Immigration to the United Kingdom since 1922 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Since 1945, immigration to the United Kingdom, controlled by British immigration law and to an extent by

Following the end of the Second World War, substantial groups of people from

Following the end of the Second World War, substantial groups of people from  By 1972, only holders of work permits, or people with parents or grandparents born in the UK could gain entry – significantly reducing primary immigration from Commonwealth countries.

By 1972, only holders of work permits, or people with parents or grandparents born in the UK could gain entry – significantly reducing primary immigration from Commonwealth countries.

The Immigration Rules, under the Immigration Act 1971, were updated in 2012 (Appendix FM) to create a strict minimum income threshold for non-EU spouses and children to be given leave to remain in the UK. These rules were challenged in the courts, and in 2017 the Supreme Court found that while "the minimum income threshold is accepted in principle" they decided that the rules and guidance were defective and unlawful until amended to give more weight to the interests of the children involved, and that sources of funding other than the British spouse's income should be considered.

The foreign-born population increased from about 5.3 million in 2004 to nearly 9.3 million in 2018. In the decade leading up to 2018, the number of non-EU migrants outnumbered EU migrants while the number of EU migrants increased more rapidly. EU migrants were noted to be less likely to become British citizens than non-EU migrants.

In January 2021, analysis by the Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence suggested that there had been an "unprecedented exodus" of almost 1.3 million foreign-born people from the UK between July 2019 and September 2020, in part due to the burden of job losses resulting from the

The Immigration Rules, under the Immigration Act 1971, were updated in 2012 (Appendix FM) to create a strict minimum income threshold for non-EU spouses and children to be given leave to remain in the UK. These rules were challenged in the courts, and in 2017 the Supreme Court found that while "the minimum income threshold is accepted in principle" they decided that the rules and guidance were defective and unlawful until amended to give more weight to the interests of the children involved, and that sources of funding other than the British spouse's income should be considered.

The foreign-born population increased from about 5.3 million in 2004 to nearly 9.3 million in 2018. In the decade leading up to 2018, the number of non-EU migrants outnumbered EU migrants while the number of EU migrants increased more rapidly. EU migrants were noted to be less likely to become British citizens than non-EU migrants.

In January 2021, analysis by the Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence suggested that there had been an "unprecedented exodus" of almost 1.3 million foreign-born people from the UK between July 2019 and September 2020, in part due to the burden of job losses resulting from the

One of the

One of the

"Managed migration" is the term for all legal labour and student migration from outside of the European Union and this accounts for a substantial percentage of overall immigration figures for the UK. Many of the immigrants who arrive under these schemes bring skills which are in short supply in the UK. This area of immigration is managed by

"Managed migration" is the term for all legal labour and student migration from outside of the European Union and this accounts for a substantial percentage of overall immigration figures for the UK. Many of the immigrants who arrive under these schemes bring skills which are in short supply in the UK. This area of immigration is managed by

The UK is a signatory to the UN

The UK is a signatory to the UN

Seeking scapegoats: The coverage of asylum in the UK press (PDF)

, Institute for Public Policy Research, May 2005 This is denounced, by those seeking to ensure that the UK upholds its international obligations, as disproportionate. Concern is also raised about the treatment of those held in detention and the practice of

Illegal immigrants in the UK include those who have:

* entered the UK without authority

* entered with false documents

* overstayed their visas

Although it is difficult to know how many people reside in the UK illegally, a Home Office study released in March 2005 estimated a population of between 310,000 and 570,000.

A recent study into irregular immigration states that "most irregular migrants have committed administrative offences rather than a serious crime".

Illegal immigrants in the UK include those who have:

* entered the UK without authority

* entered with false documents

* overstayed their visas

Although it is difficult to know how many people reside in the UK illegally, a Home Office study released in March 2005 estimated a population of between 310,000 and 570,000.

A recent study into irregular immigration states that "most irregular migrants have committed administrative offences rather than a serious crime".

Demography, State and Society: Irish Migration to Britain, 1921-1971

' (Montreal, 2000) * Delaney, Enda. ''The Irish in Post-War Britain'' (Oxford, 2007) * * * Hansen, Randall. ''Citizenship and Immigration in Post-war Britain: the Institutional Origins of a Multicultural Nation'' (Oxford, 2000), * Holmes, Colin.

John Bull's Island: Immigration and British Society, 1871-1971

' (Basingstoke, 1988) * * London, Louise. ''Whitehall & the Jews, 1933-1948: British Immigration Policy & the Holocaust'' (2000) * Longpré Nicole.

An issue that could tear us apart

: Race, Empire, and Economy in the British (Welfare) State, 1968," Canadian Journal of History (2011) 46#1 pp. 63–95. * * Panayi, Panikos.

Immigration, Ethnicity and Racism in Britain, 1815-1945

' (1994) * Paulo, Kathleen.

Whitewashing Britain: Race and Citizenship in the Postwar Era

' (Ithaca, 1997) * Peach, Ceri. ''West Indian Migration to Britain: A Social Geography'' (Oxford, 1968) * Proctor, James, ed.

Writing Black Britain, 1948-1998: An Interdisciplinary Anthology

' (Manchester, 2000), * Simkin, John (27 May 2018).

'. ''Spartacus Educational.'' Retrieved 6 June 2018 * Spencer, Ian R.G

British Immigration Policy since 1939: The Making of Multi-Racial Britain

' (London, 1997)

Born Abroad: An Immigration Map of Britain

(BBC, 2005)

Destination UK

(BBC News special, 2008)

Immigration & Nationality Directorate

at the Home Office

Migration Statistics at parliament.uk 17 June 2014

Now dead link, needs removing

Moving Here

the UK's biggest online database of digitised photographs, maps, objects, documents and audio items from 30 local and national archives, museums and libraries; recording migration experiences of the last 200 years

Summary of UK immigration rules

from the Home Office

Statement of Changes to the Immigration Rules HC 1078

{{OceanicsinUK Demographics of the United Kingdom, Immigration to History of immigration to the United Kingdom Immigration to the United Kingdom, Ethnic groups in the United Kingdom Multiracial affairs in Europe

British nationality law

British nationality law prescribes the conditions under which a person is recognised as being a national of the United Kingdom. The six different classes of British nationality each have varying degrees of civil and political rights, due to the ...

, has been significant, in particular from the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern ...

and from the former British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, especially India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

, the Caribbean, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

, Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

, Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

, Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

...

, and Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta i ...

. Since the accession of the UK to the European Communities in the 1970s and the creation of the EU in the early 1990s, immigrants relocated from member states of the European Union, exercising one of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

's Four Freedoms

The Four Freedoms were goals articulated by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Monday, January 6, 1941. In an address known as the Four Freedoms speech (technically the 1941 State of the Union address), he proposed four fundamental freed ...

