History of Philadelphia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The city of

In 1681, King Charles II gave Penn a large piece of his newly acquired American land holdings to repay a debt the king owed to Admiral Sir William Penn, Penn's father. This land included present-day

In 1681, King Charles II gave Penn a large piece of his newly acquired American land holdings to repay a debt the king owed to Admiral Sir William Penn, Penn's father. This land included present-day

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

was founded in 1682 by William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

in the English Crown Province of Pennsylvania

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn after receiving a land grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania ("Penn's Woods") refers to W ...

between the Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

and Schuylkill rivers. Before then, the area was inhabited by the Lenape people

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory inclu ...

. Philadelphia quickly grew into an important colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

city and during the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

was the site of the First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

es. After the Revolution the city was chosen to be the temporary capital of the United States. At the beginning of the 19th century, the federal and state governments left Philadelphia, but the city remained the cultural and financial center of the country. Philadelphia became one of the first U.S. industrial centers and the city contained a variety of industries, the largest being textile

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

s.

After the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

Philadelphia's government was controlled by a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

political machine

In the politics of Representative democracy, representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a hig ...

and by the beginning of the 20th Century Philadelphia was described as "corrupt and contented." Various reform efforts slowly changed city government with the most significant in 1950 where a new city charter strengthened the position of mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well a ...

and weakened the Philadelphia City Council

The Philadelphia City Council, the legislative body of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, consists of ten members elected by district and seven members elected at-large. The council president is elected by the members from among their number. Each ...

. At the same time Philadelphia moved its supports from the Republican Party to the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

which has since created a strong Democratic organization. The city began a population decline in the 1950s as mostly white and middle-class families left for the suburbs. Many of Philadelphia's houses were in poor condition and lacked proper facilities, and gang

A gang is a group or society of associates, friends or members of a family with a defined leadership and internal organization that identifies with or claims control over territory in a community and engages, either individually or collectivel ...

and mafia

"Mafia" is an informal term that is used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the original “Mafia”, the Sicilian Mafia and Italian Mafia. The central activity of such an organization would be the arbitration of d ...

warfare plagued the city. Revitalization and gentrification

Gentrification is the process of changing the character of a neighborhood through the influx of more Wealth, affluent residents and businesses. It is a common and controversial topic in urban politics and urban planning, planning. Gentrification ...

of certain neighborhoods started bringing people back to the city. Promotions and incentives in the 1990s and the early 21st century have improved the city's image and created a condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership structure whereby a building is divided into several units that are each separately owned, surrounded by common areas that are jointly owned. The term can be applied to the building or complex ...

boom in Center City and the surrounding areas that has slowed the population decline.

Overview

In 1681, King Charles II gave Penn a large piece of his newly acquired American land holdings to repay a debt the king owed to Admiral Sir William Penn, Penn's father. This land included present-day

In 1681, King Charles II gave Penn a large piece of his newly acquired American land holdings to repay a debt the king owed to Admiral Sir William Penn, Penn's father. This land included present-day Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

and Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

, though the claim as written would create a bloody conflict with Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

(dubbed Cresap's War

Cresap's War (also known as the Conojocular War, from the Conejohela Valley where it was mainly located along the south bank) was a border conflict between Pennsylvania and Maryland, fought in the 1730s. Hostilities erupted in 1730 with a seri ...

) over the land grant already owned by Lord Baltimore. Penn put together a colonial expedition and fleet, which set out for America in the middle of the following summer. Penn, sailing in the vanguard, first set foot on American soil at the colony at New Castle, Delaware

New Castle is a city in New Castle County, Delaware, United States. The city is located six miles (10 km) south of Wilmington and is situated on the Delaware River. As of the 2010 census, the city's population was 5,285.

History

New Castl ...

. An orderly change of government ensued, as was normal in an age used to the privileges and prerogatives of aristocracy and which antedated nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

: the colonists pledged allegiance to Penn as their new Proprietor

Ownership is the state or fact of legal possession and control over property, which may be any asset, tangible or intangible. Ownership can involve multiple rights, collectively referred to as title, which may be separated and held by different ...

. The first Pennsylvania General Assembly

The Pennsylvania General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The legislature convenes in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg. In colonial times (1682–1776), the legislature was known as the Pennsylvania ...

was soon held in the colony.

Penn later journeyed up the river and founded Philadelphia with a core group of accompanying Quakers and others seeking religious freedom on lands he purchased from the local chieftains of the Lenape or Delaware nation

Delaware Nation ( del, Èhëliwsikakw Lënapeyok), also known as the Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma and sometimes called the Absentee or Western Delaware, based in Anadarko, Oklahoma This began a long period of peaceful co-operation between the colony and the Delaware, in contrast to the frictions between the tribe and the Swedish and Dutch colonists. However, the new colonists would not enjoy such easy relations with the rival and territorial Conestoga peoples to the west for a number of decades as the English Quaker and German Anabaptist, Lutheran and Moravian settlers attracted to the religiously tolerant colony worked their way northwest up the Schuylkill and due west south of the hill country into the breadbasket lands along the lower

Before Philadelphia was colonized by Europeans, the area was inhabited by the Lenape (Delaware) Indians. The

Before Philadelphia was colonized by Europeans, the area was inhabited by the Lenape (Delaware) Indians. The

Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River (; Lenape: Siskëwahane) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, overlapping between the lower Northeast and the Upland South. At long, it is the longest river on the East Coast of the ...

