Hugo Steinhaus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hugo Dyonizy Steinhaus ( ; ; January 14, 1887 – February 25, 1972) was a

In September 1939 after

In September 1939 after

In the last days of World War II Steinhaus, still in hiding, heard a rumor that University of Lwów was to be transferred to the city of Breslau (

In the last days of World War II Steinhaus, still in hiding, heard a rumor that University of Lwów was to be transferred to the city of Breslau (

Hugo Steinhaus

in

Hugo Steinhaus

in

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

and educator

A teacher, also called a schoolteacher or formally an educator, is a person who helps students to acquire knowledge, competence, or virtue, via the practice of teaching.

''Informally'' the role of teacher may be taken on by anyone (e.g. whe ...

. Steinhaus obtained his PhD under David Hilbert

David Hilbert (; ; 23 January 1862 – 14 February 1943) was a German mathematician, one of the most influential mathematicians of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Hilbert discovered and developed a broad range of fundamental ideas in many a ...

at Göttingen University

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the capital of the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, the population was 118,911.

General information

The o ...

in 1911 and later became a professor at the Jan Kazimierz University

The University of Lviv ( uk, Львівський університет, Lvivskyi universytet; pl, Uniwersytet Lwowski; german: Universität Lemberg, briefly known as the ''Theresianum'' in the early 19th century), presently the Ivan Franko Na ...

in Lwów (now Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukraine ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

), where he helped establish what later became known as the Lwów School of Mathematics

The Lwów school of mathematics ( pl, lwowska szkoła matematyczna) was a group of Polish mathematicians who worked in the interwar period in Lwów, Poland (since 1945 Lviv, Ukraine). The mathematicians often met at the famous Scottish Café to ...

. He is credited with "discovering" mathematician Stefan Banach

Stefan Banach ( ; 30 March 1892 – 31 August 1945) was a Polish mathematician who is generally considered one of the 20th century's most important and influential mathematicians. He was the founder of modern functional analysis, and an origina ...

, with whom he gave a notable contribution to functional analysis

Functional analysis is a branch of mathematical analysis, the core of which is formed by the study of vector spaces endowed with some kind of limit-related structure (e.g. Inner product space#Definition, inner product, Norm (mathematics)#Defini ...

through the Banach–Steinhaus theorem

In mathematics, the uniform boundedness principle or Banach–Steinhaus theorem is one of the fundamental results in functional analysis.

Together with the Hahn–Banach theorem and the open mapping theorem, it is considered one of the cornerst ...

. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

Steinhaus played an important part in the establishment of the mathematics department at Wrocław University

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, ro ...

and in the revival of Polish mathematics from the destruction of the war.

Author of around 170 scientific articles and books, Steinhaus has left his legacy and contribution in many branches of mathematics, such as functional analysis, geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

, mathematical logic

Mathematical logic is the study of logic, formal logic within mathematics. Major subareas include model theory, proof theory, set theory, and recursion theory. Research in mathematical logic commonly addresses the mathematical properties of for ...

, and trigonometry

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics that studies relationships between side lengths and angles of triangles. The field emerged in the Hellenistic world during the 3rd century BC from applications of geometry to astronomical studies. T ...

. Notably he is regarded as one of the early founders of game theory

Game theory is the study of mathematical models of strategic interactions among rational agents. Myerson, Roger B. (1991). ''Game Theory: Analysis of Conflict,'' Harvard University Press, p.&nbs1 Chapter-preview links, ppvii–xi It has appli ...

and probability theory

Probability theory is the branch of mathematics concerned with probability. Although there are several different probability interpretations, probability theory treats the concept in a rigorous mathematical manner by expressing it through a set o ...

which led to later development of more comprehensive approaches by other scholars.

Early life and studies

Steinhaus was born on January 14, 1887, inJasło

Jasło is a county town in south-eastern Poland with 36,641 inhabitants, as of 31 December 2012. It is situated in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship (since 1999), and it was previously part of Krosno Voivodeship (1975–1998). It is located in Lesse ...

, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

to a family with Jewish roots. His father, Bogusław, was a local industrialist, owner of a brick factory and a merchant. His mother was Ewelina, née Lipschitz. Hugo's uncle, Ignacy Steinhaus, was a lawyer and an activist in the ''Koło Polskie'' (Polish Circle), and a deputy to the Galician Diet, the regional assembly

Assembly may refer to:

Organisations and meetings

* Deliberative assembly, a gathering of members who use parliamentary procedure for making decisions

* General assembly, an official meeting of the members of an organization or of their representa ...

of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria,, ; pl, Królestwo Galicji i Lodomerii, ; uk, Королівство Галичини та Володимирії, Korolivstvo Halychyny ta Volodymyrii; la, Rēgnum Galiciae et Lodomeriae also known as ...

.

Hugo finished his studies at the gymnasium in Jasło in 1905. His family wanted him to become an engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the l ...

but he was drawn to abstract mathematics and began to study the works of famous contemporary mathematicians on his own. In the same year he began studying philosophy and mathematics at the University of Lemberg

The University of Lviv ( uk, Львівський університет, Lvivskyi universytet; pl, Uniwersytet Lwowski; german: Universität Lemberg, briefly known as the ''Theresianum'' in the early 19th century), presently the Ivan Franko Na ...

. In 1906 he transferred to Göttingen University

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the capital of the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, the population was 118,911.

General information

The o ...

. At that University he received his Ph.D. in 1911, having written his doctoral dissertation under the supervision of David Hilbert

David Hilbert (; ; 23 January 1862 – 14 February 1943) was a German mathematician, one of the most influential mathematicians of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Hilbert discovered and developed a broad range of fundamental ideas in many a ...

. The title of his thesis was ''Neue Anwendungen des Dirichlet'schen Prinzips'' ("New applications to Dirichlet's principle

In mathematics, and particularly in potential theory, Dirichlet's principle is the assumption that the minimizer of a certain energy functional is a solution to Poisson's equation.

Formal statement

Dirichlet's principle states that, if the functi ...

").

At the start of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

Steinhaus returned to Poland and served in Józef Piłsudski

), Vilna Governorate, Russian Empire (now Lithuania)

, death_date =

, death_place = Warsaw, Poland

, constituency =

, party = None (formerly PPS)

, spouse =

, children = Wan ...

's Polish Legion, after which he lived in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

.

He was an atheist.

Academic career

Interwar Poland

During the 1916-1917 period and before Poland had regained its fullindependence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

, which occurred in 1918, Steinhaus worked in Kraków for the Ministry of the Interior

An interior ministry (sometimes called a ministry of internal affairs or ministry of home affairs) is a government department that is responsible for internal affairs.

Lists of current ministries of internal affairs

Named "ministry"

* Ministry ...

in the ephemeral puppet state of Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Królestwo Polskie; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a state in Central Europe. It may refer to:

Historical political entities

*Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom existing from 1025 to 1031

*Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom exist ...

.

In 1917 he started to work at the University of Lemberg

The University of Lviv ( uk, Львівський університет, Lvivskyi universytet; pl, Uniwersytet Lwowski; german: Universität Lemberg, briefly known as the ''Theresianum'' in the early 19th century), presently the Ivan Franko Na ...

(later ''Jan Kazimierz University

The University of Lviv ( uk, Львівський університет, Lvivskyi universytet; pl, Uniwersytet Lwowski; german: Universität Lemberg, briefly known as the ''Theresianum'' in the early 19th century), presently the Ivan Franko Na ...

'' in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

) and acquired his habilitation

Habilitation is the highest university degree, or the procedure by which it is achieved, in many European countries. The candidate fulfills a university's set criteria of excellence in research, teaching and further education, usually including a ...

qualification in 1920. In 1921 he became a ''profesor nadzwyczajny'' (associate professor

Associate professor is an academic title with two principal meanings: in the North American system and that of the ''Commonwealth system''.

