History of the United States (1980–1991) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the United States from 1980 until 1991 includes the last year of the

Conservative sentiment was growing, in part due to a disgust at the excesses of the sexual revolution and the failure of liberal policies such as the

Conservative sentiment was growing, in part due to a disgust at the excesses of the sexual revolution and the failure of liberal policies such as the

By early 1982, Reagan's economic program was beset with difficulties as the recession that had begun in 1979 continued. In the short term, the effect of Reaganomics was a soaring

By early 1982, Reagan's economic program was beset with difficulties as the recession that had begun in 1979 continued. In the short term, the effect of Reaganomics was a soaring

referring to active Communist guerrillas operating in the Philippines at the time. The U.S. also had significant strategic military interests in the Philippines, knowing that Marcos's government would not tamper with agreements to maintain U.S. naval bases in the country. Marcos was later ousted in 1986 by the mostly peaceful People Power Revolution, People Power movement, led by

Reagan's vice-president George H. W. Bush easily won the 1988 Republican nomination and defeated Democratic Massachusetts governor

Reagan's vice-president George H. W. Bush easily won the 1988 Republican nomination and defeated Democratic Massachusetts governor

in JSTOR

*Campagna; Anthony S. ''The Economy in the Reagan Years: The Economic Consequences of the Reagan Administrations'' Greenwood Press. 1994 * Camardella, Michele L. ''America in the 1980s'' (2005) For students in middle school. *Collins, Robert M. ''Transforming America: Politics and Culture During the Reagan Years,'' (Columbia University Press; 320 pages; 2007). * Dunlap, Riley E., and Angela G. Mertig, eds. ''American environmentalism: The US environmental movement, 1970-1990'' (2014) *Ehrman, John. ''The Eighties: America in the Age of Reagan.'' (2005) *Ferguson Thomas, and Joel Rogers, ''Right Turn: The Decline of the Democrats and the Future of American Politics'' (1986). * Greene, John Robert. (2nd ed. 2015

excerpt

* Hays, Samuel P. ''A history of environmental politics since 1945'' (2000). * Hayward, Steven F. ''The Age of Reagan: The Conservative Counterrevolution: 1980-1989'' (2010) detailed narrative from conservative perspective * Johns, Andrew L. ed. ''A Companion to Ronald Reagan'' (2015), 34 essays by scholars emphasizing historiograph

excerpt and text search

* Kruse, Kevin M. and Julian E. Zelizer. ''Fault Lines: A History of the United States Since 1974'' (2019), scholarly history

excerpt

*Kyvig, David. ed. ''Reagan and the World'' (1990), scholarly essays on foreign policy *Levy, Peter B. ''Encyclopedia of the Reagan-Bush Years'' (1996), short articles * Martin, Bradford. ''The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan'' (Hill & Wang; 2011) 242 pages; emphasis on efforts by the political left * Meacham, Jon. ''Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush'' (2015

excerpt

*Patterson, James T. ''Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush vs. Gore.'' (2005), standard scholarly synthesis. *Pemberton, William E. ''Exit with Honor: The Life and Presidency of Ronald Reagan'' (1998) short biography by historian * Rossinow, Doug. ''The Reagan Era: A History of the 1980s'' (Columbia University Press, 2015) * Schmertz, Eric J. et al. eds. ''Ronald Reagan's America'' 2 Volumes (1997) articles by scholars and officeholders * Wilentz, Sean. ''The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974-2008'' (2008) detailed narrative by liberal historian

online

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 1 ...

presidency, eight years of the Ronald Reagan administration, and the first three years of the George H. W. Bush presidency, up to the collapse of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Plagued by the Iran hostage crisis

On November 4, 1979, 52 United States diplomats and citizens were held hostage after a group of militarized Iranian college students belonging to the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line, who supported the Iranian Revolution, took over ...

, runaway inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

, and mounting domestic opposition, Carter lost the 1980 United States presidential election to Republican Reagan.

In his first term, Reagan introduced expansionary fiscal policies aimed at stimulating the American economy after a recession in 1981 and 1982, including oil deregulation policies which led to the 1980s oil glut

The 1980s oil glut was a serious surplus of crude oil caused by falling demand following the 1970s energy crisis. The world price of oil had peaked in 1980 at over US$35 per barrel (equivalent to $ per barrel in dollars, when adjusted for inf ...

. He met with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in four summit conferences, culminating with the signing of the INF Treaty

The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty, formally the Treaty Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Elimination of Their Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles; / ДРСМ� ...

. These actions accelerated the end of the Cold War, which occurred in 1989–1991, as typified by the collapse of communism both in Eastern Europe, and in the Soviet Union, and in numerous Third World clients. The economy was in recession in 1981–1983, but recovered and grew sharply after that.

The Iran–Contra affair

The Iran–Contra affair ( fa, ماجرای ایران-کنترا, es, Caso Irán–Contra), often referred to as the Iran–Contra scandal, the McFarlane affair (in Iran), or simply Iran–Contra, was a political scandal in the United States ...

was the most prominent scandal during this time, wherein the Reagan Administration sold weapons to Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, and used the money for CIA aid to pro-American guerrilla Contras in left-leaning Nicaragua.

Changing demographics and the growth of the Sun Belt

A widely discussed demographic phenomenon of the 1970s was the rise of the " Sun Belt", a region encapsulating theSouthwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

, Southeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

, and especially Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

and California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

(surpassing New York as the nation's most populous state in 1964). By 1980, the population of the Sun Belt had risen to exceed that of the industrial regions of the Northeast and Midwest—the Rust Belt

The Rust Belt is a region of the United States that experienced industrial decline starting in the 1950s. The U.S. manufacturing sector as a percentage of the U.S. GDP peaked in 1953 and has been in decline since, impacting certain regions an ...

, which had steadily lost industry and had little population growth. The rise of the Sun Belt was the culmination of changes that began in American society starting in the 1950s, as cheap air travel, automobiles, the interstate system, and the advent of air conditioning

Air conditioning, often abbreviated as A/C or AC, is the process of removing heat from an enclosed space to achieve a more comfortable interior environment (sometimes referred to as 'comfort cooling') and in some cases also strictly controlling ...

all spurred a mass migration south and west. Young, working-age Americans and affluent retirees all flocked to the Sun Belt.

