History of slavery in Florida on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Slavery in Florida is more central to Florida's history than it is to almost any other state. Florida's purchase by the United States from Spain in 1819 (effective 1821) was primarily a measure to strengthen the system of slavery on Southern plantations, by denying potential runaways the formerly safe haven of Florida.

Few enslaved Africans were imported into Florida from Cuba in the period of Spanish colonial rule, as there was little for them to do—no mines, no plantations. Starting in 1687, slaves escaping from English colonies to the north were freed when they reached Florida and accepted Catholic baptism. Black slavery in the region was widely established after Florida came under

Slavery in Florida is more central to Florida's history than it is to almost any other state. Florida's purchase by the United States from Spain in 1819 (effective 1821) was primarily a measure to strengthen the system of slavery on Southern plantations, by denying potential runaways the formerly safe haven of Florida.

Few enslaved Africans were imported into Florida from Cuba in the period of Spanish colonial rule, as there was little for them to do—no mines, no plantations. Starting in 1687, slaves escaping from English colonies to the north were freed when they reached Florida and accepted Catholic baptism. Black slavery in the region was widely established after Florida came under

The first enslaved African in Florida,

The first enslaved African in Florida,  Since 1688,

Since 1688,

American settlers began to establish

American settlers began to establish

In January 1861, nearly all delegates in the Florida Legislature approved an ordinance of secession, declaring Florida to be "a sovereign and independent nation"—an apparent reassertion to the preamble in Florida's Constitution of 1838, in which Florida agreed with Congress to be a "Free and Independent State." According to William C. Davis, "protection of slavery" was "the explicit reason" for Florida's declaring of secession, as well as the creation of the Confederacy itself.

Confederate authorities used slaves as teamsters to transport supplies and as laborers in salt works and fisheries. Many Florida slaves working in these coastal industries escaped to the relative safety of Union-controlled enclaves during the

In January 1861, nearly all delegates in the Florida Legislature approved an ordinance of secession, declaring Florida to be "a sovereign and independent nation"—an apparent reassertion to the preamble in Florida's Constitution of 1838, in which Florida agreed with Congress to be a "Free and Independent State." According to William C. Davis, "protection of slavery" was "the explicit reason" for Florida's declaring of secession, as well as the creation of the Confederacy itself.

Confederate authorities used slaves as teamsters to transport supplies and as laborers in salt works and fisheries. Many Florida slaves working in these coastal industries escaped to the relative safety of Union-controlled enclaves during the

The Unsavory Story of Industrially Grown Tomatoes

/ref> The

Slavery in Florida is more central to Florida's history than it is to almost any other state. Florida's purchase by the United States from Spain in 1819 (effective 1821) was primarily a measure to strengthen the system of slavery on Southern plantations, by denying potential runaways the formerly safe haven of Florida.

Few enslaved Africans were imported into Florida from Cuba in the period of Spanish colonial rule, as there was little for them to do—no mines, no plantations. Starting in 1687, slaves escaping from English colonies to the north were freed when they reached Florida and accepted Catholic baptism. Black slavery in the region was widely established after Florida came under

Slavery in Florida is more central to Florida's history than it is to almost any other state. Florida's purchase by the United States from Spain in 1819 (effective 1821) was primarily a measure to strengthen the system of slavery on Southern plantations, by denying potential runaways the formerly safe haven of Florida.

Few enslaved Africans were imported into Florida from Cuba in the period of Spanish colonial rule, as there was little for them to do—no mines, no plantations. Starting in 1687, slaves escaping from English colonies to the north were freed when they reached Florida and accepted Catholic baptism. Black slavery in the region was widely established after Florida came under British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

then American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

control. Slavery in Florida was theoretically abolished by the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War, Civil War. The Proclamation c ...

issued by President Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, though as the state was then part of the Confederacy this had little immediate effect.

