Holzminden prisoner-of-war camp on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Holzminden prisoner-of-war camp was a

Holzminden prisoner-of-war camp was a

The prisoner-of-war camp opened at the beginning of September 1917, under the auspices of X Army Corps, headquartered in

The prisoner-of-war camp opened at the beginning of September 1917, under the auspices of X Army Corps, headquartered in

The camps of X Corps came under the authority of General Karl von Hänisch, who encouraged a harsh regime. The

The camps of X Corps came under the authority of General Karl von Hänisch, who encouraged a harsh regime. The  Prisoners found a variety of ways of dealing with the enforced idleness and monotony of prison life. Activities included sports (

Prisoners found a variety of ways of dealing with the enforced idleness and monotony of prison life. Activities included sports (

* Edward Donald Bellew, VC (1882–1961), Canadian recipient of the

* Edward Donald Bellew, VC (1882–1961), Canadian recipient of the

The First Great Escape

', was produced by

German site (partly in English) on the PoW and internment camps, with many photos

Site on military prisoners and civilian internees at Holzminden, mainly in the internment camps

{{Coord, 51.832490, N, 9.460941, E, display=title German Empire in World War I Prisoner-of-war camps in Germany World War I prisoner-of-war camps World War I sites in Germany Holzminden (district) World War I crimes by Imperial Germany

Holzminden prisoner-of-war camp was a

Holzminden prisoner-of-war camp was a World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fight ...

prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. P ...

for British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts ...

officers

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," ...

('' Offizier Gefangenenlager'') located in Holzminden

Holzminden (; nds, Holtsminne) is a town in southern Lower Saxony, Germany. It is the capital of the district of Holzminden. It is located on the river Weser, which at this point forms the border with the state of North Rhine-Westphalia.

Histor ...

, Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony (german: Niedersachsen ; nds, Neddersassen; stq, Läichsaksen) is a German state (') in northwestern Germany. It is the second-largest state by land area, with , and fourth-largest in population (8 million in 2021) among the 16 ...

, Germany. It opened in September 1917, and closed with the final repatriation of prisoners in December 1918. It is remembered as the location of the largest PoW escape of the war, in July 1918: 29 officers escaped through a tunnel, of whom ten evaded subsequent recapture and managed to make their way back to Britain.

The prisoner-of-war camp is not to be confused with Holzminden internment camp, a much larger pair of camps (one for men, and one for women and children) located on the outskirts of the town, in which civilian internees were held. The internees mainly comprised Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin scree ...

, Russian, Belgian and French nationals, as well as a small number of Britons.

The camp

The prisoner-of-war camp opened at the beginning of September 1917, under the auspices of X Army Corps, headquartered in

The prisoner-of-war camp opened at the beginning of September 1917, under the auspices of X Army Corps, headquartered in Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German States of Germany, state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the List of cities in Germany by population, 13th-largest city in Germa ...

. Other camps for officers under the command of X Corps, all smaller, were those at Clausthal

Clausthal-Zellerfeld is a town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is located in the southwestern part of the Harz mountains. Its population is approximately 15,000. The City is the location of the Clausthal University of Technology. The health r ...

, Ströhen and Schwarmstedt

Schwarmstedt is a municipality in the Heidekreis in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated near the confluence of the rivers Aller and Leine, approx. 20 km south of Bad Fallingbostel, and 30 km east of Nienburg. Further districts of t ...

. Many of the initial intake of prisoners were transferred from these camps, and others at Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau (; abbreviated as Freiburg i. Br. or Freiburg i. B.; Low Alemannic: ''Friburg im Brisgau''), commonly referred to as Freiburg, is an independent city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With a population of about 230,000 (as ...

and Krefeld

Krefeld ( , ; li, Krieëvel ), also spelled Crefeld until 1925 (though the spelling was still being used in British papers throughout the Second World War), is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located northwest of Düsseldor ...

, which had become overcrowded.

The camp held between 500 and 600 officer prisoners. There were also approximately 100–160 other ranks prisoners, designated orderlies

In healthcare, an orderly (also known as a ward assistant, nurse assistant or healthcare assistant) is a hospital attendant whose job consists of assisting medical and nursing staff with various nursing and medical interventions. The highest r ...

