Sierra Leone first became inhabited by

indigenous African peoples at least 2,500 years ago. The

Limba were the first tribe known to inhabit Sierra Leone. The dense tropical rainforest partially isolated the region from other

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

n cultures, and it became a refuge for peoples escaping violence and

jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with Go ...

s.

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierra ...

was named by Portuguese explorer

Pedro de Sintra

Pedro de Sintra, also known as Pêro de Sintra, Pedro da Cintra or Pedro da Sintra, was a Portuguese explorer. He was among the first Europeans to explore the West African coast. Around 1462 his expedition reached what is now Sierra Leone and named ...

, who mapped the region in 1462. The

Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and p ...

estuary provided a good natural harbour for ships to shelter and replenish drinking water, and gained more international attention as coastal and trans-Atlantic trade supplanted

trans-Saharan trade

Trans-Saharan trade requires travel across the Sahara between sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa. While existing from prehistoric times, the peak of trade extended from the 8th century until the early 17th century.

The Sahara once had a very d ...

.

In the mid-16th century, the

Mane people

The Manes (so called by the Portuguese) or Mani or Manneh were invaders who attacked the western coast of Africa from the east, beginning during the first half of the sixteenth century. Walter Rodney has suggested that "the Mane invaders of Sierra ...

invaded, subjugated nearly all of the indigenous coastal peoples, and militarised

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierra ...

. The Mane soon blended with the local populations and the various chiefdoms and kingdoms remained in a continual state of conflict, with many captives sold to European slave-traders. The

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

had a significant impact on Sierra Leone, as this trade flourished in the 17th and 18th centuries, and later as a centre of anti-slavery efforts when the trade was abolished in 1807. British abolitionists had organised a colony for

Black Loyalists

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the Cro ...

at Freetown, and this became the capital of

British West Africa

British West Africa was the collective name for British colonies in West Africa during the colonial period, either in the general geographical sense or the formal colonial administrative entity. British West Africa as a colonial entity was orig ...

. A naval squadron was based there to intercept slave ships, and the colony quickly grew as

Liberated Africans were released, joined by

Afro-Caribbean

Afro-Caribbean people or African Caribbean are Caribbean people who trace their full or partial ancestry to Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the modern African-Caribbeans descend from Africans taken as slaves to colonial Caribbean via the ...

and African soldiers who had fought for Britain in the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. The descendants of the black settlers were collectively referred to as the

Creoles or Krios.

During the colonial era, the British and Creoles increased their control over the surrounding area, securing peace so that commerce would not be interrupted, suppressing slave-trading and inter-chiefdom war. In 1895, Britain drew borders for Sierra Leone which they declared to be their

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

, leading to armed resistance and the

Hut Tax War of 1898

The Hut Tax War of 1898 was a resistance in the newly annexed Protectorate of Sierra Leone to a new tax imposed by the colonial governor. The British had established the Protectorate to demonstrate their dominion over the territory to other Europ ...

. Thereafter, there was dissent and reforms as the Creoles sought political rights, trade unions formed against colonial employers, and peasants sought greater justice from their chiefs.

Sierra Leone has played a significant part in modern African political liberty and nationalism. In the 1950s, a new constitution united the

Crown Colony and Protectorate, which had previously been governed separately. Sierra Leone gained independence from the United Kingdom on 27 April 1961 and became a member of the

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

. Ethnic and linguistic divisions remain an obstacle to national unity, with the

Mende,

Temne and Creoles as rival power blocs. Roughly half of the years since independence have been marked by autocratic governments or

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

.

Early history

Archaeological finds show that Sierra Leone has been inhabited continuously for at least 2,500 years,

populated by successive movements of peoples from other parts of Africa.

The use of iron was introduced to Sierra Leone by the 9th century, and by the end of the 10th century agriculture was being practiced by coastal tribes.

Sierra Leone's dense tropical rainforest partially isolated the land from other African cultures and from the spread of

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

. This made it a refuge for people escaping subjugation by the

Sahelian kingdoms

The Sahelian kingdoms were a series of centralized kingdoms or empires that were centered on the Sahel, the area of grasslands south of the Sahara, from the 8th century to the 19th. The wealth of the states came from controlling the trade routes ...

, violence and

jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with Go ...

s.

European contacts with Sierra Leone were among the first in West Africa. In 1462, Portuguese explorer

Pedro de Sintra

Pedro de Sintra, also known as Pêro de Sintra, Pedro da Cintra or Pedro da Sintra, was a Portuguese explorer. He was among the first Europeans to explore the West African coast. Around 1462 his expedition reached what is now Sierra Leone and named ...

mapped the hills surrounding what is now Freetown Harbour, naming the oddly shaped formation ''Serra Lyoa'' (Lioness Mountain).

At this time the country was inhabited by numerous politically independent native groups. Several different languages were spoken, but there was similarity of religion. In the coastal rainforest belt there were

Bulom-speakers between the

Sherbro and

Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and p ...

estuaries,

Loko-speakers north of the Freetown estuary to the

Little Scarcies River

The Little Scarcies River is a river in west Africa that begins in Guinea and flows into Sierra Leone, after which it empties into the Atlantic Ocean. It is surrounded by extensive marshlands. The river is also known as the Kaba River.

The Great ...

,

Temne-speakers found at the mouth of the

Scarcies River

The Little Scarcies River is a river in west Africa that begins in Guinea and flows into Sierra Leone, after which it empties into the Atlantic Ocean. It is surrounded by extensive marshlands. The river is also known as the Kaba River.

The Gre ...

, and

Limba-speakers farther up the Scarcies. In the hilly savannah north of all of these lands were the

Susu and

Fula

Fula may refer to:

*Fula people (or Fulani, Fulɓe)

*Fula language (or Pulaar, Fulfulde, Fulani)

**The Fula variety known as the Pulaar language

**The Fula variety known as the Pular language

**The Fula variety known as Maasina Fulfulde

*Al-Fula ...

tribes. The Susu traded regularly with the coastal peoples along river valley routes, bringing salt, clothes woven by the Fula, iron work, and gold.

European contact (15th century)

Portuguese ships began visiting Sierra Leone regularly in the late 15th century, and for a while they maintained a fort on the north shore of the

Freetown estuary. This estuary is one of the largest natural deep-water harbours in the world, and one of the few good harbours on West Africa's surf-battered "Windward Shore" (Liberia to Senegal). It soon became a favourite destination of European mariners, to shelter and replenish drinking water. Some of the Portuguese sailors stayed permanently, trading and intermarrying with the local people.