Slavery in Florida did not end abruptly on one specific day. As news arrived of the end of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

and the collapse of the Confederacy in the spring of 1865, slavery unofficially ended, as there were no more slave catcher

In the United States a slave catcher was a person employed to track down and return escaped slaves to their enslavers. The first slave catchers in the Americas were active in European colonies in the West Indies during the sixteenth century. I ...

s or other authority to enforce the peculiar institution

''The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South'' is a non-fiction book about slavery published in 1956, by Kenneth M. Stampp of the University of California, Berkeley and other universities. The book describes and analyzes multiple ...

. Newly emancipated African Americans departed their plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

, often in search of relatives who were separated from their family. The end of slavery was made formal by the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865. Some of the characteristics of slavery, such as inability to leave an abusive situation, continued under sharecropping

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

, convict leasing

Convict leasing was a system of forced penal labor which was practiced historically in the Southern United States, the laborers being mainly African-American men; it was ended during the 20th century. (Convict labor in general continues; f ...

, and vagrancy laws

Vagrancy is the condition of homelessness without regular employment or income. Vagrants (also known as bums, vagabonds, rogues, tramps or drifters) usually live in poverty and support themselves by begging, scavenging, petty theft, temporar ...

. In the 20th and 21st centuries, conditions approximating slavery are found among marginal immigrant populations, especially migrant farm workers

A migrant worker is a person who migrates within a home country or outside it to pursue work. Migrant workers usually do not have the intention to stay permanently in the country or region in which they work.

Migrant workers who work outsi ...

and trafficked sex worker

A sex worker is a person who provides sex work, either on a regular or occasional basis. The term is used in reference to those who work in all areas of the sex industry.Oxford English Dictionary, "sex worker"

According to one view, sex work i ...

s.

Slavery before arrival of the Europeans

Enslavement predates the period ofEuropean colonization

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the modern sense be ...

and was practiced by various indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

. Florida had some of the first African slaves in what is now the United States in 1526-1565, as well as the first emancipation of escaping slaves in 1687 and the first settlement of free blacks in 1735.

Spanish rule

First Spanish occupation (1536–1763)

The first enslaved African in Florida,

The first enslaved African in Florida, Estevanico

Estevanico ("Little Stephen"; modern spelling Estebanico; –1539), also known as Esteban de Dorantes or Mustafa Azemmouri (مصطفى الزموري), was the first African to explore North America.

Estevanico first appears as a slave in Portu ...

("Little Steven"), was brought to the area in 1528 Above it says 1526. as part of the Narváez expedition

The Narváez expedition was a Spanish journey of exploration and colonization started in 1527 that intended to establish colonial settlements and garrisons in Florida. The expedition was initially led by Pánfilo de Narváez, who died in 1528. M ...

, which then continued on to Texas. More African slaves arrived in Florida in 1539 with Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and ''conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

.

When the Spanish founded the colonial settlement of '' San Agustín'' in 1565, the site already had enslaved Native Americans, whose ancestors had migrated from Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

. The Spaniards did not bring many slaves to Florida as there was no work for them to do—no mines and no plantations. For the same reason very few Spaniards came to Florida; there were only three towns in the colony, supporting military/naval outposts: St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

, St. Marks, and what is today Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

. Under Spanish colonial rule, the enslaved in Florida had rights. They could marry, own property, and purchase their own freedom. Free blacks, as long as they were Catholic, were not subject to legal discrimination. No one was born into slavery. Mixed "race" marriages were not illegal, and mixed "race" children could inherit property.

In October 1687, eleven enslaved Africans made their way from Carolina to Florida in a stolen canoe, and were emancipated by the Spanish authorities. A year later, Major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

William Dunlop, an officer in the Carolinaa militia, arrived in Florida to ask for compensation for Spanish attacks on Carolina and the return of the Africans to their enslaver, Governor Joseph Morton. The Spanish chose to compensate Morton instead, submitting a report to King Charles II on the event. On November 7, 1693, Charles II issued a decree freeing all slaves escaping from English North America who accepted Catholicism, similar to the May 29, 1680 Spanish decree for slaves escaping from the Lesser Antilles and the September 3, 1680 and June 1, 1685 decrees for escaping French slaves.