. In 2021, since Brexit

Brexit (; a portmanteau of "British exit") was the withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU) at 23:00 GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February 2020 CET).The UK also left the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC ...

came into effect, previous EU citizenship's right to newly move to and reside in the UK on a permanent basis does not apply anymore. A smaller number have come as asylum seekers (not included in the definition of immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, a ...

) seeking protection as refugees under the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

1951 Refugee Convention

The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, also known as the 1951 Refugee Convention or the Geneva Convention of 28 July 1951, is a United Nations multilateral treaty that defines who a refugee is, and sets out the rights of individuals ...

.

About 70% of the population increase between the 2001 and 2011 census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses in ...

es was due to foreign-born immigration. 7.5 million people (11.9% of the population at the time) were born overseas, although the census gives no indication of their immigration status or intended length of stay.

Provisional figures show that in 2013, 526,000 people arrived to live in the UK whilst 314,000 left, meaning that net inward migration was 212,000. The number of people immigrating to the UK increased between 2012 and 2013 by 28,000, whereas the number emigrating fell by 7,000.

From April 2013 to April 2014, a total of 560,000 immigrants were estimated to have arrived in the UK, including 81,000 British citizens and 214,000 from other parts of the EU. An estimated 317,000 people left, including 131,000 British citizens and 83,000 other EU citizens. The top countries represented in terms of arrivals were: China, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, and Australia.

In 2014, approximately 125,800 foreign citizens were naturalised as British citizens. This figure fell from around 208,000 in 2013, which was the highest figure recorded since 1962, when records began. Between 2009 and 2013, the average number of people granted British citizenship per year was 195,800. The main countries of previous nationality of those naturalised in 2014 were: India, Pakistan, the Philippines, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Nepal, China, South Africa, Poland and Somalia. The UK Government can also grant settlement to foreign nationals, which confers on them permanent residence

''Permanent Residence'' () is a 2009 Hong Kong film starring Sean Li and Osman Hung. It was directed by Hong Kong filmmaker Danny Cheng, also known as Scud. The film explores several themes traditionally regarded as 'taboo' in Hong Kong societ ...

in the UK, without granting them British citizenship. Grants of settlement are made on the basis of various factors, including employment, family formation and reunification, and asylum (including to deal with backlogs of asylum cases). The total number of grants of settlement was approximately 154,700 in 2013, compared to 241,200 in 2010 and 129,800 in 2012.

In comparison, migration to and from Central and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

has increased since 2004 with the accession to the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

of eight Central and Eastern European states, since there is free movement of labour within the EU. In 2008, the UK Government began phasing in a new points-based immigration system

A points-based immigration system is an immigration system where a noncitizen's eligibility to immigrate is (partly or wholly) determined by whether that noncitizen is able to score above a threshold number of points in a scoring system that might ...

for people from outside of the European Economic Area

The European Economic Area (EEA) was established via the ''Agreement on the European Economic Area'', an international agreement which enables the extension of the European Union's single market to member states of the European Free Trade As ...

.

Definitions

According to an August 2018 publication of the House of Commons Library, several definitions for a migrant exist in United Kingdom. A migrant can be: * Someone whose country of birth is different to their country of residence. * Someone whose nationality is different to their country of residence. * Someone who changes their country of usual residence for a period of at least a year, so that the country of destination effectively becomes the country of usual residence.World War II

In the lead-up toWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, many people from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, particularly those belonging to minorities which were persecuted under Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

rule, such as Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s, sought to emigrate to the United Kingdom, and it is estimated that as many as 50,000 may have been successful. There were immigration caps on the number who could enter and, subsequently, some applicants were turned away. When the UK declared war on Germany, however, migration between the countries ceased.

British Empire and the Commonwealth

Following the end of theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, the British Nationality Act 1948

The British Nationality Act 1948 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom on British nationality law which defined British nationality by creating the status of "Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies" (CUKC) as the sole national ci ...

allowed the 800,000,000 subjects in the British Empire to live and work in the United Kingdom without needing a visa

Visa most commonly refers to:

*Visa Inc., a US multinational financial and payment cards company

** Visa Debit card issued by the above company

** Visa Electron, a debit card

** Visa Plus, an interbank network

*Travel visa, a document that allows ...

, although this was not an anticipated consequence of the Act, which "was never intended to facilitate mass migration". This migration was initially encouraged to help fill gaps in the UK labour market for both skilled and unskilled jobs, including in public services such as the newly created National Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) is the umbrella term for the publicly funded healthcare systems of the United Kingdom (UK). Since 1948, they have been funded out of general taxation. There are three systems which are referred to using the " ...

and London Transport. Many people were specifically brought to the UK on ships; notably the ''Empire Windrush

HMT ''Empire Windrush'', originally MV ''Monte Rosa'', was a passenger liner and cruise ship launched in Germany in 1930. She was owned and operated by the German shipping line in the 1930s under the name ''Monte Rosa''. During World War II she ...

'' in 1948.

Commonwealth immigration, made up largely of economic migrants

An economic migrant is someone who emigrates from one region to another, including crossing international borders, seeking an improved standard of living, because the conditions or job opportunities in the migrant's own region are insufficient. Th ...

, rose from 3,000 per year in 1953 to 46,800 in 1956 and 136,400 in 1961. The heavy numbers of migrants resulted in the establishment of a Cabinet committee in June 1950 to find "ways which might be adopted to check the immigration into this country of coloured people from British colonial territories".

Although the Committee recommended not to introduce restrictions, the Commonwealth Immigrants Act was passed in 1962 as a response to public sentiment that the new arrivals "should return to their own countries" and that "no more of them come to this country". Introducing the legislation to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

Rab Butler

Richard Austen Butler, Baron Butler of Saffron Walden, (9 December 1902 – 8 March 1982), also known as R. A. Butler and familiarly known from his initials as Rab, was a prominent British Conservative Party politician. ''The Times'' obituary c ...

stated that:

The new Act required migrants to have a job before they arrived, to possess special skills or who would meet the "labour needs" of the national economy. In 1965, to combat the perceived injustice in the case where the wives of British subjects could not obtain British nationality, the British Nationality Act 1965 was adopted. Shortly afterwards, refugees from Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

...

and Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The sou ...

, fearing discrimination from their own national governments, began to arrive in Britain; as they had retained their British nationality granted by the 1948 Act, they were not subject to the later controls. The Conservative MP Enoch Powell

John Enoch Powell, (16 June 1912 – 8 February 1998) was a British politician, classical scholar, author, linguist, soldier, philologist, and poet. He served as a Conservative Member of Parliament (1950–1974) and was Minister of Health (1 ...

campaigned for tighter controls on immigration which resulted in the passing of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act in 1968.

