History of insurance on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of insurance traces the development of the modern business of

Achaemenian monarchs in

Achaemenian monarchs in

Insurance became more sophisticated in

Insurance became more sophisticated in

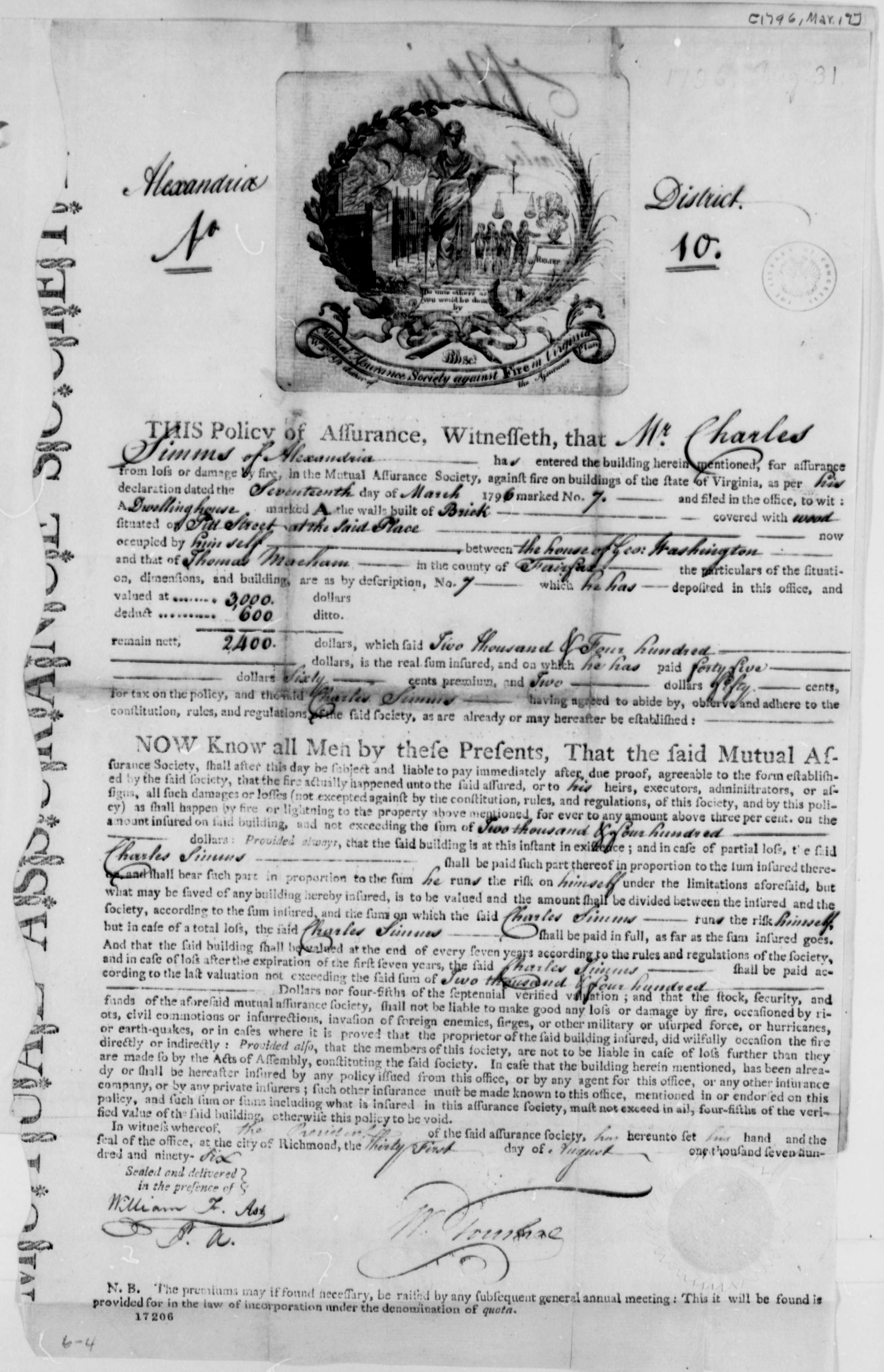

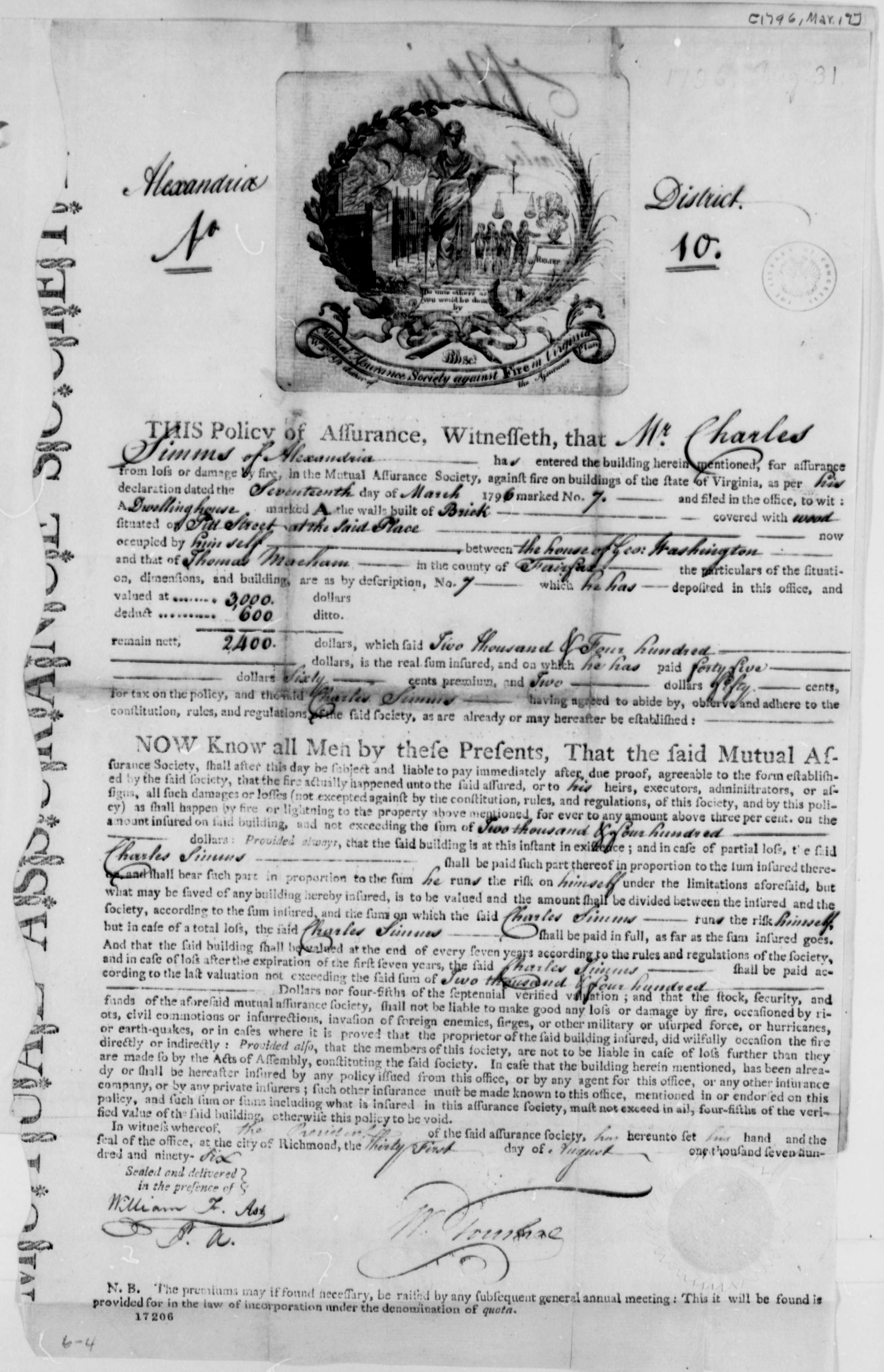

In the wake of this first successful venture, many similar companies were founded in the following decades. Initially, each company employed its own fire department to prevent and minimize the damage from conflagrations on properties insured by them. They also began to issue ' Fire insurance marks' to their customers. These would be displayed prominently above the main door of the property and allowed the insurance company to positively identify properties that had taken out insurance with them. One such notable company was the

In the wake of this first successful venture, many similar companies were founded in the following decades. Initially, each company employed its own fire department to prevent and minimize the damage from conflagrations on properties insured by them. They also began to issue ' Fire insurance marks' to their customers. These would be displayed prominently above the main door of the property and allowed the insurance company to positively identify properties that had taken out insurance with them. One such notable company was the

At the same time, the first insurance schemes for the

At the same time, the first insurance schemes for the

The first

The first

In the late 19th century, "accident insurance" began to become available. This operated much like modern ''disability'' insurance. The first company to offer accident insurance was the Railway Passengers Assurance Company, formed in 1848 in England to insure against the rising number of fatalities on the nascent

In the late 19th century, "accident insurance" began to become available. This operated much like modern ''disability'' insurance. The first company to offer accident insurance was the Railway Passengers Assurance Company, formed in 1848 in England to insure against the rising number of fatalities on the nascent

In Britain more extensive legislation was introduced by the

In Britain more extensive legislation was introduced by the

insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

against risks, especially regarding cargo

Cargo consists of bulk goods conveyed by water, air, or land. In economics, freight is cargo that is transported at a freight rate for commercial gain. ''Cargo'' was originally a shipload but now covers all types of freight, including trans ...

, property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

