Horse Latitudes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The horse latitudes are the

The horse latitudes are the

The subtropical ridge starts migrating poleward in late spring reaching its zenith in early autumn before retreating equatorward during the late fall, winter, and early spring. The equatorward migration of the subtropical ridge during the cold season is due to increasing north–south temperature differences between the poles and tropics. The latitudinal movement of the subtropical ridge is strongly correlated with the progression of the monsoon trough or

The subtropical ridge starts migrating poleward in late spring reaching its zenith in early autumn before retreating equatorward during the late fall, winter, and early spring. The equatorward migration of the subtropical ridge during the cold season is due to increasing north–south temperature differences between the poles and tropics. The latitudinal movement of the subtropical ridge is strongly correlated with the progression of the monsoon trough or

When the subtropical ridge in the northwest Pacific is stronger than normal, it leads to a wet

When the subtropical ridge in the northwest Pacific is stronger than normal, it leads to a wet

Fog characteristics.

Horse latitudes entry

in ''The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia'', Sixth Edition. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003. *

Physical Geography - The Global Environment

{{Cyclones Circles of latitude Age of Sail Meteorological phenomena Climate zones Anticyclones Tropical cyclone meteorology

latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north ...

s about 30 degrees north and south of the Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can also ...

. They are characterized by sunny skies, calm winds, and very little precipitation. They are also known as subtropical

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical and climate zones to the north and south of the tropics. Geographically part of the temperate zones of both hemispheres, they cover the middle latitudes from to approximately 35° north a ...

ridges, or highs. It is a high-pressure area

A high-pressure area, high, or anticyclone, is an area near the surface of a planet where the atmospheric pressure is greater than the pressure in the surrounding regions. Highs are middle-scale meteorological features that result from interpl ...

at the divergence of trade winds

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisp ...

and the westerlies

The westerlies, anti-trades, or prevailing westerlies, are prevailing winds from the west toward the east in the middle latitudes between 30 and 60 degrees latitude. They originate from the high-pressure areas in the horse latitudes and tren ...

.

Origin of the term

A likely and documented explanation is that the term is derived from the "dead horse" ritual of seamen (seeBeating a dead horse

Flogging a dead horse (or beating a dead horse in American English) is an idiom ascribed to Anglophones which means that a particular effort is futile, being a waste of time without a positive outcome, e.g. such as flogging a dead horse, which ...

). In this practice, the seaman paraded a straw-stuffed effigy

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...

of a horse around the deck before throwing it overboard. Seamen were paid partly in advance before a long voyage, and they frequently spent their pay all at once, resulting in a period of time without income. If they got advances from the ship's paymaster, they would incur debt. This period was called the "dead horse" time, and it usually lasted a month or two. The seaman's ceremony was to celebrate having worked off the "dead horse" debt. As west-bound shipping from Europe usually reached the subtropics at about the time the "dead horse" was worked off, the latitude became associated with the ceremony.

An alternative theory, of sufficient popularity to serve as an example of folk etymology

Folk etymology (also known as popular etymology, analogical reformation, reanalysis, morphological reanalysis or etymological reinterpretation) is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more famili ...

, is that the term ''horse latitudes'' originates from when the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

transported horses by ship to their colonies in the West Indies and Americas. Ships often became becalmed in mid-ocean in this latitude, thus severely prolonging the voyage; the resulting water shortages made it impossible for the crew to keep the horses alive, and they would throw the dead or dying animals overboard.