For the first time, the 1968 Act required migrants to have a "substantial connection with the United Kingdom", namely to be connected by birth or ancestry to a UK national. Those who did not could only obtain British nationality at the discretion of the national authorities. One month after the adoption of the Act, Enoch Powell made his Rivers of Blood speech

The "Rivers of Blood" speech was made by British Member of Parliament (MP) Enoch Powell on 20 April 1968, to a meeting of the Conservative Political Centre in Birmingham, United Kingdom. His speech strongly criticised mass immigration, especi ...

.

By 1972, with the passing of the Immigration Act

Immigration Act (with its variations) is a stock short title used for legislation in many countries relating to immigration.

The Bill for an Act with this short title will have been known as a Immigration Bill during its passage through Parliament ...

, only holders of work permits, or people with parents or grandparents born in the UK could gain entry – effectively stemming primary immigration from Commonwealth countries. The Act abolished the distinction between Commonwealth and non-Commonwealth entrants. The Conservative government nevertheless allowed, amid much controversy, the immigration of 27,000 individuals displaced from Uganda after the coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

led by Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 16 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. He ruled as a military dictator and is considered one of the most brutal despots in modern w ...

in 1971.

In the 1970s, an average of 72,000 immigrants were settling in the UK every year from the Commonwealth; this decreased in the 1980s and early-1990s to around 54,000 per year, only to rise again to around 97,000 by 1999. The total number of Commonwealth immigrants since 1962 is estimated at 2,500,000.

The Ireland Act 1949

The Ireland Act 1949 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to deal with the consequences of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948 as passed by the Irish parliament, the Oireachtas.

Background

Following the secession of most ...

has the unusual status of recognising the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern ...

, but affirming that its citizens are not citizens of a foreign country for the purposes of any law in the United Kingdom. This act was initiated at a time when Ireland withdrew from the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the ...

after declaring itself a republic.

Post-war immigration (1945–1983)

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

-controlled territories settled in the UK, particularly Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in C ...

and Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian. The majority of Ukrainians are Eastern Ort ...

. The UK recruited displaced people as so-called European Volunteer Workers in order to provide labour to industries that were required in order to aid economic recovery after the war. In the 1951 United Kingdom census, the Polish-born population of the country numbered some 162,339, up from 44,642 in 1931.

Indians began arriving in the UK in large numbers shortly after their country gained independence in 1947, although there were a number of people from India living in the UK even in the earlier years. More than 60,000 arrived before 1955, many of whom drove buses, or worked in foundries

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

or textile

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

factories. The flow of Indian immigrants peaked between 1965 and 1972, boosted in particular by Ugandan dictator Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 16 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. He ruled as a military dictator and is considered one of the most brutal despots in modern w ...

's sudden decision to expel all 50,000 Gujarati

Gujarati may refer to:

* something of, from, or related to Gujarat, a state of India

* Gujarati people, the major ethnic group of Gujarat

* Gujarati language, the Indo-Aryan language spoken by them

* Gujarati languages, the Western Indo-Aryan sub ...

Indians from Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The sou ...

. Around 30,000 Ugandan Asians emigrated to the UK.

Following the independence of Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

, Pakistani immigration to the United Kingdom increased, especially during the 1950s and 1960s. Many Pakistanis came to Britain following the turmoil during the partition of India and the subsequent independence of Pakistan; among them were those who migrated to Pakistan upon displacement from India, and then emigrated to the UK, thus becoming secondary migrants. Migration was made easier as Pakistan was a member of the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the ...

. Pakistanis were invited by employers to fill labour shortages which arose after the Second World War. As Commonwealth citizens, they were eligible for most British civic rights. They found employment in the textile industries of Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancash ...

and Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

, manufacturing in the West Midlands

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

, and car production and food processing industries of Luton

Luton () is a town and unitary authority with borough status, in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 census, the Luton built-up area subdivision had a population of 211,228 and its built-up area, including the adjacent towns of Dunstable a ...

and Slough. It was common for Pakistani employees to work nightshifts and at other less-desirable hours.

In addition, there was a stream of migrants from East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Myanmar, wi ...

(now Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

). During the 1970s, a large number of East African-Asians, most of whom already held British passports because they had been British subjects settled in the overseas colonies, entered the United Kingdom from Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

...

and Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The sou ...

, particularly as a result of the expulsion of Asians from Uganda

In early August 1972, the President of Uganda, Idi Amin, ordered the expulsion of his country's Indian minority, giving them 90 days to leave the country. At the time of the expulsion, there were about 80,000 individuals of Indian descent in Ugand ...

by Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 16 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. He ruled as a military dictator and is considered one of the most brutal despots in modern w ...

in 1972.

There was also an influx of refugees from Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

, following the crushing of the 1956 Hungarian revolution

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hung ...

, numbering 20,990 people.

Until the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962

The Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act entailed stringent restrictions on the entry of Commonwealth citizens into the United Kingdom. Only those with work permits (which were typically on ...

, all Commonwealth citizens could enter and stay in the UK without any restriction. The Act made Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies

The term "British subject" has several different meanings depending on the time period. Before 1949, it referred to almost all subjects of the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Dominions, and colonies, but excluding protectorates ...

(CUKCs), whose passports were not directly issued by the UK Government (i.e., passports issued by the Governor of a colony or by the Commander of a British protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

), subject to immigration control.

Enoch Powell

John Enoch Powell, (16 June 1912 – 8 February 1998) was a British politician, classical scholar, author, linguist, soldier, philologist, and poet. He served as a Conservative Member of Parliament (1950–1974) and was Minister of Health (1 ...

gave the famous " Rivers of Blood" speech on 20 April 1968 in which he warned his audience of what he believed would be the consequences of continued unchecked immigration from the Commonwealth to Britain. Conservative Party leader Edward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George Heath (9 July 191617 July 2005), often known as Ted Heath, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1974 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1965 to 1975. Heath a ...

fired Powell from his Shadow Cabinet the day after the speech, and he never held another senior political post. Powell received 110,000 letters only 2,300 disapproving. Three days after the speech, on 23 April, as the Race Relations Bill was being debated in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, around 2,000 dockers walked off the job to march on Westminster protesting against Powell's dismissal, and the next day 400 meat porters from Smithfield market handed in a 92-page petition in support of Powell. At that time, 43% of junior doctors working in NHS hospitals, and some 30% of student nurses, were immigrants, without which the health service would needed to have been curtailed.

By 1972, only holders of work permits, or people with parents or grandparents born in the UK could gain entry – significantly reducing primary immigration from Commonwealth countries.

By 1972, only holders of work permits, or people with parents or grandparents born in the UK could gain entry – significantly reducing primary immigration from Commonwealth countries.