In the early 1700s, Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

was a hotbed for the raiding Native Americans from the northern Carolina and Georgia areas. Though they were left alone for the most part by one of the original raiding groups, the Westos, Spanish Florida was heavily targeted by the later raiding groups, the Yamasee

The Yamasees (also spelled Yamassees or Yemassees) were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans who lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida. The Yamas ...

and Creek. These raids, in which villages were destroyed and local Native Americans were either killed or captured to be later sold as slaves to English colonists, drove the local Native Americans to the hands of the Spanish, who attempted to protect them as best they could from the raids. However, the strength of the Spanish dwindled and as the raids continued the Spanish and Spanish-allied natives were forced to retreat farther and farther back into the peninsula. The raids were so frequent that there were few natives left to capture, and so the Yamasee and the Creek began bringing fewer and fewer slaves to the Carolina colonies and were unable to effectively continue the trade. The retreat of the Spanish was only ended when the Yamasee and Creek entered what would later be known as the Yamasee War with the Carolina colony.

Since 1688,

Since 1688, Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

had attracted numerous fugitive slaves

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freed ...

who escaped from the British North American colonies

The British colonization of the Americas was the history of establishment of control, settlement, and colonization of the continents of the Americas by England, Scotland and, after 1707, Great Britain. Colonization efforts began in the late ...

. Once the slaves reached Florida, the Spanish freed them if they converted to Roman Catholicism; males of age had to complete a military obligation. Many settled in Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose

Fort Mose Historic State Park (originally known as Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, and later Fort Mose; alternatively, Fort Moosa or Fort Mossa), is a former Spanish fort in St. Augustine, Florida. In 1738, the governor of Spanish Florida, M ...

, the first settlement of free blacks in North America, near St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

. The church started recording baptisms and deaths there in 1735, and a fort was built in 1738, part of the perimeter defenses of San Agustin. The freed slaves knew the border areas well and led military raids, under their own black officers, against the Carolinas, and against Georgia, founded in 1731. Another smaller group settled along the Apalachicola River

The Apalachicola River is a river, approximately 160 mi (180 km) long in the state of Florida. The river's large watershed, known as the ACF River Basin, drains an area of approximately into the Gulf of Mexico. The distance to its far ...

in remote northwest Florida

The Florida Panhandle (also West Florida and Northwest Florida) is the northwestern part of the U.S. state of Florida; it is a salient roughly long and wide, lying between Alabama on the north and the west, Georgia on the north, and the G ...

, centered on Prospect Bluff, future site of the famous Negro Fort

Negro Fort (African Fort) was a short-lived fortification built by the British in 1814, during the War of 1812, in a remote part of what was at the time Spanish Florida. It was intended to support a never-realized British attack on the U.S. via ...

.

British Florida (1763–1783)

Second Spanish occupation (1783–1821)

The former slaves also found refuge among the Creek andSeminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

, Native Americans who had established settlements in Florida at the invitation of the Spanish government. In 1771, Governor John Moultrie wrote to the Board of Trade

The Board of Trade is a British government body concerned with commerce and industry, currently within the Department for International Trade. Its full title is The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of ...

that "It has been a practice for a good while past, for negroes to run away from their Masters, and get into the Indian towns, from whence it proved very difficult to get them back." When British colonial officials in Florida pressured the Native Americans to return the fugitive slaves, they replied that they had "merely given hungry people food, and invited the slaveholders to catch the runaways themselves."Miller, E: "St. Augustine's British Years," ''The Journal of the St. Augustine Historical Society,'' 2001, p. 38.

