History of the horse in Britain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The known history of the horse in Britain starts with

The known history of the horse in Britain starts with

During the Devensian glaciation, the northernmost part of the peninsula from which Britain was formed was covered with

During the Devensian glaciation, the northernmost part of the peninsula from which Britain was formed was covered with

Domesticated horses were present in

Domesticated horses were present in

By the time of

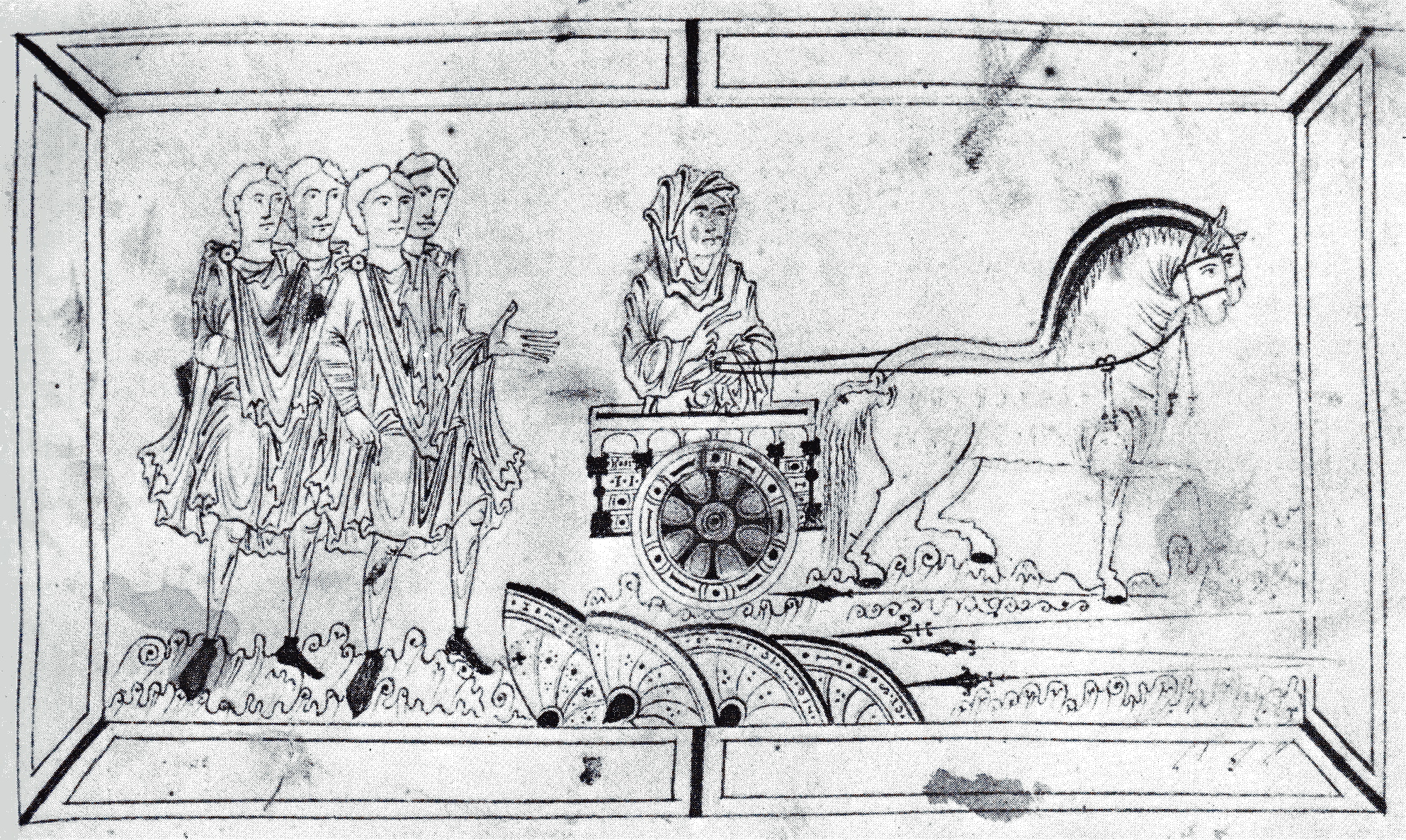

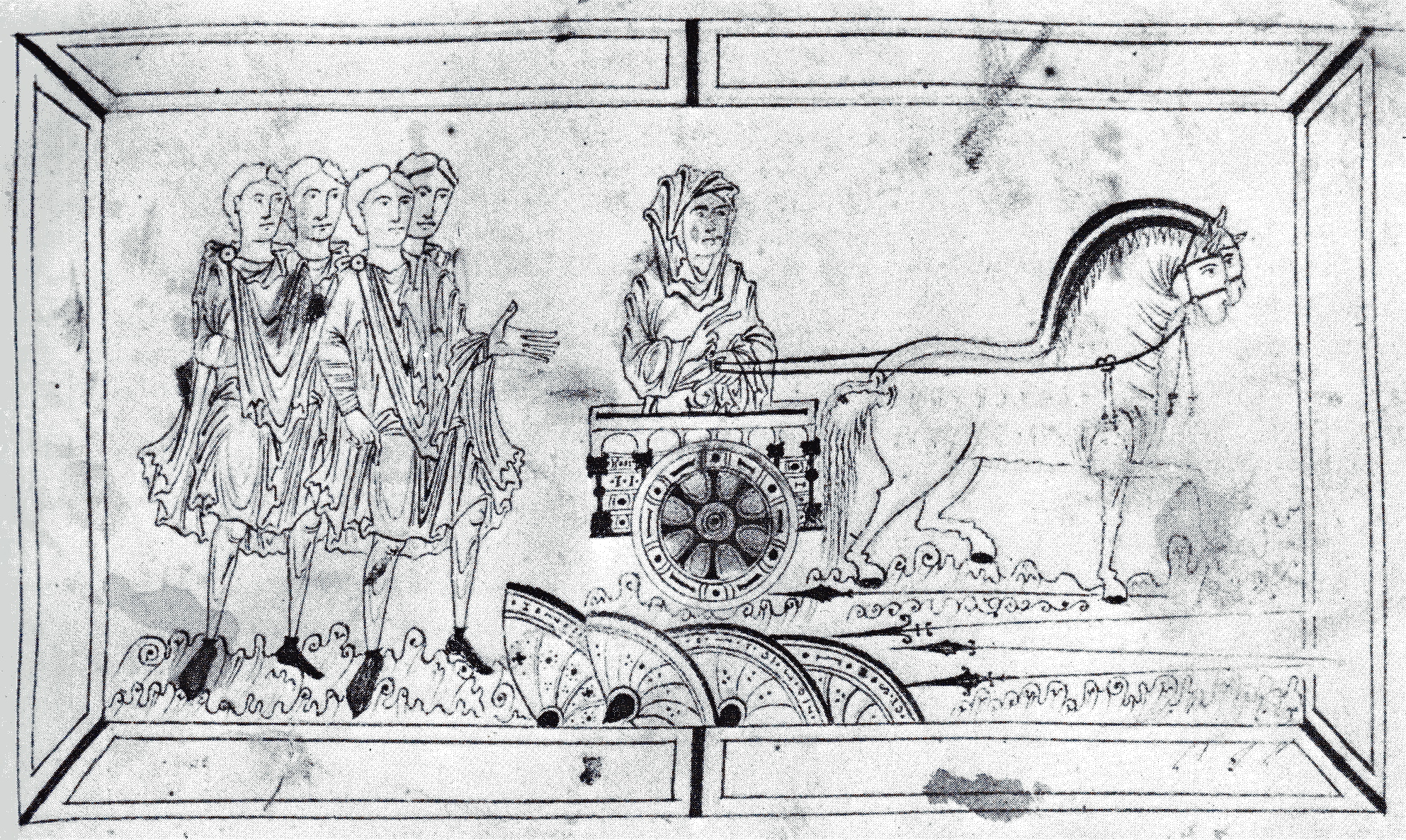

By the time of  One of the earliest records of British horses being recognised for their quality and exported dates from the Roman era; many British horses were taken to Italy to improve native stock. Some of the earliest evidence of horses used for sport in Britain also dates from Roman times, a chariot-racing arena having been discovered at