Slavery

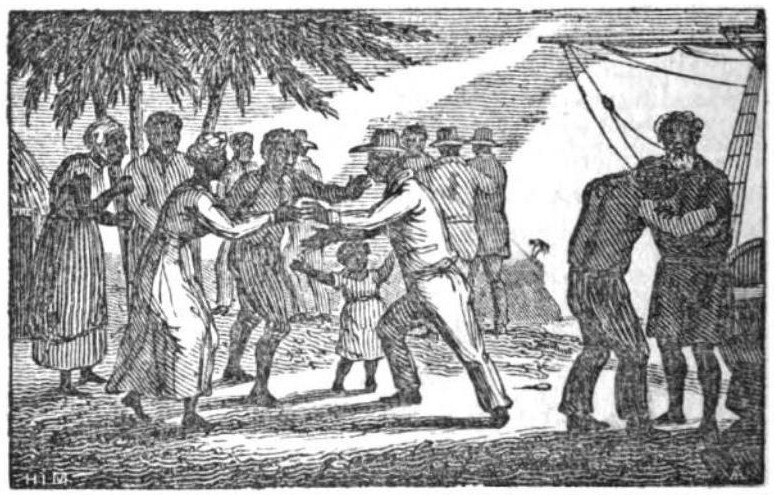

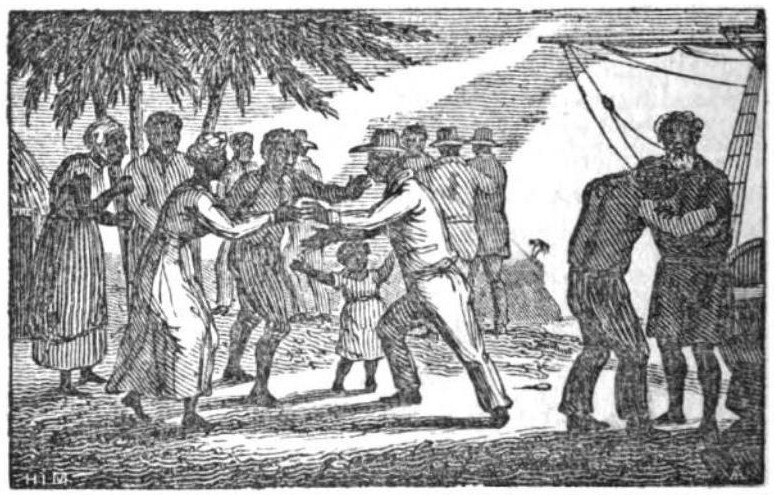

Slavery, and in particular the

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

, had a great effect on the region—socially, economically and politically—from the late 15th to the mid-19th centuries.

There had been lucrative

trans-Saharan trade

Trans-Saharan trade requires travel across the Sahara between sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa. While existing from prehistoric times, the peak of trade extended from the 8th century until the early 17th century.

The Sahara once had a very d ...

of slaves in West Africa from the 6th century. At its peak (c. 1350) the

Mali Empire

The Mali Empire ( Manding: ''Mandé''Ki-Zerbo, Joseph: ''UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century'', p. 57. University of California Press, 1997. or Manden; ar, مالي, Māl ...

surrounded the region of modern-day Sierra Leone and Liberia, though the slave trade may not have significantly penetrated the coastal rainforest. The peoples who migrated into Sierra Leone from this time would have had greater contact with the indigenous slave trade, either practicing it or escaping it.

When Europeans first arrived at Sierra Leone, slavery among the African peoples of the area was believed to be rare. According to historian

Walter Rodney

Walter Anthony Rodney (23 March 1942 – 13 June 1980) was a Guyanese historian, political activist and academic. His notable works include ''How Europe Underdeveloped Africa'', first published in 1972. Rodney was assassinated in Georgetow ...

, the Portuguese mariners kept detailed reports, and so it is likely if slavery had been an important local institution that the reports would have described it. There was mention of a very particular kind of slavery in the region, which was:

According to Rodney, such a person would likely have retained some rights and had some opportunity to rise in status as time passed.

The

European colonization of the Americas

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale European colonization of the Americas took place between about 1492 and 1800. Although the Norse had explored and colonized areas of the North Atlantic, colonizing Greenland and creating a short ter ...

soon led to labor demands from nascent colonies; this led Europeans to seek a supply of slaves to transport to the Americas. Initially, European slavers launched raids on coastal villages to abduct Africans and sell them into slavery. However, they soon established economic alliances with local leaders, as many chiefs were willing to sell undesirable members of their tribe to Europeans. Other African chiefs launched raids on rival tribes in order to sell captives of such raids into slavery.

This early slaving was essentially an export business. The use of slaves as labourers by the local Africans appears to have developed only later. It may first have occurred under coastal chiefs in the late 18th century:

For example, in the late 18th century,

William Cleveland, a

Scottish leader in Africa had a large "slave town" on the mainland opposite the

Banana Islands

The Banana Islands are a group of islands that lie off the coast of Yawri Bay, south west of the Freetown Peninsula in the Western Area of Sierra Leone.

Three islands make up the Banana Islands: Dublin, Banana Islands, Dublin and Ricketts ...

, whose inhabitants "were employed in cultivating extensive rice fields, described as being some of the largest in Africa at the time".

The existence of an indigenous slave town was recorded by an English traveler in 1823. Known in the Fula language as a

''rounde'', it was connected with the Sulima Susu's capital city,

Falaba

{{Infobox settlement

, official_name = Falaba

, other_name =

, native_name =

, nickname =

, settlement_type =

, motto =

, image_skyline =

, imagesize ...

. Its inhabitants worked at farming.

Rodney has postulated two means by which slaving for export could have caused a local practice of using slaves for labour to develop:

#Not all war captives offered for sale would have been bought by the Portuguese, so their captors had to find something else to do with them. Rodney believes that executing them was rare and that they would have been used for local labour.

#There is a time lag between the time a slave is captured and the time he or she is sold. Thus there would often have been a pool of slaves awaiting sale, who would have been put to work.

There are possible additional reasons for the adoption of slavery by the locals to meet their labour requirements:

#The Europeans provided an example for imitation.

#Once slaving in any form is accepted, it may smash a moral barrier to exploitation and make its adoption in other forms seem a relatively minor matter.

#Export slaving entailed the construction of a coercive apparatus which could have been subsequently turned to other ends, such as policing a captive labour force.

#The sale of local produce (e.g., palm kernels) to Europeans opened a new sphere of economic activity. In particular, it created an increased demand for agricultural labour. Slavery was a way of mobilising an agricultural work force.

This local African slavery was much less harsh and brutal than the slavery practiced by Europeans on, for example, the plantations of the United States, the

West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

, and Brazil. The local slavery has been described by

anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms and ...

M. McCulloch:

Slaves were sometimes sent on errands outside the kingdoms of their masters and returned voluntarily.

Speaking specifically of the era around 1700, historian Christopher Fyfe relates that, "Slaves not taken in war were usually criminals. In coastal areas, at least, it was rare for anyone to be sold without being charged with a crime."

Voluntary dependence reminiscent of that described in the early Portuguese documents mentioned at the beginning of this section was still present in the 19th century. It was called

pawning; Arthur Abraham describes a typical variety:

Some observers consider the term "slave" to be more misleading than informative when describing the local practice. Abraham says that in most cases, "subject, servant, client, serf, pawn, dependent, or retainer" would be more accurate.

