History Of Geology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of geology is concerned with the development of the natural science of geology.

Some of the first geological thoughts were about the origin of Earth.

Some of the first geological thoughts were about the origin of Earth.

It was not until the 17th century that geology made great strides in its development. At this time, geology became its own entity in the world of natural science. It was discovered by the Christian world that different translations of the

It was not until the 17th century that geology made great strides in its development. At this time, geology became its own entity in the world of natural science. It was discovered by the Christian world that different translations of the

From this increased interest in the nature of the earth and its origin, came a heightened attention to

From this increased interest in the nature of the earth and its origin, came a heightened attention to

In early nineteenth-century Britain,

In early nineteenth-century Britain,

In 1912 Alfred Wegener proposed the theory of

In 1912 Alfred Wegener proposed the theory of

Geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other Astronomical object, astronomical objects, the features or rock (geology), rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology ...

is the scientific study of the origin, history, and structure of Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's sur ...

.

Antiquity

Some of the first geological thoughts were about the origin of Earth.

Some of the first geological thoughts were about the origin of Earth. Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

developed some primary geological concepts concerning the origin of the earth. Additionally, in the 4th century BC Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

made critical observations of the slow rate of geological change. He observed the composition of the land and formulated a theory where the earth changes at a slow rate and that these changes cannot be observed during one person's lifetime. Aristotle developed one of the first evidence-based concepts connected to the geological realm regarding the rate at which the earth physically changes.

However, it was his successor at the Lyceum, the philosopher Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

, who made the greatest progress in antiquity in his work ''On Stones''. He described many minerals

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed ...

and ores

Ore is natural rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically containing metals, that can be mined, treated and sold at a profit.Encyclopædia Britannica. "Ore". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 7 April ...

both from local mines such as those at Laurium near Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

, and further afield. He also quite naturally discussed types of marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite. Marble is typically not foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the term ''marble'' refers to metamorphose ...

and building materials like limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

s, and attempted a primitive classification of the properties of minerals by their properties such as hardness

In materials science, hardness (antonym: softness) is a measure of the resistance to localized plastic deformation induced by either mechanical indentation or abrasion. In general, different materials differ in their hardness; for example hard ...

.

Much later in the Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

period, Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

produced a very extensive discussion of many more minerals and metal

A metal (from ancient Greek, Greek μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electrical resistivity and conductivity, e ...

s then widely used for practical ends. He was among the first to correctly identify the origin of amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In M ...

as a fossilized resin

In polymer chemistry and materials science, resin is a solid or highly viscous substance of plant or synthetic origin that is typically convertible into polymers. Resins are usually mixtures of organic compounds. This article focuses on nat ...

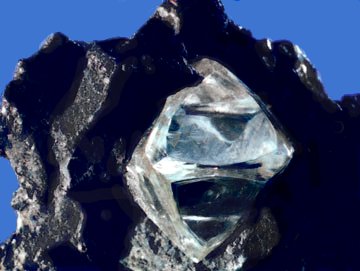

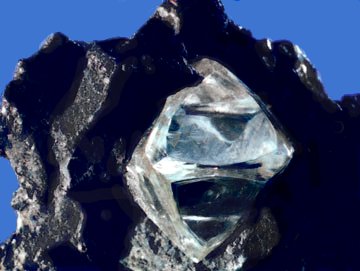

from trees by the observation of insects trapped within some pieces. He also laid the basis of crystallography

Crystallography is the experimental science of determining the arrangement of atoms in crystalline solids. Crystallography is a fundamental subject in the fields of materials science and solid-state physics ( condensed matter physics). The wor ...

by recognising the octahedral habit of diamond

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the chemically stable form of carbon at room temperature and pressure, b ...

.

Middle Ages

Abu al-Rayhan al-Biruni (AD 973–1048) was one of the earliest Muslim geologists, whose works included the earliest writings on thegeology of India

The geology of India is diverse. Different regions of India contain rocks belonging to different geologic periods, dating as far back as the Eoarchean Era. Some of the rocks are very deformed and altered. Other deposits include recently d ...

, hypothesizing that the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, In ...

was once a sea

The sea, connected as the world ocean or simply the ocean, is the body of salty water that covers approximately 71% of the Earth's surface. The word sea is also used to denote second-order sections of the sea, such as the Mediterranean Sea, ...