Immigration as influenced by the EU (1983–2022)

TheBritish Nationality Act 1981

The British Nationality Act 1981 (c.61) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom concerning British nationality since 1 January 1983.

History

In the mid-1970s the British Government decided to update the nationality code, which had b ...

, which was enacted in 1983, distinguishes between British citizens and British Overseas Territories citizens. It also made a distinction between nationality ''by descent'' and nationality ''other than by descent''. Citizens by descent cannot automatically pass on British nationality to a child born outside the United Kingdom or its Overseas Territories (though in some situations the child can be registered as a citizen).

Immigration officers have to be satisfied with a person's nationality and identity and entry can be refused if they are not satisfied.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

in Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

led to a large number of Somali immigrants, comprising the majority of the current Somali population in the UK. In the late-1980s, most of these early migrants were granted asylum, while those arriving later in the 1990s more often obtained temporary status. There has also been some secondary migration of Somalis to the UK from the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

. The main driving forces behind this secondary migration included a desire to reunite with family and friends and for better employment opportunities.

Non-European immigration rose significantly during the period from 1997, not least because of the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is ...

's abolition of the primary purpose rule in June 1997. This change made it easier for UK residents to bring foreign spouses into the country.

The former government adviser Andrew Neather in the ''Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after be ...

'' stated that the deliberate policy of ministers from late-2000 until early-2008 was to open up the UK to mass migration.

COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identi ...

falling disproportionately on foreign-born workers. Interviews conducted by Al Jazeera suggested that Brexit may have been a more significant push factor than the pandemic. Subsequent analysis of the impact of the pandemic on population statistics generated by the Labour Force Survey

Labour Force Surveys are statistical surveys conducted in a number of countries designed to capture data about the labour market. All European Union member states are required to conduct a Labour Force Survey annually. Labour Force Surveys are als ...

(LFS) suggests that "LFS-based estimates are likely to significantly overstate the change in the non-UK national population". Payroll data shows that the number of EU workers fell by 7 percent between October–December 2019 and October–December 2020.

Office for National Statistics migration estimates published in November 2021 suggest that the number of EU nationals leaving the UK exceeded the number arriving by around 94,000, compared to net inward migration from the EU to the UK of 32,000 in 2019. Some commentators suggested that these figures underestimate the extent of emigration of EU nationals from the UK.

Immigrants from the European Union

Four Freedoms

The Four Freedoms were goals articulated by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Monday, January 6, 1941. In an address known as the Four Freedoms speech (technically the 1941 State of the Union address), he proposed four fundamental freed ...

of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

, of which the United Kingdom is a former member, is the right to the free movement of workers as codified in the Directive 2004/38/EC

Directive may refer to:

* Directive (European Union), a legislative act of the European Union

* Directive (programming), a computer language construct that specifies how a compiler should process input

* "Directive" (poem), a poem by Robert Fro ...

and the EEA Regulations (UK).

With the expansion of the EU on 1 May 2004, the UK has accepted immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

, Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ge ...

, although the substantial Maltese and Greek-Cypriots and Turkish-Cypriot

Turkish Cypriots or Cypriot Turks ( tr, Kıbrıs Türkleri or ''Kıbrıslı Türkler''; el, Τουρκοκύπριοι, Tourkokýprioi) are ethnic Turks originating from Cyprus. Following the Ottoman conquest of the island in 1571, about 30,00 ...

communities were established earlier through their Commonwealth connection. There are restrictions on the benefits that members of eight of these accession countries ('A8' nationals) can claim, which are covered by the Worker Registration Scheme. Many other European Union member states exercised their right to temporary immigration control (which ended in 2011) over entrants from these accession states, but some subsequently removed these restrictions ahead of the 2011 deadline.

The United Kingdom uses statistics to predict migration that are produced primarily from the International Passenger Survey conducted by the Office for National Statistics

The Office for National Statistics (ONS; cy, Swyddfa Ystadegau Gwladol) is the executive office of the UK Statistics Authority, a non-ministerial department which reports directly to the UK Parliament.

Overview

The ONS is responsible for t ...

(ONS). The survey's primary mission is to help government's understand the effects of tourism and travel on their economy. Two parliamentary committees criticized the survey and found it to lack credibility. The actual net migration in 2015-16 from EU states to the United Kingdom, 29,000, was 16% higher than the ONS expected.

Research conducted by the Migration Policy Institute for the Equality and Human Rights Commission suggests that, between May 2004 and September 2009, 1.5 million workers migrated from the new EU member states to the UK, but that many have returned home, with the result that the number of nationals of the new member states in the UK increased by some 700,000 over the same period. Migration from Poland in particular has become temporary and circular in nature. In 2009, for the first time since the enlargement, more nationals of the eight Central and Eastern European states that joined the EU in 2004 left the UK than arrived. Research commissioned by the Regeneration and Economic Development Analysis Expert Panel suggested migrant workers leaving the UK due to the recession are likely to return in the future and cited evidence of "strong links between initial temporary migration and intended permanent migration".

The Government announced that the same rules would not apply to nationals of Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

(A2 nationals) when those countries acceded to the EU in 2007. Instead, restrictions were put in place to limit migration to students, the self-employed, highly skilled migrants and food and agricultural workers.

In February 2011, the Leader of the Labour Party, Ed Miliband

Edward Samuel "Ed" Miliband (born 24 December 1969) is a British politician serving as Shadow Secretary of State for Climate Change and Net Zero since 2021. He has been the Member of Parliament (MP) for Doncaster North since 2005. Miliban ...

, stated that he thought that the Labour government's decision to permit the unlimited immigration of eastern European migrants had been a mistake, arguing that they had underestimated the potential number of migrants and that the scale of migration had had a negative impact on wages.

A report by the Department for Communities and Local Government

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC), formerly the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG), is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for housing, communities, local governme ...

(DCLG) entitled ''International Migration and Rural Economies'', suggests that intra-EU migration since enlargement has resulted in migrants settling in rural locations without a prior history of immigration.

Research published by University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

in July 2009 found that, on average, A8 migrants were younger and better educated than the native population, and that if they had the same demographic characteristics of natives, would be 13 per cent less likely to claim benefits and 28 per cent less likely to live in social housing

Public housing is a form of housing tenure in which the property is usually owned by a government authority, either central or local. Although the common goal of public housing is to provide affordable housing, the details, terminology, d ...

.

Expulsions of criminals

Expulsions of immigrants who had committed crimes varied between 4,000 and 5,000 a year between 2007 and 2010.Controversy over application of section 322(5)

In May 2018 under the tenure ofSajid Javid

Sajid Javid (; born 5 December 1969) is a British politician who served as Secretary of State for Health and Social Care from June 2021 to July 2022, having previously served as Home Secretary from 2018 to 2019 and Chancellor of the Exchequer ...