. Lord Baltimore and the Province of Maryland had circa 1652–53 finished waging a decade long ''declared war'' against the Susquehannocks and the Dutch, who'd been trading them fur

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

s for tools and firearms for some time. Both groups had uneasy relations with the Delaware (Lenape) and the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

. Furthermore, Penn's Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

government was not viewed favorably by the Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

, and English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

settlers in what is now Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

. They had no "historical" allegiance to Pennsylvania, so they almost immediately began petitioning for their own Assembly. In 1704, they achieved their goal when the three southernmost counties of Pennsylvania were permitted to split off and become the new semi-autonomous colony of Lower Delaware. New Castle, the most prominent, prosperous and influential settlement in the new colony, became the capital. During its brief period of ascendancy as an empire following the victory by Gustav the Great in the Battle of Breitenfeld Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

settlers arrived in the area in the early 17th century to found a nearby colony, New Sweden

New Sweden ( sv, Nya Sverige) was a Swedish colony along the lower reaches of the Delaware River in what is now the United States from 1638 to 1655, established during the Thirty Years' War when Sweden was a great military power. New Sweden form ...

in what is today southern New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

. With the arrival of more numerous English colonists and development of the port on the Delaware, Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

quickly grew into an important colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

city.

During the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

, Philadelphia was the site of the First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

es.

After George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

's defeat at the Battle of Brandywine

The Battle of Brandywine, also known as the Battle of Brandywine Creek, was fought between the American Continental Army of General George Washington and the British Army of General Sir William Howe on September 11, 1777, as part of the Ame ...

on September 11, 1777, the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia was defenseless, and the city prepared for what was seen as an inevitable British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

attack. Because bells could easily be recast into munitions, one of those preparations was hastily removing the Liberty Bell

The Liberty Bell, previously called the State House Bell or Old State House Bell, is an iconic symbol of American independence, located in Philadelphia. Originally placed in the steeple of the Pennsylvania State House (now renamed Independence ...

(and other Philadelphia bells) and sending them by heavily guarded wagon train to the Zion German Reformed Church in Northampton Town (present-day Allentown Allentown may refer to several places in the United States and topics related to them:

*Allentown, California, now called Toadtown, California

*Allentown, Georgia, a town in Wilkinson County

*Allentown, Illinois, an unincorporated community in Taze ...

), where it was hidden under the church floor boards during the British occupation of Philadelphia

The Philadelphia campaign (1777–1778) was a British effort in the American Revolutionary War to gain control of Philadelphia, which was then the seat of the Second Continental Congress. British General William Howe, after failing to draw ...

.Nash, p. 19 The Liberty Bell remained hidden in Allentown from September 1777 until its return to Philadelphia in June 1778, following the British retreat from Philadelphia on June 18, 1778.

After the Revolution's conclusion in 1783, Philadelphia was chosen to be the temporary capital of the United States from 1790 to 1800, and the city continued for some years to be the country's cultural and financial center. Its large free black community aided fugitive slaves and founded the first independent black denomination in the nation, the African Methodist Episcopal Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a Black church, predominantly African American Methodist Religious denomination, denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexionalism, c ...

. Philadelphia became one of the first U.S. industrial centers with a variety of industries, the largest being textile

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

s. It had many economic and family ties to the South, with southern planters maintaining second homes in the city and having business connections with banks, sending their daughters to French finishing schools run by refugees from Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer ...

(Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

), selling their cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

to textile manufacturers, which in turn sold some products to the South, for instance, clothing for slaves. At the beginning of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, there were many southern sympathizers, although most city residents became firmly Union as the war went on.

After the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, city government was controlled by the Republican Party; it established a political machine

In the politics of Representative democracy, representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a hig ...

that gained power through patronage. By the beginning of the 20th century, Philadelphia was described as "corrupt and contented." Various reform efforts slowly changed city government; in 1950, a new city charter strengthened the position of mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well a ...

and weakened the Philadelphia City Council

The Philadelphia City Council, the legislative body of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, consists of ten members elected by district and seven members elected at-large. The council president is elected by the members from among their number. Each ...

. Beginning during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, voters changed from traditional support for the Republican Party to increasing support for the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

of President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, which has now been predominant in local politics for many decades.

The population grew dramatically at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, through immigration from Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, Southern Europe

Southern Europe is the southern regions of Europe, region of Europe. It is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is essentially marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of Southern Europe include some or all of these countrie ...

, Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

, and Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

, as well as the Great Migration of blacks from the rural South and Puerto Ricans

Puerto Ricans ( es, Puertorriqueños; or boricuas) are the people of Puerto Rico, the inhabitants, and citizens of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and their descendants.

Overview

The culture held in common by most Puerto Ricans is referred t ...

from the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

, all attracted to the city's expanding industrial jobs. The Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

was expanding and hired 10,000 workers from the South. Manufacturing plants and the US Navy Yard employed tens of thousands of industrial workers along the rivers, and the city was also a center of finance and publishing, with major universities. By the 1950s, much Philadelphia housing was aged and substandard. In the post-World War II era of suburbanization and construction of area highways, many middle-class families met their demand for newer housing by leaving the city for the suburbs. Population decline accompanied the industrial restructuring and the loss of tens of thousands of jobs in the mid 20th century. With increasing poverty and social dislocation in the city, gang

A gang is a group or society of associates, friends or members of a family with a defined leadership and internal organization that identifies with or claims control over territory in a community and engages, either individually or collectivel ...

and mafia

"Mafia" is an informal term that is used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the original “Mafia”, the Sicilian Mafia and Italian Mafia. The central activity of such an organization would be the arbitration of d ...

warfare plagued the city in from the mid-20th century to the early 21st century.

By the end of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st, revitalization and gentrification

Gentrification is the process of changing the character of a neighborhood through the influx of more Wealth, affluent residents and businesses. It is a common and controversial topic in urban politics and urban planning, planning. Gentrification ...

of historic neighborhoods attracted an increase in middle-class population as people began to return to the city. New immigrants from Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

, and Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

and South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

have contributed their energy to the city. Promotions and incentives in the 1990s and the early 21st century have improved the city's image and created a condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership structure whereby a building is divided into several units that are each separately owned, surrounded by common areas that are jointly owned. The term can be applied to the building or complex ...

boom in Center City and the surrounding areas.