One of the earliest records of British horses being recognised for their quality and exported dates from the Roman era; many British horses were taken to Italy to improve native stock. Some of the earliest evidence of horses used for sport in Britain also dates from Roman times, a chariot-racing arena having been discovered at

(search "Factoids" for text "horse"). PASE. 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2012. They were often included in the price paid for land and in Horses held religious significance in

Horses held religious significance in  Although there is reference to

Although there is reference to

''Times Higher Education''. 1999. Retrieved 28 February 2012. In the 11th century, Anglo-Saxon warriors on horseback fought successfully against Viking, Welsh and Scottish armies, the latter including Norman allies. Although these mounted troops have been described as cavalry, their weapons and armour were similar to those of foot soldiers, and they did not fight as an organised group in the way that cavalries are normally understood to have done.

Although these mounted troops have been described as cavalry, their weapons and armour were similar to those of foot soldiers, and they did not fight as an organised group in the way that cavalries are normally understood to have done.

The introduction of the horse-drawn, four-wheeled wagon in Britain, by the early 15th century at the latest, meant that much heavier loads could be hauled, but brought with it the necessity for horse teams capable of hauling those heavier loads over the poor roads of the time. Where loads were suitable, and the ground was exceptionally poor, pack horses had an advantage over

The introduction of the horse-drawn, four-wheeled wagon in Britain, by the early 15th century at the latest, meant that much heavier loads could be hauled, but brought with it the necessity for horse teams capable of hauling those heavier loads over the poor roads of the time. Where loads were suitable, and the ground was exceptionally poor, pack horses had an advantage over  When Gervase Markham published his ''Cavalarice, or the English Horseman'' in 1617, farmers were not only using pack horses, farm horses and cart horses, but were also breeding horses for Saddle, saddling and driving (horse), driving. Markham recommended crossing native horses with other breeds for particular purposes, for example suggesting Turkoman horse, Turks or Irish Hobbies as an outcross to produce riding animals, Friesian horse, Friesland and Flanders horses to produce light driving animals, and Black Forest Horse, German heavy draught horses to produce heavy haulage animals. Horse fairs were numerous, and some of the earliest mentions of specific breeds, such as Cleveland Bay, Cleveland horses and Suffolk Punch horses, date from this time. Large Dutch horses were imported by William III of England, King William III (1650 – 1702) when he discovered that existing cart horses did not have the strength for the task of draining the Fens. These horses became known as Old English Black, Lincolnshire Blacks, and the English draft horse, heavy draught horses of today are their descendants. By the middle of the 17th century, the reputation of the British horse throughout Europe had become so good that, according to Sir Jonas Moore in 1703, "since the peace treaty with France, farmers had been offered by Frenchmen three times the accustomed price for their horses".

During the reign of Charles I of England, Charles I (1625 – 1649), passion for racing and racehorses, and for swift horses for the hunting field, became the focus of horse breeding to the point that there was a dearth of the heavier horses used in tournament and for warfare. This led to complaints, as there was still a need for stronger, more powerful types of horse. The English Civil War, from 1642 to 1651, disrupted horse racing; Oliver Cromwell banned horse racing and ordered that all race horses and spectators at such an event should be seized. He concentrated on the breeding of animals suited as cavalry horses, by encouraging crossbreeding of lightweight racing horses with the heavier working horses, and effectively produced a new type of horse altogether in the warmblood. The export of any horse other than geldings was prohibited, and the ending of the war resulted in hardship for horse breeders, as demand for their horses was significantly reduced; but an illicit trade in horses flourished with wealthier Europeans, who wanted to buy from the vastly-improved British stock. It was not until 1656 that legislation removed the restrictions on horses for export. With the Charles II of England#Restoration, Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the breeding of quality horses was begun again "from scratch".

When Gervase Markham published his ''Cavalarice, or the English Horseman'' in 1617, farmers were not only using pack horses, farm horses and cart horses, but were also breeding horses for Saddle, saddling and driving (horse), driving. Markham recommended crossing native horses with other breeds for particular purposes, for example suggesting Turkoman horse, Turks or Irish Hobbies as an outcross to produce riding animals, Friesian horse, Friesland and Flanders horses to produce light driving animals, and Black Forest Horse, German heavy draught horses to produce heavy haulage animals. Horse fairs were numerous, and some of the earliest mentions of specific breeds, such as Cleveland Bay, Cleveland horses and Suffolk Punch horses, date from this time. Large Dutch horses were imported by William III of England, King William III (1650 – 1702) when he discovered that existing cart horses did not have the strength for the task of draining the Fens. These horses became known as Old English Black, Lincolnshire Blacks, and the English draft horse, heavy draught horses of today are their descendants. By the middle of the 17th century, the reputation of the British horse throughout Europe had become so good that, according to Sir Jonas Moore in 1703, "since the peace treaty with France, farmers had been offered by Frenchmen three times the accustomed price for their horses".

During the reign of Charles I of England, Charles I (1625 – 1649), passion for racing and racehorses, and for swift horses for the hunting field, became the focus of horse breeding to the point that there was a dearth of the heavier horses used in tournament and for warfare. This led to complaints, as there was still a need for stronger, more powerful types of horse. The English Civil War, from 1642 to 1651, disrupted horse racing; Oliver Cromwell banned horse racing and ordered that all race horses and spectators at such an event should be seized. He concentrated on the breeding of animals suited as cavalry horses, by encouraging crossbreeding of lightweight racing horses with the heavier working horses, and effectively produced a new type of horse altogether in the warmblood. The export of any horse other than geldings was prohibited, and the ending of the war resulted in hardship for horse breeders, as demand for their horses was significantly reduced; but an illicit trade in horses flourished with wealthier Europeans, who wanted to buy from the vastly-improved British stock. It was not until 1656 that legislation removed the restrictions on horses for export. With the Charles II of England#Restoration, Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the breeding of quality horses was begun again "from scratch".

Horse-powered agricultural implements were improved during this period. By 1600, a lighter plough which could be drawn by two horses, the "Dutch plough", was used in eastern England; this was followed in 1730 by the lightweight Plough#Improved designs, Rotherham plough, an unwheeled, or "swing" plough. It was advertised as reducing ploughing times by a third, or using a third less horsepower for the same ploughing time. The improved seed drill and Hoe (tool)#horse-hoe, horse-hoe were invented by Jethro Tull (agriculturist), Jethro Tull in 1731; but it took more than 100 years for these designs to come into common use. The earliest horse-powered threshing machines, which were installed permanently in barns, were developed towards the end of the 18th century.

