History Of Madrid on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The documented history of Madrid dates to the 9th century, even though the area has been inhabited since the

The site of modern-day Madrid has been controlled since prehistoric times, and archaeological research found a small

The site of modern-day Madrid has been controlled since prehistoric times, and archaeological research found a small  Since the mid-13th century and up to the late 14th century, the ''concejo'' of Madrid vied for the control of the Real de Manzanares territory against the ''concejo'' of

Since the mid-13th century and up to the late 14th century, the ''concejo'' of Madrid vied for the control of the Real de Manzanares territory against the ''concejo'' of  During the 15th century, the town became one of the preferred locations of the monarchs of the Trastámara dynasty, namely

During the 15th century, the town became one of the preferred locations of the monarchs of the Trastámara dynasty, namely

While all this was happening, the Mutiny of Aranjuez (17 March 1808) took place, led by Charles IV's own son, crown prince

While all this was happening, the Mutiny of Aranjuez (17 March 1808) took place, led by Charles IV's own son, crown prince

1858 was a marked year for the city with the arrival of the waters from the Lozoya. The Canal de Isabel II was inaugurated on 24 June 1858. A ceremony took place soon after in Calle Ancha de San Bernardo to celebrate it, unveiling a 30-metre-high water source in the middle of the street.

1858 was a marked year for the city with the arrival of the waters from the Lozoya. The Canal de Isabel II was inaugurated on 24 June 1858. A ceremony took place soon after in Calle Ancha de San Bernardo to celebrate it, unveiling a 30-metre-high water source in the middle of the street.

The plan for the Ensanche de Madrid ('widening of Madrid') by

The plan for the Ensanche de Madrid ('widening of Madrid') by  The economy of the city further modernized during the second half of the 19th century, consolidating its status as a service and financial centre. New industries were mostly focused in book publishing, construction and low-tech sectors. The introduction of railway transport greatly helped Madrid's economic prowess, and led to changes in consumption patterns (such as the substitution of salted fish for fresh fish from the Spanish coasts) as well as further strengthening the city's role as a logistics node in the country's distribution network.

The late 19th century saw the introduction of the

The economy of the city further modernized during the second half of the 19th century, consolidating its status as a service and financial centre. New industries were mostly focused in book publishing, construction and low-tech sectors. The introduction of railway transport greatly helped Madrid's economic prowess, and led to changes in consumption patterns (such as the substitution of salted fish for fresh fish from the Spanish coasts) as well as further strengthening the city's role as a logistics node in the country's distribution network.

The late 19th century saw the introduction of the  In the early 20th century Madrid undertook a major urban intervention in its city centre with the creation of the Gran Vía, a monumental thoroughfare (then divided in three segments with different names) whose construction slit the city from top to bottom with the demolition of multitude of housing and small streets. Anticipated in earlier projects, and following the signature of the contract, the works formally started in April 1910 with a ceremony led by King

In the early 20th century Madrid undertook a major urban intervention in its city centre with the creation of the Gran Vía, a monumental thoroughfare (then divided in three segments with different names) whose construction slit the city from top to bottom with the demolition of multitude of housing and small streets. Anticipated in earlier projects, and following the signature of the contract, the works formally started in April 1910 with a ceremony led by King  After the proclamation of the Second Republic on 14 April 1931 the citizens of Madrid understood the free access to the

After the proclamation of the Second Republic on 14 April 1931 the citizens of Madrid understood the free access to the  After the quelling of the coup d'état, from 1936–1939, Madrid remained under the control of forces loyal to the Republic. Following the seemingly unstoppable advance towards Madrid of rebel land troops, the first air bombings on Madrid also started. Immediately after the bombing of the nearing airports of

After the quelling of the coup d'état, from 1936–1939, Madrid remained under the control of forces loyal to the Republic. Following the seemingly unstoppable advance towards Madrid of rebel land troops, the first air bombings on Madrid also started. Immediately after the bombing of the nearing airports of  The summer and autumn of 1936 saw the Republican Madrid witness of heavy-handed repression by communist and socialist groups, symbolised by the murder of prisoners in ''checas'' and ''sacas'' directed mostly against military personnel and leading politicians linked to the rebels, which, culminated by the horrific Paracuellos massacres in the context of a simultaneous major rebel offensive against the city, were halted by early December.

Madrid, besieged from October 1936, saw a major offensive in its western suburbs in November of that year.

;Collapse

In the last weeks of the war, the collapse of the republic was speeded by Colonel

The summer and autumn of 1936 saw the Republican Madrid witness of heavy-handed repression by communist and socialist groups, symbolised by the murder of prisoners in ''checas'' and ''sacas'' directed mostly against military personnel and leading politicians linked to the rebels, which, culminated by the horrific Paracuellos massacres in the context of a simultaneous major rebel offensive against the city, were halted by early December.

Madrid, besieged from October 1936, saw a major offensive in its western suburbs in November of that year.

;Collapse

In the last weeks of the war, the collapse of the republic was speeded by Colonel  With the country ruined after the war, the

With the country ruined after the war, the  Together with the likes of

Together with the likes of

Benefiting from prosperity in the 1980s, Spain's capital city has consolidated its position as the leading economic, cultural, industrial, educational and technological center of the Iberian peninsula. The relative decline in population since 1975 reverted in the 1990s, with the city recovering a population of roughly 3 million inhabitants by the end of the 20th century.

Since the late 1970s and through the 1980s Madrid became the center of the cultural movement known as '' la Movida''. Conversely, just like in the rest of the country, a heroin crisis took a toll in the poor neighborhoods of Madrid in the 1980s.

During the mandate as mayor of

Benefiting from prosperity in the 1980s, Spain's capital city has consolidated its position as the leading economic, cultural, industrial, educational and technological center of the Iberian peninsula. The relative decline in population since 1975 reverted in the 1990s, with the city recovering a population of roughly 3 million inhabitants by the end of the 20th century.

Since the late 1970s and through the 1980s Madrid became the center of the cultural movement known as '' la Movida''. Conversely, just like in the rest of the country, a heroin crisis took a toll in the poor neighborhoods of Madrid in the 1980s.

During the mandate as mayor of  The administrations that followed Álvarez del Manzano's, also conservative, led by

The administrations that followed Álvarez del Manzano's, also conservative, led by

Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with t ...

. The primitive nucleus of Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, a walled military outpost in the left bank of the Manzanares, dates back to the second half of the 9th century, during the rule of the Emirate of Córdoba

The Emirate of Córdoba ( ar, إمارة قرطبة, ) was a medieval Islamic kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula. Its founding in the mid-eighth century would mark the beginning of seven hundred years of Muslim rule in what is now Spain and Port ...

. Conquered by Christians in 1083 or 1085, Madrid consolidated in the Late Middle Ages as a middle to upper-middle rank town of the Crown of Castile. The development of Madrid as administrative centre began when the court of the Hispanic Monarchy was settled in the town in 1561.

Fortress and town

The site of modern-day Madrid has been controlled since prehistoric times, and archaeological research found a small

The site of modern-day Madrid has been controlled since prehistoric times, and archaeological research found a small Visigoth

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kno ...

ic village nearby.

