Imprisonment began to replace other forms of criminal punishment in the United States just before the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, though penal incarceration efforts had been ongoing in

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

since as early as the 1500s, and

prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, corre ...

s in the form of

dungeon

A dungeon is a room or cell in which prisoners are held, especially underground. Dungeons are generally associated with medieval castles, though their association with torture probably belongs more to the Renaissance period. An oubliette (from ...

s and various detention facilities had existed as early as the first sovereign states. In colonial times, courts and magistrates would impose punishments including fines, forced labor, public restraint, flogging, maiming, and death, with sheriffs detaining some defendants awaiting trial. The use of confinement as a punishment in itself was originally seen as a more humane alternative to capital and corporal punishment, especially among Quakers in Pennsylvania. Prison building efforts in the United States came in three major waves. The first began during the

Jacksonian Era

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21, and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, A ...

and led to the widespread use of imprisonment and

rehabilitative labor as the primary penalty for most crimes in nearly all states by the time of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. The second began after the Civil War and gained momentum during the

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

, bringing a number of new mechanisms—such as

parole

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

,

probation

Probation in criminal law is a period of supervision over an offender, ordered by the court often in lieu of incarceration.

In some jurisdictions, the term ''probation'' applies only to community sentences (alternatives to incarceration), such ...

, and

indeterminate sentencing

Indefinite imprisonment or indeterminate imprisonment is the imposition of a sentence by imprisonment with no definite period of time set during sentencing. It was imposed by certain nations in the past, before the drafting of the United Nat ...

—into the mainstream of American penal practice. Finally, since the early 1970s, the United States has engaged in a historically unprecedented expansion of its imprisonment systems at both the federal and state level. Since 1973, the

number of incarcerated persons in the United States has increased five-fold. Now, about 2,200,000 people, or 3.2 percent of the adult population, are imprisoned in the United States,

[Gottschalk, 1–2.] and about 7,000,000 are under supervision of some form in the correctional system, including parole and probation.

Periods of prison construction and reform produced major changes in the structure of prison systems and their missions, the responsibilities of federal and state agencies for administering and supervising them, as well as the legal and political status of prisoners themselves.

Intellectual origins of United States prisons

Incarceration as a form of criminal punishment is "a comparatively recent episode in Anglo-American jurisprudence," according to historian Adam J. Hirsch.

[Hirsch, xi.] Before the nineteenth century, sentences of penal confinement were rare in the criminal courts of British North America.

[ But penal incarceration had been utilized in England as early as the reign of the ]Tudors

The House of Tudor was a royal house of largely Welsh and English origin that held the English throne from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd and Catherine of France. Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of England and its ...

, if not before.[Hirsch, 13.] When post-revolutionary prisons emerged in the United States, they were, in Hirsch's words, not a "fundamental departure" from the former American colonies' intellectual past.[Hirsch, 31.] Early American prisons systems like Massachusetts' Castle Island Penitentiary, built in 1780, essentially imitated the model of the 1500s English workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

.[

]

Prisons in America

Although early colonization of prisons were influenced by the England law and Sovereignty and their reactions to criminal offenses, it also had a mix of religious aptitude toward the punishment of the crime. Because of the low population in the eastern states it was hard to follow the criminal codes in place and which led to law changes in America. It was the population boom in the eastern states that led to the reformation of the prison system in the U.S. According to the Oxford History of the Prison, in order to function prisons "keep prisoners in custody, maintain order, control discipline and a safe environment, provide decent conditions for prisoners and meet their needs, including health care, provide positive regimes which help prisoners address their offending behavior and allow them as full responsible a life as possible and help prisoners prepare for their return to their community"New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

because they were too "barbarous and had Monarchial principles,"Walnut Street Jail

Walnut Street Prison was a city jail and penitentiary house in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 1790 to 1838. Legislation calling for establishment of the jail was passed in 1773 to relieve overcrowding in the High Street Jail; the first prison ...

. This led to uprisings of state prisons across the eastern border states of America. Newgate State Prison in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

was built in 1796, New Jersey added its prison facility in 1797, Virginia and Kentucky in 1800, and Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maryland followed soon after.

Americans were in favour of reform in the early 1800s. They had ideas that rehabilitating prisoners to become law-abiding citizens was the next step. They needed to change the prison system's functions. Jacksonian American reformers hoped that changing the way they developed the institutions would give the inmates the tools needed to change.

The English workhouse

The English

The English workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

, an intellectual forerunner of early United States penitentiaries, was first developed as a "cure" for the idleness of the poor. Over time English officials and reformers came to see the workhouse as a more general system for rehabilitating criminals of all kinds.

Common wisdom in the England of the 1500s attributed property crime to idleness. "Idleness" had been a status crime since Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

enacted the Statute of Laborers in the mid-fourteenth century.[ By 1530, English subjects convicted of leading a "Rogishe or Vagabonds Trade or Lyfe" were subject to whipping and mutilation, and recidivists could face the death penalty.][

In 1557, many in England perceived that vagrancy was on the rise.][Hirsch, 14; McKelvey, 3.] That same year, the City of London reopened the Bridewell

Bridewell Palace in London was built as a residence of King Henry VIII and was one of his homes early in his reign for eight years. Given to the City of London Corporation by his son King Edward VI for use as an orphanage and place of cor ...

as a warehouse for vagrants arrested within the city limits.[Hirsch, 14.] In the decades that followed, "houses of correction" or "workhouses

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

" like the Bridewell became a fixture of towns across England—a change made permanent when Parliament began requiring every county in the realm to build a workhouse in 1576.[

The workhouse was not just a custodial institution. At least some of its proponents hoped that the experience of incarceration would rehabilitate workhouse residents through hard labor.][ Supporters expressed the belief that forced abstinence from "idleness" would make vagrants into productive citizens.][ Other supporters argued that the threat of the workhouse would deter vagrancy, and that inmate labor could provide a means of support for the workhouse itself.][ Governance of these institutions was controlled by written regulations promulgated by local authorities, and local justices of the peace monitored compliance.

Although "vagrants" were the first inhabitants of the workhouse—not felons or other criminals—expansion of its use to criminals was discussed. ]Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lor ...

described in ''Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island soc ...

'' (1516) how an ideal government should punish citizens with slavery, not death, and expressly recommended use of penal enslavement in England.[''See'' Hirsch, 16.] Thomas Starkey

Thomas Starkey (c. 1498–1538) was an English political theorist, humanist, and royal servant.

