Ida Minerva Tarbell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ida Minerva Tarbell (November 5, 1857January 6, 1944) was an American writer,

Ida Tarbell's early life in the oil fields of Pennsylvania would have an impact when she later wrote on the Standard Oil Company and on labor practices. The

Ida Tarbell's early life in the oil fields of Pennsylvania would have an impact when she later wrote on the Standard Oil Company and on labor practices. The  Ida Tarbell was intelligent—but also undisciplined in the classroom. According to reports by Tarbell herself, she paid little attention in class and was often truant until one teacher set her straight: "She told me the plain and ugly truth about myself that day, and as I sat there, looking her straight in the face, too proud to show any feeling, but shamed as I never had been before and never have been since." Tarbell was especially interested in the sciences, and she began comparing the landscape around her in Pennsylvania to what she was learning in school. "Here I was suddenly on a ground which meant something to me. From childhood, plants, insects, stones were what I saw when I went abroad, what I brought home to press, to put into bottles, to litter up the house... I had never realized that they were subjects for study... School suddenly became exciting."

Tarbell graduated at the head of her high school class in Titusville and went on to study biology at

Ida Tarbell was intelligent—but also undisciplined in the classroom. According to reports by Tarbell herself, she paid little attention in class and was often truant until one teacher set her straight: "She told me the plain and ugly truth about myself that day, and as I sat there, looking her straight in the face, too proud to show any feeling, but shamed as I never had been before and never have been since." Tarbell was especially interested in the sciences, and she began comparing the landscape around her in Pennsylvania to what she was learning in school. "Here I was suddenly on a ground which meant something to me. From childhood, plants, insects, stones were what I saw when I went abroad, what I brought home to press, to put into bottles, to litter up the house... I had never realized that they were subjects for study... School suddenly became exciting."

Tarbell graduated at the head of her high school class in Titusville and went on to study biology at

sophomore stone

on campus dedicated to learning and with the Latin phrase, ''Spes sibi quisque'', which translates to "Everyone is his/her own hope". She was a member of the campus women's literary society, the Ossoli Society, named after writer Margaret Fuller Ossoli, and wrote for the society's publication, ''the Mosaic''. Tarbell graduated in 1880 with an A.B. degree and an M.A. degree in 1883. Tarbell later supported the university by serving on the board of trustees, to which she was first elected in 1912. She was the second woman to serve as a trustee and held the post for more than three decades.

Tarbell left school wanting to contribute to society but unsure of how to do it, she became a teacher. Tarbell began her career as headmistress at Poland Union Seminary in

Tarbell left school wanting to contribute to society but unsure of how to do it, she became a teacher. Tarbell began her career as headmistress at Poland Union Seminary in

Tarbell set about making her career as a writer in Paris. She supported herself by writing for several American newspapers including the ''

Tarbell set about making her career as a writer in Paris. She supported herself by writing for several American newspapers including the ''

The first book-length investigation of Standard Oil had appeared in 1894 by newspaperman

The first book-length investigation of Standard Oil had appeared in 1894 by newspaperman

Steve Weinberg wrote that Ida Tarbell was "a feminist by example, but not by ideology". Feminist scholars viewed Tarbell as an enigma as she seemed to both embrace the movement and act as a critic. While her accomplishments were many, Tarbell also challenged and questioned the logic of women's suffrage. Early in life, Tarbell was exposed to the suffragette movement when her mother hosted meetings in their home. Tarbell was put off by women such as

Steve Weinberg wrote that Ida Tarbell was "a feminist by example, but not by ideology". Feminist scholars viewed Tarbell as an enigma as she seemed to both embrace the movement and act as a critic. While her accomplishments were many, Tarbell also challenged and questioned the logic of women's suffrage. Early in life, Tarbell was exposed to the suffragette movement when her mother hosted meetings in their home. Tarbell was put off by women such as

A Short Life of Napoleon Bonaparte.

' New York:

Madame Roland: a biographical study.

' New York:

The Life of Abraham Lincoln. 2 vols.

' New York: McClure Phillips, 1900. *'' A Life of Napoleon Bonaparte: with a sketch of Josephine, Empress of the French'' New York:

He Knew Lincoln.

' New York: Doubleday Page, 1907. *'' Father Abraham'' New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1909. *'' The Tariff in Our Times.'' New York:

Citizen Reporters: S.S. McClure, Ida Tarbell, and the Magazine that Rewrote America

'. New York: Ecco/HarperCollins, 2020. * Kochersberger Jr., Robert C., ed. ''More Than a Muckraker: Ida Minerva Tarbell's Lifetime in Journalism'', The University of Tennessee Press, 1995 - collection of articles * McCully, Emily Arnold. Ida M. Tarbell The Woman Who Challenged Big Business and Won. New York: Clarion Books, 2014. * Randolph, Josephine D. "A Notable Pennsylvanian: Ida Minerva Tarbell, 1857–1944," ''Pennsylvania History'' (1999) 66#2 pp 215–241, short scholarly biography * Serrin, Judith and William. ''Muckraking! The Journalism that Changed America'', New York: The New York Press, 2002. * Somervill, Barbara A. ''Ida Tarbell: Pioneer Investigative Reporter'' Greensboro, nc : M. Reynolds., 2002 * Weinberg, Steve. ''Taking on the Trust: The Epic Battle of Ida Tarbell and John D. Rockefeller'' (2008) * Yergin, Daneil. '' The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power'' (2008)

Works by Ida Tarbell

a

Open LibraryThe Ida Tarbell Home PageThe Ida Tarbell Papers

at the

investigative journalist

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, such as serious crimes, political corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. An investigative journalist may spend months or years rese ...

, biographer

Biographers are authors who write an account of another person's life, while autobiographers are authors who write their own biography.

Biographers

Countries of working life: Ab=Arabia, AG=Ancient Greece, Al=Australia, Am=Armenian, AR=Ancient Rome ...

and lecturer. She was one of the leading muckraker

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists, writers, and photographers in the Progressive Era in the United States (1890s–1920s) who claimed to expose corruption and wrongdoing in established institutions, often through sensationalist publ ...

s of the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and pioneered investigative journalism

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, such as serious crimes, political corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. An investigative journalist may spend months or years rese ...

.