After the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, slaves from the State of Georgia

Georgia is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee and North Carolina; to the northeast by South Carolina; to the southeast by the Atlantic Ocean; to the south by Florida; and to the west ...

and the South Carolina Low Country

The Lowcountry (sometimes Low Country or just low country) is a geographic and cultural region along South Carolina's coast, including the Sea Islands. The region includes significant salt marshes and other coastal waterways, making it an import ...

continued to escape to Florida. The U.S. Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory, including the 1817–1818 campaign by Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

that became known as the First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostiliti ...

. The United States afterwards effectively controlled East Florida

East Florida ( es, Florida Oriental) was a colony of Great Britain from 1763 to 1783 and a province of Spanish Florida from 1783 to 1821. Great Britain gained control of the long-established Spanish colony of ''La Florida'' in 1763 as part of ...

. According to Secretary of State John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

, the US had to take action there because Florida had become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them." Spain requested British intervention, but London declined to assist Spain in the negotiations. Some of President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

's cabinet demanded Jackson's immediate dismissal, but Adams realized that it put the U.S. in a favorable diplomatic position, allowing him to negotiate very favorable terms.

The Spanish had established outposts in Florida to prevent others from having safe ports to attack Spanish treasure fleets in the Caribbean and in the strait between Florida and the Bahamas. Florida did not produce anything the Spaniards wanted. The three garrisons were a financial drain, and it was not felt desirable to send settlers or additional garrisons. The Crown decided to cede the territory to the United States. It accomplished this through the Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and define ...

of 1819, which took effect in 1821.

Treatment of Blacks under Spanish rule

Under the Spanish, enslaved workers had rights: to marry, to own property, to buy their own freedom. They were not chattel. Free Blacks, as long as they accepted Catholicism, were not subject to legal discrimination. No one was born into slavery. Mixed "race" marriages were not illegal, and mixed "race" children could inherit property, as laterZephaniah Kingsley

Zephaniah Kingsley Jr. (December 4, 1765 – September 14, 1843) was a Quaker, born in England, who moved as a child with his family to South Carolina, and became a planter, slave trader, and merchant. He built four plantations in the Spanish co ...

's inheritors had to fight successfully for.

Zephaniah Kingsley

During the second Spanish period, when slaves continued to escape from their British, then American owners and take refuge in Florida, the North American slave trade was to a large extent centered on Florida. Besides those seeking to recover escaped slaves, the newly enslaved could be freely imported to Florida from Africa, and planters and their representatives went to Florida to buy them and then smuggle them into the U.S. At the center of Florida's slave trade was the colorful trader and slavery defender, QuakerZephaniah Kingsley

Zephaniah Kingsley Jr. (December 4, 1765 – September 14, 1843) was a Quaker, born in England, who moved as a child with his family to South Carolina, and became a planter, slave trader, and merchant. He built four plantations in the Spanish co ...

, owner of slaving vessels (boats). He treated his enslaved well, allowed them to save for and buy their freedom (at a 50% discount), and taught them crafts like carpentry, for which reason his highly-trained, well-behaved slaves sold for a premium. After Florida became American, Kingsley, after trying unsuccessfully to prevent Florida from treating free Blacks as unwelcome (see below), left for what at the time was Haiti (today the Dominican Republic).

Territorial Florida, under American rule (1821–1845)

Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

became an organized territory of the United States on February 22, 1821. (See Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and define ...

.) Slavery continued to be permitted; however, Spanish racial policies were replaced with a rigid set of laws that assumed that all Black persons, slave or free, were uncivilized and inferior to whites, and suitable only for slavery.

The free Blacks and Indian slaves, Black Seminoles

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles are Native American-Africans associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood descendants of the Seminole people, free Africans, and escaped slaves, who allied with Seminole ...

, living near St. Augustine, fled to Havana, Cuba, to avoid coming under US control. Some Seminole also abandoned their settlements and moved further south. Hundreds of Black Seminoles and fugitive slaves escaped in the early nineteenth century from Cape Florida to the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

, where they settled on Andros Island

Andros Island is an archipelago within the Bahamas, the largest of the Bahamian Islands. Politically considered a single island, Andros in total has an area greater than all the other 700 Bahamian islands combined. The land area of Andros consis ...