Life

Starkey was born in Cheshire, probably at Wrenbury, to Thomas Starkey and Maud Mainwaring. His father likely held office in Wales and was weal ...

, chaplain to Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, suggested that convicted felons "be put in some commyn work . . . so by theyr life yet the commyn welth schold take some profit."[ Edward Hext, justice of the peace in ]Somersetshire

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

in the 1500s, recommended that criminals be put to labor in the workhouse after receiving the traditional punishments of the day.[

] During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, several programs experimented with sentencing various petty criminals to the workhouse.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, several programs experimented with sentencing various petty criminals to the workhouse.[ Many petty criminals were sentenced to the workhouse by way of the vagrancy laws even before these efforts.][Hirsch, 17.] A commission appointed by King James I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

in 1622 to reprieve felons condemned to death with banishment to the American colonies was also given authority to sentence offenders "to toyle in some such heavie and painful manuall workes and labors here at home and be kept in chains in the house of correction or other places," until the King or his ministers decided otherwise.[ Within three years, a growing body of laws authorized incarceration in the workhouse for specifically enumerated petty crimes.][

Throughout the 1700s, even as England's "]Bloody Code

The "Bloody Code" was a series of laws in England, Wales and Ireland in the 18th and early 19th centuries which mandated the death penalty for a wide range of crimes. It was not referred to as such in its own time, but the name was given later ...

" took shape, incarceration at hard labor was held out as an acceptable punishment for criminals of various kinds—''e.g.'', those who received a suspended death sentence via the benefit of clergy

In English law, the benefit of clergy (Law Latin: ''privilegium clericale'') was originally a provision by which clergymen accused of a crime could claim that they were outside the jurisdiction of the secular courts and be tried instead in an ec ...

or a pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

, those who were not transported to the colonies, or those convicted of petty larceny

Larceny is a crime involving the unlawful taking or theft of the personal property of another person or business. It was an offence under the common law of England and became an offence in jurisdictions which incorporated the common law of Eng ...

. In 1779—at a time when the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

had made convict transportation

Penal transportation or transportation was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies became their d ...

to North America impracticable—the English Parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised t ...

passed the Penitentiary Act

The Penitentiary Act (19 Geo. III, c.74) was a British Act of Parliament passed in 1779 which introduced a policy of state prisons for the first time. The Act was drafted by the prison reformer John Howard and the jurist William Blackstone and rec ...

, mandating the construction of two London prisons with internal regulations modeled on the Dutch workhouse—''i.e.'', prisoners would labor more or less constantly during the day, with their diet, clothing, and communication strictly controlled. Although the Penitentiary Act promised to make penal incarceration the focal point of English criminal law,[Meranze, 141.] a series of the penitentiaries it prescribed were never constructed.[Hirsch, 18.]

Despite the ultimate failure of the Penitentiary Act, however, the legislation marked the culmination of a series of legislative efforts that "disclose[] the . . . antiquity, continuity, and durability" of rehabilitative incarceration ideology in Anglo-American criminal law, according to historian Adam J. Hirsch.[ The first United States penitentiaries involved elements of the early English workhouses—hard labor by day and strict supervision of inmates.

]

English philanthropist penology

A second group that supported penal incarceration in England included clergymen and "lay pietists" of various religious denominations who made efforts during the 1700s to reduce the severity of the English criminal justice system.

A second group that supported penal incarceration in England included clergymen and "lay pietists" of various religious denominations who made efforts during the 1700s to reduce the severity of the English criminal justice system.[ Initially, reformers like ]John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007, holding office as leader of the Liberal Party. His eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the ...

focused on the harsh conditions of pre-trial detention in English jails.[ But many philanthropists did not limit their efforts to jail administration and inmate hygiene; they were also interested in the spiritual health of inmates and curbing the common practice of mixing all prisoners together at random.][Hirsch, 19.] Their ideas about inmate classification and solitary confinement match another undercurrent of penal innovation in the United States that persisted into the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

.

Beginning with Samuel Denne's ''Letter to Lord Ladbroke'' (1771) and Jonas Hanway

Jonas Hanway (12 August 1712 – 5 September 1786), was a British philanthropist and traveller. He was the first male Londoner to carry an umbrella and was a noted opponent of tea drinking.

Life

Hanway was born in Portsmouth, on the south co ...

's ''Solitude in Imprisonment'' (1776), philanthropic literature on English penal reform began to concentrate on the post-conviction rehabilitation of criminals in the prison setting. Although they did not speak with a single voice, the philanthropist penologists tended to view crime as an outbreak of the criminal's estrangement from God.[ Hanway, for example, believed that the challenge of rehabilitating the criminal law lay in restoring his faith in, and fear of the ]Christian God

God in Christianity is believed to be the eternal, supreme being who created and preserves all things. Christians believe in a monotheistic conception of God, which is both transcendent (wholly independent of, and removed from, the material ...

, in order to "qualify imfor happiness in both worlds."

Many eighteenth-century English philanthropists proposed

Many eighteenth-century English philanthropists proposed solitary confinement

Solitary confinement is a form of imprisonment in which the inmate lives in a single cell with little or no meaningful contact with other people. A prison may enforce stricter measures to control contraband on a solitary prisoner and use additi ...

as a way to rehabilitate inmates morally.[ Since at least 1740, philanthropic thinkers touted the use of penal solitude for two primary purposes: (1) to isolate prison inmates from the moral contagion of other prisoners, and (2) to jump-start their spiritual recovery.][ The philanthropists found solitude far superior to hard labor, which only reached the convict's worldly self, failing to get at the underlying spiritual causes of crime.][ In their conception of prison as a "penitentiary," or place of repentance for sin, the English philanthropists departed from Continental models and gave birth to a largely novel idea—according to social historians Michael Meranze and Michael Ignatieff—which in turn found its way into penal practice in the United States.

A major political obstacle to implementing the philanthropists' solitary program in England was financial: Building individual cells for each prisoner cost more than the congregate housing arrangements typical of eighteenth-century English jails.][Hirsch, 20.] But by the 1790s, local solitary confinement facilities for convicted criminals appeared in Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of ...

and several other English counties.John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007, holding office as leader of the Liberal Party. His eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the ...

[ And the archetypical penitentiaries that emerged in the 1820s United States—''e.g.'', Auburn and Eastern State penitentiaries—both implemented a solitary regime aimed at morally rehabilitating prisoners. The concept of inmate classification—or dividing prisoners according to their behavior, age, etc.—remains in use in United States prisons to this day.