Native settlements and initial European presence

Before Philadelphia was colonized by Europeans, the area was inhabited by the Lenape (Delaware) Indians. The

Before Philadelphia was colonized by Europeans, the area was inhabited by the Lenape (Delaware) Indians. The Delaware River Valley

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware, before em ...

was called the ''Zuyd'', meaning "South" River, or ''Lënapei Sipu.''

Located north of what will eventually become the Center City and on the east bank of the Schuylkill was a Lenape settlement named Coaquannock, meaning "grove of pines." One of the largest Lenape settlement in the region, located in today's South Philadelphia

South Philadelphia, nicknamed South Philly, is the section of Philadelphia bounded by South Street to the north, the Delaware River to the east and south and the Schuylkill River to the west.Passyunk, meaning "in the valley." Other settlements including the village of Nitapèkunk, "place that is easy to get to," located in today's Fairmount Park area. And the villages of Pèmikpeka, "where the water flows," and

Penn sent three commissioners to supervise the settlement and to set aside 10,000 acres (40 km2) for the city. The commissioners bought land from Swedes at the settlement of

Penn sent three commissioners to supervise the settlement and to set aside 10,000 acres (40 km2) for the city. The commissioners bought land from Swedes at the settlement of

In the 1760s, the

In the 1760s, the

US History, 2010, accessed 29 March 2012 The remains of the President's House were found during excavation for a new Liberty Bell Center, leading to archeological work in 2007. In 2010, a memorial on the site opened to commemorate Washington's slaves and African Americans in Philadelphia and U.S. history, as well as to mark the house site.

The lawlessness and the difficulty in controlling it, along with residential development just north of Philadelphia, led to the Act of Consolidation, 1854, Act of Consolidation in 1854. The act passed on February 2, making Philadelphia's borders coterminous with Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia County, and incorporating various subdistrict within the county.

Once the

The lawlessness and the difficulty in controlling it, along with residential development just north of Philadelphia, led to the Act of Consolidation, 1854, Act of Consolidation in 1854. The act passed on February 2, making Philadelphia's borders coterminous with Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia County, and incorporating various subdistrict within the county.

Once the

Shackamaxon

The Treaty of Shackamaxon, also called the Great Treaty and Penn's Treaty, was a legendary treaty between William Penn and Tamanend of the Lenape signed in 1682. Penn and Tamanend agreed that their people would live in a state of perpetual peace ...

, "place where the chief was crowned", both were located on the west bank of Delaware River, upstream from today's Northern Liberties

Northern Liberties is a neighborhood in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Prior to its incorporation into Philadelphia in 1854, it was among the top 10 largest cities in the U.S. in every census from 1790 to 1850.

Boundaries

Northern Liberties is loc ...

.

The first exploration of the area by Europeans was in 1609, when a Dutch expedition led by Henry Hudson entered the Delaware River Valley in search of the Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arc ...

. The Valley, including the future location of Philadelphia, became part of the New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the East Coast of the United States, east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territor ...

claim of the Dutch. Around 1630s, to control the Great Minquas Path, a fur trade route to the Susquehannock

The Susquehannock people, also called the Conestoga by some English settlers or Andastes were Iroquoian Native Americans who lived in areas adjacent to the Susquehanna River and its tributaries, ranging from its upper reaches in the southern p ...

which passed through Philadelphia region, the Dutch authority of New Netherland built a palisaded factorij

Factory was the common name during the medieval and early modern eras for an entrepôt – which was essentially an early form of free-trade zone or transshipment point. At a factory, local inhabitants could interact with foreign merchants, ...

located near the confluence of the Schuylkill River and the Delaware River, named Fort Beversreede

Fort Beversreede (after 1633–1651) was a Dutch-built palisaded factorij located near the confluence of the Schuylkill River and the Delaware River. It was an outpost of the colony of New Netherland, which was centered on its capital, New Amste ...

.