: these men acted as servants to the officers and performed other menial tasks around the camp.

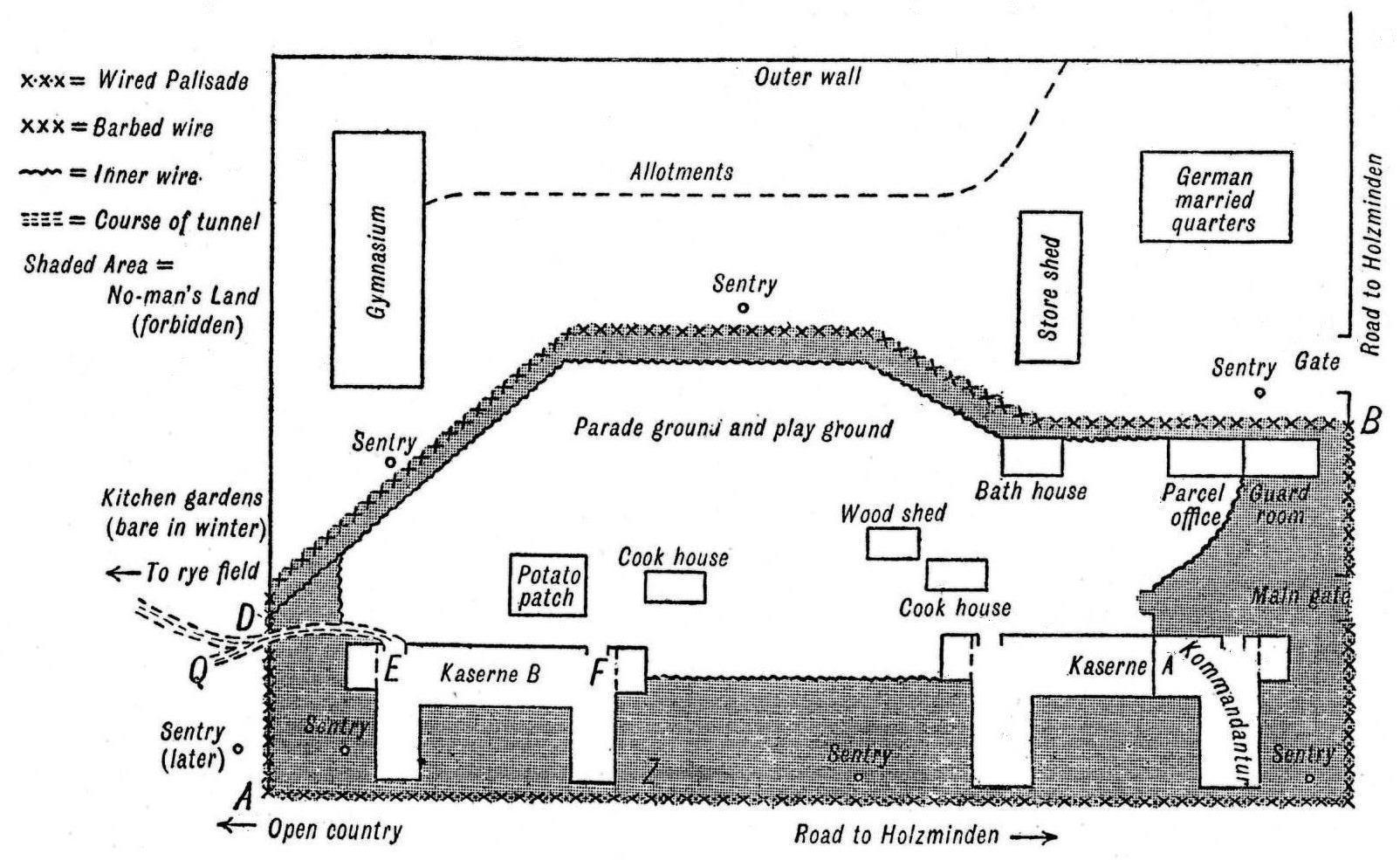

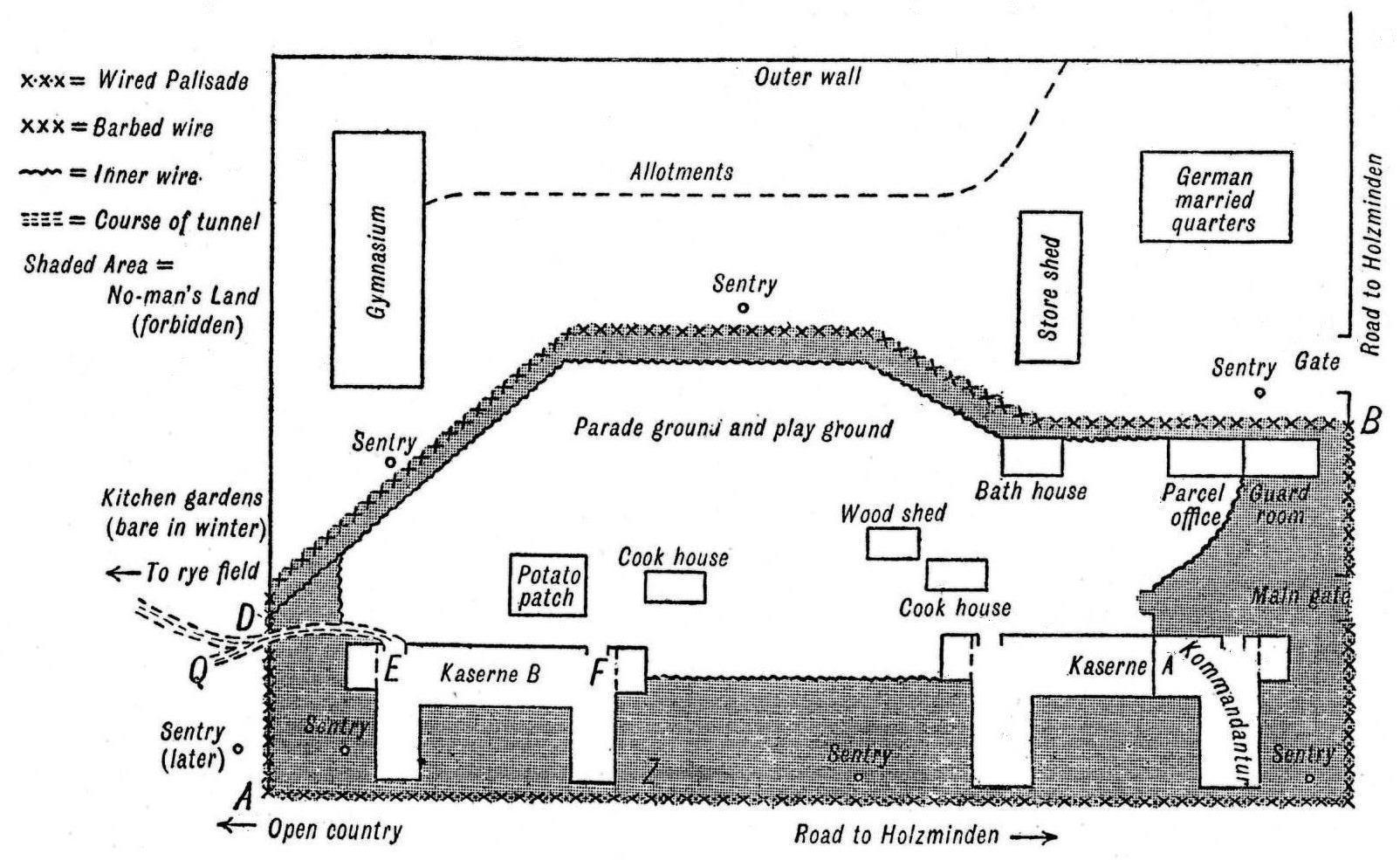

The camp occupied the premises of a cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

barracks

Barracks are usually a group of long buildings built to house military personnel or laborers. The English word originates from the 17th century via French and Italian from an old Spanish word "barraca" ("soldier's tent"), but today barracks are u ...

