with genocidal measures, the Ustase introduced widespread measures that Croats themselves were victim to. Jozo Tomasevich in his book, ''War and Revolution in Yugoslavia: 1941-1945'', states, ''"never before in history had Croats been exposed to such legalized administrative, police and judicial brutality and abuse as during the Ustasha regime."'' Decrees enacted by the regime allowed it to get rid of all 'unwanted' employees in state and local government and in state enterprises. The 'unwanted' (being all Jews, Serbs, and Yugoslav-oriented Croats) were all thrown out except for some deemed specifically needed by the government. This left a multitude of jobs to be filled by Ustashas and pro-Ustasha adherents and led to government jobs being filled by people with no professional qualifications.

Italian influence

Mussolini and Ante Pavelić had close relations prior to the war. Mussolini and Pavelić both despised the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Italy had been promised, in the Treaty of London (1915), that it would receive Dalmatia from Austria-Hungary at the end of World War I. The peace negotiations in 1919, however, influenced by theFourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

proclaimed by US President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

(1856–1924), called for national self-determination and determined that the Yugoslavs rightfully deserved the territory in question. Italian nationalists were enraged. Italian nationalist Gabriele D'Annunzio raided Fiume

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Primor ...

(which held a mixed population of Croats and Italians) and proclaimed it part of the Italian Regency of Carnaro

The Italian Regency of Carnaro ( it, Reggenza Italiana del Carnaro), also known in Italian as (), was a self-proclaimed state in the city of Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia) led by Gabriele d'Annunzio between 1919 and 1920.

''Impresa di Fiume''

...

. D'Annunzio declared himself "Duce

( , ) is an Italian title, derived from the Latin word 'leader', and a cognate of ''duke''. National Fascist Party leader Benito Mussolini was identified by Fascists as ('The Leader') of the movement since the birth of the in 1919. In 192 ...

" of Carnaro and his blackshirted revolutionaries held control over the town. D'Annunzio was known for engaging in passionate speeches aimed to draw Croatian nationalists to support his actions and to oppose Yugoslavia.

Croatian nationalists, such as Pavelić, opposed the border changes that occurred after World War I. Not only was D'Annunzio's symbolism copied by Mussolini but also D'Annunzio's appeal to Croatian support for the dismantling of Yugoslavia, as a foreign policy approach to Yugoslavia by Mussolini. Pavelić had been in negotiations with Italy since 1927 that included advocating a territory-for-sovereignty swap in which he would tolerate Italy annexing its claimed territory in Dalmatia in exchange for Italy supporting the sovereignty of an independent Croatia.

In the 1930s, upon Pavelić and the Ustaše being forced into exile by the Yugoslav government, they were offered sanctuary in Italy by Mussolini, who allowed them to use training grounds to prepare for war against Yugoslavia. In exchange for this support, Mussolini demanded that Pavelić agree that Dalmatia would become part of Italy if Italy and the Ustaše successfully waged war on Yugoslavia. Although Dalmatia was a largely Croat-populated territory, it had been part of various Italian states, such as the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

and the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

in prior centuries and was part of Italian nationalism

Italian nationalism is a movement which believes that the Italians are a nation with a single homogeneous identity, and therefrom seeks to promote the cultural unity of Italy as a country. From an Italian nationalist perspective, Italianness is ...

's irredentist claims.

In exchange for this concession, Mussolini offered Pavelić the right for Croatia to annex all of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which had only a minority Croat population. Pavelić agreed. After the invasion and occupation of Yugoslavia, Italy annexed numerous Adriatic islands

There are more than 1200 islands in the Adriatic Sea, 69 of which are inhabited. A recent study by the Institute of Oceanography in Split (2000) shows that there are 1246 islands: 79 large islands, 525 islets, and 642 ridges and rocks. The Italia ...

and a portion of Dalmatia, which all combined to become the Italian Governorship of Dalmatia

The Governorate of Dalmatia ( it, Governatorato di Dalmazia) was a territory divided into three provinces of Italy during the Italian Kingdom and Italian Empire epoch. It was created later as an entity in April 1941 at the start of World War I ...

including territory from the provinces of Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, enterta ...

, Zadar

Zadar ( , ; historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian: ); see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited Croatian city. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar serv ...

, and Kotor

Kotor (Montenegrin Cyrillic: Котор, ), historically known as Cattaro (from Italian: ), is a coastal town in Montenegro. It is located in a secluded part of the Bay of Kotor. The city has a population of 13,510 and is the administrative c ...