.

Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islami ...

(Avicenna, AD 981–1037), a Persian polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

, made significant contributions to geology and the natural science

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

s (which he called ''Attabieyat'') along with other natural philosophers such as Ikhwan AI-Safa and many others. Ibn Sina wrote an encyclopedic work entitled "'' Kitab al-Shifa''" (the Book of Cure, Healing or Remedy from ignorance), in which Part 2, Section 5, contains his commentary on Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

's Mineralogy and Meteorology, in six chapters: Formation of mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher ...

s, The advantages of mountains in the formation of clouds; Sources of water; Origin of earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

s; Formation of mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

s; The diversity of the earth's terrain

Terrain or relief (also topographical relief) involves the vertical and horizontal dimensions of land surface. The term bathymetry is used to describe underwater relief, while hypsometry studies terrain relative to sea level. The Latin word ...

.

In medieval China, one of the most intriguing naturalists was Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen wa ...

(1031–1095), a polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

personality who dabbled in many fields of study in his age. In terms of geology, Shen Kuo is one of the first naturalists to have formulated a theory of geomorphology

Geomorphology (from Ancient Greek: , ', "earth"; , ', "form"; and , ', "study") is the scientific study of the origin and evolution of topographic and bathymetric features created by physical, chemical or biological processes operating at or ...

. This was based on his observations of sedimentary

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles ...

uplift, soil erosion

Soil erosion is the denudation or wearing away of the upper layer of soil. It is a form of soil degradation. This natural process is caused by the dynamic activity of erosive agents, that is, water, ice (glaciers), snow, air (wind), plants, a ...

, deposition of silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel ...

, and marine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military ...

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s found in the Taihang Mountains

The Taihang Mountains () are a Chinese mountain range running down the eastern edge of the Loess Plateau in Shanxi, Henan and Hebei provinces. The range extends over from north to south and has an average elevation of . The principal peak is ...

, located hundreds of miles from the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the conti ...

. He also formulated a theory of gradual climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

, after his observation of ancient petrified

In geology, petrifaction or petrification () is the process by which organic material becomes a fossil through the replacement of the original material and the filling of the original pore spaces with minerals. Petrified wood typifies this p ...

bamboo

Bamboos are a diverse group of evergreen perennial flowering plants making up the subfamily Bambusoideae of the grass family Poaceae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family. The origin of the word "bamboo" is uncertain, ...

s found in a preserved state underground near Yanzhou (modern Yan'an

Yan'an (; ), alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several counties, including Zhidan (formerly Bao'an) ...

), in the dry northern climate of Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

province. He formulated a hypothesis for the process of land formation: based on his observation of fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

shells in a geological stratum

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as e ...

in a mountain hundreds of miles from the ocean, he inferred that the land was formed by erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is d ...

of the mountains and by deposition

Deposition may refer to:

* Deposition (law), taking testimony outside of court

* Deposition (politics), the removal of a person of authority from political power

* Deposition (university), a widespread initiation ritual for new students practiced f ...

of silt.

17th century

It was not until the 17th century that geology made great strides in its development. At this time, geology became its own entity in the world of natural science. It was discovered by the Christian world that different translations of the

It was not until the 17th century that geology made great strides in its development. At this time, geology became its own entity in the world of natural science. It was discovered by the Christian world that different translations of the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus ...

contained different versions of the biblical text. The one entity that remained consistent through all of the interpretations was that the Deluge had formed the world's geology and geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

. To prove the Bible's authenticity, individuals felt the need to demonstrate with scientific evidence that the Great Flood had in fact occurred. With this enhanced desire for data came an increase in observations of the earth's composition, which in turn led to the discovery of fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s. Although theories that resulted from the heightened interest in the earth's composition were often manipulated to support the concept of the Deluge, a genuine outcome was a greater interest in the makeup of the earth. Due to the strength of Christian beliefs during the 17th century, the theory of the origin of the Earth that was most widely accepted was '' A New Theory of the Earth'' published in 1696, by William Whiston. Whiston used Christian reasoning to "prove" that the Great Flood had occurred and that the flood had formed the rock strata of the earth.

During the 17th century, both religious and scientific speculation about Earth's origin further propelled interest in the earth and brought about more systematic identification techniques of the earth's strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as e ...