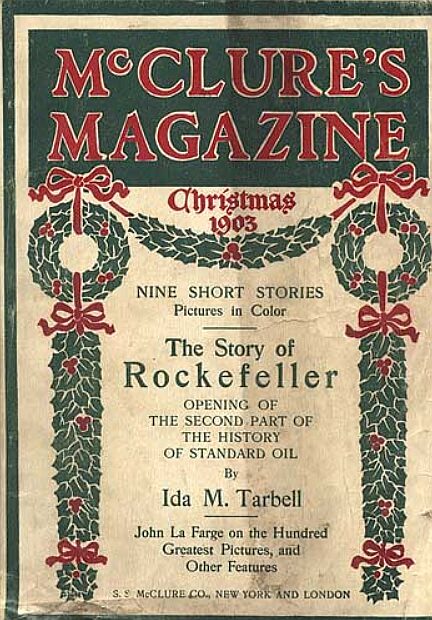

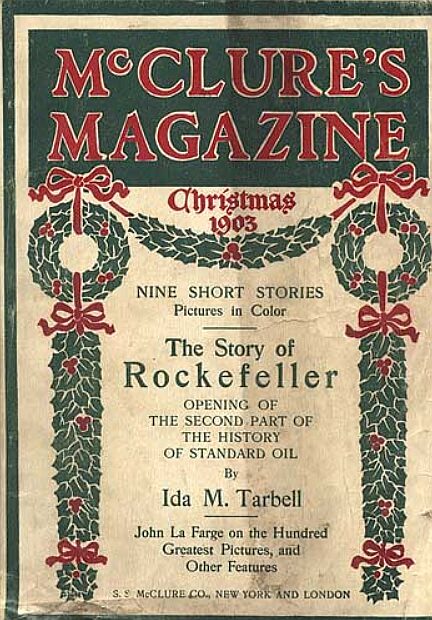

Born in Pennsylvania at the beginning of the oil boom, Tarbell is best known for her 1904 book ''The History of the Standard Oil Company

''The History of the Standard Oil Company'' is a 1904 book by journalist Ida Tarbell. It is an exposé about the Standard Oil Company, run at the time by oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller, the richest figure in American history. Originally serializ ...

.'' The book was published as a series of articles in ''McClure's Magazine

''McClure's'' or ''McClure's Magazine'' (1893–1929) was an American illustrated monthly periodical popular at the turn of the 20th century. The magazine is credited with having started the tradition of muckraking journalism ( investigative, wat ...

'' from 1902 to 1904. It has been called a "masterpiece of investigative journalism", by historian J. North Conway, as well as "the single most influential book on business ever published in the United States" by historian Daniel Yergin

Daniel Howard Yergin (born February 6, 1947) is an American author, speaker, energy expert, and economic historian. Yergin is vice chairman of S&P Global. He was formerly vice chairman of IHS Markit, which merged with S&P in 2022. He founded Ca ...

. The work contributed to the dissolution of the Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

monopoly and helped usher in the Hepburn Act

The Hepburn Act is a 1906 United States federal law that expanded the jurisdiction of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) and gave it the power to set maximum railroad rates. This led to the discontinuation of free passes to loyal shippers. ...

of 1906, the Mann-Elkins Act, the creation of the Federal Trade Commission

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is an independent agency of the United States government whose principal mission is the enforcement of civil (non-criminal) antitrust law and the promotion of consumer protection. The FTC shares jurisdiction ov ...

(FTC), and passage of the Clayton Antitrust Act

The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 (, codified at , ), is a part of United States antitrust law with the goal of adding further substance to the U.S. antitrust law regime; the Clayton Act seeks to prevent anticompetitive practices in their incipie ...

.

Tarbell also wrote several biographies over the course of her 64-year career. She wrote biographies on Madame Roland

Marie-Jeanne 'Manon' Roland de la Platière (Paris, March 17, 1754 – Paris, November 8, 1793), born Marie-Jeanne Phlipon, and best known under the name Madame Roland, was a French revolutionary, salonnière and writer.

Initially she led a ...

and Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

. Tarbell believed that "the Truth and motivations of powerful human beings could be discovered." That Truth, she became convinced, could be conveyed in such a way as "to precipitate meaningful social change." She wrote numerous books and works on Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, including ones that focused on his early life and career. After her exposé on Standard Oil and character study of John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He has been widely considered the wealthiest American of all time and the richest person in modern history. Rockefeller was ...

, she wrote biographies of businessmen Elbert Henry Gary

Elbert Henry Gary (October 8, 1846August 15, 1927) was an American lawyer, county judge and business executive. He was a founder of U.S. Steel in 1901, bringing together partners J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and Charles M. Schwab. The city o ...

, chairman of U.S. Steel

United States Steel Corporation, more commonly known as U.S. Steel, is an American integrated steel producer headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with production operations primarily in the United States of America and in severa ...

, and Owen D. Young

Owen D. Young (October 27, 1874July 11, 1962) was an American industrialist, businessman, lawyer and diplomat at the Second Reparations Conference (SRC) in 1929, as a member of the German Reparations International Commission.

He is known for t ...

, president of General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable energ ...

.

A prolific writer and lecturer, Tarbell was known for taking complex subjects—the oil industry, tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

s, labor practices—and breaking them down into informative and easily understood articles. Her articles drove circulation at ''McClure’s Magazine'' and ''The American Magazine

''The American Magazine'' was a periodical publication founded in June 1906, a continuation of failed publications purchased a few years earlier from publishing mogul Miriam Leslie. It succeeded ''Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly'' (1876–1904), ' ...

'' and many of her books were popular with the general American public. After a successful career as both writer and editor for ''McClure’s Magazine'', Tarbell left with several other editors to buy and publish ''The American Magazine

''The American Magazine'' was a periodical publication founded in June 1906, a continuation of failed publications purchased a few years earlier from publishing mogul Miriam Leslie. It succeeded ''Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly'' (1876–1904), ' ...

''. Tarbell also traveled to all of the then 48 states on the lecture circuit and spoke on subjects including the evils of war, world peace

World peace, or peace on Earth, is the concept of an ideal state of peace within and among all people and nations on Planet Earth. Different cultures, religions, philosophies, and organizations have varying concepts on how such a state would ...

, American politics

The politics of the United States function within a framework of a constitutional federal republic and presidential system, with three distinct branches that Separation of powers, share powers. These are: the United States Congress, U.S. Congre ...

, trusts

A trust is a legal relationship in which the holder of a right gives it to another person or entity who must keep and use it solely for another's benefit. In the Anglo-American common law, the party who entrusts the right is known as the "settl ...

, tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

s, labor practices, and women's issues.

Tarbell took part in professional organizations and served on two Presidential committees. She helped form the Authors’ League (now the Author's Guild) and was President of the Pen and Brush Club for 30 years. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, she served on President Woodrow Wilson's Women's Committee on the Council of National Defense

The Council of National Defense was a United States organization formed during World War I to coordinate resources and industry in support of the war effort, including the coordination of transportation, industrial and farm production, financial s ...

. After the war, Tarbell served on President Warren G. Harding's 1921 Unemployment Conference.

Tarbell, who never married, is often considered a feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

by her actions, although she was critical of the women's suffrage movement

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to gran ...

.

Early life and education

Ida Minerva Tarbell was born on a farm inErie County, Pennsylvania

Erie County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is the northernmost county in Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 270,876. Its county seat is Erie. The county was created in 1800 and later organized in 1803.

...

