Hungarians

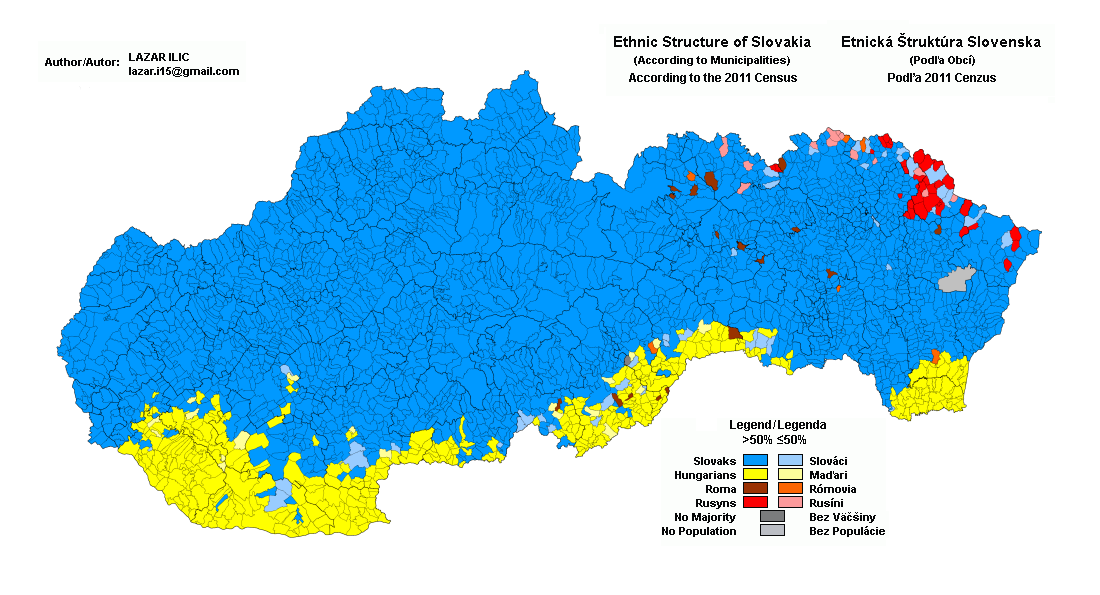

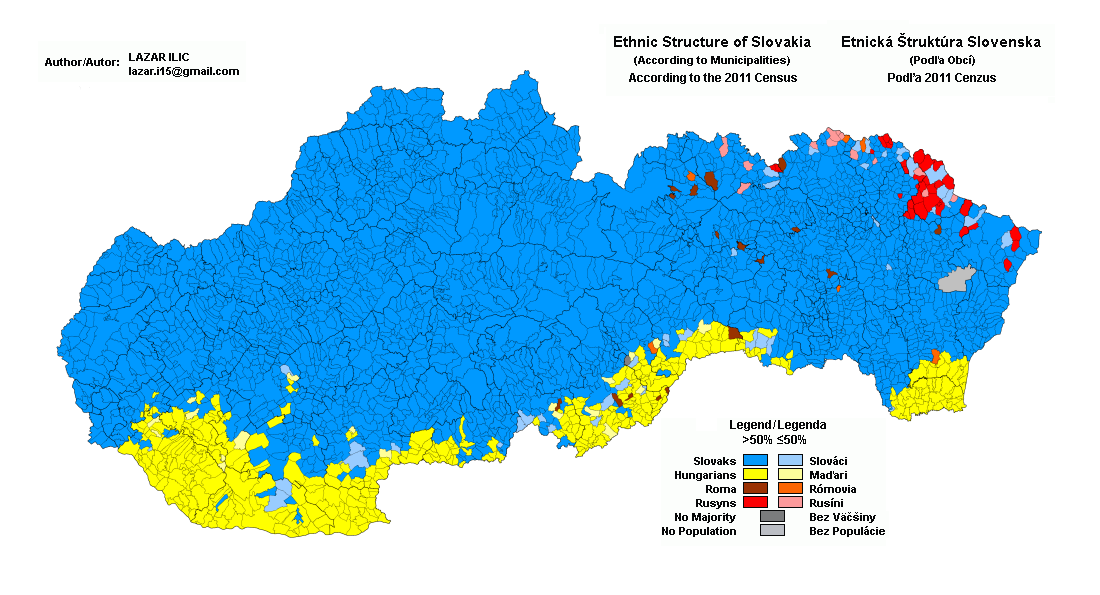

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

are the largest ethnic minority in

Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

. According to th

2021 Slovak census 422,065 people (or 7.75% of the population) declared themselves Hungarians, while 462,175 (8.48% of the population) stated that

Hungarian was their mother tongue.

Hungarians in Slovakia are concentrated mostly in the southern part of the country, near the border with

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

. They form the majority in two districts,

Komárno and

Dunajská Streda

Dunajská Streda (; hu, Dunaszerdahely; german: Niedermarkt; he, דונהסרדהיי) is a town located in southern Slovakia ( Trnavský kraj). Dunajská Streda is the most culturally significant town in the Žitný ostrov area. The town has a p ...

.

History

The First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1938)

Origins of the Hungarian minority

After the defeat of the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

on the Western Front in 1918, the

Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles on 4 June 1920. It forma ...

was signed between the winning

Entente powers and Hungary in 1920 at the Paris Peace Conference. The treaty greatly reduced the

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

's borders, including ceding all of

Upper Hungary

Upper Hungary is the usual English translation of ''Felvidék'' (literally: "Upland"), the Hungarian term for the area that was historically the northern part of the Kingdom of Hungary, now mostly present-day Slovakia. The region has also been ...

to Czechoslovakia, in which Slovaks made up the dominant ethnicity. In consideration of the strategic and economic interests of their new ally, Czechoslovakia, the victorious allies set the Czechoslovak–Hungarian border further south than the Slovak–Hungarian language border. Consequently, the newly created state contained areas that were overwhelmingly ethnic Hungarian.

Demographics

According to the 1910 census conducted in

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, there were 884,309 ethnic Hungarians, constituting 30.2% of the population in what is now Slovakia and

Carpatho-Ukraine. The Czechoslovak census of 1930 recorded 571,952 Hungarians. In the 2001 census, by contrast, the percentage of ethnic Hungarians in Slovakia was 9.7%, a decrease of two-thirds in percentage but not in absolute number, which remained roughly the same.

Czechoslovak and Hungarian censuses are often used in political discussions, but they were not fully compliant and they did not measure the same data. According to the official Hungarian definition from 1900, a "mother tongue" was defined as a language ''"considered by a person as his own, the best spoken and mostly preferred"''. This definition did not match the real definition of mother tongue, introduced subjective factors dependent on environment and opened the way for various interpretations. Further, in the atmosphere of raising

magyarization

Magyarization ( , also ''Hungarization'', ''Hungarianization''; hu, magyarosítás), after "Magyar"—the Hungarian autonym—was an assimilation or acculturation process by which non-Hungarian nationals living in Austro-Hungarian Transleitha ...

, a person could be at risk if he did not declare Hungarian to be his favorite for a census commissar. Between 1880 and 1910, the Hungarian population increased by 55.9%, while Slovak population increased by only 5.5% though Slovaks had a higher

birth rate

The birth rate for a given period is the total number of live human births per 1,000 population divided by the length of the period in years. The number of live births is normally taken from a universal registration system for births; populati ...

at the same time. The level of differences does not explain this process by emigration (higher among Slovaks) or by population moves and natural assimilation during industrialization. In 16 northern counties, the Hungarian population rose by 427,238, while the majority Slovak population rose only by 95,603. The number of "Hungarians who can speak Slovak" unusually increased in a time when Hungarians really had no motivation to learn it – by 103,445 in southern Slovakia in absolute numbers, by 100% in

Pozsony,

Nyitra

Nitra (; also known by other alternative names) is a city in western Slovakia, situated at the foot of Zobor Mountain in the valley of the river Nitra. It is located 95 km east of Bratislava. With a population of about 78,353, it is the fifth l ...