.Rodogno, Davide. ''Fascism's European empire: Italian occupation during the Second World War'', Cambridge University Press, UK (2006), pp. 80–81.

Although Italy had initially larger territorial aims that extended from the Velebit mountains to the Albanian Alps

The Accursed Mountains ( sq, Bjeshkët e Nemuna; sh-Cyrl-Latn, Проклетије, Prokletije, ; both translated as "Cursed Mountains"), also known as the Albanian Alps ( sq, Alpet Shqiptare), are a mountain group in the western part of the B ...

, Mussolini decided against annexing further territories due to a number of factors, including that Italy held the economically valuable portion of that territory within its possession while the northern Adriatic coast had no important railways or roads and because a larger annexation would have included hundreds of thousands of Slavs who were hostile to Italy, within its national borders.

Italy intended to keep the NDH within its sphere of influence by forbidding it to build any significant navy. Italy only permitted small patrol boats to be used by NDH forces. This policy forbidding the creation of NDH warships was part of the Italian Fascists' policy of ''Mare Nostrum

''Mare Nostrum'' (; Latin: "Our Sea") was a Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Mediterranean Sea. In Classical Latin, it would have been pronounced , and in Ecclesiastical Latin, it is pronounced .

In the decades following the 1861 unification of ...

'' (Latin for "Our Sea") in which Italy was to dominate the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

as the Roman Empire had done centuries earlier. Italian armed forces assisted the Ustaše government in persecuting Serbs. In 1941, Italian forces captured and interned the Serbian Orthodox

The Serbian Orthodox Church ( sr-Cyrl, Српска православна црква, Srpska pravoslavna crkva) is one of the autocephalous (ecclesiastically independent) Eastern Orthodox Christian churches.

The majority of the population in ...

Bishop Irinej (Đorđević) of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

.Tanner, p. 151

Influence of Nazi Germany

At the time of the invasion of Yugoslavia by Nazi Germany,

At the time of the invasion of Yugoslavia by Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

was uneasy with Mussolini's agenda of creating a puppet Croatian state, and preferred that areas outside of Italian territorial aims become part of Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

as an autonomous territory. This would appease Nazi Germany's ally Hungary and its nationalist territorial claims. Germany's position on Croatia changed after its invasion of Yugoslavia

The invasion of Yugoslavia, also known as the April War or Operation 25, or ''Projekt 25'' was a German-led attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers which began on 6 April 1941 during World War II. The order for the invasion was p ...

in 1941. The invasion was spearheaded by a strong German invasion force which was largely responsible for the capture of Yugoslavia. Military forces from other Axis powers, including Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

made few gains during the invasion.

The invasion was precipitated by the need for German forces to reach Greece to save Italian forces, which were failing on the battlefield against the Greek armed forces

The Hellenic Armed Forces ( el, Eλληνικές Ένοπλες Δυνάμεις, Ellinikés Énoples Dynámis) are the military forces of Greece. They consist of the Hellenic Army, the Hellenic Navy, and the Hellenic Air Force.

The civilian a ...

. Upon rescuing Italian forces in Greece and having conquered Yugoslavia and Greece almost single-handedly, Hitler became frustrated with Mussolini and Italy's military incompetence. Germany improved relations with the Ustaše and supported the NDH claims to annex the Adriatic Coast in order reduce Italy's planned territorial gains. Nevertheless, Italy annexed a significant central portion of Dalmatia and various Adriatic Islands. This was not what had been agreed with Pavelić prior to the invasion; Italy had expected to annex all of Dalmatia as part of its irredentist claims.

Hitler sparred with his army commanders over what policy should be undertaken in Croatia regarding the Serbs. German military officials thought that Serbs could be rallied to fight against the Partisans. Hitler disagreed with his commanders, but pointed out to Pavelić that the NDH could create a completely Croat state only if it followed a constant policy of persecution of the non-Croat population for at least fifty years. The NDH was never fully sovereign, but it was a puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a State (polity), state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside Power (international relations), power and subject to its o ...

that enjoyed greater autonomy than any other regime in German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

.

As early as 10 July 1941, Wehrmacht General Edmund Glaise von Horstenau reported the following to the German High Command, the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW):

The Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

report to Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

, dated 17 February 1942, states:

According to reports by General Glaise-Horstenau, Hitler was angry with Pavelić, whose policy inflamed the rebellion in Croatia, thwarting any prospect of deploying NDH forces on the Eastern Front.Ivanković, Zvonko. ''Hebrang'', Scientia Yugoslavica 1988, pp. 169–70 Moreover, Hitler was forced to engage large forces of his own to keep the rebellion in check. For that reason, Hitler summoned Pavelić to his war headquarters in Vinnytsia

Vinnytsia ( ; uk, Вінниця, ; yi, װיניצע) is a city in west-central Ukraine, located on the banks of the Southern Bug.

