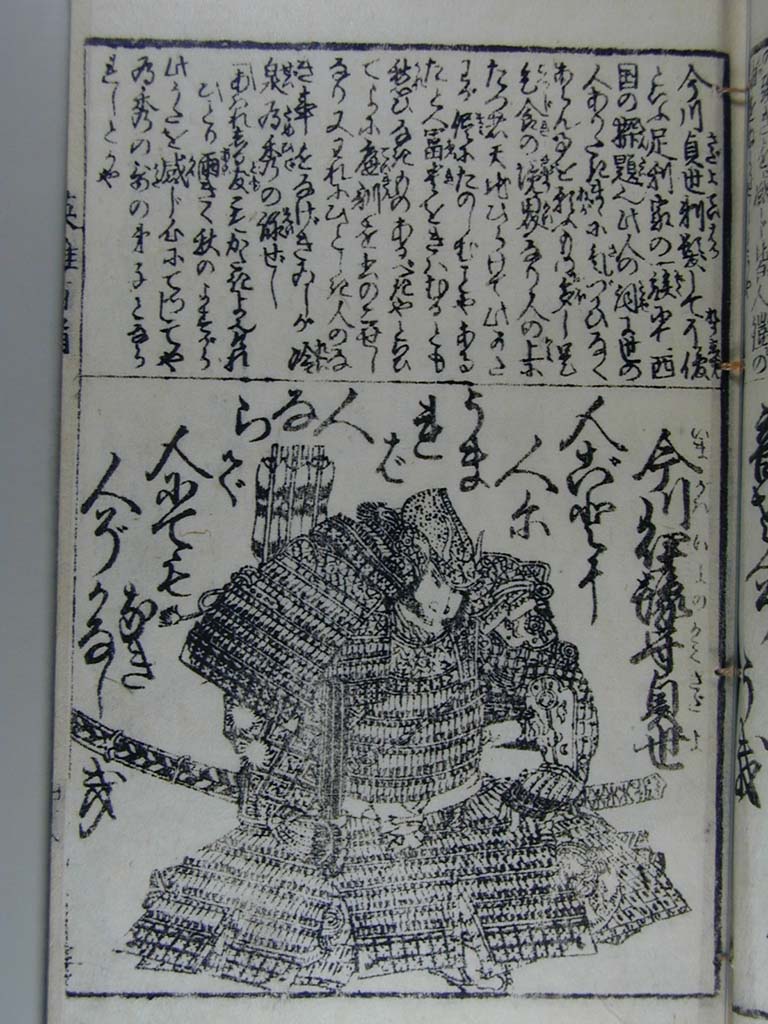

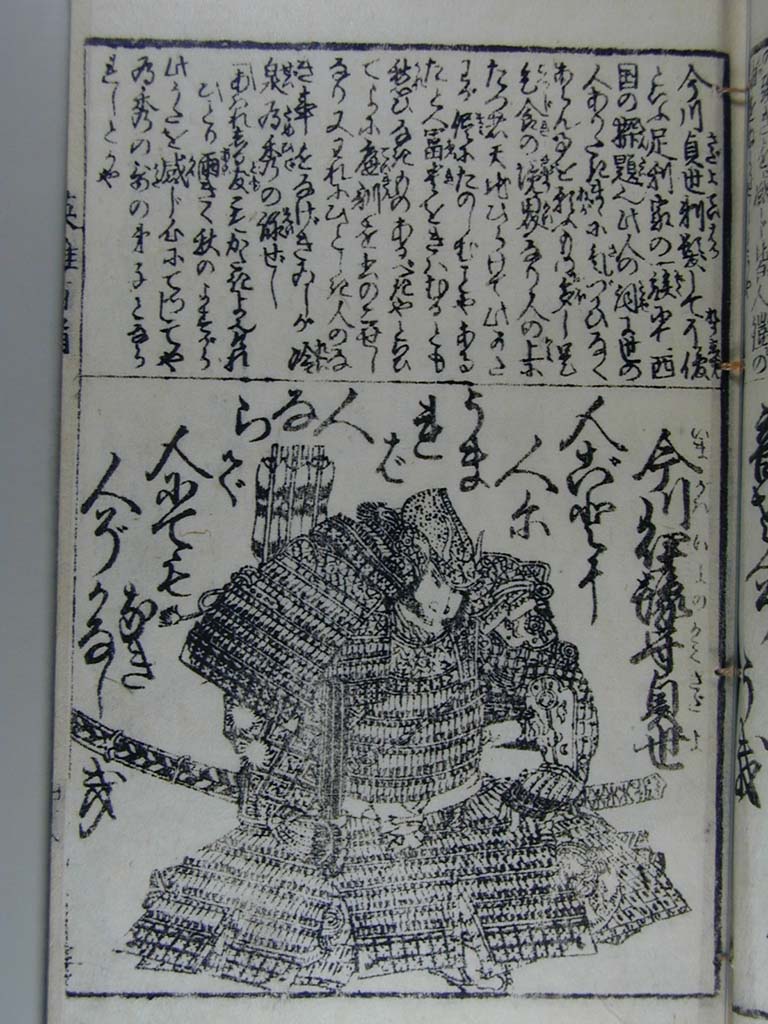

Imagawa Ryoshun on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, also known as , was a renowned Japanese poet and military commander who served as tandai ("constable") of

, also known as , was a renowned Japanese poet and military commander who served as tandai ("constable") of

From Feudal Chieftain to Secular Monarch. The Development of Shogunal Power in Early Muromachi Japan

, by Kenneth A. Grossberg. '' Monumenta Nipponica'', Vol. 31, No. 1. (Spring, 1976), pp. 29–49

"The Imagawa Letter: A Muromachi Warrior's Code of Conduct Which Became a Tokugawa Schoolbook"

by Carl Steenstrup. ''Monumenta Nipponica'', Vol. 28, No. 3. (Autumn, 1973), pp. 295–316. {{DEFAULTSORT:Imagawa, Sadayo 1326 births 1420 deaths Daimyo Imagawa clan Bushido 14th-century Japanese poets 15th-century Japanese poets

, also known as , was a renowned Japanese poet and military commander who served as tandai ("constable") of

, also known as , was a renowned Japanese poet and military commander who served as tandai ("constable") of Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's five main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands ( i.e. excluding Okinawa). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regional name referred to Kyushu and its surround ...

under the Ashikaga bakufu from 1371 to 1395. His father, Imagawa Norikuni

was a Japanese samurai clan that claimed descent from the Seiwa Genji by way of the Kawachi Genji. It was a branch of the Minamoto clan by the Ashikaga clan.

Origins

Ashikaga Kuniuji, grandson of Ashikaga Yoshiuji, established himself ...

, had been a supporter of the first Ashikaga '' shōgun'', Ashikaga Takauji, and for his services had been granted the position of constable of Suruga Province

was an old province in the area that is today the central part of Shizuoka Prefecture. Suruga bordered on Izu, Kai, Sagami, Shinano, and Tōtōmi provinces; and was bordered by the Pacific Ocean through Suruga Bay to the south. Its abbrevia ...

(modern-day Shizuoka Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located in the Chūbu region of Honshu. Shizuoka Prefecture has a population of 3,637,998 and has a geographic area of . Shizuoka Prefecture borders Kanagawa Prefecture to the east, Yamanashi Prefecture to the northea ...

). This promotion increased the prestige of the Imagawa family (a warrior family dating from the Muromachi period, which was related by blood to the Ashikaga shoguns) considerably, and they remained an important family through to the Edo period.

Sadayo's early life

During his early years Sadayo was taught Buddhism, Confucianism and Chinese,archery

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a bow to shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting and combat. In m ...