The rise of the Sun Belt has been producing a change in the nation's political climate, strengthening conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

. The boom mentality in this growing region conflicted sharply with the concerns of the Rust Belt

The Rust Belt is a region of the United States that experienced industrial decline starting in the 1950s. The U.S. manufacturing sector as a percentage of the U.S. GDP peaked in 1953 and has been in decline since, impacting certain regions an ...

, populated mainly by those either unable or unwilling to move elsewhere, particularly minority groups and senior citizens. The Northeast and Midwest have remained more committed to social programs and more interested in regulated growth than the wide-open, sprawling states of the South and West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

. Electoral trends in the regions reflect this divergence—the Northeast and Midwest have been increasingly voting for Democratic candidates in federal, state and local elections while the South and West are now the solid base for the Republican Party.

As manufacturing industry gradually moved out of its traditional centers in the Northeast and Midwest, joblessness and poverty increased. The liberal response, typified by Mayor John Lindsay

John Vliet Lindsay (; November 24, 1921 – December 19, 2000) was an American politician and lawyer. During his political career, Lindsay was a U.S. congressman, mayor of New York City, and candidate for U.S. president. He was also a regular ...

of New York City was to dramatically increase welfare services and education, as well as public employment and public salaries, at a time when the tax base was shrinking. New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

barely averted bankruptcy in 1975; it was rescued using state and federal money, along with strict state control of its budget.

Meanwhile, conservatives, based in the suburbs, the rural areas, and the Sunbelt railed against what they identified as the failures of liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

social programs, as well as their enormous expenses. This was a potent theme in the 1980 presidential race and the 1994 mid-term elections, when the Republicans captured the House of Representatives after 40 years of Democratic control.

The liberal leaders of the 1960s, characteristic of the era of the Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Universit ...

and the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

, gave way to conservative urban politicians in the 1970s across the country, such as New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

's Mayor, Ed Koch

Edward Irving Koch ( ; December 12, 1924February 1, 2013) was an American politician, lawyer, political commentator, film critic, and television personality. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1969 to 1977 and was ma ...

, a conservative Democrat.

Reagan Revolution

Rejection of U.S./Soviet détente

The 1970s inflicted damaging blows to the American self-confidence. TheVietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

and the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's contin ...

shattered confidence in the presidency. International frustrations, including the fall of South Vietnam in 1975, the Iran hostage crisis

On November 4, 1979, 52 United States diplomats and citizens were held hostage after a group of militarized Iranian college students belonging to the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line, who supported the Iranian Revolution, took over ...

in 1979, the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, the growth of international terrorism, and the acceleration of the arms race raised fears over the country's ability to control international affairs. The energy crisis, high unemployment, and very high inflation and escalating interest rates made economic planning difficult and raised fundamental questions over the future of American prosperity.

American "malaise", a term that caught on following Carter's 1979 "crisis of confidence" speech, in the late 1970s and early 1980s was not unfounded as the nation seemed to be losing its self-confidence.

Under the rule of Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and ...

the Soviet economy was falling behind—it was decades behind in computers, for example—and was kept alive because of lucrative oil exports. Meanwhile, détente with the Soviets collapsed as the communists made gains across the Third World. Most dramatic was the victory in Vietnam in 1975 when North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; vi, Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa), was a socialist state supported by the Soviet Union (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia that existed f ...

invaded and conquered South Vietnam; American forces were involved only to rescue American supporters. Nearly a million refugees fled; most who survived came to the U.S. Other Communist movements, backed by Moscow or Beijing, were spreading rapidly across Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America. And the Soviet Union seemed committed to the Brezhnev Doctrine

The Brezhnev Doctrine was a Soviet foreign policy that proclaimed any threat to socialist rule in any state of the Soviet Bloc in Central and Eastern Europe was a threat to them all, and therefore justified the intervention of fellow socialist st ...

, ending the 1970s by sending troops to Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

in a move roundly denounced by the West and Muslim countries.

Reacting to all these perceptions of American decline internationally and domestically, a group of academics, journalists, politicians, and policymakers, labeled by many as "new conservatives" or "neoconservatives

Neoconservatism is a political movement that began in the United States during the 1960s among liberal hawks who became disenchanted with the increasingly pacifist foreign policy of the Democratic Party and with the growing New Left and cou ...

", since many of them were still Democrats, rebelled against the Democratic Party's leftward drift on defense issues in the 1970s (especially after the nomination of George McGovern in 1972), and also blamed liberal Democrats for the nation's weakened geopolitical stance. Many clustered around Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson

Henry Martin "Scoop" Jackson (May 31, 1912 – September 1, 1983) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a U.S. representative (1941–1953) and U.S. senator (1953–1983) from the state of Washington. A Cold War liberal and an ...

, a Democrat, but they later aligned themselves with Ronald Reagan and the Republicans, who promised to confront pro-Soviet Communist expansion. Generally they were anti-communist Democrats and opposed to the welfare programs of the Great Society. But their main targets were the old policies of containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''cordon sanitaire'', which wa ...

of communism and ''Détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduce ...

'' with the Soviet Union. They wanted rollback

In political science, rollback is the strategy of forcing a change in the major policies of a state, usually by replacing its ruling regime. It contrasts with containment, which means preventing the expansion of that state; and with détente, w ...

and the peaceful end of the Communist threat rather than aimless negotiations, diplomacy, and arms control.

Led by Norman Podhoretz, the neoconservatives attacked the foreign policy orthodoxy in the Cold War as " appeasement", an allusion to Neville Chamberlain's negotiations at Munich in 1938. They regarded concessions to relatively weak enemies of the United States as "appeasement" of "evil", attacked ''détente'', opposed most-favored nation trade status for the Soviet Union, and supported unilateral American intervention in the Third World as a means of boosting U.S. leverage over international affairs. Before the election of Reagan, the neoconservatives, gaining in influence, sought to stem the antiwar sentiments caused by the U.S. defeats in Vietnam and the massive casualties in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainlan ...

that the war induced.

During the 1970s, Jeane Kirkpatrick

Jeane Duane Kirkpatrick (née Jordan; November 19, 1926December 7, 2006) was an American diplomat and political scientist who played a major role in the foreign policy of the Ronald Reagan administration. An ardent anticommunist, she was a lo ...