, on November 5, 1857, to Esther Ann (née McCullough), a teacher, and Franklin Summer Tarbell, a teacher and a joiner

A joiner is an artisan and tradesperson who builds things by joining pieces of wood, particularly lighter and more ornamental work than that done by a carpenter, including furniture and the "fittings" of a house, ship, etc. Joiners may work in ...

and later an oilman. She was born in the log cabin home of her maternal grandfather, Walter Raleigh McCullough, a Scots-Irish pioneer, and his wife. Her father's distant immigrant ancestors had settled in New England in the 17th century. Tarbell was told by her grandmother that they were descended from Sir Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebellion ...

, a member of George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

's staff, and also the first American Episcopalian bishop. Tarbell had three younger siblings: Walter, Franklin, Jr., and Sarah. Franklin, Jr. died of scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects childr ...

at a young age and Sarah, also afflicted, would remain physically weakened throughout her life. Walter became an oilman like his father, while Sarah was an artist.

Ida Tarbell's early life in the oil fields of Pennsylvania would have an impact when she later wrote on the Standard Oil Company and on labor practices. The

Ida Tarbell's early life in the oil fields of Pennsylvania would have an impact when she later wrote on the Standard Oil Company and on labor practices. The Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was ...

hit the Tarbell family hard as banks collapsed and the Tarbells lost their savings. Franklin Tarbell was away in Iowa building a family homestead when Ida was born. Franklin had to abandon the Iowan house and return to Pennsylvania. With no money, he walked across the states of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to return, and supported himself along the way by teaching in rural schools. When he returned, ragged from his 18-month journey, young Ida Tarbell was said to have told him, "Go away, bad man!"

The Tarbells' fortune would turn as the Pennsylvania oil rush

The oil rush in America started in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in the Oil Creek (Allegheny River), Oil Creek Valley when Edwin L. Drake struck "rock oil" there in 1859. Titusville and other towns on the shores of Oil Creek expanded rapidly as oil w ...

began in 1859. They lived in the western region of Pennsylvania as new oil fields

A petroleum reservoir or oil and gas reservoir is a subsurface accumulation of hydrocarbons contained in porous or fractured rock formations.

Such reservoirs form when kerogen (ancient plant matter) is created in surrounding rock by the presence ...

were being developed, utterly changing the regional economy. Oil, she would write in her autobiography, opened “a rich field for tricksters, swindlers, exploiters of vice in every known form.” Tarbell's father first used his trade to build wooden oil storage tanks. The family lived in a shack with a workshop for Franklin in an oil field with twenty-five oil wells. Oil was everywhere in the sand, pits, and puddles. Tarbell wrote of the experience, "No industry of man in its early days has ever been more destructive of beauty, order, decency, than the production of petroleum."

In 1860, Ida's father moved the family to Rouseville, Pennsylvania

Rouseville is a borough in Venango County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 456 at the 2020 census.

Geography

Rouseville is located at (41.471398, -79.689469).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the borough has a tota ...

. Accidents that occurred in Rouseville impacted Ida Tarbell deeply. Town founder and neighbor Henry Rouse was drilling for oil when a flame hit natural gas coming from a pump. Rouse survived a few hours, which gave him just enough time to write his will and leave his million-dollar estate to the other settlers to build roads. In total, 18 men were killed, and the Tarbells' mother, Esther, cared for one of the burn victims in their home. In another incident, three women died in a kitchen explosion. Tarbell was not allowed to see the bodies, but she snuck into the room where the women awaited burial. Tarbell suffered from nightmares for the rest of her life.

After the Rouseville boom was finished in 1869, the family moved to Titusville, Pennsylvania

Titusville is a city in the far eastern corner of Crawford County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 5,601 at the 2010 census and an estimated 5,158 in 2019. Titusville is known as the birthplace of the American oil industry and for ...

. Tarbell's father built a family house at 324 Main Street using lumber and fixtures from the defunct Bonta Hotel in Pithole, Pennsylvania

Pithole, or Pithole City, is a ghost town in Cornplanter Township, Venango County, Pennsylvania, United States, about from Oil Creek State Park and the Drake Well Museum, the site of the first commercial oil well in the United States. Pithole's ...

.

Tarbell's father later became an oil producer and refiner in Venango County

Venango County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 50,454. Its county seat is Franklin. The county was created in 1800 and later organized in 1805.

Venango County comprises the Oil City, ...

. Franklin's business, along with those of many other small businessmen, was adversely affected by the South Improvement Company

The South Improvement Company was a short lived Pennsylvania corporation founded in late 1871 which existed until the state of Pennsylvania suspended its charter on April 2, 1872. It was created by major railroad and oil interests, and was widely ...

scheme (circa 1872) between the railroads and more substantial oil interests where in less than four months during what was later known as "The Cleveland Conquest" or "The Cleveland Massacre," Standard Oil absorbed 22 of its 26 Cleveland competitors. Later, Tarbell would vividly recall this event in her writing, in which she accused the leaders of the Standard Oil Company

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

of using unfair tactics to put her father and many small oil companies out of business. The South Improvement Company secretly worked with the railroads to raise the rates on oil shipment for independent oil men. The members of South Improvement Company received discounts and rebates to offset the rates and put the independents out of business. Franklin Tarbell participated against the South Improvement Company through marches and tipping over Standard Oil railroad tankers. The government of Pennsylvania eventually moved to disband the South Improvement Company.

The Tarbells were socially active, entertaining prohibitionists

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

and women's suffragists. Her family subscribed to ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'', ''Harper's Monthly'', and ''the New York Tribune'' and it was there that Ida Tarbell followed the events of the Civil War. Tarbell would also sneak into the family worker's bunkhouse to read copies of ''the Police Gazette''—a gruesome tabloid. Her family was Methodist and attended church twice a week. Esther Tarbell supported women's rights and entertained women such as Mary Livermore

Mary Livermore (born Mary Ashton Rice; December 19, 1820May 23, 1905) was an American journalist, abolitionist, and advocate of women's rights. Her printed volumes included: ''Thirty Years Too Late,'' first published in 1847 as a prize temperance ...

and Frances E. Willard

Frances Elizabeth Caroline Willard (September 28, 1839 – February 17, 1898) was an Americans, American educator, Temperance movement, temperance reformer, and women's suffrage, women's suffragist. Willard became the national president of Wom ...

.

Ida Tarbell was intelligent—but also undisciplined in the classroom. According to reports by Tarbell herself, she paid little attention in class and was often truant until one teacher set her straight: "She told me the plain and ugly truth about myself that day, and as I sat there, looking her straight in the face, too proud to show any feeling, but shamed as I never had been before and never have been since." Tarbell was especially interested in the sciences, and she began comparing the landscape around her in Pennsylvania to what she was learning in school. "Here I was suddenly on a ground which meant something to me. From childhood, plants, insects, stones were what I saw when I went abroad, what I brought home to press, to put into bottles, to litter up the house... I had never realized that they were subjects for study... School suddenly became exciting."