. The earth's strata can be defined as horizontal layers of rock having approximately the same composition throughout. An important pioneer in the science was Nicolas Steno

Niels Steensen ( da, Niels Steensen; Latinized to ''Nicolaus Steno'' or ''Nicolaus Stenonius''; 1 January 1638 – 25 November 1686stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers ( strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

and geology (Steno, who became a Catholic as an adult, was eventually made a bishop, and was beatified in 1988 by Pope John Paul II. Therefore, he is also called Blessed Nicolas Steno).

18th century

From this increased interest in the nature of the earth and its origin, came a heightened attention to

From this increased interest in the nature of the earth and its origin, came a heightened attention to mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

s and other components of the earth's crust. Moreover, the increasing economic importance of mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the econom ...

in Europe during the mid to late 18th century made the possession of accurate knowledge about ores and their natural distribution vital. Scholars began to study the makeup of the earth in a systematic manner, with detailed comparisons and descriptions not only of the land itself, but of the semi-precious metal

A metal (from ancient Greek, Greek μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electrical resistivity and conductivity, e ...

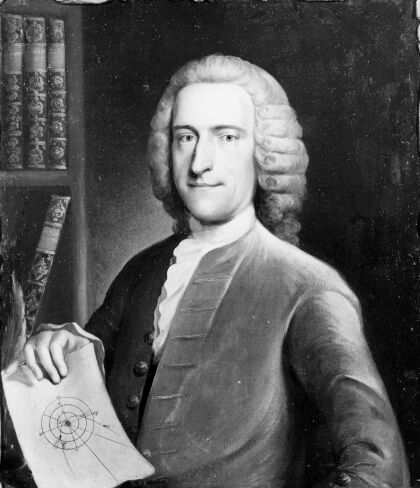

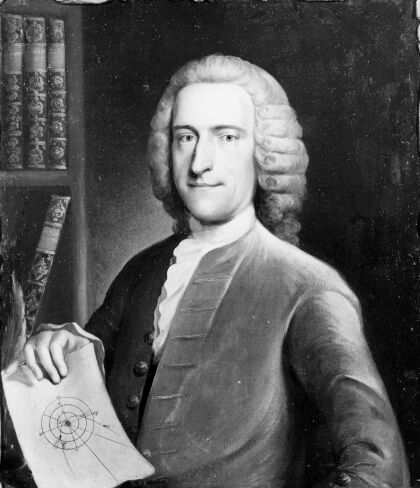

s it contained, which had great commercial value. For example, in 1774 Abraham Gottlob Werner

Abraham Gottlob Werner (; 25 September 174930 June 1817) was a German geologist who set out an early theory about the stratification of the Earth's crust and propounded a history of the Earth that came to be known as Neptunism. While most tene ...

published the book ''Von den äusserlichen Kennzeichen der Fossilien (On the External Characters of Minerals),'' which brought him widespread recognition because he presented a detailed system for identifying specific minerals based on external characteristics. The more efficiently productive land for mining could be identified and the semi-precious metals could be found, the more money could be made. This drive for economic gain propelled geology into the limelight and made it a popular subject to pursue. With an increased number of people studying it, came more detailed observations and more information about the earth.

Also during the eighteenth century, aspects of the history of the earthnamely the divergences between the accepted religious concept and factual evidenceonce again became a popular topic for discussion in society. In 1749, the French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopédiste.

His works influenced the next two generations of naturalists, including two prominent ...

published his ''Histoire Naturelle,'' in which he attacked the popular Biblical accounts given by Whiston and other ecclesiastical theorists of the history of the earth. From experimentation with cooling globes, he found that the age of the earth was not only 4,000 or 5,500 years as inferred from the Bible, but rather 75,000 years. Another individual who described the history of the earth with reference to neither God nor the Bible was the philosopher Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

, who published his '' Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens (Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels)'' in 1755. From the works of these respected men, as well as others, it became acceptable by the mid eighteenth century to question the age of the earth. This questioning represented a turning point in the study of the earth. It was now possible to study the history of the earth from a scientific perspective without religious preconceptions.