The use of fast horse-drawn coaches, known as 'Flying Coaches', began in 1669. Travelling between London and Oxford by coach had involved an overnight stay at Beaconsfield, but Oxford University organised a project to allow completion of the journey between sunrise and sunset. The project succeeded, and was quickly copied by Cambridge University; by the end of Charles II of England, Charles II's reign, in 1685, Flying Coaches ran three times a week from London to all major towns, in good conditions covering a distance of around fifty miles in a day. The Thoroughbred horse was developed from about this time, with native mares being crossbred to Arabian horse, Arab, Turk and Barb horses to produce excellent racehorses; the ''General Stud Book'', giving clear and detailed pedigrees, was first published in the 1790s, and the lineage of today's Thoroughbred horses can be traced with great accuracy to 1791. Horses running in races sponsored by the monarchy then carried weights of around , more than the usual weight of 8–10 stone (51–64 kg), indicating that horse racing, hunting and Steeplechase (horse racing), chasing partly originated in a need for military training.

Horse-powered agricultural implements were improved during this period. By 1600, a lighter plough which could be drawn by two horses, the "Dutch plough", was used in eastern England; this was followed in 1730 by the lightweight Plough#Improved designs, Rotherham plough, an unwheeled, or "swing" plough. It was advertised as reducing ploughing times by a third, or using a third less horsepower for the same ploughing time. The improved seed drill and Hoe (tool)#horse-hoe, horse-hoe were invented by Jethro Tull (agriculturist), Jethro Tull in 1731; but it took more than 100 years for these designs to come into common use. The earliest horse-powered threshing machines, which were installed permanently in barns, were developed towards the end of the 18th century.

The use of fast horse-drawn coaches, known as 'Flying Coaches', began in 1669. Travelling between London and Oxford by coach had involved an overnight stay at Beaconsfield, but Oxford University organised a project to allow completion of the journey between sunrise and sunset. The project succeeded, and was quickly copied by Cambridge University; by the end of Charles II of England, Charles II's reign, in 1685, Flying Coaches ran three times a week from London to all major towns, in good conditions covering a distance of around fifty miles in a day. The Thoroughbred horse was developed from about this time, with native mares being crossbred to Arabian horse, Arab, Turk and Barb horses to produce excellent racehorses; the ''General Stud Book'', giving clear and detailed pedigrees, was first published in the 1790s, and the lineage of today's Thoroughbred horses can be traced with great accuracy to 1791. Horses running in races sponsored by the monarchy then carried weights of around , more than the usual weight of 8–10 stone (51–64 kg), indicating that horse racing, hunting and Steeplechase (horse racing), chasing partly originated in a need for military training.

The Mail coach service began towards the end of the 18th century, adding to the existing use of fast coaches. The horses required for fast coaches were mainly produced by outcrossing heavy farm mares to the lighter racing type of horse, as a combination of speed, agility, endurance and strength was required. While the aristocracy and gentry paid high prices for matched teams of quality horses, farmers sold the best of their animals at a good profit, keeping lower-quality animals for themselves, or for sale as saddle horses. The coaching trade grew from the trade in carriage of goods; some public transport was provided by farmers, who could keep large numbers of horses on their own farms more cheaply than those who had to buy in food and forage. However, proprietors of

The Mail coach service began towards the end of the 18th century, adding to the existing use of fast coaches. The horses required for fast coaches were mainly produced by outcrossing heavy farm mares to the lighter racing type of horse, as a combination of speed, agility, endurance and strength was required. While the aristocracy and gentry paid high prices for matched teams of quality horses, farmers sold the best of their animals at a good profit, keeping lower-quality animals for themselves, or for sale as saddle horses. The coaching trade grew from the trade in carriage of goods; some public transport was provided by farmers, who could keep large numbers of horses on their own farms more cheaply than those who had to buy in food and forage. However, proprietors of

Horses remained the primary source of power for agriculture, mining, transport and warfare, until the arrival of the steam engine. The Middleton Railway had been established for industrial use by an Acts of Parliament in the United Kingdom, Act of Parliament in 1785; Parliament also allowed the construction of the Surrey Iron Railway, intended to carry goods, in 1801, and the Oystermouth Railway, later known as the Swansea and Mumbles Railway, in 1804. These initially used horse-drawn vehicles, but developments in steam engines made them cheaper to run than horses, and more useful as a source of locomotive power on railways. The Swansea and Mumbles Railway was the first to carry paying passengers, from 1807, and was soon followed by many others, with Parliament passing around one new railway Act per year until 1821. By 1840, numerous railway lines had been laid, forming networks such as that created by George Hudson; the number of rail miles expanded from 1,497 in 1840 to 6,084 by 1850, and horse-drawn passenger coaches became virtually obsolete over long distances.

Use of the steam engine also began to make the horse redundant in farm work. In a letter to ''The Farmer's Magazine'' in 1849, Alderman Kell of Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire, commented that "[enough] ... has been said, although perhaps not mathematically correct, to show that horses are kept at vast expense in comparison with a steam engine that eats only when it works".''The Farmer's Magazine''

Horses remained the primary source of power for agriculture, mining, transport and warfare, until the arrival of the steam engine. The Middleton Railway had been established for industrial use by an Acts of Parliament in the United Kingdom, Act of Parliament in 1785; Parliament also allowed the construction of the Surrey Iron Railway, intended to carry goods, in 1801, and the Oystermouth Railway, later known as the Swansea and Mumbles Railway, in 1804. These initially used horse-drawn vehicles, but developments in steam engines made them cheaper to run than horses, and more useful as a source of locomotive power on railways. The Swansea and Mumbles Railway was the first to carry paying passengers, from 1807, and was soon followed by many others, with Parliament passing around one new railway Act per year until 1821. By 1840, numerous railway lines had been laid, forming networks such as that created by George Hudson; the number of rail miles expanded from 1,497 in 1840 to 6,084 by 1850, and horse-drawn passenger coaches became virtually obsolete over long distances.

Use of the steam engine also began to make the horse redundant in farm work. In a letter to ''The Farmer's Magazine'' in 1849, Alderman Kell of Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire, commented that "[enough] ... has been said, although perhaps not mathematically correct, to show that horses are kept at vast expense in comparison with a steam engine that eats only when it works".''The Farmer's Magazine''

20, 1849, p. 47. With the invention of the portable steam engine in the 1840s, which was promoted by the Royal Agricultural Society of England, Royal Agricultural Society, steam-powered machines could be used on small farms. One man could invest in a portable machine, and recoup the cost by hiring it out for haymaking and harvest; the only use for horses here was to move the machine from one place to another. There were about 3.3 million horses in late Victorian Britain. In 1900 about a million of these were working horses, and in 1914 between 20,000 and 25,000 horses were utilised as cavalry in WWI."1900: The Horse in Transition: The Horse in World War I 1914–1918"

International Museum of the Horse. Retrieved 10 March 2012. Horses and ponies began to be used in Britain's mining pits in the 18th century, to haul "tubs" of coal and ore from the working face to the lifts, in deep mines, or to the surface in shallower mines. Many of these ponies were Shetland pony, Shetlands, as their small size was combined with great strength. A stud farm for the sole purpose of breeding pit pony, ponies for the pits was established in 1870 by colliery owner Frederick Stewart, 4th Marquess of Londonderry, and the Shetland Pony Stud Book Society was formed in 1890 to stop the use of the best stallions in the pits. By 1984, only 55 pit ponies were being used by the National Coal Board in Britain, chiefly at the modern pit in Ellington, Northumberland. A horse called "Robbie", probably the last to work underground in a British coal mine, was retired from a mine at Pant y Gasseg, near Pontypool, in May 1999.