]

Rationalist penology

A third group involved in English penal reform were the "rationalists" or "utlitarians". According to historian Adam J. Hirsch, eighteenth-century rationalist criminology "rejected scripture in favor of human logic and reason as the only valid guide to constructing social institutions.

Eighteenth-century rational philosophers like

A third group involved in English penal reform were the "rationalists" or "utlitarians". According to historian Adam J. Hirsch, eighteenth-century rationalist criminology "rejected scripture in favor of human logic and reason as the only valid guide to constructing social institutions.

Eighteenth-century rational philosophers like Cesare Beccaria

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, Marquis of Gualdrasco and Villareggio (; 15 March 173828 November 1794) was an Italian criminologist, jurist, philosopher, economist and politician, who is widely considered one of the greatest thinkers of the Age ...

and developed a "novel theory of crime"—specifically, that what made an action subject to criminal punishment was the harm it caused to other members of society.[Hirsch, 21.] For the rationalists, sins that did not result in social harm were outside the purview of civil courts.[ With ]John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

's "sensational psychology" as a guide, which maintained that environment alone defined human behavior, many rationalists sought the roots of a criminal's behavior in his or her past environment.[

Rationalists differed as to what environmental factors gave rise to criminality. Some rationalists, including ]Cesare Beccaria

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, Marquis of Gualdrasco and Villareggio (; 15 March 173828 November 1794) was an Italian criminologist, jurist, philosopher, economist and politician, who is widely considered one of the greatest thinkers of the Age ...

, blamed criminality on the ''uncertainty'' criminal punishment, whereas earlier criminologists had linked criminal deterrence to the ''severity'' of punishment.[ In essence, Beccaria believed that where arrest, conviction, and sentencing for crime were "rapid and infallible," punishments for crime could remain moderate. Beccaria did not take issue with the substance of contemporary penal codes—e.g., whipping and the ]pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. The pillory is related to the sto ...

; rather, he took issue with their form and implementation.[

] Other rationalists, like , believed that deterrence alone could not end criminality and looked instead to the

Other rationalists, like , believed that deterrence alone could not end criminality and looked instead to the social environment

The social environment, social context, sociocultural context or milieu refers to the immediate physical and social setting in which people live or in which something happens or develops. It includes the culture that the individual was educate ...

as the ultimate source of crime.[Hirsch, 22.] Bentham's conception of criminality led him to concur with philanthropist reformers on the need for rehabilitation of offenders.[ But, unlike the philanthropists, Bentham and like-minded rationalists believed the true goal of rehabilitation was to show convicts the logical "inexpedience" of crime, not their estrangement from religion.][ For these rationalists, society was the source of and the solution to crime.

Ultimately, hard labor became the preferred rationalist therapy.][Hirsch, 23.] Bentham eventually adopted this approach, and his well-known 1791 design for the Panopticon

The panopticon is a type of institutional building and a system of control designed by the English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century. The concept of the design is to allow all prisoners of an institution to be o ...

prison called for inmates to labor in solitary cells for the course of their imprisonment.[ Another rationalist, William Eden, collaborated with ]John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007, holding office as leader of the Liberal Party. His eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the ...

and Justice William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family ...

in drafting the Penitentiary Act

The Penitentiary Act (19 Geo. III, c.74) was a British Act of Parliament passed in 1779 which introduced a policy of state prisons for the first time. The Act was drafted by the prison reformer John Howard and the jurist William Blackstone and rec ...

of 1779, which called for a penal regime of hard labor.[

According to social and legal historian Adam J. Hirsch, the rationalists had only a secondary impact on United States penal practices.][ But their ideas—whether consciously adopted by United States prison reformers or not—resonate in various United States penal initiatives to the present day.][

]

Historical development of United States prison systems

Although convicts played a significant role in British settlement of North America, according to legal historian Adam J. Hirsch " e wholesale incarceration of criminals is in truth a comparatively recent episode in the history of Anglo-American jurisprudence."[ Imprisonment facilities were present from the earliest English settlement of North America, but the fundamental purpose of these facilities changed in the early years of United States legal history as a result of a geographically widespread "penitentiary" movement. The form and function of prison systems in the United States has continued to change as a result of political and scientific developments, as well as notable reform movements during the ]Jacksonian Era

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21, and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, A ...

, Reconstruction Era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

, Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

, and the 1970s. But the status of penal incarceration as the primary mechanism for criminal punishment has remained the same since its first emergence in the wake of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

.

Early settlement, convict transportation, and the prisoner trade

Prisoners and prisons appeared in North America simultaneous to the arrival of European settlers. Among the ninety or so men who sailed with the explorer known as

Prisoners and prisons appeared in North America simultaneous to the arrival of European settlers. Among the ninety or so men who sailed with the explorer known as Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

were a young black man abducted from the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

and at least four convicts. By 1570, Spanish soldiers in St. Augustine, Florida

St. Augustine ( ; es, San Agustín ) is a city in the Southeastern United States and the county seat of St. Johns County on the Atlantic coast of northeastern Florida. Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorers, it is the oldest continuously inhabi ...

, had built the first substantial prison in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

.[Christianson, 6.] As other European nations began to compete with Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

for land and wealth in the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

, they too turned to convicts to fill out the crews on their ships.[

According to social historian Marie Gottschalk, convicts were "indispensable" to English settlement efforts in what is now the United States. In the late sixteenth century, ]Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt (; 1553 – 23 November 1616) was an English writer. He is known for promoting the English colonization of North America through his works, notably ''Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America'' (1582) and ''The Pri ...

called for the large-scale conscription of criminals to settle the New World for England.[ But official action on Haklyut's proposal lagged until 1606, when the English crown escalated its ]colonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

efforts.[

Sir John Popham's colonial venture in present-day ]Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

was stocked, a contemporary critic complained, "out of all the gaols ailsof England."[Christianson, 7.] The Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the object of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day Mai ...

, the corporate entity responsible for settling Jamestown, authorized its colonists to seize Native American children wherever they could "for conversion ... to the knowledge and worship of the true God and their redeemer, Christ Jesus."[ The colonists themselves lived, in effect, as prisoners of the Company's governor and his agents.][ Men caught trying to escape were tortured to death; seamstresses who erred in their sewing were subject to whipping.][ One Richard Barnes, accused of uttering "base and detracting words" against the governor, was ordered to be "disarmed and have his arms broken and his tongue bored through with an awl" before being banished from the settlement entirely.][

When control of the Virginia Company passed to Sir Edwin Sandys in 1618, efforts to bring large numbers of settlers to the New World against their will gained traction alongside less coercive measures like ]indentured servitude

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an " indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayme ...