Tarbell graduated at the head of her high school class in Titusville and went on to study biology at

Ida Tarbell was intelligent—but also undisciplined in the classroom. According to reports by Tarbell herself, she paid little attention in class and was often truant until one teacher set her straight: "She told me the plain and ugly truth about myself that day, and as I sat there, looking her straight in the face, too proud to show any feeling, but shamed as I never had been before and never have been since." Tarbell was especially interested in the sciences, and she began comparing the landscape around her in Pennsylvania to what she was learning in school. "Here I was suddenly on a ground which meant something to me. From childhood, plants, insects, stones were what I saw when I went abroad, what I brought home to press, to put into bottles, to litter up the house... I had never realized that they were subjects for study... School suddenly became exciting."

Tarbell graduated at the head of her high school class in Titusville and went on to study biology at Allegheny College

he, תגל ערבה ותפרח כחבצלת

, mottoeng = "Add to your faith, virtue and to your faith, knowledge" (2 Peter 1:5)"The desert shall rejoice and the blossom as the rose" (Isaiah 35:1)

, faculty = 193 ...

in 1876, where she was the only woman in her class of 41. Tarbell had an interest in evolutionary biology—at her childhood home she spent many hours with a microscope—and said of her interest in science, "The quest for the truth had been born in me... the most essential of man's quests." One of Tarbell's professors, Jeremiah Tingley, allowed her to use the college's microscope for study and Tarbell used it to study the Common Mudpuppy

The common mudpuppy (''Necturus maculosus'') is a species of salamander in the genus ''Necturus''. They live an entirely aquatic lifestyle in parts of North America in lakes, rivers, and ponds. They go through paedomorphosis and retain their exte ...

, a foot-long amphibian that used both gills and a lung and thought to be a missing link.

Tarbell displayed leadership at Allegheny. She was a founding member of the local sorority that became the Mu chapter of the Kappa Alpha Theta

Kappa Alpha Theta (), also known simply as Theta, is an international women’s fraternity founded on January 27, 1870, at DePauw University, formerly Indiana Asbury. It was the first Greek-letter fraternity established for women. The main arch ...

sorority in 1876. Tarbell also led the charge to place sophomore stone

on campus dedicated to learning and with the Latin phrase, ''Spes sibi quisque'', which translates to "Everyone is his/her own hope". She was a member of the campus women's literary society, the Ossoli Society, named after writer Margaret Fuller Ossoli, and wrote for the society's publication, ''the Mosaic''. Tarbell graduated in 1880 with an A.B. degree and an M.A. degree in 1883. Tarbell later supported the university by serving on the board of trustees, to which she was first elected in 1912. She was the second woman to serve as a trustee and held the post for more than three decades.

Early career

Tarbell left school wanting to contribute to society but unsure of how to do it, she became a teacher. Tarbell began her career as headmistress at Poland Union Seminary in

Tarbell left school wanting to contribute to society but unsure of how to do it, she became a teacher. Tarbell began her career as headmistress at Poland Union Seminary in Poland, Ohio

Poland is a village in eastern Mahoning County, Ohio, United States. A suburb about southeast of Youngstown, the population was 2,463 at the 2020 census. It is a part of the Youngstown–Warren metropolitan area.

History

In 1796, Poland To ...

in August 1880. The school was both a high school and provided continuing education courses for local teachers. Tarbell taught classes in geology, botany, geometry, and trigonometry as well as languages: Greek, Latin, French, and German. After two years, she realized teaching was too much for her, and she returned home. She was exhausted by the workload and exasperated by the low wages which meant she had to borrow money from her parents.

Tarbell returned to Pennsylvania, where she met Theodore L. Flood, editor of ''The Chautauquan'', a teaching supplement for home study course

Distance education, also known as distance learning, is the education of students who may not always be physically present at a school, or where the learner and the teacher are separated in both time and distance. Traditionally, this usually in ...

s at Chautauqua, New York

Chautauqua ( ) is a town and lake resort community in Chautauqua County, New York, United States. The population was 4,017 at the 2020 census. The town is named after Chautauqua Lake. It is the home of the Chautauqua Institution and the birthplac ...

. Tarbell's family was familiar with the movement which encouraged adult education and self-study. She was quick to accept Flood's offer to write for the publication. Initially, Tarbell worked two weeks at the Meadville, Pennsylvania headquarters and worked two weeks at home. This allowed her to continue her own study at home in biology using microscopes. She became managing editor in 1886, and her duties included proofreading, answering reader questions, providing proper pronunciation of certain words, translating foreign phrases, identifying characters, and defining words.

Tarbell began writing brief items for the magazine and then worked up to longer features as she established her writing style and voice. Her first article was 'The Arts and Industries of Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

' and appeared in December 1886. According to Steve Weinberg in ''Taking on the Trust'', this was when Tarbell established a style that would carry throughout her career: "Tarbell would imbue her articles, essays, and books with moral content, grounded in her unwavering rectitude. That rectitude, while sometimes suggesting inflexibility, drove her instincts for reform, a vital element in her future confrontation with Rockefeller."

Tarbell wrote two articles that showcased her conflicting views on the roles of women that would follow her through her life. Tarbell's article, "Women as Inventors," was published in the March 1887 issue of ''The Chautauquan.'' When an article written by Mary Lowe Dickinson claimed the number of women patent owners to be about 300—and that women would never become successful inventors—Tarbell's curiosity was sparked and she began her own investigation. Tarbell traveled to the Patent Office in Washington, D.C. and met with the head of the department, R. C. McGill. McGill had put together a list of close to 2,000 women. Tarbell wrote in the article, "Three things worth knowing and believing: that women have invented a large number of useful articles; that these patents are not confined to 'clothes and kitchen' devices as the skeptical masculine mind avers; that invention is a field in which woman has large possibilities." Tarbell later followed this article up with a showcase on women in journalism in April 1887. The article contained history, journalism practices, and advice including a warning that journalism was an open field for women, and yet women should refrain from shedding tears easily and appearing weak.

Tarbell balked at being a "hired gal" and decided to strike out on her own after a falling out with Theodore Flood. Tarbell decided to follow her father's philosophy that it was better to work for oneself than to be a hired hand. She began researching women from history including Germaine de Staël

Anne Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein (; ; 22 April 176614 July 1817), commonly known as Madame de Staël (), was a French woman of letters and political theorist, the daughter of banker and French finance minister Jacques Necker and Suzan ...

and Madame Roland

Marie-Jeanne 'Manon' Roland de la Platière (Paris, March 17, 1754 – Paris, November 8, 1793), born Marie-Jeanne Phlipon, and best known under the name Madame Roland, was a French revolutionary, salonnière and writer.