In the World War I, First World War, horses were used in combat for cavalry charges, and they remained the best means for moving scouts, messengers, supply wagons, ambulances, and artillery quickly on the battlefield; the horse could refuel itself to some extent by grazing, and could cope with terrain which was beyond machines of the time. However, this war had a devastating effect on the British horse population. As thousands of animals were drafted for the war effort, some breeds were so reduced in number that they were in danger of disappearing. Many breeds were saved by the dedicated efforts of a few breeders who formed breed societies, tracking down remaining animals and registering them.

Horses and ponies began to be used in Britain's mining pits in the 18th century, to haul "tubs" of coal and ore from the working face to the lifts, in deep mines, or to the surface in shallower mines. Many of these ponies were Shetland pony, Shetlands, as their small size was combined with great strength. A stud farm for the sole purpose of breeding pit pony, ponies for the pits was established in 1870 by colliery owner Frederick Stewart, 4th Marquess of Londonderry, and the Shetland Pony Stud Book Society was formed in 1890 to stop the use of the best stallions in the pits. By 1984, only 55 pit ponies were being used by the National Coal Board in Britain, chiefly at the modern pit in Ellington, Northumberland. A horse called "Robbie", probably the last to work underground in a British coal mine, was retired from a mine at Pant y Gasseg, near Pontypool, in May 1999.

In the World War I, First World War, horses were used in combat for cavalry charges, and they remained the best means for moving scouts, messengers, supply wagons, ambulances, and artillery quickly on the battlefield; the horse could refuel itself to some extent by grazing, and could cope with terrain which was beyond machines of the time. However, this war had a devastating effect on the British horse population. As thousands of animals were drafted for the war effort, some breeds were so reduced in number that they were in danger of disappearing. Many breeds were saved by the dedicated efforts of a few breeders who formed breed societies, tracking down remaining animals and registering them.

Working horses all but disappeared from Britain's streets by the 21st century; among few exceptions are heavy horses pulling brewers'

Working horses all but disappeared from Britain's streets by the 21st century; among few exceptions are heavy horses pulling brewers' "Equestrian"

BBC. 2005. Retrieved 11 March 2012

. sportinglife.com. 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

The known history of the horse in Britain starts with

The known history of the horse in Britain starts with horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

remains found in Pakefield, Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include ...

, dating from 700,000 BC, and in Boxgrove

Boxgrove is a village, ecclesiastical parish and civil parish in the Chichester District of the English county of West Sussex, about north east of the city of Chichester. The village is just south of the A285 road which follows the line of the ...

, West Sussex

West Sussex is a county in South East England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the shire districts of Adur, Arun, Chichester, Horsham, and Mid Sussex, and the boroughs of Crawley and Worthing. Covering an ...

, dating from 500,000 BC. Early humans were active hunters of horses, and finds from the Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gre ...

have been recovered from many sites. At that time, land which now forms the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

was part of a peninsula attached to continental Europe by a low-lying area now known as "Doggerland

Doggerland was an area of land, now submerged beneath the North Sea, that connected Britain to continental Europe. It was flooded by rising sea levels around 6500–6200 BCE. The flooded land is known as the Dogger Littoral. Geological sur ...

", and land animals could migrate freely between what is now island Britain and continental Europe. The domestication of horses, and their use to pull vehicles, had begun in Britain by 2500 BC; by the time of the Roman conquest of Britain

The Roman conquest of Britain refers to the conquest of the island of Britain by occupying Roman forces. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the southern half of Britain by 87 when the Stan ...

, British tribes

The Britons ( *''Pritanī'', la, Britanni), also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were people of Celtic language and culture who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age and into the Middle Ages, at which point the ...

could assemble armies which included thousands of chariot

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&n ...

s.

Horse improvement as a goal, and horse breeding

Horse breeding is reproduction in horses, and particularly the human-directed process of selective breeding of animals, particularly purebred horses of a given breed. Planned matings can be used to produce specifically desired characteristics in ...

as an enterprise, date to medieval times

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

; King John imported a hundred Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

stallion

A stallion is a male horse that has not been gelded ( castrated).

Stallions follow the conformation and phenotype of their breed, but within that standard, the presence of hormones such as testosterone may give stallions a thicker, "cresty" nec ...

s, Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

imported fifty Spanish stallions, and various priories and abbeys owned stud farm

A stud farm or stud in animal husbandry is an establishment for selective breeding of livestock. The word " stud" comes from the Old English ''stod'' meaning "herd of horses, place where horses are kept for breeding". Historically, documentation ...

s. Laws were passed restricting and prohibiting horse exports and for the cull

In biology, culling is the process of segregating organisms from a group according to desired or undesired characteristics. In animal breeding, it is the process of removing or segregating animals from a breeding stock based on a specific tr ...

ing of horses considered undesirable in type. By the 17th century, specific horse breed

A horse breed is a selectively bred population of domesticated horses, often with pedigrees recorded in a breed registry. However, the term is sometimes used in a broader sense to define landrace animals of a common phenotype located within a l ...

s were being recorded as suitable for specific purposes, and new horse-drawn agricultural machinery was being designed. Fast coaches

Coach may refer to:

Guidance/instruction

* Coach (sport), a director of athletes' training and activities

* Coaching, the practice of guiding an individual through a process

** Acting coach, a teacher who trains performers

Transportation

* Coac ...

pulled by teams of horses with Thoroughbred

The Thoroughbred is a horse breed best known for its use in horse racing. Although the word ''thoroughbred'' is sometimes used to refer to any breed of purebred horse, it technically refers only to the Thoroughbred breed. Thoroughbreds are ...

blood could make use of improved roads, and coaching inn

The coaching inn (also coaching house or staging inn) was a vital part of Europe's inland transport infrastructure until the development of the railway, providing a resting point ( layover) for people and horses. The inn served the needs of tr ...

proprietors owned hundreds of horses to support the trade. Steam power took over the role of horses in agriculture from the mid-19th century, but horses continued to be used in warfare for almost another 100 years, as their speed and agility over rough terrain remained unequalled. Working horses had all but disappeared from Britain by the 1980s, and today horses in Britain are kept almost wholly for recreational purposes.

Pleistocene epoch

The earliest horse remains found in the area now covered by Britain and Ireland date to theMiddle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, widely known by its previous designation of Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. Th ...

. Two species of horses have been identified from remains at Pakefield, East Anglia, dating back to 700,000 BC. Spear damage on a horse shoulder bone discovered at Eartham Pit, Boxgrove

Eartham Pit is an internationally important archaeological site north-east of Boxgrove in West Sussex with findings that date to the Lower Palaeolithic. The oldest human remains in Britain have been discovered on the site, fossils of ''Homo heide ...

, dated 500,000 BC, showed that early hominids were hunting horses in the area at that time. The land which now comprises the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

was periodically joined to continental Europe by a land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea leve ...

, extending from approximately the current coast of North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire is the largest ceremonial county (lieutenancy area) in England, covering an area of . Around 40% of the county is covered by national parks, including most of the Yorkshire Dales and the North York Moors. It is one of four co ...

to the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

, most recently until about 9,000 years ago. Dependent on the rise and fall of sea levels associated with advancing and retreating ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gre ...

s, this allowed humans and fauna to migrate between these areas; as the climate fluctuated, hunters could follow their prey, including equids

Equidae (sometimes known as the horse family) is the taxonomic family of horses and related animals, including the extant horses, asses, and zebras, and many other species known only from fossils. All extant species are in the genus '' Equus' ...