Overview

In the ''North American system'', used in the United States and many other countries, it is a ...

) and in 1925 ''profesor zwyczajny'' (full professor) at the same university. During this time he taught a course on the then cutting edge theory of Lebesgue integration

In mathematics, the integral of a non-negative function of a single variable can be regarded, in the simplest case, as the area between the graph of that function and the -axis. The Lebesgue integral, named after French mathematician Henri Leb ...

, one of the first such courses offered outside of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

.

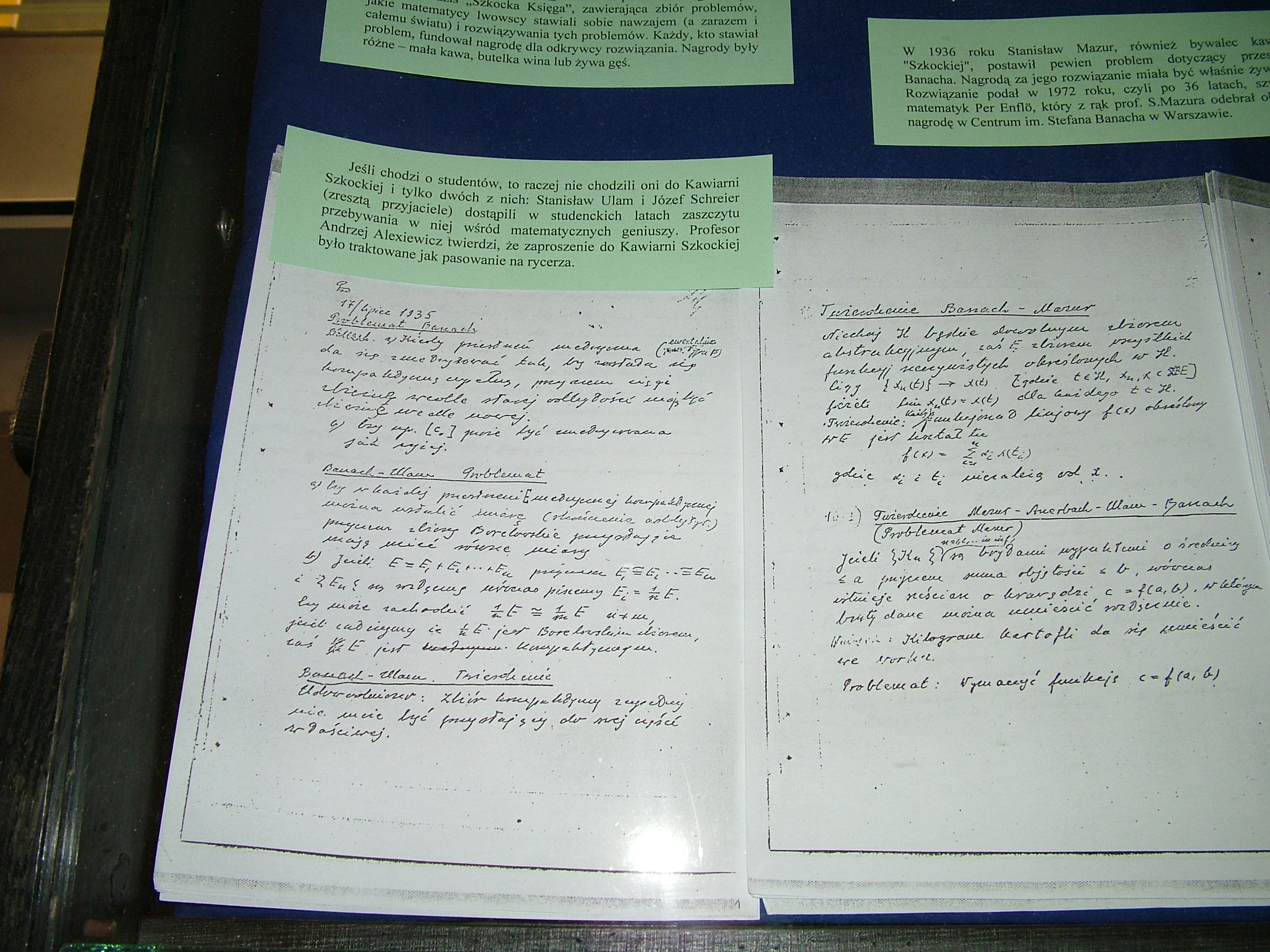

While in Lwów, Steinhaus co-founded the Lwów School of Mathematics

The Lwów school of mathematics ( pl, lwowska szkoła matematyczna) was a group of Polish mathematicians who worked in the interwar period in Lwów, Poland (since 1945 Lviv, Ukraine). The mathematicians often met at the famous Scottish Café to ...

and was active in the circle of mathematicians associated with the Scottish cafe, although, according to Stanislaw Ulam

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American scientist in the fields of mathematics and nuclear physics. He participated in the Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapon ...

, for the circle's gatherings, Steinhaus would have generally preferred a more upscale tea shop down the street.

World War II

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

both invaded and occupied Poland, as a fulfillment of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

they had signed earlier, Lwów initially came under Soviet occupation. Steinhaus considered escaping to Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

but ultimately decided to remain in Lwów. The Soviets reorganized the university to give it a more Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

character, but they did appoint Stefan Banach

Stefan Banach ( ; 30 March 1892 – 31 August 1945) was a Polish mathematician who is generally considered one of the 20th century's most important and influential mathematicians. He was the founder of modern functional analysis, and an origina ...

(Steinhaus's student) as the dean of the mathematics department and Steinhaus resumed teaching there. The faculty of the department at the school were also strengthened by several Polish refugees from German-occupied Poland. According to Steinhaus, during the experience of this period, he "acquired an insurmountable physical disgust in regard to all sorts of Soviet administrators, politicians and commissars"