Initially she led a ...

for inspiration and as subject matter for her writing. The real reason for the fall-out with Flood remains a mystery, but one reason may have been the placement of his son's name on the Masthead above Tarbell's own. Another hinted that her family had reason to seek revenge on him.

Paris in the 1890s

Leaving the security of ''The Chautauquan'', Tarbell moved to Paris in 1891 at age 34 to live and work. She shared an apartment on the Rue du Sommerard with three women friends from ''The Chautauquan''. The apartment was within a few blocks of thePanthéon

The Panthéon (, from the Classical Greek word , , ' empleto all the gods') is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was b ...

, Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris (; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris. The cathedral, dedicated to the ...

, and the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

. This was an exciting time in Paris, as the Eiffel Tower had been finished recently in 1889. Tarbell and her friends enjoyed the art produced by Impressionists

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open Composition (visual arts), composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating ...

including Degas

Edgar Degas (, ; born Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas, ; 19 July 183427 September 1917) was a French Impressionist artist famous for his pastel drawings and oil paintings.

Degas also produced bronze sculptures, prints and drawings. Degas is espec ...

, Monet

Oscar-Claude Monet (, , ; 14 November 1840 – 5 December 1926) was a French painter and founder of impressionist painting who is seen as a key precursor to modernism, especially in his attempts to paint nature as he perceived it. During ...

, Manet

A wireless ad hoc network (WANET) or mobile ad hoc network (MANET) is a decentralized type of wireless network. The network is ad hoc because it does not rely on a pre-existing infrastructure, such as routers in wired networks or access points ...

, and Van Gogh

Vincent Willem van Gogh (; 30 March 185329 July 1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter who posthumously became one of the most famous and influential figures in Western art history. In a decade, he created about 2,100 artworks, inclu ...

. Tarbell described the color of the art as "the blues and greens fairly howl they are so bright and intense." Tarbell attended the Can-can at the Moulin Rouge

Moulin Rouge (, ; ) is a cabaret in Paris, on Boulevard de Clichy, at Place Blanche, the intersection of, and terminus of Rue Blanche.

In 1889, the Moulin Rouge was co-founded by Charles Zidler and Joseph Oller, who also owned the Olympia (P ...

and in a letter to her family she advised them to read Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

's description of it in ''The Innocents Abroad'' as she didn't like to write about it.

Tarbell had an active social life in Paris. She and her flatmates hosted a language salon where both English and French speakers could come together and practice their non-native language skills. Her landlady, Madame Bonnet, held weekly dinners for the women and her other tenants. These tenants included young men from Egypt, and among them was Prince Said Toussoum, a cousin of the Egyptian ruler. Tarbell met and had a possible romance with Charles Downer Hazen, a future French historian and professor at Smith College.

Tarbell set about making her career as a writer in Paris. She supported herself by writing for several American newspapers including the ''

Tarbell set about making her career as a writer in Paris. She supported herself by writing for several American newspapers including the ''Pittsburgh Dispatch

The ''Pittsburgh Dispatch'' was a leading newspaper in Pittsburgh, operating from 1846 to 1923. After being enlarged by publisher Daniel O'Neill it was reportedly one of the largest and most prosperous newspapers in the United States. From 1880 ...

'', the ''Cincinnati Times-Star

''The Cincinnati Times-Star'' was an afternoon daily newspaper in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States, from 1880 to 1958. The Northern Kentucky edition was known as ''The Kentucky Times-Star'', and a Sunday edition was known as ''The Sunday Times-St ...

'', and the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television ar ...

''. Tarbell published the short story, ''France Adorée,'' in the December 1891 issue of ''Scribner's'' ''Magazine''. All of this work, along with a tutorship, helped Tarbell as she worked on her first biography, a book on Madame Roland

Marie-Jeanne 'Manon' Roland de la Platière (Paris, March 17, 1754 – Paris, November 8, 1793), born Marie-Jeanne Phlipon, and best known under the name Madame Roland, was a French revolutionary, salonnière and writer.

Initially she led a ...

: the leader of an influential ''salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon (P ...

'' during the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

. Tarbell already wanted to rescue women from the obscurity of history. Her research led her to an introduction to Leon Marillier, a descendant of Roland who provided access to Roland's letters and family papers. Mariller invited Tarbell to visit the Roland Country estate, Le Clos.

Tarbell continued her education in Paris and also learned investigative and research techniques used by French historians

This is a list of French historians limited to those with a biographical entry in either English or French Wikipedia. Major chroniclers, annalists, philosophers, or other writers are included, if they have important historical output. Names are lis ...

. Tarbell attended lectures at the Sorbonne—including those on the history of the French Revolution, 18th-century literature, and period painting. She learned from French historians how to present evidence in a clear, compelling style.

What Tarbell discovered about Madame Roland changed her own worldview. She began the biography with admiration for Roland but grew disillusioned as she researched and learned more. Tarbell determined that Roland, who followed her husband's lead, was not the independent thinker she had imagined and was complicit in creating an atmosphere where violence led to the Terror and her own execution. She wrote of Roland, "This woman had been one of the steadiest influences to violence, willing, even eager, to use this terrible revolutionary force, so bewildering and terrifying to me, to accomplish her ends, childishly believing herself and her friends strong enough to control it when they needed it no longer. The heaviest blow to my self-confidence so far was my loss of faith in revolution as a divine weapon. Not since I discovered the world not to have been made in six days...had I been so intellectually and spiritually upset."

It was during this time that Tarbell received bad news and then a shock. Franklin Tarbell's business partner had committed suicide, leaving Franklin in debt. Subsequently, a July 1892 newspaper announced that Tarbell's hometown of Titusville had been completely destroyed by flood and fire. Over 150 people died, and she feared her family was among them. Oil Creek had flooded and inflammable material on the water had ignited and exploded. Tarbell was relieved when she received a one-word cablegram that read: "Safe!" Her family and their home had been spared.

''McClure's Magazine''

Tarbell had published articles with the syndicate run by publisher Samuel McClure, and McClure had read a Tarbell article called ''The Paving of the Streets of Paris by Monsieur Alphand'', which described how the French carried out large public works. Impressed, McClure told his partner John S. Philips, "This girl can write. We need to get her to do some work for our magazine". The magazine he was referring to was ''McClure's

''McClure's'' or ''McClure's Magazine'' (1893–1929) was an American illustrated monthly periodical popular at the turn of the 20th century. The magazine is credited with having started the tradition of muckraking journalism (investigative journ ...

Magazine'', a new venture that he and Philips were intending to launch to appeal to the average middle-class reader. Convinced that Tarbell was just the kind of writer that he wanted to work for him, he showed up at Tarbell's door in Paris while on a scheduled visit to France in 1892 to offer her the editor position at the new magazine.

Tarbell described McClure as a "will-of-the-wisp

In folklore, a will-o'-the-wisp, will-o'-wisp or ''ignis fatuus'' (, plural ''ignes fatui''), is an atmospheric ghost light seen by travellers at night, especially over bogs, swamps or marshes. The phenomenon is known in English folk belief, ...

