History of education in Scotland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of education in Scotland in its modern sense of organised and institutional learning, began in the Middle Ages, when Church choir schools and

The history of education in Scotland in its modern sense of organised and institutional learning, began in the Middle Ages, when Church choir schools and

In the Early Middle Ages, Scotland was overwhelmingly an oral society and education was verbal rather than literary. Fuller sources for Ireland of the same period suggest that there may have been filidh, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge in Gaelic to the next generation.R. A. Houston, ''Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600-1800'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), , p. 76. After the "de-gallicisation" of the Scottish court from the twelfth century, a less highly regarded order of

In the Early Middle Ages, Scotland was overwhelmingly an oral society and education was verbal rather than literary. Fuller sources for Ireland of the same period suggest that there may have been filidh, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge in Gaelic to the next generation.R. A. Houston, ''Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600-1800'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), , p. 76. After the "de-gallicisation" of the Scottish court from the twelfth century, a less highly regarded order of

''Scotland's Books: A History of Scottish Literature''

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), . The establishment of Christianity brought Latin to Scotland as a scholarly and written language. Monasteries served as major repositories of knowledge and education, often running schools and providing a small educated elite, who were essential to create and read documents in a largely illiterate society.A. Macquarrie, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), , p. 128. In the High Middle Ages new sources of education arose, with Until the fifteenth century, those who wished to attend university had to travel to England or the continent, and just over a 1,000 have been identified as doing so between the twelfth century and 1410. Among these the most important intellectual figure was

Until the fifteenth century, those who wished to attend university had to travel to England or the continent, and just over a 1,000 have been identified as doing so between the twelfth century and 1410. Among these the most important intellectual figure was

The humanist concern with widening education was shared by the Protestant reformers, with a desire for a godly people replacing the aim of having educated citizens. In 1560, the '' First Book of Discipline'' set out a plan for a school in every parish, but this proved financially impossible. In the burghs the old schools were maintained, with the song schools and a number of new foundations becoming reformed grammar schools or ordinary parish schools. Schools were supported by a combination of kirk funds, contributions from local heritors or burgh councils and parents that could pay. They were inspected by kirk sessions, who checked for the quality of teaching and doctrinal purity. There were also large number of unregulated "adventure schools", which sometimes fulfilled a local needs and sometimes took pupils away from the official schools. Outside of the established burgh schools, masters often combined their position with other employment, particularly minor posts within the kirk, such as clerk. At their best, the curriculum included

The humanist concern with widening education was shared by the Protestant reformers, with a desire for a godly people replacing the aim of having educated citizens. In 1560, the '' First Book of Discipline'' set out a plan for a school in every parish, but this proved financially impossible. In the burghs the old schools were maintained, with the song schools and a number of new foundations becoming reformed grammar schools or ordinary parish schools. Schools were supported by a combination of kirk funds, contributions from local heritors or burgh councils and parents that could pay. They were inspected by kirk sessions, who checked for the quality of teaching and doctrinal purity. There were also large number of unregulated "adventure schools", which sometimes fulfilled a local needs and sometimes took pupils away from the official schools. Outside of the established burgh schools, masters often combined their position with other employment, particularly minor posts within the kirk, such as clerk. At their best, the curriculum included  After the Reformation, Scotland's universities underwent a series of reforms associated with Andrew Melville, who returned from Geneva to become principal of the University of Glasgow in 1574. A distinguished linguist, philosopher and poet, he had trained in Paris and studied law at

After the Reformation, Scotland's universities underwent a series of reforms associated with Andrew Melville, who returned from Geneva to become principal of the University of Glasgow in 1574. A distinguished linguist, philosopher and poet, he had trained in Paris and studied law at

One of the effects of this extensive network of schools was the growth of the "democratic myth" in the 19th century, which created the widespread belief that many a "lad of pairts" had been able to rise up through the system to take high office and that literacy was much more widespread in Scotland than in neighbouring states, particularly England. Historians now accept that very few boys were able to pursue this route to social advancement and that literacy was not noticeably higher than comparable nations, as the education in the parish schools was basic, short and attendance was not compulsory. However, Scotland did reap the intellectual benefits of a highly developed university system. A. Herman, ''

One of the effects of this extensive network of schools was the growth of the "democratic myth" in the 19th century, which created the widespread belief that many a "lad of pairts" had been able to rise up through the system to take high office and that literacy was much more widespread in Scotland than in neighbouring states, particularly England. Historians now accept that very few boys were able to pursue this route to social advancement and that literacy was not noticeably higher than comparable nations, as the education in the parish schools was basic, short and attendance was not compulsory. However, Scotland did reap the intellectual benefits of a highly developed university system. A. Herman, '' In the Scottish Highlands as well as problems of distance and physical isolation, most people spoke Gaelic which few teachers and ministers could understand. Here the Kirk's parish schools were supplemented by the

In the Scottish Highlands as well as problems of distance and physical isolation, most people spoke Gaelic which few teachers and ministers could understand. Here the Kirk's parish schools were supplemented by the  Access to Scottish universities was probably more open than in contemporary England, Germany or France. Attendance was less expensive and the student body more representative of society as a whole. Humbler students were aided by a system of bursaries established to aid in the training of the clergy. In this period residence became divorced from the colleges and students were able to live much more cheaply and largely unsupervised, at home, with friends or in lodgings in the university towns. The system was flexible and the curriculum became a modern philosophical and scientific one, in keeping with contemporary needs for improvement and progress. Scotland reaped the intellectual benefits of this system in its contribution to the

Access to Scottish universities was probably more open than in contemporary England, Germany or France. Attendance was less expensive and the student body more representative of society as a whole. Humbler students were aided by a system of bursaries established to aid in the training of the clergy. In this period residence became divorced from the colleges and students were able to live much more cheaply and largely unsupervised, at home, with friends or in lodgings in the university towns. The system was flexible and the curriculum became a modern philosophical and scientific one, in keeping with contemporary needs for improvement and progress. Scotland reaped the intellectual benefits of this system in its contribution to the