erected in 1913. The principal buildings, in which the prisoners lived, were two four-storey barrack blocks, known to the Germans as ''Kaserne'' A and ''Kaserne'' B, and to the British as A House and B House. Although the greater part of both blocks housed officer prisoners, both were partitioned internally: the western end of ''Kaserne'' A formed the ''Kommandantur'', in which the German garrison was quartered; while the eastern end of ''Kaserne'' B was occupied by the orderlies. The basements included cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

in which prisoners could be held in solitary confinement

Solitary confinement is a form of imprisonment in which the inmate lives in a single cell with little or no meaningful contact with other people. A prison may enforce stricter measures to control contraband on a solitary prisoner and use addi ...

as punishment. Several wooden single-storey buildings in front of the barrack blocks accommodated service facilities, including the cookhouses, woodshed, bath-house, and parcel-room.

Regime and camp life

The camps of X Corps came under the authority of General Karl von Hänisch, who encouraged a harsh regime. The

The camps of X Corps came under the authority of General Karl von Hänisch, who encouraged a harsh regime. The Kommandant

Commandant ( or ) is a title often given to the officer in charge of a military (or other uniformed service) training establishment or academy. This usage is common in English-speaking nations. In some countries it may be a military or police ran ...

at Holzminden when it opened was the elderly Colonel Habrecht ("a kindly old dodderer of about seventy"); but he was replaced after less than a month by his second-in-command, Hauptmann

is a German word usually translated as captain when it is used as an officer's rank in the German, Austrian, and Swiss armies. While in contemporary German means 'main', it also has and originally had the meaning of 'head', i.e. ' literal ...

Karl Niemeyer, who remained Kommandant until the camp's closure. Niemeyer's twin brother, Heinrich, was Kommandant of the camp at Clausthal

Clausthal-Zellerfeld is a town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is located in the southwestern part of the Harz mountains. Its population is approximately 15,000. The City is the location of the Clausthal University of Technology. The health r ...

. The brothers had lived in Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee i ...

, Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michi ...

, for 17 years – until the spring of 1917, when the United States entered the war – and as a result Karl Niemeyer spoke American English

American English, sometimes called United States English or U.S. English, is the set of varieties of the English language native to the United States. English is the most widely spoken language in the United States and in most circumstances ...

. However, in the view of the British POWs, Niemeyer's English was filled with "errors" and American slang

Slang is vocabulary (words, phrases, and linguistic usages) of an informal register, common in spoken conversation but avoided in formal writing. It also sometimes refers to the language generally exclusive to the members of particular in-gr ...

terms. One POW mocked the Kommandant's English as " bar-tender Yank"; while another stated that Niemeyer "talked broken American under the impression that it was English". The prisoners constantly ridiculed him, and nicknamed him "Milwaukee Bill". One error, which became notorious, was his assertion that "You think I do not understand the English, but I do. I know damn all about you."

The camp was described by the ''Daily Sketch

The ''Daily Sketch'' was a British national tabloid newspaper, founded in Manchester in 1909 by Sir Edward Hulton.

It was bought in 1920 by Lord Rothermere's Daily Mirror Newspapers, but in 1925 Rothermere sold it to William and Gomer Berr ...

'' in January 1919 as "the worst camp in Germany". This assessment needs to be understood in context: as a rule, officer prisoners enjoyed a more comfortable regime than other ranks prisoners (see World War I prisoners of war in Germany

The situation of World War I prisoners of war in Germany is an aspect of the conflict little covered by historical research. However, the number of soldiers imprisoned reached a little over seven million for all the belligerents, of whom around 2, ...

). Nevertheless, Niemeyer's regime was often arbitrary and punitive, and atrocities were committed, including the bayonet

A bayonet (from French ) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.Brayley, Martin, ''Bayonets: An Illustra ...

ing of prisoners. He was put on a British war crimes prosecution blacklist for the reported allegations of unnecessary ill treatment. Two "celebrity" prisoners who appear to have been singled out for harsh treatment were William Leefe Robinson (who had shot down a German airship over Britain, and who spent much of his time at Holzminden in solitary confinement), and Algernon Bird, the 61st victim of Baron von Richthofen. Robinson died in England in December 1918 from the effects of the Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

pandemic, but the ''Daily Express

The ''Daily Express'' is a national daily United Kingdom middle-market newspaper printed in tabloid format. Published in London, it is the flagship of Express Newspapers, owned by publisher Reach plc. It was first published as a broadshee ...