, founding Nicholls Town

Nicholls Town is a town located in North Andros, part of Andros island in the Bahamas. The town features a sweeping beachfront.

It is named for Edward Nicolls, an Anglo-Irish military leader in the Caribbean in the early 19th century. He was an a ...

, named for the Anglo-Irish commander and abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

who fostered their escape, Edward Nicolls

Sir Edward Nicolls ( – 5 February 1865) was an Anglo-Irish officer of the Royal Marines. Known as "Fighting Nicolls", he had a distinguished military career. According to his obituary in ''The Times'', he was "in no fewer than 107 ...

.

Free negros, perceived as dangerous, were unwanted

In 1827 free negros were prohibited from entering Florida, and in 1828 those already there were prohibited from assembling in public. In 1829 a statute required a fine of $200 () for every personmanumit

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

ted (set free), and required the person freed to leave the Territory within 30 days.

In antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ar ...

Florida, "Southerners came to believe that the only successful means of removing the threat of free Negroes was to expel them from the southern states or to change their status from free persons to... slaves." Free Negroes were perceived as "an evil of no ordinary magnitude," undermining the system of slavery. Slaves had to be shown that there was no advantage in being free; thus, free negroes became victims of the slaveholders' fears. Legislation became more forceful; the free negro had to accept his new role or leave the state, as in fact half the black population of Pensacola and St. Augustine immediately did (they left the country). Some citizens of Leon County, Florida

Leon County is a county in the Panhandle of the U.S. state of Florida. It was named after the Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León. As of the 2020 census, the population was 292,198.

The county seat is Tallahassee, which is also the state ...

, Florida's most populous and wealthiest county, which wealth was because Leon County had more slaves than any other county in Florida, petitioned the General Assembly to have all free negroes removed from the state. Legislation passed in 1847 required all free Negroes to have a white person as legal guardian; in 1855, an act was passed which prevented free Negroes from entering the state. Above it says 1827. "In 1861, an act was passed requiring all free Negroes in Florida to register with the judge of probate in whose county they resided. The Negro, when registering, had to give his name, age, color, sex, and occupation, and had to pay one dollar to register.... All Negroes over twelve years of age had to have a guardian approved by the probate judge.... The guardian could be sued for any crime committed by the Negro; the Negro could not be sued. Under the new law, any free Negro or mulatto who did not register with the nearest probate judge was classified as a slave and became the lawful property of any white person who claimed possession."

In 1830, free Blacks were 5.2% of Florida's African-American population; by 1860 they had declined to 1.5%.

Florida a slave state (1845–1861)