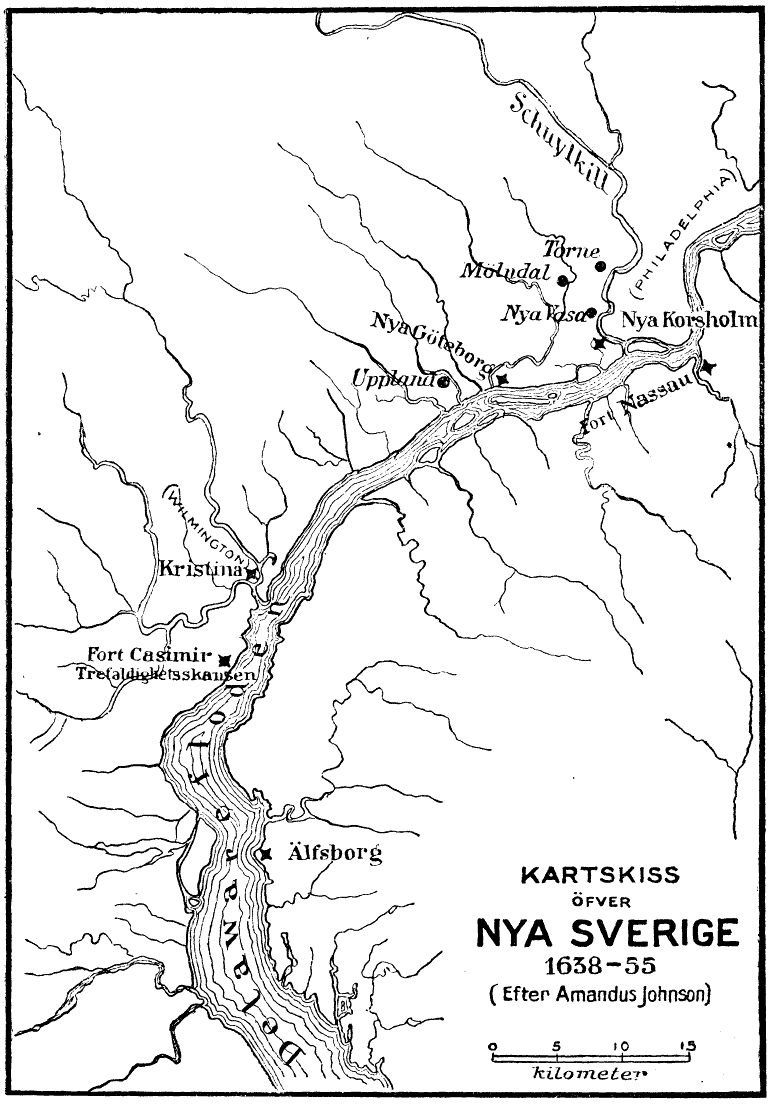

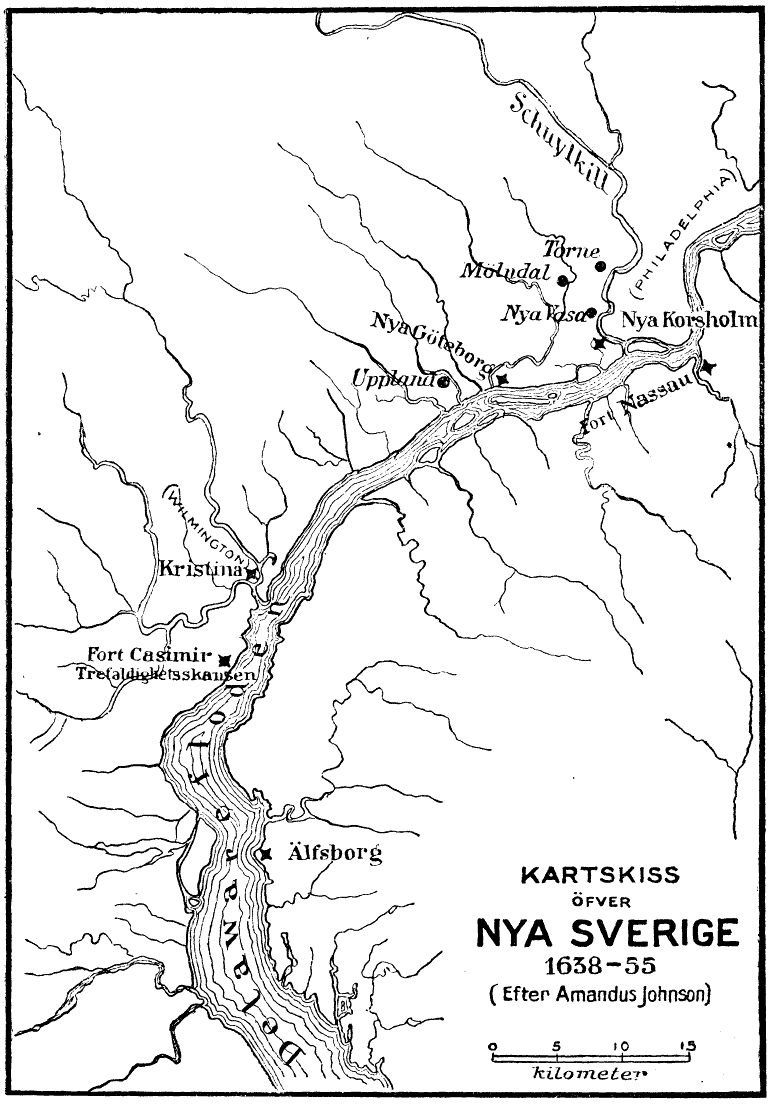

In 1637, Swedish, Dutch and German stockholders formed the New Sweden

New Sweden ( sv, Nya Sverige) was a Swedish colony along the lower reaches of the Delaware River in what is now the United States from 1638 to 1655, established during the Thirty Years' War when Sweden was a great military power. New Sweden form ...

Company to trade for furs and tobacco in North America. Under the command of Peter Minuit

Peter Minuit (between 1580 and 1585 – August 5, 1638) was a Wallonian merchant from Tournai, in present-day Belgium. He was the 3rd Director of the Dutch North American colony of New Netherland from 1626 until 1631, and 3rd Governor of New N ...

, the company's first expedition sailed from Sweden late in 1637 in two ships, ''Kalmar Nyckel

''Kalmar Nyckel'' (''Key of Kalmar'') was a Swedish ship built by the Dutch famed for carrying Swedish settlers to North America in 1638, to establish the colony of New Sweden. The name Kalmar Nyckel comes from the Swedish city of Kalmar and nyc ...

'' and ''Fogel Gri''. Minuit had been the governor of the New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the East Coast of the United States, east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territor ...

from 1626 to 1631. Resenting his dismissal by the Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company ( nl, Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie, ''WIC'' or ''GWC''; ; en, Chartered West India Company) was a chartered company of Dutch merchants as well as foreign investors. Among its founders was Willem Usselincx ( ...

, he brought to the new project the knowledge that the Dutch colony had temporarily abandoned its efforts in the Delaware Valley to focus on the Hudson River valley to the north. The ships reached Delaware Bay in March 1638, and the settlers began to build a fort at the site of present-day Wilmington, Delaware

Wilmington ( Lenape: ''Paxahakink /'' ''Pakehakink)'' is the largest city in the U.S. state of Delaware. The city was built on the site of Fort Christina, the first Swedish settlement in North America. It lies at the confluence of the Christina ...