With the application of scientific methods to the investigation of the earth's history, the study of geology could become a distinct field of science. To begin with, the terminology and definition of what constituted geological study had to be worked out. The term "geology" was first used technically in publications by two Genevan naturalists, Jean-André Deluc and Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, though "geology" was not well received as a term until it was taken up in the very influential compendium, the ''Encyclopédie

''Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers'' (English: ''Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts''), better known as ''Encyclopédie'', was a general encyclopedia publis ...

'', published beginning in 1751 by Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the '' Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promi ...

. Once the term was established to denote the study of the earth and its history, geology slowly became more generally recognized as a distinct science that could be taught as a field of study at educational institutions. In 1741 the best-known institution in the field of natural history, the National Museum of Natural History in France, created the first teaching position designated specifically for geology. This was an important step in further promoting knowledge of geology as a science and in recognizing the value of widely disseminating such knowledge.

By the 1770s, chemistry was starting to play a pivotal role in the theoretical foundation of geology and two opposite theories with committed followers emerged. These contrasting theories offered differing explanations of how the rock layers of the earth's surface had formed. One suggested that a liquid inundation, perhaps like the biblical deluge, had created all geological strata. The theory extended chemical theories that had been developing since the seventeenth century and was promoted by Scotland's John Walker, Sweden's Johan Gottschalk Wallerius and Germany's Abraham Werner

Abraham Gottlob Werner (; 25 September 174930 June 1817) was a German geologist who set out an early theory about the stratification of the Earth's crust and propounded a history of the Earth that came to be known as Neptunism. While most tene ...

. Of these names, Werner's views become internationally influential around 1800. He argued that the earth's layers, including basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90 ...

and granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

, had formed as a precipitate from an ocean that covered the entire earth. Werner's system was influential and those who accepted his theory were known as Diluvianists or Neptunists. The Neptunist thesis was the most popular during the late eighteenth century, especially for those who were chemically trained. However, another thesis slowly gained currency from the 1780s forward. Instead of water, some mid eighteenth-century naturalists such as Buffon had suggested that strata had been formed through heat (or fire). The thesis was modified and expanded by the Scottish naturalist James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June O.S.172614 June 1726 New Style. – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, agriculturalist, chemical manufacturer, naturalist and physician. Often referred to as the father of modern geology, he played a key role ...

during the 1780s. He argued against the theory of Neptunism, proposing instead the theory of based on heat. Those who followed this thesis during the early nineteenth century referred to this view as Plutonism

Plutonism is the geologic theory that the igneous rocks forming the Earth originated from intrusive magmatic activity, with a continuing gradual process of weathering and erosion wearing away rocks, which were then deposited on the sea bed, re-f ...

: the formation of the earth through the gradual solidification of a molten mass at a slow rate by the same processes that had occurred throughout history and continued in the present day. This led him to the conclusion that the earth was immeasurably old and could not possibly be explained within the limits of the chronology inferred from the Bible. Plutonists believed that volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plat ...

processes were the chief agent in rock formation, not water from a Great Flood.

19th century

In the early 19th century, the mining industry andIndustrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

stimulated the rapid development of the stratigraphic column – "the sequence of rock formations arranged according to their order of formation in time." In England, the mining surveyor William Smith, starting in the 1790s, found empirically that fossils were a highly effective means of distinguishing between otherwise similar formations of the landscape as he travelled the country working on the canal system and produced the first geological map of Britain. At about the same time, the French comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in na ...

assisted by his colleague Alexandre Brogniart at the École des Mines de Paris

Mines Paris - PSL, officially École nationale supérieure des mines de Paris (until May 2022 Mines ParisTech, also known as École des mines de Paris, ENSMP, Mines de Paris, les Mines, or Paris School of Mines), is a French grande école and a ...

realized that the relative ages of fossils could be determined from a geological standpoint; in terms of what layer of rock the fossils are located and the distance these layers of rock are from the surface of the earth. Through the synthesis of their findings, Brogniart and Cuvier realized that different strata could be identified by fossil contents and thus each stratum could be assigned to a unique position in a sequence. After the publication of Cuvier and Brongniart's book, "Description Geologiques des Environs de Paris" in 1811, which outlined the concept, stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers ( strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

became very popular amongst geologists; many hoped to apply this concept to all the rocks of the earth. During this century various geologists further refined and completed the stratigraphic column. For instance, in 1833 while Adam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick (; 22 March 1785 – 27 January 1873) was a British geologist and Anglican priest, one of the founders of modern geology. He proposed the Cambrian and Devonian period of the geological timescale. Based on work which he did on ...

was mapping rocks that he had established were from the Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million years ago ...