, death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

, automobile accidents, and medical treatment.

The insurance industry

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

helps to eliminate risks (as when fire-insurance providers demand the implementation of safe practices and the installation of hydrants), spreads risks from individuals to the larger community, and provides an important source of long-term finance for both the public

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichk ...

and private sector

The private sector is the part of the economy, sometimes referred to as the citizen sector, which is owned by private groups, usually as a means of establishment for profit or non profit, rather than being owned by the government.

Employment

The ...

s.

Ancient era

In December 1901 and January 1902, at the direction of archaeologistJacques de Morgan

Jean-Jacques de Morgan (3 June 1857, Huisseau-sur-Cosson, Loir-et-Cher – 14 June 1924) was a French mining engineer, geologist, and archaeologist. He was the director of antiquities in Egypt during the 19th century, and excavated in Memph ...

, Father

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. An adoptive fathe ...

Jean-Vincent Scheil

Father Jean-Vincent Scheil (born 10 June 1858, Kœnigsmacker – died 21 September 1940, Paris) was a French Dominican scholar and Assyriologist. He is credited as the discoverer of the Code of Hammurabi in Persia. In 1911 he came into possessi ...

, OP found a 2.25 meter

The metre (British spelling) or meter (American spelling; see spelling differences) (from the French unit , from the Greek noun , "measure"), symbol m, is the primary unit of length in the International System of Units (SI), though its pref ...

(or 88.5 inch) tall basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90 ...

or diorite

Diorite ( ) is an intrusive igneous rock formed by the slow cooling underground of magma (molten rock) that has a moderate content of silica and a relatively low content of alkali metals. It is intermediate in composition between low-sili ...

stele in three pieces inscribed with 4,130 lines of cuneiform law

Cuneiform law refers to any of the legal codes written in cuneiform script, that were developed and used throughout the ancient Middle East among the Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Elamites, Hurrians, Kassites, and Hittites. The Code of ...

dictated by Hammurabi

Hammurabi (Akkadian: ; ) was the sixth Amorite king of the Old Babylonian Empire, reigning from to BC. He was preceded by his father, Sin-Muballit, who abdicated due to failing health. During his reign, he conquered Elam and the city-states ...