, it was the view of a significant minority that the Home Office was misusing section 322(5) of the Immigration Rules. The section was designed to combat terrorism, but the Home Office had been wrongly applying it to hundreds of settled, highly skilled workers. The hardship faced by the workers was compared to the Windrush scandal, which occurred around the same time. By early 2019, approximately 90 people had been deported from the UK due to section 322(5).

In May 2021, the Director of Advocacy at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy

The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD) is a non-profit human rights organisation based in London which promotes democratisation and human rights in Bahrain. It was founded by Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, Alaa Shehabi and Hussain Abdullah ...

, Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei wrote an opinion piece for ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' highlighting how the Home Office under Priti Patel viewed “activists as a security threat”. The human rights activist

A human rights defender or human rights activist is a person who, individually or with others, acts to promote or protect human rights. They can be journalists, environmentalists, whistleblowers, trade unionists, lawyers, teachers, housing cam ...

was tortured and imprisoned in Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

for taking part in the country's Arab Spring

The Arab Spring ( ar, الربيع العربي) was a series of anti-government protests, uprisings and armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab world in the early 2010s. It began in Tunisia in response to corruption and econo ...

uprisings, following which he fled to the United Kingdom. In 2015, Bahrain “arbitrarily revoked” his citizenship. Before the birth of his daughter, Alwadaei submitted his application for indefinite leave to stay in the UK and to prevent his child from being born stateless. However, the Home Office delayed the approval of his application until 2019, and his daughter was born without any citizenship. Alwadaei said the Home Office was keeping a record of his years of activism, labeling his case as “complex”. His daughter was not granted the British citizenship she was entitled to by law, even after her parents forcefully paid £1,012 for her citizenship application. Alwadaei also pointed to the growing ties of Patel with conservation regime, Bahrain, stating that it is "deeply alarming”.

Immigration Rules and prior statutory instruments and controls on aliens

In 1914, Parliament enacted "panic legislation", The Alien Restrictions Act, 1914, during the onset of World War I to place limits on the entry into, and stay in, the UK of foreign nationals. The act provided for the introduction ofOrders in Council

An Order-in-Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council (''King ...

to detail the restrictions to be imposed on aliens. In 1919, after the conclusion of the war, that legislation was re-enacted, while the provisions that limited it to a time of war were removed. By the early 1950s, roughly 20 Orders in Council had been passed to flesh out the details for immigration control.

In 1952, Parliament moved to place its imprimatur on those orders by approving a consolidating order, The Aliens Order, 1953, that also removed some of the more objectionable provisions. However, other provisions of concern remained, including those potentially incompatible with other laws and international obligations of the UK.

The Immigration Act 1971, section 1, provided for "rules laid down by the Secretary of State as to the practice to be followed in the administration of this Act".

In 1972, the Heath administration

Edward Heath of the Conservative Party formed the Heath ministry and was appointed Prime Minister of the United Kingdom by Queen Elizabeth II on 19 June 1970, following the 18 June general election. Heath's ministry ended after the February ...

introduced the first proposed Immigration Rules under the 1971 act. The rules proposal drew criticism from Conservative Party backbenchers

In Westminster and other parliamentary systems, a backbencher is a member of parliament (MP) or a legislator who occupies no governmental office and is not a frontbench spokesperson in the Opposition, being instead simply a member of th ...

, because it formally implemented a limit of six months of leave to enter as a visitor for white "Old Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the ...

" citizens who were "non-patrial" (did not have Right of Abode

The right of abode is an individual's freedom from immigration control in a particular country. A person who has the right of abode in a country does not need permission from the government to enter the country and can live and work there withou ...

under the 1971 act, generally because they did not have a parent or grandparent from the UK). At the same time the proposal opened the door to free movement of certain European workers from European Economic Community member states. Seven backbenchers voted against the proposed Rules and 53 abstained, leading to defeat. Minutes from a Cabinet meeting the next day conclude that "anti-European sentiment" among backbenchers, who instead preferred "Old Commonwealth" migration to the UK, was at the core of the result. The proposal was revised, and the first Rules were passed in January 1973.

By August 2018, the Immigration Rules stood at almost 375,000 words, often so precise and detailed that the service of a lawyer are typically required to navigate them. That length represented nearly a doubling in just a decade. During the period of the introduction of the "hostile environment

Hostile Environment is the third solo album of rapper/emcee Rasco

Keida Brewer (born September 6, 1970), known professionally as Rasco (a bacronym for "Realistic, Ambitious, Serious, Cautious, and Organized"), is an American rapper.

Born i ...

" policy under Prime Minister Theresa May

Theresa Mary May, Lady May (; née Brasier; born 1 October 1956) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2016 to 2019. She previously served in David Cameron's cabi ...

, more than 1,300 changes were made to the Rules in 2012 alone. Former Lord Justice of Appeal Stephen Irwin referred to the complexity of the system as "something of a disgrace", and an effort to gradually overhaul the Rules into a more understandable system began to take place. The England and Wales Law Commission began to make recommendations for clearer rules to be adopted.

Managed migration

UK Visas and Immigration

UK Visas and Immigration (UKVI) is a division of the Home Office responsible for the United Kingdom's visa system. It was formed in 2013 from the section of the UK Border Agency that had administered the visa system.

History

The then Home Secre ...

, a department within the Home Office. Applications are made at UK embassies or consulates or directly to UK Visas and Immigration, depending upon the type of visa or permit required.

In April 2006, changes to the managed migration system were proposed that would create one points-based immigration system

A points-based immigration system is an immigration system where a noncitizen's eligibility to immigrate is (partly or wholly) determined by whether that noncitizen is able to score above a threshold number of points in a scoring system that might ...

for the UK in place of all other schemes. Tier 1 in the new system – which replaced the Highly Skilled Migrant Programme The Highly Skilled Migrant Programme (HSMP) was a scheme from 2002 until 2008, that was designed to allow highly skilled people to immigrate into the United Kingdom to look for work or self-employment opportunities. It was different from the standar ...

– gives points for age, education, earning, previous UK experience but not for work experience. The points-based system was phased in over the course of 2008, replacing previous managed migration schemes such as the work permit system and the Highly Skilled Migrant Programme.