, and the military arts such as strategy

Strategy (from Greek στρατηγία ''stratēgia'', "art of troop leader; office of general, command, generalship") is a general plan to achieve one or more long-term or overall goals under conditions of uncertainty. In the sense of the "art ...

and horse-back riding

Equestrianism (from Latin , , , 'horseman', 'horse'), commonly known as horse riding (Commonwealth English) or horseback riding (American English), includes the disciplines of riding, driving, and vaulting. This broad description includes the ...

by his father (governor of the Tōkaidō provinces Tōtōmi and Suruga), along with poetry, which was to become one of his greatest passions. In his twenties he studied under Tamemoto of the Kyogoku school of poetry, and Reizei Tamehide of the Reizei school. At some point, he was appointed to head the boards of retainers and coadjudicators. He had taken religious vows when the Ashikaga bakufu called upon him to travel to Kyūshū and assume the post of constable of the region in 1370 after the failure of the previous constable to quell the rebel uprisings in the region, largely consisting of partisans of the Souther Court supporting one of the rebellious Emperor Go-Daigo's sons, Prince Kanenaga. By 1374–1375, Sadayo had crushed the rebellion, securing for the Bakufu northern Kyūshū, and ensuring the eventual failure of the rebellion and the consequent success of the Bakufu Shogunate.

Kyūshū Tandai (1371–1395)

Sadayo's skill as a strategist was obvious, and he moved rapidly through northern Kyūshū with a great deal of success, bringing the region under his control by October 1372. This was an impressive achievement considering Prince Kanenaga had been fortifying his position in this region for more than a decade. Kanenaga was not defeated outright however, and went on the defensive, leading to a stalemate that lasted through to 1373, when Kanenaga's general, Kikuchi Takemitsu, died, leaving his military with no strong leader. Sadayo seized the opportunity and planned a final attack. Sadayo met with three of the most powerful families on Kyūshū to gain their support in the attack, those families being the Shimazu, the Ōtomo and the Shōni. Things seemed to be going well until Sadayo suspected the head of the Shoni family of treachery and had him killed at a drinking party. This outraged the Shimazu clan, who had originally been the ones to convince the Shōni to throw their lot in with Sadayo, and they returned to their province of Satsuma to raise a force against Sadayo. This gave Prince Kanenaga time to regroup, and he forced Sadayo back North, prompting Sadayo to request assistance from the Bakufu. Sadayo took matters into his own hands, but was aided by his son Yoshinori and his younger brother Tadaaki. Sadayo continued to push the loyalists forces until their resistance ended with Prince Kanenaga's death in 1383. The death of Shimazu clan chieftain Ujihasa in 1385 also helped ease tensions between Sadayo and the Shimazu for a time. In 1377, Korean diplomat Jeong Mong-ju arrived in Japan with complaints about the raids of '' wokou'' - Japanese pirates striking from bases on Kyūshū and other southern isles of Japan. Sadayo defeated many of the pirate bands and returned captured civilians and property to Korea.Kawazoe, Shōji, ''Taigai kankei no shiteki tenkai'' (Bunken shuppan, 1996) p. 167 (川添昭二「対外関係の史的展開」) . In 1395 both the Ōuchi and Ōtomo families conspired against Sadayo, informing the Bakufu that he was plotting against the ''shōgun'', in a move that was likely an attempt to restore the post of constable to the family that had held it prior to Sadayo, the Shibukawa family. Sadayo was relieved of his post and returned to the capital. Sadayo had, in addition, acted fairly independently in his negotiations with the Shimazu, the Ōtomo and the Shōni, and also in negotiations with Korea about the wokou; this recall was prompted by all three causes being used against him by his enemies in the Shogun's court.Later years (1395–1420)

In 1400 Sadayo was once again questioned by the Bakufu, this time in relation to the Imagawa's province of Tōtōmi's failure to respond to a levy issued by the Bakufu—a negligence interpretable as treason and rebellion. This charge saw Sadayo stripped of his post as constable of Suruga and Tōtōmi provinces, and gave him reason to believe he might be assassinated. With this in mind he fled the capital for a time, though was later pardoned and returned to the capital, spending the rest of his days pursuing religious devotions and poetry until his death in 1420.Sadayo's poetry