.

Although much of Britain from this time is now beneath the sea, remains have been discovered on land that show horses were present, and being hunted, in this period. Significant finds include a horse tooth dating from between 55,000 and 47,000 BC and horse bones dating from between 50,000 and 45,000 BC, recovered from Pin Hole Cave, in the Creswell Crags

Creswell Crags is an enclosed limestone gorge on the border between Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, England, near the villages of Creswell and Whitwell. The cliffs in the ravine contain several caves that were occupied during the last ice age ...

ravine in the North Midlands

The North Midlands is a loosely defined area covering the northern parts of the Midlands in England. It is not one of the ITL regions like the East Midlands or the West Midlands.

A statistical definition in 1881 included the counties of Derbys ...

; further horse remains from the same era have been recovered from Kent's Cavern

Kents Cavern is a cave system in Torquay, Devon, England. It is notable for its archaeological and geological features. The cave system is open to the public and has been a geological Site of Special Scientific Interest since 1952 and a Schedule ...

. In Robin Hood Cave, also in Creswell Crags, a horse tooth was recovered dating from between 32,000 and 24,000 BC; this cave has also preserved one of the earliest examples of prehistoric artwork in Britain – an engraving of a horse, on a piece of horse bone. A goddess figurine carved from horse bone and dating from around 23,000 BC has been recovered from Paviland Cave

The Red Lady of Paviland is an Upper Paleolithic partial skeleton of a male dyed in red ochre and buried in Wales 33,000 BP. The bones were discovered in 1823 by William Buckland in an archaeological dig at Goat's Hole Cave (Paviland cave) – ...

in South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

.

Horse remains dating to the later part of this period – roughly coinciding with the end of the last glacial period – have been found at Farndon Fields, Nottinghamshire, dating from around 12,000 BC. Mother Grundy's Parlour, also in Creswell Crags, contains horse remains showing cut marks indicating that hunting of horses occurred there around 10,000 BC. A study of Victoria Cave in North Yorkshire produced a horse bone showing cut marks dating from about the same time.

Holocene period

TheHolocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

period began around 11,700 years ago and continues to the present. Identified with the current warm period, known as " Marine Isotope Stage 1", or MIS 1, the Holocene is considered an interglacial

An interglacial period (or alternatively interglacial, interglaciation) is a geological interval of warmer global average temperature lasting thousands of years that separates consecutive glacial periods within an ice age. The current Holocene i ...

period in the current Ice Age

The Late Cenozoic Ice Age,National Academy of Sciences - The National Academies Press - Continental Glaciation through Geologic Times https://www.nap.edu/read/11798/chapter/8#80 or Antarctic Glaciation began 33.9 million years ago at the Eocen ...

. Horse remains dating from the Mesolithic

The Mesolithic ( Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymo ...

period, or Middle Stone Age, early in the Holocene, have been found in Britain, though much of Mesolithic Britain now lies under the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

, the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the C ...

and the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

, and material which may include archaeological evidence for the presence of the horse in Britain continues to be washed into the sea, by rivers and coastal erosion

Coastal erosion is the loss or displacement of land, or the long-term removal of sediment and rocks along the coastline due to the action of waves, currents, tides, wind-driven water, waterborne ice, or other impacts of storms. The landwar ...

.

During the Devensian glaciation, the northernmost part of the peninsula from which Britain was formed was covered with

During the Devensian glaciation, the northernmost part of the peninsula from which Britain was formed was covered with glacial ice

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

, and the sea level was about lower than it is today. This glacial ice advanced and retreated several times during this period, and much of what is now the North Sea and the English Channel was an expanse of low-lying tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless mou ...

, which, around 12,000 BC, extended northwards to a point roughly parallel with Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially different boundaries. The Aberdeenshire Council area inclu ...

, in eastern Scotland. In 1998, archaeologist B.J. Coles named this low-lying area "Doggerland

Doggerland was an area of land, now submerged beneath the North Sea, that connected Britain to continental Europe. It was flooded by rising sea levels around 6500–6200 BCE. The flooded land is known as the Dogger Littoral. Geological sur ...

", in which the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

flowed somewhat to the north of its current route, joining the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

to flow west to the Atlantic Ocean along the line of what is now the English Channel. Human hunters roamed this land, which, by about 8000 BC, had a varied coastline of lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into '' coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons ...

s, salt marsh

A salt marsh or saltmarsh, also known as a coastal salt marsh or a tidal marsh, is a coastal ecosystem in the upper coastal intertidal zone between land and open saltwater or brackish water that is regularly flooded by the tides. It is domin ...

es, mudflat

Mudflats or mud flats, also known as tidal flats or, in Ireland, slob or slobs, are coastal wetlands that form in intertidal areas where sediments have been deposited by tides or rivers. A global analysis published in 2019 suggested that tidal f ...

s, beaches, inland streams, rivers, marsh

A marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous rather than woody plant species.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p Marshes can often be found ...

es, and included lakes. It may have been the richest hunting, fowling and fishing ground available to the people of Mesolithic Europe.

Horse remains dating from 10,500–8,000 BC have been recovered from Sewell's Cave, Flixton, Seamer Carr, Uxbridge and Thatcham. Remains dating from around 7,000 BC have been found in Gough's Cave in Cheddar.

Although there is an apparent absence of horse remains between 7000 BC and 3500 BC, there is evidence that wild horses remained in Britain after it became an island separate from Europe by about 5,500 BC. Pre-domestication wild horse

The wild horse (''Equus ferus'') is a species of the genus ''Equus'', which includes as subspecies the modern domesticated horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') as well as the endangered Przewalski's horse (''Equus ferus przewalskii''). The Europea ...

bones have been found in Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

tombs of the Severn-Cotswold type, dating from around 3500 BC.

Domestication in pre-Roman times

Domesticated horses were present in

Domesticated horses were present in Bronze Age Britain

Bronze Age Britain is an era of British history that spanned from until . Lasting for approximately 1,700 years, it was preceded by the era of Neolithic Britain and was in turn followed by the period of Iron Age Britain. Being categorised as ...

from around 2000 BC. Bronze Age horse trappings including snaffle bits have been found which were used in harnessing horses to vehicles; Bronze Age cart

A cart or dray (Australia and New Zealand) is a vehicle designed for transport, using two wheels and normally pulled by one or a pair of draught animals. A handcart is pulled or pushed by one or more people.

It is different from the flatbed ...

wheels have been found at Flag Fen and Blair Drummond

Blair Drummond is a small rural community northwest of Stirling in the Stirling district of Scotland, predominantly located along the A84 road. Lying to the north of the River Forth, the community is within the registration county of Perthshire ...

, the latter dating from around 1255–815 BC, though these may have belonged to vehicles pulled by oxen. Early Bronze Age evidence for horses being ridden is lacking, though bareback riding

Bareback riding is a form of horseback riding without a saddle. It requires skill, balance, and coordination, as the rider does not have any equipment to compensate for errors of balance or skill.

