History of slavery in Maryland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Slavery in Maryland lasted over 200 years, from its beginnings in 1642 when the first Africans were brought as slaves to

From the beginning, tobacco was the dominant cash crop in Maryland. Such was the importance of tobacco that, in the absence of sufficient silver coins, it served as the chief medium of exchange. John Ogilby wrote in his 1670 book ''America: Being an Accurate Description of the New World'': "The general way of traffick and commerce there is chiefly by Barter, or exchange of one commodity for another".

Since land was plentiful, and the demand for tobacco was growing, labor tended to be in short supply, especially at harvest time. The first

From the beginning, tobacco was the dominant cash crop in Maryland. Such was the importance of tobacco that, in the absence of sufficient silver coins, it served as the chief medium of exchange. John Ogilby wrote in his 1670 book ''America: Being an Accurate Description of the New World'': "The general way of traffick and commerce there is chiefly by Barter, or exchange of one commodity for another".

Since land was plentiful, and the demand for tobacco was growing, labor tended to be in short supply, especially at harvest time. The first

The first documented Africans were brought to Maryland in 1642, as 13 slaves at

The first documented Africans were brought to Maryland in 1642, as 13 slaves at

Retrieved August 10, 2010 Earlier, in 1638, the

During the eighteenth century the number of enslaved Africans imported into Maryland greatly increased, as the labor-intensive tobacco economy became dominant, and the colony developed into a slave society. In 1700 there were about 25,000 people in Maryland and by 1750 that had grown more than 5 times to 130,000. A great proportion of the population was enslaved. By 1755, about 40% of Maryland's population was black and these persons were overwhelmingly enslaved. The southern plantation counties had majority-slave populations by the end of the century.

In 1753 the Maryland assembly took further harsh steps to institutionalize slavery, passing a law that prohibited any slaveholder from independently manumitting his slaves. A slaveholder seeking manumission had to gain legislative approval for each act, meaning that few did so.

At this stage there were few voices of dissent among whites in Maryland. Although only the wealthy could afford slaves, poor whites who did not own slaves may have aspired to own them someday. The identity of many whites in Maryland, and the South in general, was tied up in the idea of

During the eighteenth century the number of enslaved Africans imported into Maryland greatly increased, as the labor-intensive tobacco economy became dominant, and the colony developed into a slave society. In 1700 there were about 25,000 people in Maryland and by 1750 that had grown more than 5 times to 130,000. A great proportion of the population was enslaved. By 1755, about 40% of Maryland's population was black and these persons were overwhelmingly enslaved. The southern plantation counties had majority-slave populations by the end of the century.

In 1753 the Maryland assembly took further harsh steps to institutionalize slavery, passing a law that prohibited any slaveholder from independently manumitting his slaves. A slaveholder seeking manumission had to gain legislative approval for each act, meaning that few did so.

At this stage there were few voices of dissent among whites in Maryland. Although only the wealthy could afford slaves, poor whites who did not own slaves may have aspired to own them someday. The identity of many whites in Maryland, and the South in general, was tied up in the idea of

The principal cause of the

The principal cause of the

The American Revolution had been fought for the cause of liberty of individual men, and many Marylanders who opposed slavery believed that Africans were equally men and should be free.

The American Revolution had been fought for the cause of liberty of individual men, and many Marylanders who opposed slavery believed that Africans were equally men and should be free.

Retrieved August 12, 2010 In 1780 the National Methodist Conference in

After his escape from slavery as a young man,

After his escape from slavery as a young man,

In 1822,

In 1822,

Concerned about the tensions of discrimination against free blacks (often

Concerned about the tensions of discrimination against free blacks (often  The society was founded in 1827, and its first president was the wealthy Maryland Catholic planter

The society was founded in 1827, and its first president was the wealthy Maryland Catholic planter

In December 1831, the Maryland state legislature appropriated $10,000 for twenty-six years to transport free blacks and formerly enslaved people from the United States to Africa. The act authorized appropriation of funds of up to $20,000 a year, up to a total of $200,000, in order to begin the process of African colonization.Freehling, William H., ''The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854'', p. 204

In December 1831, the Maryland state legislature appropriated $10,000 for twenty-six years to transport free blacks and formerly enslaved people from the United States to Africa. The act authorized appropriation of funds of up to $20,000 a year, up to a total of $200,000, in order to begin the process of African colonization.Freehling, William H., ''The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854'', p. 204

Retrieved March 12, 2010. Most of the money would be spent on the colony itself, to make it attractive to settlers. Free passage was offered, plus rent, of land to farm, and low-interest loans which would eventually be forgiven if the settlers chose to remain in the colony. The remainder was spent on agents paid to publicize the new colony.Freehling, William H., p. 206, ''The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854''

Retrieved March 12, 2010 Following Nat Turner's Slave Rebellion in 1831 in Virginia, Maryland and other states passed laws restricting the freedoms of Latrobe, John H. B., p. 125, ''Maryland in Liberia: a History of the Colony Planted By the Maryland State Colonization Society Under the Auspices of the State of Maryland, U. S. At Cape Palmas on the South-West Coast of Africa, 1833–1853'', published in 1885

Retrieved February 16, 2010.

In 1832 the legislature placed new restrictions on the liberty of free blacks, in order to encourage emigration. They were not permitted to vote, serve on juries, or hold public office. Unemployed adult free people of color without visible means of support could be re-enslaved at the discretion of local sheriffs. By this means the supporters of colonization hoped to encourage free blacks to leave the state.

John Latrobe, for two decades the president of the MSCS, and later president of the ACS, proclaimed that settlers would be motivated by the "desire to better one's condition", and that sooner or later "every free person of color" would be persuaded to leave Maryland.Freehling, William H., p. 207, ''The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854''

Retrieved March 12, 2010

For braver souls, impatient with efforts to abolish slavery within the law, there were always illegal methods. Slaves escaped independently; most often they were young males, as they could move more freely than women with children. Free blacks and white supporters of abolition of slavery gradually organized a number of safe places and guides, creating the

For braver souls, impatient with efforts to abolish slavery within the law, there were always illegal methods. Slaves escaped independently; most often they were young males, as they could move more freely than women with children. Free blacks and white supporters of abolition of slavery gradually organized a number of safe places and guides, creating the

Retrieved August 10, 2010 Although one in every six Maryland families still held slaves, most slaveholders held only a few per household. Support for the institution of slavery was localized, varying according to its importance to the local economy and it continued to be integral to Southern Maryland's plantations. By 1860 Maryland's free black population comprised 49.1% of the total number of African Americans in the state.Peter Kolchin, ''American Slavery: 1619–1877'', New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, pp. 81–82 The small state of Maryland was home to nearly 84,000 free blacks in 1860, by far the most of any state; the state had ranked as having the highest number of free blacks since 1810. In addition, by this time, the vast majority of blacks in