'' was in no doubt that he was "in reality driven to death by the notorious Niemeyer.... He was murdered by Niemeyer, who was resolved to employ every instrument of cruelty against him".

One deprivation suffered by the prisoners was a poor diet, although again this must be seen in context: as a result of the economic blockade of Germany

The Blockade of Germany, or the Blockade of Europe, occurred from 1914 to 1919. The prolonged naval blockade was conducted by the Allies during and after World War I in an effort to restrict the maritime supply of goods to the Central Powers, ...

, little food was available locally even for the civilian population. Prisoners were able to supplement their diet with the contents of parcels sent by their families at home, and by the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, an ...

and other humanitarian organisations. As a result, they were often better fed than the Germans. Prisoners were often able to use items of food to bribe their guards in return for lenient treatment or contraband equipment; while at other times they made a point of taunting their captors with the superiority of their material welfare, for example by drawing their full ration of German black bread only to burn it. Before the prisoners finally left the camp in December 1918, they made a bonfire

A bonfire is a large and controlled outdoor fire, used either for informal disposal of burnable waste material or as part of a celebration.

Etymology

The earliest recorded uses of the word date back to the late 15th century, with the Cath ...

of the furniture and everything else combustible: "it was a splendid sight and the Germans could only stand by helplessly, condemning the waste".