Period, Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

was elsewhere suggesting a subdivision of the Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

Period; whilst Roderick Murchison

Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1st Baronet, (19 February 1792 – 22 October 1871) was a Scottish geologist who served as director-general of the British Geological Survey from 1855 until his death in 1871. He is noted for investigating and ...

, mapping into Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

from a different direction, was assigning the upper parts of Sedgwick's ''Cambrian'' to the lower parts of his own Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 24.6 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the shortest period of the Paleoz ...

Period. The stratigraphic column was significant because it supplied a method to assign a relative age of these rocks by slotting them into different positions in their stratigraphical sequence. This created a global approach to dating the age of the earth and allowed for further correlations to be drawn from similarities found in the makeup of the earth's crust in various countries.

In early nineteenth-century Britain,

In early nineteenth-century Britain, catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism theorises that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow incremen ...

was adapted with the aim of reconciling geological science with religious traditions of the biblical Great Flood

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primaeval ...

. In the early 1820s English geologists including William Buckland

William Buckland DD, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named ' ...

and Adam Sedgwick interpreted "diluvial" deposits as the outcome of Noah's flood, but by the end of the decade they revised their opinions in favour of local inundations. Charles Lyell challenged catastrophism with the publication in 1830 of the first volume of his book ''Principles of Geology'' which presented a variety of geological evidence from England, France, Italy and Spain to prove Hutton's ideas of gradualism correct. He argued that most geological change had been very gradual in human history. Lyell provided evidence for Uniformitarianism, a geological doctrine holding that processes occur at the same rates in the present as they did in the past and account for all of the earth's geological features. Lyell's works were popular and widely read, and the concept of Uniformitarianism took a strong hold in geological society.

In 1831 Captain Robert FitzRoy, given charge of the coastal survey expedition of HMS ''Beagle'', sought a suitable naturalist to examine the land and give geological advice. This fell to Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, who had just completed his BA degree and had accompanied Sedgwick on a two-week Welsh mapping expedition after taking his Spring course on geology. Fitzroy gave Darwin Lyell's ''Principles of Geology'', and Darwin became and advocate of Lyell ideas, inventively theorising on uniformitarian principles about the geological processes he saw, and even challenging some of Lyell's ideas. He speculated about the earth expanding to explain uplift, then on the basis of the idea that ocean areas sank as land was uplifted, theorised that coral atoll

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secr ...

s grew from fringing coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of Colony (biology), colonies of coral polyp (zoology), polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, wh ...

s round sinking volcanic islands. This idea was confirmed when the ''Beagle'' surveyed the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and in 1842 he published his theory on ''The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs

''The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs, Being the first part of the geology of the voyage of the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. during the years 1832 to 1836'', was published in 1842 as Charles Darwin's first monogr ...

''. Darwin's discovery of giant fossils helped to establish his reputation as a geologist, and his theorising about the causes of their extinction led to his theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

by natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

published in ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' in 1859.

Economic motivations for the practical use of geological data motivated some governments to support geological research. During the 19th century several countries, including Canada, Australia, Great Britain and the United States, initiated geological surveying that would produce geological maps of vast areas of the countries. Geological mapping provides the location of useful rocks and minerals and such information could be used to benefit the country's mining and quarrying industries. With the government and industrial funding of geological research, more individuals undertook study of geology as technology and techniques improved, leading to the expansion of the field of the science.

In the 19th century, geological inquiry had estimated the age of the earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion, or core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating is based on evidence from radiometric age-dating of ...

in terms of millions of years. In 1862, the physicist William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, (26 June 182417 December 1907) was a British mathematician, Mathematical physics, mathematical physicist and engineer born in Belfast. Professor of Natural Philosophy (Glasgow), Professor of Natural Philoso ...

, published calculations that fixed the age of earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion, or core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating is based on evidence from radiometric age-dating of ...

at between 20 million and 400 million years. He assumed that earth had formed as a completely molten object, and determined the amount of time it would take for the near-surface to cool to its present temperature. Many geologists contended that Thomson's estimates were inadequate to account for observed thicknesses of sedimentary rock, evolution of life, and the formation of the crystalline basement rocks beneath the sedimentary cover. The discovery of radioactivity in the early Twentieth Century provided an additional source of heat within the earth, allowing for an increase in Thomson's calculated age, as well as a means of dating geological events.