It is the administrative center of Vinnytsia Oblast and the largest city in the historic region of Podillia. A ...

(Ukraine) on 23 September 1942. Consequently, Pavelić replaced his minister of the Armed Forces, Slavko Kvaternik, with the less zealous Jure Francetić. Kvaternik was sent into exile in Slovakia – along with his son Eugen, who was blamed for the persecution of the Serbs in Croatia. Before meeting Hitler, to appease the public, Pavelić published an "Important Government Announcement" (»Važna obavijest Vlade«), in which he threatened those who were spreading the news "about non-existent threats of disarmament of the Ustashe units by representatives of one foreign power, about the Croatian Army replacement by a foreign army, about the possibility that a foreign power would seize the power in Croatia ..."

General Glaise-Horstenau reported: "The Ustaše movement is, due to the mistakes and atrocities they have committed and the corruption, so compromised that the government executive branch (the home guard and the police) shall be separated from the government – even for the price of breaking any possible connection with the government."

Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler is quoted characterizing the Independent State of Croatia as "ridiculous": "our beloved German settlements will be secured. I hope that the area south of Srem will be liberated by ... the Bosnian division ... so that we can at least restore partial order in this ridiculous (Croatian) state."

The Ustaše gained German support for plans to eliminate the Serb population in Croatia. One plan involved an exchange in 1941 between Germany and the NDH, in which 20,000 Catholic Slovenes would be deported from German-held Slovenia and sent to the NDH where they would be assimilated as Croats. In exchange, 20,000 Serbs would be deported from the NDH and sent to the German-occupied territory of Serbia. On the meeting with Hitler on 6 June 1941 in

General Glaise-Horstenau reported: "The Ustaše movement is, due to the mistakes and atrocities they have committed and the corruption, so compromised that the government executive branch (the home guard and the police) shall be separated from the government – even for the price of breaking any possible connection with the government."

Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler is quoted characterizing the Independent State of Croatia as "ridiculous": "our beloved German settlements will be secured. I hope that the area south of Srem will be liberated by ... the Bosnian division ... so that we can at least restore partial order in this ridiculous (Croatian) state."

The Ustaše gained German support for plans to eliminate the Serb population in Croatia. One plan involved an exchange in 1941 between Germany and the NDH, in which 20,000 Catholic Slovenes would be deported from German-held Slovenia and sent to the NDH where they would be assimilated as Croats. In exchange, 20,000 Serbs would be deported from the NDH and sent to the German-occupied territory of Serbia. On the meeting with Hitler on 6 June 1941 in Salzburg

Salzburg (, ; literally "Salt-Castle"; bar, Soizbuag, label=Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian) is the List of cities and towns in Austria, fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020, it had a population of 156,872.

The town is on the site of the ...

, Pavelić agreed to receive 175,000 deported Slovenes. The agreement provided that the number of Serbs deported from NDH to Serbia could exceed the number of Slovenes received by 30,000. During the talks, Hitler stressed the necessity and desirability of deportations of Slovenes and Serbs, and advised Pavelic that NDH, in order to become stable, should carry on ethnically intolerant policy for the next 50 years. The German occupation forces allowed the expulsion of Serbs to Serbia, but instead of sending the Slovenes to Croatia, they were also deported to Serbia. In total, about 300,000 Serbs had been deported or fled from the NDH to Serbia by the end of World War II.

The atrocities committed by the Ustaše stunned observers; Brigadier Sir Fitzroy Maclean, Chief of the British military mission to the Partisans, commented "Some Ustaše collected the eyes of Serbs they had killed, sending them, when they had enough, to the Poglavnik '' head-man'' for his inspection or proudly displaying them and other human organs in the cafés of Zagreb."

The Nazi regime demanded that the Ustaše adopt antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

racial policies, persecute Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and set up several concentration camps. Pavelic and the Ustaše accepted Nazi demands, but their racial policy focused primarily on eliminating the Serb population. When the Ustaše needed more recruits to help exterminate the Serbs, the state broke away from Nazi antisemitic policy by promising honorary Aryan citizenship, and, thus, freedom from persecution, to Jews who were willing to fight for the NDH. Tanner, 1997, p. 149 As this was the only legal means allowing Jews to escape persecution, a number of Jews joined the NDH's armed forces. This aggravated the German SS, which claimed that the NDH let 5,000 Jews survive via service in the NDH's armed forces.