, a political scientist and later U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

under Ronald Reagan, increasingly criticized the Democratic Party. Kirkpatrick became a convert to the ideas of the new conservatism of once liberal Democratic academics. She drew a distinction between authoritarian dictators, who she believed were capable of embracing democracy and who were, not coincidentally, allies of the United States, and Communist totalitarian dictators, who she viewed as unyielding and incapable of change.

The 1980s thus began on a thoroughly grim note. Gripped by the worst economy since the 1930s, the automobile and steel industries in serious trouble, the ongoing Iranian Hostage Crisis, and the U.S. seemingly unable to respond to growing Soviet adventurism around the globe, it came as a small measure of good feeling when the amateur U.S. Olympic hockey team defeated their professional Soviet counterparts in the Miracle on Ice.

Ronald Reagan and the elections of 1980

Conservative sentiment was growing, in part due to a disgust at the excesses of the sexual revolution and the failure of liberal policies such as the

Conservative sentiment was growing, in part due to a disgust at the excesses of the sexual revolution and the failure of liberal policies such as the War on Poverty

The war on poverty is the unofficial name for legislation first introduced by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during his State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. This legislation was proposed by Johnson in response to a national ...

to deliver on their promises. President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 1 ...

's prospects for reelection in the U.S. presidential election of 1980 were strengthened when he easily beat back a primary challenge by liberal icon Senator Edward Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

. Against the backdrop of economic stagflation

In economics, stagflation or recession-inflation is a situation in which the inflation rate is high or increasing, the economic growth rate slows, and unemployment remains steadily high. It presents a dilemma for economic policy, since actio ...

and perceived American weakness against the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

abroad, Ronald Reagan, former governor of California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, won the Republican nomination in 1980 by winning most of the primaries. After failing to reach an unprecedented deal with Ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

, who would be a sort of co-president, Reagan picked his chief primary rival, George H. W. Bush, as the vice-presidential nominee. During the campaign, Reagan relied on Jeane Kirkpatrick

Jeane Duane Kirkpatrick (née Jordan; November 19, 1926December 7, 2006) was an American diplomat and political scientist who played a major role in the foreign policy of the Ronald Reagan administration. An ardent anticommunist, she was a lo ...

as his foreign policy adviser to identify Carter's vulnerabilities on foreign policy.

Reagan promised to rebuild the U.S. military, which had sharply declined in strength and morale after the Vietnam War, and restore American power and prestige on the international front. He also promised an end to "big government" and to restore economic health by use of supply-side economics.

Supply-side economists were against the welfare state built up by the Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Universit ...

. They asserted that the woes of the U.S. economy were in large part a result of excessive taxation, which "crowded out" money away from private investors and thus stifled economic growth. The solution, they argued, was to cut taxes across the board, particularly in the upper income brackets, in order to encourage private investment. They also aimed to reduce government spending on welfare

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

and social services geared toward the poorer sectors of society which had built up during the 1960s.

The public, particularly the middle class in the Sun Belt region, agreed with Reagan's proposals, and voted for him in 1980. Critics charged that Reagan was insensitive to the plight of the poor, and that the economic troubles of the 1970s were beyond any president's ability to control or reverse.

The presidential election of 1980 was a key turning point in American politics. It signaled the new electoral power of the suburbs and the Sun Belt, with the Religious Right for the first time a major factor. Moreover, it was a watershed ushering out the commitment to government anti-poverty programs and affirmative action characteristic of the Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Universit ...

. It also signaled a commitment to a hawkish foreign policy.

A third-party candidacy by Representative John B. Anderson of Illinois, a moderate Republican, did poorly. The major issues of the campaign were the economic stagflation, threats to national security, the Iranian hostage crisis

On November 4, 1979, 52 United States diplomats and citizens were held hostage after a group of militarized Iranian college students belonging to the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line, who supported the Iranian Revolution, took over ...

, and the general malaise that seemed to indicate America's great days were over. Carter seemed unable to control inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

and had failed in his rescue effort of the hostages in Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

. Carter dropped his détente-oriented advisers and moved sharply to the right against the Soviets, but Reagan said it was too little, too late.

Reagan won a landslide victory with 489 votes in the electoral college to Carter's 49. Republicans defeated twelve Democratic senators to regain control of the Senate for the first time in 25 years. Reagan received 43,904,153 votes in the election (50.7% of total votes cast), and Carter, 35,483,883 (41.0%). John B. Anderson won 5,720,060 (6.6%) popular votes.

Reagan administration

After years of unstinting praise from the right, and unrelenting criticism from the left, historian David Henry finds that by 2010 a consensus had emerged among scholars that Reagan revived conservatism and turned the nation to the right by demonstrating a "pragmatic conservatism" that promoted ideology within the constraints imposed by the divided political system. Furthermore, says Henry, the consensus agrees that he revived faith in the presidency and American self-confidence, and contributed critically to ending the Cold War. Reagan's approach to the presidency was somewhat of a departure from his predecessors; he delegated a great deal of work to his subordinates, letting them handle most of the government's day-to-day affairs. As an executive, Reagan framed broad themes and made a strong personal connection to voters. He used very strong aides especially chief of staffJames Baker

James Addison Baker III (born April 28, 1930) is an American attorney, diplomat and statesman. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 10th White House Chief of Staff and 67th United States Secretary of the Treasury under President ...

(Ford's campaign manager), and Michael Deaver

Michael Keith Deaver (April 11, 1938 – August 18, 2007) was a member of President Ronald Reagan's White House staff serving as White House Deputy Chief of Staff under James Baker III and Donald Regan from January 1981 until May 1985.

Early ...

as deputy chief of staff, and Edwin Meese as White House counsel, as well as David Stockman

David Alan Stockman (born November 10, 1946) is an American politician and former businessman who was a Republican U.S. Representative from the state of Michigan (1977–1981) and the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (1981–1985 ...

at the Bureau of the Budget and his own campaign manager Bill Casey

William D. Casey (born February 19, 1945) is a Canadian politician from Nova Scotia who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of Canada. First elected as a Progressive Conservative in 1988, he later sat as Conservative ...

at the CIA.

On March 30, 1981, Reagan was shot in Washington by a disturbed nonpolitical man. He recovered fully, with opponents silenced in the meanwhile.