". He overstayed his visit, missed his train, and had to borrow $40 from Tarbell to travel on to Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

. Tarbell assumed she would never see the money, which was for her vacation, again but his offices wired over the money the next day. Tarbell initially turned him down so she could continue working on the Roland biography but McClure was determined. Next, the art director for ''McClure's'', August Jaccaci, made a visit to Tarbell to show her the maiden issue of the magazine.

Instead of taking up the editor position at ''McClure's'', Tarbell began writing freelance articles for the magazine. She wrote articles about women intellectuals and writers in Paris as well as scientists. She hoped articles such as "A Paris Press Woman" for the ''Boston Transcript'' in 1893 would provide a blueprint for women journalists and writers. She interviewed Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named afte ...

for an 1893 article, visiting with Pasteur and going through his family photographs for the magazine. She returned to Pasteur again to find out his views on the future. This piece turned into a regular report on "The Edge of the Future." Others interviewed for the report included Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

, Alphonse Daudet

Alphonse Daudet (; 13 May 184016 December 1897) was a French novelist. He was the husband of Julia Daudet and father of Edmée, Léon and Lucien Daudet.

Early life

Daudet was born in Nîmes, France. His family, on both sides, belonged to the ''bo ...

, and Alexandre Dumas ''fils''. Tarbell took on the role of the magazine's Paris representative. Tarbell was then offered the position of youth editor to replace Frances Hodgson Burnett

Frances Eliza Hodgson Burnett (24 November 1849 – 29 October 1924) was a British-American novelist and playwright. She is best known for the three children's novels ''Little Lord Fauntleroy'' (published in 1885–1886), '' A Little ...

. When her biography of Madame Roland was finished, Tarbell returned home and joined the staff of ''McClure's'' for a salary of $3,000 a year.

Napoleon Bonaparte

Tarbell returned from Paris in the summer of 1894, and, after a visit with family in Titusville, moved to New York City. In June of that year, Samuel McClure contacted her in order to commission a biographical series on French leaderNapoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

. McClure had heard that ''the Century Magazine

''The Century Magazine'' was an illustrated monthly magazine first published in the United States in 1881 by The Century Company of New York City, which had been bought in that year by Roswell Smith and renamed by him after the Century Associatio ...

'', ''McClure's'' rival, was working on a series of articles about Bonaparte. Tarbell stayed at Twin Oaks in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, the home of Gardiner Green Hubbard, while working on the series. Tarbell made use of Hubbard's extensive collection of Napoleon material and memorabilia as well as resources at the Library of Congress and the U.S. State Department. Tarbell's schedule for the book was tight—the first installment came out only six weeks after she initially started her work. Tarbell called this "biography on a gallop."

The series proved to be a training ground for Tarbell's style and methodology for biographies. Tarbell believed in the Great man theory of biography and that extraordinary individuals could shape their society at least as much as society shaped them. While working on the series, Tarbell was introduced to historian and educator Herbert B. Adams of Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hem ...

. Adams believed in the "objective interpretation of primary sources" which would also become Tarbell's method for writing about her subjects. Adams also taught at Smith College

Smith College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts Women's colleges in the United States, women's college in Northampton, Massachusetts. It was chartered in 1871 by Sophia Smith (Smith College ...

and was a proponent for women's education.

This series of articles would solidify Tarbell's reputation as a writer, opening up new avenues for her. The Napoleon series proved popular and doubled circulation up to over 100,000 on ''McClures magazine—quadrupling the readership by the final seventh Napoleon installment. It included illustrations from the Gardiner Green Hubbard collection. The articles were folded into a book that would be a best seller and earn Tarbell royalties for the rest of her life—over 70,000 copies were made of the first edition. Tarbell said that her sketch of Napoleon turned her plans "topsy-turvy." Because of its popularity, Tarbell was also finally able to find a publisher—Scribner's—for her Madame Roland book.

Abraham Lincoln

Another ''McClure's'' story meant to compete against ''Century Magazine'' was on US presidentAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, on whom ''Century'' had published a series by his private secretaries, John Nicolay

John George Nicolay (February 26, 1832 – September 26, 1901) was a German-born American author and diplomat who served as private secretary to U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and later co-authored '' Abraham Lincoln: A History'', a biography of t ...

and John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, Hay's highest office was Un ...

. At first, Tarbell was reluctant to take up work on Lincoln as she later said, "If you once get into American history, I told myself, you know well enough that will finish France." At the same time, however, Tarbell had been fascinated with Lincoln since she was a young girl. She remembered the news of his assassination and her parents' reaction to it: her father coming home from his shop, her mother burying her "face in her apron, running into her room sobbing as if her heart would break."

When Tarbell first approached John Nicolay, he told her that he and Hay had written "all that was worth telling of Lincoln". Tarbell decided to begin with Lincoln's origins and his humble beginnings. Tarbell traveled the country meeting with and interviewing people who had known Lincoln—including his son Robert Todd Lincoln

Robert Todd Lincoln (August 1, 1843 – July 26, 1926) was an American lawyer, businessman, and politician. He was the eldest son of President Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln. Robert Lincoln became a business lawyer and company presid ...

. Robert Lincoln shared with Tarbell an early and previously unpublished daguerreotype of Lincoln as a younger man. She followed up on a lost 1856 speech by Lincoln by tracking down Henry Clay Whitney

Henry Clay Whitney (23 February 1831 – 27 February 1905) was a United States lawyer who was a close friend of President Abraham Lincoln, and later a biographer of the president.

Life

Henry Clay Whitney was born on 23 February 1831 in Detroit, ...

—who claimed to have written down notes—and then confirming his notes via other witnesses. Whitney's version of the speech was published in ''McClure's'', but has since been disproved by other historians.

Tarbell's research in the backwoods of Kentucky and Illinois uncovered the true story of Lincoln's childhood and youth. She wrote to and interviewed hundreds of people who knew or had contact with Lincoln. She tracked down leads and then confirmed their sources. She sent hundreds of letters looking for images of Lincoln and found evidence of more than three hundred previously unpublished Lincoln letters and speeches. Tarbell met with John H. Finley while visiting Knox College where Lincoln famously debated Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which was ...

in 1858. Finley was the young college President, and he would go on to contribute to Tarbell's work on Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

and rise to become the editor of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

''. Tarbell traveled abroad to Europe, discovering that a rumor that Lincoln had appealed to Queen Victoria to not recognize the Confederacy was, in fact, false.

By December 1895, the popular series by Tarbell once again helped boost ''McClure's'' circulation to over 250,000 which climbed to over 300,000, by 1900, making it higher than its rivals. This occurred even as the editors at ''Century's Magazine'' sneered, "They got a girl to write the Life of Lincoln." McClure would go on to use the money generated by Tarbell's articles to buy a printing plant and a bindery.