,

Komárom,

Bars and

Zemplén County and more than 3 times in Košice. After the creation of Czechoslovakia, people could declare their nationality more freely.

Furthermore, censuses from the

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

and

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

differed in their view on the nationality of the Jewish population.

[History, the development of the contact situation and demographic data](_blank)

gramma.sk Czechoslovakia allowed

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

to declare a separate

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

nationality, while Jews were counted mostly as Hungarians in the past. In 1921, 70,529 people declared Jewish nationality.

The population of larger towns like

Košice

Košice ( , ; german: Kaschau ; hu, Kassa ; pl, Коszyce) is the largest city in eastern Slovakia. It is situated on the river Hornád at the eastern reaches of the Slovak Ore Mountains, near the border with Hungary. With a population of a ...

or

Bratislava

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approximately 140% of ...

were historically bilingual or trilingual, and some might declare the most-popular or the most-beneficial nationality at a particular time. According to the Czechoslovak censuses, 15–20% of the population in Košice was Hungarian, but during the parliamentary elections, the "ethnic" Hungarian parties received 35–45% of the total votes (excluding those Hungarians who voted for the Communists or the Social Democrats). However, such comparisons are not fully reliable, because "ethnic" Hungarian parties did not necessarily present themselves to Slovak population as "ethnic", and also had Slovak subsidiaries.

Hungarian state employees who refused to take an oath of allegiance had to decide between retirement and moving to Hungary. The same applied to Hungarians who did not receive Czechoslovak citizenship, who were forced to leave or simply did not self-identify with the new state. Two examples of people forced to leave were the families of

Béla Hamvas

Béla Hamvas (23 March 1897 – 7 November 1968) was a Hungarian writer, philosopher, and social critic. He was the first thinker to introduce the Traditionalist School of René Guénon to Hungary.

Biography

Béla Hamvas was born on 23 Marc ...

and

Albert Szent-Györgyi. The numerous refugees (including even more from

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

) necessitated the construction of new housing projects in

Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population o ...

(Mária-Valéria telep, Pongrácz-telep), which gave shelter to refugees numbering at least in the tens of thousands.

Education

At the beginning of the school year 1918–19, Slovakia had 3,642 elementary schools. Only 141 schools taught in Slovak, 186 in Slovak and Hungarian and 3,298 in Hungarian. After system reform, Czechoslovakia provided an educational network for the region. Due to the lack of qualified personnel among Slovaks – a lack of schools above elementary level, banned grammar schools and no Slovak teacher institutes – Hungarian teachers were replaced in large numbers by Czechs. Some Hungarian teachers resolved their existential question by moving to Hungary. According to government regulation from 28 August 1919, Hungarian teachers were permitted to teach only if they took an oath of allegiance to Czechoslovakia.

In the early years of Czechoslovakia, the Hungarian minority in Slovakia had a complete education network, except for canceled colleges. The Czechoslovak Ministry of Education derived its policy from international agreements signed after the end of World War I. In the area inhabited by the Hungarian minority, Czechoslovakia preserved untouched the network of Hungarian municipal or denominational schools. However, these older schools inherited from

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

were frequently crowded, under-funded, and less attractive than new, well-equipped Slovak schools built by the state.

[Béla László (2004). "Maďarské národnostné školstvo". In.: ''Madari na Slovensku (1989–2004) / Magyarok Szlovákiában (1989–2004)''. Eds: József Fazekas, Péter Huncík. Šamorín: Fórum inštitút pre výskum menšín. . ] In the school year 1920–21, the Hungarian minority had 721 elementary schools, which only decreased by one in the next 3 years. Hungarians had also 18 higher "burgher" schools, 4 grammar schools and 1 teacher institute. In the school year 1926–27, there were 27 denominational schools which can also be classified as minority schools, because none of them taught in Slovak. Hungarian representatives criticized the mainly reduced number of secondary schools.

In the 1930s, Hungarians had 31 kindergartens, 806 elementary schools, 46 secondary schools, and 576 Hungarian libraries at schools. A department of

Hungarian literature

Hungarian literature is the body of written works primarily produced in Hungarian, was created at the

Charles University of Prague.

[Marko, Martinický: ''Slovensko-maďarské vzťahy''. 1995]

Hungarian Elisabeth Science University, founded in 1912 and teaching since 1914 (with interruptions during war), was replaced by

Comenius University

Comenius University in Bratislava ( sk, Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave) is the largest university in Slovakia, with most of its faculties located in Bratislava. It was founded in 1919, shortly after the creation of Czechoslovakia. It is name ...

to fulfill demands for qualified experts in Slovakia. Hungarian professors had refused to take an oath of allegiance and the original school was closed by government decree; as in other cases, teachers were replaced by Czech professors. Comenius University remained the only university in inter-war Slovakia.

Culture

The Hungarian minority participated in a press boom in Czechoslovakia between wars. Before the creation of Czechoslovakia, 220 periodicals were issued in the territory of Slovakia, 38 of them in Slovak. During the interwar period, the number of Slovak and Czech periodicals in Slovakia increased to more than 1,050, while the number of periodicals in minority languages (mostly Hungarian) increased almost to 640 (only a small portion of these were published through the entire interwar period).

The Czechoslovak state preserved and financially supported two Hungarian professional theatre companies in Slovakia and an additional one in

Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

. Hungarian cultural life was maintained in regional cultural associations like Jókai Society, Toldy Group or Kazinczy Group. In 1931, the Hungarian Scientific, Literary and Artistic Society in Czechoslovakia (Masaryk's Academy) was founded on the initiative of the Czechoslovak president. Hungarian culture and literature was covered by journals like ''Magyar Minerva'', ''Magyar Irás'', ''Új Szó'' and ''Magyar Figyelő''. The last of these had the goal to develop Czech–Slovak–Hungarian literary relationships and a common Czechoslovak consciousness. Hungarian books were published by several literary societies and Hungarian publishers, though not in great number.

Policy

The democratization of Czechoslovakia extended political rights of the Hungarian population in comparison to the

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

before 1918. Czechoslovakia introduced

universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political sta ...

, while full

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

was not achieved in Hungary until 1945. The first Czechoslovak parliamentary elections had 90% voter-turnout in Slovakia. After the

Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles on 4 June 1920. It forma ...

, the Hungarian minority lost illusions about a "temporary state" and had to adapt to a new situation. Hungarian political structures in Czechoslovakia were formed relatively late and finalized their formation only in the mid-1920s. The political policy of the Hungarian minority can be categorized by their attitude to the Czechoslovak state and peace treaties into three main directions: activists, communists, and negativists.

Hungarian "activists" saw their future in cohabitation and cooperation with the majority population. They had a pro-Czechoslovak orientation and supported the government. In the early 1920s, they founded separate political parties and were later active in Hungarian sections of Czechoslovak statewide parties. The pro-Czechoslovak Hungarian National Party (not to be confused with a different Hungarian National Party formed later) participated in the parliamentary elections of 1920, but failed. In 1922, the Czechoslovak government proposed correction of some injustices against minorities in exchange for absolute loyalty and recognition of the Czechoslovak state. Success of activism culminated in the mid-1920s. In 1925, the Hungarian National Party participated in the adoption of several important laws, including those regulating state citizenship. In 1926, the party unsuccessfully held negations about participation in government. Left-wing Hungarian activists were active in the

Hungarian-German Social Democratic Party and later in the Hungarian Social Democratic Labor Party. Hungarian social democrats failed in competition with communists but were active as a Hungarian section of the

Czechoslovak Social Democracy Party (ČSDD). In 1923, Hungarian activists with agrarian orientation founded the Republican Association of Hungarian Peasants and Smallholders but this party failed similarly to the Hungarian-minority's Provincial Peasant Party. Like social-democrats, Hungarian agrarians created a separate section within the statewide

Agrarian Party (A3C). Hungarian activism had a stable direction but was not able to become dominant power due to various reasons like land reform or revisionist policies of the Hungarian government.

The

Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia ( Czech and Slovak: ''Komunistická strana Československa'', KSČ) was a communist and Marxist–Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992. It was a member of the Comint ...