During the interwar period and the time of the Soviet occupation, Steinhaus contributed ten problems to the famous '' Scottish Book'', including the last one, recorded shortly before Lwów was captured by the Nazis in 1941, during Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

.

Steinhaus, because of his Jewish background, spent the Nazi occupation

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 ...

in hiding, first among friends in Lwów, then in the small towns of Osiczyna, near Zamość

Zamość (; yi, זאמאשטש, Zamoshtsh; la, Zamoscia) is a historical city in southeastern Poland. It is situated in the southern part of Lublin Voivodeship, about from Lublin, from Warsaw. In 2021, the population of Zamość was 62,021.

...

and Berdechów

Berdechów is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Bobowa, within Gorlice County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, in southern Poland. It lies approximately north of Bobowa, north-west of Gorlice, and south-east of the regional capital ...

, near Kraków. The Polish anti-Nazi resistance provided him with false documents of a forest ranger who had died sometime earlier, by the name of Grzegorz Krochmalny. Under this name he taught clandestine classes (higher education was forbidden for Poles under the German occupation). Worried about the possibility of imminent death if captured by Germans, Steinhaus, without access to any scholarly material, reconstructed from memory and recorded all the mathematics he knew, in addition to writing other voluminous memoirs, of which only a little part has been published.

Also while in hiding, and cut off from reliable news on the course of the war, Steinhaus devised a statistical means of estimating for himself the German casualties at the front based on sporadic obituaries published in the local press. The method relied on the relative frequency with which the obituaries stated that the soldier who died was someone's son, someone's "second son", someone's "third son" and so on.

According to his student and biographer, Mark Kac

Mark Kac ( ; Polish: ''Marek Kac''; August 3, 1914 – October 26, 1984) was a Polish American mathematician. His main interest was probability theory. His question, " Can one hear the shape of a drum?" set off research into spectral theory, the ...

, Steinhaus told him that the happiest day of his life were the twenty four hours between the time that the Germans left occupied Poland and the Soviets had not yet arrived ("They had left, and they had not yet come").