Reagan stunned the nation by appointing the first woman to the Supreme Court, Sandra Day O'Connor in 1981. He promoted conservative leader William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist ( ; October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American attorney and jurist who served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 33 years, first as an associate justice from 1972 to 1986 and then as the 16th chief justice from ...

to Chief Justice in 1986, with arch-conservative Antonin Scalia taking Rehnquist's slot. His fourth appointment in 1987 proved controversial, as the initial choice had to withdraw (he smoked marijuana in college), and the Senate rejected Robert Bork

Robert Heron Bork (March 1, 1927 – December 19, 2012) was an American jurist who served as the solicitor general of the United States from 1973 to 1977. A professor at Yale Law School by occupation, he later served as a judge on the U.S. Cour ...

. Reagan finally won approval for Anthony Kennedy

Anthony McLeod Kennedy (born July 23, 1936) is an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1988 until his retirement in 2018. He was nominated to the court in 1987 by Presid ...

.

Reaganomics and the 1981 federal budget

Ronald Reagan promised an economic revival that would affect all sectors of the population. He proposed to achieve this goal by cutting taxes and reducing the size and scope of federal programs. Critics of his plan charged that the tax cuts would reduce revenues, leading to large federal deficits, which would lead in turn to higher interest rates, stifling any economic benefits. Reagan and his supporters, drawing on the theories of supply-side economics, claimed that the tax cuts would increase revenues through economic growth, allowing the federal government to balance its budget for the first time since 1969. Reagan's 1981 economic legislation, however, was a mixture of rival programs to satisfy all his conservative constituencies (monetarists, cold warriors, middle-class swing voters, and the affluent). Monetarists were placated by tight controls of themoney supply

In macroeconomics, the money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of currency held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include currency in circul ...

; cold warriors, especially neoconservatives like Kirkpatrick, won large increases in the defense budget; wealthy taxpayers won sweeping three-year tax rate reductions on both individual (marginal rates would eventually come down to 50% from 70%) and corporate taxes; and the middle class saw that its pensions and entitlements would not be targeted. Reagan declared spending cuts for the Social Security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

budget, which accounted for almost half of government spending, off limits due to fears over an electoral backlash, but the administration was hard pressed to explain how his program of sweeping tax cuts and large defense spending would not increase the deficit.

Budget Director David Stockman

David Alan Stockman (born November 10, 1946) is an American politician and former businessman who was a Republican U.S. Representative from the state of Michigan (1977–1981) and the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (1981–1985 ...

raced to put Reagan's program through Congress within the administration's deadline of forty days. Stockman had no doubt that spending cuts were needed, and slashed expenditures across the board (with the exception of defense expenditures) by some $40 billion; and when figures did not add up, he resorted to the "magic asterisk"—which signified "future savings to be identified". He would later say that the program was rushed through too quickly and not given enough thought. Appeals from constituencies threatened by the loss of social services were ineffectual; the budget cuts passed through the Congress with relative ease.

The recession of 1982

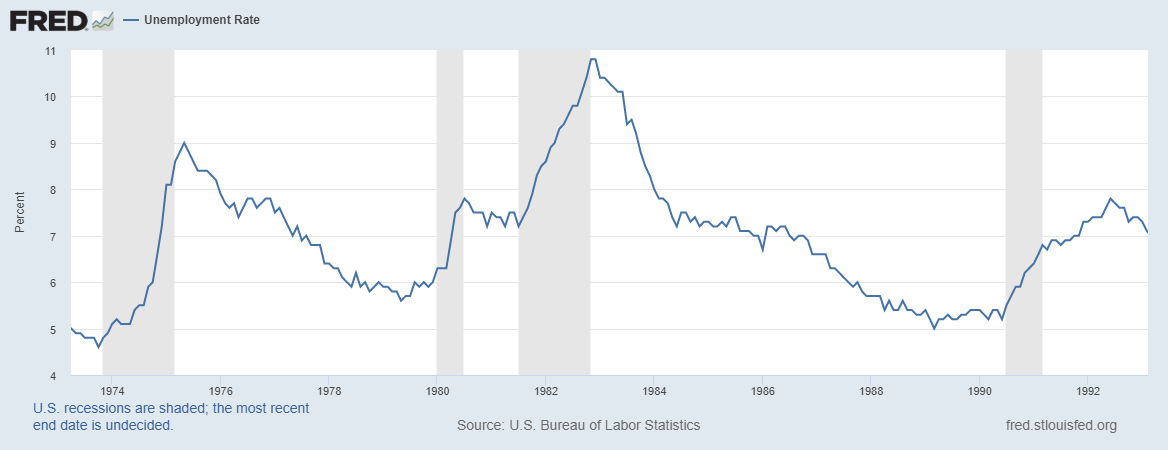

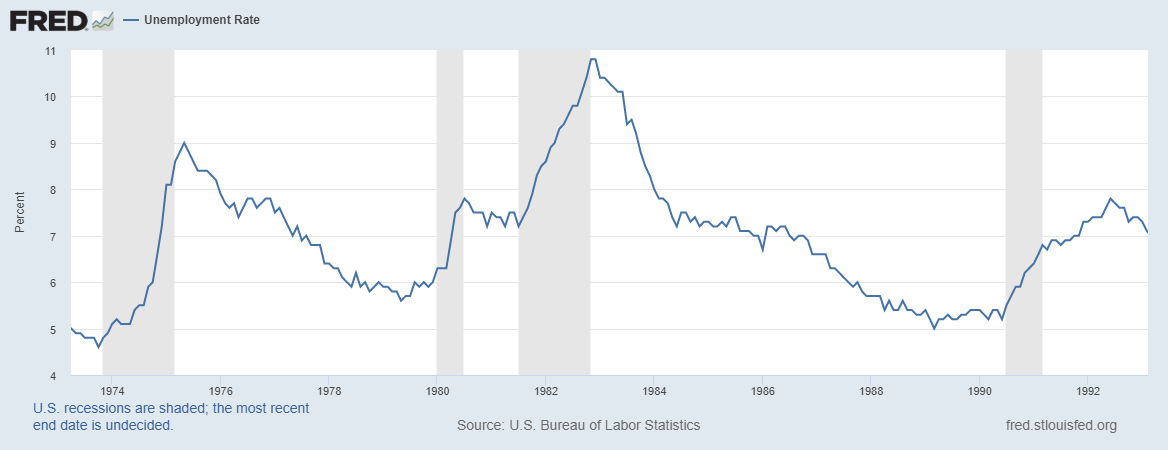

By early 1982, Reagan's economic program was beset with difficulties as the recession that had begun in 1979 continued. In the short term, the effect of Reaganomics was a soaring

By early 1982, Reagan's economic program was beset with difficulties as the recession that had begun in 1979 continued. In the short term, the effect of Reaganomics was a soaring budget deficit

Within the budgetary process, deficit spending is the amount by which spending exceeds revenue over a particular period of time, also called simply deficit, or budget deficit; the opposite of budget surplus. The term may be applied to the budget ...