Industrialisation, urbanisation and the

Industrialisation, urbanisation and the

The Scottish education system underwent radical change and expansion in the 20th century. In 1918 Roman Catholic schools were brought into the system, but retained their distinct religious character, access to schools by priests and the requirement that school staff be acceptable to the Church. The school leaving age was raised to 14 in 1901, and although plans to raise it to 15 in the 1940s were never ratified, increasing numbers stayed on beyond elementary education and it was eventually raised to 16 in 1973. As a result, secondary education was the major area of growth in the inter-war period, particularly for girls, who stayed on in full-time education in increasing numbers throughout the century.C. Harvie, ''No Gods and Precious Few Heroes: Twentieth-Century Scotland'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 3rd edn., 1998), , p. 78. New qualifications were developed to cope with changing aspirations and economics, with the Leaving Certificate being replaced by the

The Scottish education system underwent radical change and expansion in the 20th century. In 1918 Roman Catholic schools were brought into the system, but retained their distinct religious character, access to schools by priests and the requirement that school staff be acceptable to the Church. The school leaving age was raised to 14 in 1901, and although plans to raise it to 15 in the 1940s were never ratified, increasing numbers stayed on beyond elementary education and it was eventually raised to 16 in 1973. As a result, secondary education was the major area of growth in the inter-war period, particularly for girls, who stayed on in full-time education in increasing numbers throughout the century.C. Harvie, ''No Gods and Precious Few Heroes: Twentieth-Century Scotland'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 3rd edn., 1998), , p. 78. New qualifications were developed to cope with changing aspirations and economics, with the Leaving Certificate being replaced by the  The first half of the 20th century saw Scottish universities fall behind those in England and Europe in terms of participation and investment. The decline of traditional industries between the wars undermined recruitment. English universities increased the numbers of students registered between 1924 and 1927 by 19 per cent, but in Scotland the numbers fell, particularly among women. In the same period, while expenditure in English universities rose by 90 per cent, in Scotland the increase was less than a third of that figure. In the 1960s the number of Scottish Universities doubled, with

The first half of the 20th century saw Scottish universities fall behind those in England and Europe in terms of participation and investment. The decline of traditional industries between the wars undermined recruitment. English universities increased the numbers of students registered between 1924 and 1927 by 19 per cent, but in Scotland the numbers fell, particularly among women. In the same period, while expenditure in English universities rose by 90 per cent, in Scotland the increase was less than a third of that figure. In the 1960s the number of Scottish Universities doubled, with

Decline of Gaelic

{{Scottish education

The history of education in Scotland in its modern sense of organised and institutional learning, began in the Middle Ages, when Church choir schools and

The history of education in Scotland in its modern sense of organised and institutional learning, began in the Middle Ages, when Church choir schools and grammar schools

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary sch ...

began educating boys. By the end of the 15th century schools were also being organised for girls and universities were founded at St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourt ...

, Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

and Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

. Education was encouraged by the Education Act 1496, which made it compulsory for the sons of barons and freeholders of substance to attend the grammar schools, which in turn helped increase literacy among the upper classes.

The Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Scotland broke with the Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterian in its outlook. It was part of the wider European Protestant Refo ...

resulted in major changes to the organisation and nature of education, with the loss of choir schools and the expansion of parish schools, along with the reform and expansion of the Universities. In the seventeenth century, legislation enforced the creation and funding of schools in every parish, often overseen by presbyteries of the local kirk. The existence of this network of schools later led to the growth of the "democratic myth" that poor boys had been able to use this system of education to rise to the top of Scottish society. However, Scotland's University system did help to make it one of the major contributors to the Enlightenment in the 18th century, producing major figures such as David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" '' Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment phil ...

and Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

.

Religious divisions and the impact of industrialisation, migration and immigration disrupted the existing educational system and in the late nineteenth century it was reorganised and expanded to produce a state-funded national system of free basic education and common examinations. The reform of Scottish universities made them major centres of learning and pioneers in the admission of women from 1892. In the 20th century Scottish secondary education expanded, particularly for girls, but the universities began to fall behind those in England and Europe in investment and expansion of numbers. The government of the education system became increasingly centred on Scotland, with the final move of the ministry of education to Edinburgh in 1939. After devolution in 1999 the Scottish Executive also created an Enterprise, Transport and Lifelong Learning Department and there was significant divergence from practice in England, including the abolition of student tuition fees at Scottish universities.

Middle Ages

In the Early Middle Ages, Scotland was overwhelmingly an oral society and education was verbal rather than literary. Fuller sources for Ireland of the same period suggest that there may have been filidh, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge in Gaelic to the next generation.R. A. Houston, ''Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600-1800'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), , p. 76. After the "de-gallicisation" of the Scottish court from the twelfth century, a less highly regarded order of

In the Early Middle Ages, Scotland was overwhelmingly an oral society and education was verbal rather than literary. Fuller sources for Ireland of the same period suggest that there may have been filidh, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge in Gaelic to the next generation.R. A. Houston, ''Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600-1800'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), , p. 76. After the "de-gallicisation" of the Scottish court from the twelfth century, a less highly regarded order of bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise ...

s took over these functions and they would continue to act in a similar role in the Highlands and Islands into the eighteenth century. They often trained in bardic schools, of which a few, like the one run by the MacMhuirich dynasty, who were bards to the Lord of the Isles

The Lord of the Isles or King of the Isles

( gd, Triath nan Eilean or ) is a title of Scottish nobility with historical roots that go back beyond the Kingdom of Scotland. It began with Somerled in the 12th century and thereafter the title ...