After World War II

Wrocław

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, rou ...

), which Poland was to acquire as a result of the Potsdam Agreement (Lwów became part of Soviet Ukraine). Although initially he had doubts, he turned down offers for faculty positions in Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of canti ...

and Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of t ...

and made his way to the city where he began teaching at University of Wrocław

, ''Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Breslau'' (before 1945)

, free_label = Specialty programs

, free =

, colors = Blue

, website uni.wroc.pl

The University of Wrocław ( pl, Uniwersytet Wrocławski, U ...

. While there, he revived the idea behind the ''Scottish Book'' from Lwów, where prominent and aspiring mathematicians would write down problems of interest along with prizes to be awarded for their solution, by starting the '' New Scottish Book''. It was also most likely Steinhaus who preserved the original ''Scottish Book'' from Lwów throughout the war and subsequently sent it to Stanisław Ulam, who translated it into English.

With Steinhaus' help, Wrocław University became renowned for mathematics, much as the University of Lwów had been.

Later, in the 1960s, Steinhaus served as a visiting professor at the University of Notre Dame

The University of Notre Dame du Lac, known simply as Notre Dame ( ) or ND, is a private Catholic research university in Notre Dame, Indiana, outside the city of South Bend. French priest Edward Sorin founded the school in 1842. The main campu ...

(1961–62) and the University of Sussex

, mottoeng = Be Still and Know

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £14.4 million (2020)

, budget = £319.6 million (2019–20)

, chancellor = Sanjeev Bhaskar

, vice_chancellor = Sasha Roseneil

, ...

(1966).

Mathematical contributions

Steinhaus authored over 170 works. Unlike his student, Stefan Banach, who tended to specialize narrowly in the field offunctional analysis

Functional analysis is a branch of mathematical analysis, the core of which is formed by the study of vector spaces endowed with some kind of limit-related structure (e.g. Inner product space#Definition, inner product, Norm (mathematics)#Defini ...

, Steinhaus made contributions to a wide range of mathematical sub-disciplines, including geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

, probability theory

Probability theory is the branch of mathematics concerned with probability. Although there are several different probability interpretations, probability theory treats the concept in a rigorous mathematical manner by expressing it through a set o ...

, functional analysis, theory of trigonometric

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics that studies relationships between side lengths and angles of triangles. The field emerged in the Hellenistic world during the 3rd century BC from applications of geometry to astronomical studies. ...

and Fourier series

A Fourier series () is a summation of harmonically related sinusoidal functions, also known as components or harmonics. The result of the summation is a periodic function whose functional form is determined by the choices of cycle length (or ''p ...

as well as mathematical logic

Mathematical logic is the study of logic, formal logic within mathematics. Major subareas include model theory, proof theory, set theory, and recursion theory. Research in mathematical logic commonly addresses the mathematical properties of for ...

. He also wrote in the area of applied mathematics

Applied mathematics is the application of mathematical methods by different fields such as physics, engineering, medicine, biology, finance, business, computer science, and industry. Thus, applied mathematics is a combination of mathematical s ...

and enthusiastically collaborated with engineers

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the limit ...

, geologists

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

, economists

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this field there are ...

, physicians

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

, biologists

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual cell, a multicellular organism, or a community of interacting populations. They usually specialize in ...

and, in Kac's words, "even lawyers

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solicitor, ...

".

Probably his most notable contribution to functional analysis

Functional analysis is a branch of mathematical analysis, the core of which is formed by the study of vector spaces endowed with some kind of limit-related structure (e.g. Inner product space#Definition, inner product, Norm (mathematics)#Defini ...

was the 1927 proof of the Banach–Steinhaus theorem

In mathematics, the uniform boundedness principle or Banach–Steinhaus theorem is one of the fundamental results in functional analysis.

Together with the Hahn–Banach theorem and the open mapping theorem, it is considered one of the cornerst ...

, given along with Stefan Banach, which is now one of the fundamental tools in this branch of mathematics.