(c. 1792–1750 BC) of the First Babylonian Empire

The Old Babylonian Empire, or First Babylonian Empire, is dated to BC – BC, and comes after the end of Sumerian power with the destruction of the Third Dynasty of Ur, and the subsequent Isin-Larsa period. The chronology of the first dynasty ...

in the city of Shush, Iran

Shush ( fa, شوش; also Romanized as Shūsh, Shoosh, and by name of the ancient nearby city: Sūsa) is a city and capital of Shush County, Khuzestan Province, Iran. At the 2006 census, its population was 53,897, in 10,689 families. Shush is l ...

. ''Codex Hammurabi'' Law 100 stipulated repayment by a debtor of a loan

In finance, a loan is the lending of money by one or more individuals, organizations, or other entities to other individuals, organizations, etc. The recipient (i.e., the borrower) incurs a debt and is usually liable to pay interest on that ...

to a creditor on a schedule with a maturity date

Maturity or immaturity may refer to:

* Adulthood or age of majority

* Maturity model

** Capability Maturity Model, in software engineering, a model representing the degree of formality and optimization of processes in an organization

* Developmen ...

specified in written

Writing is a medium of human communication which involves the representation of a language through a system of physically inscribed, mechanically transferred, or digitally represented symbols.

Writing systems do not themselves constitute h ...

contractual term

A contractual term is "any provision forming part of a contract". Each term gives rise to a contractual obligation, the breach of which may give rise to litigation. Not all terms are stated expressly and some terms carry less legal gravity as th ...

s. Laws 101 and 102 stipulated that a shipping agent

A shipping agency or shipping agent is the designated person or agency held responsible for handling shipments and cargo, and the general interests of its customers, at ports and harbors worldwide, on behalf of ship owners, managers, and charte ...

, factor

Factor, a Latin word meaning "who/which acts", may refer to:

Commerce

* Factor (agent), a person who acts for, notably a mercantile and colonial agent

* Factor (Scotland), a person or firm managing a Scottish estate

* Factors of production, suc ...

, or ship charterer was only required to repay the principal of a loan to their creditor in the event of a net income loss or a total loss

In insurance claims, a total loss or write-off is a situation where the lost value, repair cost or salvage cost of a damaged property exceeds its insured value, and simply replacing the old property with a new equivalent is more cost-effect ...

due to an Act of God. Law 103 stipulated that an agent, factor, or charterer was by '' force majeure'' relieved of their liability for an entire loan in the event that the agent, factor, or charterer was the victim of theft

Theft is the act of taking another person's property or services without that person's permission or consent with the intent to deprive the rightful owner of it. The word ''theft'' is also used as a synonym or informal shorthand term for som ...

during the term of their charterparty

A charterparty (sometimes charter-party) is a maritime contract between a shipowner and a "charterer" for the hire of either a ship for the carriage of passengers or cargo, or a yacht for pleasure purposes.

Charter party is a contract of carriag ...

upon provision of an affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or '' deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by law. Such a stateme ...

of the theft to their creditor.

''Codex Hammurabi'' Law 104 stipulated that a carrier (agents, factors, or charterers) issue a waybill

A waybill ( UIC) is a document issued by a carrier giving details and instructions relating to the shipment of a consignment of goods. Typically it will show the names of the consignor and consignee, the point of origin of the consignment, its d ...

and invoice

An invoice, bill or tab is a commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer relating to a sale transaction and indicating the products, quantities, and agreed-upon prices for products or services the seller had provided the buyer.

Payment ...

for a contract of carriage

A contract of carriage is a contract between a carrier of goods or passengers and the consignor, consignee or passenger. Contracts of carriage typically define the rights, duties and liabilities of parties to the contract, addressing topics such ...

to a consignee

{{Admiralty law

In a contract of carriage, the consignee is the entity who is financially responsible (the buyer) for the receipt of a shipment. Generally, but not always, the consignee is the same as the receiver.

If a sender dispatches an ...

outlining contractual terms for sales

Sales are activities related to selling or the number of goods sold in a given targeted time period. The delivery of a service for a cost is also considered a sale.

The seller, or the provider of the goods or services, completes a sale in ...

, commissions, and laytime

In commercial shipping, laytime is the amount of time allowed in a voyage charter for the loading and unloading of cargo.

Under a voyage charter or time charter, the shipowner is responsible for operating the vessel, and the master and crew are ...

and receive a bill of parcel and lien

A lien ( or ) is a form of security interest granted over an item of property to secure the payment of a debt or performance of some other obligation. The owner of the property, who grants the lien, is referred to as the ''lienee'' and the per ...

authorizing consignment from the consignee. Law 105 stipulated that claims for losses filed by agents, factors, and charterers without receipts were without standing

Standing, also referred to as orthostasis, is a position in which the body is held in an ''erect'' ("orthostatic") position and supported only by the feet. Although seemingly static, the body rocks slightly back and forth from the ankle in the s ...

. Law 126 stipulated that filing a false claim of a loss was punishable by law. Law 235 stipulated that a shipbuilder

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to befor ...

was liable within one year of construction for the replacement of an unseaworthy vessel to the ship-owner

A ship-owner is the owner of a merchant vessel (commercial ship) and is involved in the shipping industry. In the commercial sense of the term, a shipowner is someone who equips and exploits a ship, usually for delivering cargo at a certain fre ...

that was lost

Lost may refer to getting lost, or to:

Geography

*Lost, Aberdeenshire, a hamlet in Scotland

* Lake Okeechobee Scenic Trail, or LOST, a hiking and cycling trail in Florida, US

History

*Abbreviation of lost work, any work which is known to have bee ...

during the term of a charterparty. Laws 236 and 237 stipulated that a sea captain, ship-manager, or charterer was liable for the replacement of a lost vessel and cargo to the shipowner and consignees respectively that was negligently operated during the term of a charterparty. Law 238 stipulated that a captain, manager, or charterer that saved a ship from total loss was only required to pay one-half the value of the ship to the shipowner. Law 240 stipulated that the owner of a cargo ship that destroyed a passenger ship in a collision

In physics, a collision is any event in which two or more bodies exert forces on each other in a relatively short time. Although the most common use of the word ''collision'' refers to incidents in which two or more objects collide with great fo ...

was liable for replacement of the passenger ship and any cargo it held upon provision of an affidavit of the collision by the owner of the passenger ship.