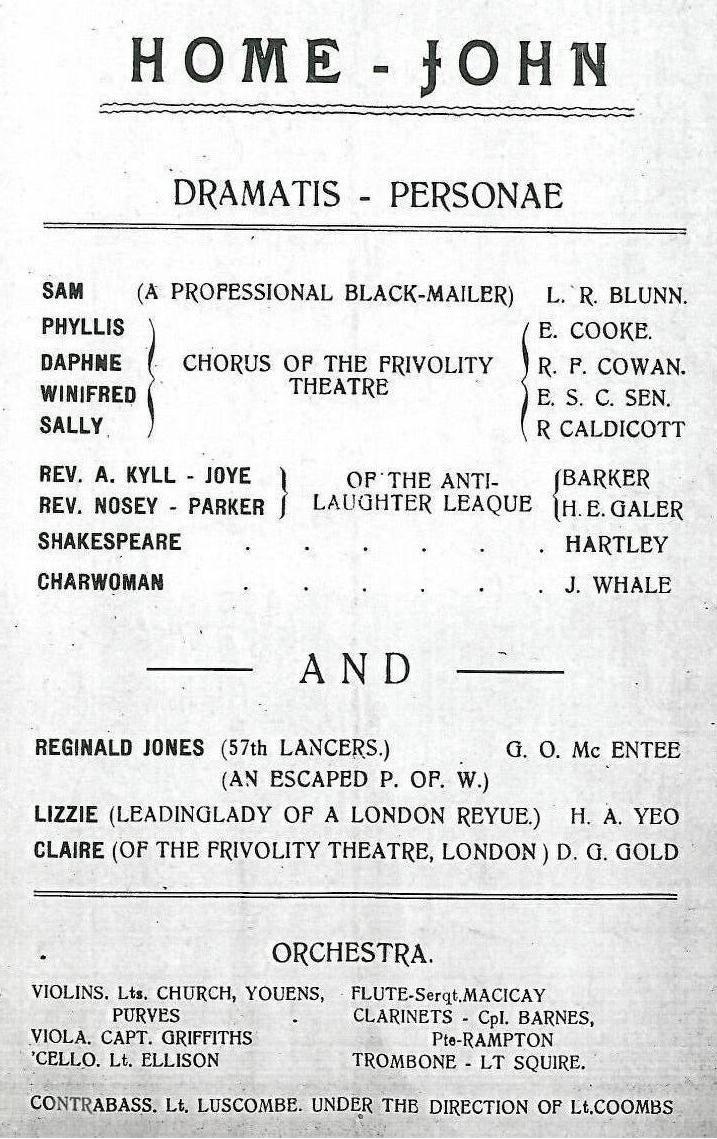

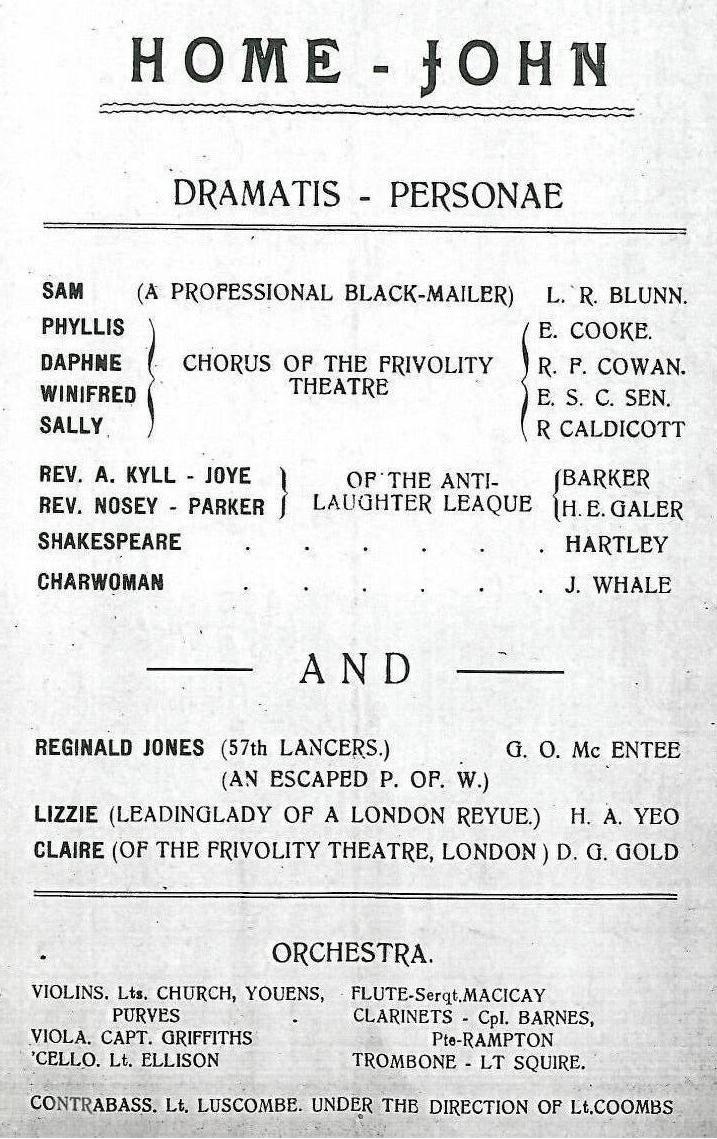

Prisoners found a variety of ways of dealing with the enforced idleness and monotony of prison life. Activities included sports (

Prisoners found a variety of ways of dealing with the enforced idleness and monotony of prison life. Activities included sports (football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, Kick (football), kicking a Football (ball), ball to score a Goal (sport), goal. Unqualified, Football (word), the word ''football'' normally means the form of football tha ...

, hockey

Hockey is a term used to denote a family of various types of both summer and winter team sports which originated on either an outdoor field, sheet of ice, or dry floor such as in a gymnasium. While these sports vary in specific rules, numbers o ...

and tennis

Tennis is a racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent ( singles) or between two teams of two players each ( doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket that is strung with cord to strike a hollow rubber ball c ...

were all played), concerts and plays, lectures, debates, and reading. James Whale

James Whale (22 July 1889 – 29 May 1957) was an English film director, theatre director and actor, who spent the greater part of his career in Hollywood. He is best remembered for several horror films: ''Frankenstein'' (1931), '' The Old ...

found the amateur theatricals, in which he participated as an actor, writer, producer, and set designer, "a source of great pleasure and amusement", and the audience reaction "intoxicating": it was his introduction to stagecraft, and he went on to become a leading Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywoo ...

director

Director may refer to:

Literature

* ''Director'' (magazine), a British magazine

* ''The Director'' (novel), a 1971 novel by Henry Denker

* ''The Director'' (play), a 2000 play by Nancy Hasty

Music

* Director (band), an Irish rock band

* ''D ...