(KSČ) had above-average support among the Hungarian minority. In 1925, party received 37.5% in

Kráľovský Chlmec

Kráľovský Chlmec (; until 1948 ''Kráľovský Chlumec'', hu, Királyhelmec) is a town in the Trebišov District in the Košice Region of south-eastern Slovakia. It has a population of around 8,000.

Etymology

The name means "Royal Hill". Slov ...

district and 29.7% in

Komárno district, compared to the Slovak average of 12–13%.

Hungarian "negativists" were organized in opposition parties represented by right-wing

Provincial Christian-Socialist Party

The Provincial Christian-Socialist Party ( hu, Országos Keresztényszocialista Párt, OKszP; cs, Zemská křesťansko-socialistická strana; german: Provinziell-Christlich-Sozialistische Partei) was the main political party of ethnic Hungarians ...

(OKSZP) and

Hungarian National Party Hungarian National Party ( hu, Magyar Nemzeti Párt, MNP, cs, Maďarská národní strana, sk, Maďarská národná strana) was one of political parties of ethnic Hungarians in the First Republic of Czechoslovakia.

The party was founded in Febru ...

(MNP) (not to be confused with Hungarian National Party above). The OKSZP was supported mainly by the Roman Catholic population, and the MNP by Protestants. The parties differed also by their views on collaboration with the government coalition, the MNP considered collaboration in some periods while the OKSZP was in steadfast opposition and tried to cross ethnic boundaries to gain support from the Slovak population. This attempt was partially successful and the OKSZP had 78 Slovak sections and a Slovak-language journal. Attempts to create a coalition of Hungarian opposition parties with the largest Slovak opposition party –

Hlinka's Slovak People's Party (HSĽS) – were unsuccessful due to fear of Hungarian revisionist policy and potential discredit after the affair of

Vojtech Tuka who was uncovered as a Hungarian spy.

In 1936, both "negativist" parties united as the United Hungarian Party (EMP) under direct pressure of the Hungarian government and threat of an end to financial support. The party became dominant in 1938 and received more than 80% of Hungarian votes. "Negativistic" parties were considered to be a potential danger to Czechoslovakia and many Hungarian-minority politicians were monitored by police.

Issues in mutual relationships

After

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Hungarians found themselves in the difficult position of a "superior" nation which had become a national minority. Dissolution of the historical

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

was understood as an artificial and violent act, rather than a failure of the anti-national and conservative policy of the Hungarian government.

During the whole interwar period, Hungarian society preserved archaic views on the Slovak nation. According to such obsolete ideas, Slovaks were tricked by Czechs, became victims of their power politics and dreamed about returning to a Hungarian state.

From these positions, the Hungarian government tried to restore pre-war borders and drove the policy of opposition minority parties.

In Czechoslovakia, peripheral areas like southern Slovakia suffered from a lack of investment and had difficulties recovering from the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. The Czechoslovak government focused more on stabilization of relationships with Germany and

Sudeten Germans

German Bohemians (german: Deutschböhmen und Deutschmährer, i.e. German Bohemians and German Moravians), later known as Sudeten Germans, were ethnic Germans living in the Czech lands of the Bohemian Crown, which later became an integral part of ...

while issues of the Hungarian minority had secondary priority. The Hungarians in Slovakia felt aggrieved by the results of Czechoslovak land reform. Regardless of its social and democratizing character, redistribution of former aristocratic lands preferred the majority population, church, and great landowners.

Even if Czechoslovakia officially declared equality of all citizens, members of the Hungarian minority were reluctant to apply for positions in diplomacy, army or state services because of fear that they could be easily misused by foreign intelligence services, especially in time of threat to the country.

Lack of interest for better integration of Hungarian community, the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and political changes in Europe led to a rise of Hungarian nationalism, pushing their demands in cooperation with German Nazis and other enemies of the Czechoslovak state.

Preparation of aggression against Czechoslovakia

The United Hungarian Party (EMP) led by

János Esterházy

Count János Eszterházy (; rarely sk, Ján Esterházi; March 14, 1901 – March 8, 1957) was a prominent ethnic Hungarian politician in inter-war Czechoslovakia and later in the First Slovak Republic. He was a member of the Czechoslovak Parl ...

and

Andor Jaross played a

fifth column

A fifth column is any group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. According to Harris Mylonas and Scott Radnitz, "fifth columns" are “domestic actors who work to un ...

role during the disintegration of Czechoslovakia in late 1930s. Investigation of the

Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

proved that both Nazi Germany and Horthy Hungary used their minorities for internal disintegration of Czechoslovakia; their goal was not to achieve guarantees of their national rights, but to misuse the topic of national rights against the state whose citizens they were. According to international law, such behavior belongs to illegal activities against sovereignty of Czechoslovakia and activities of both countries were evaluated as an act against international peace and freedom.

Members of EMP helped to spread anti-Czechoslovak propaganda, while leaders preserved conspiratorial contacts with the Hungarian government and were informed about the preparation of Nazi aggression against Czechoslovakia. Particularly after

anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germa ...

of Austria, the party successfully eliminated various Hungarian activist groups.

In the ideal case, revisionist policy coordinated by the Hungarian government should lead to non-violent restoration of borders before the

Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles on 4 June 1920. It forma ...

– occupation of the whole Slovakia, or at least to partial territorial reversion. The EMP and Hungarian government had no interest in direct Nazi aggression without participation of Hungary, because it could result in Nazi occupation of Slovakia and jeopardize their territorial claims. The EMP copied policy of

Sudeten German Party to some extent. However, even in the time of Czechoslovak crisis, sharper political confrontations were avoided in the ethnically mixed territory. Esterházy was informed about the Sudeten German plan to sabotage negotiations with the Czechoslovak government, and after consultation with the Hungarian government he received instructions to work out on such program which could not be fulfilled.

After the

First Vienna Award Hungarians divided into two groups. The majority of the Hungarian population returned to Hungary (503,980 people) and the smaller part (about 67,000 people) remained on non-occupied territory of Czechoslovakia. The First Vienna Award did not satisfy ambitions of leading Hungarian circles and the support for a

Greater Hungary grew. This would lead to the annexation of the whole of Slovakia.

Annexation of Southern Slovakia and Subcarpathia (1938–1945)

Most of the Hungarians in Slovakia welcomed the

First Vienna Award and occupation of Southern Slovakia which were understood by them as unification of Hungarians into one common national state. Hungarians organized various celebrations and meetings. In

Ožďany

Ožďany ( hu, Osgyán) is a village and municipality in the Rimavská Sobota District of the Banská Bystrica Region of southern Slovakia.

Local high school played an important role in the Slovak history, some important persons of Slovak literary ...

(

Rimavská Sobota District) celebrations had a stormy course. Despite the fact that mass gathering without permit was prohibited and a 20:00 curfew was in place, approximately 400–500 Hungarians met at 21:30 after the announcement of the result of the "arbitration". Police patrols attempted to disperse crowd and one person suffered fatal injury. The mass gathering continued after 22:00 and police injured additional people by shooting and striking with rifles.

Hungary began a systematic assimilation and

magyarization

Magyarization ( , also ''Hungarization'', ''Hungarianization''; hu, magyarosítás), after "Magyar"—the Hungarian autonym—was an assimilation or acculturation process by which non-Hungarian nationals living in Austro-Hungarian Transleitha ...

policy and forced expulsion of colonists, state employees and Slovak Intelligence from the annexed territory. The Hungarian military administration banned the use of Slovak in administrative contacts and Slovak teachers had to leave schools at all levels.

Following extensive propaganda from the dictatorships – which pretended to be protectors of civic, social and minority rights in Czechoslovakia – Hungary restricted all minorities immediately after the Vienna Award. This had a negative impact on democratically oriented Hungarians in Slovakia, who were subsequently labeled as "Beneš Hungarians" or "communists" when they began to complain of the new conditions.