Proponents of bareback riding argue that riding ...

may have involved materials which have not survived or have not been found; but horses were ridden in battle in Britain by the late Bronze Age. Domesticated ponies

A pony is a type of small horse ('' Equus ferus caballus''). Depending on the context, a pony may be a horse that is under an approximate or exact height at the withers, or a small horse with a specific conformation and temperament. Compared ...

were on Dartmoor

Dartmoor is an upland area in southern Devon, England. The moorland and surrounding land has been protected by National Park status since 1951. Dartmoor National Park covers .

The granite which forms the uplands dates from the Carboniferous P ...

by around 1500 BC.

Excavations of Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

sites have recovered horse bones from ritual pits at a temple site near Cambridge, and around twenty Iron Age chariot burial

Chariot burials are tombs in which the deceased was buried together with their chariot, usually including their horses and other possessions. An instance of a person being buried with their horse (without the chariot) is called horse burial.

Fin ...

s have been found, including one of a woman discovered at Wetwang Slack

Wetwang Slack is an Iron Age archaeological site containing remains of the Arras culture and chariot burial tradition of East Yorkshire. Archaeological investigation took place in 2001 and 2002.

The site is in a dry valley on the north side o ...

. The majority of Iron Age chariot burials in Britain are associated with the Arras culture

The Arras culture is an archaeological culture of the Middle Iron Age in East Yorkshire, England. It takes its name from the cemetery site of Arras, at Arras Farm, near Market Weighton, which was discovered in the 19th century. The site spans th ...

, and in most cases the chariots were dismantled before burial. Exceptions are the Ferrybridge and Newbridge chariots, which are the only ones found to have been buried intact. The Newbridge burial has been radiocarbon dated

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

to 520–370 BC, and the Ferrybridge burial is likely to be of similar date.

Towards the end of the Iron Age, there is much evidence for the use of horses in transport and battle, and for extensive trade between the inhabitants of Britain and other cultures. A collection of Iron Age artefacts from Polden Hill in Somerset includes a very large hoard of horse gear, and a rare, cast copper alloy cheekpiece dating from the late, pre-Roman Iron Age was found in St Ewe

St Ewe ( kw, Lannewa) is a civil parish and village in mid-Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, which is believed by hagiographers to have been named after the English moniker of Saint Avoye. The village is situated approximately five miles (8&nbs ...

, Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

. The horse was an important figure in Bronze Age and Iron Age Celtic religion and myth, and is symbolised in the hill figure of the Uffington White Horse

The Uffington White Horse is a prehistoric hill figure, long, formed from deep trenches filled with crushed white chalk. The figure is situated on the upper slopes of White Horse Hill in the English civil parish of Uffington (in the cer ...

, near the Iron Age hill fort of Uffington Castle

Uffington Castle is an early Iron Age (with underlying Bronze Age) univallate hillfort in Oxfordshire, England. It covers about 32,000 square metres and is surrounded by two earth banks separated by a ditch with an entrance in the western end. A ...

in Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primaril ...

.

Roman Britain to the Norman Conquest

By the time of

By the time of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

's attempted invasion of Britain in 55 BC, the inhabitants of Britain included proficient horsemen. Caesar's forces were met by British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

horsemen and war chariots, the chariots outfighting the Gaulish

Gaulish was an ancient Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium, most of Switze ...

horsemen who had accompanied him. Caesar later faced organised resistance led by Cassivellaunus

Cassivellaunus was a historical Celtic Britons, British military leader who led the defence against Caesar's invasions of Britain, Julius Caesar's second expedition to Britain in 54 BC. He led an alliance of tribes against Ancient Rome, Roman for ...

, with over 4,000 war chariots. To the east of the Pennines

The Pennines (), also known as the Pennine Chain or Pennine Hills, are a range of uplands running between three regions of Northern England: North West England on the west, North East England and Yorkshire and the Humber on the east. Common ...

, the Romans also encountered the ''Gabrantovici'', or "horse-riding warriors". The spread and development of horse trappings recovered from this period, such as bits, strap junctions and terrets, have been used to indicate the withdrawal of ruling groups of Britons during the Roman conquest of Britain

The Roman conquest of Britain refers to the conquest of the island of Britain by occupying Roman forces. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the southern half of Britain by 87 when the Stan ...

.

A large amount of horse dung has been found in a well at a Roman fort in Lancaster, Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancas ...

, which was a base for cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

units in the 1st and 2nd centuries. The bones of 28 horses have been found in a Roman well at Dunstable

Dunstable ( ) is a market town and civil parish in Bedfordshire, England, east of the Chiltern Hills, north of London. There are several steep chalk escarpments, most noticeable when approaching Dunstable from the north. Dunstable is t ...

, Bedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council ...

, which was a Roman posting-station on Watling Street

Watling Street is a historic route in England that crosses the River Thames at London and which was used in Classical Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and throughout the Middle Ages. It was used by the ancient Britons and paved as one of the main ...

, where horses would have been kept. These horses had been butchered for horsemeat

Horse meat forms a significant part of the culinary traditions of many countries, particularly in Eurasia. The eight countries that consume the most horse meat consume about 4.3 million horses a year. For the majority of humanity's early existen ...

; but a revival of the cult of the Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foo ...

goddess Epona

In Gallo-Roman religion, Epona was a protector of horses, ponies, donkeys, and mules. She was particularly a goddess of fertility, as shown by her attributes of a patera, cornucopia, ears of grain and the presence of foals in some sculptures ...

, protector of horses, donkeys and mules, may account for horse carcasses buried whole at Dunstable, with "special care". Buried with humans in a 4th–5th century cemetery, these horses represent a belief that Epona protected the dead.

One of the earliest records of British horses being recognised for their quality and exported dates from the Roman era; many British horses were taken to Italy to improve native stock. Some of the earliest evidence of horses used for sport in Britain also dates from Roman times, a chariot-racing arena having been discovered at

One of the earliest records of British horses being recognised for their quality and exported dates from the Roman era; many British horses were taken to Italy to improve native stock. Some of the earliest evidence of horses used for sport in Britain also dates from Roman times, a chariot-racing arena having been discovered at Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colch ...

, in Essex

Essex () is a Ceremonial counties of England, county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the Riv ...

.

From the 5th century, the role of the horse in Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

culture is partly illustrated by the number of words for "horse" in Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

. These distinguish between cart horses (two words), pack horses (two words), riding horses (three words), horses for breeding (three words, male and female), horses suitable for royalty and aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

(five words, of which three were mainly used in poetry), and warhorses (one word). There was no word for "plough horse", and no evidence that horses were used for ploughing

A plough or plow ( US; both ) is a farm tool for loosening or turning the soil before sowing seed or planting. Ploughs were traditionally drawn by oxen and horses, but in modern farms are drawn by tractors. A plough may have a wooden, iron or ...

in Anglo-Saxon times, when this was still done by ox teams; but Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

records a horse used for harrowing, in 1086. Horses were used predominantly for transporting goods and people; numerous English place-names, such as Stadhampton

Stadhampton is a village and civil parish about 7 miles (11 km) southeast of Oxford in South Oxfordshire, England. Stadhampton is close to the River Thame, a tributary of the River Thames. The village was first mentioned by name in 1146, and was ...

, Stoodleigh and Studham

Studham is a village and civil parish in the county of Bedfordshire. It has a population of 1,128. The parish bounds to the south of the Buckinghamshire border, and to the east is the Hertfordshire border. The village lies in the wooded south ...