German anti-Semitic objectives for Croatia were further undermined by Italy's reluctance to adhere to a strict antisemitic policy, which resulted in Jews in Italian-held parts of Croatia avoiding the same persecution facing Jews in German-held eastern Croatia. After Italy abandoned the war in 1943, German forces occupied western Croatia and the NDH annexed the territory ceded to Italy in 1941.

Within just a few days of the creation of the NDH, Croatian workers were requisitioned by the Reich for cheap forced labour and slave labour. From 1942 onward, German and Croat authorities cooperated more closely in deporting "unwanted" Croats and Serbs to concentration camps in the Reich and Norway for forced labour, such people were to be rounded up and deported by the General Plenipotentiary

A ''plenipotentiary'' (from the Latin ''plenus'' "full" and ''potens'' "powerful") is a diplomat who has full powers—authorization to sign a treaty or convention on behalf of his or her sovereign. When used as a noun more generally, the word ...

for Labour Deployment to the Reich (Arbeitseinsatz

''Arbeitseinsatz'' (german: for 'labour deployment') was a forced labour category of internment within Nazi Germany (german: Zwangsarbeit) during World War II. When German men were called up for military service, Nazi German authorities rounded ...

).

Between 1941 and 1945, some 200,000 Croatian citizens of the NDH (including ethnic Croats as well as ethnic Serbs with Croatian nationality and Slovenes) were sent to Germany to work as slave and forced labourers, mostly working in mining, agriculture and forestry. It is estimated that 153,000 of these labourers were said to have been "voluntarily" recruited, however in many instances this was not the case, as the workers that may have initially volunteered were forced to work longer hours and were paid less than their contracts had stipulated, they were also not allowed to return home after their yearly contract had ended, at which point their labour was no longer voluntary, but forced. Forced and slave labour were also conducted in Nazi concentration camps, such as in Buchenwald

Buchenwald (; literally 'beech forest') was a Nazi concentration camp established on hill near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within Germany's 1937 borders. Many actual or su ...

and Mittelbau-Dora.

From 1941 to 1945, 3.8% of the population of Croatia had been sent to the Reich to work, which was higher than the European average.

Partisan resistance

On 22 June 1941, the Sisak Partisan Detachment was formed in Brezovica forest near Sisak; this was to be celebrated as the first armed resistance unit formed in occupied Yugoslavia during World War II. Croats, Serbs, Bosniaks, and citizens of all nationalities and backgrounds began joining the pan-Yugoslav Partisans led byJosip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his deat ...

. The Partisan movement was soon able to control a large percentage of the NDH (and Yugoslavia) and before long the cities of occupied Bosnia and Dalmatia in particular were surrounded by these Partisan-controlled areas, with their garrisons living in a ''de facto'' state of siege and constantly trying to maintain control of the rail-links.

In 1944, the third year of the war in Yugoslavia, Croats formed 61% of the Partisan operational units originating from the Federal State of Croatia

The Socialist Republic of Croatia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Socijalistička Republika Hrvatska, Социјалистичка Република Хрватска), or SR Croatia, was a constituent republic and federated state of the Social ...

.

The Federal State of Croatia also had the highest number of detachments and brigades among the federal units, and together with the forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Partisan resistance in the NDH made up the majority of the movement's military strength. Partisan Marshal Tito, was half Croatian, half Slovene.

Relations with the Chetniks

After the 1941 split between the Partisans and the

After the 1941 split between the Partisans and the Chetniks

The Chetniks ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Четници, Četnici, ; sl, Četniki), formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nationa ...

in Serbia, the Chetnik groups in central, eastern and northwestern Bosnia found themselves caught between the German and Ustaše (NDH) forces on one side and the Partisans on the other. In early 1942 Chetnik Major Jezdimir Dangić

Jezdimir Dangić (; 4 May 1897 – 22 August 1947) was a Yugoslav and Bosnian Serb Chetnik commander during World War II. He was born in the town of Bratunac in the Austro-Hungarian occupied Bosnia Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire. Impriso ...

approached the Germans in an attempt to arrive at an understanding, but was unsuccessful, and the local Chetnik leaders were forced to look for another solution. Although the Ustaše and Chetniks were rival nationalists (Croatian and Serbian), they found a common enemy in the Partisans, and thwarting Partisan advances became the overriding reason for the collaboration which ensued between the Ustaše authorities of the Independent State of Croatia and Chetnik detachments in Bosnia.