. They named it Fort Christina, in honor of the twelve-year-old Queen Christina of Sweden. It was the first permanent European settlement in the Delaware Valley. Part of this colony eventually included land on the west side of the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

from just below the Schuylkill River

The Schuylkill River ( , ) is a river running northwest to southeast in eastern Pennsylvania. The river was improved by navigations into the Schuylkill Canal, and several of its tributaries drain major parts of Pennsylvania's Coal Region. It fl ...

.

Johan Björnsson Printz

Johan Björnsson Printz (July 20, 1592 – May 3, 1663) was governor from 1643 until 1653 of the Swedish colony of New Sweden on the Delaware River in North America.

Early life in Sweden

He was born in Bottnaryd, Jönköping County, in the pro ...

was appointed to be the first royal governor of New Sweden, arriving in the colony on February 15, 1643. Under his ten-year rule, the administrative center of New Sweden

New Sweden ( sv, Nya Sverige) was a Swedish colony along the lower reaches of the Delaware River in what is now the United States from 1638 to 1655, established during the Thirty Years' War when Sweden was a great military power. New Sweden form ...

was moved north to Tinicum Island, to the immediate southwest of today's Philadelphia, where he built an outpost called Fort New Gothenburg and his own manor house which he called the Printzhof

The Printzhof, located in Governor Printz Park in Essington, Pennsylvania, was the home of Johan Björnsson Printz, governor of New Sweden.

In 1643, Johan Printz moved his capital from Fort Christina (located in what is now Wilmington, Delaware) ...

.

The first English settlement occurred about 1642, when 50 Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

families from the New Haven Colony

The New Haven Colony was a small English colony in North America from 1638 to 1664 primarily in parts of what is now the state of Connecticut, but also with outposts in modern-day New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware.

The history o ...

in Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

, led by George Lamberton, tried to establish a theocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deity, deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy origina ...

at the mouth of the Schuylkill River

The Schuylkill River ( , ) is a river running northwest to southeast in eastern Pennsylvania. The river was improved by navigations into the Schuylkill Canal, and several of its tributaries drain major parts of Pennsylvania's Coal Region. It fl ...

. The New Haven Colony had earlier struck a deal with the Lenape to buy much of New Jersey south of present-day Trenton. The Dutch and Swedes in the area burned the English colonists' buildings. A Swedish court under Swedish Governor Johan Björnsson Printz

Johan Björnsson Printz (July 20, 1592 – May 3, 1663) was governor from 1643 until 1653 of the Swedish colony of New Sweden on the Delaware River in North America.

Early life in Sweden

He was born in Bottnaryd, Jönköping County, in the pro ...

convicted Lamberton of "trespassing, conspiring with the Indians." The offshoot New Haven colony received no support. The Puritan Governor John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

said it was dissolved owing to summer "sickness and mortality." The disaster contributed to New Haven's losing control of its area to the larger Connecticut Colony

The ''Connecticut Colony'' or ''Colony of Connecticut'', originally known as the Connecticut River Colony or simply the River Colony, was an English colony in New England which later became Connecticut. It was organized on March 3, 1636 as a settl ...

.

In 1644, New Sweden

New Sweden ( sv, Nya Sverige) was a Swedish colony along the lower reaches of the Delaware River in what is now the United States from 1638 to 1655, established during the Thirty Years' War when Sweden was a great military power. New Sweden form ...

supported the Susquehannock

The Susquehannock people, also called the Conestoga by some English settlers or Andastes were Iroquoian Native Americans who lived in areas adjacent to the Susquehanna River and its tributaries, ranging from its upper reaches in the southern p ...

in their successful conflict with Maryland colonists led by General Harrison II. With the alliance with Susquehannock, the Swedes further strengthened their claims for land at the mouth of the Schuylkill River. In 1648, New Sweden built a stockaded 30-by-20-foot blockhouse

A blockhouse is a small fortification, usually consisting of one or more rooms with loopholes, allowing its defenders to fire in various directions. It is usually an isolated fort in the form of a single building, serving as a defensive stro ...

directly in front of the Dutch Fort Beversreede, called Fort Nya Korsholm or Fort New Korsholm

Korsholm (; fi, Mustasaari) is a municipality of Finland. The town of Vaasa was founded in Korsholm parish in 1606 and today the municipality completely surrounds the city. It is a coastal, mostly rural municipality, consisting of a rural landscap ...

. The Swedish building was said to be only twelve feet from the gate of the Dutch fort and was meant to intimidate the Dutch residents and intercept trade. As a result, the Dutch abandoned Fort Beversreede in 1651 and dismantled and relocated the nearby Fort Nassau to the Christina River

The Christina River is a tributary of the Delaware River, approximately 35 miles (56 km) long, in northern Delaware in the United States, also flowing through small areas of southeastern Pennsylvania and northeastern Maryland. Near i ...

, downstream from the Swedes' Fort Christina. The Dutch consolidated their forces at the rebuilt fort, renamed Fort Casimir

Fort Casimir or Fort Trinity was a Dutch fort in the seventeenth-century colony of New Netherland. It was located on a no-longer existing barrier island at the end of Chestnut Street in what is now New Castle, Delaware.

Background

The Dutch c ...

.

The Dutch never recognized the legitimacy of the Swedish claim and, in the late summer of 1655, Director-General Peter Stuyvesant

Peter Stuyvesant (; in Dutch also ''Pieter'' and ''Petrus'' Stuyvesant, ; 1610 – August 1672)Mooney, James E. "Stuyvesant, Peter" in p.1256 was a Dutch colonial officer who served as the last Dutch director-general of the colony of New Net ...

of New Amsterdam mustered a military expedition to the Delaware Valley to subdue the rogue colony. Although the colonists had to recognize the authority of New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the East Coast of the United States, east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territor ...

, the Dutch terms were tolerant. The Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

and Finnish

Finnish may refer to:

* Something or someone from, or related to Finland

* Culture of Finland

* Finnish people or Finns, the primary ethnic group in Finland

* Finnish language, the national language of the Finnish people

* Finnish cuisine

See also ...

settlers continued to enjoy a much local autonomy, having their own militia, religion, court, and lands. This official status lasted until the English capture of New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the East Coast of the United States, east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territor ...

in October 1664, and continued unofficially until the area was included in William Penn's charter for Pennsylvania in 1682.

The Swedish immigration and expansion continued in the Philadelphia region. In 1669, one of the founders of the New Sweden, Sven Gunnarsson, moved into the region and settled at a place called Wicaco, a former native settlement located on today's Society Hill

Society Hill is a historic neighborhood in Center City Philadelphia, with a population of 6,215 . Settled in the early 1680s, Society Hill is one of the oldest residential neighborhoods in Philadelphia.The Center City District dates the Free Soc ...

and Queens Village

Queens Village is a mostly residential middle class neighborhood in the eastern part of the New York City borough of Queens. It is bound by Hollis to the west, Cambria Heights to the south, Bellerose to the east, and Oakland Gardens to the north ...

in South Philadelphia, beginning with a log blockhouse. The Swedish congregation on Tinicum Island moved to Wicaco in 1677, and repurposed the blockhouse as their church, five years before the founding of the city of Philadelphia. Sven Gunnarsson died in 1678 and was one of the first buried at the church. The church and the cemetery eventually became the Gloria Dei (Old Swedes') Church

Gloria Dei Church, known locally as Old Swedes, is a historic church located in the Southwark neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at 929 South Water Street, bounded by Christian Street on the north, South Christopher Columbus Boulevard ( ...

of Philadelphia, the oldest church in Pennsylvania.

By 1682, the area of modern Philadelphia was inhabited by about fifty Europeans, mostly subsistence farmers live in and around the Wicaco settlement.

Founding

In 1681, as part of a repayment of a debt, King Charles II grantedWilliam Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

a charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

for what would become the Pennsylvania colony

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn after receiving a land grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania ("Penn's Woods") refers to Wi ...

. Shortly after receiving the charter, Penn said he would lay out "a large Towne or Citty in the most Convenient place upon the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

for health & Navigation." Penn wanted the city to live peacefully in the area, without a fortress or walls

Walls may refer to:

*The plural of wall, a structure

*Walls (surname), a list of notable people with the surname

Places

* Walls, Louisiana, United States

* Walls, Mississippi, United States

* Walls, Ontario, neighborhood in Perry, Ontario, C ...

, so he bought the land from the Lenape. The legend

A legend is a Folklore genre, genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived, both by teller and listeners, to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human valu ...

is that Penn made a treaty of friendship with Lenape chief Tammany

Tamanend (historically also known as Taminent, Tammany, Saint Tammany or King Tammany, "the Affable," ) (–) was the Chief of Chiefs and Chief of the Turtle Clan of the Lenni-Lenape nation in the Delaware Valley signing the Peace Treaty with ...

under an elm tree at Shackamaxon

The Treaty of Shackamaxon, also called the Great Treaty and Penn's Treaty, was a legendary treaty between William Penn and Tamanend of the Lenape signed in 1682. Penn and Tamanend agreed that their people would live in a state of perpetual peace ...

, in what became the city's Kensington District.

Penn envisioned a city where all people regardless of religion could worship freely and live together. Being a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

, Penn had experienced religious persecution. He also planned that the city's streets would be set up in a grid, with the idea that the city would be more like the rural towns of England than its crowded cities. The homes would be spread far apart and surrounded by gardens and orchards. The city granted the first purchasers land along the Delaware River for their homes. It had access to the Delaware Bay and Atlantic Ocean, and became an important port in the Thirteen Colonies. He named the city Philadelphia (''philos'', "love" or "friendship", and ''adelphos'', "brother"); it was to have a commercial center for a market, state house, and other key buildings. The grid plan was adapted from a grid plan originally designed by cartographer Richard Newcourt for London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

.

Penn sent three commissioners to supervise the settlement and to set aside 10,000 acres (40 km2) for the city. The commissioners bought land from Swedes at the settlement of

Penn sent three commissioners to supervise the settlement and to set aside 10,000 acres (40 km2) for the city. The commissioners bought land from Swedes at the settlement of Wicaco

New Sweden ( sv, Nya Sverige) was a Swedish colony along the lower reaches of the Delaware River in what is now the United States from 1638 to 1655, established during the Thirty Years' War when Sweden was a great military power. New Sweden fo ...

, and from there began to lay out the city toward the north. The area went about a mile along the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

between modern South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

and Vine Streets. Penn's ship anchored off the coast of New Castle, Delaware

New Castle is a city in New Castle County, Delaware, United States. The city is located six miles (10 km) south of Wilmington and is situated on the Delaware River. As of the 2010 census, the city's population was 5,285.

History

New Castl ...

, on October 27, 1682, and he arrived in Philadelphia a few days after that. He expanded the city west to the bank of the Schuylkill River

The Schuylkill River ( , ) is a river running northwest to southeast in eastern Pennsylvania. The river was improved by navigations into the Schuylkill Canal, and several of its tributaries drain major parts of Pennsylvania's Coal Region. It fl ...

, for a total of 1,200 acres (4.8 km2). Streets were laid out in a gridiron system. Except for the two widest streets, High (now Market) and Broad

Broad(s) or The Broad(s) may refer to:

People

* A slang term for a woman.

* Broad (surname), a surname

Places

* Broad Peak, on the border between Pakistan and China, the 12th highest mountain on Earth

* The Broads, a network of mostly na ...

, the streets were named after prominent landowners who owned adjacent lots. The streets were renamed in 1684; the ones running east–west were named after local trees (Vine

A vine (Latin ''vīnea'' "grapevine", "vineyard", from ''vīnum'' "wine") is any plant with a growth habit of trailing or scandent (that is, climbing) stems, lianas or runners. The word ''vine'' can also refer to such stems or runners themselv ...

, Sassafras

''Sassafras'' is a genus of three extant and one extinct species of deciduous trees in the family Lauraceae, native to eastern North America and eastern Asia.Wolfe, Jack A. & Wehr, Wesley C. 1987. The sassafras is an ornamental tree. "Middle ...

, Mulberry

''Morus'', a genus of flowering plants in the family Moraceae, consists of diverse species of deciduous trees commonly known as mulberries, growing wild and under cultivation in many temperate world regions. Generally, the genus has 64 identif ...

, Cherry

A cherry is the fruit of many plants of the genus ''Prunus'', and is a fleshy drupe (stone fruit).

Commercial cherries are obtained from cultivars of several species, such as the sweet ''Prunus avium'' and the sour ''Prunus cerasus''. The nam ...

, Chestnut

The chestnuts are the deciduous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Castanea'', in the beech family Fagaceae. They are native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

The name also refers to the edible nuts they produce.

The unrelat ...

, Walnut

A walnut is the edible seed of a drupe of any tree of the genus ''Juglans'' (family Juglandaceae), particularly the Persian or English walnut, '' Juglans regia''.

Although culinarily considered a "nut" and used as such, it is not a true ...

, Locust, Spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal (taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the subfami ...

, Pine, Lombard, and Cedar

Cedar may refer to:

Trees and plants

*''Cedrus'', common English name cedar, an Old-World genus of coniferous trees in the plant family Pinaceae

*Cedar (plant), a list of trees and plants known as cedar

Places United States

* Cedar, Arizona

* ...

) and the north–south streets were numbered. Within the area, four squares (now named Rittenhouse, Logan, Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

and Franklin

Franklin may refer to:

People

* Franklin (given name)

* Franklin (surname)

* Franklin (class), a member of a historical English social class

Places Australia

* Franklin, Tasmania, a township

* Division of Franklin, federal electoral d ...

) were set aside as parks open for everyone. Penn designed a central square at the intersection of Broad and what is now Market Street to be surrounded by public buildings.

Some of the first settlers lived in caves dug out of the river bank, but the city grew with construction of homes, churches, and wharves. The new landowners did not share Penn's vision of a non-congested city. Most people bought land along the Delaware River instead of spreading westward towards the Schuylkill. The lots they bought were subdivided and resold with smaller streets constructed between them. Before 1704, few settlers lived west of Fourth Street.

Early growth

Philadelphia grew from a few hundred European inhabitants in 1683 to over 2,500 in 1701. The population was mostly English,Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

, Irish, Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

, Swedes, Finns

Finns or Finnish people ( fi, suomalaiset, ) are a Baltic Finnic ethnic group native to Finland.

Finns are traditionally divided into smaller regional groups that span several countries adjacent to Finland, both those who are native to these ...

, and Dutch. Before William Penn left Philadelphia for the last time on October 25, 1701, he issued the Charter of 1701. The charter established Philadelphia as a city and gave the mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well a ...

, aldermen

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members them ...

, and councilmen the authority to issue laws and ordinances and regulate markets and fairs. The first known Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

resident of Philadelphia was Jonas Aaron, a German who moved to the city in 1703. He is mentioned in an article entitled "A Philadelphia Business Directory of 1703," by Charles H. Browning. It was published in ''The American Historical Register,'' in April, 1895.

Philadelphia became an important trading center and major port. Initially the city's main source of trade was with the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

, which had established sugar cane plantations. It was part of the Triangle Trade, associated with Africa and Europe. During Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

(1702 and 1713) with the French, trade was cut off to the West Indies, hurting Philadelphia financially. The end of the war brought brief prosperity to all of overseas British possessions, but a depression in the 1720s stunted Philadelphia's growth. The 1720s and '30s saw immigration from mostly Germany and northern Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

to Philadelphia and the surrounding countryside. The region was developed for agriculture and Philadelphia exported grains, lumber products and flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

seeds to Europe and elsewhere in the American colonies; this pulled the city out of the depression.

Philadelphia's pledge of religious tolerance attracted many other religions beside Quakers. Mennonite

Mennonites are groups of Anabaptist Christian church communities of denominations. The name is derived from the founder of the movement, Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland. Through his writings about Reformed Christianity during the Radic ...

s, Pietists

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christianity, Christian life, including a social concern for ...

, Anglicans

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the l ...

, Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, and Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

moved to the city and soon outnumbered the Quakers, but they continued to be powerful economically and politically. Political tensions existed between and within the religious groups, which also had national connections. Riot

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property targete ...

s in 1741 and 1742 took place over high bread prices and drunken sailors. In October 1742 and the "Bloody Election" riots, sailors attacked Quakers and pacifist Germans, whose peace politics were strained by the War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

. The city was plagued by pickpockets and other petty criminals. Working in the city government had such a poor reputation that fines were imposed on citizens who refused to serve an office after being chosen. One man fled Philadelphia to avoid serving as mayor.

In the first half the 18th century, like other American cities, Philadelphia was dirty, with garbage and animals littering the streets. The roads were unpaved and in rainy seasons impassable. Early attempts to improve quality of life were ineffective as laws were poorly enforced. By the 1750s, Philadelphia was turning into a major city. Christ Church and the Pennsylvania State House, better known as Independence Hall

Independence Hall is a historic civic building in Philadelphia, where both the United States Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were debated and adopted by America's Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Fa ...

, were built. Streets were paved and illuminated with oil lamps. Philadelphia's first newspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide variety of fields such as politics, business, sports a ...

, Andrew Bradford

Andrew Bradford (1686 – November 24, 1742) was an early American printer in colonial Philadelphia. He published the first newspaper in Philadelphia, ''The American Weekly Mercury'', beginning in 1719, as well as the first magazine in America in ...

's ''American Weekly Mercury'', began publishing on December 22, 1719.

The city also developed culturally and scientifically. Schools, libraries and theaters were founded. James Logan arrived in Philadelphia in 1701 as a secretary for William Penn. He was the first to help establish Philadelphia as a place of culture and learning.''Insight Guides: Philadelphia and Surroundings'', p. 25 Logan, who was the mayor of Philadelphia in the early 1720s, created one of the largest libraries in the colonies. He also helped guide other prominent Philadelphia residents, which included botanist John Bartram and Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

. Benjamin Franklin arrived in Philadelphia in October 1723 and would play a large part in the city's development. To help protect the city from fire, Franklin founded the Union Fire Company Union Fire Company, sometimes called Franklin's Bucket Brigade, was a volunteer fire department formed in Philadelphia in 1736 with the assistance of Benjamin Franklin. It was the very first firefighting organization in Philadelphia, although it was ...

. In the 1750s Franklin was named one of the city's post master generals and he established postal routes between Philadelphia, New York, Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, and elsewhere. He helped raise money to build the American colonies' first hospital, which opened in 1752. That same year the College of Philadelphia

The Academy and College of Philadelphia (1749-1791) was a boys' school and men's college in Philadelphia, Colony of Pennsylvania.

Founded in 1749 by a group of local notables that included Benjamin Franklin, the Academy of Philadelphia began as ...

, another project of Franklin's, received its charter of incorporation. Threatened by French and Spanish privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s, Franklin and others set up a volunteer group for defense and built two batteries.

When the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

began in 1754 as part of the Seven Years' War, Franklin recruited militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s. During the war, the city attracted many refugees from the western frontier. When Pontiac's Rebellion

Pontiac's War (also known as Pontiac's Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of Native Americans dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War (1754–176 ...

occurred in 1763, refugees again fled into the city, including a group of Lenape hiding from other Native Americans, angry at their pacifism, and white frontiersmen. The Paxton Boys

The Paxton Boys were Pennsylvania's most aggressive colonists according to historian Kevin Kenny. While not many specifics are known about the individuals in the group their overall profile is clear. Paxton Boys Lived in hill country northwest of ...

tried to follow them into Philadelphia for attacks, but was prevented by the city's militia and Franklin, who convinced them to leave.

Revolution

In the 1760s, the

In the 1760s, the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative supremacy ...

's passage of the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts

The Townshend Acts () or Townshend Duties, were a series of British acts of Parliament passed during 1767 and 1768 introducing a series of taxes and regulations to fund administration of the British colonies in America. They are named after the ...

, combined with other frustrations, increased political tension and anger against Britain in the colonies. Philadelphia residents joined boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict som ...

s of British goods. After the Tea Act

The Tea Act 1773 (13 Geo 3 c 44) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. The principal objective was to reduce the massive amount of tea held by the financially troubled British East India Company in its London warehouses and to help th ...

in 1773, there were threats against anyone who would store tea and any ships that brought tea up the Delaware. After the Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell t ...

, a shipment of tea had arrived in December, on the ship the ''Polly''. A committee told the captain to depart without unloading his cargo.

A series of acts

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its message ...

in 1774 further angered the colonies; activists called for a general congress and they agreed to meet in Philadelphia. The First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from 12 of the 13 British colonies that became the United States. It met from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, after the British Navy ...

was held in September in Carpenters' Hall

Carpenters' Hall is the official birthplace of the Pennsylvania, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and a key meeting place in the early history of the United States. Carpenters' Hall is located in Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia, ...

. After the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

began in April 1775 following the Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord ...

, the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

met in May at the Pennsylvania State House. There they also met a year later to write and sign the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

in July 1776. Philadelphia was important to the war effort; Robert Morris said,

You will consider Philadelphia, from its centrical situation, the extent of its commerce, the number of its artificers, manufactures and other circumstances, to be to the United States what the heart is to the human body in circulating the blood.The port city was vulnerable to capture by the British by sea. Officials recruited soldiers and studied defenses for invasion from

Delaware Bay

Delaware Bay is the estuary outlet of the Delaware River on the northeast seaboard of the United States. It is approximately in area, the bay's freshwater mixes for many miles with the saltwater of the Atlantic Ocean.

The bay is bordered inlan ...

, but built no forts or other installations. In March 1776 two British frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

s began a blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

of the mouth of Delaware Bay; British soldiers were moving south through New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

from New York. In December fear of invasion caused half the population to flee the city, including the Continental Congress, which moved to Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

. General George Washington pushed back the British advance at the battles of Princeton and Trenton, and the refugees and Congress returned. In September 1777, the British invaded Philadelphia from the south. Washington intercepted them at the Battle of Brandywine

The Battle of Brandywine, also known as the Battle of Brandywine Creek, was fought between the American Continental Army of General George Washington and the British Army of General Sir William Howe on September 11, 1777, as part of the Ame ...

but was driven back.

Following Washington's defeat at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, thousands of Philadelphians fled north within Pennsylvania and east into New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

. Congress moved to Lancaster and then to York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

. Fearing the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

would seize the Liberty Bell

The Liberty Bell, previously called the State House Bell or Old State House Bell, is an iconic symbol of American independence, located in Philadelphia. Originally placed in the steeple of the Pennsylvania State House (now renamed Independence ...