In 1816, an archeological excavation in Minya, Egypt (under an Eyalet of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

) produced a Nerva–Antonine dynasty-era tablet from the ruins of the Temple of Antinous in Antinoöpolis, Aegyptus that prescribed the rules and membership dues of a burial society A burial society is a type of benefit/friendly society. These groups historically existed in England and elsewhere, and were constituted for the purpose of providing by voluntary subscriptions for the funeral expenses of the husband, wife or child ...

''collegium

A (plural ), or college, was any association in ancient Rome that acted as a legal entity. Following the passage of the ''Lex Julia'' during the reign of Julius Caesar as Consul and Dictator of the Roman Republic (49–44 BC), and their rea ...

'' established in Lanuvium

Lanuvium, modern Lanuvio, is an ancient city of Latium vetus, some southeast of Rome, a little southwest of the Via Appia.

Situated on an isolated hill projecting south from the main mass of the Alban Hills, Lanuvium commanded an extensive vie ...

, Italia

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the Italy (geographical region) ...

in approximately 133 AD during the reign of Hadrian (117–138) of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

. In 1851, future U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

Associate Justice

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some sta ...

Joseph P. Bradley

Joseph Philo Bradley (March 14, 1813 – January 22, 1892) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1870 to 1892. He was also a member of the Electoral Commission that decided t ...

(1870–1892), once employed as an actuary for the Mutual Benefit Life Insurance Company

The Mutual Benefit Life Insurance Company was a life insurance company that was chartered in 1845 and based in Newark in Essex County, New Jersey, United States. The company was headed by Frederick Frelinghuysen (1848–1924). The company w ...

, submitted an article to the '' Journal of the Institute of Actuaries'' detailing an historical account of a Severan dynasty

The Severan dynasty was a Roman imperial dynasty that ruled the Roman Empire between 193 and 235, during the Roman imperial period. The dynasty was founded by the emperor Septimius Severus (), who rose to power after the Year of the Five Empero ...

-era life table

In actuarial science and demography, a life table (also called a mortality table or actuarial table) is a table which shows, for each age, what the probability is that a person of that age will die before their next birthday ("probability of death ...

compiled by the Roman jurist Ulpian

Ulpian (; la, Gnaeus Domitius Annius Ulpianus; c. 170223? 228?) was a Roman jurist born in Tyre. He was considered one of the great legal authorities of his time and was one of the five jurists upon whom decisions were to be based according to ...

in approximately 220 AD during the reign of Elagabalus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, 204 – 11/12 March 222), better known by his nickname "Elagabalus" (, ), was Roman emperor from 218 to 222, while he was still a teenager. His short reign was conspicuous for s ...

(218–222) that was included in the second volume of the codification of laws ordered by Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renova ...

(527–565) of the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

, the '' Digesta seu Pandectae'' (533).

Additionally, the ''Digesta'' included a legal opinion written by the Roman jurist Paulus at the beginning of the Crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis (AD 235–284), was a period in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed. The crisis ended due to the military victories of Aurelian and with the ascensio ...

in 235 AD on the ''Lex Rhodia

Lex or LEX may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Lex'', a daily featured column in the ''Financial Times''

Games

* Lex, the mascot of the word-forming puzzle video game ''Bookworm''

* Lex, the protagonist of the word-forming puzzle video ga ...

'' ("Rhodian law") that articulates the general average principle of marine insurance

Marine insurance covers the physical loss or damage of ships, cargo, terminals, and any transport by which the property is transferred, acquired, or held between the points of origin and the final destination. Cargo insurance is the sub-branch o ...

established on the island of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

in approximately 1000 to 800 BC as a member of the Doric Hexapolis, plausibly by the Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns during the proposed Dorian invasion and emergence of the purported Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the Fren ...

during the Greek Dark Ages (c. 1100–c. 750) that led to the proliferation of the Doric Greek dialect

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety of a language that is a ...

. The law of general average constitutes the fundamental principle that underlies all insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

.

Insurance in some forms dates back to prehistory. Initially, people sold goods in their own villages or gathering places. However, with the passage of time, they turned to nearby villages to sell. Two types of economies existed in human societies: natural

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

or non-monetary economies (using barter

In trade, barter (derived from ''baretor'') is a system of exchange in which participants in a transaction directly exchange goods or services for other goods or services without using a medium of exchange, such as money. Economists disti ...

and trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct excha ...

with no centralized nor standardized set of financial instruments) and monetary economies (with markets, currency

A currency, "in circulation", from la, currens, -entis, literally meaning "running" or "traversing" is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins.

A more general ...

, financial instruments

Financial instruments are monetary contracts between parties. They can be created, traded, modified and settled. They can be cash (currency), evidence of an ownership interest in an entity or a contractual right to receive or deliver in the form ...

and so on). Insurance in non-monetary economies entails agreements of mutual aid. Such economies can potentially foster institutions such as co-operatives, guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

s and proto-state

A quasi-state (some times referred to as state-like entity or proto-state) is a political entity that does not represent a fully institutionalised or autonomous sovereign state.

The precise definition of ''quasi-state'' in political literature f ...

s - institutions functioning to provide mutual protection

and to encourage mutual survival in adverse circumstances.

The "pay-off" for such "insurance" need not involve financial transactions. If one family's house gets destroyed, the neighbors are committed to helping rebuild it. Public granaries

A granary is a storehouse or room in a barn for threshed grain or animal feed. Ancient or primitive granaries are most often made of pottery. Granaries are often built above the ground to keep the stored food away from mice and other animals ...

embodied another early form of insurance to indemnify against famines.

Babylonian, Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

, and Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

traders practiced methods of transferring or distributing risk in a monetary economy in the 3rd and 2nd

A second is the base unit of time in the International System of Units (SI).

Second, Seconds or 2nd may also refer to:

Mathematics

* 2 (number), as an ordinal (also written as ''2nd'' or ''2d'')

* Second of arc, an angular measurement unit, ...

millennia

A millennium (plural millennia or millenniums) is a period of one thousand years, sometimes called a kiloannum (ka), or kiloyear (ky). Normally, the word is used specifically for periods of a thousand years that begin at the starting point (ini ...