. Government borrowing, along with the tightening of the money supply, resulted in sky high interest rate

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, ...

s (briefly hovering around 20 percent) and a serious recession with 10-percent unemployment in 1982. Some regions of the "Rust Belt

The Rust Belt is a region of the United States that experienced industrial decline starting in the 1950s. The U.S. manufacturing sector as a percentage of the U.S. GDP peaked in 1953 and has been in decline since, impacting certain regions an ...

" (the industrial Midwest and Northeast) descended into virtual depression conditions as steel mills and other industries closed. Many family farms in the Midwest and elsewhere were ruined by high interest rates and sold off to large agribusinesses.

Reagan allowed the Federal Reserve to drastically reduce the money supply to cure inflation, but it resulted in the recession deepening temporarily. His approval ratings plummeted in the worst months of the recession of 1982. Democrats swept the mid-term elections, making up for their losses in the previous election cycle. At the time, critics often accused Reagan of being out of touch. His Budget Director David Stockman, an ardent fiscal conservative, wrote, "I knew the Reagan Revolution was impossible--it was a metaphor with no anchor in political and economic reality."

Unemployment reached a peak of 11% in late 1982, after which recovery began. A factor in the recovery from the worst periods of 1982-83 was the radical drop in oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

prices due to increased production levels of the mid-1980s, which ended inflationary pressures on fuel prices. The virtual collapse of the OPEC cartel enabled the administration to alter its tight money policies, to the consternation of conservative monetarist economists, who began pressing for a reduction of interest rate

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, ...

s and an expansion of the money supply, in effect subordinating concern about inflation (which now seemed under control) to concern about unemployment and declining investment.

By the middle of 1983, unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refere ...

fell from 11 percent in 1982 to 8.2 percent. GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjective nature this measure is ofte ...

growth was 3.3 percent, the highest since the mid-1970s. Inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

was below 5 percent. When the economy recovered, Ronald Reagan declared it was Morning in America. Housing starts boomed, the automobile industry recovered its vitality, and consumer spending achieved new heights. Blue-collar workers were, however, mostly left behind in the economic boom years of the Reagan Administration, and the old factory jobs that had once offered high wages to even unskilled workers no longer existed.

Reagan went on to defeat Walter Mondale

Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale (January 5, 1928 – April 19, 2021) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 42nd vice president of the United States from 1977 to 1981 under President Jimmy Carter. A U.S. senator from Minnesota ...

in the 1984 presidential election by a massive 49 out of 50 state landslide.

Rising deficits

Following the economic recovery that began in 1983, the medium-term fiscal effect of Reaganomics was a soaring budget deficit as spending continually exceeded revenue due to tax cuts and increased defense spending. Military budgets rose while tax revenues, despite having increased as compared to the stagnant late 1970s and early 1980s, failed to make up for the spiraling cost. The 1981 tax cuts, some of the largest in U.S. history, also eroded the revenue base of the federal government in the short-term. The massive increase in military spending (about $1.6 trillion over five years) far exceeded cuts in social spending, despite wrenching impact of such cuts spending geared toward some of the poorest segments of society. Even so, by the end of 1985, funding for domestic programs had been cut nearly as far as Congress could tolerate. In this context, the deficit rose from $60 billion in 1980 to a peak of $220 billion in 1986 (well over 5% of GDP). Over this period, national debt more than doubled from $749 billion to $1.746 trillion. Since U.S. saving rates were very low (roughly one-third of Japan's,) the deficit was mostly covered by borrowing from abroad, turning the United States within a few years from the world's greatest creditor nation to the world's greatest debtor. Not only was this damaging to America's status, it was also a profound shift in the postwar international financial system, which had relied on the export of U.S. capital. In addition, the media and entertainment industry during the 1980s glamorized the stock market and financial sector (e.g. the 1987 movie Wall Street), causing many young people to pursue careers as brokers, investors, or bankers instead of manufacturing and making it unlikely that any of the lost industrial base would be restored any time soon. The deficits were keeping interest rates high (although lower than the 20% peak levels earlier in the administration due to a respite in the administration's tight money policies), and threatening to push them higher. The government was thus forced to borrow so much money to pay its bills that it was driving up the price of borrowing. Although supply-siders promised increased investment as a result of top-rate and corporate tax cuts, growth and investment suffered for now in the context of high interest rates. In October 1987, a sudden and alarming stock market crash took place, but the Federal Reserve responded by increasing the money supply and averted what could have been another Great Depression. Perhaps more alarmingly, Reagan-era deficits were keeping the U.S. dollar overvalued. With such a high demand for dollars (due in large measure to government borrowing), the dollar achieved an alarming strength against other major currencies. As the dollar soared in value, American exports became increasingly uncompetitive, with Japan as the leading beneficiary. The high value of the dollar made it difficult for foreigners to buy American goods and encouraged Americans to buy imports, coming at a high price to the industrial export sector. Steel and other heavy industries declined due to excessive demands by labor unions and outdated technology that made them unable to compete with Japanese imports. The consumer electronics industry (which had begun declining in the 1970s) was one of the worst victims of dumping and other unfair Japanese trade practices. American consumer electronics also suffered from poor quality and a relative lack of technical innovation compared to Japanese electronics, in part because the Cold War had caused most American scientific and engineering effort to go into the defense sector rather than the consumer one. By the end of the decade, it had virtually ceased to exist. On the bright side, the upstart computer industry flourished during the 1980s. The U.S.balance of trade

The balance of trade, commercial balance, or net exports (sometimes symbolized as NX), is the difference between the monetary value of a nation's exports and imports over a certain time period. Sometimes a distinction is made between a balance ...

grew increasingly unfavorable; the trade deficit grew from $20 billion to well over $100 billion. Thus, American industries such as automobile

A car or automobile is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of ''cars'' say that they run primarily on roads, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport people instead of goods.