His interest in game

A game is a structured form of play (activity), play, usually undertaken for enjoyment, entertainment or fun, and sometimes used as an educational tool. Many games are also considered to be work (such as professional players of spectator s ...

s led him to propose an early formal definition of a strategy

Strategy (from Greek στρατηγία ''stratēgia'', "art of troop leader; office of general, command, generalship") is a general plan to achieve one or more long-term or overall goals under conditions of uncertainty. In the sense of the "art ...

, anticipating John von Neumann

John von Neumann (; hu, Neumann János Lajos, ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He was regarded as having perhaps the widest cove ...

's more complete treatment of a few years later. Consequently, he is considered an early founder of modern game theory

Game theory is the study of mathematical models of strategic interactions among rational agents. Myerson, Roger B. (1991). ''Game Theory: Analysis of Conflict,'' Harvard University Press, p.&nbs1 Chapter-preview links, ppvii–xi It has appli ...

. As a result of his work on infinite games Steinhaus, together with another of his students, Jan Mycielski

Jan Mycielski (born February 7, 1932 in Wiśniowa, Podkarpackie Voivodeship, Poland)Curriculum vitae

from ...

, proposed the from ...

axiom of determinacy

In mathematics, the axiom of determinacy (abbreviated as AD) is a possible axiom for set theory introduced by Jan Mycielski and Hugo Steinhaus in 1962. It refers to certain two-person topological games of length ω. AD states that every game of ...

.

Steinhaus was also an early contributor to, and co-founder of, probability theory, which at the time was in its infancy and not even considered an actual part of mathematics. He provided the first axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or f ...

atic measure-theoretic description of coin-tossing, which was to influence the full axiomatization of probability by the Russian mathematician Andrey Kolmogorov

Andrey Nikolaevich Kolmogorov ( rus, Андре́й Никола́евич Колмого́ров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ kəlmɐˈɡorəf, a=Ru-Andrey Nikolaevich Kolmogorov.ogg, 25 April 1903 – 20 October 1987) was a Sovi ...

a decade later. Steinhaus was also the first to offer precise definitions of what it means for two events to be "independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

", as well as for what it means for a random variable

A random variable (also called random quantity, aleatory variable, or stochastic variable) is a mathematical formalization of a quantity or object which depends on random events. It is a mapping or a function from possible outcomes (e.g., the po ...

to be " uniformly distributed".

While in hiding during World War II, Steinhaus worked on the fair cake-cutting problem: how to divide a heterogeneous resource among several people with different preferences such that every person believes he received a proportional share. Steinhaus' work has initiated the modern research of the fair cake-cutting

Fair cake-cutting is a kind of fair division problem. The problem involves a ''heterogeneous'' resource, such as a cake with different toppings, that is assumed to be ''divisible'' – it is possible to cut arbitrarily small pieces of it without ...

problem.

Steinhaus was also the first person to conjecture the ham-sandwich theorem, and one of the first to propose the method of ''k''-means clustering.

Legacy

Steinhaus is said to have "discovered" the Polish mathematician Stefan Banach in 1916, after he overheard someone utter the words "Lebesgue integral

In mathematics, the integral of a non-negative function of a single variable can be regarded, in the simplest case, as the area between the graph of that function and the -axis. The Lebesgue integral, named after French mathematician Henri Lebe ...

" while in a Kraków park (Steinhaus referred to Banach as his "greatest mathematical discovery"). Together with Banach and the other participant of the park discussion, Otto Nikodym

Otto Marcin Nikodym (3 August 1887 – 4 May 1974) (also Otton Martin Nikodým) was a Polish mathematician.

Education and career

Nikodym studied mathematics at the University of Jan Kazimierz (UJK) in Lvov (today's University of Lviv). Imm ...

, Steinhaus started the ''Mathematical Society of Kraków'', which later evolved into the Polish Mathematical Society

The Polish Mathematical Society ( pl, Polskie Towarzystwo Matematyczne) is the main professional society of Polish mathematicians and represents Polish mathematics within the European Mathematical Society (EMS) and the International Mathematical Un ...