, existed in Scotland and a larger number in Ireland, until they were suppressed from the seventeenth century. Much of their work was never written down and what survives was only recorded from the sixteenth century.R. Crawford''Scotland's Books: A History of Scottish Literature''

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), . The establishment of Christianity brought Latin to Scotland as a scholarly and written language. Monasteries served as major repositories of knowledge and education, often running schools and providing a small educated elite, who were essential to create and read documents in a largely illiterate society.A. Macquarrie, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), , p. 128. In the High Middle Ages new sources of education arose, with

song

A song is a musical composition intended to be performed by the human voice. This is often done at distinct and fixed pitches (melodies) using patterns of sound and silence. Songs contain various forms, such as those including the repetitio ...

and grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary sch ...

s. These were usually attached to cathedrals or a collegiate church In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons: a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, which may be presided over b ...

and were most common in the developing burghs. By the end of the Middle Ages grammar schools could be found in all the main burghs and some small towns. Early examples including the High School of Glasgow

The High School of Glasgow is an independent, co-educational day school in Glasgow, Scotland. The original High School of Glasgow was founded as the choir school of Glasgow Cathedral in around 1124, and is the oldest school in Scotland, and th ...

in 1124 and the High School of Dundee in 1239. There were also petty schools, more common in rural areas and providing an elementary education.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (Random House, 2011), , pp. 104-7. Some monasteries, like the Cistercian abbey at Kinloss, opened their doors to a wider range of students. The number and size of these schools seems to have expanded rapidly from the 1380s. They were almost exclusively aimed at boys, but by the end of the fifteenth century, Edinburgh also had schools for girls, sometimes described as "sewing schools", and probably taught by lay women or nuns. There was also the development of private tuition in the families of lords and wealthy burghers. The growing emphasis on education cumulated with the passing of the Education Act 1496, which decreed that all sons of barons and freeholders of substance should attend grammar schools to learn "perfyct Latyne". All this resulted in an increase in literacy, but which was largely concentrated among a male and wealthy elite,P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, ''A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry'' (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), , pp. 29-30. with perhaps 60 per cent of the nobility being literate by the end of the period.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470-1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 68-72.

Until the fifteenth century, those who wished to attend university had to travel to England or the continent, and just over a 1,000 have been identified as doing so between the twelfth century and 1410. Among these the most important intellectual figure was

Until the fifteenth century, those who wished to attend university had to travel to England or the continent, and just over a 1,000 have been identified as doing so between the twelfth century and 1410. Among these the most important intellectual figure was John Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( – 8 November 1308), commonly called Duns Scotus ( ; ; "Duns the Scot"), was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher, and theologian. He is one of the four most important ...

, who studied at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge beca ...

and Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

and probably died at Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 million ...

in 1308, becoming a major influence on late medieval religious thought.B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (St. Martin's Press, 1997), , pp. 119. After the outbreak of the Wars of Independence, with occasional exceptions under safe conduct, English universities were closed to Scots and continental universities became more significant.B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (St. Martin's Press, 1997), , pp. 124-5. Some Scottish scholars became teachers in continental universities. At Paris this included John De Rate and Walter Wardlaw in the 1340s and 1350s, William de Tredbrum in the 1380s and Laurence de Lindores in the early 1500s. This situation was transformed by the founding of the University of St Andrews

(Aien aristeuein)

, motto_lang = grc

, mottoeng = Ever to ExcelorEver to be the Best

, established =

, type = Public research university

Ancient university

, endowment ...

in 1413, the University of Glasgow in 1451 and the University of Aberdeen

, mottoeng = The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom

, established =

, type = Public research universityAncient university

, endowment = £58.4 million (2021)

, budget ...

in 1495. Initially these institutions were designed for the training of clerics, but they would increasingly be used by laymen who would begin to challenge the clerical monopoly of administrative posts in the government and law. Those wanting to study for second degrees still needed to go elsewhere and Scottish scholars continued to visit the continent and English universities, which reopened to Scots in the late fifteenth century. The continued movement to other universities produced a school of Scottish nominalists

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are at least two main versions of nominalism. One version denies the existence of universalsthings th ...