The year 1886 is regarde ...

s and steel, faced renewed competition abroad and within the domestic market as well. The auto industry was given breathing space after the Reagan administration imposed voluntary import restraints on Japanese manufacturers (allowing them to sell a maximum of 1.3 million vehicles in the U.S. per year) and imposed a 25% tariff on all imported trucks (a lighter 3% tariff was put on passenger cars). The Japanese responded by opening assembly plants in the U.S. to get around this, and in doing so were able to say that they were providing Americans with jobs. The VIR was repealed in 1985 after auto sales were booming again, but the tariffs remain in effect to this day. With the event of CAFE regulations, small cars came to dominate in the 1980s, and much like with electronics, Japanese makes bested American ones in terms of build quality and technical sophistication.

The enormous deficits were in large measure holdovers from Lyndon Johnson's commitment to both "guns and butter" (the Vietnam War and the Great Society) and the growing competition from other G7 nations after their postwar reconstruction, but it was the Reagan administration that chose to let the deficits develop.

Reagan asked Congress for a line-item veto which would allow him to lower the deficits by cutting spending that he thought was wasteful, but he did not receive it. He also called for a balanced budget amendment which would mandate that the federal government spends no more money than it takes in, which never materialized.

Reagan and the world

Foreign policy: Third World

With Reagan's promises to restore the nation's military strength, the 1980s saw massive increases in military spending, amounting to about $1.6 trillion over five years. A new arms race would develop as superpower relations deteriorated to a level not seen since the Kennedy Administration a generation earlier. Reagan's foreign policy was generally considered more successful and well thought out than his domestic. He favored a hawkish approach to the Cold War, especially in theThird World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

arena of superpower competition. In the wake of the Vietnam debacle, however, Americans were increasingly skeptical of bearing the economic and financial cost of large troop commitments. The administration sought to overcome this by backing the relatively cheap strategy of specially trained counterinsurgencies or "low-intensity conflicts" rather than large-scale campaigns like Korea and Vietnam, which were enormously costly both in money and human life.

The Arab–Israeli conflict

The Arab–Israeli conflict is an ongoing intercommunal phenomenon involving political tension, military conflicts, and other disputes between Arab countries and Israel, which escalated during the 20th century, but had mostly faded out by the ...

was another impetus for military action. Israel invaded Lebanon to destroy the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). But in the wake of the 1982 Sabra and Shatila Massacre

The Sabra and Shatila massacre (also known as the Sabra and Chatila massacre) was the killing of between 460 and 3,500 civilians, mostly Palestinians and Lebanese Shiites, by the militia of the Lebanese Forces, a Maronite Christian Lebanese ...

, which provoked a political crisis in Israel and international embarrassment, U.S. forces moved into Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

to encourage Israeli withdrawal. Previously, the administration stood by Israel's invasion of Lebanon in mid-1982 to maintain the support of Israel on one hand, but also to quell the influence of Israel's pro-Soviet enemy Syria in Lebanon. However, U.S. intervention in the multi-sided Lebanese civil war had disastrous consequences. On October 23, 1983, the Marine Barracks Bombing killed 241 American troops. Shortly afterward, the U.S. withdrew its remaining 1,600 soldiers.

In Operation Urgent Fury the United States for the first time invaded and successfully rolled back a Communist regime. On October 19, the small island nation of Grenada had undergone a coup d'état by Bernard Coard, a staunch Marxist–Leninist seeking to strengthen the country's existing ties with Cuba, the Soviet Union, and other Communist states

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Comint ...

. The prime minister was killed and insurgents had orders to shoot on sight. Over 1,000 Americans were on the island, mostly medical students and their families, and the government could not guarantee their security. The Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

The Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS; French: ''Organisation des États de la Caraïbe orientale'', OECO) is an inter-governmental organisation dedicated to economic harmonisation and integration, protection of human and legal ri ...

, the regional security association of neighboring states led by Prime Minister Eugenia Charles of Dominica officially called on the United States for protection. In a short campaign launched Oct. 25, fought primarily against armed Cuban construction workers, the U.S. military invaded and took control, and democracy was restored to Grenada.

Reagan launched an air strike against Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

after it was found to have connections to a bombing in Berlin which killed two American soldiers.

The Reagan administration also supplied funds and weapons to heavily militarily-influenced governments in El Salvador beginning in 1980 and Honduras, and to a lesser extent in Guatemala, which was ruled by right-wing military autocrat General Efraín Ríos Montt

José Efraín Ríos Montt (; 16 June 1926 – 1 April 2018) was a Guatemalan military officer and politician who served as ''de facto'' President of Guatemala in 1982–83. His brief tenure as chief executive was one of the bloodiest periods i ...

from 1982–83. It reversed ex-President Jimmy Carter's official condemnation of the Argentine junta for human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

abuses and allowed the CIA to collaborate with Argentine intelligence in funding the Contras. Central America was the administration's primary concern, especially El Salvador and Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

, where the Sandinista

The Sandinista National Liberation Front ( es, Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, FSLN) is a socialist political party in Nicaragua. Its members are called Sandinistas () in both English and Spanish. The party is named after Augusto C� ...

revolution brought down the formerly U.S.-backed Somoza family

The Somoza family ( es, Familia Somoza) is a former political family that ruled Nicaragua for forty-three years from 1936 to 1979. Their family dictatorship was founded by Anastasio Somoza García and was continued by his two sons Luis Somoza ...

rule. The two countries had been historically dominated by multinational corporation

A multinational company (MNC), also referred to as a multinational enterprise (MNE), a transnational enterprise (TNE), a transnational corporation (TNC), an international corporation or a stateless corporation with subtle but contrasting senses, i ...

s and wealthy landowning oligarchs

Oligarch may refer to:

Authority

* Oligarch, a member of an oligarchy, a power structure where control resides in a small number of people

* Oligarch (Kingdom of Hungary), late 13th–14th centuries

* Business oligarch, wealthy and influential bu ...

while most of their population remained in poverty; as a result, predominantly Marxist revolutionary leaders had won increasing support from the peasantry in both nations.