A third explanation, which simultaneously explains both the northern and southern horse latitudes and does not depend on the length of the voyage or the port of departure, is based on maritime terminology: a ship was said to be 'horsed' when, although there was insufficient wind for sail, the vessel could make good progress by latching on to a strong current

Currents, Current or The Current may refer to:

Science and technology

* Current (fluid), the flow of a liquid or a gas

** Air current, a flow of air

** Ocean current, a current in the ocean

*** Rip current, a kind of water current

** Current (stre ...

. This was suggested by Edward Taube in his article "The Sense of "Horse" in the Horse Latitudes" ('' Journal of Geography'', October 1967). He argued the maritime use of 'horsed' described a ship that was being carried along by an ocean current or tide in the manner of a rider on horseback. The term had been in use since the end of the seventeenth century. Furthermore, ''The India Directory'' in its entry for Fernando de Noronha

Fernando de Noronha () is an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, part of the State of Pernambuco, Brazil, and located off the Brazilian coast. It consists of 21 islands and islets, extending over an area of . Only the eponymous main island is in ...

, an island off the coast of Brazil, mentions it had been visited frequently by ships "occasioned by the currents having horsed them to the westward".

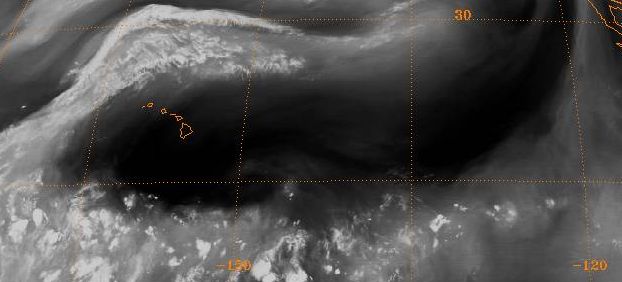

Formation

Heating of the earth at thethermal equator

The thermal equator (also known as "the heat equator") is a belt encircling Earth, defined by the set of locations having the highest mean annual temperature at each longitude around the globe. Because local temperatures are sensitive to the geogr ...

leads to large amounts of convection along the Intertropical Convergence Zone

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ ), known by sailors as the doldrums or the calms because of its monotonous windless weather, is the area where the northeast and the southeast trade winds converge. It encircles Earth near the thermal ...

. This air mass rises and then diverges, moving away from the equator in both northerly and southerly directions. As the air moves towards the mid-latitudes on both sides of the equator, it cools and sinks. This creates a ridge of high pressure near the 30th parallel in both hemispheres. At the surface level, the sinking air diverges again with some returning to the equator, creating the Hadley cell

The Hadley cell, named after George Hadley, is a global-scale tropical atmospheric circulation that features air rising near the equator, flowing poleward at a height of 10 to 15 kilometers above the earth's surface, descending in the subtropics ...

which during summer is reinforced by other climatological mechanisms such as the Rodwell–Hoskins mechanism

Rodwell–Hoskins mechanism is a hypothesis about a climatic teleconnection between the Indian/Asian summer monsoon and the climate of the Mediterranean. It stipulates that ascending air in the monsoon region induces atmospheric circulation featu ...

. Many of the world's deserts are caused by these climatological high-pressure area

A high-pressure area, high, or anticyclone, is an area near the surface of a planet where the atmospheric pressure is greater than the pressure in the surrounding regions. Highs are middle-scale meteorological features that result from interpl ...

s.

The subtropical ridge moves poleward during the summer, reaching its highest latitude in early autumn, before moving back during the cold season. The El Niño–Southern Oscillation

El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is an irregular periodic variation in winds and sea surface temperatures over the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean, affecting the climate of much of the tropics and subtropics. The warming phase of the sea te ...

(ENSO) can displace the northern hemisphere subtropical ridge, with La Niña allowing for a more northerly axis for the ridge, while El Niños show flatter, more southerly ridges. The change of the ridge position during ENSO cycles changes the tracks of tropical cyclone

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Dep ...

s that form around their equatorward and western peripheries. As the subtropical ridge varies in position and strength, it can enhance or depress monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscil ...

regimes around their low-latitude periphery.

The horse latitudes are associated with the subtropical anticyclone. The belt in the Northern Hemisphere is sometimes called the "calms of Cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

" and that in the Southern Hemisphere the "calms of Capricorn".