Mid-war propaganda organized by Hungary did not hesitate to promise "trains of food" for Hungarians (there was no starvation in Czechoslovakia), but after occupation it became clear that Czechoslovakia guaranteed more social rights, more advanced social systems, higher pensions and more job opportunities. Hungarian economists concluded in November 1938 that production on "returned lands" should be restricted to defend the economic interest of the mother country. Instead of positive development, a great majority of companies fell into conditions comparable to the economic crisis at the beginning of the 1930s. After some initial enthusiasm, slogans like ''Minden drága, visza Prága!'' (Everything is expensive, back to Prague!) or ''Minden drága, jobb volt Prága!'' (Everything is expensive, Prague was better) began to spread across the country.

Positions in the state administration vacated by Czechs and Slovaks were not occupied by local Hungarians, but by state employees from the mother country. This raised protests from the EMP and led to attempts to stop their incoming flow. In August 1939,

Andor Jaross asked the Hungarian prime minister to recall at least part of them back to Hungary. Due to different development in Czechoslovakia and Hungary during the previous 20 years, local Hungarians had more democratic spirit and came into conflict with the new administration known by its authoritarian arrogance. In November–December 1939, behavior toward Hungarians in the annexed territory escalated into official complaint of "

Felvidék" MPs in Hungarian parliament.

The Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–1939)

According to the December 1938 census, 67,502 Hungarians remained in the non-annexed part of Slovakia and 17,510 of them had Hungarian citizenship. Hungarians were represented by the Hungarian Party in Slovakia (SMP, Szlovenszkói Magyar Párt; this official name was adopted later in 1940) which formed after dissolution of United Hungarian Party (EMP) in November 1938. The political power in Slovakia was taken up by

Hlinka's Slovak People's Party (HSĽS) which started to realize its own totalitarian vision of the state. The ideology of HSĽS distinguished between "good" (autochthonous) minorities (Germans and Hungarians) and "bad" minorities (Czechs and Jews). The government did not allow political organization of "bad" minorities but tolerated existence of the SMP, whose leader

János Esterházy

Count János Eszterházy (; rarely sk, Ján Esterházi; March 14, 1901 – March 8, 1957) was a prominent ethnic Hungarian politician in inter-war Czechoslovakia and later in the First Slovak Republic. He was a member of the Czechoslovak Parl ...

became a member of the Slovak Diet. The SMP had little political influence and inclined to cooperation with the stronger German Party in Slovakia (Deutsche Partei in der Slowakei).

By November 1938, Esterházy raised additional demands for extension of Hungarian minority rights. The autonomous Slovak government evaluated the situation in the annexed territory, then did the opposite – binding Hungarian minority rights to the level provided by Hungary which ''de facto'' meant their reduction. The applied principle of

reciprocity blocked official registration of the SMP and the existence of several Hungarian institutions, as similar organizations were not permitted in Hungary. Moreover, the government banned usage of Hungarian national colors, singing the Hungarian national anthem, did not recognize equality of Hungarian national groups in Bratislava and cancelled a planned office of state secretary for Hungarian minority. The Hungarian government and Esterházy protested against the principle and criticized it as non-constructive.

The First Slovak Republic (1939–1945)

On 14 March 1939, the Slovak Diet declared independence under direct Hitler pressure and a proclaimed threat of Hungarian attack against Slovakia. Destruction of the plurality political system caused a fast decline of minority rights (the German minority preserved a privileged position). Tense relationships between Slovakia and Hungary after the Vienna Award were worsened by a Hungarian attack against Slovakia in March 1939. This aggression combined with violent incidents in the annexed territory caused large anti-Hungarian social mobilization and discrimination. Some of the persecutions were motivated by the reciprocity principle included in the constitution, but persecutions were caused also by Hungarian propaganda demanding occupation of Slovakia, distribution of pamphlets and other propagandist material, oral propaganda and other provocations. Intensive propaganda was used on both sides and led to several anti-Hungarian demonstrations. The harshest repressions included internment in the camp in

Ilava

Ilava (german: Illau, hu, Illava) is a town in the Trenčín Region, northwestern Slovakia.

Name

The name is of uncertain origin. The historic medieval names were ''Lewe'', ''Lewa'' (the same historic name as Levice), ''Lewa de cidca fluviom V ...

and deportations of dozens of Hungarians to Hungary. In June 1940, Slovakia and Hungary reached agreement and stopped deportations of their minorities.

The Hungarian Party did not completely abandon the idea of

Greater Hungary, but after stabilization of the state it focused on more-realistic goals. The party had tried to organize the Horthy guard in Bratislava and other towns, but these attempts were discovered and prevented by repressive forces. The party organized various cultural, social and educational activities. Its activities were carefully monitored and restricted because of unsuccessful attempts to establish Slovak political representation in Hungary. The Hungarian Party was officially registered after German diplomatic intervention in November 1941, which also resulted in the Hungarian government permitting the Party of Slovak National unity.

In 1940, after stabilization of the international position of the Slovak state, 53,128 people declared Hungarian nationality and 45,880 of them had Slovak state citizenship. Social structure of the Hungarian minority did not significantly differ from the majority population. 40% of Hungarians worked in agriculture, but there was also a class of rich traders and intelligentsia living in towns. Hungarians owned several important enterprises, especially in central Slovakia. In Bratislava, the Hungarian minority participated in the "aryanization" of Jewish property.

Slovakia preserved 40 Hungarian minority schools, but restricted high schools and did not allow the opening of any new schools. On 20 April 1939, the government banned the largest Hungarian cultural association, SzEMKE, which resulted in an overall decline of activities of the Hungarian minority. Activities of SzEMKE were restored when Hungary permitted the Slovak cultural organization Spolok svätého Vojtecha (St. Vojtech Society). The Hungarian minority had two daily newspapers (''Új Hírek'' and ''Esti Ujság'') and eight local weeklies. All journals, imported press and libraries were controlled by strong censorship.

After negotiations in Salzburg (27–28 July 1940),

Alexander Mach

Alexander Mach (11 October 1902 – 15 October 1980) was a Slovak nationalist politician. Mach was associated with the far right wing of Slovak nationalism and became noted for his strong support of Nazism and Germany.

Early years

Mach joined ...

held the position of Minister of the Interior and refined the state's approach to its Hungarian minority. Mach ordered all imprisoned Hungarian journalists to be released (later other Hungarians) and disposed chief editor of journal ''Slovenská pravda'' because of "stupid texts about Slovak-Hungarian question". Mach emphasized the need of Slovak–Hungarian cooperation and neighborly relations. In the following period, repressive actions were based almost exclusively on the reciprocity principle.

In comparison with the German minority, political rights and organization of the Hungarian minority was limited. On the other hand, measures against the Hungarian minority never reached the level of persecution against Jews and Gypsies. Expulsion from the country was applied exceptionally and in individual cases, contrary to the expulsion of Czechs.

The aftermath of World War II

In 1945, at the end of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Czechoslovakia was recreated. The strategic goal of the Czechoslovak government was to significantly reduce the size of German and Hungarian minorities and to achieve permanent change in ethnic composition of the state. The preferred means was population transfer. Due to the impossibility of unitary expulsion, Czechoslovakia applied three protocols –

Czechoslovak–Hungarian population exchange, "

re-Slovakization" and internal transfer of population realized during the

deportations of Hungarians to the Czech lands.

Many citizens considered both minorities to be "

war criminals", because representatives from those two minorities had supported redrawing the borders of Czechoslovakia before World War II, via the

Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

and the

first Vienna Award.

In addition, Czechs were suspicious of ethnic-German political activity before the war. They also believed that the presence of so many ethnic Germans had encouraged Nazi Germany in its pan-German visions. In 1945, President

Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš (; 28 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was a Czech politician and statesman who served as the president of Czechoslovakia from 1935 to 1938, and again from 1945 to 1948. He also led the Czechoslovak government-in-exile 1939 to 194 ...

revoked the citizenship of ethnic Germans and Hungarians by decree 33, except for those with an active anti-fascist past (see

Beneš Decrees

The Beneš decrees, sk, Dekréty prezidenta republiky) and the Constitutional Decrees of the President of the Republic ( cz, Ústavní dekrety presidenta republiky, sk, Ústavné dekréty prezidenta republiky) were a series of laws drafted by t ...