In 1982 the CIA, with assistance from the Argentine national intelligence agency, organized and financed right-wing paramilitaries in Nicaragua, known as the Contras. The tracing of secret funds for this scheme led to the revelations of the Iran–Contra affair

The Iran–Contra affair ( fa, ماجرای ایران-کنترا, es, Caso Irán–Contra), often referred to as the Iran–Contra scandal, the McFarlane affair (in Iran), or simply Iran–Contra, was a political scandal in the United States ...

. In 1985 Reagan authorized the sale of arms in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

in an unsuccessful effort to free U.S. hostages in Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

; he later professed ignorance that subordinates were illegally diverting the proceeds to the Contras, a matter for which Marine Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North

Oliver Laurence North (born October 7, 1943) is an American political commentator, television host, military historian, author, and retired United States Marine Corps lieutenant colonel.

A veteran of the Vietnam War, North was a National Secu ...

, an aide to National Security Advisor John M. Poindexter, took much of the blame. Reagan's approval ratings plummeted in 1986 as a result of the scandal, and many Americans began to seriously question his judgement. While the president's popularity improved in his final two years, he would never again enjoy the support he had had in 1985. Predictably, the Democrats regained control of Congress in the 1986 midterm elections. Oliver North meanwhile achieved a brief celebrity status in 1987 during his testimonies before Congress.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the Reagan administration, with help from apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

, also attempted to topple the substantially Cuban and Soviet-backed Marxist–Leninist FRELIMO

FRELIMO (; from the Portuguese , ) is a democratic socialist political party in Mozambique. It is the dominant party in Mozambique and has won a majority of the seats in the Assembly of the Republic in every election since the country's firs ...

and MPLA

The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, abbr. MPLA), for some years called the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Labour Party (), is an Angolan left-wing, social dem ...

dictatorships of Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

and Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

, respectively, during those countries' civil wars. The administration intervened on the side of insurgent groups RENAMO

RENAMO (from the Portuguese , ) is a Mozambican political party and militant group. The party was founded with the active sponsorship of the Rhodesian Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) in May 1977 from anti-communist dissidents oppose ...

in Mozambique and UNITA

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola ( pt, União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola, abbr. UNITA) is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the Popular Movement for ...

in Angola, supplying each group with covert military and humanitarian aid.

In Afghanistan, Reagan massively stepped up military and humanitarian aid for mujahideen fighters against the Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

proxy government there, providing them with Stinger

A stinger (or sting) is a sharp organ found in various animals (typically insects and other arthropods) capable of injecting venom, usually by piercing the epidermis of another animal.

An insect sting is complicated by its introduction of ve ...

anti-aircraft missiles. U.S. allies Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

also provided the rebels with significant assistance. General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev reduced and eventually ended his country's commitment to Afghanistan as Soviet troops there were bogged down in guerrilla war.

Reagan also expressed opposition to the Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

ese-installed Communist regime of Heng Samrin (and later, Hun Sen

Hun Sen (; km, ហ៊ុន សែន, ; born 5 August 1952) is a Cambodian politician and former military commander who has served as the prime minister of Cambodia since 1985. He is the longest-serving head of government of Cambodia, and ...

) in Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

, which had ousted the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime after Vietnam invaded the country. The administration approved military and humanitarian aid to the republican KPNLF and royalist Funcinpec

The National United Front for an Independent, Neutral, Peaceful and Cooperative Cambodia,; french: Front uni national pour un Cambodge indépendant, neutre, pacifique et coopératif commonly referred to as FUNCINPEC,, ; is a royalist politic ...

insurgents. The Reagan administration also supported continued UN recognition of the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea

The Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK; km, រដ្ឋាភិបាលចំរុះកម្ពុជាប្រជាធិបតេយ្យ, ''Roathaphibal Chamroh Kampuchea Pracheathipatai''), renamed in 1990 to the N ...

(a tripartite rebel alliance of the KPNLF, Funcinpec, and the Khmer Rouge) over the Vietnamese-backed People's Republic of Kampuchea

The People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK), UNGEGN: , ALA-LC: ; vi, Cộng hòa Nhân dân Campuchia was a partially recognised state in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as So ...

regime. Reagan also continued American support for the autocratic Philippine

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

President Ferdinand Marcos, an ardent anti-Communist. In a 1984 presidential debate sponsored by the League of Women Voters, he explained his administration's support of Marcos by stating, "I know there are things there in the Philippines that do not look good to us from the standpoint right now of democratic rights, but what is the alternative? It is a large communist movementreferring to active Communist guerrillas operating in the Philippines at the time. The U.S. also had significant strategic military interests in the Philippines, knowing that Marcos's government would not tamper with agreements to maintain U.S. naval bases in the country. Marcos was later ousted in 1986 by the mostly peaceful People Power Revolution, People Power movement, led by

Corazón Aquino

Maria Corazon "Cory" Sumulong Cojuangco-Aquino (; ; January 25, 1933 – August 1, 2009) was a Filipina politician who served as the 11th president of the Philippines from 1986 to 1992. She was the most prominent figure of the 1986 People ...

.

Reagan was sharply critical of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

, once the darling of liberals. He repudiated what he felt was its corruption, inefficiency and anti-Americanism. In 1985-1987 the U.S. withdrew from UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

, which had failed in its cultural missions, and began to deliberately withhold its UN dues. American policymakers considered this tactic an effective tool for asserting influence in the UN. When the UN and UNESCO mended their ways, the U.S. returned and paid its dues.

Last stage of the Cold War

The Reagan administration adopted a hard-line stance toward the USSR. Early in his first term, the president attacked the rival superpower as the " evil empire". While it was Jimmy Carter who had officially ended the policy of ''détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduce ...

'' following Soviet intervention in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, East-West tensions in the early 1980s reached levels not seen since the Cuban Missile Crisis. The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was born out of the worsening U.S.-Soviet relations of the Reagan Era. Popularly dubbed "Star Wars" at the time, SDI was a multibillion-dollar research project for a missile defense system that could shoot down incoming Soviet missiles and eliminate the need for mutually assured destruction.

While the Soviets had enjoyed great achievements on the international stage before Reagan entered office in 1981, such as the unification of their socialist ally, Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, in 1976, and a string of socialist revolutions in Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa, the country's strengthening ties with Third World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

nations in the 1960s and 1970s only masked its weakness. The Soviet economy suffered severe structural problems and started suffering from an increased stagnation in the 1970s. Documents being circulated in the Kremlin in 1980, when Carter was still president, expressed the bleak view that Moscow ultimately could not win the technological or ideological battle with the US.