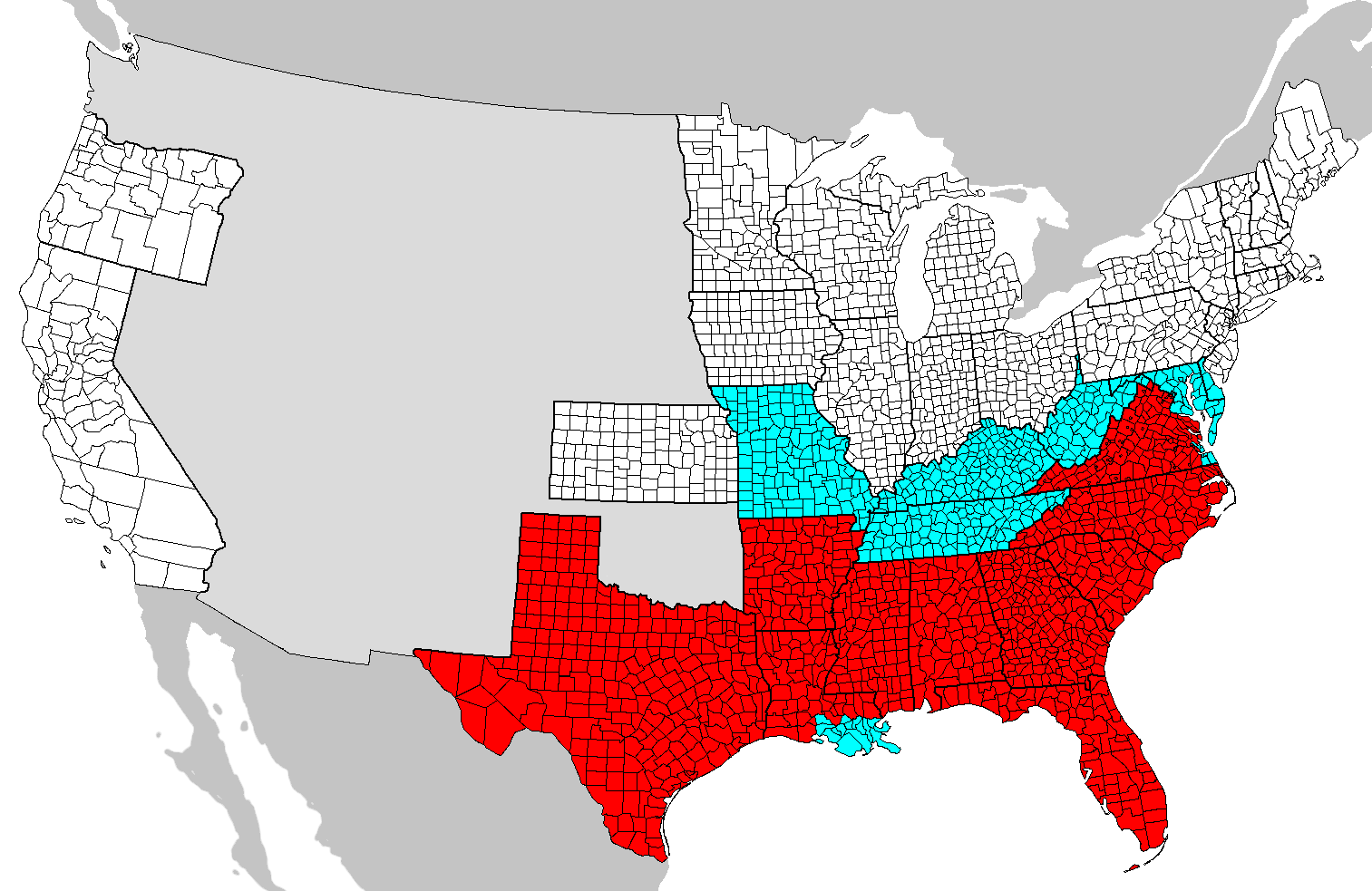

Like other border states such as

Like other border states such as

Osprey Publishing (2008), Retrieved March 4, 2010 After

Emancipation remained by no means a foregone conclusion at the start of the war, though events soon began to move against slaveholding interests in Maryland. On December 16, 1861 a bill was presented to Congress to emancipate enslaved people in

Emancipation remained by no means a foregone conclusion at the start of the war, though events soon began to move against slaveholding interests in Maryland. On December 16, 1861 a bill was presented to Congress to emancipate enslaved people in

Chapelle, Suzanne Ellery Greene, ''Maryland: A History of Its People''

Retrieved August 10, 2010

Ferguson, Niall, ''Civilization: The Six Killer Apps of Western Power''

Retrieved April 2013

Flint, John E., et al, ''The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1790 to c. 1870'' Cambridge University Press (1977)

Retrieved February 16, 2010.

Freehling, William H., ''The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854''

Retrieved March 12, 2010 * Hall, Richard, ''On Afric's Shore: A History of Maryland in Liberia, 1834–1857''

Latrobe, John H. B., p. 125, ''Maryland in Liberia: a History of the Colony Planted By the Maryland State Colonization Society Under the Auspices of the State of Maryland, U. S. At Cape Palmas on the South-West Coast of Africa, 1833–1853'' (1885).

Retrieved Feb 16 2010

Rhodes, Jason, ''Somerset County, Maryland: a Brief History''

Retrieved August 11, 2010

Stebbins, Giles B., ''Facts and Opinions Touching the Real Origin, Character, and Influence of the American Colonization Society: Views of Wilberforce, Clarkson, and Others'', published by Jewitt, Proctor, and Worthington (1853).

Retrieved February 16, 2010.

Switala, William J., ''Underground Railroad in Delaware, Maryland, and West Virginia''

Retrieved August 12, 2010

''Maryland Colonization Journal'' published by the Maryland State Colonization Society

Retrieved February 16, 2010.

''Discussion on American Slavery: Between George Thompson, Esq., Agent of the British and Foreign Society for the Abolition of Slavery Throughout the World, 17th of June, 1836''

Published by

Legacy of Slavery in Maryland – Maryland State Archives

Retrieved October 2014

University of Maryland Special Collections Guide on Slavery in MarylandGurley, Ralph Randolph, Ed., p. 251, ''The African Repository'', Volume 3

Retrieved February 15, 2010.

Proceedings of the Maryland Colonization Society at ''Niles' National Register, Volume 47''

Retrieved February 16, 2010.

Retrieved February 16, 2010.

Retrieved February 16, 2010. {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Slavery In Maryland African-American history of Maryland History of racism in Maryland Slavery in the British Empire St. Mary's County, Maryland MD

St. Mary's City

St. Mary's City (also known as Historic St. Mary's City) is a former colonial town that was Maryland's first European settlement and capital. It is now a large, state-run historic area, which includes a reconstruction of the original colonial se ...

, to its end after the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. While Maryland developed similarly to neighboring Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, slavery declined here as an institution earlier, and it had the largest free black population by 1860 of any state. The early settlements and population centers of the province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

. Maryland planters cultivated tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

as the chief commodity crop, as the market was strong in Europe. Tobacco was labor-intensive in both cultivation and processing, and planters struggled to manage workers as tobacco prices declined in the late 17th century, even as farms became larger and more efficient. At first, indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

from England supplied much of the necessary labor but, as their economy improved at home, fewer made passage to the colonies. Maryland colonists turned to importing indentured and enslaved Africans to satisfy the labor demand.

By the 18th century, Maryland had developed into a plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

colony and slave society, requiring extensive numbers of field hands for the labor-intensive commodity crop of tobacco. In 1700, the province had a population of about 25,000, and by 1750 that number had grown more than five times to 130,000. By 1755, about 40% of Maryland's population was black, with African Americans concentrated in the Tidewater counties where tobacco was grown.John Mack Faragher, ed., ''The Encyclopedia of Colonial and Revolutionary America'' (New York: Facts on File, 1990), p. 257 Planters relied on the extensive system of rivers to transport their produce from inland plantations to the Atlantic coast for export. Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

was the second-most important port in the eighteenth-century South, after Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

.

In the first two decades after the Revolutionary War, a number of slaveholders freed their slaves. In addition, numerous free families of color had started during the colonial era with mixed-race children born free as a result of unions between white women and African-descended men. Although the colonial and state legislatures passed restrictions against manumissions and free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

, by the time of the Civil War, slightly more than 49% of the black people (including people of color) in Maryland were free and the total of slaves had steadily declined since 1810.

During the American Civil War, fought over the issue of slavery, Maryland remained in the Union, though a minority of its citizens – and virtually all of its slaveholders – were sympathetic toward the rebel Confederate States

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

. As a Union border state, Maryland was not included in President Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

, which declared all slaves in Southern Confederate states to be free. The following year, Maryland held a constitutional convention. A new state constitution was passed on November 1, 1864, and Article 24 prohibited the practice of slavery. The right to vote was extended to non-white males in the Maryland Constitution of 1867

The current Constitution of the State of Maryland, which was ratified by the people of the state on September 18, 1867, forms the basic law for the U.S. state of Maryland. It replaced the short-lived Maryland Constitution of 1864 and is the fourt ...

, which remains in effect today. (The vote was extended to women of all races in 1920 by ratification of a national constitutional amendment.)

Beginnings

Tobacco

From the beginning, tobacco was the dominant cash crop in Maryland. Such was the importance of tobacco that, in the absence of sufficient silver coins, it served as the chief medium of exchange. John Ogilby wrote in his 1670 book ''America: Being an Accurate Description of the New World'': "The general way of traffick and commerce there is chiefly by Barter, or exchange of one commodity for another".