.[Christianson, 9.] Vagrancy statutes began to provide for penal transportation

Penal transportation or transportation was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies became thei ...

to the American colonies as an alternative to capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

in this period, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

.[ At the same time, the legal definition of "vagrancy" was greatly expanded.][

] Soon, a royal commissions endorsed the notion that any felon—except those convicted of murder, witchcraft, burglary, or rape—could legally be transported to Virginia or the West Indies to work as a plantation servant. Sandys also proposed sending maids to Jamestown as "breeders," whose costs of passage could be paid for by the planters who took them on as "wives."

Soon, a royal commissions endorsed the notion that any felon—except those convicted of murder, witchcraft, burglary, or rape—could legally be transported to Virginia or the West Indies to work as a plantation servant. Sandys also proposed sending maids to Jamestown as "breeders," whose costs of passage could be paid for by the planters who took them on as "wives."[Christianson, 11.] Soon, over sixty such women had made the passage to Virginia, and more followed.[ ]King James I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

's royal administration also sent "vagrant" children to the New World as servants.[ a letter in the ]Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the object of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day Mai ...

's records suggests that as many as 1,500 children were sent to Virginia between 1619 and 1627. By 1619, African prisoners were brought to Jamestown and sold as slaves as well, marking England's entry into the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

.[Christianson, 13.]

The infusion of kidnapped children, maids, convicts, and Africans to Virginia during the early part of the seventeenth century inaugurated a pattern that would continue for nearly two centuries.[ By 1650, the majority of British emigrants to colonial North America went as "prisoners" of one sort or another—whether as indentured servants, convict laborers, or slaves.][Christianson, 15.]

The prisoner trade became the "moving force" of English colonial policy after the Restoration—i.e., from the summer of 1660 onward—according to[ By 1680, the Reverend Morgan Godwyn estimated that almost 10,000 persons were spirited away to the Americas annually by the English crown.][

]Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

accelerated the prisoner trade in the eighteenth century. Under England's Bloody Code

The "Bloody Code" was a series of laws in England, Wales and Ireland in the 18th and early 19th centuries which mandated the death penalty for a wide range of crimes. It was not referred to as such in its own time, but the name was given later ...

, a large portion of the realm's convicted criminal population faced the death penalty. But pardons were common. During the eighteenth century, the majority of those sentenced to die in English courts were pardoned—often in exchange for voluntary transport to the colonies. In 1717, Parliament empowered the English courts to directly sentence offenders to transportation, and by 1769 transportation was the leading punishment for serious crime in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

. Over two-thirds of those sentenced during sessions of the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

in 1769 were transported.[Christianson, 24.] The list of "serious crimes" warranting transportation continued to expand throughout the eighteenth century, as it had during the seventeenth.[ Historian A. Roger Ekirch estimates that as many as one-quarter of all British emigrants to colonial America during the 1700s were convicts. In the 1720s, ]James Oglethorpe

James Edward Oglethorpe (22 December 1696 – 30 June 1785) was a British soldier, Member of Parliament, and philanthropist, as well as the founder of the colony of Georgia in what was then British America. As a social reformer, he hoped to r ...

settled the colony of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

almost entirely with convict settlers.[

The typical transported convict during the 1700s was brought to the North American colonies on board a "prison ship."][Christianson, 33.] Upon arrival, the convict's keepers would bathe and clothe him or her (and, in extreme cases, provide a fresh wig) in preparation for a convict auction.[ Newspapers advertised the arrival of a convict cargo in advance, and buyers would come at an appointed hour to purchase convicts off the auction block.][

] Prisons played an essential role in the convict trade. Some ancient prisons, like the Fleet and

Prisons played an essential role in the convict trade. Some ancient prisons, like the Fleet and Newgate

Newgate was one of the historic seven gates of the London Wall around the City of London and one of the six which date back to Roman times. Newgate lay on the west side of the wall and the road issuing from it headed over the River Fleet to Mid ...

, still remained in use during the high period of the American prisoner trade in the eighteenth century. But more typically an old house, medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

dungeon

A dungeon is a room or cell in which prisoners are held, especially underground. Dungeons are generally associated with medieval castles, though their association with torture probably belongs more to the Renaissance period. An oubliette (from ...

space, or private structure would act as a holding pen for those bound for American plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

s or the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

(under impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

).[Christianson, 18.] Operating clandestine prisons in major port cities for detainees whose transportation to the New World was not strictly legal, became a lucrative trade on both sides of the Atlantic in this period.[ Unlike contemporary prisons, those associated with the convict trade served a custodial, not a punitive function.

Many colonists in British North America resented ]convict transportation

Penal transportation or transportation was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies became their d ...

. As early as 1683, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

's colonial legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known ...

attempted to bar felons

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "félonie") to describe an offense that resul ...

from being introduced within its borders. Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

called convict transportation "an insult and contempt, the cruellest, that ever one people offered to another." Franklin suggested that the colonies send some of North America's rattlesnake

Rattlesnakes are venomous snakes that form the genera ''Crotalus'' and ''Sistrurus'' of the subfamily Crotalinae (the pit vipers). All rattlesnakes are vipers. Rattlesnakes are predators that live in a wide array of habitats, hunting small an ...

s to England, to be set loose in its finest parks, in revenge. But transportation of convicts to England's North American colonies continued until the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, and many officials in England saw it as a humane necessity in light of the harshness of the penal code and contemporary conditions in English jails.[Christianson, 51.] Dr. Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

, upon hearing that British authorities might bow to continuing agitation in the American colonies against transportation, reportedly told James Boswell

James Boswell, 9th Laird of Auchinleck (; 29 October 1740 ( N.S.) – 19 May 1795), was a Scottish biographer, diarist, and lawyer, born in Edinburgh. He is best known for his biography of his friend and older contemporary the English writer ...

: "Why they are a race of convicts, and ought to be thankful for anything we allow them short of hanging!"[

When the ]American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

ended the prisoner trade to North America, the abrupt halt threw Britain's penal system into disarray, as prisons and jails quickly filled with the many convicts who previously would have moved on to the colonies.[Christianson, 75; ''see also'' Meranze, 141; Hirsch, 19.] Conditions steadily worsened.[ It was during this crisis period in the English criminal justice system that penal reformer ]John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007, holding office as leader of the Liberal Party. His eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the ...

began his work.[ Howard's comprehensive study of British penal practice, ''The State of the Prisons in England and Wales'', was first published in 1777—one year after the start of the ]Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

.