, refer to the keeping of "studs", in this case "herds", of horses; and Anglo-Saxon stirrup

A stirrup is a light frame or ring that holds the foot of a rider, attached to the saddle by a strap, often called a ''stirrup leather''. Stirrups are usually paired and are used to aid in mounting and as a support while using a riding animal ...

s and spur

A spur is a metal tool designed to be worn in pairs on the heels of riding boots for the purpose of directing a horse or other animal to move forward or laterally while riding. It is usually used to refine the riding aids (commands) and to ba ...

s have been found by archaeologists. Horses were also raced for sport, and a "race-course" in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

is mentioned in a charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the re ...

of King Eadred, dated 949.

There is some evidence that horses were occasionally eaten, perhaps in a hard winter, or ridden until five years of age and then slaughtered for meat; but there are many references in medieval sources indicating that the Anglo-Saxons placed a high value on horses.''Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England''(search "Factoids" for text "horse"). PASE. 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2012. They were often included in the price paid for land and in

bequest

A bequest is property given by will. Historically, the term ''bequest'' was used for personal property given by will and ''deviser'' for real property. Today, the two words are used interchangeably.

The word ''bequeath'' is a verb form for the act ...

s and other gifts, and kings' servants included horse-thegn

In Anglo-Saxon England, thegns were aristocratic landowners of the second rank, below the ealdormen who governed large areas of England. The term was also used in early medieval Scandinavia for a class of retainers. In medieval Scotland, there ...

s, or marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated o ...

s. Numerous horses and horse-breeding establishments were recorded in Domesday Book, though many more horses were probably omitted, given the need for horses for riding and pulling carts. Only 71 smiths are recorded in Domesday Book, but others "must be concealed under the heading of other classes". Six smiths in Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester, England, Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. ...

were obliged to supply 120 horseshoe

A horseshoe is a fabricated product designed to protect a horse hoof from wear. Shoes are attached on the palmar surface (ground side) of the hooves, usually nailed through the insensitive hoof wall that is anatomically akin to the human ...

s each year for the maintenance of horses belonging to warriors.

Horses held religious significance in

Horses held religious significance in Anglo-Saxon paganism

Anglo-Saxon paganism, sometimes termed Anglo-Saxon heathenism, Anglo-Saxon pre-Christian religion, or Anglo-Saxon traditional religion, refers to the religious beliefs and practices followed by the Anglo-Saxons between the 5th and 8th centurie ...

. The 8th century historian Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom ...

, of Jarrow

Jarrow ( or ) is a town in South Tyneside in the county of Tyne and Wear, England. It is east of Newcastle upon Tyne. It is situated on the south bank of the River Tyne, about from the east coast. It is home to the southern portal of the Ty ...

, in Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

, wrote that the first Anglo-Saxon chieftains, in the 5th century, were Hengist and Horsa

Hengist and Horsa are Germanic brothers said to have led the Angles, Saxons and Jutes in their invasion of Britain in the 5th century. Tradition lists Hengist as the first of the Jutish kings of Kent.

Most modern scholarly consensus now rega ...

– Old English words for "stallion

A stallion is a male horse that has not been gelded ( castrated).

Stallions follow the conformation and phenotype of their breed, but within that standard, the presence of hormones such as testosterone may give stallions a thicker, "cresty" nec ...

" and "horse", respectively. Modern scholars regard Hengist and Horsa as horse deities venerated by pagan Anglo-Saxons, euhemerised

Euhemerism () is an approach to the interpretation of mythology in which mythological accounts are presumed to have originated from real historical events or personages. Euhemerism supposes that historical accounts become myths as they are exagge ...

into ancestors of Anglo-Saxon royalty, and stemming from the divine twins

The Divine Twins are youthful horsemen, either gods or demigods, who serve as rescuers and healers in Proto-Indo-European mythology.

Like other Proto-Indo-European divinities, the Divine Twins are not directly attested by archaeological or writt ...

of Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo ...

religion, with cognates in various other Indo-European cultures.

Horses appear frequently in accounts concerning miraculous events in the context of Anglo-Saxon Christianity

In the seventh century the pagan Anglo-Saxons were converted to Christianity ( ang, Crīstendōm) mainly by missionaries sent from Rome. Irish missionaries from Iona, who were proponents of Celtic Christianity, were influential in the conversion o ...

. In the 7th century, a horse is reported to have revealed warm bread and some meat when St Cuthbert

Cuthbert of Lindisfarne ( – 20 March 687) was an Anglo-Saxon saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in the Kingdom of Nor ...

was hungry, by pulling straw from the roof of a hut; and, when Cuthbert was suffering from a diseased knee, he was visited by an angel

In various theistic religious traditions an angel is a supernatural spiritual being who serves God.

Abrahamic religions often depict angels as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity. Other roles ...

on horseback, who helped him to heal his knee. In the 8th century, the Anglo-Saxon Bishop Willibald of Eichstätt

Eichstätt () is a town in the federal state of Bavaria, Germany, and capital of the district of Eichstätt. It is located on the Altmühl river and has a population of around 13,000. Eichstätt is also the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese ...

wrote that, when a source of fresh water was needed for a monastery on the site where St Boniface

Boniface, OSB ( la, Bonifatius; 675 – 5 June 754) was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations o ...

had died, in the kingdom of Frisia, the ground gave way under the forelegs of a horse, and, when the horse was pulled free, a fountain of spring water

A spring is a point of exit at which groundwater from an aquifer flows out on top of Earth's crust ( pedosphere) and becomes surface water. It is a component of the hydrosphere. Springs have long been important for humans as a source of fresh ...

came out of the ground and formed a brook. In the 10th century, King Edmund I is reported to have been saved from death while chasing a deer on horseback when he prayed for forgiveness for his maltreatment of St Dunstan

Saint Dunstan (c. 909 – 19 May 988) was an English bishop. He was successively Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, Bishop of Worcester, Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury, later canonised as a saint. His work restored monastic life in ...

, and thereafter made him abbot of Glastonbury

Glastonbury (, ) is a town and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated at a dry point on the low-lying Somerset Levels, south of Bristol. The town, which is in the Mendip district, had a population of 8,932 in the 2011 census. Glastonbur ...

: the horse stopped at the edge of a cliff, over which the deer and hunting dogs had already fallen. On a later occasion, a horse fell dead under Dunstan when he heard a voice from heaven telling him that King Eadred had died.

Although there is reference to

Although there is reference to Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

horsemen fighting in the 10th century Battle of Sulcoit

The Battle of Sulcoit was fought in the year 968 between the Irish of the Dál gCais, led by Brian Boru, and the Vikings of Limerick, led by Ivar of Limerick. It was a victory for the Dál gCais and marked the end of Norse expansion in Ireland ...

, in Ireland, their primary use for horses in Britain – some of which they captured or seized, and some of which they brought with them – was to facilitate rapid travel. This is a central purpose for which horses were used in Anglo-Saxon England, particularly in warfare, since conflict between the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms was carried out over long distances. In the 7th century, King Penda

Penda (died 15 November 655)Manuscript A of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' gives the year as 655. Bede also gives the year as 655 and specifies a date, 15 November. R. L. Poole (''Studies in Chronology and History'', 1934) put forward the theor ...

of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, y ...

, in central England, took his armies north to Bamburgh

Bamburgh ( ) is a village and civil parish on the coast of Northumberland, England. It had a population of 454 in 2001, decreasing to 414 at the 2011 census.

The village is notable for the nearby Bamburgh Castle, a castle which was the seat o ...