. O. G. S. Crawford spent much of his time reading and studying, and later reported that he was "far less unhappy" at Holzminden than he had been at his public school, Marlborough College

( 1 Corinthians 3:6: God gives the increase)

, established =

, type = Public SchoolIndependent day and boarding

, religion = Church of England

, president = Nicholas Holtam

, head_label = Master

, head = Louise ...

.

Escapes

From the outset, numerous officer prisoners attempted to escape from the camp. Techniques included cutting through the perimeter fence, and walking through the gates disguised as German guards, civilian workers, or (on at least one occasion) a woman. Many of these escapes were successful in the first instance, but virtually all escapers were recaptured within a matter of days. The largest and most celebrated escape was that made through a tunnel, on the night of 23/24 July 1918. The tunnel had been under excavation for some nine months. Its entrance was concealed under a staircase in the orderlies' quarters in ''Kaserne'' B. As officers were forbidden to enter the orderlies' quarters, in the early months the excavators had to reach it by disguising themselves in orderlies' uniforms. At a later stage, a secret access door between the officers' and orderlies' quarters was created in the attic. Eighty-six officers were on the list of those waiting to escape but, on the night, the tunnel partially collapsed on the thirtieth man, leading to the abandonment of the enterprise. Of the twenty-nine who did escape, ten succeeded in making their way to the neutralNetherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Neth ...

and eventually back to Britain. Among them was Colonel Charles Rathborne, the Senior British Officer in the camp, who – on account of his good German – was able to travel by rail without arousing suspicion, and managed to cross the Dutch border after only five days. The other escapers travelled on foot, and most took at least 14 days. Edgar Henry Garland was one of the unsuccessful participants in the escape. He would go on to make a total of eight escape attempts.

The camp today

Although now surrounded by suburban development, the two main barrack blocks of the camp survive, and are still in military use as barracks for theGerman Army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

.

Notable prisoners

* Edward Donald Bellew, VC (1882–1961), Canadian recipient of the

* Edward Donald Bellew, VC (1882–1961), Canadian recipient of the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

* Commander Edward Bingham, VC, (1881–1939), Royal Navy recipient of the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

* Algernon Frederick Bird (1896–1957), 61st victim of Baron Manfred von Richthofen

Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen (; 2 May 1892 – 21 April 1918), known in English as Baron von Richthofen or the Red Baron, was a fighter pilot with the German Air Force during World War I. He is considered the ace-of-aces of th ...

* Arthur Bourinot

Arthur Stanley Bourinot, SM (November 3, 1893 – January 17, 1969) was a Canadian lawyer, scholar, and poet. "His carefully researched historical and biographical books and articles on Canadian poets, such as Duncan Campbell Scott, Archi ...

(1893–1969), Canadian lawyer and poet

* John Keith Bousfield (1893–1945), later general manager of the Asiatic Petroleum Company Asiatic Petroleum Company (APC) was a joint venture between the Shell and Royal Dutch oil companies founded in 1903. It operated in Asia in the early twentieth century. The corporate headquarters were on The Bund in Shanghai, China. The division ...

and member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong

The Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (LegCo) is the unicameral legislature of Hong Kong. It sits under China's " one country, two systems" constitutional arrangement, and is the power centre of Hong Ko ...

* Michael Claude Hamilton Bowes-Lyon (1893–1953), son of the 14th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne, and brother of the future Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (4 August 1900 – 30 March 2002) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 to 6 February 1952 as the wife of King George VI. She was th ...

* O. G. S. Crawford (1886–1957), archaeologist

* Gerard Crole (1894–1965), Scottish international rugby union and cricket player

* Aubrey de Sélincourt (1894–1962), writer, classical scholar and translator

* Charles Eaton (1895–1979), later Royal Australian Air Force officer and diplomat

* Edgar Henry Garland (1895–4 May 1973), New Zealand aviator

* Christopher Guy Gilbert (1893–1973), 31st victim of Baron Manfred von Richthofen

Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen (; 2 May 1892 – 21 April 1918), known in English as Baron von Richthofen or the Red Baron, was a fighter pilot with the German Air Force during World War I. He is considered the ace-of-aces of th ...