Colonial criminal punishments, jails, and workhouses

The jail was built in 1690 by order of Plimouth and Massachusetts Bay Colony Courts. Used as a jail from 1690–1820; at one time moved and attached to the Constable's home. The 'Old Gaol' was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

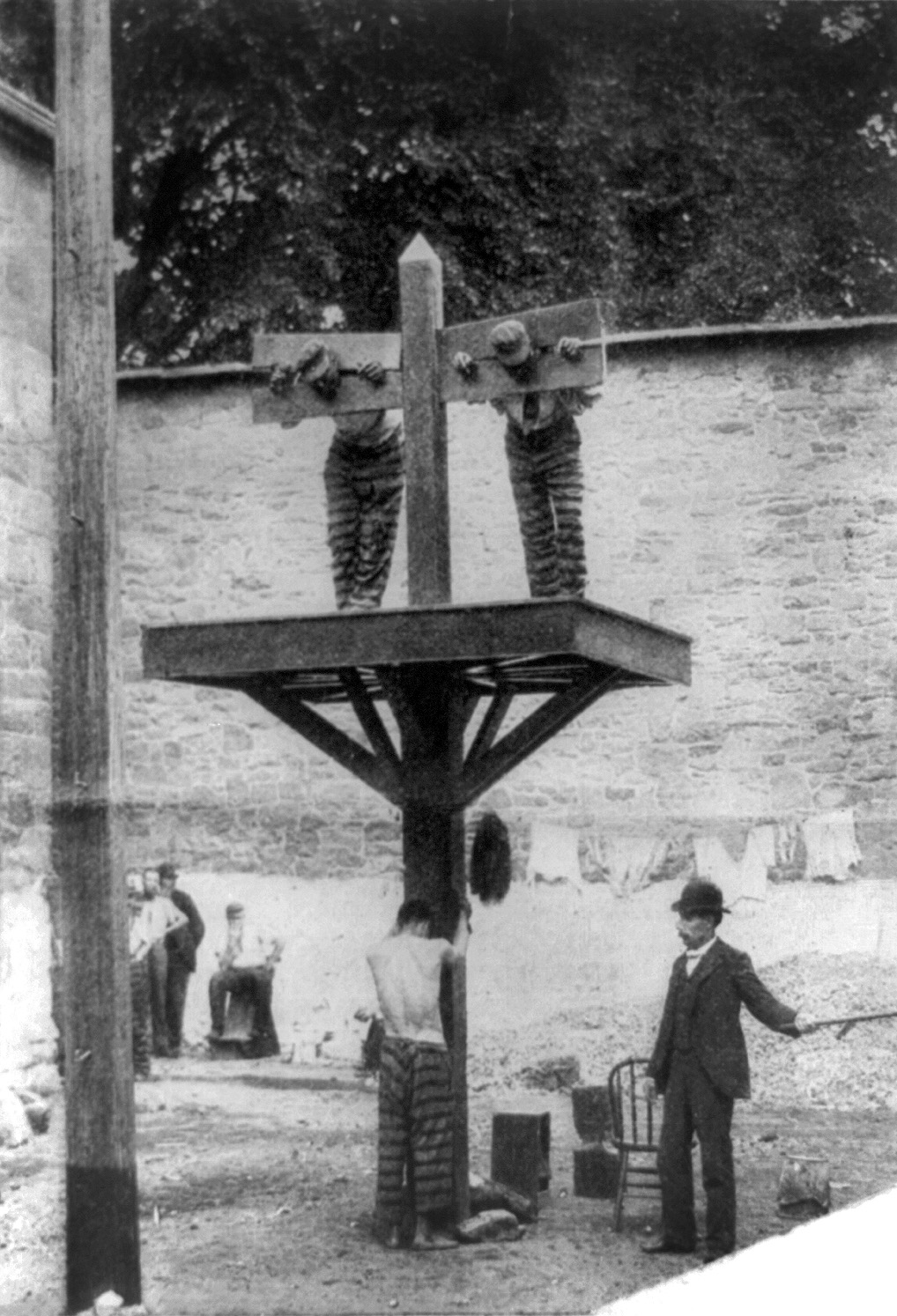

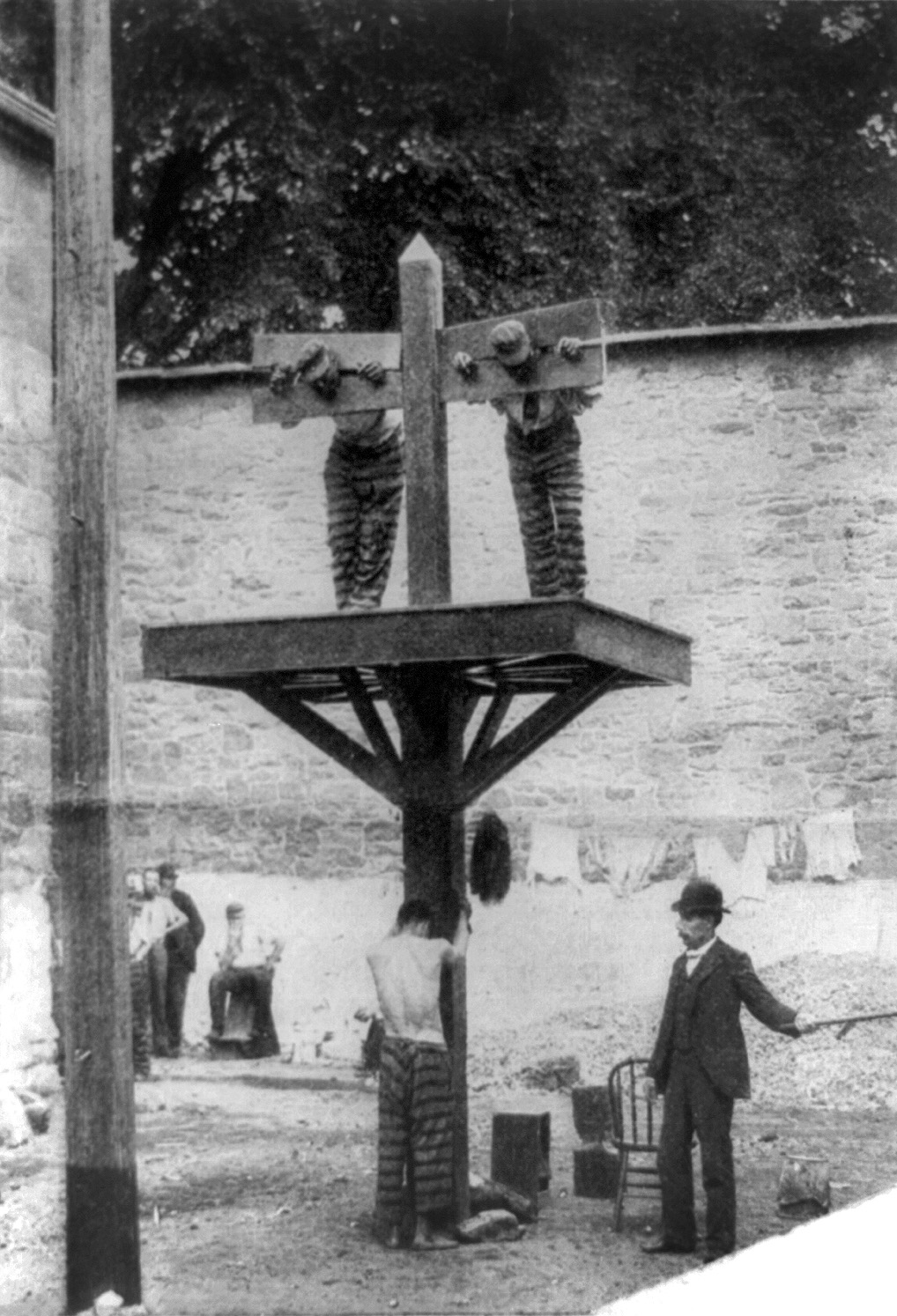

Although jails were an early fixture of colonial North American communities, they generally did not serve as places of incarceration as a form of criminal punishment. Instead, the main role of the colonial American jail was as a non-punitive detention facility for pre-trial and pre-sentence criminal defendants, as well as imprisoned debtors. The most common penal sanctions of the day were

The jail was built in 1690 by order of Plimouth and Massachusetts Bay Colony Courts. Used as a jail from 1690–1820; at one time moved and attached to the Constable's home. The 'Old Gaol' was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

Although jails were an early fixture of colonial North American communities, they generally did not serve as places of incarceration as a form of criminal punishment. Instead, the main role of the colonial American jail was as a non-punitive detention facility for pre-trial and pre-sentence criminal defendants, as well as imprisoned debtors. The most common penal sanctions of the day were fines Fines may refer to:

* Fines, Andalusia, Spanish municipality

* Fine (penalty)

* Fine, a dated term for a premium on a lease of land, a large sum the tenant pays to commute (lessen) the rent throughout the term

*Fines, ore or other products with a s ...

, whipping, and community-oriented punishments like the stocks.

Jails were among the earliest public structures built in colonial British North America. The 1629 colonial charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as th ...

, for example, granted the shareholder

A shareholder (in the United States often referred to as stockholder) of a corporation is an individual or legal entity (such as another corporation, a body politic, a trust or partnership) that is registered by the corporation as the legal o ...

s behind the venture the right to establish laws for their settlement "not contrarie to the lawes of our realm in England" and to administer "lawfull correction" to violators, and Massachusetts established a house of correction for punishing criminals by 1635. Colonial Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

built two houses of correction starting in 1682, and Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the ...

established one in 1727. By the eighteenth century, every county in the North American colonies had a jail.

Colonial American jails were not the "ordinary mechanism of correction" for criminal offenders, according to social historian David Rothman. Criminal incarceration as a penal sanction was "plainly a second choice," either a supplement to or a substitute for traditional criminal punishments of the day, in the words of historian Adam J. Hirsch.