BC, respectively. Chinese merchants traversing treacherous river rapids would redistribute their wares across many vessels to limit the loss due to any single vessel's capsizing. The Babylonians developed a system recorded in the famous Code of Hammurabi, c. 1750 BC, and practiced by early Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

sailing merchants. If a merchant received a loan to fund his shipment, he would pay the lender an additional sum in exchange for the lender's guarantee to cancel the loan should the shipment be stolen or lost at sea. Concepts of insurance has been also found in 3rd century BCE Hindu scriptures such as Dharmasastra, Arthashastra and Manusmriti

The ''Manusmṛiti'' ( sa, मनुस्मृति), also known as the ''Mānava-Dharmaśāstra'' or Laws of Manu, is one of the many legal texts and constitution among the many ' of Hinduism. In ancient India, the sages often wrote thei ...

.

Achaemenian monarchs in

Achaemenian monarchs in Ancient Persia

The history of Iran is intertwined with the history of a larger region known as Greater Iran, comprising the area from Anatolia in the west to the borders of Ancient India and the Syr Darya in the east, and from the Caucasus and the Eurasian Step ...

received annual gifts (tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of land which the state conqu ...

) from the various ethnic groups under their control. This would function as an early form of political insurance, and officially bound the Persian monarch to protect the group from harm.

The ancient so-called “Rhodian Sea-Law”, applying to seafarers and merchants, included a stipulation that if a seafarer was forced to throw cargo overboard to save the ship from sinking, the loss would be reimbursed collectively by his colleagues. This is often cited as one of the earliest examples of insurance law, with some putting its origin in the Greek island of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

as early as 1000 BCE. However, the earliest references to the “Rhodian Sea-Law” appear in late Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

legal sources.

The ancient Athenian "maritime loan" advanced money for voyages with repayment being canceled if the ship was lost. In the 4th century BC, rates for the loans differed according to safe or dangerous times of year, implying an intuitive pricing of risk with an effect similar to insurance.

During the Peloponnesian Wars

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of th ...

, some Athenian slave-owners volunteered their slaves to serve as oarsmen in warships. These slave-owners paid a small yearly premium to the Athenian State, which, in case the slave was killed in action, would pay out the owner for the value of the slave.

The Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

and Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

600 BC set up guilds called "benevolent societies", which cared for the families of deceased members, as well as paying funeral expenses of members. Guilds in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

had similar practices. The Jewish Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

deals with several aspects of insuring goods

In economics, goods are items that satisfy human wants

and provide utility, for example, to a consumer making a purchase of a satisfying product. A common distinction is made between goods which are transferable, and services, which are not t ...

. Before modern-style insurance became established in the late 17th century, "friendly societies" existed in England, in which people donated amounts of money to a general sum that could be used for emergencies.

Medieval era

Sea loans (''foenus nauticum'') were common before the traditional marine insurance in medieval times, in which an investor lent his money to a traveling merchant, and the merchant would be liable to pay it back if the ship returned safely. In this way, credit and sea insurance were provided at the same time. To offset the sea risk involved, the merchant was obligated to pay a high rate of interest, in contrast to overland merchants who merely divided the profits. Pope Gregory IX condemned the ''foenus nauticum'' as usury in hisdecretal

Decretals ( la, litterae decretales) are letters of a pope that formulate decisions in ecclesiastical law of the Catholic Church.McGurk. ''Dictionary of Medieval Terms''. p. 10

They are generally given in answer to consultations but are sometimes ...

Naviganti of 1236 ( Decretales, V, XIX, 19) and commenda The commenda was a medieval contract which developed in Italy around the 10th century, and was an early form of limited partnership. The commenda was an agreement between an investing partner and a traveling partner to conduct a commercial enterpris ...

contracts were introduced in response. Under commenda contracts, investors provided funds to an entrepreneur to carry out a trade, bearing the risk of loss in exchange for a favorable share of the profits when the entrepreneur returned. By the late thirteenth century Italian merchants had begun to separate risk management from finance, accomplishing the latter with ''cambium'' contracts based on the purchase of discounted bills of exchange

A negotiable instrument is a document guaranteeing the payment of a specific amount of money, either on demand, or at a set time, whose payer is usually named on the document. More specifically, it is a document contemplated by or consisting of a ...

from merchants who did not personally go to sea. To manage the sea risk, the merchants developed the insurance loan: the merchant paid a premium to a shipowner in the form of an unenforceable loan, under an agreement that the shipowner would pay the merchant's losses if his goods did not reach their destination.

In 1293, Denis of Portugal advanced the interests of the Portuguese merchants, and set up by mutual agreement a fund called the ''Bolsa de Comércio'', the first documented form of marine insurance in Europe, approved on 10 May 1293.

In the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, the European traders traveled to sell their goods across the globe and to hedge the risk of theft or fraud by the Captain or crew also known as Risicum Gentium. However, they realized that selling this way, involves not only the risk of loss (i.e. damaged, theft or life of trader as well) but also they cannot cover the wider market. Therefore, the trend of hiring commissioned base agents across different markets emerged. In 1310 the Chamber of Assurance was established in the Flamish commercial city of Bruges.

The traders sent (export) their goods to the agents who on the behalf of traders sold them. Sending goods to the agents by road or sea involves different risks i.e. sea storms, pirate attack; goods may be damaged due to poor handling while loading and unloading, etc. Traders exploited different measures to hedge the risk involved in the exporting. Instead of sending all the goods on one ship/truck, they used to send their goods over number of vessels to avoid the total loss of shipment if the vessel was caught in a sea storm, fire, pirate, or came under enemy attacks but this was not good practice due to prolonged time and efforts involved.