* F. W. Harvey

Frederick William Harvey DCM (26 March 1888 – 13 February 1957), often known as Will Harvey, was an English poet, broadcaster and solicitor. His poetry became widely popular during and after World War I.

Early life

Harvey was born in 1888 in ...

(1888–1957), poet

* Brian Horrocks

Lieutenant-General Sir Brian Gwynne Horrocks, (7 September 1895 – 4 January 1985) was a British Army officer, chiefly remembered as the commander of XXX Corps in Operation Market Garden and other operations during the Second World W ...

(1895–1985), World War II British army general

* William Donald Patrick (1889–1967), afterwards Lord Patrick, Scottish advocate and judge, and later member of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conv ...

* William Leefe Robinson, VC (1895–1918), first British pilot to shoot down a German airship over Britain

* Erroll Chunder Sen

Erroll Suvo Chunder Sen (13 March 1899 – after December 1941?) was an Indian pilot who served in the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Air Force during the First World War, and who was among the first Indian military aviators.

Family and early li ...

(c. 1899 – after December 1941?), Indian military aviator

* William Stephenson

Sir William Samuel Stephenson (23 January 1897 – 31 January 1989), born William Samuel Clouston Stanger, was a Canadian soldier, fighter pilot, businessman and spymaster who served as the senior representative of the British Security Coo ...

(1897–1989), spy master, businessman, fighter pilot and one of the real-life inspirations for James Bond

The ''James Bond'' series focuses on a fictional British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels and two short-story collections. Since Fleming's death in 1964, eight other authors have ...

* James Whale

James Whale (22 July 1889 – 29 May 1957) was an English film director, theatre director and actor, who spent the greater part of his career in Hollywood. He is best remembered for several horror films: ''Frankenstein'' (1931), '' The Old ...

(1889–1957), later Hollywood film director

* F. W. Winterbotham (1897–1990), World War II intelligence officer

Film

* A fictionalised treatment of the tunnel escape from Holzminden was filmed as ''Who Goes Next?

''Who Goes Next?'' is a 1938 British war drama film directed by Maurice Elvey and starring Barry K. Barnes, Sophie Stewart and Jack Hawkins. The story was inspired by the real-life escape of 29 officers through a tunnel from Holzminden prisoner ...

'', and released in March 1938. It was directed by Maurice Elvey

Maurice Elvey (11 November 1887 – 28 August 1967) was one of the most prolific film directors in British history. He directed nearly 200 films between 1913 and 1957. During the silent film era he directed as many as twenty films per year. He ...

, and starred Barry K. Barnes.Hanson 2011, p. 260.

* A documentary film describing the 1918 escape, The First Great Escape

', was produced by

National Geographic

''National Geographic'' (formerly the ''National Geographic Magazine'', sometimes branded as NAT GEO) is a popular American monthly magazine published by National Geographic Partners. Known for its photojournalism, it is one of the most widely ...

in 2014.

See also

*World War I prisoners of war in Germany

The situation of World War I prisoners of war in Germany is an aspect of the conflict little covered by historical research. However, the number of soldiers imprisoned reached a little over seven million for all the belligerents, of whom around 2, ...

* List of prisoner-of-war camps in Germany For lists of German prisoner-of-war camps, see:

* German prisoner-of-war camps in World War I

* German prisoner-of-war camps in World War II

Nazi Germany operated around 1,000 prisoner-of-war camps (german: Kriegsgefangenenlager) during World War ...

* List of prisoner-of-war escapes

References

Bibliography

Memoirs

* * * * * *Secondary works

* * * *External links

* List of names of 542 PoWs at Holzminden (incomplete).German site (partly in English) on the PoW and internment camps, with many photos

Site on military prisoners and civilian internees at Holzminden, mainly in the internment camps

{{Coord, 51.832490, N, 9.460941, E, display=title German Empire in World War I Prisoner-of-war camps in Germany World War I prisoner-of-war camps World War I sites in Germany Holzminden (district) World War I crimes by Imperial Germany