Colonial American jails were not the "ordinary mechanism of correction" for criminal offenders, according to social historian David Rothman. Criminal incarceration as a penal sanction was "plainly a second choice," either a supplement to or a substitute for traditional criminal punishments of the day, in the words of historian Adam J. Hirsch.[Hirsch, 8.] Eighteenth-century criminal codes provided for a far wider range of criminal punishments than contemporary state and federal criminal laws in the United States. Fines Fines may refer to:

* Fines, Andalusia, Spanish municipality

* Fine (penalty)

* Fine, a dated term for a premium on a lease of land, a large sum the tenant pays to commute (lessen) the rent throughout the term

*Fines, ore or other products with a s ...

, whippings, the stocks

Stocks are feet restraining devices that were used as a form of corporal punishment and public humiliation. The use of stocks is seen as early as Ancient Greece, where they are described as being in use in Solon's law code. The law describing ...

, the pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. The pillory is related to the sto ...

, the public cage, banishment

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples su ...

, capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

at the gallows

A gallows (or scaffold) is a frame or elevated beam, typically wooden, from which objects can be suspended (i.e., hung) or "weighed". Gallows were thus widely used to suspend public weighing scales for large and heavy objects such as sacks ...

, penal servitude in private homes—all of these punishments came before imprisonment in British colonial America.

The most common sentence of the colonial era was a fine or a whipping, but the stocks were another common punishment—so much so that most colonies, like Virginia in 1662, hastened to build these before either the courthouse or the jail. The theocratic

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fr ...

communities of Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

imposed faith-based punishments like the admonition

Admonition (or "being admonished") is the lightest punishment under Scots law. It occurs when an offender who has been found guilty or who has pleaded guilty, is not given a fine, but instead receives a lesser penalty in the form of a verbal w ...

—a formal censure, apology, and pronouncement of criminal sentence (generally reduced or suspended), performed in front of the church-going community. Sentences to the colonial American workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

—when they were actually imposed on defendants—rarely exceeded three months, and sometimes spanned just a single day.[

Colonial jails served a variety of public functions other than penal imprisonment. Civil imprisonment for debt was one of these,][Hirsch, 7.] but colonial jails also served as warehouses for prisoners-of-war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

and political prisoners

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although nu ...

(especially during the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

).[ They were also an integral part of the ]transportation

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land ( rail and road), water, cable, pipelin ...

and slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

systems—not only as warehouses for convicts and slaves being put up for auction, but also as a means of disciplining both kinds of servants.