Insurance is the oldest method of transferring risk, which was developed to mitigate trade/business risk. Marine insurance is very important for international trade and makes large commercial trade possible. The risk hedging instruments used to mitigate risk in medieval times were sea/marine (Mutuum) loans, commenda contract, and bill of exchanges. Nelli (1972) highlighted that commenda contract and sea loans were almost the closest substitute of marine insurance. Furthermore, he pointed out that for a half century, it was considered that the first marine insurance contract was floated in Italy on October 23, 1347; however, professor Federigo found that the first written insurance contracts date back to February 13, 1343, in Pisa. Furthermore, Italian traders spread the knowledge and use of insurance into Europe and The Mediterranean. In the fifteenth century, word policy for insurance contract became standardized. By the sixteenth century, insurance was common among Britain, France, and the Netherlands. The concept of insuring outside native countries emerged in the seventeenth century due to reduced trade or higher cost of local insurance. According to Kingston (2011), Lloyd's Coffeehouse was the prominent marine insurance marketplace in London during the eighteenth century and European/American traders used this marketplace to insure their shipments.

The rules and regulations of insurance were adopted from Italian merchants known as “Law Merchant” and initially these rules governed the marine insurance across the globe. In case of dispute, policy writer and holder choose one arbitrator each and these two arbitrators choose a third impartial arbitrator and parties were bound to accept the decision made by the majority. Because of the inability of this informal court (arbitrator) to enforce their decisions, in the sixteenth century, traders turned to formal courts to resolve their disputes. Special courts were set up to solve the disputes of marine insurance like in Genoa, insurance regulation passed to impose fine, on who did not obey the Church's prohibitions of usury (Sea loans, Commenda) in 1369. In 1435, Barcelona ordinance issued, making it mandatory for traders to turn to formal courts in case of insurance disputes. In Venice, “Consoli dei Mercanti”, specialized court to deal with marine insurance were set up in 1436. In 1520, the mercantile court of Genoa was replaced by more specialized court “Rota” which not only followed the merchant's customs but also incorporated the legal laws in it.

Separate insurance contracts (i.e., insurance policies not bundled with loans or other kinds of contracts) were invented in Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

in the 14th century, as were insurance pools backed by pledges of landed estates. The first known insurance contract dates from Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

in 1347, and in the next century maritime insurance developed widely and premiums were intuitively varied with risks.

These new insurance contracts allowed insurance to be separated from investment, a separation of roles that first proved useful in marine insurance

Marine insurance covers the physical loss or damage of ships, cargo, terminals, and any transport by which the property is transferred, acquired, or held between the points of origin and the final destination. Cargo insurance is the sub-branch o ...

. The first printed book on insurance was the legal treatise ''On Insurance and Merchants' Bets'' by Pedro de Santarém

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for ''Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, meaning ...

(Santerna), written in 1488 and published in 1552.

Modern insurance

Insurance became more sophisticated in

Insurance became more sophisticated in Enlightenment era

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

, and specialized varieties developed. Some forms of insurance developed in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

in the early decades of the 17th century. For example, the will of the English colonist Robert Hayman

Robert Hayman (14 August 1575 – November 1629) was a poet, colonist and Proprietary Governor of Bristol's Hope colony in Newfoundland.

Early life and education

Hayman was born in Wolborough near Newton Abbot, Devon, the eldest of nine ch ...

mentioned two "policies of insurance" taken out with the diocesan Chancellor of London, Arthur Duck. Of the value of £100 each, one related to the safe arrival of Hayman's ship in Guyana and the other was in regard to "one hundred pounds assured by the said Doctor Arthur Ducke on my life".

Property insurance

Hamburger Feuerkasse ( en, Hamburg Fire Office) is the first officially established fire insurance company in the world,Anzovin, p. 121 ''The first fire insurance company was the Hamburger Feuerkasse (a.k.a. Hamburger General-Feur-Cassa), established in December 1676 by the Ratsherren (city council) of Hamburg (now in Germany).'' and the oldest existing insurance enterprise available to the public, having started in 1676.Evenden, p. 4Property insurance

Property insurance provides protection against most risks to property, such as fire, theft and some weather damage. This includes specialized forms of insurance such as fire insurance, flood insurance, earthquake insurance, home insurance, or ...

as we know it today can be traced to the Great Fire of London, which in 1666 devoured more than 13,000 houses. The devastating effects of the fire converted the development of insurance "from a matter of convenience into one of urgency, a change of opinion reflected in Sir Christopher Wren's inclusion of a site for 'the Insurance Office' in his new plan for London in 1667". A number of attempted fire insurance schemes came to nothing, but in 1681, economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this field there are ...

Nicholas Barbon

Nicholas Barbon ( 1640 – 1698) was an English economist, physician, and financial speculator. Historians of mercantilism consider him to be one of the first proponents of the free market.

In the aftermath of the Great Fire of London, he be ...

and eleven associates established the first fire insurance company, the "Insurance Office for Houses", at the back of the Royal Exchange to insure brick and frame homes. Initially, 5,000 homes were insured by his Insurance Office.

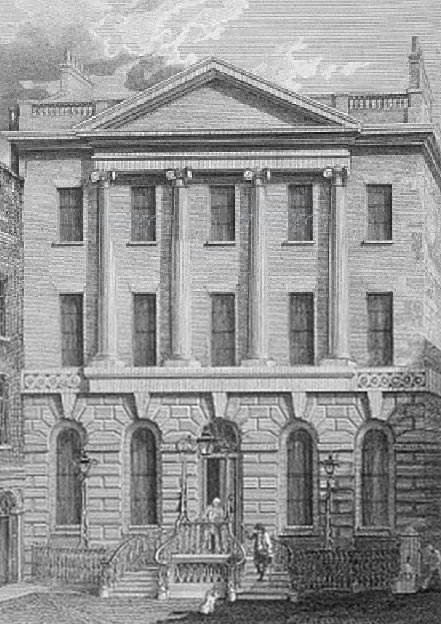

In the wake of this first successful venture, many similar companies were founded in the following decades. Initially, each company employed its own fire department to prevent and minimize the damage from conflagrations on properties insured by them. They also began to issue ' Fire insurance marks' to their customers. These would be displayed prominently above the main door of the property and allowed the insurance company to positively identify properties that had taken out insurance with them. One such notable company was the

In the wake of this first successful venture, many similar companies were founded in the following decades. Initially, each company employed its own fire department to prevent and minimize the damage from conflagrations on properties insured by them. They also began to issue ' Fire insurance marks' to their customers. These would be displayed prominently above the main door of the property and allowed the insurance company to positively identify properties that had taken out insurance with them. One such notable company was the Hand in Hand Fire & Life Insurance Society

The Hand in Hand Fire & Life Insurance Society was one of the oldest British insurance companies.