It was at this time that Tarbell decided to be a writer and not an editor. The articles were collected in a book, giving Tarbell a national reputation as a major writer and the leading authority on the slain president. Tarbell published five books about Lincoln and traveled on the lecture circuit, recounting her discoveries to large audiences.

The tight writing schedules and frequent travel eventually impacted Tarbell's health. On the verge of physical collapse, she checked into the Clifton Springs Sanitarium

Clifton Springs Sanitarium is a historic sanitarium building located at the village of Clifton Springs in Ontario County, New York. Construction of the sanitarium building began in 1892 as a five-story ell-shaped brick structure in the Richard ...

near Rochester, New York in 1896. Besides rest and relaxation, her treatment included taking the water cure Water cure may refer to:

* Water cure (therapy), a course of medical treatment by hydrotherapy

* Water cure (torture), a form of torture in which a person is forced to drink large quantities of water

* ''The Water Cure'', a 1916 film starring Olive ...

. She would visit the Sanitarium numerous times over the next thirty years.

Editorship

Tarbell continued to write profiles for McClure in the late 1890s. While there, she had the opportunity to observe theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

expansion into imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

through the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

. She was writing a series on military affairs, and in 1898 she was set to interview Nelson A. Miles

Nelson Appleton Miles (August 8, 1839 – May 15, 1925) was an American military general who served in the American Civil War, the American Indian Wars, and the Spanish–American War.

From 1895 to 1903, Miles served as the last Commanding Gen ...

, the commanding general of the United States, when the battleship the USS ''Maine'' was blown up in Havana Harbor. Tarbell was allowed to keep her appointment nonetheless and observe the response at the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

Headquarters. Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

was already organizing what would become the Rough Riders

The Rough Riders was a nickname given to the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry, one of three such regiments raised in 1898 for the Spanish–American War and the only one to see combat. The United States Army was small, understaffed, and diso ...

, and Tarbell said that he kept bursting into the Army office, "like a boy on roller skates." Tarbell longed for her old life in Paris, but realized she was needed in America: "Between Lincoln and the Spanish–American War s it became knownI realized I was taking on a citizenship I had practically resigned".

Tarbell moved to New York and accepted a position as desk editor for ''McClure's'' in 1899. She was paid $5,000 a year and given shares in the company, which made her a part-owner. She rented an apartment in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

which reminded her of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. She frequented the Hotel Brevoort, where Samuel Clemens

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has pr ...

(Mark Twain) also dined.

Her position as editor was to fill in for Samuel McClure, as he was planning to be away from the office for several months. Tarbell was to become known as an anchor in the office while the magazine built out its roster of investigative editors and authors. She and Phillips were described as the "control" to S. S. McClure's "motor." ''McClure's'' sent Stephen Crane to cover Cuba during the War. Ray Stannard Baker was hired by the magazine to report on the Pullman Strike. Fiction editor Violo Roseboro discovered writers such as O. Henry, Jack London

John Griffith Chaney (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to ...

, and Willa Cather

Willa Sibert Cather (; born Wilella Sibert Cather; December 7, 1873 – April 24, 1947) was an American writer known for her novels of life on the Great Plains, including ''O Pioneers!'', '' The Song of the Lark'', and ''My Ántonia''. In 1923, ...

. John Huston Finley quit his job as president of Knox College and became an editor for ''McClure's''.

Standard Oil

By the turn of the twentieth century ''McClure's'' began an effort to "expose the ills of American society." Having recently published a series on crime in America and were looking for another big topic to cover, Tarbell and the other editors at ''McClure's'' decided to look into the growth of trusts: steel and sugar were both considered before they settled on oil. There were a number of reasons why the magazine decided to publish a story onStandard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

: in particular, Tarbell's own first-hand experience with life in the Pennsylvania oil fields and the fact that Standard Oil was a trust represented by only one person, Rockefeller, and therefore might make the story easier to follow. Tarbell traveled to Europe and met with S. S. McClure to get his buy-in for the idea. McClure had been resting from exhaustion, but Tarbell's article idea spurred him into action. They discussed the idea over many days at a spa

A spa is a location where mineral-rich spring water (and sometimes seawater) is used to give medicinal baths. Spa towns or spa resorts (including hot springs resorts) typically offer various health treatments, which are also known as balneoth ...

in Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

. McClure felt that Tarbell should use the same biographical sketch format she used for Napoleon.

On her return to the states, Tarbell handed over the desk editor role to Lincoln Steffens

Lincoln Austin Steffens (April 6, 1866 – August 9, 1936) was an American investigative journalist and one of the leading muckrakers of the Progressive Era in the early 20th century. He launched a series of articles in ''McClure's'', called "Twe ...

in 1901, and began a meticulous investigation with the help of an assistant (John Siddall) into how the industry began, Rockefeller's early interest in oil, and the Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

trust.

Tarbell's father expressed concern to her about writing about Standard Oil warning her that Rockefeller would stop at nothing and would ruin the magazine. One of Rockefeller's banks did indeed threaten the magazine's financial status to which Tarbell shocked the bank executive by replying, "Of course that makes no difference to me".

Tarbell developed investigative reporting techniques, delving into private archives and public documents across the country. The documentation and oral interviews she gathered proved Standard Oil had used strong-arm tactics and manipulated competitors, railroad companies and others to reach its corporate goals. Organized by Tarbell into a cogent history, they became a "damning portrayal of big business" and a personal "account of petty persecution" by Rockfeller. A subhead on the cover of Weinberg's book encapsulates it this way: "How a female investigative journalist brought down the world's greatest tycoon and broke up the Standard Oil monopoly".

Tarbell was able to find one critical piece of information that had gone missing—a book called ''the Rise and Fall of the South Improvement Company'' which had been published in 1873. Standard Oil and Rockefeller had its roots in the South Improvement Company's illegal schemes. Standard Oil had attempted to destroy all available copies of the book, but Tarbell was finally able to locate one copy in the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress) ...

.

Another break in the story came from within Standard Oil itself and proved that the company was still using illegal and shady practices. An office boy working at the Standard Oil headquarters was given the job of destroying records which included evidence that railroads were giving the company advance information about refiner's shipments. This allowed them to undercut the refiners. The young man happened to notice his Sunday school teacher's name on several documents. The teacher was a refiner, and the young man took the papers to his teacher who passed them along to Tarbell in 1904. The series and book on Standard Oil brought Tarbell fame. The book was adapted into a play in 1905 called ''The Lion and the Mouse''. The play was a hit even though Ida had turned down the lead role and an offer of $2,500 in salary per week for the twenty-week run.

Samuel Clemens (author Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

), introduced Tarbell to Henry H. Rogers

Henry Huttleston Rogers (January 29, 1840 – May 19, 1909) was an American industrialist and financier. He made his fortune in the oil refining business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil. He also played a major role in numerous corporations a ...