).

Population exchanges

Immediately at the end of World War II, some 30,000 Hungarians left the formerly Hungarian re-annexed territories of southern Slovakia. While Czechoslovakia expelled ethnic Germans, the Allies prevented a unilateral expulsion of Hungarians. They did agree to a forced population exchange between Czechoslovakia and Hungary, one which was initially rejected by Hungary. This population exchange proceeded by an agreement whereby 55,400 to 89,700 Hungarians from Slovakia were exchanged for 60,000 to 73,200 Slovaks from Hungary (the exact numbers depend on the source).

Slovaks leaving Hungary moved voluntarily, but Czechoslovakia forced Hungarians out of their nation.

After

expulsion of the Germans, Czechoslovakia found it had a labor shortage, especially of farmers in the

Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

. As a result, the Czechoslovak government deported more than 44,129 Hungarians from Slovakia to the Sudetenland for forced labor

between 1945 and 1948.

Some 2,489 were resettled voluntarily and received houses, good pay and citizenship in return. Later, from 19 November 1946 to 30 September 1946, the government resettled the remaining 41,666 by force, with the police and army transporting them like "livestock" in rail cars. The Hungarians were required to work as indentured laborers, often offered in village markets to the new Czech settlers of the Sudetenland.

These conditions eased slowly. After a few years, the resettled Hungarians started to return to their homes in Slovakia. By 1948, some 18,536 had returned, causing conflicts over the ownership of their original houses, since Slovak colonists had often taken them over. By 1950, the majority of indentured Hungarians had returned to Slovakia. The status of Hungarians in Czechoslovakia was resolved, and the government again gave citizenship to ethnic Hungarians.

Slovakization

Materials from Russian archives prove how insistent the Czechoslovak government was on destroying the Hungarian minority in Slovakia.

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

gave the Slovaks equal rights and demanded that Czechoslovakia offer equivalent rights to Hungarians within its borders.

In the spring and summer of 1945, the Czechoslovak government-in-exile approved a series of decrees that stripped Hungarians of property and all civil rights. In 1946 in Czechoslovakia, the process of "re-Slovakization" was implemented with the objective of eliminating the Magyar nationality.

It basically required the acceptance of Slovak nationality.

[ Ethnic Hungarians were pressured to have their nationality officially changed to Slovak, otherwise they were dropped from the ]pension

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

, social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

and healthcare system. Since Hungarians in Slovakia were temporarily deprived of many rights at that time (see Beneš decrees

The Beneš decrees, sk, Dekréty prezidenta republiky) and the Constitutional Decrees of the President of the Republic ( cz, Ústavní dekrety presidenta republiky, sk, Ústavné dekréty prezidenta republiky) were a series of laws drafted by t ...

), as many as some 400,000 (sources differ) Hungarians applied for, and 344,609 Hungarians received, a re-Slovakization certificate and thereby Czechoslovak citizenship.

After Eduard Beneš was out of office, the next Czechoslovak government issued decree No. 76/1948 on 13 April 1948, allowing those Hungarians still living in Czechoslovakia, to reinstate Czechoslovak citizenship.[ A year later, Hungarians were allowed to send their children to Hungarian-language schools, which reopened for the first time since 1945.][ Most re-Slovakized Hungarians gradually re-adopted their Hungarian nationality. As a result, the re-Slovakization commission ceased operations in December 1948.

Despite promises to settle the issue of the Hungarians in Slovakia, Czech and Slovak ruling circles in 1948 maintained the hope that they could deport the Hungarians from Slovakia. According to a 1948 poll conducted among the Slovak population, 55% were for resettlement (deportation) of the Hungarians, 24% said "don't know", and 21% were against. Under slogans related to the struggle with "class enemies", the process of dispersing dense Hungarian settlements continued in 1948 and 1949.][ Rieber, p. 93]

Population statistics after World War II

In the 1950 census, the number of Hungarians in Slovakia decreased by 240,000 in comparison to 1930. By the 1961 census it had increased by 164,244 to 518,776. The low number in the 1950 census is likely due to re-Slovakization and population exchanges; the higher number in the 1961 census is likely due to the cancellation of re-Slovakization and natural growth of population (in Slovakia population rose 21%, compared to 46% growth of Hungarians in Slovakia in the same period).

The number of Hungarians in Slovakia increased from 518,782 in 1961 to 567,296 in 1991. The number of self-identified Hungarians in Slovakia decreased between 1991 and 2001, due in part to low birth rates, emigration and introduction of new ethnic categories, such as the Roma. Also, between 1961 and 1991 Hungarians had a significantly lower birth rate than the Slovak majority (which in the meantime had increased from about 3.5 million to 4.5 million), contributing to the drop in the Hungarian percentage of the population.

In the 1950 census, the number of Hungarians in Slovakia decreased by 240,000 in comparison to 1930. By the 1961 census it had increased by 164,244 to 518,776. The low number in the 1950 census is likely due to re-Slovakization and population exchanges; the higher number in the 1961 census is likely due to the cancellation of re-Slovakization and natural growth of population (in Slovakia population rose 21%, compared to 46% growth of Hungarians in Slovakia in the same period).

The number of Hungarians in Slovakia increased from 518,782 in 1961 to 567,296 in 1991. The number of self-identified Hungarians in Slovakia decreased between 1991 and 2001, due in part to low birth rates, emigration and introduction of new ethnic categories, such as the Roma. Also, between 1961 and 1991 Hungarians had a significantly lower birth rate than the Slovak majority (which in the meantime had increased from about 3.5 million to 4.5 million), contributing to the drop in the Hungarian percentage of the population.

After the Fall of Communism

After the Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution ( cs, Sametová revoluce) or Gentle Revolution ( sk, Nežná revolúcia) was a non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from 17 November to 28 November 1989. Popular demonstrations agains ...

of 1989, the Czech Republic and Slovakia separated peacefully in the Velvet Divorce of 1993. The 1992 Slovak constitution is derived from the concept of the Slovak nation state.[Hungarian Nation in Slovakia, Slovakia](_blank)

. slovakia.org The preamble of the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

, however, cites Slovaks and ethnic minorities as the constituency. Moreover, the rights of the diverse minorities are protected by the Constitution, the European Convention on Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by ...

, and various other legally binding documents. The Party of the Hungarian Coalition (SMK-MKP) was represented in Parliament and was part of the government coalition from 1998 to 2006.

Following the independence of Slovakia, the situation of the Hungarian minority worsened, especially under the reign of Slovak Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar (1993 – March 1994 and December 1994 – 1998).

The Constitution also declared that Slovak is the state language. The 1995 Language Law declared that the state language has priority over other languages on the whole territory of the Slovak Republic. The 2009 amendment of the language law restricts the use of minority languages, and extends the obligatory use of the state language (e.g. in communities where the number of minority speakers is less than 20% of the population). Under the 2009 amendment a fine of up to 5000 euros may be imposed on those committing a misdemeanour in relation to the use of the state language.

An official language law required the use of Slovak not only in official communications but also in everyday commerce, in the administration of religious bodies, and even in the realm of what is normally considered private interaction, for example, communications between patient and physician. On 23 January 2007, the local broadcasting committee shut down BBC's radio broadcasting for using English, and cited the language law as the reason.

Especially in Slovakia's ethnic Hungarian areas,[O'Dwyer, Conor : ''Runaway State-building'', p. 11]

online

/ref> critics have attacked the administrative division of Slovakia as a case of gerrymandering

In representative democracies, gerrymandering (, originally ) is the political manipulation of electoral district boundaries with the intent to create undue advantage for a party, group, or socioeconomic class within the constituency. The m ...

, designed so that in all eight regions, Hungarians are in the minority. Under the 1996 law of reorganization, only two districts

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or counties, several municipalities, subdivisions ...