History

The company was founded in 1696 at Tom's Coffee House in St Martin's Lane in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in ...

, founded in 1696 at Tom's Coffee House in St Martin's Lane in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. It was structured as a mutual society

A mutual organization, or mutual society is an organization (which is often, but not always, a company or business) based on the principle of mutuality and governed by private law. Unlike a true cooperative, members usually do not contribute to ...

, and for 135 years it operated its own fire brigade and played an important part in shaping fire fighting and prevention. The Sun Fire Office is the earliest still existing property insurance company, dating from 1710.

This system was soon exposed as terribly flawed, as rival brigades often ignored burning buildings once they discovered that it had no insurance policy with their company. Eventually, a solution was agreed upon in which all the insurance companies would supply money and equipment to a municipal authority A municipal authority is a form of special-purpose governmental unit in Pennsylvania. The municipal authority is an alternate vehicle for accomplishing public purposes without the direct action of counties, municipalities and school districts. Thes ...

charged with stationing fire prevention assets and firefighters equally around the city to respond to all fires. This did not solve the problem entirely, as the brigades still tended to favor saving insured buildings to those without any insurance at all.

In Colonial America, the first insurance company that underwrote fire insurance was formed in Charles Town (modern-day Charleston), South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

in 1732. Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

helped to popularize and make standard the practice of insurance, particularly Property insurance

Property insurance provides protection against most risks to property, such as fire, theft and some weather damage. This includes specialized forms of insurance such as fire insurance, flood insurance, earthquake insurance, home insurance, or ...

to spread the risk of loss from fire, in the form of perpetual insurance. In 1752, he founded the Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss by Fire

The Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss by Fire is the oldest property insurance company in the United States. It was organized by Benjamin Franklin in 1752, and incorporated in 1768.

The Contributionship's build ...

. Franklin's company made contributions toward fire prevention. Not only did his company warn against certain fire hazards, but it also refused to insure certain buildings where the risk of fire was too great, such as all wooden houses.

Business insurance

At the same time, the first insurance schemes for the

At the same time, the first insurance schemes for the underwriting

Underwriting (UW) services are provided by some large financial institutions, such as banks, insurance companies and investment houses, whereby they guarantee payment in case of damage or financial loss and accept the financial risk for liabili ...

of business venture

Venture capital (often abbreviated as VC) is a form of private equity financing that is provided by venture capital firms or funds to startups, early-stage, and emerging companies that have been deemed to have high growth potential or which ha ...

s became available. By the end of the seventeenth century, London's growing importance as a center for trade was increasing demand for marine insurance

Marine insurance covers the physical loss or damage of ships, cargo, terminals, and any transport by which the property is transferred, acquired, or held between the points of origin and the final destination. Cargo insurance is the sub-branch o ...

.

In the late 1680s, Edward Lloyd opened a coffee house on Tower Street in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. This was during a boom of several hundred coffee house gathering places in London, many catering to certain social groupings of clientele. Lloyd's clientele tended to be ship owners, merchants, and ships' captains. This enabled Lloyd's Coffee House to become a reliable source of the latest shipping news. Such news included information about the sinking of ships and other ship/cargo losses. Because of this, Lloyd's became the meeting place for parties in the shipping industry to do business for having their cargoes and ships insured, with those willing to underwrite such ventures. These informal beginnings led to the establishment of the insurance market Lloyd's of London

Lloyd's of London, generally known simply as Lloyd's, is an insurance and reinsurance market located in London, England. Unlike most of its competitors in the industry, it is not an insurance company; rather, Lloyd's is a corporate body gove ...

and several related shipping and insurance businesses. In 1774, long after Edward Lloyd's death in 1713, the participating members of the insurance arrangement formed a committee and moved to the Royal Exchange on Cornhill as the Society of Lloyd's. Since its inception, Lloyd's has operated not as an insurance company but as a gathering place of individuals (and more recently, small groups of individuals) issuing insurance policies.

In 1720 the Royal Exchange Assurance Corporation

The Royal Exchange Assurance, founded in 1720, was a British insurance company. It took its name from the location of its offices at the Royal Exchange, London.

Origins

The Royal Exchange Assurance emerged from a joint stock insurance enterpr ...

received its royal charter under the Royal Exchange and London Assurance Corporation Act of 1719. The Act established this corporation as Great Britain's exclusive corporate insurer of marine property but allowed individuals in and outside of the Lloyd's consortium to underwrite insurance if unincorporated. From 1741 to 1750 the corporation was headed by multinational merchant, attorney, and author Nicholas Magens

Esq. Nicholas Magens or Nicolaus Paul Magens (1697 or 1704–1764) was an attorney, a merchant on Spain and her colonies in America, and an expert on ship insurance, general average and bottomry who gained a great reputation in commercial mat ...

.

Once established, insurance underwriters such as those at Lloyd's gradually over many decades moved into other lines of insurance business. In this same very gradual manner, most fire insurers have expanded their scope of business to insure against other causes of loss to buildings and their contents. Many have also filled a need for insuring business and personal liabilities, such as injuries caused by defective products and premises. This fuller range of insurance lines has become today's worldwide modern market of property-liability insurance.

Life insurance

The first life insurance policies were taken out in the early 18th century. The first company to offer life insurance was theAmicable Society for a Perpetual Assurance Office

Amicable Society for a Perpetual Assurance Office (a.k.a. "Amicable Society") is considered the first life insurance company in the world.Anzovin, p. 121 ''The first life insurance company known of record was founded in 1706 by the Bishop of Oxfo ...