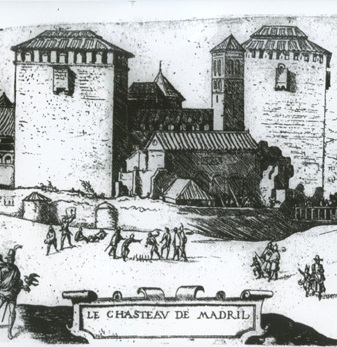

The primitive urban nucleus of Madrid (''Mayrit'') was founded in the late 9th century (from 852 to 886) as a citadel erected on behalf of Muhammad I, the Cordobese emir, on the relatively steep left bank of the Manzanares. Originally it was largely a military outpost for the quartering of troops. Similarly to other fortresses north of the Tagus, Madrid made it difficult to muster reinforcements from the Asturian kingdom to the unruly inhabitants of Toledo, prone to rebellion against the Umayyad rule. Extending across roughly 8 ha, Muslim Madrid consisted of the ''alcázar

An alcázar, from Arabic ''al-Qasr'', is a type of Islamic castle or palace in the Iberian Peninsula (also known as al-Andalus) built during Muslim rule between the 8th and 15th centuries. They functioned as homes and regional capitals for gover ...

'' and the wider walled citadel (''al-Mudayna'') with the addition of some housing outside the walls. By the late 10th century, ''Mayrit'' was an important borderland military stronghold with great strategic value, owing to its proximity to Toledo. The most generous estimates for the 10th century tentatively and intuitively put the number of inhabitants of the 9 ha settlement at 2,000. The model of repopulation is likely to have been by the ''Limitanei

The ''līmitāneī'' (Latin, also called ''rīpēnsēs''), meaning respectively "the soldiers in frontier districts" (from the Latin phrase līmēs, meaning a military district of a frontier province) or "the soldiers on the riverbank" (from the ...

'', characteristic of the borderlands.

The settlement is mentioned in the work of the 10th-century Cordobese chronicler Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Razi, with the latter locating the Castle of Madrid within the district of Guadalajara. After the Christian conquest, in the first half of the 12th century Al-Idrisi described Madrid as a "small city and solid fortress, well populated. In the age of Islam, it had a small mosque where the khuṭbah was always delivered," and placed it in the province of the sierra, "al-Sārrāt". It was ascribed by most post-Christian conquest Muslim commentators, including Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi

Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Mūsā ibn Saʿīd al-Maghribī ( ar, علي بن موسى المغربي بن سعيد) (1213–1286), also known as Ibn Saʿīd al-Andalusī, was an Arab geographer, historian, poet, and the most important collector o ...

, to Toledo. This may tentatively suggest that the settlement, part of the cora of Guadalajara according to al-Razi, could have been transferred to Toledo following the Fitna of al-Andalus

The Fitna of al-Andalus ( ar, فتنة الأندلس; 1009–1031) was a period of instability and civil war that preceded the ultimate collapse of the Caliphate of Córdoba. It began in the year 1009 with a coup d'état which led to the assas ...

.

The Moors controlled the citadel until Alfonso VI of León and Castile

Alphons (Latinized ''Alphonsus'', ''Adelphonsus'', or ''Adefonsus'') is a male given name recorded from the 8th century ( Alfonso I of Asturias, r. 739–757) in the Christian successor states of the Visigothic kingdom in the Iberian peninsula ...

conquered them in 1085 in his advance towards Toledo. The mosque was reconsecrated as the church of the Virgin of Almudena (, the garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mil ...

's granary

A granary is a storehouse or room in a barn for threshed grain or animal feed. Ancient or primitive granaries are most often made of pottery. Granaries are often built above the ground to keep the stored food away from mice and other animal ...

). The town had a Muslim and mozarabic

Mozarabic, also called Andalusi Romance, refers to the medieval Romance varieties spoken in the Iberian Peninsula in territories controlled by the Islamic Emirate of Córdoba and its successors. They were the common tongue for the majority of ...

preexisting population (a number of the former would remain in the town after the conquest while the later community would remain very large throughout the high middle ages before merging with the new settlers). The town was further repopulated by settlers with a dominant Castilian-Leonese extraction. Frank settlers were a minority but influential community. The Jewish community was probably smaller in number than the ''mudéjar

Mudéjar ( , also , , ca, mudèjar , ; from ar, مدجن, mudajjan, subjugated; tamed; domesticated) refers to the group of Muslims who remained in Iberia in the late medieval period despite the Christian reconquest. It is also a term for ...

'' one, standing out as physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner ( Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through t ...

s up until their expulsion.

Segovia

Segovia ( , , ) is a city in the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the Province of Segovia.

Segovia is in the Inner Plateau ('' Meseta central''), near the northern slopes of ...

, a powerful town north of the Sierra de Guadarrama

The Sierra de Guadarrama (Guadarrama Mountains) is a mountain range forming the main eastern section of the Sistema Central, the system of mountain ranges along the centre of the Iberian Peninsula. It is located between the systems Sierra de G ...

mountain range, characterised by its repopulating prowess and its husbandry-based economy, contrasted by the agricultural and less competent in repopulation town of Madrid. After the decline of Sepúlveda, another ''concejo'' north of the mountain range, Segovia had become a major actor south of the Guadarrama mountains, expanding across the Lozoya and Manzanares rivers to the north of Madrid and along the Guadarrama river course to its west.

The society of Madrid before the 15th century was an agriculture-based one (prevailing over livestock), featuring a noteworthy number of irrigated crops. Two important industries were those of the manufacturing of building material

Building material is material used for construction. Many naturally occurring substances, such as clay, rocks, sand, wood, and even twigs and leaves, have been used to construct buildings. Apart from naturally occurring materials, many man-ma ...

s and leather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffalo, pigs and hogs ...

.

John I of Castile gifted Leo V of Armenia

Leo V or Levon V (occasionally Levon VI; hy, Լևոն, ''Levon V''; 1342 – 29 November 1393), of the House of Lusignan, was the last Latin king of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. He ruled from 1374 to 1375.

Leo was described as "Leo V, King o ...

the lordship of Madrid together with those of Villa Real and Andújar

Andújar () is a Spanish municipality of 38,539 people (2005) in the province of Jaén, in Andalusia. The municipality is divided by the Guadalquivir River. The northern part of the municipality is where the Natural Park of the Sierra de And� ...

in 1383. The Madrilenian ''concejo'' made sure that the privilege of lordship did not become hereditary, also presumably receiving a non-sale privilege guaranteeing never again to be handed over by the Crown to a lord.

Later, Henry III of Castile

Henry III of Castile (4 October 1379 – 25 December 1406), called the Suffering due to his ill health (, ), was the son of John I and Eleanor of Aragon. He succeeded his father as King of Castile in 1390.

Birth and education

Henry was born ...

(1379–1406) rebuilt the town after it was destroyed by fire, and he founded El Pardo

El Pardo is a ward ('' barrio'') of Madrid belonging to the district of Fuencarral-El Pardo. As of 2008 its population was of 3,656.

History

The ward was first mentioned in 1405 and in 1950 was an autonomous municipality of the Community of Mad ...

just outside its walls.

During the 15th century, the town became one of the preferred locations of the monarchs of the Trastámara dynasty, namely

During the 15th century, the town became one of the preferred locations of the monarchs of the Trastámara dynasty, namely John II of Castile

John II of Castile ( es, link=no, Juan; 6 March 1405 – 20 July 1454) was King of Castile and León from 1406 to 1454. He succeeded his older sister, Maria of Castile, Queen of Aragon, as Prince of Asturias in 1405.

Regency

John was th ...

and Henry IV of Castile

Henry IV of Castile ( Castilian: ''Enrique IV''; 5 January 1425 – 11 December 1474), King of Castile and León, nicknamed the Impotent, was the last of the weak late-medieval kings of Castile and León. During Henry's reign, the nobles became ...

(Madrid was the town in which the latter spent more time and eventually died). Among the appeals the town offered, aside from the abundant game in the surroundings, the strategic location and the closed link between the existing religious sites and the monarchy, the imposing alcázar

An alcázar, from Arabic ''al-Qasr'', is a type of Islamic castle or palace in the Iberian Peninsula (also known as al-Andalus) built during Muslim rule between the 8th and 15th centuries. They functioned as homes and regional capitals for gover ...

frequently provided a safe for the Royal Treasure. The town briefly hosted a medieval mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative to TOS and MagiC. Together with the free system components fVDI device drivers, XaAES ...

, manufacturing coins from 1467 to 1471. Madrid would also become a frequent seat of the court during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being b ...

, spending reportedly more than 1000 days in the town, including a 8-month long uninterrupted spell.

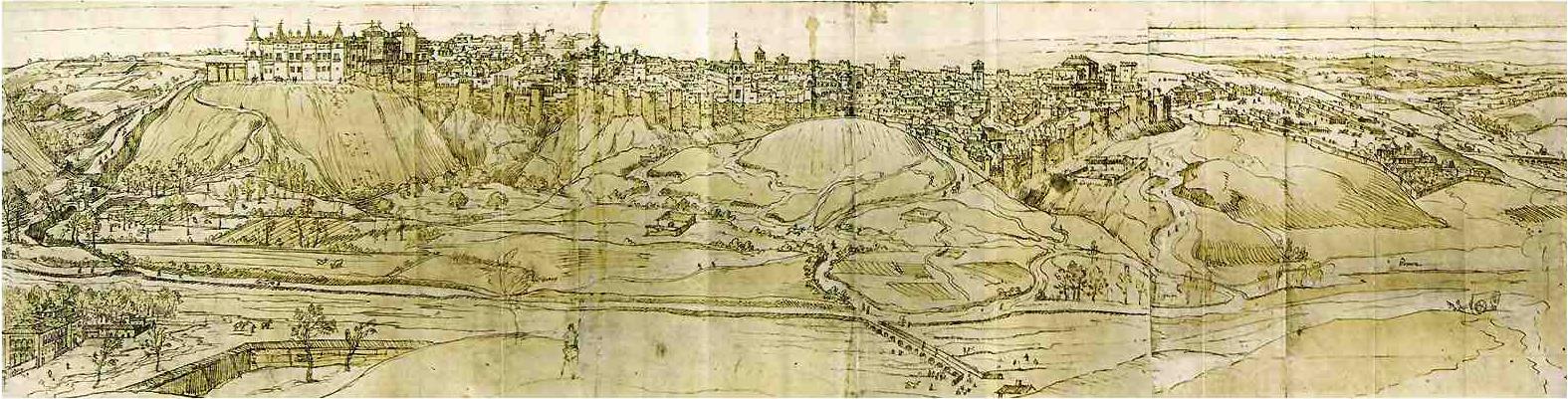

By the end of the Middle Ages, Madrid was placed as middle to upper-middle rank town of the Castilian urban network in terms of population. The town also enjoyed a vote at the Cortes of Castile (one out of 18) and housed many hermitages and hospitals.

The 1520–21 Revolt of the Comuneros succeeded in Madrid, as, following contacts with the neighbouring city of Toledo, the ''comunero'' rebels deposed the '' corregidor'', named Antonio de Astudillo, by 17 June 1520. Juan Zapata and Pedro de Montemayor found themselves among the most uncompromising supporters of the comunero cause in Madrid, with the former becoming the captain of the local militias while the later was captured by royalists and executed by late 1520. The end of revolt came through a negotiation, though, and another two of the leading figures of the uprising (the Bachelor Castillo and Juan Negrete) went unpunished.

Capital of the empire

Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

(1527–1598), moved the court to Madrid in 1561. Although he made no official declaration, the seat of the court became the ''de facto'' capital. Unlikely to have more than 20,000 inhabitants by the time, the city grew approaching the 100,000 mark by the end of the 16th century. The population plummeted (reportedly reduced to a half) during the 5-year period the capital was set in Valladolid

Valladolid () is a municipality in Spain and the primary seat of government and de facto capital of the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. It has a population around 300,000 peop ...

(1601–1606), with estimations of roughly 50–60,000 people leaving the city. The move (often framed in modern usage as a case of real estate speculation

In finance, speculation is the purchase of an asset (a commodity, goods, or real estate) with the hope that it will become more valuable shortly. (It can also refer to short sales in which the speculator hopes for a decline in value.)

Many ...

) was promoted by the '' valido'' of Philip III, Duke of Lerma

Francisco Gómez de Sandoval y Rojas, 1st Duke of Lerma, 5th Marquess of Denia, 1st Count of Ampudia (1552/1553 – 17 May 1625), was a favourite of Philip III of Spain, the first of the ''validos'' ('most worthy') through whom the later H ...

, who had previously acquired many properties in Valladolid. Madrid undertook a mammoth cultural and economic crisis and the decimation of the price of housing ensued. Lerma acquired then cheap real estate in Madrid, and suggested the King to move back the capital to Madrid. The king finally accepted the additional ducat

The ducat () coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages from the 13th to 19th centuries. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wi ...

s offered by the town of Madrid in order to help financing the move of the royal court back to Madrid.

During the 17th century, Madrid had a estate-based society. The nobility, a quantitatively large group, swarmed around the royal court. The ecclesial hierarchy, featuring a nobiliary extraction, shared with the nobility the echelon of the Madrilenian society. The lower clergy, featuring a humble extraction, usually had a rural background, although clerics regular

Clerics regular are clerics (mostly priests) who are members of a religious order under a rule of life (regular). Clerics regular differ from canons regular in that they devote themselves more to pastoral care, in place of an obligation to the pray ...

often required certifications of ''limpieza de sangre

The concept of (), (, ) or (), literally "cleanliness of blood" and meaning "blood purity", was an early system of racialized discrimination used in early modern Spain and Portugal.

The label referred to those who were considered "Old Chri ...

'' if not '' hidalguía''. There were plenty of civil servants, who enjoyed considerable social prestige. There was a comparatively small number of craftsmen, traders and goldsmiths. Domestic staff was also common with servants such as pages, squires, butlers and also slaves (owned as symbol of social status). And lastly at the lowest end, there were homeless people, unemployed immigrants, and discharged soldiers and deserters.

During the 17th century, Madrid grew rapidly. The royal court attracted many of Spain's leading artists and writers to Madrid, including Cervantes, Lope de Vega, and Velázquez during the so-called cultural Siglo de Oro

The Spanish Golden Age ( es, Siglo de Oro, links=no , "Golden Century") is a period of flourishing in arts and literature in Spain, coinciding with the political rise of the Spanish Empire under the Catholic Monarchs of Spain and the Spanish H ...

.

By the end of the Ancient Regime, Madrid hosted a slave population, tentatively estimated to range from 6,000 to 15,000 out of total population larger than 150,000. Unlike the case of other Spanish cities, during the 18th century the slave population in Madrid was unbalanced in favour of males over females.

In 1739 Philip V began constructing new palaces, including the Palacio Real de Madrid. Under Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to a ...

(1716–1788) that Madrid became a truly modern city. Charles III, who cleaned up the city and its government, became one of the most popular kings to rule Madrid, and the saying "the best mayor, the king" became widespread. Besides completing the Palacio Real, Charles III is responsible for many of Madrid's finest buildings and monuments, including the Prado

The Prado Museum ( ; ), officially known as Museo Nacional del Prado, is the main Spanish national art museum, located in central Madrid. It is widely considered to house one of the world's finest collections of European art, dating from the ...

and the Puerta de Alcalá

The Puerta de Alcalá is a Neo-classical gate in the Plaza de la Independencia in Madrid, Spain.

It was a gate of the former Walls of Philip IV. It stands near the city center and several meters away from the main entrance to the Parque del B ...

.

Amid one of the worst subsistence crises

A subsistence crisis is a crisis caused by economic factors, and example being high costs for food, which may be caused by either natural or man-made factors."The European subsistence crisis of 1845–1850: a comparative perspective", http://www. ...

of the Bourbon monarchy, the installation of news lanterns for the developing street lighting

A street light, light pole, lamp pole, lamppost, street lamp, light standard, or lamp standard is a raised source of light on the edge of a road or path. Similar lights may be found on a railway platform. When urban electric power distribution ...

system—part of the new modernization policies of the Marquis of Esquilache, the new Sicilian minister—led to an increase on oil prices. This added to an increasing tax burden imposed on a populace already at the brink of famine. In this context, following the enforcing of a ban of the traditional Spanish dress (long cape and a wide-brimmed hat) in order to facilitate the identification of criminal suspects, massive riots erupted in March 1766 in Madrid, the so-called "Mutiny of Esquilache".

During the second half of the 18th century, the increasing number of carriages brought a collateral increment of pedestrian accidents, forcing the authorities to take measures against traffic, limiting the number of animals per carriage (in order to reduce speed) and eventually decreeing the full ban of carriages in the city (1787).

On 27 October 1807, Charles IV and Napoleon signed the Treaty of Fontainebleau, which allowed French troops passage through Spanish territory to join Spanish troops and invade Portugal, which had refused to obey the order for an international blockade against England. In February 1808, Napoleon used the excuse that the blockade against England was not being respected at Portuguese ports to send a powerful army under his brother-in-law, General Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also , ; it, Gioacchino Murati; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French military commander and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the ...

. Contrary to the treaty, French troops entered via Catalonia, occupying the plazas along the way. Thus, throughout February and March 1808, cities like Barcelona and Pamplona remained under French rule.

While all this was happening, the Mutiny of Aranjuez (17 March 1808) took place, led by Charles IV's own son, crown prince

While all this was happening, the Mutiny of Aranjuez (17 March 1808) took place, led by Charles IV's own son, crown prince Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

, and directed against him. Charles IV resigned and Ferdinand took his place as King Ferdinand VII. In May 1808, Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's troops entered the city. On 2 May 1808 (Spanish: Dos de Mayo), the Madrileños revolted against the French forces, whose brutal behavior would have a lasting impact on French rule in Spain and France's image in Europe in general. Thus, Ferdinand VII returned to a city that had been occupied by Murat.

Both the king and his father became virtual prisoners of the French army. Napoleon, taking advantage of the weakness of the Bourbons, forced both, first the father and then the son, to meet him at Bayonne

Bayonne (; eu, Baiona ; oc, label= Gascon, Baiona ; es, Bayona) is a city in Southwestern France near the Spanish border. It is a commune and one of two subprefectures in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department, in the Nouvelle-Aquitain ...

, where Ferdinand VII arrived on 20 April. Here Napoleon forced both kings to abdicate on 5 May, handing the throne to his brother Joseph Bonaparte

it, Giuseppe-Napoleone Buonaparte es, José Napoleón Bonaparte

, house = Bonaparte

, father = Carlo Buonaparte

, mother = Letizia Ramolino

, birth_date = 7 January 1768

, birth_place = Corte, Corsica, Republic of ...

.

On 2 May, the crowd began to concentrate at the Palacio Real

The Royal Palace of Madrid ( es, Palacio Real de Madrid) is the official residence of the Spanish royal family at the city of Madrid, although now used only for state ceremonies.

The palace has of floor space and contains 3,418 rooms. It is the ...

and watched as the French soldiers removed the royal family members from the palace. On seeing the ''infante'' Francisco de Paula struggling with his captor, the crowd launched an assault on the carriages, shouting ''¡Que se lo llevan!'' (They're taking him away from us!). French soldiers fired into the crowd. The fighting lasted for hours and is reflected in Goya

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (; ; 30 March 174616 April 1828) was a Spanish romantic painter and printmaker. He is considered the most important Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. His paintings, drawings, and e ...

's painting, ''The Second of May 1808

''The Second of May 1808, by Goya'', also known as ''The Charge of the Mamelukes'' ( es, El 2 de mayo de 1808 en Madrid, or ), is a painting by the Spanish painter Francisco Goya. It is a companion to the painting '' The Third of May 1808' ...

'', also known as ''The Charge of the Mamelukes

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

''.

Meanwhile, the Spanish military remained garrisoned and passive. Only the artillery barracks at Monteleón under Captain Luis Daoíz y Torres, manned by four officers, three NCOs and ten men, resisted. They were later reinforced by a further 33 men and two officers led by Pedro Velarde y Santillán, and distributed weapons to the civilian population. After repelling a first attack under French General Lefranc, both Spanish commanders died fighting heroically against reinforcements sent by Murat. Gradually, the pockets of resistance fell. Hundreds of Spanish men and women and French soldiers were killed in this skirmish.

On 12 August 1812, following the defeat of the French forces at Salamanca, English and Portuguese troops entered Madrid and surrounded the fortified area occupied by the French in the district of Retiro. Following two days of Siege warfare, the 1,700 French surrendered and a large store of arms, 20,000 muskets and 180 cannon, together with many other supplies were captured, along with two French Imperial Eagle

The French Imperial Eagle (''Aigle de drapeau'', lit. "flag eagle") refers to the figure of an eagle on a staff carried into battle as a standard by the ''Grande Armée'' of Napoleon during the Napoleonic Wars.

Although they were presented with ...

s.

On 29 October, Hill

A hill is a landform that extends above the surrounding terrain. It often has a distinct summit.

Terminology

The distinction between a hill and a mountain is unclear and largely subjective, but a hill is universally considered to be not as ...

received Wellington's positive order to abandon Madrid and march to join him. After a clash with Soult's advance guard at Perales de Tajuña on the 30th, Hill broke contact and withdrew in the direction of Alba de Tormes

Alba de Tormes is a municipality in the province of Salamanca, western Spain, part of the autonomous community of Castile and León. The town is on the River Tormes upstream from the city of Salamanca. Alba gave its name to one of Spain's most ...

. Joseph re-entered his capital on 2 November.

After the war of independence Ferdinand VII

Ferdinand VII ( es, Fernando VII; 14 October 1784 – 29 September 1833) was a King of Spain during the early 19th century. He reigned briefly in 1808 and then again from 1813 to his death in 1833. He was known to his supporters as '' el Deseado' ...

returned to the throne (1814). The projects of reform by Joseph Bonaparte were abandoned; during the Fernandine period, despite the proposal of several architectural projects for the city, the lack of ability to finance those led to works often being postponed or halted.

After a liberal military revolution, Colonel Riego made the king swear to respect the Constitution. Liberal and conservative government thereafter alternated, ending with the enthronement of Isabella II.

Capital of the state

At the time the reign of Isabella II started, the city was still enclosed behind its walls, featuring a relatively slow demographic growth as well as very high population density. After the 1833 administrative reforms for the country devised byJavier de Burgos

Francisco Javier de Burgos y del Olmo (22 October 1778—22 January 1848) was a Spanish jurist, politician, journalist, and translator.

Early life and career

Born in Motril, into a noble but poor family, he was destined for a career in the ...

(including the configuration of the current province of Madrid), Madrid was to become the capital of the new liberal state.

Madrid experienced substantial changes during the 1830s. The ''corregimiento

''Corregimiento'' (; ca, Corregiment, ) is a Spanish term used for country subdivisions for royal administrative purposes, ensuring districts were under crown control as opposed to local elites. A ''corregimiento'' was usually headed by a ''corre ...

'' and the ''corregidor'' (institutions from the Ancien Regime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for ...

) were ended for good, giving rise to the constitutional ''alcalde

Alcalde (; ) is the traditional Spanish municipal magistrate, who had both judicial and administrative functions. An ''alcalde'' was, in the absence of a corregidor, the presiding officer of the Castilian '' cabildo'' (the municipal council) a ...

'' in the context of the liberal transformations. Purged off from Carlist

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty – one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855) – o ...

elements, the civil office and the military and palatial milieus recognised legitimacy to the dynastic rights of Isabella II.

The reforms enacted by Finance Minister Juan Álvarez Mendizábal

Juan Álvarez Mendizábal (born ''Juan Álvarez Méndez''; 25 February 1790 – 3 November 1853), was a Spanish economist and politician who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 25 September 1835 to 15 May 1836.

Biography

He was born to Rafae ...

in 1835–1836 led to the confiscation of ecclesiastical properties and the subsequent demolition of churches, convents and adjacent orchards in the city (similarly to other Spanish cities); the widening of streets and squares ensued.

In 1854, amid economic and political crisis, following the ''pronunciamiento'' of group of high officers commanded by Leopoldo O'Donnell

Leopoldo O'Donnell y Jorris, 1st Duke of Tetuán, GE (12 January 1809 – 5 November 1867), was a Spanish general and Grandee who was Prime Minister of Spain on several occasions.

Early life

He was born at Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canar ...

garrisoned in the nearby town of Vicálvaro

Vicálvaro is a district in the southeast of Madrid, Spain. It is named after the former municipality absorbed into the municipality of Madrid in 1951.

History

When Spain's Civil Guard ( es, Guardia Civil) was established in 1844, the first head ...

in June 1854 (the so-called "Vicalvarada"), the 7 July ''Manifesto of Manzanares'', calling for popular rebellion, and the ousting of Luis José Sartorius from the premiership on 17 July, popular mutiny broke out in Madrid, asking for a real change of system, in what it was to be known as the Revolution of 1854. With the uprising in Madrid reaching its pinnacle on 17, 18 and 19 July, the rebels, who erected barricades in the streets, were bluntly crushed by the new government.

1858 was a marked year for the city with the arrival of the waters from the Lozoya. The Canal de Isabel II was inaugurated on 24 June 1858. A ceremony took place soon after in Calle Ancha de San Bernardo to celebrate it, unveiling a 30-metre-high water source in the middle of the street.

1858 was a marked year for the city with the arrival of the waters from the Lozoya. The Canal de Isabel II was inaugurated on 24 June 1858. A ceremony took place soon after in Calle Ancha de San Bernardo to celebrate it, unveiling a 30-metre-high water source in the middle of the street.

The plan for the Ensanche de Madrid ('widening of Madrid') by

The plan for the Ensanche de Madrid ('widening of Madrid') by Carlos María de Castro

Carlos María de Castro (24 September 1810 - 2 November 1893) was a Spanish architect, engineer and urban planner. He created the plan of the urban expansion (''Ensanche'') of Madrid.

The New Plan of Madrid was commissioned in 1857 and adopted in ...

was passed through a royal decree issued on 19 July 1860. The plan for urban expansion by Castro, a staunch Conservative, delivered a segregation of the well-off class, the middle class and the artisanate into different zones. The southern part of the Ensanche was at a disadvantage with respect to the rest of the Ensanche, insofar, located on the way to the river and at a lower altitude, it was a place of passage for the sewage runoff, thereby being described as a "space of urban degradation and misery". Beyond the Ensanches, slums and underclass neighborhoods were built in suburbs such as Tetuán, Prosperidad or Vallecas.

Student unrest took place in 1865 following the ministerial decree against the expression of ideas against the monarchy and the church and the forced removal of the rector of the Universidad Central, unwilling to submit. In a ''crescendo'' of protests, the night of 10 April 2,000 protesters clashed against the civil guard. The unrest was crudely quashed, leaving 14 deaths, 74 wounded students and 114 arrests (in what became known as the "Night of Saint Daniel"), becoming the precursor of more serious revolutionary attempts.

The Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

resulting in the deposition of Queen Isabella II started with a ''pronunciamiento

A ''pronunciamiento'' (, pt, pronunciamento ; "proclamation , announcement or declaration") is a form of military rebellion or ''coup d'état'' particularly associated with Spain, Portugal and Latin America, especially in the 19th century.

Typol ...

'' in the bay of Cádiz

The Bay of Cádiz is a body of water in the province of Cádiz, Spain, adjacent to the southwestern coast of the Iberian Peninsula.

The Bay of Cádiz adjoins the Gulf of Cádiz, a larger body of water which is in the same area but further offsho ...

in September 1868. The success of the uprising in Madrid on 29 September prompted the French exile of the queen, who was on holiday in San Sebastián

San Sebastian, officially known as Donostia–San Sebastián (names in both local languages: ''Donostia'' () and ''San Sebastián'' ()) is a city and municipality located in the Basque Autonomous Community, Spain. It lies on the coast of the ...

and was unable to reach the capital by train. General Juan Prim

Juan Prim y Prats, 1st Count of Reus, 1st Marquis of los Castillejos, 1st Viscount of Bruch (; ca, Joan Prim i Prats ; 6 December 1814 – 30 December 1870) was a Spanish general and statesman who was briefly Prime Minister of Spain until h ...

, the leader of the liberal progressives, was received by the Madrilenian people at his arrival to the city in early October in a festive mood. He pronounced his famous speech of the "three nevers" directed against the Bourbons, and delivered a highly symbolical hug to General Serrano, leader of the revolutionary forces triumphant in the 28 September battle of Alcolea, in the Puerta del Sol.

On 27 December 1870 the car in which General Prim, the prime minister, was travelling, was shot by unknown hit-men in the Turk Street, nearby the Congress of Deputies. Prim, wounded in the attack, died three days later, with the elected monarch Amadeus, Duke of Aosta, yet to swear the constitution.

The creation of the Salamanca–Sol–Pozas tram service in Madrid in 1871 meant the introduction of the first collective system of transportation in the city, predating the omnibus.

The economy of the city further modernized during the second half of the 19th century, consolidating its status as a service and financial centre. New industries were mostly focused in book publishing, construction and low-tech sectors. The introduction of railway transport greatly helped Madrid's economic prowess, and led to changes in consumption patterns (such as the substitution of salted fish for fresh fish from the Spanish coasts) as well as further strengthening the city's role as a logistics node in the country's distribution network.

The late 19th century saw the introduction of the

The economy of the city further modernized during the second half of the 19th century, consolidating its status as a service and financial centre. New industries were mostly focused in book publishing, construction and low-tech sectors. The introduction of railway transport greatly helped Madrid's economic prowess, and led to changes in consumption patterns (such as the substitution of salted fish for fresh fish from the Spanish coasts) as well as further strengthening the city's role as a logistics node in the country's distribution network.

The late 19th century saw the introduction of the electric power distribution

Electric power distribution is the final stage in the delivery of electric power; it carries electricity from the transmission system to individual consumers. Distribution substations connect to the transmission system and lower the transmissi ...

. As by law, the city council could not concede an industrial monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

to any company, the city experienced a huge competition among the companies in the electricity sector. The absence of a monopoly led to an overlapping of distribution networks, to the point that in the centre of Madrid 5 different networks could travel through the same street. Electric lighting in the streets was introduced in the 1890s.

By the end of the 19th century, the city featured access to water, a central status in the rail network, a cheap workforce and access to financial capital. With the onset of the new century, the Ensanche Sur (in the current day district of Arganzuela) started to grow to become the main industrial area of the municipality along the first half of the 20th century.

In the early 20th century Madrid undertook a major urban intervention in its city centre with the creation of the Gran Vía, a monumental thoroughfare (then divided in three segments with different names) whose construction slit the city from top to bottom with the demolition of multitude of housing and small streets. Anticipated in earlier projects, and following the signature of the contract, the works formally started in April 1910 with a ceremony led by King

In the early 20th century Madrid undertook a major urban intervention in its city centre with the creation of the Gran Vía, a monumental thoroughfare (then divided in three segments with different names) whose construction slit the city from top to bottom with the demolition of multitude of housing and small streets. Anticipated in earlier projects, and following the signature of the contract, the works formally started in April 1910 with a ceremony led by King Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII (17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941), also known as El Africano or the African, was King of Spain from 17 May 1886 to 14 April 1931, when the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed. He was a monarch from birth as his father, Alfo ...

.

Also with the turn of the century, Madrid had become the cultural capital of Spain as centre of top knowledge institutions (the Central University, the Royal Academies, the Institución Libre de Enseñanza

La Institución Libre de Enseñanza (ILE, English: ''The Free Institution of Education''), was an educational project developed in Spain for over half a century (1876–1936). The institute was inspired by the philosophy of Krausism, first introd ...

or the Ateneo de Madrid

The Ateneo de Madrid ("Athenæum of Madrid") is a private cultural institution located in the capital of Spain that was founded in 1835. Its full name is ''Ateneo Científico, Literario y Artístico de Madrid'' ("Scientific, Literary and Artistic ...

), also concentrating the most publishing houses and big daily newspapers, amounting for the bulk of the intellectual production in the country.

In 1919 the Madrid Metro

The Madrid Metro ( Spanish: ''Metro de Madrid'') is a rapid transit system serving the city of Madrid, capital of Spain. The system is the 14th longest rapid transit system in the world, with a total length of 293 km (182 mi). Its gr ...

(known as the ''Ferrocarril Metropolitano'' by that time) inaugurated its first service, which went from Sol to the Cuatro Caminos area.

In the 1919–1920 biennium Madrid witnessed the biggest wave of protests seen in the city up to that date, being the centre of innumerable strikes; despite being still surpassed by Barcelona's, the industrial city ''par excellence'' in that time, this cycle decisively set the foundations for the social unrest that took place in the 1930s in the city.

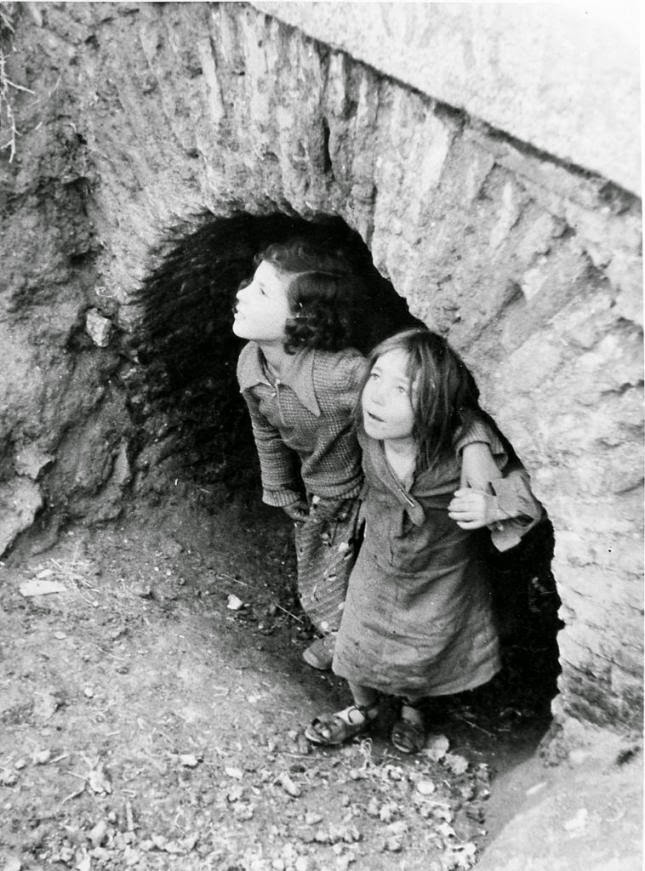

The situation the monarchy had left Madrid in 1931 was catastrophic, with tens of thousands of kids receiving no education and a huge rate of unemployment.

After the proclamation of the Second Republic on 14 April 1931 the citizens of Madrid understood the free access to the

After the proclamation of the Second Republic on 14 April 1931 the citizens of Madrid understood the free access to the Casa de Campo

The Casa de Campo (, for Spanish: ''Country House'') is the largest public park in Madrid. It is situated west of central Madrid, Spain. It gets its name 'Country House' because it was once a royal hunting estate, located just west of the Ro ...

(until then an enclosed property with exclusive access for the royalty), was a consequence of the fall of the monarchy, and informally occupied the area on 15 April. After the signing of a decree on 20 April which granted the area to the Madrilenian citizens in order to become a "park for recreation and instruction", the transfer was formally sealed on 6 May when Minister Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero (30 April 1883 – 11 February 1962) was a Spanish politician, a minister and one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic.

Early life ...

formally delivered the Casa de Campo to Mayor Pedro Rico. The Spanish Constitution of 1931

The Spanish Constitution of 1931 was approved by the Constituent Assembly on 9 December 1931. It was the constitution of the Second Spanish Republic (founded 14 April 1931) and was in force until 1 April 1939. This was the second period of Spani ...

was the first legislating on the state capital, setting it explicitly in Madrid.

During the 1930s, Madrid enjoyed "great vitality"; it was demographically young, but also young in the sense of its relation with the modernity. During this time the prolongation of the Paseo de la Castellana

Paseo de la Castellana, commonly known as La Castellana, is a major thoroughfare in Madrid, Spain. Cutting across the city from South to North, it has been described as the "true structuring axis" of the city.

History and description

The street ...

towards the north was projected. The proclamation of the Republic slowed down the building of new housing. The tertiary sector gave thrust to the economy. Illiteracy rates were down to below 20%, and the city's cultural life grew notably during the so-called ''Silver Age'' of Spanish culture; the sales of newspaper also increased. Anti-clericalism and Catholicism lived side by side in Madrid; the burning of convents initiated after riots in the city in May 1931 worsened the political environment. The 1934 insurrection largely failed in Madrid.

In order to deal with the unemployment, the new Republican city council hired many jobless people as gardeners and street cleaners.

Prieto, who sought to turn the city into the "Great Madrid", capital of the Republic, charged Secundino Zuazo with the project for the opening of a south–north axis in the city through the northward enlargement of the Paseo de la Castellana

Paseo de la Castellana, commonly known as La Castellana, is a major thoroughfare in Madrid, Spain. Cutting across the city from South to North, it has been described as the "true structuring axis" of the city.

History and description

The street ...

and the construction of the Nuevos Ministerios

Nuevos Ministerios () is a government complex in central Madrid, Spain. The complex houses several government departments: Development, Labour, Social Security, and Ecological Transition. It is located in the block delimited by the Paseo de l ...

administrative complex in the area (halted by the Civil War, works in the Nuevos Ministerios would finish in 1942). Works on the Ciudad Universitaria, already started during the monarchy in 1929, also resumed.

;Botched coup

The military uprising of July 1936 was defeated in Madrid by a combination of loyal forces and workers' militias. On 20 July armed workers and loyal troops stormed the single focus of resistance, the Cuartel de La Montaña, defended by a contingent of 2,000 rebel soldiers accompanied by 500 falangists under the command of General Fanjul, killing over one hundred of rebels after their surrender. Aside from the Cuartel de la Montaña episode, the wider scheme for the coup in the capital largely failed both due to disastrous rebel planning and due to the Government delivering weapons to the people wanting to defend the Republic, with the city becoming a symbol of popular resistance, "the people in arms".

;Siege

After the quelling of the coup d'état, from 1936–1939, Madrid remained under the control of forces loyal to the Republic. Following the seemingly unstoppable advance towards Madrid of rebel land troops, the first air bombings on Madrid also started. Immediately after the bombing of the nearing airports of

After the quelling of the coup d'état, from 1936–1939, Madrid remained under the control of forces loyal to the Republic. Following the seemingly unstoppable advance towards Madrid of rebel land troops, the first air bombings on Madrid also started. Immediately after the bombing of the nearing airports of Getafe

Getafe () is a municipality and a city in Spain belonging to the Community of Madrid. , it has a population of 180,747, the region's sixth most populated municipality.

Getafe is located 13 km south of Madrid's city centre, within a flat ar ...

and Cuatro Vientos, Madrid proper was bombed for the first time in the night of the 27–28 August 1936 by a Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegera ...

's Junkers Ju 52

The Junkers Ju 52/3m (nicknamed ''Tante Ju'' ("Aunt Ju") and ''Iron Annie'') is a transport aircraft that was designed and manufactured by German aviation company Junkers.

Development of the Ju 52 commenced during 1930, headed by German aeron ...

that threw several bombs on the Ministry of War and the Station of the North. Madrid "was to become the first big European city to be bombed by aviation".

Rebel General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

, recently given the supreme military command over his faction, took a detour in late September to "liberate" the besieged Alcázar de Toledo

An alcázar, from Arabic ''al-Qasr'', is a type of Islamic castle or palace in the Iberian Peninsula (also known as al-Andalus) built during Muslim rule between the 8th and 15th centuries. They functioned as homes and regional capitals for gover ...

. Meanwhile, this operation gave time to the republicans in Madrid to build defenses and start receiving some foreign support.

The summer and autumn of 1936 saw the Republican Madrid witness of heavy-handed repression by communist and socialist groups, symbolised by the murder of prisoners in ''checas'' and ''sacas'' directed mostly against military personnel and leading politicians linked to the rebels, which, culminated by the horrific Paracuellos massacres in the context of a simultaneous major rebel offensive against the city, were halted by early December.

Madrid, besieged from October 1936, saw a major offensive in its western suburbs in November of that year.

;Collapse

In the last weeks of the war, the collapse of the republic was speeded by Colonel

The summer and autumn of 1936 saw the Republican Madrid witness of heavy-handed repression by communist and socialist groups, symbolised by the murder of prisoners in ''checas'' and ''sacas'' directed mostly against military personnel and leading politicians linked to the rebels, which, culminated by the horrific Paracuellos massacres in the context of a simultaneous major rebel offensive against the city, were halted by early December.

Madrid, besieged from October 1936, saw a major offensive in its western suburbs in November of that year.

;Collapse

In the last weeks of the war, the collapse of the republic was speeded by Colonel Segismundo Casado

Segismundo Casado López (10 October 1893 – 18 December 1968) was a Spanish Army officer; he served during the late Restoration, the Primo de Rivera dictatorship and the Second Spanish Republic. Following outbreak of the Spanish Civil W ...

, who, endorsed by some political figures such as Anarchist Cipriano Mera and Julián Besteiro

Julián Besteiro Fernández (21 September 1870 – 27 September 1940) was a Spanish socialist politician, elected to the Cortes Generales and in 1931 as Speaker of the Constituent Cortes of the Spanish Republic. He also was elected several times ...

, a PSOE leader who had held talks with the Falangist fifth column

A fifth column is any group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. According to Harris Mylonas and Scott Radnitz, "fifth columns" are “domestic actors who work to u ...

in the city, threw a military coup against the legitimate government under the pretext of excessive communist preponderance, propelling a mini-civil war in Madrid that, won by the ''casadistas'', left roughly 2,000 casualties between 5–10 March 1939.

The city fell to the nationalists on 28 March 1939.

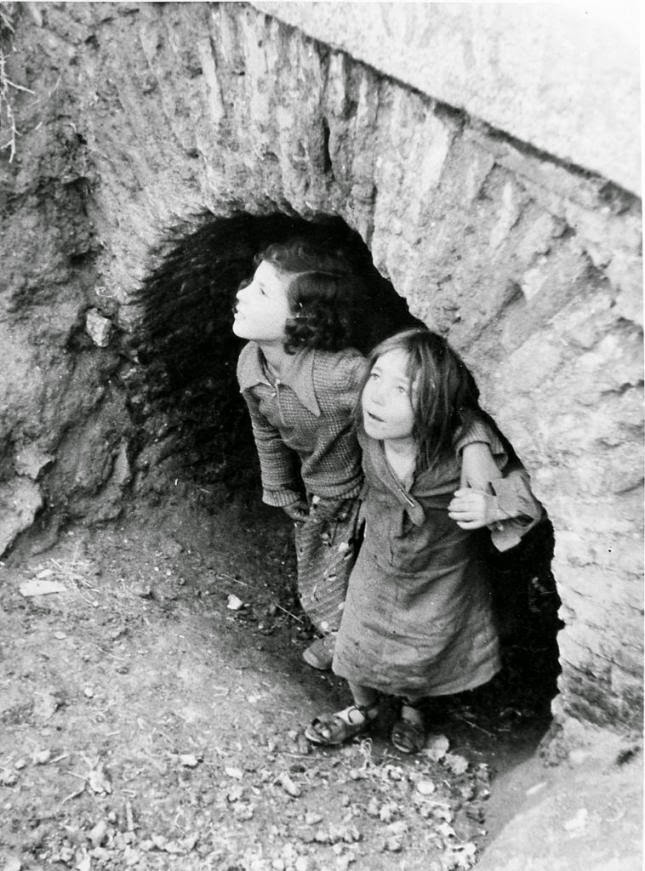

Following the onset of the Francoist dictatorship

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spa ...

in the city, the absence of personal and associative freedoms and the heavy-hand repression of people linked to a republican past greatly deprived the city from social mobilization, trade unionism and intellectual life. This added to a climate of general shortage, with ration coupons rampant and a lingering autarchic economy lasting until the mid 1950s. Meat and fish consumption was scarce in Post-War Madrid, and starvation and lack of proteins were a cause of high mortality.

With the country ruined after the war, the

With the country ruined after the war, the Falange

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS; ), frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco ...

command had nonetheless high plans for the city and professionals sympathetic to the regime dreamed (based on an organicist conception) about the notion of building a body for the "Spanish ggreatness" placing a great emphasis in Madrid, what they thought to be the imperial capital of the ''New State''. In this sense, urban planners sought to highlight and symbolically put in value the façade the city offered to the Manzanares River

The Manzanares () is a river in the centre of the Iberian Peninsula, which flows from the Sierra de Guadarrama, passes through Madrid, and eventually empties into the Jarama river, which in turn is a right-bank tributary to the Tagus.

In its ...

, the "Imperial Cornice", bringing projects to accompany the Royal Palace

This is a list of royal palaces, sorted by continent.

Africa

* Abdin Palace, Cairo

* Al-Gawhara Palace, Cairo

* Koubbeh Palace, Cairo

* Tahra Palace, Cairo

* Menelik Palace

* Jubilee Palace

* Guenete Leul Palace

* Imperial Palace- Mas ...

such as the finishing of the unfinished cathedral (with the start of works postponed to 1950 and ultimately finished in the late 20th century), a never-built "house of the Party" and many others. Nonetheless these delusions of grandeur caught up with reality and the scarcity during the Post-War and most of the projects ended up either filed, unfinished or mutilated, with the single clear success being the Gutiérrez Soto's Cuartel del Ejército del Aire.

The intense demographic growth experienced by the city via mass immigration from the rural areas of the country led to the construction of plenty of housing in the peripheral areas of the city to absorb the new population (reinforcing the processes of social polarization of the city), initially comprising substandard housing (with as many as 50,000 shack

A shack (or, in some areas, shanty) is a type of small shelter or dwelling, often primitive or rudimentary in design and construction.

Unlike huts, shacks are constructed by hand using available materials; however, whereas huts are usually r ...

s scattered around the city by 1956). A transitional planning intended to temporarily replace the shanty towns were the ''poblados de absorción'', introduced since the mid-1950s in locations such as Canillas, San Fermín, Caño Roto, Villaverde, , Zofío and Fuencarral Fuencarral is a neighborhood located in the northern part of Madrid, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: ...

, aiming to work as a sort of "high-end" shacks (with the destinataries participating in the construction of their own housing) but under the aegis of a wider coordinated urban planning.

Together with the likes of

Together with the likes of Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

, Santiago de Chile

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, wh ...

, Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (Romulus and Remus, legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

...

, Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South Am ...

or Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administrative limits w ...

, Francoist Madrid became an important transnational hub of the global Neofascist

Neo-fascism is a post-World War II far-right ideology that includes significant elements of fascism. Neo-fascism usually includes ultranationalism, racial supremacy, populism, authoritarianism, nativism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration sent ...

network that facilitated the survival and resumption of (neo)fascist activities after 1945.

In the 1948–1954 period the municipality greatly increased in size through the annexation of 13 surrounding municipalities, as its total area went up from 68,42 km2 to 607,09 km2. The annexed municipalities were Chamartín de la Rosa (5 June 1948), Carabanchel Alto (29 April 1948), Carabanchel Bajo (29 April 1948), Canillas (30 March 1950), Canillejas (30 March 1950), Hortaleza

Hortaleza is one of the 21 districts of the city of Madrid, Spain.

History

Origin

The first recorded human activity in the area of Hortaleza was the existence of a nomadic or semi-nomadic population in the Paleolithic and Neolithic eras, a ...

(31 March 1950), Barajas (31 March 1950), Vallecas

Vallecas was a municipality of Spain that disappeared as such in 1950, when its annexation to the Municipality of Madrid was effectuated. Nowadays it is a large neighborhood of Madrid composed of two districts: Puente de Vallecas (population ...

(22 December 1950), El Pardo

El Pardo is a ward ('' barrio'') of Madrid belonging to the district of Fuencarral-El Pardo. As of 2008 its population was of 3,656.

History

The ward was first mentioned in 1405 and in 1950 was an autonomous municipality of the Community of Mad ...

(27 March 1951), Vicálvaro

Vicálvaro is a district in the southeast of Madrid, Spain. It is named after the former municipality absorbed into the municipality of Madrid in 1951.

History

When Spain's Civil Guard ( es, Guardia Civil) was established in 1844, the first head ...

(20 October 1951), Fuencarral Fuencarral is a neighborhood located in the northern part of Madrid, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: ...

(20 October 1951) Aravaca

Aravaca is a ward (''Barrio'') of the city of Madrid, in Moncloa-Aravaca district. It is from the city centre, on the other side of Casa de Campo park. The population of the barrio is 29,547 (January 2006), divided into three areas: Aravaca ( ...

(20 October 1951) and Villaverde (31 July 1954).

The population of the city peaked in 1975 at inhabitants.

Recent developments

Benefiting from prosperity in the 1980s, Spain's capital city has consolidated its position as the leading economic, cultural, industrial, educational and technological center of the Iberian peninsula. The relative decline in population since 1975 reverted in the 1990s, with the city recovering a population of roughly 3 million inhabitants by the end of the 20th century.

Since the late 1970s and through the 1980s Madrid became the center of the cultural movement known as '' la Movida''. Conversely, just like in the rest of the country, a heroin crisis took a toll in the poor neighborhoods of Madrid in the 1980s.

During the mandate as mayor of

Benefiting from prosperity in the 1980s, Spain's capital city has consolidated its position as the leading economic, cultural, industrial, educational and technological center of the Iberian peninsula. The relative decline in population since 1975 reverted in the 1990s, with the city recovering a population of roughly 3 million inhabitants by the end of the 20th century.

Since the late 1970s and through the 1980s Madrid became the center of the cultural movement known as '' la Movida''. Conversely, just like in the rest of the country, a heroin crisis took a toll in the poor neighborhoods of Madrid in the 1980s.

During the mandate as mayor of José María Álvarez del Manzano

José María Álvarez del Manzano y López del Hierro (born 17 October 1937) is a Spanish politician for the People's Party. Although born in Seville he has lived in Madrid since he was 3 years old. He studied at the Colegio Nuestra Señora de ...

, construction of traffic tunnels below the city proliferated.

On 11 March 2004, three days before Spain's general elections and exactly 2 years and 6 months after the September 11 attacks in the US, Madrid was hit by a terrorist attack

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

when Islamic terrorists belonging to an al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

-inspired terrorist cell placed a series of bombs on several trains during the morning rush hour, killing 191 people and injuring 1,800.

The administrations that followed Álvarez del Manzano's, also conservative, led by

The administrations that followed Álvarez del Manzano's, also conservative, led by Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón

Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón Jiménez (born 11 December 1958) is a Spanish politician and former Minister of Justice. He was mayor of Madrid

The Mayor of Madrid presides over the Madrid City Council, the government body of the capital city of Spai ...

and Ana Botella, launched three unsuccessful bids for the 2012, 2016 and 2020 Summer Olympics. Madrid was a centre of the anti-austerity protests that erupted in Spain in 2011. As consequence of the spillover of the 2008 financial and mortgage crisis, Madrid has been affected by the increasing number of second-hand homes held by banks and house eviction

Eviction is the removal of a tenant from rental property by the landlord. In some jurisdictions it may also involve the removal of persons from premises that were foreclosed by a mortgagee (often, the prior owners who defaulted on a mort ...

s. The mandate of left-wing Mayor Manuela Carmena

Manuela Carmena Castrillo (; born in 1944) is a retired Spanish lawyer and judge who served as Mayor of Madrid from June 2015 to June 2019. She was a member of the General Council of the Judiciary.

Biography Early life

She was born on 9 Febru ...

(2015–2019) delivered the renaturalization of the course of the Manzanares across the city.

Since the late 2010s, the challenges the city faces include the increasingly unaffordable rental prices (often in parallel with the gentrification

Gentrification is the process of changing the character of a neighborhood through the influx of more affluent residents and businesses. It is a common and controversial topic in urban politics and planning. Gentrification often increases the ec ...

and the spike of tourist apartments in the city centre) and the profusion of betting shop

In the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand, a betting shop is a shop away from a racecourse ("off-course") where one can legally place bets in person with a licensed bookmaker. Most shops are part of chains including William Hill, ...

s in working-class areas, equalled to an "epidemics" among the young people.

Population

See also

* Timeline of MadridReferences

;Informational notes ;Citations ;Bibliography * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of MadridMadrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...