A points-based system is composed of five tiers was first described by the UK Border Agency

The UK Border Agency (UKBA) was the border control agency of the Government of the United Kingdom and part of the Home Office that was superseded by UK Visas and Immigration, Border Force and Immigration Enforcement in April 2013. It was f ...

as follows:

*Tier 1 – for highly skilled individuals, who can contribute to growth and productivity;

*Tier 2 – for skilled workers with a job offer, to fill gaps in the United Kingdom workforce;

*Tier 3 – for limited numbers of low-skilled workers needed to fill temporary labour shortages;

*Tier 4 – for students;

*Tier 5 – for temporary workers and young people covered by the Youth Mobility Scheme, who are allowed to work in the United Kingdom for a limited time to satisfy primarily non-economic objectives.

The Migration Advisory Committee was established in 2007 to give policy advice.

In June 2010, The newly elected Coalition government brought in a temporary cap on immigration of those entering the UK from outside the EU, with the limit set as 24,100, in order to stop an expected rush of applications before a permanent cap was imposed in April 2011. The cap caused tension within the coalition, and then-Business Secretary Vince Cable

Sir John Vincent Cable (born 9 May 1943) is a British politician who was Leader of the Liberal Democrats from 2017 to 2019. He was Member of Parliament (MP) for Twickenham from 1997 to 2015 and from 2017 to 2019. He also served in the Cabinet as ...

argued that it was harming British businesses. Others have argued that the cap would have a negative impact on Britain's status as a centre for scientific research.

For family relatives of European Economic Area

The European Economic Area (EEA) was established via the ''Agreement on the European Economic Area'', an international agreement which enables the extension of the European Union's single market to member states of the European Free Trade As ...

nationals living in the UK, there is the EEA family permit

A European Economic Area Family Permit (short: EEA family permit) was an immigration document that assisted the holder to enter the United Kingdom as a family member of a citizen of a contracting state to the European Economic Area agreement or ...

which enables those family members to join their relatives already living and working in the UK.

Though immigration is a matter that is reserved to the UK Government under the legislation

Legislation is the process or result of enrolling, enacting, or promulgating laws by a legislature, parliament, or analogous governing body. Before an item of legislation becomes law it may be known as a bill, and may be broadly referred to ...

that established devolution for Scotland in 1999, the Scottish Government was able to get an agreement from the Home Office for their Fresh Talent Initiative which was designed to encourage foreign graduates of Scottish universities

There are fifteen universities in Scotland and three other institutions of higher education that have the authority to award academic degrees.

The first university college in Scotland was founded at St John's College, St Andrews in 1418 by H ...

to stay in Scotland to look for employment. The Fresh Talent Initiative ended in 2008, following the introduction of points-based system.

Refugees and asylum seekers

The UK is a signatory to the UN

The UK is a signatory to the UN 1951 Refugee Convention

The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, also known as the 1951 Refugee Convention or the Geneva Convention of 28 July 1951, is a United Nations multilateral treaty that defines who a refugee is, and sets out the rights of individuals ...

as well as the 1967 Protocol and has therefore a responsibility to offer protection to people who seek asylum it and fall into the legal definition of a " refugee", and moreover not to return (or refoule) any displaced person to places where they would otherwise face persecution. Cuts to legal aid prevent asylum seekers getting good advice or arguing their case effectively. This can mean refugees being returned to a country where they face certain death.

The issue of immigration has been a controversial political issue since the late 1990s. Both the Labour Party and the Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

have suggested policies perceived as being "tough on asylum" (although the Conservatives have dropped a previous pledge to limit the number of people who could claim asylum in the UK, which would likely have breached the UN Refugee Convention) and the tabloid media frequently print headlines about an "immigration crisis".Roy GreensladSeeking scapegoats: The coverage of asylum in the UK press (PDF)

, Institute for Public Policy Research, May 2005 This is denounced, by those seeking to ensure that the UK upholds its international obligations, as disproportionate. Concern is also raised about the treatment of those held in detention and the practice of

dawn raid

A police raid is an unexpected visit by police or other law enforcement officers, law-enforcement officers with the aim of using the element of surprise in order to seize evidence or arrest suspects believed to be likely to hide evidence, res ...

ing families, and holding young children in immigration detention

Immigration detention is the policy of holding individuals suspected of visa violations, illegal entry or unauthorized arrival, as well as those subject to deportation and removal until a decision is made by immigration authorities to grant a v ...

centres for long periods of time. The policy of detaining asylum-seeking children was to be abandoned as part of the coalition agreement

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats, who formed a government in May 2010. However, in July 2010 the government was accused of back-tracking on this promise after the Immigration Minister Damian Green

Damian Howard Green (born 17 January 1956) is a British politician who served as First Secretary of State and Minister for the Cabinet Office from June to December 2017 in the Second May government. A member of the Conservative Party, he has b ...

announced that the plan was to minimise, rather than end, child detention.

However, critics of the UK's asylum policy often point out the "safe third country Safe third country is a country that is neither the home country of an asylum seeker

An asylum seeker is a person who leaves their country of residence, enters another country and applies for asylum (i.e., international protection) in that o ...

rule" – the convention that asylum seekers must apply in the first free nation they reach, not go "asylum shopping

Asylum shopping is a pejorative term for the practice by some asylum seekers of applying for asylum in several states or seeking to apply in a particular state after traveling through other states. The phrase is derogatory, suggesting that asylum s ...

" for the nation they prefer. EU courts have upheld this policy. Research conducted by the Refugee Council

The Refugee Council is a UK based organisation which works with refugees and asylum seekers. The organisation provides support and advice to refugees and asylum seekers, as well as support for other refugee and asylum seeker organisations. The R ...

suggests that most asylum seekers in the UK had their destination chosen for them by external parties or agents, rather than choosing the UK themselves.

In February 2003, Prime Minister Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

promised on television to reduce the number of asylum seekers by half within 7 months, apparently catching unawares the members of his own government with responsibility for immigration policy. David Blunkett

David Blunkett, Baron Blunkett, (born 6 June 1947) is a British Labour Party politician who has been a Member of the House of Lords since 2015, and previously served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Sheffield Brightside and Hillsborough ...

, then the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

, called the promise an ''objective'' rather than a ''target''.