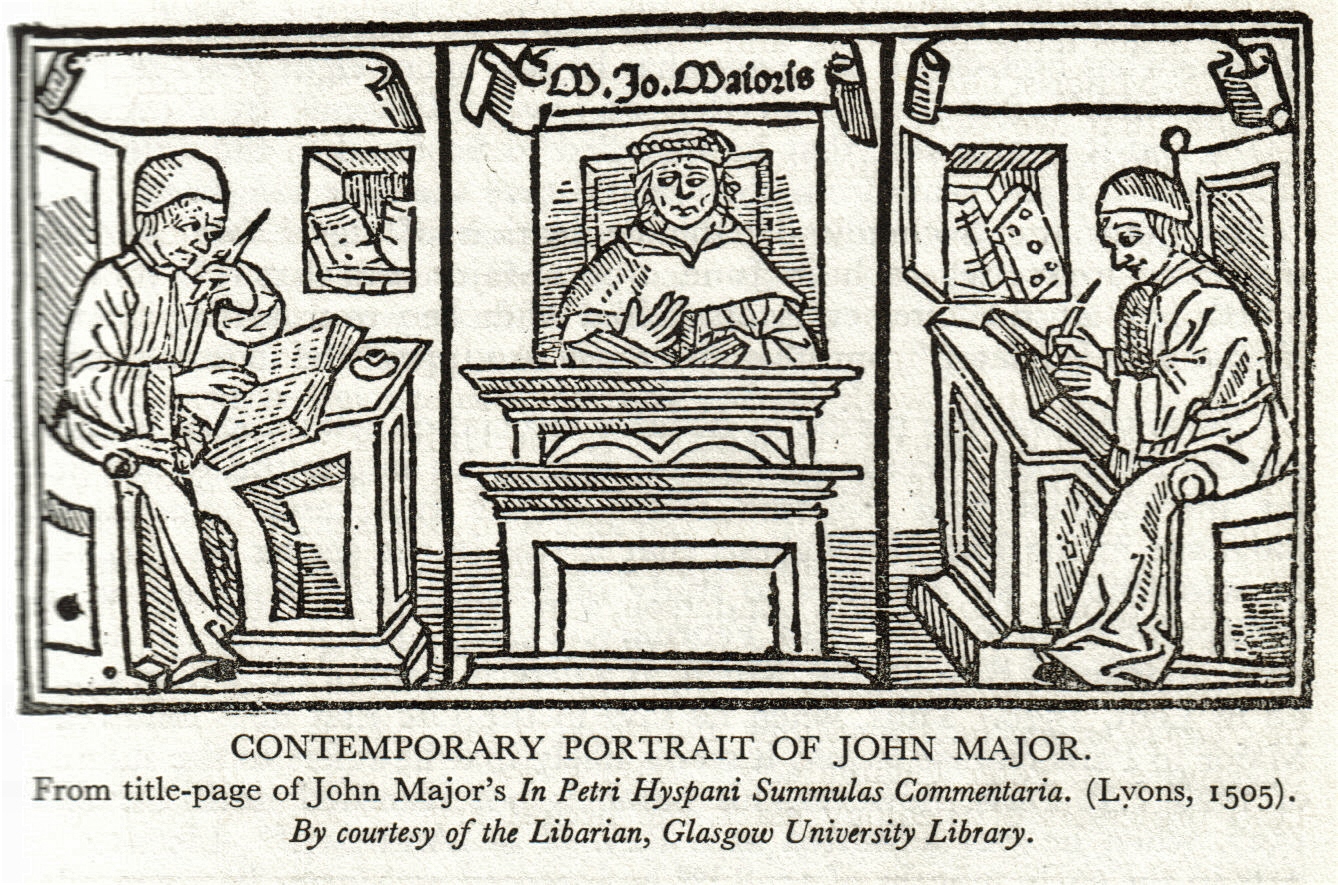

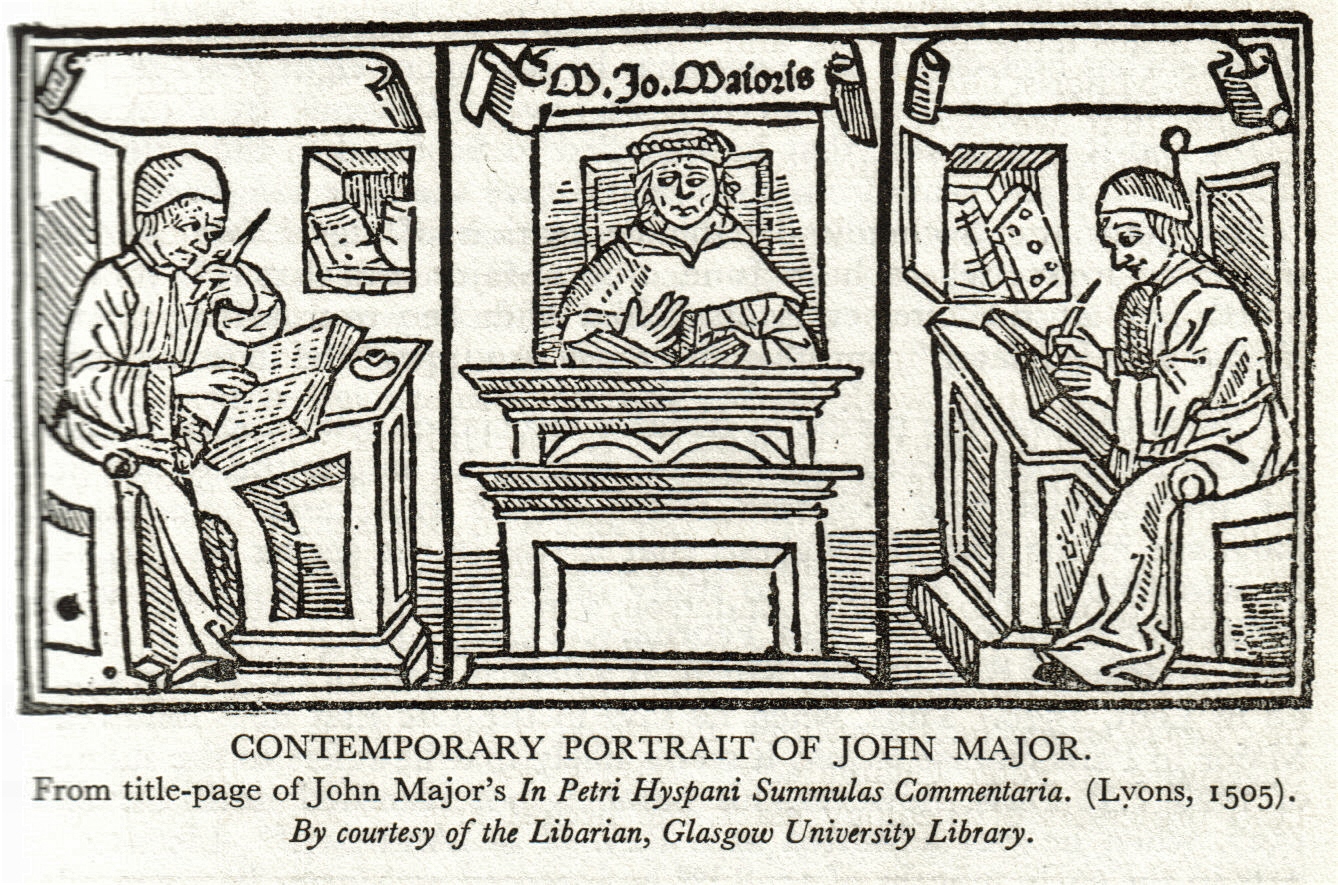

at Paris in the early sixteenth century, of which John Mair John Mair may refer to:

*John Major (philosopher)

John Major (or Mair; also known in Latin as ''Joannes Majoris'' and ''Haddingtonus Scotus''; 1467–1550) was a Scottish philosopher, theologian, and historian who was much admired in his day ...

was probably the most important figure. He had probably studied at a Scottish grammar school, then Cambridge, before moving to Paris, where he matriculated in 1493. By 1497 the humanist and historian Hector Boece

Hector Boece (; also spelled Boyce or Boise; 1465–1536), known in Latin as Hector Boecius or Boethius, was a Scottish philosopher and historian, and the first Principal of King's College in Aberdeen, a predecessor of the University of Abe ...