(Dunajská Streda

Dunajská Streda (; hu, Dunaszerdahely; german: Niedermarkt; he, דונהסרדהיי) is a town located in southern Slovakia ( Trnavský kraj). Dunajská Streda is the most culturally significant town in the Žitný ostrov area. The town has a p ...

and Komárno) have a Hungarian-majority population. While also done to maximize the success of the party Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS), the gerrymandering in ethnic Hungarian areas worked to minimize the Hungarians' voting power.Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; french: Conseil de l'Europe, ) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it has 46 member states, with a p ...

, which in its article 11 states:

After the regions of Slovakia

Since 1949 (except 1990–1996), Slovakia has been divided into a number of ''kraje'' (singular ''kraj''; usually translated as "Regions" with capital R). Their number, borders and functions have been changed several times. There are eight regio ...

became autonomous in 2002, the MKP was able to take power in the Nitra Region. It became part of the ruling coalition in several other regions. Since the new administrative system was put in place in 1996, the MKP has asked for the creation of a Hungarian-majority Komárno county. Although a territorial unit of the same name existed

Existence is the ability of an entity to interact with reality. In philosophy, it refers to the ontological property of being.

Etymology

The term ''existence'' comes from Old French ''existence'', from Medieval Latin ''existentia/exsisten ...

before 1918, the borders proposed by the MKP are significantly different. The proposed region would encompass a long slice of southern Slovakia, with the explicit aim to create an administrative unit with an ethnic-Hungarian majority. Hungarian-minority politicians and intellectuals are convinced that such an administrative unit is essential for the long-term survival of the Hungarian minority. The Slovak government has so far refused to change the boundaries of the administrative units, and ethnic Hungarians continue as minorities in each.

According to Sabrina P. Ramet

Sabrina Petra Ramet (born June 26, 1949) is an American academic, educator, editor and journalist. She specializes in Eastern European history and politics and is a Professor of Political Science at the Norwegian University of Science and Technol ...

, professor of international studies at the University of Washington (referring to the situation under Vladimír Mečiar's administration between 1994 and 1998):Ján Slota

Ján Slota (born 14 September 1953) is the co-founder and former president of the Slovak National Party,[nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...]

[New Slovak Government Embraces Ultra-Nationalists, Excludes Hungarian Coalition Party](_blank)

HRF Alert: "Hungarians are the cancer of the Slovak nation, without delay we need to remove them from the body of the nation." (Új Szó, 15 April 2005) right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this pos ...

extremist

Extremism is "the quality or state of being extreme" or "the advocacy of extreme measures or views". The term is primarily used in a political or religious sense to refer to an ideology that is considered (by the speaker or by some implied share ...

ethnic hatred

Ethnic hatred, inter-ethnic hatred, racial hatred, or ethnic tension refers to notions and acts of prejudice and hostility towards an ethnic group in varying degrees.

There are multiple origins for ethnic hatred and the resulting ethnic conflic ...

caused diplomatic tensions between Slovakia and Hungary. The mainstream media in these countries blamed Slota's anti-Hungarian statements from the early summer for the worsening ethnic relations. The Party of European Socialists

The Party of European Socialists (PES) is a social democratic and progressive European political party.

The PES comprises national-level political parties from all member states of the European Union (EU) plus Norway and the United Kingdom. ...

(PES), with which the Smer is affiliated, regards SNS as a party of the racist far-right and expressed grave concern regarding the coalition. The PES suspended Smer's membership on 12 October 2006 and decided to review the situation in June 2007. The decision was then extended until February 2008, when Smer's candidacy was readmitted by PES. On 27 September 2007, the Slovak parliament rejected both principle of collective guilt and attempts to reopen post-war documents which had established the current order.

On 10 April 2008, the Party of the Hungarian Community ( SMK-MKP) voted with the governing Smer and SNS, supporting the ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon

The Treaty of Lisbon (initially known as the Reform Treaty) is an international agreement that amends the two treaties which form the constitutional basis of the European Union (EU). The Treaty of Lisbon, which was signed by the EU member s ...

. This may have been the result of an alleged political bargain:[

] Robert Fico promised to change the Slovak education law that would have drastically limited the Hungarian minority's usage of Hungarian-language in educational facilities. The two Slovak opposition parties saw this as a betrayal,freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exerc ...

in Slovakia.

In May 2010, the newly appointed second Viktor Orbán

Viktor Mihály Orbán (; born 31 May 1963) is a Hungarian politician who has served as prime minister of Hungary since 2010, previously holding the office from 1998 to 2002. He has presided over Fidesz since 1993, with a brief break between ...

cabinet in Hungary initiated a bill on dual citizenship

Multiple/dual citizenship (or multiple/dual nationality) is a legal status in which a person is concurrently regarded as a national or citizen of more than one country under the laws of those countries. Conceptually, citizenship is focused on ...

, granting Hungarian passports to members of the Hungarian minority in Slovakia, purportedly aimed at offsetting the harmful effects of the Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles on 4 June 1920. It forma ...

. Though János Martonyi, the new Hungarian foreign minister, visited his Slovak colleague to discuss dual citizenship, Robert Fico stated that Fidesz

Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Alliance (; hu, Fidesz – Magyar Polgári Szövetség) is a right-wing populist and national-conservative political party in Hungary, led by Viktor Orbán.

It was formed in 1988 under the name of Alliance of Young ...

(Orbán's right-wing party) and the new government did not want to negotiate on the issue, considered a question of national security. Ján Slota's Slovak government member for the SNS feared that Hungary wanted to attack Slovakia and considered the situation as the "beginning of a war conflict". Designate Prime Minister Viktor Orbán

Viktor Mihály Orbán (; born 31 May 1963) is a Hungarian politician who has served as prime minister of Hungary since 2010, previously holding the office from 1998 to 2002. He has presided over Fidesz since 1993, with a brief break between ...

laid down firmly that he considered Slovak hysteria as part of the campaign. As a response to the change in Hungarian citizenship law, the National Council of the Slovak Republic

The National Council of the Slovak Republic ( sk, Národná rada Slovenskej republiky), abbreviated to ''NR SR'', is the national parliament of Slovakia. It is unicameral and consists of 150 members, who are elected by universal suffrage under ...

approved on 26 May 2010 a law stating that if a Slovak citizen applies for citizenship of another country, then that person will lose their Slovak citizenship.

Language law

On 1 September 2009, over 10,000 Hungarians held demonstrations to protest the new law that limited the use of minority languages in Slovakia. The law called for fines of up to £4,380 for institutions "misusing the Slovak language". There were demonstrations in Dunajská Streda

Dunajská Streda (; hu, Dunaszerdahely; german: Niedermarkt; he, דונהסרדהיי) is a town located in southern Slovakia ( Trnavský kraj). Dunajská Streda is the most culturally significant town in the Žitný ostrov area. The town has a p ...

( hu, Dunaszerdahely), Slovakia, in Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population o ...

, Hungary and in Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

.

Culture

* '' Új Szó'' – a Hungarian-language daily newspaper published in Bratislava

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approximately 140% of ...

* Madách – former Hungarian publishing house in Bratislava

* Kalligram – Hungarian publishing house in Bratislava

Education

585 schools in Slovakia, including kindergarten

Kindergarten is a preschool educational approach based on playing, singing, practical activities such as drawing, and social interaction as part of the transition from home to school. Such institutions were originally made in the late 18th cen ...

s, use Hungarian as the main language of education. Nearly 200 schools use both Slovak and Hungarian. In 2004, the J. Selye University of Komárno was the first state-financed Hungarian-language university to be opened outside of Hungary.

Hungarian political parties

* Under the First Republic of Czechoslovakia (1918–1938):

**Provincial Christian-Socialist Party

The Provincial Christian-Socialist Party ( hu, Országos Keresztényszocialista Párt, OKszP; cs, Zemská křesťansko-socialistická strana; german: Provinziell-Christlich-Sozialistische Partei) was the main political party of ethnic Hungarians ...