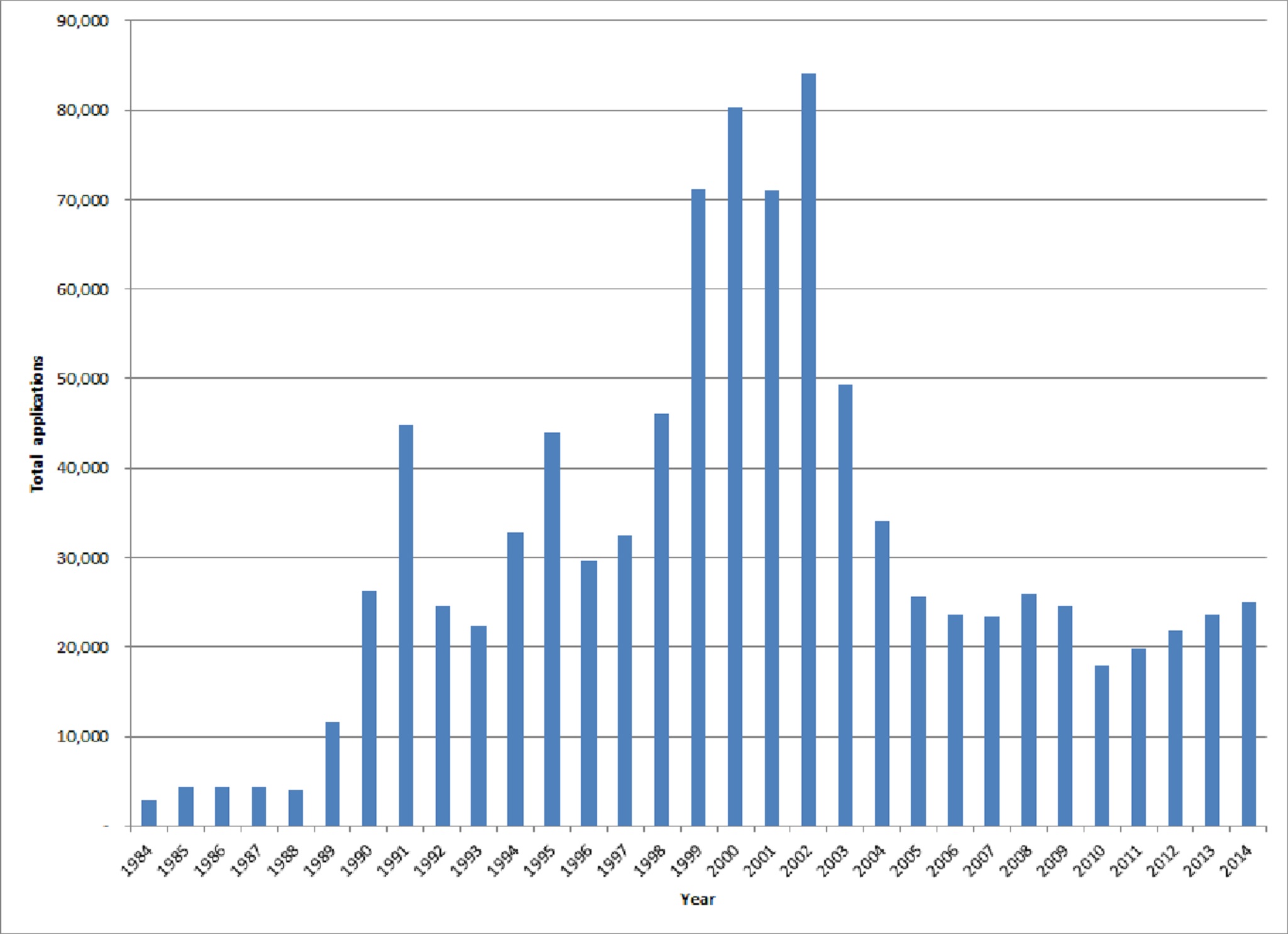

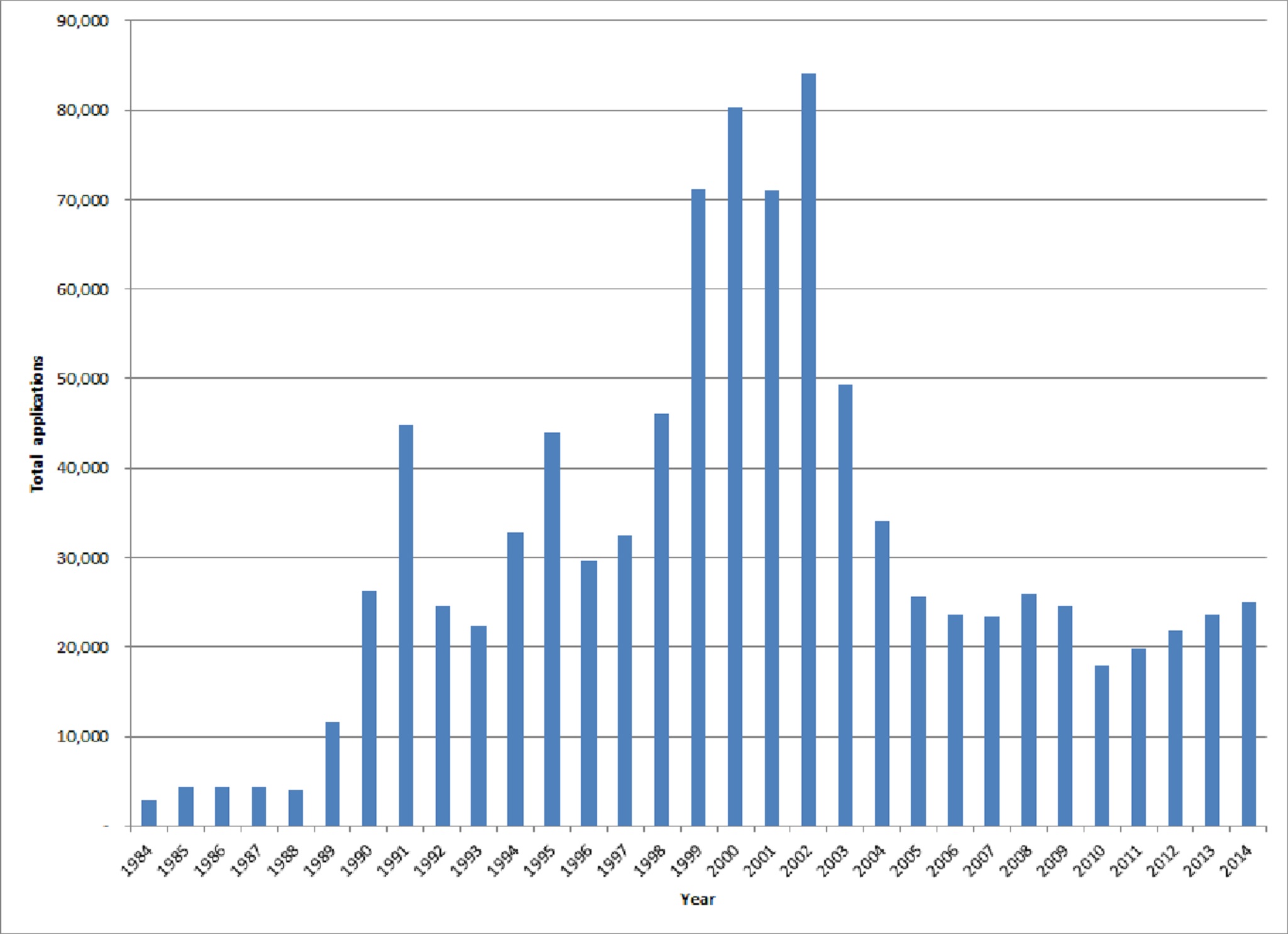

It was met according to official figures. There is also a Public Performance Target to remove more asylum seekers who have been judged not to be refugees under the international definition than new anticipated unfounded applications. This target was met early in 2006. Official figures for numbers of people claiming asylum in the UK were at a 13-year low by March 2006.