The colonial jail's primary

The colonial jail's primary criminal law

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It prescribes conduct perceived as threatening, harmful, or otherwise endangering to the property, health, safety, and moral welfare of people inclusive of one's self. Most criminal law ...

function was as a pre-trial and pre-sentence detention facility. Generally, only the poorest or most despised defendants found their way into the jails of colonial North America, since colonial judges rarely denied requests for bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

. The only penal function of significance that colonial jails served was for contempt—but this was a coercive technique designed to protect the power of the courts, not a penal sanction in its own right.[

The colonial jail differed from today's United States prisons not only in its purpose, but in its structure. Many were no more than a cage or closet. Colonial jailers ran their institutions on a "familial" model and resided in an apartment attached to the jail, sometimes with a family of their own. The colonial jail's design resembled an ordinary domestic residence, and inmates essentially rented their bed and paid the jailer for necessities.

Before the close of the ]American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, few statutes or regulations defined the colonial jailers' duty of care or other responsibilities. Upkeep was often haphazard, and escapes quite common. Few official efforts were made to maintain inmates' health or see to their other basic needs.

Post-Revolutionary penal reform and the beginnings of United States prison systems

The first major prison reform movement in the United States came after the

The first major prison reform movement in the United States came after the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, at the start of the nineteenth century. According to historians Adam J. Hirsch and David Rothman, the reform of this period was shaped less by intellectual movements in England than by a general clamor for action in a time of population growth and increasing social mobility, which prompted a critical reappraisal and revision of penal corrective techniques.[Rothman, ''Discovery'', 57; Hirsch, 32, 114.] To address these changes, post-colonial legislators and reformers began to stress the need for a system of hard labor to replace ineffectual corporal and traditional punishments. Ultimately, these early efforts yielded the United States' first penitentiary systems.[Hirsch, 39.] The century was marked by rapid population growth throughout the colonies—a result of lower mortality rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of d ...

s and increasing (though small at first) rates of immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, ...

.[Rothman, ''Discovery'', 58.] The population of Massachusetts almost doubled in this period, while it tripled in Pennsylvania and increased five-fold in New York. Demographic change in the eighteenth century coincided with shifts in the configuration of crime.

Demographic change in the eighteenth century coincided with shifts in the configuration of crime.[Hirsch, 36.] After 1700, literary evidence from a variety of sources—''e.g.'', ministers, newspapers, and judges—suggest that property crime rates rose (or, at least, were perceived to).[ Conviction rates appear to have risen during the last half of the eighteenth century, rapidly so in the 1770s and afterward and especially in urban areas.][ Contemporary accounts also suggest widespread transiency among former criminals.][

Communities began to think about their town as something less than the sum of all its inhabitants during this period, and the notion of a distinct criminal class began to materialize.][ In the Philadelphia of the 1780s, for example, city authorities worried about the proliferation of taverns on the outskirts of the city, "sites of an alternative, interracial, lower-class culture" that was, in the words of one observer, "the very root of vice." In Boston, a higher urban crime rate led to the creation of a specialized, urban court in 1800.

The efficacy of traditional, community-based punishments waned during the eighteenth century. Penal servitude, a mainstay of British and colonial American criminal justice, became nearly extinct during the seventeenth century, at the same time that Northern states, beginning with ]Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provin ...

in 1777, began to abolish slavery. Fines and bonds for good behavior—one of the most common criminal sentences of the colonial era—were nearly impossible to enforce among the transient poor. As the former American colonists expanded their political loyalty beyond the parochial to their new state governments, promoting a broader sense of the public welfare, banishment (or " warning out") also seemed inappropriate, since it merely passed criminals onto a neighboring community. Public shaming punishments like the pillory had always been inherently unstable methods of enforcing the public order, since they depended in large part on the participation of the accused and the public. As the eighteenth century matured, and a social distance between the criminal and the community became more manifest, mutual antipathy (rather than community compassion and offender penitence) became more common at public executions and other punishments.war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

interrupted these efforts, they were renewed afterward. A "climate change" in post-Revolutionary politics, in the words of historian Adam J. Hirsch, made colonial legislatures open to legal change of all sorts after the Revolution, as they retooled their constitutions and criminal codes to reflect their separation from England. The Anglophobic politics of the day bolstered efforts to do away with punishments inherited from English legal practice.

Reformers in the United States also began to discuss the effect of criminal punishment itself on criminality in the post-revolutionary period, and at least some concluded that the barbarism of colonial-era punishments, inherited from English penal practice, did more harm than good. "The mild voice of reason and humanity," wrote New York penal reformer

Reformers in the United States also began to discuss the effect of criminal punishment itself on criminality in the post-revolutionary period, and at least some concluded that the barbarism of colonial-era punishments, inherited from English penal practice, did more harm than good. "The mild voice of reason and humanity," wrote New York penal reformer Thomas Eddy

Thomas Eddy (September 5, 1758 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania - September 16, 1827 New York City) was an American merchant, banker, philanthropist and politician from New York.

Early life

He was the son of Irish Quaker immigrants who had come to Ame ...

in 1801, "reached not the thrones of princes or the halls of legislators."[Qtd. in Rothman, ''Discovery'', 58] "The mother country had stifled the colonists' benevolent instincts," according to Eddy, "compelling them to emulate the crude customs of the old world. The result was the predominance of archaic and punitive laws that only served to perpetuate crime."[ Attorney William Bradford made an argument similar to Eddy's in a 1793 treatise.]North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, and Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

had amended its criminal code to provide for incarceration (primarily at hard labor) as the primary punishment for all but the most serious offenses.[Rothman, ''Discovery'', 61.] Provincial laws in Massachusetts began to prescribe short terms in the workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

for deterrence throughout the eighteenth century and, by mid-century, the first statutes mandating long-term hard labor in the workhouse as a penal sanction appeared. In New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, a 1785 bill, restricted in effect to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, authorized municipal officials to substitute up to six months' hard labor in the workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

in all cases where prior law had mandated corporal punishment.[Hirsch, 42.] In 1796, an additional bill expanded this program to the entire state of New York.[ ]Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

established a hard labor law in 1786.[ Hard-labor programs expanded to ]New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

in 1797, to Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

in 1796, to Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

in 1798, and to Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provin ...

, New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, and Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

in 1800.