Sadayo began composing poetry from an early age: by the age 20, he had a poem included in an imperial anthology (the '' Fūga Wakashū'' or "Collection of Elegance"; Earl Miner gives the specific entry as XV: 1473). His teacher was Reizei no Tamehide (d. 1372). His poems were displayed to more effect in his fairly popular and influential travel diary, ''Michiyukiburi'' ("Travellings"). It was this travel diary that in large part won Sadayo a place as a respected critic of poetry: he felt that poetry should be a direct expression of personal experience, a fact that can be seen from his own poems. Even though Sadayo is better known for his criticism of the more conservative poetry styles, the Nijo school in particular, and his tutoring of Shōtetsu (1381–1459), who would become one of the finest waka poets of the fifteenth century, than he is for his own output, it nonetheless provides a glimpse into the mind of this medieval scholar and his travels. Sadayo was active in the poetic disputes of that day, scoring a signal victory over the Nijō adherents close to the Ashikaga Shogunate at the time with 6 polemical treatises on poetry he wrote between 1403 and 1412, defending the Reizei's poetic doctrine and their cause (despite Ryōshun's renga poetry's debt to Nijō Yoshimoto's (1320–1388) examples and rules of composition). Ryōshun used a number of quotations to bolster his case, including notably a quote of Fujiwara no Teika's, which was that all of the "ten styles" (Teika had defined ten orthodox poetic styles, such as ''yoen'', a style concerned with "ethereal beauty", ''yūgen

Japanese aesthetics comprise a set of ancient ideals that include '' wabi'' (transient and stark beauty), '' sabi'' (the beauty of natural patina and aging), and '' yūgen'' (profound grace and subtlety). These ideals, and others, underpin much o ...

'', the demon-quelling style, or the one the Nijo championed to the exclusion of the other 9, ''ushin'') were licit for poetic use and experimentation, and not merely the Nijō's ''ushin''. With the aid Ryōshun afforded him, Fujiwara no Tanemasa's politicking eventually succeeded in converting the Shogun, ending the matter- until the rival Asukai poetic clan revived the dispute, that is.

Select poems

References

Notes

Further reading

*''Waiting for the Wind: Thirty-Six Poets of Japan's Late Medieval Age'', translated by Steven D. Carter, Columbia University Press, 1989. *''The Imagawa Letter: A Muromachi Warrior's Code of Conduct Which Became a Tokugawa Schoolbook'', translated byCarl Steenstrup

Carl Steenstrup (1934 – 11 November 2014)) was a Danish japanologist.

Carl Steenstrup is known for translating several works of Japanese literature, mostly those relating to the historical development of Bushido, Japanese Feudal Law, and th ...

in Monumenta Nipponica 28:3, 1973.

*''Unforgotten dreams: poems by the Zen monk Shōtetsu'', 1997. Steven D. Carter, Columbia University Press.

*''An Introduction to Japanese Court Poetry'', by Earl Miner. 1968, Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

Press, LC 68-17138

** pg. 138; Miner references his translation's source as "''Michiyukiburi'', GSRJ, XVIII, 560", where ''Michiyukiburi'' is Sadayo's travel diary, and GSRJ refers to the 30 volumes of the ''Gunsho Ruijū'' published in Tokyo between 1928 and 1934.

*From Feudal Chieftain to Secular Monarch. The Development of Shogunal Power in Early Muromachi Japan

, by Kenneth A. Grossberg. '' Monumenta Nipponica'', Vol. 31, No. 1. (Spring, 1976), pp. 29–49

"The Imagawa Letter: A Muromachi Warrior's Code of Conduct Which Became a Tokugawa Schoolbook"

by Carl Steenstrup. ''Monumenta Nipponica'', Vol. 28, No. 3. (Autumn, 1973), pp. 295–316. {{DEFAULTSORT:Imagawa, Sadayo 1326 births 1420 deaths Daimyo Imagawa clan Bushido 14th-century Japanese poets 15th-century Japanese poets