Domestic slavery was abolished in Sierra Leone in 1928. McCulloch reports that at that time, amongst Sierra Leone's largest present-day ethnolinguistic group, the

Mende, who then had about 560,000 people, about 15 per cent of the population (i.e., 84,000 people) were domestic slaves. He also says that "singularly little change followed the 1928 decree; a fair number of slaves returned to their original homes, but the great majority remained in the villages in which their former masters had placed them or their parents."

Export slavery remained a major business in Sierra Leone from the late 15th century to the mid-19th century. According to Fyfe, "it was estimated in 1789 that 74,000 slaves were exported annually from West Africa, about 38,000 by British firms." In 1788, a

proslavery

Proslavery is a support for slavery. It is found in the Bible, in the thought of ancient philosophers, in British writings and in American writings especially before the American Civil War but also later through 20th century. Arguments in favor o ...

European named Matthews estimated the annual total exported from between the

Nunez River

Nunez River or Rio Nuñez (Kakandé) is a river in Guinea with its source in the Futa Jallon highlands. It is also known as the Tinguilinta River, after a village along its upper course.

Geography

Lying between the to the north and the Pongo ...

(110 km north of Sierra Leone) and the Sherbro as 3,000. Participation in the

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

was gradually outlawed by various Western nations, beginning with the United States and Britain in 1808.

Mane invasions (16th century)

The

Mane invasions of the mid-16th century had a profound impact on Sierra Leone. The

Mane (also called Mani), southern members of the

Mande language group, were a warrior people, well-armed and well-organized, who lived east and possibly somewhat north of present-day Sierra Leone, occupying a belt north of the coastal peoples. Sometime in the early 16th century they began moving south.

According to some Mane who spoke to a Portuguese (Dornelas) in the late 16th century, their travels had begun as a result of the expulsion of their chief, a woman named Macario, from the imperial city in

Mandimansa, their homeland.

Their first arrival at the coast was east of Sierra Leone, at least as far away as

River Cess

River Cess is the capital city of Rivercess County, Liberia. As of the 2008 national census, the population stood at 2,578. It received its original name Cestos from Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the cou ...

and likely farther. They advanced northwest along the coast toward Sierra Leone, conquering as they went. They incorporated large numbers of the people they conquered into their army, with the result that by the time they reached Sierra Leone, the rank and file of their army consisted mostly of coastal peoples; the Mane were its commanding group.

The Mane used small

bows, which enabled Manes to reuse their enemies' arrows against them, while the enemy could make no use of the Manes' short arrows. Rodney describes the rest of their equipment thus:

The rest of their arms consisted of large shields made of reeds, long enough to give complete cover to the user, two knives, one of which was tied to the left arm, and two quivers for their arrows. Their clothes consisted of loose cotton shirts with wide necks and ample sleeves reaching down to their knees to become tights. One striking feature of their appearance was the abundance of feathers stuck in their shirts and their red caps.

By 1545, the Mane had reached

Cape Mount, near the south-eastern corner of present-day Sierra Leone. Their conquest of Sierra Leone occupied the ensuing 15 to 20 years, and resulted in the subjugation of all or nearly all of the indigenous coastal peoples—who were known collectively as the

Sapes

Sapes ( el, Σάπες) is a town and a former municipality in the Rhodope regional unit, East Macedonia and Thrace, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Maroneia-Sapes, of which it is the seat and a munici ...

—as far north as the Scarcies. The present

demographics

Demography () is the statistical study of populations, especially human beings.

Demographic analysis examines and measures the dimensions and dynamics of populations; it can cover whole societies or groups defined by criteria such as edu ...

of Sierra Leone is largely a reflection of these two decades. The degree to which the Mane supplanted the original inhabitants varied from place to place. The Temne partly withstood the Mane onslaught, and kept their language, but became ruled by a line of Mane kings. The present-day Loko and

Mende are the result of a more complete submersion of the original culture: their languages are similar, and both essentially Mande. This is likely due to conquest by the Mane invaders. In their oral tradition, the Mende describe themselves as being a mixture of two peoples: they say that their original members were hunters and fishers who populated the area sparsely in small peaceful settlements; and that their leaders came later, in a recent historical period, bringing with them the arts of war, and also building larger, more permanent villages. This history receives support from the facts that their population consists of two different racial types, and their language and culture show signs of a layering of two different forms: they have both matrilineal and patrilineal inheritance, for instance.

The Mane invasions militarised Sierra Leone. The Sapes had been un-warlike, but after the invasions, right until the late 19th century, bows,

shield

A shield is a piece of personal armour held in the hand, which may or may not be strapped to the wrist or forearm. Shields are used to intercept specific attacks, whether from close-ranged weaponry or projectiles such as arrows, by means of a ...

s, and knives of the Mane type had become ubiquitous in Sierra Leone, as had the Mane battle technique of using squadrons of archers fighting in formation, carrying the large-style shields.

Villages became fortified. The usual method of erecting two or three concentric palisades, each 4–7 metres (12–20 ft) high, created a formidable obstacle to attackers—especially since, as some of the English observed in the 19th century, the thigh-thick logs planted into the earth to make the palisades often took root at the bottom and grew foliage at the top, so that the defenders occupied a living wall of wood. A British officer who observed one of these fortifications around the time of the 1898 Hut Tax war ended his description of it thus:

He also said that English artillery could not penetrate all three fences.

At that time, at least among the Mende, "a typical settlement consisted of walled towns and open villages or towns surrounding it."

After the invasions, the Mane sub-chiefs among whom the country had been divided began fighting among themselves. This pattern of activity became permanent: even after the Mane had blended with the indigenous population—a process which was completed in the early 17th century—the various kingdoms in Sierra Leone remained in a fairly continual state of flux and conflict.

Rodney believes that a desire to take prisoners to sell as slaves to the Europeans was a major motivation to this fighting, and may even have been a driving force behind the original Mane invasions. Historian Kenneth Little concludes that the principal objective in the local wars, at least among the Mende, was plunder, not the acquisition of territory. Abraham cautions that slave trading should not be exaggerated as a cause: the Africans had their own reasons to fight, with territorial and political ambitions present. Motivations likely changed over time during the 350-year period.

The wars themselves were not exceptionally deadly. Set-piece battles were rare, and the fortified towns so strong that their capture was seldom attempted. Often the fighting consisted of small ambushes.

In these years, the political system was that each large village along with its satellite villages and settlements would be headed by a chief. The chief would have a private army of warriors. Sometimes several chiefs would group themselves into a confederacy, acknowledging one of themselves as king (or high chief). Each paid the king fealty. If one were attacked, the king would come to his aid, and the king could adjudicate local disputes.

Despite their many political divisions, the people of the country were united by cultural similarity. One component of this was the

Poro

The Poro, or Purrah or Purroh, is a men's secret society in Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, and the Ivory Coast, introduced by the Mane people. It is sometimes referred to as a hunting society and only males are admitted to its ranks. The femal ...