, born in Dundee and who had studied at Paris, returned to become the first principal at the new university of Aberdeen. These international contacts helped integrate Scotland into a wider European scholarly world and would be one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "huma ...

were brought into Scottish intellectual life.

Impact of the Reformation

The humanist concern with widening education was shared by the Protestant reformers, with a desire for a godly people replacing the aim of having educated citizens. In 1560, the '' First Book of Discipline'' set out a plan for a school in every parish, but this proved financially impossible. In the burghs the old schools were maintained, with the song schools and a number of new foundations becoming reformed grammar schools or ordinary parish schools. Schools were supported by a combination of kirk funds, contributions from local heritors or burgh councils and parents that could pay. They were inspected by kirk sessions, who checked for the quality of teaching and doctrinal purity. There were also large number of unregulated "adventure schools", which sometimes fulfilled a local needs and sometimes took pupils away from the official schools. Outside of the established burgh schools, masters often combined their position with other employment, particularly minor posts within the kirk, such as clerk. At their best, the curriculum included

The humanist concern with widening education was shared by the Protestant reformers, with a desire for a godly people replacing the aim of having educated citizens. In 1560, the '' First Book of Discipline'' set out a plan for a school in every parish, but this proved financially impossible. In the burghs the old schools were maintained, with the song schools and a number of new foundations becoming reformed grammar schools or ordinary parish schools. Schools were supported by a combination of kirk funds, contributions from local heritors or burgh councils and parents that could pay. They were inspected by kirk sessions, who checked for the quality of teaching and doctrinal purity. There were also large number of unregulated "adventure schools", which sometimes fulfilled a local needs and sometimes took pupils away from the official schools. Outside of the established burgh schools, masters often combined their position with other employment, particularly minor posts within the kirk, such as clerk. At their best, the curriculum included catechism

A catechism (; from grc, κατηχέω, "to teach orally") is a summary or exposition of doctrine and serves as a learning introduction to the Sacraments traditionally used in catechesis, or Christian religious teaching of children and adul ...

, Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, French, Classical literature

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classi ...

and sports.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470-1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 183-3.

In 1616 an act in Privy council commanded every parish to establish a school "where convenient means may be had", and when the Parliament of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland ( sco, Pairlament o Scotland; gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba) was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland from the 13th century until 1707. The parliament evolved during the early 13th century from the king's council of ...

ratified this with the Education Act of 1633, a tax on local landowners was introduced to provide the necessary endowment. A loophole which allowed evasion of this tax was closed in the Education Act of 1646, which established a solid institutional foundation for schools on Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covena ...

principles. Although the Restoration brought a reversion to the 1633 position, in 1696 new legislation restored the provisions of 1646 together with means of enforcement "more suitable to the age". Underlining the aim of having a school in every parish. In rural communities these obliged local landowners (heritors) to provide a schoolhouse and pay a schoolmaster, while ministers and local presbyteries oversaw the quality of the education. In many Scottish towns, burgh schools were operated by local councils. By the late seventeenth century there was a largely complete network of parish schools in the lowlands, but in the Highlands basic education was still lacking in many areas.R. Anderson, "The history of Scottish Education pre-1980", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, ''Scottish Education: Post-Devolution'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), , pp. 219-28.

The widespread belief in the limited intellectual and moral capacity of women, vied with a desire, intensified after the Reformation, for women to take personal moral responsibility, particularly as wives and mothers. In Protestantism this necessitated an ability to learn and understand the catechism

A catechism (; from grc, κατηχέω, "to teach orally") is a summary or exposition of doctrine and serves as a learning introduction to the Sacraments traditionally used in catechesis, or Christian religious teaching of children and adul ...

and even to be able to independently read the Bible, but most commentators, even those that tended to encourage the education of girls, thought they should not receive the same academic education as boys. In the lower ranks of society, they benefited from the expansion of the parish schools system that took place after the Reformation, but were usually outnumbered by boys, often taught separately, for a shorter time and to a lower level. They were frequently taught reading, sewing and knitting, but not writing. Female illiteracy rates based on signatures among female servants were around 90 percent, from the late seventeenth to the early eighteenth centuries and perhaps 85 percent for women of all ranks by 1750, compared with 35 per cent for men. Among the nobility there were many educated and cultured women, of which Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Sc ...

is the most obvious example.

After the Reformation, Scotland's universities underwent a series of reforms associated with Andrew Melville, who returned from Geneva to become principal of the University of Glasgow in 1574. A distinguished linguist, philosopher and poet, he had trained in Paris and studied law at

After the Reformation, Scotland's universities underwent a series of reforms associated with Andrew Melville, who returned from Geneva to become principal of the University of Glasgow in 1574. A distinguished linguist, philosopher and poet, he had trained in Paris and studied law at Poitiers

Poitiers (, , , ; Poitevin: ''Poetàe'') is a city on the River Clain in west-central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and the historical centre of Poitou. In 2017 it had a population of 88,291. Its agglomer ...

, before moving to Geneva and developing an interest in Protestant theology. Influenced by the anti-Aristotelian Petrus Ramus

Petrus Ramus (french: Pierre de La Ramée; Anglicized as Peter Ramus ; 1515 – 26 August 1572) was a French humanist, logician, and educational reformer. A Protestant convert, he was a victim of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.

Early life

...

, he placed an emphasis on simplified logic and elevated languages and sciences to the same status as philosophy, allowing accepted ideas in all areas to be challenged. He introduced new specialist teaching staff, replacing the system of "regenting", where one tutor took the students through the entire arts curriculum. Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of consci ...

were abandoned and Greek became compulsory in the first year followed by Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated in ...