, founded in London in 1706 by William Talbot and Sir Thomas Allen. The first plan of life insurance was that each member paid a fixed annual payment per share on from one to three shares with consideration to age of the members being twelve to fifty-five. At the end of the year a portion of the "amicable contribution" was divided among the wives and children of deceased members and it was in proportion to the amount of shares the heirs owned. Amicable Society started with 2000 members.

The first

The first life table

In actuarial science and demography, a life table (also called a mortality table or actuarial table) is a table which shows, for each age, what the probability is that a person of that age will die before their next birthday ("probability of death ...

was written by Edmund Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, Hal ...

in 1693, but it was only in the 1750s that the necessary mathematical and statistical tools were in place for the development of modern life insurance. James Dodson, a mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

and actuary, tried to establish a new company that issued premiums aimed at correctly offsetting the risks of long term life assurance policies, after being refused admission to the Amicable Life Assurance Society because of his advanced age. He was unsuccessful in his attempts at procuring a charter from the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is ...

before his death in 1757.

His disciple, Edward Rowe Mores was finally able to establish the Society for Equitable Assurances on Lives and Survivorship in 1762. It was the world's first mutual insurer and it pioneered age based premiums based on mortality rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of d ...

laying "the framework for scientific insurance practice and development" and "the basis of modern life assurance upon which all life assurance schemes were subsequently based".

Mores also specified that the chief official should be called an actuary—the earliest known reference to the position as a business concern. The first modern actuary was William Morgan, who was appointed in 1775 and served until 1830. In 1776 the Society carried out the first actuarial valuation of liabilities and subsequently distributed the first reversionary bonus (1781) and interim bonus (1809) among its members. It also used regular valuations to balance competing interests. The Society sought to treat its members equitably and the Directors tried to ensure that the policyholders received a fair return on their respective investments. Premiums were regulated according to age, and anybody could be admitted regardless of their state of health and other circumstances.

The sale of life insurance in the U.S. began in the late 1760s. The Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

Synods in Philadelphia and New York founded the Corporation for Relief of Poor and Distressed Widows and Children of Presbyterian Ministers in 1759; Episcopalian priests created a comparable relief fund in 1769. Between 1787 and 1837 more than two dozen life insurance companies were started, but fewer than half a dozen survived.

Accident insurance

In the late 19th century, "accident insurance" began to become available. This operated much like modern ''disability'' insurance. The first company to offer accident insurance was the Railway Passengers Assurance Company, formed in 1848 in England to insure against the rising number of fatalities on the nascent

In the late 19th century, "accident insurance" began to become available. This operated much like modern ''disability'' insurance. The first company to offer accident insurance was the Railway Passengers Assurance Company, formed in 1848 in England to insure against the rising number of fatalities on the nascent railway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

system. It was registered as the Universal Casualty Compensation Company to:

:...grant assurances on the lives of persons traveling by railway and to grant, in cases, of an accident not having a fatal termination, compensation to the assured for injuries received under certain conditions.

The company was able to reach an agreement with the railway companies

This is an incomplete list of the world's railway operating companies listed alphabetically by continent and country. This list includes companies operating both now and in the past.

In some countries, the railway operating bodies are not compani ...

, whereby basic accident insurance would be sold as a package deal along with travel ticket

Ticket or tickets may refer to:

Slips of paper

* Lottery ticket

* Parking ticket, a ticket confirming that the parking fee was paid (and the time of the parking start)

* Toll ticket, a slip of paper used to indicate where vehicles entered a tol ...

s to customers. The company charged higher premiums for second and third class travel due to the higher risk of injury in the roofless carriages.

National insurance

By the late 19th century, governments began to initiate national insurance programs against sickness and old age.Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

built on a tradition of welfare programs in Prussia and Saxony that began as early as in the 1840s. In the 1880s Chancellor Otto von Bismarck introduced old age pensions, accident insurance and medical care that formed the basis for Germany's welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

. His paternalistic programs won the support of German industry because its goals were to win the support of the working classes for the Empire and reduce the outflow of immigrants to America, where wages were higher but welfare did not exist.

In Britain more extensive legislation was introduced by the

In Britain more extensive legislation was introduced by the Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

government, led by H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

and David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

. The 1911 National Insurance Act gave the British working classes the first contributory system of insurance against illness and unemployment.

All workers who earned under £160 a year had to pay 4 pence a week to the scheme; the employer paid 3 pence, and general taxation paid 2 pence. As a result, workers could take sick leave and be paid 10 shillings a week for the first 13 weeks and 5 shillings a week for the next 13 weeks. Workers also gained access to free treatment for tuberculosis, and the sick were eligible for treatment by a panel doctor. The National Insurance Act also provided maternity benefits. Time-limited unemployment benefit was based on actuarial principles and it was planned that it would be funded by a fixed amount each from workers, employers, and taxpayers. It was restricted to particular industries, cyclical/seasonal industries like construction of ships, and neither made any provision for dependants. By 1913, 2.3 million were insured under the scheme for unemployment benefit and almost 15 million insured for sickness benefit.

This system was greatly expanded after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

under the influence of the Beveridge Report

The Beveridge Report, officially entitled ''Social Insurance and Allied Services'' (Command paper, Cmd. 6404), is a government report, published in November 1942, influential in the founding of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. It was draft ...

, to form the first modern welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

.

In the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, until the passage of the Social Security Act in 1935, the federal government did not mandate any form of insurance upon the nation as a whole. With the passage of the Act, the new program expanded the concept and acceptance of insurance as a means to achieve the individual financial security that might not otherwise be available. That expansion experienced its first boom market immediately after the Second World War with the original VA Home Loan programs that greatly expanded the idea that affordable housing for veterans was a benefit of having served. The mortgages that were underwritten by the federal government during this time included an insurance clause as a means of protecting the banks and lending institutions involved against avoidable losses. During the 1940s there was also the GI life insurance policy program that was designed to ease the burden of military losses on the civilian population and survivors.

Notes

References

;Primary sources * ;Secondary sources * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of InsuranceInsurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...