, an organisation common to many different kingdoms and ethnolinguistic groups. The Mende claim to be its originators, and there is nothing to contradict this. Possibly they imported it. The Temne claim to have imported it from the Sherbro or Bulom. The Dutch geographer Olfert Dapper knew of it in the 17th century. It is often described as a "secret society", and this is partly true: its rites are closed to non-members, and what happens in the "Poro bush" is never disclosed. However, its membership is very broad: among the Mende, almost all men, and some women, are initiates. In recent years it has not (as far as is known) had a central organisation: autonomous chapters exist for each chiefdom or village. However, it is said that in pre-Protectorate days there was a "Grand Poro" with cross-chiefdom powers of making war and peace. It is widely agreed that it has a restraining influence on the powers of the chiefs. Headed by a fearsome principal spirit, the ''Gbeni'', it plays a major role in the rite of passage of males from puberty to manhood. It imparts some education. In some areas, it had supervisory powers over trade, and the banking system, which used iron bars as a medium of exchange. It is not the only important society in Sierra Leone: the ''Sande'' is a female-only analogue of it; there is also the ''Humoi'' which regulates sex, and the ''Njayei'' and the ''Wunde''. The ''Kpa'' is a healing-arts collegium.

The impact of the Mane invasions on the Sapes was obviously considerable, in that they lost their political autonomy. There were other effects as well: trade with the interior was interrupted, and thousands were sold as slaves to the Europeans. In industry, a flourishing tradition in fine ivory carving was ended; however, improved ironworking techniques were introduced.

1600–1787

By the 17th century,

Portuguese colonialism in West Africa began to wane, and in Sierra Leone other European colonial powers such as the

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

and

Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

began to supplant their influence in the region. In 1628, a group of English merchants had established a

factory

A factory, manufacturing plant or a production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery, where workers manufacture items or operate machines which process each item into another. T ...

in the vicinity of

Sherbro Island

Sherbro Island is in the Atlantic Ocean, and is included within Bonthe District, Southern Province, Sierra Leone. The island is separated from the African mainland by the Sherbro River in the north and Sherbro Strait in the east. It is long a ...

, about 50 km (30 mi) south-east from present-day

Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and p ...

. In addition to ivory and slaves, the merchants at the factory also traded in

camwood

''Baphia nitida'', also known as camwood, barwood, and African sandalwood (although not a true sandalwood), is a shrubby, leguminous, hard-wooded tree from central west Africa. It is a small understorey, evergreen tree, often planted in villages ...

, a type of hard timber. The Portuguese missionary

Baltasar Barreira ministered in Sierra Leone until 1610.

Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

, and later in the century,

Capuchins, continued the mission. By 1700 it had closed, although priests occasionally visited.

In 1663, the

Royal African Company

The Royal African Company (RAC) was an English mercantile (trade, trading) company set up in 1660 by the royal House of Stuart, Stuart family and City of London merchants to trade along the West Africa, west coast of Africa. It was led by the J ...

(RAC) was granted a

royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

from

Charles II of England

Charles II (29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685) was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651, and King of England, Scotland and Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685.

Charles II was the eldest surviving child of ...

and soon established a factory on Sherbro Island and Tasso Island. During the

Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War or the Second Dutch War (4 March 1665 – 31 July 1667; nl, Tweede Engelse Oorlog "Second English War") was a conflict between Kingdom of England, England and the Dutch Republic partly for control over the seas a ...

, both factories were sacked by a

Dutch Navy

The Royal Netherlands Navy ( nl, Koninklijke Marine, links=no) is the naval force of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

During the 17th century, the navy of the Dutch Republic (1581–1795) was one of the most powerful naval forces in the world an ...

force in 1664. The factory was rebuilt, though it was sacked again by the

French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

during the

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

in 1704 and

pirates

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

in 1719 and 1720. After the Dutch raid on the RAC factory at Tasso Island, it was relocated to the nearby

Bunce Island

Bunce Island (also spelled "Bence," "Bense," or "Bance" at different periods) is an island in the Sierra Leone River. It is situated in Freetown Harbour, the estuary of the Rokel River and Port Loko Creek, about upriver from Sierra Leone's capi ...

, which was more defensible.

The Europeans made payments, called ''Cole'', for rent, tribute, and trading rights, to the king of an area. At this time the local military advantage was still on the side of the Africans, and there is a 1714 report of a king seizing RAC goods in retaliation for a breach of

protocol

Protocol may refer to:

Sociology and politics

* Protocol (politics), a formal agreement between nation states

* Protocol (diplomacy), the etiquette of diplomacy and affairs of state

* Etiquette, a code of personal behavior

Science and technolog ...

.

Local Afro-Portuguese merchants often acted as middlemen, the Europeans advancing them goods to trade to the local people, most often for ivory. In 1728, an overly aggressive RAC governor united the Africans and Afro-Portuguese in hostility to him; they burnt down the Bunce Island fort and it was not rebuilt until about 1750. During the time that the Royal African Company was operating, the firm of

Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

*Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

*Grant, Inyo County, C ...

, and

Oswald Oswald may refer to:

People

* Oswald (given name), including a list of people with the name

*Oswald (surname), including a list of people with the name

Fictional characters

*Oswald the Reeve, who tells a tale in Geoffrey Chaucer's ''The Canterbu ...

provisioned the trading stations. When the RAC abandoned Bunce Island, Sargent and his partners purchased its factory in 1748, repaired it, and used it to trade in timber.

They expanded to Batts,

Bobs,

Tasso

TASSO (Two Arm Spectrometer SOlenoid) was a particle detector at the PETRA particle accelerator at the German national laboratory DESY. The TASSO collaboration is best known for having discovered the gluon, the mediator of the strong interaction an ...

, and

Tumbu Island Tumbu refers to:

* Junior Tumbu, nickname for Lamin Conteh (b. 1976), retired Sierra Leonean international footballer

* Tumbu, a cultivar of Karuka

* Tumbu fly (''Cordylobia anthropophaga'') a species of blow fly

* Tumbu liquor, another name for pa ...

s and along the banks of the river, eventually becoming involved in the slave trade.

The French sacked it again in 1779, during the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

.

During the 17th century the

Temne ethnolinguistic group was expanding. Around 1600, a

Mani

Mani may refer to:

Geography

* Maní, Casanare, a town and municipality in Casanare Department, Colombia

* Mani, Chad, a town and sub-prefecture in Chad

* Mani, Evros, a village in northeastern Greece

* Mani, Karnataka, a village in Dakshi ...

still ruled the

Loko kingdom (the area north of

Port Loko

Port Loko is the capital of Port Loko District and since 2017 the North West Province of Sierra Leone. The city had a population of 21,961 in the 2004 census and current estimate of 44,900. Port Loko lies approximately 36 miles north-east of Fr ...

Creek) and another ruled the upper part of the south shore of the Freetown estuary. The north shore of the estuary was under a

Bullom king, and the area just east of Freetown on the peninsula was held by a non-Mani with a European name, Dom Phillip de Leon (who may have been a subordinate to his Mani neighbour). By the mid-17th century this situation had changed: Temne, not Bullom was spoken on the south shore, and ships stopping for water and firewood had to pay customs to the Temne king of

Bureh who lived at Bagos town on the point between the

Rokel River

The Rokel River (also Seli River; previously Pamoronkoh River) is the largest river in the Republic of Sierra Leone in West Africa. The river basin measures in size, with the drainage divided by the Gbengbe and Kabala hills and the Sula Mountains ...

and Port Loko Creek. (The king may have considered himself a Mani—to this day, Temne chiefs have Mani-derived titles—but his people were Temne. The Bureh king in place in 1690 was called Bai Tura, ''Bai'' being a Mani form.) The Temne had thus expanded in a wedge toward the sea at Freetown, and now separated the Bulom to the north from the Mani and other Mande-speakers to the south and east.

In this period there are several reports of women occupying high positions. The king of the south shore used to leave one of his wives to rule when he was absent, and in the Sherbro there were female chiefs. In the early 18th century, a Bulom named Seniora Maria had her own town near Cape Sierra Leone.

During the 17th century, Muslim

Fula

Fula may refer to:

*Fula people (or Fulani, Fulɓe)

*Fula language (or Pulaar, Fulfulde, Fulani)

**The Fula variety known as the Pulaar language

**The Fula variety known as the Pular language

**The Fula variety known as Maasina Fulfulde

*Al-Fula ...

from the

Upper Niger

The Niger River ( ; ) is the main river of West Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in south-eastern Guinea near the Sierra Leone border. It runs in a crescent shape through Mali, ...

and

Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 � ...

rivers moved into an area called

Fouta Djallon

Fouta Djallon ( ff, 𞤊𞤵𞥅𞤼𞤢 𞤔𞤢𞤤𞤮𞥅, Fuuta Jaloo; ar, فوتا جالون) is a Highland (geography), highland region in the center of Guinea, roughly corresponding with Middle Guinea, in West Africa.

Etymology

The Ful ...

(or Futa Jalon) in the mountainous region north of present-day Sierra Leone. They were to have an important impact on the peoples of Sierra Leone because they increased trade and also produced secondary population movements into Sierra Leone. Though the Muslim Fula first cohabited peaceably with the peoples already at Fouta Djallon, around 1725 they embarked on a war of domination, forcing the migration of many

Susu,

Yalunka, and non-Muslim Fula.

Susu—some already converted to Islam—came south into Sierra Leone, in turn displacing

Limba from north-west Sierra Leone and driving them into north-central Sierra Leone where they continue to live. Some Susu moved as far south as the Temne town of Port Loko, only 60 km (37 mi) upriver from the Atlantic. Eventually a Muslim Susu family called Senko supplanted the town's Temne rulers. Other Susu moved westward from Fouta Djallon, eventually dominating the

Baga, Bulom, and Temne north of the

Scarcies River

The Little Scarcies River is a river in west Africa that begins in Guinea and flows into Sierra Leone, after which it empties into the Atlantic Ocean. It is surrounded by extensive marshlands. The river is also known as the Kaba River.

The Gre ...

.

The Yalunka in Fouta Djallon first accepted Islam, then rejected it and were driven out. They went into north-central Sierra Leone and founded their capital at

Falaba

{{Infobox settlement

, official_name = Falaba

, other_name =

, native_name =

, nickname =

, settlement_type =

, motto =

, image_skyline =

, imagesize ...

in the mountains near the source of the Rokel. It is still an important town, about 20 km (12 mi) south of the Guinea border. Other Yalunka went somewhat farther south and settled amongst the

Koranko,

Kissi, and Limba.

Besides these groups, who were more-or-less unwilling emigrants, a considerable variety of Muslim adventurers went forth from Fouta Djallon. A Fula called Fula Mansa (''mansa'' meaning ''king'') became ruler of the

Yoni

''Yoni'' (; sometimes also ), sometimes called ''pindika'', is an abstract or aniconic representation of the Hindu goddess Shakti. It is usually shown with ''linga'' – its masculine counterpart. Together, they symbolize the merging of microc ...

country 100 km (62 mi) east of present-day Freetown. Some of his Temne subjects fled south to the

Banta

Banta Soda, or Banta, also Goli Soda or Goti Soda and Fotash Jawl, is a popular carbonated lemon or orange-flavoured soft drink sold in India since the late 19th century in a distinctly shaped iconic Codd-neck bottle. The pressure created by t ...

country between the middle reaches of the

Bagu and

Jong Jong may refer to:

Surname

*Chung (Korean surname), spelled Jong in North Korea

*Zhong (surname), spelled Jong in the Gwoyeu Romatzyh system

*Common Dutch surname "de Jong"; see

** De Jong

** De Jonge

** De Jongh

*Erica Jong (born 1942), American ...

rivers, where they became known as the Mabanta Temne.

In 1652, the first slaves from Sierra Leone were transported to

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

; they were sold to white

plantation owners in the

Sea Islands

The Sea Islands are a chain of tidal and barrier islands on the Atlantic Ocean coast of the Southeastern United States. Numbering over 100, they are located between the mouths of the Santee and St. Johns Rivers along the coast of South Carolina, ...

off the coast of the

American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

. During the 18th century, numerous slaves from Bunce Island were transported to the

Southern Colonies, due in part to the business relationship between American slave trader

Henry Laurens

Henry Laurens (December 8, 1792) was an American Founding Father, merchant, slave trader, and rice planter from South Carolina who became a political leader during the Revolutionary War. A delegate to the Second Continental Congress, Laure ...

and the

London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

-based firm of Grant, Sargent, Oswald & Company, which oversaw a thriving slave trade from Bunce Island in Sierra Leone to North America.

The transatlantic slave trade continued to transport millions of enslaved Africans, including those from Sierra Leone, across the Atlantic during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries; ultimately, roughly 12.5 million slaves where brought to the Americas this way. However, the rise of

abolitionist movements in the

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and state (polity), states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania. in the late 18th and early 19th centuries led to various European and American governments passing legislation to abolish the slave trade. The slave trade in Sierra Leone underwent a marked decline during the 19th century, though domestic slavery would persist until the 20th century.

The Province of Freedom (1787–1789)

Conception of the Province of Freedom (1787)

In 1787, a plan was established to settle some of London's "Black Poor" in Sierra Leone in what was called the "Province of Freedom". This was organised by the

Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

, founded by British abolitionist

Granville Sharp

Granville Sharp (10 November 1735 – 6 July 1813) was one of the first British campaigners for the abolition of the slave trade. He also involved himself in trying to correct other social injustices. Sharp formulated the plan to settle black ...

, which preferred it as a solution to continuing to financially support them in London. Many of the Black Poor were African Americans, who had been given their freedom after seeking refuge with the British Army during the American Revolution, but also included other West Indian, African and Asian inhabitants of London.

The Sierra Leone Resettlement Scheme was proposed by entomologist

Henry Smeathman

Henry Smeathman (1742–1786) was an English naturalist, best known for his work in entomology and colonial settlement in Sierra Leone.

In 1771 the Quaker physician John Fothergill (physician), John Fothergill, along with two other members of ...

and drew interest from humanitarians like

Granville Sharp

Granville Sharp (10 November 1735 – 6 July 1813) was one of the first British campaigners for the abolition of the slave trade. He also involved himself in trying to correct other social injustices. Sharp formulated the plan to settle black ...

saw it as a means of showing the pro-slavery lobby that black people could contribute towards the running of the new colony of Sierra Leone. Government officials soon became involved in the scheme as well, although their interest was spurred by the possibility of resettling a large group of poor citizens elsewhere. William Pitt the Younger, prime minister and leader of the Tory party, had an active interest in the Scheme, because he saw it as a means to repatriate the Black Poor to Africa, since "it was necessary they should be sent somewhere, and be no longer suffered to infest the streets of London".

Establishment, destruction and re-establishment (1789)

The area was first settled by 400 formerly enslaved Black Britons, who arrived off the coast of Sierra Leone on 15 May 1787, accompanied by some English tradesmen. They established the Province of Freedom or Granville Town on land purchased from local

Koya Temne subchief King Tom and regent

Naimbanna II Naimbanna II (1720 – 11 November 1793) was Obai (King) of the Temne people of Sierra Leone.

Naimbanna had some variants of his name, such as Nemgbana, which may refer to a place called Gbana, with the suggestion that when asked what he was called ...

, a purchase which the Europeans understood to cede the land to the new settlers "for ever". The established arrangement between Europeans and the Koya Temne did not include provisions for permanent settlement, and some historians question how well the Koya leaders understood the agreement. Half of the settlers in the new colony died within the first year. Several black settlers started working for local slave traders. The settlers that remained forcibly captured land from a local African chieftain, but he retaliated, attacking the settlement, which was reduced to a mere 64 settlers comprising 39 black men, 19 black women, and six white women. Black settlers were captured by unscrupulous traders and sold as slaves, and the remaining colonists were forced to arm themselves for their own protection. King Tom's successor King Jemmy attacked and burned the colony in 1789.

Alexander Falconbridge

Alexander Falconbridge (c. 1760–1792) was a British surgeon who took part in four voyages in slave ships between 1782 and 1787. In time he became an abolitionist and in 1788 published ''An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa''. In ...

was sent to Sierra Leone in 1791 to collect the remaining Black Poor settlers, and they re-established Granville Town (later renamed

Cline Town

Cline Town is an area in Freetown, Sierra Leone. The area is named for Emmanuel Kline, a Hausa Liberated African who bought substantial property in the area. The neighborhood is in the vicinity of Granville Town, a settlement established in 1787 a ...

) near

Fourah Bay

Fourah Bay is a neighbourhood in Freetown, Sierra Leone. It is located in the East end of Freetown.

Ethnicity and religion

Fourah Bay is an overwhelmingly Muslim majority neighborhood. The Oku people, an ethnic group predominantly of Yoruba desc ...

. Although these 1787 settlers did not establish Freetown, which was founded in 1792, the bicentennial of Freetown was celebrated in 1987.

After establishing Granville Town, disease and hostility from the indigenous people eliminated the first group of colonists and destroyed their settlement. A second Granville Town was established by 64 remaining black and white 'Old settlers' under the leadership of St. George Bay Company leader, Alexander Falconbridge and the St. George Bay Company. This settlement was different from the Freetown settlement and colony founded in 1792 by Lt.

John Clarkson

John Gibson Clarkson (July 1, 1861 – February 4, 1909) was a Major League Baseball right-handed pitcher. He played from 1882 to 1894. Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Clarkson played for the Worcester Ruby Legs (1882), Chicago White Stocking ...

and the Nova Scotian Settlers under the auspices of the Sierra Leone Company.

Freetown Colony (1792–1808)

Conception of the Freetown settlement (1791)

The basis for the Freetown Colony began in 1791 with

Thomas Peters, an African American who had served in the

Black Pioneers

The Black Company of Pioneers, also known as the Black Pioneers and Clinton's Black Pioneers, were a British Provincial military unit raised for Loyalist service during the American Revolutionary War. The Black Loyalist company was raised by Gene ...

and settled in

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

as part of the

Black Loyalist

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with the Loyalist (American Revolution), Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot (American Revolution), Pat ...

migration. Peters travelled to England in 1791 to report grievances of the Black Loyalists who had been given poor land and faced discrimination. Peters met with British

abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

and the directors of the

Sierra Leone Company. He learned of the company's plan for a new settlement at Sierra Leone. The directors were eager to allow the Nova Scotians to build a settlement there; the London-based and newly created Company had decided to create a new colony but before Peters' arrival had no colonists. Lieutenant

John Clarkson

John Gibson Clarkson (July 1, 1861 – February 4, 1909) was a Major League Baseball right-handed pitcher. He played from 1882 to 1894. Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Clarkson played for the Worcester Ruby Legs (1882), Chicago White Stocking ...

was sent to Nova Scotia to register immigrants to take to Sierra Leone for the purpose of starting a new settlement. Clarkson worked with Peters to recruit 1,196 former American slaves from free African communities around Nova Scotia such as

Birchtown

Birchtown is a community and National Historic Site in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, located near Shelburne in the Municipal District of Shelburne County. Founded in 1783, the village was the largest settlement of Black Loyalists and ...

. Most had escaped

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and

South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

plantations. Some had been born in Africa before being enslaved and taken to America.

Settlement by Nova Scotians (1792)

The settlers sailed in 15 ships from Halifax, Nova Scotia and arrived in St. George Bay between 26 February and 9 March 1792. Sixty-four settlers died en route to Sierra Leone, and even Lieutenant Clarkson was ill during the voyage. Upon reaching Sierra Leone, Clarkson and some of the Nova Scotian 'captains' "despatched on shore to clear or make roadway for their landing". The Nova Scotians were to build Freetown on the former site of the first Granville Town which had become a "jungle" since its destruction in 1789. (Though they built Freetown on Granville Town's former site, their settlement was not a rebirth of Granville Town, which had been re-established at Fourah Bay in 1791 by the remaining Old Settlers.) Clarkson told the men to clear the land until they reached a large

cotton tree. After this difficult work had been done and the land cleared, all the settlers, men and women, disembarked and marched towards the thick forest and to the cotton tree, and their preachers (all African Americans) began singing:

On 11 March 1792, Nathaniel Gilbert, a white preacher, prayed and preached a sermon under the large

Cotton Tree, and Reverend

David George preached the first recorded Baptist service in Africa. The land was dedicated and christened 'Free Town' according to the instructions of the Sierra Leone Company Directors. This was the first thanksgiving service in the newly christened Free Town and was the beginning of the political entity of Sierra Leone. Later, John Clarkson would be sworn in as the first governor of Sierra Leone. Small huts were erected before the rainy season. The Sierra Leone Company surveyors and the settlers built Freetown on the American grid pattern, with parallel streets and wide roads, with the largest being Water Street.

On 24 August 1792, the Black Poor or Old Settlers of the second Granville Town were incorporated into the new Sierra Leone Colony but remained at Granville Town. It survived being pillaged by the

French in 1794, and was rebuilt by the Nova Scotian settlers. By 1798, Freetown had 300–400 houses with architecture resembling that of the American South, with 3- to 4-foot stone foundations and wooden superstructures. Eventually this style of housing (brought by the Nova Scotians) would be the model for the 'bod oses' of their

Creole descendants.

Settlement by Jamaican Maroons (1800)

In 1800, the Nova Scotians rebelled and it was the arrival of over 500

Jamaican Maroons

Jamaican Maroons descend from Africans who freed themselves from slavery on the Colony of Jamaica and established communities of free black people in the island's mountainous interior, primarily in the eastern parishes. Africans who were ensla ...

which caused the rebellion to be suppressed. Thirty-four Nova Scotians were banished and sent to either to

Sherbro Island

Sherbro Island is in the Atlantic Ocean, and is included within Bonthe District, Southern Province, Sierra Leone. The island is separated from the African mainland by the Sherbro River in the north and Sherbro Strait in the east. It is long a ...

or a penal colony at Gore. Some of these were eventually allowed back into Freetown. Following their capture of the rebels, the Maroons were granted the land of the Nova Scotian rebels. Eventually the

Jamaican Maroons in Sierra Leone

The Jamaican Maroons in Sierra Leone were a group of just under 600 Jamaican Maroons from Cudjoe's Town, the largest of the five Jamaican maroon towns who were deported by the British authorities in Jamaica following the Second Maroon War in ...

had their own district at the newly named Maroon Town.

The Maroons were a free community of blacks from

Cudjoe's Town (Trelawny Town)

Cudjoe's Town was located in the mountains in the southern extremities of the parish of St James, close to the border of Westmoreland, Jamaica.

In 1690, a large number of Akan freedom fighters from Sutton's Estate in south-western Jamaica, and th ...

who had been resettled in Nova Scotia after surrendering to the British government followed the

Second Maroon War of 1795–6. They had petitioned the British government for settlement elsewhere due to the climate in Nova Scotia.

Abolition and slaves-in-transit (1807 - 1830s)

Britain outlawed the

slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

throughout its empire on 29 March 1807 with the

Slave Trade Act 1807

The Slave Trade Act 1807, officially An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom prohibiting the slave trade in the British Empire. Although it did not abolish the practice of slavery, it ...

, though the practice continued in the British Empire until it was finally abolished in the 1830s. The Royal Navy's

West Africa Squadron

The West Africa Squadron, also known as the Preventative Squadron, was a squadron of the British Royal Navy whose goal was to suppress the Atlantic slave trade by patrolling the coast of West Africa. Formed in 1808 after the British Parliame ...

operating from Freetown took active measures to intercept and seize ships participating in the illegal Atlantic slave trade. The slaves that were held on these vessels were released into Freetown and were initially called

'Captured negroes', 'Recaptives' or 'Liberated Africans'.

Formation of the Sierra Leone Creole ethnicity (1870 onwards)

The

Sierra Leone Creole people

The Sierra Leone Creole people ( kri, Krio people) are an ethnic group of Sierra Leone. The Sierra Leone Creole people are lineal descendant, descendants of freed African-American, Afro-Caribbean, and Liberated African slaves who settled in ...

( kri, Krio people) are

descendants of the

Black Poor

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have ...

, freed African Americans (Nova Scotian

Black Loyalists

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the Cro ...

),

Afro-Caribbean

Afro-Caribbean people or African Caribbean are Caribbean people who trace their full or partial ancestry to Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the modern African-Caribbeans descend from Africans taken as slaves to colonial Caribbean via the ...

s (

Jamaican Maroons

Jamaican Maroons descend from Africans who freed themselves from slavery on the Colony of Jamaica and established communities of free black people in the island's mountainous interior, primarily in the eastern parishes. Africans who were ensla ...

), and

Liberated African

The liberated Africans of Sierra Leone, also known as recaptives, were Africans who had been illegally enslaved onboard slave ships and rescued by anti-slavery patrols from the West Africa Squadron of the Royal Navy. After the British Parliament ...

s who settled in the

Western Area

The Western Area or Freetown Peninsula (formerly the Colony of Sierra Leone) is one of five principal divisions of Sierra Leone. It comprises the oldest city and national capital Freetown and its surrounding towns and countryside. It covers an a ...

of Sierra Leone between 1787 and about 1885.

[ https://www.persee.fr/doc/cea_0008-0055_1991_num_31_121_2116][ Journal of Sierra Leone Studies, Vol. 3; Edition 1, 2014 https://www.academia.edu/40720522/A_Precis_of_Sources_relating_to_genealogical_research_on_the_Sierra_Leone_Krio_people] The

colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the ''metropole, metropolit ...

was established by the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

, supported by

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

s, under the

Sierra Leone Company as a place for

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

. The settlers called their new settlement

Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and p ...

.

[, originally published by Longman & Dalhousie University Press (1976).]

Colonial era (1808–1961)

Establishment of the British Crown Colony (1808)

In 1808, the

British Crown Colony of Sierra Leone was founded, with Freetown serving as the capital of

British West Africa

British West Africa was the collective name for British colonies in West Africa during the colonial period, either in the general geographical sense or the formal colonial administrative entity. British West Africa as a colonial entity was orig ...

. The city's population expanded rapidly with freed slaves, who established suburbs on the Freetown Peninsula. They were joined by West Indian and African soldiers who settled in Sierra Leone after fighting for Britain in the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

.

Intervention and acquisition of the hinterland (1800s–1895)

In the early 1800s, Sierra Leone was a small colony extending a few kilometres (a few miles) up the peninsula from Freetown. The bulk of the territory that makes up present-day Sierra Leone was still the

sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title which can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin , meaning 'above'.

The roles of a sovereign vary from monarch, ruler or ...

territory of indigenous peoples such as the

Mende and

Temne, and was little affected by the tiny population of the Colony. Over the course of the 19th century, that gradually changed: the British and

Creoles in the Freetown area increased their involvement in—and their control over—the surrounding territory by engaging in trade, which was promoted and increased through treaty-making and military expeditions.

In their treaties with the native chiefs, the British were largely concerned with securing local peace so that commerce would not be interrupted. Typically, the British government agreed to pay a chief a stipend in return for a commitment from him to keep the peace with his neighbours; other specific commitments extracted from a chief might include keeping roads open, allowing the British to collect customs duties, and submitting disputes with his neighbours to British adjudication. In the decades following Britain's prohibition of the slave trade in 1807, the treaties sometimes also required chiefs to desist from slave-trading. Suppression of slave-trading and suppression of inter-chiefdom war went hand-in-hand because the trade thrived on the wars (and caused them). Thus, to the commercial reasons for pacification could be added anti-slavery ones.

When friendly persuasion failed to secure their interests, the British were not above (to borrow

Carl von Clausewitz

Carl Philipp Gottfried (or Gottlieb) von Clausewitz (; 1 June 1780 – 16 November 1831) was a Prussian general and military theorist who stressed the "moral", in modern terms meaning psychological, and political aspects of waging war. His mos ...

's phrase) "continuing diplomacy by other means". At least by the mid-1820s, the army and navy were going out from the Colony to attack chiefs whose behaviour did not conform to British dictates. In 1826, Governor Turner led troops to the

Bum–

Kittam area, captured two stockaded towns, burnt others, and declared a blockade on the coast as far as

Cape Mount. This was partly an anti-slaving exercise and partly to punish the chief for refusing territory to the British. Later that year, acting-Governor Macaulay sent out an expedition which went up the

Jong river

The Jong or Taia river is a river flowing through Sierra Leone. It passes by the city of Mattru Jong, and flows into the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers ...

and burned

Commenda The commenda was a medieval contract which developed in Italy around the 10th century, and was an early form of limited partnership. The commenda was an agreement between an investing partner and a traveling partner to conduct a commercial enterpris ...

, a town belonging to a related chief. In 1829, the colonial authorities founded the

Sierra Leone Police Corps. In 1890, this force was divided into the Civilian Police and the Frontier Police.

The British developed a

modus operandi

A ''modus operandi'' (often shortened to M.O.) is someone's habits of working, particularly in the context of business or criminal investigations, but also more generally. It is a Latin phrase, approximately translated as "mode (or manner) of op ...

which characterised their interventions throughout the century: army or frontier police, with naval support if possible, would bombard a town and then usually torch it after the defenders had fled or been defeated. Where possible, local enemies of the party being attacked were invited by the British to accompany them as allies.

In the 1880s, Britain's intervention in the hinterland received added impetus because of the "

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonisation of Africa, colonization of most of Africa by seven Western Europe, Western European powers during a ...

": an intense competition between the European powers for territory in Africa. In this case, the rival was France. To forestall French incursion into what they had come to consider as their own sphere, the British government renewed efforts to finalise a boundary agreement with France and on 1 January 1890 instructed Governor Hay in Sierra Leone to get from chiefs in the boundary area friendship treaties containing a clause forbidding them to treat with another European power without British consent.

Consequently, in 1890 and 1891 Hay and two travelling commissioners, Garrett and Alldridge, went on extensive tours of what is now Sierra Leone obtaining treaties from chiefs. Most of these were not, however, treaties of cession; they were in the form of cooperative agreements between two sovereign powers.

In January 1895, a boundary agreement was signed in Paris, roughly fixing the line between French Guinea and Sierra Leone. The exact line was to be determined by surveyors. As Christopher Fyfe notes, "The delimitation was made almost entirely in geographical terms—rivers, watersheds, parallels—not political. Samu chiefdom, for instance, was divided; the people on the frontier had to opt for farms on one side or villages on the other."

More generally, the arbitrary lumping-together of disparate native peoples into geographical units decided by the colonial powers has been an ongoing source of trouble throughout Africa. These geographical units are now attempting to function as nations but are not naturally nations, being composed in many cases of peoples who are traditional enemies. In Sierra Leone, for example, the Mende, Temne and Creoles remain as rival power blocs between whom lines of fission easily emerge.

Establishment of the British Protectorate and further land acquisition (1895)

In August 1895, an Order-in-Council was issued in Britain authorising the Colony to make laws for the territory around it, extending out to the agreed-upon boundary (which corresponds closely to that of present-day Sierra Leone). On 31 August 1896, a Proclamation was issued in the Colony declaring that territory to be a

British Protectorate. The Colony remained a distinct political entity; the Protectorate was governed from it.

Most of the chiefs whose territories the Protectorate subsumed did not enter into it voluntarily. Many had signed treaties of friendship with Britain, but these were often expressed as being between sovereign powers, with there was no subordination to the British. Only a handful of chiefs had signed treaties of cession, and in some cases it is unknown if the chiefs had understood the implications of the treaty. In more remote areas, no treaties had been signed at all. The creation of the Sierra Leone Protectorate was more in the nature of a unilateral acquisition of territory by the British.

Almost every chieftaincy in Sierra Leone responded to the British arrogation of power with armed resistance. The Protectorate Ordinances (passed in the Colony in 1896 and 1897) abolished the title of King and replaced it with "Paramount Chief". Chiefs and kings had formerly been selected by the leading members of their own communities; now all chiefs, even paramount ones, could be deposed or installed at the will of the Governor, and most of the judicial powers of the chiefs were removed and given to courts presided-over by British "District Commissioners". The Governor decreed that a

house tax

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condit ...

of 5''s'' to 10''s'' was to be levied annually on every dwelling in the Protectorate. To the chiefs, these reductions in their power and prestige were unbearable.

During these conflicts, British officers used the practice of cutting the hands of people to account for bullets spent, similar to what had occurred under the regime

Leopold II of Belgium

* german: link=no, Leopold Ludwig Philipp Maria Viktor

, house = Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

, father = Leopold I of Belgium

, mother = Louise of Orléans

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Brussels, Belgium

, death_date = ...

in the

Congo Free State

''(Work and Progress)

, national_anthem = Vers l'avenir

, capital = Vivi Boma

, currency = Congo Free State franc

, religion = Catholicism (''de facto'')

, leader1 = Leopo ...

. British doctor, Jason Todd, who had travelled to West Africa on an LSTM expedition, wrote down the testimonies of British officers who had been involved in putting down rebellions in British Sierra Leone and had practiced cutting the hands of the people they shot. The exact number of living victims who ended up mutilated is unknown.

Hut Tax War of 1898

In 1898,

two rebellions broke out against British colonial rule in Sierra Leone in response to the introduction of a new

hut tax

The hut tax was a form of taxation introduced by British in their African possessions on a "per hut" (or other forms of household) basis. It was variously payable in money, labour, grain or stock and benefited the colonial authorities in four inter ...

by Governor

Frederic Cardew

Colonel Sir Frederic Cardew, KCMG (27 September 1839 – 6 July 1921) was a British Army officer and colonial governor. He was Governor of Sierra Leone

This is a list of colonial administrators in Sierra Leone from the establishment of the Cli ...

. On 1 January 1898, Cardew introduced the hut tax as a way to pay for the colonial administration's financial expenditures. However, the tax proved to be beyond the financial means of many in the colony, provoking discontent. In February 1898, an attempt by colonial officials to arrest

Temne chief

Bai Bureh

Bai Bureh (February 15, 1840 – August 24, 1908) was a Sierra Leonean ruler, Military strategy, military strategist, and Muslim cleric, who led the Temne and Loko uprising against British rule in 1898 in Northern Sierra Leone.

Early life and ...

led to him and rebels under his command to revolt against British rule. Bureh's forces launched attacks on British officials and

Creole traders.

Despite the ongoing rebellion, Bureh dispatched two peace overtures to the British in April and June of that year, aided by the mediation of

Limba chief

Almamy Suluku. Cardew rejected both offers, as Bureh would not agree to surrender unconditionally. Bureh's forces conducted a disciplined and skillfully executed

guerrilla campaign which caused the British considerable difficulty. Hostilities began in February; Bureh's harassing tactics confounded the British at first but by May they were gaining ground. The rainy season interrupted hostilities until October, when British colonial forces resumed the slow process of capturing rebel stockades. When most of these defences had been eliminated, Bureh was captured or surrendered (accounts differ) in November.