The consistently warm, dry, and sunny conditions of the horse latitudes are the main cause for the existence of the world's major hot deserts, such as the Sahara Desert

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

in Africa, the Arabian

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

and Syrian

Syrians ( ar, سُورِيُّون, ''Sūriyyīn'') are an Eastern Mediterranean ethnic group indigenous to the Levant. They share common Levantine Semitic roots. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend of both indi ...

deserts in the Middle East, the Mojave and Sonoran deserts in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, all in the Northern Hemisphere; and the Atacama Desert

The Atacama Desert ( es, Desierto de Atacama) is a desert plateau in South America covering a 1,600 km (990 mi) strip of land on the Pacific coast, west of the Andes Mountains. The Atacama Desert is the driest nonpolar desert in th ...

, the Kalahari Desert

The Kalahari Desert is a large semi-arid sandy savanna in Southern Africa extending for , covering much of Botswana, and parts of Namibia and South Africa.

It is not to be confused with the Angolan, Namibian, and South African Namib coastal d ...

, and the Australian Desert in the Southern Hemisphere.

Migration

The subtropical ridge starts migrating poleward in late spring reaching its zenith in early autumn before retreating equatorward during the late fall, winter, and early spring. The equatorward migration of the subtropical ridge during the cold season is due to increasing north–south temperature differences between the poles and tropics. The latitudinal movement of the subtropical ridge is strongly correlated with the progression of the monsoon trough or

The subtropical ridge starts migrating poleward in late spring reaching its zenith in early autumn before retreating equatorward during the late fall, winter, and early spring. The equatorward migration of the subtropical ridge during the cold season is due to increasing north–south temperature differences between the poles and tropics. The latitudinal movement of the subtropical ridge is strongly correlated with the progression of the monsoon trough or Intertropical Convergence Zone

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ ), known by sailors as the doldrums or the calms because of its monotonous windless weather, is the area where the northeast and the southeast trade winds converge. It encircles Earth near the thermal ...

.

Most tropical cyclone

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Dep ...

s form on the side of the subtropical ridge closer to the equator, then move poleward past the ridge axis before recurving into the main belt of the Westerlies. When the subtropical ridge shifts due to ENSO, so will the preferred tropical cyclone tracks. Areas west of Japan and Korea tend to experience many fewer September–November tropical cyclone impacts during El Niño

El Niño (; ; ) is the warm phase of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and is associated with a band of warm ocean water that develops in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific (approximately between the International Date ...

and neutral years, while mainland China experiences much greater landfall frequency during La Niña years. During El Niño years, the break in the subtropical ridge tends to lie near 130°E, which would favor the Japanese archipelago, while in La Niña years the formation of tropical cyclones, along with the subtropical ridge position, shift west, which increases the threat to China. In the Atlantic basin, the subtropical ridge position tends to lie about 5 degrees farther south during El Niño years, which leads to a more southerly recurvature for tropical cyclones during those years.

When the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation's mode is favorable to tropical cyclone development (1995–present), it amplifies the subtropical ridge across the central and eastern Atlantic.

Role in weather formation and air quality

When the subtropical ridge in the northwest Pacific is stronger than normal, it leads to a wet

When the subtropical ridge in the northwest Pacific is stronger than normal, it leads to a wet monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscil ...

season for Asia. The subtropical ridge position is linked to how far northward monsoon moisture and thunderstorm

A thunderstorm, also known as an electrical storm or a lightning storm, is a storm characterized by the presence of lightning and its acoustic effect on the Earth's atmosphere, known as thunder. Relatively weak thunderstorms are some ...

s extend into the United States. The subtropical ridge across North America typically migrates far enough northward to begin monsoon conditions across the Desert Southwest from July to September. When the subtropical ridge is farther north than normal towards the Four Corners

The Four Corners is a region of the Southwestern United States consisting of the southwestern corner of Colorado, southeastern corner of Utah, northeastern corner of Arizona, and northwestern corner of New Mexico. The Four Corners area ...