Since land was plentiful, and the demand for tobacco was growing, labor tended to be in short supply, especially at harvest time. The first

From the beginning, tobacco was the dominant cash crop in Maryland. Such was the importance of tobacco that, in the absence of sufficient silver coins, it served as the chief medium of exchange. John Ogilby wrote in his 1670 book ''America: Being an Accurate Description of the New World'': "The general way of traffick and commerce there is chiefly by Barter, or exchange of one commodity for another".

Since land was plentiful, and the demand for tobacco was growing, labor tended to be in short supply, especially at harvest time. The first Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

ns to be brought to English North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

landed in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

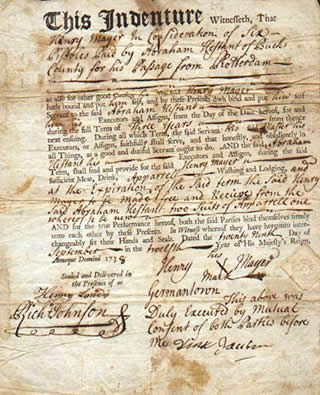

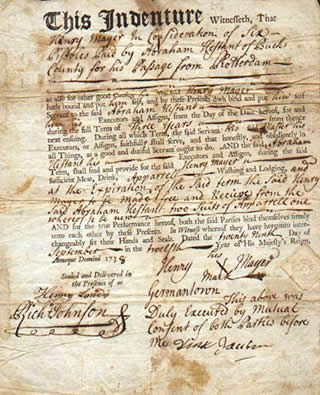

in 1619, rescued by the Dutch from a Portuguese slave ship. These individuals appear to have been treated as indentured servant

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an " indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment ...

s. A significant number of Africans after them also gained freedom through fulfilling a work contract or for converting to Christianity.

Some successful free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

, such as Anthony Johnson, prospered enough to acquire slaves or indentured servants. This evidence suggests that racial attitudes were much more flexible in the colonies in the 17th century than they later became, when slavery was hardened as a racial caste.

Import of enslaved Africans

The first documented Africans were brought to Maryland in 1642, as 13 slaves at

The first documented Africans were brought to Maryland in 1642, as 13 slaves at St. Mary's City

St. Mary's City (also known as Historic St. Mary's City) is a former colonial town that was Maryland's first European settlement and capital. It is now a large, state-run historic area, which includes a reconstruction of the original colonial se ...

, the first English settlement in the Province.Chapelle, Suzanne Ellery Greene, p. 24, ''Maryland: A History of Its People''Retrieved August 10, 2010 Earlier, in 1638, the

Maryland General Assembly

The Maryland General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland that convenes within the State House in Annapolis. It is a bicameral body: the upper chamber, the Maryland Senate, has 47 representatives and the lower chamb ...

had considered, but not enacted, two bills referring to slaves and proposing excepting them from rights shared by Christian freemen and indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

: An Act for the Liberties of the People and An Act Limiting the Times of Servants. The legal status of Africans initially remained undefined; since they were not English subjects, they were considered foreigners. Colonial courts tended to rule that any person who accepted Christian baptism should be freed. In order to protect the property rights of slaveholders, the colony passed laws to clarify the legal position.

In 1692 the Maryland Assembly passed a law explicitly forbidding "miscegenation"—marriage between different races. It never controlled the abuse by white men of enslaved African women.

State establishes perpetual slavery

In 1664, under the governorship ofCharles Calvert, 3rd Baron Baltimore

Charles Calvert, 3rd Baron Baltimore (August 27, 1637 – February 21, 1715), inherited the colony of Maryland in 1675 upon the death of his father, Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore, (1605–1675). He had been his father's Deputy Governor sin ...

, the Assembly ruled that all enslaved people should be held in slavery for life, and that children of enslaved mothers should also be held in slavery for life. The 1664 Act read as follows:

Be it enacted by the Right Honorable, the Lord Proprietary, by the advice and consent of the Upper and Lower House of this present General Assembly, that all negroes or other slaves already within the Province, and all negroes and other slaves to be hereafter imported into the Province shall serve ''durante vita''. And all children born of any negro or other slave shall be slaves as their fathers were for the term of their lives.In this way the institution of slavery in Maryland was made self-perpetuating, as the slaves had good enough health to reproduce. The numbers of slaves in Maryland was increased even more by continued imports up until 1808. By making slave status dependent on the mother, according to the principle of ''

partus sequitur ventrem

''Partus sequitur ventrem'' (L. "That which is born follows the womb"; also ''partus'') was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born th ...

,'' Maryland, like Virginia, abandoned the common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipresen ...

approach of England, in which the social status of children of English subjects depended on their father. In the colonies, children would take the status of their mothers and thus be born into slavery if their mothers were enslaved, regardless if their fathers were white, English and Christian, as many were.

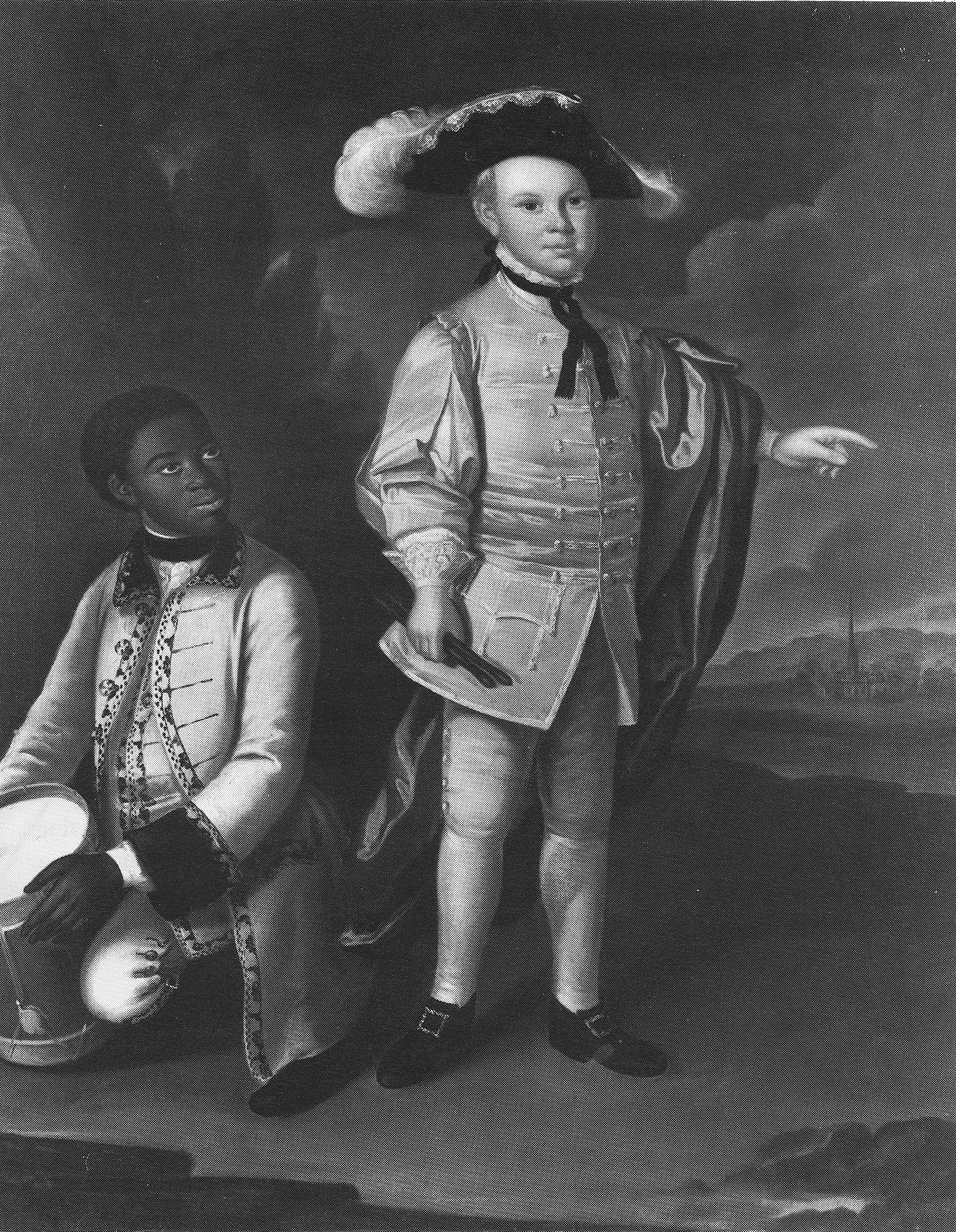

The wording of the 1664 Act suggests that Africans may not have been the only slaves in Maryland. Although there is no direct evidence of the enslavement of Native Americans, the reference to "negroes and other slaves" may imply that, as in Massachusetts, Virginia and the Carolinas, the colonists may have enslaved local Indians.Andrews, p. 191 Alternatively, the wording in the Act may have been intended to apply to slaves of African origin but of mixed-race ancestry. The early years included slaves who were African Creoles, descendants of African women and Portuguese men who worked at the slave ports. In addition, mixed-race children were born to slave women and white fathers. Numerous free families of color were formed during the colonial years by formal and informal unions between free white women and African-descended men, whether free, indentured or enslaved. Although born free to white women, the mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-ethn ...

children were considered illegitimate and were apprenticed for lengthy periods into adulthood.

In an unusual case, Nell Butler was an Irish-born indentured servant

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an " indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment ...

of Lord Calvert. After she married an enslaved African, her indenture was converted to slavery for life under the 1664 Act.

Further legislation would follow, entrenching and deepening the institution of slavery. Following the lead of Virginia, in 1671 the Assembly passed an Act stating expressly that baptism of a slave would not lead to freedom. Prior to this some slaves had sued for freedom based on having been baptized. The Act was apparently intended to save the souls of the enslaved; the legislature did not want to discourage slaveholders from baptizing his human property for fear of losing it. In practice, such laws permitted both Christianity and slavery to develop hand in hand.

At this early stage in Maryland history, slaves were not especially numerous in the Province, being greatly outnumbered by indentured servants from England. The full effect of such harsh slave laws did not become evident until after large-scale importation of Africans began in earnest in the 1690s. During the second half of the 17th century, the British economy gradually improved and the supply of British indentured servants declined, as poor Britons had better economic opportunities at home. At the same time, Bacon's Rebellion

Bacon's Rebellion was an armed rebellion held by Colony of Virginia, Virginia settlers that took place from 1676 to 1677. It was led by Nathaniel Bacon (Virginia colonist), Nathaniel Bacon against List of colonial governors of Virginia, Colon ...

of 1676 led planters to worry about the prospective dangers of creating a large class of restless, landless, and relatively poor white men (most of them former indentured servants). Wealthy Virginia and Maryland planters began to buy slaves in preference to indentured servants during the 1660s and 1670s, and poorer planters followed suit by c.1700. Enslaved Africans cost more than servants, so initially only the wealthy could invest in slavery. By the end of the seventeenth century, planters shifted away from indentured servants, and in favor of the importation and enslavement of African people.

Eighteenth century

During the eighteenth century the number of enslaved Africans imported into Maryland greatly increased, as the labor-intensive tobacco economy became dominant, and the colony developed into a slave society. In 1700 there were about 25,000 people in Maryland and by 1750 that had grown more than 5 times to 130,000. A great proportion of the population was enslaved. By 1755, about 40% of Maryland's population was black and these persons were overwhelmingly enslaved. The southern plantation counties had majority-slave populations by the end of the century.

In 1753 the Maryland assembly took further harsh steps to institutionalize slavery, passing a law that prohibited any slaveholder from independently manumitting his slaves. A slaveholder seeking manumission had to gain legislative approval for each act, meaning that few did so.

At this stage there were few voices of dissent among whites in Maryland. Although only the wealthy could afford slaves, poor whites who did not own slaves may have aspired to own them someday. The identity of many whites in Maryland, and the South in general, was tied up in the idea of

During the eighteenth century the number of enslaved Africans imported into Maryland greatly increased, as the labor-intensive tobacco economy became dominant, and the colony developed into a slave society. In 1700 there were about 25,000 people in Maryland and by 1750 that had grown more than 5 times to 130,000. A great proportion of the population was enslaved. By 1755, about 40% of Maryland's population was black and these persons were overwhelmingly enslaved. The southern plantation counties had majority-slave populations by the end of the century.

In 1753 the Maryland assembly took further harsh steps to institutionalize slavery, passing a law that prohibited any slaveholder from independently manumitting his slaves. A slaveholder seeking manumission had to gain legislative approval for each act, meaning that few did so.

At this stage there were few voices of dissent among whites in Maryland. Although only the wealthy could afford slaves, poor whites who did not own slaves may have aspired to own them someday. The identity of many whites in Maryland, and the South in general, was tied up in the idea of white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

. As the French political philosopher Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principa ...

noted in 1748: "It is impossible for us to suppose these creatures nslaved Africansto be men; because allowing them to be men, a suspicion would follow that we ourselves are not Christians."

Revolutionary War

The principal cause of the

The principal cause of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

was liberty, but only on behalf of white men, and certainly not slaves, Indians or women

A woman is an adult female human. Prior to adulthood, a female human is referred to as a girl (a female child or Adolescence, adolescent). The plural ''women'' is sometimes used in certain phrases such as "women's rights" to denote female hum ...

. The British, desperately short of manpower, sought to enlist African Americans as soldiers to fight on behalf of the Crown, promising them liberty in exchange. As a result of the looming crisis in 1775 the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore

Earl of Dunmore is a title in the Peerage of Scotland.

History

The title was created in 1686 for Lord Charles Murray, second son of John Murray, 1st Marquess of Atholl. He was made Lord Murray of Blair, Moulin and Tillimet (or Tullimet) and V ...

, issued a proclamation that promised freedom to servants and slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

s who were able to bear arms and join his Loyalist Ethiopian Regiment

The Ethiopian Regiment, better known as Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment, was a British colonial military unit organized during the American Revolution by the Earl of Dunmore, last Royal Governor of Virginia. Composed of formerly enslaved peopl ...

:

About 800 men joined up; some helped rout the Virginia militia at the Battle of Kemp's Landing

The Battle of Kemp's Landing, also known as the Skirmish of Kempsville, was a skirmish in the American Revolutionary War that occurred on November 15, 1775. Militia companies from Princess Anne County in the Province of Virginia assembled at Ke ...

and fought in the Battle of Great Bridge

The Battle of Great Bridge was fought December 9, 1775, in the area of Great Bridge, Virginia, early in the American Revolutionary War. The victory by colonial Virginia militia forces led to the departure of Royal Governor Lord Dunmore and any r ...

on the Elizabeth River, wearing the motto "Liberty to Slaves", but this time they were defeated. The remains of their regiment were involved in the evacuation of Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

, after which they served in the Chesapeake Chesapeake often refers to:

*Chesapeake people, a Native American tribe also known as the Chesepian

* The Chesapeake, a.k.a. Chesapeake Bay

*Delmarva Peninsula, also known as the Chesapeake Peninsula

Chesapeake may also refer to:

Populated plac ...

area. Their camp suffered an outbreak of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and other infectious diseases. This took a heavy toll, putting many of them out of action for some time. The survivors joined other British units and continued to serve throughout the war. Blacks were often the first to come forward to volunteer, and a total of 12,000 blacks served with the British from 1775 to 1783. This factor had the effect of forcing the rebels to also offer freedom to those who would serve in the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

; ultimately, more than 5,000 African Americans (many of them enslaved) served in Patriot military units during the war. Thousands of slaves in the South left their plantations to join the British. Keeping their promise, the British transported about 3,000 freed slaves to Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, where they granted them land. Others were taken to the Caribbean colonies, or to London.

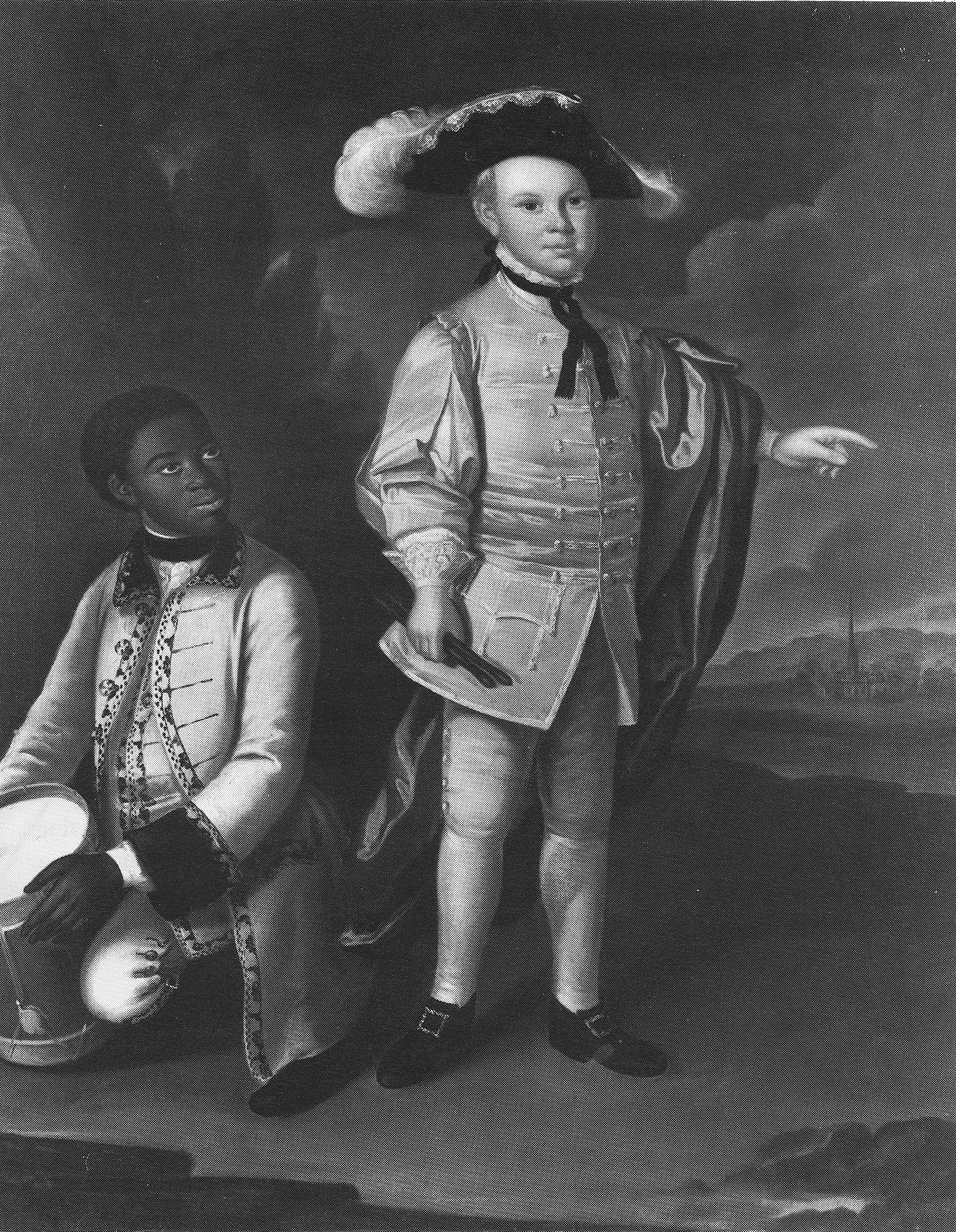

In general, the war left the institution of slavery largely unaffected, and the prosperous life of successful Maryland planters was revived. The writer Abbe Robin, who travelled through Maryland during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, described the lifestyle enjoyed by families of wealth and status in the Province:

aryland housesare large and spacious habitations, widely separated, composed of a number of buildings and surrounded by plantations extending farther than the eye can reach, cultivated ... by unhappy black men whom European avarice brings hither ... Their furniture is of the most costly wood, and rarest marbles, enriched by skilful and artistic work. Their elegant and light carriages are drawn by finely bred horses, and driven by richly apparelled slaves.Yentsch, Anne E, p. 265, ''A Chesapeake Family and their Slaves: a Study in Historical Archaeology'', Cambridge University Press (1994)Slave labor made possible the export-driven plantation economy. The English observer William Strickland wrote of agriculture in Virginia and Maryland in the 1790s:

Retrieved Jan 2010

Nothing can be conceived more inert than a slave; his unwilling labour is discovered in every step he takes; he moves not if he can avoid it; if the eyes of the overseer be off him, he sleeps. The ox and horse, driven by the slave, appear to sleep also; all is listless inactivity; all motion is evidently compulsory.

Voices for abolition

Methodists and Quakers

The American Revolution had been fought for the cause of liberty of individual men, and many Marylanders who opposed slavery believed that Africans were equally men and should be free.

The American Revolution had been fought for the cause of liberty of individual men, and many Marylanders who opposed slavery believed that Africans were equally men and should be free. Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

s in particular, of whom Maryland had more than any other state in the Union, were opposed to slavery on Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

grounds.Switala, William J., p. 70, ''Underground Railroad in Delaware, Maryland, and West Virginia''Retrieved August 12, 2010 In 1780 the National Methodist Conference in

Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

officially condemned slavery. In 1784 the church threatened Methodist preachers with suspension if they held people in slavery. This was a period of the Great Awakening

Great Awakening refers to a number of periods of religious revival in American Christian history. Historians and theologians identify three, or sometimes four, waves of increased religious enthusiasm between the early 18th century and the late ...

, and Methodists preached the spiritual equality of men, as well as licensing slaves and free blacks as preachers and deacons.

The Methodist movement in the United States as a whole was not of one voice on the subject of slavery. By the antebellum years in the South, most Methodist congregations supported the institution and preachers had made their peace with it, working to improve conditions of the institution. Ministers (and their congregants) often cited Old Testament scriptures as justification, which they interpreted as representing slavery as a part of the natural order of things.Camerona, Richard M., ''Methodism and Society''. Vol. 1–3. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press (1961). Eventually the Methodist Church split into two regional associations over the issue of slavery before the Civil War.

Those looking for Biblical support cited Leviticus Chapter 25, verses 44–46, which state as follows:

New Testament writings were sometimes used to support the case for slavery as well. Some of the writings of Paul, especially in Ephesians, instruct slaves to remain obedient to their masters. Southern ideology after the Revolution developed to argue a paternalistic point of view, that slavery was beneficial for enslaved people as well as the people who held them in slavery. They said that Christian planters could concentrate on improving treatment of slaves and that the people in bondage were offered protections from many ills, and treated better than industrial workers in the North.

In the mid-1790s the Methodists and the Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

drew together to form the Maryland Society of the Abolition of Slavery. Together they lobbied the legislature. In 1796 they gained repeal of the 1753 law that had prohibited individual manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

s by a slaveholder. Responding to Methodist and Quaker persuasion, as well as revolutionary ideals and lower labor needs, in the first two decades after the war, a number of slaveholders freed their slaves. In 1815 the Methodists and Quakers formed the Protection Society of Maryland, a group which sought protection for the increasing number of free blacks living in the state. By the time of the Civil War, 49.1% of Maryland blacks were free, including most of the large black population of Baltimore.

Roman Catholic Church

Other churches in Maryland were more equivocal. TheRoman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in Maryland and its members had long tolerated slavery. Despite a firm stand for the spiritual equality of black people, Jesuit missioners also continued to own slaves on their plantations. The Catholic Church in Maryland had supported slaveholding interests. The Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

controlled six plantations totaling nearly 12,000 acres, some of which had been donated to the church. In 1838 they ended slaveholding with a mass sale of their 272 slaves to sugar cane plantations in Louisiana in the Deep South. This was historically one of the largest single slave sales in colonial Maryland. The Jesuits' plantations had not been managed profitably, and they wanted to devote their funds to urban areas, including their schools, such as Georgetown College

Georgetown College is a private Christian college in Georgetown, Kentucky. Chartered in 1829, Georgetown was the first Baptist college west of the Appalachian Mountains.

The college offers 38 undergraduate degrees and a Master of Arts in educat ...

, located near the busy port on the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

adjacent to Washington, DC, and two new Catholic high schools in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. The Jesuits believed that their mission had to be redirected to urban areas, where the number of Catholic European immigrants were increasing. Pope Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI ( la, Gregorius XVI; it, Gregorio XVI; born Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari; 18 September 1765 – 1 June 1846) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1831 to his death in 1 June 1846. He h ...

issued a resounding condemnation of slavery in his 1839 bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e., cows), bulls have long been an important symbol in many religions,

includin ...

''In supremo apostolatus

''In supremo apostolatus'' is a papal bull issued by Pope Gregory XVI regarding the institution of slavery. Issued on December 3, 1839, as a result of a broad consultation among the College of Cardinals, the bull resoundingly denounces both the s ...

.''

Notable Maryland Enslaved African-Americans

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

remained in the North, where he became an influential national voice in favor of abolition and lectured widely about the abuses of slavery. Douglass was born a slave in Talbot County, Maryland

Talbot County is located in the heart of the Eastern Shore of Maryland in the U.S. state of Maryland. As of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 37,526. Its county seat is Easton, Maryland, Easton. The county was named ...

, between Hillsboro and Cordova, probably in his grandmother's shack east of Tappers Corner () and west of Tuckahoe Creek

Tuckahoe Creek is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 tributary of the Choptank River on Maryland's Eastern Shore. It is sometimes (erroneously) referred to as ...

.

The exact date of his birth is unknown, though it seems likely he was born in 1818. Douglass wrote of his childhood:

Douglass wrote several autobiographies, eloquently describing his experiences in slavery in his 1845 autobiography, ''Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave

''Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass'' is an 1845 memoir and treatise on abolition written by famous orator and former slave Frederick Douglass during his time in Lynn, Massachusetts. It is generally held to be the most famous of a number ...

.'' It became influential in its support for abolition, and Douglass spoke widely on the Northern abolition lecture circuit.

Harriet Tubman

In 1822,

In 1822, Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Ross, March 10, 1913) was an American abolitionist and social activist. Born into slavery, Tubman escaped and subsequently made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 slaves, including family and friends, us ...

was born into slavery in Dorchester County, Maryland

Dorchester County is a county located in the U.S. state of Maryland. At the 2020 census, the population was 32,531. Its county seat is Cambridge. The county was formed in 1669 and named for the Earl of Dorset, a family friend of the Calverts (t ...

. After escaping in 1849, she returned secretly to the state several times, helping a total of 70 slaves (including relatives) make their way to freedom. She used the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

to make thirteen missions. While later working in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

, Tubman helped more than 700 slaves escape during the Raid at Combahee Ferry

The Raid on Combahee Ferry ( , also known as the Combahee River Raid) was a military operation during the American Civil War conducted on June 1 and June 2, 1863, by elements of the Union Army along the Combahee River in Beaufort and Colleton c ...

.

Maryland State Colonization Society

Concerned about the tensions of discrimination against free blacks (often

Concerned about the tensions of discrimination against free blacks (often free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

with mixed ancestry) and the threat they posed to slave societies, planters and others organized the Maryland State Colonization Society

The Maryland State Colonization Society was the Maryland branch of the American Colonization Society, an organization founded in 1816 with the purpose of returning free African Americans to what many Southerners considered greater freedom in Af ...

in 1817 as an auxiliary branch of the American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America until 1837, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the migration of freebor ...

, founded in Washington D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, Na ...

in 1816. The MSCS had strong Christian support and was the primary organization proposing "return" of all free African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

to a colony to be established in Africa. But, by this time, most slaves and free blacks had been born in the United States, and wanted to gain their rights in the country they felt was theirs.

The ACS founded the colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the ''metropole, metropolit ...

of Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

in 1821–22, as a place in West Africa for freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

. Wanting to control its own territory and solve its perceived problems, the Maryland State Colonization Society founded the Republic of Maryland

The Republic of Maryland (also known variously as the Independent State of Maryland, Maryland-in-Africa, and Maryland in Liberia) was a country in West Africa that existed from 1834 to 1857, when it was merged into what is now Liberia. The area ...

in West Africa, a short-lived independent state. In 1857 it was annexed by Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

.

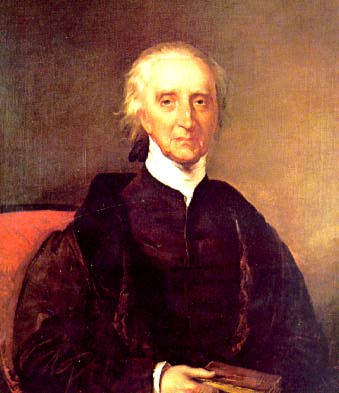

The society was founded in 1827, and its first president was the wealthy Maryland Catholic planter

The society was founded in 1827, and its first president was the wealthy Maryland Catholic planter Charles Carroll of Carrollton

Charles Carroll (September 19, 1737 – November 14, 1832), known as Charles Carroll of Carrollton or Charles Carroll III, was an Irish-American politician, planter, and signatory of the Declaration of Independence. He was the only Catholic sign ...

, who was a substantial slaveholder. Although Carroll supported the gradual abolition of slavery, he did not free his own slaves, perhaps fearing that they might be rendered destitute by the difficulties of earning a living in the discriminatory society. Carroll introduced a bill for the gradual abolition of slavery in the Maryland senate but it did not pass.

Many wealthy Maryland planters were members of the MSCS. Among these were the Steuart family

The Steuart family of Maryland was a prominent political family in the early History of Maryland. Of Scottish descent, the Steuarts have their origins in Perthshire, Scotland. The family grew wealthy in the early 18th century under the patronage o ...

, who owned considerable estates in the Chesapeake Bay, including Major General George H. Steuart

George Hume Steuart (1790–1867) was a United States general who fought during the War of 1812, and later joined the Confederate States of America during the Civil War. His military career began in 1814 when, as a captain, he raised a company of ...

, who was on the board of Managers; his father James Steuart, who was vice-president; and his brother, the physician Richard Sprigg Steuart

Richard Sprigg Steuart (1797–1876) was a Maryland physician and an early pioneer of the treatment of mental illness. In 1838 he inherited four contiguous farms, totalling approximately 1900 acres as well as 150 slaves.MSA C153-10, Liber TTS #1, ...

, also on the board of Managers.

In an open letter to John Carey in 1845, published in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

by the printer John Murphy, Richard Sprigg Steuart set out his views on the subject of relocating freed slaves to Africa. Such opinions were likely widespread among Maryland slaveholders:

The colored manThe society proposed from the outset "to be a remedy for slavery", and declared in 1833:ust UST or Ust may refer to: Organizations * UST (company), American digital technology company * Equatorial Guinea Workers' Union * Union of Trade Unions of Chad (Union des Syndicats du Tchad) * United States Television Manufacturing Corp. * UST Gr ...look to Africa, as his only hope of preservation and of happiness ... it can not be denied that the question is fraught with great difficulties and perplexities, but ... it will be found that this course of procedure ... will ... at no very distant period, secure the removal of the great body of the African people from our State. The President of the Maryland Colonization Society points to this in his address, where he says "the object of Colonization is to prepare a home in Africa for the free colored people of the State, to which they may remove when the advantages which it offers, and above all the pressure of irresistible circumstances in this country, shall excite them to emigrate.

''Resolved'', That this society believe, and act upon the belief, that colonization tends to promote emancipation, by affording the emancipated slave a home where he can be happier than in this country, and so inducing masters to manumit who would not do so unconditionally ...o that O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), plu ...at a time not remote, slavery would cease in the state by the full consent of those interested.

Republic of Maryland founded in Africa

In December 1831, the Maryland state legislature appropriated $10,000 for twenty-six years to transport free blacks and formerly enslaved people from the United States to Africa. The act authorized appropriation of funds of up to $20,000 a year, up to a total of $200,000, in order to begin the process of African colonization.Freehling, William H., ''The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854'', p. 204

In December 1831, the Maryland state legislature appropriated $10,000 for twenty-six years to transport free blacks and formerly enslaved people from the United States to Africa. The act authorized appropriation of funds of up to $20,000 a year, up to a total of $200,000, in order to begin the process of African colonization.Freehling, William H., ''The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854'', p. 204Retrieved March 12, 2010. Most of the money would be spent on the colony itself, to make it attractive to settlers. Free passage was offered, plus rent, of land to farm, and low-interest loans which would eventually be forgiven if the settlers chose to remain in the colony. The remainder was spent on agents paid to publicize the new colony.Freehling, William H., p. 206, ''The Road to Disunion: Volume I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854''

Retrieved March 12, 2010 Following Nat Turner's Slave Rebellion in 1831 in Virginia, Maryland and other states passed laws restricting the freedoms of

free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

, as slaveholders feared their effect on slave societies. Persons who were manumitted

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that ...

were given a deadline to leave the state after gaining freedom, unless a court of law found them to be of such "extraordinary good conduct and character" that they might be permitted to remain. A slaveholder who manumitted a slave was required to report that action and person to the authorities, and county clerks who did not do so could be fined. To carry out the removal of free blacks from the state, the Maryland State Colonization Society was established. It was similar to the national American Colonization Society.Retrieved February 16, 2010.

Retrieved March 12, 2010

Underground Railroad

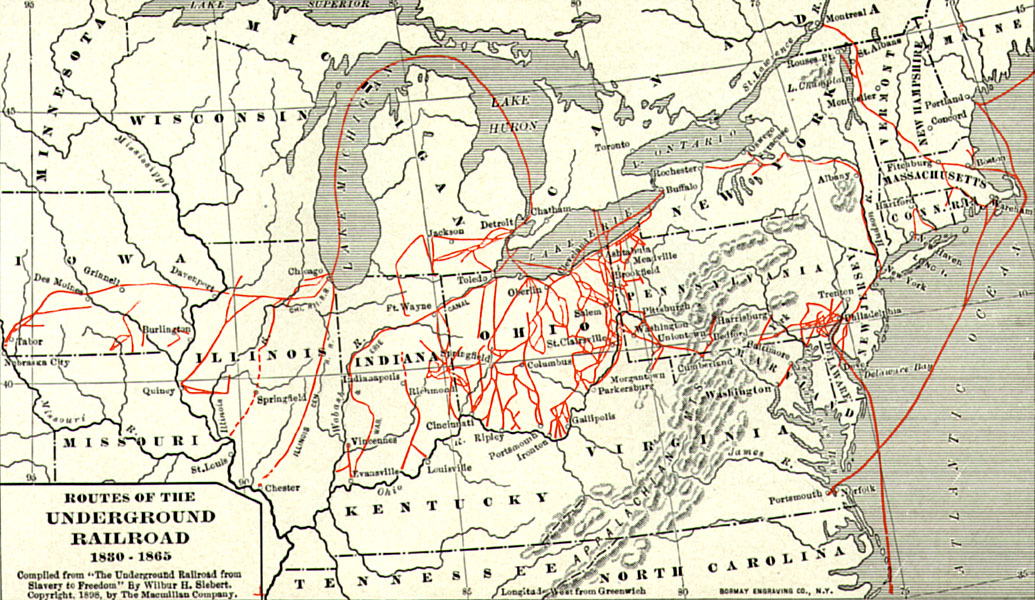

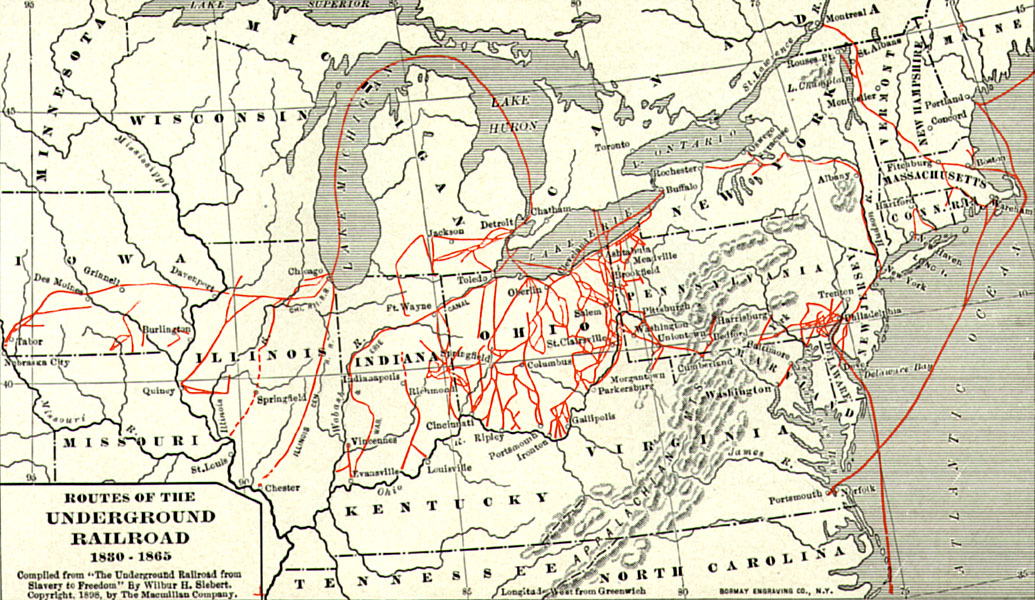

For braver souls, impatient with efforts to abolish slavery within the law, there were always illegal methods. Slaves escaped independently; most often they were young males, as they could move more freely than women with children. Free blacks and white supporters of abolition of slavery gradually organized a number of safe places and guides, creating the

For braver souls, impatient with efforts to abolish slavery within the law, there were always illegal methods. Slaves escaped independently; most often they were young males, as they could move more freely than women with children. Free blacks and white supporters of abolition of slavery gradually organized a number of safe places and guides, creating the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

to help slaves gain safety in Northern states. The many Indian trails and waterways of Maryland, and in particular the countless inlets of the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

, afforded numerous ways to escape north by boat or land, with many people going to Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

as the nearest free state. Supporters would shelter refugees, and sometimes give them food and clothing.

As the numbers of slaves seeking freedom in the North grew, so did the reward for their capture. In 1806, the reward offered for the recaptured slaves was $6, but by 1833 it had risen to $30. In 1844, recaptured freedom seekers

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freed ...

fetched $15 if recaptured within of the owner and $50 if captured more than away.

Status of slavery in 1860

By the 1850s few Marylanders still believed that colonization was the solution to the perceived problems of slavery and free blacks in society.Chapelle, Suzanne Ellery Greene, p. 148, ''Maryland: A History of Its People''Retrieved August 10, 2010 Although one in every six Maryland families still held slaves, most slaveholders held only a few per household. Support for the institution of slavery was localized, varying according to its importance to the local economy and it continued to be integral to Southern Maryland's plantations. By 1860 Maryland's free black population comprised 49.1% of the total number of African Americans in the state.Peter Kolchin, ''American Slavery: 1619–1877'', New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, pp. 81–82 The small state of Maryland was home to nearly 84,000 free blacks in 1860, by far the most of any state; the state had ranked as having the highest number of free blacks since 1810. In addition, by this time, the vast majority of blacks in

Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

were free, and this free black population was more than in any other US city. Many planters in Maryland had freed their slaves in the years following the Revolutionary War. In addition, families of free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

had been formed during colonial times from unions between free white women and men of African descent and various social classes, and their descendants were among the free. As children took their status from their mothers, these mixed-race children were born free.Paul Heinegg, ''Free African Americans in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware'', 1995–2005

Marylanders might agree in principle that slavery could and should be abolished, but they were slow to achieve it statewide. Although the need for slaves had declined with the shift away from tobacco culture, and slaves were being sold to the Deep South, slavery was still too deeply embedded into Maryland society for the wealthiest whites to give it up voluntarily on a wide scale. Wealthy planters exercised considerable economic and political power in the state. Slavery did not end until after the Civil War.

Civil War

Approach of war

Like other border states such as

Like other border states such as Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

and Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, Maryland had a population divided over politics as war approached, with supporters of both North and South. The western and northern parts of the state, especially those Marylanders of German origin, held fewer slaves and tended to favor remaining in the Union, while the Tidewater Chesapeake Bay area – the three counties referred to as Southern Maryland which lay south of Washington D.C.: Calvert, Charles and St. Mary's – with its slave economy, tended to support the Confederacy if not outright secession.Field, Ron, et al., p. 33, ''The Confederate Army 1861–65: Missouri, Kentucky & Maryland''Osprey Publishing (2008), Retrieved March 4, 2010 After

John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

's raid on Harper's Ferry, Virginia (now in West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

), some citizens in slaveholding areas began forming local militias. Of the 1860 population of 687,000, about 60,000 men joined the Union and about 25,000 fought for the Confederacy. The political sentiments of each group generally reflected their economic interests.

The first bloodshed of the Civil War occurred on April 19, 1861 in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

involving Massachusetts troops who were fired on by civilians while marching between railroad stations. After that, Baltimore Mayor George William Brown

George William Brown (October 13, 1812 – September 8, 1890) was an American politician, judge and academic. He was mayor of Baltimore from 1860 to 1861, professor in University of Maryland School of Law, and 2nd Chief Judge and Supreme Bench of ...

, Marshal George P. Kane, and former Governor Enoch Louis Lowe

Enoch Louis Lowe (August 10, 1820August 23, 1892) was the 29th Governor of Maryland in the United States from 1851 to 1854.

Early life

He was the only child of Bradley Samuel Adams Lowe and Adelaide Bellumeau de la Vincendiere. He was born on A ...

requested that Maryland Governor Thomas H. Hicks, a slaveholder from the Eastern Shore, burn the railroad bridges and cut the telegraph lines leading to Baltimore to prevent further troops from entering the state. Hicks reportedly approved this proposal. These actions were addressed in the famous federal court case of ''Ex parte Merryman

''Ex parte Merryman'', 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861) (No. 9487), is a well-known and controversial U.S. federal court case that arose out of the American Civil War. It was a test of the authority of the President to suspend "t ...

''.

Maryland remained part of the Union during the United States Civil War, thanks to President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

's swift action to suppress dissent in the state. The belated assistance of Governor Hicks also played an important role; although initially indecisive, he co-operated with federal officials to stop further violence and prevent a move to secession.

Maryland left out of Emancipation Proclamation

Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, and in March 1862 Lincoln held talks with Marylanders on the subject of emancipation. Some Marylanders, such as Representative John W. Crisfield, resisted the President, arguing that freedom would be worse for the slaves than slavery. Such arguments became increasingly ineffective as the war progressed.

On April 10, 1862, Congress declared that the Federal government would compensate slaveholders who freed their slaves. Slaves in the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

were freed on April 16, 1862 and slaveholders were duly compensated. In July 1862 Congress took a major step towards emancipation by passing the Second Confiscation Act, which permitted the Union army to enlist African-American soldiers, and barred the army from recapturing runaway slaves. In the same month Lincoln offered to buy out Maryland slaveholders, offering $300 for each emancipated slave, but Crisfield (unwisely as it turned out) rejected this offer.

On September 17, 1862 General Robert E. Lee's invasion of Maryland was turned back by the Union army at the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

, which was tactically inconclusive but strategically important. It took place near Sharpsburg, Maryland

Sharpsburg is a town in Washington County, Maryland. The town is approximately south of Hagerstown. Its population was 705 at the 2010 census.

During the American Civil War, the Battle of Antietam, sometimes referred to as the Battle of Sharpsb ...

. Five days later, on September 22, encouraged by relative success at Antietam, President Lincoln issued an executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of th ...

known as the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

, which declared all enslaved people in Southern states to be free. The order went into effect in January 1863, but Maryland, like other border states, was exempted since it had remained loyal to the Union at the outbreak of war.

Maryland remained a slave state, but the tide was turning. In 1863 and 1864 growing numbers of Maryland slaves simply left their plantations to join the Union Army, accepting the promise of military service in return for freedom. One effect of this was to bring slave auctions to an end, as any slave could avoid sale, and win freedom, by simply offering to join the army. In 1863 Crisfield was defeated in local elections by the abolitionist candidate John Creswell

John Andrew Jackson Creswell (November 18, 1828December 23, 1891) was an American politician and abolitionist from Maryland, who served as United States Representative, United States Senator, and as Postmaster General of the United States app ...

, amid allegations of vote-rigging by the Union army. In Somerset County, Maryland

Somerset County is the southernmost county in the U.S. state of Maryland. As of the 2020 census, the population was 24,620, making it the second-least populous county in Maryland. The county seat is Princess Anne.

The county was named for Mary, ...

, Creswell outpolled Crisfield by a margin of 6,742 votes to 5,482, with Union soldiers effectively deciding the vote in favor of Creswell. The Civil War was not yet over, but slavery in Maryland had at last run its course. The abolitionists had almost won.

The ending of slavery in Maryland

The issue of slavery was finally confronted by the newMaryland Constitution of 1864

The Maryland Constitution of 1864 was the third of the four constitutions which have governed the U.S. state of Maryland. A controversial product of the Civil War and in effect only until 1867, when the state's present constitution was adopted, ...

which the state adopted late in that year. The document, which replaced the Maryland Constitution of 1851

The Maryland Constitution of 1851 was the second constitution of the U.S. state of Maryland following the revolution, replacing the Constitution of 1776. The primary reason for the new constitution was a need to re-apportion Maryland's legislature ...

, was pressed by Unionists who had secured control of the state, and was framed by a Convention which met at Annapolis in April 1864.Andrews, p. 553 Article 24 of the constitution at last outlawed the practice of slavery.

Special motion launches campaign to end slavery in the state

On December 16, 1863, a special meeting of the Central Committee of the Union Party of Maryland was called on the issue of slavery in the state"Immediate emancipation in Maryland. Proceedings of the Union State Central Committee, at a meeting held in Temperance Temple, Baltimore, Wednesday, December 16, 1863", 24 pages, Publisher: Cornell University Library (January 1, 1863), , (the Union Party was the most powerful legalized political party in the state at the time). At the meeting,Thomas Swann

Thomas Swann (February 3, 1809 – July 24, 1883) was an American lawyer and Politics of the United States, politician who also was President of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as it completed track to Wheeling, West Virginia, Wheeling and gaine ...

, a state politician, put forward a motion calling for the party to work for "Immediate emancipation (of all slaves) in Maryland". John Pendleton Kennedy

John Pendleton Kennedy (October 25, 1795 – August 18, 1870) was an American novelist, lawyer and Whig politician who served as United States Secretary of the Navy from July 26, 1852, to March 4, 1853, during the administration of President Mi ...

seconded the motion. Since Kennedy was the former speaker of the Maryland General Assembly, as well as being a respected Maryland author, his support carried enormous weight in the party. A vote was taken and the motion passed. However, the people of Maryland as a whole were by then divided on the issue, and so twelve months of campaigning and lobbying on the issue followed throughout the state. During this effort, Kennedy signed his name to a party pamphlet, calling for "immediate emancipation" of all slaves that was widely circulated.

On November 1, 1864, after a year-long debate, a state referendum was put forth on the slavery question: although tied to the larger referendum on changes to the state constitution, the slavery component was extremely well known and hotly debated. Barbara Jeanne Fields, "Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland During the Nineteenth Century (Yale Historical Publications Series)", Publisher: Univ Tennessee Press; (July 30, 2012), , Miranda S. Spivack, September 13, 2013, "The not-quite-Free State: Maryland dragged its feet on emancipation during Civil War: Special Report, Civil War 150", CHAPTER 7, The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/md-politics/the-not-quite-free-state-maryland-dragged-its-feet-on-emancipation-during-civil-war/2013/09/13/a34d35de-fec7-11e2-bd97-676ec24f1f3f_story.html The citizens of Maryland voted to abolish slavery, but only by a 1,000 vote margin, as the southern part of the state was heavily dependent on the slave economy.

Details of final vote

The constitution was submitted forratification

Ratification is a principal's approval of an act of its agent that lacked the authority to bind the principal legally. Ratification defines the international act in which a state indicates its consent to be bound to a treaty if the parties inten ...

on October 13, 1864 and was narrowly approved by a vote of 30,174 to 29,799 (50.3% to 49.7%) in a referendum