20th century

By the early 20th Century radiogenic isotopes had been discovered andRadiometric Dating

Radiometric dating, radioactive dating or radioisotope dating is a technique which is used to date materials such as rocks or carbon, in which trace radioactive impurities were selectively incorporated when they were formed. The method compares ...

had been developed. In 1911 Arthur Holmes

Arthur Holmes (14 January 1890 – 20 September 1965) was an English geologist who made two major contributions to the understanding of geology. He pioneered the use of radiometric dating of minerals, and was the first earth scientist to grasp ...

, among the pioneers in the use of radioactive decay as a mean to measure geological time, dated a sample from Ceylon at 1.6 billion years old using lead isotopes. In 1913 Holmes was on the staff of Imperial College

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

, when he published his famous book ''The Age of the Earth'' in which he argued strongly in favour of the use of radioactive dating methods rather than methods based on geological sedimentation or cooling of the earth (many people still clung to Lord Kelvin's calculations of less than 100 million years). Holmes estimated the oldest Archean rocks to be 1,600 million years, but did not speculate about the earth's age. His promotion of the theory over the next decades earned him the nickname of Father of Modern Geochronology

Geochronology is the science of determining the age of rocks, fossils, and sediments using signatures inherent in the rocks themselves. Absolute geochronology can be accomplished through radioactive isotopes, whereas relative geochronology is ...

. In 1921, attendees at the yearly meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chi ...

came to a rough consensus that the age of the earth was a few billion years old, and that radiometric dating was credible. Holmes published The Age of the Earth, an Introduction to Geological Ideas in 1927 in which he presented a range of 1.6 to 3.0 billion years. and in the 1940s to 4,500±100 million years, based on measurements of the relative abundance of uranium isotopes established by Alfred O. C. Nier. Theories that did not comply with the scientific evidence that established the age of the earth could no longer be accepted. The established age of the earth has been refined since then but has not significantly changed.

In 1912 Alfred Wegener proposed the theory of

In 1912 Alfred Wegener proposed the theory of continental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pl ...

. This theory suggests that the shapes of continents and matching coastline geology between some continents indicates they were joined together in the past and formed a single landmass known as Pangaea; thereafter they separated and drifted like rafts over the ocean floor, currently reaching their present position. Additionally, the theory of continental drift offered a possible explanation as to the formation of mountains; plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label= Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of larg ...

built on the theory of continental drift.

Unfortunately, Wegener provided no convincing mechanism for this drift, and his ideas were not generally accepted during his lifetime. Arthur Holmes accepted Wegener's theory and provided a mechanism: mantle convection

Mantle convection is the very slow creeping motion of Earth's solid silicate mantle as convection currents carrying heat from the interior to the planet's surface.

The Earth's surface lithosphere rides atop the asthenosphere and the two form ...

, to cause the continents to move. However, it was not until after the Second World War that new evidence started to accumulate that supported continental drift. There followed a period of 20 extremely exciting years where the theory of continental drift developed from being believed by a few to being the cornerstone of modern geology. Beginning in 1947 research provided new evidence about the ocean floor, and in 1960 Bruce C. Heezen

Bruce Charles Heezen (; April 11, 1924 – June 21, 1977) was an American geologist. He worked with oceanographic cartographer Marie Tharp at Columbia University to map the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the 1950s.

Biography

Heezen was born in Vinton, I ...

published the concept of mid-ocean ridges. Soon after this, Robert S. Dietz

Robert Sinclair Dietz (September 14, 1914 – May 19, 1995) was a scientist with the US Coast and Geodetic Survey. Dietz, born in Westfield, New Jersey, was a marine geologist, geophysicist and oceanographer who conducted pioneering research along ...

and Harry H. Hess proposed that the oceanic crust forms as the seafloor spreads apart along mid-ocean ridges in seafloor spreading. This was seen as confirmation of mantle convection

Mantle convection is the very slow creeping motion of Earth's solid silicate mantle as convection currents carrying heat from the interior to the planet's surface.