(Hungarian: Országos Keresztényszocialista Párt, OKSZP)

** Hungarian-German Social Democratic Party (German: Ungarisch-Deutsche Partei der Sozialdemokraten, Hungarian: Magyar és Német Szociál-Demokrata Párt)

**Hungarian National Party Hungarian National Party ( hu, Magyar Nemzeti Párt, MNP, cs, Maďarská národní strana, sk, Maďarská národná strana) was one of political parties of ethnic Hungarians in the First Republic of Czechoslovakia.

The party was founded in Febru ...

(Hungarian: Magyar Nemzeti Párt, MNP)

* Party of the Hungarian Community (Strana maďarskej koalície – ''Magyar Koalíció Pártja'') (SMK-MKP), in the government between 1998 and 2006.

* Most–Híd, in the government between 2010–2012 and 2016–2020.

* Hungarian Christian-Democratic Association (Maďarská kresťanskodemokratická aliancia – ''Magyar Kereszténydemokrata Szövetség'') (MKDA-MKDSZ)

* Alliance (Aliancia - ''Szövetség'')

Towns with large Hungarian populations (2001 and 2011 census)

Note: only towns in Slovakia are listed here, villages and rural municipalities are not.

Towns with a Hungarian majority

* Gabčíkovo

Gabčíkovo ( hu, Bős, ) is a town and municipality in the Dunajská Streda District, in the Trnava Region of southwestern Slovakia. It has 5,232 inhabitants of whom approximately 80% are Hungarians. After the Communist takeover of Czechoslovak ...

(Bős) – 5,361 inhabitants, of whom 90.4% (87.88%Štatistický úrad Slovenskej republiky

scitanie2011.sk. July 2012) are Hungarian

* Veľký Meder

Veľký Meder (1948–1990 ''Čalovo'', hu, Nagymegyer, yi, Magendorf) is a town in the Dunajská Streda District, Trnava Region in southwestern Slovakia.

Etymology

The name is derived from the name of the ancient Hungarian ''Megyer'' tribe.

...

(Nagymegyer) – 9,113 inhabitants, of whom 84.6% (75.58%) are Hungarian

* Kolárovo

Kolárovo (before 1948: ''Guta''; hu, Gúta or earlier ''Gutta'') is a town in the south of Slovakia near the town of Komárno. It is an agricultural center with 11,000 inhabitants.

Basic information

The town of Kolárovo is located in the Po ...

(Gúta) – 10,756 inhabitants, of whom 82.6% (76.67%) are Hungarian

* Dunajská Streda

Dunajská Streda (; hu, Dunaszerdahely; german: Niedermarkt; he, דונהסרדהיי) is a town located in southern Slovakia ( Trnavský kraj). Dunajská Streda is the most culturally significant town in the Žitný ostrov area. The town has a p ...

(Dunaszerdahely) – 23,562 inhabitants, of whom 79.75% (74.53%) are Hungarian

* Kráľovský Chlmec

Kráľovský Chlmec (; until 1948 ''Kráľovský Chlumec'', hu, Királyhelmec) is a town in the Trebišov District in the Košice Region of south-eastern Slovakia. It has a population of around 8,000.

Etymology

The name means "Royal Hill". Slov ...

(Királyhelmec) – 7,966 inhabitants, of whom 76.94% (73.66%) are Hungarian

* Štúrovo

Štúrovo (before 1948: ''Parkan''; hu, Párkány, german: Gockern, tr, Ciğerdelen) is a town in Slovakia, situated on the River Danube. Its population in 2018 was 10,279.

The town is situated opposite the Hungarian city of Esztergom. The Má ...

(Párkány) – 11,708 inhabitants, of whom 68.7% (60.66%) are Hungarian

* Šamorín (Somorja) – 12,339 inhabitants, of whom 66.63% (57.43%) are Hungarian

* Fiľakovo

Fiľakovo (; hu, Fülek, german: Fülleck, tr, Filek) is a town in the Banská Bystrica Region of south-central Slovakia. Historically it was located in Nógrád County, as part of the Nógrád, Novohrad, "Newcastle" region.

Geography

It is lo ...

(Fülek) – 10,198 inhabitants, of whom 64.40% (53.54%) are Hungarian

* Šahy (Ipolyság) – 7,971 inhabitants, of whom 62.21% (57.84%) are Hungarian

* Tornaľa (Tornalja) – 8,016 inhabitants, of whom 62.14% (57.68%) are Hungarian

* Komárno (Komárom) – 37,366 inhabitants, of whom 60.09% (53.88%) are Hungarian

* Čierna nad Tisou (Tiszacsernyő) – 4,390 inhabitants, of whom 60% (62.27%) are Hungarian

* Veľké Kapušany (Nagykapos) – 9,536 inhabitants of whom 56.98% (59.58%) are Hungarian

Towns with a Hungarian population of between 25% and 50%

* Želiezovce (Zselíz) – 7,522 inhabitants, of whom 51.24% (48.72%) are Hungarian

* Hurbanovo

Hurbanovo (until 1948 ''Stará Ďala'', hu, Ógyalla, german: Altdala) is a town and large municipality in the Komárno District in the Nitra Region of south-west Slovakia. In 1948, its Slovak name was changed to Hurbanovo, named after Slovak wr ...

(Ógyalla) – 8,041 inhabitants, of whom 50.19% (41.23%) are Hungarian

* Moldava nad Bodvou

Moldava nad Bodvou ( hu, Szepsi; german: Moldau (an der Bodwa)) is a town and municipality in Košice-okolie District in the Košice Region of eastern Slovakia.

History

In historical records the town was first mentioned in 1255.

Geography

The t ...

(Szepsi) – 9,525 inhabitants of whom 43.6% (29.63%) are Hungarian

* Sládkovičovo (Diószeg) – 6,078 inhabitants of whom 38.5% (31.70%) are Hungarian

* Galanta

Galanta ( hu, Galánta, german: Gallandau) is a town (about 15,000 inhabitants) in the Trnava Region of Slovakia. It is situated 50 km due east of the Slovak capital Bratislava.

Etymology

The name is derived from a Slavic name ''Golęta'' ( ...

(Galánta) – 16,000 inhabitants of whom 36.80% (30.54%) are Hungarian

* Rimavská Sobota

Rimavská Sobota (; hu, Rimaszombat, german: Großsteffelsdorf) is a town in southern Slovakia, in the Banská Bystrica Region, on the Rimava river. It has approximately 24,000 inhabitants. The town is a historical capital of Gömör és Kishont ...

(Rimaszombat) – 24,520 inhabitants of whom 35.26% (29.62%) are Hungarian

Towns with a Hungarian population of between 10% and 25%

* Nové Zámky (Érsekújvár) – 42,300 inhabitants of whom 27.52% (22.36%) are Hungarian

* Rožňava

Rožňava ( hu, Rozsnyó, german: Rosenau, Latin: ''Rosnavia'') is a town in Slovakia, approximately by road from Košice in the Košice Region, and has a population of 19,182.

The town is an economic and tourist centre of the Gemer. Rožň ...

(Rozsnyó) – 19,120 inhabitants of whom 26.8% (19.84%) are Hungarian

* Senec (Szenc) – 15,193 inhabitants of whom 22% (14.47%) are Hungarian

* Šaľa (Vágsellye) – 24,506 inhabitants of whom 17.9% (14.15%) are Hungarian

* Lučenec (Losonc) – 28,221 inhabitants of whom 13.11% (9.34%) are Hungarian

* Levice

Levice (; hu, Léva, Hungarian pronunciation: ; german: Lewenz, literally lionesses) is a town in western Slovakia. The town lies on the left bank of the lower Hron river. The Old Slavic name of the town was ''Leva'', which means "the Left On ...

(Léva) – 35,980 inhabitants of whom 12.23% (9.19%) are Hungarian

Notable Hungarians born in the area of present-day Slovakia

Born before 1918 in the Kingdom of Hungary

* Gyula Andrássy

Count Gyula Andrássy de Csíkszentkirály et Krasznahorka (8 March 1823 – 18 February 1890) was a Hungarian statesman, who served as Prime Minister of Hungary (1867–1871) and subsequently as Foreign Minister of Austria-Hungary (1871– ...