East-West tensions eased rapidly after the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev. After the deaths of three elderly Soviet leaders in a row since 1982, the Politburo elected Gorbachev Soviet Communist Party chief in 1985, marking the rise of a new generation of leadership. Under Gorbachev, relatively young reform-oriented technocrats rapidly consolidated power, providing new momentum for political and economic liberalization, and the impetus for cultivating warmer relations and trade with the West.

Focused on '' perestroika'', Gorbachev struggled to boost production of consumer goods, which would be impossible given the twin burdens of the Cold War arms race on one hand, and the provision of large sums of foreign and military aid, which the socialist allies had grown to expect, on the other. Under Gorbachev, Soviet policymakers increasingly accepted Reagan administration warnings that the U.S. would make the arms race a huge burden for them. The Soviets were already spending massive amounts on defense, and developing a counterpart to SDI was far more than their economy could handle. The result in the Soviet Union was a dual approach of concessions to the United States and economic restructuring (''perestroika'') and democratization ('' glasnost'') domestically, which eventually made it impossible for Gorbachev to reassert central control. Reaganite hawks have since argued that pressures stemming from increased U.S. defense spending was an additional impetus for reform.

During the Cold War, the division of the world into two rival blocs had served to legitimize a broad and diffuse alliance not only with the Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

an nations of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

(NATO) but many countries in the developing world. Starting in the late 1980s, however, the regimes of the Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

an Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist repub ...

began to collapse in rapid succession. The "fall of the Berlin Wall" was seen as a symbol of the fall of the Eastern European Communist governments in 1989. U.S.-Soviet relations had greatly improved in the latter half of the decade, with the signing of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty

The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty, formally the Treaty Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Elimination of Their Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles; / ДРСМ� ...

(INF) in 1987 and the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan as well as Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

n forces from Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

. These developments undercut the rationale for providing support to such repressive governments as those in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

and South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its eas ...

, which underwent processes of democratization with U.S. support during the same period as those of Warsaw Pact nations.

George H. W. Bush administration

Reagan's vice-president George H. W. Bush easily won the 1988 Republican nomination and defeated Democratic Massachusetts governor

Reagan's vice-president George H. W. Bush easily won the 1988 Republican nomination and defeated Democratic Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis

Michael Stanley Dukakis (; born November 3, 1933) is an American retired lawyer and politician who served as governor of Massachusetts from 1975 to 1979 and again from 1983 to 1991. He is the longest-serving governor in Massachusetts history a ...

by an electoral landslide in the 1988 election. The campaign was marked by numerous blunders by Dukakis, including most famously a campaign ad featuring Dukakis in an M1 Abrams tank.

Foreign affairs

Unlike Reagan Bush downplayed vision and emphasized caution and careful management. His main foreign policy advisors were Secretaries of State James Baker andLawrence Eagleburger

Lawrence Sidney Eagleburger (August 1, 1930 – June 4, 2011) was an American statesman and career diplomat, who served briefly as the Secretary of State under President George H. W. Bush from December 1992 to January 1993, one of the shortest t ...

, and National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft. Bush entered the White House with a long and successful portfolio in foreign affairs including ambassadorial roles to China in the United Nations, director of the CIA, and official visits to 65 foreign countries as vice president.

Momentous geopolitical events that occurred during Bush's presidency include:

* The crushing in June 1989 of the Tiananmen Square protests in China, which was widely condemned in the United States and around the world.

* The United States invasion of Panama

The United States invasion of Panama, codenamed Operation Just Cause, lasted over a month between mid-December 1989 and late January 1990. It occurred during the administration of President George H. W. Bush and ten years after the Torrijos� ...

in December 1989 to overthrow a local dictator.

* The signing with the USSR of the START I and START II treaties for nuclear disarmament.

* The Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a Coalition of the Gulf War, 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Ba'athist Iraq, ...

in 1991, in which Bush led a large coalition that defeated Iraq when it invaded Kuwait.

* Victory in the Cold War over Soviet communism.

* Revolutions of 1989

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, was a revolutionary wave that resulted in the end of most communist states in the world. Sometimes this revolutionary wave is also called the Fall of Nations or the Autumn of Nat ...

and the collapse of Communism, especially in Eastern Europe

* German reunification in 1990, with the democratic West absorbing the ex-Communist East.

* The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, replaced by a friendly Russia and 14 other countries.

Except for Tiananmen Square in China, all the events strongly favored the United States. Bush took the initiative in the invasion of Panama and the START treaties. Otherwise, he was mostly a passive observer trying not to interfere or gloat about the events. Given the favorable outcomes, scholars generally give Bush high marks in foreign policy, except for his unwillingness to condemn the Tiananmen Square crackdown. He thought long-term favorable relations with China were too important to jeopardize. In terms of gaining public support, Bush never tried to mobilize much popular support for his foreign policy, and in domestic affairs his support was steadily slipping.

After the Cold War

Bush argued for the emergence of "a new world order... freer from the threat of terror, stronger in the pursuit of justice, and more secure in the quest for peace. An era in which the nations of the world, East and West, North and South, can prosper and live in harmony." Nationalist agitation in the Baltic States for independence led to first Lithuania and then the other two states,Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

and Latvia, declaring independence from the USSR . On December 26, 1991, the USSR was officially disbanded, breaking up into fifteen constituent parts. The Cold War was over, and the vacuum left by the collapse of governments such as in Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

and Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

revealed or reopened other animosities concealed by decades of authoritarian rule. While there was a certain reluctance among the U.S. public, and even within the government, to get involved in localized conflicts in which there was little or no direct U.S. interest at stake, these crises served as a basis for the renewal of Western alliances while communism was becoming less relevant. To this effect, President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

would declare in his inaugural address: "Today, as an old order passes, the new world is more free but less stable. Communism's collapse has called forth old animosities and new dangers. Clearly America must continue to lead the world we did so much to make."

Since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. has sought to revitalize Cold War institutional structures, especially NATO, as well as multilateral institutions such as the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster glo ...

and World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Inte ...

through which it promotes economic reforms around the globe. NATO was set to expand initially to Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic