History of Ontario on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

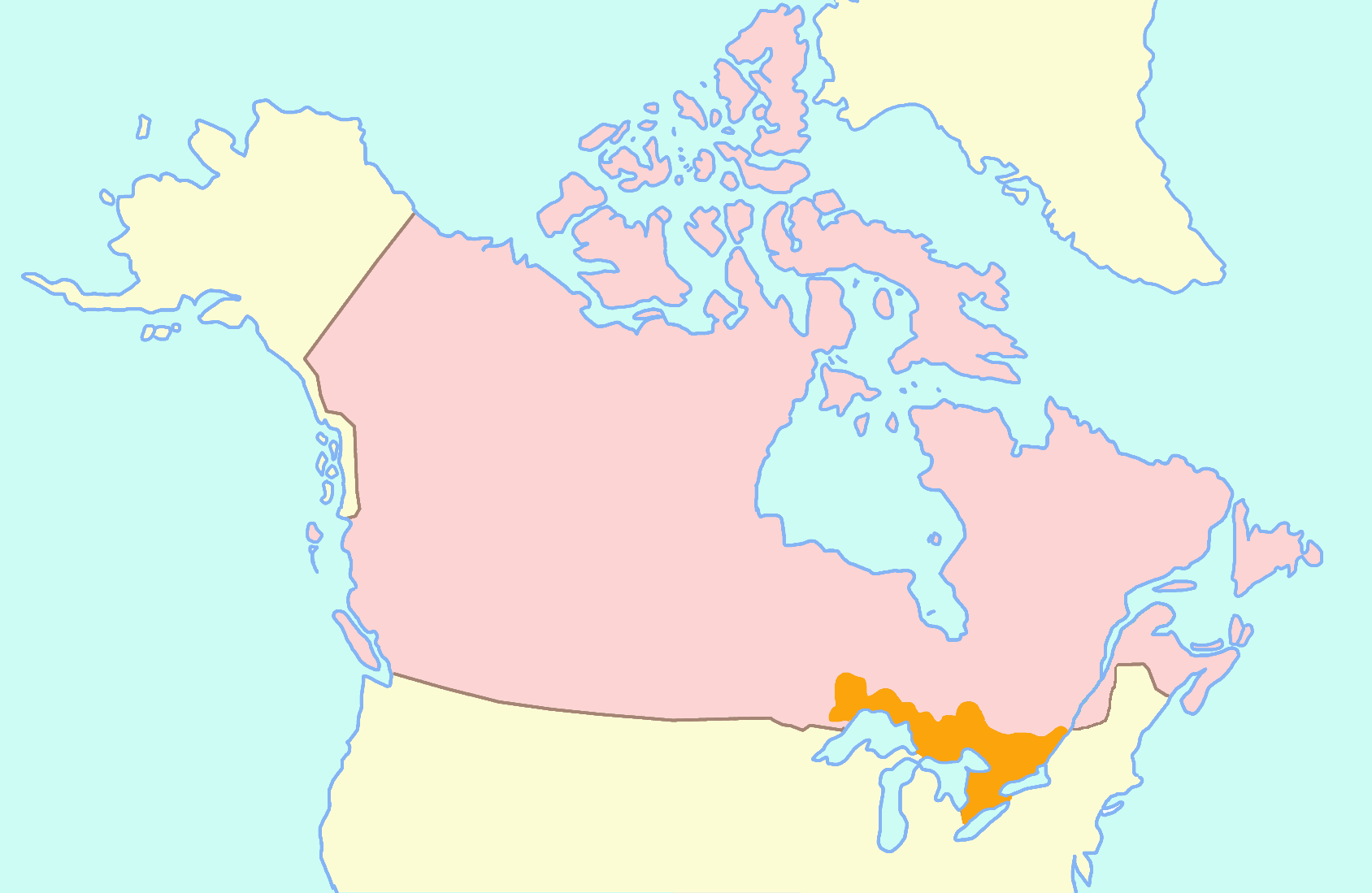

The history of Ontario covers the period from the arrival of Paleo-Indians thousands of years ago to the present day. The lands that make up present-day

The Woodland period directly followed the Archaic period. It saw the introduction of

The Woodland period directly followed the Archaic period. It saw the introduction of

French explorer

French explorer

The earliest offensives of the war took place near southwestern Ontario and the upper Great Lakes region, with American forces briefly crossing into present day southwestern Ontario, before a British-First Nations force launched an offensive into the Michigan Territory. However, on September 10, 1813, after the Americans gained control of

The earliest offensives of the war took place near southwestern Ontario and the upper Great Lakes region, with American forces briefly crossing into present day southwestern Ontario, before a British-First Nations force launched an offensive into the Michigan Territory. However, on September 10, 1813, after the Americans gained control of

After the War of 1812, relative stability attracted increasing numbers of immigrants from Britain and Ireland rather than from the United States. Colonial leaders encouraged this new immigration. However, many arriving newcomers from Europe (mostly from Britain and Ireland) found frontier life difficult, and some of those with the means eventually returned home or went south. But population growth far exceeded emigration from this area in the following decades.

Canal projects and a new network of plank roads spurred greater trade within the colony and with the United States, thereby improving relations over time. Ontario's numerous waterways aided travel and transportation into the interior and supplied water power for development. Canals were capital-intensive infrastructure projects that facilitated trade. The

After the War of 1812, relative stability attracted increasing numbers of immigrants from Britain and Ireland rather than from the United States. Colonial leaders encouraged this new immigration. However, many arriving newcomers from Europe (mostly from Britain and Ireland) found frontier life difficult, and some of those with the means eventually returned home or went south. But population growth far exceeded emigration from this area in the following decades.

Canal projects and a new network of plank roads spurred greater trade within the colony and with the United States, thereby improving relations over time. Ontario's numerous waterways aided travel and transportation into the interior and supplied water power for development. Canals were capital-intensive infrastructure projects that facilitated trade. The

Many men chafed against the anti-democratic

Many men chafed against the anti-democratic

Although both rebellions were put down in short order, the British government sent

Although both rebellions were put down in short order, the British government sent

Once constituted as a province, Ontario proceeded to assert its economic and legislative power. In 1872, the Liberal Party leader

Once constituted as a province, Ontario proceeded to assert its economic and legislative power. In 1872, the Liberal Party leader

Ontario large manufacturing and finance sectors waxed profitable in the late 19th century. Lucrative new markets opened up nationwide thanks to the federal government's high-tariff

Ontario large manufacturing and finance sectors waxed profitable in the late 19th century. Lucrative new markets opened up nationwide thanks to the federal government's high-tariff

Commercial wine production in the province began in the 1860s with an aristocrat from France, Count Justin McCarthy De Courtenay in County Peel. His success followed the realization that the right grapes could grow in the cold climate, producing an inexpensive good wine that could reach a commercial market. He gained government support and raised the capital for a commercial-scale vineyard and winery. His financial success encouraged others to enter the business.

Commercial wine production in the province began in the 1860s with an aristocrat from France, Count Justin McCarthy De Courtenay in County Peel. His success followed the realization that the right grapes could grow in the cold climate, producing an inexpensive good wine that could reach a commercial market. He gained government support and raised the capital for a commercial-scale vineyard and winery. His financial success encouraged others to enter the business.

Travellers commented on the class differentials in recreation, contrasting the gentrified masculinity of the British middle class and the rough-and-ready bush masculinity of the workers. Working-class audiences responded to cockfights, boxing matches, wrestling, and animal baiting. That was too bloody for gentlemen and army officers, who favoured games that promoted honour and built character. Middle-class sports, especially lacrosse and snowshoeing, evolved from military training.

Travellers commented on the class differentials in recreation, contrasting the gentrified masculinity of the British middle class and the rough-and-ready bush masculinity of the workers. Working-class audiences responded to cockfights, boxing matches, wrestling, and animal baiting. That was too bloody for gentlemen and army officers, who favoured games that promoted honour and built character. Middle-class sports, especially lacrosse and snowshoeing, evolved from military training.

The British element strongly supported the war with men, money and enthusiasm. So too did the Francophone element until it reversed position in 1915. Given Germany as one of the Axis Powers, the Canadian government was suspicious of the loyalty of residents of German descent, and anti-German sentiment escalated in the country. The City of Berlin was renamed Kitchener after Britain's top commander. Left-wing anti-war activists also came under attack. In 1917–1918 Isaac Bainbridge of Toronto, the dominion secretary of the Social Democratic Party of Canada and editor of its newspaper, ''Canadian Forward'', was charged three times with seditious libel and once with possession of seditious material; he was imprisoned twice.

The British element strongly supported the war with men, money and enthusiasm. So too did the Francophone element until it reversed position in 1915. Given Germany as one of the Axis Powers, the Canadian government was suspicious of the loyalty of residents of German descent, and anti-German sentiment escalated in the country. The City of Berlin was renamed Kitchener after Britain's top commander. Left-wing anti-war activists also came under attack. In 1917–1918 Isaac Bainbridge of Toronto, the dominion secretary of the Social Democratic Party of Canada and editor of its newspaper, ''Canadian Forward'', was charged three times with seditious libel and once with possession of seditious material; he was imprisoned twice.

Starting in the late 1870s the Ontario Woman's Christian Temperance Union (

Starting in the late 1870s the Ontario Woman's Christian Temperance Union (

Agriculture and industry alike suffered in the

Agriculture and industry alike suffered in the

Toronto replaced Montreal as the nation's premier business centre because the nationalist movement in Quebec, particularly with the success of the

Toronto replaced Montreal as the nation's premier business centre because the nationalist movement in Quebec, particularly with the success of the

The construction of roads and canals depended on numerous workers, whose wages often went to liquor, gambling, and women, all causes for fighting and rowdiness. Community leaders realized the traditional method of dealing with troublemakers one by one was inadequate, and they began to adopt less personal modernized procedures that followed imperial models of policing, trial, and punishment through the courts.

Toronto, Hamilton, Berlin (Kitchener), Windsor and other cities modernized and professionalized their public services in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. No service was changed more dramatically than the police. The introduction of emergency telephone call boxes linked to a central dispatcher, plus the use of bicycles, motorcycles, and automobiles, shifted the patrolman's duties from passively walking the beat to fast reaction to reported incidents, as well as handling automobile traffic. After 1930 the introduction of police radios speeded response times.

The construction of roads and canals depended on numerous workers, whose wages often went to liquor, gambling, and women, all causes for fighting and rowdiness. Community leaders realized the traditional method of dealing with troublemakers one by one was inadequate, and they began to adopt less personal modernized procedures that followed imperial models of policing, trial, and punishment through the courts.

Toronto, Hamilton, Berlin (Kitchener), Windsor and other cities modernized and professionalized their public services in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. No service was changed more dramatically than the police. The introduction of emergency telephone call boxes linked to a central dispatcher, plus the use of bicycles, motorcycles, and automobiles, shifted the patrolman's duties from passively walking the beat to fast reaction to reported incidents, as well as handling automobile traffic. After 1930 the introduction of police radios speeded response times.

The rapid spread of automobiles after 1910 and the building of roads, especially after 1920, opened up opportunities in remote rural areas to travel to the towns and cities for shopping and services. City people moved outward to suburbs. By the 1920s it was common for city folk to have a vacation cottage in remote lake areas. A stretch of the

The rapid spread of automobiles after 1910 and the building of roads, especially after 1920, opened up opportunities in remote rural areas to travel to the towns and cities for shopping and services. City people moved outward to suburbs. By the 1920s it was common for city folk to have a vacation cottage in remote lake areas. A stretch of the

online

short scholarly biographies of every major Canadian who died before 1930 * Baskerville, Peter A. ''Sites of Power: A Concise History of Ontario''. Oxford U. Press., 2005. 296 pp. (first edition was ''Ontario: Image, Identity and Power'', 2002)

online review

* Christou, Theodore Michael. ''Progressive Education: Revisioning and Reframing Ontario’s Public Schools, 1919–1942'' (2012) * Drummond, Ian M. ''Progress Without Planning: The Economic History of Ontario from Confederation to the Second World War'' (1987) * * Hall, Roger; Westfall, William; and MacDowell, Laurel Sefton, eds. ''Patterns of the Past: Interpreting Ontario's History''. Dundurn Pr., 1988. 406 pp

excerpt and text search

* McCalla, Douglas. ''Planting The Province: The Economic History of Upper Canada, 1784–1870'' (University of Toronto Press, 1993). 446 pp. * Mays, John Bentley. ''Arrivals: Stories from the History of Ontario''. Penguin Books Canada, 2002. 418 pp. * Schull, Joseph. ''Ontario since 1867'' (1978) 400pp; general survey emphasizing politics * Whitcomb, Dr. Ed. ''A Short History of Ontario''. (Ottawa. From Sea To Sea Enterprises, 2006) . 79 pp. * White, Randall. ''Ontario: 1610–1985'' (1985), general survey emphasizing politics * ''Celebrating One Thousand Years of Ontario's History: Proceedings of the Celebrating One Thousand Years of Ontario's History Symposium, April 14, 15, and 16, 2000''. (Ontario Historical Society, 2000) 343 pp.

Ontario Visual Heritage ProjectA collection of historical documents and primary sources about Ontario.

{{Canada History

Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central C ...

, the most populous province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman '' provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

as of the early 21st century have been inhabited for millennia by groups of Aboriginal people

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

, with French and British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

exploration and colonization commencing in the 17th century. Before the arrival of Europeans, the region was inhabited both by Algonquian ( Ojibwa, Cree and Algonquin

Algonquin or Algonquian—and the variation Algonki(a)n—may refer to:

Languages and peoples

*Algonquian languages, a large subfamily of Native American languages in a wide swath of eastern North America from Canada to Virginia

**Algonquin la ...

) and Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian ...

(Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

, Petun

The Petun (from french: pétun), also known as the Tobacco people or Tionontati ("People Among the Hills/Mountains"), were an indigenous Iroquoian people of the woodlands of eastern North America. Their last known traditional homeland was sou ...

and Huron

Huron may refer to:

People

* Wyandot people (or Wendat), indigenous to North America

* Wyandot language, spoken by them

* Huron-Wendat Nation, a Huron-Wendat First Nation with a community in Wendake, Quebec

* Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi ...

) tribes.

French explorer Étienne Brûlé

Étienne Brûlé (; – c. June 1633) was the first European explorer to journey beyond the St. Lawrence River into what is now known as Canada. He spent much of his early adult life among the Hurons, and mastered their language and learne ...

surveyed part of the area in 1610–12. The English explorer Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson ( 1565 – disappeared 23 June 1611) was an English sea explorer and navigator during the early 17th century, best known for his explorations of present-day Canada and parts of the northeastern United States.

In 1607 and 16 ...

sailed into Hudson Bay in 1611 and claimed the area for England, but Samuel de Champlain reached Lake Huron in 1615. In their effort to secure the North American fur trade, the English / British and the French established a number of fur trading forts in Ontario during the 17th and 18th centuries; with the former establishing a number of forts around Hudson Bay, and the latter establishing forts throughout the ''Pays d'en Haut

The ''Pays d'en Haut'' (; ''Upper Country'') was a territory of New France covering the regions of North America located west of Montreal. The vast territory included most of the Great Lakes region, expanding west and south over time into the ...

'' region. Control over the area remained contested until the end of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

, when the 1763 Treaty of Paris awarded the colony of New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

to the British.

Following the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, the province saw an influx of loyalist settle the area. In response to the influx of loyalist refugees, the ''Constitutional Act of 1791

The Clergy Endowments (Canada) Act 1791, commonly known as the Constitutional Act 1791 (), was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which passed under George III. The current short title has been in use since 1896.

History

The act refor ...

'' was enacted, splitting the colony of Quebec into Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec an ...

(present day southern Quebec) and Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of th ...

(present day southern Ontario). The Canadas

The Canadas is the collective name for the provinces of Lower Canada and Upper Canada, two historical British colonies in present-day Canada. The two colonies were formed in 1791, when the British Parliament passed the '' Constitutional Act'', ...

were reunited as the Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on th ...

by the ''Act of Union 1840

The ''British North America Act, 1840'' (3 & 4 Victoria, c.35), also known as the ''Act of Union 1840'', (the ''Act'') was approved by Parliament in July 1840 and proclaimed February 10, 1841, in Montreal. It abolished the legislatures of Lower ...

''. On July 1, 1867, the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia were united to form a single federation. The Province of Canada was split into two provinces at Confederation, with the area east of the Ottawa River forming Quebec, and the area west of the river forming Ontario.

Woodland period

The Woodland period directly followed the Archaic period. It saw the introduction of

The Woodland period directly followed the Archaic period. It saw the introduction of ceramics

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcelain ...

in the Early Woodland period, horticultural experimentation with different crops (notably maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. The ...

, or corn) as well as elaborate burial ceremonialism during the Middle Woodland, and the emergence of agriculture and village settlements by the Late Woodland. Especially by the Late Woodland, there was a divergence between northern and southern Ontario, as agriculture only took place in southern Ontario. However, northern Ontario saw significant changes in pottery and a continuation of mound building practices. Pictograph

A pictogram, also called a pictogramme, pictograph, or simply picto, and in computer usage an icon, is a graphic symbol that conveys its meaning through its pictorial resemblance to a physical object. Pictographs are often used in writing and g ...

s are associated with the Late Woodland, and continue as a practice into the time following European arrival, with the appearance of pictographs representing horses, firearms, and ships.

By at least the latter part of the Woodland period, a number of indigenous societies formed a broad fabric of ethnic groups, some of which were politically organized as confederacies. In the territory of modern-day Ontario, examples of these include the interconnected Huron

Huron may refer to:

People

* Wyandot people (or Wendat), indigenous to North America

* Wyandot language, spoken by them

* Huron-Wendat Nation, a Huron-Wendat First Nation with a community in Wendake, Quebec

* Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi ...

, Petun

The Petun (from french: pétun), also known as the Tobacco people or Tionontati ("People Among the Hills/Mountains"), were an indigenous Iroquoian people of the woodlands of eastern North America. Their last known traditional homeland was sou ...

, and Neutral

Neutral or neutrality may refer to:

Mathematics and natural science Biology

* Neutral organisms, in ecology, those that obey the unified neutral theory of biodiversity

Chemistry and physics

* Neutralization (chemistry), a chemical reaction in ...

confederacies. These Northern Iroquoian peoples were more distantly related to the Iroquois Confederacy to the south. The territory was also inhabited by Algonquian peoples such as the Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

, Cree, and Algonquin

Algonquin or Algonquian—and the variation Algonki(a)n—may refer to:

Languages and peoples

*Algonquian languages, a large subfamily of Native American languages in a wide swath of eastern North America from Canada to Virginia

**Algonquin la ...

.

Arrival of Europeans

French explorer

French explorer Étienne Brûlé

Étienne Brûlé (; – c. June 1633) was the first European explorer to journey beyond the St. Lawrence River into what is now known as Canada. He spent much of his early adult life among the Hurons, and mastered their language and learne ...

surveyed part of the area in 1610–12. The English explorer Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson ( 1565 – disappeared 23 June 1611) was an English sea explorer and navigator during the early 17th century, best known for his explorations of present-day Canada and parts of the northeastern United States.

In 1607 and 16 ...

sailed into Hudson Bay in 1611 and claimed the area for England, but Samuel de Champlain reached Lake Huron in 1615. French Jesuit missionaries began to establish posts along the Great Lakes, forging alliances in particular with the Huron people

The Wyandot people, or Wyandotte and Waⁿdát, are Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. The Wyandot are Iroquoian Indigenous peoples of North America who emerged as a confederacy of tribes around the north shore of Lake Ontario wi ...

. Permanent French settlement was hampered by their hostilities with the Five Nations of the Iroquois (based in New York State), who became allied with the British. By the early 1650s, using both British and Dutch arms, they had succeeded in pushing other related Iroquoian-speaking peoples, the Petun and Neutral Nation, out of or to the fringes of territorial southern Ontario. In 1747 a small number of French settlers established the oldest continually inhabited European community in what became western Ontario; ''Petite Côte'' was settled on the south bank of the Detroit River across from Fort Detroit and near Huron and Petun villages.

The British established trading posts on Hudson Bay in the late 17th century and began a struggle for domination of Ontario. With their victory in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

, the 1763 Treaty of Paris awarded nearly all of France's North American possessions (New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

) to Britain.

The region was annexed to Quebec in 1774. The first English settlements were in 1782–1784, when 5,000 American loyalists

Loyalists were colonists in the Thirteen Colonies who remained loyal to the British Crown during the American Revolutionary War, often referred to as Tories, Royalists or King's Men at the time. They were opposed by the Patriots, who support ...

entered what is now Ontario following the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. From 1783 to 1796, Britain granted individuals 200 acres (0.8 km2) of land per household and other items as compensation for their losses in the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

and a start for rebuilding their lives. This resettlement substantially increased the European population of Canada west of the St. Lawrence-Ottawa River confluence during this period.

1791–1867

Upper Canada

The Constitutional Act of 1791 recognized this development, as it split theProvince of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen p ...

into the Canadas

The Canadas is the collective name for the provinces of Lower Canada and Upper Canada, two historical British colonies in present-day Canada. The two colonies were formed in 1791, when the British Parliament passed the '' Constitutional Act'', ...

, Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec an ...

east of the St. Lawrence-Ottawa River confluence, the area of earliest settlement; and Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of th ...

southwest of the confluence. John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe (25 February 1752 – 26 October 1806) was a British Army general and the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 until 1796 in southern Ontario and the watersheds of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior. He founded Yor ...

was appointed Upper Canada's first Lieutenant-Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a " second-in-com ...

in 1793. War of 1812

Owing to grievances from theimpressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

of American sailors by the British, and suspected British support of Native Americans in the American Northwest Territory, the United States declared war on the United Kingdom on July 1, 1812. Given its proximity to the United States, colonies in British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

, including Upper Canada found itself an active theatre of war throughout most of the conflict.

The earliest offensives of the war took place near southwestern Ontario and the upper Great Lakes region, with American forces briefly crossing into present day southwestern Ontario, before a British-First Nations force launched an offensive into the Michigan Territory. However, on September 10, 1813, after the Americans gained control of

The earliest offensives of the war took place near southwestern Ontario and the upper Great Lakes region, with American forces briefly crossing into present day southwestern Ontario, before a British-First Nations force launched an offensive into the Michigan Territory. However, on September 10, 1813, after the Americans gained control of Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also h ...

, British forces evacuated Detroit, and eventually decided to withdraw from the entire area. American forces under William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

caught up to the retreating British-First Nations force, decisively defeating them at the Battle of the Thames

The Battle of the Thames , also known as the Battle of Moraviantown, was an American victory in the War of 1812 against Tecumseh's Confederacy and their British allies. It took place on October 5, 1813, in Upper Canada, near Chatham. The Britis ...

. Tecumseh, leader of a First Nations confederation, was killed shortly after the remaining British forces decided to fall back to Burlington; disrupting the military alliance between British and First Nations.

Several invasion attempts by American forces were also attempted at the Niagara Peninsula. On October 13, 1812, an American invasion attempt was prevented at the Battle of Queenston Heights; although the commander of British forces in Upper Canada, Major-General Isaac Brock

Major-General Sir Isaac Brock KB (6 October 1769 – 13 October 1812) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Guernsey. Brock was assigned to Lower Canada in 1802. Despite facing desertions and near-mutinies, he c ...

, was killed during the battle. On April 27, 1813, American forces raided and briefly occupied York, the capital of Upper Canada. A month later, American forces captured Fort George prompting the British to retreat to the Burlington Heights. However, further advances into the peninsula by American forces were halted at the battles of Stoney Creek and Beaver Dams

A beaver dam or beaver impoundment is a dam built by beavers to create a pond which protects against predators such as coyotes, wolves and bears, and holds their food during winter. These structures modify the natural environment in such a way t ...

; prompting the Americans to eventual withdraw from the peninsula on December 10, 1813. An American invasion force advancing towards Montreal was also repulsed at the Battle of Chrysler's Farm on November 13, 1813.

In the summer of 1814, the Americans conducted another invasion of the Niagara Peninsula, successfully defeating the British at the Battle of Chippewa. However, American forces were prompted to withdraw to Fort Erie

Fort Erie is a town on the Niagara River in the Niagara Region, Ontario, Canada. It is directly across the river from Buffalo, New York, and is the site of Old Fort Erie which played a prominent role in the War of 1812.

Fort Erie is one of Ni ...

following the Battle of Lundy's Lane on July 25, 1814. American forces managed to repulse a British siege of the fort, although the Americans evacuated the fort shortly after the siege was over in November 1814. Transgressions conducted by American occupying forces while in Upper Canada, including the burning of York

The Battle of York was a War of 1812 battle fought in York, Upper Canada (today's Toronto, Ontario, Canada) on April 27, 1813. An American force supported by a naval flotilla landed on the lakeshore to the west and advanced against the town, whi ...

and the raid on Port Dover later influenced the actions of British commanders in other theatres of the war, most notably the burning of Buffalo and Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

. The conflict was concluded in December 1814 with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

.

Transportation

After the War of 1812, relative stability attracted increasing numbers of immigrants from Britain and Ireland rather than from the United States. Colonial leaders encouraged this new immigration. However, many arriving newcomers from Europe (mostly from Britain and Ireland) found frontier life difficult, and some of those with the means eventually returned home or went south. But population growth far exceeded emigration from this area in the following decades.

Canal projects and a new network of plank roads spurred greater trade within the colony and with the United States, thereby improving relations over time. Ontario's numerous waterways aided travel and transportation into the interior and supplied water power for development. Canals were capital-intensive infrastructure projects that facilitated trade. The

After the War of 1812, relative stability attracted increasing numbers of immigrants from Britain and Ireland rather than from the United States. Colonial leaders encouraged this new immigration. However, many arriving newcomers from Europe (mostly from Britain and Ireland) found frontier life difficult, and some of those with the means eventually returned home or went south. But population growth far exceeded emigration from this area in the following decades.

Canal projects and a new network of plank roads spurred greater trade within the colony and with the United States, thereby improving relations over time. Ontario's numerous waterways aided travel and transportation into the interior and supplied water power for development. Canals were capital-intensive infrastructure projects that facilitated trade. The Oswego Canal

The Oswego Canal is a canal in the New York State Canal System located in New York, United States. Opened in 1828, it is 23.7 miles (38.1 km) in length, and connects the Erie Canal at Three Rivers (near Liverpool) to Lake Ontario at Oswe ...

, built in New York 1825–1829, was a vital commercial link in the Great Lakes–Atlantic seaway. It was connected to Ontario's Welland Canal

The Welland Canal is a ship canal in Ontario, Canada, connecting Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. It forms a key section of the St. Lawrence Seaway and Great Lakes Waterway. Traversing the Niagara Peninsula from Port Weller in St. Catharines ...

in 1829. The newly fashioned Oswego–Welland line offered an alternate route to the St. Lawrence River and Europe, as opposed to the Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east-west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, vastly reducing t ...

, which connected the Great Lakes to New York City via the Mohawk and Hudson rivers.

Family Compact

In the absence of a hereditary aristocracy, Upper Canada was run by an oligarchy or closed group of powerful men who controlled most of the political, judicial, and economic power from the 1810s to the 1830s. Opponents called it the "Family Compact", but its members avoided the term. In the religious sphere, a key leader wasJohn Strachan

John Strachan (; 12 April 1778 – 1 November 1867) was a notable figure in Upper Canada and the first Anglican Bishop of Toronto. He is best known as a political bishop who held many government positions and promoted education from common sc ...

(1778–1867), the Anglican bishop of Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

. Strachan (and the Family Compact generally) was opposed by Methodist leader Egerton Ryerson (1803–1882). The Family Compact consisted of English gentry who arrived before 1800, and the sons of United Empire Loyalists

United Empire Loyalists (or simply Loyalists) is an honorific title which was first given by the 1st Lord Dorchester, the Governor of Quebec, and Governor General of The Canadas, to American Loyalists who resettled in British North America dur ...

, who were exiles who fled the American revolution. The term "family" was metaphorical, for they generally were not related by blood or marriage. There were no elections and the leadership controlled appointments, so local officials were generally allies of the leaders.Peter A. Baskerville, "Entrepreneurship and the Family Compact: York-Toronto, 1822–55", ''Urban History Review'' Feb 1981, Vol. 9 Issue 3, pp 15–34

The Family Compact looked to Britain for the ideal model of society, where landed aristocrats held power. The Family Compact was noted for its conservatism and opposition to democracy, especially the rowdy United States version. They developed the theme that they and their militia had defeated American attempts to annex Canada in the War of 1812. They were based in Toronto, and were integrated with the bankers, merchants, and financiers of the city, and were active in promoting canals and railroads.

Rebellion

Many men chafed against the anti-democratic

Many men chafed against the anti-democratic Family Compact

The Family Compact was a small closed group of men who exercised most of the political, economic and judicial power in Upper Canada (today’s Ontario) from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was the Upper Canadian equivalent of the Château Clique in ...

that governed through personal connections among the elite, which controlled the best lands. This resentment spurred republican ideals and sowed the seeds for early Canadian nationalism. Accordingly, rebellion in favour of responsible government rose in both regions; Louis-Joseph Papineau

Louis-Joseph Papineau (October 7, 1786 – September 23, 1871), born in Montreal, Quebec, was a politician, lawyer, and the landlord of the ''seigneurie de la Petite-Nation''. He was the leader of the reformist Patriote movement before the Low ...

led the Lower Canada Rebellion

The Lower Canada Rebellion (french: rébellion du Bas-Canada), commonly referred to as the Patriots' War () in French, is the name given to the armed conflict in 1837–38 between rebels and the colonial government of Lower Canada (now south ...

and William Lyon Mackenzie

William Lyon Mackenzie (March12, 1795 August28, 1861) was a Scottish Canadian-American journalist and politician. He founded newspapers critical of the Family Compact, a term used to identify elite members of Upper Canada. He represented Yor ...

led the Upper Canada Rebellion. The rebellions

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

failed but there were long-term changes that resolved the issue.

Canada West

Although both rebellions were put down in short order, the British government sent

Although both rebellions were put down in short order, the British government sent Lord Durham

Earl of Durham is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1833 for the Whig politician and colonial official John Lambton, 1st Baron Durham. Known as "Radical Jack", he played a leading role in the passing of the Gr ...

to investigate the causes of the unrest. He recommended that self-government be granted and that Lower and Upper Canada be re-joined in an attempt to assimilate the French Canadians. Accordingly, the two colonies were merged into the Province of Canada by the ''Act of Union (1840)

The ''British North America Act, 1840'' (3 & 4 Victoria, c.35), also known as the ''Act of Union 1840'', (the ''Act'') was approved by Parliament in July 1840 and proclaimed February 10, 1841, in Montreal. It abolished the legislatures of Lower ...

'', with the capital at Kingston, and Upper Canada becoming known as Canada West

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the ...

. Parliamentary self-government was granted in 1848.

Due to waves of increased immigration in the 1840s, the population of Canada West more than doubled by 1851 over the previous decade. As a result, for the first time the English-speaking population of Canada West surpassed the French-speaking population of Canada East, tilting the representative balance of power.

An economic boom in the 1850s, brought on by factors such as a free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

agreement with the United States, coincided with massive railway expansion across the province, furthering the economic strength of Central Canada, pre-confederation.

Confederation and the late-19th century

A political stalemate between the French- and English-speaking legislators, as well as fear of aggression from the United States during theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, led the political elite to hold a series of conferences in the 1860s to effect a broader federal union of all British North American colonies. The '' British North America Act'' took effect on July 1, 1867, establishing the Dominion of Canada, initially with four provinces: Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

, Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

, and Ontario. The Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on th ...

was divided at this point into Ontario and Quebec so that each major European linguistic group would have its own province.

Both Quebec and Ontario were required by section 93 of the BNA Act to safeguard existing educational rights and privileges of the relative Protestant and Catholic minorities. Thus, separate Catholic schools and school boards were permitted in Ontario. However, neither province had a constitutional requirement to protect its French- or English-speaking minority. Toronto was formally established as Ontario's provincial capital at this time.

Once constituted as a province, Ontario proceeded to assert its economic and legislative power. In 1872, the Liberal Party leader

Once constituted as a province, Ontario proceeded to assert its economic and legislative power. In 1872, the Liberal Party leader Oliver Mowat

Sir Oliver Mowat (July 22, 1820 – April 19, 1903) was a Canadian lawyer, politician, and Ontario Liberal Party leader. He served for nearly 24 years as the third premier of Ontario. He was the eighth lieutenant governor of Ontario and one of ...

became premier, and remained as premier until 1896, despite Conservative control in Ottawa. Mowat fought for provincial rights, weakening the power of the federal government in provincial matters, usually through well-argued appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is the highest court of appeal for the Crown Dependencies, the British Overseas Territories, some Commonwealth countries and a few institutions in the United Kingdom. Established on 14 Aug ...

. His battles with the federal government greatly decentralized Canada, giving the provinces far more power than Prime Minister John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (January 10 or 11, 1815 – June 6, 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 to 1891. The dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, he had a political career that sp ...

had intended.

Mowat consolidated and expanded Ontario's educational and provincial institutions, created districts in Northern Ontario

Northern Ontario is a primary geographic and quasi-administrative region of the Canadian province of Ontario, the other primary region being Southern Ontario. Most of the core geographic region is located on part of the Superior Geological Pro ...

, and fought tenaciously to ensure that those parts of Northwestern Ontario not historically part of Upper Canada (the vast areas north and west of the Lake Superior-Hudson Bay watershed, known as the District of Keewatin) would become part of Ontario, a victory embodied in the ''Canada (Ontario Boundary) Act, 1889''. He also presided over the emergence of the province into the economic powerhouse of Canada. Mowat was the creator of what is often called ''Empire Ontario''.

The boundary between Ontario and Manitoba became a hotly contested matter, with the federal government attempting to extend Manitoba's jurisdiction eastward to the Great Lakes, into the areas claimed by Ontario. In 1882 Premier Mowat threatened to pull Ontario from Confederation over the issue. Mowat sent police into the disputed territory to assert Ontario's claims, while Manitoba (at the behest of the national government) did the same. The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is the highest court of appeal for the Crown Dependencies, the British Overseas Territories, some Commonwealth countries and a few institutions in the United Kingdom. Established on 14 Aug ...

in Britain, serving as Canada's highest appeal court, repeatedly issued rulings taking the side of provincial rights. These decisions would to some extent neutralize the power of the central government, creating a more decentralized federation.

John Ibbitson writes that by 1914:

:Confederation had evolved into a creation beyond John A. Macdonald's worst nightmare. Powerful, independent provinces, sovereign within their own spheres, manipulated the rights of property, levied their own taxes—even income taxes, in a few cases—exploited their natural resources, and managed schools, hospitals, and relief for the poor, while a weak and ineffectual central government presided over not much of anything in the drab little capital on the banks of the Ottawa.

Meanwhile, Ontario's Conservative Party leader William Ralph Meredith

Sir William Ralph Meredith, (March 31, 1840 – August 21, 1923) was a Canadian lawyer, politician and judge. He served as Leader of the Ontario Conservatives from 1878 to 1894, Chancellor of the University of Toronto from 1900 until his de ...

had difficulty balancing the province's particular interests with his national party's centralism. Meredith was further undercut by lack of support from the national Conservative party and his own elitist aversion to popular politics at the provincial level.

In the 1894 election, the main issues were the Liberals' "Ontario System", as well as opposition to French language schools and a rise in anti-Catholicism (led by the Protestant Protective Association (PPA)); farmer interests as expressed by the new Patrons of Industry; support for Toronto business, woman suffrage, and the temperance movement; and the demands of labour unions. Mowat and the Liberals maintained their large majority in the assembly.

Economic development

Transportation

As the population increased, so did the industries and transportation networks, which in turn led to further development. By the end of the 19th century, Ontario vied with Quebec as the nation's leader in terms of growth in population, industry, arts, and communications. Ontario large manufacturing and finance sectors waxed profitable in the late 19th century. Lucrative new markets opened up nationwide thanks to the federal government's high-tariff

Ontario large manufacturing and finance sectors waxed profitable in the late 19th century. Lucrative new markets opened up nationwide thanks to the federal government's high-tariff National Policy

The National Policy was a Canadian economic program introduced by John A. Macdonald's Conservative Party in 1876. After Macdonald led the Conservatives to victory in the 1878 Canadian federal election, he began implementing his policy in 1879. Th ...

after 1879, which limited competition from the United States. New markets out west opened after construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (1875–1885) through Northern Ontario

Northern Ontario is a primary geographic and quasi-administrative region of the Canadian province of Ontario, the other primary region being Southern Ontario. Most of the core geographic region is located on part of the Superior Geological Pro ...

to the Prairies

Prairies are ecosystems considered part of the temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome by ecologists, based on similar temperate climates, moderate rainfall, and a composition of grasses, herbs, and shrubs, rather than trees, as the ...

and British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

. Tens of thousands of European immigrants, as well as native Canadians, moved west along the railroad in order to acquire land and set up new farms. They shipped their wheat east and bought from local merchants who placed orders with Ontario wholesalers, especially those based in Toronto.

Farming

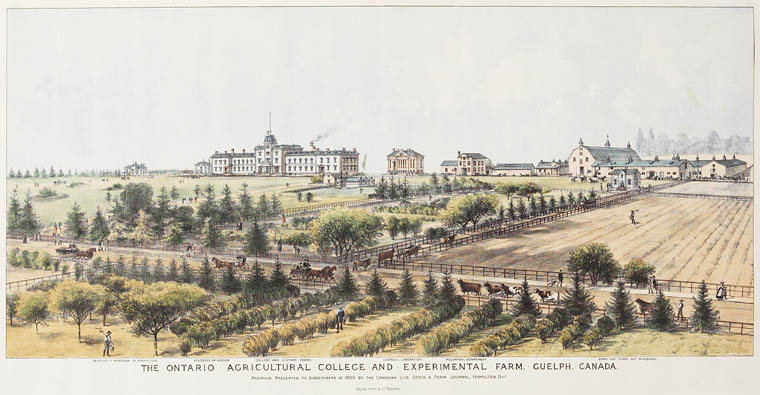

Farming was generally quite profitable, especially after 1896. The major changes involved mechanization of technology and a shift toward high-profit, high-quality consumer products, such as milk, eggs, and vegetables, for the fast-growing urban markets. It took farmers a half century to appreciate the value of high-protein soybean crops. Introduced in the 1890s, acceptance was slow until 1943–52, when farmers in the southwestern counties expanded production. Farmers increasingly demanded more information on the best farming techniques. Their demands led to farm magazine and agricultural fairs. In 1868 the assembly created an agricultural museum, which developed as theOntario Agricultural College

The Ontario Agricultural College (OAC) originated at the agricultural laboratories of the Toronto Normal School, and was officially founded in 1874 as an associate agricultural college of the University of Toronto. Since 1964, it has become affili ...

in Guelph in 1874.

Commercial wine production in the province began in the 1860s with an aristocrat from France, Count Justin McCarthy De Courtenay in County Peel. His success followed the realization that the right grapes could grow in the cold climate, producing an inexpensive good wine that could reach a commercial market. He gained government support and raised the capital for a commercial-scale vineyard and winery. His financial success encouraged others to enter the business.

Commercial wine production in the province began in the 1860s with an aristocrat from France, Count Justin McCarthy De Courtenay in County Peel. His success followed the realization that the right grapes could grow in the cold climate, producing an inexpensive good wine that could reach a commercial market. He gained government support and raised the capital for a commercial-scale vineyard and winery. His financial success encouraged others to enter the business.

Social welfare

The care of illegitimate children was a high priority for private charities. Before 1893, the Ontario government appropriated grants to charitable infants' homes for the infants and for their nursing mothers. Most of these infants were illegitimate, and most of their mothers were poor. Many babies were admitted to the homes in poor physical condition, so that their chances of survival outside such homes was poor.Culture

Religion

The changes in the next generation in the town of Woodstock in southwestern Ontario exemplified the shift of power from the Tory elite to middle-class merchants and professionals. The once-unquestioned leadership of the magistracy and the Anglican Church, with their closed interlocking networks of patron-client relations, faded year by year as modern ideas of respectability based on merit and economic development grew apace. The new middle class was solidly in control by the 1870s, and the old elite had all but vanished. While Anglicans consolidated their hold on the upper classes, workingmen and farmers responded to the Methodist revivals, often sponsored by visiting preachers from the United States. Typical was Rev. James Caughey, an American sent by the Wesleyan Methodist Church from the 1840s through 1864. He brought in the converts by the score, most notably in the revivals in Canada West 1851–53. His technique combined restrained emotionalism with a call for personal commitment, coupled with follow-up action to organize support from converts. It was a time when the Holiness Movement caught fire, with the revitalized interest of men and women in Christian perfection. Caughey bridged the gap between the style of earliercamp meeting

The camp meeting is a form of Protestant Christian religious service originating in England and Scotland as an evangelical event in association with the communion season. It was held for worship, preaching and communion on the American frontier ...

s and the needs of more sophisticated Methodist congregations in the emerging cities.

Sport and recreation

Travellers commented on the class differentials in recreation, contrasting the gentrified masculinity of the British middle class and the rough-and-ready bush masculinity of the workers. Working-class audiences responded to cockfights, boxing matches, wrestling, and animal baiting. That was too bloody for gentlemen and army officers, who favoured games that promoted honour and built character. Middle-class sports, especially lacrosse and snowshoeing, evolved from military training.

Travellers commented on the class differentials in recreation, contrasting the gentrified masculinity of the British middle class and the rough-and-ready bush masculinity of the workers. Working-class audiences responded to cockfights, boxing matches, wrestling, and animal baiting. That was too bloody for gentlemen and army officers, who favoured games that promoted honour and built character. Middle-class sports, especially lacrosse and snowshoeing, evolved from military training. Ice hockey

Ice hockey (or simply hockey) is a team sport played on ice skates, usually on an ice skating rink with lines and markings specific to the sport. It belongs to a family of sports called hockey. In ice hockey, two opposing teams use ice h ...

proved a success among both refined gentlemen and bloodthirsty labourers.

The ideals promulgated by English author and reformer Thomas Hughes

Thomas Hughes (20 October 182222 March 1896) was an English lawyer, judge, politician and author. He is most famous for his novel ''Tom Brown's School Days'' (1857), a semi-autobiographical work set at Rugby School, which Hughes had attended. ...

, especially as expressed in ''Tom Brown's Schooldays'' (1857), gave the middle class a model for sports that provided moral education and training for citizenship. Late in the 19th century, the Social Gospel themes of muscular Christianity were influential, as in the invention of basketball in 1891 by James Naismith

James Naismith (; November 6, 1861November 28, 1939) was a Canadian-American physical educator, physician, Christian chaplain, and sports coach, best known as the inventor of the game of basketball. After moving to the United States, he wrote ...

, an Ontarian employed at the International Young Men's Christian Association

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

Training School in Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

. Outside of sports, the social and moral agendas behind muscular Christianity influenced numerous reform movements, thus linking it to the political left in Canada.

Medicine

Numerous local rivalries had to be overcome before physicians could form a single, self-regulating, and unified medical body for licensing and educating practitioners. Professionalization began with the first medical board in 1818, and an 1827 act that required all doctors to be licensed. From the 1840s on, the number of new doctors with medical degrees increased rapidly because of legislation and the establishment of local medical schools. The Ontario College of Physicians and Surgeons was chartered in 1869. As physicians became better organized, they gained passage of laws controlling the practice of medicine and pharmacy, and banning marginal and traditional practitioners.Midwifery

Midwifery is the health science and health profession that deals with pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period (including care of the newborn), in addition to the sexual and reproductive health of women throughout their lives. In many ...

—practised along traditional lines by women—was restricted and practically died out by 1900. Even so, the great majority of childbirths took place at home until the 1920s, when hospitals became preferred, especially by women who were better educated, wealthier and more modern, and more trusting of modern medicine.

20th century

In 1912,Regulation 17

Regulation 17 (french: Règlement 17) was a regulation of the Government of Ontario, Canada, designed to limit instruction in French-language Catholic separate schools. The regulation was written by the Ministry of Education and was issued in July ...

was a regulation introduced by the government of Ontario designed to shut down French-language schools at a time that Francophones from Quebec were moving into eastern Ontario. In July 1912, the Conservative government of Sir James P. Whitney issued Regulation 17, which severely limited the provision of French-language schooling to the province's French-speaking minority. French could only be used in the first two years of schooling, and after that students and teachers were required to use English in classrooms. Few of the teachers at the French-language schools were fluent in English, so the schools had to close. The French-Canadian population, which was growing rapidly in eastern Ontario from migration, reacted with outrage; journalist Henri Bourassa

Joseph-Napoléon-Henri Bourassa (; September 1, 1868 – August 31, 1952) was a French Canadian political leader and publisher. In 1899, Bourassa was outspoken against the British government's request for Canada to send a militia to fight for ...

denounced the "Prussians of Ontario". With the Great War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

raging, Anglophones were insulted by the comparison. The restriction on French- language schools contributed to the Francophones turning away from the war effort in 1915 and refusing to enlist. But, most of Ontario's Catholics were Irish, led by Irish Bishop Fallon, who united with the Protestants in opposing French schools. The government repealed Regulation 17 in 1927. Ontario has no official language, but English is considered the ''de facto'' language. Numerous French language services are available under the French Language Services Act

The ''French Language Services Act'' (french: Loi sur les services en français) (the ''Act'') is a law in the province of Ontario, Canada which is intended to protect the rights of Franco-Ontarians, or French-speaking people, in the province.

T ...

of 1990 in designated areas where sizable francophone populations exist.

World War I

The British element strongly supported the war with men, money and enthusiasm. So too did the Francophone element until it reversed position in 1915. Given Germany as one of the Axis Powers, the Canadian government was suspicious of the loyalty of residents of German descent, and anti-German sentiment escalated in the country. The City of Berlin was renamed Kitchener after Britain's top commander. Left-wing anti-war activists also came under attack. In 1917–1918 Isaac Bainbridge of Toronto, the dominion secretary of the Social Democratic Party of Canada and editor of its newspaper, ''Canadian Forward'', was charged three times with seditious libel and once with possession of seditious material; he was imprisoned twice.

The British element strongly supported the war with men, money and enthusiasm. So too did the Francophone element until it reversed position in 1915. Given Germany as one of the Axis Powers, the Canadian government was suspicious of the loyalty of residents of German descent, and anti-German sentiment escalated in the country. The City of Berlin was renamed Kitchener after Britain's top commander. Left-wing anti-war activists also came under attack. In 1917–1918 Isaac Bainbridge of Toronto, the dominion secretary of the Social Democratic Party of Canada and editor of its newspaper, ''Canadian Forward'', was charged three times with seditious libel and once with possession of seditious material; he was imprisoned twice.

1920s

Premier Hearst had a number of progressive ideas planned for his next term, but his Conservatives were swept from power in 1919 by a totally new farmer's party. TheUnited Farmers of Ontario

The United Farmers of Ontario (UFO) was an agrarian and populist provincial political party in Ontario, Canada. It was the Ontario provincial branch of the United Farmers movement of the early part of the 20th century.

History

Foundation and r ...

, with 45 seats, formed a bare majority coalition with the trades union party, known as the "Ontario Independent Labour Party", with 11 seats. They selected farm leader Ernest Drury

Ernest Charles Drury (January 22, 1878 – February 17, 1968) was a farmer, politician and writer who served as the eighth premier of Ontario, from 1919 to 1923 as the head of a United Farmers of Ontario– Labour coalition government ...

as premier, enforced prohibition, passed a mother's pension and minimum wage which Hearst had proposed, and promoted good roads in the rural areas. The farmers and unionists did not get along well. The 1923 election reflected a popular move to the right, with the Conservatives winning 50% of the vote and 75 seats of the 111 seats, making George Howard Ferguson premier.

When surveys of public health showed infant mortality rates were high in Ontario, particularly in the more rural and isolated areas, the provincial government teamed with middle-class public health reformers to take action. They launched an educational campaign to teach mothers to save and improve the lives of infants and young children, with the long-range goal of uplifting the average Canadian family.

Prohibition

Starting in the late 1870s the Ontario Woman's Christian Temperance Union (

Starting in the late 1870s the Ontario Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

) urged public schools to teach "scientific temperance" as a compulsory subject; it reinforced moralistic messages with the study of anatomy and hygiene. Although the WCTU was initially successful in convincing the Ontario Department of Education to adopt scientific temperance as part of the curriculum, teachers opposed the plan and refused to implement it. The WCTU reacted with an attempt to reduce alcohol sales and use in the province through government action. They started with "local option" laws, which allowed local governments to prohibit the sale of liquor. Many towns and rural areas went dry in the years before 1914, but not the larger cities.

Anti-German sentiment after 1914 and the accession of Conservative William Hearst to the premiership made prohibition a major political issue, as many residents associated beer production and drinking with Germans. The Methodists and Baptists (but not the Anglicans or Catholics) demanded the province be made dry. The government introduced prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcohol ...

of alcoholic sales in 1916 with the ''Ontario Temperance Act

The ''Ontario Temperance Act'' was a law passed in 1916 that led to the prohibition of alcohol in Ontario, Canada. When the Act was first enacted, the sale of alcohol was prohibited, but liquor could still be manufactured in the province or importe ...

''. However, drinking itself was never illegal, and residents could distill and retain their own personal supply. As major liquor producers could continue distillation and export for sale, Ontario became a centre for the illegal smuggling of liquor into the United States. The latter passed complete prohibition, effective after 1920. The "drys" won a referendum in 1919. Prohibition was ended in 1927 with the Conservative establishment of the Liquor Control Board of Ontario

The Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO) is a Crown corporations of Canada, Crown corporation that retails and distributes alcoholic beverages throughout the Provinces of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. It is accountable to the Legislati ...

.

However, the government still controls the sale and consumption of liquor, wine, and beer to ensure compliance with strict community standards and to generate revenue from the alcohol retail monopoly. In April 2007, Ontario Minister of Provincial Parliament Kim Craitor

Kim Craitor (born September 22, 1946) is a politician in Ontario, Canada. He is a former member of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, representing the constituency of Niagara Falls (provincial electoral district), Niagara Falls for the Ontari ...

suggested that local brewers should be able to sell their beer in local corner stores; however, the motion was quickly rejected by Premier Dalton McGuinty

Dalton James Patrick McGuinty Jr. (born July 19, 1955) is a former Canadian politician who served as the 24th premier of Ontario from 2003 to 2013. He was the first Liberal leader to win two majority governments since Mitchell Hepburn nea ...

.

Great Depression

Agriculture and industry alike suffered in the

Agriculture and industry alike suffered in the Great Depression in Canada

The worldwide Great Depression of the early 1930s was a social and economic shock that left millions of Canadians unemployed, hungry and often homeless. Few countries were affected as severely as Canada during what became known as the "Dirty Thirt ...

; hardest hit were the lumbering regions, the auto plants, and the steel mills. The milk industry suffered from price wars that hurt both dairy farmers and dairies. The government set up the Ontario Milk Control Board (MCB), which raised and stabilized prices through licensing, bonding, and fixed price agreements. The MCB resolved the crisis for the industry, but consumers complained loudly about higher prices. The government favoured producers over consumers as the industry rallied behind the MCB.

Following a massive defeat in 1934 by the Liberals, the Conservatives reorganized over the next decade. Led by pragmatic leaders Cecil Frost, George Drew, Alex McKenzie, and Fred Gardiner, they minimized internal conflicts, quietly dropped laissez-faire positions, and opted in favour of state intervention to deal with the Great Depression and encourage economic growth. The revised party declared loyalty to the Empire, called for comprehensive health care and pension programs, and sought more provincial autonomy. The reforms set the stage for a long run of election wins from 1943 onward.

Late 20th century

AfterWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, Ontario grew more in population. The Greater Toronto Area in particular has been the destination of most immigration to Canada, largely immigrants from Europe in the 1950s and 1960s. After changes in federal immigration law in 1967, most immigrants come from Asia. In terms of ancestry, Ontario has changed from a largely ethnically

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

British province, to one that is very diverse.

Toronto replaced Montreal as the nation's premier business centre because the nationalist movement in Quebec, particularly with the success of the

Toronto replaced Montreal as the nation's premier business centre because the nationalist movement in Quebec, particularly with the success of the Parti Québécois

The Parti Québécois (; ; PQ) is a sovereignist and social democratic provincial political party in Quebec, Canada. The PQ advocates national sovereignty for Quebec involving independence of the province of Quebec from Canada and establishin ...

in 1976, systematically drove Anglophone business away. Depressed economic conditions in the Maritime Provinces

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of Ca ...

have also resulted in de-population of those provinces in the 20th century, with heavy migration into Ontario.

Politics

The Ontario Progressive Conservative Party held power in the province from 1943 until 1985 by occupying the political centre and isolating both the Left and Right, at a time when Liberals most often controlled the national government in Ottawa. By contrast the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), which rebranded itself as the New Democratic Party (NDP) in 1961, was in the doldrums after the war. Its best showing was in 1948 when it elected 21 MPPs, and formed the official opposition. Purists said its decline resulted from a loss of Socialist purity and abandonment of the founding left-wing principles of the movement and party. They said democratic socialist activity in terms of activism, youth training, and volunteerism was lost in favour of authoritarian political bureaucracy. Moderates said the decline demonstrated the need for cooperation with Liberals. Political scientists said the party lacked the more coherent organizational base it needed to survive. The NDP routinely captured 20-some percent of the vote. In its surprise win in 1990, the NDP took 38% of the vote, won 75 of the 120 seats, and formed a government under Bob Rae. He served as premier but Ontario's labour unions, the backbone of the NDP, were outraged when Rae imposed pay cuts on unionized public workers. The NDP was defeated in 1995, falling back to 21% of the vote. Rae quit the NDP in 1998, describing it as too leftist, and joined the Liberals.Women's labour laws

Ontario's Fair Employment Practices Act combatted racist and religious discrimination after the Second World War, but it did not cover gender issues. Most human rights activists did not raise the issue before the 1970s, because they were family oriented and subscribed to the deeply embedded ideology of the family wage, whereby the husband should be paid enough so the wife could be a full-time housewife. After lobbying by women, labour unions, and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the Conservative government passed the Female Employees Fair Remuneration Act in 1951. It required equal pay for women who did the same work as men. Feminists in the 1950s and 1960s were unsuccessful trying to gain passage of a law to prohibit other forms of sex discrimination, such as in hiring and promotion. The enforcement of both acts was constrained by their conciliatory framework. Provincial officials interpreted the equal pay act quite narrowly, and were significantly more diligent in tackling racist and religious employment discrimination.Issues during the 20th century

Conservation and museums

Early efforts in the preservation of natural resources began with the passage of the Public Parks Act in 1883, which called for public parks in every town and city.Algonquin Provincial Park

Algonquin Provincial Park is a provincial park located between Georgian Bay and the Ottawa River in Ontario, Canada, mostly within the Unorganized South Part of Nipissing District. Established in 1893, it is the oldest provincial park in Can ...

, the first provincial park, was established in 1893. However, the creation of the provincial Department of Planning and Development did not take place until 1944; which brought conservation offices throughout the province and made for an integrated approach. The conservation authorities started to create heritage museums, but that ended in the 1970s when responsibility was shifted to the new ministry of Culture and Recreation. Repeated budget cuts in the 1980s and 1990s reduced the operation of many museums and historical sites.

Economy

Mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

exploitation accelerated in the late 19th century, leading to the rise of important mining centres in the northeast like Sudbury, Cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, p ...

, and Timmins

Timmins ( ) is a city in northeastern Ontario, Canada, located on the Mattagami River. The city is the fourth-largest city in the Northeastern Ontario region with a population of 41,145 (2021). The city's economy is based on natural resource ext ...

.

Energy policy focused on hydro-electric power