, Syriac and Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, launching a new fashion for ancient and biblical languages. Glasgow had probably been declining as a university before his arrival, but students now began to arrive in large numbers. He assisted in the reconstruction of Marischal College

Marischal College ( ) is a large granite building on Broad Street in the centre of Aberdeen in north-east Scotland, and since 2011 has acted as the headquarters of Aberdeen City Council. However, the building was constructed for and is on long ...

, Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

, and in order to do for St Andrews what he had done for Glasgow, he was appointed Principal of St Mary's College, St Andrews, in 1580. The University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in ...

developed out of public lectures were established in the town 1540s on law, Greek, Latin and philosophy, under the patronage of Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (french: Marie de Guise; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was a French noblewoman of the House of Guise, a cadet branch of the House of Lorraine and one of the most powerful families in France. She ...

. These evolved into the "Tounis College", which would become the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in ...

in 1582.A. Thomas, ''The Renaissance'', in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, ''The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), , pp. 196-7. The results were a revitalisation of all Scottish universities, which were now producing a quality of education the equal of that offered anywhere in Europe.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470-1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 183-4. Under the Commonwealth, the universities saw an improvement in their funding, as they were given income from deaneries, defunct bishoprics and the excise, allowing the completion of buildings including the college in the High Street

High Street is a common street name for the primary business street of a city, town, or village, especially in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth. It implies that it is the focal point for business, especially shopping. It is also a metonym ...

in Glasgow. They were still largely seen as a training school for clergy, and came under the control of the hard line Protestors, who were generally favoured by the regime because of their greater antipathy to royalism, with Patrick Gillespie being made Principal at Glasgow.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , pp. 227-8. After the Restoration there was a purge of the universities, but much of the intellectual advances of the preceding period was preserved.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (Random House, 2011), , p. 262. The five Scottish universities recovered with a lecture-based curriculum that was able to embrace economics and science, offering a high quality liberal education to the sons of the nobility and gentry. It helped the universities to become major centres of medical education and would put Scotland at the forefront of Enlightenment thinking.

Eighteenth century

How the Scots Invented the Modern World

How may refer to:

* How (greeting), a word used in some misrepresentations of Native American/First Nations speech

* How, an interrogative word in English grammar

Art and entertainment Literature

* ''How'' (book), a 2007 book by Dov Seidma ...

'' (London: Crown Publishing Group, 2001), . Scottish thinkers began questioning assumptions previously taken for granted; and with Scotland's traditional connections to France, then in the throes of the Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

, the Scots began developing a uniquely practical branch of humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "huma ...

. Major thinkers produced by this system included Francis Hutcheson, who held the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Glasgow from 1729 to 1746, who helped develop Utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different chara ...

and consequentialist

In ethical philosophy, consequentialism is a class of normative, teleological ethical theories that holds that the consequences of one's conduct are the ultimate basis for judgment about the rightness or wrongness of that conduct. Thus, from ...

thinking. Some modern attitudes towards the relationship between science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

and religion

Religion is usually defined as a social-cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

were developed by his proteges David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" '' Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment phil ...

and Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

.

By the eighteenth century many poorer girls were being taught in dame schools, informally set up by a widow or spinster to teach reading, sewing and cooking. Among members of the aristocracy by the early eighteenth century a girl's education was expected to include basic literacy and numeracy, needlework and cookery and household management, while polite accomplishments and piety were also emphasised.

In the Scottish Highlands as well as problems of distance and physical isolation, most people spoke Gaelic which few teachers and ministers could understand. Here the Kirk's parish schools were supplemented by the

In the Scottish Highlands as well as problems of distance and physical isolation, most people spoke Gaelic which few teachers and ministers could understand. Here the Kirk's parish schools were supplemented by the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge

The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) is a UK-based Christian charity. Founded in 1698 by Thomas Bray, it has worked for over 300 years to increase awareness of the Christian faith in the UK and across the world.

The SPCK is th ...

, established in 1709. Their aim was to teach English language and end Roman Catholicism associated with rebellious Jacobitism. Though the Gaelic Society schools taught the Bible in Gaelic, the overall effect contributed to the erosion of Highland culture.

Throughout the last part of the century schools and universities also benefitted from the robust educational publishing industry that existed across the Lowlands and which printed primers, dabbity sheets, textbooks, lecture heads and other kinds of effective learning tools that helped students remember information.

In the eighteenth century Scotland's universities went from being small and parochial institutions, largely for the training of clergy and lawyers, to major intellectual centres at the forefront of Scottish identity and life, seen as fundamental to democratic principles and the opportunity for social advancement for the talented.R. D. Anderson, "Universities: 2. 1720–1960", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 612-14. Chairs of medicine were founded at Marsichial College (1700), Glasgow (1713), St. Andrews (1722) and a chair of chemistry and medicine at Edinburgh (1713). It was Edinburgh's medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, MB ...

, founded in 1732 that came to dominate. By the 1740s it had displaced Leiden

Leiden (; in English and archaic Dutch also Leyden) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. The municipality of Leiden has a population of 119,713, but the city forms one densely connected agglomeration w ...

as the major centre of medicine in Europe and was a leading centre in the Atlantic world. The universities still had their difficulties. The economic downturn in the mid-century forced the closure of St Leonard's College in St Andrews, whose properties and staff were merged into St Salvator's College to form the United College of St Salvator and St Leonard.

European Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

.

Many of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment were university professors, who developed their ideas in university lectures. They included Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746), who held the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Glasgow from 1729 to 1746, whose ideas were developed by his protégés David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" '' Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment phil ...

(1711–76), who became a major figure in the sceptical philosophical and empiricist

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empiri ...

traditions of philosophy,. and Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

(1723–90), whose ''The Wealth of Nations

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', generally referred to by its shortened title ''The Wealth of Nations'', is the ''magnum opus'' of the Scottish economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith. First published in 1 ...