. He was a member of ''PAU'' (the Polish Academy of Learning

The Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences or Polish Academy of Learning ( pl, Polska Akademia Umiejętności), headquartered in Kraków and founded in 1872, is one of two institutions in contemporary Poland having the nature of an academy of scien ...

) and ''PAN'' (the Polish Academy of Sciences

The Polish Academy of Sciences ( pl, Polska Akademia Nauk, PAN) is a Polish state-sponsored institution of higher learning. Headquartered in Warsaw, it is responsible for spearheading the development of science across the country by a society of ...

), ''PTM'' (the Polish Mathematical Society

The Polish Mathematical Society ( pl, Polskie Towarzystwo Matematyczne) is the main professional society of Polish mathematicians and represents Polish mathematics within the European Mathematical Society (EMS) and the International Mathematical Un ...

), the ''Wrocławskie Towarzystwo Naukowe'' () as well as many international scientific societies and science academies.

Steinhaus also published one of the first articles in ''Fundamenta Mathematicae

''Fundamenta Mathematicae'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal of mathematics with a special focus on the foundations of mathematics, concentrating on set theory, mathematical logic, topology and its interactions with algebra, and dynamical syst ...

'', in 1921. He also co-founded '' Studia Mathematica'' along with Stefan Banach

Stefan Banach ( ; 30 March 1892 – 31 August 1945) was a Polish mathematician who is generally considered one of the 20th century's most important and influential mathematicians. He was the founder of modern functional analysis, and an origina ...

(1929), and ''Zastosowania matematyki'' (Applications of Mathematics, 1953), ''Colloquium Mathematicum'', and ''Monografie Matematyczne'' (Mathematical Monographs).

He received honorary doctorate degrees from Warsaw University

The University of Warsaw ( pl, Uniwersytet Warszawski, la, Universitas Varsoviensis) is a public university in Warsaw, Poland. Established in 1816, it is the largest institution of higher learning in the country offering 37 different fields of ...

(1958), Wrocław Medical Academy (1961), Poznań University

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John ...

(1963) and Wrocław University (1965).

Steinhaus had full command of several foreign languages and was known for his aphorism

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by tra ...

s, to the point that a booklet of his most famous ones in Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

, French and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

has been published posthumously.

In 2002, the Polish Academy of Sciences and Wrocław University sponsored "2002, The Year of Hugo Steinhaus", to celebrate his contributions to Polish and world science.

Mathematician Mark Kac

Mark Kac ( ; Polish: ''Marek Kac''; August 3, 1914 – October 26, 1984) was a Polish American mathematician. His main interest was probability theory. His question, " Can one hear the shape of a drum?" set off research into spectral theory, the ...

, Steinhaus's student, wrote:

Chief works

* ''Czym jest, a czym nie jest matematyka'' (What Mathematics Is, and What It Is Not, 1923). * ''Sur le principe de la condensation de la singularités'' (with Banach, 1927) * ''Theorie der Orthogonalreihen'' (withStefan Kaczmarz

Stefan Marian Kaczmarz (March 20, 1895 in Sambor, Galicia, Austria-Hungary – 1939) was a Polish mathematician. His Kaczmarz method provided the basis for many modern imaging technologies, including the CAT scan..

Kaczmarz was a professor of ...

, 1935).

* ''Kalejdoskop matematyczny'' (Mathematical Snapshots, 1939).

* ''Taksonomia wrocławska'' (A Wroclaw Taxonomy; with others, 1951).

* ''Sur la liaison et la division des points d'un ensemble fini'' (On uniting and separating the points of a finite set, with others, 1951). One of multiple rediscoveries of Borůvka's algorithm

Borůvka's algorithm is a greedy algorithm for finding a minimum spanning tree in a graph,

or a minimum spanning forest in the case of a graph that is not connected.

It was first published in 1926 by Otakar Borůvka as a method of constructing ...

.

* ''Sto zadań'' (One Hundred Problems In Elementary Mathematics, 1964).

* ''Orzeł czy reszka'' (Heads or Tails, 1961).

* ''Słownik racjonalny'' (A Rational Dictionary, 1980).

Family

His daughter Lidya Steinhaus was married toJan Kott

Jan Kott (October 27, 1914 – December 22, 2001) was a Polish political activist, critic and theoretician of the theatre. A leading proponent of Stalinism in Poland for nearly a decade after the Soviet takeover, Kott renounced his Communist P ...

.

Grave

Steinhaus is buried in ''Cmentarz Świętej Rodziny'' in Sępolno,Wrocław

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, rou ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

.

On November 1, 2017, a controversy arose as the University of Wrocław

, ''Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Breslau'' (before 1945)

, free_label = Specialty programs

, free =

, colors = Blue

, website uni.wroc.pl

The University of Wrocław ( pl, Uniwersytet Wrocławski, U ...

took no action to pay for his grave to keep it until 2022 in face of its expiration because it supposedly "had no money". Mayor Rafał Dutkiewicz was also widely criticized for doing nothing. Random people organized a charity and paid for the grave to remain.

See also

* Freiling's axiom of symmetry *One-seventh area triangle

In plane geometry, a triangle ''ABC'' contains a triangle having one-seventh of the area of ''ABC'', which is formed as follows: the sides of this triangle lie on cevians ''p, q, r'' where

:''p'' connects ''A'' to a point on ''BC'' that is one-thi ...

* Johnson–Trotter algorithm

* Steinhaus conjecture

* Steinhaus polygon notation

* Steinhaus theorem

* Steinhaus longimeter

* Last diminisher

A last is a mechanical form shaped like a human foot. It is used by shoemakers and cordwainers in the manufacture and repair of shoes. Lasts typically come in pairs and have been made from various materials, including hardwoods, cast iron, an ...

Notes

References

Further reading

*Kazimierz Kuratowski

Kazimierz Kuratowski (; 2 February 1896 – 18 June 1980) was a Polish mathematician and logician. He was one of the leading representatives of the Warsaw School of Mathematics.

Biography and studies

Kazimierz Kuratowski was born in Warsaw, (t ...

, ''A Half Century of Polish Mathematics: Remembrances and Reflections'', Oxford, Pergamon Press

Pergamon Press was an Oxford-based publishing house, founded by Paul Rosbaud and Robert Maxwell, that published scientific and medical books and journals. Originally called Butterworth-Springer, it is now an imprint of Elsevier.

History

The cor ...

, 1980, , pp. 173–79 ''et passim''.

* Hugo Steinhaus, ''Mathematical Snapshots'', second edition, Oxford, 1951, blurb

A blurb is a short promotional piece accompanying a piece of creative work. It may be written by the author or publisher or quote praise from others. Blurbs were originally printed on the back or rear dust jacket of a book, and are now also fou ...

.

External links

*Hugo Steinhaus

in

MathSciNet

MathSciNet is a searchable online bibliographic database created by the American Mathematical Society in 1996. It contains all of the contents of the journal ''Mathematical Reviews'' (MR) since 1940 along with an extensive author database, links ...

Hugo Steinhaus

in

Zentralblatt MATH

zbMATH Open, formerly Zentralblatt MATH, is a major reviewing service providing reviews and abstracts for articles in pure and applied mathematics, produced by the Berlin office of FIZ Karlsruhe – Leibniz Institute for Information Infrastructur ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Steinhaus, Hugo

1887 births

1972 deaths

Lwów School of Mathematics

Jews from Galicia (Eastern Europe)

Members of the Lwów Scientific Society

Members of the Polish Academy of Learning

Members of the Polish Academy of Sciences

People from Jasło

Jewish atheists

Polish atheists

Polish legionnaires (World War I)

Probability theorists

Game theorists

University of Notre Dame faculty

Recipients of the State Award Badge (Poland)

Fair division researchers