, vice-president at Standard Oil and considered to be the third man after John D. Rockefeller and his brother William Rockefeller

William Avery Rockefeller Jr. (May 31, 1841 – June 24, 1922) was an American businessman and financier. Rockefeller was a co-founder of Standard Oil along with his elder brother John Davison Rockefeller. He was also part owner of the Anaconda ...

. Rogers had begun his career during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

in western Pennsylvania oil regions where Tarbell had grown up. Rockefeller had bought out Rogers and his partner, but then Rogers joined the trust. In early 1902 she conducted numerous detailed interviews with Rogers at Standard Oil's headquarters. Rogers, wily and normally guarded in matters related to business and finance, may have been under the impression her work was to be complimentary and was apparently unusually forthcoming. Even after the first articles began to appear in ''McClure’s'', Rogers continued to speak with Tarbell, much to her surprise.

Her investigative journalism

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, such as serious crimes, political corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. An investigative journalist may spend months or years rese ...

on Standard Oil was serialized in nineteen articles that ran from November 1902 to 1904 in ''McClure's;'' her first article being published with pieces by Lincoln Steffens

Lincoln Austin Steffens (April 6, 1866 – August 9, 1936) was an American investigative journalist and one of the leading muckrakers of the Progressive Era in the early 20th century. He launched a series of articles in ''McClure's'', called "Twe ...

and Ray Stannard Baker

Ray Stannard Baker (April 17, 1870 – July 12, 1946) (also known by his pen name David Grayson) was an American journalist, historian, biographer, and author.

Biography

Baker was born in Lansing, Michigan. After graduating from the Michigan ...

. Together these ushered in the era of muckraking

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists, writers, and photographers in the Progressive Era in the United States (1890s–1920s) who claimed to expose corruption and wrongdoing in established institutions, often through sensationalist publ ...

journalism.

Tarbell's biggest obstacle, however, was neither her gender nor Rockefeller's opposition. Rather, her biggest obstacle was the craft of journalism as practiced at the turn of the twentieth century. She investigated Standard Oil and Rockefeller by using documents— hundreds of thousands of pages scattered throughout the nation—and then amplified her findings through interviews with the corporation's executives and competitors, government regulators, and academic experts past and present. In other words, she proposed to practice what today is considered investigative reporting, which did not exist in 1900. Indeed, she invented a new form of journalism.Magazine historian

Frank Luther Mott

Frank Luther Mott (April 4, 1886 – October 23, 1964) was an American historian and journalist, who won the 1939 Pulitzer Prize for History for Volumes II and III of his series, ''A History of American Magazines''.

Early life and education

Mott w ...

called it, "one of the greatest serials ever to appear in an American magazine." It would contribute to the dissolution of Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

as a monopoly and lead to the Clayton Antitrust Act

The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 (, codified at , ), is a part of United States antitrust law with the goal of adding further substance to the U.S. antitrust law regime; the Clayton Act seeks to prevent anticompetitive practices in their incipie ...

.

Tarbell concluded the series with a two-part character study of Rockefeller, perhaps the first CEO profile ever, though she never met or even talked to him. Rockefeller called Tarbell, "Miss Tarbarrel".

The first book-length investigation of Standard Oil had appeared in 1894 by newspaperman

The first book-length investigation of Standard Oil had appeared in 1894 by newspaperman Henry Demarest Lloyd

Henry Demarest Lloyd (May 1, 1847 – September 28, 1903) was a 19th-century American progressive political activist and pioneer muckraking journalist. He is best remembered for his exposés of the Standard Oil Company, which were written before ...

. However, this book, ''Wealth Against Commonwealth

''Wealth Against Commonwealth'' is a book published by muckraking journalist Henry Demarest Lloyd. It was published after he had written several essays to ''The Atlantic Monthly'' concerning issues with dominating monopolies. It was written in an ...

'', contained factual errors and appeared to be too accusatory in nature to garner popular acclaim. However Tarbell's articles when collected in the book, ''The History of the Standard Oil Company

''The History of the Standard Oil Company'' is a 1904 book by journalist Ida Tarbell. It is an exposé about the Standard Oil Company, run at the time by oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller, the richest figure in American history. Originally serializ ...

'' (1904). became a bestseller, which was called a "masterpiece of investigative journalism" by author and historian J. North Conway. Her articles and the book would lead to the passage of the Hepburn Act

The Hepburn Act is a 1906 United States federal law that expanded the jurisdiction of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) and gave it the power to set maximum railroad rates. This led to the discontinuation of free passes to loyal shippers. ...

in 1906 to oversee the railroads, the 1910 Mann-Elkins Act which gave the Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later trucking) to ensure fair rates, to eliminat ...

power over oil rates, and the creation of the Federal Trade Commission

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is an independent agency of the United States government whose principal mission is the enforcement of civil (non-criminal) antitrust law and the promotion of consumer protection. The FTC shares jurisdiction ov ...

(FTC) in 1914.

President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

gave Tarbell and her peers including Lincoln Steffens

Lincoln Austin Steffens (April 6, 1866 – August 9, 1936) was an American investigative journalist and one of the leading muckrakers of the Progressive Era in the early 20th century. He launched a series of articles in ''McClure's'', called "Twe ...

and Ray Stannard Baker

Ray Stannard Baker (April 17, 1870 – July 12, 1946) (also known by his pen name David Grayson) was an American journalist, historian, biographer, and author.

Biography

Baker was born in Lansing, Michigan. After graduating from the Michigan ...

the label, "muckraker

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists, writers, and photographers in the Progressive Era in the United States (1890s–1920s) who claimed to expose corruption and wrongdoing in established institutions, often through sensationalist publ ...

s." Tarbell's exposé of Standard Oil first appeared in the January 1903 issue of ''McClure's'' along with Steffens' investigation of political corruption in Minneapolis and Baker's exposé on labor union practices. The term muckraker came from John Bunyan

John Bunyan (; baptised 30 November 162831 August 1688) was an English writer and Puritan preacher best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory ''The Pilgrim's Progress,'' which also became an influential literary model. In addition ...

's ''Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in English literature and a progenitor of ...

'' describing a Man with a Muckrake forever clearing muck from the floor. Roosevelt said of the muckrakers, "The man who never does anything else, who never thinks or speaks or writes save of his feats with the muckrake, speedily becomes, not a help to society, not an incitement to good, but one of the most potent forces of evil". Tarbell disliked the muckraker label and wrote an article, "Muckraker or Historian," in which she justified her efforts for exposing the oil trust. She referred to "this classification of muckraker, which I did not like. All the radical element, and I numbered many friends among them, were begging me to join their movements. I soon found that most of them wanted attacks. They had little interest in balanced findings. Now I was convinced that in the long run the public they were trying to stir would weary of vituperation, that if you were to secure permanent results the mind must be convinced."

''The American Magazine''