, monsoon thunderstorms can spread northward into Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

. When the high pressure moves south, its circulation cuts off the moisture, and the hot, dry continental airmass returns from the northwest, and therefore the atmosphere dries out across the Desert Southwest, causing a break in the monsoon regime.

On the subtropical ridges western edge (generally on the eastern coast of continents), the high pressure cell pushes northwards a southerly flow of tropical air. In the United States the subtropical ridge Bermuda High

The Azores High also known as North Atlantic (Subtropical) High/Anticyclone or the Bermuda-Azores High, is a large subtropical semi-permanent centre of high atmospheric pressure typically found south of the Azores in the Atlantic Ocean, at the H ...

helps create the hot, sultry summers with daily thunderstorms with buoyant airmasses typical of the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

and East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Eastern United States meets the North Atlantic Ocean. The eastern seaboard contains the coa ...

. This flow pattern also occurs on the eastern coasts of continents in other subtropical climates such as South China, southern Japan, central-eastern South America Pampas

The Pampas (from the qu, pampa, meaning "plain") are fertile South American low grasslands that cover more than and include the Argentine provinces of Buenos Aires, La Pampa, Santa Fe, Entre Ríos, and Córdoba; all of Uruguay; and Brazi ...

, southern Queensland and KwaZulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal (, also referred to as KZN and known as "the garden province") is a province of South Africa that was created in 1994 when the Zulu bantustan of KwaZulu ("Place of the Zulu" in Zulu) and Natal Province were merged. It is loca ...

province in South Africa.

When surface winds become light, the subsidence produced directly under the subtropical ridge can lead to a buildup of particulates in urban areas under the ridge, leading to widespread haze

Haze is traditionally an atmospheric phenomenon in which dust, smoke, and other dry particulates suspended in air obscure visibility and the clarity of the sky. The World Meteorological Organization manual of codes includes a classificati ...

. If the low level relative humidity

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation, dew, or fog to be present.

Humidity dep ...

rises towards 100 percent overnight, fog

Fog is a visible aerosol consisting of tiny water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the air at or near the Earth's surface. Reprint from Fog can be considered a type of low-lying cloud usually resembling stratus, and is heavily influ ...

can form.Robert Tardif (2002)Fog characteristics.

University Corporation for Atmospheric Research The University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR) is a US nonprofit consortium of more than 100 colleges and universities providing research and training in the atmospheric and related sciences. UCAR manages the National Center for Atmosph ...

. Retrieved on 2007-02-11.

See also

*Atmospheric circulation

Atmospheric circulation is the large-scale movement of air and together with ocean circulation is the means by which thermal energy is redistributed on the surface of the Earth. The Earth's atmospheric circulation varies from year to year, bu ...

*Circle of latitude

A circle of latitude or line of latitude on Earth is an abstract east– west small circle connecting all locations around Earth (ignoring elevation) at a given latitude coordinate line.

Circles of latitude are often called parallels bec ...

*Doldrums

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ ), known by sailors as the doldrums or the calms because of its monotonous windless weather, is the area where the northeast and the southeast trade winds converge. It encircles Earth near the thermal e ...

*Polar front

In meteorology, the polar front is the weather front boundary between the polar cell and the Ferrel cell around the 60° latitude, near the polar regions, in both hemisphere. At this boundary a sharp gradient in temperature occurs between the ...

*Intertropical Convergence Zone

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ ), known by sailors as the doldrums or the calms because of its monotonous windless weather, is the area where the northeast and the southeast trade winds converge. It encircles Earth near the thermal ...

*Roaring Forties

The Roaring Forties are strong westerly winds found in the Southern Hemisphere, generally between the latitudes of 40°S and 50°S. The strong west-to-east air currents are caused by the combination of air being displaced from the Equator ...

References

Further reading

Horse latitudes entry

in ''The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia'', Sixth Edition. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003. *

External links

Physical Geography - The Global Environment

{{Cyclones Circles of latitude Age of Sail Meteorological phenomena Climate zones Anticyclones Tropical cyclone meteorology