This move toward imprisonment did not translate to an immediate break from traditional forms of punishment. Many new criminal provisions merely expanded the discretion of judges to choose from among various punishments, including imprisonment. The 1785 amendments to Massachusetts' arson statute, for instance, expanded the available punishments for setting fire to a non-dwelling from whipping to hard labor, imprisonment in jail, the pillory, whipping, fining, or any or all of those punishments in combination. Massachusetts judges wielded this new-found discretion in various ways for twenty years, before fines, incarceration, or the death penalty became the sole available sanctions under the state's penal code. Other states—''e.g.'', New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, and Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the ...

—also lagged in their shift toward incarceration.[Hirsch, 59.]

Prison construction kept pace with post-revolutionary legal change. All states that revised their criminal codes to provide for incarceration also constructed new state prisons.[ But the focus of penal reformers in the post-revolutionary years remained largely external to the institutions they built, according to David Rothman.][Rothman, ''Discovery'', 62.] For reformers of the day, Rothman claims, the fact of imprisonment—not the institution's internal routine and its effect on the offender—was of primary concern.[ Incarceration seemed more humane than traditional punishments like hanging and whipping, and it theoretically matched punishment more specifically to the crime.][ But it would take another period of reform, in the ]Jacksonian Era

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21, and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, A ...

, for state prison initiatives to take the shape of actual justice institutions.[

]

Jacksonian and Antebellum era

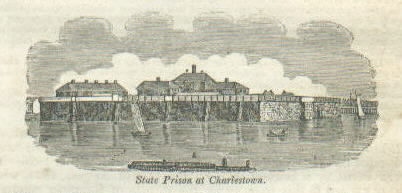

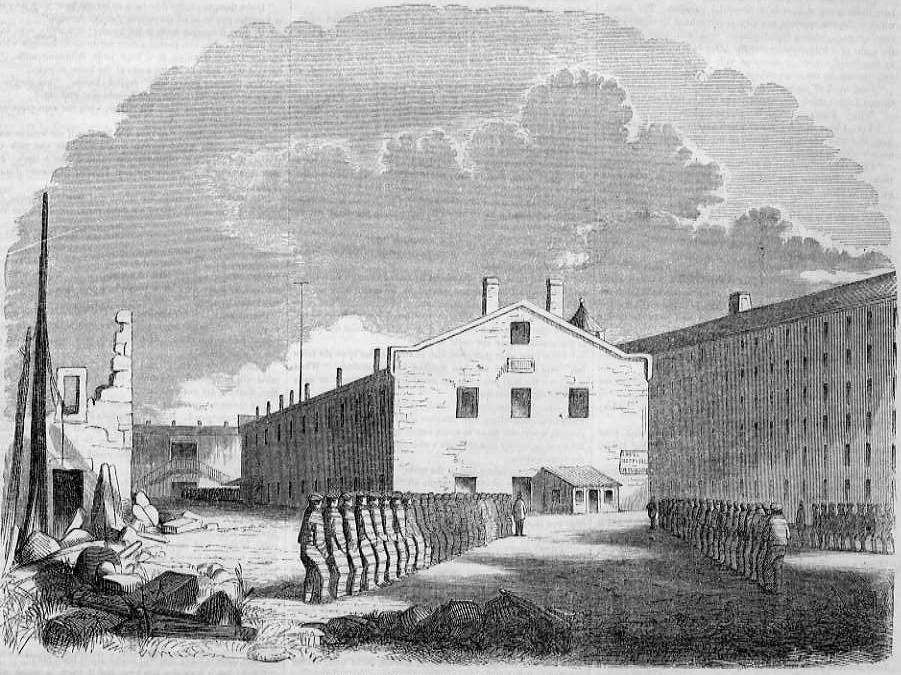

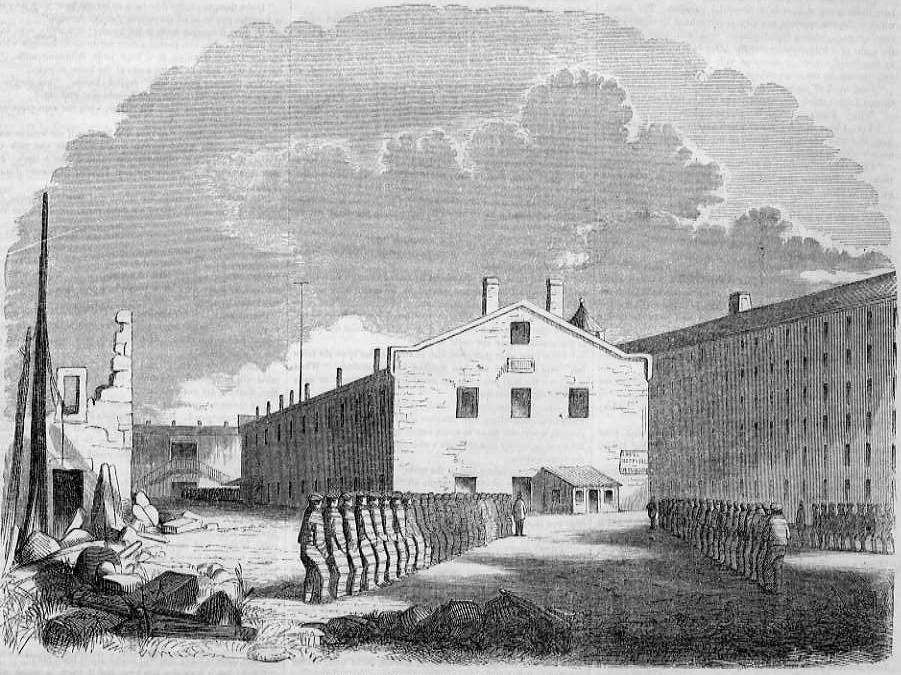

By 1800, eleven of the then-sixteen United States—''i.e.'',

By 1800, eleven of the then-sixteen United States—''i.e.'', Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

, Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provin ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

, New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, and Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

—had in place some form of penal incarceration. But the primary focus of contemporary criminology remained on the legal system, according to historian David Rothman, not the institutions in which convicts served their sentences.[ This changed during the Jacksonian Era, as contemporary notions of criminality continued to shift.

Starting in the 1820s, a new institution, the "penitentiary", gradually became the focal point of criminal justice in the United States.][Rothman, ''Discovery'', 79.] At the same time, other novel institutions—the asylum

Asylum may refer to:

Types of asylum

* Asylum (antiquity), places of refuge in ancient Greece and Rome

* Benevolent Asylum, a 19th-century Australian institution for housing the destitute

* Cities of Refuge, places of refuge in ancient Judea

...

and the almshouse