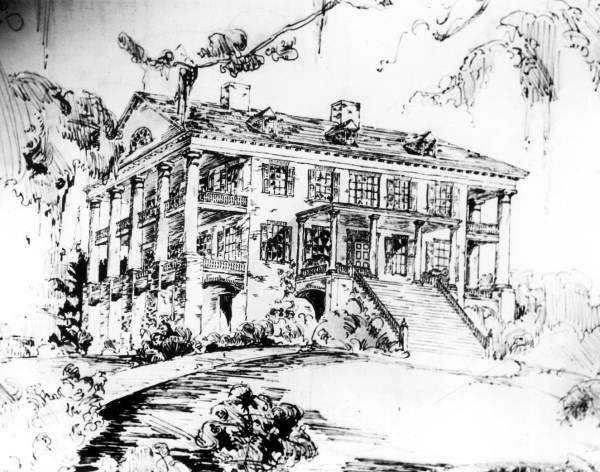

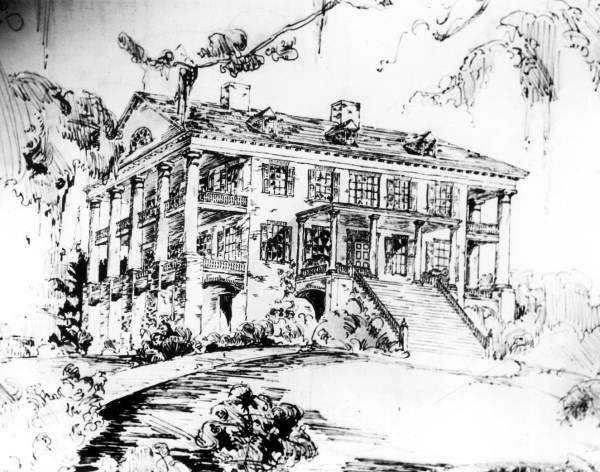

American settlers began to establish

American settlers began to establish cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

in northern Florida, which required numerous laborers, which they supplied by buying slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in the domestic market. On March 3, 1845, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

became a slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. Almost half the state's population were enslaved African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

working on large cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

and sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or do ...

plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

, between the Apalachicola and Suwannee Rivers in the north-central part of the state. Like the people who owned them, many slaves had come from the coastal areas of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

and The Carolinas

The Carolinas are the U.S. states of North Carolina and South Carolina, considered collectively. They are bordered by Virginia to the north, Tennessee to the west, and Georgia to the southwest. The Atlantic Ocean is to the east.

Combining Nor ...

; they were part of the Gullah-Geechee culture of the South Carolina Lowcountry

The Lowcountry (sometimes Low Country or just low country) is a geographic and cultural region along South Carolina's coast, including the Sea Islands. The region includes significant salt marshes and other coastal waterways, making it an impor ...

. Others were enslaved African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

from the Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern and lower Midwestern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, econom ...

, who had been sold to traders taking slaves to the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the wa ...

. By 1860, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

had 140,424 people, of whom 44% were enslaved, and fewer than 1,000 free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

. Their labor accounted for 85% of the state's cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

production. The ''1860 Census'' also indicated that in Leon County, which was the center both of the Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

slave trade and of their plantation industry (see Plantations of Leon County), slaves constituted 73% of the population. As elsewhere, their value was greater than all the land of the county put together. (References in History of Tallahassee, Florida#Black history.)

Florida secedes and becomes Confederate state (1861–1865)

In January 1861, nearly all delegates in the Florida Legislature approved an ordinance of secession, declaring Florida to be "a sovereign and independent nation"—an apparent reassertion to the preamble in Florida's Constitution of 1838, in which Florida agreed with Congress to be a "Free and Independent State." According to William C. Davis, "protection of slavery" was "the explicit reason" for Florida's declaring of secession, as well as the creation of the Confederacy itself.