, nearly north of Hadrian's Wall

Hadrian's Wall ( la, Vallum Aelium), also known as the Roman Wall, Picts' Wall, or ''Vallum Hadriani'' in Latin, is a former defensive fortification of the Roman province of Britannia, begun in AD 122 in the reign of the Emperor Hadrian. Ru ...

; and Oswald of Northumbria

Oswald (; c 604 – 5 August 641/642Bede gives the year of Oswald's death as 642, however there is some question as to whether what Bede considered 642 is the same as what would now be considered 642. R. L. Poole (''Studies in Chronology an ...

was killed fighting the Mercians in Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

. These armies probably rode horses to war, and the maintenance of horses was required of many, or perhaps all, who held land under Anglo-Saxon kings. In the 7th century, an Anglo-Saxon warrior was buried with his horse at Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo is the site of two early medieval cemeteries dating from the 6th to 7th centuries near the English town of Woodbridge. Archaeologists have been excavating the area since 1938, when a previously undisturbed ship burial containing ...

; carvings on Anglo-Saxon stone crosses feature warriors on horseback; and 62 "warhorses" are recorded in Domesday Book."Anglo-Saxons fought on foot... and horseback"''Times Higher Education''. 1999. Retrieved 28 February 2012. In the 11th century, Anglo-Saxon warriors on horseback fought successfully against Viking, Welsh and Scottish armies, the latter including Norman allies.

Duke William

''Duke William'' was a ship which served as a troop transport at the Siege of Louisbourg and as a deportation ship in the Île Saint-Jean Campaign of the Expulsion of the Acadians during the Seven Years' War. While ''Duke William'' was transport ...

of Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

shipped horses across the English Channel when he invaded England in 1066, and the outcome of the subsequent Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings nrf, Batâle dé Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066 between the Norman-French army of William, the Duke of Normandy, and an English army under the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, beginning the Norman Conque ...

has been described as "the inevitable victory of stirruped cavalry over helpless infantry". The Battle of Hastings took place in King Harold of England's former earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant " chieftain", particu ...

dom, at the centre of his property and connections; but it came less than three weeks after he had taken an army north and defeated Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

invaders, under King Harald Hardrada, at the Battle of Stamford Bridge

The Battle of Stamford Bridge ( ang, Gefeoht æt Stanfordbrycge) took place at the village of Stamford Bridge, East Riding of Yorkshire, in England, on 25 September 1066, between an English army under King Harold Godwinson and an invading No ...

, near York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

. Harold of England had then been "strong in cavalry". However, that battle had seriously depleted the English king's resources in the south, and, although he re-inforced his army in London on his way to meet the Norman invaders, the force which he brought to the Battle of Hastings was smaller than that which fought at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. No English cavalry was deployed:

Although these mounted troops have been described as cavalry, their weapons and armour were similar to those of foot soldiers, and they did not fight as an organised group in the way that cavalries are normally understood to have done.

Although these mounted troops have been described as cavalry, their weapons and armour were similar to those of foot soldiers, and they did not fight as an organised group in the way that cavalries are normally understood to have done.

Medieval period to the Industrial Age

The improvement of horses for various purposes began in earnest during theMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. King Alexander I of Scotland (c. 1078 – 1124) imported two horses of Eastern origin into Britain, in the first documented import of oriental horse

The term oriental horse refers to the ancient breeds of horses developed in the Middle East, such as the Arabian, Akhal-Teke, Barb, and the now-extinct Turkoman horse. They tend to be thin-skinned, long-legged, slim in build and more physically ...

s. King John of England (1199–1216) imported 100 Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

stallions to continue the improvement of the "great horse" for tournament

A tournament is a competition involving at least three competitors, all participating in a sport or game. More specifically, the term may be used in either of two overlapping senses:

# One or more competitions held at a single venue and concentr ...

and breeding. At the coronation of Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a va ...

and his queen Eleanor of Castile

Eleanor of Castile (1241 – 28 November 1290) was Queen of England as the first wife of Edward I, whom she married as part of a political deal to affirm English sovereignty over Gascony.

The marriage was known to be particularly close, and ...

in 1274, royal and aristocratic guests gave away hundreds of their own horses, to whoever could catch them.

King Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

of England (1312 – 1377) imported 50 Spanish stallions, and three "great horses" from France. He was a passionate supporter of hunting, the tournament, and horse racing

Horse racing is an equestrian performance sport, typically involving two or more horses ridden by jockeys (or sometimes driven without riders) over a set distance for competition. It is one of the most ancient of all sports, as its basic pr ...

, in which Spanish horses known as "running horses" were then primarily involved.

Horse ownership was widespread by the 12th century. Both tenant farmers and landlords were involved in the harrowing of land for arable crops in the relatively new open field system

The open-field system was the prevalent agricultural system in much of Europe during the Middle Ages and lasted into the 20th century in Russia, Iran, and Turkey. Each manor or village had two or three large fields, usually several hundred acr ...

, and employed horses for this work. Horses and carts were increasingly used for transporting farm goods and implements; peasants were obliged to transport such items in their own carts, though the poorest may have had to rely on one horse for all their farm work. The necessity for carting produce revolutionised communication between villages. Horse-breeding as an enterprise continued; in the 14th century, Hexham Priory

Hexham Abbey is a Grade I listed place of Christian worship dedicated to St Andrew, in the town of Hexham, Northumberland, in the North East of England. Originally built in AD 674, the Abbey was built up during the 12th century into its curre ...

had 80 broodmares, the Prior of Durham

The Prior of Durham was the head of the Roman Catholic Durham Cathedral Priory, founded c. 1083 with the move of a previous house from Jarrow. The succession continued until dissolution of the monastery in 1540, when the priory was replaced with ...

owned two stud farms, Rievaulx Abbey owned one, Gilbert d'Umfraville, Earl of Angus

The Mormaer or Earl of Angus was the ruler of the medieval Scottish province of Angus. The title, in the Peerage of Scotland, is held by the Duke of Hamilton, and is used as a courtesy title for the eldest son of the Duke's eldest son.

Histor ...

, in Scotland, had significant grazing lands for mares, and horse-breeding was being carried out both east and west of the Pennines

The Pennines (), also known as the Pennine Chain or Pennine Hills, are a range of uplands running between three regions of Northern England: North West England on the west, North East England and Yorkshire and the Humber on the east. Common ...

.

The introduction of the horse-drawn, four-wheeled wagon in Britain, by the early 15th century at the latest, meant that much heavier loads could be hauled, but brought with it the necessity for horse teams capable of hauling those heavier loads over the poor roads of the time. Where loads were suitable, and the ground was exceptionally poor, pack horses had an advantage over

The introduction of the horse-drawn, four-wheeled wagon in Britain, by the early 15th century at the latest, meant that much heavier loads could be hauled, but brought with it the necessity for horse teams capable of hauling those heavier loads over the poor roads of the time. Where loads were suitable, and the ground was exceptionally poor, pack horses had an advantage over wagon

A wagon or waggon is a heavy four-wheeled vehicle pulled by draught animals or on occasion by humans, used for transporting goods, commodities, agricultural materials, supplies and sometimes people.

Wagons are immediately distinguished from ...

s as they needed fewer handlers, were faster, and could travel over much rougher ground. By that time, post

Post or POST commonly refers to:

*Mail, the postal system, especially in Commonwealth of Nations countries

**An Post, the Irish national postal service

**Canada Post, Canadian postal service

**Deutsche Post, German postal service

**Iraqi Post, Ira ...