'', (1776) is considered to be the first work of modern economics.M. Fry, ''Adam Smith's Legacy: His Place in the Development of Modern Economics'' (London: Routledge, 1992), . Hugh Blair

Hugh Blair FRSE (7 April 1718 – 27 December 1800) was a Scottish minister of religion, author and rhetorician, considered one of the first great theorists of written discourse.

As a minister of the Church of Scotland, and occupant of the C ...

(1718–1800) was a minister of the Church of Scotland and held the Chair of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres at the University of Edinburgh. He produced an edition of the works of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

and is best known for ''Sermons'' (1777-1801), Lectures on Rhetoric and ''Belles Lettres'' (1783). The focus of the Scottish Enlightenment ranged from intellectual and economic matters to the specifically scientific as in the work of William Cullen

William Cullen FRS FRSE FRCPE FPSG (; 15 April 17105 February 1790) was a Scottish physician, chemist and agriculturalist, and professor at the Edinburgh Medical School. Cullen was a central figure in the Scottish Enlightenment: He was ...

, physician and chemist, James Anderson, an agronomist

An agriculturist, agriculturalist, agrologist, or agronomist (abbreviated as agr.), is a professional in the science, practice, and management of agriculture and agribusiness. It is a regulated profession in Canada, India, the Philippines, the U ...

, Joseph Black

Joseph Black (16 April 1728 – 6 December 1799) was a Scottish physicist and chemist, known for his discoveries of magnesium, latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide. He was Professor of Anatomy and Chemistry at the University of Glas ...

, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate caus ...

and chemist, and James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June O.S.172614 June 1726 New Style. – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, agriculturalist, chemical manufacturer, naturalist and physician. Often referred to as the father of modern geology, he played a key role ...

, the first modern geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, alth ...

.J. Repcheck, ''The Man Who Found Time: James Hutton and the Discovery of the Earth's Antiquity'' (Cambridge, MA: Basic Books, 2003), , pp. 117–43.

Nineteenth century

Industrialisation, urbanisation and the

Industrialisation, urbanisation and the Disruption of 1843

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland to form the Free Church of Scotland.

The main conflict was over whether the Church of S ...

all undermined the tradition of parish schools.T. M. Devine, ''The Scottish Nation, 1700-2000'' (London: Penguin Books, 2001), , pp. 91-100. 408 teachers in schools joined the breakaway Free Church of Scotland. By May 1847 it was claimed that 513 schoolmasters were being paid direct from a central education fund and over 44,000 children being taught in Free Church Schools.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (Random House, 2011), , p. 397. Attempts to supplement the parish system included Sunday Schools

A Sunday school is an educational institution, usually (but not always) Christian in character. Other religions including Buddhism, Islam, and Judaism have also organised Sunday schools in their temples and mosques, particularly in the West.

Su ...

. Originally begun in the 1780s by town councils, they were adopted by all religious denominations in the nineteenth century. By the 1830s and 1840s these had widened to include mission school

The Mission School (sometimes called "New Folk" or "Urban Rustic") is an art movement of the 1990s and 2000s, centered in the Mission District, San Francisco, California.

History and characteristics

This movement is generally considered to hav ...

s, ragged schools, Bible societies

A Bible society is a non-profit organization, usually nondenominational in makeup, devoted to translating, publishing, and distributing the Bible at affordable prices. In recent years they also are increasingly involved in advocating its credi ...

and improvement classes, open to members of all forms of Protestantism and particularly aimed at the growing urban working classes. By 1890 the Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

s had more Sunday schools than churches and were teaching over 10,000 children. The number would double by 1914.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , p. 403. From 1830 the state began to fund buildings with grants, then from 1846 it was funding schools by direct sponsorship, and in 1872 Scotland moved to a system like that in England of state-sponsored largely free schools, run by local school board

A board of education, school committee or school board is the board of directors or board of trustees of a school, local school district or an equivalent institution.

The elected council determines the educational policy in a small regional are ...

s. Overall administration was in the hands of the Scotch (later Scottish) Education Department in London. Education was now compulsory from five to thirteen and many new board schools were built. Larger urban school boards established "higher grade" (secondary) schools as a cheaper alternative to the burgh schools. The Scottish Education Department introduced a Leaving Certificate Examination in 1888 to set national standards for secondary education and in 1890 school fees were abolished, creating a state-funded national system of free basic education and common examinations.

At the beginning of the 19th century Scottish universities had no entrance exam, students typically entered at ages of 15 or 16, attended for as little as two years, chose which lectures to attend and left without qualifications. After two commissions of enquiry in 1826 and 1876 and reforming acts of parliament in 1858 and 1889, the curriculum and system of graduation were reformed to meet the needs of the emerging middle classes and the professions. Entrance examinations equivalent to the School Leaving Certificate were introduced and average ages of entry had risen to 17 or 18. Standard patterns of graduation in the arts curriculum offered 3-year ordinary and 4-year honours degrees and separate science faculties were able to move away from the compulsory Latin, Greek and philosophy of the old MA curriculum.R. Anderson, "The history of Scottish Education pre-1980", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, ''Scottish Education: Post-Devolution'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), , p. 224. The historic University of Glasgow became a leader in British higher education by providing the educational needs of youth from the urban and commercial classes, as well as the upper class. It prepared students for non-commercial careers in government, the law, medicine, education, and the ministry and a smaller group for careers in science and engineering. St Andrews pioneered the admission of women to Scottish universities, creating the Lady Licentiate in Arts (LLA), which proved highly popular. From 1892 Scottish universities could admit and graduate women and the numbers of women at Scottish universities steadily increased until the early 20th century.M. F. Rayner-Canham and G. Rayner-Canham, ''Chemistry was Their Life: Pioneering British Women Chemists, 1880-1949'', (Imperial College Press, 2008), , p. 264.