Human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

organisations such as Amnesty International have argued that the government's new policies, particularly those concerning detention centres, have detrimental effects on asylum applicants and their children, and those facilities have seen a number of hunger strikes

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

and suicides. Others have argued that recent government policies aimed at reducing 'bogus' asylum claims have had detrimental impacts on those genuinely in need of protection.

The UK hosts one of the largest populations of Iraqi refugees outside the Gulf region. About 65-70% of people originating from Iraq are Kurdish, and 70% of those from Turkey and 15% of those from Iran are Kurds.

Asylum seekers have been kept in detention after the courts ordered their release because the Home Office maintains detention is not dissimilar to emergency accommodation. Immigrants with the right to stay in the UK are denied housing and cannot be released. In other cases vulnerable asylum seekers are released onto the streets with nowhere to live. In January 2018 the government repealed a law that previously allowed homeless detainees to apply for housing while in detention if they had nowhere to live when released. Charities maintain around 2,000 detainees who before this applied for support each year can no longer do so.

On 9 August 2020, the reports suggested that the number of people who reached the United Kingdom shores in small boats, during that year, surpassed 4,000. The undocumented migrant crossings of the English Channel mounted tensions between the UK and France.

On 17 August 2021, the United Kingdom Government launched a new resettlement programme which aims to settle 20,000 Afghan refugees fleeing the 2021 Taliban offensive

A military offensive by the Taliban insurgent group and other allied militants led to the fall of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan based in Kabul and marked the end of the nearly 20-year-old War in Afghanistan, that had begun following the ...

over a five–year period in the UK. The UK also operates the UK Resettlement Scheme, Community Sponsorship Scheme and Mandate Resettlement Scheme. Previous UK resettlement schemes included the Gateway Protection Programme

The Gateway Protection Programme was a refugee resettlement scheme operated by the Government of the United Kingdom in partnership with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and co-funded by the European Union (EU), offering ...

and the Syrian Vulnerable Person Resettlement Programme

The Syrian Vulnerable Person Resettlement Programme, sometimes referred to as a Relocation Scheme, is a programme of the United Kingdom government that plans to resettle 20 000 Syrian refugees from refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, ...

.

Illegal immigration

Illegal immigrants in the UK include those who have:

* entered the UK without authority

* entered with false documents

* overstayed their visas

Although it is difficult to know how many people reside in the UK illegally, a Home Office study released in March 2005 estimated a population of between 310,000 and 570,000.

A recent study into irregular immigration states that "most irregular migrants have committed administrative offences rather than a serious crime".

Illegal immigrants in the UK include those who have:

* entered the UK without authority

* entered with false documents

* overstayed their visas

Although it is difficult to know how many people reside in the UK illegally, a Home Office study released in March 2005 estimated a population of between 310,000 and 570,000.

A recent study into irregular immigration states that "most irregular migrants have committed administrative offences rather than a serious crime".

Jack Dromey

John Eugene Joseph Dromey (29 September 1948 – 7 January 2022) was a British politician and trade unionist who served as Member of Parliament (MP) for Birmingham Erdington from 2010 until his death. A member of the Labour Party, he was depu ...

, Deputy General of the Transport and General Workers Union

The Transport and General Workers' Union (TGWU or T&G) was one of the largest general trade unions in the United Kingdom and Ireland – where it was known as the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers' Union (ATGWU) to differentiate its ...

and Labour Party treasurer, suggested in May 2006 that there could be around 500,000 illegal workers. He called for a public debate on whether an amnesty should be considered. David Blunkett

David Blunkett, Baron Blunkett, (born 6 June 1947) is a British Labour Party politician who has been a Member of the House of Lords since 2015, and previously served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Sheffield Brightside and Hillsborough ...

has suggested that this might be done once the identity card

An identity document (also called ID or colloquially as papers) is any document that may be used to prove a person's identity. If issued in a small, standard credit card size form, it is usually called an identity card (IC, ID card, citizen ca ...

scheme is rolled out.

London Citizens, a coalition of community organisations, is running a regularisation campaign called ''Strangers into Citizens'', backed by figures including the former leader of the Catholic Church in England and Wales, the Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O'Connor. Analysis by the Institute for Public Policy Research suggested that an amnesty could net the government up to £1.038 billion per year in fiscal revenue, however the long term implications of such a measure are uncertain.

It has since been suggested that to deport all of the illegal immigrants from the UK might take 20 years and cost up to £12 billion. Former Mayor of London Boris Johnson commissioned a study into a possible amnesty for illegal immigrants, citing larger tax gains within the London area which is considered to be home to the majority of the country's population of such immigrants.

In February 2008, the government introduced new £10,000 fines for employers found to be employing illegal immigrants where there is negligence on the part of the employer, with unlimited fines or jail sentences for employers acting knowingly.

Women who are illegal immigrants and also domestic violence victims risk deportation and are deported if they complain about violence. Women get brought illegally into the UK by men intending to abuse them. Women are sometimes deterred from complaining about violence to them due to the risk of deportation, therefore perpetrators including rapists remain at large. Martha Spurrier of Liberty (advocacy group), Liberty said, "It will leave people afraid to report crime, robbing them of protection under the law and creating impunity for criminals who target vulnerable people with unsettled immigration status. This is criminalising victims and letting criminals off the hook."

Comparison of European Union countries

According to Eurostat, 47.3 million people lived in theEuropean Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

in 2010 who were born outside their resident country. This corresponds to 9.4% of the total EU population. Of these, 31.4 million (63%) were born outside the EU and 16.0 million (32%) were born in another EU member state. The largest absolute numbers of people born outside the EU were in Germany (6.4 million), France (5.1 million), the United Kingdom (4.7 million), Spain (4.1 million), Italy (3.2 million), and the Netherlands (1.4 million).

Citizenship laws

Individuals wanting to apply for British nationality law, British citizenship have to demonstrate their commitment by learning English language, Welsh language or Gaelic language and by having an understanding of History of the British Isles, British history, culture and traditions. Any individual seeking to apply for naturalisation or indefinite leave to remain must pass the official Life in the United Kingdom test, Life in the UK test.Brexit

See also

*British diaspora *British nationality law