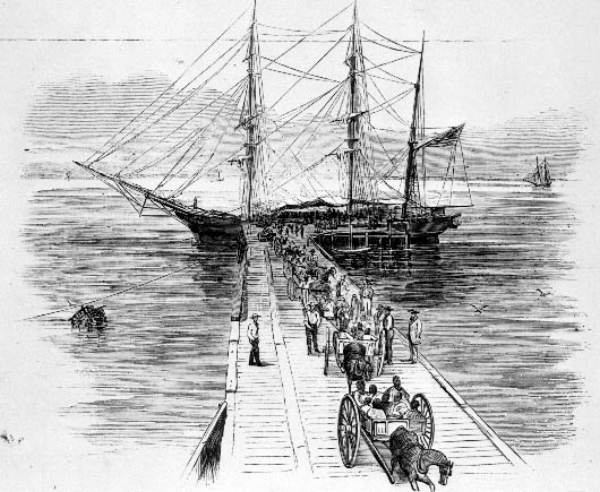

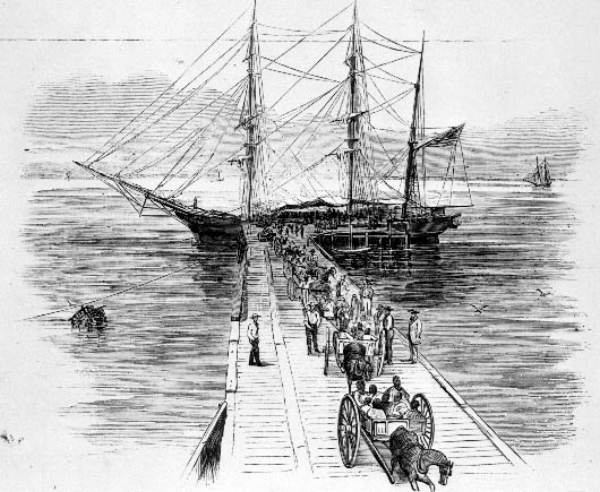

Confederate authorities used slaves as teamsters to transport supplies and as laborers in salt works and fisheries. Many Florida slaves working in these coastal industries escaped to the relative safety of Union-controlled enclaves during the

In January 1861, nearly all delegates in the Florida Legislature approved an ordinance of secession, declaring Florida to be "a sovereign and independent nation"—an apparent reassertion to the preamble in Florida's Constitution of 1838, in which Florida agreed with Congress to be a "Free and Independent State." According to William C. Davis, "protection of slavery" was "the explicit reason" for Florida's declaring of secession, as well as the creation of the Confederacy itself.

Confederate authorities used slaves as teamsters to transport supplies and as laborers in salt works and fisheries. Many Florida slaves working in these coastal industries escaped to the relative safety of Union-controlled enclaves during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. Beginning in 1862, Union military activity in East and West Florida encouraged slaves in plantation areas to flee their owners in search of freedom. Some worked on Union ships and, beginning in 1863, with the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War, Civil War. The Proclamation c ...

, more than a thousand enlisted as soldiers and sailors in the United States Colored Troops

The United States Colored Troops (USCT) were regiments in the United States Army composed primarily of African-American ( colored) soldiers, although members of other minority groups also served within the units. They were first recruited durin ...

of the military.

Escaped and freed slaves provided Union commanders with valuable intelligence about Confederate troop movements. They also passed back news of Union advances to the men and women who remained enslaved in Confederate-controlled Florida. Planter fears of slave uprisings increased as the war went on.Murphree (2008)

In May 1865, Federal control was re-established, and slavery abolished.

Human trafficking in the 20th and 21st centuries

AfterCalifornia

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

and New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, Florida has the most human trafficking cases in the United States. Florida has had cases of sex trafficking, domestic servitude, and forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

.

Florida has a large agricultural economy and a large immigrant population, which has made it a prime environment for forced labor, particularly in the tomato industry. Concerted efforts have led to the freeing of thousands of slaves in recent years./ref> The

National Human Trafficking Resource Center

Polaris is a nonprofit non-governmental organization that works to combat and prevent sex and labor trafficking in North America. The organization's 10-year strategy is built around the understanding that human trafficking does not happen in ...

reported receiving 1,518 calls and emails in 2015 about human trafficking in Florida.

See also

* Indian slave trade in the American Southeast#Slavery in Florida *Negro Fort

Negro Fort (African Fort) was a short-lived fortification built by the British in 1814, during the War of 1812, in a remote part of what was at the time Spanish Florida. It was intended to support a never-realized British attack on the U.S. via ...

* Ocoee massacre

*Perry massacre

The Perry massacre was a racially motivated conflict in Perry, Florida, in December 1922. Whites killed four black men, including Charles Wright, who was lynched by being burned at the stake, and they also destroyed several buildings in the black ...

*Rosewood massacre

The Rosewood massacre was a racially motivated massacre of black people and the destruction of a black town that took place during the first week of January 1923 in rural Levy County, Florida, United States. At least six black people and two whit ...

* Plantations of Leon County, Florida

References

Further reading (most recent last)

* * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Slavery In Florida African-American history of Florida Native American history of Florida Pre-statehood history of Florida History of racism in Florida Floria