Twentieth century

The Scottish education system underwent radical change and expansion in the 20th century. In 1918 Roman Catholic schools were brought into the system, but retained their distinct religious character, access to schools by priests and the requirement that school staff be acceptable to the Church. The school leaving age was raised to 14 in 1901, and although plans to raise it to 15 in the 1940s were never ratified, increasing numbers stayed on beyond elementary education and it was eventually raised to 16 in 1973. As a result, secondary education was the major area of growth in the inter-war period, particularly for girls, who stayed on in full-time education in increasing numbers throughout the century.C. Harvie, ''No Gods and Precious Few Heroes: Twentieth-Century Scotland'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 3rd edn., 1998), , p. 78. New qualifications were developed to cope with changing aspirations and economics, with the Leaving Certificate being replaced by the

The Scottish education system underwent radical change and expansion in the 20th century. In 1918 Roman Catholic schools were brought into the system, but retained their distinct religious character, access to schools by priests and the requirement that school staff be acceptable to the Church. The school leaving age was raised to 14 in 1901, and although plans to raise it to 15 in the 1940s were never ratified, increasing numbers stayed on beyond elementary education and it was eventually raised to 16 in 1973. As a result, secondary education was the major area of growth in the inter-war period, particularly for girls, who stayed on in full-time education in increasing numbers throughout the century.C. Harvie, ''No Gods and Precious Few Heroes: Twentieth-Century Scotland'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 3rd edn., 1998), , p. 78. New qualifications were developed to cope with changing aspirations and economics, with the Leaving Certificate being replaced by the Scottish Certificate of Education

The Scottish Certificate of Education (or SCE) was a Scottish secondary education certificate, used in schools and sixth form institutions, from 1962 until 1999. It replaced the older Junior Secondary Certificate (JSC) and the Scottish Leaving Cer ...

Ordinary Grade ('O-Grade') and Higher Grade

In the Scottish secondary education system, the Higher () is one of the national school-leaving certificate exams and university entrance qualifications of the Scottish Qualifications Certificate (SQC) offered by the Scottish Qualifications ...

('Higher') qualifications in 1962, which became the basic entry qualification for university study. The centre of the education system also became more focused on Scotland, with the ministry of education partly moving north in 1918 and then finally having its headquarters relocated to Edinburgh in 1939.

The first half of the 20th century saw Scottish universities fall behind those in England and Europe in terms of participation and investment. The decline of traditional industries between the wars undermined recruitment. English universities increased the numbers of students registered between 1924 and 1927 by 19 per cent, but in Scotland the numbers fell, particularly among women. In the same period, while expenditure in English universities rose by 90 per cent, in Scotland the increase was less than a third of that figure. In the 1960s the number of Scottish Universities doubled, with

The first half of the 20th century saw Scottish universities fall behind those in England and Europe in terms of participation and investment. The decline of traditional industries between the wars undermined recruitment. English universities increased the numbers of students registered between 1924 and 1927 by 19 per cent, but in Scotland the numbers fell, particularly among women. In the same period, while expenditure in English universities rose by 90 per cent, in Scotland the increase was less than a third of that figure. In the 1960s the number of Scottish Universities doubled, with Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, fourth-largest city and the List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mi ...

being demerged from St. Andrews, Strathclyde

Strathclyde ( in Gaelic, meaning "strath (valley) of the River Clyde") was one of nine former local government regions of Scotland created in 1975 by the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 and abolished in 1996 by the Local Government et ...

and Heriot-Watt developing from Scottish Office "central institutions" and Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Central Belt, central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town#Scotland, market town, surrounded by rich farmland, ...

beginning as a completely new university on a greenfield site in 1966. Five existing degree awarding institutions became universities after 1992, as a result of the Further and Higher Education Act 1992

The Further and Higher Education Act 1992 made changes in the funding and administration of further education and higher education within England and Wales, with consequential effects on associated matters in Scotland which had previously been ...

. These were Abertay, Glasgow Caledonian, Napier, Paisley and Robert Gordon. In 2001 the University of the Highlands and Islands

The University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI) is an integrated, tertiary institution encompassing both further and higher education. It is composed of 12 colleges and research institutions spread around the Highlands and Islands, Moray and Per ...

was created by a federation of 13 colleges and research institutions in the Highlands and Islands.

After devolution, in 1999 the new Scottish Executive set up an Education Department and an Enterprise, Transport and Lifelong Learning Department, which together took over its functions.J. Fairley, "The Enterprise and Lifelong Learning Department and the Scottish Parliament", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, ''Scottish Education: Post-Devolution'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), , pp. 132-40. One of the major diversions from practice in England, possible because of devolution, was the abolition of student tuition fees in 1999, instead retaining a system of means-tested student grants.D. Cauldwell, "Scottish Higher Education: Character and Provision", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, ''Scottish Education: Post-Devolution'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), , pp. 62-73.

The current education system

For a description of the current education system in Scotland, seeEducation in Scotland

Education in Scotland is overseen by the Scottish Government and its executive agency Education Scotland. Education in Scotland has a history of universal provision of public education, and the Scottish education system is distinctly differe ...

See also

* Gaelic medium education in Scotland * List of further and higher education colleges in ScotlandNotes

Further reading

* Anderson, R. D. ''Education and the Scottish People, 1750-1918'' (1995). * Anderson, R. D. "The history of Scottish Education pre-1980", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, ''Scottish Education: Post-Devolution'' (2nd ed., 2003), pp. 219–28. * Hendrie, William F. ''The dominie: a profile of the Scottish headmaster'' (1997) * O'Hagan, Francis J. ''The contribution of the religious orders to education in Glasgow during the period, 1847-1918'' (2006), on Catholics * Raftery, Deirdre, Jane McDermid, and Gareth Elwyn Jones, "Social Change and Education in Ireland, Scotland and Wales: Historiography on Nineteenth-century Schooling," ''History of Education'', July/Sept 2007, Vol. 36 Issue 4/5, pp 447–463 * Smout, T. C. ''A History of the Scottish People'', Fontana Press 1985,External links

Decline of Gaelic

{{Scottish education