The Earth's surface lithosphere rides atop the asthenosphere and the two form ...

and so the major stumbling block to the theory was removed. Geophysical evidence suggested lateral motion of continents and that oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramafic ...

is younger than continental crust. This geophysical evidence also spurred the hypothesis of paleomagnetism

Paleomagnetism (or palaeomagnetismsee ), is the study of magnetic fields recorded in rocks, sediment, or archeological materials. Geophysicists who specialize in paleomagnetism are called ''paleomagnetists.''

Certain magnetic minerals in roc ...

, the record of the orientation of the earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magneti ...

recorded in magnetic minerals. British geophysicist S. K. Runcorn suggested the concept of paleomagnetism from his finding that the continents had moved relative to the earth's magnetic poles. Tuzo Wilson, who was a promoter of the sea floor spreading hypothesis and continental drift from the very beginning, added the concept of transform fault

A transform fault or transform boundary, is a fault along a plate boundary where the motion is predominantly horizontal. It ends abruptly where it connects to another plate boundary, either another transform, a spreading ridge, or a subduct ...

s to the model, completing the classes of fault types necessary to make the mobility of the plates on the globe function. A symposium on continental drift that was held at the Royal Society of London in 1965 must be regarded as the official start of the acceptance of plate tectonics by the scientific community. The abstracts from the symposium are issued as Blacket, Bullard, Runcorn; 1965. In this symposium, Edward Bullard

Sir Edward Crisp Bullard FRS (21 September 1907 – 3 April 1980) was a British geophysicist who is considered, along with Maurice Ewing, to have founded the discipline of marine geophysics. He developed the theory of the geodynamo, pioneered ...

and co-workers showed with a computer calculation how the continents along both sides of the Atlantic would best fit to close the ocean, which became known as the famous "Bullard's Fit". By the late 1960s the weight of the evidence available saw Continental Drift as the generally accepted theory.

Modern geology

By applying sound stratigraphic principles to the distribution of craters on theMoon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

, it can be argued that almost overnight, Gene Shoemaker

Eugene Merle Shoemaker (April 28, 1928 – July 18, 1997) was an American geologist. He co-discovered Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 with his wife Carolyn S. Shoemaker and David H. Levy. This comet hit Jupiter in July 1994: the impact was televis ...

took the study of the Moon away from Lunar astronomers and gave it to Lunar geologists.

In recent years, geology has continued its tradition as the study of the character and origin of the earth, its surface features and internal structure. What changed in the later 20th century is the perspective of geological study. Geology was now studied using a more integrative approach, considering the earth in a broader context encompassing the atmosphere, biosphere and hydrosphere."Studying Earth Sciences." British Geological Survey. 2006. Natural Environment

Research Council. http://www.bgs.ac.uk/vacancies/studying.htm , accessed 29 November 2006 Satellites located in space that take wide scope photographs of the earth provide such a perspective. In 1972, The Landsat

The Landsat program is the longest-running enterprise for acquisition of satellite imagery of Earth. It is a joint NASA / USGS program. On 23 July 1972, the Earth Resources Technology Satellite was launched. This was eventually renamed to La ...

Program, a series of satellite missions jointly managed by NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

and the U.S. Geological Survey, began supplying satellite images that can be geologically analyzed. These images can be used to map major geological units, recognize and correlate rock types for vast regions and track the movements of Plate Tectonics. A few applications of this data include the ability to produce geologically detailed maps, locate sources of natural energy and predict possible natural disasters caused by plate shifts.Rocchio, Laura. "The Landsat Program." National Aeronautics and Space

Administration. http://landsat.gsfc.nasa.gov , accessed 4 December 2006

See also

* History of geomagnetism * History of paleontology *Outline of Earth science

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Earth science:

Earth science – all-embracing term for the sciences related to the planet Earth. It is also known as geoscience, the geosciences or the Earthquake s ...

* Humboldtian science

Humboldtian science refers to a movement in science in the 19th century closely connected to the work and writings of German scientist, naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt. It maintained a certain ethics of precision and observation, ...

* Timeline of geology

* Timeline of the development of tectonophysics (before 1954)

References

Sources

* * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of GeologyGeology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other Astronomical object, astronomical objects, the features or rock (geology), rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology ...

Geology

Geologists

he:גאולוגיה#התפתחות המחקר הגאולוגי