(politician)

* Gyula Andrássy the Younger

Count Gyula Andrássy de Csíkszentkirály et Krasznahorka the Younger ( hu, Ifj. Andrássy Gyula; 30 June 1860 – 11 June 1929) was a Hungarian politician.

Biography

The second son of Count Gyula Andrássy and Countess Katinka Kendeffy, th ...

(politician)

* Bálint Balassi (poet)

* Lajos Batthyány (politician)

* Miklós Bercsényi (politician, military leader)

* Lujza Blaha (actress, "the nightingale of the nation")

* Ernő Dohnányi (conductor, composer, pianist)

* Elizabeth of Hungary

* Béla Gerster (engineer, canal architect)

* Artúr Görgey (military leader)

* András Hadik

* Béla Hamvas

Béla Hamvas (23 March 1897 – 7 November 1968) was a Hungarian writer, philosopher, and social critic. He was the first thinker to introduce the Traditionalist School of René Guénon to Hungary.

Biography

Béla Hamvas was born on 23 Marc ...

(philosopher)

* Mór Jókai (writer)

* Lajos Kassák (poet, painter, typographer, graphic artist)

* Domokos Kosáry

Domokos Kosáry ( �domokoʃ ˈkoʃaːri 31 July 1913 – 15 November 2007) was a Hungarian historian and writer who served as president of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences from 1990 until 1996.

Biography

Kosáry was born in Selmecbánya (Ban ...

(historian, president of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences)

* Peter Lorre

Peter Lorre (; born László Löwenstein, ; June 26, 1904 – March 23, 1964) was a Hungarian and American actor, first in Europe and later in the United States. He began his stage career in Vienna, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, before movin ...

(Hollywood actor)

* Imre Madách

Imre Madách de Sztregova et Kelecsény (20 January 1823 – 5 October 1864) was a Hungarian aristocrat, writer, poet, lawyer and politician. His major work is ''The Tragedy of Man'' (''Az ember tragédiája'', 1861). It is a dramatic poem app ...

(poet)

* Pál Maléter

Pál Maléter (4 September 1917 – 16 June 1958) was the military leader of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.

Maléter was born to Hungarian parents in Eperjes, a city in Sáros County, in the northern part of Historical Hungary, today Prešov ...

(military leader of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution)

* Sándor Márai (writer)

* Kálmán Mikszáth (writer)

* Francis II Rákóczi

Francis II Rákóczi ( hu, II. Rákóczi Ferenc, ; 27 March 1676 – 8 April 1735) was a Hungarian nobleman and leader of Rákóczi's War of Independence against the Habsburgs in 1703–11 as the prince ( hu, fejedelem) of the Estates Confedera ...

(prince, military leader, freedom fighter)

* József Révay (philosopher, Olympic champion)

* Gyula Reviczky (poet)

* Franz Schmidt (composer)

* Mihály Tompa (poet)

* Imre Thököly (prince, military leader)

* János Zsámboky (16th-century humanist)

Born after 1918 in Czechoslovakia

* Balázs Borbély (sportsman)

* Imrich Bugár

Imrich Bugár ( hu, Bugár Imre, born 14 April 1955) is a Czechoslovak discus thrower. An ethnic Hungarian who represented Czechoslovakia and then the Czech Republic, his career highlights include an Olympic silver medal from 1980, a European ...

''Imre Bugár'' (sportsman)

* George Feher

George Feher (29 May 1924 – 28 November 2017) was an American biophysicist working at the University of California San Diego.

Birth and education

George Feher was born in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia in 1924.

Fehér is a hungarian name and hi ...

''György Fehér'' (biophysicist)

* Koloman Gögh ''Kálmán Gögh'' (sportsman)

* László Mécs ( Družstevná pri Hornáde, Slovakia; poet)

* Szilárd Németh (sportsman)

* Attila Pinte

Attila Pinte (born 6 June 1971) is a former Slovak football player of Hungarian ethnicity who currently cooperating as an assistant manager for ŠK SFM Senec.

Pinte played in Slovakia most notably for DAC Dunajská Streda and Inter Bratislava ...

(sportsman)

* Alexander Pituk ''Sándor Pituk'' (sportsman)

* Tamás Priskin (sportsman)

* Richard Réti

Richard Selig Réti (28 May 1889 – 6 June 1929) was an Austro-Hungarian, later Czechoslovakian, chess player, chess author, and composer of endgame studies.

He was one of the principal proponents of hypermodernism in chess. With the ex ...

(sportsman)

* Attila Végh

Attila Végh (born August 9, 1985) is a Slovak mixed martial artist who competed in the Light Heavyweight divisions of Bellator Fighting Championships and Konfrontacja Sztuk Walki (KSW). He won the Bellator 2012 Summer Series Light Heavyweigh ...

(sportsman)

Born in Czechoslovakia, career in Hungary

* Attila Kaszás

* János Manga

* Katalin Szvorák

* Alexandra Borbély (actress)

* Kerekes Vica (actress)

Hungarian politicians in Slovakia

* József Berényi – chairman of Party of the Hungarian Coalition

* Edit Bauer

Edit Bauer (born 30 August 1946 in (Somorja Šamorín)

is a Slovak politician of Hungarian ethnicity and

Member of the European Parliament (MEP).

Life

She is a member of the Magyar Koalíció Pártja,

part of the European People's Party and sh ...

– Member of the European Parliament

A Member of the European Parliament (MEP) is a person who has been elected to serve as a popular representative in the European Parliament.

When the European Parliament (then known as the Common Assembly of the ECSC) first met in 1952, its ...

* Béla Bugár – former chairman of Party of the Hungarian Coalition

* Pál Csáky – former chairman of Party of the Hungarian Coalition

* Miklós Duray

* Count János Esterházy

Count János Eszterházy (; rarely sk, Ján Esterházi; March 14, 1901 – March 8, 1957) was a prominent ethnic Hungarian politician in inter-war Czechoslovakia and later in the First Slovak Republic. He was a member of the Czechoslovak Parl ...

– World War II politician

* László Gyurovszky

* László Nagy

* Károly Tóth – leader of the Forum institute, which compiles statistics on minorities in Slovakia

See also

* 2006 Slovak–Hungarian diplomatic affairs

* Csángó

* Demographics of Slovakia

This article is about the demographic features of the population of Slovakia, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population. The demo ...

* Forum Minority Research Institute

The Forum Minority Research Institute or Forum Institute (''Fórum Kisebbségkutató Intézet'' or ''Fórum Intézet'' in Hungarian and ''Fórum inštitút pre výskum menšín'' or ''Fórum inštitút'' in Slovak) is a Slovak think tank with i ...

* Hungarian minority in Romania

* Hungarians in Vojvodina

* Hungary–Slovakia relations

* Magyarization

Magyarization ( , also ''Hungarization'', ''Hungarianization''; hu, magyarosítás), after "Magyar"—the Hungarian autonym—was an assimilation or acculturation process by which non-Hungarian nationals living in Austro-Hungarian Transleitha ...

* Slovakization

* Székelys

The Székelys (, Székely runes: 𐳥𐳋𐳓𐳉𐳗), also referred to as Szeklers,; ro, secui; german: Szekler; la, Siculi; sr, Секељи, Sekelji; sk, Sikuli are a Hungarian subgroup living mostly in the Székely Land in Romania. ...

* Székelys of Bukovina

* Ethnic minorities in Czechoslovakia

This article describes ethnic minorities in Czechoslovakia from 1918 until 1992.

Background

Czechoslovakia was founded as a country in the aftermath of World War I with its borders set out in the Treaty of Trianon and Treaty of Versailles, ...

* Magyaron

Magyaron also Magyarons ( uk, Мадярони, be, Мадзяроны, sk, Maďarón, russian: Мадяроны, rue, Мадяроны, pl, Madziaroni) is the name of a Transcarpathian ethno-cultural group, which has an openly Hungarian ...

References

Notes

Bibliography

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

*

*

*

External links

Hungarian population in present-day Slovakia (1880–1991)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hungarians In Slovakia

Slovakia